Abstract

Telomerase contributes to chromosome end replication by synthesizing repeats of telomeric DNA, and the telomeric DNA-binding proteins protection of telomeres (POT1) and TPP1 synergistically increase its repeat addition processivity. To understand the mechanism of increased processivity, we measured the effect of POT1–TPP1 on individual steps in the telomerase reaction cycle. Under conditions where telomerase was actively synthesizing DNA, POT1–TPP1 bound to the primer decreased primer dissociation rate. In addition, POT1–TPP1 increased the translocation efficiency. A template-mutant telomerase that synthesizes DNA that cannot be bound by POT1–TPP1 exhibited increased processivity only when the primer contained at least one POT1–TPP1-binding site, so a single POT1–TPP1–DNA interaction is necessary and sufficient for stimulating processivity. The POT1–TPP1 effect is specific, as another single-stranded DNA-binding protein, gp32, cannot substitute. POT1–TPP1 increased processivity even when substoichiometric relative to the DNA, providing evidence for a recruitment function. These results support a model in which POT1–TPP1 enhances telomerase processivity in a manner markedly different from the sliding clamps used by DNA polymerases.

Keywords: POT1, processivity, telomerase, TPP1, translocation

Introduction

Telomerase is a specialized reverse transcriptase comprised of two core subunits (Greider and Blackburn, 1989; Lingner et al, 1997). In humans, the reverse transcriptase subunit is known as hTERT, and the RNA subunit as hTR. By reverse transcribing its RNA template, telomerase extends the 3′ ends of chromosomes with repeats of DNA (Figure 1A) (Collins, 2008). Most biochemical studies of the telomerase enzyme have used purified single-stranded DNA primers. In vivo, however, the substrate for telomerase is much more complex as telomere proteins including protection of telomeres 1 (POT1) and TPP1 (previously called TINT1, PTOP and PIP1) bind to the telomeric DNA repeats, capping human chromosome ends (Baumann and Cech, 2001; Ye et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004b; Palm and de Lange, 2008).

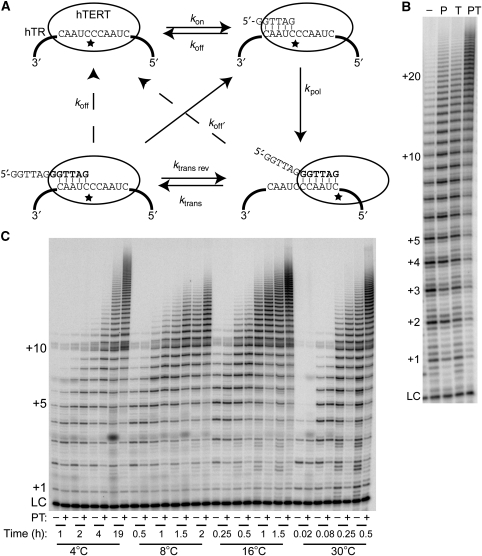

Figure 1.

POT1–TPP1 increases the processivity of telomerase. (A) Telomerase catalytic cycle. Rate constants kon and koff represent the association and dissociation of a DNA primer substrate with telomerase. Once the primer has been extended, its dissociation rate constant is koff′. Rate constant kpol is a composite rate constant, which is determined by the rate-limiting step of DNA polymerization. The translocation step is defined by ktrans and the corresponding reverse rate constant. The star represents the active site in TERT; both the DNA and the RNA must move relative to the active site during translocation. Telomerase maintains a more-or-less constant number of base pairs during extension (Forstemann and Lingner, 2005; Hammond and Cech, 1998). (B) Addition of POT1 and TPP1 to primer A5 (TTAGGGTTAGCGTTAGGG) increases repeat addition processivity of telomerase overexpressed in human embryonic kidney cells. This primer was chosen because the single-C substitution positions POT1–TPP1 on the 5′ end (Wang et al, 2007). Reactions were extended for 30 min at 30°C with telomerase extract alone, or with the addition of 1 μM purified POT1 (P), TPP1 (T), or both POT1 and TPP1 (PT); primer at 500 nM. LC, DNA loading control. Numbers on left, number of telomeric repeats added to the primer. (C) POT1–TPP1 increases the processivity of telomerase at various temperatures. Primer 18GTT (250 nM), which has the completely telomeric sequence (AGGGTT)3, was extended either alone or in the presence of POT1–TPP1 (500 nM) at 4, 8, 16 and 30°C. At each temperature, four time points were taken. The time points at 30°C are more accurately 1, 5, 15 and 30 min. LC, DNA loading control. Numbers on left, number of telomeric repeats added to the primer.

In human cells, POT1 and TPP1 are found within the shelterin complex, which also contains the double-stranded telomeric DNA-binding proteins telomeric-repeat-binding factors 1 and 2 (TRF1 and TRF2) (de Lange, 2005). Another shelterin component, TRF1-interacting nuclear protein 2 (TIN2), bridges the single-stranded and double-stranded DNA-binding proteins (Kim et al, 1999; Ye et al, 2004). POT1 and TPP1 are present at levels of 50–100 copies per telomere and 10-fold less than their binding partner, TIN2 (Takai et al, 2010). Thus, these telomere proteins appear to exist in various subcomplexes as well as in the six-protein shelterin complex (Liu et al, 2004a; de Lange, 2005).

POT1 has an important function in telomere end protection and determines the sequence at the 5′ end of chromosomal DNA (Hockemeyer et al, 2005). RNAi knockdown of either POT1 or TPP1 gives phenotypes of telomere lengthening and chromosomal instability (Houghtaling et al, 2004; Veldman et al, 2004; Ye et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004b; Kelleher et al, 2005). This supports the prevailing model in which POT1 and TPP1 regulate telomerase access to the chromosome end, protecting the telomere from DNA damage and from eliciting a DNA-damage response. However, knockdown of TPP1 inhibits recruitment of POT1 to telomeres, so it is challenging to uncover individual functions for the two proteins in vivo (Ye et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004b).

Characterization of POT1 and TPP1 in vitro further defines possible functions for each in vivo. POT1 binds to ssDNA with high affinity and sequence specificity (Lei et al, 2004; Loayza et al, 2004; Kelleher et al, 2005). Although TPP1 itself does not bind DNA, addition of TPP1 increases the affinity of POT1 for DNA by 10-fold, yet does not change the location of the protein on its binding site (Wang et al, 2007; Xin et al, 2007). X-ray crystal structures of domains of POT1 and TPP1 revealed that both proteins contain oligonucleotide-binding folds (OB-folds) (Lei et al, 2004; Wang et al, 2007). It is thought that POT1 is the structural homolog of Oxytricha nova TEBPα and TPP1 is the structural homolog of TEBPβ. Similar to the O. nova TEBPα and β complex (Horvath et al, 1998), POT1 and TPP1 interact to form a heterodimer that binds DNA (Wang et al, 2007; Xin et al, 2007).

Addition of multiple repeats of a short DNA sequence, such as TTAGGG in humans, is the property that most distinguishes telomerase from other reverse transcriptases and DNA polymerases (Lue, 2004). Multiple repeats can be added following a single primer-binding event (Greider, 1991), a process known as repeat addition processivity (RAP). When POT1–TPP1 is bound to a primer, RAP is substantially increased, which might be explained if POT1–TPP1 acted as a fixed clamp or a sliding clamp between the telomeric DNA and telomerase (Wang et al, 2007). After all, sliding clamps provided by PCNA or β subunit are famous for providing enormous processivity with DNA polymerase (Kuriyan and O'Donnell, 1993).

Here, we report an initial mechanistic analysis of the effect of POT1–TPP1 on telomerase processivity. We find that a single POT1–TPP1-binding site on a primer is sufficient for enhanced processivity, thereby disfavouring the sliding clamp model. Nevertheless, POT1–TPP1 bound to the primer does substantially reduce primer dissociation from telomerase during the catalytic cycle, and it also enhances the rate and efficiency of template-primer translocation (Figure 1A), the step that distinguishes telomerase from other polymerases. These findings suggest how interactions between POT1–TPP1 and telomerase enhance enzyme processivity. The increase in processivity is enough that only one or two rounds of telomerase binding and extension should be sufficient to account for the ∼50 nt of synthesis seen at individual chromosome ends in a single cell cycle in cultured human cancer cells (Zhao et al, 2009).

Results

POT1–TPP1 increases the processivity of telomerase

Earlier, POT1–TPP1 was shown to increase the processivity of telomerase reconstituted in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRLs) (Wang et al, 2007). Telomerase overexpressed in human embryonic kidney cells (Cristofari and Lingner, 2006) is more processive than telomerase reconstituted in RRLs. As this super-telomerase extract was used in all experiments described herein, we first tested the effect of purified POT1–TPP1 on RAP in this system (Supplementary Figure S1). Super-telomerase gives the typical six-nucleotide ladder of primer extension products characteristic of human telomerase; this pattern was only slightly affected by addition of POT1 or TPP1 individually but was shifted towards higher products on addition of both POT1 and TPP1 (Figure 1B). Under a variety of conditions in four experiments, the addition of POT1–TPP1 caused processivity to increase by a factor of 2.7±0.6 (quantitation method is described in Materials and methods). This means that almost half the chains are elongated by eight repeats (48 nt) before dissociation in the presence of POT1–TPP1, whereas <10% of the chains reach this length without POT1–TPP1.

Similar increases in processivity were seen with seven other primers designed to position POT1–TPP1 at different sites on the DNA (Supplementary Figure S1B and C). As some experiments described below required lower temperature, we also tested the temperature dependence of the POT1–TPP1 effect. As shown in Figure 1C, although the rate of telomerase extension is highly temperature dependent, processivity is enhanced by POT1–TPP1 at all temperatures in the range of 4°–30°C.

The vast excess of unextended primer in these reactions should effectively compete with dissociated reaction products for rebinding to telomerase; thus, the extended ladders of products suggest processive extension following a single binding event, not distributive extension (release, rebinding and re-extension of the same DNA) (Greider, 1991; Bryan et al, 2000). Processive extension was confirmed by two tests (Supplementary Figure S2). First, when the DNA primer was increased to concentrations far over the apparent Km (10 nM), the ladder of extension products did not decrease (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). If extension were distributive, then apparent processivity would decrease because of competition by unextended primer. Second, a pulse-chase experiment clearly showed that long products resulted from the further extension of shorter precursors rather than dissociation and rebinding (Supplementary Figure S2C and D).

POT1–TPP1 decreases primer dissociation, increases translocation

POT1–TPP1 could increase primer processivity by affecting any of the several steps in the catalytic cycle (Figure 1A). First, POT1–TPP1 could decrease koff, the dissociation rate constant of the primer. We developed a new pulse-chase assay for measuring primer dissociation from active telomerase. Primer and enzyme were preincubated, and then at time zero a large excess of chase oligonucleotide A5P was added; because A5P is 3′-phosphorylated, it cannot be extended (Figure 2A, lane 3). At various times thereafter, a short extension in the presence of radiolabelled nucleotides revealed how much of the original primer was still bound to enzyme. The A5P chase has the sequence TTAGGGTTAGCGTTAGGGp, where the substitution of the single non-telomeric C constrains POT1–TPP1 to bind at the 10 nucleotides at the 5′ end leaving a telomeric 3′-tail that binds to the template RNA of telomerase (Wang et al, 2007). A5P is a competitive inhibitor of telomerase (Ki=16 nM, Supplementary Figure S3); it neither interferes with nor promotes the extension of an already-bound primer even at concentrations of 4 μM, which exceed those used in the experiments (Supplementary Figure S4); and it can be completely bound by 600 nM POT1–TPP1 (Supplementary Figure S5). These properties made it suitable for use as a ‘chase primer.' In experiments involving POT1–TPP1, we added enough POT1–TPP1 along with the chase primer such that the chase primer would not serve as a sink for POT1–TPP1 that was bound to the extendable primer.

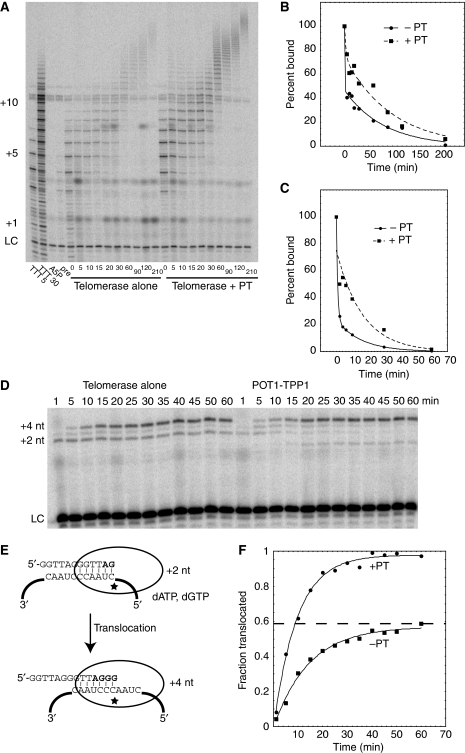

Figure 2.

POT1–TPP1 decreases the dissociation rate of extending telomerase enzyme and increases the translocation rate. (A) Extending primer dissociation rate assay. Telomerase and primer TTTA5 (50 nM) (TTTTTAGGGTTAGCGTTAGGG) were incubated either alone or with POT1–TPP1 (‘+PT,' 100 nM) for 30 min at room temperature. The reactions were then moved to 16°C for 5 min to chill. At time t=−5 min, the dNTPs were added and the reactions were extended for 5 min in the absence of radiolabelled dGTP. At time t=0, chase A5P (TTAGGGTTAGCGTTAGGGp) (2 μM) either alone or with 1.9 μM POT1–TPP1 was added to the reaction. At each time point, 18 μl of the reaction mix were added to 2 μl of radiolabelled dGTP and labelled at 16°C for 5 min. In the first lanes are control reactions: TTTA5 labelled for 5 min, and 30 min, then A5P and premix (A5P+TTTA5) labelled for 5 min. LC, DNA loading control. Numbers on left, number of telomeric repeats added to the primer. (B) Quantitation of panel (A). The total counts (TC) of each lane were measured. Percent bound was calculated as [TC(t=n)/TC(t=0)] × 100 and plotted versus time. The data were fit to a double exponential with a fast phase and a slow phase. Telomerase alone in solid line, and +PT in dashed line. (C) Quantitation of primer off rate from extending telomerase, as in panel (B) but data at 30°C. The data from two gels were averaged together and fit to a double exponential with a fast phase and a slow phase. (D) POT1–TPP1 facilitates translocation step. During the first round of polymerization using oligo 26GTT (100 nM) (TTATTATTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGGTT), two nucleotides are added, AG (+2 nt). Telomerase then translocates, adds two more nucleotides, GG (+4 nt), and stops because dT was omitted from the reaction. To slow the enzyme enough to measure rate, [Mg2+]=0.1 mM and the extension temperature was 4°C. Both POT1 and TPP1 were at 1.5 μM, and 1 μM A5P chase was added at time t=0 to prevent telomerase re-initiation. (E) Model of translocation assay. The first round of addition results in the addition of +2 nt. Telomerase translocates and adds an additional 2 nucleotides (+4) and then stops because dT is absent. (F) POT1–TPP1 increases the efficiency of translocation. The percent translocated was calculated by taking the counts in the +4 and +3 bands divided by the total counts, multiplied by 100%. The product migrating at +0, which is due to a small amount of nuclease activity in some preparations of TPP1, represents <5% of total product, and our conclusions are not affected by whether quantitation includes or excludes the +0 band. Each data set was fit with the equation y=A(1−e(−kt)) where A is the horizontal limit representing the maximum efficiency (0.99 with and 0.57 without POT1–TPP1). The translocation rate is higher in the presence of POT1–TPP1, as determined from the initial slope of the line; this higher rate is in part due to a higher rate constant (k=0.10/min and 0.07/min in the presence and absence of POT1–TPP1, respectively), and in part due to the fact that the reaction in the absence of POT1–TPP1 has a lower maximum efficiency.

Having validated the system, we first measured the rate of dissociation of a telomeric 18-mer from telomerase in its resting state (no nucleotides present during the dissociation time-course.) In the absence of POT1–TPP1, koff=0.012/min, in agreement with an earlier result (Wallweber et al, 2003). Unexpectedly, in the presence of a saturating quantity of POT1–TPP1, the primer dissociation rate was unchanged (Supplementary Figure S6; three experiments gave equivalent results.) We next devised a protocol for measuring the rate of dissociation of primer from telomerase that was actively synthesizing DNA during the chase period (nucleotides were present, and the DNA undergoing dissociation had a range of sizes rather than a single size). Under these conditions, the free primer dissociated much more rapidly, so we reduced the temperature to 16°C to facilitate the measurements. With actively cycling enzyme, POT1–TPP1 clearly slowed the dissociation of the ensemble of extending primers (Figure 2A). Although the data could not be fit to a single first-order dissociation constant, the time required for half-dissociation was increased at least four-fold at 16° or 30°C (Figure 2B and C). This dissociation could be occurring at one or several of the steps indicated in Figure 1A, which (coupled with the range of product lengths) may account for the complex kinetics. The decrease in koff with POT1–TPP1 was confirmed with recombinant human telomerase reconstituted in RRLs and immunopurified (AJ Zaug and TR Cech, unpublished data).

We next tested whether POT1–TPP1 affected the translocation step, in which the RNA template is repositioned relative to the active site in TERT and the DNA binds to a new position on the template (Figure 1A). We developed an assay to measure a single round of translocation at 4°C, where the kinetics are slow enough to follow. When dTTP is omitted, the primer 26GTT gives mainly two products, a +2 nt product from the first round of extension and a +4 nt product from the second round (Figure 2D and E). As only one translocation event can occur, the ratio of +4 over the total counts reflects the fraction of telomerase that has translocated. On addition of POT1–TPP1, the efficiency of translocation increased from 57 to 99% (Figure 2F). Stalled complexes and dissociated complexes could contribute to the untranslocated population seen in the absence of POT1–TPP1. The facilitation of the translocation step by POT1–TPP1 could be a consequence of the slower primer dissociation documented in Figure 2A–C, or it could be an independent contribution.

Finally, measuring the rate of incorporation of dG in the experiment of Figure 2D, we observed no increase kpol in the presence of POT1–TPP1. In any case, because polymerization is a fast step relative to translocation, kpol does not affect the overall rate of transit through the catalytic cycle or the processivity.

POT1–TPP1 enhancement of processivity requires one binding site on the DNA

POT1–TPP1 might enhance processivity by binding directly to either the TERT protein or TR RNA component of telomerase, or it might instead need to be bound to the DNA. To test the necessity of POT1–TPP1–DNA binding, several mutant template telomerase RNAs (Rivera and Blackburn, 2004) were designed to synthesize DNA repeats that cannot be bound by POT1–TPP1. This proved to be difficult, as sets of modest mutations did not completely destroy POT1–TPP1 binding to the DNA, whereas some more extensive mutations did not give much active telomerase when measured with a direct assay. Eventually, we succeeded in expressing telomerase that synthesized the mutated telomeric sequence TTTGGC (Figure 3A). POT1–TPP1 did not bind to this mutant sequence as shown by a native gel shift assay (Figure 3B).

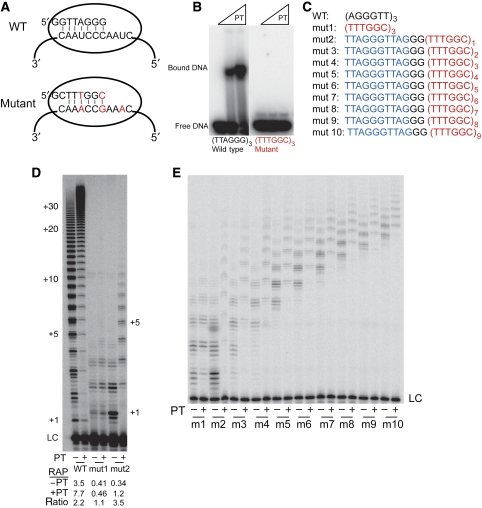

Figure 3.

Mutant telomerase reveals requirement for a single POT1–TPP1-binding site in newly synthesized DNA. (A) Cartoon of wild-type (WT) and mutant telomerase template-primer interactions with point mutations in red. (B) Native gel shift of oligonucleotides (50 nM) with POT1–TPP1 (PT) at 0, 150 and 300 nM. (C) Oligonucleotides used in mutant telomerase activity assay. POT1–TPP1-binding site is in blue, mutant repeats are in red. (D) Activity assay of WT telomerase with WT primer, and mutant telomerase with mut1 and mut2 primers. Telomerase alone or in the presence of 1 μM POT1 and TPP1 (PT) with each primer at 1 μM. For all assays comparing WT telomerase and mutant telomerase, total [dGTP]=5 μM, which gives higher processivity than the conditions of Figures 1 and 2. The RAP was quantitated (units=number of repeats). Ratio, processivity with POT1–TPP1 divided by that without POT1–TPP1. (E) Increasing the distance between the POT1–TPP1 site and the 3′ end. Activity assay of mutant telomerase alone, or in the presence of 1.5 μM POT1 and TPP1 (PT) with each gel purified primer (sequences shown in panel C) at 500 nM. Reaction for 30 min.

The template-mutant telomerase RNA was overexpressed with wild-type TERT in human embryonic kidney cells and the resulting telomerase was tested for activity and processivity on addition of POT1–TPP1. The addition of POT1–TPP1 did not increase the processivity of the mutant telomerase with a completely mutant DNA primer, mut1 (Figure 3C and D). However, one POT1–TPP1-binding site (shown in blue in Figure 3C) at the 5′ end of the mutant primer mut2 was sufficient to allow POT1–TPP1 to increase the processivity of the mutant telomerase. Then, we increased the distance between the 3′ end and the POT1–TPP1-binding site by increasing the number of mutant telomeric repeats in the primer (Figure 3C and E). Surprisingly, POT1–TPP1 increased the processivity of telomerase even when separated from the 3′ end by nine mutant repeats. The single POT1–TPP1-binding site did not need to be at the 5′ end of the primer, but was functional in internal positions as well (primer 72-1 in Supplementary Figures S7 and S8, and additional data not shown). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed that POT1–TPP1 bound to the cognate-binding site on each primer, although faint bands indicated some binding to non-cognate sites as well (see primer 72C in Supplementary Figure S7). Together, these data indicate that while enhanced processivity requires POT1–TPP1 to bind to the DNA, continued binding to the newly synthesized DNA is not required, nor is having the binding site in close proximity to the portion of the primer bound to the template.

Given the result that a POT1–TPP1-binding site nine repeats away from the 3′ end can increase the processivity, we considered the possibility that binding to DNA was the only requirement for POT1–TPP1 to increase processivity. To test this, we added primer A5P saturated with POT1–TPP1 in trans to template-mutant telomerase bound to primer mut1, which has completely mutant sequence. POT1–TPP1 bound to DNA was not able to stimulate processivity in trans (Supplementary Figure S9). If it does have any such ability, then it must require much higher concentrations to drive the reaction than the 1 μM levels that were tested.

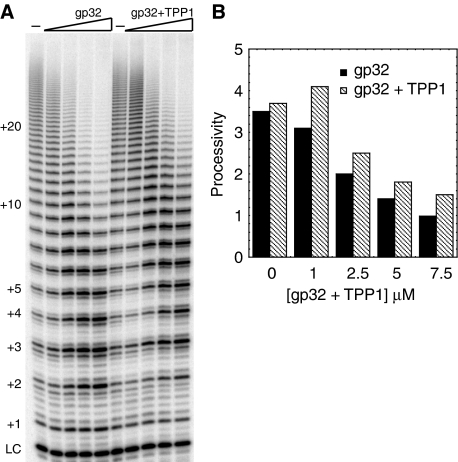

Not every ssDNA-binding protein enhances telomerase action

To determine whether the effects of POT1–TPP1 on telomerase are specific, a non-specific ssDNA-binding protein, gp32, was tested (Figure 4). When excess gp32 was added to telomerase reactions, the processivity and activity of telomerase decreased. The banding pattern on addition of gp32 looked identical to telomerase alone in the lower bands, but the signal decreased for the upper bands at high concentrations of gp32. This suggests that telomerase can initiate in the presence of gp32, but once the elongated DNA is long enough for multiple gp32 molecules to bind cooperatively and coat the DNA, telomerase cannot continue elongation. Then, increasing amounts of TPP1 were added to attempt to recover activity and increase the processivity. Adding TPP1 to gp32 reactions had only a slight effect on telomerase processivity, in contrast to the effect of addition of TPP1 to reactions containing POT1. This indicates that full stimulation of processivity requires a specific interaction between POT1 and its binding partner TPP1, a specific interaction between POT1–TPP1 and telomerase, or both.

Figure 4.

Stimulation of telomerase processivity is specific to POT1–TPP1. (A) A non-specific single-stranded DNA-binding protein, gp32, was added to telomerase activity assays either alone or with TPP1. Concentrations of gp32 and TPP1 were 0, 1, 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM. Primer 18GTT was at 1 μM. Because of the presence of 1 mM EDTA in the gp32 protein, 2 mM MgCl2 was added to both gp32 protein and to mock protein buffer to compensate. Reaction for 30 min. (B) Processivity quantitation of panel (A). The processivity of each lane was calculated and plotted versus the concentration of either gp32 alone (solid bars) or gp32+TPP1 (dashed bars).

Recruitment

If POT1–TPP1 interacts with telomerase, it seemed possible that POT1–TPP1 might be preferentially recruited to DNA molecules that were being extended by telomerase or that POT1–TPP1 might be able to recruit telomerase to the DNA to which it was bound. Recruitment was tested by increasing the concentration of POT1–TPP1 from 1 to 1000 nM while the concentration of primer was held constant at 1000 nM. Between 50 and 100 nM POT1–TPP1, telomerase underwent a transition from normal processivity to increased processivity (Figure 5A). The processivity continued to increase substantially from 100 to 1000 nM POT1–TPP1 (Figure 5B). In all reactions, the concentration of telomerase was limiting, ∼0.2 nM, as determined by northern blot to hTR (data not shown). In independent repetitions of this experiment, the POT1–TPP1 concentration at which increased processivity was observed varied somewhat (20–50 nM), but was always clearly substoichiometric relative to the DNA. The substoichiometric activity cannot be explained by errors in the concentration of POT1, TPP1, or DNA, because the concentration of active POT1–TPP1 relative to DNA was determined by titration (see Materials and methods). Furthermore, the fraction of the primer bound by POT1–TPP1 under telomerase assay conditions was confirmed by a native gel shift assay (data not shown).

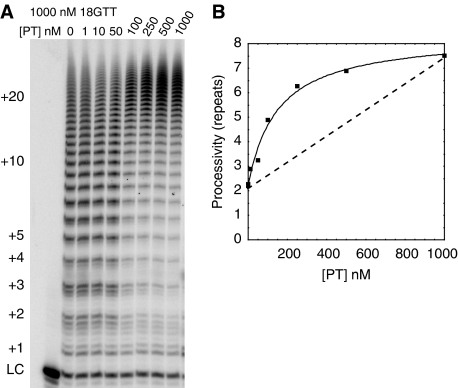

Figure 5.

POT1–TPP1 stimulates processivity at substoichiometric concentrations. (A) Telomerase activity assay. Primer 18GTT was at 1000 nM. POT1 and TPP1 (PT) concentrations were increased from 1 to 1000 nM. Reaction for 30 min. (B) Quantitation of processivity in panel (A). The processivity value at each point in the titration was calculated as described in Materials and methods and plotted versus the concentration of POT1–TPP1. A straight line (dashed) represents the expected processivity values if POT1–TPP1 did not recruit telomerase to an end.

If POT1–TPP1 had no preference for telomerase-bound DNA, then at 100 nM POT1–TPP1, where at most 10% of the DNA was bound, one would expect at most 10% of the telomerase molecules to have increased processivity and 90% of the molecules normal processivity; but this was not observed. A line drawn between the end point processivity values in Figure 5B indicates the processivity expected if POT1–TPP1 had no preference for telomerase-bound DNA. That telomerase had increased processivity under conditions where only a fraction of the DNA was bound further suggests that there is an interaction between POT1–TPP1 and telomerase. This interaction could enable POT1–TPP1 to recruit telomerase to chromosome ends at which it is bound, a model with clear biological relevance. However, our data may instead be explained by POT1–TPP1 being preferentially recruited to DNA that is being elongated by telomerase.

Discussion

POT1 and its heterodimeric partner TPP1 are the only human proteins identified as being dedicated to binding single-stranded telomeric DNA. As single-stranded telomeric DNA at chromosome ends also serves as the primer for telomerase, a fundamental question concerns what happens when telomerase encounters POT1–TPP1-bound telomeric DNA. Instead of simply inhibiting telomerase action, POT1–TPP1 enhances telomerase RAP—its ability to add multiple repeats to a primer following a single binding event (Wang et al, 2007).

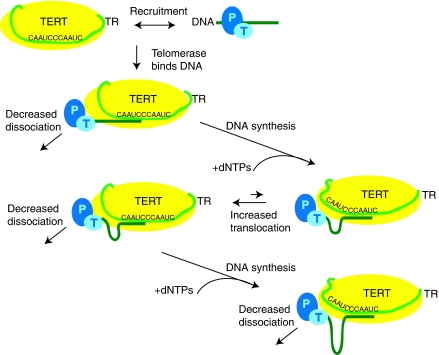

In this work, we investigate the mechanism of this enhanced RAP and report three key findings. First, the binding of POT1–TPP1 to a DNA primer inhibits its dissociation from telomerase during an active polymerization cycle. This by itself promotes transit through the reaction cycle and thereby increases RAP (Figure 1A). Second, POT1–TPP1 increases the efficiency of the translocation step, during which the primer and RNA template are repositioned relative to each other and relative to the catalytic active site of TERT. Improved translocation might be a consequence of slower primer dissociation or, alternatively, it might be an independent contribution of POT1–TPP1. Third, a single POT1–TPP1-binding site on the primer is necessary and sufficient for enhanced RAP; continuous binding of the proteins to the nascent DNA appears to give no additional enhancement.

These mechanistic observations indicate a functional interaction between POT1–TPP1-bound DNA and telomerase that enhances RAP. The proposed interaction is similar to the ‘fixed clamp' model mentioned by Wang et al (2007). However, the word ‘clamp' suggests a very stable interaction, whereas it may be that POT1–TPP1 holds the primer DNA to telomerase more transiently at some key step or steps during the reaction cycle, preventing primer dissociation. In any case, POT1–TPP1 can perform this function even when it remains at a fixed position along the DNA, as evidenced by the experiments with template-mutant telomerase and mutant primers that contain only a single POT1–TPP1-binding site (Figure 3). Our current model is detailed in Figure 6, which also incorporates our evidence that POT1–TPP1 may preferentially recruit telomerase to primers to which it is bound (Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Model of POT1–TPP1 stimulation of processivity. POT1–TPP1 enhances recruitment of primer to telomerase, and telomerase binds the DNA. Telomerase extends the DNA to the end of the RNA template and translocates the RNA relative to the DNA. The translocation step is more efficient and faster in the presence of POT1–TPP1. Throughout the catalytic cycle, the dissociation of telomerase from DNA is decreased in the presence of POT1–TPP1. By both decreasing the dissociation rate and increasing the efficiency and rate of the translocation step, POT1–TPP1 increases the processivity of telomerase. Here, the POT1–TPP1–telomerase interaction is shown as stable binding, but it could also be more transient as long as it prevents primer dissociation during vulnerable steps in the catalytic cycle.

More generally, the sliding clamps used by DNA-dependent DNA polymerases can be compared with the action of POT1–TPP1 with telomerase. In both cases, additional non-polymerase proteins are responsible for processivity. The β clamp in bacteria and PCNA in eukaryotes form protein rings that encircle the double-stranded DNA and bind to the DNA polymerase, greatly enhancing nucleotide-addition processivity. Telomerase is a very different sort of polymerase, in that it needs to add only about 50 nt per telomere per cell cycle (Zhao et al, 2009), compared with >50 000 base pairs per binding event for a chromosomal DNA polymerase (Kornberg and Baker, 1992). On the other hand, to achieve RAP, telomerase must translocate its RNA template and rebind the DNA to a new position on the RNA template, a process that appears to be difficult as judged by the high proportion of products that dissociate or stall after each 6-nt round of synthesis. POT1–TPP1, already bound to the DNA primer, needs only to interact with telomerase to facilitate RAP, and with only 50 nt being synthesized, there would appear to be no need for a sliding clamp that moves along the nascent DNA. Furthermore, single-stranded DNA is extremely flexible relative to stiff double-helical DNA, so a fixed interaction is not expected to inhibit telomerase action. Thus, POT1–TPP1 satisfies telomerase's requirements for RAP, and at the same time it is well suited for chromosome end protection.

POT1–TPP1's ability to decrease primer dissociation and its ability to stimulate RAP when it is substoichiometric relative to the DNA both suggest an interaction between POT1–TPP1 and telomerase. In fact, previously published pull-down experiments provide evidence for a physical interaction (Xin et al, 2007). In that work, the OB-fold of TPP1 was necessary for pulling down telomerase and led the authors to suggest the possibility of recruitment. We now provide functional data in support of recruitment, in that POT1–TPP1 stimulates the processivity of telomerase at substoichiometric concentrations (Figure 5). One simple interpretation is that active telomerase with its nascent DNA product preferentially recruits POT1–TPP1 away from free primers, and another possibility is that DNA-bound POT1–TPP1 could recruit telomerase before initiation. On the telomerase side, mutational analysis has revealed the telomerase essential N-terminal domain of hTERT as being necessary for the enhanced processivity, but other elements of telomerase are required as well (Zaug, Podell and Cech, manuscript in preparation).

This study does not address the initiation of telomeric DNA synthesis, which must involve POT1–TPP1 being displaced from the 3′ end of the primer. This step may be passive: POT1–TPP1 occasionally dissociates from the DNA (its half-life ranges from 3 to 30 min; Wang et al, 2007), and the DNA is then free to be bound by telomerase. Alternatively, with some primers it is possible that telomerase triggers an active hand-off of the primer with displacement of POT1–TPP1. Benkovic and coworkers have proposed a similar mechanism in the DNA polymerase system where the primase hands-off the RNA primer to the polymerase (Nelson et al, 2008). In any case, at least short primers appear to be bound to telomerase as free DNA rather than as a POT1–TPP1–DNA complex, as judged by the unchanged off-rate for dissociation of primer from non-cycling telomerase in the presence of POT1–TPP1 (Supplementary Figure S6).

These biochemical studies reveal fundamental features of POT1–TPP1 enhancement of telomerase action that are currently beyond the ability to test in vivo. For example, RNAi knock-down of either POT1 or TPP1 results in telomere lengthening; however, reduction of TPP1 decreases the localization of POT1 to telomeres (Ye et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004b). Thus, it is not surprising that these uncapped telomeres are promiscuously extended by telomerase, and the in vivo results end up giving little information about the separate functions of POT1 and TPP1 in telomerase regulation. On the basis of the biochemical analysis, POT1 bound to telomeric DNA contributes to capping the chromosome end and inhibits telomerase access. Further addition of TPP1 produces an even more stable chromosome cap, preventing access by nucleases and recombination and repair factors, while at the same time activating telomerase to become more processive.

We do not know whether POT1–TPP1's function in telomerase processivity would be affected by POT1–TPP1 being associated with TIN2, TRF1, TRF2 and RAP1 as part of the shelterin complex. Although a substantial amount of POT1–TPP1 is part of shelterin, subcomplexes containing a subset of the proteins have been observed (de Lange, 2005). Thus, regulation could perhaps occur both at the level of POT1–TPP1 and at the level of the shelterin complex as a whole. In addition, telomerase is regulated at the level of the synthesis of TERT and at the level of nuclear localization, providing a rich array of questions for future research (Cristofari et al, 2007a).

Materials and methods

Telomerase reaction conditions

Unless otherwise stated, telomerase reactions were carried out as 20 μl reactions with: 50 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, 30 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermidine, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 μM 18GTT, 2 μl of super-telomerase extract (∼0.2 nM telomerase), 500 μM dATP, 500 μM dTTP, 2.92 μM unlabelled dGTP and 0.33 μM radiolabelled dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol) at 30°C for 30 min. Mutant telomerase reactions were performed as above with the exception that the dNTPs were as follows: 5 μM dGTP, 500 μM dTTP, 500 μM dCTP and 0.33 μM radiolabelled dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol). Reactions were stopped with 100 μl of 3.6 M ammonium acetate and 20 μg of glycogen, precipitated by addition of 450 μl ethanol and incubated overnight at −80°C. Reactions were then centrifuged for 30 min at 13 000 r.p.m., and the pellets were washed with 70% ethanol and centrifuged again. The dried pellets were then resuspended in 10 μl H2O and 10 μl of formamide loading buffer (95% formamide, 5% H2O, loading dye), heated at 95°C for 10 min, centrifuged for 1 min and loaded onto a 10% acrylamide, 7 M urea, 1 × TBE sequencing gel. Gels were run at 95 W for 1.25 h, and dried.

Quantitation

Gels were quantitated using Imagequant TL. For each dissociation rate assay, the counts for each telomerase band were obtained individually, normalized for the number of radiolabelled guanosines added, normalized against the loading control and then summed over the entire lane for the total lane counts (TLCs). The data were then expressed as a percentage bound by taking (TLC(t=n)/TLC(t=0)) × 100. The percent bound was plotted versus time and fit to an exponential decay curve.

For processivity calculations, each telomerase band was individually quantitated. Then, counts for a band were normalized by dividing by the total number of radiolabelled guanosines added to that extension product. For a band n, the fraction left behind (FLB) was calculated by taking the sum of counts for repeats (1–n) divided by the TLCs. Then ln(1−FLB) was plotted versus repeat number. Each lane was fit with a linear regression equation with slope m. The processivity value equals −0.693/m. Usually the first 2–3 repeats were not included in the fit due to telomerase aborting an unusually high percentage of products in the first few repeats. Some points were omitted from higher POT1–TPP1 generated repeats due to an inability to separate products leading to significant signal overlap from one repeat to the next. The linear portion for each telomerase reaction included at least 10–20 repeats. Typical data are shown in Supplementary Figure S10.

Super-telomerase extract

Telomerase was prepared as described earlier (Cristofari and Lingner, 2006; Cristofari et al, 2007b). The only modification was the addition of 3 μl of an RNase inhibitor to 400 μl CHAPS lysis buffer.

Protein purification

Full-length hPOT1v1 was expressed in baculovirus and purified using GST-affinity purification as described earlier (Lei et al, 2004). For each prep of POT1, the active concentration was determined by DNA-binding titration with a DNA concentration above Kd. Typically, POT1 was determined to be 40–50% active; this includes any systematic error in determining protein concentration as well as the presence of some inactive protein. The figures and text list total protein concentration, with no correction for percent active; note, for example, that the conclusion that POT1–TPP1 enhances processivity at substoichiometric concentrations becomes even stronger when one considers that the active protein concentration is less than the total concentration. TPP1 (amino acids 89–334) was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified using His-tag affinity chromatography as described earlier (Wang et al, 2007). Each preparation of TPP1 was tested for stimulation of telomerase processivity. All preparations were equally active and no changes were made concerning the concentration of protein.

Native gel shift assays

Native gel shift assays were performed as described earlier (Lei et al, 2004). Briefly, POT1 was added to 5′-32P-labelled DNA primers and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol and 1 mM DTT. Reactions were then loaded onto a native 1X TBE 8–20% polyacrylamide gradient gel, run in the cold at 100 V for 1 h and dried.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arthur Zaug, Elaine Podell, Robert Batey, Deborah Wuttke and Kathleen Collins for advice on experiments and insightful discussions. We thank Quentin Vicens, Jayakrishnan Nandakumar and Andrea Berman for comments on the manuscript. Joachim Lingner (ISREC, Lausanne) generously provided super-telomerase extract for pilot experiments, plasmids, cells and detailed protocols for telomerase expression. Richard Karpel (University of Maryland Baltimore County) generously provided purified gp32. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM28039.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Baumann P, Cech TR (2001) Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science 292: 1171–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Goodrich KJ, Cech TR (2000) A mutant of Tetrahymena telomerase reverse transcriptase with increased processivity. J Biol Chem 275: 24199–24207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K (2008) Physiological assembly and activity of human telomerase complexes. Mech Ageing Dev 129: 91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari G, Adolf E, Reichenbach P, Sikora K, Terns RM, Terns MP, Lingner J (2007a) Human telomerase RNA accumulation in Cajal bodies facilitates telomerase recruitment to telomeres and telomere elongation. Mol Cell 27: 882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari G, Lingner J (2006) Telomere length homeostasis requires that telomerase levels are limiting. EMBO J 25: 565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari G, Reichenbach P, Regamey PO, Banfi D, Chambon M, Turcatti G, Lingner J (2007b) Low- to high-throughput analysis of telomerase modulators with Telospot. Nat Methods 4: 851–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T (2005) Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19: 2100–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstemann K, Lingner J (2005) Telomerase limits the extent of base pairing between template RNA and telomeric DNA. EMBO Rep 6: 361–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW (1991) Telomerase is processive. Mol Cell Biol 11: 4572–4580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH (1989) A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337: 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond PW, Cech TR (1998) Euplotes telomerase: evidence for limited base-pairing during primer elongation and dGTP as an effector of translocation. Biochemistry 37: 5162–5172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Sfeir AJ, Shay JW, Wright WE, de Lange T (2005) POT1 protects telomeres from a transient DNA damage response and determines how human chromosomes end. EMBO J 24: 2667–2678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath MP, Schweiker VL, Bevilacqua JM, Ruggles JA, Schultz SC (1998) Crystal structure of the Oxytricha nova telomere end binding protein complexed with single strand DNA. Cell 95: 963–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling BR, Cuttonaro L, Chang W, Smith S (2004) A dynamic molecular link between the telomere length regulator TRF1 and the chromosome end protector TRF2. Curr Biol 14: 1621–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C, Kurth I, Lingner J (2005) Human protection of telomeres 1 (POT1) is a negative regulator of telomerase activity in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 25: 808–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kaminker P, Campisi J (1999) TIN2, a new regulator of telomere length in human cells. Nat Genet 23: 405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A, Baker TA (1992) DNA Replication. New York: W. H. Freeman [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan J, O'Donnell M (1993) Sliding clamps of DNA polymerases. J Mol Biol 234: 915–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Podell ER, Cech TR (2004) Structure of human POT1 bound to telomeric single-stranded DNA provides a model for chromosome end-protection. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 1223–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J, Hughes TR, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech TR (1997) Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science 276: 561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, O'Connor MS, Qin J, Songyang Z (2004a) Telosome, a mammalian telomere-associated complex formed by multiple telomeric proteins. J Biol Chem 279: 51338–51342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Safari A, O'Connor MS, Chan DW, Laegeler A, Qin J, Songyang Z (2004b) PTOP interacts with POT1 and regulates its localization to telomeres. Nat Cell Biol 6: 673–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza D, Parsons H, Donigian J, Hoke K, de Lange T (2004) DNA binding features of human POT1: a nonamer 5′-TAGGGTTAG-3′ minimal binding site, sequence specificity, and internal binding to multimeric sites. J Biol Chem 279: 13241–13248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue NF (2004) Adding to the ends: what makes telomerase processive and how important is it? Bioessays 26: 955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SW, Kumar R, Benkovic SJ (2008) RNA primer handoff in bacteriophage T4 DNA replication: the role of single-stranded DNA-binding protein and polymerase accessory proteins. J Biol Chem 283: 22838–22846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm W, de Lange T (2008) How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet 42: 301–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera MA, Blackburn EH (2004) Processive utilization of the human telomerase template: lack of a requirement for template switching. J Biol Chem 279: 53770–53781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai KK, Hooper SM, Blackwood SL, Gandhi R, de Lange T (2010) In vivo stoichiometry of shelterin components. J Biol Chem (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldman T, Etheridge KT, Counter CM (2004) Loss of hPot1 function leads to telomere instability and a cut-like phenotype. Curr Biol 14: 2264–2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallweber G, Gryaznov S, Pongracz K, Pruzan R (2003) Interaction of human telomerase with its primer substrate. Biochemistry 42: 589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Podell ER, Zaug AJ, Yang Y, Baciu P, Cech TR, Lei M (2007) The POT1-TPP1 telomere complex is a telomerase processivity factor. Nature 445: 506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Liu D, Wan M, Safari A, Kim H, Sun W, O'Connor MS, Songyang Z (2007) TPP1 is a homologue of ciliate TEBP-beta and interacts with POT1 to recruit telomerase. Nature 445: 559–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JZ, Hockemeyer D, Krutchinsky AN, Loayza D, Hooper SM, Chait BT, de Lange T (2004) POT1-interacting protein PIP1: a telomere length regulator that recruits POT1 to the TIN2/TRF1 complex. Genes Dev 18: 1649–1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Sfeir AJ, Zou Y, Buseman CM, Chow TT, Shay JW, Wright WE (2009) Telomere extension occurs at most chromosome ends and is uncoupled from fill-in in human cancer cells. Cell 138: 463–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.