Abstract

Background

Clinicians, public health practitioners, and policymakers would like to understand how youth perceive health issues and how they can become advocates for health promotion in their communities. 1,2 Traditional research methods can be used to capture these perceptions, but are limited in their ability to activate (excite and engage) youth to participate in health promotion activities.

Objectives

To pilot the use of an adapted version of photovoice as a starting point to engage youth in identifying influences on their health behaviors in a process that encourages the development of health advocacy projects.

Methods

Application of qualitative and quantitative methods to a participatory research project that teaches youth the photovoice method to identify and address health promotion issues relevant to their lives. Participants included 13 students serving on a Youth Advisory Board (YAB) of the UCLA/RAND Center for Adolescent Health Promotion working in four small groups of two to five participants. Students were from the Los Angeles, California, metropolitan area.

Results

Results were derived from photograph sorting activities, analysis of photograph narratives, and development of advocacy projects. Youth frequently discussed a variety of topics reflected in their pictures that included unhealthy food choices, inducers of stress, friends, emotions, environment, health, and positive aspects of family. The advocacy projects used social marketing strategies, focusing on unhealthy dietary practices and inducers of stress. The youths’ focus on obesity-related issues have contributed to the center’s success in partnering with the Los Angeles Unified School District on a new community-based participatory research (CBPR) project.

Conclusion

Youth can engage in a process of identifying community-level health influences, leading to health promotion through advocacy. Participants focused their advocacy work on selected issues addressing the types of unhealthy food available in their communities and stress. This process appears to provide meaningful insight into the youths’ perspective on what influences their health behaviors.

Keywords: Photovoice, advocacy, health, participatory research, nutrition, stress

Clinicians, public health practitioners, and policymakers would like to understand how youth perceive health issues and how they can become advocates for health promotion in their communities.1,2 Traditional research methods can be used to capture these perceptions, but are limited in their ability to activate (excite and engage) youth to participate in health promotion activities. We conducted a pilot study using an adapted version of photovoice as a starting point to explore these issues.

Photovoice is a CBPR method that involves giving cameras to people to take photographs that illustrate issues that concern them.3 Grounded in the tradition of empowerment education,4 photovoice aims to give voice through photos to people who might not otherwise have the power, opportunity, or audience to have their perspective on issues heard by others. It has been used in particular to highlight social and environmental factors that can affect health and to advocate for improvement in health for communities. This approach has been used with hard-to-reach populations, disenfranchised groups, and others in the United States (e.g., youth,5 the homeless,6 breast cancer survivors7) and internationally (e.g., women in rural China8,9).

A method similar to photovoice has involved providing video cameras to children with chronic illness; this approach has been associated with improved quality-of-life measures in children and adolescents with asthma,10 helped to identify previously unrecognized home triggers of asthma,11 and provided a window into how adolescents live with their diabetes mellitus.12 Although video and still photography are different in many respects, both provide a window into the life perspective of the participants and the opportunity to identify components of their social and physical environment that they perceive as influencing health.

Several reports describe youth participation in photovoice activities aimed at empowerment on health issues,5,13,14 although there has been little information on the impact of these efforts. We sought to pilot an adapted version of photovoice with adolescents living in low-income Los Angeles area neighborhoods recognized for health disparities. Our goal was to give youth the opportunity to express and explore their perspectives on what influences health in their communities.

METHODS

We used photovoice and an associated skills building program to engage a group of youth in a dialogue about health and to encourage development of community health advocacy projects. We gave students digital cameras and suggested they photograph images related to health and things that influence health. The photovoice method was modified when participants expressed interest in using their digital images for creative forms of expression to share with their peers, families, and communities. Each student identified major themes from his or her own pictures. They then developed posters, based on the themes, to promote health.

Participant Recruitment

Thirteen of the sixteen members of the YAB from the UCLA/RAND Center for Adolescent Health Promotion participated in the Teen Photovoice Project. All YAB participants were eligible and invited to participate in the project. These students had been recruited from Los Angeles area community organizations and afterschool programs to bring the perspectives of youth to research projects conducted at the Center. Parents gave consent, and youth gave assent. Study procedures were approved by the UCLA Human Subjects Protection Committee.

To engage youth and their parents, members of the research team participated in YAB activities and events hosted by the center and the community partners during the year before introducing the idea of a research project. This process gave the YAB members, their parents, and the staff of their sponsoring organizations time to get to know researchers not already working with the YAB. Parental and organizational buy-in were essential to implementing the project. They were involved along with the students in developing plans for the project.

Community Advisory Board

The center also has an adult Community Advisory Board (CAB) that includes partners from schools, community-based organizations, the public health department, and parents who bring their perspective to research projects conducted at the center. Members of the CAB served an advisory partner role and provided input into the development of the pilot, and tracked the project’s progress.

Participant Socioeconomic Status

Participant zip codes were used to obtain their neighborhood’s federally defined poverty level based on the 2000 U.S. Census.15

Equipment

We gave each student a point-and-shoot Minolta DiMage 3.1 megapixel digital camera, an extra memory card to store digital pictures, photo-editing software, USB cable, and a laminated card with instructions describing the project. Participants also received a photo album for organizing their pictures, written narratives, and other photovoice documents.

Photovoice Activities

Teen Photovoice Sessions

The photovoice program consisted of nine 2-hour sessions over the course of 5 months and was designed to stimulate dialogue among the participants, using their photographs as discussion catalysts (Table 1). Participant’s parents and community partners advised that the project should provide some guidance for what the youth would photograph. We proposed that the students take pictures in their communities of images “that contribute to healthy or unhealthy activities.” Although traditional photovoice projects often provide limited guidance, the proposed topic was broad and fit within the mission of the YAB to address health issues facing youth and their families.

Table 1.

Teen Photovoice Sessions

| Session 1–All participants |

| Introduction to the project goals |

| History of the photovoice methodology |

| Ethics of taking photographs in the community |

| Group discussion on the meaning of health |

| How to obtain consent to photograph human subjects |

| Camera operation |

| Photographic techniques and examples of photographs |

| Session 2–Community |

| (pictures were downloaded and printed between sessions 1 and 2) |

| A brief introduction to qualitative research methods |

| Unconstrained pile sorts and theme generation |

| Discussion of student selected photographs using the SHOWeD method (recorded for transcription) |

| Session 3–Community |

| Unconstrained pile sorts and theme generation |

| Discussion of student selected photographs using the SHOWeD method (recorded for transcription) |

| Student created narratives on selected pictures while others discuss pictures |

| Session 4–Community |

| Unconstrained pile sorts and theme generation |

| Discussion of student selected photographs using the SHOWeD method (recorded for transcription) |

| Student created narratives on selected pictures while others discuss pictures |

| Session 5–Community |

| Selection of top 10 themes |

| Review of data that were available (histograms, network analysis, and multidimensional scaling) |

| Consideration of potential products |

| Session 6–Community |

| Constrained pile sort of the130 pictures that were discussed using the SHOWeD method into theme piles. Discussion of other photovoice projects, products, advocacy, and aspects of social marketing |

| Product brainstorming |

| Students are asked to research ideas at local libraries and on the Internet (if an option) |

| Session 7–Community |

| Continued product idea development |

| Review of current data (network analysis and multidimensional scaling) |

| Collaboration with a graphic artist to help students create products |

| Session 8–Community |

| Review and editing of products |

| Consideration of venues to host debut |

| Generate list of people students would like invited to event |

| Session 9–Community |

| Agreement on final products |

| Discussion of student’s role at the California Science Center Debut (speaking with the news was voluntary, but did require the completion of an additional release by the student and their parent or guardian) |

| Last group meeting—California Science Center |

| Press release, brief meet and greet, viewing of the framed posters in the museum |

| Time for students to speak with the press |

| Closing remarks, certificates of participation and recognition of community organizations |

Participants were told that they should only take pictures that did not pose a threat to their safety or violate any person’s privacy (participants obtained oral permission for any pictures where the main subject was an individual or small group of individuals). When pictures with identifiable individuals were selected for use in project activities, the researchers confirmed receipt of verbal consent with the youth who took the photograph.

Pile Sorts and Semistructured Interviews

Once participants had taken their photographs, they engaged in three main activities during the group sessions: pile sorting, identifying themes in their piles, and using the photographs and results from the pile sorts as catalysts for discussion.

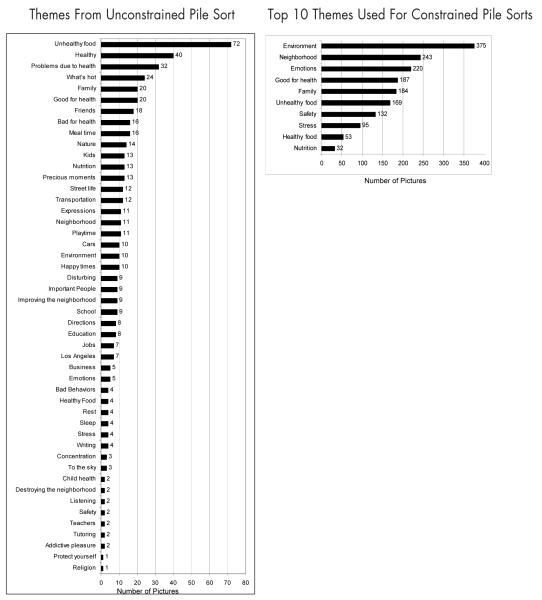

The youth engaged in unconstrained and constrained pile sorts.16 First, they downloaded and archived their photographs, and then they selected 20 images to print for activities (each participant was encouraged to review pictures using their camera’s LCD screen and provided with a CD-ROM containing all of their pictures for use on a PC). Members of the research team were available to assist with these processes. For unconstrained pile sorts, they individually sorted their 20 pictures into piles that they felt had a unified theme and assigned a theme name to each pile. All themes were put on a list. Participants used a seven-item rating scale with anchors for the endpoints (must drop, must keep) to score the themes. Ten themes with the highest scores were selected (Figure 1) for the second type of pile sort, constrained pile sorts, which required individuals to sort the large set of everyone’s pictures (130 pictures, 10 pictures contributed by each participant and used for the semistructured interview, described below) into the 10 themes. This process gave the youth an opportunity to think about what common issues the pictures represented.

FIGURE 1.

The themes generated by the unconstrained pile sort and themes selected by students for the top ten theme list (number of pictures placed in piles).

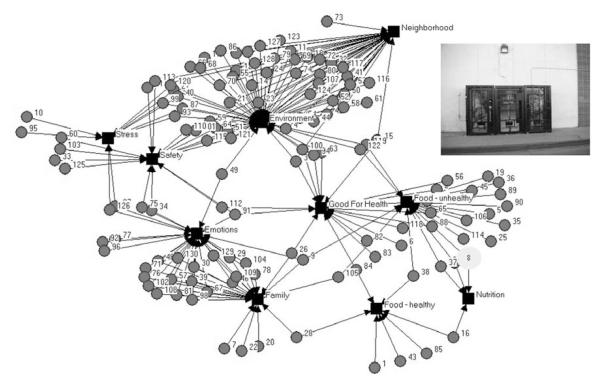

Multidimensional scaling analyses (MDS) and two-mode network analyses were performed on constrained pile sort data using the 10 defined themes and sorted pictures to create working correlation matrices. MDS is a multivariate data reduction technique that can be used to look for relations among a large set of observations that contain nonmetric measures.17 Two-mode network analyses provided the ability to look at patterns of relations reflecting how participants sorted pictures into similar or different themes. Both MDS and two-mode network analyses provided a means of presenting relational data in compact and systematic forms18 to the participants. Participants were asked to interpret the relationships between piles and pictures to foster a better understanding of how they perceived the pictures and themes. For example, Figure 2 shows a two-mode network analysis of all participants’ constrained pile sort data, and a segment of a photographer’s narrative on her picture bridging two themes. The number of times a particular picture was sorted to a specific theme (i.e., tie strength) was also available for the participants, although it does not appear in the figure.

FIGURE 2.

2-mode network analyses on the constrained pile sort of 130 pictures sorted by all participants. The following segment of narrative was taken from the participant’s comments on the highlighted picture (#8, upper right of figure) that bridges “Nutrition” and “Food – unhealthy.” “[T]he school is very strict with the vending machines. They’re supposed to take them out, and I don’t know. But the vending machines are still there … They [the students] eat whatever is there, whatever is given to them.”

In addition, the participants each selected 10 pictures that he or she felt best illustrated their perspective on health issues that concern them. These 10 photographs served as the basis for multiple group discussions in addition to semistructured, one-on-one interviews between a member of the research team and each participant, with other participants observing. These interviews gave the participants an opportunity to articulate and express their thoughts on each image. The interviews proceeded according to the “SHOWeD” mnemonic method.19 This method uses five sequential questions (What did you see here? What is really happening? How does this relate to our lives? Why does this problem or strength exist? What can we do about it?) to stimulate discussions and get participants to focus on the meaning of each picture. During discussions, participants were encouraged to consider how to best use their pictures to promote health among their peers. A variety of topics covered during these discussions fall into the realm of social marketing.20 For example, they considered how to get people to hang their pictures and proposed to make a calendar because people like to keep their calendars in a visible place.

Working together allowed the participants to develop a shared way of thinking and talking about a common set of issues. This process of creating a common language facilitated the youths’ translation of project findings into advocacy products they could use to educate others and advocate for change.

RESULTS

Demographics

Thirteen 13- to 17-year-old youths participated in the project: 11 were female; 9 were African American, 3 Mexican American, and 1 Asian. They attended both public and parochial schools, and lived in Los Angeles area communities in which 4% to 39% of the families with children lived below the poverty level.

Social Marketing Products

Participants collectively took more than 3,500 digital pictures (range, 115 to 680), a portion of which they selected and used for pile sorting activities. Figure 2 lists the pile names and the number of pictures the participants sorted into the piles during unconstrained and constrained pile sort activities. A large number of “unhealthy food” pictures were selected by participants from their own pictures and themes they identified in the unconstrained pile sort activities. The constrained pile sort resulted in a high number of pictures being sorted to the “unhealthy foods” (unlike “healthy foods,” which were not as common), “emotions,” “environment,” “family,” “good for health,” and “neighborhood” themes. Conducting these activities and providing the participants with the results in different forms (e.g., MDS and two-mode network analyses) allowed them to consider each other’s perspective, which appeared to help them to identify common problems in their community that they might want to change and helped to activate their development of advocacy projects. The participants focused on projects to communicate their findings to peers and school staff.

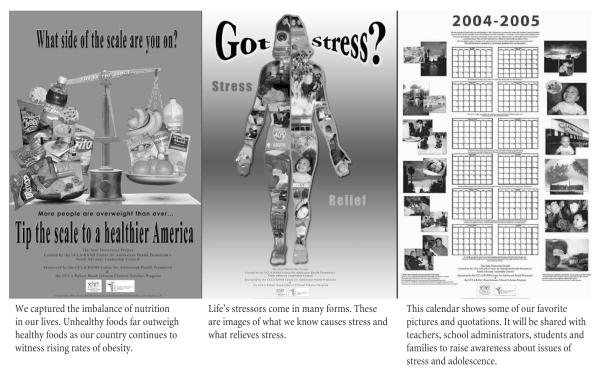

Posters

Working in small groups, participants selected a concept for a health education poster, pictures to use in the poster, and appropriate text to communicate their message. Participants collaborated with a graphic artist to create three posters that would meet specifications for high-quality printing (Figure 3). The posters reflected the youths’ interest in addressing nutrition, stress in the community, and stress in the school setting, with a social marketing approach. Center and CAB partners, staff from the participants’ community organizations, parents, a graphic artist, and other UCLA faculty and students provided feedback during poster development.

FIGURE 3.

The three posters displayed at the California Science Center and student-created captions articulating their intent.

“What Side of the Scale Are You On?”

This poster reflects the participants’ desire to raise peer awareness about how dietary choices in their neighborhoods disproportionately favor unhealthy, high-calorie foods and not healthier fresh fruits and vegetables.

“Got Stress?”

Participants intended this poster to mimic the “Got Milk?” advertising campaign. The poster contrasts images that the youth associated with stress (“stress” side) and those associated with relieving stress (“relief ” side). After debating whether competitive sports belonged on the stress side (from anxiety over trying to win) or the relief side (because exercise relieves stress), the participants settled on the relief side.

“The Stress Calendar”

In this poster, participants wanted to disseminate their message about stress in the school setting. They thought that a calendar would be a good way to share their message. The youth wanted school teachers and administrators to know about and acknowledge the high levels of stress that students face during the school year.

Copies of all three posters were provided to participants, their schools, community partners, and other parties interested in helping disseminate these social marketing messages. The posters were displayed at the California Science Center, a large, free, interactive science museum in Los Angeles. The opening for the exhibit drew participants, family, community partners, public health officials, local college advisors, physicians, the press, and others. The Los Angeles Times reported on the exhibit in an article that included interviews with some of the youth; this article was reprinted in various newspapers and wire services around the country, including the BostonGlobe. com, the Houston Chronicle, Knoxville News, Los Angeles City News Service, the Redding News, University of California News Wire, and the Daily Herald in Provo, Utah. The story was also covered on a local television news broadcast (KTLA, the Los Angeles WB affiliate). Hoy, a Spanish-language newspaper, and Sing Tao, a Chinese-language newspaper in Southern California, also wrote articles on the project.

Advocacy in School Food Services

Although most students focused on their group projects, one student on her own volition took her pictures of the unhealthy food sold in her school cafeteria to her school’s Director of Food Services and asked why there were no healthy options. She reported that her school cafeteria subsequently offered more nutritious food options for a 2-week period. Although typical items remained, the cafeteria added granola, yogurt, and whole fruits to its menu, and placed these foods physically in front of the less healthy options to encourage selection by the students. She was the only project member attending her school, but she shared her experience with other project members. She encouraged them to consider the effect of the school cafeteria environment on their health and the broader potential impact of their project.

Advocacy with the Center

Although only one group decided to focus their advocacy project on issues of nutrition, food access in their community, and its effect on the obesity epidemic, every group was concerned about obesity. In meetings that took place after the pilot was completed, the participants encouraged the center to conduct more research on youth obesity using participatory methods. The center’s CAB and community partners made the same recommendation. The center partnered with the Los Angeles Unified School District in applying for a grant from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health to conduct a CBPR project to prevent youth obesity. The grant was funded in September 2005.

DISCUSSION

This photovoice experience provided students with the opportunity to collect and interpret qualitative data on what they felt was influencing their health through the lens of a camera. The pictures were explored both at an individual and group level in a process that engaged the participants in health advocacy endeavors.

The poster products reflect the youths’ focus on advocating for reducing stress in relationships and in schools, and addressing the ways in which community food choices influence weight gain. Local obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile) prevalence data for youth 12 to 19 years old from the Los Angeles County area are 19.0%21 compared with 17.4% nationally.22 To this end, youth created posters using social marketing strategies that were intended to foster change among their peers.

Social marketing applies commercial marketing principals to influence social behaviors that benefit the individual and general population, not the marketer. These include audience segmentation, message targeting, and product branding, placement, pricing, promotion, and positioning.20,23 Social marketing for health promotion strategies incorporates behavior change theories like social cognitive theory,24 the theory of reasoned action,25 and the theory of planned behavior25 to identify modifiable behavioral determinants that will likely respond to persuasive appeals. These strategies also incorporate communication theories such as the elaboration likelihood model26 to increase the persuasive impact of messages and the likelihood that messages will affect specified behavioral determinants. In addition, it acknowledges that the tactics and strategies used to augment health behaviors must reflect and adapt to the constantly changing marketplace. Youth using photovoice are well positioned to capture their unique perspective on their community’s changing marketplace.

In addition, project participants focused on social marketing elements that they considered important (e.g., audience segmentation, message targeting, and product placement). They applied these strategies by using visual images, and phrases that they considered compelling to their peers, teachers, school staff, policymakers, and others. These products represent the participants’ use of social marketing strategies to advocate for improvement on the health issues they selected. The application of digital images, and compelling text, and the use of a poster format to mobilize public opinion, is a form of media advocacy.

Although we saw a significant activation of the youth and engagement in the issues addressed, we did not have a control group. Although our sample size was similar to those in projects using video narratives with children with chronic illness, it was nonetheless a small convenience sample, so making broader generalizations from the findings should be done with caution. Nonetheless, this pilot can serve as an example for others who would to adopt or modify it for their particular communities.

For the year before coming up with the project idea, we developed relationships with the youth and their parents by participating in YAB, CAB, and community partner activities. This step was important for establishing trust between the research staff and participants, and developing the project structure and dissemination. The participatory approach also produced important benefits. The participants selected the issues they wanted to address and made a major contribution to understanding their data. In addition, this work inspired the participants to continue voicing their concerns about youth obesity to the Center, which responded by successfully competing for an NIH CBPR grant to advance work on this issue.

This project supports anecdotal reports from previous studies about participants’ enthusiasm for the photovoice experience.5,13,14 Photovoice can actively engage students in a process of identifying community-level health influences and creating advocacy approaches to promoting health. The project was successful in voicing its findings to a larger audience through the exhibition, media coverage, community presentations, continued presence of the posters in participants’ schools and community centers, and its influence on the center’s pursuit of CBPR funding. The project helped researchers to understand community-level factors that contribute to health through the eyes of youth in a process that inspired and motivated the participants.

After the Teen Photovoice Project, several participants have continued to develop their community advocacy interest through center-organized advocacy-related skill building activities, involvement in community organizations, and college classes that address this topic. The project gave participants an opportunity to consider social and environmental factors that influence their health. It gave them the chance to express their thoughts through images they photographed, discussions about their photographs, and, in a modification of traditional photovoice projects, through the products they produced from the photographs. Similar project adaptations could be studied to determine the full effect of such programs on participant-driven, community-based health promotion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the organizations that supported the youth in their participation: Aliso Pico Recreational Center—Prototypes Keeping It Real, Century Lift, Fulfillment Fund, Regional Occupational Program–Mayfair High School, and WLCAC–Delinquency Prevention & Intervention. We also thank Andrew Harris Kavanah of Imagebliss, who provided graphic design services to help the youth develop their posters, and Wen-Chih Yu for assistance with the manuscript.

Funded by UCLA Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48/DP000056).

youth participants Jon Amos, Brant Daniels, Megan Daniels, Christina Garcia, Karla Gonzalez, Kathy Hernandez, Heidi Holmes, Christian Potts, Jamilah Shabazz, Zondria Shipp, Jennifer Tae, Tulani Watkins, and La’Shield Williams.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clayton S, Brindis C, Hamor J, Raiden-Wright H, Fong C. Investing in adolescent health: A social imperative for California’s future. University of California, San Francisco; National Adolescent Health Information Center; San Francisco: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–87. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freire P. Education for critical consciousness. Seabury Press; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strack RW, Magill C, McDonagh K. Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:49–58. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C. Using Photovoice as a participatory assessment and issue selection tool: A case study with the homeless in Ann Arbor. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez E, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:99–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CC, Burris MA, Ping XY. Chinese Village women as visual anthropologists: Participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CC, Burris M. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:171–86. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich M, Lamola S, Woods ER. Effects of creating visual illness narratives on quality of life with asthma: a pilot intervention study. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:748–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich M. Showing and telling asthma children teaching physicians with visual narrative. Vol. 14. International Visual Sociology Association; 1999. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchbinder MH, Detzer MJ, Welsch RL, Christiano AS, Patashnick JL, Rich M. Assessing adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a multiple perspective pilot study using visual illness narratives and interviews. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CC, Morrel-Samuels S, Hutchison PM, Bell L, Pestronk RM. Flint Photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:911–13. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen L, Kane C. Research brief: Implementing a photovoice model with youth. New York State Center for School Safety; New Paltz: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau . Washington, DC: [cited 22 Feb 2006]. [homepage on the Internet] Available from: www.census.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weller S, Romney A. Systematic data collection. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell BH. Anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 3rd ed Altamira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2002. Research methods. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UCINET 6. Software for social network analysis, analytical technologies [computer program] Version 6 Analytic Technologies; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallerstein N. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas applied to youth. Youth Policy. 1987;9:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotler P, Roberto EL. Social marketing: Strategies for changing public behavior. Free Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21. [cited 8 Jan 2007];AskCHIS, The California Health Interview Survey [homepage on the Internet. Available from: www.chis. ucla.edu/main/default.asp.

- 22.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winett R. A framework for health promotion and disease prevention programs. Am Psychol. 1995;50:341–50. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.5.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montano D, Kasprzyk D, Taplin SH. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1997. pp. 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]