Abstract

Ewing Sarcoma (EWS) family of tumors is one of the most common tumors diagnosed in children and adolescents and is characterized by a translocation involving the EWS gene. Despite advances in chemotherapy, the prognosis of metastatic EWS is poor with an overall survival of less than 30% after 5 years. EWS tumor cells express the receptor tyrosine kinases, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and c-KIT. ABT-869 is a multi-targeted small molecule inhibitor that targets Fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT-3), c-KIT, vascular endothelial growth receptors (VEGFR) and PDGFRs. To determine the potential therapeutic benefit of ABT-869 in EWS cells, we examined the effects of ABT-869 on EWS cell lines and xenograft mouse models. ABT-869 inhibited the proliferation of two EWS cell lines, A4573 and TC71, at an IC50 of 1.25 μM and 2 μM after 72 hours of treatment, respectively. Phosphorylation of PDGFRβ, c-KIT, and ERKs was also inhibited. To examine the effects of ABT-869 in vivo, the drug was given to mice injected with EWS cells. We observed inhibition of growth of EWS tumor cells in a xenograft mouse model and prolonged survival in a metastatic mouse model of EWS. Therefore, our in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that ABT-869 inhibits proliferation of EWS cells through inhibition of PDGFRβ and c-KIT pathways.

Keywords: Ewing sarcoma, receptor tyrosine kinase, small molecule inhibitor, proliferation, signaling

Introduction

Ewing sarcoma (EWS) is the second most common primary bone tumor in childhood and is characterized by the EWS/FLI-1 translocation (1-4). Despite multimodal approaches to therapy, only 60% of patients with localized disease are cured. Approximately 30% of patients with metastatic disease have long-term survival beyond 5 years (5). The t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation is identified in over 95% of EWS tumors and results in the formation of the EWS/ETS fusion gene (6). Of these translocations, EWS/FLI-1 is the most common, consisting of over 85% of these aberrations. The EWS/FLI-1 fusion gene encodes for a transcription factor, which results in abnormal growth. Chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy are standard approaches to treat Ewing sarcoma, however, given the toxicities of treatment and poor prognosis of progressive disease, alternative modes of therapy are needed.

Several approaches have been used to target EWS cells for therapy. Since the EWS/ETS translocation is not expressed in normal cells and is unique to Ewing Sarcoma Family Tumors (ESFT), it provides an attractive target for therapy. Inhibition of EWS/FLI-1 by either antisense oligonucleotides or siRNAs has shown antitumor effects in vitro. However, due to the poor cellular penetration of siRNAs and susceptibility to degradation, their activity has not been successful in in vivo models (7). Antisense oligonucleotides encapsulated in nanocapsules have inhibited growth of tumors in a mouse xenograft model (8). Rapamycin has been shown to downregulate EWS/FLI-1 and inhibit cell growth in vitro (9), suggesting that inhibition of mTOR and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) are potential targets for therapy.

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ) is expressed on EWS cells, and its downstream signaling pathways are important for growth of tumor cells (10). The c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor pathway has also been shown to be critical for growth and progression in EWS (11). Previous studies demonstrate that both pathways are activated in ESFT (12) and are potential molecular targets. Autophosphorylation of c-KIT is inhibited by imatinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase-inhibitor, at an IC50 of 0.1-0.5 μM, while in vitro testing of cell lines showed that 50% growth inhibition required higher doses of imatinib at 10 μM (11, 13, 14). This suggests that the effect of imatinib on the growth of EWS cells was not exclusively mediated by c-KIT, but by other pathways (15).

ABT-869 is a multi-targeted small molecule inhibitor that binds the ATP binding site of several receptor tyrosine kinases, including FLT3, c-KIT, VEGFR1-3, and PDGFα and β receptor family members (16). Preclinical studies have demonstrated efficacy of ABT-869 in AML, human fibrosarcoma, breast, colon, and small-cell lung carcinoma xenograft models, as well as in orthotopic breast, prostate, and glioma models (17). In AML cell lines, ABT-869 was shown to inhibit phosphorylation of STAT5, ERK, KIT, and Pim-1 (16). The drug was also able to inhibit tumor growth in mouse xenograft models of two AML cell lines with daily oral administration. Given similar targets in EWS cells, we hypothesized that ABT-869 might be active against this tumor in vitro and in vivo.

In this paper, we report the effects of ABT-869 on EWS cell proliferation and signaling. The drug was tested in vitro and in vivo and was shown to inhibit proliferation of EWS cells. Both c-KIT and PDGFβ receptors, as well as downstream kinases were inhibited by ABT-869. Furthermore, treatment of EWS cells in xenograft models resulted in prolonged survival. Our results suggest that ABT-869 is active against EWS tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The EWS tumor cell lines, TC71 and A4573, were kindly provided by Timothy Triche, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles. The cells were cultured on collagen-coated tissue culture plates in DMEM medium (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 100U/mL penicillin, 100ug/mL streptomycin, 2mM L-Glutamine (Sigma, Inc., St Louis, MO), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Adherent monolayers were passaged every 3-5 days and grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

ABT-869 drug

ABT-869 is a receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Abbott Laboratories, Inc. Abbott Park, IL). For in vitro analysis, this compound was dissolved in DMSO at a 10mM concentration and aliquoted in desired working volumes of 20 μL and stored at -20°C. The drug was further diluted in DMSO and used at 1:1000 dilutions in cell culture experiments. For in vivo analysis, the compound was suspended in corn oil and administered by oral gavage at the dose of 40 mg/kg/day. This dose has shown to be well tolerated and sustain murine serum levels greater than 1 μM, 8 hours after the dose was given (16,17). The oral, once daily dosing regimen would be easier for patients and is currently being studied in adult clinical trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Proliferation studies

Dose response of the cell lines treated with ABT-869 was analyzed to determine the IC50. To determine the rate of proliferation, cell counts were analyzed by the trypan blue exclusion method on a Beckman-Coulter Vi-CELL XR. Cells were seeded at 1×105 cells/mL in triplicate in 1 ml on 24-well culture plates. The next day, the media was replaced and the cells were incubated with various concentrations of ABT-869 for 72 hours. Media was removed, cells were washed with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and trypsinized. The cells were washed off the plate with the culture medium and the entire sample was analyzed.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot analysis

Expression of PDGFRβ, c-KIT and their signaling pathways was determined by Western blot analysis. Both A4573 and TC71 cell lines were seeded at 1×105 cells/mL on 100 mm plates. The next day, the media was replaced and the cells incubated with the IC50 dose of ABT-869 for 72 hours. Prior to cell lysis, the cultures were treated with ligand for 10 minutes to induce phosphorylation of the receptor tyrosine kinases and to activate their signaling pathways. EWS cells were treated with recombinant human PDGF-BB (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) at 100 μM concentration or recombinant human Stem Cell Factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 100 μM concentration.

Cell lysates were obtained by washing the plates twice with 1× PBS, then freezing at -20°C. The plates were thawed on ice and 0.5 ml Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) Buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Igepal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing 1% Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma, Inc., St Louis, MO) and 1% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma, Inc., St Louis, MO) was added to plates and allowed to incubate on ice for about 10 minutes. The cells were scraped and an additional 0.2mL of RIPA buffer was added to wash the plates. The cells were sheared by passing the lysates through a 21-1/2-gauge then a 27-1/2-gauge syringe. The lysates were incubated, rotating, at 4°C for 30 minutes. The cells were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce Biotechnologies, Rockford, IL).

For immunoprecipitations, the Catch and Release v2.0 Kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Upstate, NY) was used as directed, loading 500 μg to 1 mg of whole cell lystate and 4 μg of specific primary antibody. The columns were incubated overnight at 4° C, on a rotator. The columns were spun down and the eluate was used for Western blot analysis. The bound proteins were eluted with 40μL denaturing elution buffer. Boiling Laemmli buffer (1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 0.5% Bromopehnol Blue, 50% Glycerol, 5% βME) was added to bring the total volume of eluted proteins to 60 μL. The immunoprecipitated samples were resolved on a 5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, incubated with specific antibodies, and visualized by chemiluminescence. Other proteins (50 μg/lane) were resolved on an 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE gel.

The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were c-KIT (MS-289, Thermo Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) and PDGFRβ (sc-432, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The antibodies used to characterize the phosphorylation status of PDGFRβ and KIT were c-KIT (A4502, Dako, Carpinteria, CA), phospho-c-KIT (ab5631, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), PDGFRβ (sc-432, SCBT, Santa Cruz, CA), and phospho-tyrosine (sc7020, SCBT, Santa Cruz, CA). The antibodies used to characterize the activation of the downstream signaling pathways were pan AKT, phospho-AKT(p-thr), p42/p44-MAPK, phospho-p42/p44-MAPK, GSK3β, phosphor-GSK3β. Unless otherwise noted, all antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc. (Danvers, MA).

Xenograft model of EWS in NOD/SCID mice

TC71-GFP/LUC and A4573-GFP/LUC cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS, antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin), and L-glutamine to a density of 75-90%. To prepare for injection, cells were trypsinized from the tissue culture plates and washed twice with PBS. Cells were counted and viability tested using the trypan-blue exclusion method. Immediately prior to injection, the cells were resuspended in serum-free, antibiotic-free medium. Only cells that were growing with a viability of >90% were used.

NOD/SCID mice were 6 to 8 weeks of age at the time of injection. Each mouse was injected with 5×106 TC71-GFP/LUC or A4573-GFP/LUC cells suspended in equal volume of DMEM (without FBS or antibiotics) and Matrigel, in 0.2 ml. The mixture was injected using a 28-1/2-guage needle subcutaneously, dorsally off the midline. The mice were treated in three separate experimental groups: ABT-869 treatment provided immediately, a delayed ABT-869 treatment group, and a group treated with corn oil vehicle control. The delayed group was initially given corn oil until the mice had a tumor volume of 300 mm3, then ABT-869 treatment was initiated. All mice were euthanized when the vehicle control mice reached a tumor volume of 2.5 cm3. Mice were treated according to the NIH Guidelines for Animal Care and as approved by the UCLA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Metastatic EWS model in NOD/SCID mice and bioluminescence imaging

TC71-GFP/LUC and A4573-GFP/LUC cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS, antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin), and L-glutamine. To prepare for injection, cells were trypsinized from the tissue culture plates and washed twice with PBS. Cells were counted and viability was tested using the trypan-blue exclusion method. Immediately prior to injection, the cells were resuspended in serum-free, antibiotic-free medium. Only cells >90% viable were used.

All NOD/SCID mice were 6 to 8 weeks of age at the time of injection. Each mouse was injected with 5×106 TC71-GFP/LUC or A4573-GFP/LUC cells suspended in 0.1 ml DMEM (without FBS or antibiotics) through the tail vein using a 28 1/2-gauge needle. All experimental manipulations with the mice were done under sterile conditions in a laminar flow hood. The mice were treated in two separate experimental groups: immediate ABT-869 and corn oil vehicle. Six mice per treatment group were analyzed.

After the injection of cells, the mice were imaged at various time points to ensure presence of disease using an in vivo IVIS 100 bioluminescence/optical imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). D-Luciferin (30 mg/ml) (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) dissolved in PBS was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 μl/mouse 15 minutes before measuring the light emission. General anesthesia was induced with 2.5% isofluorane and continued during the procedure with 2% isofluorane.

After acquiring photographic images of each mouse, luminescent images were acquired with various (5-60 seconds) exposure times. The resulting grayscale photographic and pseudocolor luminescent images were automatically superimposed by the IVIS Living Image (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) software to facilitate matching the observed luciferase signal with its location on the mouse.

Immunohistochemistry

All tumors were harvested from the mice. The tumor sections were fixed in formalin and submitted to UCLA Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine for sectioning and staining. The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and TUNEL antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Digital images of representative slides were taken.

Results

ABT-869 inhibits proliferation of EWS cells in vitro

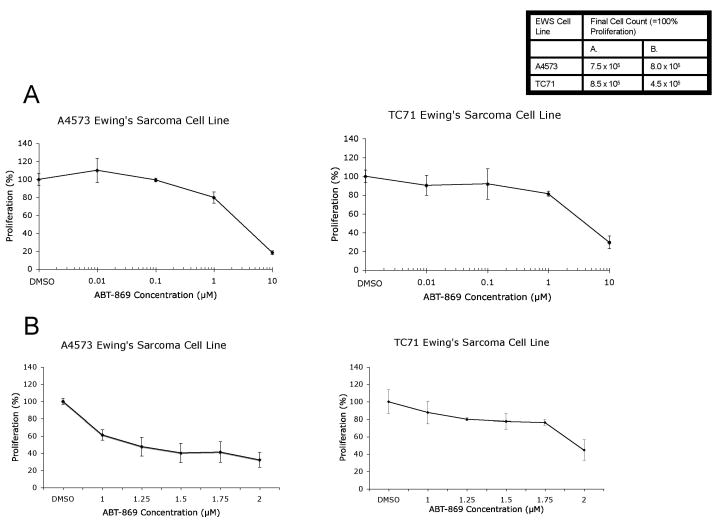

To assess the effects of ABT-869 on EWS cell growth, we analyzed two EWS cell lines, A4573 and TC71, after treatment at various concentrations of the drug from 10 nM to 10 μM by trypan blue exclusion method. Initial testing showed that the IC50 value for cellular proliferation for both A4573 and TC71 EWS cells were between 1 and 10 μM (Figure 1A). Further testing showed that ABT-869 significantly inhibited the growth of both EWS lines at concentrations between 1 and 2 μM after 72 hours of treatment. The IC50 value for cellular proliferation of the A4573 cells was 1.25 μM, while the TC71 cells was 2 μM (Figure 1B). Similarly, MTT assays confirmed that ABT-869 inhibited growth of both A4573 and TC71 cells at the same IC50 concentrations (data not shown).

Figure 1. ABT-869 inhibits growth of EWS cells.

A4573 or TC71 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Next day, the media was replaced and drug was added at concentrations ranging from (A) 0.01 to 10 μM or (B) 1 to 2 μM. After 72 hours, cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion method and proliferation was calculated relative to the vehicle control (shown as mean ± SD). The IC50 ± asymptotic SE of ABT-869 was estimated by inverse regression to be 1.25 ± 0.10 μM and 1.96± 0.04 μM for the A4573 and TC71 cell lines, respectively.

ABT-869 inhibits activation of the PDGFRβ and c-KIT signaling pathways

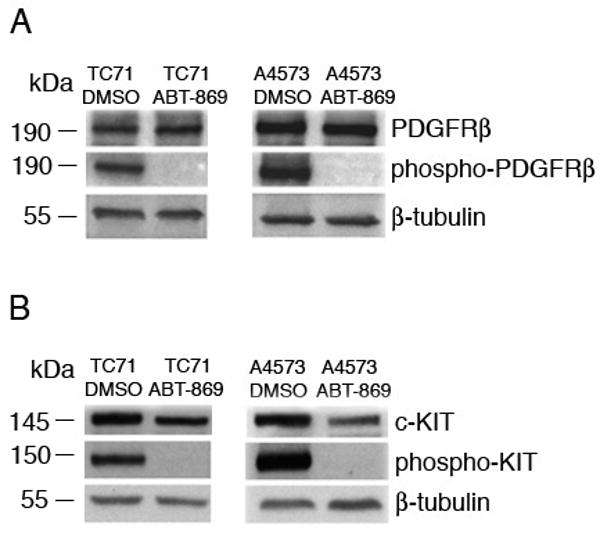

Previous studies demonstrated that EWS cell lines overexpress the receptor tyrosine kinases, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor β (PDGFRβ) and c-KIT (14). To determine whether inhibition of PDGFRβ and c-KIT pathways participate in the proliferation of EWS cells, we analyzed the activation of PDGFRβ and c-KIT after treatment of two human EWS cell lines, TC71 and A4573, with ABT-869. Immunoprecipitations were performed with PDGFRβ or c-KIT antibody. Treatment with the PDGFRβ ligand, PDGF-BB, at 100 μM concentration resulted in significant phosphorylation of PDGFRβ (Figure 2A) in both cell lines, but pretreatment for 72 hours with their respective IC50 concentrations of ABT-869 blocked PDGF-BB mediated PDGFRβ phosphorylation. Similarly, SCF-induced c-KIT phosphorylation was blocked by ABT-869 pretreatment in both cell lines (Figure 2B). We also examined cells that were not treated or stimulated with PDGF or c-KIT ligand and there was no difference compared to untreated and stimulated (data not shown). These results demonstrate that PDGFRβ and c-KIT activation are inhibited by ABT-869.

Figure 2. ABT-869 treatment of TC71 and A4573 EWS cells inhibits the phosphorylation of PDGFRβ and c-KIT receptor tyrosine kinases.

(A) TC71 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml and grown for three days in the presence or absence of ABT-869. Prior to lysis, cells were stimulated with PDGF-BB (100 μM) for 10 minutes. Immunoprecipitations were perform with anti-PDGFβ antibody. Pretreatment with ABT-869 completely inhibits the phosphorylation of PDGFRB, indicating that the drug inhibits activation of the receptor. (B) A4573 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Prior to lysis, cells were stimulated with SCF (100 μM) for 10 minutes. Immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-c-KIT antibody. Pretreatment with ABT-869 completely inhibits the phosphorylation of c-KIT. β-tubulin antisera were used as the internal loading control.

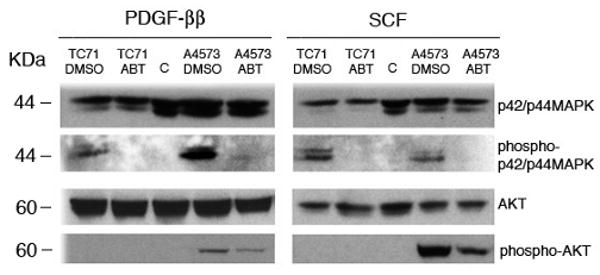

Activation of PDGFRβ and c-KIT initiates signaling pathways critical to cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and blood vessel maturation (10). Two critical pathways downstream of PDGFRβ and c-KIT include ERK and PI3K/AKT. Both pathways are controlled by several other receptor-tyrosine kinases, including IGFR and VEGFR2. To assess whether ABT-869 could inhibit the activation of ERK or AKT pathways downstream of PDGFRβ and c-KIT in EWS cells, we treated TC71 and A4573 cells with the ligands for PDGFRβ and c-KIT in the presence of the drug or vehicle control and performed Western blot analyses with phosphospecific antisera. ABT-869 inhibited activation of ERK in both the PDGF-BB and SCF stimulated lysates, while the phosphorylation of AKT was partially inhibited by drug treatment in A4573 cells (Figure 3). Our results suggest that ABT-869 treatment inhibits activation of p42/p44MAPK and in certain EWS cells, AKT.

Figure 3. ABT-869 treatment of TC71 and A4573 EWS cells inhibits the activation of p42/p44 MAPK/ERKs and AKT.

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml and media was replaced the following day. Cells were grown for three days in ABT-869. Prior to lysis, cells were stimulated with 100 μM of PDGF-BB (left) or SCF (right) for 10 minutes. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phosphorylated p42/p44 MAPK/ERK or AKT antibodies. The same blots were reprobed with unphosphorylated p42/p44MAPK/ERK or AKT antisera. Pretreatment with ABT-869 inhibited the activation of (A) p42/44 MAPK/ERK in both cells and (B) AKT in A4573 cells.

ABT-869 inhibits the growth and progression of EWS cells in vivo

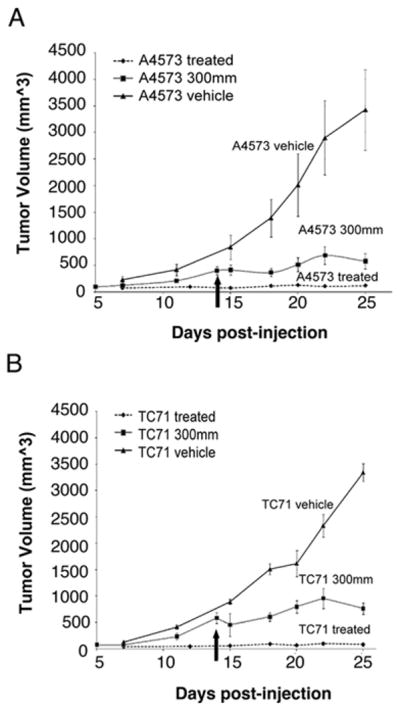

To determine whether the inhibition of PDGFRβ and c-KIT induced by ABT-869 inhibits tumor growth in vivo, NOD/SCID mice were inoculated subcutaneously with TC71 or A4573 cells. Mice were treated daily by oral gavage with either ABT-869 at 40 mg/kg or a corn oil vehicle control. The delayed treatment group received ABT-869 at 40 mg/kg/day when the tumors reached a volume of 300 mm3. Previous studies demonstrated that the drug does not affect normal organ function (17). We did not observe any signs of physical distress (lethargy, ruffled fur) or weight loss during the course of treatment with ABT-869 during our experiments (data not shown).

Treatment with ABT-869 directly after inoculation resulted in activity preventing tumor formation from injected cells. In previous experiments, treatment with the drug after significant tumor burden did not result in improved survival (data not shown). Therefore, this experiment was performed to assess the effects of drug in a setting of microscopic disease, before the onset of significant metastatic disease. One of the difficulties with eradicating EWS disease is that there are residual cells that are resistant to chemotherapy, which increase the risk of relapse. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited following delayed treatment of drug at 40 mg/kg/day (Figures 4A and B). Geometric mean tumor volumes at 25 days after injection with TC71 cells were 22% and 2.0% of vehicle control under delayed and immediate treatment, respectively (p<0.01 for delayed vs. immediate and for both comparisons to control volume). Similarly, geometric mean volumes using the A4573 cell line were 23% and 3.6% of control, respectively (p< 0.01 for all comparisons). By hematoxylin and eosin staining, the histology demonstrated that tumors from mice treated with ABT-869 had increased evidence of necrosis and inflammation compared to vehicle controls (Figures 5A and B). TUNEL staining showed increased apoptosis in the immediate and delayed treatment groups compared to the vehicle controls for both cell lines (Figures 5C and D). There were no differences in the cell cycle profile of cells treated with ABT-869 compared to vehicle control (data not shown). Therefore, ABT-869 is effective in suppressing growth and inducing cell death of EWS cells in vivo.

Figure 4. ABT-869 treatment in a xenograft model of EWS suppresses tumor growth in vivo.

Mean ± SE tumor volumes in SCID mice (3-5 per group) injected with 5 × 106 A4573 cells (A) or TC71 (B) in the flank with matrigel. Mice were given ABT-869 40 mg/kg/day orally every day. Mice gavaged with corn oil vehicle alone had a 28 to 50-fold greater tumor volume at 25 days compared to mice treated at the time of injection. In mice treated when tumor volume was 300 mm3 (see arrow), log linear tumor growth rates tended to be slower than control after the start of this delayed treatment.

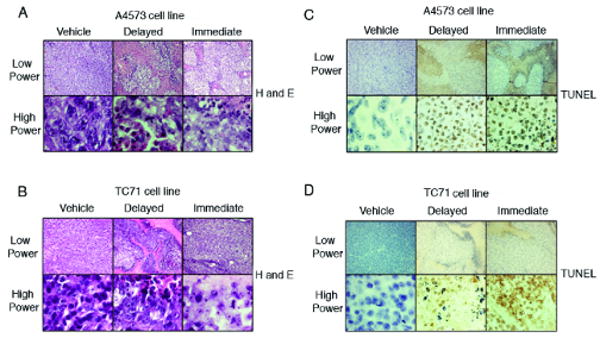

Figure 5. A4573 and TC71 EWS tumors stained for with H&E and TUNEL after ABT-869 treatment show increased necrosis.

Tumors from NOD/SCID mice were removed at the time that tumor volume of the vehicle controls reached the maximum allowed volume of 2.5 cm3. A4573 (A) and TC71 (B) tumors were smaller and the slides stained with H&E showed prominent areas of necrosis in the immediate (right) and delayed treatment groups (middle). TUNEL staining of A4573 (C) and TC71 (D) tumors showed increased apoptosis in the immediate (right) and delayed (middle) treated groups compared to the vehicle control groups (left). Upper rows are visualized at 10× magnification and the lower rows are at 100×. Experiments were repeated twice.

ABT-869 inhibits progression of tumor cells in a metastatic EWS model

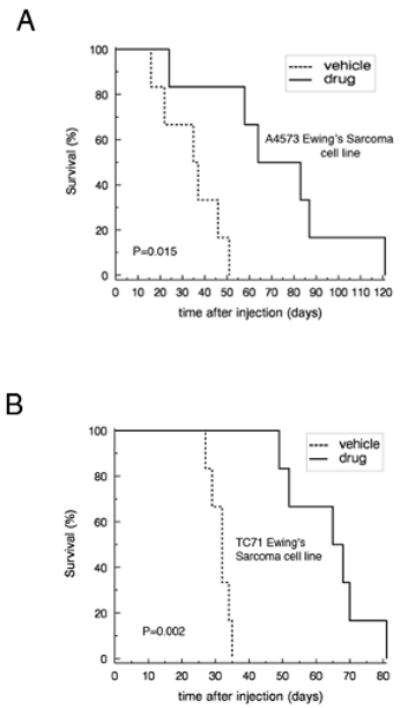

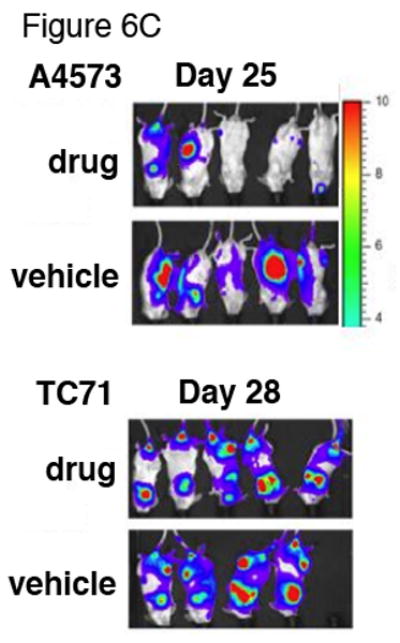

To analyze the potential effects of ABT-869 on a metastatic model of Ewing sarcoma, GFP/Luciferase-expressing A4573 and TC71 cells (A4573-GFP/LUC, TC71-GFP/LUC) were generated through lentiviral transduction followed by sorting for GFP. The sorted cells were cultured and injected through the tail vein into female NOD/SCID mice. Six mice were analyzed per treatment group. Engraftment and disease progression were monitored by acquiring in vivo bioluminescent images at least once per week. The mice began treatment the day after injection. Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated a survival benefit in the treatment group compared to the vehicle control group with both the A4573 GFP/LUC cell lines (p=0.015) (Figure 6A) and TC71-GFP/LUC (p=0.002) (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the tagged cells showed evidence of more aggressive disease in mice treated with ABT-869 compared to untreated mice (Figure 6C). As previously observed, the mice tolerated the ABT-869 well, maintained their normal activity levels and weight (16). These results suggest that survival is prolonged and disease progression is suppressed in mice treated with ABT-869.

Figure 6. Treatment of ABT-869 in vivo inhibits the metastatic progression of EWS cells in NOD/SCID mice and prolongs survival.

EWS cell lines A4573 and TC71 transduced with GFP and luciferase (5×106) were injected through the tail vein. Six mice per group were either treated with ABT-869 40 mg/kg/day or corn oil vehicle by daily gavage feeds. Metastatic disease was confirmed with bioluminescent imaging. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to analyze survival of mice injected with either A4573 (A) or TC71 (B) cells (5×106) treated with ABT-869 vs. control. Median survival for treated mice was 29 days and 33 days longer than control for A4573 (p=0.015 by logrank test) and TC71 (p=0.002), respectively. (C) EWS cell lines A4573 and TC71 transduced with GFP and luciferase (5×106) were injected through the tail vein and the mice were monitored with bioluminescent imaging at least once per week. The mice were either treated with ABT-869 40 mg/kg/day or corn oil vehicle by daily gavage feeds. The treated mice grossly showed slower progression of signal compared to vehicle control treated mice. Metastatic disease was confirmed with bioluminescent imaging.

Discussion

The use of a multimodal approach to the treatment of EWS has resulted in improved outcomes. However, patients with metastatic, relapsed, or resistant EWS continue to have poor prognoses. Therefore, improved therapeutic modalities are warranted. Previous work demonstrated that tyrosine kinases, c-KIT and PDGFRβ, are both expressed in EWS cells and are potentially important targets for therapy (10, 11). Both of these receptor tyrosine kinases and their downstream targets appear to be crucial for the growth of EWS tumors (10, 11). This is the first report that targeting c-KIT and PDGFRβ through a multi-targeted receptor tyrosine receptor kinase inhibitor is effective in suppressing the growth of EWS cells in vitro and in vivo.

We previously published that ABT-869 inhibited phosphorylation of constitutively active receptor tyrosine kinase, fms-like tyrosine kinase internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) in AML cells (16). In this paper, we show that a multi-targeted small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ABT-869, also inhibits the phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases in EWS cells and inhibits growth of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.

Previous reports have demonstrated inhibition of EWS cell proliferation by targeted therapies. Gefitinib and vandetanib are potent inhibitors of EGFR and VEGFR-2, respectively. When tested against the EWS cell line TC71, the IC50 was relatively high at 10 μM, compared to the nanomolar concentrations that inhibit EGFR and VEGFR-2 kinase activity in vitro (18). This suggests that the EGFR inhibition alone is most likely not sufficient to have an effect on the growth of EWS cells as a single agent. In the two cell lines that were tested, gefitinib and vandetanib did not inhibit phosphorylation of p42/44 MAPK (Erk 1/2) and AKT-1; nor did they affect levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc (18). In our studies, ABT-869 at low micromolar concentrations demonstrated decreased phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 in both the TC71 and A4573 cell lines and also showed decreased phosphorylation of AKT in the A4573 cell line. Given the higher IC50 of ABT-869 in EWS compared to in AML cells, our results suggest that the drug inhibits proliferation at least in part through suppressing activation of the PDGFβ and c-KIT receptors and their downstream targets. However, these pathways do not appear to be strong drivers of EWS cell proliferation. Additional pathways or kinases, such as VEGFR, involving angiogenesis, may be alternative mechanisms by which ABT-869 inhibits EWS cells in vivo (17). Imatinib, another receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to decrease autophosphorylation of c-KIT in vitro, but its effects on the growth of EWS cells required a dose that was much higher than ABT-869, with most cell lines requiring greater than 10 μM (11, 13, 14). This suggests that c-KIT inhibition alone is insufficient to provide a therapeutic effect in EWS.

Our results with xenograft models demonstrated that treatment with ABT-869 resulted in decreased tumor growth. The fact that ABT-869 is not a general antiproliferative drug, but rather inhibits both proliferation and induces cell death, is consistent with previous reports (17). Results using luciferase-tagged EWS cells suggest that ABT-869 prolongs survival and maintains stable disease. This may have clinical significant since survival of patients with metastatic EWS is poor despite multimodal chemotherapy. Thus, our data suggest that use of ABT-869 may be useful for patients with metastatic disease. However, we did observe a difference in the xenograft model compared to the metastatic model. This difference is most likely due to the greater tumor burden in the metastatic disease model. Very little toxicity was observed in mice, suggesting that this drug could be potentially used to treat patients with EWS. Previous studies demonstrated that imatinib sensitizes EWS cells to vincristine and doxorubicin (11). Future experiments will examine combined therapy with ABT-869 and chemotherapy or other small molecules that target additional signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: A.K.I. and N.F. are supported by NIH K12 award HD034610. A.K.I also received support by T32 CA09056. C.D. is supported by NIH grant CA087771. K.M.S. is supported by NIH grants HL75826, HL83077, American Cancer Society grant RSG-99-081-01-LIB, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Grant, and a grant from Abbott Laboratories, Inc. K.M.S. is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Abbreviation list

- EWS

Ewing sarcoma

- PDGF

platelet derived growth factor

- FLT

Fms-like tyrosine kinase

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- ESFT

Ewing sarcoma family of tumors

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

References

- 1.Arvand A, Denny CT. Biology of EWS/ETS fusions in Ewing's family tumors. Oncogene. 2001;20(40):5747–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denny C. Defining small round cell tumors of childhood: when is a rose really a rose. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(6):338–9. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potikyan G, France KA, Carlson MR, Dong J, Nelson SF, Denny CT. Genetically defined EWS/FLI1 model system suggests mesenchymal origin of Ewing's family tumors. Lab Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potikyan G, Savene RO, Gaulden JM, et al. EWS/FLI1 regulates tumor angiogenesis in Ewing's sarcoma via suppression of thrombospondins. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6675–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Liu T, Krasin MJ, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors in ewing sarcoma family of tumors: review of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital studies. Cancer. 2007;110(2):375–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Ewing's sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(2):79–89. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kontny U. Regulation of apoptosis and proliferation in Ewing's sarcoma--opportunities for targeted therapy. Hematol Oncol. 2006;24(1):14–21. doi: 10.1002/hon.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert G, Bertrand JR, Fattal E, et al. EWS fli-1 antisense nanocapsules inhibits ewing sarcoma-related tumor in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279(2):401–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uren A, Tcherkasskaya O, Toretsky JA. Recombinant EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein activates transcription. Biochemistry. 2004;43(42):13579–89. doi: 10.1021/bi048776q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uren A, Merchant MS, Sun CJ, et al. Beta-platelet-derived growth factor receptor mediates motility and growth of Ewing's sarcoma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(15):2334–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez I, Andreu EJ, Panizo A, et al. Imatinib inhibits proliferation of Ewing tumor cells mediated by the stem cell factor/KIT receptor pathway, and sensitizes cells to vincristine and doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(2):751–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0778-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozzi F, Tamborini E, Negri T, et al. Evidence for activation of KIT, PDGFRalpha, and PDGFRbeta receptors in the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1638–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotfilder M, Lanvers C, Jurgens H, Boos J, Vormoor J. c-KIT-expressing Ewing tumour cells are insensitive to imatinib mesylate (STI571) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;50(2):167–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant MS, Woo CW, Mackall CL, Thiele CJ. Potential use of imatinib in Ewing's Sarcoma: evidence for in vitro and in vivo activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(22):1673–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druker BJ. Taking aim at Ewing's sarcoma: is KIT a target and will imatinib work? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(22):1660–1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shankar DB, Li J, Tapang P, et al. ABT-869, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation and signaling in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(8):3400–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albert DH, Tapang P, Magoc TJ, et al. Preclinical activity of ABT-869, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(4):995–1006. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson MK, Aman P. Proliferation of Ewing sarcoma cell lines is suppressed by the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors gefitinib and vandetanib. Cancer Cell Int. 2008;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]