Abstract

A sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas cv. ‘Jinhongmi’) MADS-box protein cDNA (SRD1) has been isolated from an early stage storage root cDNA library. The role of the SRD1 gene in the formation of the storage root in sweetpotato was investigated by an expression pattern analysis and characterization of SRD1-overexpressing (ox) transgenic sweetpotato plants. Transcripts of SRD1 were detected only in root tissues, with the fibrous root having low levels of the transcript and the young storage root showing relatively higher transcript levels. SRD1 mRNA was mainly found in the actively dividing cells, including the vascular and cambium cells of the young storage root. The transcript level of SRD1 in the fibrous roots increased in response to 1000 μM indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) applied exogenously. During the early stage of storage root development, the endogenous IAA content and SRD1 transcript level increased concomitantly, suggesting an involvement of SRD1 during the early stage of the auxin-dependent development of the storage root. SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro produced thicker and shorter fibrous roots than wild-type plants. The metaxylem and cambium cells of the fibrous roots of SRD1-ox plants showed markedly enhanced proliferation, resulting in the fibrous roots of these plants showing an earlier thickening growth than those of wild-type plants. Taken together, these results demonstrate that SRD1 plays a role in the formation of storage roots by activating the proliferation of cambium and metaxylem cells to induce the initial thickening growth of storage roots in an auxin-dependent manner.

Keywords: Auxin, development, MADS-box gene, storage root, sweetpotato, thickening growth

Introduction

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) is the world's seventh most important food crop, and its storage roots provide high levels of digestible nutrients and high plant biomass per hectare. In the early stage of root development, sweetpotato initially forms colourless fibrous roots. As root development proceeds, some of these fibrous roots become pigmented and begin to swell, ultimately developing into storage roots. Based on early anatomical studies on storage root morphogenesis (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1991), the storage root has been defined as the root in which there is anomalous secondary cambial activity inside of a primary cambium. Both the linear growth and the promotion of the thickening growth of the storage root and/or the yield of storage roots have been shown to be affected by environmental factors, including soil temperature, humidity, light, photoperiod, carbon dioxide, and drought (Loretan et al., 1994; Hill et al., 1996; Mortley et al., 1996; Eguchi et al., 1998; Pardales et al., 1999; Kano and Ming, 2000; van Heerden and Laurie, 2008).

Growth hormones play a role in the formation and thickening growth of storage roots. Cytokinin and auxin [indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)] levels have been found to be high during the early stage of storage root formation in sweetpotato (Akita et al., 1962; Matsuo, 1983; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1992), suggesting that these hormones are involved in the onset and subsequent primary thickening growth of storage roots. The role of cytokinin in storage root formation is supported by the recent finding that the exogenous application of cytokinin induces storage root formation in the presence of high sucrose concentrations (Eguchi and Yoshida, 2008). Storage root yield is largely dependent on secondary thickening growth that occurs in the later stage of storage root development. It is positively correlated with concentrations of abscisic acid (ABA) and cytokinin, but not with IAA levels (Wang et al., 2006) which actually decrease gradually with secondary thickening growth (Akita et al., 1962; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1992). This leads to the hypothesis that cytokinin, auxin, and ABA possibly have different roles in the induction and/or thickening growth of storage roots, with auxin being involved in the initial formation of the storage root, ABA in the later secondary thickening growth, and cytokinin active during both the early and later stages. To date, however, the distinct role of each hormone has not been directly elucidated.

MADS-box genes encode transcription factors that play fundamental roles in diverse and important biological functions in animal, fungal, and plant development (Messenguy and Dubois, 2003; Kaufman et al., 2005). MADS-box proteins contain a highly conserved MADS-domain that is required for their DNA binding and dimerization properties (Messenguy and Dubois, 2003). Most of the plant MADS-box proteins are of the MIKC type, and also contain a second conserved region (K box) and two variable regions (I region and C-terminus) (Kaufman et al., 2005). These last three regions have been found to be expressed in floral organs and play roles in floral organ differentiation through either homo- or hetero-dimerization (Theissen et al., 2000; Theißen, 2001; Kaufman et al., 2005). MADS-box genes have also been reported to be expressed in pollen, ovule, endosperm, and other vegetative tissues in Arabidopsis thaliana and potato (Solanum tuberosum) (Carmona et al., 1998; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000). Several MADS-box genes (IbMADS3, IbMADS4, IbMADS10, IbMADS79, IbAGL17, and IbAGL20) expressed in root tissues have been isolated from sweetpotato, and their possible roles in root development have subsequently been deduced on the basis of their expression pattern (Kim et al., 2002, 2005; Lalusin et al., 2006).

Improvements in various molecular approaches have enabled the mining of genes involved in storage root development in sweetpotato, resulting in the identification of a number of genes that are differentially expressed in developing storage roots (You et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2005). Based on the results of their comparison of the distribution of KNOX1 gene expression and endogenous trans-zeatin riboside (t-ZR) in sweetpotato roots, Tanaka et al. (2008) suggested three sweetpotato class 1 knotted1-like homeobox (KNOX1) genes as possible regulators of cytokinin levels in storage roots. Ku et al. (2008) recently isolated IbMADS1 from sweetpotato and analysed its functional role in storage root development using potato overexpressing IbMADS1. However, to date, due to the difficulty in generating transgenic sweetpotato plants, researchers have been unable to verify directly whether a sweetpotato gene is actually involved, or not, in the formation or thickening growth of storage roots using sweetpotato gain- and/or loss-of function mutants.

In the present study a MADS-box protein gene (SRD1) from sweetpotato (I. batatas cv. ‘Jinhongmi’) was identified. The results indicate that the expression of SRD1 is root specific and that its transcript level increases with increasing IAA content during the early stage of storage root development. An earlier thickening growth was observed in the fibrous roots of SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants; this growth is suggested to be due to an enhanced proliferation of cambium and metaxylem cells. The results provide evidence that the functional role of SRD1 is related to the proliferation activity in metaxylem and cambium cells that results in an induction of the auxin-dependent initial thickening growth of storage roots.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Sweetpotato [I. batatas (L.) Lam. cv. ‘Jinhongmi’] plants were propagated by cutting and planting apical stems bearing three leaves in the greenhouse at 25–30 °C under a long-day photoperiod (16/8 h, light/dark).

RNA gel blot analysis

Total RNA was extracted from various tissues at three different developmental stages [fibrous root (diameter <0.2 cm), young storage root (diameter 0.5–1.0 cm), and mature storage root (diameter >5.0 cm)] using a modified guanidinium–SDS lysis buffer method and the CsCl gradient method as described in You et al. (2003). Total RNA (25 μg) was denatured, electrophoresed, and then transferred onto nylon membranes (Tropilon-Plus; Tropix) using the downward alkaline capillary method. A biotin-labelled probe was prepared by PCR amplification of the full-length SRD1 cDNA with T3 and T7 primers. The PCR cycling conditions consisted of pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 58 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C using dNTP mixed with biotin-labelled dCTP (Invitrogen). The labelled probe was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization, washing, and detection were performed as described previously (You et al., 2003).

Subcellular localization

The coding sequence of SRD1 (651 bp) was amplified using primers SRD1-103 (5′-CATCCCGGGATGGGGAGGGGCAAG-3′) and SRD1-920R (5′- GTGAGCTCCACTGCCATAAGACCACAAGG-3′). The resulting PCR product was fused in-frame to the coding region of smGFP to generate the SRD1::smGFP fusion construct under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. A transient transformation was performed as described by Chiu et al. (1996). Onion epidermal cell segments were peeled and placed on an MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) plate [half-strength MS salts (Duchefa), 0.3% phytagel (Sigma)]. SRD1::smGFP plasmid DNA (1 μg) was introduced into onion epidermal segments using a biolistic gun device (PDS-1000/He; Bio-Rad) with the following parameters: the stopping screen was positioned 3 cm below the rupture disk; the target tissue was positioned 6 cm below the stopping screen; helium pressure was 1100 psi. After bombardment, the tissues were incubated for 24 h at room temperature (25 °C, darkness). Green fluorescence was observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

In situ hybridization

Storage roots (0.5 cm in diameter) were cut transversely and fixed with FAA comprising 50% ethanol, 5% acetic acid, and 3.7% formaldehyde at 4 °C for 10 d. The samples were then dehydrated stepwise for 30 min in increasing concentrations of ethanol (50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100%), embedded in paraffin (Sigma) for 5 d, and cut into 10 μm thick slices on coated slides. The sections were treated with xylene followed by hydration, proteinase K treatment, acetylation, and dehydration. The full-length SRD1 sequence was used as a probe. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled sense and antisense SRD1 probes were synthesized with T3 and T7 RNA polymerases using a DIG RNA labelling kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization and detection were performed following the protocol described by Shin et al. (2006). Accumulation of SRD1 mRNA was analysed under bright field microscopy (BX51; Olympus) equipped with a CCD camera (DP70; Olympus).

Hormone treatment

Sweetpotato plantlets bearing a single leaf and petiole (single-leaf plantlets) were collected from sweetpotato plants and incubated in flasks containing distilled water for 3 weeks. After fibrous roots had developed from the distal end of the petiole, the single-leaf plantlets were incubated in various concentrations of IAA at 25 °C in the dark for various time periods (0–24 h). After the hormone treatment, total RNA was extracted from the fibrous roots using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and used for real-time and semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA (5 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis supermix (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA solution was then diluted with 30 μl of TE (10 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). The primers for real-time RT-PCR were as follows: SRD1 (5′-AGAGGAGAAATGGGTTGTTTA-3′; 5′- GTGCACGAAACTCCCCTT-3′), BU690901 (5′-GAAGAAGATTGTGAATCCAAATCTG-3′; 5′-GGCATATTCTGATCCTTTGTAGC-3′), BU691583 (5′-GACTGGATGCTCGTTGGTGA-3′; 5′-CAGTTTACTAGGTCGACATGGAATA-3′), and BU691819 (5′-GGACGTAAATCTCTGTTTGTTCG-3′; 5′-GCTATAAACTTTGGTTCACATTCAA-3′). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the LightCycler® 480 quantification system (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Expression levels were normalized with β-tubulin expression amplified with 5′-CAACTACCAGCCACCAACTGT-3′ and 5′-CAGATCCTCACGAGCTTCAC-3′ primers. The real- time PCR mixture was prepared in a LightCycler® 480 Multiwell Plate 384 containing 10 μM of each primer, 1× LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Diagnostics), and 5 μl of DNA template, in a final reaction volume of 20 μl. The LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master mix contained Taq DNA polymerase, reaction buffer, dNTP mix (including dUTP in place of dTTP), and 3.2 mM MgCl2. The real-time PCR was performed using the following cycle parameters: an initial polymerase activation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Following the amplification phase, a melting curve analysis was conducted from 65 °C to 97 °C, with a cooling step at 40 °C for 10 s (ramp rate of 2.0 °C s−1). The fluorescence signal was acquired using the Mono Hydrolysis Probe setting (483–533 nm) following the 72 °C extension phase of each cycle. The second derivative maximum method in the LightCycler® 480 quantification software (Roche Diagnostics) was used to evaluate the data. The data were then exported to Microsoft Excel and the reproducibility parameters calculated. Total RNA from storage roots (diameter 1.0–5.0 cm) was extracted using the method described in You et al. (2003).

RT-PCR

Primers for RT-PCR were identical to those used for real-time RT-PCR. Sweetpotato β-tubulin DNA was amplified as an internal equal loading control. A 1μl aliquot of the cDNA reaction mixture and 10 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer were used in a total volume of 20 μl. PCR amplification was performed with an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C, terminating with a 5 min final extension at 72 °C. The numbers of cycles used for each amplification were: β-tubulin, 24 cycles; BU690901, 27 cycles; BU691583, 27 cycles; BU691819, 33 cycles. The amplified products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel.

IAA measurements

The concentration of IAA was determined as described by Boonplod (2005) with some modifications. Briefly, the lyophilized sample of fresh storage roots (10 g) was homogenized in 80% cold methanol (50 ml) and then kept in darkness at 4 °C overnight. The methanol extracts were concentrated completely by vacuum evaporation, dissolved in 4 ml of 0.01 M ammonium acetate (pH 9.0), and then centrifuged at 20000 rpm for 25 min. The supernatant was loaded on a column filled with 10 ml of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP; Sigma) and 4 ml of DEAE-Sephadex A-25 (Sigma). Anionic compounds containing free IAA bound to the column were eluted by 0.1 M acetic acid and further purified by loading on the C18Sep-PaK cartridge (Sigma). The IAA was eluted from the cartridge with 4 ml of 40% methanol in 0.1 M acetic acid. After evaporation of the methanol, samples in duplicate were subjected to quantitative analysis for auxin using the Phytodetek™-IAA immunoassay detection kit (Agdia Inc., ID, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were gathered from dilutions giving values within the linear detection range.

Generation of SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants

The full-size SRD1 cDNA amplified with T3 and T7 primers was cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of the pMBP1 binary vector. The resulting construct was introduced into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and transformed by an A. tumefaciens-mediated method. Embryogenic calli were induced from I. batatas (L.) Lam. cv. ‘Yulmi’ shoot apical meristems cultured on MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 1 mg l−1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 3% sucrose, and 0.4% gelrite (MS1D), kept at 25 °C in the dark, and proliferated by subculture at 4 week intervals on the same fresh medium. After co-culture of embryogenic calli with A. tumefaciens, embryogenic calli were kept on MS1D medium containing 100 mg l−1 kanamycin and 400 mg l−1 claforan (selection medium) at 25 °C in the dark and subcultured under the same conditions every 3 weeks for 4–5 months. Somatic embryos were induced by transferring kanamycin-resistant calli to hormone-free MS medium containing 100 mg l−1 kanamycin. Regenerated plants were cultured on the same medium and maintained at 25 °C under a 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod with light supplied at a light intensity of 70 mmol m−2 s−1 by fluorescent tubes. The plantlets were transplanted into pots and grown in the greenhouse.

Microscopic observation

Apical meristems of sweetpotato plants bearing 2–3 leaves were grown on MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) at 25 °C for 14 d under long-day conditions (16/8 h of light/dark). The thickest primary fibrous root was collected, and transverse sections were prepared at 1.0 cm from the root tip. Samples were fixed with 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 4 °C for 10 d. After fixation, the tissues were washed twice with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (42.3 mM NaH2PO4 and 57.7 mM Na2HPO4) for 5 min, dehydrated stepwise for 30 min in a graded series of ethanol (50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100%), embedded in acrylic resin (LR White; London Resin Company) for 5 d, and cut into 1.0 μm thick sections on an ultramicrotome (BROMMA 2088; LKB). For observation of thick roots and storage roots, the transverse sections were prepared by the method described in ‘In situ hybridization’. The sections were stained with 1% safranin O and observed under light microscopy (BX51; Olympus).

SRD1 sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank data libraries under the accession no. FJ237529 with the name of a sweetpotato MADS-box cDNA.

Results

Sequence analysis of SRD1

In an earlier study, the cDNA of a MADS-box protein was identified among 2859 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) isolated from an early-stage storage root cDNA library (You et al., 2003). Sequencing analysis revealed that the cDNA clone is 1059 bp long and encodes a 217 amino acid protein. This clone was subsequently designated SRD1 (Storage Root Development-related 1) gene. The nucleotide sequence of SRD1 was found to have 99% identity with the previously reported IbMADS1 cDNA in the overlapping region (Ku et al., 2008) (Supplementary Fig. S1 available at JXB online). Compared with IbMADS1 cDNA, the SRD1 cDNA is 33 bp shorter in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and 30 bp longer in the 3′ UTR, and contains a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (thymine to guanine) at nucleotide 180 and a 3 bp deletion between nucleotides 558 and 559 in the open reading frame (ORF) region. This alteration in nucleotide sequence results in a single residue change (phenylalanine to leucine) at amino acid 29 in the MADS-box domain and a single residue deletion (glutamine in IbMADS1) between amino acids 155 and 156 of SRD1 in the K-box domain. The amino acid residue at position 29 in other related MADS-box proteins is either phenylalanine or leucine (Ku et al., 2008), suggesting that the amino acid substitution at position 29 may not result in a functional alteration in SRD1. A single residue deletion between amino acids 155 and 156 of SRD1 resides in the K-box domain region, which has a variable amino acid sequence, indicating that the functional significance of the deletion is presently unknown.

To determine whether SRD1 is an allelic variant of IbMADS1 or a distinct gene from IbMADS1, the presence of the IbMADS1 gene in the genome of I. batatas cv. ‘Jinhongmi’ was investigated. Eleven MADS-box protein sequences were identified among the 2859 ESTs isolated from the early-stage storage root cDNA library mentioned above (You et al., 2003). Sequence comparison of these 11 MADS-box gene cDNAs revealed that nine and two cDNAs showed perfect sequence identity with the SRD1 sequence and IbMADS1 sequence, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). These results suggest that both the SRD1 and IbMADS1 genes are present in the genome of I. batatas cv. ‘Jinhongmi’ and that both are expressed in the storage root. They also indicate that SRD1 is a major MADS-box protein gene in the early-stage storage root.

Expression of SRD1 is root specific and increased in the storage root

The expression pattern of SRD1 was investigated in detail at the RNA level by a gel blot hybridization analysis of RNAs extracted from various tissues, including the leaf, petiole, stem, fibrous root, and storage root tissues, at three different developmental stages (fibrous root, young storage root, and mature storage root) (Fig. 1A). Total RNA extraction from the mature storage root failed due to the presence of high levels of polysaccharides. Based on the finding that SRD1 is the major MADS-box protein gene in the early-stage storage root, a full-length SRD1 cDNA was used as a probe. The SRD1 transcript was detected only in the fibrous roots and young storage roots, but not in stem, leaf, and petiole tissues at any developmental stage (Fig. 1B). The transcript level of SRD1 was low in fibrous roots from both the fibrous root and mature storage root stages, but it increased in young storage roots, indicating that the expression of SRD1 is root specific and increases during the early storage root developmental stage.

Fig. 1.

Expression pattern of SRD1. (A) Developmental stages of sweetpotato. (B) RNA gel blot analysis of SRD1. Full-length SRD1 cDNA was used as a probe. The ethidium bromide-stained rRNA is shown as a loading control (lower panel). FR, fibrous root (diameter <0.2 cm); YSR, young storage root (diameter 0.5–1.0 cm); MSR, mature storage root (diameter >5 cm); FR-MSR, fibrous root from mature storage root stage. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

The full-length SRD1 cDNA fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) was introduced into onion epidermal cells in an attempt to determine the subcellular localization of SRD1. Onion cells transformed with the plasmid expressing only GFP showed a green fluorescence throughout the cell. In contrast, fluorescence was detected predominantly in the nucleus in cells transformed with the plasmid expressing the SRD1::GFP fusion protein (Fig. 2), indicating that SRD1 is a nuclear-localized protein. This result suggests that SRD1, like many of the other MADS-box genes identified to date, is most probably a transcription factor.

Fig. 2.

Subcellular localization of SRD1 in onion epidermal cells. (A) The control GFP. (B–E) SRD1::GFP fusion protein. (A, B, D) Fluorescent images. (C, E) Visible light images. (D) Onion cells were stained with the DNA binding dye DAPI. (E) Merged image of GFP with DAPI signal. GFP, green fluorescent protein, DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Transcripts of SRD1 localize in the vascular and cambium cells in the storage root

In situ hybridization was used to determine the localization of SRD1 mRNA accumulation in developing storage roots (Fig. 3). Storage roots of sweetpotato are defined as the root which retains anomalous secondary cambial activity inside of the primary cambium. As the secondary meristem is known to be activated in 5 mm wide roots (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1991), transverse sections of 5 mm wide storage roots were hydridized with the DIG-labelled antisense SRD1 probe. The presence of a violet stain, indicating a positive hybridization signal, i.e. the SRD1 transcript, was mainly observed in the actively dividing cells, including the vascular and cambium cells of the storage root. Accumulation of the SRD1 transcript was detected in the primary cambium, secondary cambium, and primary phloem cells (Fig. 3G, H, I). No hybridization signal was detected in the storage parenchyma cells and xylem vessels.

Fig. 3.

Localization of SRD1 transcripts in young storage root of sweetpotato. Young storage root (diameter 5 mm) and digoxigenin-labelled sense and antisense SRD1 probes were used in in situ hybridization. (A–C) Cross-section of a young storage root. (D–F) Cross-section hybridized with the sense riboprobe. (G– I) Cross-section hybridized with the antisense riboprobe. PC, primary cambium; SC, secondary cambium; PH, primary phloem. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Transcript level of SRD1 increased in response to exogenous IAA

To determine the transcriptional regulation of SRD1, SRD1-specific primers were designed to contain nucleotide 180 (the nucleotide showing an SNP between SRD1 and IbMADS1) and the 3 bp deletion region in SRD1 at the 3′ end of the forward primer and at the 3′ end of the reverse primer, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). PCR amplification using SRD1 or IbMADS1 cDNA as templates was performed at various annealing temperatures (53–63 °C) to verify the specificity of the SRD1-specific primers. At annealing temperatures >58 °C, the SRD1-specific primers selectively amplified the SRD1 sequence but did not amplify the IbMADS1 sequence (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Auxin may have a number of functions in the formation and thickening growth of storage roots (Akita et al., 1962; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1992; Wang et al., 2006). The possible transcriptional regulation of SRD1 by exogenous auxin was investigated by incubating sweetpotato plantlets bearing a single leaf and petiole (single-leaf plantlets) for 3 h in a solution containing various concentrations of IAA. Total RNAs were then extracted from the IAA-treated fibrous roots and subjected to analysis by real-time RT-PCR at an annealing temperature of 58 °C using SRD1-specific primers. The SRD1 mRNA levels were regulated in response to exogenously applied IAA. The transcript level of SRD1 decreased at 50 μM and 500 μM IAA, but increased sharply at 1000 μM IAA (Fig. 4A). At 2000 μM IAA, however, it had decreased to almost the same level at that observed at 0 μM IAA. A time course study of SRD1 expression (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h) in fibrous roots cultured in 500 μM IAA revealed that the transcript level of SRD1 increased sharply at 6 h after treatment but that this elevated level was not maintained at 12 h after treatment (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results suggest that the transcript level of SRD1 is finely regulated in response to IAA concentration, with increases in the SRD1 transcript level occurring only at specific concentrations of IAA and at specific times after IAA treatment.

Fig. 4.

Effect of auxin on the expression of SRD1. Total RNA was extracted from the fibrous roots treated with various concentrations of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Real-time RT-PCR data were normalized to those for the endogenous β-tubulin gene. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three technical replicates measured on fibrous roots collected from at least three different sweetpotato plantlets and subsequently pooled for analysis. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses were conducted with each designated gene-specific primer. The sweetpotato β-tubulin gene was used as an equal loading internal control. (A) Transcript levels of SRD1 in response to treatment with various concentrations of exogenous IAA for 3 h. (B) Time course of the expression of SRD1 and three sweetpotato AUX/IAA genes (BU690901, BU691583, and BU691819) in response to IAA (500 μM) for various time periods (0–24 h).

To date, IAA-regulated genes have not been identified in sweetpotato. Three sweetpotato EST clones (NCBI accession nos BU690901, BU691583, and BU691819) showing nucleotide sequence identity with auxin-inducible AUX/IAA genes were identified among sweetpotato EST clones isolated from early-stage storage roots (You et al., 2003). BU690901 was found to have 66% identity with the tobacco auxin-responsive gene Nt-iaa2.3 in the overlapping region at the amino acid level (Dargeviciute et al., 1998). Deduced amino acid sequences of BU691819 and BU691583 share 85% and 49% identities, respectively, with the auxin-inducible GH1 sequence (Clouse et al., 1992). Because the transcript level of SRD1 increased when only a high concentration of IAA was applied exgenously (range: 500–1000 μM; Fig. 4), the effect of IAA treatment needed to be verified. To this end, these three sweetpotato genes were tested as possible IAA marker genes by investigating their transcript levels in IAA-treated fibrous roots. The transcript levels of the three genes increased in response to IAA (500 μM) with different time courses (Fig. 4B), thereby verifying the three genes as auxin-inducible AUX/IAA genes and also demonstrating that the IAA treatment was effective.

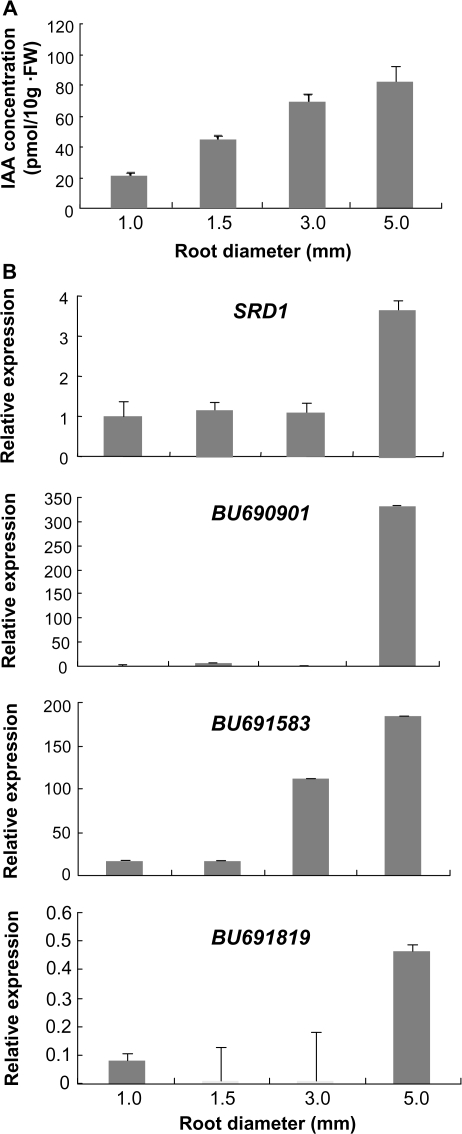

Transcript level of SRD1 elevated in response to increasing IAA content during early-stage storage root development

Sweetpotato roots have been classified as three distinct types: fibrous root (diameter <2 mm), thick root (diameter 2–5 mm), and storage root (diameter >5 mm) (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973). To determine the levels of IAA in the developing storage roots, endogenous IAA concentrations were examined in sweetpotato roots of diameters 1, 1.5, 3, and 5 mm, representing unpigmented white fibrous roots, pigmented fibrous roots, thick roots, and storage roots, respectively. The endogenous IAA content increased gradually with increasing root diameter up to 5 mm (Fig. 5A). Ultimately, the IAA content in the storage roots (diameter 5 mm) was ∼4-fold higher than that in unpigmented fibrous roots (diameter 1 mm), indicating that there was a large increase in the endogenous IAA level during the early stage of storage root development.

Fig. 5.

Endogenous IAA concentration and SRD1 transcript levels during early-stage storage root development. (A) Endogenous IAA levels in the unpigmented (diameter 1.0 mm) and pigmented (diameter 1.5 mm) fibrous root, thick root (diameter 3.0 mm), and young storage root (diameter 5.0 mm). Each sample represents pools of roots with a designated maximum diameter from at least three different sweetpotato plants. (B) Transcript levels of SRD1 and three AUX/IAA genes (BU690901, BU691583, and BU691819) in the roots with designated maximum diameters. Real-time RT-PCR data were normalized to those for the endogenous β-tubulin gene. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three technical replicates measured on roots with a designated maximum diameter collected from at least three different sweetpotato plants and subsequently pooled for analysis.

The effect of this increased endogenous IAA content on the transcript levels of SRD1 and the three auxin-inducible AUX/IAA genes used as IAA marker genes in Fig. 4B was also determined (Fig. 5B). Real-time PCR analysis revealed that the transcript level of SRD1 was low in the 1, 1.5, and 3 mm wide roots but increased in 5 mm wide storage roots. The transcript levels of two AUX/IAA genes also showed an increase in the 5 mm wide storage roots although the transcript level of each AUX/IAA gene differed significantly. (Note that the range of the y-axis of the three graphs differs remarkably.) The transcript level of BU690901 dramatically increased in 5 mm wide storage roots, whereas that of BU691583 increased gradually from 1 mm to 5 mm wide roots. These results indicate that the increased level of endogenous IAA positively affects the transcript levels of SRD1 and the three auxin-inducible genes. Consequently, the transcript levels of SRD1 as well as those of the three auxin-inducible genes increased significantly in the early stage of storage root development.

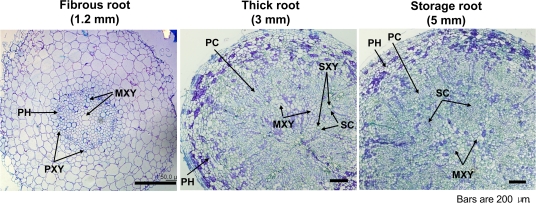

Fibrous roots of SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants exhibited an earlier thickening growth

Morphological features of the three distinct types of sweetpotato roots (fibrous root, thick root, and storage root) were examined on transverse sections of root obtained from cv. ‘Jinhongmi’ (Fig. 6). The fibrous root was hexarch, and the centripetally developed protoxylem elements were connected to 2–3 centrally located metaxylem cells. In thick root, the vascular cambium was differentiated, and circular primary cambium appeared around the central metaxylem cells. Anomalous secondary cambia were also laid down around the secondary xylem elements. Storage root showed a thickening growth that occurred by continuous activity of the vascular cambium (primary cambium) and anomalous secondary cambia. An additional prominent morphological characteristic of thick and storage roots is anomalous proliferation of metaxylem cells in the centre part of the stele. These morphological features of the three root types from cv. ‘Jinhongmi’ are identical to those described by Kokubu (1973) and Wilson and Lowe (1973).

Fig. 6.

Anatomical characteristics of three different types of sweetpotato roots. Cross-sections of fibrous, thick, and storage roots were prepared from sweetpotato [I. batatas (L.) Lam. cv. ‘Jinhongmi’] roots. The number in parentheses indicates the maximum diameter of each root. PH, phloem; MXY, metaxylem; PXY, protoxylem; PC, primary cambium; SC, secondary cambium; SXY, secondary xylem element. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Sweetpotatoes cultured in vitro do not normally produce thick roots or storage roots on hormone-free MS medium, rather they produce only fibrous roots. Thus, to analyse the function of SRD1 in the formation of the storage root in an in vitro culture system, SRD1-overexpressing (ox) sweetpotato plants were generated under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Five independent SRD1-ox transgenic lines were obtained. Functional transformants were identified by PCR analysis of genomic DNA from the transgenic plants (Supplementary Fig. S4 at JXB online) and by detection of the increased levels of the SRD1 mRNA (Fig. 7A). SRD1 transcript accumulation in the fibrous roots of the SRD1-ox transgenic lines was moderately elevated in line 1 and strongly elevated in lines 2, 3, 4, and 5. Lines 1 and 3 were selected for further phenotypic analysis.

Fig. 7.

Characterization of SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants. (A) SRD1 transcript levels in SRD1-ox plants. Total RNA was isolated from fibrous root tissue of the sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted with SRD1-specific primers. Numbers 1–5 represent SRD1-ox sweetpotato lines 1–5. Sweetpotato β-tubulin was used as an equal loading internal control. WT, wild-type. (B) Morphology of the fibrous roots in SRD1-ox plants. Pictures were taken from the bottom of the culture plate for a better view of the root morphology. (C) Microscopic observation of the transverse section of fibrous root in the area marked with a box in B. The lower panel is an enlarged image of the upper panel. MPH, metaphloem; MX, metaxylem; PC, primary cambium; SC, secondary cambium; PXY, protoxylem. (D) Quantitative characterization of fibrous root development in SRD1-ox lines 1 and 3. Data were collected from the sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro at 14 d after planting and are the means±SD from three separate measurements of three individual plants. Root diameter and cell numbers were measured on transverse sections of fibrous roots. Root diameter was determined by measuring the largest diameter on the circle enclosed by epidermal cells. Numbers of metaxylem cells include numbers of mature and immature metaxylem cells. For determination of cell numbers and root diameters, three cell files from three individual plants were used. WT, wild-type. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Cuttings of SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants bearing the apical meristem and 2–3 leaves were planted on hormone-free MS medium; root morphogenesis occurred at 2 weeks after planting (Fig. 7B, D). No phenotype was observed in the aerial parts of SRD1-ox plants. Wild-type plants produced fibrous roots with short lateral roots, whereas SRD1-ox 1 and 3 plants produced only primary fibrous roots, with no lateral roots. Elongation growth of the primary roots was significantly inhibited in SRD1-ox 1 and 3 plants, with the primary roots of these mutants being markedly shorter than those of the wild type. Wild-type plants had significantly more primary roots than SRD1-ox 1 and 3 plants, but the latter produced thicker fibrous roots. The extent of the decrease in root length and the increase in root diameter was more severe in SRD1-ox 3 than in 1, suggesting that the observed root phenotype in these mutants was attributable to the increased levels of SRD1 mRNA accumulation.

Proliferation of metaxylem and cambium cells was markedly enhanced in SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants

Transverse sections of the maturation zone (taken at 1.0 cm intervals beginning from the root tip) were prepared from the thickest fibrous root of the wild-type and SRD1-ox plants in order to study the phenotype at the cellular level in more detail. The fibrous roots were 640±35, 1064±55, and 1400±37 μm in diameter in the wild-type and SRD1-ox 1 and 3 plants, respectively (Fig. 7C, D; Table 1). Thus, the diameters of the fibrous roots from SRD1-ox lines 1 and 3 had increased by 1.66±0.02-fold and 2.12±0.06-fold, respectively, with the cortex expanding by 1.64±0.01-fold and 2.10±0.03-fold, and the stele by 1.68±0.07-fold and 2.30±0.05-fold, respectively, in these mutants. This result indicates that the expansion ratio of the stele is higher than that of the cortex.

Table 1.

Effect of SRD1 overexpression on the thickening growth of fibrous root

| Root area | WTa | 1 | 3 | ||

| Db (μm) | Db (μm) | Ratec | Db (μm) | Ratec | |

| Cortex+steled | 640±35 | 1064±55 | 1.66±0.02 | 1400±37 | 2.12±0.06 |

| Cortexe | 480±27 | 784±48 | 1.64±0.01 | 1024±42 | 2.10±0.03 |

| Stelef | 160±13 | 280±11 | 1.68±0.07 | 376±22 | 2.30±0.05 |

Data are means ± SD from three separate measurements with three individual plants and are collected from the sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro at 14 d after planting.

Wild type.

Diameter measured with transverse sections of fibrous roots.

Expansion rate relative to the wild type.

Determined by measuring the largest diameter on the circle enclosed by epidermal cells.

Calculated by subtracting the diameter of the stele from the diameter of the cortex and stele.

Determined by measuring the largest diameter on the circle enclosed by endodermis cells.

The fibrous roots from wild-type plants showed the typical anatomy of young sweetpotato roots in that the root stele was relatively small and the metaxylem and metaphloem were recently differentiated (Fig. 7C). The formation of the hexarch stele had not yet been completed, and the cortex contained many schizogenous intercellular spaces. Cell proliferation was significantly enhanced in the SRD1-ox 1 and 3 plants, resulting in an increased number of cells in the cortex and stele compared with the wild type (Fig. 7C, D; Table 2). This increased level of cell proliferation was much higher in the stele (3.08±0.05- to 3.84±0.01-fold) than that in cortex (2.17±0.00- to 2.46±0.12-fold), and this increase was particularly evident in terms of the numbers of metaxylem cells. There were 26±3 metaxylem cells (mature and immature metaxylem cells) in the wild-type plants and 108±13 (4.15±0.32-fold) and 127±5 (4.88±0.33-fold) metaxylem cells in SRD1-ox lines 1 and 3, respectively. Another prominent alteration in the root structure was the increase in the number of primary cambium cells in the stele of SRD1-ox plants: in the wild-type plants, the primary cambium cells located between the phloem and xylem cells had only recently begun to divide, while in SRD1-ox plants, cell division of the primary cambium cells was significantly enhanced (Fig. 7C, D; Table 2). This resulted in the mutant plants having many more primary cambium cells (line 1, 100±7; line 3, 161±35) than the wild type (44±6). In particular, in mutant 3 plants, the circular secondary cambium (a morphological marker for phase transition from the fibrous root to the storage root) as well as the primary cambium had differentiated around discrete protoxylem. These results indicate that the proliferation of metaxylem and cambium cells was markedly elevated in SRD1-ox plants and that this elevated cell proliferation activity certainly contributed to the early thickening growth in the fibrous root. Based on the increase in metaxylem and primary cambium cell number, the proliferation activity was higher in SRD1-ox 3 plants than in SRD1-ox 1 plants, indicating that the proliferation activity was positively correlated with the level of SRD1 mRNA and that the increased proliferation activity was attributed to the elevated levels of SRD1 transcripts.

Table 2.

Effect of SRD1 overexpression on the proliferation activities of cells in fibrous root

| Cell type | WTa | 1 | 3 | ||

| No. of cellsb | No. of cellsb | Ratec | No. of cellsb | Ratec | |

| Cortex | 232±18 | 503±39 | 2.17±0.00 | 570±15 | 2.46±0.12 |

| Steled | 140±3 | 432±2 | 3.08±0.05 | 538±11 | 3.84±0.01 |

| Metaxyleme | 26±3 | 108±13 | 4.15±0.32 | 127±5 | 4.88±0.33 |

| Cambium | 44±6 | 100±7 | 2.27±0.13 | 161±35 | 3.66±0.26 |

Data are means ± SD from three separate measurements of three cell files from three individual plants and are collected from the sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro at 14 d after planting.

Wild type.

Counted on transverse sections of fibrous roots.

Proliferation rate relative to the wild type.

Numbers of entire cells inside endodermis cells.

Numbers of metaxylem cells including mature and immature metaxylem cells.

Discussion

The expression pattern of SRD1 has been characterized and the effect of overexpressing SRD1 cDNA was investigated with the aim of elucidating the role of SRD1 in the development of the sweetpotato storage root.

Expression pattern of SRD1 suggests its role in storage root development

SRD1 expression was found to be root specific and to increase in young storage root (Fig. 1). SRD1 mRNA was detected in the actively dividing vascular and cambium cells of the early-stage storage root, specifically in the secondary cambium cells (morphological characteristics of storage roots) (Fig. 3). This type of expression pattern suggests a role for SRD1 in the early stage of storage root development. To date, several MADS-box genes have been identified from sweetpotato. IbMADS3 and IbMADS4 are expressed preferentially in root tissues (fibrous roots, pigmented roots, and developing storage roots) (Kim et al., 2002), but they are also expressed in other vegetative tissues, including the flower, leaf, and stem. In constrast, IbMADS10 has been found to be specifically expressed in the pigmented tissues, such as the flower bud and pink and red roots (Lalusin et al., 2006). Ku et al. (2008) observed that IbMADS1 exhibited a root- (fibrous roots and developing storage roots) specific expression pattern, which is identical to the expression pattern of SRD1. In situ hybridization on the fibrous root revealed that IbMADS1 transcripts were specifically distributed around the immature meristematic cells, such as the protoxylem and protophloem, within the stele. However, these authors did not localize IbMADS1 transcripts in the storage root.

The identical tissue specificity and the high level of nucleotide sequence identity (99%) between IbMADS1 and SRD1 (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online) suggest the possibility that these two genes are orthologues. Taking into account that sweetpotato is a heterogeneous hexaploid plant, it is likely that SRD1 and IbMADS1 are allelic variants. However, a comparison of the overexpression studies of IbMADS1 and SRD1 in Arabidopsis reveals a significant morphological difference. Ku et al. (2008) reported that IbMADS1-overexpressing Arabidopsis showed no notable changes in either flowering time or the morphology of the floral organs. In contrast, SRD1-overexpressing Arabidopsis exhibited distinctive morphological alterations, including dwarfed floral organs, reduced length of the inflorescence stems, increased number of inflorescence stems, and roots with longer and more root hairs, as well as a delayed flowering time compared with the wild type (Supplementary Fig. S5). These observations suggest that although IbMADS1 and SRD1 show a high level of nucleotide sequence identity and an identical tissue specificity, they may function differently in sweetpotato. To understand further the relationship between SRD1 and IbMADS1, it will be necessary to characterize the two genes in more detail under the same experimental conditions.

SRD1 is involved in early-stage storage root development in an auxin-dependent manner

Potato tubers and sweetpotato storage roots are distinctly different in terms of origin, with tubers originating from the stem and storage roots originating from roots. However, the processes involved in the formation of a tuber and storage root share several common characteristics, including cessation of the longitudinal growth of the stolon tip or root, a change in the orientation of cell growth from elongation to expansion to enable radial growth, and an initiation of cell division and expansion for rapid thickening growth (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973; Ewing and Struik, 1992; Xu et al., 1998). Koda and Okazawa (1983) determined the levels of endogenous plant hormones in potato, including a gibberellic acid (GA)-like substance, auxin, and cytokinin, in relation to changes in morphological and cytological aspects. Based on their observations, these authors suggested that a decrease in GA content enhances swelling of the stolon and inhibits stolon elongation; subsequently, auxin supports stolon swelling due to cell expansion, and cytokinin stimulates cell division for rapid thickening growth. A more recent study by Faivre-Rampant et al. (2004) reported that auxin response factor 6 (ARF6), a key regulator of auxin-responsive genes, is involved in tuberization and tuber dormancy release in potato. The expression of ARF6 was shown to be repressed by auxin [naphthalenacetic acid (NAA)] treatment, and its steady-state expression level decreased by 10-fold upon transition from a longitudinal (transverse cell division) to a lateral (longitudinal cell division) stolon expansion. Thus, auxin most probably plays a role in tuber formation in potato.

It was demonstrated that the endogenous IAA level gradually increased during the early stage of storage root development (Fig. 5), suggesting that the early stage of storage root formation is an auxin-mediated process. This finding is in agreement with results reported in earlier studies of sweetpotato showing high levels of IAA in the early stages of storage root formation and a subsequent gradual decrease during the secondary thickening growth of the storage root (Akita et al., 1962; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1992). The SRD1 transcript level was shown to increase in the 5 mm diameter storage roots in response to increasing IAA content (Fig. 5), suggesting that SRD1 is involved in the auxin-mediated early stages of storage root formation. The transcript level of SRD1, however, remained unchanged in the pigmented fibrous root (diameter 1.5 mm) and thick root (diameter 3.0 mm), although the endogenous IAA level gradually increased. This finding indicates that a certain level of IAA is required for the up-regulation of SRD1 transcription and that this level is at a minimum critical concentration in the 5 mm diameter storage root. The presence of anomalous secondary cambium is a morphological characteristic of the storage root, and secondary meristem has been shown to be activated in the 5 mm diameter roots (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1991). The observation that the SRD1 transcript level increased only in the 5 mm diameter storage root suggests the possibility that the increased level of the SRD1 transcript is related to secondary cambium differentiation.

Overexpression of SRD1 enhanced the proliferation of cambium and metaxylem cells and stimulated thickening growth in fibrous roots

To elucidate the functional role of SRD1 in storage root development, SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants were generated and subsequently analysed. SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants cultured in vitro produced thicker fibrous roots with an increased diameter (Fig. 7B, C, D; Tables 1, 2). Microscopic observation of the SRD1-ox plants revealed that expansion growth and cell proliferation were more prevalent in the stele than in the cortex. This type of morphogenetic process (higher expansion growth in the stele than in the cortex) is normally observed during primary thickening growth in the sweetpotato storage root (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973). The number of cambium and metaxylem cells in SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants increased enormously relative to the wild type, resulting in an earlier thickening growth in fibrous roots. This multiplication of cambium and metaxylem cells was determined to be a morphological characteristic of thick roots and storage roots (Fig. 6). The most striking phenotype of the SRD1-ox plants was the appearance of secondary cambium cells around discrete protoxylem in SRD1-ox line 3 (Fig. 7C). The initial appearance of secondary cambium cells in thick roots has been reported to be a morphological marker for phase transition from the thick root to the storage root (Kokubu, 1973; Wilson and Lowe, 1973; Nakatani and Komeichi, 1991). These results therefore demonstrate that SRD1 plays a role in the initial formation of the storage root through an enhancement of proliferation activity in cambium and metaxylem cells.

To date, several attempts have been made to mine genes related to storage root development in sweetpotato (You et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2005, 2008). An extremely low efficiency in generating transgenic sweetpotato plants has been a bottleneck in designing studies that directly characterize the roles of sweetpotato genes using a gain- and/or loss-of function approach. Ku et al. (2008) employed a gain-of-function approach to demonstrate the role of IbMADS1 in storage root development by generating IbMADS1-ox potato plants. These authors observed that the fibrous roots of IbMADS-ox potato were partially swollen and that the metaxylem cells had undergone enhanced multiplication. However, no phenotype was observed in the cambium cells from IbMADS1-ox potato plants, and the phenotype observed in IbMADS1-ox potato plants was not confirmed in sweetpotato. Using SRD1-ox sweetpotato plants, it was possible to demonstrate that SRD1 is involved in the auxin-mediated initial thickening growth of storage root through an enhancement of metaxylem and cambium cell proliferation. As such, SRD1 is the first sweetpotato gene whose role in storage root development has been directly characterized in transgenic sweetpotato.

Supplementary data

The following Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence comparison between SRD1 and IbMADS1.

Fig. S2. Nucleotide sequence comparison among MADS-box cDNAs isolated from early-stage storage roots of sweetpotato.

Fig. S3. Verification of specificity of SRD1-specific primers.

Fig. S4. Identification of transgenic sweetpotato plants using PCR amplification.

Fig. S5. Morphological alteration in SRD1-overexpressing Arabidopsis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants (nos 20070301034017 and 20080401034022) from the BioGreen 21 Program funded by the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and a grant (no. 2009-0079297) from the Plant Signaling Network Research Center (SRC), MEST/KOSEF.

References

- Akita S, Yamamoto F, Ono M, Kusuhara M, Kobayashi H, Ikemoto S. Studies on the small tuber set method in sweet potato cultivation. Bulletin of the Chugoku National Agricultural Experiment Station. 1962;8:75–128. (in Japanese with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla ER, Liljegren SJ, Pelaz S, Gold SE, Burgeff C, Ditta GS, Vergara-Silva F, Yanofsky MF. MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. The Plant Journal. 2000;24:457–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonplod N. 2005. Changes in the concentration of particular hormones and carbohydrates in apple shoots after ‘bending’ respectively chemical treatments and relationship to flower induction process. PhD thesis, University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona MJ, Ortega N, Garcia-Maroto F. Isolation and molecular characterization of a new vegetative MADS-box gene from Solanum tuberosum L. Planta. 1998;207:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s004250050471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W, Niwa Y, Zeng W, Hirano T, Kobayashi H, Sheen J. Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Current Biology. 1996;6:325–330. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Zurek DM, McMorris TC, Baker ME. Effect of brassinolide on gene expression in elongating soybean epicotyls. Plant Physiology. 1992;100:1377–1383. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargeviciute A, Roux C, Decreux A, Sitbon F, Perrot-Rechenmann C. Molecular cloning and expression of the early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene family in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1998;39:993–1002. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi T, Kitano M, Eguchi H. Growth of sweetpotato tuber as affected by the ambient humidity. Biotronics. 1998;27:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi T, Yoshida S. Effects of application of sucrose and cytokinin to roots on the formation of tuberous roots in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) Plant Root. 2008;2:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing EE, Struik PC. Tuber formation in potato: induction, initiation and growth. Horticultural Reviews. 1992;14:89–198. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre-Rampant O, Cardle L, Marshall D, Viola R, Taylor MA. Changes in gene expression during meristem activation processes in Solanum tuberosum with a focus on the regulation of an auxin response factor gene. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:613–622. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Douglas D, David P, Mortley D, Trotman A, Bonsi C. Biomass accumulation in hydroponically grown sweetpotato in a controlled environment: a preliminary study. Acta Horticulturae. 1996;440:25–30. doi: 10.17660/actahortic.1996.440.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano Y, Ming ZJ. Effects of soil temperature on the thickening growth and the quality of sweetpotato during the latter part of their growth. Environment Control in Biology. 2000;38:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theißen G. MIKC-type MADS-domain protein: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene. 2005;347:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hamada T, Otani M, Shimada T. Isolation and characterization of MADS box genes possibly related to root development in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam) Journal of Plant Biology. 2005;48:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Mizuno K, Fujimura T. Isolation of MADS-box genes from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L) Lam.) expressed specifically in vegetative tissues. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2002;43:314–322. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koda Y, Okazawa Y. Characteristic changes in the levels of endogenous plant hormones in relation to the onset of potato tuberization. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1983;52:592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Kokubu T. Thermatological studies on the relationship between the structure of tuberous root and its starch accumulating function in sweet potato varieties. Bulletin of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University. 1973;23:1–126. (in Japanese with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Ku AT, Huang YS, Wang YS, Ma D, Yeh KW. IbMADS1 (Ipomoea batatas MADS-box 1 gene) is involved in tuberous root initiation in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) Annals of Botany. 2008;102:57–67. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalusin AG, Nishita K, Kim S-H, Ohta M, Fujimura T. A new MADS-box gene (IbMADS10) from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) is involved in the accumulation of anthocyanin. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2006;275:44–54. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretan PA, Bonsi CK, Mortley DG, Wheeler RM, Mackowiak CL, Hill WA, Morris CE, Trotman AA, David PP. Effects of several environmental factors on sweetpotato growth. Advances in Space Research. 1994;14:277–280. doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(94)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo T, Yoneda T, Itoo S. Identification of free cytokinins and the changes in endogenous levels during tuber development of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) Plant and Cell Physiology. 1983;24:1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Messenguy F, Dubois E. Role of MADS box proteins and their cofactors in combinatorial control of gene expression and cell development. Gene. 2003;316:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortley D, Hill J, Loretan P, Bonsi C, Hill W, Hileman D, Terse A. Elevated carbon dioxide influences yield and photosynthetic responses of hydroponically-grown sweetpotato. Acta Horticulturae. 1996;440:31–36. doi: 10.17660/actahortic.1996.440.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani M, Komeichi M. Changes in the endogenous level of zeatin riboside, abscisic acid and indole acetic acid during formation and thickening of tuberous roots in sweet potato. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1991;60:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani M, Komeichi M. Changes in endogenous indole acetic acid level during development of roots in sweet potato. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1992;61:683–684. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Pardales JR, Bañoc DM, Yamauchi A, Iijima M, Kono Y. Root system development of cassava and sweetpotato during early growth stage as affected by high root zone temperature. Plant Production Science. 1999;2:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y-K, Yum H, Kim E-S, Cho H, Gothandam KM, Hyun J, Chung Y- Y. BcXTH1, a Brassica campestris homologue of Arabidopsis XTH9, is associated with cell expansion. Planta. 2006;224:32–41. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Takahata Y, Nakatani M. Analysis of genes developmentally regulated during storage root formation of sweet potato. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2005;162:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Kato N, Nakayama H, Nakatani M, Takahata Y. Expression of class 1 Knotted1-like homeobox genes in the storage roots of sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) Journal of Plant Physiology. 2008;165:1726–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theissen G, Becker A, Di Rosa A, Kanno A, Kim JT, Münster T, Winter K-U, Saedler H. A short history of MADS-box genes in plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;42:115–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theißen G. Development of floral organ identity: stories from the MADS house. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2001;4:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heerden PDR, Laurie R. Effects of prolonged restriction in water supply on photosynthesis, shoot development and storage root yield in sweet potato. Physiologia Plantarum. 2008;134:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang L, Guan Y, Wang Z. Endogenous hormone concentration in developing tuberous roots of different sweet potato genotypes. Agricultural Science in China. 2006;5:919–927. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LA, Lowe SB. The anatomy of the root system in west indian sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) cultivars. Annuls in Botany. 1973;37:633–643. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Vreugdenhil D, van Lammeren AAM. Cell division and cell enlargement during potato tuber formation. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:573–582. [Google Scholar]

- You MK, Hur CG, Ahn YS, Suh MC, Shin JS, Bae JM. Identification of genes possibly related to storage root induction in sweetpotato. FEBS Letters. 2003;536:101–105. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.