1. Introduction

There is abundant evidence of the crisis of HIV in the Black American community. Recent data show that African Americans comprise 46% of persons living with HIV, and that black men have rates six times higher than their white counterparts, while black women have rates 18 times higher than white women [1].

These data are accompanied by urgent calls for inclusion of Black men in HIV prevention research [2,3]. African Americans are under-represented in research in general and on HIV prevention in particular [4]. When African Americans have been included in prevention research, they have been primarily women [4–6] and a very small number of interventions have targeted Black men [7–10]. The calls for increased inclusion of Black men in HIV prevention research are made simultaneously to calls for increased research participation for persons who are both underrepresented in research but overrepresented among persons with negative health outcomes [1].

Attention to limited enrollment by minorities in research has resulted in numerous publications on the barriers to diversifying recruitment and strategies employed to overcome those barriers. The barriers cited related to recruitment include (1) a lack of trust among minority communities towards the research process and researchers [11,12]; (2) a lack of competence among researchers to use culturally competent approaches for recruitment [13,14]; and (3) reluctance to participate in trials due to inconvenience and a lack of time [13,15,16].

Strategies that have been employed to overcome some of these limitations include development of trust within communities, including working with and being visible in communities before you go to their representatives asking for their participation in research [12]. Ideally, if recruiters for research studies are from the population they wish to recruit they will then bring their own knowledge of the community to bear in engaging with members to invite their participation in research [12,13]. Research should be carried out in community settings when possible, and at times of the day and days of the week that are convenient to the study population rather than the researcher [11,12,14,17].

In this paper, we describe the methods used to recruit and retain 60 young black men in Philadelphia for a pilot study of an HIV prevention intervention called The 411 for Safe Text, (hereafter called The 411). The 411 intervention utilizes text messages sent via short message service (SMS) over cell phones. Cell phone modality was chosen over other options such as Internet or Computer Kiosk based on ample evidence of the popularity of the medium for young black men [18,19], as well as evidence that Internet access and use among young black men continues to lag behind use of Internet among other racial/ethnic groups [20,21]. The 411 is a partnership between the Colorado School of Public Health (CSPH) and Motivational Educational Entertainment (MEE) Productions in Philadelphia, PA. Researchers at CSPH have expertise in the development and evaluation of technology based approaches for health promotion, and have developed and evaluated multiple interventions that are technology based [22–26]. MEE Productions “is a cutting edge communications research and marketing firm that specializes in developing cost effective and culturally relevant messages for hard-to-reach urban and ethnic audiences” [27]. Through the media production services they offer, MEE has regular opportunities to communicate with organizations serving black youth, and over many years, has developed strong relationships with a network of hundreds of CBO’s nationwide. CSPH and MEE formed their partnership based on shared interests to address the HIV epidemic among black men and spent the next two years seeking funding for their idea. During this process, they had ample opportunity to get to know one another and develop trust.

The 411 recruitment, enrollment and retention methods presented here are informed by several core principles of community based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR has been defined as:

A collaborative process that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community with the aim of combining knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate health disparities [28].

Here we will present more detail on our research design, as well as our pilot study recruitment, enrollment, and retention methods. We will describe successes and limitations related to our efforts and consider lessons learned to improve recruitment and retention of young black men in HIV prevention research.

2. Methods

The 411 was a non-randomized two group pilot study of the feasibility and efficacy of using text messages to promote HIV prevention behaviors among 60 young black men in Philadelphia. We tapped into MEE Production’s network of CBOs in Philadelphia serving young black men, and recruited participants from these CBOs. At the outset, half of the organizations were identified as control recruitment sites and half as intervention sites. This was done to minimize likelihood of contamination among participants enrolled in the pilot study within any one organization. As this was a pilot study, we did not randomize sites to intervention or control status; our primary goals were to test the feasibility of enrollment, participation and retention at three and six months of young black men in a text messaging program for HIV prevention.

Men completed a baseline risk assessment administered by CSPH staff, and then MEE Productions sent them text messages three times each week for twelve weeks about nutrition (controls) or sexual health (intervention). Details on development of text messages are available elsewhere [26]. They were invited by CSPH staff to complete a follow-up risk assessment at three months. After their first follow-up, they received no additional text messages; a second follow-up assessment was conducted by CSPH staff at six months. All study evaluation activities were conducted by CSPH staff and all intervention activities by MEE staff, as we endeavored to keep research and evaluation activities strictly separate.

The key CBPR principles guiding the work in recruitment and retention for research described here include: (a) A reliance on a community-academic partnership in all phases of the research process; (b) The recognition of the community as the unit of identity; and (c) A reliance on community strengths and resources for recruitment and retention [28–30].

2.1 Recruitment

We considered recruitment to be the process of identifying and screening potential participants for eligibility. We relied on MEE Production’s extensive network of CBOs to begin recruitment. MEE identified organizations within this network serving young black men aged 16–20. MEE then targeted 22 organizations from their network of over 100 in Philadelphia for recruitment who served the highest proportion of youth. MEE invited representatives from these CBOs to learn about the community-academic partnership between MEE and CSPH and determine if they were interested in offering study recruiters access to their clientele. Each organization staff and leadership had to first give permission before we could recruit for the study from these settings. In total, 18 of the initial 22 CBOs targeted for recruitment agreed to be recruitment sites (82%). Recruitment sites included high schools, charter schools, and community colleges and CBOs focused on political involvement, addressing drug and alcohol abuse and gang-related issues, advocacy for GLBT youth, and services for educational and employment achievement.

Recruiters were two female MEE staff experienced in recruitment and trained in the study protocol. We used female staff for recruitment based on feedback received when pilot testing study instruments. Young men told us they would respond more positively when approached by women. Our recruiters approached men in CBOs to screen them for eligibility. Recruitment occurred at varying hours of the day and week, including during afternoons, evenings and weekends. Eligibility criteria included age (between 16 and 20), male gender, self-identified African American / Black race, having a cell phone, sexually active, and plans to live in Philadelphia for the subsequent 6 months. Because cell phones are very common, and because we were interested in feasibility, we restricted eligibility to persons who already had a phone. Recruiters documented name and contact information (i.e. two telephone numbers where possible, a cell phone and land line) for those eligible in recruitment logs and informed participants that they would receive a phone call from study staff in Colorado within a week to complete enrollment and answer survey questions over the phone. Our target enrollment was 60 men. We based our sample size on numbers needed to show feasibility of recruitment and retention and to show any changes in HIV risk behaviors over time. Sampling procedures are described in detail elsewhere [31]. Recruiters identified more than needed anticipating fewer would be reachable or willing to complete the baseline risk assessment. Initial recruitment took place over 4 weeks.

2.2 Enrollment and data collection

In an effort to stringently separate research and evaluation activities from intervention activities, enrollment and evaluation related data collection was conducted by CSPH staff. The enrollment process included communication with all persons identified as eligible to complete informed consent and a baseline risk assessment.

Recruitment logs were sent to two female staff in Colorado; as with our recruiters, female staff were used in response to suggestions by young men during pilot tests of our study instrument. Men told us they could be more forthcoming and less likely to embellish sexual experience if they were talking to women who were older than themselves.

Enrollment staff (1) obtained informed consent from participants and (2) administered a baseline survey over the telephone. Potential participants were contacted up to 3 times; if they had not been reached or did not respond, or they did not wish to participate after the study had been explained in further detail, they were not enrolled. At three and six month follow up data collection points, each young man enrolled was contacted by the same enrollment staff to complete follow-up surveys over the phone. Participants were paid $40 when completing each survey. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #07-0463).

During recruitment and enrollment, MEE and Colorado study staff maintained daily contact to discuss recruitment and enrollment strategies, successes and barriers. They made modifications to recruitment and enrollment based on these conversations that will be discussed in the results section.

3. Results

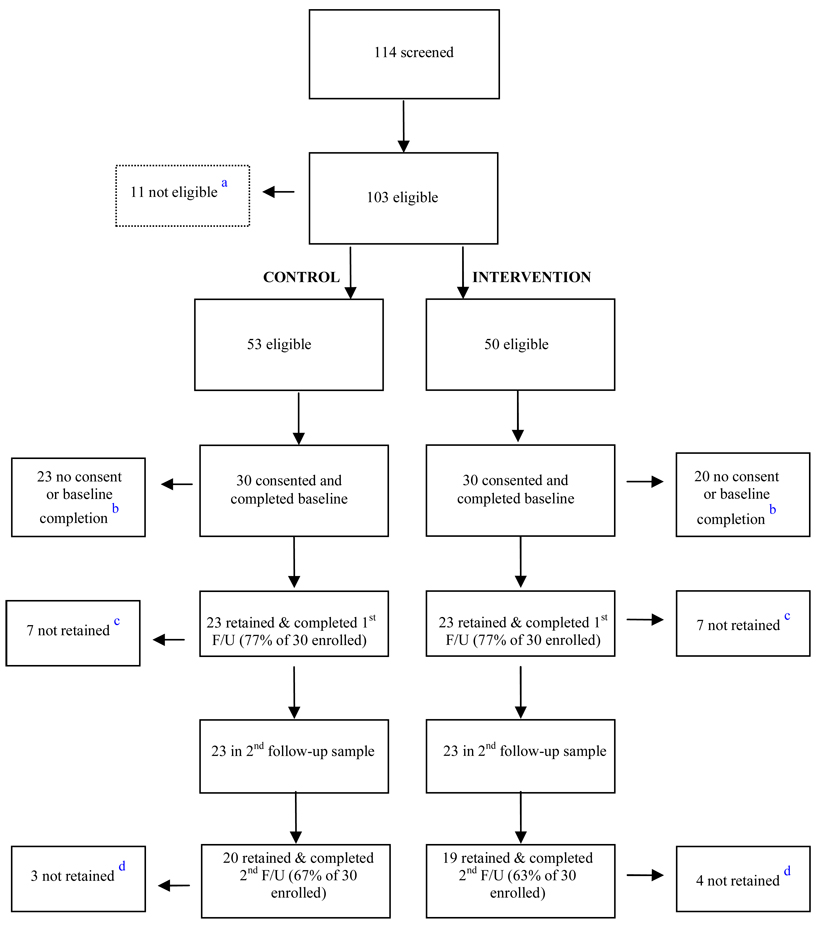

Recruitment, enrollment and retention data are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Recruitment, Enrollment, and Retention.

a 11 not eligible because they had never had sex

bTotal of 43 did not consent (multiple attempts to contact or refusal to participate after project was explained in more detail)

c Total of 14 not retained to complete follow-up (dropped from study (N=2) OR multiple attempts to contact or refusal to continue participation (N=12))

dTotal of 7 not retained to complete 2nd follow-up because of multiple attempts to contact or refusal to continue participation

3.1 Recruitment

Recruiters approached a total of 114 men in these settings who appeared to be eligible for the study. Recruiters identified 103 of these 114 men (87%) as eligible and interested in participating. Approximately half were designated as control participants (N=53) and the remainder as intervention participants (N=50).

3.2 Enrollment

A total of 60 young men (30 control, 30 intervention) were successfully contacted and expressed continued interest in being enrolled (58% of the 103 recruited). The remaining 43 men were either not eligible (n=11), not contacted after three attempts (n=22), declined participation after learning more about it through the informed consent process (n=2), or were not contacted because our target of 60 men had been enrolled (n=8). We observed no differences in terms of age with regard to those who enrolled and completed a baseline survey compared to those not enrolled. Because eligibility criteria did not include income level or education, we do not have these data on those refusing enrollment, and cannot assess differences on these variables.

Enrollment staff in Colorado initially found it challenging to connect with potential participants recruited by MEE staff. They considered that men were potentially unfamiliar with who they were, even though recruitment staff alerted potential participants to the fact that they would receive calls from Colorado to complete their study assessments. They also considered that having time elapse between recruitment and enrollment was detrimental.

At all subsequent recruiting events, staff emphasized to men that their calls would come from a 303 area code. They also told men the names of the enrollment staff that they would hear from so they could expect a call from a specific person in Colorado. Finally, they also emphasized to men that their cash incentive would be available at MEE as soon as they completed the baseline survey.

One of the enrollment staff in Colorado was a woman in her mid-40’s; the other in her mid-20’s. The older enrollment staff worked to enroll men aged 19 and above; the younger worked to enroll those aged 16–18. Each staff maintained contact with the same participants at the three and six month follow-ups in order to facilitate continuity [14].

3.3 Retention

We retained 77% of the young men for a follow-up survey at three months; equal numbers of men from the control and intervention conditions completed the three month follow-up. We retained 65% of the 60 initial enrollees (N=39) for the six-month follow-up survey. We observed no differences with regard to age, education level or income among those continuing the study compared to those lost to follow-up.

4. Discussion

This paper reports on the feasibility of recruiting, enrolling and retaining young black men in a technology-based HIV prevention initiative. We had an initial enrollment of 58%; this may be perceived as low, but recall that once we enrolled our target sample of 60 for this pilot study, we stopped enrolling. We documented a 77% retention rate at three months and a 65% retention rate at six months, which are consistent with recruitment of diverse samples in other community based HIV prevention research [32,33]

According to CDC, African American youth account for 55% of all HIV infections ever reported among those aged 13–24 [34]. HIV has been with us for over two decades, and HIV infections disproportionately impact young African Americans. Efforts for HIV prevention focusing on the African American community, though spotty and inconsistent, tend to target either African American females or African American men who have sex with men (MSM). The failure to actively include young African American males who are heterosexual and/or don’t identify as gay in prevention efforts is a gaping omission.

U.S. federal agencies funding health related research have mandated that researchers increase enrollment of women, minorities and children in research; they have further indicated that citing additional costs with diversifying study enrollment as an excuse for failure to meet the mandate will not be acceptable [35]. Yet, we still face challenges in recruitment of racially and ethnically diverse participants for research—perhaps particularly in recruitment of young black men. African American youth, especially low income, are not accessible using traditional recruitment methods. They live in communities that many are reluctant to enter. They do not participate in the same activities and cannot be accessed as mainstream youth. African American youth do not have the opportunity to participate in the same level of organized sports or traditional organizations like the boy scouts. They are more often connected to community-based organizations that work hard to keep them off the streets or out of the juvenile justice system. These types of programs may provide tutoring, after school programs, rite of passage, etc.

We were able to overcome some of these challenges through our adherence to three key principles of CBPR: a) A reliance on a community-academic partnership in all phases of the research process; (b) The recognition of the community as the unit of identity; and (c) A reliance on community strengths and resources for recruitment and retention [28–30]. Having a reliance on our community-academic partnership in all phases of the research project meant that MEE could identify willing partners from the outset of the project; we didn’t need to obtain funding and then use limited resources—including time—to cultivate the trusting relationships with CBOs that were invaluable. MEE maintains and cultivates relationships with CBOs in their network [36]. For example, MEE conducts “chat and chews”, where they invite community members within their organizational network to come to a lunch or dinner and hear a brief presentation about what MEE has been working on, and produces “Urban Trends,” a newsletter distributed quarterly to all members within their network. These are just two of many ways that MEE stays in touch with the black community and facilitates open and trusting relationships that can be accessed for research recruitment.

Because of these efforts, CBOs were willing to serve as gatekeepers to our participants. Tapping this community network, the study team was able to quickly identify and recruit young men to participate in the research project. Most importantly, we were able to leverage the goodwill from these organizations. They trust MEE, and were willing to endorse their work.

We identified CBOs as a unit of identity; we recognized that men within CBOs could potentially communicate with each other and contaminate one another if they were assigned to intervention or control status at the individual level. Furthermore, men we recruited trusted these organizations and were thus willing to engage with us. It seems critical to leverage trust given the well documented lack of trust in research grounded in the infamous Tuskegee study [37] and experiences of shame and disrespect when seeking health—and more specifically—STD and HIV related care [38–40]. Building trust is explicitly named as a primary strategy for improvement of recruitment of African Americans into research trials generally. [36,41,42]

CSPH relied on the particular strengths of MEE throughout the process by regularly communicating with them about strategies for improving enrollment and retention; MEE was able to bring their institutional knowledge to bear in advising CSPH on overcoming enrollment and retention barriers.

Not to be underestimated in our recruitment, enrollment and retention success were the excellent, trained, female recruitment and enrollment staff who interacted with the participants through the study. They treated the participants with respect, answered their questions and maintained communication with them to facilitate trust [36]. We listened to young black men who told us that they would be more responsive and forthcoming to women. Our staff did not indicate having negative experiences or challenges in recruiting participants of the opposite gender, and although being of different racial or ethnic background has been cited as a power differential and subsequent recruitment barrier in other research [42], we know of no studies citing gender differences between recruiters and participants as a barrier. Making sure the same enrollment staff completed the baseline, three and six month interview allowed for continuity and improved study recognition at follow-up.

Although we are pleased with the success in recruitment, enrollment and retention of young black men in an HIV prevention initiative demonstrated here, we do acknowledge limitations with this work. We recruited a very small sample—60 men. We didn’t randomize CBOs, so there are likely biases we didn’t control for within groups. Therefore, we cannot assume that the recruitment and retention efforts observed here would be generalizable to other studies. We were not able to retain 14 for the three month follow-up and seven for the six month follow up. We believe these losses were due in part to a geographic disconnect between study partners. In an effort to retain rigorous boundaries between intervention delivery and evaluation, we kept assessments separate. However, this may have introduced a barrier for men who had made face-to-face connections with recruiters but never met the women with whom they completed assessments.

A future, more rigorous trial will determine if these strategies for recruitment and retention can be successful when working with much larger samples and when adhering to a more complex study protocol.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R21MH083318 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence estimates-United States 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2008;51:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spikes P, Purcell D, Williams K, Chen Y, Ding H, Sullivan P. Sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive Black men who have sex with women, with men, or with men and women: implications for intervention development. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1072–1078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson J, Jones K. HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:976–980. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dancy BL, Marcantonio R, Norr K. The long-term effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention for low-income African American women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mize SJ, Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Scheltema KE. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions for women. AIDS Care. 2002;14:163–180. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diclemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among black male adolescents: effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Lack of positive outcomes from a cognitive-behavioral HIV and AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city men: lessons from a controlled pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9:299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Browne-Sperling F. Effectiveness of a video-based motivational skills-building HIV risk-reduction intervention for inner-city African American men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:959–966. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiLorio C, Resnicow K, McCarty F, De AK, Dudley WN, Wang DT, et al. Keepin' It R.E.A.L! Results of a mother-adolescent HIV prevention program. Nurs Res. 2006;55:43–51. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wrobel AJ, Shapiro NE. Conducting research with urban elders: Issues of recruitment, data collection, and home visits. lzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier MA, Clarke WP. Gaining and sustaining minority participation in longitudinal research projects. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:29–33. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199904001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown BA, Long HL, Gould H, Weitz T, Milliken N. A conceptual model for the recruitment of diverse women into research studies. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:625–632. doi: 10.1089/15246090050118152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams SW. Recruitment and retention strategies for longitudinal African American caregiving research: the family caregiving project. J Aging Health. 2004;16:137–156. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DR, Fonad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoenfeld ER, Greene JM, Wu SY, O'Leary E, Forte F, Leske MC. Recruiting participants for community-based research: The Diabetic Retinopathy Awareness Program. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:432–440. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaro H, de la Torre A. Public health needs and scientific opportunities in research on Latinas. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:525–529. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris Interactive. Cell phone usage continues to increase. Harris Interactive, Inc. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.African-Americans and Hispanics dominate cellphone use. 2007 cellular news.com. http://www.cellular-news.com.

- 20.Jackson LA, Zhao Y, Kolenic A, Fitzgerald HE, Harold R, Von Eye A. Race, gender, and information technology use: the new digital divide. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:437–442. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorence DP, Park H, Fox S. Racial disparities in health information access: resilience of the digital divide. J Med Systems. 2006;30:241–249. doi: 10.1007/s10916-005-9003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bull S, McFarlane M, Phibbs S, Watson S. What do young adults expect when they go online? Lessons for development of an STD/HIV and pregnancy prevention website. J Med Systems. 2007;31:149–158. doi: 10.1007/s10916-006-9050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myint-U A, Bull S, Greenwood G, Patterson J, Rietmeijer C, Vrungos S, et al. Safe in the city: developing an effective video-based intervention for STD clinic waiting rooms. Health Promot Pract. 2008 Jun 10; doi: 10.1177/1524839908318830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bull S, Pratte K, Whitesell N, Reitemeijer C, McFarlane M. Effects of an internet-based intervention for HIV prevention: the Youthnet trials. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:474–487. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leeman-Castillo B, Guitierrez-Raghunath S, Beaty B, Steiner JF, Bull S. LUCHAR: battling heart disease with computer technology for Latinos. Am J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162115. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright E, Juzang I, Fortune T, Bull S. Development of a text messaging (SMS) program for HIV prevention: the 411 on safe text. AIDS Care. 2009 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.524190. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MEE Productions Inc. 2009 http://www.meeproductions.com/

- 28.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82:3–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;3:1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; p. 005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juzang I, Fortune T, Black S, Wright E, Bull S. The 411 for safe text: results from a promising pilot program using cell phones for HIV prevention. J Telemed Telecare. 2009 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgs DL, Maciak B, Metzler M. CCommunity-based participatory reseach to improve the health of urban communities. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:9–15. doi: 10.1089/152460901750067070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of HIV prevention interventions with evidence of effectiveness. US Department of Health and Human Services. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Prevention in the third decade. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caban CE. Hispanic research: implications of the National Institutes of Health guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995;18:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adderley-Kelly B, Green PM. Strategies for successful conduct of research with low-income African American populations. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:563–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fortenberry JD, McFarlane M, Bleakley A, Bull S, Fishbein M, Grimley DM, et al. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and HIV screening. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:378–381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster PH. Use of stigma, fear, and denial in development of a framework for prevention of HIV/AIDS in rural African American communities. Fam Community Health. 2007;30:318–327. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000290544.48576.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galvan FH, Davis EM, Banks D, Bing EG. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:423–436. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams IC, Corbie-Smith G. Investigator beliefs and reported success in recruiting minority participants. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dancy BL, Wilbur J, Talashek M, Bonner G, Barnes-Boyd C. Community-based research: barriers to recruitment of African Americans. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]