Abstract

Translational, transdisciplinary, and transformational research stands to become a paradigm-shifting mantra for research in health disparities. A windfall of research discoveries using these 3 approaches has increased our understanding of the health disparities in racial, ethnic, and low socioeconomic status groups. These distinct but related research spheres possess unique environments, which, when integrated, can lead to innovation in health disparities science.

In this article, we review these approaches and propose integrating them to advance health disparities research through a change in philosophical position and an increased emphasis on community engagement. We argue that a balanced combination of these research approaches is needed to inform evidence-based practice, social action, and effective policy change to improve health in disparity communities.

THE FIELD OF HEALTH DISPARities science has reached an important crossroad with the need for a paradigm shift. Progress in research to reduce the health disparities gap that exists for racial and ethnic minorities, rural, and low socioeconomic populations has been slow despite significant recent advances in science. But today, high throughput technologies for translational research and the application of genomic and molecular data to facilitate the discovery of new therapies is beginning to offer promise for disparity-reduction efforts.1 The field of medicine has entered a revolutionary period that offers the unprecedented opportunity to identify risk of disease, based on precise molecular knowledge, and the chance to preempt disease conditions. As a result of the accelerated science discoveries and technological revolution, the potential for eliminating disparities is proliferating.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting biomedical research to improve health and save lives. In 1999, the NIH identified the reduction of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health as a major priority for public health practice and research.2 The establishment in law of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) in 2000 has provided a source of ongoing critical support for health disparities research and assures continuous, effective coordination of health disparities research programs across the NIH.3 Public Law 106-525 gave the NCMHD grant funding authority and broadened its constituency base. Since then, the NIH has made profound changes in health disparities research, embracing approaches that are participatory and cross-disciplinary. Some aspects of these changes represent a deepening of the scientific knowledge process already in motion; other changes represent a growing shift in philosophical view of health disparities as a social justice issue with need for full social engagement. In the last 2 decades we have had an exponential increase in identifying broader determinants of health.4,5 The current landscape of health disparities science includes an understanding of the complex associations between biological and nonbiological determinants of health.6–8 Over the same time period, training and mentoring of new investigators to address health disparities has progressed, creating a larger, multidisciplinary workforce.9

In his classic book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn10 explains that paradigm shifts occur when scientists encounter anomalies that cannot be explained by the universally accepted paradigm in which progress has been made. The paradigm shift, in his view, is not simply the current theory, but full engagement of the world in which the theory exists and features of the landscape of knowledge that scientists can identify around them. When enough significant anomalies have accrued within a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of crisis, according to Kuhn, and the old ways of making sense of the world are no longer useful.

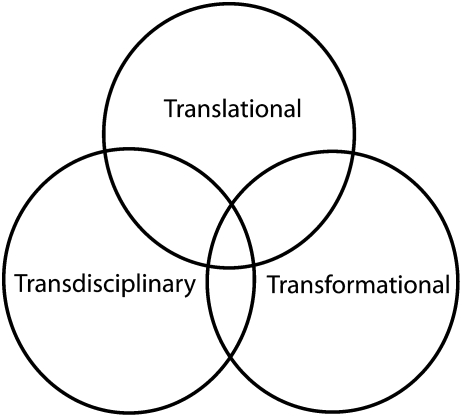

We provide a model for such a paradigm shift through the balance and integration of translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary thematic research. We also attempt to conceptualize these 3 approaches as a guide for advancing the science of health disparities research through a change in philosophical position and community engagement. Translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary thinking are currently important dimensions of “paradigm-shifting” research. We argue that a balanced combination of these research approaches is needed to inform evidence-based practice, social action, and effective policy change to affect change and close the health disparity gap. Figure 1 represents the triad of translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary health disparities research. These 3 spheres of research are often separate and disparate. Sometimes there is overlap where the 2 spheres are linked and working together. There is the rare occasion when all 3 spheres of research are aligned and intersect. We call for an integrated approach for positive transformation in disparities research.

FIGURE 1.

The intersections of translational, transformational and transdisciplinary research.

TRANSLATIONAL HEALTH DISPARITIES RESEARCH

The term translational research is traditionally defined at the NIH to mean translation of knowledge or science from the molecular or biological level to practical use, including clinical practice and applied technology. The phrase “from bench to bedside” encapsulates the idea behind translational research.

We define translational health disparities research as research that links or translates basic science (biological, genetic, social, political, and environmental) discoveries to practical, applicable strategies and effective policies to improve health outcomes in health disparity populations. Health disparities researchers have appropriately adopted the phrase “from bench to bedside to curbside” to include the important aspect of outreach and dissemination research. Translational health disparities research is bidirectional and cyclical, not linear; it occurs along a continuum from discovery to development to delivery and back to development and discovery and involves the following domains: (1) basic science discovery, (2) testing and applications in developmental stages, (3) outreach and dissemination of findings, and (4) adoption and implementation.

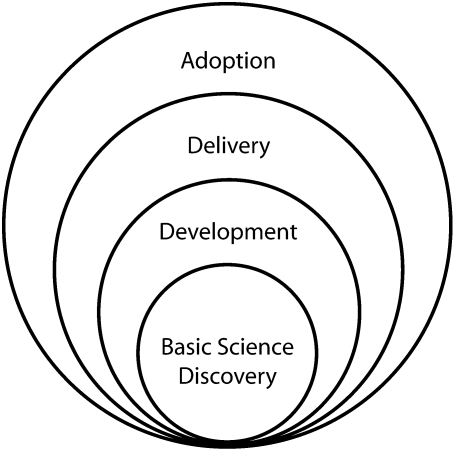

Figure 2 illustrates the bidirectional and cyclical dimensions of translational research. Discoveries in basic science include the identification of a promising molecule or gene target or the findings of new results in epidemiologic, environmental, or sociological studies. This discovery phase is followed by early and late translational phases of testing, clinical trials, and intervention development. When enough data and evidence have been generated, research results from the developmental phase are disseminated to clinical practice, public health programs, and community settings.11–13 The dissemination research period, also known as the delivery phase, is critical as it has the potential to inform policy and generate guidelines. It is also the phase to explore receptiveness or compliance to the new discovery or science. During the adoption phase, the research results are implemented and the new approach, idea, or technology is institutionalized. Prior to the adoption phase, dissemination of findings in the delivery phase may need to be assessed, evaluated, and retested to inform the discovery phase. Table 1 illustrates the bidirectional and cyclical stages of the translational continuum for health disparities research from discovery to development, delivery, and adoption.

FIGURE 2.

Translational continuum for health disparities research.

TABLE 1.

Stages of the Translational Continuum for Health Disparities Research from Discovery to Adoption

| Development |

DELIVERY ADOPTION |

|||

| Basic Science Discovery | Early Translation | Late Translation | Dissemination | Adoption/Implementation |

| Promising molecule or gene target | Intervention development | Establishing guidelines for application or practice | Community outreach Media outreach | Adoption and implementation of practices and policies |

| Basic epidemiologic study | Integrating biological and nonbiological factors | Phase III and IV trials | Health education and outreach trainings | Environmental changes/policy changes |

| Health trainings | ||||

| Basic ecological or socioecologic findings | Partnerships, networks, coalition-building, and collaborations to advance early translational research | Comparative effectiveness studies | Exploring receptiveness to interventions, population response, and compliance | Health status and lifestyle modification |

| Population studies and data analysis | Phase I and II trials—analyzing efficacy, acceptability, and safety | Technology transfer and development | Development of practice guidelines and evidence-based guidelines | Technology advances |

| Gene–environment interaction studies | Constructing frameworks, models, concepts or theories, and hypothesis | Development of policies (local, state, national) | Disparity-reduction measures; outcome measures | |

| Basic environmental research | Community-based participatory research approaches | |||

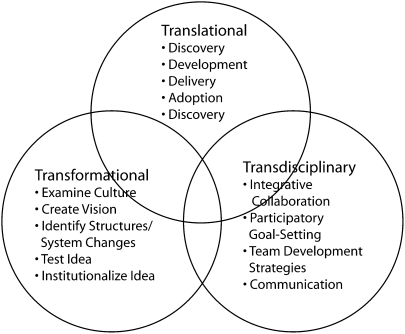

FIGURE 3.

Innovations in health disparities science at the intersections of translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary research.

An example of health disparities research applied across the translational research continuum is obesity research. Obesity is one of the diseases that disproportionately affect the health of racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. For example, Blacks and Hispanics had a 51% and 21% higher prevalence of obesity, respectively, than did Whites in 2006 to 2008.14 Several translational research studies on obesity have been conducted leading to our understanding of the complex factors associated with the pervasiveness of obesity. The continuum of discoveries related to obesity from the cellular and molecular level to prevention and treatment have resulted in progress in combating the disease.15–17 Current research efforts are aimed at elucidating the complex genetic, behavioral, and social relationships causing obesity, with focused efforts to advance treatment and prevention using translational approaches.18,19

In general, translational health disparities research is a process that is needed to move our understanding of the science from discovery into policy and practice. The Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program was established at the NIH in October 2006 to provide an infrastructure that could accelerate clinical translational science from bench to bedside. The purpose of the CTSA Program is to assist institutions to forge an integrative academic home for Clinical and Translational Science. The intent of the awards is to consolidate resources to: (1) captivate, advance, and nurture a cadre of well-trained multi- and interdisciplinary investigators and research teams; (2) create an incubator for innovative research tools and information technologies; and (3) synergize multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary clinical and translational research to catalyze the application of new knowledge and techniques to clinical practice. The CTSA consortium is intended to serve as a magnet to concentrate basic, translational, and clinical investigators, community clinicians, clinical practices, networks, professional societies, and industry to facilitate the development of new professional interactions, programs, and research projects. It is anticipated that these new institutional arrangements will foster the development of a new discipline of clinical and translational science that will be much broader and deeper than would separate domains of clinical investigation. At least 8 of the 42 awardees of the CTSA program have some focus on health disparities,20 and 1 of the 5 goals adopted as a strategic goal for the CTSA consortium was “Enhance the health of our communities and our nation,” which includes implementing research best practices aimed at reducing health disparities.21

TRANSFORMATIONAL HEALTH DISPARITIES RESEARCH

Transformative or transformational research is a term that has been used by the National Science Foundation and defined as:

Research driven by ideas that have the potential to radically change our understanding of an important existing scientific or engineering concept or leading to the creation of a new paradigm or field of science or engineering. Such research is also characterized by its challenge to current understanding or its pathway to new frontiers.22

In adopting this term, we define transformational health disparities research as pioneering research that creates a new paradigm or concept in our understanding of health disparities. Transformational approaches in health disparities research is at the core of the “Kuhnian paradigm shift” described earlier. For health disparities research, we argue that this approach requires a fundamental change in philosophical position to raise an aspect of health inequality to a more significant level of scientific importance and investigation. Health disparity research is currently based on a synthesis of a great deal of biomedical, social, and behavioral science. The built environments in which people live and work have different structures (social, political, economic) that shape health. These differences in structure contribute to outcomes in the health and well-being of individuals and communities. In this context, transformational health disparities research considers structural inequalities and provides the basis for scientific innovation that will ultimately influence practical implementation in communities to improve health. The ideal outcome of transformational research is a paradigm shift that causes the scientific community to see problems in an entirely different way. Transformational research ideas are high risk and can be identified both prospectively and retrospectively. Because one cannot predict whether a transformational idea or approach will result in desired outcomes, it is still critical to engage in the research because knowledge is gained and lessons are learned. This is true whether the results prove to be transformational.

For example, transformational research identified prospectively and retrospectively was the discovery of the peptic ulcer disease caused by a bacterial infection. Warren observed bacteria colonizing the stomach in patients from which biopsies had been taken. He made the crucial observation that signs of inflammation were always present in the gastric mucosa close to where the bacteria were seen.23 Marshall, a young clinical fellow, became interested in Warren's findings and together they initiated a study of biopsies from 100 patients.24 After several attempts, Marshall succeeded in cultivating the unknown bacterial species (later denoted Helicobacter pylori) from several of these biopsies. Together they found that the organism was present in almost all patients with gastric inflammation, duodenal ulcer, or gastric ulcer.25 Based on these results, they proposed that H. pylori is involved in the etiology of these diseases. Against the prevailing theories that stress and lifestyle were the major causes of peptic ulcer disease, Marshall and Warren pioneered research that firmly established H. pylori as the cause for more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and up to 80% of gastric ulcers. Their discovery meant that this condition could be cured by antibiotics. This work has stimulated further research to better understand the link between chronic infections, stress, lifestyle, and diseases such as cancer.26–28

Transformational health disparities research begins with an understanding of the current state of the research and the context, culture, and values in which it exists. This provides a framework for creating a vision and formulating the research idea. A crucial component of this approach is the focus on innovation and testing of new ideas regardless of anticipated risks. Ideally the innovation proves useful and generates a transformational idea. There may be opponents or critics but, with time, the idea is adopted by the science community and becomes institutionalized.

We propose 6 general elements of transformational health disparities research:

Examination of the current institutional or societal culture;

Creation of idea with a vision or philosophical position;

Development of high risk idea;

Identification of the structural, systematic, or process changes that are needed with a focus on innovation;

Testing and implementation of the idea; and

Institutionalization of the new idea.

Transformational projects in health disparities tend to move the paradigm from detection and correlation studies to causation and intervention studies. An example of disparities research that has been transformational is the body of evidence from the British Whitehall studies. The results illuminated understanding on the phenomenon of the social gradient and health. The original Whitehall study investigated cardiorespiratory disease prevalence and mortality rates among male civil servants over a 10-year period and found a strong association between grade level of employment and mortality rates.29 These findings and subsequent studies on social determinants of health have spurred radical changes in the field and on health disparities research. Global interest led to the World Health Organization (WHO) creation of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Its recent report, Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health, succinctly summarizes the current state of knowledge and provides 3 overarching principles for reducing health inequalities: (1) improve daily living conditions; (2) tackle the unequal distribution of power, money, and resources; and (3) measure and understand the problem and assess the results of action. The implication of the social determinants approach to health disparities research is that the link between poor health and disease is often the result of social, political, and economic factors rather than biological ones. These nonbiological facts of life often contribute to ill health in populations that are socially, politically, and economically disadvantaged.30

In a prospective approach to transformative research, NIH launched the Transformational R01 Research Program in September 2008 under the NIH Roadmap Initiative to support “paradigm-shifting” research. This program supports

exceptionally innovative, high risk, original and/or unconventional research projects that have the potential to create or overturn fundamental paradigms.31

The studies are expected to forge the synthesis of new paradigms for biomedical or behavioral sciences, reflect an exceptional level of creativity, and promote radical changes in a field of study. Several of the 2009 awardees are pursuing research that will likely impact health disparity populations, such as “Transforming Cancer Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior Through Narrative,” and several projects related to obesity.32

TRANSDISCIPLINARY HEALTH DISPARITES RESEARCH

Transdisciplinary health disparities research is the application of an integrative approach to addressing and solving health disparities. It is research that involves practical problem solving not only of unmet needs but also of unrecognized needs in health disparity populations. Because of its focus on the present condition of health disparity populations, transdisciplinary health disparities research maintains close relationships with the communities or populations that are being impacted. It involves maintaining the partnerships and collaborations to advance or apply the research that has the potential to benefit the population. Transdisciplinary research depends on the synergy created by interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary science to understand, formulate, and address new research perspectives.

It is important to note the subtle difference between transdisciplinary research, interdisciplinary research, and multidisciplinary research, all of which have been described as approaches to cross-disciplinary research.33 The essential feature of transdisciplinary research is that it is a team approach with integrative and collaborative communication to blend disciplines or perspectives rather than shared discussions of different methods and disciplines, as in interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research. In multidisciplinary research, scholars from diverse fields work independently or sequentially, periodically coming together to share their individual perspectives for the purposes of addressing common issues. The researchers remain in the silos of their respective fields. In interdisciplinary research, participants may align concepts, combine methods from their different fields, but also work more intensively to integrate their divergent perspectives, even while remaining anchored in their own respective fields.34

Transdisciplinary research goes beyond multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research and transcends traditional disciplinary perspectives. Transdisciplinary teams involve scientists from multiple disciplines working together on a common problem (e.g., obesity and cancer) and using a common conceptual understanding or model to bring together elements from their respective disciplines as a means to define a new scientific approach. The result is the creation of new theory and new methods at the interface of traditional disciplines. Therefore, transdisciplinary research blur boundaries between disciplines, which sometimes may result in the creation of a new integrated discipline as a result of the team's work. An example of an integrated discipline resulting from this research approach is the emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI). PNI is the study of the interaction between psychological processes and the nervous and immune systems of the human body.35 PNI takes a transdisciplinary approach, incorporating psychology, neuroscience, immunology, physiology, pharmacology, molecular biology, psychiatry, behavioral medicine, infectious diseases, endocrinology, and rheumatology.

Transdisciplinary research approaches are conducted in the context of a new, common conceptual framework that transcends the frameworks used within the respective disciplines.33 Key features that facilitate the development of effective teams include (1) institutional support for the approach; (2) diverse team selection, which includes representation by all relevant disciplines and community members; (3) training, which provides cross-disciplinary education as well as opportunities for shared problem solving; (4) shared common language and goals to operationalize the research; and (5) multidirectional communication, which recognizes the contributions of all team members.36

An example of a process that involves integrative approaches and benefits from transdisciplinary research is community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR is defined by the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research as a

collaborative approach to research that begins with a research topic of importance to the community and combines community and academic knowledge toward a goal of promoting social change to improve community health and reduce disparities.37

As noted in the article by Minkler,

CBPR is not a research method but an orientation to research that emphases “equitable” engagement of all partners throughout the research process, from problem definition through data collection and analysis, to the dissemination and use of findings to help effect change.38(pS3)

The community and participating experts interact in an open dialogue, accepting each perspective of equal importance and relating different perspectives to each other. The NCMHD currently sponsors a CBPR initiative that supports the development, implementation, and evaluation of intervention research to foster sustainable efforts at the community level.39 This is a long-term commitment by the NCMHD with potential continuous funding for up to 11 years in individual CBPR projects for translational and transdisciplinary research.

The CBPR initiative is implemented in 3 phases: a 3-year planning phase, a 5-year intervention research phase, and a 3-year research dissemination phase. The Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities (CPHHD) program was established by the NIH to examine the highly complex nature of health disparities and their effects on health. The program is inherently transdisciplinary and provides a unique environment in which to perform health disparities research. The 8 CPHHD centers are tasked with improving the understanding of and reducing the differences in health outcomes, access, and care in health disparity populations. The centers focus on the social and physical environment, behavioral factors, and biologic pathways that interact to determine health and disease in populations and are at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of Chicago, Tufts and Northeastern Universities, the RAND Corporation, the University of Texas Medical Branch, The Ohio State University, Wayne State University, and the University of Pennsylvania.40

BRIDGING RESEARCH TO ADVANCE HEALTH DISPARITIES

As health disparities researchers, we are aware of the charge of providing perspectives for public health, practice, and policy advocates. We seek not only to provide the science to understand health disparities but also to improve health. Our research goals are ultimately to make things better not just for individuals, but for the population as well. We do not simply seek to improve health by informing individuals and populations of their health risks; we also seek to use science to influence society and the policies that shape health. Determinants of health and disparities are largely behavioral, social, and economic. Ultimately, however, these determinants are influenced by the larger macroenvironment in which people live and the policies that govern their society. In this paradigm-shift, health disparities science should be an integration of translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary research to effectively tackle the inherent complexities of the problems and the society.

We should emphasize that translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary research are critical for innovation and paradigm shifting. But by themselves, they are not enough. The elimination of health disparities will also call for sound philosophical principles, ideals of fairness, and a commitment to social justice. Disparity in the context of public health has taken on the implications of social injustice. Health disparities are rooted in social structure inequalities and exist because of inequitable distribution of goods, resources, power, and poverty in American society. The challenges to health disparities will remain unless we address these broader social factors together with translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary research. History teaches us that pioneering research achievements have been the result of a systemized integrative effort.

If health disparities research and dissemination of results is challenged and reframed to apply these approaches, and if the investments are used to support systems with community engagement, the progress in science to eliminate health disparities will accelerate and ultimately close the health inequality gap.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the exceptional contribution and insightful comments from Kester Williams, MA, in the final draft of the article. The authors also wish to thank Ligia Artiles, MA, for her assistance in editing, preparing, and submitting the article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol activity was required because no human participants were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Pearson TA, Manolio TA. How to interpret a genome-wide association study. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1335–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varmus HE. Statement before the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services and Education, February 23–24, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Public Law 106–525 Minority Health and Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act of 2000. 106th Congress 2d session, November 22, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what do the patterns tell us? Am J Public Health. 2010;S1:S186–S196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Discussion paper for the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Draft. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_framework_action_05_07.pdf Accessed November 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner E. Socioeconomic determinants of health: stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ. 1997;314:1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senese LC, Almeida N, Fath AK, Smith BT, Loucks EB. Associations between childhood socioeconomic position and adulthood obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):21–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 1999;318:1460–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research First-time investigators. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008. Available at: http://report.nih.gov/NIH_Investment/PPT_sectionwise/NIH_Extramural_Data_Book/NEDB%20SPECIAL%20TOPIC-FIRST%20TIME.ppt#383,1,FIRST-TIMEINVESTIGATORS. Accessed November 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thompson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317(7156):465–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best A, Stokols D, Green L, Leischow S, Holmes B, Bucholtz K. An integrative framework for community partnering to translate theory into effective health promotion strategy. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18(2):168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. A review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Differences in prevalence of obesity among Black, White, and Hispanic adults—United States, 2006–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:740–744 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perusse L, Rankinen T, Zuberi A, et al. The human obesity gene map: The 2004 update. Obes Res. 2005;13(3):381–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell-Anderson KS, Bryson JM. Leptin as a potential treatment for obesity: progress to date. Treat Endocrinol. 2004;3(1):11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farooqi IS, Keogh JM, Yeo GS, et al. Clinical spectrum of obesity and mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1085–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skelton JA, DeMattia L, Miller L, Olivier M. Obesity and its therapy: from genes to community action. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:777–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisbon N, Plumb J, Brawer R, et al. The asthma and obesity epidemics: the role played by the built environment—a public health perspective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):1024–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Research Resources Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Directory [Web site]. National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/clinical_research_resources/clinical_and_translational_science_awards/consortium_directory. Accessed November 15, 2009

- 21.Clinical and Translational Science. Awards. Advancing scientific discoveries nationwide to improve health. Progress report 2006–2008. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2009. Available at: http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/clinical_research_resources/clinical_and_translational_science_awards/publications/2008_ctsa_progress_report.pdf Accessed November 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Science Board Enhancing support of transformative research at the National Science Foundation. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation; 2007. Available at: http://www.nsf.gov/nsb/documents/2007/tr_report.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JR, Marshall BJ. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1(8336):1273–1275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1(8390):1311–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall BJ, McGechie DB, Rogers PA, Glancy RJ. Pyloric campylobacter infection and gastroduodenal disease. Med J Aust. 1985;142:439–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waris G, Ahsan H. Reactive oxygen species: role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J Carcinog. 2006;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Line S, Manuck SB, Rabin BS, Heise ER, Kaplan JR. Chronic social stress, social status, and susceptibility to upper respiratory infections in nonhuman primates. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(3):213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-associated immune modulation: relevance to viral infections and chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med. 1998;105(3A):35S–42S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marmot MG, Davey Smith G, Stansfeld SA, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337:1387–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commission on Social Determinants of Health, World Health Organization Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html. Accessed September 16, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives, National Institutes of Health. Transformative R01 Program. [Web site]. Available at: http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/T-R01/index.asp. Accessed November 20, 2009.

- 32.Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives, National Institutes of Health 2009 Transformative R01 Award recipients. Available at: http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/T-R01/recipients09.asp. Accessed November 20, 2009

- 33.Rosenfield PL. The potential of transdisciplinary research for sustaining and extending linkages between the health and social sciences. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1343–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein JT. Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: a literature review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2S):S116–S123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irwin M, Vedhara K, Human Psychoneuroimmunology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruddy G, Rhee K. Transdisciplinary teams in primary care for the underserved: a literature review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, US Dept of Health and Human Services. 2007 Summer Institute on the Design and Development of Community-Based Participatory Research in Health. [Web site]. Available at: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/summerinstitute2007/about.html. Accessed November 20, 2009.

- 38.Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S81–S87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD), National Institutes of Health. NCMHD Community-Based Participatory Research Initiative. [Web site]. Available at: http://ncmhd.nih.gov/our_programs/communityParticipationResearch.asp. Accessed November 20, 2009.

- 40.Holmes J, Lehman A, Hade E, et al. Challenges for multilevel health disparities research in a transdisciplinary environment. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2S):S182–S192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]