Abstract

Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is a rare condition. We present a case of idiopathic gingival fibromatosis with its multidisciplinary approach of management. The clinical, radiographic, and histopathological features have been described in detail.

1. Introduction

Gingival hyperplasia is a bizarre condition causing esthetic, functional, psychological, and masticatory disturbance of the oral cavity. Causes of gingival enlargement can be due to plaque accumulation, due to poor oral hygiene, inadequate nutrition, or systemic hormonal stimulation [1]. Gingival enlargements are also pragmatic in several blood dyscrasias such as leukaemia, thrombocytopenia, or thrombocytopathy. A progressive fibrous enlargement of the gingiva is a facet of idiopathic fibrous hyperplasia of the gingival [2]. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is a rare hereditary condition that has no definite cause [3]. Investigations are in evolution to establish the genetic linkage and heterogeneity associated with it [4, 5]. This condition may manifest as an autosomal dominant or, less commonly, an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, either as an isolated disorder or as part of a syndrome [6–9]. Autosomal-dominant forms of gingival fibromatosis, which are usually nonsyndromic, have been genetically linked to the chromosome 2p21-p222 and 5q13-q22.

In modern times, a mutation in the son of sevenless-1 (SOS-1) gene has been suggested as a possible cause of isolated (nonsyndromic) gingival fibromatosis, but no definite linkage has been established [10]. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is a gradually progressive benign enlargement that affects the marginal gingiva, attached gingival, and interdental papilla. The fibromatosis may potentially cover the exposed tooth surfaces, thereby hampering the functioning of the stomatognathic system. The gingival tissues are usually pink and nonhemorrhagic and have a firm, fibrotic consistency. Histopathologically, the bulbous increased connective tissue is relatively avascular, and has densely arranged collagen-fibre bundles, numerous fibroblasts, and mild chronic inflammatory cells. The overlying epithelium is thickened and acanthotic, and has elongated rete ridges [11–15]. The autosomal dominant form is often associated with hypertrichosis, corneal dystrophy, nail defects, deafness, and craniofacial deformities. In children suffering from autosomal dominant form, they may suffer from mental retardation and epilepsy. Autosomal recessive form facial anomalies with hypertelorism, have been observed but most forms are without defects, other than gingival enlargement. Consanguinity has been observed in recessive form. We report a case of nonsyndromic case of idiopathic gingival fibromatosis along with its management.

2. Case Report

A-18-year-old unmarried poor Muslim girl reported to the outpatient department of Dr. DY Patil Dental College and Hospital, Pune, India with a chief complaint of swollen gums since she was 6 years old. (Figure 1) According to patient, swelling appeared at the time of eruption of permanent teeth. Swelling was not associated with pain. She reported to the department as she was having functional and masticatory difficulty. Patient's medical, dental, personal, and family histories were noncontributory. There was no history of consanguious marriage. Extraneoral examination showed facial disfigurement with protruding lips.

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph with fullness of face.

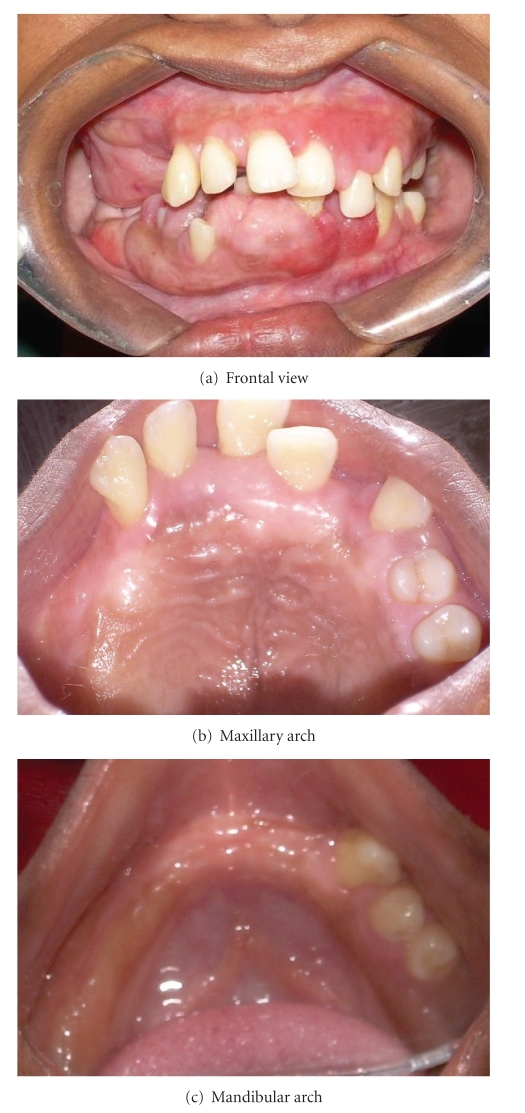

Intraoral examination revealed enlargement of gingiva on both buccal and lingual/palatal sides with pinkish red in color, fibrous in consistency with absence of stippling. (Figure 2) Bleeding on probing was absent. Gingival enlargement enclosed the major surface of the teeth present except the incisal/occlusal surfaces. Clinical examination revealed upper right second molar, upper and lower left first and second molars, and lower right second premolar; first and second molars were absent. Mobility was seen in all the teeth present. There was increase in intermaxillary rest position. Based on the above findings, a provisional diagnosis of idiopathic generalized gingival fibromatosis was made. Intraoral periapical radiographs, panoramic radiograph, and lateral cephalogram radiograph were advised. Also a whole body general body examination and blood investigations were advised to eliminate any medical abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Pre-perative intraoral picture of generalized gingival fibromatosis.

Radiographic examination revealed generalised bone loss giving floating teeth appearance in the region of all posterior teeth. There was displacement of upper second and third molars tooth bud in the tuberosity region. Also lower left second molar tooth bud was displaced in midramus region. Horizontally impacted lower right second premolar was seen. (Figures 3 and 4) Multidisciplinary approach for treatment was considered. Patient was referred to the periodontics department for further treatment. Treatment decided was full-mouth gingivectomy, extraction of mobile teeth, and prosthetic rehabilitation with upper and lower partial denture. Patient was educated about the impacted tooth which was planned to be extracted on being symptomatic.

Figure 3.

Panoramic radiograph showing generalized bone loss with floating teeth appearance.

Figure 4.

Lateral cephalogram showing the soft-tissue profile.

2.1. Surgery

Considering the size and extent of gingival enlargement, a quadrant-wise gingivectomy was performed under local anaesthesia. An external bevel gingivectomy was done in all four quadrants. Mobile teeth were extracted at the time of surgery. Healing was uneventful. The total masses of excised gingival tissue were sent for histopathological examination (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Postoperative intraoral view following gingivectomy.

Figure 6.

Excised tissue mass.

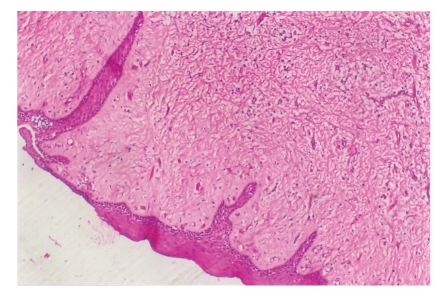

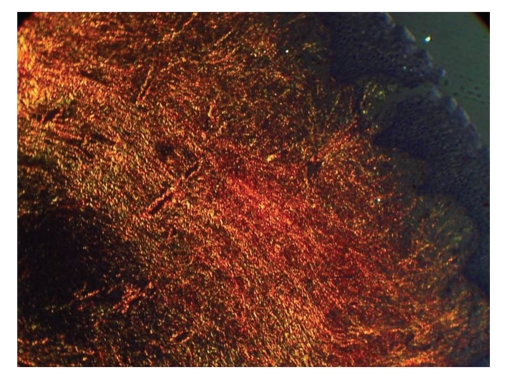

2.2. Histopathological Report

Histopathological examination revealed abundance of collagen. Fibroblasts were increased in number, and various degrees of chronic inflammation were seen. The overlying epithelium exhibited some hyperplasia. Polarized microscope with picro sirus stain revealed more of mature collagen which stained red, while there was presence of immature collagen as well which stained green (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

Histopathological picture.

Figure 8.

Picrosirus stain.

2.3. Prosthetic Stage

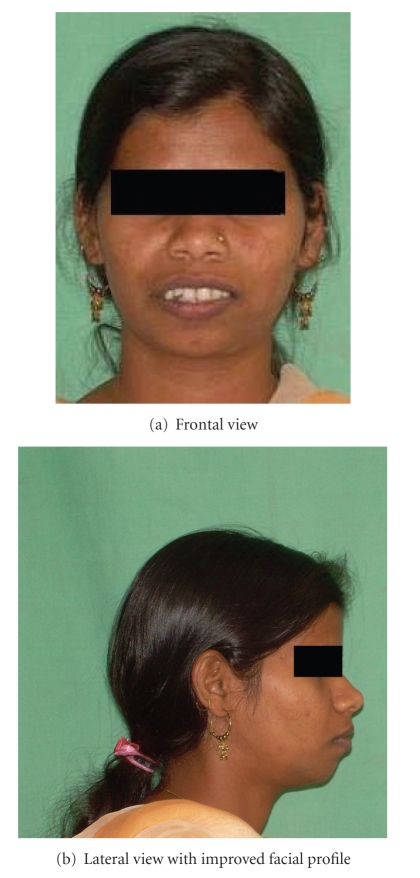

Following complete healing, a temporary partial denture was made. On completion of proposed treatment plan, patient's functional and aesthetic requirement improved significantly (Figures 9 and 10). Patient was very happy with the partial denture and refused any further treatment.

Figure 9.

Partial denture constructed.

Figure 10.

Final postoperative view with denture.

3. Discussion

Gingival overgrowth varies from mild enlargement of an isolated interdental papillae to segmental or uniform and marked enlargement affecting one or both of the jaws [16]. Here we reported a case of nonsyndromic idiopathic generalized gingival fibromatosis with its prosthetic rehabilitation by multidisciplinary approach. As the family, medical, prenatal, drug histories were noncontributory, we gave a diagnosis of idiopathic gingival fibromatosis. There are multiple causes of generalized gingival fibromatosis. (Table 1) Diverse syndromes having varying mode of inheritance are reported of having generalized gingival fibromatosis. (Table 2) The precise mechanism of idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is unknown but it appears to confine to the fibroblasts which harbor in the gingivae. The hyperplastic response does not involve the periodontal ligament and occurs peripheral to the alveolar bone within attached gingival [17]. The growth is linked with eruption of teeth as seen in present case, and the presence of teeth may be necessary for the commencement of the process. Fibromatosis gingivae may hinder tooth eruption, mastication, and oral hygiene. In severe cases, noneruption of the primary or permanent teeth may be the chief complaint of the patient [18]. Our patient suffered from difficulty in mastication and swallowing due to gingival overgrowth which resulted in atypical swallowing pattern [19]. Also due to the facial disfigurement, the family were worried about marriage prospect of the patient. The finest and suggested treatment modality for idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is gingivectomy [20]. Literature reports high recurrence rate after surgery, and needs a close follow up. Present case has been followed for 2 years with no recurrence. There is debate regarding the time of surgery. Eruption of complete set of permanent teeth is the recommended time for surgery [21]. Our patient had eruption of permanent teeth, and hence surgery was considered as the best approach. Histopathologically, fibromatosis shows a bulbous increase in the connective tissue which is relatively avascular and has densely arranged collagen-fibre bundles, numerous fibroblasts, and mild chronic inflammatory cells. The overlying epithelium is thickened and acanthotic and has elongated rete ridges. Our case report showed similar histological findings. Unusual findings include the presence of small calcified particles, amyloid deposits, islands of odontogenic epithelium, and osseous metaplasia in the connective tissue. Patient was advised to maintain good oral hygiene to minimize the effect of inflammation on fibroblasts.

Table 1.

Causes of generalised gingival fibromatosis.

| Hyperplastic gingivitis |

|---|

| Mouth-breathing gingivitis |

| Drug-induced gingival overgrowth |

| Scurvy |

| Gingival overgrowth in pregnancy |

| Gingival overgrowth due to leukemia |

| Hereditary gingival fibromatosis |

| Wegener granulomatosis |

| Acanthosis nigricans |

| Idiopathic variety |

Table 2.

Syndromes associated with gingival fibromatosis.

| Syndrome | Clinical features | Mode of inheritance |

|---|---|---|

| Laband syndrome | Syndactily, nose and ear abnormalities, hyperplasia of the nails, and terminal phalanges | Dominant |

| Rutherfurd syndrome | Corneal dystrophy | Dominant |

| Cross syndrome | Microphthalmia, mental retardation, and pigmentary defects | Recessive |

| Ramon syndrome | Hypertrichosis, mental retardation, delayed development epilepsy, and cherubism | Recessive |

4. Conclusion

Present case was of nonsyndromic idiopathic gingival enlargement, with its multidisciplinary management. Treatment was complete excision and prosthetic rehabilitation which appreciably improved the aesthetic and masticatory competence.

Acknowledgment

The study was self-funded by the authors and their institution. No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Regezi JA, Sciuba JJ. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: W.B. Saunders; 1999. Connective tissue lesions; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cekmez F, Pirgon O, Tanju IA. Idiopathic gingival hyperplasia. International Journal of Biomedical Science. 2009;5(2):198–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carranza FA, Hogan EL. Gingival enlargement. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 9th edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Saunders; 2002. pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart TC, Pallos D, Bowden DW, Bolyard J, Pettenati MJ, Cortelli JR. Genetic linkage of hereditary gingival fibromatosis to chromosome 2p21. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62(4):876–883. doi: 10.1086/301797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart TC, Pallos D, Bozzo L, et al. Evidence of genetic heterogeneity for hereditary gingival fibromatosis. Journal of Dental Research. 2000;79(10):1758–1764. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozzo L, de Almeida O, Scully C, Aldred MJ. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis. Report of an extensive four-generation pedigree. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1994;78(4):452–454. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozzo L, Machado MA, de Almeida OP, Lopes MA, Coletta RD. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: report of three cases. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2000;25(1):41–46. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.25.1.e254616x22403280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martelli H, Jr., Lemos DP, Silva CO, Graner E, Coletta RD. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: report of a five-generation family using cellular proliferation analysis. Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76(12):2299–2305. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.12.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer SL, Goldblatt J, Hallam LA, Winters JC. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis with a recessive mode of inheritance. Case reports. Australian Dental Journal. 1993;38(6):427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1993.tb04755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaturvedi R. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis: a case report. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2009;75(4):291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coletta RD, Graner E. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: a systematic review. Journal of Periodontology. 2006;77(5):753–764. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeAngelo S, Murphy J, Claman L, Kalmar J, Leblebicioglu B. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis—a review. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 2007;28(3):138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelekis-Cholakis A, Wiltshire WA, Birek C. Treatment and long-term follow-up of a patient with hereditary gingival fibromatosis: a case report. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2002;68(5):290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramer M, Marrone J, Stahl B, Burakoff R. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: identification, treatment, control. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1996;127(4):493–495. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baptista IP. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: a case report. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2002;29(9):871–874. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwana PS, De Kok IJ, Stoker DS, Cooper LF. Facial distortion secondary to idiopathic gingival hyperplasia: surgical management and oral reconstruction with endosseous implants. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2005;100(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd edition. London, UK: Mosby; 2004. Connective tissue lesions; pp. 294–297. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neville BW, Damm DD, White DH. Colour Atlas of Clinical Pathology. 2nd edition. Hamilton, Canada: Decker; 2003. Soft tissue tumours; pp. 276–312. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Indushekar KR. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis. Case report. Saudi Dental Journal. 2003;14:143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tavageri AK, Kulkarni SS, Basavprabhu SP. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis—a case report. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2004;22(4):180–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emerson TG. Hereditary gingival hyperplasia. A family pedigree of four generations. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1965;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]