Abstract

Synapses throughout the brain are modified through associative mechanisms in which one input provides an instructive signal for changes in the strength of a second co-activated input. In cerebellar Purkinje cells, climbing fiber synapses provide an instructive signal for plasticity at parallel fiber synapses. Here we show that noradrenaline activates α2-adrenergic receptors to control short-term and long-term associative plasticity of parallel fiber synapses. This regulation of plasticity does not reflect a conventional direct modulation of the postsynaptic Purkinje cell or presynaptic parallel fibers. Instead, noradrenaline reduces associative plasticity by selectively decreasing the probability of release at the climbing fiber synapse, which in turn decreases climbing fiber-evoked dendritic calcium signals. These findings raise the possibility that targeted presynaptic modulation of instructive synapses could provide a general mechanism for dynamic context-dependent modulation of associative plasticity.

Keywords: climbing fiber, Purkinje cell, cerebellum, α2-adrenergic receptors, LTD, endocannabinoids

Introduction

Associative synaptic plasticity is a candidate substrate for the formation of real-world associations (Hebb, 1949). Synaptic plasticity typically requires precisely timed co-activation of a presynaptic input with postsynaptic events including depolarization and elevation of dendritic calcium (Abbott and Nelson, 2000; Bi and Poo, 2001; Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). Induction of associative plasticity is often triggered by instructive synaptic inputs that influence the state of the postsynaptic cell (Blair et al., 2001; Dudman et al., 2007; Ito, 2001). A great deal is known about how postsynaptic spiking, and the presynaptic and postsynaptic properties of the synapses being modified, control the induction of associative plasticity (Duguid and Sjostrom, 2006; Malenka and Bear, 2004; Nicoll, 2003; Seol et al., 2007). Much less is known about whether associative plasticity can be controlled by modulating instructive synaptic inputs.

Cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs) are well suited to studying the role of instructive synapses in the regulation of associative plasticity. PCs receive two very different classes of excitatory inputs: weak synaptic inputs from roughly 100,000 granule cell parallel fibers (PFs) (Eccles et al., 1966b), and a strong synaptic input from a single climbing fiber (CF) (Eccles et al., 1966a). The CF provides an important instructive signal that controls the induction of associative plasticity at the PF synapse and which is thought to be important for motor learning (Gilbert and Thach, 1977; Kitazawa et al., 1998; Raymond and Lisberger, 1998). Activation of the CF synapse elicits a characteristic postsynaptic complex spike that elevates calcium throughout PC dendrites (Schmolesky et al., 2002). Activation of PFs followed by complex spikes within several hundred milliseconds leads to rapid synaptic suppression resulting from endocannabinoid release from PCs and retrograde activation of type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptors (Brenowitz and Regehr, 2005). Repetition of this stimulus for minutes induces cerebellar long-term depression (LTD) of PF synapses onto PCs (Ito, 2001; Safo and Regehr, 2005). Previous studies have suggested that altering the strength of CF inputs to PCs can provide a way to control the induction of associative plasticity (Coesmans et al., 2004), but the circumstances under which such regulation might occur remain unclear.

The cerebellum receives monoaminergic inputs from neuromodulatory centers throughout the brain. They, together with mossy fibers and CFs, comprise the three classes of cerebellar afferent input, and are a relatively poorly understood element of the cerebellar circuitry (Schweighofer et al., 2004). Anatomical studies indicate that noradrenergic fibers originate in the locus coeruleus and course through all layers of the cerebellar cortex (Bloom et al., 1971; Hokfelt and Fuxe, 1969; Kimoto et al., 1978; Olson and Fuxe, 1971; Schroeter et al., 2000), forming varicosities closely apposed to PC dendrites (Landis and Bloom, 1975). Noradrenergic inhibition of PCs can be elicited through electrical stimulation of the locus coeruleus in vivo (Siggins et al., 1971b). Perturbation of noradrenergic inputs to the cerebellum interferes with cerebellum-dependent forms of motor learning (Galeotti et al., 2004; Keller and Smith, 1983; McCormick and Thompson, 1982; Pompeiano, 1998; Watson and McElligott, 1984).

Here we ask whether neuromodulation can control the induction of associative plasticity through selective regulation of instructive signals conveyed to Purkinje cells by climbing fibers. We find that noradrenaline acts through α2-adrenergic receptors to decrease the probability of release at the CF synapse. This in turn decreases CF-evoked dendritic calcium transients and interferes with the induction of short-term and long-term associative plasticity of PF synapses. We conclude that noradrenaline controls synaptic plasticity of PF synapses through selective regulation of instructive signals, thereby providing a mechanism that could allow for dynamic, context-dependent regulation of learning.

Results

NA decreases release probability at CF synapses by activating α2-adrenergic receptors

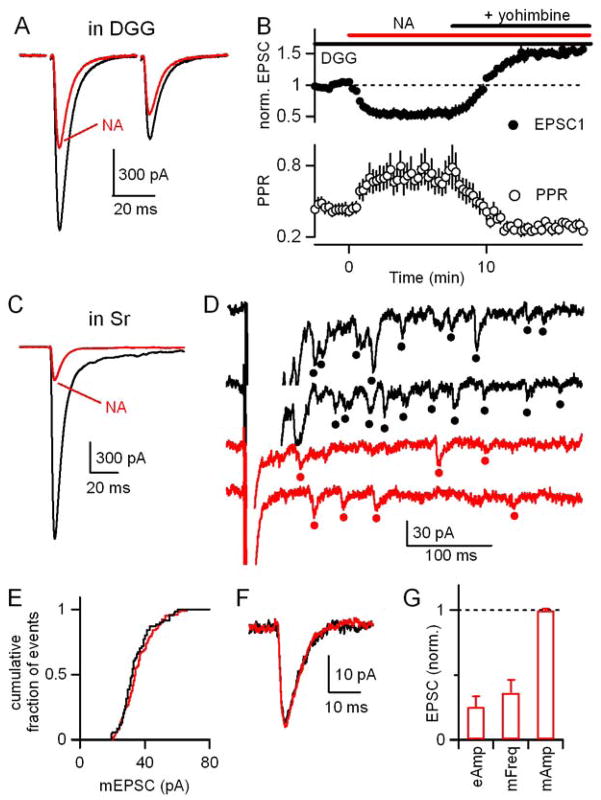

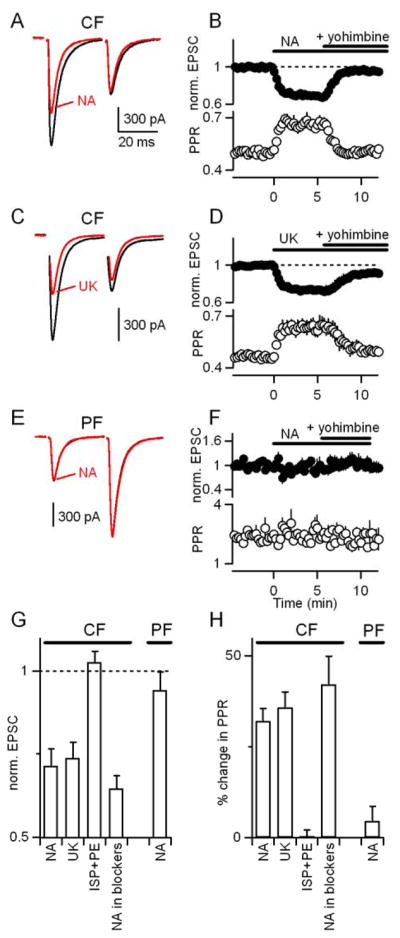

We examined synaptic responses in Purkinje cells by making whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings with a Cs-based internal solution to minimize the contributions of active postsynaptic conductances. Climbing fibers were stimulated with pairs of stimuli separated by 30 ms. In control conditions, CF-EPSCs exhibited marked paired-pulse depression as previously described (Eccles et al., 1966a). The effects of NA (5 μM) on the CF-EPSC are shown (Fig. 1A). NA decreased the EPSC amplitude and increased the paired-pulse ratio by 29±5% (n=6, p<0.01) and 32±3% respectively (n=6, p<0.01) (Fig. 1B). This decrease in paired-pulse depression is consistent with NA acting presynaptically to decrease the probability of release at the CF synapse (Foster and Regehr, 2004; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Maejima et al., 2001; Wadiche and Jahr, 2001).

Figure 1. Noradrenaline decreases EPSC amplitude at the climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapse through activation of α2-adrenergic receptors.

(A–D) Voltage-clamp recordings of CF-EPSCs in PCs in response to pairs of CF stimuli separated by 30 ms. (A) EPSCs from a representative experiment are shown in control conditions (black) and in the presence of 5 μM NA (red). (B) Effects of NA and subsequent application of the α2-receptor antagonist yohimbine (15 μM) on the first EPSC (filled circles) and paired-pulse ratio (open circles) are summarized (n=6). (C,D) Experiments similar to those in (A, B) are shown with the exception that the α2-receptor agonist UK14304 (15 μM) is used rather than NA (n=5). (E, F) PFs were activated with a pair of stimuli separated by 30 ms and the resulting EPSCs were recorded from PCs in voltage-clamp with a Cs-based internal solution in control conditions, in the presence of NA, and in the presence of both NA and 15 μM yohimbine (n=5). Responses are normalized to the average amplitude of the first EPSC, before drug application. (G,H) Summary of effects on the first CF-EPSC (G) and paired pulse ratio (H) of: NA; UK14304; the α1- and β-adrenergic receptor agonists phenylephrine and isoproterenol (10 μM each, n=6); and NA in the presence of a cocktail of antagonists for CB1Rs (AM251, 5 μM), adenosine A1Rs (DPCPX, 5 μM), type I/II mGluRs (MCPG, 500 μM), and GABABRs (CGP 55845A, 2 μM) (n=4). Responses are normalized to the amplitude of the first EPSC in control conditions (dashed line).

We used selective agonists and antagonists to pharmacologically characterize the involvement of various adrenergic receptors in modulating CF-EPSCs. α1, α2, and β adrenergic receptors are expressed in cerebellum (Nicholas et al., 1996). Previous studies have shown that β adrenergic receptors can modulate PC output through direct postsynaptic effects on PCs (Hoffer et al., 1971; Siggins et al., 1971a) as well as through the augmentation of GABAergic inhibition of PCs (Mitoma and Konishi, 1999; Yeh and Woodward, 1983). We found that the α2-receptor agonist UK14304 mimicked the effects of noradrenaline and the α2-receptor antagonist yohimbine reversed the effects of noradrenaline on the amplitude and paired-pulse ratio of CF-EPSCs (Fig. 1C,D). UK14304 reduced EPSC amplitude and paired-pulse depression to a similar extent as NA (26±4% decrease in EPSC1 and a 36±4% increase in PPR, n=5, p=.87, Fig. 1D). In contrast, application of the α1 and β-adrenergic receptor agonists phenylephrine and isoproterenol (10 μM each) did not affect EPSC amplitude or paired-pulse ratio (Fig. 1G,H). Thus, the decrease in probability of release at CF synapses by noradrenaline is mediated by α2-adrenergic receptors.

Previously described modulators of the CF synapse, including activation of mGluRs, CB1Rs, adenosine receptors, and GABABRs, lack specificity, modulating PF-PC inputs to an even larger degree (Glaum et al. 1992; Hashimoto and Kano, 1998; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Maejima et al., 2001; Takahashi and Linden, 2000; Takahashi et al., 1995). A previous study using field recordings in mice has suggested that α2-receptor activation can cause a small (up to 18% with 100 μM NA) reduction of PF synapses (Zhou et al. 2003). We therefore asked whether the adrenergic modulation of CF-EPSCs we observe was specific to climbing fibers, or whether parallel fiber-to-Purkinje cell synapses were also subject to this modulation. We assessed the effects of α2-receptor activation on PF synapses in voltage-clamp with a Cs-based internal solution, and found that neither NA nor yohimbine significantly altered the amplitude or paired-pulse ratio of PF-EPSCs (Fig. 1E–H).

Neuromodulators can either act directly or indirectly to modulate transmission (Maejima et al., 2001; Varma et al., 2001; Vogt and Regehr, 2001). We therefore determined whether activation of α2-adrenergic receptors indirectly modulated release at CF synapses through other signaling systems and receptors (Hashimoto and Kano, 1998; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Kulik et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 1995). Coapplication of antagonists of type II mGluRs, GABABRs, adenosine A1Rs, and cannabinoid CB1Rs (MCPG, 500 μM; CGP 55845A, 2 μM; DPCPX, 5 μM; AM251, 5 μM) did not affect the ability of NA to decrease the EPSC and alter paired-pulse plasticity (Fig. 1G,H; 36±4% suppression in blockers vs. 29±5% in control, n=7, p=0.31). This indicates that noradrenaline does not act indirectly in a manner that requires the activation of any of these signaling systems and is consistent with noradrenaline decreasing the probability of release by acting directly on CF terminals.

Together, these findings (Fig. 1) indicate that NA selectively decreases the amplitude and increases the PPR of CF-EPSCs by activating α2-receptors.

Mechanism of noradrenergic suppression of CF synapses

The decrease in paired-pulse depression of CF-EPSCs is consistent with α2-adrenergic receptors acting presynaptically to decrease transmitter release (Foster and Regehr, 2004; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Maejima et al., 2001; Takahashi and Linden, 2000; Wadiche and Jahr, 2001), as at other synapses (Bertolino et al., 1997; Delaney et al., 2007; Hein, 2006; Langer, 1977; Leao and Von Gersdorff, 2002). However, transmission at the powerful CF synapse is influenced by postsynaptic saturation of AMPA receptors, which could potentially make it difficult to distinguish between postsynaptic and presynaptic sites of modulation (Wadiche and Jahr, 2001). We therefore used two additional approaches to further investigate the mechanism of noradrenergic suppression of the CF synapse.

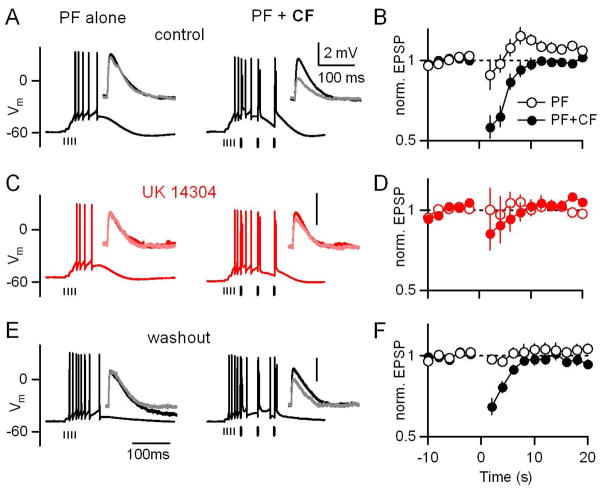

First, we used the rapid, low affinity AMPA receptor antagonist DGG to relieve postsynaptic receptor saturation and provide a more accurate readout of presynaptic glutamate release (Wadiche and Jahr, 2001; Foster et al. 2002). When NA was applied in the presence of DGG, we found that CF-EPSCs were more strongly suppressed by NA than in control conditions (Fig. 2A,B vs. Fig. 1A,B; 42±5% suppression in DGG vs. 29±5%, suppression in control, n=7). Similarly, NA increased the paired-pulse ratio to a larger extent in DGG compared to control (60±6% increase in DGG vs. 32±3% increase in control). The greater effect of NA in the presence of DGG suggests that NA causes a presynaptic decrease in glutamate release. Interestingly, in the presence of DGG, the α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist yohimbine not only blocked the effect of NA, but caused an enhancement of synaptic transmission relative to control conditions (Fig. 2B). This finding is consistent with the observation that by relieving saturation, DGG unmasks the effects of modulators that increase release at the high-p CF synapse (Foster et al. 2002). The enhancement of CF synaptic strength in yohimbine could be due to inverse agonist properties of the drug (Murrin et al. 2000) or tonic α2-receptor activation in control conditions.

Figure 2. Noradrenaline decreases release probability at the CF-PC synapse.

(A,B) Effects of NA on CF-EPSCs recorded from PCs in the presence of the rapid low-affinity AMPA receptor antagonist DGG (n=7). Data are plotted as in Figure 1. (C–G) Effects of NA on CF-EPSCs recorded with an external recording solution in which calcium was replaced with strontium. (C–F) A representative experiment shows responses in control conditions (black) and in the presence of NA (red) for the average CF-EPSCs (C), individual traces showing asynchronous release events (filled circles) (D), cumulative histograms (E), and average quantal events (F). (G) The effects of NA on the evoked CF-EPSC (eEPSC) amplitude, the amplitude of the quantal events, and the frequency of evoked quantal events in the presence of strontium are summarized (n=6 PCs).

Second, to further distinguish between presynaptic and postsynaptic effects of NA at the CF synapse, we measured the effect of NA on miniature CF-EPSC amplitude and frequency. To do this, we replaced the calcium in our extracellular recording solution with strontium (Fig 2C–2G). In the presence of strontium, vesicles are released asynchronously (Miledi 1966; Augustine and Eckert, 1984; Goda and Stevens 1994; Xu-Friedman and Regehr 1999). The prolongation of release in response to a CF stimulus allows us to isolate CF-mEPSCs from PF-mEPSCs and measure amplitude and frequency of miniature CF synaptic events (Otis et al., 1997). In the presence of Sr, NA greatly reduced the evoked EPSC amplitude (Fig. 2C) and the frequency of CF-mEPSCs (Fig. 2D, red vs. black; Fig. 2G; 64±10% reduction in mini frequency), but did not affect the amplitude of CF-mEPSCs (Fig. 2E–2G; 0±1% change, p=0.72, paired T-test). This suggests that NA acts presynaptically to reduce mEPSC frequency and does not affect the postsynaptic sensitivity of AMPA receptors. Further, because of the reduction in synchronous release together with the fact that strontium is less effective than calcium at driving transmitter release overall (Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2000), strontium relieves both presynaptic and postsynaptic saturation at the CF synapse (Foster et al. 2002). This removal of saturation predicts that presynaptic decreases in release probability in the presence of strontium would be more pronounced than in either control conditions or in the presence of DGG, where only postsynaptic saturation is relieved. Consistent with that prediction, we found that NA caused an even greater reduction in CF-EPSC amplitude than it did in DGG (Fig. 2C vs. Fig. 2A, 75±8% in strontium vs. 42±5% in DGG). Thus, multiple lines of evidence indicate that NA acts presynaptically to reduce the probability of release at CF synapses.

Noradrenaline alters complex spike waveform and associated calcium elevation

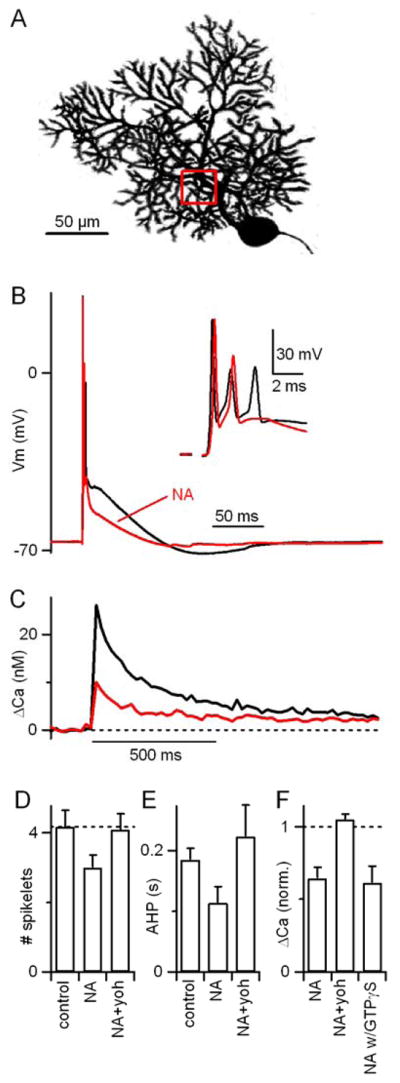

Given the multivesicular release and postsynaptic AMPAR saturation at the CF synapse, and the high safety factor of the CF synapse, it was not clear whether the noradrenergic modulation of the CF synapse would influence postsynaptic complex spikes in Purkinje cells (Pisani and Ross, 1999). To test this possibility, whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made from PCs with a potassium-based internal solution containing the fluorescent calcium indicator fura-2 (200 μM, Fig. 3). An electrode placed in the granule cell layer stimulated CFs and elicited characteristic PC complex spikes (Fig. 3B, black), which involve widespread depolarization and the activation of calcium, sodium, and potassium conductances (Schmolesky et al., 2002). As shown for a representative experiment, we found that noradrenaline (5 μM) had clear effects on the complex spike waveform, decreasing the number of evoked spikelets, the plateau depolarization, and the afterhyperpolarization (Fig. 3B, red). Simultaneous calcium imaging revealed that CF activation transiently elevated calcium throughout PC dendrites (Fig. 3C, black trace), and that NA reduced the CF-evoked dendritic calcium transient (Fig. 3C, red trace). Across cells, NA significantly reduced the number of spikelets, the duration of the after-hyperpolarization (Fig. 3D, n=6, p < 0.01, paired T-test) and the amplitude of dendritic calcium transients in PCs (reduced to 64±8% of control, Fig. 3E, n=6, p < 0.05, paired T-test). NA modulation of dendritic calcium did not depend on the region imaged, whether proximal vs. distal or thick vs. thin dendritic branches.

Figure 3. Noradrenaline alters climbing fiber-evoked complex spikes and associated Purkinje cell dendritic calcium signals.

(A) A two-photon image of a PC highlighting the region of interest for measurement of dendritic calcium signals. (B,C) A representative experiment is shown in which a CF was stimulated and the resulting complex spike waveforms (B), complex spike spikelets (B, inset) and dendritic calcium transients (C) were simultaneously recorded from a PC in control conditions (black) and in the presence of 5 μM NA (red). (D) Summary (n = 6 PCs) of noradrenergic effects on the number of complex spike spikelets and (E) the duration of the after-hyperpolarization. (F) Effects of NA on dendritic calcium transients in the same PCs. Peak calcium transients in the presence of NA, following subsequent addition of the α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist yohimbine (15 μM), and in the presence of NA with GTPγS (n=6) included in the internal recording solution are each shown normalized to control conditions. NA caused a decrease in CF-evoked calcium elevation that was reversed by coapplication of yohimbine but unaffected by GTPγS.

The alteration in CF-evoked responses by noradrenaline could reflect either changes in the properties of the CF synapse or changes in any of the active conductances in PCs that generate the complex spike. We next asked whether the effects of noradrenaline on CF-evoked complex spikes and dendritic calcium transients could be accounted for by the presynaptic modulation of the CF synapse that we described in Figs. 1 and 2. We found that the effects of noradrenaline on complex spikes and postsynaptic calcium transients were also reversed by yohimbine (Fig. 3D–3F), indicating that they, like the effects on CF-EPSCs, were mediated by α2-receptors. To assess possible postsynaptic effects of α2-receptors (Nicholas et al., 1996; Scheinin et al., 1994), which are coupled to Gi/o type G proteins (Hein, 2006), we substituted the non-hydrolyzable GTPγS for the GTP in our internal solution. GTPγS did not affect the ability of noradrenaline to modulate CF-evoked calcium transients (Fig. 3F; reduced to 61±11% of control with GTPγS vs. 64±8% of control with GTP, p=.85, n=6). However, it did block the endocannabinoid-mediated suppression of CF synapses triggered by the mGluR1 agonist DHPG that is known to require postsynaptic G-proteins (Maejima et al., 2001; 42±3% suppression in control conditions vs. 1±3% with GTPγS, n=3 each). Thus, the effects of noradrenaline on CF-evoked complex spikes and dendritic calcium transients appear to result from the presynaptic decrease in transmitter release probability that is mediated by α2-receptors.

Neuromodulation of the CF synapse disrupts short-term associative plasticity

CFs play a central role in inducing associative synaptic plasticity in PCs (Ito, 2001). PF activity followed within a few hundred milliseconds by CF activation has been shown to induce short-term associative plasticity at PF synapses (Brenowitz and Regehr, 2005). This plasticity involves endocannabinoid release from PCs and activation of presynaptic CB1Rs, leading to the modulation of presynaptic calcium channels and the suppression of presynaptic transmitter release at PF synapses (Brown et al., 2004; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001).

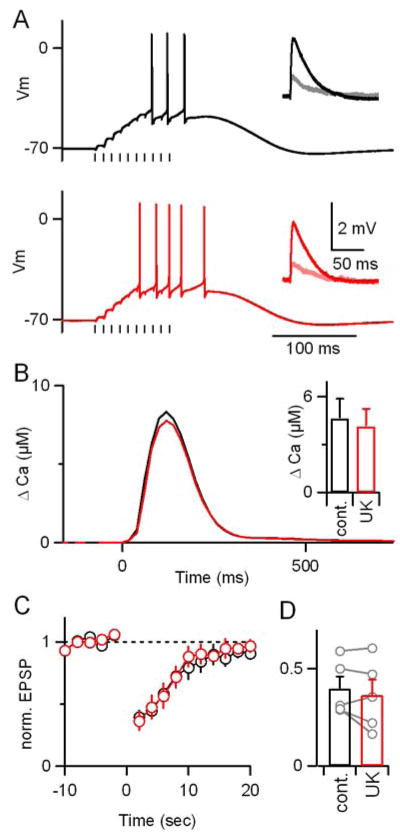

We investigated whether α2-receptor-mediated modulation of the CF synapse could regulate short-term associative plasticity. We made whole cell current-clamp recordings from PCs at 34°C with a potassium-based internal solution. PF-EPSPs were measured with test pulses presented at 0.5 Hz before and after a conditioning train that consisted of a burst of PF-stimuli, either alone or followed by 3 CF-stimuli (Fig. 4A). The amplitudes of PF-EPSPs before and after the conditioning trains were compared. PF-only trains generally result in post-tetanic potentiation, a transient enhancement of PF-EPSPs (Beierlein et al., 2007; Zucker and Regehr, 2002). When the number of PF stimuli is increased, the enhancement can be overcome by endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic suppression (Brown et al., 2003). For these experiments, we adjusted the number of PF stimuli in the conditioning trains (3 to 7 stimuli) to produce minimal enhancement or suppression of the EPSP when presented alone (Fig. 4A inset, black vs. gray). In control conditions, PF+CF conditioning trains resulted in a transient 42±7% suppression of PF-EPSP amplitude (Fig. 4A and 4B), while PF-only conditioning trains did not (Fig. 4A and 4B).

Figure 4. α2-receptor activation disrupts associative short-term plasticity.

PF-EPSPs were measured with test pulses presented at 0.5 Hz before and after conditioning trains consisting of either stimulation of PFs only or PFs and CFs. (A,C,E) Responses of a PC to a PF-only train (left) and PF+CF trains (right) are shown for control conditions (A), in the presence of the α2 agonist UK14304 (15 μM, C, red), and after drug washout (E). Vertical lines beneath traces indicate timing of PF (thin) and CF (thick) stimuli. Insets display the PF-EPSPs measured in response to test pulses before (dark) and after (light) conditioning trains. (B,D,F) Summary (n=7 PCs) of average PF-EPSP amplitudes in response to test pulses before and after conditioning trains that were delivered at time 0. Responses are normalized to the average EPSP amplitude before the conditioning train. PF+CF trains (filled symbols) resulted in greater suppression of PF-EPSP amplitude than PF-only trains (open symbols). The suppression resulting from PF+CF trains was selectively reduced by UK14304.

We examined the effect of α2-adrenergic receptor activation on short-term associative plasticity (Fig. 4C and 4D). α2-adrenergic receptor activation did not affect the balance between short-term enhancement and suppression observed following presentation of PF-only conditioning trains, but significantly reduced the synaptic suppression observed following PF+CF trains, from 42±7% to 15±11% (n=7, p<0.05, paired T-test). The decrease in associativity caused by α2-receptor activation was reversed upon drug washout (Fig. 4E and 4F). Thus, activation of α2-adrenergic receptors interfered specifically with the induction of associative short-term plasticity at PF-PC synapses.

The selective disruption of associative plasticity observed during activation of α2-receptors is consistent with its selective suppression of CF synapses (Fig. 1), and suggests that any effects α2-receptors may have on PF synapses (Zhou et al. 2003) are not sufficient to impair plasticity. However, it remains possible that α2-receptors in PCs (Nicholas et al., 1996; Scheinin et al., 1994) might interfere with plasticity through postsynaptic actions such as regulation of dendritic excitability (Rancz and Hausser, 2006) that might only be revealed during stimulus conditions that cause plasticity. To address this question, we performed experiments similar to those in Fig. 4, but with conditioning trains consisting of 10 PF stimuli, which are sufficient to evoke short-term suppression of excitation (SSE, Fig. 5, Brown et al., 2003).

Figure 5.

Parallel fiber plasticity and postsynaptic calcium elevations are not affected by α2 receptor activation. (A,B) A representative experiment is shown in which PFs were activated with test pulses presented at 0.5 Hz and the resulting PF-EPSPs were recorded from PCs in current-clamp with a K-based internal solution. Conditioning trains consisted of 10 PF stimuli at 100 Hz. (A) Responses to the conditioning trains and PF-EPSPs before and after the conditioning trains (insets) were measured in control conditions (top, black) and in the presence of 15 μM UK14304 (bottom, red). (B) Local dendritic calcium signals were measured in response to the conditioning train. Inset, summary (n=5). (C,D) Summaries (n=5) of the time course of PF-EPSP amplitude (C) and the amount of EPSC suppression (D) in control conditions (black) and in the presence of UK14304 (red).

SSE is extremely similar to short-term associative plasticity involving CF and PF activation, with the exception that additional PF stimuli obviate the need for CF activation to evoke endocannabinoid release from the postsynaptic cell. If the noradrenergic effects on associative short-term plasticity were due to postsynaptic actions such as a decrease in calcium influx through postsynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels, then α2-receptor activation should affect SSE as well. We compared PC responses to PF-conditioning trains in control conditions and in the presence of an α2-receptor agonist. For these experiments, the internal recording solution was supplemented with 500 μM Fura-FF to measure localized dendritic calcium transients in response to PF-trains. As shown for a representative experiment, there was no change in the response to the conditioning train as assessed electrophysiologically (Fig. 5A, black vs. red) or with measurements of the local calcium signal in PC dendrites (Fig. 5B). The magnitude of suppression following the conditioning train was also unaffected (Fig. 5A, insets). The lack of effect of α2-receptor activation on PF responses and plasticity was consistent across cells (Fig. 5B–D; 44±8% suppression vs. 41±6% in control, n=5). This important control experiment demonstrates that α2-receptor activation does not affect the ability of PF-PC synapses to undergo plasticity generally, but rather specifically blocks the induction of associative plasticity, consistent with its suppression of climbing fiber instructive signals.

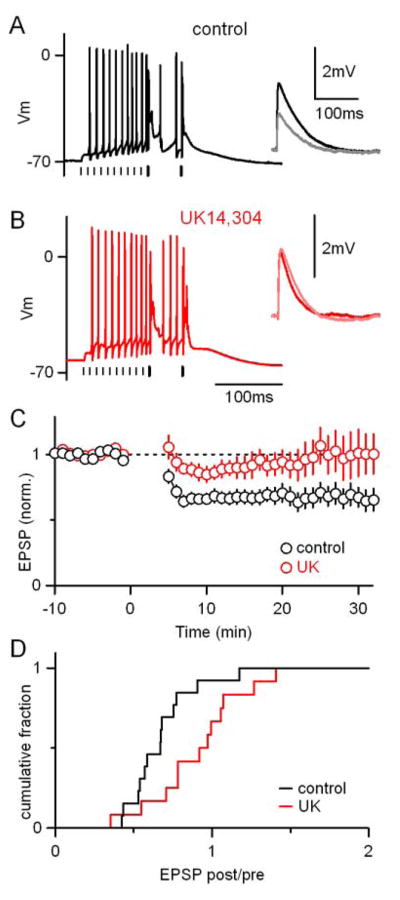

Activation of α2-receptors interferes with the induction of PF-LTD

CFs also play an instructive role in the induction of long-term associative plasticity in PCs. The repeated coactivation of PFs and CFs leads to the induction of LTD at PF-PC synapses (Ito, 2001). We asked whether modulation of the CF synapse by α2-receptor activation could regulate the induction of PF-LTD. The instructive signal provided by the CF is necessary for the induction of LTD for most induction protocols, including the one used here (Safo and Regehr, 2005): PF activation (10 at 100Hz) followed by CF activation (2 at 20 Hz) repeated every 10 s for 5 minutes (Fig. 6A and 6B).

Figure 6.

Activation of α2-receptors interferes with the induction of associative LTD at PF-to-PC synapses. (A) A representative experiment is shown in which LTD was induced with a protocol consisting of a train of 10 PF stimuli at 100 Hz followed by 2 CF stimuli at 20 Hz. This conditioning train was repeated 30 times every 10 seconds. Vertical lines beneath traces indicate timing of PF (thin) and CF (thick) stimuli. (A, inset) Average PF-EPSPs measured for the 5 min. before (black) and 15–20 min. after (gray) the induction protocol. (B) A separate representative experiment conducted in the presence of 15 μM UK14304 is shown. (C) Summary of the time course and amplitude of LTD in control conditions (n=13, black) and in the presence of UK14304 (n=12, red). (D) Cumulative histogram of the ratio of EPSP amplitudes 6–30 min. after/0–10 min. before LTD induction.

PF-EPSP amplitudes were monitored with test pulses presented at 0.1 Hz before and after the induction protocol as shown for two representative experiments (Fig. 6A and 6B, insets). In control conditions the induction protocol resulted in long-term depression of PF-EPSP amplitude (Fig. 6A, black). In the presence of an α2-receptor agonist (Fig. 6B), the conditioning trains produced similar responses in PCs, but did not result in LTD (Fig. 6B, inset). Across cells the long-term changes in PF-EPSPs were more variable, and significantly less likely to result in LTD in the than in control conditions (p<0.05, Fig. 6C and 6D). On average, LTD was eliminated, and in some cases LTP was observed, consistent with a previous study in which decreases in CF synaptic strength increase the likelihood of observing LTP vs. LTD at PF synapses (Coesmans et al., 2004). Thus, activation of α2-receptors disrupts the induction of associative long-term depression at PF-PC synapses.

Discussion

Here we have shown that noradrenaline controls PC associative synaptic plasticity through activation of α2-adrenergic receptors. Activation of these receptors potently modulates CF-PC synapses. A decrease in release probability at the CF-PC synapse reduces CF-evoked postsynaptic dendritic calcium transients and interferes with the induction of short- and long-term associative plasticity at PF-PC synapses. In contrast to the dramatic effects on CF-PC synapses, PF-PC synapses were not significantly affected by noradrenaline, and α2-receptor activation did not interfere with the induction of non-associative forms of plasticity at this synapse. We conclude that noradrenaline controls the induction of associative plasticity in Purkinje cells through targeted modulation of instructive climbing fiber synapses.

Mechanism

Although it is difficult to entirely rule out possible additional postsynaptic effects of α2-receptor activation, there are several arguments that suggest that the modulation of CF synapses that we observe accounts for the reduction in associative plasticity. First, we demonstrated that NA acts presynaptically to decrease release probability at CF, but not PF synapses (Figs. 1 and 2). Second, we found that the noradrenergic reduction in dendritic calcium elevation associated with complex spikes was independent of postsynaptic G-protein signaling (Fig. 3F). Third, α2-receptor activation interfered selectively with the induction of associative plasticity, and did not affect homosynaptic short-term plasticity following a burst of parallel fiber activation (Figs. 4 and 5).

Several lines of evidence suggest that NA acts directly on CF terminals to decrease glutamate release at CF synapses. First, experiments in DGG allowed us to assess modulation without complications due to postsynaptic saturation or desensitization, and these postsynaptic mechanisms do not underlie the modulation by NA (Fig. 2A,B). Second, in the presence of strontium, the decrease in CF-mini frequency and the lack of effect on mini amplitude strongly suggest that NA decreases release probability without altering the responsiveness of AMPA receptors (Fig. 2D–G). Third, NA did not act through any indirect pathways known to modulate CF-EPSCs (Fig. 1G,H). Finally, previous studies have provided evidence that α2-adrenergic receptors are expressed in neurons within the inferior olive that give rise to CF afferents (Tavares et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1996; Strazielle et al., 1999).

Our findings establish a new way by which modulatory systems can regulate endocannabinoid-mediated mechanisms of associative plasticity. As is the case for short- and long-term plasticity of PF-PC synapses, many forms of associative plasticity throughout the brain are mediated by endocannabinoids (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Endocannabinoid release is directly regulated by Gq-coupled receptors such as group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, oxytocin receptors, and some types of muscarinic and serotonin receptors (Best and Regehr, 2008; Kim et al., 2002; Maejima et al., 2001; Oliet et al., 2007). Here, we find that noradrenaline also interacts with the cannabinoid signaling system, but through an entirely different mechanism. The coupling is indirect and arises from modulation of the instructive signal that gates endocannabinoid release by controlling dendritic calcium levels.

Functional relevance

It had not been clear whether regulation of CF synapses could provide a means of specifically and dynamically controlling the induction of associative plasticity at PF synapses. Transmission at the powerful CF synapse has traditionally been regarded as an all-or-none phenomenon, although spontaneous variations in complex spike waveform have been observed in vivo (Gilbert, 1976). A series of recent studies showed that long-term reductions in the strength of the CF synapse (CF-LTD) can reduce CF-evoked postsynaptic calcium transients and increase the probability of inducing LTP vs. LTD at PF synapses (Coesmans et al., 2004; Hansel and Linden, 2000; Weber et al., 2003). However, CF-LTD requires stimulation at 5 Hz for 30 seconds, well outside the 1–2 Hz average range observed in vivo (Gilbert and Thach, 1977; Raymond and Lisberger, 1998). Our finding that noradrenaline controls the induction of associative plasticity at PF synapses through regulation of CF inputs raises the possibility that activity in locus coeruleus neurons could dynamically regulate associative plasticity based on behavioral context (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005).

Although other modulators of CF synapses have been identified, including cannabinoids, adenosine, and activation of GABAB and Group II mGluR receptors, they also profoundly and directly suppress PF synapses and are not suited to the selective regulation of associative plasticity (Glaum et al. 1992; Hashimoto and Kano, 1998; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Maejima et al., 2001; Takahashi and Linden, 2000; Takahashi et al., 1995). In contrast, noradrenaline is highly selective for instructive CF synapses (Fig. 1). We have also found that dopamine can regulate CF synapses (Supplementary Fig. 1), which suggests that multiple modulatory inputs to the cerebellum may target CFs to regulate associative plasticity in the cerebellar cortex.

Manipulation of noradrenergic inputs to the cerebellum has been shown to interfere with cerebellum-dependent motor learning (Keller and Smith, 1983; McCormick and Thompson, 1982; Pompeiano, 1998; Watson and McElligott, 1984). These findings have generally been attributed to previously-described inhibitory effects of noradrenaline on PC firing (Cartford et al., 2004; Gilbert, 1975; Schweighofer et al., 2004). Our results suggest that dysregulation of the cerebellar noradrenergic system could disrupt motor control and learning by interfering with CF control of plasticity at the PF-PC synapse.

Behavioral studies have linked α2-receptor signaling to cerebellum-dependent motor control. In humans, the α2-receptor agonist clonidine, which is used therapeutically for treatment of blood pressure, can have motor side-effects. In mice, clonidine can cause both decreased locomotion and impaired rotarod performance (Capasso et al., 1996; Dogrul and Uzbay, 2004). Intriguingly, mice treated with clonidine were unable to improve their rotarod performance with training (Galeotti et al., 2004), precisely the type of motor learning deficit that would be predicted by cerebellar motor learning theories based on our findings of suppressed instructive signals.

The noradrenergic regulation of CF-PC synapses described here demonstrates that modulation of purely instructive synapses can control associative plasticity. Many other types of neurons also receive anatomically distinct classes of excitatory inputs. For example, thalamic neurons receive sensory input and cortical feedback, CA3 pyramidal cells receive mossy fiber inputs and associational/commissural inputs, CA1 pyramidal cells receive perforant path and Schaffer collateral inputs and cortical cells receive thalamic inputs and recurrent excitatory collaterals (Amitai, 2001; Dudman et al., 2007; Jones, 2002; Sillito et al., 2006; Zalutsky and Nicoll, 1990). Moreover, different inputs are often selectively modulated (Giocomo and Hasselmo, 2007). In many cases it is thought that one class of synapse can serve as an instructive signal for associative plasticity at a second class of synapse (Blair et al., 2001; Dudman et al., 2007). Of particular interest are inputs to the central nucleus of the amygdala from the parabrachial nucleus, which have recently been shown to be modulated by α2-receptor activation (Delaney et al., 2007). This input may provide an instructive signal for fear conditioning (Wilensky et al., 2006; Zimmerman et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that α2-receptor activation may regulate associative plasticity in the amygdala through a mechanism similar to that described here for the cerebellum. Thus, targeted regulation of instructive signals by noradrenaline and other modulators could provide a general mechanism for dynamic regulation of associative plasticity.

Experimental procedures

All animal procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals. Parasagittal cerebellar slices, 250 μm thick, were cut from the vermis of 13–19 day-old Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (Brenowitz and Regehr, 2003; Brenowitz and Regehr, 2005). The extracellular ACSF contained: 125 mM NaCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and was bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. For measurements of CF mEPSCs, CaCl2 was replaced with 2.5 mM SrCl2 and MgCl2 was increased to 4 mM to prevent CF hyperexcitability.

Drugs were bath applied. NBQX, picrotoxin, UK14304, yohimbine, DHPG, AM251, CGP55845A, DPCPX, MCPG, phenylephrine, and isoproterenol were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Fura-2 and fura-FF were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical significance was assessed with unpaired Student’s T-tests except where noted. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Electrophysiology

Voltage clamp

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed in PCs at room temperature using a Multiclamp 700B (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) and glass electrodes (1–2 MΩ) filled with an internal solution consisting of: 35 mM CsF, 100 mM CsCl, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES. Bicuculline (20 μM) was added to the ACSF to block inhibitory currents. NBQX (250–350 nM) was included in the external solution to reduce the amplitude of the CF-EPSC and minimize voltage-clamp errors. For experiments testing the effects of GTPγS in blocking the suppression of CF synapses by DHPG, the internal solution consisted of 145 mM CsMeSO4, 15 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM TEA-Cl, 2 mM Mg-ATP, 10 mM Phosphocreatine (tris), 2 mM QX-314, and either 0.4 mM Na-GTP or 1 mM GTPγS.

Current clamp

Recordings were performed at 34°C in ACSF containing picrotoxin (20 μM) to block inhibitory currents. CGP55845A (2 μM) was added to the ACSF for experiments in which high frequency stimulus trains were presented. Glass electrodes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution containing: 120 mM KMeSO3, 5 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Na2ATP, 0.4 mM NaGTP, 14 mM tris-creatine phosphate (pH 7.3). For calcium imaging experiments using Fura-2, EGTA was omitted. In some experiments GTP was replaced with GTPγS (1 mM). Small hyperpolarizing currents were injected to prevent spontaneous spiking and maintain the resting membrane potential at a constant level throughout each experiment. Hyperpolarization was reduced during conditioning trains to permit robust spiking in response to PF stimulation. 13 of the 25 total LTD experiments were performed with the experimenter blind to the drug treatment.

Calcium imaging

Imaging was carried out as previously described (Brenowitz and Regehr, 2003; Brenowitz and Regehr, 2005). The ratiometric calcium indicators Fura-2 (200 μM, Fig. 1) or Fura-FF (500 μM, Fig. 5) were added to the intracellular solution to measure postsynaptic calcium transients. Images were acquired at 50 Hz with 383 nm excitation, beginning 150–250 ms prior to the onset of CF stimuli or conditioning trains. Images with excitation at the isosbestic point of Fura-2 (360 nm) or Fura-FF (357 nm) were taken immediately before and after 383 nm excitation. Fluorescence ratios were converted to calcium concentrations using a value for the KD of 131 nM for Fura-2 (Brenowitz and Regehr, 2003; Grynkiewicz et al., 1985) and 3.5 μM for Fura-FF (Brenowitz et al., 2006).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephan Brenowitz, Kelly Foster, and Patrick Safo for help with early stages of this study, Kimberly McDaniels for technical assistance, and Misha Beierlein, John Crowley, Aaron Best, Claudio Acuña-Goycolea, Diasynou Fioravante, Michael Myoga, Andreas Liu, Miklos Antal, and Todd Pressler for comments on the manuscript. Supported by NIH Grants R37NS032405 and R01DA024090 (W.G.R.), a Helen Hay Whitney postdoctoral fellowship (M.R.C.), and a Harvard University Research Enabling Grant (M.R.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott LF, Nelson SB. Synaptic plasticity: taming the beast. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(Suppl):1178–1183. doi: 10.1038/81453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitai Y. Thalamocortical synaptic connections: efficacy, modulation, inhibition and plasticity. Rev Neurosci. 2001;12:159–173. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2001.12.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Fioravante D, Regehr WG. Differential expression of posttetanic potentiation and retrograde signaling mediate target-dependent short-term synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolino M, Vicini S, Gillis R, Travagli A. Presynaptic alpha2-adrenoceptors inhibit excitatory synaptic transmission in rat brain stem. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G654–661. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.3.G654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best AR, Regehr WG. Serotonin evokes endocannabinoid release and retrogradely suppresses excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6508–6515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0678-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G, Poo M. Synaptic modification by correlated activity: Hebb’s postulate revisited. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:139–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair HT, Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala: a cellular hypothesis of fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2001;8:229–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom FE, Hoffer BJ, Siggins GR. Studies on norepinephrine-containing afferents to Purkinje cells of art cerebellum. I. Localization of the fibers and their synapses. Brain Res. 1971;25:501–521. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Calcium dependence of retrograde inhibition by endocannabinoids at synapses onto Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6373–6384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06373.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Associative short-term synaptic plasticity mediated by endocannabinoids. Neuron. 2005;45:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Safo PK, Regehr WG. Endocannabinoids inhibit transmission at granule cell to Purkinje cell synapses by modulating three types of presynaptic calcium channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5623–5631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0918-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartford MC, Gould T, Bickford PC. A central role for norepinephrine in the modulation of cerebellar learning tasks. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2004;3:131–138. doi: 10.1177/1534582304270783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso A, Di Giannuario A, Loizzo A, Pieretti S, Sorrentino L. Dexamethasone modifies the behavioral effects induced by clonidine in mice. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:1429–34. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:37–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coesmans M, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron. 2004;44:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney AJ, Crane JW, Sah P. Noradrenaline modulates transmission at a central synapse by a presynaptic mechanism. Neuron. 2007;56:880–892. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Uzbay IT. Topical clonidine antinociception. Pain. 2004;111:385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudman JT, Tsay D, Siegelbaum SA. A role for synaptic inputs at distal dendrites: instructive signals for hippocampal long-term plasticity. Neuron. 2007;56:866–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid I, Sjostrom PJ. Novel presynaptic mechanisms for coincidence detection in synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Llinas R, Sasaki K. The excitatory synaptic action of climbing fibres on the purinje cells of the cerebellum. J Physiol. 1966a;182:268–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Llinas R, Sasaki K. Parallel fibre stimulation and the responses induced thereby in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Exp Brain Res. 1966b;1:17–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00235207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KA, Regehr WG. Variance-mean analysis in the presence of a rapid antagonist indicates vesicle depletion underlies depression at the climbing fiber synapse. Neuron. 2004;43:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti N, Bartolini A, Ghelardini C. Alpha-2 agonist-induced memory impairment is mediated by the alpha-2A-adrenoceptor subtype. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. How the cerebellum could memorise movements. Nature. 1975;254:688–689. doi: 10.1038/254688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PF. Simple spike frequency and the number of secondary spikes in the complex spike of the cerebellar Purkinje cell. Brain Res. 1976;114:334–338. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PF, Thach WT. Purkinje cell activity during motor learning. Brain Res. 1977;128:309–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giocomo LM, Hasselmo ME. Neuromodulation by glutamate and acetylcholine can change circuit dynamics by regulating the relative influence of afferent input and excitatory feedback. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:184–200. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Slater NT, Rossi DJ, Miller RJ. Role of metabotropic glutamate (ACPD) receptors at the parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:1453–1462. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel C, Linden DJ. Long-term depression of the cerebellar climbing fiber--Purkinje neuron synapse. Neuron. 2000;26:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Kano M. Presynaptic origin of paired-pulse depression at climbing fibre-Purkinje cell synapses in the rat cerebellum. J Physiol. 1998;506:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.391bw.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. The Organization of Behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Hein L. Adrenoceptors and signal transduction in neurons. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:541–551. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer BJ, Siggins GR, Bloom FE. Studies on norepinephrine-containing afferents to Purkinje cells of rat cerebellum. II. Sensitivity of Purkinje cells to norepinephrine and related substances administered by microiontophoresis. Brain Res. 1971;25:523–534. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokfelt T, Fuxe K. Cerebellar monoamine nerve terminals, a new type of afferent fibers to the cortex cerebelli. Exp Brain Res. 1969;9:63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00235452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Cerebellar long-term depression: characterization, signal transduction, and functional roles. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1143–1195. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. Thalamic organization and function after Cajal. Prog Brain Res. 2002;136:333–357. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller EL, Smith MJ. Suppressed visual adaptation of the vestibuloocular reflex in catecholamine-depleted cats. Brain Res. 1983;258:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Isokawa M, Ledent C, Alger BE. Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors enhances the release of endogenous cannabinoids in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10182–10191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10182.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto Y, Satoh K, Sakumoto T, Tohyama M, Shimizu N. Afferent fiber connections from the lower brain stem to the rat cerebellum by the horseradish peroxidase method combined with MAO staining, with special reference to noradrenergic neurons. J Hirnforsch. 1978;19:85–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa S, Kimura T, Yin PB. Cerebellar complex spikes encode both destinations and errors in arm movements. Nature. 1998;392:494–497. doi: 10.1038/33141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2001;29:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik A, Haentzsch A, Luckermann M, Reichelt W, Ballanyi K. Neuron-glia signaling via alpha(1) adrenoceptor-mediated Ca(2+) release in Bergmann glial cells in situ. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8401–8408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis SC, Bloom FE. Ultrastructural identification of noradrenergic boutons in mutant and normal mouse cerebellar cortex. Brain Res. 1975;96:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer SZ. Sixth gaddum memorial lecture, National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, January 1977. Presynaptic receptors and their role in the regulation of transmitter release. Br J Pharmacol. 1977;60:481–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb07526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RM, Von Gersdorff H. Noradrenaline increases high-frequency firing at the calyx of held synapse during development by inhibiting glutamate release. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2297–2306. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima T, Hashimoto K, Yoshida T, Aiba A, Kano M. Presynaptic inhibition caused by retrograde signal from metabotropic glutamate to cannabinoid receptors. Neuron. 2001;31:463–475. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Thompson RF. Locus coeruleus lesions and resistance to extinction of a classically conditioned response: involvement of the neocortex and hippocampus. Brain Res. 1982;245:239–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoma H, Konishi S. Monoaminergic long-term facilitation of GABA-mediated inhibitory transmission at cerebellar synapses. Neuroscience. 1999;88:871–883. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrin LC, Gerety ME, Happe HK, Bylund DB. Inverse agonism at alpha(2)-adrenoceptors in native tissue. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas AP, Hokfelt T, Pieribone VA. The distribution and significance of CNS adrenoceptors examined with in situ hybridization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA. Expression mechanisms underlying long-term potentiation: a postsynaptic view. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:721–726. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SH, Baimoukhametova DV, Piet R, Bains JS. Retrograde regulation of GABA transmission by the tonic release of oxytocin and endocannabinoids governs postsynaptic firing. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1325–1333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2676-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L, Fuxe K. On the projections from the locus coeruleus noradrealine neurons: the cerebellar innervation. Brain Res. 1971;28:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis TS, Kavanaugh MP, Jahr CE. Postsynaptic glutamate transport at the climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapse. Science. 1997;277:1515–8. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Ross WN. Weak effect of neuromodulators on climbing fiber-activated [Ca(2+)](i) increases in rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Brain Res. 1999;831:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano O. Noradrenergic influences on the cerebellar cortex: effects on vestibular reflexes under basic and adaptive conditions. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:93–105. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancz EA, Hausser M. Dendritic calcium spikes are tunable triggers of cannabinoid release and short-term synaptic plasticity in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5428–5437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5284-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JL, Lisberger SG. Neural learning rules for the vestibulo-ocular reflex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9112–9129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safo PK, Regehr WG. Endocannabinoids control the induction of cerebellar LTD. Neuron. 2005;48:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinin M, Lomasney JW, Hayden-Hixson DM, Schambra UB, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Fremeau RT., Jr Distribution of alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtype gene expression in rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;21:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmolesky MT, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. The making of a complex spike: ionic composition and plasticity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;978:359–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb07581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter S, Apparsundaram S, Wiley RG, Miner LH, Sesack SR, Blakely RD. Immunolocalization of the cocaine- and antidepressant-sensitive l-norepinephrine transporter. J Comp Neurol. 2000;420:211–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweighofer N, Doya K, Kuroda S. Cerebellar aminergic neuromodulation: towards a functional understanding. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;44:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol GH, Ziburkus J, Huang S, Song L, Kim IT, Takamiya K, Huganir RL, Lee HK, Kirkwood A. Neuromodulators control the polarity of spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;55:919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggins GR, Hoffer BJ, Bloom FE. Studies on norepinephrine-containing afferents to Purkinje cells of rat cerebellum. 3. Evidence for mediation of norepinephrine effects by cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate. Brain Res. 1971a;25:535–553. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggins GR, Hoffer BJ, Oliver AP, Bloom FE. Activation of a central noradrenergic projection to cerebellum. Nature. 1971b;233:481–483. doi: 10.1038/233481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillito AM, Cudeiro J, Jones HE. Always returning: feedback and sensory processing in visual cortex and thalamus. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazielle C, Lalonde R, Hebert C, Reader TA. Regional brain distribution of noradrenaline uptake sites, and of alpha1-alpha2- and beta-adrenergic receptors in PCD mutant mice: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1999;94:287–304. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi KA, Linden DJ. Cannabinoid receptor modulation of synapses received by cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1167–1180. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Kovalchuk Y, Attwell D. Pre- and postsynaptic determinants of EPSC waveform at cerebellar climbing fiber and parallel fiber to Purkinje cell synapses. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05693.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares A, Handy DE, Bogdanova NN, Rosene DL, Gavras H. Localization of alpha 2A- and alpha 2B-adrenergic receptor subtypes in brain. Hypertension. 1996;27:449–455. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma N, Carlson GC, Ledent C, Alger BE. Metabotropic glutamate receptors drive the endocannabinoid system in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt KE, Regehr WG. Cholinergic modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA3 area of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:75–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00075.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadiche JI, Jahr CE. Multivesicular release at climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron. 2001;32:301–313. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Macmillan LB, Fremeau RT, Jr, Magnuson MA, Lindner J, Limbird LE. Expression of alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes in the mouse brain: evaluation of spatial and temporal information imparted by 3 kb of 5′ regulatory sequence for the alpha 2A AR-receptor gene in transgenic animals. Neuroscience. 1996;74:199–218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M, McElligott JG. Cerebellar norepinephrine depletion and impaired acquisition of specific locomotor tasks in rats. Brain Res. 1984;296:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Linden DJ, Hansel C. Long-term depression of climbing fiber-evoked calcium transients in Purkinje cell dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2878–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536420100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky AE, Schafe GE, Kristensen MP, LeDoux JE. Rethinking the fear circuit: the central nucleus of the amygdala is required for the acquisition, consolidation, and expression of Pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12387–12396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4316-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Presynaptic strontium dynamics and synaptic transmission. Biophys J. 1999;76:2029–42. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77360-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Probing fundamental aspects of synaptic transmission with strontium. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4414–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04414.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HH, Woodward DJ. Beta-1 adrenergic receptors mediate noradrenergic facilitation of Purkinje cell responses to gamma-aminobutyric acid in cerebellum of rat. Neuropharmacology. 1983;22:629–639. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(83)90155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Comparison of two forms of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal neurons. Science. 1990;248:1619–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YD, Turner TJ, Dunlap K. Enhanced G protein-dependent modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the cerebellum of the Ca2+ channel-mutant mouse, tottering. J Physiol. 2003;547:497–507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman JM, Rabinak CA, McLachlan IG, Maren S. The central nucleus of the amygdala is essential for acquiring and expressing conditional fear after overtraining. Learn Mem. 2007;14:634–644. doi: 10.1101/lm.607207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.