Nonfouling surfaces play a very important role for the development of biosensors,1 medical implants,2 and drug delivery vehicles.3 However, few materials and modification methods have been reported to improve the nonfouling properties of surfaces effectively and conveniently. Among these reported materials, zwitterionic polymers, with both positive and negative charges on the side chains, showed excellent nonfouling properties in our previous studies.4–7 Based on these studies, it was hypothesized that a nanometer-scale homogeneous mixture of balanced charge groups will present protein-resistant properties. Recently, this assumption has been proved on hydrogels via free radical polymerization,8 polymer thin films 9 via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP) and polymer thin films via self-assembly. 10, 11 The ratios of positively to negatively charged monomers need to be optimized to achieve 1:1 on surfaces for most of these cases.

Polyampholytes are the synthetic analogues of naturally occurring biological molecules such as proteins, and have been used in areas such as lithographic film,12 emulsion formulation,13 and drag reduction.14 Extensive studies have been done on the control of the cationic-anionic ratio on the polymer side chains. Salamone et al.15–17 reported the synthesis of polyampholytes with equimolar polyampholyte derived from cationic-anionic monomer pairs. Periffer et al.18 reported the synthesis of polyampholytes without self-neutralized charge from equimolar charged monomers in the presence of nonpolymerizable counterions. McCormick et al.19 showed a high alternating tendency of the charged monomers in the copolymerization of sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate and (2-acrylamido-2-methylpropyl)dimethylammonium chloride. Yang et al. 20 also reported that 1:1 copolymer was obtained via the ion-pair method.

When coming to the methods of surface modification, both “graft from” and “graft to” methods have been used. The former gives higher packing densities and well-controlled thicknesses, 5, 21–24 whereas the latter is more convenient for practical applications.25–28 3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl-L-alanine (DOPA) and its derivatives inspired from the adhesive proteins found in mussel has been successfully incorporated into various synthetic polymers as the “graft to” anchor groups.25 Our previous studies demonstrated that polybetain incorporated with a catechol group can be successfully grafted to a surface with nonfouling properties.26

In this work, two polyampholytes of equimolar charged monomers with two types of catecholic anchor groups were synthesized via ATRP and free radical polymerization of the ion-pair comonomer. Two resulting polyampholytes are nonfouling without the need to optimize their surface ratios as in the case of randomly mixed charge nonfouling materials. The molecular weight and polydispersity index (PDI) of the polyampholytes were determined by using an aqueous gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The film thickness of the polymers attached on surfaces was measured by an ellipsometer. Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) was used to monitor functional groups on the surface qualitatively. Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA) was employed to determine the surface composition quantitatively. The protein-resistant properties were determined by measuring protein adsorption from fibrinogen (Fg), lysozyme (Lyz), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) using a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor.

The ion-pair comonomer (METMA·MES) was firstly synthesized from [2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]trimethylammonium chloride and 2-sulfoethyl methacrylate using a similar method reported before,15 which is described in Supporting Information. Previous studies showed that polyampholytes prepared in solution without any nonpolymerizable ions (such as inorganic cations and anions) have a tendency to be alternating as a result of strong electrostatic attractive forces acting between two opposite charged monomers.29 Therefore, after polymerization of the ion-pair monomers, equal amounts of the monomers can be incorporated in these high charge density copolymers.

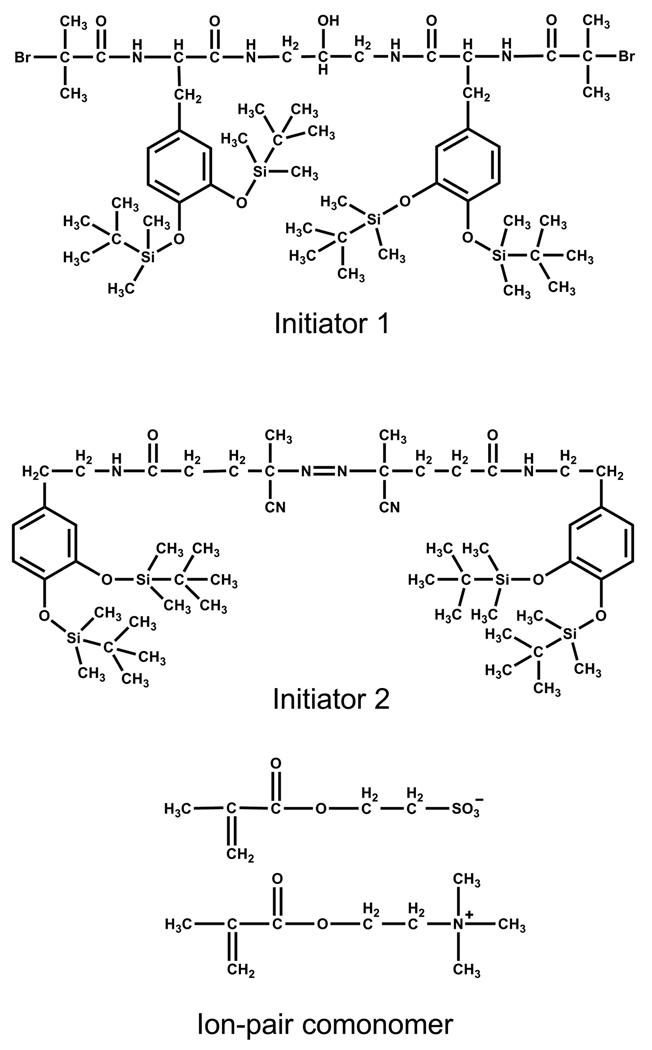

Two initiators (initiator 1 and initiator 2) with protected catecholic anchor groups were designed and synthesized as described in Supporting Information (scheme S1 and experimental details). The chemical structures of initiator 1 and initiator 2 are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that initiator 1 can be used to initiate atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) while initiator 2 is a typical initiator for free radical polymerization. Both of them are incorporated with adhesive catechol groups for an anchor. It should be mentioned that the protection of catecholic oxygens by the tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) groups can avoid side reactions during the polymerization and keep the adhesive polyampholytes stable before using.30

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of initiator 1, initiator 2 and the ion-pair comonomer.

Therefore, polymer I (Mn 19143) was obtained by ATRP of METMA·MES from initiator 1, while polymer II (Mn 28276) came from the free radical polymerization of METMA·MES from initiator 2. The detailed conditions of polymerization and the characterization of the polymers by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) are described in Supporting Information. Due to the different structures of initiator 1 and initiator 2, the adhesive groups will be located at different positions on the polymer chains. For polymer I, the two catechol groups are in the middle of the chain. For polymer II, the catecholic adhesive groups are located at the end(s) of the polymer chain. For free radical polymerization, two common types of termination reactions are combination and disproportionation. Since the free radicals at the both ends of the growing poly(METMA·MES) chain are sterically hindered due to the presence of methyl groups, termination reaction by combination is impeded (catechol groups are at both ends), and termination reaction by disproportionation predominates (cathechol groups are only at one end). Therefore, the main product from this work may be the polymer with one catechol group at one end of the chain. Both of these polyampholytes were deprotected by tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF), a mild de-protecting reagent, to remove the TBDMS groups before their usage for surface modification. A THF-water system was employed when the adhesive polymers were anchored to gold used as a model surface which is described further in Supporting Information.

The film thickness of the modified surfaces was measured by an ellipsometer. Results were summarized in Table 1. Messersmith et al.28 reported a 3–4 nm film of DOPA-PEG polymer adhered onto a titanium oxide surface. Herein more than 5 nm film of the polymers grafted onto gold gives a good evidence that both polyampholytes adhere well on the surfaces. In addition, the thicker film of polymer II than that of polymer I can be explained by the fact that the molecular weight of polymer II is higher than that of polymer I. The modified surfaces were also characterized by ATR-FTIR. Figure S1 shows the typical ATR-FTIR spectra of the surfaces modified by polymer I and polymer II. The strong absorbent peaks at 1039 cm−1, 1180 cm−1 and 1729 cm−1 correspond to SO3, C–O, and C=O stretches, which is consistent with our previous studies.22 Furthermore, ESCA was employed to determine their surface composition quantitatively. The ratio of the atomic percentage of nitrogen and sulfur was used to quantify the ratio of METMA and MES on the polymer chains. These ratios are summarized in Table 1. It can be seen from Table 1 that the calculated N/S ratios of polymer I and polymer II on the surfaces are 1.00 and 0.96, respectively. Then, it can be concluded that the statistical METMA/MES ratios of polymer I and polymer II are both 1:1, which is consistent with the studies of Salamone et al.15 Therefore, two homogeneous mixed polyampholytes with exact overall charge neutrality have been obtained. Representative ESCA spectra can be found in Supporting Information (Figure S2 and Figure S3).

Table 1.

Surface Characterizations (Average ± SD)

| Surfaces modified by | Polymer I | Polymer II |

|---|---|---|

| N/S ratio by ESCA (n=4) | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

| Film thickness by ellipsometer (nm) (n=10) | 5.75 ± 2.20 | 6.94 ± 1.88 |

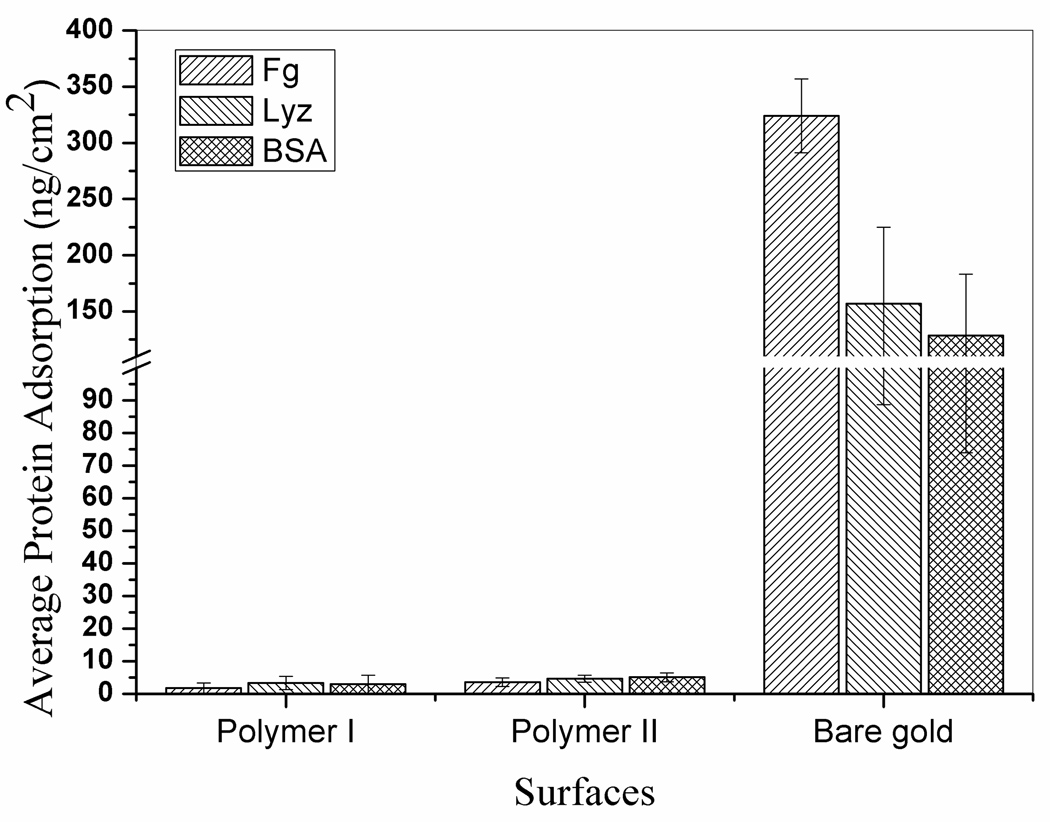

The protein-resistant properties of the modified surfaces were tested by a SPR sensor,31 which is ideal for measuring quantitative protein adsorption on a surface. Fibrinogen (Fg), lysozyme (Lyz), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were selected as test proteins. Fg is a soft and negatively charged protein, which can easily adsorb onto a wide range of materials. Lyz is a hard and positively charged protein while albumin is natural abundant in the body. The adsorption of Fg, Lyz, and BSA was measured simultaneously in a four-channel SPR. Typical SPR sensorgrams can be found in Supporting Information (Figures S4, S5 and S6). The summarized results are showed in Figure 2. The measured amounts of adsorbed Fg, Lyz, and BSA are 1.7±1.6, 3.3±2.0, 2.9±2.8 ng/cm2 for polymer I, and 3.5±1.3, 4.6±1.1, 5.0±1.4 ng/cm2 for polymer II, respectively. Thus, both surfaces modified by polymer I and polymer II show very good nonfouling properties. The nonfouling behaviors of the coated surfaces can be explained by the strong hydration layer on the surface coming from the neutral charged and the nearly perfect alternating METMA and MES on the side chains of the polymers.32 In addition, it should be mentioned that polymer II modified surfaces gave slightly higher nonspecific protein adsorption than that of polymer I. That can be attributed to the polymer structures discussed before. The main composition of polymer II results from termination reaction by disproportionation, which has only one catechol group at the end of the polymer chain. In comparison to polymer II, polymer I has two catechol groups for stronger binding 28 and two nonfouling chains for higher chain packing density, leading to denser adlayers and lower protein adsorption. Chen et al.33 reported the doubled density of the two-chain grafting from the surface as compared to the one-chain grafting. In addition, even there exists a small amount of polymer II with two catechol groups resulting from termination by combination, their binding onto an Au surface is not expected to be strong to hold both anchors at the far ends of a polymer chain. If only one end is attached, then unbounded catecholic groups at the other end will lead to some nonspecific protein adsorption.

Figure 2.

Adsorption of Fg, Lyz, and BSA to the surfaces modified by polymer I and polymer II in comparison to a bare gold surface. Error bar represents the standard derivations of the mean (n≥4).

In summary, two adhesive polyampholytes were synthesized by the polymerization of an ion-pair comonomer using two types of catecholic initiators. ESCA results show the N/S ratios of 1 and 0.96 for the gold surfaces modified by polymer I and polymer II, respectively. These neutral charged surfaces give excellent nonfouling properties from protein solutions of Fg, Lyz and BSA. This strategy to prepare ion-pair nonfouling polymers is convenient for surface attachment without adjusting the ratio of charged monomers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Office of Naval Research (N000140711036). Guozhu Li acknowledges a fellowship from the China Scholarship Council. The XPS experiments were performed at the National ESCA and Surface Analysis Center for Biomedical Problems (NESAC/BIO) supported by NIBIB Grant EB02027.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, typical ATR-FTIR spectra and ESCA survey scans of the modified surfaces, and typical SPR sensorgrams of protein adsorption on these surfaces are provided. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References and Notes

- 1.Prime KL, Whitesides GM. Science. 1991;252(5009):1164–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratner BD, Bryant SJ. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2004;6:41–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer R. Science. 2001;293(5527):58–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1063273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S, Zheng J, Li L, Jiang S. Journal of American Chemical Society. 2005;127:14473–14478. doi: 10.1021/ja054169u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladd J, Zhang Z, Chen S, Hower JC, Jiang S. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(5):1357–1361. doi: 10.1021/bm701301s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Chao T, Chen S, Jiang S. Langmuir. 2006;22:10072–10077. doi: 10.1021/la062175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Chen S, Jiang S. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(12):3311–3315. doi: 10.1021/bm060750m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SF, Jiang SY. Advanced Materials. 2008;20(2):335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernards MT, Cheng G, Zhang Z, Chen S, Jiang S. Macromolecules. 2008;41(12):4216–4219. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SF, Yu FC, Yu QM, He Y, Jiang SY. Langmuir. 2006;22(19):8186–8191. doi: 10.1021/la061012m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S, Cao Z, Jiang S. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5892–5896. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foss RP. Acrylic amphoteric polymers. 4749762. U. S. Patent. 1988

- 13.Farwaha R, Currie W. Amphoteric surfactants and copolymerizable amphorteric surfactants for use in latex paint. 5240982. U.S. Patent. 1993

- 14.Mumick PS, Welch PM, Salazar LC, McCormick CL. Macromolecules. 1994;27(2):323–331. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salamone JC, Quach L, Watterson AC, Krauser S, Mahmud MU. Journal of Macromolecular Science-Chemistry. 1985;A22(5–7):653–664. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salamone JC, Mahmud NA, Mahmud MU, Nagabhushanam T, Watterson AC. Polymer. 1982;23(6):843–848. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salamone JC, Watterson AC, Hsu TD, Tsai CC, Mahmud MU. Journal of Polymer Science Part C-Polymer Letters. 1977;15(8):487–491. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiffer DG, Lundberg RD. Polymer. 1985;26(7):1058–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormick CL, Johnson CB. Macromolecules. 1988;21(3):686–693. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang JH, Jhon MS. Journal of Polymer Science Part a-Polymer Chemistry. 1995;33(15):2613–2621. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma HW, Hyun JH, Stiller P, Chilkoti A. Advanced Materials. 2004;16(4):338–341. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li GZ, Xue H, Cheng G, Chen SF, Zhang FB, Jiang SY. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2008;112(48):15269–15274. doi: 10.1021/jp8058728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang W, Chen S, Cheng G, Vaisocherová H, Xue H, Keefe A, Li W, Zhang J, Jiang S. Langmuir. 2008 doi: 10.1021/la801487f. accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azzaroni O, Brown AA, Huck WTS. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006;45:1770–1774. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalsin JL, Hu B-H, Lee BP, Messersmith PB. Journal of American Chemical Society. 2003;125:4253–4258. doi: 10.1021/ja0284963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li GZ, Cheng G, Xue H, Chen SF, Zhang FB, Jiang SY. Biomaterials. 2008;29(35):4592–4597. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statz AR, Meagher RJ, Barron AE, Messersmith PB. Journal of American Chemical Society. 2005;127:7972–7973. doi: 10.1021/ja0522534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalsin JL, Lin LJ, Tosatti S, Voros J, Textor M, Messersmith PB. Langmuir. 2005;21(2):640–646. doi: 10.1021/la048626g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kudaibergenov SE. polyampholytes: synthesis, characterization, and application. Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sever MJ, Wilker JJ. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(29):6139–6146. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Homola J. Chemical Reviews. 2008;108(2):462–493. doi: 10.1021/cr068107d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He Y, Hower J, Chen SF, Bernards MT, Chang Y, Jiang SY. Langmuir. 2008;24(18):10358–10364. doi: 10.1021/la8013046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen RX, Feng C, Zhu SP, Botton G, Ong B, Wu YL. Journal of Polymer Science Part a-Polymer Chemistry. 2006;44(3):1252–1262. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.