Abstract

The stereochemical course of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of an enantioenriched, α-substituted, allylic silanolate salt with aromatic bromides has been investigated. The allylic silanolate salt was prepared in high geometrical (Z/E, 94:6) and high enantiomeric (94:6 er) purity by a copper-catalyzed SN2’ reaction of a resolved allylic carbamate. Eight different aromatic bromides underwent cross-coupling with excellent constitutional site selectivity (γ) and with excellent stereospecificity. Stereochemical correlation established that the transmetalation event proceeds through a syn SE’ mechanism which is interpreted in terms of an intramolecular delivery of the arylpalladium electrophile through a key intermediate that contains a discrete Si–O–Pd linkage.

Introduction

The ability of transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions to unify carbon atoms at various levels of hybridization in myriad organic substrates distinguishes it from other carbon–carbon bond forming reactions. The pair wise combinations of alkyl, alkenyl, alkynyl, aryl, heteroaryl and allyl organometallic donors and organic electrophiles encompass all hybridizations of the carbon atom (sp3, sp2, and sp).1 However, a vast majority of transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions employ organic subunits of sp or sp2 hybridization at the reactive carbon and commonly do not form chiral products. Nevertheless, a multitude of asymmetric cross-coupling reactions for the enantioselective synthesis of chiral compounds can be envisioned, but the extraordinary potential of these constructs has not been realized.

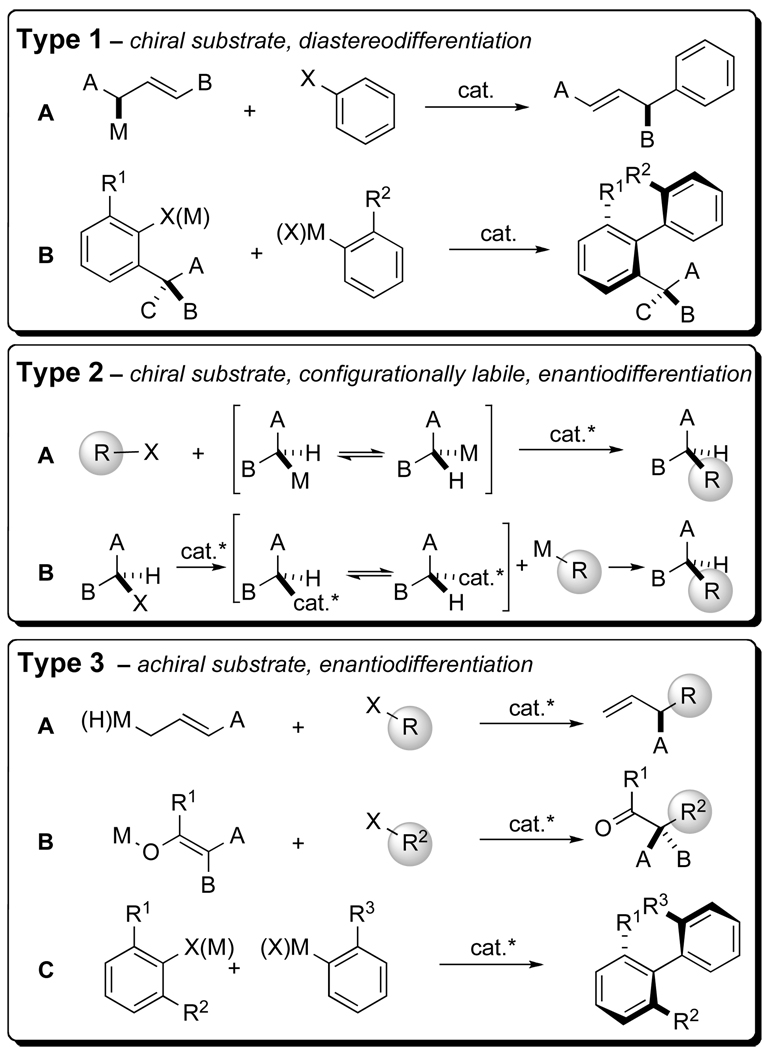

Those transformations in which a transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction creates a stereogenic element in the product can be classified into three general types (Figure 1).2,3,4 Type 1 represents the diastereoselective coupling of chiral, enantioenriched substrates by internal selection.5 Among the reactions of this type are palladium-catalyzed nucleophilic allylations (Type 1–A)6,7,8 including those reported in this work, and formation of atropisomeric biaryls (Type 1–B).9 Type 2 reactions employ chiral, configurationally labile substrates and afford enantiomerically enriched products through external selection5 by a chiral catalyst. Examples of this type include the coupling of secondary, benzylic Grignard reagents (Type 2–A),2c,d and nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of secondary alkyl bromides with organometallic donors based on silicon, boron, zinc, and indium (Type 2–B).10 Finally, Type 3 couplings constitute the reactions of achiral substrates and afford chiral, enantiomerically enriched products via external selection with a chiral catalyst. The majority of known asymmetric cross-coupling reactions fall into this category and include: the Heck reaction,11 allylations of organic electrophiles with allylic organometallic donors (both Type 3–A),12 arylation of enolates (Type 3–B)13 and formation of atropisomeric biaryls (Type 3–C).14

Figure 1.

General classification of asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

The organization of these reactions in this manner provides a clear view of the stereochemical landscape and makes apparent not only the significant achievements but also the opportunities for development of asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Specifically, the lack of reports on allylic cross-coupling reactions of Type 1–A and Type 3–A represents a deficiency, and for good reason. These reactions require control over both constitutional site selectivity (i.e. α– vs. γ–coupling) in addition to either diastereo- or enantiodifferentiation.15 Moreover, a study of the stereodifferentiating steps in Type 1–A processes would provide important insights for the development of catalytic, enantioselective variants of Type 3–A.

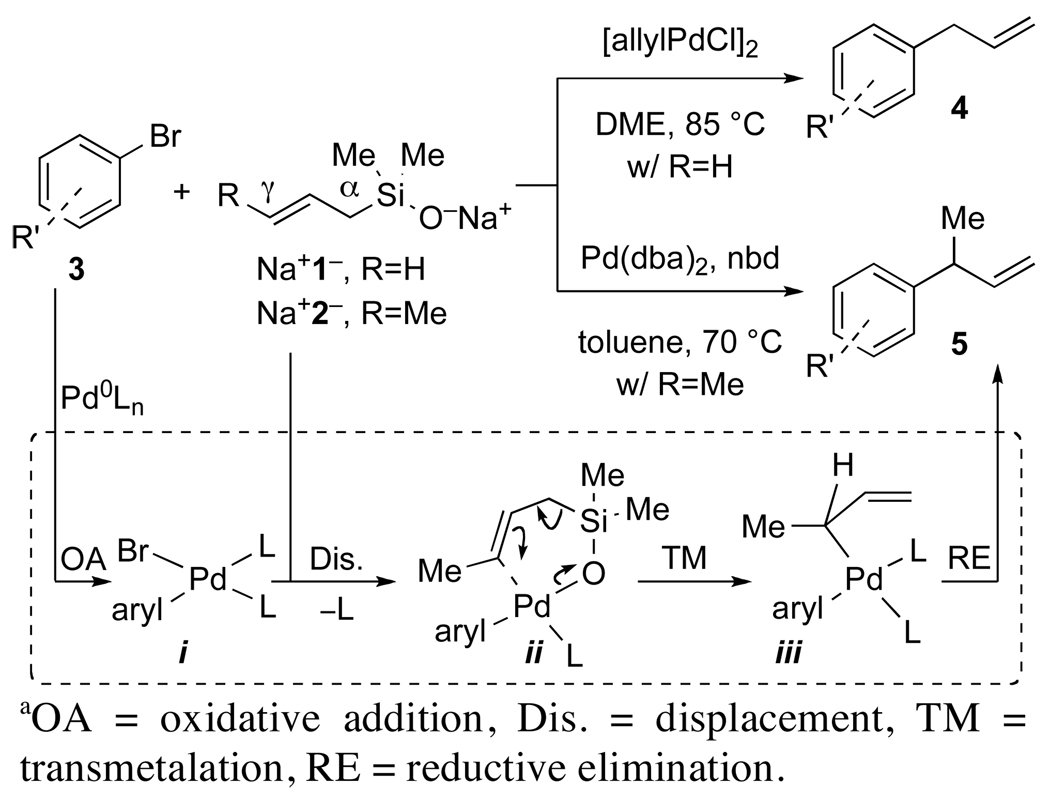

In this context, we recently reported the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of allylic silanolate salts with aromatic bromides (Scheme 1).16 Sodium allyldimethylsilanolate Na+1− undergoes cross-coupling with aromatic bromides without the need for external activators (fluoride)6a,b or added ligands (phosphine). In addition, the coupling of sodium 2-butenyldimethylsilanolate Na+2− affords the γ-coupled products 5 with high site-selectivity when the olefinic ligands dibenzylideneacetone (dba) and norbornadiene (nbd) are used. The results of these studies are interpreted in terms of a closed, SE’ transmetalation of the arylpalladium(II) silanolate ii, followed by facile reductive elimination from iii facilitated by the π-acidic dba ligand to afford 5 with high γ-selectivity.

Scheme 1a.

The selective formation of the chiral, γ-coupled product 5 under the influence of dba and nbd naturally suggested the possibility of setting this center enantioselectively through the influence of chiral, olefinic ligands (i.e. a Type 3 reaction). However, the use of Na+2− in asymmetric catalysis represents a significant challenge because the chiral olefin ligand must not only control the enantioselectivity of the coupling,17,18 but also the site-selectivity of C–C bond formation. Thus, to achieve this goal we felt it prudent to first establish the geometrical details of the (putative) stereochemistry determining transmetalation step by investigating a diastereoselective reaction of Type 1. This paper describes the synthesis of enantioenriched α-substituted allylic silanolate salts and the determination of the stereochemical course of their cross-coupling with aromatic bromides.

Background

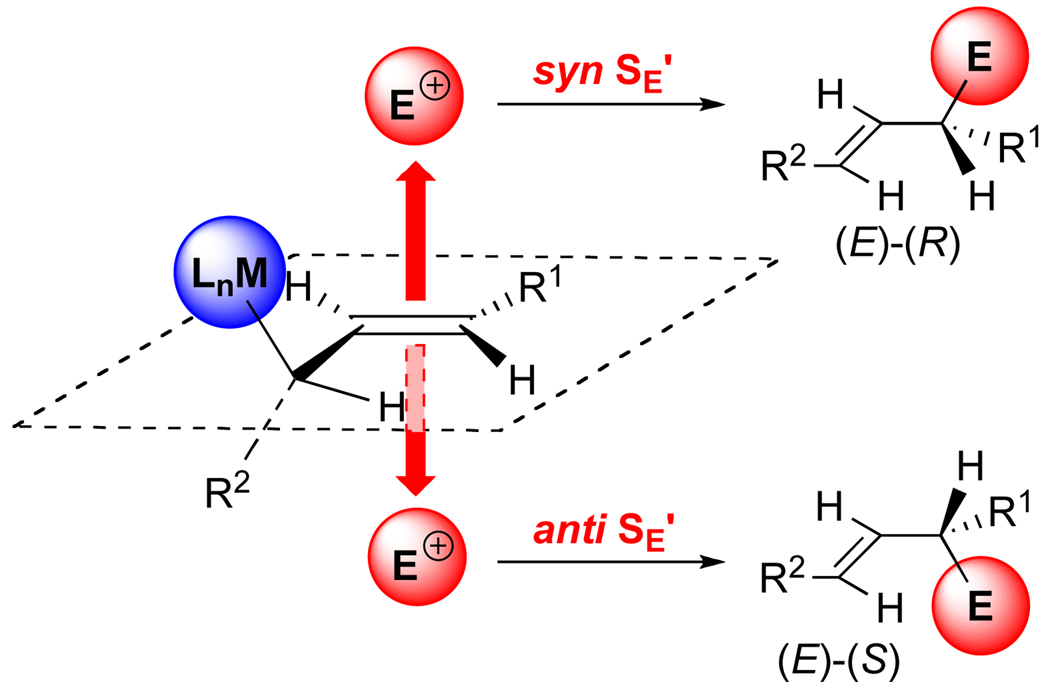

The stereochemical course of an analogous reaction, namely the addition of allylic silanes and allylic stannanes to aldehydes, has been thoroughly investigated in these and other laboratories.5 These studies established that the two stereochemically defining factors of the allylation reaction are: (1) the pair wise diastereoselection between the faces of the reacting double bonds (i.e. relative topicity), and (2) the disposition of the electrofuge (MLn) with respect to the attacking electrophile (SE’ process). For the allylations studied herein, only the latter feature is relevant (Figure 2). To determine the orientation of MLn during the electrophilic attack, two attributes of the product must be established: (1) the configuration of the resulting double bond and (2) the configuration of the newly created stereogenic center. The fundamental stereoelectronic requirement is that the C–MLn bond be oriented such that overlap with the double bond is strong (i.e. ±30° from perpendicular to the atomic plane). To satisfy this stereoelectronic requirement and avoid A1,3 strain, the acyclic, allylic organometallic reagent reacts via a conformation in which the allylic hydrogen atom eclipses the double bond as shown in Figure 2.19 The electrophile can then approach the defined half-space which contains the electrofuge (syn SE’) or the half-space opposite to that occupied by the electrofuge (anti SE’). The configurations of the new stereogenic center and carbon-carbon double bond are therefore dependent upon the conformation of the allylic moiety and the direction of electrophile attack relative to the electrofuge. For allylmetal-aldehyde addition reactions promoted by Lewis acids, the stereochemical course is overwhelmingly anti-SE’,20 though with other electrophiles in sterically biased systems, syn-SE’ processes are known.21

Figure 2.

Stereochemical control elements in SE’ reactions (CIP: E > CH=CH > R1).

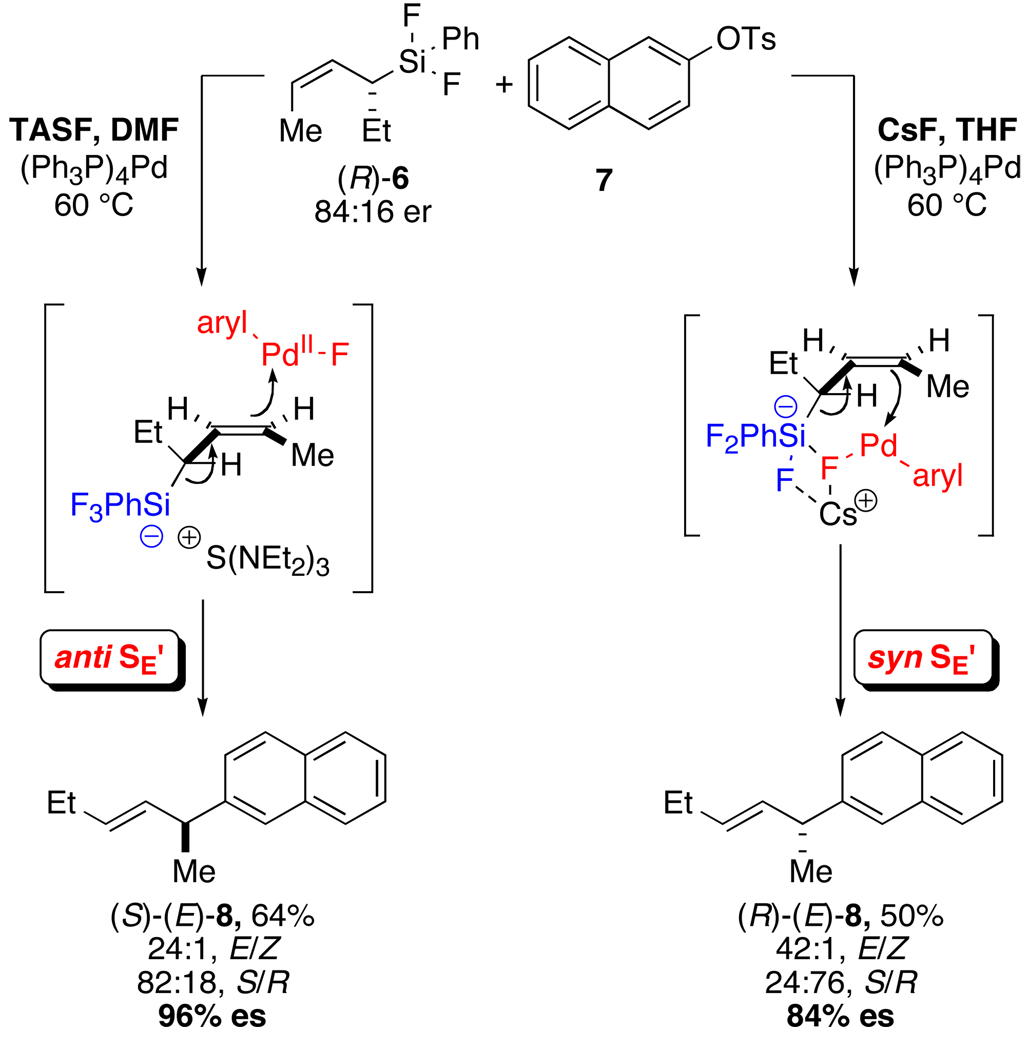

Of greater relevance to the reaction at hand, studies on the stereochemical course of palladium-catalyzed substitution of allylic organometallic reagents with aromatic electrophiles are far more scarce. In 1994, Hiyama reported that in the reaction of enantioenriched allyldifluorophenylsilanes with aryl tosylates under palladium catalysis, two mechanisms are operative and depend on the fluoride source and the solvent (Scheme 2).6a For example, the combination of (R)-6, aryl tosylate 7, tris(dimethylamino)sulfonium difluorotrimethylsilicate (TASF) in DMF leads to the formation of (S)-(E)-8 via an anti-SE’ pathway. However, when CsF and THF are used (R)-(E)-8 predominated (via a syn-SE’ pathway), albeit with attenuated enantiospecificity (es).22 These results are explained by the operation of an open mechanism for the reaction with TASF and a closed mechanism involving a Pd–F–Si interaction for reaction with CsF.

Scheme 2.

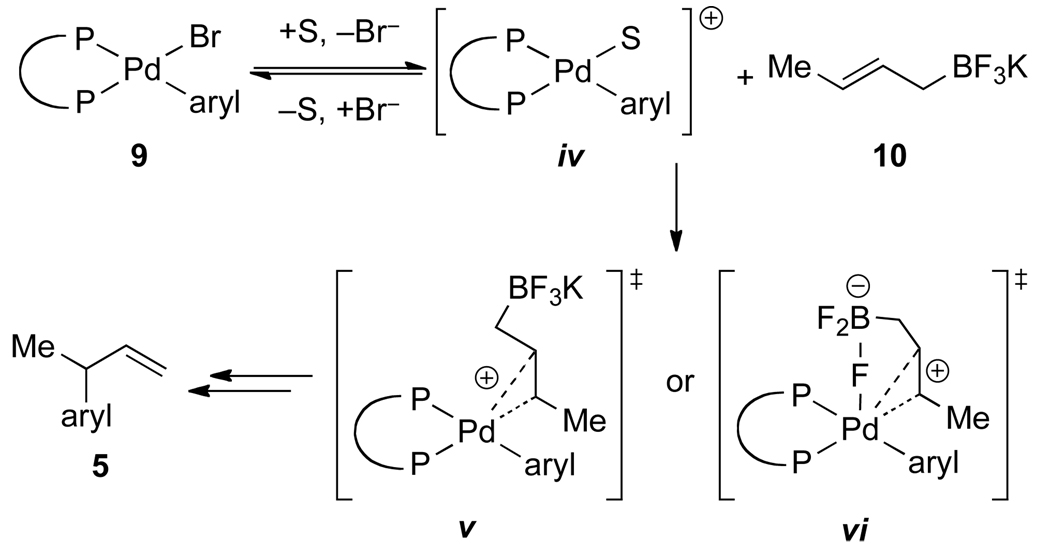

Miyaura and Yamamoto investigated the details of the transmetalation and enantioselection in the cross-coupling of crotyltrifluoroborates with aromatic bromides (Scheme 3).12c Hammett studies displayed a small negative ρ-value (−0.50) for the reaction of five electronically-differentiated, preformed arylpalladium complexes 9 (containing bis(di-tert-butylphosphino) ferrocene) with (E)-crotyltrifluoroborate 10. These results are interpreted to imply formation of a cationic palladium(II) species iv prior to transmetalation. DFT calculations suggest that this process occurs by an open SE’ process through transition state structure v, because the closed transition state structure vi was slightly higher energy (+2.0 kcal/mol) in THF. The position of the palladium electrophile relative to the orientation of the trifluoroborate electrofuge (syn or anti SE’) was not established.

Scheme 3.

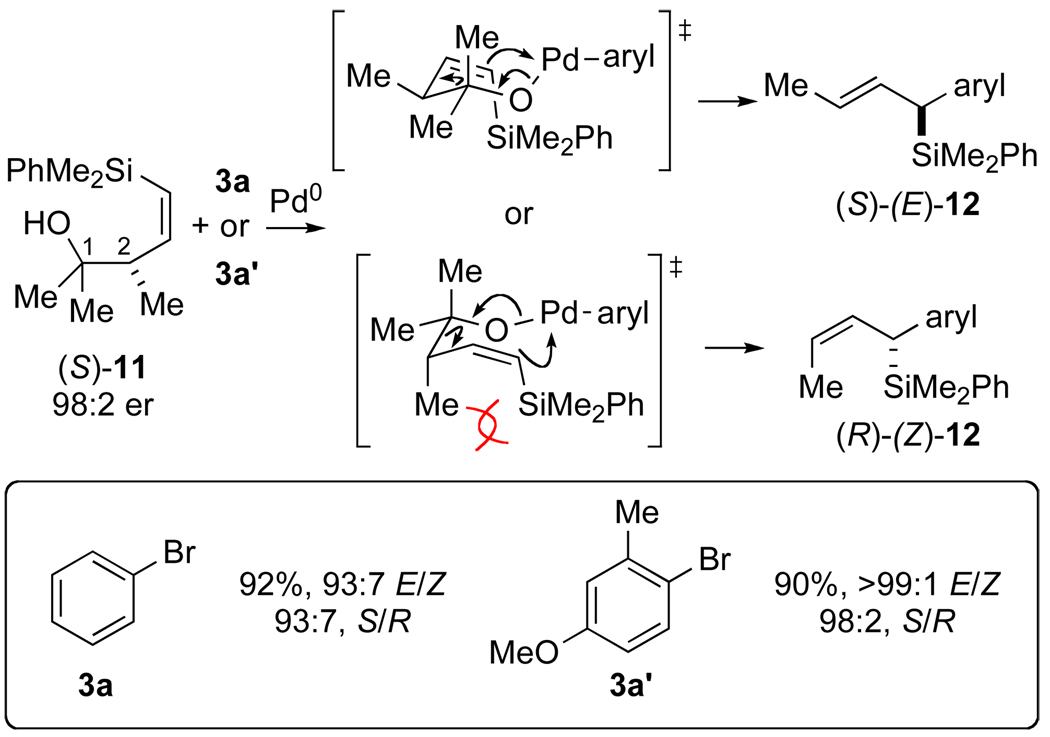

A recent communication from Oshima and Yorimitsu describes the diastereoselective synthesis of (arylalkenyl)silanes by retroallylation of homoallylic alcohols such as (S)-11 in the presence of arylpalladium halides (Scheme 4).7 The authors propose a closed, chair-like SE’ transition state structure with the C(2) methyl group oriented in a pseudo-equatorial position preventing unfavorable 1,3-diaxial steric interactions with the silicon substituent. However, only aryl bromides bearing ortho-substituents afforded products with high diastereoselectivities.

Scheme 4.

The goal of the current work was to determine the stereochemical course of the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of allylic silanolate salts with aromatic bromides. To this end, enantioenriched α-substituted allylic silanolate salts were synthesized, cross-coupled with aromatic bromides, and the stereochemical course of the cross-coupling reaction determined. These studies provide a refined picture of the geometric details of the critical transmetalation step.

Results

1. Synthetic Strategy to Access Enantiomerically Enriched α-Substituted Allylic Silanolate Salts

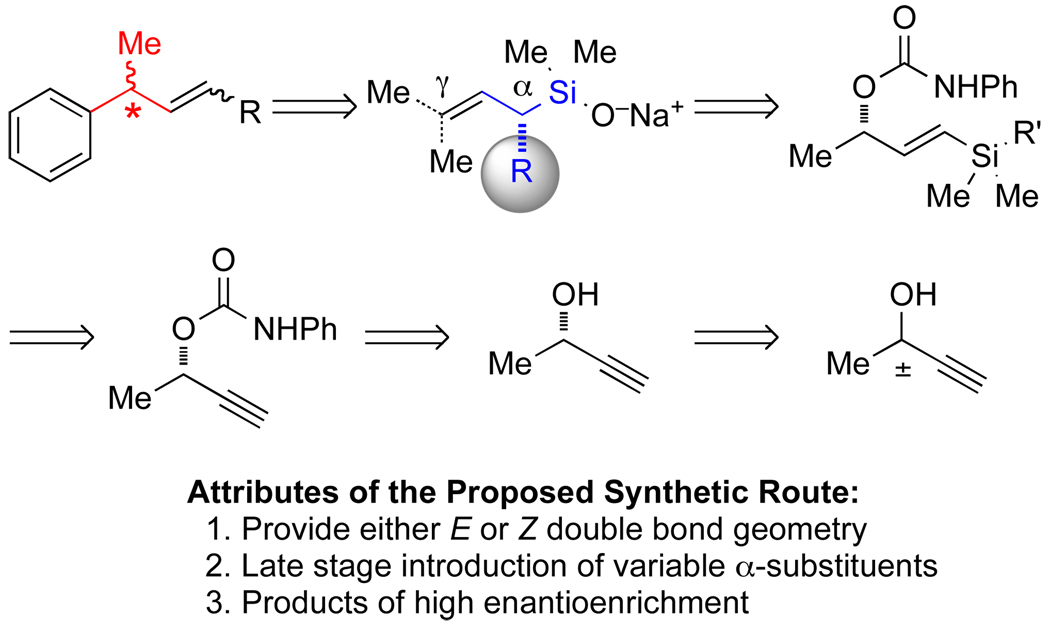

A flexible synthetic route to α-substituted allylic silanolate salts in enantiomerically pure form was required to establish the stereochemical course of their transmetalation in palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. In anticipation of the possible challenges that could be encountered in this endeavor (including, but not limited to, low enantiomeric purity of the silanolate, low site-selectivity of the coupling, and low asymmetric induction of the coupling reaction), a modular route was sought in which structural variation of the α-substituted silanolate would be facile. Specifically, the route should allow access to either geometry of the allylic double bond, various α-substituents, and high enantiomeric purity of the products (Figure 3). Among several synthetic strategies considered, the copper-catalyzed SN2’ reaction of allylic carbamates23 with various nucleophiles was identified to meet these criteria for several reasons: (1) the precursor to the SN2’ reaction can be synthesized in enantiomerically pure form from readily available starting materials, (2) both E and Z terminally substituted allylic silanes can be prepared from this precursor depending upon the organometallic nucleophile used, and (3) the SN2’ reaction permitted a variety of α-substituents to be installed with high enantiomeric purity at a late stage in the synthesis. However, in view of the strongly basic conditions needed to carry out the SN2’ reaction (organolithium base and organomagnesium nucleophile) a masked or protected silanol would be required. Ultimately, the silanol would be unveiled, converted to the sodium salt, and the stereochemical course of the cross-coupling reaction determined.

Figure 3.

Synthetic Strategy to Determine the Stereochemical Course of Transmetalation.

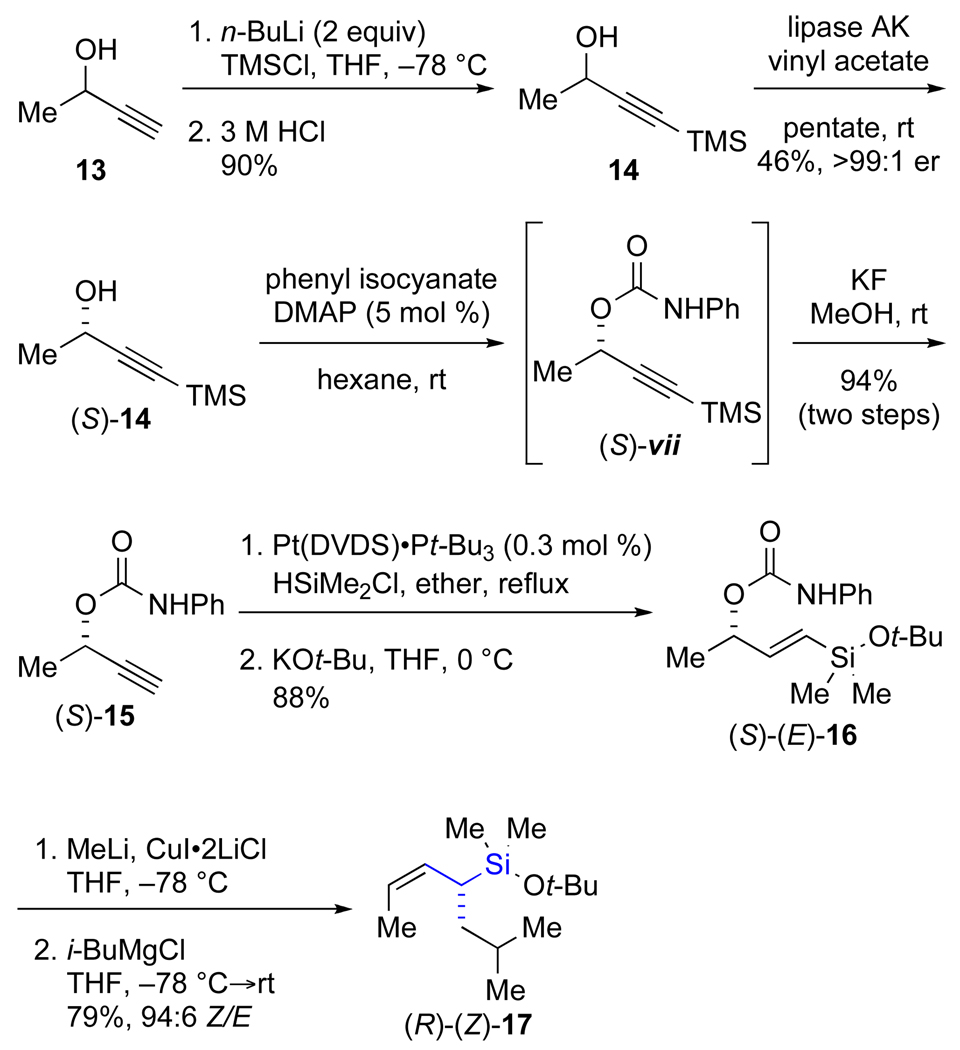

2. Synthesis of the α-Substituted Allylic Silane

The synthesis of the α-substituted allylic silane commenced with preparation of 4-trimethylsilyl-3-butyn-2-ol (14) by double deprotonation of 3-butyn-2-ol (13) with n-butyllithium, addition of TMSCl, and work-up with 3 M HCl to provide 14 in 90% yield (Scheme 5).24 Lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of 14 provided (S)-14 in 46% yield and >99:1 er.25 The phenyl carbamate necessary for SN2’ displacement was installed by treatment of (S)-14 with phenyl isocyanate and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) in hexane at room temperature. The TMS group, required for high selectivity in the kinetic resolution, was then cleaved in situ with potassium fluoride in methanol to provide (S)-15 in 94% yield. Platinum-catalyzed hydrosilylation26 of (S)-15 with dimethylchlorosilane, followed by substitution of the chloride with potassium tert-butoxide afforded the protected vinylic silanol (S)-(E)-16 (the precursor to the SN2’ reaction) in 88% yield over the two-step sequence.

Scheme 5.

The SN2’ reaction was carried out under conditions developed by Woerpel without further optimization.23d iso-Butylmagnesium chloride was chosen as the nucleophile because it provides good yields and high geometrical purity of the allylic silane product.23c,d Also, the steric bulk of the iso-butyl group should assure a high selectivity for the formation of an E double bond in the product of the cross-coupling reaction (later in the synthetic sequence) and thereby simplify the interpretation of the transmetalation. Thus, the SN2’ reaction was effected by deprotonation of the phenyl carbamate with methyllithium at −78 °C, followed by addition of copper iodide and i-BuMgCl to provide the protected allylic silanol (R)-(Z)-17 in good yield (79%), and high geometrical purity (94:6, Z/E) as determined by capillary gas chromatography.

3. Synthesis of the α-Substituted Allylic Silanolate Salt and Derivatization for Enantiomeric Analysis

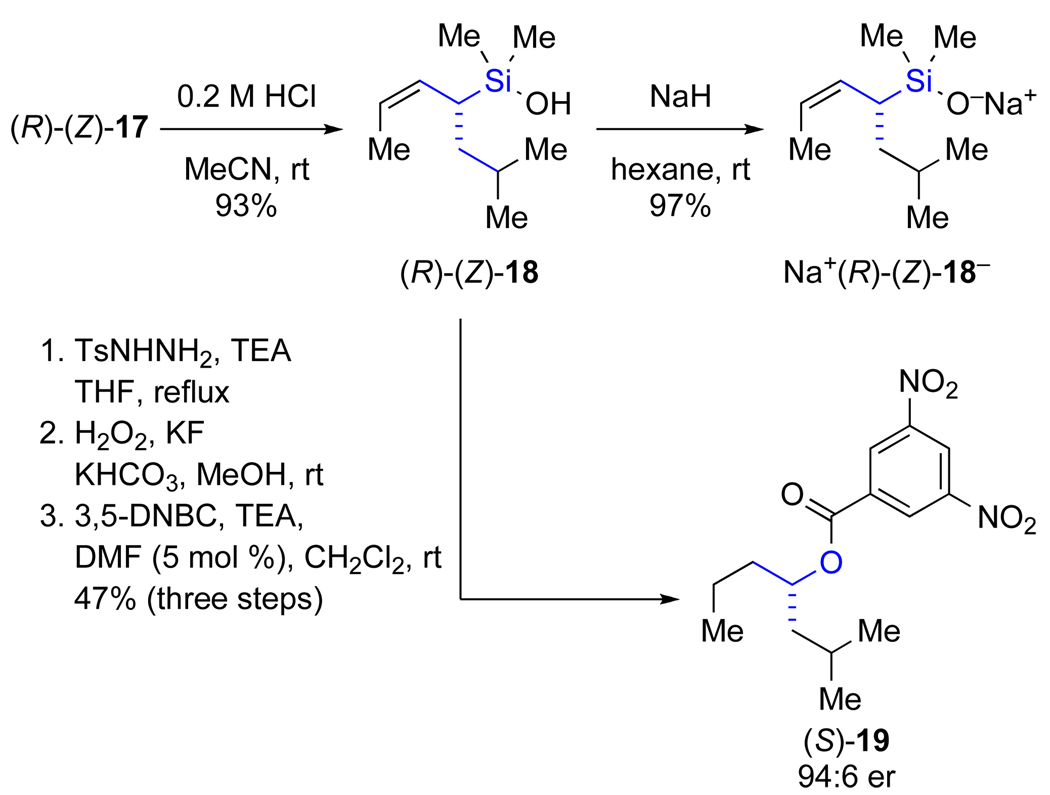

At this point all batches of (R)-(Z)-17 were combined for the synthesis of the silanol, derivatization for enantiomeric analysis, and to provide silanolate of uniform enantiomeric and geometrical purity for the cross-coupling reactions. The tert-butyl protecting group was readily removed with 0.2 M HCl to afford a 93% yield of the α-substituted allylic silanol (R)-(Z)-18 (Scheme 6).27 Chemical degradation of (R)-(Z)-18 provided material suitable for determination of enantiomeric composition and absolute configuration.28 This transformation was accomplished by diimide reduction,29 Tamao-Fleming oxidation,30 and esterification to afford the 3,5-dinitrobenzoate (DNB) of (S)-2-methylheptan-4-ol ((S)-19).31 The DNB (S)-19 was determined to be 94:6 er by chiral stationary phase, super critical fluid chromatography (CSP-SFC) and the absolute configuration of the stereogenic center was assigned by comparison of optical rotation data.32 The correlation of the R configuration of 18 along with its enantiomeric and geometric composition is congruent with the stereochemical model proposed for the copper-catalyzed SN2’ reaction of Grignard reagents with allylic carbamates.23d The remaining silanol (R)-(Z)-18 was then deprotonated with washed sodium hydride in hexane to provide Na+ (R)-(Z)-18− as a stable, free-flowing, powder in 97% yield.

Scheme 6.

4. Optimization of the Cross-Coupling Reaction

The cross-coupling of Na+(±)-(Z)-18−33 was first attempted using the conditions optimized for the reaction of sodium 2-butenyldimethylsilanolate (Na+2−).16 Thus, Na+(±)-(Z)-18−, bromobenzene, Pd(dba)2, and nbd were combined in toluene and heated to 70 °C in a pre-heated oil bath (Table 1, entry 1). Surprisingly, these conditions provided the allylated product with only modest γ-selectivity.34 Previous studies had established that increasing the π-acidity of the olefinic ligand increased the γ-selectivity of the coupling reaction.16 Gratifyingly, when only 5 mol % of (4,4’-trifluoromethyl)-dibenzylideneacetone35 22 was employed with allylpalladium chloride dimer (APC) as the pre-catalyst, an increase in γ-selectivity was observed (entry 2). Increasing the ligand loading to 20 mol % (4.0 equiv/Pd) further increased the γ-selectivity of the reaction (entry 3). Moreover, the loading of APC could be reduced to 0.5 mol % while maintaining high yield (entry 4). However, to preserve high γ-selectivity, the loading of 22 with respect to the limiting reagent (3a) needed to be kept at 20 mol % regardless of the palladium loading (entries 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Cross-Coupling Reaction Optimizationa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Pd source |

loading, % | ligand | loading, % | yield,b % | (E)-20a/21ac |

| 1d | Pd(dba)2 | 5.0 | nbd | 5.0 | 76 | 6.2:1 |

| 2 | APC | 2.5 | 22 | 5.0 | 74 | 8.6:1 |

| 3e | APC | 2.5 | 22 | 20 | 75 | 33:1 |

| 4 | APC | 0.5 | 22 | 10 | 70 | 14:1 |

| 5 | APC | 0.5 | 22 | 20 | 84 | 32:1 |

Reactions performed on 0.25 mmol scale.

Yield of (E)-20a determined by GC analysis.

Peak area ratio of crude reaction mixture determined by GC analysis.

2.0 equiv Na+(±)-(Z)-18− used.

Average of 3 experiments.

5. Preparative Cross-Coupling Reactions of the α-Substituted Allylic Silanolate Na+(R)-(Z)-18−

The optimized conditions for reaction of Na+(±)-(Z)-18− [(1.5 equiv), aryl bromide 3 (1.0 equiv), APC (0.5–2.5 mol % w.r.t. 3), and 22 (20 mol % w.r.t. 3) in toluene at 70 °C] were then employed in the cross-coupling of enantioenriched allylic silanolate Na+(R)-(Z)-18− (94:6 er) with a variety of aromatic bromides (Table 2). The substrates chosen for these experiments were selected to illustrate scope of compatible aryl bromides including unsubstituted, ortho-substituted, electron-rich, electron-poor, and heteroaromatic bromides. Bromobenzene (3a) (entry 1), along with electron-rich (entry 5) and electron-poor (entry 7 and 8) aryl bromides without sterically biasing substituents in the ortho position provided good yield and high isomeric purity favoring the E-γ coupled product (87–98% E-γ). Likewise, aromatic bromides with ortho substitution cross-coupled in good yield and isomeric purity (entries 2–4). In addition, a heteroaromatic bromide cleanly coupled to afford the E-γ coupled product selectively (entry 6).

Table 2.

Preparative Cross-Couplings of Na+(R)-(Z)-18−a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | time, h | yield,b % | E-γ,c % |

| 1d |  |

24 | 76 | 98 |

| 2e |  |

6 | 70 | 95 |

| 3e |  |

6 | 78 | 90 |

| 4e |  |

12 | 66 | 91 |

| 5e |  |

6 | 67 | 97 |

| 6e |  |

6 | 73 | 94f |

| 7e |  |

6 | 76 | 92 |

| 8e |  |

6 | 73 | 87 |

Reactions performed on 2.0 mmol scale.

Yield of isolated analytically pure material.

Ratio of the E-γ isomer relative to E-α, Z-γ, and/or Z-α isomer(s) of purified products determined by GC analysis.

0.5 mol % APC used.

2.5 mol % APC used.

Determined 1H NMR analysis (103:1 S/N).

6. Derivatization of Cross-Coupled Products for Enantiomeric Analysis

The products of the preparative cross-coupling reactions required derivatization for determination of enantiomeric composition and absolute configuration. For this purpose, the allylic arenes (R)-(E)-20a–e and (R)-(E)-20g–h were transformed to 2-arylpropanols (S)-23a–e and (S)-23g–h by ozonolysis followed by in situ ozonide reduction with sodium borohydride. The enantiomeric ratios of the 2-arylpropanols were then determined by CSP-SFC analysis. Significantly, five of the substrates examined were of 98:2 er (Table 3, entries 1–3, 5, and 7), and the other three were of ≥99:1 er (entries 4, 6, and 8). In addition, derivatization produced five 2-arylpropanols with known optical rotations and assigned absolute configurations (entries 1, 3–5, and 7), and thus allowed for unambiguous assignment of the configuration of the benzylic stereogenic center.

Table 3.

Cross-Coupled Product Derivatization and Enantiomeric Analysis

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yield,a % | erb | [α]Dc | lit. [α]D |

| 1 | 23a | 66 | 98:2 | −14.2 | −11.7, (S)d |

| 2 | 23b | 59 | 98:2 | −5.32 | N/A |

| 3 | 23c | 72 | 98:2 | +26.5 | +19.2, (S)e |

| 4 | 23d | 53 | 99:1 | +5.27 | −4.1, (R)f |

| 5 | 23e | 75 | 98:2 | −15.5 | −15.4, (S)g |

| 6h | 20f | N/A | >99:1 | −10.9 | N/A |

| 7 | 23g | 47 | 98:2 | −14.1 | +13.3, (R)i |

| 8 | 23h | 60 | >99:1j | −10.0 | N/A |

Yield of isolated, purified material.

Determined by chiral SFC analysis of silica gel chromatographed products.

See Supporting Information for details.

Ref. 36.

Ref. 37.

Ref. 38.

Ref. 39.

Derivatization was not necessary for enantiomeric analysis.

Ref.40.

Further derivatization of the alcohol to a 3,5-dinitrophenylcarbamate was necessary for enantiomeric analysis.

Discussion

To determine the stereochemical course of the cross-coupling of allylic silanolate salts, enantioenriched α-substituted allylic silanolate Na+(R)-(Z)-18− was synthesized and coupled with aromatic bromides under palladium catalysis. The starting silanol, (R)-(Z)-18, and the crotylation products, (R)-(E)-20a–e and (R)-(E)-20g–h, were degraded to known materials to establish their enantiomeric compositions and assign their absolute configurations. These synthetic sequences allowed the process of diastereodifferentiation15 and thus enantiospecificity of the cross-coupling reaction to be determined. The products of the cross-coupling reaction, (R)-(E)-20a–h, from enantioenriched Na+(R)-18− were of high enantiomeric and geometrical purity. In addition, these compounds all possessed the same absolute configuration at the stereogenic center (R) and geometry of the double bond (E), suggesting a common pathway for the transmetalation of allylic silanolates and a direct relationship between the educt and the product.

1. Site-Selectivity of the Cross-Coupling of Na+(R)-(Z)-18−

The cross-coupling Na+(R)-(Z)-18− with aromatic bromides produced the E-γ coupled isomer with high selectivity, although the quantity and number of isomeric products varied depending upon the aryl bromide employed. For example, very high E-γ-selectivities were observed for bromobenzene (98% E-γ) and 4-bromoanisole (97% E-γ), and the lowest E-γ-selectivity was observed with 4-bromobenzotrifluoride (87% E-γ). These results are similar to those previously reported wherein aryl bromides bearing electron withdrawing substituents afforded lower γ-selectivity (i.e. increased α-coupling) when π-acidic olefin ligands were used to facilitate reductive elimination.16 Moreover, the reaction of bromobenzene with Na+(R)-(Z)-18− produced only two isomers as determined by capillary GC. The minor isomer was the α-coupled product as determined by 1H NMR analysis of a cross-coupling carried out under less γ-selective conditions (Pd(dba)2, nbd).41 Chemical degradation of the products (S)-23a–e and (S)-23g–h allowed for the removal of the α-coupled isomer(s), and therefore, their presence did not complicate the stereochemical analysis of the γ-coupled products.

2. Stereospecificity of the Cross-Coupling of Na+(R)-(Z)-18−

The products of the cross-coupling reaction were degraded for determination of enantiomeric composition and absolute configuration. Five of the seven derivatives were known compounds with reported optical rotations and assigned absolute configurations. Therefore, an unambiguous assignment of S to the configuration of the benzylic stereogenic center of 23a, 23c–23e, and 23g was possible by comparison of the sign of their optical rotations.42 The enantiomeric analysis of the 2-arylpropanols and (R)-(E)-20f by CSP-SFC revealed very high enantioenrichment (>98:2 er). Thus, the conversion of silanolates Na+(R)-(Z)-18− to the cross-coupling products (R)-(E)-20 occurred with complete enantiospecificity.22,43

3. Mechanistic Considerations

Previous studies in these laboratories on the cross-coupling of alkenyl-44 and arylsilanolates,45 have led to the formulation of a mechanism which involves the formation of an arylpalladium silanolate by attack of the starting silanolate salt on the arylpalladium(II)halide. The intermediacy of a discrete species containing an Si–O–Pd linkage has since been demonstrated in a number of different cross-coupling reactions.46 Moreover, evidence for an Si–O–Pd containing intermediate in the cross-coupling of allylic silanolates was also forthcoming during optimization of the reactions with Na+2−.16 Specifically, when t-Bu2P(2-biphenyl) was used in combination with Pd(dba)2 as the catalyst, only trace amounts of products resulting from carbon–carbon bond formation were observed; the major product of the reaction was the result of carbon–oxygen bond formation. This result is interpreted in terms of a direct reductive elimination of the arylpalladium(II) silanolate which precludes transmetalation.

4. Stereochemical Analysis

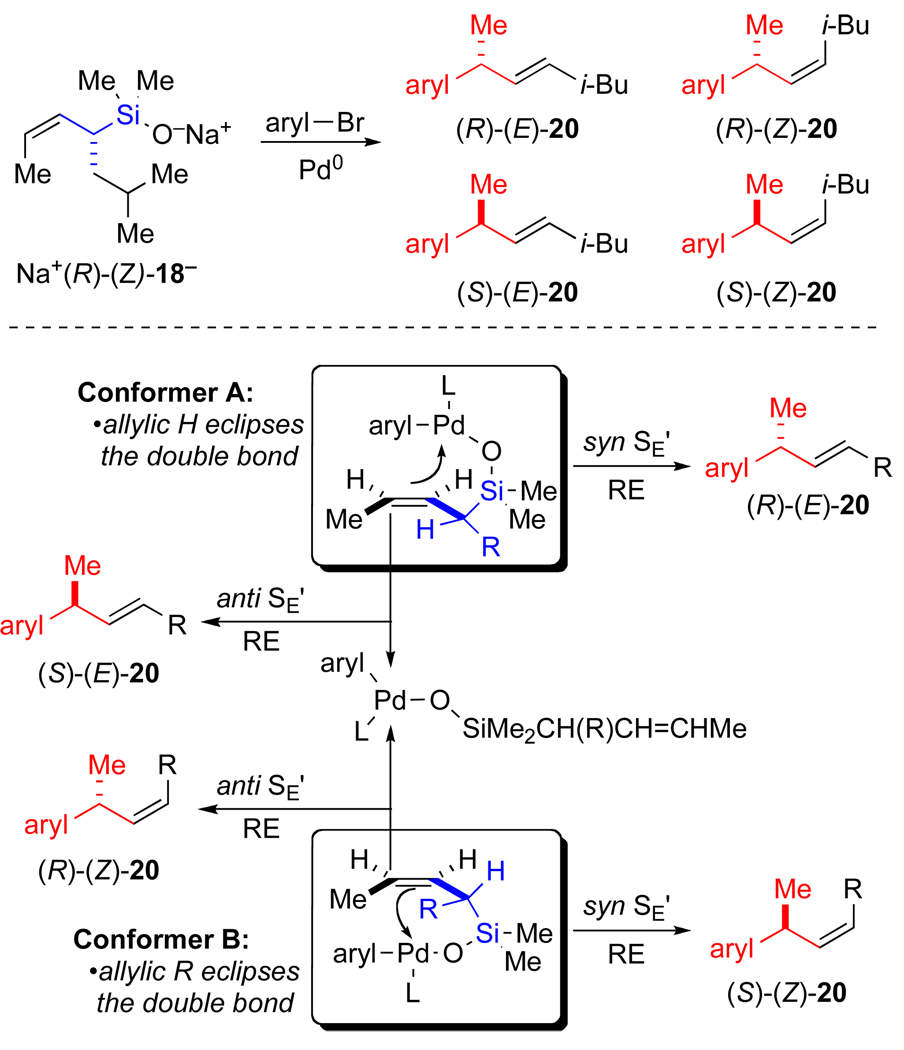

Four diastereomeric 1-methyl-iso-heptenyl arenes can be formed from a γ-selective coupling of Na+(R)-(Z)-18− (Figure 4). These four products represent pair wise combinations of the two possible olefin geometries and the two possible configurations at the newly generated stereocenter which in turn are established by: (1) the reactive conformation of Na+(R)-(Z)-18− in the transmetalation and (2) the stereochemical course of the SE’ process (syn or anti). Figure 4 illustrates the consequences of these two variables operating independently. In limiting conformer A, the hydrogen on the stereogenic center is in the olefin plane which will lead to the formation of an E double bond in the product. An intramolecular transmetalation corresponds to a syn SE’ pathway and leads to the formation (R)-(E)-20. Alternatively, an intermolecular transmetalation can proceed via both syn and anti SE’ pathways to afford both (R)-(E)-20 and (S)-(E)-20, although the anti process is expected to be favored on the basis of extensive precedent (see Background section). In limiting conformer B, the iso-butyl group is syn-planar to the olefin which will lead to the formation of a Z double bond in the product. Application of the same analysis to conformer B predicts the formation of (S)-(Z)-20 from an intramolecular transmetalation (syn SE’), or both (S)-(Z)-20 and (R)-(Z)-20 from an intermolecular transmetalation, the latter arising from an anti SE’ pathway.

Figure 4.

Possible pathways for the transmetalation of allylic silanolates. (R = i-Bu, RE = reductive elimination).

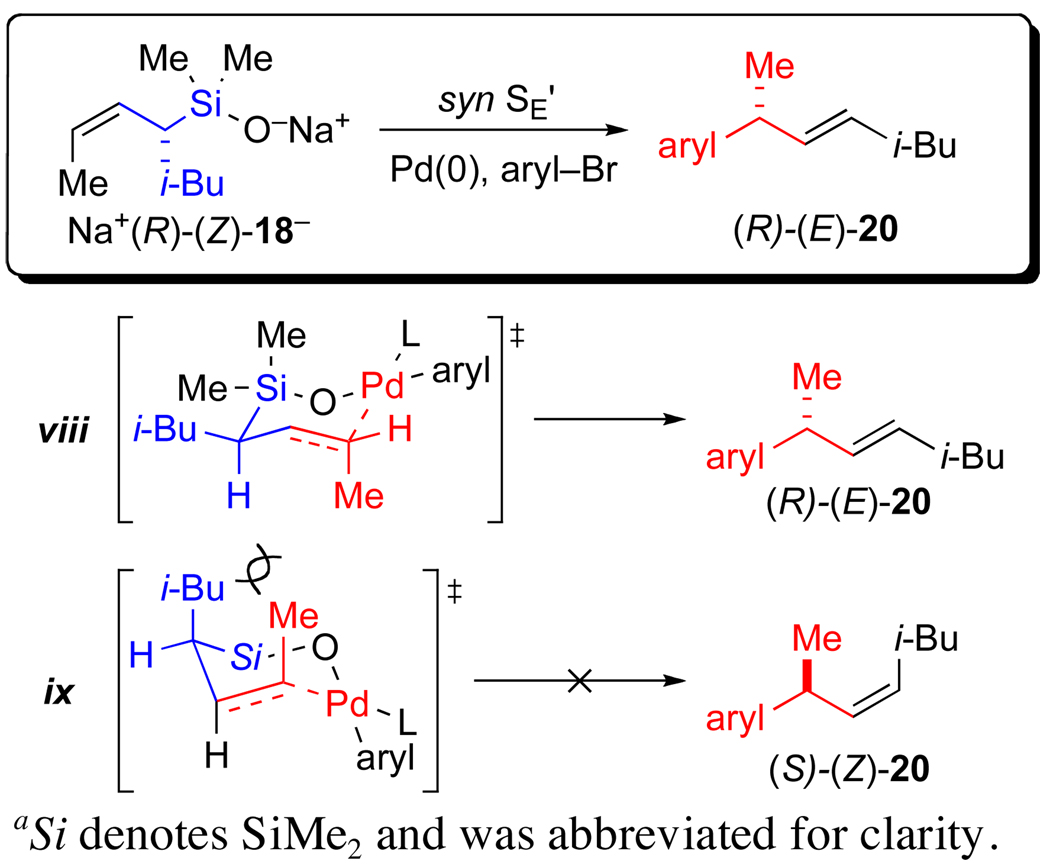

From the results described above, we established that the product from all cross-coupling reactions possessed the structure (R)-(E)-20 and is thus believed to arise from an intramolecular transmetalation via limiting conformer A through a syn SE’ process. A more detailed view of a transition state structure that leads to (R)-(E)-20 is illustrated in Scheme 7. Under the assumption that a syn SE’ pathway arises from an intramolecular transmetalation, a chair-like, transition state structure can be considered. In structure viii, the Si–O–Pd linkage controls the delivery of the palladium electrophile to the γ-terminus of the allylic silane. The palladium is tricoordinate and the alkene takes up the fourth coordination site in the square planar complex. Although a true chair is not realistically feasible, nevertheless, a critical feature is the pseudo-equatorial orientation of the iso-butyl group which assures high selectivity in the formation of an E double bond in the product. In addition, the allylic methyl group is positioned orthogonal to the ligand plane of palladium which also avoids unfavorable steric interactions.47 An alternative transition state structure (ix) that also involves an intramolecular delivery of the palladium moiety suffers from severe 1,3-diaxal steric strain between the iso-butyl and allylic methyl group. This transition state structure would lead to the formation of (S)-(Z)-20, which is not observed. Thus, the isobutyl group played a key role in facilitating the interpretation of the transmetalation step.

Scheme 7a.

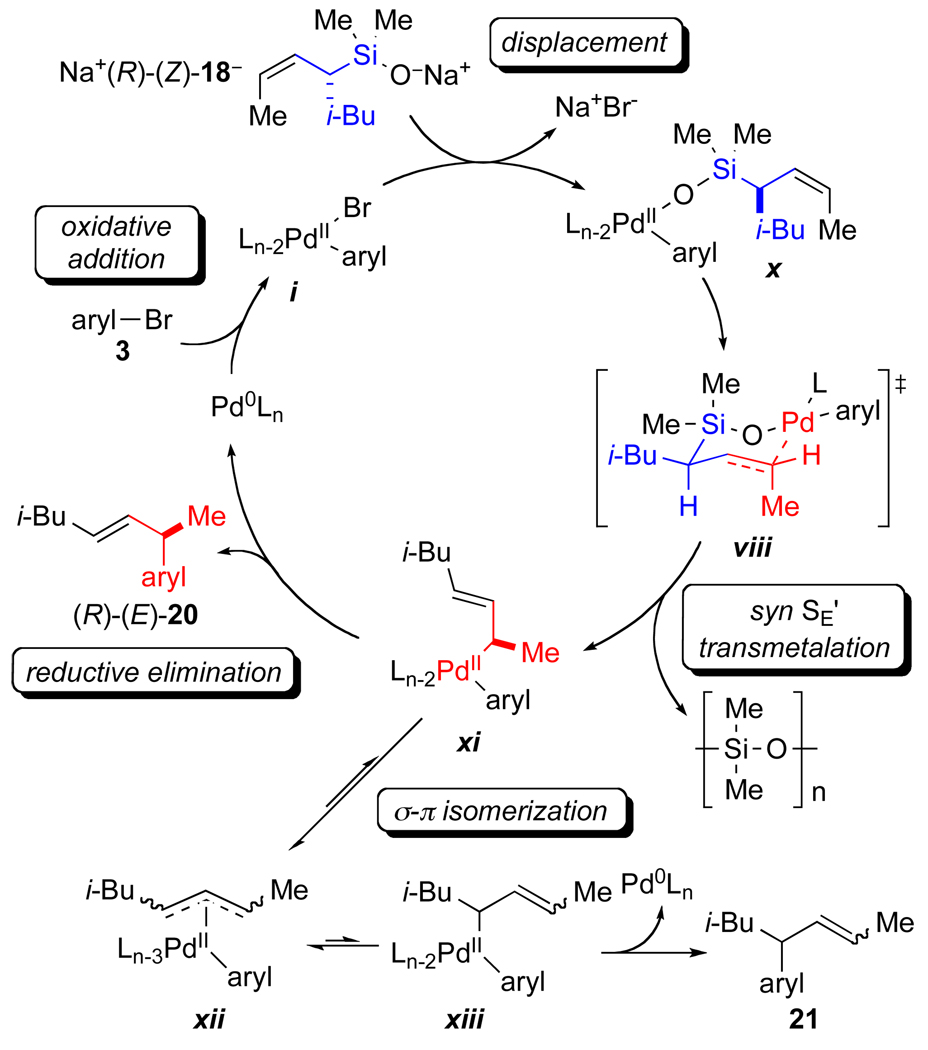

A refined catalytic cycle can now be constructed for the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of allylic silanolate salts with aromatic bromides (Figure 5). The cycle begins with oxidative addition of the aromatic bromide onto a palladium(0) complex. Displacement of bromide by the allylic silanolate Na+(R)-(Z)-18− forms the palladium(II) silanolate x. Transmetalation through a syn SE’ process forges a bond between the γ-carbon of Na+(R)-(Z)-18− and palladium via transition structure viii. Facile reductive elimination of the σ-bound palladium species xi facilitated by the π-acidic olefin ligand preempts σ-π isomerization and produces the γ-coupled product (R)-(E)-20 with excellent enantio-and geometrical specificity, and regenerates the palladium(0) catalyst.

Figure 5.

Refined catalytic cycle.

Conclusion

An enantioenriched, α-substituted, allylic silanolate salt undergoes palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling with aromatic bromides with excellent stereospecificity. The transmetalation event proceeds through a syn SE’ mechanism in which the stereogenic center in the educt controls the configuration of the newly formed stereogenic center in the product. These studies allow the construction of a detailed model of the stereodetermining step of the coupling of allylic silanolate salts. In addition, the high enantioinduction of all aromatic bromides surveyed implies that this pathway is general for many substrate types. The combination of the crucial Si–O–Pd linkage and the intimate connectivity between the palladium moiety and the stereodetermining transmetalation event bodes well for the development of catalytic, enantioselective cross-coupling reactions. The results from these studies will be disclosed in due course.

General Experimental

Preparation of (R)-((E)-1,5-Dimethyl-2-hexenyl)benzene ((R)-(E)-20a) from Bromobenzene Using Na+(R)-18−

To a 50-mL, single-necked, round-bottomed flask containing a magnetic stir bar and equipped with a three-way argon inlet capped with a septum, was added APC (3.7 mg, 0.010 mmol, 0.0050 equiv) and dba(4,4’-CF3) 22 (148 mg, 0.40 mmol, 0.20 equiv). The flask was then sequentially evacuated and filled with argon three times. Bromobenzene (314 mg, 2.0 mmol) was then added by syringe. The α-substituted allylic silanolate Na+(R)-18− (625 mg, 3.0 mmol, 1.5 equiv), pre-weighed into a 10-mL two-necked, round-bottomed flask in a dry box, was then dissolved in toluene (4.0 mL) and added by syringe. The reaction mixture was heated in a preheated oil bath to 70 °C with stirring under argon. After 24 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through silica gel (2 cm × 1 cm) in a glass-fritted funnel (coarse, 2 cm × 5 cm), and the filter cake washed with ether (3 × 15 mL). The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (30 mm × 20 cm, hexane), C-18 reverse phase chromatography (25 mm × 16 cm, MeOH/H2O, 9:1→20:1), and Kugelrohr distillation (70 °C, 0.7 mm Hg, ABT) to afford 288 mg (76%) of (R)-(E)-20a as a clear, colorless oil. Data for (R)-(E)-20a: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.35–7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.27–7.20 (m, 3 H), 5.62 (ddt, J = 15.3, 6.7, 1.2, 1 H), 5.48 (dtd, J = 15.3, 7.1, 1.2, 1 H), 3.47 (ap, J = 7.0, 1 H), 1.96–1.93 (m, 2 H), 1.69–1.61 (m, 1 H), 1.38 (d, J = 7.0, 3 H), 0.92 (d, J = 3.5, 3 H), 0.91 (d, J = 3.5, 3 H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) 146.5, 136.1, 128.3, 128.0, 127.2, 125.9, 42.3, 41.9, 28.5, 22.33, 22.27, 21.6; IR (film) 3027, 2959, 2927, 2870, 1602, 1492, 1452, 1384, 1367, 1017, 971, 758, 698, 537; MS (EI, 70 eV) 188, 145, 131, 118, 105, 91, 77; Rf 0.72 (hexane); Anal. Calcd for C14H20: C, 89.29; H, 10.71, Found: C, 89.06; H, 10.75.

Preparation of (S)-β-Methyl-benzeneethanol ((S)-23a) from (R)-((E)-1,5-Dimethyl-2-hexenyl)benzene

To a 25-mL, single-necked, round-bottomed flask containing a magnetic stir bar, equipped with a three-way adapter and gas dispersion tube was combined (R)-((E)-1,5-dimethyl-2-hexenyl)benzene (161 mg, 0.857 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (17 mL). The solution was then cooled to −78 °C under nitrogen. Ozone (scrubbed with 2-propanol/dry ice) was then bubbled through the solution until it turned blue (approx. 2 min). Nitrogen was then bubbled through the solution until colorless. While still at −78 °C, a freshly prepared solution of sodium borohydride (324 mg, 8.57 mmol, 10 equiv) in ethanol (17 mL) was added dropwise by syringe. The contents were then allowed to warm to rt with stirring and without removal of the cooling bath. After 18 h, the mixture was diluted with ether (25 mL) and 0.2 M HCl (50 mL) was added slowly by pipette. The biphasic mixture was then stirred for 1 h. The aqueous phase was separated in a 250-mL separatory funnel and was extracted with ether (2 × 25 mL). The three separate organic extracts were sequentially washed with H2O (2 × 25 mL) and brine (25 mL), then were combined, dried over MgSO4 until flocculent, and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue purified by silica gel chromatography (20 mm × 20 cm, pentane/EtOAc, 4:1→1:1 pentane/ EtOAc) followed by Kugelrohr distillation (90 °C, 1.5 mm Hg, ABT) to afford 77 mg (66%) of (S)-23a as a clear, colorless oil. Data for (S)-23a:36 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.37–7.34 (m, 2 H), 7.27–7.25 (m, 3 H), 3.7 (d, J = 6.8, 2 H), 2.96 (sextet, J = 7.0, 1 H), 1.62 (br, 1 H), 1.30 (d, J = 7.0, 3 H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) 143.7, 128.6, 127.4, 126.6, 68.6, 42.4, 17.5; IR (film) 3356, 3084, 3062, 3028, 2962, 2930, 2875, 1602, 1494, 1452, 1384, 1193, 1092, 1068, 1034, 1014, 911, 761, 700, 606; MS (EI, 70 eV) 136, 105, 91, 80; HRMS: Calcd for C9H12O: 136.0888, Found: 136.0887; ; Rf 0.21 (hexanes/EtOAc, 4:1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health for generous financial support (R01 GM63167) and Johnson-Matthey for the gift of Pd2(dba)3. N.S.W. thanks the Aldrich Chemical Co. for a Graduate Student Innovation Award and Eli Lilly and Co. for a Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures, full characterization of all products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Second Ed. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004. [Google Scholar]; (b) Negishi E-I, editor. Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. New York: Wiley–Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ojima I, editor. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Second Ed. New York: Wiley–VCH; 2000. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tietze LF, Ila H, Bell HP. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3453–3516. doi: 10.1021/cr030700x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayashi TJ. Organomet. Chem. 2002;653:41–45. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hayashi T. Chapt. 25. In: Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Vol. II. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]; (e) Blystone SL. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1663–1679. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The trivial case of cross-coupling of chiral subunits where the newly formed carbon–carbon bond is not a stereogenic unit are excluded.

- 4.By far the largest category of transition metal-catalyzed, carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond forming reactions involves the asymmetric capture of π-allyl-metals derived from palladium, molybdenum, rhodium and iridium with a wide range of nucleophiles. These powerful reactions have been thoroughly reviewed and therefore will not be categorized here, see: Lu Z, Ma S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:258–297. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. Trost BM, Crawley ML. Chem. Rev. 2003:2921–2943. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w. Pfaltz A, Lautens M. Chapt. 24. In: Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Vol. II. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1999.

- 5.For a definition of internal and external selection see: Denmark SE, Almstead NG. Allylation of Carbonyls: Methodology and Stereochemistry. In: Otera J, editor. Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley–VCH; 2000. pp. 299–402.

- 6.(a) Hatanaka Y, Goda K-I, Hiyama T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1279–1282. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiyama T, Matsuhashi H, Fujita A, Tanaka M, Hirabayashi K, Shimizu M, Mori A. Organometallics. 1996;15:5762–5765. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kalkofen R, Hoppe D. Synlett. 2006:1959–1961. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi S, Hirano K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12650–12651. doi: 10.1021/ja0755111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recently developed, transition metal-catalyzed additions of organic groups to aldehydes and imines are also not considered to be cross-coupling reactions. See: Skukas E, Ngai M-Y, Komanduri V, Krische MJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1394–1401. doi: 10.1021/ar7001123. Patman RL, Bower JF, Kim IS, Krische MJ. Aldrichimica Acta. 2008;41:95–104.

- 9.(a) Bringmann G, Mortimer AJP, Keller PA, Gresser MJ, Garner J, Breuning M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5384–5427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bringmann G, Walter R, Wirich R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1990;29:977–991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Glorius F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8347–8349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2656–2670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Shibasaki M, Vogl EM, Ohshima T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1533–1552. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bräse S, de Meijere A. Chapt. 5. In: de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Vol. 2. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dounay AB, Overman LE. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2945–2963. doi: 10.1021/cr020039h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Yamamoto Y, Takada S, Miyaura N. Chem. Lett. 2006;35:704–705. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamamoto Y, Takada S, Miyaura N. Chem. Lett. 2006;35:1368–1369. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamamoto Y, Takada S, Miyaura N, Iyama T, Tachikawa H. Organometallics. 2009;28:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martîn R, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4561–4564. doi: 10.1021/ol8017775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Culkin DA, Hartwig JF. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:234–245. doi: 10.1021/ar0201106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Kozlowski MC, Morgan BJ, Linton EC. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3193–3207. doi: 10.1039/b821092f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ogasawara M, Watanabe S. Synthesis. 2009:1761–1785. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bolm C, Hildebrand JP, Muñiz K, Hermanns N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:3284–3308. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3284::aid-anie3284>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itzumi Y, Tai A. Stereo-Differentiating Reactions: The Nature of Asymmetric Reactions. New York: Academic Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denmark SE, Werner NS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16382–16393. doi: 10.1021/ja805951j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiral, olefinic ligands are widely employed in asymmetric, transition metal-catalyzed reactions. However, their use in asymmetric palladium-catalyzed reactions remains elusive, see: Defieber C, Grützmacher H, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4482–4502. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703612.

- 18.Trauner reported the preparation of a chiral diene-ligated palladium-catalyst, however the use of this catalyst in a palladium-ene reaction provided only racemic products, see: Grundl MA, Kennedy-Smith JJ, Trauner D. Organometallics. 2005;24:2831–2833.

- 19.Kahn SD, Pau CF, Chamberlin AR, Hehre WJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:650–663. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Denmark SE, Almstead NG. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5130–5132. [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE, Hosoi S. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5133–5135. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming I, Au-Yeung B-W. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The term enantiospecificity [e.s. = (eeproduct / eestarting material) × 100%] provides a convenient method of describing the conservation of configurational purity for a reaction.

- 23.(a) Gallina C, Ciattini PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1035–1036. [Google Scholar]; (b) Goering HL, Kantner SS, Tseng CC. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:715–721. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smitrovich JH, Woerpel KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12998–12999. [Google Scholar]; (d) Smitrovich JH, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:1601–1614. doi: 10.1021/jo991312r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan Z, Negishi E-I. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2783–2785. doi: 10.1021/ol060856u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess K, Jennings LD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6129–6139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Speier JL, Webster JA, Barnes GH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:974–979. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chandra G, Lo PY, Hitchcock PB, Lappert MF. Organometallics. 1987;6:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denmark SE, Baird JD. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3120–3129. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woerpel has established the stereochemical outcome of the copper-catalyzed SN2’ reaction of Grignard reagents with allylic carbamates, see ref. 23d. However, the stereochemical identity and purity of the α-substituted allylic silanol was too important to be assumed from analogous precedent.

- 29.(a) Corey EJ, Mock WL, Pasto DJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1961;11:347–352. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hünig S, Müller HR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1962;1:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Fleming I, Henning R, Plaut H. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984:29–31. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tamao K, Ishida N, Tanaka T, Kumada M. Organometallics. 1983;2:1694–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho BT, Kim DJ. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:2457–2462. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(S)-2-Methylheptan-4-ol: Takenaka M, Takikawa H, Mori K. Liebigs Ann. 1996:1963–1964.

- 33.Racemic Na+18− was used for cross-coupling optimization and was synthesized by a similar route using racemic 13

- 34.The crotylation of bromobenzene with sodium 2-butenyldimethylsilanolate under these conditions provides high γ-selectivity (26:1) as determined by GC/MS analysis of the crude reaction mixture, see ref. 15

- 35.(a) Fairlamb IJS, Kapdi AR, Lee AF. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4435–4438. doi: 10.1021/ol048413i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fairlamb IJS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3645–3656. doi: 10.1039/b811772a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyotsuka Y, Acharya HP, Katayama Y, Hyodo T, Kobayashi Y. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1719–1722. doi: 10.1021/ol800300x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menicagli R, Piccolo O, Lardicci L. Chimica e I’Industria. 1975;57:499–500. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebibi J, Pelinski L, Maciejewski L, Brocard J. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:6011–6020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spino C, Beaulieu C, Lafreniere J. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:7091–7097. doi: 10.1021/jo000810t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wipf P, Ribe S. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1713–1716. doi: 10.1021/ol005865w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Na+18− (1.5 equiv), 3a (1.0 equiv, 1.0 mmol), Pd(dba)2 (5 mol %), nbd (5 mol %), toluene, 70 °C, 69% yield (5.2:1 E-γ/α)

- 42.By analogy the absolute configuration of 23b, 20f, and 23h are assigned as S, R, and S respectively.

- 43.The fact that the enantiospecificity of this process is greater than 100% is most likely caused by a hidden kinetic resolution. The minor component in Na+(R)-(Z)-18− is actually Na+(S)-(E)-18− which arises from the copper-catalyzed SN’ reaction. The lesser kinetic competence of Na+(S)-(E)-18− has the secondary effect of removing the contribution of the minor enantiomer to the product mixture; see ref. 23c and d.

- 44.Denmark SE, Sweis RF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4876–4882. doi: 10.1021/ja0372356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denmark SE, Smith RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1243–1245. doi: 10.1021/ja907049y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denmark SE. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:2915–2927. doi: 10.1021/jo900032x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.In other closed, transition state structures of palladium-catalyzed allylations the vinylic methyl group positioned coplanar with the square plane of palladium ligands was suggested to be disfavored. See: Iwasaki M, Hayashi S, Hirano K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4463–4469. doi: 10.1021/ja067372d.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.