Abstract

It is postulated that basic residues within the inhibitory region of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) bind acidic residues within the catalytic core to maintain the kinase in an inactive form. In this study, we identified residues within the catalytic cores of the skeletal and smooth muscle MLCKs that may bind basic residues in inhibitory region. Acidic residues within the catalytic core of the rabbit skeletal and smooth muscle MLCKs were mutated and the kinetic properties of the mutant kinetics determined. Mutation of 6 and 8 acidic residues in the skeletal and smooth muscle MLCKs, respectively, result in mutant MLCKs with decreases in KCaM, (the concentration of calmodulin required for half-maximal activation of myosin light chain kinase) value ranging from 2- to 100-fold. Two inhibitory domain binding residues identified in each kinase also bind a basic residue in light chain substrate. The remaining mutants all have wild-type Km values for light chain. The predicted inhibitory domain binding residues are distributed in a linear fashion across the surface of the lower lobe of the proposed molecular model of the smooth muscle MLCK catalytic core. As 6 of the inhibitory domain binding residues in the smooth muscle MLCK are conserved in other Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases, the structural basis for autoinhibition and activation may be similar.

Activation of protein kinases can occur by a variety of distinct mechanisms involving association of an allosteric regulator, dissociation of a regulatory subunit, or covalent modification of the enzyme. In many cases activation results from removal of an inhibitory region from the active site of the kinase. The inhibitory region of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)1 is part of the primary structure of the enzyme and is referred to as an autoinhibitory domain. As the primary sequences of autoinhibitory domains appear to be structurally similar to the specific substrate for the kinase, these regions are described as pseudosubstrate inhibitory regions (Kemp and Pearson, 1991). It has been proposed that the pseudosub strate sequence mimics the substrate and folds into the active site of the enzyme. Binding of the inhibitory region thus creates a stearic block that prevents access of the substrate. The binding of Ca2+/calmodulin, to a region near or overlapping the inhibitory domain of MLCK, is proposed to induce a conformational change which removes the pseudosubstrate from the active site thereby activating the enzyme (Kemp and Pearson, 1991).

Recent studies characterizing myosin light chain kinase mutants have suggested that this simple model is insufficient to describe the activation of this enzyme (Fitzsimons et al., 1992; Herring, 1991; Bagchi et al., 1992; Bagchi et. al., 1989; Shoemaker et al., 1990). For example, mutation of basic residues in the pseudosubstrate inhibitory domain that align with important basic residues in the light chain substrate do not lead to a constitutively active enzyme (Bagchi et al., 1992; Fitzsimons et al., 1992). In a molecular model describing the autoinhibition of MLCK (Knighton et al., 1992), a large number of possible electrostatic interactions between acidic residue, in the catalytic core and basic residues in the pseudosubstrate sequence of the chicken smooth muscle MLCK were postulated. This model (Knighton et al., 1992), together with studies using peptide inhibitors (Knighton et al., 1992; Foster et al., 1990) and mutagenesis studies (Fitzsimons et al., 1992) show that the length of the proposed inhibitory domain should be extended and suggest that this region can bind both residues that interact with substrate as well as residues which do not.

Two acidic amino acids have been identified within the catalytic core of both the smooth and skeletal muscle MLCKs which are proposed to bind to a basic residue at the p-3 position (three residues N-terminal of the phosphorylatable serine) in the smooth muscle light chain substrate (Herring et al., 1992). The autoinhibitory region of MLCK, like the light chain substrate, contains many basic residues which have been shown to be important for its inhibitory potency (Shoemaker et al., 1990; Kemp et al., 1987; Fitzsimons et al., 1992). When 4 basic residues in the autoinhibitory domain of smooth muscle MLCK were mutated to neutral or opposite charge residues, there was an increase in the sensitivity of the enzyme to activation by Ca2+/calmodulin (Fitzsimons et al., 1992). This effect was most likely due to a decrease in the potency of the autoinhibitory domain and an increase in the rate of isomerization of the kinase from the inactive to active form. We propose that if an acidic residue in the catalytic core bind, to a basic residue in the autoinhibitory domain, then mutation of one of these residues should weaken its electrostatic interaction with the other residue. This effect would be demonstrated by decrease in [Ca2+]0.5 (Ca2+ concentration required for half-maximal activation) and by a decrease in KCaM (concentration of Ca2+/calmodulin required for half-maximal activation).

The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases appear to be regulated via a similar autoinhibitory mechanism (Kemp and Stull, 1990), and it is likely that residues involved in binding the inhibitory domain are conserved among these enzymes. In fact, many charged residues residing within four subdomains (V. VI, X, XI) of the catalytic core have been found to be highly conserved among the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (Leachman et al., 1992).

In this investigation, we sought to extend previous studies by identifying acidic residues in the catalytic core of the rabbit smooth and skeletal muscle MLCKs that are involved in binding basic residues in the autoinhibitory region. We also determined the role of these acidic residues in binding the light chain substrate. Simple assumptions were used in this analysis; if an acidic residue was involved in binding to the inhibitory domain or substrate, its mutation, particularly to the opposite charge (charge reversal mutation), should weaken or disrupt the interaction. This effect would be manifested as a decrease in the potency of the inhibitory domain and/or an increase in the Km value for the light chain (Herring, 1991; Fitzsimons et al., 1992; Herring et al., 1992).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

COS Cell Expression and Oligonucleotide-directed Mutogenesis

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was performed by the method of Kunkel et al. (1987) using mutagenic oligonucleotides designed to produce desired amino acid substitutions. For each mutant cDNA the desired nucleotide substitutions were verified by DNA sequencing. Wild-type and mutant rabbit skeletal and smooth muscle myosin light chain kineses were expressed in COS cells as described previously (Herring et al., 1990; Gallagher et al., 1991). Myosin light chain kinase present in COS cell lysates were quantitated by immunoblotting using biotinylated calmodulin (Billingsley et al., 1985) in place of the primary antibody and using purified rabbit skeletal or bovine tracheal smooth muscle myosin light kineae as standards (Herring et al., 1992; Fitzsimons et al., 1992).

Protein Purification and Myosin Light Chain Kinase Assays

Rabbit skeletal muscle and bovine tracheal smooth muscle myosin light chain kineses were purified as described previously (Stull et al., 1990; Herring, 1991). Calmodulin was purified from bovine testis (Blumenthal and Stull, 1982). Rabbit skeletal muscle and chicken gizzard smooth muscle myosin light chains were purified according to Blumenthal and Stull (1980) and Hathaway and Haeberle (1983), respectively. Kinetic parameters for the expressed wild-type and mutant myosin light chain kineses were determined directly in COS cell lysates as described previously (Herring et al., 1990, 1992; Fitzsimons et al., 1992). COS cell lysates were diluted 50–500-fold into the reaction mixture. A 1:10 dilution of mock-transfect COS cells has no detectable myosin light chain kineae activity. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent activity of wild-type and mutant myosin light chain kinases was measured by 32P incorporation into light chain (Blumenthal and Stull, 1980). Maximal activity was determined in reaction mixtures having 50 mm MOPS, 10 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 µm calmodulin, 300 µm CaCl2, 1 mm[γ - 32P]ATP (200–300 cpm/pmol) and 20 µm light chain at 30°C. The Ca2+/calmodulin-independent activity of wild-type and mutant kineses was measured as radioactivity incorporated in the presence of 3 mm EGTA. When assayed at a 1:10 dilution, mock-transfected COS cell extracts exhibited <5% of the total kineae activity, with no detectable activity observed in the presence of 3 mm EGTA. Calmodulin activation properties of kinases were performed as described previously (Herring, 1991; Fitzsimons et al., 1992) in the following reaction mixture: 50 mm MOPS, 10 mm magnesium acetate, l mm dithiothreitol, 1 µm calmodulin, 1 mm [γ-32P]ATP (200–300 cpm/pmol), and 20 µm light chain at 30°C and various concentrations of free Ca2+ as determined by Ca2+/EGTA buffers. In this assay, the free Ca2+ concentration determines the concentration of Ca2+/calmodulin. Quantitative changes in the calmodulin activation properties (KCaM) of mutant myosin light chain kinases were assessed by determining the ratio of activities at Ca2+ concentrations that result in less than maximal activity to maximal activity measured at 10 µM Ca2+ (Miller et al., 1983; Stull et al., 1990). The ratio of activity at a specific Ca2+ concentration that is less than that required for maximal activity decreases quantitatively as the KCaM value for a mutant kinase increases relative to the wild-type enzyme. Likewise, if the ratio of activity increases, the KCaM value decreases. It is assumed that in this analysis that the Ca2+ binding properties of calmodulin are not changed end that the kinase is activated by a single Ca2+/calmodulin complex. Although the ratio of activities does not allow determination of the absolute value of KCaM, it may be used to calculate the -fold change in KCaM based upon the quantitative relationship described previously (Miller et al., 1983; Stull et al., 1990; Herring, 1990; Fitzsimons et al., 1992). Light chain Km determinations were made by varying the concentrations of skeletal or smooth muscle myosin light chain in kinase assays, and Km, and Vmax values were determined from Lineweaver-Burk plots.

RESULTS

Catalytic Core Mutants in Smooth and Skeletal Muscle Myosin Light Chain Kinases

We have noted previously that many acidic residues within subdomains V, VI, X, and XI of the catalytic cores of the Ca2+/calmodulin-regulated protein kinases are conserved (Leachman et al., 1992). To determine if conserved residues within these subdomains have a role in regulating enzyme activity, we mutated some of the acidic residues residing in these subdomains to basic residues and characterized the resulting mutant kinases with respect to light chain binding and their calcium activation properties. Mutations were made within the catalytic cores of both smooth and skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinases and the mutant enzymes were expressed in COS cells. The expressed proteins were analyzed by Western immunoblotting as described previously (Herring et al., 1990, 1992; Fitzsimons et al., 1992). All of the mutant proteins were visualized as single bands on blots and were stably expressed at high levels in COS cells (data not shown).

Kinetic Analyses of Catalytic Core Mutants

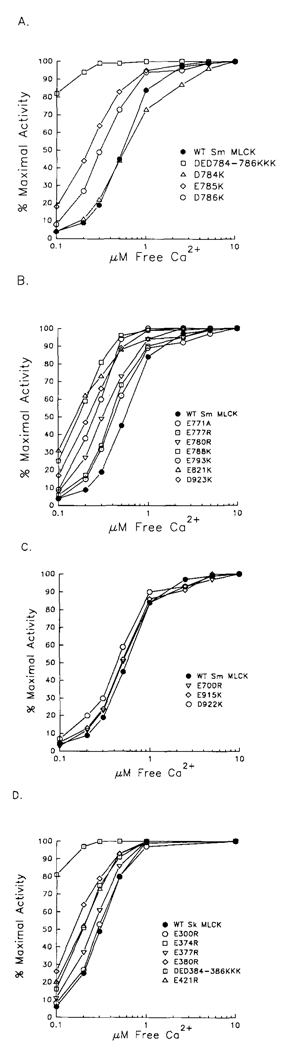

The activity of the catalytic core mutants was determined in kinase assays by measuring the rate of 32P incorporation into smooth or skeletal muscle myosin light chains. All of the active mutants were completely dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin for catalytic activity, with no significant Ca2+/calmodulin-independent activity (data not shown). A triple mutation in the rabbit smooth muscle (Sm) MLCK, SmDED784-786KKK, resulted in marked decreases in [Ca2+]0.5 and KCaM (Fig. 1A and Table 1). There were no other changes in catalytic properties, Individual mutations in SmE785 and SmD786, but not SmD784, showed a decrease in [Ca2+]0.5 and KCaM values. These results are consistent with the binding of these 2 acidic residues to the inhibitory domain but not to light chain. A triple mutant at a similar position in skeletal muscle (Sk) MLCK (Sk-DED384-386KKK) resulted in a similar decrease in KCaM with no significant changes in other catalytic properties (Fig. ID and Table II). Based upon the results obtained with smooth muscle MLCK, we predict residues SkE385 and SkD386 are involved in binding the inhibitory domain.

FIG. 1. Ca2+ activation of mutated myosin light chain kinases.

Rabbit smooth (A–C) and skeletal (D) muscle myosin light chain kineses were expressed in COS cells for measurement of kinase activities in cell lysates at 1 µm calmodulin as described previously. MLCK activity was measured at different free Cat2+ concentrations, and the data were normalized to the percent maximal activity. Symbols represent a mean value of at least three independent assays, each performed in duplicate. Data are presented without error bars for clarity; the S.E. values were within ± 2%.

TABLE I. Kinetic properties of mutated rabbit smooth muscle myosin light chain kinases.

Mutagenesis, expression in COS cells, quantitation of expressed kinase in COS cell extracts, and measurements of kinetic properties of rabbit smooth muscle MLCKs were performed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Values represent means ± S.E. for three to four experiments with lysates from transfections representing at least two independent mutants. [Ca2+]0.5 values represent the Ca2+ concentration (µm) required for half-maximal activation at 1 µm calmodulin. In these assays the free Ca2+ concentration was varied over a range of 100 nm to 10 µm with a Ca2+/EGTA buffer system. The relative KCaM values represent values determined from at least three Ca2+ concentrations. Vmax values were determined from double-reciprocal plots (Lineweaver-Burk) of data obtained from experiments with varying concentrations of either myosin light chain or [γ-32P]ATP. When Km values for light chain or ATP were not determined, Vmax is the rate value determined at 25 µm light chain, 1 mm [γ-32P]ATP, 1 µM calmodulin, and 0.3 mm Ca2+.

| SmMLCK | [Ca2+]0.5 | Relative KCaM | KmLC | Vmax | KmATP | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µm | nm | µm | µmol 32P/min/mg | µm | ||

| Wild-type | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 1.0 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 22 ± 1 | 71, 77 | WT |

| E700R | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 10, 12 | 25 ± 3 | 91, 109 | WT |

| E771A | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.00 | 6.1, 6.7 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 200, 166 | ATP (?) |

| E777K | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 1124 ± 248 | 29 ± 3 | 50, 54 | ID/LC |

| E780R | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 18.0 & 1.3 | 14 ± 0.5 | 76, 77 | ID/(LC?) |

| DED784-786KKK | <0.1 | 0.01. ± 0.00 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 20 ± 0.5 | 57, 40 | ID |

| D784K | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | ND | 24 ± 1 | ND | WT |

| E785K | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | ND | 25 ± 1 | ND | ID |

| D786K | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | ND | 20 ± 0.3 | ND | ID |

| E788K | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ±0.05 | 2.5, 2.5 | 20 ± 2 | 41,56 | ID |

| E793A | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 3.6, 5.0 | 22 ± 2 | ND | ID |

| E793K | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | ND | 14 ± 1 | ND | ID |

| E821K | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 611 ± 100 | 32 ± 7 | 48, 58 | ID/LC |

| E915K | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | ND | 22 ± 1 | ND | WT |

| D922K | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | ND | 19 ± 2 | ND | ID (?) |

| D923K | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 3.6, 4.6 | 33 ± 2 | 36, 39 | ID |

The abbreviations include: WT, wild type; ID, residue that binds to the inhibitory domain; LC, residue that binds to myosin light chain; and ND, not determined. The Km values for light chain and ATP with mutants E777K, E780R. and E821K were obtained from Herrine et al. (1992)

TABLE II. Kinetic properties of mutated rabbit skelteal muscle light chain kinases.

Mutagenesis, expression in COS cells, quantitation of expressed kinase in COS cell extracts, and measurements of kinetic properties of rabbit skeletal muscle MLCKs were performed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Values represent means ± S.E. for three to four experiments with lysates from at least two independent transfections. Values for [Ca2+]0.5, KCaM, Km for light chains and ATP, and Vmax were determined as described in Table I. [Ca2+]0.5 values were determined with skeletal muscle light chain.

| SmMLCK | [Ca2+]0.5 | Relative KCaM | SkLC Km | SmLC Km | Vmax | KmATP | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µm | nm | µm | µm | µmol 32P/min/mg | µm | ||

| WT | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 1.0 | 4 ± 1 | 13 ± 5 | 23 ± 5 | 340 ± 40 | WT |

| E300R (Sm700) | 0.29 ± 0.00 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 6 ± 1 | ND | 20 ± 2 | 333, 360 | WT |

| E374R (Sm774) | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 6 ± 2 | 9 ± 4 | 31 ± 3 | 100, 130 | ID |

| E377R (Sm777) | 0.25 ± 0.00 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 26 ± 3 | 455 ± 172 | 42 ± 2 | 410, 500 | ID/LC |

| E380R (Sm780) | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 8 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 42 ± 5 | 180, 200 | ID |

| DED384-386KKK (Sm784–786) | <0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 15 ± 1 | 28 ± 4 | 20 ± 0 | 300, 280 | ID |

| E421R (Sm821) | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 29 ± 2 | 527 ± 332 | 37 ± 2 | 310, 410 | ID/LC |

Abbreviations include: WT, wild type; ID, residue that binds to inhibitory domain; LC, residue that binds to smooth muscle regulatory light chain; SkLC, skeletal muscle regulatory light chain; SmLC, smooth muscle regulatory light chain ND, not determined. Km, values for light chains and ATP with mutants E374R, E377R, E380R, and E421R were obtained from Herring et al (1992). The mutants shown in parenthesis represent equivalent residues in the smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase.

Additional mutants residing in protein kinase subdomain V for both smooth muscle MLCK and skeletal muscle MLCK (SmE788K, SmE793K, Sm793A, SkE374R) and 1 in subdomain XI (SmD923K) had significant, decreases in [Ca2+]0.5 and KCaM values (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2; Table I and Table II). There were no significant changes in other catalytic properties, suggesting that these mutations specifically affect binding of the catalytic core to the inhibitory domain. Although the light chain Km was not directly determined for mutant SmE793K, it is assumed that the wild-type kinetics displayed by an alanine substitution of residue Glu-793 shows that this residue is not involved in light chain binding. There was a small decrease in the KCaM, value for the SmD922K mutant. Since this residue is adjacent to SmD923 which show, a 10-told decrease in KCaM when it is mutated, it is possible that the SmD922K mutation indirectly affects binding of SmD923 to the inhibitory domain.

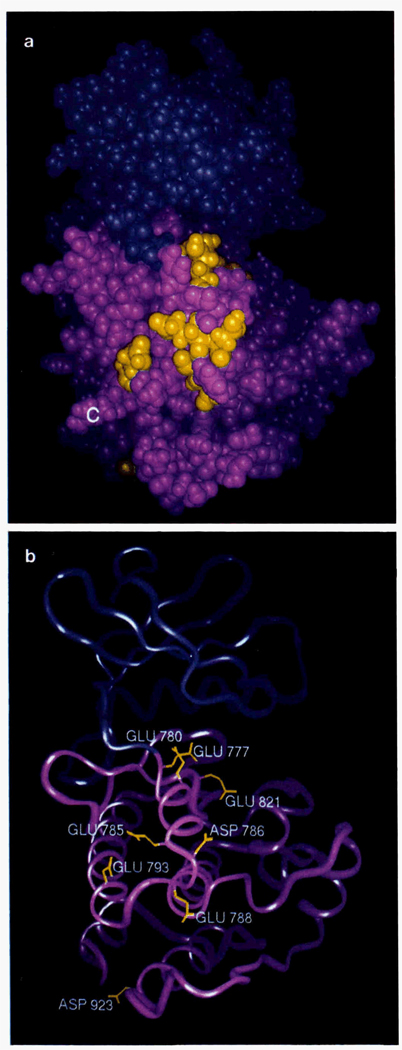

FIG. 2. Space-filling (A) and ribbon (B) models of the catalytic core of the rabbit smooth muscle MLCK.

The model displayed is derived from the chicken smooth muscle MLCK catalytic core model (Knighton et al., 1992) which was not altered, since there are only 10 residues different between the two kinases (Gallagher et al., 1990). The C terminus of the catalvtia core is shown in green (C) in the Space-filling model. The numbers displayed correspond to the residue numbers in rabbit smooth muscle MLCK. The positions of 8 acidic residues that bind to the inhibitor, domain (SmE777,SenE780, SmE785, SmD786, SmE788 SmE793, SmE821, SmD923) are displayed in yellow, and their side chains are shown on the ribbon model.

Two acidic residues in each MLCK (SmE777 and SmE821; SkE377 and SkE421) were identified previously as binding to the basic residue at the p-3 position in the smooth muscle light chain (Herring et al., 1992). Mutants SmE777K and SkE377R demonstrated small but significant decreases in [Ca2+]0.5 and KCaM values (Fig. 1, A and D; Table I and Table II). Mutants SmE821K and SkE421R exhibited marked decreases in [Ca2+]0.5 and KCaM, values (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2; Table I and Table II), Thus, these acidic residues near the catalytic site in both MLCKs also bind to the autoinhibitory region when the enzymes are inactive. SmE78OR had a significant decrease in KCaM and a 3-fold increase in the Km value for smooth muscle light chain. The change in Km for light chain is relatively minor compared with the 200- and 100-fold increases associated with mutations at residues SmE777 and SmE821, respectively. The side chains of SmE777 and SmE780 are close to each other (Fig. 2), and it is possible that substitution of residue SmE780 with a residue having a longer side chain (Arg) affects indirectly the binding of SmE777 to the light chain.

Mutant SmE771K and the corresponding mutant SkE371R were inactive (data not shown). A more conservative mutation, SmE771A, resulted in the expression of an active kinase with a significant decrease in [Ca2+]0.5 (Table I). However, the Vmax value was markedly decreased and Km for ATP increased. Inspection of the crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase shows that the carboxyl group in the main chain of corresponding residue Glu-121 forms a hydrogen bond to N6 of the adenyl ring of ATP (Zheng et al., 1993a; 1993b). This may explain the changes in the catalytic properties in the MLCK mutants.

Mutants SmE700R and SmD784K and SmE915K and SmD922K had properties of the wild-type MLCK for the measured kinetic parameters (Table I and Table II). Thus, some acidic residues within the catalytic core of MLCK located near acidic residues that bind the inhibitory domain can be mutated without altering activation properties.

DISCUSSION

Eight acidic residues have been identified within the catalytic core of the rabbit smooth muscle MLCK that are predicted to be involved in binding the inhibitory domain (SmE777, SmE780, SmE785, SmD786, SmE788, SmE793, SmE821, and SmD923; Table I). Six residues in the rabbit skeletal muscle MLCK have also been identified (SkE374, SkE377, SkE380, SkE385, SkD386, and SkE421R; Table II). Two of these residues in both MLCKs are important for binding to the smooth muscle light chain (SmE821 and SkE421; SmE777 and SkE377) (Herring et al., 1992). Fig. 2, A and B, show models of the catalytic core of smooth muscle MLCK (Knighton et al., 1992) with the linear distribution of these acidic residues across the surface of the lower lobe of the catalytic core. Residues SmE777, SmE780, and SmE821 are close to the active site, whereas the remaining residues are located at the base of the D helix (SmE785), in the loop region between the D and E helices (SmD786, SmE788), in the E helix (SmE793), and in the loop between the G and H helices (SmD923). Many of these acidic residues reside within subdomain V and VIa of the catalytic core.

These results represent the first experimental mapping of the ionic interactions involved in binding an autoinhibitory domain on the catalytic core of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. The path of the acidic residues suggested from the model of the autoinhibitory region (Knighton et al., 1992) has been confirmed in part. The acidic residues in the smooth muscle MLCK that are proposed to bind at p-6, p-7, and p-8 positions in the substrate were not mutated. However, 3 residues near the active site of the smooth muscle MLCK (SmE777, SmE780, SmE821) and by analogy in the skeletal muscle MLCK (SkE377R, Sk380, SkE421) were predicted in this recent model to bind to the autoinhibitory domain. The finding that 2 of these acidic residues also bind smooth muscle light chain substrate at the p-3 position is consistent with the pseudosubstrate hypothesis (Knighton et al., 1992). However, it should be noted that the skeletal muscle light chain, the natural substrate for the skeletal muscle MLCK, has a glutamate at p-3 rather than arginins. Thus, it is unlikely that both types of light chain will bind to the same residues in the catalytic core of the skeletal muscle MLCK. Other acidic residues that may form electrostatic interactions only with the inhibitory domain were identified (SmE785, SmD786, SmE788, SmE793, SmD923; SkE374R, SkE385, SkD386). Thus, the inhibitory domain extends beyond the region homologous to the light chain (Fitzsimons et al., 1992; Knighton et al., 1992; Shoemaker et al., 1990). The putative inhibitory domain binding residues identified in this study can be used to refine the position of the inhibitory domain and connecting region across the lower lobe of the catalytic core.

Six of the eight acidic residues in the smooth muscle MLCK identified in this study are conserved in the primary sequence of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Hanks et al. 1988). Four of the eight residues are found in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (Ohmstede et al., 1989; Means et al., 1991; Gallagher et al., 1992). Thus, the structural basis for autoinhibition of these kinases may be similar. One of the acidic residues in smooth muscle MLCK (SmE788) proposed to bind to the autoinhibitory region is not conserved in skeletal muscle MLCK (SkH388). Likewise, an acidic residue in the skeletal muscle MLCK (SkE374) is not conserved in the smooth muscle MLCK. Since the auto-inhibitory regions of the smooth muscle MLCK and skeletal muscle MLCK do not have identical primary sequences, it is not surprising that in addition to conserved residues that bind the inhibitory domain, there will be some interactions unique to the two kinases.

The acidic residues in the catalytic core that bind to the autoinhibitory domain can be predicted by measuring changes in the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent activation of the mutant kinases. This method of analysis should be applicable to other Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzymes. The greater challenge is to identify experimentally the interactions between specific acidic residues in the catalytic core and basic residues in the autoinhibitory domain to confirm that the residues identified in this study are directly involved in binding the autoinhibitory domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Li-Chu Hsu and Suzy Griffin for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association-Texas Affiliate (to B. P. H.) and by National Institutes of Health Great HL26043 (to J. T. S.).

The abbreviations used are: MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; KCaM, the concentration of calmodulin required for half-maximal activation of myosin light chain kinase; [Ca2+]0.5, concentration of Ca2+ required for half-maximal activation of myosin light chain kinase; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- Bagchi IC, Kemp BE, Means AR. Mol. Endocrinol. 1992;6:621–626. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.4.1584224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley ML, Penneypacker KR, Hoover CG, Brigati DJ, Kincaid R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:7585–7589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DK, Stull JT. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5608–5614. doi: 10.1021/bi00565a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DK, Stull JT. Biochemistry. 1982;21:2386–2391. doi: 10.1021/bi00539a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons DP, Herring BP, Stull JT, Gallagher PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:23903–23909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CJ, Johnston SA, Sunday B, Gaeta FC. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;280:397–404. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher PJ, Herring BP, Griffin SA, Stull JT. J. Biol. chem. 1991;266:23936–23944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks SK, Quinn AM, Hunter T. Science. 1988;241:42–52. doi: 10.1126/science.3291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway DR, Haeberle JR. Anal. BioChem. 1983;135:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90726-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring BP. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11838–11841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring BP, Fitzsimons DP, Stull JT, Gallagher PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:16588–16591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring BP, Gallagher PJ, Stull JT. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:25945–25950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BE, Pearson RB. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1094:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90027-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BE, Stull JT. In: Peptides and Protein Phosphorylation. Kemp BE, editor. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BE, Pearson RB, Guerriero V, Bagchi IC, Means AR. J Biol. Chem. 1987;262:2542–2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knighton DR, Pearson RB, Sowadski JM, Means AR, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS, Kemp BE. Science. 1992;258:130–135. doi: 10.1126/science.1439761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn ED, Hammer JA., III Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1988;17:23–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leachman SA, Gallagher PJ, Herring BP, McPhaul MJ, Stull JT. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4930–4938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means AR, Cruzalegui F, LeMagueresse B, Needleman DS, Slaughter GR, One T. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:3960–3971. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR, Silver PJ, Stull JT. Mol. Pharmacol. 1983;24:235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmstede C, Jensen K, Sahyoun N. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:5866–5875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker MO, Lau W, Shattuck RL, Kwiatkowski A, Matrisian PE, Guerra-Santos L, Wilson E, Lukas T, Van Eldik L, Watterson D. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:1107–1125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull JT, Hsu L-C, Tansey MG, Kamm KE. J. Biol Chem. 1990;265:16683–16690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney HL, Bowman BF, Stull JT. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:Cl085–C1095. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.5.C1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Knighton DR, Ten Eyck LF, Karlsson R, Xuong N, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Biochemistry. 1993a;32:2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/bi00060a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Trafny EA, Knighton DR, Xuong N, Taylor SS, Ten Eyck LF, Sowadski JM. Acta Crystallogr. 1993b;D49:362–365. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]