Abstract

Spike timing precision is a fundamental aspect of neuronal information processing in the brain. Here we examined the temporal precision of input–output operation of dentate granule cells (DGCs) in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). In TLE, mossy fibers sprout and establish recurrent synapses on DGCs that generate aberrant slow kainate receptor–mediated excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPKA) not observed in controls. We report that, in contrast to time-locked spikes generated by EPSPAMPA in control DGCs, aberrant EPSPKA are associated with long-lasting plateaus and jittered spikes during single-spike mode firing. This is mediated by a selective voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA through persistent sodium current (INaP) activation. In control DGCs, a current injection of a waveform mimicking the slow shape of EPSPKA activates INaP and generates jittered spikes. Conversely in epileptic rats, blockade of EPSPKA or INaP restores the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling. Importantly, EPSPKA not only decrease spike timing precision at recurrent mossy fiber synapses but also at perforant path synapses during synaptic integration through INaP activation. We conclude that a selective interplay between aberrant EPSPKA and INaP severely alters the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs of chronic epileptic rats.

Keywords: dentate granule cells, INaP, kainate receptors, mossy fiber sprouting, spike timing, temporal lobe epilepsy

Introduction

Spike timing is a fundamental aspect of normal information processing (Buzsaki 2005; O'Keefe and Burgess 2005; Fries et al. 2007; Maurer and Mcnaughton 2007) and the ability to generate action potentials with high temporal precision in response to incoming excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) is an essential feature of adult neurons (Konig et al. 1996). Recently, it has been reported that in temporal lobe epilepsies (TLE), the hippocampus displays alterations of the temporal organization of neuronal firing in behaving animals beside epileptiform discharges (Lenck-Santini and Holmes 2008). In animal models of TLE and human patients, neuronal tissue undergoes major reorganization; some neurons die whereas others, that are severed in their inputs or outputs, sprout and form novel aberrant connections (Nadler 2003; Blaabjerg and Zimmer 2007; Dudek and Sutula 2007; Ben-Ari et al. 2008). This phenomenon called reactive plasticity is best documented in the dentate gyrus where granule cells axons (the so-called mossy fibers) sprout to form aberrant glutamatergic excitatory synapses onto other dentate granule cells (DGCs) (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Represa et al. 1987; Sutula et al. 1989; Isokawa et al. 1993; Mello et al. 1993; Franck et al. 1995; Okazaki et al. 1995; Buckmaster and Dudek 1999; Scharfman et al. 2003). Numerous studies have shown that these, in addition to changes in voltage-gated conductances (Bernard et al. 2004; Yaari et al. 2007; Beck and Yaari 2008), could promote the generation of epileptiform activities in the hippocampus (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Franck et al. 1995; Wuarin and Dudek 1996; Patrylo and Dudek 1998; Hardison et al. 2000; Gabriel et al. 2004; Morgan and Soltesz 2008). However the functional consequences of newly formed aberrant synapses on the temporal precision of input–output operation in target cells have not been investigated.

We have recently shown that DGCs in an animal model of TLE differ dramatically from control cells in that they display in addition to fast α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazol-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptor–mediated synaptic currents (EPSCAMPA) observed in control DGCs, long-lasting kainate receptor (KAR)–mediated synaptic currents (EPSCKA), originating from recurrent mossy fiber synapses (Epsztein et al. 2005). The shape of excitatory synaptic event and its modulation by voltage-gated conductances are important determinants of the temporal precision of hippocampal and neocortical cells operation (Fricker and Miles 2000; Maccaferri and Dingledine 2002; Axmacher and Miles 2004; Daw et al. 2006; Rodriguez-Molina et al. 2007). Therefore, we undertook to determine whether and how aberrant KAR-operated synapses with their slow kinetics will impact the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats.

We report a major decrease in the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats when compared with controls during single-spike mode discharge. Whereas DGCs from control rats display time-locked spikes, DGCs from chronic epileptic rats fire with a very low temporal precision. Jittered spikes are triggered by EPSPKA, and not by EPSPAMPA that generate time-locked spikes in both control and TLE conditions. The jitter is mediated by the selective voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA, but not EPSPAMPA, by persistent sodium current (INaP) leading to long-lasting plateaus. In control DGCs, mimicking the slow shape of EPSPKA by somatic current injection is sufficient to activate INaP and generates imprecise spiking as observed in DGCs from epileptic rats. Conversely, in epileptic rats, blockade of KARs or INaP restores high spike timing precision. Aberrant EPSPKA also drastically disrupt the spike timing precision at the principal cortical inputs of the dentate gyrus, that is the perforant path (PP); an effect also mediated by INaP activation.

We conclude that a selective interplay between aberrant mossy fiber-mediated EPSPKA and INaP, severely alters the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs of chronic epileptic rats.

Material and Methods

All experiments were approved by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicale Animal Care and Use Committee and the European Communities Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/EEC).

Pilocarpine Treatment

Adult male Wistar rats (∼2 months old; Janvier Breeding Center, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with pilocarpine hydrochoride (325–340 mg/kg dissolved in NaCl 0.9%) 30 min after a low dose of cholinergic antagonist scopolamine methyl nitrate (1 mg/kg, i.p.). Approximately 60% of the rats experienced class IV/V seizures (Racine 1972). After 3 h of status epilepticus, diazepam (8 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally. After a seizure-free period of several weeks, we selected for recordings and analysis only rats that experienced spontaneous seizures (4–14 months old; mean age = 6.7 ± 0.7 months old; chronic epileptic rats, n = 26) with a mossy fiber sprouting (see the Supplementary Fig. S1) according to the previously well-described Timm staining (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Represa et al. 1987). Age-matched untreated (naïve rats, n = 29) or treated with scopolamine and diazepam but NaCl (0.9%) instead of pilocarpine (sham rats, n = 5) were used as controls (range 3–13 months old; mean age = 5.5 ± 0.5 months old; n = 34). Because there was no difference between naïve and sham rats (not shown), the data were pooled together.

Preparation of Hippocampal Slices

Animals were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated. The brain was removed rapidly, the hippocampi were dissected, and transverse 400-μM-thick hippocampal slices were cut using HM650V MicroM tissue slicer in a solution containing the following (in mM): 110 choline, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 7 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, and 7 D-glucose (5 °C). Slices were then transferred for rest at room temperature (1 h) in oxygenated normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): 126 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.3 MgCl2, 2.0 CaCl2, and 10 D-glucose, pH 7.4.

Patch-Clamp Recordings

Whole-cell recordings of dentate gyrus granule cells from chronic epileptic and control rats were obtained using the “blind” patch-clamp technique in a submerged chamber (ASCF; 30–32 °C) using low resistance electrodes (5–8 MΩ). For current-clamp experiments, electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing the following (in mM): 130 KMeSO4, 5 KCl, 5 NaCl, 10 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2.5 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, and 0.5% biocytin, pH 7.25. For voltage-clamp experiments, the internal solution contained the following (in mM): 110 CsF, 20 CsCl, 11 sodium ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 2 MgATP, 0.4 NaGTP, 10 phosphocreatine. Access resistance ranged between 10 and 20 MΩ, and the results were discarded if the access resistance changed by more than 20%. For loose cell-attached patch recordings, pipettes were filled with ACSF. Whole-cell recordings were performed using an Axoclamp 2B and a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Data were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized (20 kHz) with a Digidata 1200 and 1322A (Molecular Devices) to a personal computer, and acquired using Axoscope 7.0 and Clampex 9.2 softwares (PClamp, Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices). Signals were analyzed off-line using MiniAnalysis 6.0.1 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA), and Clampfit 10.1 (Molecular Devices). AMPA/kainate receptor–mediated EPSPs were isolated in the presence of blockers of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) (40 μM D-APV or 10 μM MK801), GABAA (10 μM bicuculline), and GABAB (5 μM CGP 55845) receptors (Epsztein et al. 2005).

Electrical Stimulations

Small EPSPs (∼3–5 mV) were evoked by weak stimulations performed via a bipolar NiCh electrode (∼50 μm diameter, NI-0.7F, Phymep, Paris) positioned either in the inner one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus to stimulate proximal inputs (PI; i.e., associational/commissural inputs in controls and recurrent mossy fiber inputs in epileptic rats) or in the outer one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus to stimulate distal perforant inputs (PP) in control and epileptic rats. The stimulus intensity, pulse duration, and frequency were around 30V, 70 μs, and 0.2 Hz, respectively. Using these stimulation parameters DGCs always discharged in single-spike mode and never in burst firing mode. Following action potential, the decay of EPSP was curtailed due to a reset of the membrane potential as previously reported (Hausser et al. 2001). To examine the PI- and PP-EPSP–spike coupling, EPSPs were recorded at around −50 mV (threshold holding potential), a potential at which EPSPs triggered cell firing in about 50% of the trials both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats. Therefore, suprathreshold and subthreshold EPSPs could be recorded at the same potential, and EPSP kinetics could be analyzed together with EPSP–spike latency and spike timing precision (Fricker and Miles 2000; Maccaferri and Dingledine 2002). The spike latency was defined as the delay between EPSP onset and action potential peak; the degree of spike timing precision was assessed by calculating the SD of the spike latency from around 50 trials (jitter). All recordings were performed in the presence of 10 μM bicuculline, 40 μM D-APV (or 10 μM MK801), and 5 μM CGP 55845, except when otherwise stated. Because, it has been previously reported that PP-EPSP could display an enhanced NMDA receptor–mediated component leading to burst discharges in DGCs from kindled rats (Lynch et al. 2000), we also tested PP stimulations in the absence of NMDA receptors antagonists (but in the presence of GABAA and GABAB receptors antagonists). In our experimental condition, PP stimulations did not evoked burst but single-spike mode discharges in DGCs from epileptic rats (n = 9 out of 9 cells). Furthermore, the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling was not significantly different in the absence, (mean SD = 3.1 ± 0.3 ms; n = 9 cells) or in the presence (mean SD = 3.2 ± 0.5 ms, n = 9 cells, P > 0.05, not shown) of NMDAR blocker (40 μM D-APV). Therefore, NMDARs contributed neither to the firing mode nor to the temporal precision of PP inputs in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats when PP-EPSPs were evoked by weak stimulations. Moreover, PP-EPSPs were mediated by AMPAR, because they were fully abolished by 100 μM GYKI 52466 in both DGCs from control (n = 6) and epileptic rats (n = 6). To test the impact of PI-EPSP on PP-EPSP on spike timing precision (SD), the stimulation parameters were adjusted such that the summation of subthreshold PP-EPSPs with PI-EPSPs was not significantly different between control and epileptic rats (mean summation = 165 ± 7%, n = 8 cells in control rats; mean summation = 157 ± 8%, n = 11 cells in epileptic rats; P > 0.05). Accordingly, the total amplitude of the summed subthreshold EPSP (PP-EPSP + PI-EPSP) was not significantly different between control and epileptic rats (mean = 5.9 ± 0.4 mV, n = 8 cells in control rats; mean = 5.6 ± 0.5 mV, n = 11 cells in epileptic rats; P > 0.05). Different interstimulus intervals (ISI, ranging from 20 to 50 ms, mean ISI = 36.3 ± 2.4 ms in 8 cells from control and mean ISI = 36.4 ± 2.0 ms in 11 cells from epileptic rats, P > 0.05) were tested in DGCs from control and epileptic rats. Because spike timing precision was not correlated with ISI (r = −6 × 10−4, n = 8 cells from control rats; r = 0.33, n = 11 cells epileptic rats, P > 0.05), the data were pulled together. For PP-EPSP integration with other PP-EPSP inputs, 2 electrodes were placed in the outer one-third of the molecular layer on each side of the recording site and >200 μm apart from each-other mean (mean ISI = 35.0 ± 2.4 ms; mean summation = 167 ± 6%; n = 4).

Data Analysis

The kinetics of synaptic events was analyzed using MiniAnalysis 6.0.1 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). The experiments performed in the presence of AMPAR antagonist [50–100 μM 1-(4-aminophenyl)-4-methyl-7,8-methylenedioxy-5H-2,3-benzodiazepine (GYKI 52466)] or KAR blocker [10 μM (2S,4R)-4-methylglutamic acid (SYM 2081)] enabled us to determine the statistical limit to classify events as EPSPKA (half width > 50 ms, see Fig. 2) or EPSPAMPA (half width < 50 ms, P < 0.05, see Figs 1 and 2), respectively. The charge transfer through the AMPAR- and KAR-mediated EPSP was calculated as the EPSP integral on 400-ms time window from onset. MiniAnalysis 6.0.1 was also used for the measurement of amplitude of action potentials (from threshold defined as the membrane potential at which the rate-of-rise of voltage crossed 50 V/s; Kole and Stuart 2008) and half width of action potentials. Calculation of firing probability was based on the calculation of the ratio of suprathreshold EPSPs over all EPSPs using 100 trials of electrical stimulation.

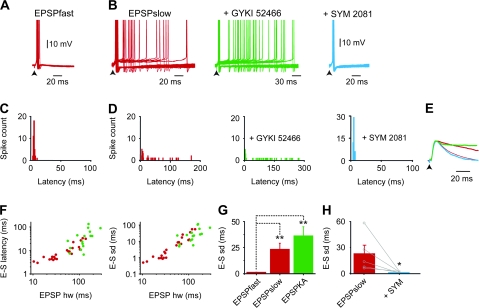

Figure 2.

Postsynaptic KARs decrease the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in granule cells from epileptic rats. (A) Superimposed suprathreshold EPSPs recorded in a granule cell from an epileptic rat triggering single spikes at precise latencies (mean latency SD = 1.2 ms, Vm = −50.7 mV). Note that precise spike firing is triggered by EPSPfast average scaled subthreshold EPSPs shown in E). (B) Superimposed suprathreshold EPSP recorded from a granule cell from an epileptic rat triggering single spikes at variable latencies without AMPA/KA receptor antagonists (left red traces, mean SD = 58.4 ms, Vm = −50.7 mV) or in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466 (middle green traces, mean SD = 73.9 ms, Vm = −49.2 mV) or 10 μM SYM 2081 (right blue traces). Note that SYM 2081 converts highly variable single-spike mode discharge (left red traces) into precise one (latency SD = 0.91 ms, Vm = −51.3 mV). (C) Spike latency histograms of the cell shown in A (n = 39 spikes). (D) Spike latency histograms of the cell shown in B (left, n = 69 spikes); spike latency histogram of cells shown in B in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466 (middle, n = 48 spikes) or in the presence of 10 μM SYM 2081 (right, n = 53 spikes). (E) Superimposed scaled average subthreshold EPSPs from the cells shown in A (EPSPfast red thinner trace, hw = 14.6 ms) and B (EPSPslow red thicker trace, hw = 70.2 ms); in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466 (EPSPKA, green trace, hw = 280 ms) or in the presence of 10 μM SYM 2081 (blue trace, hw = 21.3 ms). (F) Scatter plots of EPSP–spike latency and SD plotted against EPSP half width (hw) for EPSPfast and EPSPslow (n = 12 and n = 11 cells, respectively, red symbols) and EPSPKA (in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466, n = 17 cells, green symbols). (G) Bar graph of the mean EPSP-spike latency SD for EPSPfast (n = 12 cells), EPSPslow (n = 11 cells, **P < 0.01) and EPSPKA (in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466, n = 17 cells, **P < 0.01). (H) Bar graphs of mean EPSP-spike latency SD in the absence (red columns, n = 7 cells) and in the presence of 10 μM SYM 2081 (blue columns, n = 5 cells, *P < 0.05). Note that SYM 2081 reduced EPSP-spike latency SD (n = 5 cells).

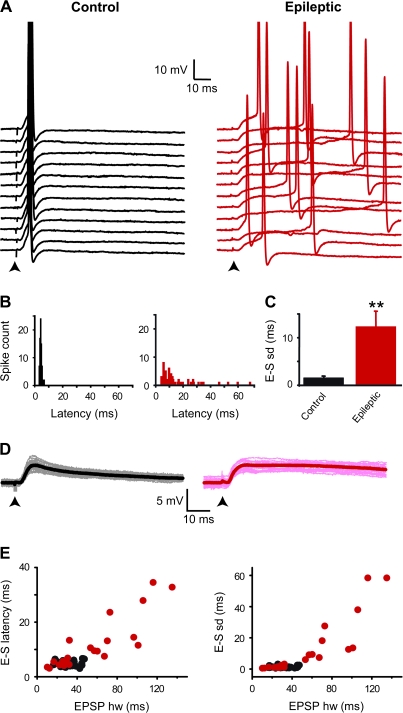

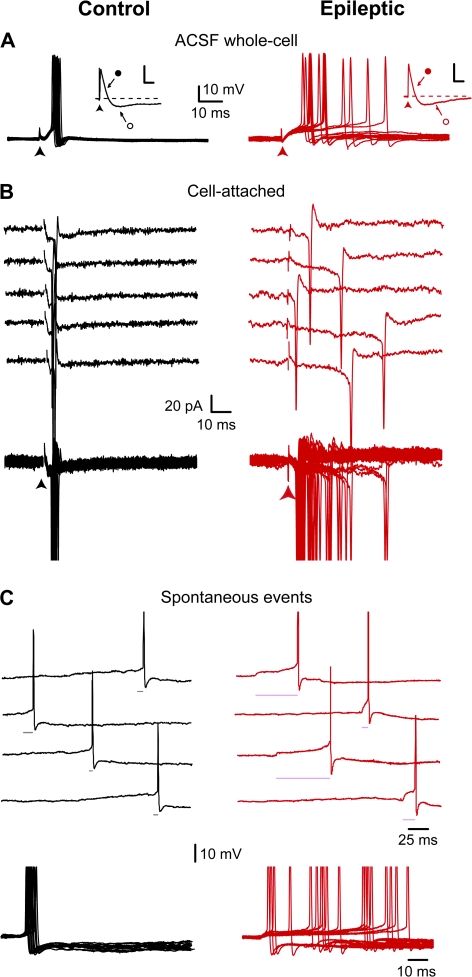

Figure 1.

Decreased temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in epileptic rats. (A) In a granule cell from a control rat, spikes were generated on the rising phase of the EPSPs (stimulation at arrow) at short latencies and with little variability (black traces on the left, mean latency SD = 0.9 ms, Vm = −51.4 mV). In a granule cell from an epileptic rat, spikes occurred both at short and at long latencies with a large variability (red traces on the right, mean latency SD = 12.6 ms, Vm = −51.3 mV). Traces are aligned at EPSP onset. (B) Spike latency histograms of the cells shown in A (control: black columns, n = 75 spikes; epileptic: red columns, n = 77 spikes). (C) Bar graph of the mean EPSP–spike latency SD in control cells (n = 38) and in cells from epileptic rats (n = 23, **P < 0.01). (D) Superimposed subthreshold EPSPs recorded simultaneously to the suprathreshold EPSPs shown in A in the same cells from control (grey traces, left) and epileptic (pink traces, right) rats at threshold holding potential; black and red traces depict the average subthreshold EPSPs from control (left) and epileptic (right) rats, respectively. (E) Scatter plots of the EPSP–spike (E–S) latency and latency SD plotted against EPSP half width (hw) for n = 38 granule cells from control (black circles) and n = 23 granule cells from epileptic rats (red circles). Note that in this and following figures, spikes are truncated and electrical stimulations (performed in the inner one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus) are indicated by black arrows below the traces; all recordings were performed in the presence of 10 μM bicuculline, 40 μM D-APV (or 10 μM MK801), and 5 μM CGP 55845, except when otherwise stated.

Simulated Synaptic Waveforms

Simulation of EPSPs were performed using somatic injection of a current with an exponentially rising and falling waveform: f(t) = a·((1 - exp(-t/τon))·(exp(-t/τoff)). For simulated EPSPAMPA (simEPSPAMPA), τon was set to 0.5 ms, and τoff to 10 ms. For simulated EPSPKA (simEPSPKA), τon was set to 2 ms, and τoff to 70 ms. The simulated EPSP had a constant amplitude (∼5 mV) and were recorded at stable holding potentials (Vh ∼ −50 mV, SD = 0.7 mV, n = 18), similarly to synaptically evoked EPSP in which we only considered experiments with holding potential displaying very small variations (Vh ∼ −50 mV, SD = 0.8 mV, n = 43). The current waveform generate either fast simEPSPAMPA (rise time = 3.7 ± 0.5 ms, decay time = 19.7 ± 1.7 ms, half width = 21.2 ± 2.0 ms at Vrest ∼ − 70 mV; n = 5 cells, Fig. 4A) or slow simEPSPKA (rise time = 10.9 ± 0.5 ms, decay time = 109.7 ± 9.5 ms, half width = 82.0 ± 3.3 ms at Vrest ∼ −70 mV; n = 18 cells, Fig. 4B). SimEPSPKA were also injected before evoked PP-EPSPs in control DGCs (mean delay = 35.0 ± 1.5 ms; mean amplitude of simEPSPKA + PP-EPSP = 5.8 ± 0.4 mV, n = 10 cells).

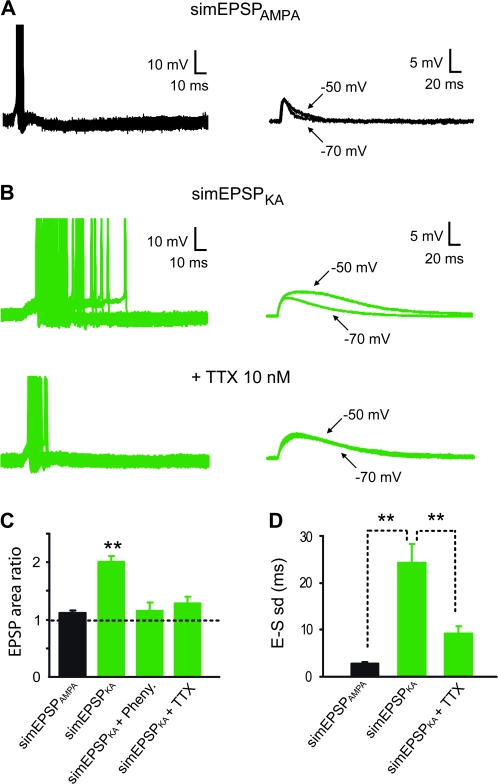

Figure 4.

SimEPSPKA generate spike with low temporal precision in granule cells from control rats. Simulated EPSPs (simEPSPs) with different kinetics were generated through somatic current injections to mimic synaptic AMPAR or KAR-mediated EPSPs in granule cells from control rats. (A) simEPSPAMPA (right, −50 mV) evoked time-locked spikes (left superimposed traces) and were not significantly amplified with depolarization from −70 mV to −50 mV (right, superimposed average traces). (B) simEPSPKA (upper right, −50 mV) generated late and highly variable spikes (upper left superimposed traces) and showed a significant amplification with depolarization to −50 mV (upper right superimposed traces) in a granule cells from a control rat. In the presence of TTX 10 nM, EPSP-spike coupling temporal precision was significantly restored (bottom left traces) and voltage-dependent amplification was abolished (bottom right traces). (C) Bar graph of mean amplification (ratio of simEPSP area at −50 vs. −70 mV) of simEPSPAMPA (black column, n = 7 cells), simEPSPKA (green column, n = 18 cells, P < 0.01), simEPSPKA in the presence of phenytoin (100–200 μM, n = 7 cells) and simEPSPKA in the presence of TTX (10 nM, n = 9 cells) in granule cells from control rats. (D) Bar graph of EPSP-spike latency standard deviation (E–S SD) of simEPSPAMPA (black column, n = 8 cells), simEPSPKA (green column, n = 18 cells, **P < 0.01), and simEPSPKA in the presence of TTX (10 nM, n = 9 cells, **P < 0.01) in granule cells from control rats.

Statistical Analysis

All values are given as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat 3.1 (Systat Software, Richmond, CA). For comparison between 2 groups, the unpaired Student's t-test was used if the data passed the normality and the equal variance test; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test was used. For comparison within one group before and after a pharmacological treatment or at different holding potential, a paired Student's t-test was used if the data passed the normality test; otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. n refers to the number of cells, except when otherwise stated.

Morphological Analysis

Timm staining was performed routinely on sections used for electrophysiological recordings. In brief, sections were incubated for 15 min in a Na2S solution and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Slices were resectioned in a cryostat (40 μm thick) and processed with the Timm solution (Epsztein et al. 2005).

Chemicals

Drugs were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) (TTX, biocytin, pilocarpine hydrochloride, and scopolamine methyl nitrate), Tocris Neuramin (Bristol, UK) (GYKI 52466, SYM 2081, bicuculline, NBQX, CNQX, D-APV, MK 801, CGP 55845, 4-AP, CdCl2 phenytoin), and Roche (Basel, Switzerland) (diazepam).

Results

Shift of EPSP–Spike Coupling from High to Low Temporal Precision in DGCs from Epileptic Rats

Somatic whole-cell recordings were made from 111 DGCs from control rats and 95 DGCs from chronic epileptic rats ∼5 months after the initiating status epilepticus. All included animals experienced spontaneous seizures together with mossy fiber sprouting (Supplementary Fig. S1; Epsztein et al. 2005). In keeping with earlier studies, the resting membrane potential, the input resistance, and the membrane time constant were similar in DGCs from control and epileptic rats (see Table 1, and Lynch et al. 2000; Epsztein et al. 2005). EPSPs were generated by electrical stimulations in the inner one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus at 0.2 Hz (EPSPs). To examine the EPSP–spike coupling, weak stimulations were used (see methods) in order to evoke small EPSPs (∼5 mV) at around −50 mV (threshold holding potential), a potential at which EPSPs triggered cell firing in single-spike mode (Fig. 1A) in about 50% of the trials (see Table 1) both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats. Therefore, suprathreshold and subthreshold EPSPs could be recorded at the same potential, and EPSP kinetics could be analyzed together with EPSP–spike latency and spike timing precision (Fricker and Miles 2000; Maccaferri and Dingledine 2002) (Fig. 1). The spike latency was defined as the delay between EPSP onset and action potential peak; the degree of spike timing precision was assessed by calculating the SD of the spike latency (jitter) from around 50 trials.

Table 1.

Intrinsic properties of DGCs from control and epileptic rats

| Control | Epileptic | |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −70.5 ± 0.7 (n = 32) | −68.3 ± 0.3 (n = 28) |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 260.2 ± 22.0 (n = 32) | 221.0 ± 13.3 (n = 28) |

| Membrane time constant (ms) | 17.7 ± 1.6 (n = 32) | 19.9 ± 1.3 (n = 28) |

| Action potential firing threshold (mV) | −40.6 ± 1.2 (n = 20) | −40.7 ± 1.1 (n = 23) |

| Spike amplitude (mV) | 53.7 ± 5.7 (n = 20) | 54.1 ± 6.0 (n = 23) |

| Spike half width (ms) | 1.05 ± 0.07 (n = 20) | 0.91 ± 0.04 (n = 23) |

| Firing probability (%) | 50.6 ± 6.4 (n = 20) | 49.6 ± 3.9 (n = 23) |

In a first set of experiments, AMPA/kainate receptor–mediated EPSPs were isolated in the presence of blockers of NMDA (40 μM D-APV or 10 μM MK801), GABAA (10 μM bicuculline), and GABAB (5 μM CGP 55845) receptors (Epsztein et al. 2005). In these conditions, EPSPs evoked in control DGCs generated time-locked spikes (mean SD = 1.6 ± 0.2 ms, n = 38 cells) at short latencies (mean = 5.5 ± 0.3 ms, n = 38 cells), corresponding to their rising phase (Fig. 1A–C). In contrast in epileptic rats, the spike latency was significantly longer with spikes generated either from the rising phase or during the long-lasting decay of EPSPs (up to 100 ms, mean latency = 11.3 ± 2.0 ms, n = 23 cells, P < 0.01, Fig. 1A,B), leading to an important decrease in spike timing precision (mean SD = 12.0 ± 3.6 ms, n = 23 cells, P < 0.01, Fig. 1C). These changes in EPSP spike timing precision were due neither to a difference in EPSP amplitude (average amplitude = 5.6 ± 0.4 mV, n = 23 cells in epileptic rats vs. 5.4 ± 0.2 mV, n = 38 cells in control rats, P > 0.05), nor to a change in intrinsic membrane properties, because action potential threshold, amplitude, half width and firing probability were not significantly different between DGCs from control and epileptic rats (P > 0.05; see Table).

Because EPSP kinetics plays an important role in the precision of EPSP–spike coupling in different neuronal populations (Fricker and Miles 2000; Maccaferri and Dingledine 2002; Rodriguez-Molina et al. 2007), we compared EPSP half width in DGCs from control and pilocarpine-treated animals (in the presence of blockers of NMDA, GABAA, and GABAB receptors). In control neurons, only fast kinetics EPSPs were observed (EPSPfast, half width < 50 ms, mean = 34.5 ± 2.1 ms, n = 38 cells, Fig. 1D,E) and triggered time-locked spikes (see above). In contrast, in DGCs from epileptic rats in addition to EPSPfast (half width < 50 ms, mean = 24.3 ± 2.2 ms, n = 12 cells, Fig. 2), slower EPSPs were observed (EPSPslow, half width > 50 ms, mean = 85.0 ± 8.2 ms, n = 11 cells, Fig. 1D,E and Fig. 2E,F). These EPSPslow generated spikes with low temporal precision (mean latency = 17.7 ± 3.0 ms, mean SD = 23.5 ± 5.9 ms, n = 11 cells, Fig. 2B,D,F,G), whereas EPSPfast generated time-locked spikes (mean latency = 5.5 ± 0.8 ms, mean SD = 1.4 ± 0.2 ms, n = 12 cells, Fig. 2A,C,F,G), as observed in control DGCs. Accordingly, there was a strong correlation between EPSP half width and EPSP–spike coupling precision (SD) in DGCs from epileptic rats (r = 0.87, n = 23 cells).

In conclusion, temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling is strongly reduced in DGCs from epileptic rats due to the presence of aberrant slow EPSPs.

Postsynaptic KARs Decrease the Temporal Precision of EPSP–Spike Coupling in DGCs from Epileptic Rats

We have previously shown that DGCs from epileptic rats additionally display aberrant slow synaptic events mediated by kainate receptors (KARs, EPSPKA) in addition to fast synaptic events mediated by AMPA receptors (EPSPAMPA) recorded in DGCs from control animals (Epsztein et al. 2005). We therefore examined the contribution of these slow EPSPKA to the decreased spike timing precision of DGCs from epileptic rats. In the presence of AMPA receptor (AMPAR) antagonist (GYKI 52466; 50–100 μM, in addition to NMDA, GABAA, and GABAB receptor antagonists), electrical stimuli evoked EPSPKA that were blocked by the addition of the mixed AMPAR/KAR antagonist CNQX (50 μM; n = 22; data not shown). EPSPKA had slow kinetics (mean half width = 116.4 ± 12 ms, n = 22 cells, Fig. 2E,F and Fig. 3A) similar to EPSPslow (P > 0.05) and generated spikes with long latencies (mean = 41.9 ± 9.3 ms, n = 17 cells) and high temporal variability (mean SD = 36.4 ± 8.9 ms; n = 17 cells; Fig. 2B,D,F,G). On the other hand, EPSPfast (half width < 50 ms) generating precise spike timing (Fig. 2A) were never recorded in the presence of GYKI 52466, confirming that they were mediated by AMPARs (Fig. 2B,F). These results suggest that late spikes with poor temporal precision are generated by the activation of postsynaptic KARs selectively present in DGCs from epileptic rats.

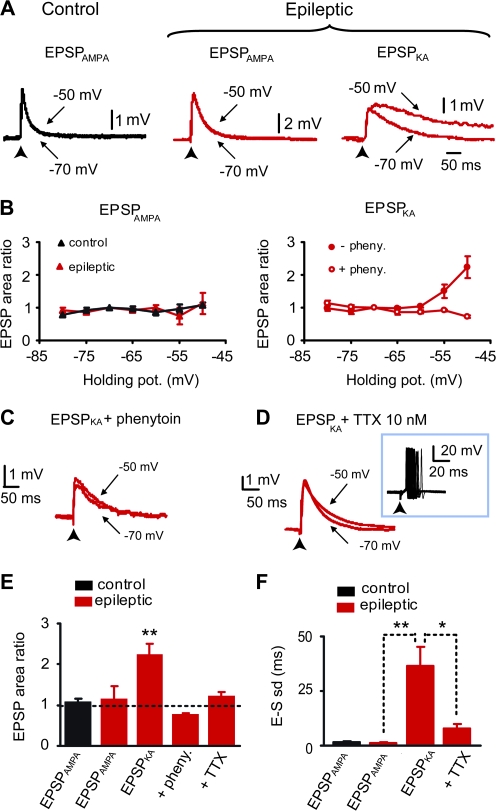

Figure 3.

Voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA but not EPSPAMPA via the activation of persistent sodium current. (A) Superimposed average evoked subthreshold EPSPAMPA recorded at threshold holding potential (−50 mV) and at Vrest (−70 mV) in granule cells from control (left, black traces) and epileptic rats (middle, red traces, in the presence of 10 μM SYM 2081); superimposed average evoked subthreshold EPSPKA recorded in a granule cell from an epileptic rat (right, red traces, in the presence of 100 μM GYKI 52466). (B) Scatter plot of mean amplification (ratio of EPSP area at −50 vs. −70 mV) versus membrane potential. Note that EPSPAMPA are not amplified with depolarization (left graph), both in control (black triangles, n = 5 cells) and in epileptic rats (red triangles, n = 5 cells); on the contrary, EPSPKA in epileptic rat (right graph) are significantly amplified with depolarization (filled circles, n = 8 cells). This amplification is completely prevented by phenytoin (100–200 μM, open circles, n = 5 cells). (C) Superimposed evoked EPSPKA recorded in the presence of phenytoin (200 μM) in epileptic rat at −50 and −70 mV. Note that the voltage-dependent amplification is completely abolished when persistent sodium current is blocked by phenytoin. (D) Superimposed evoked EPSPKA recorded in the presence of low concentration of TTX (10 nM) in epileptic rat at −50 and −70 mV. Note that the voltage-dependent amplification is completely abolished when persistent sodium current is blocked by TTX. Trace inset shows that 10 nM TTX does not prevent neuronal firing and increases spike timing reliability. (E) Bar graph of the mean amplification (ratio of EPSP area at −50 vs. −70 mV) for EPSPAMPA in control (n = 11 cells), EPSPAMPA in SYM 2081 in epileptic rats (n = 5 cells), EPSPKA in GYKI 52466 in epileptic rats (n = 13 cells, **P < 0.01), EPSPKA in the presence of phenytoin in epileptic rats (n = 5 cells), and EPSPKA in the presence of 10 nM TTX in epileptic rats (n = 6 cells). (F) Bar graph of EPSP-spike latency SD for EPSPAMPA in control (n = 20 cells), EPSPAMPA in SYM 2081 in epileptic rats (n = 5 cells), EPSPKA in GYKI 52466 in epileptic rats (n = 17 cells, **P < 0.01), and EPSPKA in the presence of 10 nM TTX in epileptic rats (n = 7 cells, *P < 0.05).

To further assess the role of postsynaptic KARs in the decreased spike timing precision in DGCs from epileptic rats, we tested the effect of a functional antagonist of KARs (10 μM SYM 2081; DeVries and Schwartz 1999; Cossart et al. 2002; Epsztein et al. 2005; Goldin et al. 2007) on EPSPslow (recorded in the presence of NMDA, GABAA, and GABAB receptors antagonists). SYM 2081 significantly reduced the half width of long-lasting EPSPs (from 82.1 ± 11.5 ms to 41.8 ± 6.3 ms, n = 5 cells, P < 0.02, Fig. 2E), the spike latency (from 17.5 ± 5.1 ms to 5.2 ± 0.6 ms, n = 5 cells, P < 0.05) and dramatically increased spike timing precision (mean SD: from 22.6 ± 9.7 ms to 1.4 ± 0.4 ms, n = 5 cells, P < 0.05, Fig. 2B,H). The mean half width of EPSPs recorded in the presence of SYM 2081 in DGCs from epileptic rats was not significantly different from that of EPSPs recorded in DGCs from control rats (P > 0.05, Fig. 3A). Accordingly, the mean spike latency and temporal precision were also not significantly different (P > 0.05). These EPSPs were blocked by AMPA receptors antagonist (GYKI 52466; 50–100 μM, not shown).

These data show that the decreased temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling observed in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats is mediated by KARs.

Voltage-Dependent Amplification of EPSPKA but not EPSPAMPA via the Activation of Persistent Sodium Current

The activation by EPSPs of voltage-gated conductances near threshold is an important parameter in the modulation of EPSP time course and of EPSP–spike coupling temporal precision (Stafstrom et al. 1985; Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Fricker and Miles 2000; Axmacher and Miles 2004; Vervaeke et al. 2006). The EPSP integral is a good index of voltage-dependent amplification (Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Fricker and Miles 2000). We therefore examined the integral of pure EPSPKA in DGCs from epileptic rats and pure EPSPAMPA in DGCs from control and epileptic rats between Vrest (∼−70 mV) and threshold holding potential (∼−50 mV). We found that the EPSPAMPA recorded in DGCs from control rats and EPSPAMPA recorded in DGCs from epileptic rats (in the presence of SYM 2081) were not significantly amplified with voltage (+7.1 ± 8.0% of change, n = 11 and +13.2 ± 32.8% of change; n = 5; respectively; P > 0.05; Fig. 3A,B,E). In contrast, EPSPKA recorded in DGCs from epileptic rats showed a strong voltage-dependent amplification (+122.3 ± 29.1%, n = 13 cells, P < 0.01, Fig. 3A,B,E). One candidate to mediate this effect is the persistent Na+ current (INaP) which is activated below firing threshold and amplifies EPSPs in hippocampal and neocortical neurons (Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Schwindt and Crill 1995; Andreasen and Lambert 1999; Fricker and Miles 2000). To test this hypothesis, we used phenytoin, a selective blocker of INaP in cortical and hippocampal neurons (Kuo and Bean 1994; Segal and Douglas 1997; Lampl et al. 1998; Fricker and Miles 2000; Yue et al. 2005). We found that phenytoin (100–200 μM) abolished the voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA (−24.3 ± 4.4%, n = 5 cells, P > 0.05, Fig. 3B,C,E). However, phenytoin prevented spikes to occur and precluded the assessment of EPSP–spike coupling temporal precision (see Fig. 3C). Therefore, we also used TTX at low nanomolar concentrations, that also selectively blocks INaP without preventing neuronal firing (Hammarstrom and Gage 1998; Del Negro et al. 2005; Yue et al. 2005; Kang et al. 2007; Koizumi and Smith 2008). In the presence of 10 nM TTX, the voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA was also abolished (+ 21.3 ± 10.1%, n = 6 cells, P > 0.05, Fig. 3D,E) and EPSPKA-spike latency was significantly reduced (from 41.9 ± 9.3 ms, n = 17 cells to 13.9 ± 2.5 ms, n = 7; P < 0.05), whereas spike timing precision was significantly increased (mean SD = 7.8 ± 2.0 ms, n = 7 cells in the presence of 10 nM TTX versus mean SD = 36.4 ± 8.9 ms; n = 17 cells in the absence of 10 nM TTX, P < 0.02, Fig. 3D,F).

Therefore, EPSPKA is selectively amplified with depolarization via the activation of INaP and this dramatically decreases the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats.

Simulated Slow EPSPKA Tune Control Granule Cell to Fire with a Low Temporal Precision

The most straightforward difference between EPSPKA and EPSPAMPA is their kinetics. We reasoned that this difference might explain the selective amplification of EPSPKA leading to jittered spikes in DGCs from epileptic rats. To test this hypothesis we injected depolarizing events through somatic current injections in DGCs from control rats (see methods) to simulate the slow kinetics of EPSPKA (simEPSPKA, rise time = 10.9 ± 0.5 ms, decay time = 109.7 ± 9.5 ms, half width = 82.0 ± 3.3 ms at Vrest ∼−70 mV; n = 18 cells, Fig. 4B). Fast simulated EPSPAMPA (simEPSPAMPA, rise time = 3.8 ± 0.3 ms, decay time = 18.8 ± 1.6 ms, half width = 21.1 ± 1.4 ms at Vrest ∼ −70 mV; n = 7 cells, Fig. 4A) were also evoked as a control of the somatic current injection procedure. Amplitude was adjusted during the experiment to generate small simEPSPs (∼5 mV) at threshold holding potential (∼−50 mV; average amplitude = 5.4 ± 0.4 mV, n = 18 for simEPSPKA and 6.0 ± 0.7 mV, n = 7 for simEPSPAMPA, P > 0.05). Amplification of simEPSPs was calculated from the ratio of integral at −70 and −50 mV as for synaptically evoked EPSPs. As expected, simEPSPAMPA were not amplified with depolarization in control DGCs (15.6 ± 5.1% of change, n = 7 cells, P > 0.05, Fig. 4A,C) and generated spikes at short latency (mean 8.7 ± 0.6 ms, n = 8 cells) with little variability (mean SD = 2.7 ± 0.4 ms, n = 8, Fig. 4A,D) as observed for synaptically evoked EPSPAMPA (see above). In contrast, simEPSPKA were strongly amplified with depolarization (+96.8 ± 9.5% of change, n = 18 cells, P < 0.001, Fig. 4B,C) and triggered spikes at very long latencies from a plateau potential (mean latency = 60.4 ± 13.5 ms, n = 18 cells) with a large variability (mean SD = 24.2 ± 4.0 ms, n = 18 cells, Fig. 4B,D) in control DGCs. EPSP–spike coupling latency and temporal precision (SD) were significantly different between simEPSPKA and simEPSPAMPA (P < 0.001). Therefore, in control DGCs current injections of a waveform mimicking the slow shape of EPSPKA is sufficient to trigger a voltage-dependent amplification leading to jittered spikes as observed in DGCs from epileptic rats. This amplification was due to the activation of INaP, because it was fully abolished by 100–200 μM phenytoin (+12.7 ± 14.1% of change between −70 and −50 mV, P > 0.05, n = 7 cells, Fig. 4C) or 10 nM TTX (+25.1 ± 11.6% of change between −70 and −50 mV, P > 0.05, n = 9 cells, Fig. 4B,C). Moreover, 10 nM TTX significantly reduced simEPSPKA-spike latency (from 54.0 ± 2.8 ms to 31.2 ± 4.7 ms, n = 9, P < 0.01) and increased spike timing precision (from 24.1 ± 3.4 ms to 9.1 ± 1.7 ms, n = 9, P < 0.01, Fig. 4B,D).

We conclude that the slow kinetics of EPSPKA is sufficient to activate INaP and tunes control DGCs to fire with a low temporal precision as observed in DGCs from epileptic rats.

Persistent Sodium Current is not Altered in DGCs from Epileptic Rats

INap is enhanced in cortical and subicular neurons from animal models and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Agrawal et al. 2003; Vreugdenhil et al. 2004). In order to clarify whether INaP could be modified in DGCs from epileptic animals, we performed a series of experiments in voltage-clamp mode. INaP is a Na+ current that activates below spike threshold and slowly inactivates (Crill 1996). INaP was unmasked by blocking K+ currents using a CsF-based intracellular solution (see methods) and by adding 5 mM 4-AP in the perfusing ACSF; Ca2+ currents were also suppressed by adding 200 μM CdCl2 in a phosphate-free ACSF, and by decreasing the external concentration of CaCl2 (CaCl2/MgCl2 ratio was 0.3 mM/4.3 mM). Recordings were performed in the additional presence of GABAergic and glutamatergic receptors blockers (10 μM bicuculline, 40 μM D-APV, and 10 μM NBQX). INaP was evoked by a slow depolarizing voltage-ramp command (speed 35 mV/s; −60 to −10 mV), in order to inactivate the large transient Na+ current, thereby revealing the smaller persistent current INaP (Supplementary Fig. S2). The current evoked by the same protocol in the presence of 1 μM TTX was then subtracted to isolate the TTX-sensitive INaP both in control and epileptic rats. In this condition, we observed that INaP displayed a similar I/V curve in DGCs from control and epileptic rats as shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Accordingly, the potential of its maximal activation was not different between control (–41.4 ± 1.4 mV, n = 7) and epileptic rat recordings (–37 ± 2 mV, n = 5, P > 0.05), and the maximal amplitude also did not show any significant change (111.1 ± 25.7 pA, n = 7, in control and 112 ± 10.4 pA, n = 5, in epileptic rat recordings, P > 0.05). Therefore, INaP is not modified in DGCs from epileptic rats as compared with control rats.

Reduced Temporal Precision of EPSP–Spike Coupling in Physiological Condition

Our experiments assessing temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling were carried out in the presence of a cocktail of antagonists (including NMDA and GABA receptor blockers). Because NMDAR-mediated synaptic events have a long duration and can generate spikes with low temporal precision (Maccaferri and Dingledine 2002), we assessed their contribution in the reduced spike timing precision observed in DGCs from epileptic rats (in the absence of NMDAR antagonists but in the presence of GABAA and GABAB receptors antagonists). Temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling was not significantly different in the absence (mean latency = 16.1 ± 2.3 ms and mean SD = 13.8 ± 3.1 ms; n = 18 cells) or in the presence of NMDARs blockers (40 μM D-APV or 10 μM MK801; mean latency = 11.3 ± 2.0 ms, mean SD = 12.0 ± 3.6 ms, n = 23 cells, P > 0.05, Supplementary Fig. S3).

GABAergic inhibition controls cell firing (Fricke and Prince 1984; Fricker and Miles 2000; Coulter and Carlson 2007) and can strongly restrain the temporal window of discharge in specific neuronal types (Pouille and Scanziani 2001; Gabernet et al. 2005; Luna and Schoppa 2008). It was therefore important to also determine the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs in the absence of GABAA receptor antagonist (i.e., in normal ACSF) both in control and epileptic animals. In this condition, electrical stimulations in the inner one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (at 0.2 Hz) evoked either an EPSP initiating firing or an EPSP followed by a di-synaptic IPSP preventing generation of action potentials both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats (Fig. 5A). When DGCs fired they displayed time-locked spikes in control rats (mean latency = 5.3 ± 0.5 ms, and SD = 1.7 ± 0.6 ms, n = 6), and jittered spikes in epileptic rats (mean latency = 15.7 ± 2.6 ms, and SD = 13.6 ± 3.3 ms, n = 15, Fig. 5A); both latency and SD values were statistically different between control and epileptic rats (P < 0.01). Thus, DGCs from epileptic rats still exhibited a strong reduction of temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in normal ACSF condition. In addition, we assessed the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in less invasive recording conditions (using the loose-patch configuration, see Methods). This further confirmed that DGCs from epileptic rats displayed jittered spikes (SD: ranging from 0.3 to 9.9 ms, mean SD = 5.3 ± 1.5 ms, n = 13) in contrast to DGCs from control rats that discharged with a high temporal precision (SD: ranging from 0.4 to 1.3 ms, mean SD = 0.7 ± 0.2 ms, n = 7, P < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Many of our recordings also included several spontaneous EPSPs that generated action potentials in single-spike mode. We also examined the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling for these events. In DGCs from control rats (n = 8), spontaneous EPSPs always triggered spikes from their rising phase leading to a high temporal precision, whereas in DGCs from epileptic rats (n = 15) spontaneous EPSPs displayed a variable temporal pattern of EPSP–spike coupling with spikes generated either from the rising phase or during the long-lasting plateaus of spontaneous EPSPs (Fig. 5C). In vivo, the membrane potential of DGCs spontaneously fluctuates between a hyperpolarized state (down state) and a depolarized state (up-state) (Hahn et al. 2007). In a few cases, where the membrane potential showed spontaneous up-down state–like behavior in DGCs from epileptic rats (n = 3), EPSPKA evoked during the up-state–like period generated long-lasting plateaus associated with late spikes (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Reduced temporal precision of EPSP-spike coupling in physiological conditions. These experiments were performed in ACSF, in the absence of GABA and NMDA receptor blockers. (A) Superimposed suprathreshold EPSPs recorded in a granule cell from control (black traces) and epileptic (red traces) rats. Note time-locked (SD = 1.0 ms) and jittered spikes (SD = 13.4 ms) in control and epileptic rats, respectively. When EPSP (close circle) is followed by a di-synaptic IPSP (open circle) this shortens EPSP decay and prevents the generation of action potentials both in DGCs from control (black inset) and epileptic (red inset, scale bars: 2 mV, 50 ms) rats. (B) Individuals (top) and superimposed (bottom) loose cell-attached recordings of spiking in response to electrical stimulations in a granule cell from control (black traces) and epileptic (red traces) rats. Note time-locked (SD = 0.6 ms) and jittered spikes (SD = 9.9 ms) in control and epileptic rats, respectively. (C) Continuous recordings of spontaneous suprathreshold EPSPs (top) and superimposed spontaneous suprathreshold EPSPs (bottom, aligned on the rising phase) in a granule cell from control (black traces) and epileptic (red traces) rats. Note that spontaneous EPSPs always trigger spikes from their rising phase in the granule cell from control rat, whereas in the granule cell from epileptic rat spikes are generated either from the rising phase or during the long-lasting plateau of spontaneous EPSPs; EPSP-spike latency is indicated by a horizontal line.

Therefore, DGCs from epileptic rats exhibit a strong shift from high to low temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in physiological conditions.

Aberrant EPSPKA Tune PP-EPSPs to Fire with a Low Temporal Precision during Synaptic Integration

Spiking often occurs through synaptic integration of different inputs (Magee 2000). One important question was thus to determine whether, in epileptic animals, INaP activated by aberrant EPSPKA could also impact the temporal precision of the cortical input (i.e., the PP) during synaptic integration. This is likely to occur given the high frequency of ongoing excitatory synaptic events in DGCs from epileptic rats (Wuarin and Dudek 2001; Epsztein et al. 2005) and the fact that EPSPKA represent half of the spontaneous glutamatergic synaptic transmission in these cells (Epsztein et al. 2005). To address this question, we first compared the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling of PP inputs alone in DGCs from control and epileptic animals. Weak stimulations of PP evoked AMPAR-mediated EPSPs (amplitude ∼3–5 mV, see Methods) that triggered cell firing in single-spike mode with a high temporal precision both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats (mean SD = 3.5 ± 0.3 ms, n = 38 cells from control rats; mean SD = 3.1 ± 0.3 ms, n = 23 cells from epileptic rats; P > 0.05; Fig. 6A,B,D).

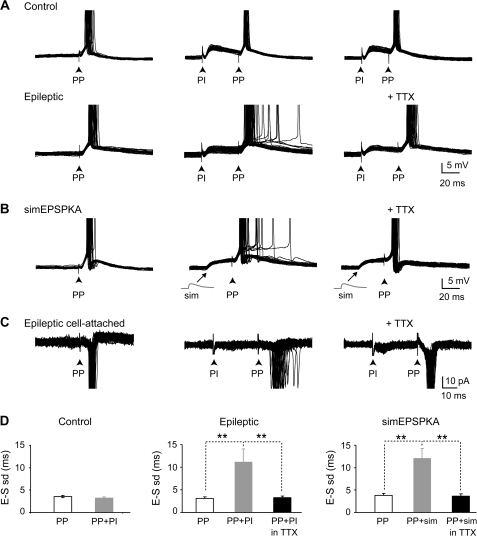

Figure 6.

Aberrant EPSPKA tune PP-EPSPs to fire with a low temporal precision during synaptic integration. (A) Control: superimposed suprathreshold EPSPs evoked by stimulation (black arrow) of the PP in the outer one-third of the molecular layer alone (left) or following PI by stimulation in the inner one-third of the molecular layer (ISI = 40 and 30 ms; middle and right) in a granule cell from control rat. Note that PP-EPSPs evoked time-locked spikes in single-spike mode following PP stimulation alone (SD = 2.8 ms) and that the temporal precision of PP-EPSP-spike coupling was not modified during synaptic integration with PI-EPSP (SD = 1.2 ms, ISI = 40 ms; SD = 1.3 ms, ISI = 30 ms). Epileptic: same protocol in a DGC from an epileptic rat. Note that PP-EPSPs also evoked time-locked spikes in single-spike mode following PP stimulation alone (SD = 2.8 ms) but that the temporal precision of PP-EPSP-spike coupling is greatly decreased during synaptic integration with PI-EPSPKA (SD = 10.2 ms, ISI = 40 ms; middle). This effect was fully reversed by 10 nM TTX superfusion (SD = 2.8 ms, ISI = 40 ms; right). (B) Superimposed supra-threshold EPSPs evoked by PP stimulations alone (left) or following somatic injection of a simulated EPSPKA (sim; middle) in a granule cell from control rat. Note that PP-EPSPs evoked time-locked spikes in single-spike mode following PP stimulation alone (SD = 4.3 ms) but jittered spikes during synaptic integration with simulated EPSPKA (SD = 11.3 ms, ISI = 30 ms). This effect was fully reversed by 10 nM TTX superfusion (SD = 1.6 ms, ISI = 30 ms; right). (C) Same as in A-epileptic in more physiological conditions (i.e., in ACSF without any drug and in cell-attached configuration). Note that PP stimulation also evoked time-locked spikes in single-spike mode in these conditions (SD = 0.8 ms, ISI = 30 ms; right) and jittered spikes following PI stimulation (SD = 4.0 ms; ISI = 30 ms; middle). This effect was fully reversed by 10 nM TTX superfusion (SD = 1.0 ms, ISI = 30 ms; right). (D) Bar graph of the mean EPSP-spike latency standard deviation (E–S SD) for PP stimulation alone (PP, white), PP stimulations following PI stimulations (PP + PI; grey) or PP stimulations following PI stimulations in the presence of TTX 10 nM (PP + PI in TTX, black) for DGCs from control rats (n = 8 cells; P > 0.05; left), epileptic rats (n = 11 cells for PP and PP + PI, and n = 5 for PP + PI in TTX; **P < 0.01; middle) and simEPSPKA (n = 10 cells for PP and PP + simEPSPKA, and n = 8 for PP + simEPSPKA in TTX; **P < 0.01; right).

We next tested the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling during synaptic integration with PI evoked by stimulations in the inner one-third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats. PP-EPSPs were evoked following subthreshold PI-EPSPs (ISI 20–50 ms, see methods). In control DGCs, integration with PI-EPSPs did not significantly altered the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling (PP-EPSP + PI-EPSP: mean SD = 3.2 ± 0.3 ms versus PP-EPSP alone: mean SD = 3.5 ± 0.3 ms, n = 8 cells, P > 0.05; Fig. 6A,D). Conversely, in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats, integration with PI-EPSPs significantly lowered the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling (PP-EPSP + PI-EPSP: mean SD = 11.1 ± 2.9 ms versus PP-EPSP alone: mean SD = 3.1 ± 0.4 ms, n = 11 cells, P < 0.001; Fig. 6A,D). This effect was specific to integration with PI inputs because integration with other PP inputs did not alter the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling (PP1-EPSP + PP2-EPSP: SD = 2.3 ± 0.4 vs. PP1-EPSP alone = 2.9 ± 0.2, n = 4 cells; P > 0.05; not shown). Furthermore, a decreased temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling was only observed during integration with slow PI-EPSPKA (hw > 50 ms) but not with fast PI-EPSPAMPA (hw < 50 ms; PP-EPSP + PI-EPSPAMPA: mean SD = 2.5 ± 0.5 ms versus PP-EPSP alone: mean SD = 2.6 ± 0.5 ms, n = 7 cells, P > 0.05) in DGCs from epileptic rats. To determine the putative role of INaP in the decreased temporal precision of PP-EPSPs, during synaptic integration with PI-EPSPKA, a low dose of TTX (10 nM) was applied to specifically inhibit this conductance (Hammarstrom and Gage 1998; Kang et al. 2007). In TTX, the spike timing precision of PP–EPSPs was fully restored (mean SD = 3.3 ± 0.4 ms, n = 5 cells, P > 0.05 when compared with PP-EPSPs alone; Fig. 6A,D). To determine whether activation of INaP is sufficient to alter spike timing precision of the PP inputs, beside any alteration occurring in chronic epileptic rats, slow simEPSPKA (amplitude ∼3–5 mV) were injected in control DGCs to activate INap shortly before PP-EPSPs (see methods). In control DGCs, simEPSPKA lowered significantly temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling (PP-EPSP + simEPSPKA: mean SD = 12.0 ± 2.2 ms versus PP-EPSP alone: mean SD = 3.8 ± 0.5 ms, n = 10 cells, P < 0.01; Fig. 6B,D). This effect was fully reversed by 10 nM TTX (PP-EPSP + simEPSPKA in TTX: mean SD = 3.6 ± 0.5 ms, n = 8 cells, P > 0.05 when compared with PP-EPSP alone; Fig. 6B,D). Therefore, slow EPSPKA is necessary and sufficient to alter the spike timing precision of PP-EPSPs through INaP activation in control and TLE DGCs. Finally, to determine whether these effects also occur in more physiological conditions, stimulations were performed in the absence of blockers and spikes were recorded using the cell-attached configuration to preserve intracellular medium. Stimulation of PP generated spikes with high temporal precision (mean SD = 1.4 ± 0.3 ms, n = 4; Fig. 6C). However, when combined PI-EPSP stimulations were applied (ISI 20–50 ms; mean ISI = 30 ± 4 ms, n = 4, see Methods) the temporal precision of PP-EPSP–spike coupling was greatly reduced (mean SD = 3.3 ± 0.3 ms, n = 4; P < 0.05; Fig. 6C). This effect was due to INaP activation because it was reversed in the presence of TTX 10 nM (mean SD = 1.3 ± 0.3 ms; n = 3; P < 0.01; Fig. 6C).

All in all, these experiments show that, in DGCs from epileptic rats, the specific interplay between aberrant PI-EPSPKA and INaP tune PP inputs to fire with low spike timing precision during synaptic integration.

Discussion

We report a major decrease in the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats when compared with controls during single-spike mode discharge. We directly link this phenomenon to the generation of slow EPSPKA by recurrent mossy fibers that, unlike EPSPAMPA, generate long-lasting plateaus and jittered spikes through the activation of persistent sodium current (INaP). Aberrant EPSPKA also tune PP inputs to fire with a low temporal precision through INaP activation. Therefore, aberrant KAR-operated mossy fiber synapses heavily impact the temporal precision of input-output operation of DGCs notably at neocortical synapses in the dentate gyrus of epileptic rats.

KAR-Operated Mossy Fibers Synapses Reduce Temporal Fidelity of EPSP–Spike Coupling in DGCs

Mossy fibers sprout in human patients and animal models of TLE and form novel aberrant synapses onto dentate granule neurons (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Represa et al. 1987; Sutula et al. 1989; Isokawa et al. 1993; Mello et al. 1993; Franck et al. 1995; Okazaki et al. 1995; Buckmaster and Dudek 1999). These in turn augment the excitatory drive and favor the generation of epileptiform activities (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Wuarin and Dudek 1996; Patrylo and Dudek 1998; Hardison et al. 2000; Gabriel et al. 2004; Morgan and Soltesz 2008). This aberrant excitatory circuit between DGCs generates slow synaptic events mediated by KARs that are not present in controls (Epsztein et al. 2005; present paper). Thus, the nature of excitatory synaptic transmission is changed in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats. In addition to synaptic rewiring, voltage-gated currents (including IA, Ih, ICa,T, INaP) can be modified in epileptic neurons (Chen et al. 2001; Agrawal et al. 2003; Bernard et al. 2004; Shah et al. 2004; Vreugdenhil et al. 2004; Yaari et al. 2007; Beck and Yaari 2008). Altogether these alterations can strongly modify the input–output properties of epileptic neurons converting the single-spike mode discharge, usually observed in controls, into bursting activity (Lynch et al. 2000; Beck and Yaari 2008). We now show that recurrent mossy fibers not only favor epileptiform activities (Tauck and Nadler 1985; Wuarin and Dudek 1996; Nadler 2003) but also affects DGC function beyond seizures by reducing the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling during single-spike mode discharge. These changes in EPSP–spike latency and spike timing precision were not due to modifications of intrinsic membrane properties but rather to the slow kinetics of EPSPKA when compared with EPSPAMPA (Castillo et al. 1997; Frerking et al. 1998; Kidd and Isaac 1999; Cossart et al. 2002; Epsztein et al. 2005; Goldin et al. 2007; Barberis et al. 2008). Our experiments revealed that the presence of slow EPSPKA is both necessary and sufficient to decrease the temporal fidelity of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats, because 1) pharmacologically isolated EPSPKA specifically generate spikes with poor temporal precision, in contrast to fast EPSPAMPA that trigger time-locked spikes both in DGCs from control and epileptic rats; 2) blockade of EPSPKA completely restores the high temporal fidelity of EPSP–spike coupling and the fast kinetics of EPSPs in DGCs from epileptic rats; 3) generation of simulated EPSPs with as slow kinetics as EPSPKA is sufficient to introduce a low spike timing precision in DGCs from control rats as observed in DGCs from epileptic rats. Furthermore, we showed that NMDARs do not contribute to the decreased temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from epileptic rats. This is in line with the small contribution of NMDARs in synaptic transmission at recurrent mossy fibers synapses in chronic epileptic rats (Molnar and Nadler 1999; Lynch et al. 2000).

Therefore postsynaptic KARs, but not AMPARs or NMDARs, reduce the temporal fidelity of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats during single-spike mode discharge.

INaP Selectively Amplifies Slow EPSPKA

Previous studies have reported that the activation by EPSPs of voltage-gated conductances near threshold, like sodium persistent or potassium currents, can shape EPSP time course and regulate spike timing precision (Fricker and Miles 2000; Vervaeke et al. 2006). Activation of voltage-dependent potassium currents favors temporal fidelity of EPSP–spike coupling (Fricker and Miles 2000; Axmacher and Miles 2004), whereas activation of persistent sodium current prolongs the time course of synaptic events (Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Schwindt and Crill 1995; Andreasen and Lambert 1999), leading to imprecise spiking (Fricker and Miles 2000; Vervaeke et al. 2006). Therefore, interaction of EPSPs with intrinsic conductances plays a central role in the modulation of the output mode of neurons. Here we found that in control DGCs, the time course of EPSPs is not shaped by intrinsic conductance activation because there is no voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPAMPA. In contrast, in DGCs from epileptic rats, we observed that EPSPKA, but not EPSPAMPA, are selectively amplified near threshold through INaP activation leading to long-lasting plateau potentials associated with poor spike timing precision. Indeed, application of drugs that have been shown to preferentially block INaP phenytoin (Kuo and Bean 1994; Segal and Douglas 1997; Lampl et al. 1998; Fricker and Miles 2000; Yue et al. 2005) or TTX at low nanomolar concentrations (Hammarstrom and Gage 1998; Del Negro et al. 2005; Yue et al. 2005; Kang et al. 2007; Koizumi and Smith 2008) prevents EPSPKA voltage-dependent amplification and significantly increased spike timing precision in DGCs from epileptic rats. Alteration of low threshold T-type Ca2+ conductances has been reported in DGCs from chronic epileptic rats and human patients (Beck et al. 1998). A primary involvement of this conductance is however unlikely here given that T-type Ca2+ currents are mostly inactivated at depolarized membrane potentials where EPSPs are evoked. Furthermore, INaP blockers were sufficient to restore a high spike timing precision in DGCs from epileptic rats. The proximal location of recurrent mossy fiber synapses (Represa et al. 1993; Okazaki et al. 1995) may facilitate the activation of INaP by aberrant EPSPKA because this current is predominantly found in the perisomatic region or the proximal axon (Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Yue et al. 2005; Astman et al. 2006; Beck and Yaari 2008). The specific voltage-dependent amplification of EPSPKA but not EPSPAMPA is however puzzling because these events are both generated at the same dendritic site (in the inner molecular layer) in the same cell type. Thus the difference would not result from a preferential location-dependent activation of INaP or a differential involvement of voltage-dependent potassium currents as observed between pyramidal cells and interneurons in the CA1 area of the control hippocampus (Fricker and Miles 2000). Furthermore, potassium currents do not critically shape the kinetics of small EPSPs at near threshold potentials (Axmacher and Miles 2004). Our results rather suggest a role for EPSP kinetics in the specific activation of INaP. Experiments using simulated EPSPs (generated through somatic current injection) demonstrate that the slow shape of EPSPKA, but not the fast one of EPSPAMPA, is sufficient to activate INaP in control DGCs leading to long-lasting plateaus and jittered spikes. Interestingly, in other cell types as pyramidal neurons, EPSPAMPA activate INaP and are amplified at depolarized potentials (Stuart and Sakmann 1995; Schwindt and Crill 1995; Andreasen and Lambert 1999; Fricker and Miles 2000; Axmacher and Miles 2004), leading to a poor temporal precision. However, in these cell types EPSPAMPA have a much slower kinetics than EPSPAMPA recorded in DGCs. Plasticity of intrinsic neuronal properties have been reported in various CNS disorders (Beck and Yaari 2008), thus an alternative possibility to explain jittered spikes in DGCs from epileptic rats is that INaP is also chronically modified as reported for neocortical and subicular neurons in models and temporal lobe epileptic patients (Agrawal et al. 2003; Vreugdenhil et al. 2004). However, we did not observe a change of INaP I/V curve in DGCs from epileptic rats as compared with controls. Accordingly, simulated EPSPKA could also activate INaP and lead to jittered spike in control DGCs. Thus, alteration of the spike timing precision in DGCs from epileptic rats is not primarily due to an up regulation of INaP.

Spiking often occurs through synaptic integration of different inputs (Magee 2000). The frequency of ongoing excitatory synaptic events is strongly increased in DGCs from epileptic rats (Wuarin and Dudek 2001; Epsztein et al. 2005) and EPSPKA represent half of the spontaneous glutamatergic synaptic transmission in these cells (Epsztein et al. 2005). One important question was thus to determine whether INaP activated by aberrant EPSPKA could also disrupt the temporal precision of PP input during synaptic integration. A previous study, using the kindling model of TLE, reported a change from single-spike mode to burst firing mode of DGCs in response to strong stimulations of PP (Lynch et al. 2000). We observed that DGCs from epileptic rats still discharge in single-spike mode with a high temporal precision in response to low stimulation intensities. However the temporal precision of the PP-EPSP is strongly reduced during summation with EPSPKA. We show that this results from the interplay between PP-EPSP and INaP activated by EPSPKA. Indeed, 1) the temporal precision of PP-EPSP is not affected by PI when INaP is blocked; 2) the temporal precision is not affected when PP-EPSP is preceded by PI-EPSPAMPA that do not activate INaP in DGCs from control and epileptic rats, and 3) activation of INaP by simEPSPKA is sufficient to alter spike timing precision of the PP inputs in DGCs from control rats.

All in all we show that selective EPSPKA amplification via INaP activation shifts EPSP–spike coupling from high to low temporal precision in DGCs from epileptic rats.

Physiological Consequences of Reduced Spike Timing Precision in DGCs from Epileptic Rats

Here, we report a major alteration of the temporal precision of EPSP–spike coupling in DGCs of epileptic rats. This major change has been confirmed in normal ACSF with evoked and spontaneous EPSPs and in a noninvasive condition using the loose-patch configuration. In this study we used EPSPs of small amplitude matching the small amplitude of spontaneous EPSPs recorded in vivo (Waters and Helmchen 2004). In DGCs, the resting membrane potential is relatively far from the spike threshold (present study; Lynch et al. 2000; Epsztein et al. 2005). What are the conditions bringing the membrane potential at near threshold potential allowing small spontaneous EPSPs to generate spiking? In vivo, the membrane potential of DGCs spontaneously fluctuates between a hyperpolarized state (down state) and a depolarized state (up-state) (Hahn et al. 2007). Interestingly, in a few cases where we observed spontaneous up-down state-like behavior of the membrane potential, in DGCs from epileptic rats, EPSPKA evoked during the up-state could generate long-lasting plateau associated with late spikes. Depolarization of the membrane potential also occurs during place field traversal in freely moving rats (Lee et al. 2008). Additional work is needed to clarify the physiological conditions that facilitate the interplay between synapse-driven and voltage-gated currents leading to imprecise spiking in DGCs from epileptic rats.

The ability to generate action potentials with high temporal fidelity in response to EPSPs is an essential feature of adult neurons in the normal brain (Konig et al. 1996). Spike timing precision is instrumental in many physiological processes including processing of sensory information (Abeles 1982; Riehle et al. 1997; Schaefer et al. 2006), generation of behaviorally relevant oscillations (Konig et al. 1996), encoding of spatial information (O'Keefe and Recce 1993; Skaggs et al. 1996; Mehta et al. 2002), and in some forms of synaptic plasticity (Markram et al. 1997; Debanne et al. 1998; Dan and Poo 2006). In pathological conditions, a reduced spike timing reliability correlates with the generation of high frequency oscillations as recently shown in the CA3 area from epileptic rats (Foffani et al. 2007). Beyond seizures, TLE is often associated with pronounced cognitive impairments in epileptic patients (Hermann et al. 1997; Helmstaedter 2002) and animal models (Liu et al. 2003; Lenck-Santini and Holmes 2008; Chauviere et al. 2009). Recently it has been shown that learning deficits are correlated with important alterations of the temporal organization of neuronal firing (i.e., temporal coding of spatial information) in the CA1 area of the hippocampus of epileptic rats (Lenck-Santini and Holmes 2008). In awake rats, DGCs encode spatial information through an increase in instantaneous firing rate (O'Keefe and Dostrovsky 1971; Jung and Mcnaughton 1993) (rate coding) and through the precise timing of action potentials in relation to the ongoing hippocampal theta rhythm (temporal coding) (Skaggs et al. 1996). Recent data suggest that temporal coding in the hippocampus could be inherited from extra-hippocampal structures particularly the entorhinal cortex (Zugaro et al. 2005; Hafting et al. 2008). Thus, the timing errors induced by aberrant mossy fiber sprouting, notably at PP synapses could, together with other changes observed in the epileptic brain (Nadler 2003; Dudek and Sutula 2007), lead to alterations of temporal coding in the dentate gyrus. Future work should determine the impact of decreased spike timing precision in DGCs on coding operation in the hippocampus of chronic epileptic animals.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://www.cercor.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale to J.E. and E.S.; the Ligue Française Contre l'Epilepsie to E.S.; and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR contract Epileptic-Code NT09_566636).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Jorquera and A. Ribas for technical assistance, and Drs L. Aniksztejn, I. Bureau and R. Khazipov for helpful comments on the manuscript. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Abeles M. Role of the cortical neuron: integrator or coincidence detector? Isr J Med Sci. 1982;18(1):83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N, Alonso A, Ragsdale DS. Increased persistent sodium currents in rat entorhinal cortex layer V neurons in a post-status epilepticus model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(12):1601–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.23103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen M, Lambert JD. Somatic amplification of distally generated subthreshold EPSPs in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 1):85–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0085o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astman N, Gutnick MJ, Fleidervish IA. Persistent sodium current in layer 5 neocortical neurons is primarily generated in the proximal axon. J Neurosci. 2006;26(13):3465–3473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4907-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Miles R. Intrinsic cellular currents and the temporal precision of EPSP-action potential coupling in CA1 pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2004;555(Pt 3):713–725. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis A, Sachidhanandam S, Mulle C. GluR6/KA2 kainate receptors mediate slow-deactivating currents. J Neurosci. 2008;28(25):6402–6406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1204-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H, Steffens R, Elger CE, Heinemann U. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32(1-2):321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H, Yaari Y. Plasticity of intrinsic neuronal properties in CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(5):357–369. doi: 10.1038/nrn2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Crepel V, Represa A. Seizures beget seizures in temporal lobe epilepsies: the boomerang effects of newly formed aberrant kainatergic synapses. Epilepsy Curr. 2008;8(3):68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2008.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Anderson A, Becker A, Poolos NP, Beck H, Johnston D. Acquired dendritic channelopathy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Science. 2004;305(5683):532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1097065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaabjerg M, Zimmer J. The dentate mossy fibers: structural organization, development and plasticity. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:85–107. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Dudek FE. In vivo intracellular analysis of granule cell axon reorganization in epileptic rats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(2):712–721. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Theta rhythm of navigation: link between path integration and landmark navigation, episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus. 2005;15(7):827–840. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Kainate receptors mediate a slow postsynaptic current in hippocampal CA3 neurons. Nature. 1997;388(6638):182–186. doi: 10.1038/40645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauviere L, Rafrafi N, Thinus-Blanc C, Bartolomei F, Esclapez M, Bernard C. Early deficits in spatial memory and theta rhythm in experimental temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29(17):5402–5410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4699-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Aradi I, Thon N, Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Baram TZ, Soltesz I. Persistently modified h-channels after complex febrile seizures convert the seizure-induced enhancement of inhibition to hyperexcitability. Nat Med. 2001;7(3):331–337. doi: 10.1038/85480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart R, Epsztein J, Tyzio R, Becq H, Hirsch J, BenAri Y, Crepel V. Quantal release of glutamate generates pure kainate and mixed AMPA/kainate EPSCs in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2002;35(1):147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA, Carlson GC. Functional regulation of the dentate gyrus by GABA-mediated inhibition. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163C:235–812. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crill WE. Persistent sodium current in mammalian central neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo MM. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(3):1033–1048. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Bannister NV, Isaac JT. Rapid, activity-dependent plasticity in timing precision in neonatal barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26(16):4178–4187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0150-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Long-term synaptic plasticity between pairs of individual CA3 pyramidal cells in rat hippocampal slice cultures. J Physiol. 1998;507(Pt 1):237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.237bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Morgado-Valle C, Hayes JA, Mackay DD, Pace RW, Crowder EA, Feldman JL. Sodium and calcium current-mediated pacemaker neurons and respiratory rhythm generation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(2):446–453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2237-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Kainate receptors mediate synaptic transmission between cones and “off” bipolar cells in a mammalian retina. Nature. 1999;397(6715):157–160. doi: 10.1038/16462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek FE, Sutula TP. Epileptogenesis in the dentate gyrus: a critical perspective. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:755–773. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epsztein J, Represa A, Jorquera I, Ben-Ari Y, Crepel V. Recurrent mossy fibers establish aberrant kainate receptor-operated synapses on granule cells from epileptic rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25(36):8229–8239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1469-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foffani G, Uzcategui YG, Gal B, Menendez de la PL. Reduced spike-timing reliability correlates with the emergence of fast ripples in the rat epileptic hippocampus. Neuron. 2007;55(6):930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck JE, Pokorny J, Kunkel DD, Schwartzkroin PA. Physiological and Morphologic characteristics of granule cell circuitry in human epileptic hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1995;36(6):543–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerking M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Synaptic activation of kainate receptors on hippocampal interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(6):479–486. doi: 10.1038/2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke RA, Prince DA. Electrophysiology of dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51(2):195–209. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker D, Miles R. EPSP amplification and the precision of spike timing in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;28(2):559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Nikolic D, Singer W. The gamma cycle. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(7):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabernet L, Jadhav SP, Feldman DE, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;48(2):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Njunting M, Pomper JK, Merschhemke M, Sanabria ER, Eilers A, Kivi A, Zeller M, Meencke HJ, Cavalheiro EA, et al. Stimulus and potassium-induced epileptiform activity in the human dentate gyrus from patients with and without hippocampal sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24(46):10416–10430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2074-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin M, Epsztein J, Jorquera I, Represa A, Ben-Ari Y, Crepel V, Cossart R. Synaptic kainate receptors tune oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons to operate at theta frequency. J Neurosci. 2007;27(36):9560–9572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1237-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T, Fyhn M, Bonnevie T, Moser MB, Moser EI. Hippocampus-independent phase precession in entorhinal grid cells. Nature. 2008;453(7199):1248–1252. doi: 10.1038/nature06957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TT, Sakmann B, Mehta MR. Differential responses of hippocampal subfields to cortical up-down states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):5169–5174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700222104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom AK, Gage PW. Inhibition of oxidative metabolism increases persistent sodium current in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 1998;510(Pt 3):735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.735bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison JL, Okazaki MM, Nadler JV. Modest increase in extracellular potassium unmasks effect of recurrent mossy fiber growth. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84(5):2380–2389. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser M, Major G, Stuart GJ. Differential shunting of EPSPs by action potentials. Science. 2001;291(5501):138–141. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C. Effects of chronic epilepsy on declarative memory systems. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:439–453. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Schoenfeld J, Davies K. Neuropsychological characteristics of the syndrome of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(4):369–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160019010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isokawa M, Levesque MF, Babb TL, Engel J. Single Mossy fiber axonal systems of human dentate granule cells studied in hippocampal slices from patients with temporal-lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 1993;13(4):1511–1522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MW, Mcnaughton BL. Spatial selectivity of unit activity in the hippocampal granular layer. Hippocampus. 1993;3(2):165–182. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Saito M, Sato H, Toyoda H, Maeda Y, Hirai T, Bae YC. Involvement of persistent Na+ current in spike initiation in primary sensory neurons of the rat mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97(3):2385–2393. doi: 10.1152/jn.01191.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd FL, Isaac JTR. Developmental and activity-dependent regulation of kainate receptors at thalamocortical synapses. Nature. 1999;400(6744):569–573. doi: 10.1038/23040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi H, Smith JC. Persistent Na+ and K+-dominated leak currents contribute to respiratory rhythm generation in the pre-Botzinger complex in vitro. J Neurosci. 2008;28(7):1773–1785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3916-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Stuart GJ. Is action potential threshold lowest in the axon? Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(11):1253–1255. doi: 10.1038/nn.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig P, Engel AK, Singer W. Integrator or coincidence detector? The role of the cortical neuron revisited. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(4):130–137. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Bean BP. Na+ channels must deactivate to recover from inactivation. Neuron. 1994;12(4):819–829. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampl I, Schwindt P, Crill W. Reduction of cortical pyramidal neuron excitability by the action of phenytoin on persistent Na+ current. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(1):228–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AK, Epsztein J, Brecht M. Whole-cell recordings of hippocampal CA1 place cell activity in freely moving rats. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2008 690.22. [Google Scholar]