Abstract

Caspr and Caspr2 regulate the formation of distinct axonal domains around the nodes of Ranvier. Caspr is required for the generation of a membrane barrier at the paranodal junction (PNJ), whereas Caspr2 serves as a membrane scaffold that clusters Kv1 channels at the juxtaparanodal region (JXP). Both Caspr and Caspr2 interact with protein 4.1B, which may link the paranodal and juxtaparanodal adhesion complexes to the axonal cytoskeleton. To determine the role of protein 4.1B in the function of Caspr proteins, we examined the ability of transgenic Caspr and Caspr2 mutants lacking their 4.1-binding sequence (d4.1) to restore Kv1 channel clustering in Caspr- and Caspr2-null mice, respectively. We found that Caspr-d4.1 was localized to the PNJ and is able to recruit the paranodal adhesion complex components contactin and NF155 to this site. Nevertheless, in axons expressing Caspr-d4.1, Kv1 channels were often detected at paranodes, suggesting that the interaction of Caspr with protein 4.1B is necessary for the generation of an efficient membrane barrier at the PNJ. We also found that the Caspr2-d4.1 transgene did not accumulate at the JXP, even though it was targeted to the axon, demonstrating that the interaction with protein 4.1B is required for the accumulation of Caspr2 and Kv1 channels at the juxtaparanodal axonal membrane. In accordance, we show that Caspr2 and Kv1 channels are not clustered at the JXP in 4.1B-null mice. Our results thus underscore the functional importance of protein 4.1B in the organization of peripheral myelinated axons.

Introduction

The segregation of ion channels to distinct membrane domains at and around the nodes of Ranvier is essential for fast and efficient nerve conduction in myelinated axons. In each of these domains, ion channels are found in protein complexes that include cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), adapter proteins, and cytoskeletal components (Poliak and Peles, 2003; Salzer, 2003; Hedstrom and Rasband, 2006). The nodes of Ranvier are bordered by the paranodal junctions (PNJs) that form between the axon and the paranodal loops of oligodendrocytes or myelinating Schwann cells. The formation and maintenance of the PNJ depends on the presence of an axonal CAM complex containing Caspr and contactin, as well as on the presence of the 155 kDa isoform of neurofascin (NF155) at the paranodal glial membrane (Bhat et al., 2001; Boyle et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2003; Sherman et al., 2005; Zonta et al., 2008; Pillai et al., 2009). The PNJ separates the nodal Na+ channels from Shaker-like Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 K+ channels at the juxtaparanodal region (JXP) found at the ends of the compact myelin internode. At this site, Kv1 channels are localized and associated with an axonal cell adhesion complex consisting of Caspr2 and TAG-1, which bind to TAG-1 present on the glial membrane (Poliak et al., 1999, 2003; Traka et al., 2002, 2003). Caspr and Caspr2 are both important for the accumulation of K+ channels at the JXP. Caspr is required for the formation of a membrane barrier at the PNJ; in its absence, Kv1 channels aberrantly accumulate adjacent to the nodes (Bhat et al., 2001; Boyle et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2003). In contrast, Caspr2 serves as a membrane scaffold that clusters Kv1 channels at the JXP. Accordingly, in Caspr2-null mice, these channels are distributed along the internodes (Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003).

The cytoplasmic region of Caspr and Caspr2 contains a short sequence that mediates their binding to 4.1 proteins (Menegoz et al., 1997; Peles et al., 1997; Poliak et al., 1999; Gollan et al., 2002; Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003). 4.1 proteins are cytoskeletal adapters that link adhesion molecules (Nunomura et al., 1997; Ward et al., 1998; Biederer and Sudhof, 2001; Zhou et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2009), ion channels (Coleman et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007; Stagg et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2009), and receptors (Binda et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2004; Beekman et al., 2008; Rose et al., 2008) to the actin/spectrin cytoskeleton, thereby playing an important role in membrane organization (Bennett and Baines, 2001). Of the four members of the protein 4.1 family (i.e., 4.1R, 4.1N, 4.1G, and 4.1B), protein 4.1B is expressed in myelinated axons, where it is located along the internodes, PNJ, and the JXP region (Ohara et al., 2000; Poliak et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2002; Arroyo et al., 2004; Ogawa et al., 2006). We previously suggested that the association between Caspr and protein 4.1B stabilizes Caspr at the plasma membrane by linking the PNJ adhesion complex to the actin-rich cytoskeleton found at this site (Gollan et al., 2002). Interestingly, Neurexin IV, the fly homolog of Caspr and Caspr2 (Baumgartner et al., 1996), as well as Coracle, the fly orthologue of protein 4.1, are both necessary for the generation of septate junctions (Baumgartner et al., 1996; Ward et al., 1998), suggesting that the function of Caspr and Caspr2 in the organization of myelinated axons may require protein 4.1B. In the present work, we use an in vivo transgenic rescue and gene knock-out approaches to elucidate the role 4.1 proteins play in the organization of myelinated axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) by Caspr and Caspr2.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice.

Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged constructs were generated by PCR using human Caspr and Caspr2 cDNAs: Caspr full-length (C1FL), Casprd4.1 (C1d4.1; deletion of amino acids Q1307 to Y1315), Caspr2 full-length (C2FL), and Caspr2d4.1 (deletion of amino acids R1298 to H1304). In Caspr constructs, the HA tag (amino acids YPYDVPDYAS) was inserted at the C terminus at position E1384 for C1FL and after E1375 for C1d4.1. In Caspr2 constructs, the same sequence was inserted at the extracellular region adjacent to the transmembrane domain between positions N1255 and G1256. For expression and analysis in mammalian cultured cells, these constructs were cloned into the expression vector pCi-neo (Promega). Generation of a myc-tagged protein 4.1B has been previously described (Gollan et al., 2002). For pull-down experiments, the cytoplasmic tails of Caspr and Caspr2 (full lengths and the respective 4.1 deletions) were cloned into pGEX-6P1 (GE Healthcare). For generation of transgenic mice, Caspr and Caspr2 constructed genes were cloned into a Thy1.2 expression cassette (Gollan et al., 2002; Horresh et al., 2008), linearized, and introduced by pronuclear injection into fertilized eggs derived from CB6F1 mice. Pseudopregnant CD-1 albino females were used as foster mothers for embryo transfer. Founder mice were genotyped for the presence of the transgenes by PCR using primers 5′-CTGCTGAGCTAGCTGAGGC-3′ and 5′-TCACGATGCGTAGTCAGGC-3′, and for Caspr2 transgenes, using primers 5′-GCGTAGTCAGGCACATCGTATGGG-3′ and 5′-ATACCACGGTTACTCCTGCGATTGC-3′. Founders were further crossed with CB6F1 mice and interbred to generate lines. Transgenic mice were routinely identified by PCR of tail genomic DNA, using the appropriate primers derived from human Caspr or Caspr2 and HA tag. The same primers were also used for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analyses of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) RNA isolated from the transgenic mice. Based on immunoprecipitation performed from brains of transgenic mice, two lines from each genotype were chosen to be further crossed with Caspr-null or Caspr2-null mice (Gollan et al., 2003; Poliak et al., 2003) until homozygote-null mice for the endogenous Caspr or Caspr2 and positive for the relevant transgene were obtained. Generation and genotyping of 4.1B-null mice have been described previously (Yi et al., 2005). Wild-type control animals were derived from the same litters. All experiments were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by The Weizmann Institute's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

DRGs were removed from WT, transgenic mice and 4.1B-null mice and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), and cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCRs were done with the following primers: 4.1B, 5′-AGACCAGGAGGCTGAGCC-3′ and 5′-GCCGTACTCTGACCCATCCA-3′; 4.1G, 5′-AAGAAGGGCTCTGACCAGGC-3′ and 5′-CCACCTCTGCCTTCAGCTCA-3′; 4.1N, 5′-AAGGCTCAGGAGGAGACTCC-3′ and 5′-CGGCCGTGCTTCTCCACTT-3′; 4.1R, 5′-AAGAGTTTAGCGGCTGAAGC-3′ and 5′-CGGGCTTCTGGGAGGCTT-3′; Actin, 5′-TCATACCGGGCACACTTCAC-3′ and 5′-CATTTGGGAGGGTCTGTGGC-3′; Caspr, 5′-ATTGCGGAGCGCTGGGGAGAGG-3′ and 5′-GAGAGGGAAGGGTGGATAAGGAC-3′, and for the endogenous Caspr2 gene, 5′-TGCTGCTGCCAGCCCAGGAACTGG-3′ and 5′-TCAGAGTTGATACCCAGCGCC-3′.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

For pull-down experiments, HEK293 were transfected with cDNA encoding myc-tagged protein 4.1B by calcium phosphate. After 48 h, the cells were lysed using a buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100 (Tx100), supplemented with a protease inhibitors mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). Cleared lysates were allowed to bind glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins prebound to agarose-glutathione beads (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C. Complexes were then washed three times in a buffer containing 0.1% Tx100, separated on 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with anti-myc antibody. For comparison of protein levels, three pairs of sciatic nerves of each genotype were dissected, desheathed in cold PBS, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The nerves were then ground with a mortar and pestle, solubilized in 150 μl of buffer containing 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA, and 2% SDS, boiled for 15 min, and then spun for 20 min at 15°C. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce Chemical). Sample (50 μg) were loaded onto a 10% SDS gel followed by Western blot analysis (Poliak et al., 1999). Cell surface biotinylation of HEK293 transfected cells was performed as described previously (Gollan et al., 2002).

Antibodies and immunofluorescence.

A detailed list of the antibodies used in this study is provided in supplemental Table S1 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). A rat polyclonal antibody against NrCAM was generated by immunizing rats with an Fc fusion protein containing the six Ig and two of the fibronectin-like domains of mouse NrCAM. For the generation of anti-4.1N antibody, rabbits were immunized with a GST fusion peptide containing amino acids 1-321 of mouse protein 4.1N. A mouse polyclonal antibody to the extracellular domain of Caspr2 was made by immunizing BALB/c mice with Caspr2-Fc fusion protein (Poliak et al., 2003). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against TAG1 was generated by immunizing rabbits with an Fc fusion protein containing the fibronectin-like domains of rat TAG-1 (residues 610-1040). Immunofluorescence analysis of transfected cells and teased sciatic nerves was done as previously described (Horresh et al., 2008). Sciatic nerves were dissected and immersed in freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C, or for 10 min in Zamboni's fixative at ambient temperature. After desheathing, nerves were teased using fine forceps on Superfrost Plus slides, air dried for 2–3 h, and then kept frozen at −20°C until used. Slides were postfixed for 2–10 min using cold methanol, washed with PBS, incubated for 45 min in blocking solution (5% fish skin gelatin and 0.1% Triton X-100), and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the different primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. For staining with anti-NF155 antibody, nerves were postfixed for 1 min with Bouin's fixative (Sigma-Aldrich) instead of methanol. For protein 4.1B staining, slides were left in blocking solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 h at ambient temperature before adding the antibody. Slides were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h in blocking solution containing the secondary antibodies: anti-mouse-Cy3, anti-rat Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), or anti rabbit-Alexa 488 (Invitrogen). Triple immunolabeling was done using antibodies from three different species. Fluorescence images were obtained using an Axioskop 2 microscope equipped with Apotom imaging system (Carl Zeiss), or a Nikon Eclipse E1000 microscope fitted with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER CCD camera. Quantification of the paranodal size was performed using Volocity 4.2.1 image analysis software (Improvision). Mean paranodal area was calculated for each genotype (n = 600) and statistical significance was validated using a two-tailed Student t test. Quantification of Kv1.2 distribution was done by counting the number of sites in which it was present at the JXP, PNJ, or both sites, and presented as a percentage of the total number of nodal sites examined (n = 150).

Results

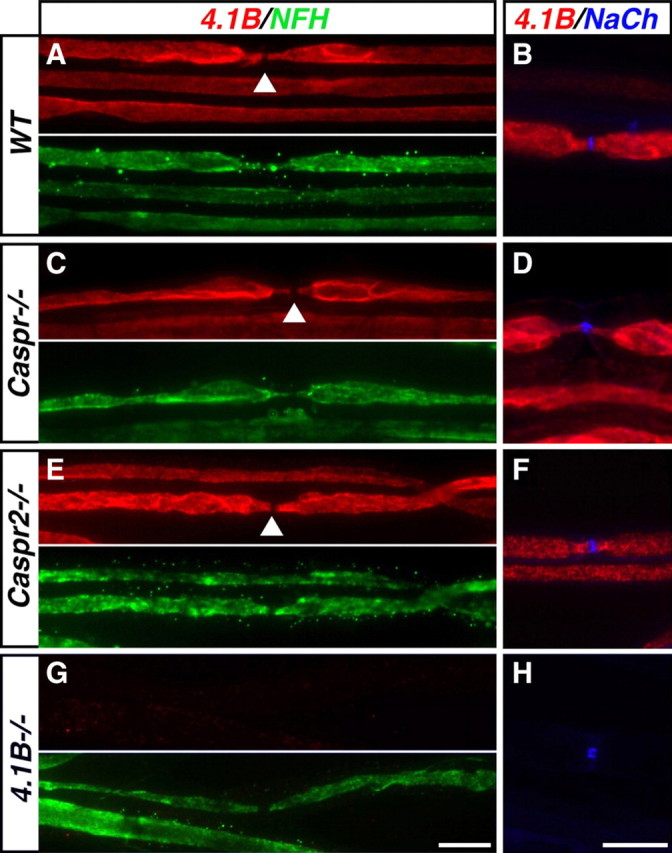

Distribution of protein 4.1B along myelinated axons does not require Caspr or Caspr2

In myelinated axons, protein 4.1B is located at the PNJ and JXP regions together with Caspr and Caspr2, respectively (Ohara et al., 2000; Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003; Ogawa et al., 2006). Furthermore, it has been previously suggested that the localization of protein 4.1B in these axons might be regulated by Caspr proteins (Poliak et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2002; Arroyo et al., 2004). To directly determine the role Caspr and Caspr2 play in the localization of protein 4.1B in myelinated axons, we compared the distribution of protein 4.1B in sciatic nerves of wild-type and Caspr- or Caspr2-null mice. In wild-type animals, protein 4.1B immunoreactivity was detected along the internodes and was often stronger at the PNJ and JXP (Fig. 1A,B). Notably, protein 4.1B immunoreactivity was highly specific as determined by labeling of teased sciatic nerves isolated from protein 4.1B-null mice (Yi et al., 2005) using the same antibody (Fig. 1G,H). Similar to wild-type nerves, in sciatic nerve fibers isolated from Caspr−/− or Caspr2−/− mice, protein 4.1B was absent from the nodes but detected at the PNJ, JXP, and the internodes (Fig. 1C–F). These results demonstrate that the localization of protein 4.1B in PNS myelinated axons occurs independently from Caspr or Caspr2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of protein 4.1B in myelinated axons is not affected in the absence of Caspr or Caspr2. Immunofluorescence labeling of teased adult sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type (WT) (A, B), Caspr-null (Caspr−/−) (C, D), Caspr2-null (Caspr2−/−) (E, F), or protein 4.1B-null (4.1B−/−) (G, H) mice, using antibodies to protein 4.1B and neurofilament H (NFH) or Na+ channels (NaCh) as indicated. Images of the individual green and red channels are shown in A, C, E, and G. The arrowheads indicate the location of the nodes. Protein 4.1B is found at the PNJ, JXP, and internodes in the presence or absence of Caspr or Caspr2. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Generation of transgenic mice expressing deletion mutants of Caspr and Caspr2 lacking their 4.1B-binding sequence

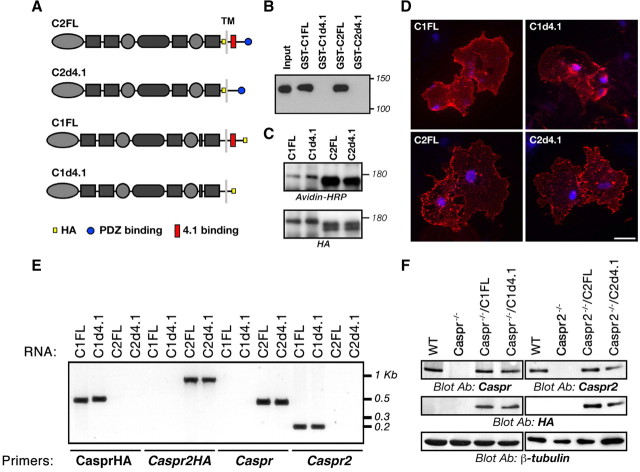

Caspr and Caspr2 interact with 4.1 proteins through a short sequence found in their cytoplasmic domain (Menegoz et al., 1997; Peles et al., 1997; Gollan et al., 2002; Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003). To determine whether this interaction is required for the function of Caspr proteins in the molecular organization of the axolemma, we have constructed deletion mutants of Caspr and Caspr2 lacking their 4.1-binding motif (C1d4.1 and C2d4.1) (Fig. 2A) and tested whether they could restore the clustering of Kv1 channels at the JXP when placed on the genetic background of Caspr- or Caspr2-null mice. As controls, we used full-length Caspr (C1FL) and Caspr2 (C2FL) cDNAs. All constructs also contained an HA tag (Fig. 2A). We next performed a pull-down experiment using GST fusion proteins containing the cytoplasmic domains of the four constructs from HEK293 cells expressing protein 4.1B. As shown in Figure 2B, protein 4.1B was associated with the cytoplasmic domains of the full length, but not with the mutant Caspr and Caspr2. Transfection of Caspr2 constructs, or Caspr constructs along with contactin cDNA into HEK293 cells revealed that all proteins were efficiently expressed on the cell surface, as was evident by cell surface biotinylation, followed by immunoprecipitation with an antibody to HA tag and blotting with streptavidin-HRP (Fig. 2C). Similarly, antibodies directed to the extracellular region of Caspr and Caspr2 recognized all the respective proteins in intact, nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 2D), further demonstrating that they were expressed on the cell surface.

Figure 2.

Characterization of Caspr and Caspr2 transgenes. A, Schematic representation of the different constructs used. The cytoplasmic domain of Caspr contains a 4.1-binding sequence (red square), whereas that of Caspr2 contains both 4.1 and PDZ (blue circle) domain binding sequences. C1FL and C2FL encode a full-length HA-tagged (yellow square) Caspr and Caspr2, respectively. The C1d4.1 and C2d4.1 constructs encode for Caspr and Caspr2 lacking their protein 4.1-binding region. B, Interaction with protein 4.1B. GST fusion proteins containing the cytoplasmic domain of Caspr (C1CT) or Caspr2 (C2CT), or cytoplasmic domains lacking their putative protein 4.1-binding sequence (C1d4.1 or C2d4.1) used to pull down myc-tagged protein 4.1B from lysates of 4.1B-transfected HEK293 cells. Protein complexes were subjected to immunoblot analysis using an antibody to myc tag. A sample of the cell lysate (Input) was used as control for protein 4.1B expression. The location of molecular mass markers is shown on the right in kilodaltons. C, D, Caspr2 transgenes reach the cell surface. C, Cell surface biotinylation was performed using HEK293 cells expressing Caspr and Caspr2 transgenes. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an antibody to HA tag followed by immunoblotting with the same antibody (bottom panel) or with streptavidin-HRP (top panel). The location of molecular mass markers is shown on the right in kilodaltons. D, Nonpermeabilized COS-7 cells expressing Caspr transgenes and contactin, or Caspr2 transgenes, were labeled with an antibody to the extracellular domain of Caspr (top panels) or Caspr2 (bottom panels). Cell nuclei are labeled with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (blue). Scale bar, 30 μm. E, Expression of the transgenic transcripts in peripheral sensory neurons. Dorsal root ganglion mRNA isolated from Caspr−/−/C1FL (C1FL), Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 (C1d4.1), Caspr2−/−/C2FL (C2FL), and Caspr2−/−/C2d4.1 (C2d4.1) transgenic mice were used as a template for RT-PCR using specific primer sets that recognize each of the endogenous genes (Caspr and Caspr2), or each of the transgenes (CasprHA and Caspr2HA). The location of size markers is shown on the right in kilobases. F, All transgenic proteins are targeted to the axon. Immunoblot analysis of sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type (WT), Caspr or Caspr2 nulls, or the four transgenic mice, using antibodies to Caspr, Caspr2, HA tag, or β-tubulin as indicated.

To express Caspr and Caspr2 transgenes in neurons, they were cloned downstream from a Thy1.2 promoter (Gollan et al., 2002; Horresh et al., 2008). Transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear injection and crossed with mice lacking either Caspr or Caspr2 to obtain Caspr−/−/C1FL, Caspr−/−/C1d4.1, Caspr2−/−/C2FL, and Caspr2−/−/C2d4.1 transgenic animals. RT-PCR analysis of dorsal root ganglia mRNA isolated from the four genotypes using specific primer sets that recognize each of the transgenes confirmed that they are expressed in sensory peripheral neurons (Fig. 2E). In contrast to wild-type mice, no expression of the endogenous Caspr and Caspr2 transcripts was detected in either Caspr or Caspr2 transgenic lines, further demonstrating that the transgenes were expressed on a null background. To examine the expression of the transgenes in peripheral nerves, we performed immunoblot analysis of sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type, Caspr or Caspr2 nulls, or the four transgenic mice lines using an HA tag antibody, as well as antibodies directed against the intracellular domain of the two Caspr proteins. As depicted in Figure 2F, all the respective transgenic proteins were detected in sciatic nerves isolated from the transgenes but not from the wild-type or the null mice. Thus, similarly to the full-length transgenes (i.e., C1FL and C2FL), Caspr and Caspr2 mutants lacking their protein 4.1-binding sequence (i.e., C1d4.1 and C2d4.1) are targeted to the axon in mice lacking their respective endogenous protein.

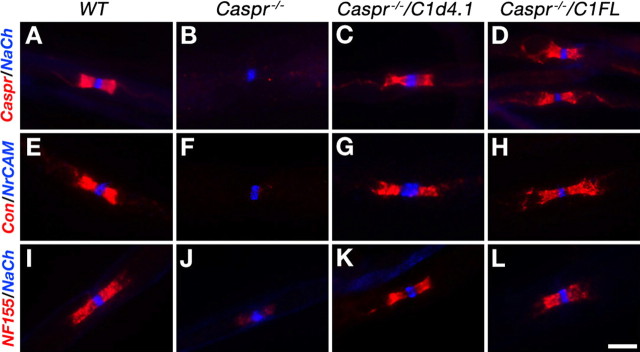

C1FL and C1d4.1 transgenes recruit contactin and NF155 to the PNJ

To determine whether the interaction between Caspr and 4.1 proteins is required for its targeting to the PNJ, we immunolabeled teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice, Caspr−/−, or Caspr nulls expressing the C1d4.1 (Caspr−/−/C1d4.1) or the FL (Caspr−/−/C1FL) transgenes, using antibodies to Caspr (Fig. 3A–D). Similarly to wild-type nerve, but in contrast to Caspr null, both C1FL and C1d4.1 were located at the PNJ in axons expressing these transgenes (∼70 and 45% of the axons expressed the C1FL and C1d4.1 transgenes, respectively). Nevertheless, although the average area of Caspr-positive paranodes in Caspr−/−/C1FL nerves was 23.4 ± 3 μm2 (n = 600), it only reached the size of 15.9 ± 2 μm2 (n = 600) in Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 mice, suggesting that stable expression of Caspr at the PNJ requires its binding to protein 4.1B (Gollan et al., 2002). Consistent with previous studies (Bhat et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2003), both contactin and NF155, which are part of the paranodal adhesion complex (Charles et al., 2002; Gollan et al., 2003; Bonnon et al., 2007), were not concentrated at the PNJ in Caspr-null mice (Fig. 3F,J). In contrast, both were present at the PNJ in sciatic nerves isolated from Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 and Caspr−/−/C1FL mice. These results demonstrate that the expression of either C1FL or the C1d4.1 transgene on the background of Caspr-null nerves resulted in the recovery of all paranodal adhesion components at the PNJ.

Figure 3.

Caspr transgenes are localized at the PNJ and rescued the paranodal adhesion complex. Double immunofluorescence labeling of teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice (WT), Caspr nulls (Caspr−/−), or Caspr nulls expressing the C1d4.1 (Caspr−/−/C1d4.1), or the FL (Caspr−/−/C1FL) transgenes, using antibodies to Caspr and Na+ channels (NaCh) (A–D), contactin (Con) and NrCAM (E–H), or NF155 and Na+ channels (I–L). Scale bar, 5 μm.

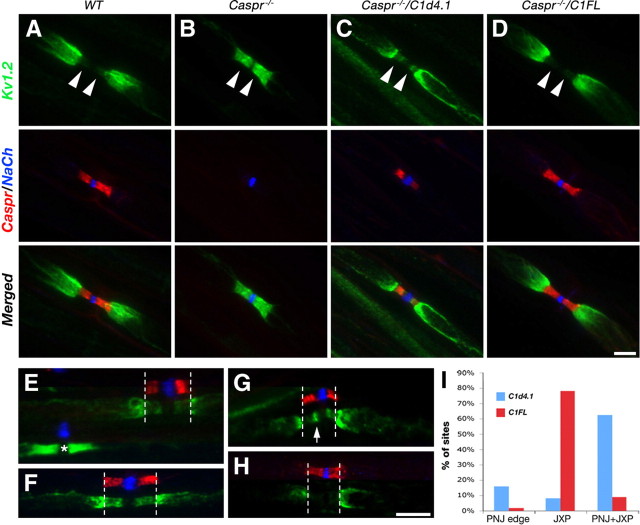

Kv1 channels are located at both the PNJ and JXP in axons expressing the C1d4.1 transgene

The presence of Caspr is required for the generation of a paranodal membrane barrier that separates Kv1 channels and other juxtaparanodal proteins from the nodal axolemma (Bhat et al., 2001; Pedraza et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2003; Rosenbluth, 2009). Accordingly, we proceeded to examine whether expression of the C1FL and C1d4.1 transgenes could rescue the membrane barrier function of the PNJ. In peripheral nerves of wild-type mice, Kv1.2 was clustered at the JXP, whereas in Caspr−/− nerves this K+ channel subunit accumulated at the paranodal region adjacent to the nodes of Ranvier (Fig. 4A,B). Immunofluorescence analysis of sciatic nerves isolated from the two transgenic mice showed that, whereas Kv1.2 was sequestered at the JXP in Caspr−/−/C1FL as in wild-type mice, in Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 nerves it was detected at the JXP and more weakly at the PNJ, where it partially overlapped with the C1d4.1 transgene (Fig. 4C,D). In general, the distribution of Kv1.2 in sciatic nerves of Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 was variable; it was either detected at both JXP and the PNJ (Fig. 4E,F), at the JXP and in a line bordering the nodes (Fig. 4G), or only at the JXP (Fig. 4H). Quantitation of the different cases is presented in Figure 4I. In addition to Kv1.2, similar results were obtained using antibodies to other juxtaparanodal proteins, including Caspr2 and TAG-1 (data not shown). These results indicate that, in contrast to the full-length protein, axonal expression of a Caspr mutant lacking its protein 4.1-binding sequence is not sufficient to completely restore the clustering of K+ channels at the JXP, and suggest that the interaction of Caspr with protein 4.1B is necessary for its proper accumulation at the PNJ and generation of an efficient membrane barrier at this site.

Figure 4.

Kv1 channels are not efficiently excluded from the PNJ in Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 mutant mice. Triple immunofluorescence labeling of teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice (WT) (A), Caspr nulls (Caspr−/−) (B), or Caspr nulls expressing the C1FL (Caspr−/−/FL) (C) or the C1d4.1 (Caspr−/−/C1d4.1) (D–H) transgenes, using antibodies to Caspr (red), Kv1.2 (green), and Na+ channels (NaCh; blue). The arrowheads in A–D mark the location of the PNJ. Staining for Caspr and NaCh was shifted in E–H to reveal Kv1.2 immunoreactivity. Note that, whereas the expression of the C1FL transgene resulted in complete exclusion of Kv1.2 to the JXP (D), these channels were present to various degrees at the PNJ in Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 axons (D–G). The asterisk in E marks a nodal site that does not express the transgene. An arrow in G points to the accumulation of Kv1.2 in a line between the nodes and the PNJ. I, Quantitation of Kv1.2 distribution in sciatic nerves of Caspr−/−/C1d4.1 or Caspr−/−/C1FL transgenes. Percentage of sites along sciatic nerves in which Kv1.2 channels are located at the juxtaparanodes (JXP), at both juxtaparanodes and paranodes (JXP+PNJ), or are concentrated at the edges of the PNJ (PNJ edge). Scale bars, 10 μm.

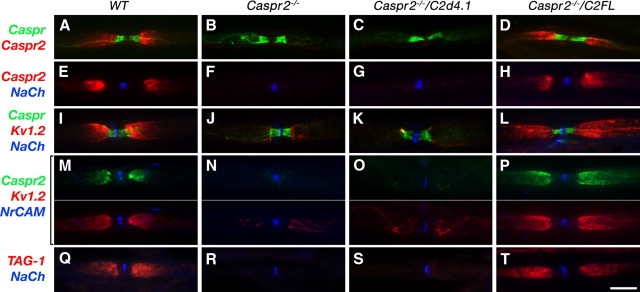

Protein 4.1B-binding domain in Caspr2 is required for its juxtaparanodal localization

We next examined the significance of the interaction between Caspr2 and 4.1 proteins for its function as a membrane scaffold that retains K+ channels at the JXP (Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003). To this end, we labeled teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type, Caspr2 nulls, or Caspr2 nulls expressing the C2FL or C2d4.1 transgenes, using antibodies to Caspr2 and either Caspr (to mark the PNJ) or to Na+ channels (to mark the location of the nodes) (Fig. 5A–H). In agreement with a recent report (Horresh et al., 2008), the C2FL transgene was localized at the JXP similar to the endogenous protein in the wild-type mice, whereas the Caspr2 mutant lacking its protein 4.1-binding sequence (C2d4.1) was absent from the JXP. The latter transgene was either undetectable, or only weakly detected along the axon. The expression of C2FL at the JXP resulted in a full rescue of Kv1.2 channels at this site (Fig. 5I–P). C2FL-positive JXP also contained the two other juxtaparanodal proteins, TAG-1 (Fig. 5T) and PSD93 (Horresh et al., 2008). In contrast, Kv1.2 and TAG-1 immunoreactivity was reduced to absent in the JXP of myelinated axons from C2d4.1 transgenic mice (Fig. 5K,O,S). Given that the C2d4.1 transcript was present in DRG neurons (Fig. 2E), and that the transgenic C2d4.1 protein was detected in sciatic nerves isolated from Caspr2−/−/C2d4.1 mice (Fig. 2F), these results indicate that the protein 4.1-binding sequence of Caspr2 is essential for its targeting to the JXP.

Figure 5.

Localization of Caspr2 at the JXP requires its protein 4.1-binding site. Immunofluorescence labeling of teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice (WT) (A, E, I, M), Caspr2 nulls (Caspr2−/−) (B, F, J, N), or Caspr2 nulls expressing the C2d4.1 (Caspr2−/−/C2d4.1) (C, G, K, O) or the C2FL (Caspr2−/−/C2FL) (D, H, L, P) transgenes, using different antibody combinations as indicated on the left. Merged images are shown in A–L and Q–T, whereas in M–P the red and green channels are shown in separate panels. In contrast to the C2FL transgene, C2d4.1, Kv1 channels, and TAG-1 are not clustered at the JXP. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Protein 4.1B is necessary for the clustering of K+ channels at the JXP

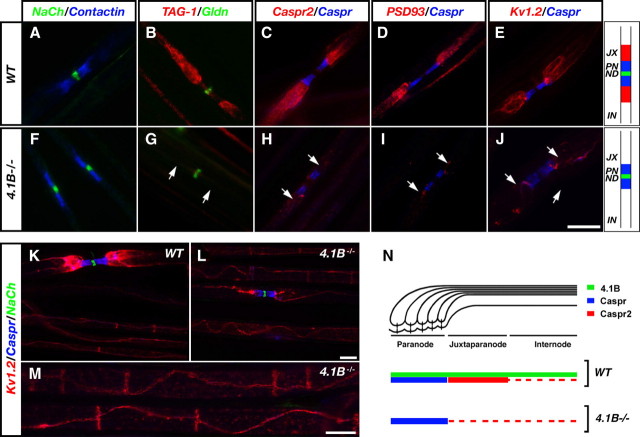

The above results indicate that the interaction between Caspr proteins and protein 4.1 is required for their function. To further determine the role of these cytoskeletal linkers in myelinated axons, we have examined the organization of the nodal environs of mice lacking protein 4.1B (Yi et al., 2005), a member of the 4.1 protein family that overlaps and associates with both Caspr and Caspr2 (Ohara et al., 2000; Gollan et al., 2002; Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003; Arroyo et al., 2004). These mice developed normally and showed no signs of neurological abnormalities (Yi et al., 2005). Immunofluorescence analysis of teased sciatic nerves isolated from adult 4.1B−/− mice showed that Na+ channels and gliomedin were present at the nodes of Ranvier (Fig. 6A–J). Caspr and contactin were present at the PNJ, which had comparable size to wild-type nerves. Similar results were obtained using an antibody to NF155 (data not shown). However, in marked contrast to wild-type animals, Caspr2, TAG-1, PSD93, and Kv1.2 were not concentrated at the JXP in 4.1B−/− nerves. In accordance with previous observations (Arroyo et al., 1999), Kv1.2 was located throughout the internodal region in a double strand that apposes the inner mesaxon of the myelin sheath and forms a circumferential ring just below the inner aspect of the Schmidt–Lanterman incisures (Fig. 6K–M). Remarkably, 4.1B−/− mice exhibit an identical phenotype to mice lacking Caspr2 or TAG1 (Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003), further supporting the conclusion that the interaction of Caspr2 with protein 4.1B is required for its localization at the JXP and the assembly of the JXP complex (Fig. 6N).

Figure 6.

Impaired formation of the JXP domain in peripheral nerves of mice lacking protein 4.1B. Teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice (WT) (A–E), or 4.1B-null mice (4.1B−/−) (F–J), were labeled with antibodies to Na+ channels (NaCh) and contactin (A, F), TAG-1 and gliomedin (Gldn) (B, G), Caspr2 and Caspr (C, H), PSD93 and Caspr (D, I), or Kv1.2 and Caspr (E, J). The organization of the nodal environs in WT and 4.1B−/− nerves is schematically depicted on the right. JX, Juxtaparanodes; PN, paranodes; ND, nodes of Ranvier; IN, internodes. K–M, Triple immunofluorescence labeling of teased sciatic nerve fibers isolated from wild-type (K) or 4.1B−/− (L, M) animals, using antibodies to Kv1.2, Caspr, and NaCh. Note that Kv1.2 channels are located in a double line along the juxtamesaxon and below the Schmidt–Lanterman incisures. Scale bars, 10 μm. N, Schematic drawing illustrating the localization of protein 4.1B, Caspr, and Caspr2 along myelinated axons in wild-type and 4.1B−/− mice.

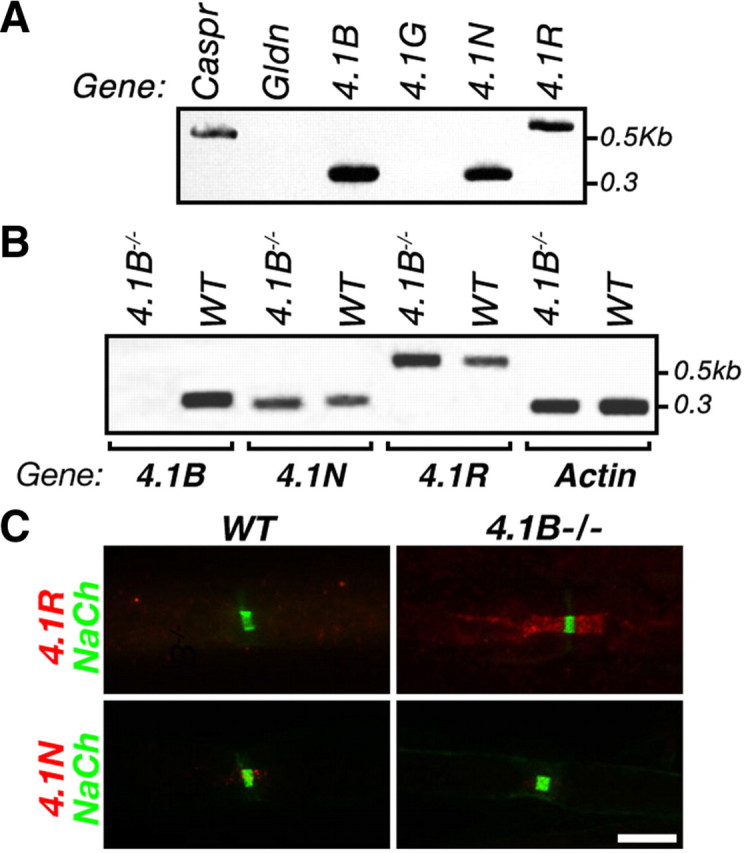

The finding that 4.1B−/− mice exhibit no paranodal abnormalities is unexpected given the inability of C1d4.1 transgene to fully rescue the Caspr-null phenotype (Fig. 4) and thus may suggest that other 4.1 proteins compensate for the absence of protein 4.1B. To test this possibility, we first analyzed the expression of all four protein 4.1 genes in dorsal root ganglia neurons (Fig. 7A). Of the four genes examined (i.e., 4.1R, 4.1N, 4.1G, and 4.1B), protein 4.1R, 4.1N, and 4.1B transcripts were present in sensory peripheral neurons. We next performed RT-PCR analysis on DRG mRNA isolated from 4.1B−/− and wild-type mice using specific primers that recognize the three neuronal 4.1 genes. This analysis revealed a slight increase in the amount of 4.1R transcript in 4.1B−/− compared with wild-type mice. Last, we immunolabeled teased sciatic nerves of wild-type or 4.1B−/− mice using antibodies to protein 4.1R or protein 4.1N (Fig. 7C). Surprisingly, although protein 4.1R was almost undetectable in wild-type axons, it was concentrated at the PNJ in the absence of protein 4.1B. These results indicate that protein 4.1R compensates for the loss of protein 4.1B at the PNJ in myelinated 4.1B−/− axons.

Figure 7.

Protein 4.1R is concentrated at the PNJ in the absence of 4.1B. A, Expression of protein 4.1 family members in peripheral sensory neurons. Purified rat DRG neuron mRNA was used as a template for RT-PCR using specific primer sets that recognize each of the 4.1 genes. Caspr and gliomedin (Gldn) were used as controls for genes that are expressed in DRG neurons or Schwann cells, respectively. The location of size markers is shown on the right in kilobases. B, Expression of neuronal 4.1 genes in the absence of protein 4.1B. RT-PCR analysis was done on DRG mRNA isolated from 4.1B−/− and wild-type mice using specific primers that recognize 4.1B, 4.1N, 4.1R, and actin genes. C, Protein 4.1R is concentrated at the PNJ in 4.1B−/−. Double immunofluorescence labeling of teased sciatic nerves isolated from wild-type mice (WT), or protein 4.1B nulls (4.1B−/−), using antibodies to Na+ channels (NaCh), and protein 4.1R or protein 4.1N as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

A functional nervous system requires the precise localization of ion channels and receptors at distinct membrane domains, where they are optimally positioned for their function. Formation and maintenance of these specialized membrane domains in neurons are achieved by a combination of different sorting and targeting mechanisms, selective endocytosis, and the restriction of lateral diffusion of membrane proteins, as well as by specific retention mechanisms (Lasiecka et al., 2009). The latter two processes are often controlled through the association of transmembrane proteins with the underlying cytoskeleton (Susuki and Rasband, 2008). Three specialized membrane domains are found at and around the nodes of Ranvier and include the nodes, where Na+ channels are clustered, the PNJ, and the JXP, where Kv1 channels are accumulated (Poliak and Peles, 2003). The formation of the PNJ and the assembly of the JXP complex depend on axon–glia interaction mediated by Caspr and Caspr2, respectively (Bhat et al., 2001; Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003). In this study, we used complementary in vivo transgenic/rescue and gene knock-out approaches to show that the cytoskeletal linker protein 4.1B, which interact with both of these CAMs, plays an essential role in their membrane expression and, consequently, in the organization of myelinated axons.

Distribution of protein 4.1B in myelinated axons

Protein 4.1B belongs to a group of cytoskeletal proteins that serves as linkers between the plasma membrane and the actin cytoskeleton (Parra et al., 2000). In myelinated axons in both the PNS and the CNS, protein 4.1B colocalized with Caspr and Caspr2 at the PNJ and the JXP, respectively (Ohara et al., 2000; Poliak et al., 2001; Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003) and thus may provide a link between the axolemma and the axonal cytoskeleton at these sites. During development of myelinated axons, Caspr and Caspr2 appear before protein 4.1B, suggesting that they may recruit it to the axolemma (Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003). In agreement, clustering of the Caspr–contactin complex on the cell surface results in the immobilization of protein 4.1B into these clusters (Gollan et al., 2002). Furthermore, the distribution of protein 4.1B is altered in myelin mutants (Poliak et al., 2001; Gollan et al., 2002), as well as after experimental demyelination (Arroyo et al., 2004). Similarly, null mutations in neurexin IV, the Drosophila homolog of Caspr and Caspr2, leads to the complete absence of protein 4.1/coracle from septate junctions (Baumgartner et al., 1996). In contrast, we show that protein 4.1B immunoreactivity in sciatic nerves isolated from either Caspr- or Caspr2-null mice was indistinguishable from wild-type nerves, arguing against a role for these CAMs in the membrane recruitment of protein 4.1B. However, it should be noted that the presence of protein 4.1B in Caspr−/− paranodes may be attributable to the accumulation of Caspr2 at this site. Similarly, the presence of protein 4.1B at the JXP in Caspr2−/− axons could be attributed to the expression of Necl1 adhesion molecule that is located at this site (Maurel et al., 2007; Spiegel et al., 2007). In line with this latter possibility, Necls were shown to interact with 4.1 proteins (Yageta et al., 2002) and to recruit protein 4.1B to synapses (Hoy et al., 2009).

Role of protein 4.1B in the formation of a membrane barrier at the PNJ

The PNJ serves as a membrane barrier that excludes juxtaparanodal components from the nodes of Ranvier (Rosenbluth, 2009). The formation of such membrane barriers and the assembly of specialized membrane at nodes of Ranvier and the axonal initial segment depend on the underlying actin/spectrin cytoskeleton mesh (Bennett and Healy, 2008; Susuki and Rasband, 2008). At the PNJ, protein 4.1B colocalized and associates with αII and βII spectrin, as well as with ankyrin B, suggesting that these cytoskeletal proteins may be important constituents of this junction (Ogawa et al., 2006). To begin analyzing the contribution of the axonal cytoskeleton to the formation of the PNJ, and particularly to its membrane barrier function, we examined the function of a mutant Caspr lacking its protein 4.1-binding site. We show that this mutant was targeted to the PNJ and was able to assemble the paranodal adhesion complex (i.e., to recruit contactin and NF155 to the PNJ). In accordance with a previous study (Gollan et al., 2002), we found that the paranodal area occupied by Caspr-d4.1 was on average 28% smaller than the area occupied by the Caspr-FL transgene, suggesting that the interaction of Caspr with protein 4.1B is required for its stabilization at the cell surface. In marked contrast to nerves expressing the full-length Caspr molecule, in which Kv1 channels were completely eliminated from the PNJ in 80% of the sites, in Caspr-d4.1-expressing nerves these channels were mainly detected (78% of the sites) at both the PNJ and the JXP. During development of peripheral nerves, Kv1 channels are first detected at the paranodes and are translocated to the JXP with the gradual formation of the PNJ (Vabnick et al., 1999), suggesting that in Caspr-d4.1-expressing axons only a fraction of the paranodal Kv1 channels were excluded toward the JXP. These results indicate that the interaction between Caspr and protein 4.1B is required for the stable expression of Caspr on the paranodal axolemma and the generation of an efficient membrane barrier at this site. Given that Kv1.2 are still well segregated in heterozygous Caspr mice (our unpublished results), it is likely that the impaired PNJ barrier in Caspr-d4.1 transgene is attributable to its inability to interact with protein 4.1B rather than its reduced expression at the PNJ. In support of this suggestion, Kv1 channels are located at paranodes in sciatic nerves of the shambling (shm) mutant mouse, which expresses a truncated Caspr protein lacking its entire cytoplasmic domain (Sun et al., 2009).

Analysis of sciatic nerves isolated from 4.1B−/− mice revealed that Caspr, contactin, and NF155 were present at the PNJ. Kv1.2 as well as Caspr2 and TAG-1 were not present at the node or at the PNJ. In addition, we found that the localization of ankyrin B, another component of the paranodal cytoskeleton that associates with protein 4.1B (Ogawa et al., 2006), was indistinguishable from wild-type nerves (data not shown), further suggesting the formation of a normal PNJ in these mice. We provide a possible explanation for the discrepancy between the 4.1B-null and the Caspr-d4.1 transgene by showing that protein 4.1R accumulates at the PNJ in 4.1B−/− mice (Fig. 7C). 4.1R was demonstrated to bind Caspr (Menegoz et al., 1997) and thus could potentially compensate for the absence of 4.1B. Interestingly, an increase in the expression of 4.1G in the heart, as well as 4.1N in T-cells, was reported in mice lacking 4.1R (Stagg et al., 2008). Redundancy between 4.1 proteins was also suggested to explain the difference between in vitro (Lin et al., 2009) and in vivo (Wozny et al., 2009) role of 4.1N and 4.1G in the formation of glutamatergic synapses. Given that protein 4.1R accumulates at the PNJ in mice lacking 4.1B, it will require the generation of double 4.1B/4.1R-null mice to further understand the role of these proteins in myelinated axons.

Protein 4.1B is required for the accumulation of K+ channels at the JXP

Confinement of K+ channels at the JXP is regulated by axon–glia interaction mediated by an axonal adhesion complex of Caspr2 and TAG-1, which bind to TAG-1 present at the adaxonal membrane of myelinating Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes (Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003). An important finding of this work is the observation that protein 4.1B is required for the localization of Caspr2 and hence for that of Kv1 channels at the JXP. This conclusion is based on the inability of a Caspr2 mutant lacking its protein 4.1B-binding sequence to accumulate at the JXP, as well as on the absence of Caspr2 at this site in sciatic nerves isolated from protein 4.1B−/− mice. In both Caspr2−/−/C2d4.1 transgenic and 4.1B−/− mice, Kv1 channels, TAG-1, and PSD-93 were not accumulated at the JXP. Notably, Western blot analysis of sciatic nerve lysates using an antibody to Kv1.2 showed that similar amounts of K+ channels are present in wild-type and 4.1B−/− mice (data not shown), indicating that the reduction of these channels at the JXP resulted from their redistribution along the internodes. Caspr2 and Kv1.2 were still associated in 4.1B−/− brains (data not shown), indicating that protein 4.1B does not mediate the interaction between these two proteins. Remarkably, in terms of the molecular organization of myelinated axons, 4.1B−/− mice exhibit an identical juxtaparanodal phenotype with Caspr2−/− and TAG-1−/− mutants (Poliak et al., 2003; Traka et al., 2003). In all of these mutants, the nodes or Ranvier and the PNJ formed regularly, whereas the assembly of the juxtaparanodal domain was impaired.

Protein 4.1B may control the accumulation of Caspr2 at the JXP by regulating its transport, membrane insertion, and/or by stabilizing it at the axolemma. In this regard, epithelial cells express a Golgi-specific variant of protein 4.1B that is required for targeting of Na+/K+-ATPase to the plasma membrane (Kang et al., 2009). However, the presence of a Caspr2 mutant lacking its 4.1-binding sequence in axons argues against a role for 4.1B in axonal transport of Caspr2. In addition, protein 4.1B associates with Caspr and Caspr2 only after they have already reached the PNJ and JXP, respectively (Denisenko-Nehrbass et al., 2003), further supporting a role for protein 4.1B in membrane insertion and stabilization of Caspr2 at the juxtaparanodal axolemma.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS50220, the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, the Israel Science Foundation, the Shapell Family Biomedical Research Foundation at The Weizmann Institute, and the Wolgin Prize for Scientific Excellence. E.P. is the Incumbent of the Hanna Hertz Professorial Chair for Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroscience.

References

- Arroyo EJ, Xu YT, Zhou L, Messing A, Peles E, Chiu SY, Scherer SS. Myelinating Schwann cells determine the internodal localization of Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kvbeta2, and Caspr. J Neurocytol. 1999;28:333–347. doi: 10.1023/a:1007009613484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo EJ, Sirkowski EE, Chitale R, Scherer SS. Acute demyelination disrupts the molecular organization of peripheral nervous system nodes. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:424–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S, Littleton JT, Broadie K, Bhat MA, Harbecke R, Lengyel JA, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Prokop A, Bellen HJ. A Drosophila neurexin is required for septate junction and blood-nerve barrier formation and function. Cell. 1996;87:1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman JM, Bakema JE, van der Poel CE, van der Linden JA, van de Winkel JG, Leusen JH. Protein 4.1G binds to a unique motif within the Fc gamma RI cytoplasmic tail. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2069–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett V, Baines AJ. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1353–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett V, Healy J. Organizing the fluid membrane bilayer: diseases linked to spectrin and ankyrin. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat MA, Rios JC, Lu Y, Garcia-Fresco GP, Ching W, St Martin M, Li J, Einheber S, Chesler M, Rosenbluth J, Salzer JL, Bellen HJ. Axon-glia interactions and the domain organization of myelinated axons requires Neurexin IV/Caspr/Paranodin. Neuron. 2001;30:369–383. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer T, Sudhof TC. CASK and protein 4.1 support F-actin nucleation on neurexins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47869–47876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda AV, Kabbani N, Lin R, Levenson R. D2 and D3 dopamine receptor cell surface localization mediated by interaction with protein 4.1N. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:507–513. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnon C, Bel C, Goutebroze L, Maigret B, Girault JA, Faivre-Sarrailh C. PGY repeats and N-glycans govern the trafficking of paranodin and its selective association with contactin and neurofascin-155. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:229–241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle ME, Berglund EO, Murai KK, Weber L, Peles E, Ranscht B. Contactin orchestrates assembly of the septate-like junctions at the paranode in myelinated peripheral nerve. Neuron. 2001;30:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles P, Tait S, Faivre-Sarrailh C, Barbin G, Gunn-Moore F, Denisenko-Nehrbass N, Guennoc AM, Girault JA, Brophy PJ, Lubetzki C. Neurofascin is a glial receptor for the paranodin/Caspr-contactin axonal complex at the axoglial junction. Curr Biol. 2002;12:217–220. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman SK, Cai C, Mottershead DG, Haapalahti JP, Keinänen K. Surface expression of GluR-D AMPA receptor is dependent on an interaction between its C-terminal domain and a 4.1 protein. J Neurosci. 2003;23:798–806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00798.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisenko-Nehrbass N, Oguievetskaia K, Goutebroze L, Galvez T, Yamakawa H, Ohara O, Carnaud M, Girault JA. Protein 4.1B associates with both Caspr/paranodin and Caspr2 at paranodes and juxtaparanodes of myelinated fibres. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:411–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan L, Sabanay H, Poliak S, Berglund EO, Ranscht B, Peles E. Retention of a cell adhesion complex at the paranodal junction requires the cytoplasmic region of Caspr. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1247–1256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan L, Salomon D, Salzer JL, Peles E. Caspr regulates the processing of contactin and inhibits its binding to neurofascin. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1213–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom KL, Rasband MN. Intrinsic and extrinsic determinants of ion channel localization in neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1345–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horresh I, Poliak S, Grant S, Bredt D, Rasband MN, Peles E. Multiple molecular interactions determine the clustering of Caspr2 and Kv1 channels in myelinated axons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14213–14222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3398-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy J, Constable J, Vicini S, Fu Z, Washbourne P. SynCAM1 recruits NMDA receptors via protein 4.1B. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:466–483. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Q, Wang T, Zhang H, Mohandas N, An X. A Golgi-associated protein 4.1B variant is required for assimilation of proteins in the membrane. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1091–1099. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasiecka ZM, Yap CC, Vakulenko M, Winckler B. Compartmentalizing the neuronal plasma membrane from axon initial segments to synapses. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;272:303–389. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Khirug S, Cai C, Ludwig A, Blaesse P, Kolikova J, Afzalov R, Coleman SK, Lauri S, Airaksinen MS, Keinänen K, Khiroug L, Saarma M, Kaila K, Rivera C. KCC2 interacts with the dendritic cytoskeleton to promote spine development. Neuron. 2007;56:1019–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DT, Makino Y, Sharma K, Hayashi T, Neve R, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor extrasynaptic insertion by 4.1N, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:879–887. doi: 10.1038/nn.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Yan H, Othman T, Rivkees SA. Cytoskeletal protein 4.1G is a binding partner of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1 alpha. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:49–55. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel P, Einheber S, Galinska J, Thaker P, Lam I, Rubin MB, Scherer SS, Murakami Y, Gutmann DH, Salzer JL. Nectin-like proteins mediate axon Schwann cell interactions along the internode and are essential for myelination. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:861–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menegoz M, Gaspar P, Le Bert M, Galvez T, Burgaya F, Palfrey C, Ezan P, Arnos F, Girault JA. Paranodin, a glycoprotein of neuronal paranodal membranes. Neuron. 1997;19:319–331. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80942-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura W, Takakuwa Y, Tokimitsu R, Krauss SW, Kawashima M, Mohandas N. Regulation of CD44-protein 4.1 interaction by Ca2+ and calmodulin. Implications for modulation of CD44-ankyrin interaction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30322–30328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Schafer DP, Horresh I, Bar V, Hales K, Yang Y, Susuki K, Peles E, Stankewich MC, Rasband MN. Spectrins and ankyrinB constitute a specialized paranodal cytoskeleton. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5230–5239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0425-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara R, Yamakawa H, Nakayama M, Ohara O. Type II brain 4.1 (4.1B/KIAA0987), a member of the protein 4.1 family, is localized to neuronal paranodes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra M, Gascard P, Walensky LD, Gimm JA, Blackshaw S, Chan N, Takakuwa Y, Berger T, Lee G, Chasis JA, Snyder SH, Mohandas N, Conboy JG. Molecular and functional characterization of protein 4.1B, a novel member of the protein 4.1 family with high level, focal expression in brain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3247–3255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza L, Huang JK, Colman DR. Organizing principles of the axoglial apparatus. Neuron. 2001;30:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Nativ M, Lustig M, Grumet M, Schilling J, Martinez R, Plowman GD, Schlessinger J. Identification of a novel contactin-associated transmembrane receptor with multiple domains implicated in protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 1997;16:978–988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai AM, Thaxton C, Pribisko AL, Cheng JG, Dupree JL, Bhat MA. Spatiotemporal ablation of myelinating glia-specific neurofascin (Nfasc NF155) in mice reveals gradual loss of paranodal axoglial junctions and concomitant disorganization of axonal domains. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1773–1793. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Peles E. The local differentiation of myelinated axons at nodes of Ranvier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:968–980. doi: 10.1038/nrn1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Gollan L, Martinez R, Custer A, Einheber S, Salzer JL, Trimmer JS, Shrager P, Peles E. Caspr2, a new member of the neurexin superfamily, is localized at the juxtaparanodes of myelinated axons and associates with K+ channels. Neuron. 1999;24:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Gollan L, Salomon D, Berglund EO, Ohara R, Ranscht B, Peles E. Localization of Caspr2 in myelinated nerves depends on axon–glia interactions and the generation of barriers along the axon. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7568–7575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Salomon D, Elhanany H, Sabanay H, Kiernan B, Pevny L, Stewart CL, Xu X, Chiu SY, Shrager P, Furley AJ, Peles E. Juxtaparanodal clustering of Shaker-like K+ channels in myelinated axons depends on Caspr2 and TAG-1. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Dutting E, Enz R. Band 4.1 proteins are expressed in the retina and interact with both isoforms of the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 8. J Neurochem. 2008;105:2375–2387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth J. Multiple functions of the paranodal junction of myelinated nerve fibers. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:3250–3258. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer JL. Polarized domains of myelinated axons. Neuron. 2003;40:297–318. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DL, Tait S, Melrose S, Johnson R, Zonta B, Court FA, Macklin WB, Meek S, Smith AJ, Cottrell DF, Brophy PJ. Neurofascins are required to establish axonal domains for saltatory conduction. Neuron. 2005;48:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel I, Adamsky K, Eshed Y, Milo R, Sabanay H, Sarig-Nadir O, Horresh I, Scherer SS, Rasband MN, Peles E. A central role for Necl4 (SynCAM4) in Schwann cell-axon interaction and myelination. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:861–869. doi: 10.1038/nn1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg MA, Carter E, Sohrabi N, Siedlecka U, Soppa GK, Mead F, Mohandas N, Taylor-Harris P, Baines A, Bennett P, Yacoub MH, Pinder JC, Terracciano CM. Cytoskeletal protein 4.1R affects repolarization and regulates calcium handling in the heart. Circ Res. 2008;103:855–863. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XY, Takagishi Y, Okabe E, Chishima Y, Kanou Y, Murase S, Mizumura K, Inaba M, Komatsu Y, Hayashi Y, Peles E, Oda SI, Murata Y. A novel Caspr mutation causes the shambling mouse phenotype by disrupting axoglial interactions of myelinated nerves. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1207–1218. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181be2e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susuki K, Rasband MN. Spectrin and ankyrin-based cytoskeletons at polarized domains in myelinated axons. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:394–400. doi: 10.3181/0709-MR-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traka M, Dupree JL, Popko B, Karagogeos D. The neuronal adhesion protein TAG-1 is expressed by Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes and is localized to the juxtaparanodal region of myelinated fibers. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3016–3024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03016.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traka M, Goutebroze L, Denisenko N, Bessa M, Nifli A, Havaki S, Iwakura Y, Fukamauchi F, Watanabe K, Soliven B, Girault JA, Karagogeos D. Association of TAG-1 with Caspr2 is essential for the molecular organization of juxtaparanodal regions of myelinated fibers. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1161–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabnick I, Trimmer JS, Schwarz TL, Levinson SR, Risal D, Shrager P. Dynamic potassium channel distributions during axonal development prevent aberrant firing patterns. J Neurosci. 1999;19:747–758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00747.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RE, 4th, Lamb RS, Fehon RG. A conserved functional domain of Drosophila coracle is required for localization at the septate junction and has membrane-organizing activity. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1463–1473. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozny C, Breustedt J, Wolk F, Varoqueaux F, Boretius S, Zivkovic AR, Neeb A, Frahm J, Schmitz D, Brose N, Ivanovic A. The function of glutamatergic synapses is not perturbed by severe knockdown of 4.1N and 4.1G expression. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:735–744. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yageta M, Kuramochi M, Masuda M, Fukami T, Fukuhara H, Maruyama T, Shibuya M, Murakami Y. Direct association of TSLC1 and DAL-1, two distinct tumor suppressor proteins in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5129–5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Guo X, Debnath G, Mohandas N, An X. Protein 4.1R links E-cadherin/beta-catenin complex to the cytoskeleton through its direct interaction with beta-catenin and modulates adherens junction integrity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1458–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C, McCarty JH, Troutman SA, Eckman MS, Bronson RT, Kissil JL. Loss of the putative tumor suppressor band 4.1B/Dal1 gene is dispensable for normal development and does not predispose to cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10052–10059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.10052-10059.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Du G, Hu X, Yu S, Liu Y, Xu Y, Huang X, Liu J, Yin B, Fan M, Peng X, Qiang B, Yuan J. Nectin-like molecule 1 is a protein 4.1N associated protein and recruits protein 4.1N from cytoplasm to the plasma membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1669:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonta B, Tait S, Melrose S, Anderson H, Harroch S, Higginson J, Sherman DL, Brophy PJ. Glial and neuronal isoforms of Neurofascin have distinct roles in the assembly of nodes of Ranvier in the central nervous system. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1169–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]