Abstract

Cargo transport by microtubule-based motors is essential for cell organisation and function. The Bicaudal-D (BicD) protein participates in the transport of a subset of cargoes by the minus-end-directed motor dynein, although the full extent of its functions is unclear. In this study, we report that in Drosophila zygotic BicD function is only obligatory in the nervous system. Clathrin heavy chain (Chc), a major constituent of coated pits and vesicles, is the most abundant protein co-precipitated with BicD from head extracts. BicD binds Chc directly and interacts genetically with components of the pathway for clathrin-mediated membrane trafficking. Directed transport and subcellular localisation of Chc is strongly perturbed in BicD mutant presynaptic boutons. Functional assays show that BicD and dynein are essential for the maintenance of normal levels of neurotransmission specifically during high-frequency electrical stimulation and that this is associated with a reduced rate of recycling of internalised synaptic membrane. Our results implicate BicD as a new player in clathrin-associated trafficking processes and show a novel requirement for microtubule-based motor transport in the synaptic vesicle cycle.

Keywords: BicD, clathrin, dynein, microtubule-based transport, synaptic vesicle recycling

Introduction

Microtubule-based motors have key functions in the intracellular sorting of organelles, vesicles and macromolecules. The cytoplasmic dynein motor drives transport of cargoes towards the minus-ends of microtubules, often in association with its accessory complex dynactin, whereas motors of the kinesin family mediate plus-end-directed motility (Schliwa and Woehlke, 2003). However, the molecular mechanisms by which different cargoes are linked to these motors, as well as the functional consequences of these interactions at the organismal level, are not well understood.

The Bicaudal-D (BicD) proteins (BicD in Drosophila and BicD1 and BicD2 in mammals) have important functional roles in the transport of a subset of cargoes by dynein-containing complexes, including Golgi vesicles, lipid droplets, nuclei and specific mRNAs (Claussen and Suter, 2005; Dienstbier and Li, 2009). The C-terminal third of BicD (the C-terminal domain (CTD)) mediates mutually exclusive association with different cargoes whereas the remaining N-terminal sequences contact dynein/dynactin (Hoogenraad et al, 2001, 2003; Dienstbier et al, 2009).

The original models for the role of BicD envisaged the molecule as an obligatory linker between cargoes and dynein. However, subsequent live cell imaging experiments provided evidence that BicD is not obligatory for tethering of cargoes to motor complexes but significantly increases travel distances of dynein in response to cargo (Bullock et al, 2006; Larsen et al, 2008). At least in the case of bidirectional lipid droplet movement, BicD is additionally required to augment the travel distances of kinesin-1-driven plus-end movement (Larsen et al, 2008), although it is not known whether this is due to a direct role of BicD on kinesin or reflects the tight coupling of dynein and kinesin activities in this system (Shubeita et al, 2008).

The only known cargo adaptors that bind the BicD CTD are the small GTPase Rab6 and the RNA-binding protein Egalitarian (Egl), which mediate connections from dynein to Golgi vesicles and minus-end-directed localising mRNAs, respectively (Matanis et al, 2002; Short et al, 2002; Dienstbier et al, 2009). The identification of additional proteins that bind the CTD could therefore be significant in elucidating the molecular mechanisms contributing to sorting of other cargoes by microtubule-based transport.

The cellular roles of Drosophila BicD have mostly been investigated during early developmental stages, when the protein is supplied maternally (Claussen and Suter, 2005; Dienstbier and Li, 2009). Particular attention has focussed on the function of BicD in the Egl-dependent translocation of mRNAs. In this study, we investigate the zygotic requirements for BicD in Drosophila. We show that, despite its widespread expression, BicD function is only obligatory in the nervous system during larval development and that this is not associated with its role in Egl-dependent mRNA transport. We go on to identify clathrin heavy chain (Chc) as a novel interactor of the BicD–CTD and provide evidence that this interaction facilitates Chc transport and augments the rate of synaptic vesicle recycling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Collectively, these data provide evidence that BicD and Chc are functional interactors and show a novel requirement for microtubule-based transport in the synaptic vesicle cycle.

Results

BicD is required specifically in the nervous system for larval locomotion

To explore the requirements of BicD during zygotic development, we generated BicD zygotic mutant larvae that are trans-heterozygous for two null alleles (see Materials and methods) and lack detectable maternal BicD protein from late first instar larval stages onwards (Supplementary Figure S1A). Hereafter, these animals will be referred to as BicD mutants.

As documented earlier (Ran et al, 1994), zygotic BicD mutants very rarely eclose from the pupal case and those that do die over the next few hours. We also noticed that BicD mutant third instar larvae have a strongly reduced rate of locomotion during active bouts of crawling (Figure 1A). However, they do not exhibit ‘tail-flipping' or synapse retraction phenotypes (X Li, unpublished observations) seen in some loss-of-function dynein/dynactin scenarios (Martin et al, 1999; Eaton et al, 2002), which is consistent with BicD being restricted to a subset of functions of the dynein motor (Papoulas et al, 2005; Bullock et al, 2006). Ubiquitous expression of a transgene coding for wild-type BicD rescued the larval locomotion (Figure 1A) and lethality (Supplementary Table S1) of the BicD mutants showing that these phenotypes result from the requirement for BicD, not secondary mutations in the genetic background.

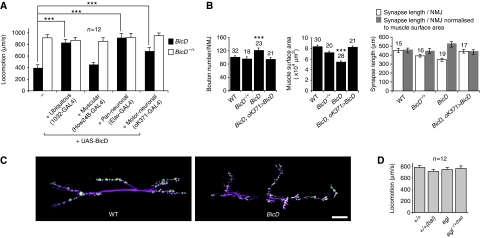

Figure 1.

BicD is required in the nervous system for normal larval locomotion and nerve terminal morphology at the NMJ. (A) Quantification of mean speed of locomotion of BicD mutant (BicD) and heterozygous control (BicD−/+) third instar larvae, with or without tissue-restricted expression of a BicD transgene. Measurements were extracted only from active bouts of crawling. In this and other figures, ***P<0.001 (t-test), error bars represent s.e.m. and WT is wild-type; n=number of larvae of each genotype. (B) Morphometric analysis of nerve terminals at the NMJ assessed at muscles 6 and 7 of segment A3. Number of NMJs analysed is indicated above bars and statistical tests (t-test) are for the comparison to WT. Nerve terminals of BicD mutants had a significant increase in synaptic bouton number. There was a trend towards a decrease in the total length of synapses in the mutant. However, the total area of the muscle was reduced in BicD, which was associated with a decrease in larval size (data not shown). The growth of the muscle and nerve terminal is intimately linked (Schuster et al, 1996) and normalisation of synapse length to muscle area indicates that there is a relative overgrowth of the presynaptic terminal in the absence of BicD. All of these phenotypes were suppressed by motor neuronal supply of BicD to the mutant larvae with ok371-GAL4. (C) Representative confocal images of synapses at the NMJ. Nervous tissue, magenta (α-HRP); synaptic boutons, green (α-Synaptotagmin). Scale bar represents 20 μm. (D) Third instar larvae exhibit normal rates of locomotion in the absence of Egl. bal, wild-type egl copy on balancer chromosome.

BicD is expressed ubiquitously in the third instar larva (data not shown). To investigate whether the requirement for BicD in locomotion results from a role in the nervous system, the musculature or both, we expressed a BicD transgene in a tissue-specific manner in BicD mutants and assayed for suppression of the mutant phenotypes. Expression of the BicD transgene pan-neuronally fully rescued larval locomotion and lethality of the mutant, whereas expression in the muscles did not (Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S1). Thus, BicD function is only obligatory in the nervous system during zygotic development.

As shown in Figure 1A, locomotion of the mutants was significantly improved by driving expression of the wild-type protein with the ok371-GAL4 driver (Mahr and Aberle, 2006), which is consistent with a strong requirement for BicD in motor neurons. BicD mutant NMJs had a small but significant increase in synaptic bouton number and there was a decrease in muscle size, and both these phenotypes were also rescued by ok371-GAL4-mediated supply of BicD (Figure 1B and C). However, this was not sufficient to fully restore locomotion (Figure 1A) or eclosion, indicating that either BicD is also important in other neurons or the timing or levels of motor neuronal expression of BicD was not optimal.

As introduced above, the best-understood role of BicD in Drosophila is as a component of dynein complexes that localise a subset of mRNAs to the minus-ends of microtubules (Claussen and Suter, 2005; Bullock et al, 2006). Here, the function of BicD is dependent on its ability to form a complex with Egl (Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Bullock et al, 2006). However, egl zygotic null larvae locomote normally (Figure 1D), do not have discernible defects in NMJ morphology or muscle size (data not shown) and survive to adulthood (Mach and Lehmann, 1997), despite the lack of detectable maternal Egl protein (Supplementary Figure S1A). Thus, BicD seems to have functions in the nervous system that are independent from Egl-mediated mRNA transport.

BicD complexes with Chc in vivo and the two proteins can interact directly

To investigate the potential molecular roles of BicD within the nervous system we searched for novel interaction partners in adult fly heads, which are enriched in neuronal cells. In multiple experiments, precipitating with an antibody to BicD led to specific capture of BicD and only one other protein visible by Coomassie staining, which had a molecular weight of ∼190 kDa (Figure 2A). Mass spectrometry showed the 190 kDa protein to be Chc (42 peptides/27% coverage), and the identity of this protein was also confirmed by western blotting of BicD immunoprecipitates from extracts of both fly heads (Figure 2B) and preparations of third instar neuromuscular systems (Supplementary Figure S1B).

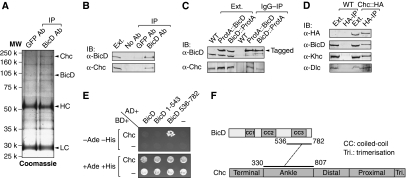

Figure 2.

BicD forms a complex with clathrin heavy chain (Chc) and interacts genetically with components of the pathway for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. (A) The identity of the 190 kDa protein specifically immunoprecipitated by anti-BicD for fly head extracts was identified as Chc by LC-MS/MS. HC and LC are the immunoglobulin heavy and light chains. (B) Confirmation of Chc as a specific interactor by western blotting. (C) Specific co-immunoprecipitation from transgenic head extracts of Chc with two protein A-tagged BicD fusions. (D) Specific co-immunoprecipitation of BicD and motor components from head extracts expressing Chc∷HA (Khc, kinesin-1 heavy chain; Dlc, dynein light chain). The volume of extracts (Ext.) shown on the blots in (B–D) is equivalent to 1/6th volume of input for immunoprecipitation (IP). IB, immunoblotting. (E) Representative yeast two-hybrid data; additional results are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Strains containing interacting pairs of constructs reconstitute biosynthesis of Ade and His. Each strain exhibits equivalent growth in the presence of Ade and His. The lack of binding between Chc and full-length BicD is consistent with previous studies showing that the binding of the CTD to its partners is suppressed within the intact BicD molecule because of an intramolecular interaction with the N-terminal region (Hoogenraad et al, 2003; Moorhead et al, 2007). (F) Schematic representation of the minimal interacting fragments of BicD and Chc mapped.

Chc was also co-precipitated when IgG was used to purify protein A-tagged BicD (fused either at the N- or C-terminus) from head extracts made from transgenic flies expressing low levels of fusion protein (Figure 2C). In contrast, neither BicD nor Chc was precipitated by IgG from head extracts made from non-transgenic flies (Figure 2C). Furthermore, BicD was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA from transgenic head extracts expressing HA-tagged Chc, but not from wild-type head extracts (Figure 2D). The amount of HA-tagged Chc in these extracts was similar to that of wild-type Chc (Supplementary Figure S1C), indicating that Chc–HA is not strongly overexpressed. Components of the dynein and kinesin-1 complexes were also co-immunoprecipitated with Chc–HA (Figure 2D), consistent with an association of BicD with these motors (Hoogenraad et al, 2003; Grigoriev et al, 2007). The above data show that Chc forms a stable complex with BicD and microtubule motor proteins.

The lack of specific enrichment of other proteins in the BicD immunoprecipitates (Figure 2A) raised the possibility that Chc and BicD could interact directly. In support of this notion, we mapped a specific interaction between a CTD of BicD (CTD (amino acid 536–782)) with Chc 330–807 in the yeast two-hybrid system (Figure 2E and F; Supplementary Table S2). As introduced above, the CTD binds cargo-specific adaptor proteins, with the N-terminal region responsible for contacting the motor complex (Hoogenraad et al, 2003). Thus, Chc could be a novel cargo adaptor for BicD/dynein, or a cargo itself.

BicD interacts genetically with components of the pathway for clathrin-mediated membrane trafficking

Chc is a major constituent of coated pits and vesicles and has a key function in several membrane trafficking processes (Pearse and Robinson, 1990). To explore whether BicD functions together with clathrin in vivo, we first tested whether BicD interacts genetically with a temperature-sensitive (ts) allele of the shibire (shi) gene, which encodes a dynamin GTPase required for scission of clathrin-coated vesicles. At elevated temperatures shits flies are reversibly paralysed because inhibition of endocytosis prevents the replenishment of synaptic vesicles at nerve terminals, leading to a block in neurotransmitter release (Koenig and Ikeda, 1989). Halving BicD gene dosage resulted in a significant decrease in the time taken for shits flies to be paralysed on shifting to the restrictive temperature, as well as a significant delay in their recovery on returning to the permissive temperature (Figure 3A). The enhancement of the shi phenotype on lowering BicD dosage indicates that BicD normally promotes a dynamin-dependent process involved in neurotransmission.

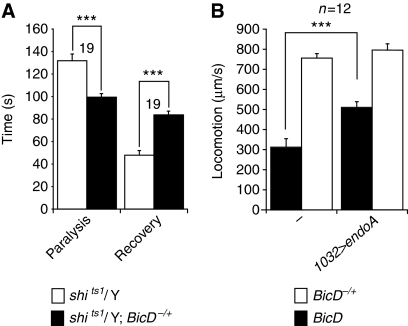

Figure 3.

BicD interacts genetically with components of the pathway for clathrin-mediated membrane trafficking. (A) Significant increase in the severity of a dynamin temperature sensitive (shits1) paralytic phenotype in adult flies by reducing BicD gene dosage. Mean time taken for paralysis after shift from the permissive temperature (22°C) to the restrictive temperature (30°C) and subsequent recovery on return to the permissive temperature is shown. The null allele was BicDr5. In the absence of shits1, BicD−/+ flies did not exhibit a paralysis phenotype at the restrictive temperature, even over extended periods. (B) Statistically significant suppression of the locomotion rate phenotype of BicD mutant third instar larvae by overexpression of UAS-endoA (using the ubiquitous driver 1032-GAL4). Number for animals of each genotype is shown above bars; t-tests were used to assess statistical significance. The data in (A) and (B) are representative of two independent experiments conducted for each assay.

We also tested whether BicD interacts genetically with endophilinA (endoA), which encodes a protein functionally implicated only in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the nervous system, where it seems to control a rate-limiting step (Ringstad et al, 1999; Guichet et al, 2002; Verstreken et al, 2002; Voglmaier et al, 2006). Overexpression of EndoA partially suppressed the defects in larval locomotion caused by the absence of BicD (Figure 3B), but was not sufficient to rescue lethality. Collectively, these genetic interactions raise the possibility that BicD function is associated either directly or indirectly with the clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway.

BicD co-localises with a subset of Chc puncta inside synaptic boutons

We next examined the relative distributions of BicD and Chc in presynaptic boutons at Drosophila NMJs, a well-studied model for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Owing to expression of BicD in both muscles and neurons at the NMJ it was necessary to use neuronal-specific expression of a triple eGFP-tagged version of the protein to resolve its subcellular localisation within boutons. This fusion protein, which retained BicD function (Supplementary Materials and methods), had a prominent enrichment towards the periphery of boutons and also resolved into many bright puncta residing more internally (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S2A). Available antibodies to Drosophila Chc (including new ones generated by ourselves) did not work in immunostaining, so we expressed a Chc∷mCherry fusion presynaptically. This protein was targeted to patches on the plasma membrane adjacent to the sites of exocytosis (active zones; marked with nc82 (Wagh et al, 2006)) (Supplementary Figure S2B), which are likely to be endocytic hotspots (periactive zones) (Roos and Kelly, 1999).

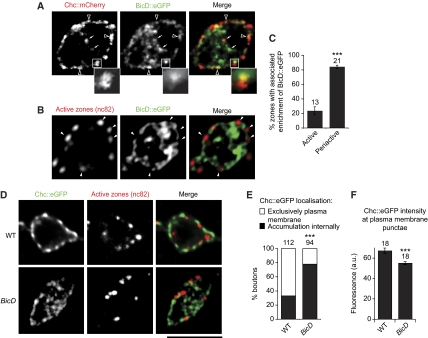

Figure 4.

BicD has an overlapping distribution with a subset of Chc puncta inside boutons and is required for appropriate Chc localisation. (A) BicD∷eGFP overlaps with a subset of internal puncta of Chc∷mCherry (arrows) and also shows enrichment beneath, or partially overlapping with, many periactive zones marked with Chc∷mCherry (e.g. open arrowheads). Inset, magnification of the boxed region showing example of overlap of BicD∷eGFP with the most internal region of the Chc∷mCherry signal. See Supplementary Figure S2A for additional examples of relative distribution of BicD and Chc. It has been shown earlier that the amount of BicD recruited is not necessarily proportional to the size of the cargo (Bullock et al, 2006). (B) BicD∷eGFP enrichment is not associated with most active zones (marked with nc82). Interruptions in the peripheral BicD signal frequently co-incide with a region containing an active zone (arrowheads). (C) Quantification of a significant enrichment of BicD∷eGFP associated with (i.e. either overlapping of immediately beneath) periactive zones (marked with Chc∷mCherry) compared with active zones (marked with nc82); n=number of boutons analysed. (D) Substantial internal mislocalisation of Chc∷eGFP in BicD mutant boutons. Location and number of active zones are not affected by the BicD mutation. (E, F) Quantification of the internal accumulation (E) and reduced plasma membrane accumulation (F; a.u., arbitrary units (mean fluorescence/pixel)) of Chc in BicD mutant boutons; n=number of boutons analysed. See Supplementary Materials and methods for details of scoring procedures used for Figure 4. Fluorescent protein signals were amplified using anti-GFP or anti-dsRed antibodies. In (C) and (F), a t-test was used to compare means. Fisher's exact test was used in (E). Scale bar represents 5 μm for main images and 1.2 μm for inset in (A).

We occasionally observed Chc∷mCherry puncta within the bouton cytoplasm and 70% of these (n=46) co-localised with a discernible punctum of BicD∷eGFP (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S2A). This co-localisation is meaningful as signals from a control protein with a more widespread punctate distribution within boutons showed significantly less co-localisation with BicD (Supplementary Figure S2C; 27% of Rab7 puncta (n=98) co-localised with BicD signal (P<0.0001, Fisher's exact test)). Most BicD puncta, however, did not overlap with internal Chc. This is expected from observations in other cell types of a widespread distribution of BicD relative to its cargoes, probably representing a pool of auto-inhibited protein in the absence of an available consignment (Bullock and Ish-Horowicz, 2001; Hoogenraad et al, 2003). We also observed puncta of BicD beneath a significant proportion of periactive zones, often overlapping with the most internal areas of Chc accumulation, and mostly excluded from active zones (Figure 4A–C).

The results from these localisation studies indicate that BicD is associated with the endocytic membrane system and its distribution overlaps with a portion of Chc, predominantly from the pool that is not in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. The binding of BicD to Chc could conceivably be contingent on other events, such as the dissociation of other clathrin-binding partners.

BicD is required for appropriate localisation of Chc

To explore whether BicD has a functional role with Chc, we compared the localisation of Chc∷eGFP in fixed wild-type and BicD mutant boutons. Chc:eGFP was correctly targeted to periactive zones in wild-type boutons—as judged by striking co-localisation with a component of the AP2 adaptor complex (Supplementary Figure S2B) and mutually exclusive distribution with nc82 (Figure 4D)—and did not interfere with normal membrane internalisation or release (Supplementary Figure S3).

In 67% of wild-type boutons, Chc∷eGFP was exclusively enriched at the plasma membrane (Figure 4D and E). A substantial internal accumulation of the protein was also detected in the remaining boutons. In contrast, exclusive localisation of Chc∷eGFP at the plasma membrane was seen in only 22% of BicD mutant boutons (significantly different from wild type; P<0.0001 (Fisher's exact test)), with the remainder having a strong accumulation of the protein internally, often in large puncta (Figure 4D and E). There was also a subtle, but highly statistically significant, decrease in the intensity of Chc∷eGFP signal within the puncta at the plasma membrane in BicD mutants (Figure 4D and F), indicating that BicD is required for efficient localisation of Chc to periactive zones.

The distributions of several proteins involved in membrane trafficking (dynamin, Dap160, Eps15, α-adaptin, EndoA, Hrs and Rabs 5, 6, 7 and 11), as well as markers of active zones (nc82) and synaptic vesicles (Vglut, Csp and Synaptotagmin (Syt)) were not overtly sensitive to loss of BicD (Figure 4E; Supplementary Figure S4A and S4A′). Thus, the overall organisation of the membrane trafficking system was not grossly perturbed by the absence of BicD, implying that the protein could have a direct role in controlling Chc localisation.

BicD mediates efficient-directed transport of Chc within presynaptic boutons

The above data, together with our finding that Chc can associate with the domain of BicD that links cargoes to dynein complexes, indicated that BicD might control localisation of Chc-containing structures by mediating their microtubule-based transport. To explore this possibility further we used time-lapse imaging to examine Chc dynamics in live boutons of neuromuscular preparations. In wild-type boutons, we occasionally observed discrete puncta of Chc∷mCherry or Chc∷eGFP that were not associated with the plasma membrane. Many of these underwent periods of directed motion (Supplementary Movies S1 and S2) with instantaneous velocities of ∼0.4–0.6 μm/s, consistent with the involvement of a cytoskeletal motor. In every case examined, these movements appeared to follow a prominent microtubule bundle (Figure 5A; Supplementary Movie S1), implying that a microtubule-based motor was responsible. Owing to the low fluorescence and high motility of the Chc puncta, coupled to occasional muscle contraction within the preparations, it was not possible to follow their complete trajectories to determine where they might have originated or terminated their journeys. It should also be noted that, because of these technical difficulties, we are only able to resolve large motile Chc structures in our movies. It seems plausible that smaller Chc-positive cargoes will also be subjected to transport, but that these are below our detection threshold.

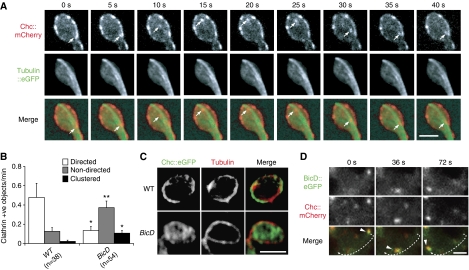

Figure 5.

BicD participates in a microtubule-based pathway for transport of Chc-positive structures. (A) Stills from Supplementary Movie S1 showing motile Chc∷mCherry objects (arrows) apparently in association with Tubulin∷eGFP-labelled microtubules. The indicated object(s) moved with instantaneous velocities of ∼0.4 μm/s. (B) Quantification of motility and clustering of Chc∷eGFP structures per bouton; n=number of boutons analysed; values on the y axis are the mean number (per bouton) of internal Chc-positive objects displaying each behaviour per min. **P<0.01; *P<0.05; t-test. Particles were classified as ‘directed' if they at some point followed a similar trajectory for three successive 1 s frames, with a velocity of at least 0.13 μm/s (2 pixels/frame). ‘Non-directed' particles were all other discrete particles, and exhibited both immobile and oscillatory behaviours. An additional population was classified, consisting of immotile clusters of several objects with a total long axis of the fluorescent signal of ∼0.4–0.8 μm. In independent experiments we confirmed that there is a similar ratio of directed to non-directed Chc-positive objects in wild-type and BicD heterozygous boutons. (C) The integrity of microtubules is not altered in fixed BicD mutant boutons with mislocalised Chc∷eGFP. The central location of Chc in BicD boutons, away from the bulk of microtubule signal, may reflect diffusion in the absence of efficient motor-based tethering to microtubules, prior transport on dynamic microtubules (Pawson et al, 2008) or destruction of a more uniform microtubule network on fixation (Yan and Broadie, 2007). GFP signal was enhanced with anti-GFP. (D) Stills of Supplementary Movie S3 showing example of co-localisation of BicD∷eGFP and Chc∷mCherry on a motile particle (arrowhead) in the stage 1 germarium of the egg chamber. In control experiments, other mCherry and GFP fusions do not exhibit such co-localisation or co-transport. Line indicates path taken by an object positive for both markers that travels at a maximum velocity of ∼0.4 μm/s. Net displacement is relatively slow because of pauses and reversals, reminiscent of other BicD-dependent cargoes (Bullock et al, 2006). Red and green signals do not always overlap precisely on motile objects because of sequential capture of the two channels. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

We found a dramatic alteration in the behaviour of Chc-positive structures within the cytoplasm in BicD mutant boutons relative to wild type (Supplementary Movie S2; Figure 5B). There was a strong reduction in the number of discrete internal structures undergoing bouts of rapid, directed motion in the mutants. There was also a corresponding increase in the number of discrete structures that were either immobile or oscillatory (Figure 5B).

We did not observe defects in microtubule organisation in mutant boutons with Chc mislocalised to the centre (Figure 5C). The distributions of dynein and kinesin-1 were also indistinguishable between wild-type and BicD mutant boutons (Supplementary Figure S4A′). These observations are consistent with BicD having a direct role in Chc transport. As noted above, BicD signal seems to be associated with a subset of internal puncta of Chc within synaptic boutons (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S2B). Although the weak intensity of the BicD∷eGFP fusion prevented us from determining whether these represent motile structures, BicD∷eGFP was found associated with highly motile Chc∷mCherry particles in early egg chambers, which are much better suited to optical analysis (Figure 5D; Supplementary Movie S3). The results described in this section, together with (1) the statistically significant overlap of BicD and Chc signals in synaptic boutons and (2) the biochemical data showing that Chc is an abundant interactor of BicD in fly heads, strongly support a role for BicD in nerve terminals as part of microtubule-based motor complexes that translocate clathrin-positive cargoes.

BicD and dynein are needed to maintain normal levels of neurotransmitter release and membrane recycling during high-frequency stimulation

We next addressed the potential functional significance of BicD-mediated transport of Chc by assaying vesicle recycling in synaptic boutons. Clathrin-mediated membrane retrieval sustains normal levels of neurotransmitter release during periods of high-frequency stimulation; responses to low-frequency stimulation are less dependent on the overall activity of the clathrin endocytic pathway and may also use clathrin-independent mechanisms (Verstreken et al, 2002; Dickman et al, 2005).

In BicD mutants, as well as strong dynein heavy chain (Dhc) hypomorphic mutants (Dhc64C4–19/Dhc64C6–10 (Gepner et al, 1996)), amplitudes of evoked excitatory junctional potentials (EJPs) in abdominal muscles (a measure of the extent of neurotransmitter release) were indistinguishable from wild type for at least 30 min of low-frequency electrical stimulation (0.5 Hz) of motor neurons (Figure 6A). In control experiments, EJP amplitudes declined sharply in shits animals at the restrictive temperature during 0.5 Hz stimulation (Figure 6A), which is likely to be associated with dynamin's role in scission of clathrin-coated structures from the plasma membrane (Heerssen et al, 2008; Kasprowicz et al, 2008). Thus, BicD does not seem to be functionally required for clathrin-mediated endocytosis during low-frequency stimulation.

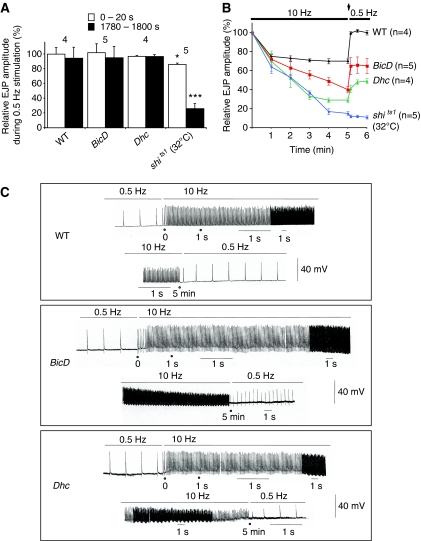

Figure 6.

BicD and dynein are required to maintain normal levels of neurotransmission during high-frequency stimulation. (A) EJP amplitudes during 0.5 Hz electrical stimulation, averaged during the indicated periods. The number of preparations is indicated above columns. (B) EJP amplitudes during 10 Hz stimulation and subsequent switching to 0.5 Hz; n=number of preparations of each genotype. (C) Representative traces of EJPs from individual preparations. The timescale changes as the speed of the logging device is adjusted. In (A–C), muscles 6 and 7 of segments A3 and A4 were analysed and recordings made in HL3 medium with 1.5 mM Ca2+.

The amplitude and frequency of spontaneous miniature EJPs (mEJPs) in BicD and Dhc preparations were not significantly different from wild type (Supplementary Figure S5), providing further evidence that basal endocytic and exocytic events are not sensitive at the electrophysiological level to BicD or dynein function.

In contrast, BicD and Dhc mutants were unable to sustain normal levels of neurotransmission during high-frequency electrical stimulation. EJP amplitudes in the mutants declined abnormally rapidly within 5 min of stimulation at 10 Hz (Figure 6B and C; BicD and Dhc amplitudes were, respectively, 55 and 40% of wild-type levels at 5 min (significantly different to wild type [P<0.001, t-test])). The decline in EJP amplitude response in BicD and Dhc mutants was not as large as that observed in shits preparations at the restrictive temperature (Figure 6B), indicating that BicD and dynein are not obligatory for dynamin-mediated membrane retrieval. Lending further support to this notion, there was an upturn in EJP amplitudes after switching from 10 to 0.5 Hz stimulation in BicD and Dhc mutants, but not in shits mutants (Figure 6B and C).

The EJP response did not reach wild-type levels in BicD and Dhc mutants even 100 s after switching from high- to low-frequency stimulation (Figure 6B). The normal EJP response during low-frequency stimulation in the BicD and Dhc mutants, coupled to the incomplete reduction of the dynamin-dependent EJP response during 10 Hz stimulation and the compromised recovery on returning to low-frequency stimulation, is reminiscent of what was observed when the function of EndoA or Synaptojanin (Synj) is disrupted (Dickman et al, 2005). These two proteins stimulate internalisation and/or uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles (Ringstad et al, 1999; Gad et al, 2000; Haffner et al, 2000) and this spectrum of mutant phenotypes was interpreted as revealing persistent, slowed clathrin-based membrane recycling (Dickman et al, 2005).

The total amount of the lipophilic dye FM 1-43 (Betz and Bewick, 1992) taken up into boutons during 10 Hz stimulation was significantly reduced in BicD and Dhc mutants compared with controls (Figure 7A and B) showing that the reduction in levels of neurotransmission is indeed associated with a defect in membrane uptake. Thus, BicD and dynein are functionally required for efficient membrane recycling specifically during high-frequency electrical stimulation, that is when there is demand for a rapid rate of clathrin-dependent membrane retrieval.

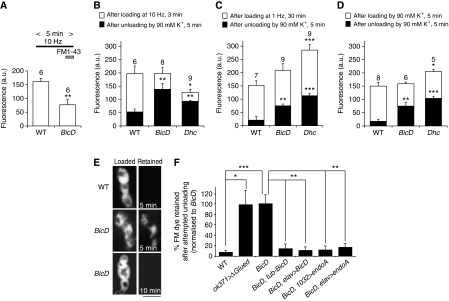

Figure 7.

BicD and dynein are required for efficient recycling of membrane internalised during high-frequency stimulation. (A–D) Quantification of FM1-43 dye uptake, as well as release (B–D), in wild-type (WT) and BicD mutants. Solutions contained 2 mM Ca2+. The number of preparations is indicated above columns. Total height of column is amount of dye loaded under different stimulatory conditions as indicated, with black sections in (B–D) representing the amount of dye retained after 5 min of subsequent K+-mediated stimulation of membrane release; a.u., arbitrary units (mean fluorescence/pixel). In (B), a similar amount of dye was loaded into BicD and wild-type boutons during the first 3 min of 10 Hz stimulation, consistent with only a subtle difference in the cumulative amplitudes of EJPs at this time point (Figure 6B). The reduction in FM dye uptake in Dhc mutants after 3 min of 10 Hz stimulation (B) is consistent with the sharp decrease at this time point in exocytosis (Figure 6B), which is tightly linked to membrane uptake (Dickman et al, 2005). In all assays the Dhc phenotype is more severe than that of BicD, consistent with BicD not being absolutely essential for movements of cargo by dynein (Bullock et al, 2006). The compensatory mechanisms that increase dye uptake in mutants at 1 Hz (see text) may also contribute to the elevated dye uptake in Dhc mutants during potassium stimulation. (E) Representative images of dye uptake and release (stimulated by 5 or 10 min 90 mM K+, as indicated) in wild-type and BicD mutant boutons. Images shown are of samples in which dye was loaded in the presence of 90 mM K+ for 5 min, although similar images were obtained using 3 min of 10 Hz stimulation. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (F) FM dye release experiments, using the regime shown in (D), showing a defect in vesicle unloading by presynaptic expression of dominant negative Glued (ΔGlued) and a complete suppression of the BicD mutant dye retention defect by pan-neuronal expression of BicD or Endophilin A transgenes. The results of ubiquitous expression of BicD and Endophilin A are shown for comparison. Five preparations were assayed for each genotype. There was no significant difference in dye loading between all genotypes.

As rates of membrane uptake and release in the nerve terminal are strictly dependent on each other (Dickman et al, 2005), a perturbation in either process, or both, could be behind the failure of BicD mutants to sustain normal levels of neurotransmission and FM1-43 loading into boutons during high-frequency stimulation. To test whether the role of BicD and dynein was restricted to the uptake of membrane, we assayed membrane release in isolation by measuring the potassium-induced unloading of FM1-43 pre-loaded into an internalised vesicle population during different stimulatory regimes. These experiments showed a strong requirement for BicD and dynein heavy chain for efficient release of synaptic membrane that is pre-internalised during high-frequency electrical stimulation (Figure 7B). In the BicD and Dhc mutants, there was also a significant, but less dramatic, increase in the retention of membrane internalised during low-frequency electrical stimulation or chemical stimulation with 90 mM potassium compared with wild type (Figure 7C and D). During low-frequency stimulation, this release defect appeared to be counteracted by a compensatory increase in membrane uptake, leading to equivalence in the amount of internalised vesicles that were released in the three genotypes (Figure 7C). Such a compensatory mechanism is presumably not sufficient to maintain normal levels of neurotransmission when the demand for membrane recycling is increased during intense stimulation.

Internalised membrane was not trapped irreversibly by inhibition of BicD-mediated transport, however, as the FM1-43 retained in the BicD mutant was liberated by increasing the duration of potassium stimulation during the release phase of the protocol from 5 to 10 min (Figure 7E). Thus, BicD is required to augment the rate of recycling of internalised membrane. This requirement reflects a presynaptic role of BicD, as the dye release defect in BicD mutants was fully rescued by expressing a BicD transgene using the ok371-GAL4 driver (Figure 7F). We also noted FM dye release defects when a dominant negative version of the Glued subunit of dynein's accessory complex dynactin (Mische et al, 2007) was expressed presynaptically (Figure 7F), further strengthening the link between BicD and dynein in the synaptic vesicle cycle.

A kinetic role of BicD-mediated transport in vesicle recycling was also supported by our observation that dye release defects of BicD mutants could be fully suppressed by presynaptic overexpression of EndoA (Figure 7F). This presumably reflects a reduction in the total duration of the synaptic vesicle cycle as a result of accelerating clathrin-associated endocytic or post-endocytic events (Ringstad et al, 1999; Gad et al, 2000; Haffner et al, 2000).

Synaptic vesicles within Drosophila boutons belong to either the ‘readily releasable' (or ‘exo/endo') pool or the ‘reserve' pool (Kuromi and Kidokoro, 1998). Constituents of the reserve pool can only be released by high-frequency electrical stimulation (Kuromi and Kidokoro, 1998). Therefore, the finding that the internalised membrane whose recycling is perturbed in BicD mutants can be released by prolonged potassium stimulation shows that BicD/dynein transport functions in the pathway for recycling the readily releasable pool.

Ultrastructural analysis of BicD mutant synapses

To attempt to further define the role of BicD in the synaptic vesicle cycle we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visualise the ultrastructure of synapses within third instar larval NMJs. There were no discernible differences in the overall number or spatial distribution of vesicles between resting wild-type and BicD mutant boutons (Figure 8A and B; Supplementary Figure S6A), consistent with the previous light microscopic analysis of vesicle marker proteins (Supplementary Figure S4A and S4A′).

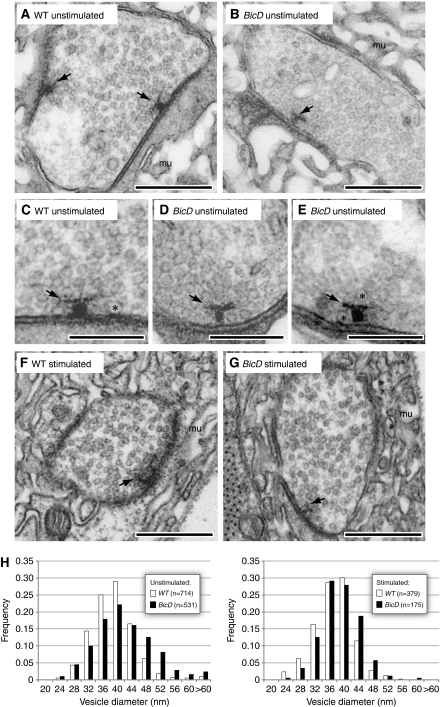

Figure 8.

Ultrastructural analysis of wild-type (WT) and BicD mutant synaptic boutons innervating muscle 6/7 in segment A4 of third instar larvae by thin-section TEM. (A, B, F, G) Overall architecture of synaptic boutons that are resting (A, B) or that have been stimulated for 10 min with 15 Hz electrical stimulation (in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+), followed by 2 min rest (F, G). Scale bars represent 500 nm. Arrows, T-bars; mu, muscle. Active zones, when captured in the image, are the highly stained sections of the presynaptic membrane, which match up with a highly stained region of the post-synaptic membrane. There are no gross differences in the ultrastructure of wild-type and mutant synapses under both conditions. (C–E) Representative active zones of resting synapses. Asterisks indicate examples of relatively large synaptic vesicles and scale bars represent 250 nm. See Supplementary Figure S6 for additional examples of TEM images. (H) Distribution of synaptic vesicle diameters, scored in association with active zones, in synapses that are resting or have been stimulated as described above. There is a modest shift towards enlarged vesicle sizes in BicD mutants compared with wild-type (WT) under both conditions (see Table I); n=number of vesicles. Note that the decrease in synaptic vesicle size within the same genotype on stimulation followed by recovery, compared with unstimulated specimens, is consistent with previous observations (Poskanzer et al, 2006).

The number of vesicles within 250 nm of active zones, as well as the number in contact with the active zone plasma membrane, was also not significantly different in the two genotypes (Figure 8C–E; Table 1). Unlike shibire or endoA mutant synapses (Koenig and Ikeda, 1989; Guichet et al, 2002; Verstreken et al, 2002), BicD mutant synapses did not contain unusual endocytic intermediates associated with the plasma membrane (Figure 8A and B; Supplementary Figure 6A). Nor did we observe evidence of bulk endocytosis of the plasma membrane, as is evident when clathrin function is very strongly inhibited (Heerssen et al, 2008; Kasprowicz et al, 2008). An accumulation of densely coated vesicles was also not detectable in the BicD synapses. Such an accumulation has been reported in NMJ synapses of endoA and synj mutants, likely because of a defect in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles (Verstreken et al, 2002, 2003).

Table 1. Quantification of ultrastructural features of wild-type and BicD synapses.

| Unstimulated | Stimulateda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n) | BicD (n) | WT (n) | BicD (n) | |

| Vesicle diameter (nm)b | 37.30±0.32 (714) | 40.10±0.43 (531)*** | 35.36±0.27 (379) | 37.01±0.40 (175)*** |

| No. vesicles within 250 nm of AZc | 20.97±1.1 (38) | 20.34±0.8 (29) | 20.77±4.24 (18) | 15.91±2.08 (11) |

| No. vesicles contacting AZ plasma membranec,d | 5.47±0.26 (44) | 5.31±0.29 (29) | 3.06±0.38 (18) | 1.64±0.152 (11)** |

| Mean values are shown ±s.e.m. AZ, active zone. Differences are not statistically significant (t-test) unless shown: *** and **, P<0.001 and <0.01, respectively (BicD unstimulated compared with wild-type unstimulated and BicD stimulated compared with wild-type stimulated). | ||||

| a15 Hz for 10 min in HL3 medium with 2 mM Ca2+, followed by 2 min rest. | ||||

| bVesicles were scored within 250 nm of active zone and n=no. of vesicles. Note that the decrease in synaptic vesicle size within the same genotype on stimulation followed by recovery, compared with unstimulated specimens, is consistent with previous observations (Poskanzer et al, 2006). | ||||

| cn=no. of scoreable active zones. | ||||

| dVesicles were scored within 250 nm of a T-bar or, if a T-bar was not present, within 250 nm of the centre of the active zone. Data were collected from synapses innervating muscle 6/7 of segment A4. Quantification was based on 11 boutons (37 sections) for wild-type unstimulated, 7 boutons (33 sections) for BicD stimulated, 10 boutons (1 section of each) for wild-type stimulated and 7 sections (1 section of each) for BicD stimulated. | ||||

A reduced number of mitochondria in resting boutons can lead to an inability to maintain normal levels of neurotransmission during high-frequency stimulation (Verstreken et al, 2005). However, a defect in localising mitochondria to synapses does not seem to underpin the BicD mutant neurotransmission phenotype because there was no significant reduction, per section, in the mitochondrial number (wild type 2.00±0.26 (n=33 sections); BicD 2.45±0.26 (n=33 sections)) and total area occupied by the mitochondria (wild type 0.20±0.03 μm2; BicD 0.21±0.04 μm2).

Collectively, these observations provide further evidence that there is not an obligatory requirement for BicD in endocytosis or exocytosis and show that the BicD mutant phenotype is unlikely to be associated with a strong defect in uncoating clathrin from vesicles or in the localisation of the mitochondria to synapses.

Interestingly, there was a modest, but highly statistically significant, increase in the mean diameter of synaptic vesicles in BicD mutant synapses compared with wild-type because of a overall shift in the distribution of vesicle sizes (Table 1; Figure 8H). Increases in vesicle size are often characteristic of alterations in endocytic processes, potentially reflecting defects in shaping nascent clathrin-coated vesicles (Zhang et al, 1998; Koh et al, 2004, 2007; Dickman et al, 2005). The magnitude of the increase in mean vesicle size in BicD mutants seems to be similar to that reported in synj null mutants (Dickman et al, 2005). This increase is presumably not sufficient to significantly alter the amount of neurotransmitter released per vesicle; the mEJP amplitude in BicD mutants is not different to wild type (Supplementary Figure S5), as was also the case in the absence of Synj (Dickman et al, 2005).

As the functional consequences of the BicD mutation on synaptic vesicle recycling are only revealed by intense stimulation (Figures 6 and 7), we also performed ultrastructural analysis of synapses within wild-type and mutant third instar larval specimens that had been stimulated at 15 Hz for 10 min, followed by 2 min recovery. We performed this strong stimulation to maximise our chances of capturing any morphologically visible phenotype. As was the case for resting boutons, we did not detect evidence of unusual endocytic intermediates, bulk endocytosis or an abnormal build up of densely coated vesicles in the stimulated BicD synapses (Figure 8F and G; Supplementary Figure S6B). These data indicate that, even during high-frequency stimulation, BicD is not directly required for budding of clathrin-mediated vesicles from the plasma membrane or subsequent uncoating.

However, as was the case for resting boutons, a potential link between BicD and endocytic mechanisms was suggested by a subtle, but highly statistically significant, increase in the diameter of synaptic vesicles in stimulated BicD mutants compared with stimulated wild-type synapses (Figure 8H; Table 1). A specific defect in endocytosis in mutant synapses is frequently characterised by a strongly reduced number of synaptic vesicles (e.g. Zhang et al, 1998; Koh et al, 2004; Dickman et al, 2005; Koh et al, 2007). The overall number and density of vesicles was not, however, discernibly different in stimulated BicD mutants compared with wild type (Figure 8F and G; Supplementary Figure S6B). This presumably reflects the combination of slowed release of internalised membrane (Figure 7B) and slowed membrane internalisation (Figure 7A).

We next probed the basis of the synaptic vesicle release defects in stimulated BicD mutant synapses. In mutants for proteins that are directly required for the exocytic event there is a striking build up of synaptic vesicles associated with the active zone membrane (e.g. Kawasaki et al, 1998; Littleton et al, 1998). However, this was not the case in stimulated BicD mutant synapses (Table 1). There was, in fact, a reduction in the average number of vesicles in contact with an active zone plasma membrane in the stimulated BicD mutant synapses (1.64±0.15 (n=11 active zones)), compared with the stimulated wild-type synapses (3.06±0.38 (n=18 active zones); P<0.01; t-test). Thus, the slowed rate of release of internalised membrane in stimulated BicD mutant synapses is more likely to be associated with a compromised ability of vesicles to reach release sites than a specific defect in vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane. Our observation that BicD accumulates beneath periactive zones and is rarely found at active zones (Figure 4A–C) raises the possibility that BicD contributes to efficient release because of a role in post-endocytic trafficking and/or maturation steps (see Discussion).

Discussion

BicD is required in the nervous system and is a novel functional interactor of Chc

The genetic requirement of BicD at the organismal level had previously only been investigated in detail during maternal stages in Drosophila. In this study, we describe the unexpected finding that zygotic BicD function is obligatory only in the nervous system, despite its widespread expression during larval stages. This function seems to be independent of BicD's well-known role in Egl-dependent mRNA transport.

We subsequently identified Chc as the major BicD-associated protein in head extracts and mapped a direct interaction between the C-terminal third of BicD and the Chc ankle domain. This region of BicD provides a link between cellular cargoes and the dynein motor (Matanis et al, 2002; Short et al, 2002; Januschke et al, 2007; Dienstbier et al, 2009). Consistent with clathrin acting as a cargo for BicD/dynein, the directed transport of Chc∷eGFP in association with microtubules is strongly reduced in BicD mutant presynaptic boutons leading to aberrant accumulation of the protein internally and a partial reduction in clathrin levels at the plasma membrane. Changes in microtubule integrity were not observed in BicD mutant boutons. In addition, a statistically significant portion of Chc signals overlapped with BicD signals within boutons and highly motile structures containing both Chc and BicD were observed in egg chambers, which are suited to sensitive time-lapse imaging. Collectively, these data build a strong case for disruption of Chc motility in boutons being a consequence of a direct requirement for BicD in microtubule-based transport complexes.

In the case of embryonic transport of mRNA and lipid droplets in Drosophila, BicD does not seem to be obligatory for linkage of cargoes to the bidirectional motor complex, but leads to efficient transport by augmenting the persistence of motor movement (Bullock et al, 2006; Larsen et al, 2008). The presence of some residual directed motion of Chc∷eGFP in mutant boutons raises the possibility that BicD serves an analogous, stimulatory function in the transport of clathrin-associated cargoes.

It should also be pointed out that although the readily discernible phenotypic requirement for Drosophila BicD is restricted to neuronal tissue, this does not rule out a role for BicD in modulating the kinetics of clathrin-mediated mechanisms in non-neuronal cells, especially in other species. Highly motile clathrin-labelled structures within cultured mammalian cells are translocated by dynein on microtubules (Zhao et al, 2007), raising the possibility of a conserved involvement of the BicD–Chc interaction.

BicD has activity-dependent requirements during the synaptic vesicle cycle

Our functional assays show a novel requirement for BicD and dynein in the maintenance of normal levels of neurotransmission during high-frequency electrical stimulation. The function of these factors is not, however, functionally limiting during low-frequency stimulation. BicD and dynein therefore join a group of other clathrin-associated proteins in Drosophila, such as Dap160, AP180, EndophilinA and Synaptojanin, in being required to maintain normal levels of neurotransmission specifically during periods of intense stimulation (Zhang et al, 1998; Verstreken et al, 2002, 2003; Koh et al, 2004; Marie et al, 2004).

Experiments assaying FM1-43 dye uptake and release showed that BicD and dynein are required for efficient membrane uptake specifically during intense electrical stimulation. This defect is associated, at least in part, with a requirement for augmenting the rate of release of pre-internalised vesicles. However, because rates of membrane uptake are intimately linked to rates of membrane release (Dickman et al, 2005), the experiments performed could not directly measure endocytic rates in isolation. Ultrastructural analysis did not show dramatic changes in the organisation or morphology of the membrane trafficking system in resting or stimulated BicD mutant synapses. Collectively, our data indicate that BicD has a kinetic function in stimulating the rate of recycling of pre-internalised vesicles, as opposed to an obligatory role in any one step. This requirement for BicD is almost certainly associated with its well-characterised role in stimulating cargo transport by microtubule-based motors, as inhibition of dynein heavy chain and dynactin resulted in very similar effects on vesicle recycling to those seen in BicD mutants.

To date the actin cytoskeleton has been heavily implicated in synaptic membrane recycling (Schweizer and Ryan, 2006). However, the absence of chronic problems in synaptic morphology and membrane organisation in BicD mutant boutons is consistent with microtubule-based transport also participating directly in the synaptic vesicle cycle. In support of this notion, microtubules are prominent in boutons (Roos et al, 2000; Yan and Broadie, 2007; Pawson et al, 2008) and acute, efficient interference with their integrity inhibits neurotransmission (A Honda, Y Kidokoro and HK, paper in preparation).

Potential molecular mechanisms contributing to the requirement for BicD and dynein in the synaptic vesicle cycle

As discussed above, BicD is likely to have a role in the transport of a subset of cargoes by dynein. However, the previously known BicD interaction partners do not seem to contribute significantly to the synaptic vesicle recycling phenotype in the BicD mutants; Egl function appears to be strictly maternal and Rab6 is not detectable in presynaptic boutons and its distribution in axons of motor neurons is not sensitive to the absence of BicD (Supplementary Figure S4B).

We do not wish to rule out the possibility of other, potentially unidentified, BicD cargoes contributing to the synaptic vesicle recycling phenotype in the mutants—in fact, we think it is quite plausible. However, several lines of evidence point towards an important involvement of the interaction of BicD with Chc: (1) Chc is by far the most abundant protein stably associated with BicD in head extracts; (2) presynaptic overexpression of EndoA, which is rate-limiting for clathrin-mediated endocytosis and/or uncoating (Ringstad et al, 1999; Gad et al, 2000; Haffner et al, 2000), is sufficient to completely suppress the defects in synaptic vesicle recycling of BicD mutants; (3) the requirement for BicD and dynein in synaptic vesicle recycling mirrors the requirement for high rates of clathrin-mediated membrane retrieval; (4) synaptic vesicle diameter and synaptic bouton number are increased in BicD mutants, reminiscent of when components of the machinery for clathrin-mediated endocytosis are mutated (Zhang et al, 1998; Koh et al, 2004, 2007; Dickman et al, 2005, 2006); and (5) despite extensive efforts, we have been unable to find any factor other than Chc that is mislocalised in BicD mutant synapses; the factors tested include markers of membrane compartments (Hrs, Rabs 5, 6, 7 and 11), active zones (nc82) and synaptic vesicles (Vglut, Csp and Synaptotagmin (Syt) (Figure 4D; Supplementary Figure S4A and S4A′).

How might a BicD–Chc interaction contribute to efficient synaptic membrane recycling? It seems unlikely that BicD has a direct role in stimulating clathrin-mediated internalisation of the plasma membrane because BicD, unlike several components of the clathrin-mediated endocytic machinery (Roos and Kelly, 1999; Koh et al, 2004, 2007; Marie et al, 2004; Dickman et al, 2005), is not enriched within periactive zones. BicD accumulates predominantly beneath these zones and the overlap of Chc and BicD puncta can occur even more internally within the bouton. These observations also suggest that BicD does not have a critical role in uncoating of clathrin from synaptic vesicles, which occurs very shortly after scission from the plasma membrane (Miller and Heuser, 1984; Mueller et al, 2004). Consistent with this notion, an accumulation of densely coated vesicles, indicative of uncoating defects in NMJ synapses of other mutants (Verstreken et al, 2002, 2003), was not detectable in electron micrographs of either resting or stimulated BicD mutant synapses.

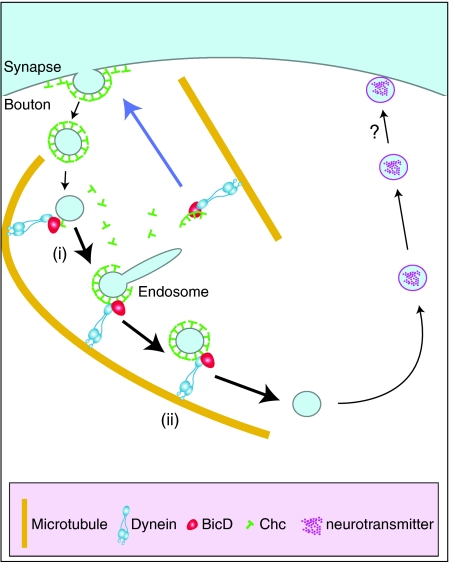

One possibility is that BicD augments dynein-based transport of clathrin that has disassociated from internalised vesicles back to the plasma membrane (Heuser and Reese, 1973) (Figure 9). This could account for two observations in the BicD mutants: the partially reduced concentration of Chc at periactive zones and the lack of co-localisation of internally accumulated Chc with clathrin adaptor proteins and markers of membrane compartments tested (AP180, α-adaptin/AP2, Hrs and Rab5; X Li, unpublished observations). Reduced levels of available clathrin can compromise the ability to sustain high rates of membrane uptake (Zhao et al, 2001). Thus, rates of Chc recycling to the plasma membrane in BicD and Dhc mutants may not be limiting during low-frequency stimulation, but may be unable to maintain sufficient levels of plasma membrane clathrin during bouts of intense stimulation. Recent studies in Drosophila synapses show that the membrane internalised in the absence of clathrin function is greatly increased in size and is not competent for recycling (Heerssen et al, 2008; Kasprowicz et al, 2008). Thus, a partial decrease in clathrin availability at the plasma membrane could conceivably contribute to the subtle increase in vesicle diameter and the inefficient recycling of pre-internalised membrane in BicD mutants. Alternatively, the internally mislocalised Chc in BicD mutants may interfere with normal sorting or maturation of synaptic vesicles by acting at ectopic sites or by sequestering important, as-of-yet unidentified, co-factors. Sequestration of clathrin co-factors could also account for changes in the diameter of nascent clathrin-coated vesicles in the mutants.

Figure 9.

Hypothetical models for the role(s) of BicD in synaptic vesicle recycling. BicD recognises synaptic vesicles during the time they are associated with clathrin and mediates their efficient recycling (black arrows) by facilitating a dynein-based transport step on microtubules. Thicker black arrows point to steps where we envisage BicD could have a rate-limiting role: transport of (i) pre-endosomal vesicles, because of only partial uncoating of clathrin from vesicles (He et al, 2008), or (ii) clathrin-coated vesicles budded from endosomal structures. Blue arrow: BicD/dynein delivers non-membrane-associated clathrin back to the plasma membrane. Inhibiting this process could conceivably slow the rate of vesicle translocation indirectly (see text for details). As shown in Table I, the number of vesicles docked with the active zone membrane after high-frequency stimulation is reduced in BicD mutants. We cannot rule out a direct role of BicD, possibly independently of clathrin, in promoting docking of exocytic vesicles with the plasma membrane (?). However, we judge this scenario to be unlikely given that BicD protein is enriched in proximity to periactive zones and not active zones. Instead, the reduction in the number of docked vesicles after intense stimulation is likely to be an indirect consequence of BicD's earlier role in augmenting the rate of translocation and/or maturation of vesicles (see text for details).

Another possibility, which is by no means mutually exclusive, is that the ability of BicD to stimulate Chc transport on microtubules could directly augment translocation of recycling membrane during the time it is associated with clathrin (Figure 9) (note that recent EM tomography studies in non-neuronal cells suggest that an incomplete uncoating reaction leads to the retention of some clathrin on vesicles until the exocytic event (He et al, 2008)). Once again, such a kinetic requirement for BicD may only be limiting when there is a demand for a rapid rate of membrane recycling. BicD–Chc could potentially have a role in a process analogous to the microtubule-based pre-endosomal sorting process operating shortly after internalisation in other cell types (Lakadamyali et al, 2006). Alternatively, BicD might recognise Chc associated with endosomal structures (Stoorvogel et al, 1996). Indeed, dynein has a key role in non-neuronal cells in the sorting and subsequent transport of specific subsets of endosomal vesicles (Driskell et al, 2007). Long-term experiments in neuronal and non-neuronal cells will be needed to resolve to what extent BicD participates in motor complexes that directly transport different post-endocytic intermediates, and the involvement of the interaction of BicD with Chc in these events. Future studies will also test directly the contribution of the interaction with Chc to other BicD-dependent processes, including sculpting of NMJ morphology.

Materials and methods

See Supplementary data for additional Materials and methods.

Drosophila strains and transgenics

Zygotic BicD null larvae are trans-heterozygous for a BicD null allele (r5) that introduces a translational stop after codon 50 of 782 (Ran et al, 1994) and a deletion that removes the entire BicD locus (Df119). Other genes removed by the deletion do not contribute to BicDr5/BicDDf119 mutant phenotypes as wild-type BicD transgenes are able to fully suppress the defects observed (Figures 1A–C and 7F). Dhc zygotic mutant larvae are trans-heterozygous for a null allele (4–19) and a hypomorphic allele (6–10). Null mutant Dhc animals do not develop to third instar stage. A description of other chromosomes, mutant alleles and GAL4 drivers can be found at Flybase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). Transgenic animals were made as described in Supplementary Materials and methods using established methods for P-element-mediated transformation. Inserts of all constructs were sequenced before transformation to ensure that no mutations had arisen during the cloning procedures.

Live imaging of boutons and egg chambers

Third instar larvae were dissected with the central nervous system left intact and mounted in Ca2+-free saline to limit muscle contraction. Ovarioles were dissected on a coverslip in Voltalef 9S oil (VWR) and teased apart so that they adhered to the glass. NMJs and germaria were imaged at 22°C using a spinning disk UltraVIEW ERS confocal microscope (PerkinElmer) using a × 100/1.4 or x63/1.4 NA oil-immersion PlanApo Olympus objective, respectively. Image series were captured during the first 30 min after dissection using an Orca ER CCD camera (Hamamatsu). For the real-time analysis of Chc dynamics, particles in large boutons (longest axis >3.5 μm) were analysed manually using Image J and Ultraview ERS software. Particle motion was classified as described in the legends to Figure 5B.

Solutions

The composition of normal saline was 130 mM NaCl, 36 mM sucrose, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.3). Ca2+-free saline was normal saline with CaCl2 replaced by 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM EGTA. The composition of HL3 medium, unless stated otherwise, was 70 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM trehalose, 115 mM sucrose and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.3).

Electrophysiology

Third instar larval fillets were mounted in HL3 medium. Recordings were made from muscles 6 and 7 from segments 3 and 4 using glass microelectrodes filled with 4 M potassium acetate. The electrode resistance was usually between 20 and 40 MΩ. To evoke synaptic potentials, stimulating pulses were delivered to an appropriate segmental nerve through a glass suction electrode for 1 ms at 1.5–2 times the threshold for maximum synaptic response. Cells with a resting potential between 55 and 65 mV during the entire recording period were selected. shits preparations were incubated at 32°C in HL3 medium for 10 min before recording synaptic potentials. Temperature was maintained using a microwarm plate (Kitazato, Japan).

FM dye experiments

Third instar larval fillets, with axons severed to avoid spontaneous stimuli, were washed three times and mounted in normal saline. For assessing membrane uptake, fillets were incubated with 10 μM FM 1-43 dye (Invitrogen) in normal saline in conjunction with electrical stimulation, as described earlier (Kuromi and Kidokoro, 1998). After loading, FM dye that was not internalised was removed by three washes in Ca2+-free buffer and NMJs were imaged with an epifluorescence microscope and a CCD camera. Pre-internalised dye was unloaded in the absence of external dye with high K+ saline, followed by imaging of the same boutons previously assayed for loading. Fluorescence intensity in the boutons was measured after subtraction of the background intensity. For each preparation, fluorescence intensity of 10–15 boutons on muscles 6 and 7 of segment A4 was measured and averaged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the many researchers who kindly provided reagents. We are also grateful to Meg Stark of the York Technology facility for contributing to the TEM analysis, Florian Boehl for providing BicD yeast two-hybrid constructs and advice, Jerry Wu for help with image analysis, the de Bono laboratory for help with locomotion assays, Farida Begum and Sew-Yeu Peak Chu for mass spectrometry and members of the Bullock group, Leon Lagnado, Harvey McMahon, Christien Merrifield, Ben Nichols and Cahir O'Kane for discussions or comments on the paper. This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (core funding (XL and SLB) and project grant G0400580 (LB and SS)), a EU Framework Program 5 grant to Cahir O'Kane (QLG3-CT-2001-01181; JR) and grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (18300131;HK). JR thanks Cahir O'Kane for support. SB is a Lister Institute Prize fellow.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Betz WJ, Bewick GS (1992) Optical analysis of synaptic vesicle recycling at the frog neuromuscular junction. Science 255: 200–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SL, Ish-Horowicz D (2001) Conserved signals and machinery for RNA transport in Drosophila oogenesis and embryogenesis. Nature 414: 611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SL, Nicol A, Gross SP, Zicha D (2006) Guidance of bidirectional motor complexes by mRNA cargoes through control of dynein number and activity. Curr Biol 16: 1447–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen M, Suter B (2005) BicD-dependent localization processes: from Drosophilia development to human cell biology. Ann Anat 187: 539–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Horne JA, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL (2005) A slowed classical pathway rather than kiss-and-run mediates endocytosis at synapses lacking synaptojanin and endophilin. Cell 123: 521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL (2006) Altered synaptic development and active zone spacing in endocytosis mutants. Curr Biol 16: 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstbier M, Boehl F, Li X, Bullock SL (2009) Egalitarian is a selective RNA-binding protein linking mRNA localization signals to the dynein motor. Genes Dev 23: 1546–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstbier M, Li X (2009) Bicaudal-D and its role in cargo sorting by microtubule-based motors. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 1066–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell OJ, Mironov A, Allan VJ, Woodman PG (2007) Dynein is required for receptor sorting and the morphogenesis of early endosomes. Nat Cell Biol 9: 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton BA, Fetter RD, Davis GW (2002) Dynactin is necessary for synapse stabilization. Neuron 34: 729–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad H, Ringstad N, Low P, Kjaerulff O, Gustafsson J, Wenk M, Di Paolo G, Nemoto Y, Crun J, Ellisman MH, De Camilli P, Shupliakov O, Brodin L (2000) Fission and uncoating of synaptic clathrin-coated vesicles are perturbed by disruption of interactions with the SH3 domain of endophilin. Neuron 27: 301–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepner J, Li M, Ludmann S, Kortas C, Boylan K, Iyadurai SJ, McGrail M, Hays TS (1996) Cytoplasmic dynein function is essential in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 142: 865–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev I, Splinter D, Keijzer N, Wulf PS, Demmers J, Ohtsuka T, Modesti M, Maly IV, Grosveld F, Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A (2007) Rab6 regulates transport and targeting of exocytotic carriers. Dev Cell 13: 305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guichet A, Wucherpfennig T, Dudu V, Etter S, Wilsch-Brauniger M, Hellwig A, Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Huttner WB, Schmidt AA (2002) Essential role of endophilin A in synaptic vesicle budding at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. EMBO J 21: 1661–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner C, Di Paolo G, Rosenthal JA, de Camilli P (2000) Direct interaction of the 170 kDa isoform of synaptojanin 1 with clathrin and with the clathrin adaptor AP-2. Curr Biol 10: 471–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Ladinsky MS, Huey-Tubman KE, Jensen GJ, McIntosh JR, Bjorkman PJ (2008) FcRn-mediated antibody transport across epithelial cells revealed by electron tomography. Nature 455: 542–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerssen H, Fetter RD, Davis GW (2008) Clathrin dependence of synaptic-vesicle formation at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Curr Biol 18: 401–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser JE, Reese TS (1973) Evidence for recycling of synaptic vesicle membrane during transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol 57: 315–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Howell SA, Dortland BR, De Zeeuw CI, Willemsen R, Visser P, Grosveld F, Galjart N (2001) Mammalian Golgi-associated Bicaudal-D2 functions in the dynein-dynactin pathway by interacting with these complexes. EMBO J 20: 4041–4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Wulf P, Schiefermeier N, Stepanova T, Galjart N, Small JV, Grosveld F, de Zeeuw CI, Akhmanova A (2003) Bicaudal D induces selective dynein-mediated microtubule minus end-directed transport. EMBO J 22: 6004–6015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januschke J, Nicolas E, Compagnon J, Formstecher E, Goud B, Guichet A (2007) Rab6 and the secretory pathway affect oocyte polarity in Drosophila. Development 134: 3419–3425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprowicz J, Kuenen S, Miskiewicz K, Habets RL, Smitz L, Verstreken P (2008) Inactivation of clathrin heavy chain inhibits synaptic recycling but allows bulk membrane uptake. J Cell Biol 182: 1007–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki F, Mattiuz AM, Ordway RW (1998) Synaptic physiology and ultrastructure in comatose mutants define an in vivo role for NSF in neurotransmitter release. J Neurosci 18: 10241–10249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JH, Ikeda K (1989) Disappearance and reformation of synaptic vesicle membrane upon transmitter release observed under reversible blockage of membrane retrieval. J Neurosci 9: 3844–3860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TW, Korolchuk VI, Wairkar YP, Jiao W, Evergren E, Pan H, Zhou Y, Venken KJ, Shupliakov O, Robinson IM, O'Kane CJ, Bellen HJ (2007) Eps15 and Dap160 control synaptic vesicle membrane retrieval and synapse development. J Cell Biol 178: 309–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TW, Verstreken P, Bellen HJ (2004) Dap160/intersectin acts as a stabilizing scaffold required for synaptic development and vesicle endocytosis. Neuron 43: 193–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromi H, Kidokoro Y (1998) Two distinct pools of synaptic vesicles in single presynaptic boutons in a temperature-sensitive Drosophila mutant, shibire. Neuron 20: 917–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Zhuang X (2006) Ligands for clathrin-mediated endocytosis are differentially sorted into distinct populations of early endosomes. Cell 124: 997–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KS, Xu J, Cermelli S, Shu Z, Gross SP (2008) BicaudalD actively regulates microtubule motor activity in lipid droplet transport. PLoS ONE 3: e3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton JT, Chapman ER, Kreber R, Garment MB, Carlson SD, Ganetzky B (1998) Temperature-sensitive paralytic mutations demonstrate that synaptic exocytosis requires SNARE complex assembly and disassembly. Neuron 21: 401–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach JM, Lehmann R (1997) An Egalitarian-BicaudalD complex is essential for oocyte specification and axis determination in Drosophila. Genes Dev 11: 423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahr A, Aberle H (2006) The expression pattern of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter: a marker protein for motoneurons and glutamatergic centers in the brain. Gene Expr Patterns 6: 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie B, Sweeney ST, Poskanzer KE, Roos J, Kelly RB, Davis GW (2004) Dap160/intersectin scaffolds the periactive zone to achieve high-fidelity endocytosis and normal synaptic growth. Neuron 43: 207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Iyadurai SJ, Gassman A, Gindhart JG Jr, Hays TS, Saxton WM (1999) Cytoplasmic dynein, the dynactin complex, and kinesin are interdependent and essential for fast axonal transport. Mol Biol Cell 10: 3717–3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matanis T, Akhmanova A, Wulf P, Del Nery E, Weide T, Stepanova T, Galjart N, Grosveld F, Goud B, De Zeeuw CI, Barnekow A, Hoogenraad CC (2002) Bicaudal-D regulates COPI-independent Golgi-ER transport by recruiting the dynein-dynactin motor complex. Nat Cell Biol 4: 986–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TM, Heuser JE (1984) Endocytosis of synaptic vesicle membrane at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol 98: 685–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mische S, Li M, Serr M, Hays TS (2007) Direct observation of regulated ribonucleoprotein transport across the nurse cell/oocyte boundary. Mol Biol Cell 18: 2254–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead AR, Rzomp KA, Scidmore MA (2007) The Rab6 effector Bicaudal D1 associates with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions in a biovar-specific manner. Infect Immun 75: 781–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller VJ, Wienisch M, Nehring RB, Klingauf J (2004) Monitoring clathrin-mediated endocytosis during synaptic activity. J Neurosci 24: 2004–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoulas O, Hays TS, Sisson JC (2005) The golgin Lava lamp mediates dynein-based Golgi movements during Drosophila cellularization. Nat Cell Biol 7: 612–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson C, Eaton BA, Davis GW (2008) Formin-dependent synaptic growth: evidence that Dlar signals via Diaphanous to modulate synaptic actin and dynamic pioneer microtubules. J Neurosci 28: 11111–11123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse BM, Robinson MS (1990) Clathrin, adaptors, and sorting. Annu Rev Cell Biol 6: 151–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poskanzer KE, Fetter RD, Davis GW (2006) Discrete residues in the c(2)b domain of synaptotagmin I independently specify endocytic rate and synaptic vesicle size. Neuron 50: 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran B, Bopp R, Suter B (1994) Null alleles reveal novel requirements for Bic-D during Drosophila oogenesis and zygotic development. Development 120: 1233–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringstad N, Gad H, Low P, Di Paolo G, Brodin L, Shupliakov O, De Camilli P (1999) Endophilin/SH3p4 is required for the transition from early to late stages in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Neuron 24: 143–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, Hummel T, Ng N, Klambt C, Davis GW (2000) Drosophila Futsch regulates synaptic microtubule organization and is necessary for synaptic growth. Neuron 26: 371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, Kelly RB (1999) The endocytic machinery in nerve terminals surrounds sites of exocytosis. Curr Biol 9: 1411–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliwa M, Woehlke G (2003) Molecular motors. Nature 422: 759–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster CM, Davis GW, Fetter RD, Goodman CS (1996) Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. I. Fasciclin II controls synaptic stabilization and growth. Neuron 17: 641–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer FE, Ryan TA (2006) The synaptic vesicle: cycle of exocytosis and endocytosis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16: 298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short B, Preisinger C, Schaletzky J, Kopajtich R, Barr FA (2002) The Rab6 GTPase regulates recruitment of the dynactin complex to Golgi membranes. Curr Biol 12: 1792–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubeita GT, Tran SL, Xu J, Vershinin M, Cermelli S, Cotton SL, Welte MA, Gross SP (2008) Consequences of motor copy number on the intracellular transport of kinesin-1-driven lipid droplets. Cell 135: 1098–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoorvogel W, Oorschot V, Geuze HJ (1996) A novel class of clathrin-coated vesicles budding from endosomes. J Cell Biol 132: 21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken P, Kjaerulff O, Lloyd TE, Atkinson R, Zhou Y, Meinertzhagen IA, Bellen HJ (2002) Endophilin mutations block clathrin-mediated endocytosis but not neurotransmitter release. Cell 109: 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken P, Koh TW, Schulze KL, Zhai RG, Hiesinger PR, Zhou Y, Mehta SQ, Cao Y, Roos J, Bellen HJ (2003) Synaptojanin is recruited by endophilin to promote synaptic vesicle uncoating. Neuron 40: 733–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken P, Ly CV, Venken KJ, Koh TW, Zhou Y, Bellen HJ (2005) Synaptic mitochondria are critical for mobilization of reserve pool vesicles at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron 47: 365–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmaier SM, Kam K, Yang H, Fortin DL, Hua Z, Nicoll RA, Edwards RH (2006) Distinct endocytic pathways control the rate and extent of synaptic vesicle protein recycling. Neuron 51: 71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Durrbeck H, Buchner S, Dabauvalle MC, Schmidt M, Qin G, Wichmann C, Kittel R, Sigrist SJ, Buchner E (2006) Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron 49: 833–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Broadie K (2007) In vivo assay of presynaptic microtubule cytoskeleton dynamics in Drosophila. J Neurosci Methods 162: 198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Koh YH, Beckstead RB, Budnik V, Ganetzky B, Bellen HJ (1998) Synaptic vesicle size and number are regulated by a clathrin adaptor protein required for endocytosis. Neuron 21: 1465–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]