Abstract

The aim of this study was to obtain a greater insight into the association between vacations and happiness. We examined whether vacationers differ in happiness, compared to those not going on holiday, and if a holiday trip boosts post-trip happiness. These questions were addressed in a pre-test/post-test design study among 1,530 Dutch individuals. 974 vacationers answered questions about their happiness before and after a holiday trip. Vacationers reported a higher degree of pre-trip happiness, compared to non-vacationers, possibly because they are anticipating their holiday. Only a very relaxed holiday trip boosts vacationers’ happiness further after return. Generally, there is no difference between vacationers’ and non-vacationers’ post-trip happiness. The findings are explained in the light of set-point theory, need theory and comparison theory.

Keywords: Happiness, Holiday stress, Quality of life, Subjective well-being, Tourism

Introduction

Tourism

A characteristic of post-industrial societies is that the majority of people in them practice tourism (Bell 1973). Tourism is evolving into one of the most important industries worldwide. The percentage of vacationers is ever increasing; the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) predicts 1.6 billion international arrivals by the year 2020 (UNWTO 2008). In addition, trip frequency has increased considerably over people’s lifespan (Opperman 1995) and there is a trend to take more than one holiday per year.

Vacationers who have a history of past tourism experiences in a certain destination, or who take similar types of holidays regularly, are better capable of matching their wants to their needs (Ryan 1998). This implies that tourists may become increasingly able to derive benefit from their holidays in terms of fulfillment, enjoyment and happiness.

Tourism is generally regarded as an activity which allows for an escape from the routine of daily life (Prentice 2004). Gross (1961) argued that tourists’ escape is a time-out, much needed for healthy functioning in society. Thus, Gross regards holiday trips as an experience needed to cope with daily life after a holiday trip. Boorstin (1964) and MacCannell (1976) argued that people generally live alienated inauthentic lives, and that during their holiday trip they strive to escape to a more satisfying life. These views seem outdated nowadays and have been replaced by more postmodern views of tourism (Uriely 2005). The distinction between tourism and everyday life is not as clear anymore as it perhaps once was. Leisure, tourism and everyday life have become a much more integral part of life (Larsen 2008; McCabe 2002) because experiences that were once confined to tourism, are now accessible in everyday life (Lash and Urry 1994).

Happiness

The subject of happiness has been a “playground for speculative philosophy” for hundreds of years (Veenhoven 2009, p. 45), but is currently also being studied empirically by the social sciences. This type of research took off in the 1970s and has been thriving recently, partly due to the popularity of positive psychology. These studies conclude that life is getting better (Veenhoven and Hagerty 2006) and that most people are happy in modern society (Diener and Diener 1996). However, not all changes in society imply progress in terms of happiness. For instance, increased consumption does not automatically lead to greater happiness and may even reduce happiness through demoralization of society (Myers 2000), stress and income differences (Easterbrook 2003), over-consumption (Easterbrook 2003; Schor 1998) and over-worked or burnt-out employees (Easterbrook 2003; Schor 1991).

Several quality of life theories offer insight into happiness. Comparison theory states that we judge the quality of our lives mainly by estimating the gap between the realities of our lives and common standards of the good. In this view, happiness largely involves keeping up with the Joneses. Set-point theory argues that happiness is a rather stable ‘trait’ and that whatever we do, we cannot change our happiness much. In this view, particular experiences can at best provide a temporary uplift, after which we return to our set-point (Cummins 2005; Veenhoven 2006). Finally, need theory emphasizes that happiness is more a reflection of how we generally feel and an indicator of whether certain needs are gratified (Veenhoven 2006). In this view, experiences add to happiness only if they involve need gratification.

The findings of the current study may contribute to an explanation of how vacationing adds to greater happiness of individuals, in the light of the above-mentioned quality of life theories.

Tourism and Happiness

Previous studies have provided data about the effect of holiday trips on happiness, including the role of length of stay.

Holiday Trips

A few cross-sectional studies find weak positive associations between holiday trips and happiness (Kemp et al. 2008; Milman 1998; Neal 2000). Three pre-test/post-test design studies (Hoopes and Lounsbury 1989; Lounsbury and Hoopes 1986; Strauss-Blasche et al. 2000) analyzed the impact of time off from work, which may, or may not have, included a holiday trip. Just one pre-test/post-test design study focused exclusively on holiday trips. It measured the impact of a holiday trip on tourists’ post-trip happiness (Gilbert and Abdullah 2004). Generally, the impact of a holiday on post-trip life satisfaction is small (De Bloom et al. 2009).

Positive effects of a holiday do not last very long. Westman and Eden (1997) and Westman and Etzion (2001) found that people who suffer from burnout returned to pre-vacation levels by the time of their second measurement, three (Westman and Eden 1997) to four weeks (Westman and Etzion 2001) after the respite from work had ended. Another study (Strauss-Blasche et al. 2000) reported that improvement in mood and quality of sleep lasted only up to five weeks. Gilbert and Abdullah’s (2004) post-trip assessment period spanned a period of two to six months. They found that vacationers, compared to non-vacationers, experienced a higher amount of pleasant feelings after their holidays, but found no differences in post-trip happiness between the three periods they distinguished.

Holiday Stress

Holiday trips are not merely pleasant experiences. Quite a few studies report a series of health problems, such as homesickness, associated with vacationing (Kop et al. 2003; Pearce 1981; Van Heck and Vingerhoets 2007; Vingerhoets et al. 1997 In addition to health problems, vacationers report many worries during their holiday (Larsen et al. 2009) and some experience relational problems (Ryan 1991) or a culture shock (Pearce 1981). However, the association between holiday stress and post-trip happiness has not been investigated yet. Intuitively, it is plausible that when one experiences a holiday with a lot of stress, this would lead to lower feelings of happiness.

Length of Stay

The role of length of stay is not yet clear at this time. Neal (2000) concludes that length of stay moderates several of the relationships in her model. A follow-up study by Neal and Sirgy (2004) finds a moderating effect of length of stay between holiday satisfaction and happiness. However, Gilbert and Abdullah (2004), Lounsbury and Hoopes (1986) and Kemp et al. (2008) found no association between length of stay and post-trip happiness.

Questions

In conclusion, a literature review reveals many positive feelings to be associated with holiday trips, but does not inform us whether vacationers are happier in general. Research findings until now suggest that a time off from work does not boost happiness much afterwards. We currently do not know whether this is the case for holiday trips; the single study on post-trip happiness, until now, used rather crude time intervals (Gilbert and Abdullah 2004). Finally, studies to date have yielded inconsistent empirical evidence concerning the importance of the factor length of stay.

This study adds to this literature by attempting to answer the following questions:

(1) Are vacationers happier compared to non-vacationers? (2) Does a holiday trip boost happiness? (3) If a holiday trip boosts happiness, then for how long does this effect last? and (4) What are the roles of length of stay and holiday stress?

Method

Respondents

The sample consists of 1,530 respondents. 52% are men. Mean age is 50 (SD = 16) and mean monthly net income is €2,420 (SD = 1,810). Most respondents hold a graduate or undergraduate degree (35%), have a paid job (51%) or are retired (21%). 74% is either married or cohabiting.

All respondents are members of the CentERdata Databank, who made the data for this study available to us. CentERdata is a research institute, which is part of Tilburg University in the Netherlands.

The CentERpanel is composed of well over 2,000 households, completing online questionnaires at home every week, and this panel is considered a representative sample of the Dutch-speaking population. Households without Internet access are given a device called a Net.Box, which allows them to enter data on the Internet, using their televisions as screens. We make use of 2006 data from the health monitor, which is a questionnaire that is administered to CentERpanel members every eight weeks.

The questionnaire of week 35 of that year contained questions about respondents’ holiday trip, if they had made any. The day of departure and day of return differed. The holiday trip began at some point in time between week 27 and week 35. The questionnaires of week 11, 19 and 43 were also available to us.

Variables

Happiness

Our focus was on ‘hedonic level of affect’, which Veenhoven (1984) considers the ‘affective dimension’ of happiness. Hedonic level of affect can be measured using an Affect Balance Score (ABS), such as PANAS (Watson et al. 1988), which has also been applied previously in several tourism studies (Gilbert and Abdullah 2002, 2004; Milman 1998). The ABS used in this study was derived from responses to three questions, one positively formulated item and two negative ones. The mean score of the two negative items was deducted from the positive item. The positive item measured whether respondents had recently ‘enjoyed their daily tasks’. The two negative statements evaluated whether respondents had recently felt ‘unhappy’, and ‘gloomy and dejected’. Possible answers were “never”, “almost never”, “sometimes”, “very often” and “always”.

Type of Holiday

Two groups were distinguished of, respectively, non-vacationers and vacationers. The first group (n = 556) did not go on a holiday, they continued their everyday life. The second group (n = 974) consisted of vacationers who started their holiday trip between week 27 and week 35. A holiday trip is defined as a trip where people are traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for no longer than one year and specifically for leisure purposes (UNWTO 2002).

Length of Stay

To determine how long a holiday trip had lasted, respondents had to answer the following question: “How long did your holiday last?” The response alternatives were “less than 5 days”, “5–8 days”, “9–14 days”, “15–21 days” and “more than 21 days”.

Holiday Stress

A question on the respondents’ level of experienced stress during their holiday trip was included in the questionnaire. The exact question was: “How did you experience your holiday elsewhere?” The response alternatives were “very stressful”, “stressful”, “neutral”, “relaxed” and “very relaxed”.

Days Passed After Having Returned

The questionnaire also included a question on how many days had passed since the respondent had returned from his/her holiday trip. The response alternatives were “I am still on holiday”, “less than one week”, “less than two weeks”, “less than three weeks”, “less than four weeks”, “less than six weeks” and “less than eight weeks”.

Socio-demographic Variables

Educational level, net household income, employment status, age, and sex were all assessed.

Health Status

Respondents’ health status was measured by the number of sick days in the past month. Possible responses were “0 days”, “1 or 2 days”, “3–5 days”, “5–10 days” and “more than 10 days”.

Extraversion

A particular personality trait (McCrae and John 1992) which is moderately positively associated with happiness is extraversion (Diener et al. 1992; Pavot et al. 1990). Extraverts have an active leisure life (Brandstätter 1994), which may be associated with greater happiness (Brown et al. 1991). We had information on the respondents’ level of extraversion, which was measured in 2007 on a five-point scale. Even though this personality assessment took place a year later than the measured variables in this study, it was appropriate to use since personality traits are deemed to be relatively stable (Costa and McCrae 1994; Gustavsson et al. 1997; Hampson and Goldberg 2006; McCrae and Costa 2003; Terraciano et al. 2006). Our assumption is that extraverts are likely to take different types of holidays, compared to other individuals. Since we had no information on ‘type of holiday’, we controlled for extraversion.

Results

Are Vacationers Happier?

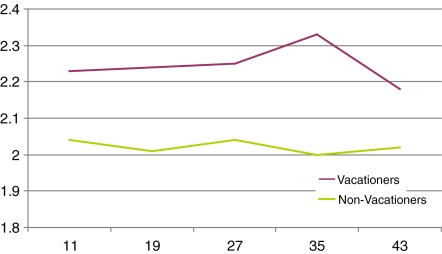

Figure 1 shows the happiness scores of vacationers (n = 974) and non-vacationers over time (n = 556). Vacationers display a higher degree of pre-trip as well as post-trip happiness. To test whether this difference in happiness is significant, we performed two one-way between groups multivariate analyses of covariance.

Fig. 1.

Mean happiness over time

Pre-trip Happiness

To determine the possible pre-trip happiness difference, three dependent variables were used: happiness levels of week 11, 19 and 27. As covariates we used socio-demographics, health status and extraversion. Preliminary assumption testing was conducted to check for normality, linearity, univariate and multivariate outliers, homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices, and multicollinearity, with no serious violations noted. There was a statistically significant difference between vacationers and those staying at home, F (3, 531) = 3.39, p = .018; Wilks’ Lambda = .98; η2 = .02. Vacationers have a significantly higher pre-trip happiness score (M = 2.25, SD = .08) compared to those not going on a holiday trip (M = 2.07, SD = .09).

Post-trip Happiness

Post-trip happiness comprised of two dependent variables, namely the happiness scores of week 35 and week 43. Again, preliminary assumption testing was conducted, with no violations noted. Vacationers still on holiday in week 35 (n = 142) were excluded from the analysis. This time we found no statistically significant difference in happiness between both groups, F (2, 783) = 2.00, ns.

Does a Holiday Trip Boost Happiness?

Post-trip Happiness Boost

A three-way between-groups multivariate analysis of covariance was performed to investigate differences in happiness. Happiness levels of week 35 and week 43 were the dependent variables. The independent variables were holiday stress, length of stay and days passed after having returned. None of the vacationers considered their holiday to be very stressful. Only 14 considered theirs stressful and 67 neutral. We grouped these two response categories and labeled this combined category ‘stressful or neutral’. Socio-demographics, health status and extraversion were used as covariates and vacationers still on holiday in week 35 were again excluded from the analysis. Preliminary assumption testing was conducted to check for normality, linearity, univariate and multivariate outliers, homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices, and multicollinearity. Since Box’s test of equality of variances was significant, we used Pillai’s Trace Criterion instead of Wilks’ Lambda. No other violations were observed. We found a statistically significant main effect of holiday stress on the combined post-trip happiness variable, F (4, 718) = 9.24, p ≤ .001; Pillai’s Trace = .10; η2 = .05. An inspection of the mean happiness scores indicated that vacationers who rated their holiday very relaxed (M = 2.64, SD = .10) or relaxed (M = 2.16, SD = .09) are happier than vacationers who rated their holiday as stressful or neutral (M = 1.07, SD = .22). We found no significant main effect for length of stay, F (8, 718) = 1.59, ns. There was also no significant main effect for days passed after having returned, F (10, 718) = .90, ns. The interaction effect between holiday stress and length of stay, F (16, 718) = 1.08, ns, and holiday stress and days passed after having returned, F (20, 718) = 1.19, ns, were both not statistically significant. Thus, holiday stress is negatively associated with post-trip happiness, whereas length of stay and the number of days passed after having returned fail to have a significant impact on it.

Fade-out

Happiness for the ‘relaxed’ group (n = 521) in week 27 is 2.27 (SD = 1.08). Their post-holiday happiness scores were all very similar to their happiness level in week 27, and did not significantly fluctuate. The ’very relaxed’ group had a pre-trip mean happiness score of 2.48 (SD = 1.26). This happiness level of this group slowly, but gradually, decreased, until it reached their pre-trip level at eight weeks after return, with significant higher post-trip happiness levels in the first two weeks of return. The subgroups for the stressful or neutral category were too small to draw any meaningful conclusions.

Discussion

Vacationers are Happier

Our study demonstrated that vacationers generally displayed greater pre-trip happiness than non-vacationers, although the differences were small. In contrast, post-trip happiness did not differ between vacationers and non-vacationers. Possibly, anticipation played an important role in explaining the observed differences in pre-trip happiness between vacationers and non-vacationers. Holiday trips are experiences which people look forward to (Miller et al. 2007). For most, the enjoyment starts weeks, even months before the holiday actually begins.

Remarkably, post-trip happiness is generally not different for vacationers and non-vacationers. However, holiday stress is associated with post-trip happiness.

Holidays Briefly Boost Post-trip Happiness

The benefits of a ’very relaxed’ holiday trip last maximally for two weeks. A relaxed holiday without stress is not only good for one‘s health (Gump and Matthews 2000; Vingerhoets et al. 1997; Westman and Etzion 2001), but is also important in terms of post-trip happiness. However, the relaxed group of vacationers does not draw any post-trip happiness benefits, which suggests a holiday has to be very relaxing in order to draw post-trip benefits, in terms of post-trip happiness.

Our study finds a similar fade-out gradient for happiness as De Bloom et al. (2009) reported in their meta-analysis on post-trip health. It is not surprising that a holiday trip does not have a prolonged effect on happiness, since most vacationers have to return to work or other daily tasks and consequently fall back into their normal routine fairly quickly.

Additionally, this study demonstrates that length of stay is not associated with post-trip happiness. This contradicts Neal (2000) and Neal and Sirgy‘s (2004) findings, but supports the findings of Gilbert and Abdullah (2004), Lounsbury and Hoopes (1986) and Kemp et al. (2008). Our data confirm that returning home involves a swift return to pre-trip happiness levels, independent of the duration of the trip. As long as the holiday trip itself provides sufficient opportunity to relax and reduce stress, there should be no reason for any differences in post-trip happiness, regardless of how many days are spent on holiday.

Quality of Life Theories

How do these findings fit the three theories of quality of life, as mentioned in the introduction section? Set-point theory cannot explain the pre-trip high very well, but adequately predicts that the holiday uplift is short-lived or even absent. Need theory can explain the pre-trip high if one assumes that we have an innate need for wandering, possibly a leftover of our hunter-gatherer past and that this need can already be partially gratified by anticipation. In this theory, the absence of a post-trip boost could be due to saturation. Another possible explanation is that the non-vacationers, or their travel partner(s), feel temporarily less happy and therefore do not have the need for a holiday. However, this does not explain the absence of differences in post-trip happiness between vacationers and non-vacationers very well. The need for status could possibly explain our findings also. Comparison theory would suggest that social comparison is involved and that people who anticipate a holiday feel to be better off than those who intend to stay at home. The absence of a post-trip happiness difference between vacationers and non-vacationers can be explained from a comparison theory perspective as well. The holiday is over and vacationers are no longer different from non-vacationers, which would explain the similar happiness levels.

Implications

The findings of our study suggest several managerial, policy and individual implications.

From an individual point of view, vacationing is something which is looked forward to. However, the length of such a vacation does not matter in terms of post-trip happiness. This suggests that people derive more happiness from two or more short breaks spread throughout the year, than from having just a single longer holiday once a year.

This brings us to the policy implications. In order for families to stagger their holiday time throughout the year, the school system would have to become more flexible. Some countries have rather lengthy summer holidays, leaving little time for short additional vacations in the rest of the year. This poses a constraint to families with school-going children in particular. However, as Butler (2001) suggests, changing the long summer school holiday may not have the desired effect; tourists for example attach much value to the weather condition and in addition, host communities may not be so keen to have tourists all year round.

From a managerial perspective we would advise tourism managers to provide holiday products, with a minimum amount of stress-inducing aspects. Obviously, companies do not purposely create stressful holiday services. However, certain experiences may enhance stress and should be avoided as much as possible. An example of such a stressful experience is waiting in line at a theme park or cuing at the entrance to a museum. These clearly are examples of rather mildly stressful experiences. Nonetheless, when waiting in line for attractions at a theme park, in the heat, accompanied by impatient young children, such mildly stressful experiences could easily evolve into much more stressful events. Several methods to reduce the negative effects of waiting lines exist (Kostecki 1996); the tourism industry should use these approaches to greater extent. Another example of a stress-inducing aspect of certain holidays is long haul air travel. Several aspects of air travel contribute to stress (Stokes and Kite 1994). Jet lag is an all too familiar phenomenon among air travelers. Long haul air travel may also cause health problems, such as a cold, which could turn into a painful and stressful experience at high altitudes (Vingerhoets et al. 1997). However, information on how to reduce jet lag or prevent other health issues is not always clearly communicated by airlines and tour operators.

Specific stress-factors aside, managers should generally go out of their way to create holiday packages which are very relaxing, as very relaxed holidays boost post-trip happiness. The increased attention for spa, health and wellness tourism (Smith and Puckó 2009) may be a sign that the tourism industry is already attending to this increasing need.

Future Research

We had no information about the type of holidays, or the type of activities these vacationers engaged in during their trip. Even though we know that ‘very relaxed’ holidays are the most favorable in terms of post-trip happiness, we do not know whether certain types of holidays or certain types of holiday activities are considered ‘very relaxed’ more so than others. If stressful holidays do not increase post-trip happiness, then why are there still so many active holiday packages being purchased? The answer probably lies in finding the right person-environment fit. Sensation-seekers and extraverts could benefit from vacationing in different ways than other vacationers. These matters should be explored in future research.

From the point of view of comparison theory, vacationing may possibly lower post-trip happiness when vacationers encounter richer tourists at exclusive, expensive resorts and luxurious hotels. Vacationers may also be confronted with extreme poverty in more exotic, but poor, destinations. Future research is needed to assess how frequently such confrontations take place and if they affect vacationers’ post-trip happiness.

Post-trip, the possible effect of holiday satisfaction (Lounsbury and Hoopes 1986; Westman and Eden 1997) and its relation to holiday stress as a moderator of post-trip happiness requires further investigation.

Specific attention must be paid to the recollection phase of a holiday trip (Clawson and Knetsch 1966), which involves savoring the holiday experience (Bryant and Veroff 2007) through reminiscing of past holiday events (Morgan and Xu 2009). Selective retention, selective recall (Hickson III and Beck 2008) and a rosy view (Mitchell et al. 1997) can potentially enhance the positive effects of a holiday trip. These processes could add to greater happiness of vacationers. More research is needed to address these phenomena.

Finally, additional research is also needed to further assess the impact of anticipation of a holiday trip (Parrinello 1993) on vacationers‘ pre-trip happiness. Moreover, the duration of such a possible uplift in pre-trip happiness needs to be assessed. Holiday expectation (Gilbert and Abdullah 2002; Gnoth 1997) and homesickness (Van Tilburg et al. 1996) could be assessed for possible moderating effects.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that vacationers are happier, compared to non-vacationers, but a holiday trip does not add much to their happiness. Generally, there were no differences between vacationers‘ and non-vacationers‘ post-trip happiness. Only vacationers on a ‘very relaxed’ holiday trip benefit in terms of post-trip happiness. The pre-trip happiness difference between vacationers and non-vacationers could be an indication of vacationers looking forward to their holiday.

We tried to explain these findings in the light of the three quality of life theories, as mentioned in the introduction section. Comparison theory and need theory explain our findings best. Comparison theory explains the pre-trip difference well, assuming that social comparison is involved and that people who anticipate a vacation, feel better off than non-vacationers. Generally, once the holiday is over, vacationers are no happier than non-vacationers because the holiday is over and vacationers are, in that sense, equal to non-vacationers. If one assumes that we have an innate need for wandering, and that this need is fulfilled by taking a holiday trip, then need theory explains the pre-trip difference rather well. Furthermore, assuming that saturation takes place, need theory would also explain the absence of a post-trip happiness boost for most tourists.

References

- Bell D. The coming of post-industrial society: A venture in social forecasting. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Boorstin D. The image: A guide to pseudo-events in america. New York: Harper; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter H. Pleasure of leisure-pleasure of work: personality makes the difference. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16(6):931–946. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90236-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BA, Frankel GB, Fennell M. Happiness through leisure: the impact of type of leisure activity, age, gender and leisure satisfaction on psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Recreation Research. 1991;16(4):368–392. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Veroff J. Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Butler RW. Seasonality in tourism: Issues and implications. In: Baum T, Lundtorp S, editors. Seasonality in tourism. Kindlington: Pergamon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Clawson M, Knetsch JL. Economics of outdoor recreation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In: Heatherton TF, Weinberger JL, editors. Can personality change? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books; 1994. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins RA. Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(10):699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J, Kompier M, Geurts S, Weerth C, Taris T, Sonnentag S. Do we recover from vacation? Meta-analysis of vacation effects on health and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health. 2009;51(1):13–25. doi: 10.1539/joh.K8004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Diener C. Most people are happy. Psychological Science. 1996;7(3):181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Sandvik E, Pavot W, Fujita F. Extraversion and subjective well-being in U.S. National probability sample. Journal of Research in Personality. 1992;26(3):205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(92)90039-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook G. The progress paradox: How life gets better while people feel worse. 1. New York: Random House; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D, Abdullah J. A study on the impact of the expectation of a holiday on an individual’s sense of well-being. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 2002;8(4):352–361. doi: 10.1177/135676670200800406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D, Abdullah J. Holidaytaking and the sense of well-being. Annals of Tourism Research. 2004;31(1):103–121. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth J. Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Annals of Tourism Research. 1997;24(2):283–304. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80002-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E. A functional approach to leisure analysis. Social Problems. 1961;9(1):2–8. doi: 10.1525/sp.1961.9.1.03a00010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gump BB, Matthews KA. Are vacations good for your health? The 9-year mortality experience after the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(5):608–612. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson JP, Weinryb RM, Göransson S, Pedersen NL, Åsberg M. Stability and predictive ability of personality traits across 9 years. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22(6):783–792. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00268-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Goldberg LR. A first large cohort study of personality trait stability over the 40 years between elementary school and midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(4):763–779. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson M, III, Beck CM. Genetic, neurological, and social bases of empathy. Human Communication. 2008;11(3):359–382. [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes LL, Lounsbury JW. An investigation of life satisfaction following a vacation: a domain-specific approach. Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17(3):129–140. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198904)17:2<129::AID-JCOP2290170205>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp S, Burt CDB, Furneaux L. A test of the peak-end rule with extended autobiographical events. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36(1):132–138. doi: 10.3758/MC.36.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kop WJ, Vingerhoets A, Kruithof G-J, Gottdiener JS. Risk factors for myocardial infarction during vacation travel. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(3):396–401. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000046077.21273.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostecki M. Waiting lines as a marketing issue. European Management Journal. 1996;14(3):295–303. doi: 10.1016/0263-2373(96)00009-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S. De-exoticizing tourist travel: Everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies. 2008;27(1):21–34. doi: 10.1080/02614360701198030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S, Brun W, Ogaard T. What tourists worry about—construction of a scale measuring tourist worries. Tourism Management. 2009;30(2):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lash S, Urry J. Economies of signs and space. London: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury JW, Hoopes LL. A vacation from work: Changes in work and nonwork outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986;71(3):392–401. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell D. The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. New York: Schocken Books; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. The tourist experience and everyday life. In: Dann GMS, editor. The tourist as a metaphor of the social world. Wallingford: CABI; 2002. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality. 1992;60(2):175–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Rathouse K, Scarles C, Holmes K, Tribe J. Public understanding of sustainable leisure and tourism: A report to the department for environment, food and rural affairs. London: Delfra, University of Surrey; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Milman A. The impact of tourism and travel experience on senior travelers’ psychological well-being. Journal Of Travel Research. 1998;37(2):166–170. doi: 10.1177/004728759803700208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TR, Thompson L, Peterson E, Cronk R. Temporal adjustments in the evaluation of events: the “Rosy view”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1997;33(4):421–448. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1997.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M, Xu F. Student travel experiences: memories and dreams. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. 2009;18(2):216–236. doi: 10.1080/19368620802591967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers DG. The American paradox: Spiritual hunger in an age of plenty. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Neal JD. The effects of different aspects of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life: Model validation, refinement, and extension. Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute And State University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Neal JD, Sirgy MJ. Measuring the effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life: further validation. Social Indicators Research. 2004;69(3):243–277. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-5012-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman M. Travel life cycle. Annals of Tourism Research. 1995;22(3):535–552. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00004-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello GL. Motivation and anticipation in post-industrial tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 1993;20(2):233–249. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(93)90052-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E, Fujita F. Extraversion and happiness. Personality and Individual Differences. 1990;11(12):1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(90)90157-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce PL. “Environment shock”: a study of tourists’ reactions to two tropical islands. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1981;11(3):268–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1981.tb00744.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RC. Tourist motivation and typologies. In: Lew AA, Hall CM, Williams AM, editors. Companion to tourism. Oxford: Pergamon; 2004. pp. 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Recreational tourism: A social science approach. London: Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. The travel career ladder: an appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25(4):936–957. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00044-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schor J. The overworked American. New York: Basic Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schor J. The overspent American. New York: Harper Collins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Puckó L, editors. Health and wellness tourism. Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes AF, Kite K. Flight stress: Stress, fatigue, and performance in aviation. Aldershot: Avebury Aviation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss-Blasche G, Ekmekcioglu C, Marktl W. Does vacation enable recuperation? Changes in well-being associated with time away from work. Occupational Medicine. 2000;50(3):167–172. doi: 10.1093/occmed/50.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terraciano A, Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality plasticity after age 30. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32(8):999–1009. doi: 10.1177/0146167206288599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. (2002). Definition of tourism. Retrieved 01 September 2008, from http://www.world-tourism.org/statistics/tsa_project/TSA_in_depth/chapters/ch3-1.htm

- Tourism market trends 2006. World overview and tourism topics (No. 2006 ed) Madrid: UNWTO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely N. The tourist experience: conceptual developments. Annals of Tourism Research. 2005;32(1):199–216. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck GL, Vingerhoets AJJM. Leisure sickness: a biopsychosocial perspective. Psychological Topics. 2007;16(2):187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tilburg MA, Vingerhoets AJ, Heck GL, Kirschbaum C. Mood changes in homesick persons during a holiday trip. A multiple case study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1996;65(2):91–96. doi: 10.1159/000289053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. How do we assess how happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. USA: University of Notre Dame; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. The international scale interval study: Improving the comparability of responses to survey questions about happiness. In: Moller V, Huschka D, editors. Quality of life in the new millennium: Advances in quality-of-life studies, theory and research, vol. 35. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R, Hagerty MR. Rising happiness in nations 1946–2004: a reply to Easterlin. Social Indicators Research. 2006;79(3):421–436. doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-5074-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vingerhoets AJJM, Sanders N, Kuper W. Health issues in international tourism: the role of health behavior, stress and adaptation. In: Tilburg MV, Vingerhoets AJJM, editors. Psychological aspects of geographical moves: Homesickness and acculturation stress. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Academic Archive; 1997. pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westman M, Eden D. Effects of a respite from work on burnout: vacation relief and fade-out. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82(4):516–527. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westman M, Etzion D. The impact of vacation and job stress on burnout and absenteeism. Psychology and Health. 2001;16(5):595–606. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]