Abstract

An African American male to female transgender patient treated with estrogen detected a breast lump that was confirmed by her primary care provider. The patient refused mammography and 14 months later she was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer with spinal cord compression. We used ethnographic interviews and observations to elicit the patient’s conceptions of her illness and actions. The patient identified herself as biologically male and socially female; she thought that the former protected her against breast cancer; she had fears that excision would make a breast tumor spread; and she believed injectable estrogens were less likely than oral estrogens to cause cancer. Analysis suggests dissociation between the patient’s social and biological identities, fear and fatalism around cancer screening, and legitimization of injectable hormones. This case emphasizes the importance of eliciting and interpreting a patient’s conceptions of health and illness when discordant understandings develop between patient and physician.

KEY WORDS: transgender, breast cancer, estrogen, ethnography

INTRODUCTION

Patients and physicians frequently inhabit different social worlds. The discussion between these individuals about illness and treatment is therefore prone to misunderstandings. Often these misunderstandings are recognized by the participants and settled through questions and answers. On occasion, however, an impasse develops where the physician struggles to understand the patient’s behaviors. A patient’s rejection of evaluations and treatments that offer potential for well-established biomedical improvement can be particularly perplexing. When common explanations (e.g. access to care, socioeconomic factors, etc.) are not apparent, the clinician may resort to inaccurate assumptions or abandon the pursuit of an explanation, which can lead to detrimental outcomes1. This case report presents an African American transgender patient who declined evaluation of a breast mass and subsequently developed metastatic breast cancer. It outlines an ethnographic approach to engage cultural and psychosocial elements on an occasion where a seemingly inexplicable impasse arose between provider and patient.

METHODS

Data for this report was generated by three in-depth interviews with the patient, daily observations in the hospital for nearly four weeks, two phone interviews with the primary care provider, and review of the medical record. Interviews with the patient were conducted while the patient was psychiatrically stable and receiving daily quetiapine. Questions for the interviews were based on Kleinman’s2,3 ethnographic approach with greater detail elicited by using Hammersley and Atkinson’s4 principles of qualitative interviewing. A single reviewer (AD) analyzed the data using constant comparison procedures5 including repeated reading of the data, comparison between different passages, literature consultation, and clustering of data with derivation of themes using TamsAnalyzer6. We obtained informed consent from the patient before the research began.

CASE

A 58-year-old African American male to female transgender patient was brought to the emergency room for inability to walk and urinate.

Approximately 14 months prior to presentation the patient’s primary care provider noticed a lump at the 4 o’clock position of her left breast. The patient declined mammography and biopsy, which were not discussed again on subsequent visits. Eleven days prior to admission, the patient developed low back pain and lower extremity weakness. She gradually became unable to walk to the bathroom and resorted to urinating in cups and clothing near her bed. Three days prior to admission, she was unable to urinate and her lower abdomen became swollen.

The patient’s medical history included schizoaffective disorder and hypertension. She received estrogen treatment from local clinics between 1969–1978 and 1995–1997 and underwent silicone breast implantation in Mexico. Her medications included benazepril, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and unspecified psychiatric medications that she had not taken for the last six days. Her mother had survived an unknown cancer that was treated with chemotherapy. The patient lived in community housing and worked at local car washes and soup kitchens. She did not smoke tobacco or drink alcohol in excess, but she did use intravenous cocaine, speed, and methamphetamines regularly.

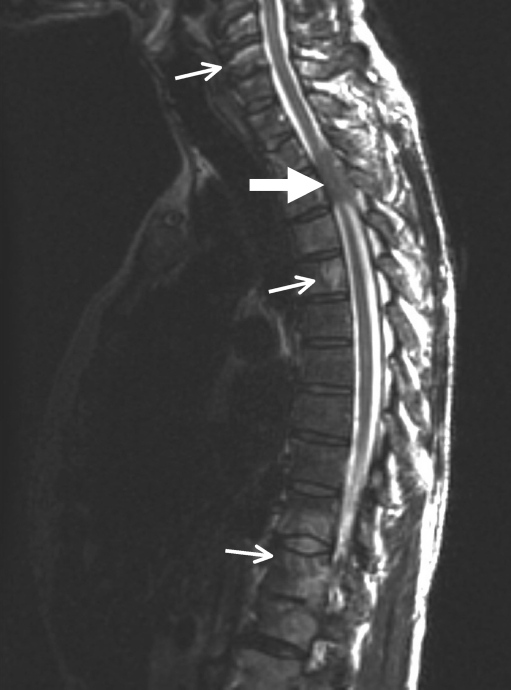

A massively distended bladder, decreased rectal tone, decreased muscle strength in the lower extremities (left > right), and bilateral ankle clonus were detected on examination. Vital signs and the remainder of the general physical exam were normal except for a 5 × 5 cm firm, non-tender mass in the 3 to 4 o’clock position of the left breast and fixed adenopathy in the left axilla. MRI of the spine showed cord compression at T3 by a soft tissue mass and marrow signal changes in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral bodies (Fig. 1). The patient repeatedly refused fine needle aspiration of the breast mass, but after the urging of multiple physicians, she agreed. Pathology revealed tumor cells that had 3–4+ positivity for estrogen receptor and 4+ positivity for progesterone receptor consistent with adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

MRI without contrast showing T3 cord compression by a soft tissue mass (large arrow) and marrow signal changes in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral bodies (small arrows).

Her neurologic function improved after ten rounds of radiation therapy and high dose steroids. After further treatment with tamoxifen and prednisone, MRI revealed regression of the T3 mass and decompression of the spinal cord but persistent diffuse bony metastasis with a compression fracture at T12. Her outpatient oncologist continued tamoxifen and planned to add zoledronic acid as her prednisone was tapered and discontinued.

Two months after admission, the patient had normal bladder function and walked with an assistive device at a rehabilitation hospital. Her breast mass was unchanged at her last outpatient appointment.

PATIENT’S CONCEPTIONS

The patient stated that she first noticed the breast mass ten months prior to her admission (underestimating the true interval by four months). She understood that her primary care provider advised mammography and biopsy, but she declined because “I had many lumps because of the silicone.” When asked what she thought about the breast cancer, she stated: “It probably involves silicone mixed with tissue.” She did not expect the lump to be breast cancer because: “I have a male chest with hormones and silicone, and I didn’t expect to get breast cancer. Men and women cancers are different.”

When asked what caused the problem, she stated: “Drinking the water in Bayview [a San Francisco neighborhood].” She followed up with the association: “My landlord has breast cancer as well.” She explained why she did not want a biopsy: “I didn’t want to cut it because that will make it spread. I also didn’t want to know [the results]. My landlord has breast cancer and had both breasts reduced. I also didn’t want to hurt my heart muscle, which is on the left. If the lump were on the right, then that would be okay.”

The patient also made a distinction between estrogen pills and injections: “Pills are worse than injections. They give you breast cancer. Injections are more pure. They make you into a woman. Injections don’t cause breast cancer because you pee it out in 24 hours. Pills stay longer because you take the pill everyday. Pills can cause breast cancer.”

DISCUSSION

Although both participants identified a breast lump and discussed the possibility of cancer in this case, the patient declined investigations until metastases developed. The reasons for declining a seemingly simple diagnostic test with the potential for curative treatment were not apparent. However, in-depth investigation of the patient’s conceptions provided explanations and demonstrated how physicians may uncover beliefs that are not expected because of their different educational, social, or demographic status. Here we explore three cultural and psychosocial issues derived from the patient’s conceptions that provide insight into the patient’s actions and the development of misunderstandings.

This patient displayed a complex identity construction. Her social identity was feminine highlighted by her preference for a female name and female body signifiers, including her silicone breasts, hip padding, and choice of clothing. At the same time, she self-identified her chest as a “male chest” that she believed provided immunity against breast cancer. Therefore her female social identity and her male biological identity were dissociated when the patient was evaluating her risk for breast cancer. Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-Text Revision7 has diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorder, defined as “evidence of strong identification of the opposite gender and persistent discomfort with one’s assigned sex,” it does not describe this complex identity construction. In such cases, the clinician will gain more insight from the patient rather than the reference book. This approach provides the opportunity to learn how transgender patients may attribute explanatory power to these identity constructions, thereby affecting their risk assessments, healthcare decisions, and behaviors.

The patient’s fear of ‘cutting’ the mass and denial of the results are well described in the literature on socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Loehrer et al.8 report 37% of their sample of county hospital patients with cancer believed that “surgery causes cancer to spread.” Peek et al.9 describe that despite health education efforts in their sample of low-income African American women, many of their participants held the idea that “surgery causes cancer to spread (and would therefore be unnecessary or harmful),” and that a common response to this fear was denial and repression. The authors discuss that these fears, denial, and repression surrounding screening lead to cultural norms of delaying and avoiding testing until diseases manifested, a trend now well-established in the literature10–12. Therefore, a clinician should consider that a patient’s aversion to testing is not exclusively an individual trait; rather it may be a manifestation of a larger cultural pattern characterizing the patient’s social context.

Patients’ beliefs about medications influence their behaviors and interactions with the medical system. In this case, the patient preferred injections because they were effective in her transformation and she felt that rapid expulsion rendered them less harmful than daily pills. Differences between the experiences of taking injections versus oral medication may underlie this patient’s perception. Pills, although prescribed by a medical professional, are self-administered by the patient on a daily basis. Injectable estrogens, conversely, are usually administered by a medical professional in a clinic setting once a month (although other frequencies exist). Therefore, injections have decreased presence in daily life, and may be associated with greater legitimacy and safety by being administered in a medical setting by a professional, who performs the key role of gatekeeper in the transformation process13. It is important for providers to appreciate how patients’ conception of the effects and risks of medication may be influenced by route, frequency, and source of administration.

This case illustrates discordance between clinician and patient understandings and its unfortunate consequence. This patient’s actions were partly informed by her specific ideas about biological identity, fears of medical testing, and medication risks and benefits. Although eliciting this culturally tuned history is a challenge for the busy physician, it is imperative in such cases. In addition to the ethnographic approach revealed in this paper, we provide a set of practical strategies derived from cultural and communications literature to aid in these interactions (text box 1)3,14–16. The goal of this process is not to assure compliance with the physician’s biomedical treatment regimen, but to reach a point of common understanding to meet the biopsychosocial needs of the patient. Utilizing such strategies provides identification of the impasse, clarification of the misunderstandings, and opportunities for shared decision-making.

Acknowledgements

None disclosed.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. Public library of science medicine. 2006;3(10):1673–1676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: Principles in practice. 2. London: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 6.TamsAnalyzer WM. A qualitative research tool. In. 2.49b7 ed. Boston, MA: Free Foundation; 2004

- 7.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loehrer PJ, Greger HA, Weinberger M, et al. Knowledge and beliefs about cancer in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. Cancer. 1991;68:1665–1671. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911001)68:7<1665::AID-CNCR2820680734>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peek ME, Sayad JV, Markwardt R. Fear, fatalism and breast cancer screening in low-income African-American women: The role of clinicians and the health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1847–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidry JJ, Matthews-Juarez P, Copeland VA. Barriers to breast cancer control for African-American women: The interdependence of culture and psychosocial issues. Cancer. 2003;97(1 Suppl):318–323. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirschman J, Whitman S. The black:white disparity in breast cancer mortality: the example of Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:323–333. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masi CM, Gehlert S. Perceptions of breast cancer treatment among African-American women and men: Implications for interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):408–414. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekins R. Male femaling. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings: opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Perez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: Whenever we prayed, she wept. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(10):1047–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wear D. Insurgent multiculturalism: Rethinking how and why we teach culture in medical education. Acad Med. 2003;78:549–554. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]