With the demonstration that two inactive lutropin receptor mutants can complement each other functionally, in vivo, the study by I. Huhtaniemi’s group in this issue of PNAS (1) constitutes a landmark in the long-lasting saga about di/oligomerization of rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptors (class A GPCRs).

In an early “dimer period,” arguments for dimerization were found in the negative cooperativity displayed by some GPCRs (2) and in the disproportionately large molecular radius of some of them, as obtained by radiation inactivation (3). Thereafter, a “monomer period” ensued, when cloning of hundreds of molecules displaying a stereotypical serpentine domain with seven transmembrane segments made it reasonable to consider monomolecular GPCRs as being already “polymers”… of their transmembrane helices. Over the past 15 years, arguments favoring the existence of di/oligomers of rhodopsin-like GPCRs accumulated from a wide variety of experimental approaches. These include plain Western blotting, coimmunoprecipitation, functional complementation of mutants in transfected cells, FRET and BRET experiments, and atomic force microscopy (4, 5). By analogy, the functional or structural demonstrations that class C GPCRs (GABAB receptor, metabotropic glutamate receptors, and sweet-umami receptors) function as exclusive homo- or heterodimers (6), added arguments to the di/oligomeric nature of class A GPCRs. In a revival of the early “cooperativity period,” a number of studies endowing putative hetero-di/oligomers with properties different from those of putative homo-di/oligomers (7), presented interaction between protomers as the basis of the apparent allosteric behavior of GPCRs (8).

The case for di/oligomerization of rhodopsin-like GPCRs is not definitively set, however. Convincing studies have demonstrated that rhodopsin or the beta2 adrenergic receptor can signal to their respective G protein as monomeric units (9, 10). Also, the cooperative behavior displayed by some GPCRs in native or transfected cells has been proposed to reflect postreceptor regulatory effects rather that di/oligomerization (11). With the exception of the very peculiar case of rhodopsin in the retina (5), all experiments demonstrating a physical interaction between class A GPCRs have up to now been performed ex vivo, in transfected cells, which implies nonphysiological cellular environments and, in most cases, unrealistic concentrations of receptors in the membranes.

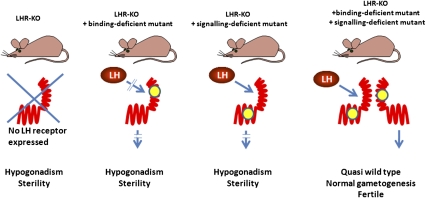

In this context the in vivo study by Rivero-Müller et al. (1) constitutes a major contribution to the field. The luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR), together with the follitropin and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors, belongs to the glycoprotein hormone receptors, a subfamily of rhodopsin-like GPCRs characterized by a large ectodomain responsible for hormone binding (12). Huhtaniemi’s group built on the observation that some loss-of-function mutants of the LHR displayed functional complementation when transfected in vitro (13). The first mutant they chose is deficient for hormone binding as it bears an amino acid substitution in the ectodomain. The second mutant harbors a deletion of transmembrane helices VI and VII. Although it is competent for hormone binding, it is completely deficient for signal transduction. Following careful characterization of the phenotype of each mutant in transfected HEK293 cells, and after demonstration by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting that tagged mutants were capable of specific interaction in transiently transfected cells, Rivero-Müller et al. shifted from the culture dish to the living transgenic animal (for an illustration of the strategy, see Fig. 1). They used as recipient animals a mouse line generated previously by homologous recombination, which is totally deficient for the LHR and, as a consequence, displays profound hypogonadism and complete infertility (14). Two transgenic lines were established by microinjection in fertilized oocytes of bacterial artificial chromosomes bearing the individual loss-of-function LHR mutants in the genomic environment of the normal LHR gene. This ensures (and it was verified by the authors) that, in the two mouse lines, the mutant LHR genes are expressed qualitatively (i.e., in the normal cell types) and quantitatively normally. As expected, when expressed on the LHR knockout background by an adequate breeding strategy, both mutants were well expressed in the testes, but only homogenates of the signaling-deficient mutant displayed efficient binding of 125I-hCG. As also expected, the hypogonadism phenotype of the LHR knockout animals was not modified by addition of either the binding-deficient or the signaling-deficient transgene alone (Fig. 1). The key experiment, generation of mice coexpressing the two mutants on a LHR knockout background, demonstrated that close to full functional complementation had taken place. The male mice displayed normal sexual development, normal gametogenesis, and normal reproductive behavior, with a fertility matching that of wild-type animals. Their testosterone levels were in the normal range. A slight increase of circulating luteinizing hormone (LH) was the only index that complementation between the two disabled receptors may not be 100% complete.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the strategy followed by Rivero-Müller et al. to demonstrate in vivo dimerization of the lutropin receptor. (Upper) The various genotypes are represented. (Lower) Corresponding phenotypes. The binding-deficient or signaling-deficient receptors are schematized with mutations (yellow dot) affecting the ectodomain or the serpentine domain, respectively.

The study by Rivero-Müller et al. establishes beyond reasonable doubt that at least glycoprotein hormone receptors are able to di/oligomerize in vivo, when expressed at their normal physiological concentrations. Indeed, the very nature of the mutants implies that physical interaction must occur to achieve functional complementation. The study, however, leaves open a series of important questions. How does complementation between the mutants take place? What are the structures involved? How do di/oligomeric receptors function normally in vivo? Can the studies with glycoprotein hormone receptors be extrapolated to the whole rhodopsin-like GPCR family? Studies with dopamine receptors suggest that the interface of dimers involves transmembrane helix IV (15). Refinement of these studies proposed that helices I and IV were implicated in the generation of higher order oligomers (16). Although not impossible, these data are not easily reconciled with the complementation phenomenon observed here, in which one of the partners has two of its transmembranes helices (VI and VII) deleted. From the crystallographic structure of the complex between follicle stimulation hormone (FSH) and the ectodomain of the FSH receptor, it has been suggested that dimerization of the glycoprotein hormone receptors might involve interaction of specific tyrosine residues (Y 110) in the ectodomain (17), which would fit with the results of Rivero-Müller et al.

Asymmetry is becoming a central notion in the functioning of GPCRs di/oligomers.

Whatever the structures involved, the complementation phenomenon implies that binding of the hormone to the signaling-deficient partner results in a productive conformational change in the binding-deficient partner. In their cartoon (figure 1 in ref. 1) Rivero-Müller et al. suggest that the intact ectodomain of the signaling-deficient mutant positions the hormone so that it interacts productively with the serpentine domain of the binding-deficient partner. Although a possibility, the current model for activation of glycoprotein hormone receptors suggests that activation of the serpentine portion would be achieved by an “activated conformation” of the ectodomain, rather than by the hormone itself (18). The “hinge” region, between the hormone binding segment and the serpentine domain, is believed to play a key role in transducing the activation signal to the serpentine domain. This suggests the alternative possibility that it would be the “activated hinge” region of the signaling-deficient mutant that would interact with the binding-deficient partner and activate it.

The current study implies that activation of a single protomer of a di/oligomer is enough to achieve signal transduction. This is reminiscent of conclusions drawn from experiments demonstrating strong negative binding cooperativity in the TSH-TSH receptor couple, which suggested that under normal physiological conditions binding of TSH would occur on a single protomer (8). Also, it agrees with results showing that activation of the leukotriene B4 receptor induces asymmetry in a dimer, with a single protomer achieving an activated state (19). Finally, recent results with dopamine receptors demonstrate that “the minimal signaling unit, i.e. two receptors and a single G protein, is maximally activated by agonist binding to a single protomer” (20). This study suggests a mechanism in which two GPCRs activate a single G protein through interactions that involve intracellular loop 2 (IL2) from both protomers, whereas IL3 from only one protomer is essential for signaling. This would be fully compatible with the data of Rivero-Müller et al., in which IL2 is expected to be intact in both loss-of-function mutants, whereas IL3 would be altered/absent in the signaling-deficient mutant.

Asymmetry is becoming a central notion in the functioning of GPCRs di/oligomers. Although these concepts originated essentially from in vitro experiments, the study of Rivero-Müller et al. demonstrate neatly that they apply to real life.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 2319.

References

- 1.Rivero-Müller A, et al. Rescue of defective G-protein-coupled receptor function in vivo by intermolecular cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;107:2319–2324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906695106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell-Jones CH, Thomas CGJ, Jr, Nayfeh SN. Contribution of negative cooperativity to the thyrotropin-receptor interaction in normal human thyroid: Kinetic evaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:705–709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frame LT, Yeung SM, Venter JC, Cooper DM. Target size of the adenosine Ri receptor. Biochem J. 1986;235:621–624. doi: 10.1042/bj2350621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier M. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled transmitter receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fotiadis D, et al. Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421:127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prinster SC, Hague C, Hall RA. Heterodimerization of G protein-coupled receptors: Specificity and functional significance. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:289–298. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldhoer M, et al. A heterodimer-selective agonist shows in vivo relevance of G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9050–9055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501112102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springael JY, Urizar E, Costagliola S, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Allosteric properties of G protein-coupled receptor oligomers. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst OP, Gramse V, Kolbe M, Hofmann KP, Heck M. Monomeric G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in solution activates its G protein transducin at the diffusion limit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10859–10864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701967104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whorton MR, et al. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabre M, Deterre P, Antonny B. The apparent cooperativity of some GPCRs does not necessarily imply dimerization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S. A molecular dissection of the glycoprotein hormone receptors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C, et al. Two defective heterozygous luteinizing hormone receptors can rescue hormone action. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15795–15800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang FP, Pakarainen T, Zhu F, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I. Molecular characterization of postnatal development of testicular steroidogenesis in luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1453–1463. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Shi L, Javitch JA. The fourth transmembrane segment forms the interface of the dopamine D2 receptor homodimer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4385–4388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo W, et al. Dopamine D2 receptors form higher order oligomers at physiological expression levels. EMBO J. 2008;27:2293–2304. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nature03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlaeminck-Guillem V, Ho SC, Rodien P, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Activation of the cAMP pathway by the TSH receptor involves switching of the ectodomain from a tethered inverse agonist to an agonist. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:736–746. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damian M, Martin A, Mesnier D, Pin JP, Banères JL. Asymmetric conformational changes in a GPCR dimer controlled by G-proteins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5693–5702. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han Y, Moreira IS, Urizar E, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]