Abstract

Background

The obesity epidemic is a major health problem in the US. Alcohol consumption is a source of energy intake that may contribute to body weight gain and development of obesity. However, previous studies on this relation have been limited and inconsistent.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study among 19,220 US women aged ≥39 years, free of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes, and having a normal baseline body mass index (BMI) of 18.5-<25 kg/m2. Alcoholic beverage consumption was reported on a baseline questionnaire. Body weight was self-reported on baseline and eight annual follow-up questionnaires.

Results

There was an inverse association between amount of alcohol consumed at baseline and weight gained over 12.9 years of follow-up. A total of 7,942 initially normal-weight women became overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) and 732 became obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). After adjusting for age, baseline BMI, smoking status, non-alcohol energy intake, physical activity, and other lifestyle and dietary factors, the relative risks (RRs) of becoming overweight or obese across total alcohol intake of 0, >0-<5, 5-<15, 15-<30, and ≥30 g/day were 1.00, 0.96, 0.86, 0.70, and 0.73, respectively (Ptrend <0.0001). The corresponding RRs of becoming obese were 1.00, 0.75, 0.43, 0.39, and 0.29 (Ptrend <0.0001). The associations were consistent by subgroups of age, smoking status, physical activity, and baseline BMI.

Conclusion

Compared with non-drinkers, initially normal-weight women that consumed light-to-moderate amount of alcohol experienced smaller weight gain and lower risk of becoming overweight and/or obese during 12.9 years of follow-up.

Introduction

Obesity is a well-established modifiable risk factor for many chronic diseases, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.1, 2 The increase in prevalence of overweight (defined as body mass index or BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) in the US was noted as early as 1960,2 and continued at least till 1999.3 A survey conducted in 1999–2000 as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that nearly two thirds of US adults have a BMI ≥25 kg/m2,3 which highlights an ongoing obesity epidemic. Balancing energy intake and energy expenditure for the prevention of obesity is of major public health importance in the US population.

More than half of American adults consume alcoholic beverages.4 Alcohol, with a caloric value of 7.1 kcal/g, represents a nontrivial energy source that may contribute to a positive energy balance and in the long-term result in weight gain and the development of obesity.5 However, epidemiologic studies have not provided consistent evidence for alcohol consumption as a risk factor for obesity. Cross-sectional studies have reported associations between alcohol intake and body weight to be positive6–9 or null10–14 in men and inverse7, 10–13, 15 or null6, 16 in women. Few prospective cohort studies have examined alcohol consumption and long-term change in body weight, and the results are conflicting, with both positive16, 17 and null18, 19 associations found in men and positive,16 inverse,19 and null18, 20 associations found in women. Although overweight and obesity are widely recognized as adverse clinical profiles, no previous studies to our knowledge have specifically investigated the risk of becoming overweight or obese among initially normal-weight individuals. We therefore examined the prospective association of alcohol consumption with weight gain and risk of becoming overweight or obese in a cohort of middle-aged and older US women during 12.9 years of follow-up.

Methods

Study Population

The Women’s Health Study (WHS) was a randomized clinical trial evaluating the effects of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer.21–23 A third component, β-carotene, was initially included but terminated after a median treatment of 2.1 years.24 Blinded treatment with aspirin and vitamin E ended as scheduled on March 31, 2004, while observational follow-up of the WHS cohort continues. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was approved by the institutional review board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. From September 1992 to May 1995, 39,876 female US health professionals aged from 38.9 to 89.0 years and free of cardiovascular disease and cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) were randomized into WHS. Of the 39,876 women randomized, 19,563 women who reported a BMI ranging from 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 at baseline were included in the current study. We further excluded 5 women with missing data on baseline alcohol intake, 128 women with no updated body weight during the entire follow-up, 194 women with baseline diabetes, and 17 women with pre-randomization cardiovascular disease or cancer. As a result of these partially overlapping exclusions, a baseline population of 19,220 women remained for analysis.

Assessment of Alcohol Intake

On baseline questionnaire, participants were asked how often on average they had consumed alcoholic beverages, including beer (1 glass, bottle, or can), red wine (4-oz. glass), white wine (4-oz. glass), and liquor (one drink or shot), during the previous year. Nine possible responses ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “6+ per day” were recorded. Alcohol intake was calculated according to the alcohol content in each beverage, assuming ethanol of 13.2 g for 360 ml (12 ounces) beer, 10.8 g for 120 ml (4 oz.) red or white wine, and 15.1 g for 45 ml (1.5 oz.) liquor. Among health professionals similar to the WHS cohort, the correlation of alcohol intake estimated from diet records and questionnaires was 0.90 for total alcohol intake,25 0.81 for beer, 0.83 for wine, and 0.80 for liquor intake.26

Other Baseline Variables

Women in the WHS reportedage, smoking status, physical activity, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use, multivitamin use, and history of diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia on the baseline questionnaire. A total of 39,310 of the 39,876 randomized participants completed a 131-item validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (SFFQ). A commonly used unit or portion size was specified for each food item, and participants reported how often they had consumed that amount, on average, during the previous year. Nutrient intake was computed by multiplying the intake frequency of each unit of food by the nutrient content of the specified portion size according to food composition tables from the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.15 Intake of each nutrient reported in the current study was adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method.16 The SFFQ used in the WHS has demonstrated reasonable validity and reproducibility as a measure of long-term average dietary intake.17

Ascertainment of Body Weight Change and Incident Overweight and/or Obesity

WHS participants reported height and weight on the baseline questionnaire. Information on body weight was updated on the annual follow-up questionnaires during the trial period (referred to as the 2-, 3-, 5-, 6-, and 9-year follow-up questionnaires). After the end of the WHS intervention, 16,322 of the 19,220 women with normal BMI at baseline agreed to continue in the observational follow-up and updated body weight on the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd observational follow-up questionnaires (referred to as the 11-, 12-, and 13-year follow-up questionnaires). BMIs were then calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m) using the self-reported information at baseline and a total of 8 follow-up time points, each classified mutual-exclusively to normal (18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2), or obese (≥30 kg/m2) according to the criterion by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.2 Incident cases of becoming overweight or obese were defined as women that had a normal BMIat baseline and subsequently reported a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 at any follow-up time point. For each case that became overweight or obese, the ‘time-of-event’ was calculated as the estimated time when her BMI crossed the cutoff (i.e. 25 kg/m2) by modeling a regression line from the last reported BMI of <25 kg/m2 to the first reported BMI of ≥25 kg/m2 over follow-up time. For women who did not become overweight or obese, the ‘time-of-censoring’ was calculated as the latest date when a BMI of <25 kg/m2 was reported. Incident cases of becoming obese were defined in a similar manner using BMI ≥30 kg/m2 as the cutoff. Women who developed intermediate diabetes, the management of which typically involves weight control, were censored on the date of the diabetes diagnosis. In similar populations of female health professionals, self-reported weights were highly correlated with clinic-measured weights (Pearson r=0.97).27 Studies in adults across different populations also have found that self-reported overweight and obesity status are accurate.28–30

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) version 9.1. Total alcohol intake was divided into predetermined categories of 0, >0- <5, 5-<15, 15-<30, and ≥30 g/day. Potential confounders were identified by comparing demographic, lifestyle, clinical, and dietary factors across levels of total alcohol intake. Weight change from baseline to follow-up was calculated at each follow-up time point and compared across categories of baseline alcohol intake using analysis of covariance. Out of concern that body weight composition and weight change pattern may be modified by aging process, we also conducted stratified analyses by baseline age. Cox models were then used to assess the association between alcohol intake and the risk of becoming overweight or obese. The hazard ratio, presented as relative risk (RR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated across categories of total alcohol intake, with non-drinkers as the reference. The independent associations for each type of alcoholic beverage (beer, red wine, white wine, and liquor) were determined by including the four beverage types simultaneously in a single model. Same analyses were repeated for the risk of becoming obese. All models first adjusted only for age, followed by multivariate adjustment for race, baseline BMI, randomized treatment, non-alcohol energy intake, physical activity, smoking habits, post-menopausal status, post-menopausal hormone use, multivitamin use, history of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, and dietary factors including intake of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, red meats and poultry, low-fat dairy products, high-fat dairy products, energy-adjusted total fat, carbohydrates, and fiber. Linear trends across increasing alcohol intake were tested using the median value of each alcohol intake category as an ordinal variable. Curvilinear trends were tested by including the quadratic term of continuous alcohol intake in the model. Women who consumed alcohol ≥40 g/day were also examined separately. Effect modifications were tested for baseline age, BMI, smoking status, and physical activity.

Results

Among 19,220 middle-aged and older women that reported a baseline BMI 18.5-<25 kg/m2, 7,346 (38.2%) did not consume alcohol and 568 (3%) consumed alcohol ≥30 g/day. Compared to non-drinkers, women who consumed greater amount of alcohol were significantly older, more likely to be white, current smokers, postmenopausal, and hypertensive, and had slightly lower baseline BMI (Table 1). Total energy intake significantly increased with increasing alcohol intake, while energy intake excluding the calories from alcohol decreased with alcohol intake. Energy expenditure through leisure-time physical activity had a U-shaped relation with alcohol consumption, with women who consumed intermediate amounts of alcohol having the highest level of physical activity. With regard to the dietary factors, alcohol intake was positively associated with intake of red meat, poultry, and high-fat dairy products; inversely associated with intake of whole grains, refined grains, low-fat dairy products, total and subgroup of fats, carbohydrates, and fiber; and unassociated with fruit, vegetable, and protein intake.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics† of 19,220 women who had body mass index 18.5 to <25 Kg/m2

| Total Alcohol Intake (g/day) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | >0-<5 | 5-<15 | 15-<30 | ≥30 | P‡ | |

| Median (g/day) | 0 | 1.73 | 8.64 | 19.4 | 38.6 | |

| N | 7346 | 6312 | 3865 | 1129 | 568 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (y) | 54.9±7.4 | 53.8±6.7 | 54.1±6.9 | 55.6±7.4 | 56.6±7.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Race of white (%) | 92.9 | 96.6 | 98.0 | 98.1 | 98.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Baseline BMI (Kg/m2) | 22.5±1.6 | 22.5±1.6 | 22.3±1.6 | 22.3±1.6 | 22.3±1.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Energy Intake and Expenditure | ||||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1670±528 | 1710±513 | 1723±499 | 1738±499 | 1788±521 | < 0.0001 |

| Non-alcohol energy intake (kcal/day) | 1670±528 | 1696±513 | 1659±499 | 1589±501 | 1493±519 | < 0.0001 |

| Physical activity (kcal/week) | 920±1143 | 1065±1183 | 1162±1269 | 1101±1244 | 930±1290 | 0.0007 |

| Behavior | ||||||

| Current smoking (%) | 13.8 | 12.0 | 13.7 | 16.5 | 33.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Postmenopausal (%) | 56.6 | 50.3 | 52.0 | 56.8 | 65.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Current postmenopausal hormone use (%) | 43.0 | 44.7 | 44.0 | 48.1 | 42.0 | 0.01 |

| Current multivitamin use (%) | 31.1 | 31.4 | 29.8 | 30.8 | 31.0 | 0.53 |

| Clinical | ||||||

| History of hypercholesterolemia (%) | 27.4 | 23.5 | 22.5 | 25.5 | 28.5 | < 0.0001 |

| History of hypertension (%) | 16.5 | 14.5 | 15.1 | 20.4 | 24.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Food Intake | ||||||

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/day) | 6.1±4.1 | 6.2±3.3 | 6.3±3.1 | 6.3±3.2 | 5.8±3.3 | 0.96 |

| Whole grains (servings/day) | 1.5±1.3 | 1.4±1.2 | 1.4±1.2 | 1.3±1.1 | 1.2±1.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Refined grains (servings/day) | 2.2±1.5 | 2.2±1.4 | 2.1±1.4 | 2.0±1.3 | 1.8±1.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Red meats and poultry (servings/day) | 1.1±0.7 | 1.1±0.6 | 1.1±0.6 | 1.1±0.6 | 1.2±0.7 | 0.0002 |

| Low-Fat dairy products (servings/day) | 1.2±1.1 | 1.3±1.1 | 1.2±1.0 | 1.0±0.9 | 0.9±0.9 | < 0.0001 |

| High-Fat dairy products (servings/day) | 0.7±0.9 | 0.7±0.9 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.8±1.0 | 0.8±1.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Nutrients Intake¶ | ||||||

| Total fat (g/day) | 56.7±12.4 | 56.5±11.4 | 55.6±11.1 | 55.5±11.0 | 54.6±12.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Saturated fat (g/day) | 19.3±5.2 | 19.2±4.7 | 18.8±4.6 | 18.7±4.6 | 18.5±5.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g/day) | 21.1±5.3 | 21.0±4.9 | 20.8±4.8 | 20.8±4.7 | 20.6±5.2 | 0.002 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g/day) | 11.0±2.9 | 11.0±2.8 | 10.8±2.7 | 10.8±2.9 | 10.4±2.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Carbohydrates (g/day) | 226±80 | 226±76 | 217±74 | 204±71 | 193±70 | < 0.0001 |

| Protein (g/day) | 77.1±27.1 | 79.8±25.5 | 79.5±24.7 | 78.4±24.5 | 76.6±25.6 | 0.97 |

| Fiber (g/day) | 19.2±8.8 | 19.2±7.9 | 19.0±7.9 | 18.3±7.5 | 16.8±7.3 | < 0.0001 |

Values shown were means±Standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

P for trend test of continuous variables and for χ2 of categorical variables.

Energy adjusted using residual method.

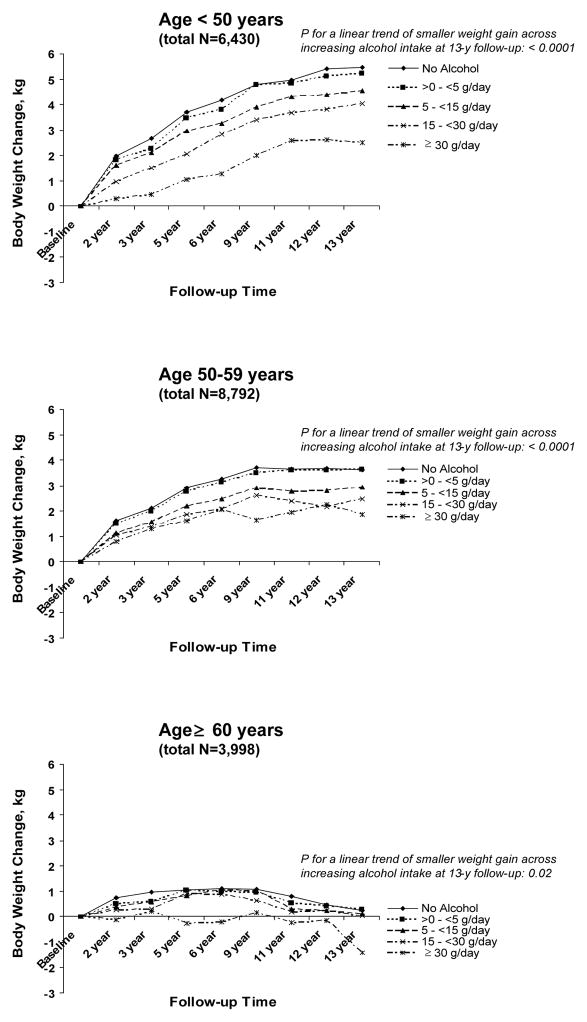

During 12.9 years of follow-up, women on average gained weight progressively (Table 2). Throughout the entire follow-up, the age-adjusted weight gain was the largest for women who did not consume alcohol, and then monotonously decreased with increasing total alcohol intake (Ptrend <0.0001 at all time points). This relation became even stronger after adjusting for race, baseline weight, non-alcohol energy intake, physical activity, smoking habits, and other lifestyle and dietary factors. The multivariate-adjusted mean weight gain over 13 years of follow-up was 3.63 (95%CI: 3.45–3.80) kg for women who did not consume alcohol in comparison with 1.55 (95%CI: 0.93–2.18) kg for those who consumed alcohol ≥30 g/day. When women who consumed alcohol ≥40 g/day were compared to those consuming 30–40 g/day, however, the weight gains were similar (data not shown). In analyses stratified by baseline age (Figure 1), a trend for decreasing weight gain with increasing total alcohol intake was consistently observed among women aged <50, 50-<60, and ≥60 years old, though the magnitude of weight gain was smaller in older versus in younger women.

Table 2.

Adjusted mean body weight change (in kg) during 13-year follow-up according to baseline total alcohol intake

| Total Alcohol Intake (g/day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Duration | N | 0 | >0-<5 | 5-<15 | 15-<30 | ≥30 | P† linear |

| 2 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 18998 | 1.49 | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 0.77 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 17955 | 1.55 | 1.41 | 1.14 | 0.89 | 0.51 | < 0.0001 |

| 3 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 18096 | 1.97 | 1.79 | 1.64 | 1.46 | 1.26 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 17118 | 2.05 | 1.81 | 1.53 | 1.22 | 0.95 | < 0.0001 |

| 5 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 18065 | 2.68 | 2.61 | 2.26 | 2.11 | 1.61 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 17105 | 2.77 | 2.65 | 2.16 | 1.78 | 1.16 | < 0.0001 |

| 6 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 17775 | 2.99 | 2.88 | 2.54 | 2.38 | 1.93 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 16820 | 3.10 | 2.92 | 2.42 | 2.11 | 1.47 | < 0.0001 |

| 9 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 15341 | 3.44 | 3.35 | 2.94 | 2.74 | 2.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 14576 | 3.52 | 3.40 | 2.83 | 2.50 | 1.57 | < 0.0001 |

| 11 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 16322 | 3.47 | 3.39 | 2.91 | 2.65 | 2.31 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 15481 | 3.55 | 3.46 | 2.81 | 2.40 | 1.83 | < 0.0001 |

| 12 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 15992 | 3.57 | 3.48 | 2.97 | 2.63 | 2.41 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 15178 | 3.67 | 3.53 | 2.86 | 2.37 | 2.02 | < 0.0001 |

| 13 year | |||||||

| Age adjusted | 15634 | 3.53 | 3.50 | 3.05 | 2.87 | 2.09 | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted‡ | 14849 | 3.63 | 3.56 | 2.95 | 2.56 | 1.55 | < 0.0001 |

Linear trends were tested using the median value of each alcohol intake category as an ordinal variable.

Multivariate model additionally adjusted for race (white, non-white), baseline weight (continuous), randomized treatment (vitamin E, aspirin, β-carotene, or placebo), non-alcohol energy intake (continuous), physical activity (<200, 200-<600, 600-<1500, ≥1500 kcal/wk), smoking (never, former, current), post-menopausal status (yes, no, uncertain), post-menopausal hormone use (never, former, current), multivitamin use (never, former, current), history of hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and hypertension (yes, no), intake of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, red meats and poultry, low-fat dairy products, high-fat dairy products, energy-adjusted total fat, carbohydrates, and fiber (all in quintiles).

Figure 1.

Multivariate adjusted mean body weight change (in kg) during 13-year follow-up according to baseline total alcohol intake, stratified by baseline age groups. Model adjusted for age, race, baseline weight, randomized treatment, total non-alcohol energy intake, physical activity, smoking status, post-menopausal status, post-menopausal hormone use, multivitamin use, history of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, intake of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, red meats and poultry, low-fat dairy products, high-fat dairy products, energy-adjusted total fat, carbohydrates, and fiber. P for a linear trend of body weight change across levels of total alcohol intake was tested using the median value of each alcohol intake category as an ordinal variable.

Of the 19,220 women with normal weight at baseline, 7,942 (41.3%) became overweight or obese during 12.9 years of follow-up. Compared with non-drinkers, women who consumed alcohol >0-<5, 5-<15, 15-<30, and ≥30 g/day had age-adjusted RRs of 0.96, 0.84, 0.73, and 0.78, respectively, for becoming overweight or obese (Table 3). The risk of becoming overweight or obese for women consuming alcohol ≥40 g/day (age-adjusted RR=0.90, 95%CI: 0.71–1.13) was not further reduced. These RRs changed little after multivariate adjustment. An inverse association between alcohol intake and risk of becoming overweight or obese was noted for all four types of alcoholic beverages, with the strongest association found for red wine and a weak yet significant association for white wine after multivariate adjustment. Using BMI ≥30 kg/m2 as the cutoff, 732 (3.8%) of the 19,220 initially normal-weight women became obese over 12.9 years of follow-up. The multivariate RRs for becoming obese across increasing total alcohol intake >0-<5, 5-<15, 15-<30, and ≥30 g/day were 0.75, 0.43, 0.39, and 0.29, respectively. The inverse associations with risk of becoming obese were also statistically significant for all four alcoholic beverage types in multivariate model.

Table 3.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals of becoming overweight and/or obese across alcohol intake

| Incident Overweight or Obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) |

Incident Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | N | RR (95%CI) | N | RR (95%CI) | |||

| Age adjusted | Multivariate† Adjusted | Age adjusted | Multivariate† Adjusted | ||||

| All alcohol | |||||||

| No Alcohol | 7346 | 3150 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 337 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| >0-<5 g/day | 6312 | 2721 | 0.96 (0.91 – 1.01) | 0.96 (0.91 – 1.01) | 250 | 0.79 (0.67 – 0.93) | 0.75 (0.63 – 0.89) |

| 5-<15 g/day | 3865 | 1500 | 0.84 (0.79 – 0.89) | 0.86 (0.80 – 0.92) | 104 | 0.55 (0.44 – 0.68) | 0.43 (0.34 – 0.56) |

| 15-<30 g/day | 1129 | 376 | 0.73 (0.65 – 0.81) | 0.70 (0.62 – 0.79) | 28 | 0.55 (0.38 – 0.81) | 0.39 (0.25 – 0.60) |

| ≥30 g/day | 568 | 195 | 0.78 (0.67 – 0.90) | 0.73 (0.62 – 0.85) | 13 | 0.55 (0.32 – 0.96) | 0.29 (0.15 – 0.54) |

| P‡, linear | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||

| P¶, curvilinear | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Beer | |||||||

| Rarely/Never | 14638 | 6143 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 595 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1–4 drink/m | 2969 | 1184 | 0.94 (0.87 – 1.00) | 0.93 (0.87 – 1.00) | 87 | 0.77 (0.60 – 0.97) | 0.74 (0.57 – 0.95) |

| 2–6 drink/wk | 941 | 362 | 0.89 (0.79 – 0.99) | 0.86 (0.76 – 0.97) | 28 | 0.79 (0.54 – 1.17) | 0.65 (0.42 – 0.99) |

| ≥1 drink/d | 298 | 118 | 0.92 (0.75 – 1.12) | 0.76 (0.62 – 0.94) | 13 | 1.11 (0.63 – 1.97) | 0.63 (0.34 – 1.18) |

| P‡, linear | 0.04 | 0.0004 | 0.37 | 0.02 | |||

| P¶, curvilinear | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.007 | |||

| Red Wine | |||||||

| Rarely/Never | 14043 | 5980 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 598 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1–4 drink/m | 3328 | 1304 | 0.90 (0.84 – 0.96) | 0.95 (0.89 – 1.02) | 92 | 0.70 (0.55 – 0.89) | 0.75 (0.59 – 0.97) |

| 2–6 drink/wk | 1026 | 369 | 0.83 (0.74 – 0.93) | 0.89 (0.79 – 1.00) | 25 | 0.66 (0.43 – 1.01) | 0.63 (0.40 – 0.98) |

| ≥1 drink/d | 292 | 88 | 0.65 (0.51 – 0.82) | 0.66 (0.52 – 0.84) | 5 | 0.52 (0.22 – 1.26) | 0.47 (0.19 – 1.14) |

| P‡, linear | < 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | |||

| P¶, curvilinear | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.25 | |||

| White Wine | |||||||

| Rarely/Never | 10117 | 4315 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 431 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1–4 drink/m | 5678 | 2364 | 0.96 (0.91 – 1.01) | 1.00 (0.94 – 1.06) | 210 | 0.92 (0.77 – 1.11) | 0.93 (0.77 – 1.13) |

| 2–6 drink/wk | 2269 | 845 | 0.85 (0.78 – 0.92) | 0.91 (0.84 – 0.99) | 64 | 0.74 (0.56 – 0.99) | 0.71 (0.52 – 0.96) |

| ≥1 drink/d | 807 | 268 | 0.76 (0.67 – 0.87) | 0.88 (0.77 – 1.02) | 16 | 0.58 (0.35 – 0.95) | 0.41 (0.22 – 0.74) |

| P‡, linear | < 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | |||

| P¶, curvilinear | < 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.09 | |||

| Liquor | |||||||

| Rarely/Never | 13409 | 5559 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 533 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1–4 drink/m | 3542 | 1545 | 1.12 (1.05 – 1.19) | 1.01 (0.95 – 1.07) | 142 | 1.17 (0.96 – 1.43) | 1.04 (0.84 – 1.28) |

| 2–6 drink/wk | 1330 | 518 | 1.03 (0.94 – 1.14) | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.06) | 37 | 0.90 (0.63 – 1.28) | 0.73 (0.50 – 1.06) |

| ≥1 drink/d | 620 | 198 | 0.88 (0.76 – 1.03) | 0.76 (0.65 – 0.90) | 10 | 0.66 (0.34 – 1.28) | 0.38 (0.17 – 0.81) |

| P‡, linear | 0.87 | 0.008 | 0.26 | 0.005 | |||

| P¶, curvilinear | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.87 | |||

Multivariate model additionally adjusted for race (white, non-white), baseline BMI (continuous), randomized treatment (vitamin E, aspirin, β-carotene, or placebo), total non-alcohol energy intake (continuous), physical activity (<200, 200-<600, 600-<1500, ≥1500 kcal/wk), smoking (never, former, current), post-menopausal status (yes, no, uncertain), post-menopausal hormone use (never, former, current), multivitamin use (never, former, current), history of hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and hypertension (yes, no), intake of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, red meats and poultry, low-fat dairy products, high-fat dairy products, energy-adjusted total fat, carbohydrates, and fiber (all in quintiles).

Linear trends were tested using the median value of each alcohol intake category as an ordinal variable.

Curvilinear trends were tested by including the quadratic term of continuous alcohol intake in the model.

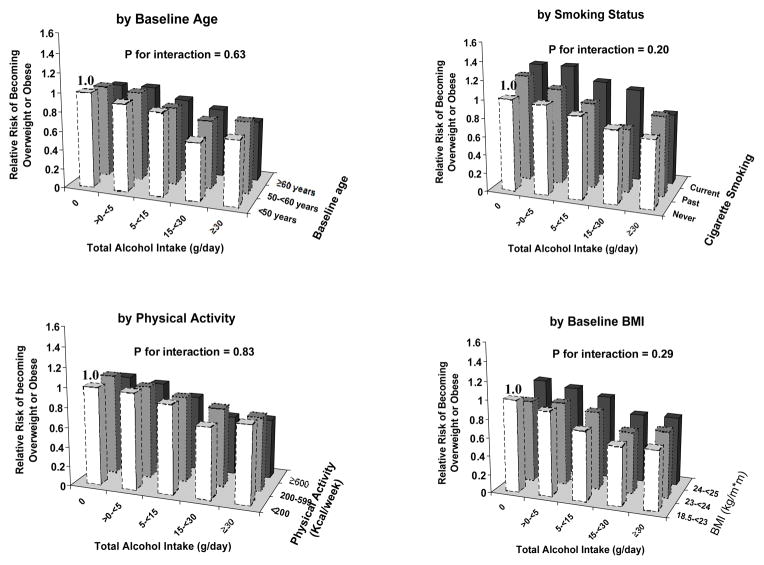

The inverse association between total alcohol intake and risk of becoming overweight or obese did not substantially differ by subgroups of women (Figure 2). Compared with women who did not consume alcohol and were <50 years old, the RRs of becoming overweight or obese across increasing total alcohol intake decreased from 1.00 (reference) to 0.68 (95% CI: 0.51–0.90) among women aged <50 years, from 0.94 (95%CI: 0.85–1.04) to 0.75 (95%CI: 0.59–0.93) among women aged 50-<60 years, and from 0.90 (95% CI: 0.74–1.09) to 0.63 (95%CI: 0.43–0.91) among women aged ≥60 years. The reduction in risk of becoming overweight or obese with increasing total alcohol intake was also similar by stratum of smoking, physical activity, and baseline BMI (all p for interaction >0.05).

Figure 2.

Relative risks of becoming overweight or obese according to baseline alcohol intake in subgroups of women. Model adjusted for age, race, baseline BMI, randomized treatment, non-alcohol energy intake, physical activity, smoking status, post-menopausal status, post-menopausal hormone use, multivitamin use, history of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, intake of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, red meats and poultry, low-fat dairy products, high-fat dairy products, energy-adjusted total fat, carbohydrates, and fiber. Interaction was examined using Wald chi-square test.

Several secondary analyses were performed. First, we additionally adjusted for consumption of other beverages including varieties of coffee, soft drinks, and tea. Second, we excluded women who smoked or had history of hypertension or hypercholesterolemia at baseline. Third, we censored women when they developed intermediate chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancer during follow-up. Fourth, we restricted the analyses to 12,132 women who returned all follow-up questionnaires and updated body weight on each questionnaire during the entire follow-up. Finally, we updated alcohol intake at the 48-month and 108-month follow-up using a time-dependent variable. The overall results did not materially change in any of these secondary analyses and therefore are not presented.

Discussion

In this large cohort of middle-aged and older women, we found that compared to consuming no alcohol at all, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption was associated with smaller weight gain and a lower risk of becoming overweight and/or obese during 13 years of follow-up. These associations remained highly significant after adjustment for multiple lifestyle, clinical, and dietary factors. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the association between alcohol consumption and risk of developing clinically defined overweight and obesity among initially normal-weight individuals.

Previous cross-sectional studies of alcohol intake and body weight have shown positive6–9 or null10–14 associations in men and inverse7, 10–13, 15 or null6, 16 associations in women. Prospective studies that focused on weight change have been equally inconsistent across populations. In the Framingham Heart Study, both men and women who increased their alcohol consumption during 20 years of follow-up experienced weight gains larger than the average.31 In the Nurses Health Study (NHS) I, an inverse association between alcohol intake and 8-year weight gain was found among 31,940 non-smoking women.32 A similar association was noted in the NHS II: light-to-moderate alcohol intake up to 30 g/day, but not exceeding 30 g/day, was inversely associated with weight gain and the odds of weight gain ≥5 kg in 8 years.20 In the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study of 7,230 participants, women (p, trend = 0.006) but not men (p, trend = 0.11) who consumed alcohol gained less weight over 10 years than those who did not.19 Among Chinese adults, alcohol consumption was associated with a significantly greater risk of >5 kg weight gain over 8 years in men (RR=1.55) but not in women (RR=1.08);33 for both Finnish men and women, drinking alcohol >75 g/week was associated with a significantly higher risk of ≥5 kg weight gain over 5.7 years;16 and for British men, alcohol consumption of ≥30 g/day significantly increased BMI and the risk of weight gain ≥4% over a 5-year period (OR=1.29) compared to none/occasional drinkers.17 In contrast to these studies, two cohort studies found no significant association between alcohol intake and weight change in either men or women.18, 34 None of these studies investigated the development of clinically defined overweight or obesity as the endpoint.

The association of alcohol consumption with body weight change and development of obesity seems to differ by gender, which must be considered in the context of energy balance. Male drinkers tend to add alcohol to their daily dietary intake, while female drinkers usually substitute alcohol for other foods without increasing total energy intake.11, 35 Consistent with previous findings,7, 10, 11, 14 our study showed that women consuming more alcohol had lower energy intake from non-alcohol source, particularly carbohydrates. On the other hand, there may also be gender-specific differences in the metabolism of alcohol. Compared with male drinkers, female drinkers appear to have a lower activity of alcohol dehydrogenase36 and thus are more likely to degrade ethanol through other pathways such as the hepatic microsomal ethanol oxidizing system, which has a low efficiency of energy utilization and a high energy expenditure.37 Metabolic studies have shown that after drinking alcohol, energy expenditure moderately changed in men38 but substantially increased beyond the energy content of consumed alcohol in women.39 Taken together, regular alcohol consumption would potentially result in a gain of energy balance in men while a net energy loss in women. There have been other mechanisms through which alcohol may modify energy balance and subsequently body weight, including impact on nutrient digestion and absorption, interference with lipid oxidation and fat accumulation,5 increased sympathetic tone and associated thermogenesis, and enhanced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) breakdown.40

Complex interrelationships of alcohol consumption with various lifestyle, clinical, and physiological factors involve in the effect of alcohol drinking on body weight change, and thus partially explain the inconsistent findings in epidemiologic studies. For example, drinking habits may change appetite and the perception of satiety, whereby alcohol drinkers would prefer certain diet.7, 9–11, 15 Alcohol metabolism appears more efficient in heavy subjects,38 therefore alcohol intake may be more likely to promote weight gain in overweight women than in lean women.41, 42 In our study, higher alcohol consumption was generally associated with more current smoking, more physical activity, slightly lower baseline BMI, and less healthy diet. However, the association between light-to-moderate alcohol intake and smaller weight gain and lower risk of becoming overweight or obese remained strong after multivariate adjustment and in subgroup analyses, indicating that alcohol consumption may independently affect body weight beyond its impact through dietary and lifestyle factors. Since body weight change and body mass composition vary by age, we also specifically stratified our analyses by baseline age. As expected, we found that weight gain gradually diminished with increasing age. Nevertheless, the trend of association between alcohol intake and body weight change were similar across different age groups.

In this study, we cannot separate former drinkers who stopped drinking due to illness from lifelong abstainers. However, this should not substantially influence our study results, because the WHS cohort had excluded participants with major chronic diseases at baseline. We also excluded women with baseline diabetes from our analyses. In the sensitivity analyses, we further censored women who developed major illness during follow-up and the results remained unchanged. Our study results only apply to light-to-moderate alcohol consumption in association with body weight change. Because very few women in our study reported heavy alcohol intake, we cannot reasonably evaluate the role of heavy alcohol drinking in body weight gain and development of obesity. In our baseline population of women with normal BMI, only 3% consumed alcohol ≥30g/day (corresponding to ≥2–3 drinks per day). In this highest alcohol consumption category, as many as one third of women were current smokers, suggesting that heavy drinkers may have remarkably different lifestyle patterns compared with those consuming lower amounts of alcohol.

Several limitations of this study deserve comment. First, although previous studies have demonstrated excellent validity of self-reported body weight in health professionals,27 self-reported weight remains subject to random misclassification, which would tend to bias our results towards the null and underestimate the true effect. Similarly underreport or underestimation of alcohol intake is possible, and a single baseline assessment did not account for changes over time. However, sensitivity analyses that modeled alcohol intake as a time-dependent variable with update at 48-and 108-month follow-up have obtained similar results. Second, because the questionnaire used in the WHS did not collect detailed information on drinking pattern, we could not differentiate women who had a small drink in most days of the week from those who consumed multiple drinks in one day per week. Third, as in all observational studies, residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out. However, the observed associations in our study were robust after adjusting for a variety of dietary, lifestyle, and clinical factors, suggesting that the associations are unlikely to be explained by strong confounding. Finally, WHS participants were predominantly white female health professionals, which minimized potential confounding by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors but also limited the generalizability of our study results to other populations.

In conclusion, we found that during a long-term follow-up of middle-aged and older, initially normal-weight women, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption was associated with smaller weight gain and a lower risk of becoming overweight and/or obese compared to abstention. These associations persisted after multivariate adjustment and in subgroup analyses. Our study results suggest that women who have normal body weight and consume light-to-moderate alcohol could maintain their drinking habits without gaining excessive weight. However, taking into account the potential medical and psychosocial problems related to alcohol drinking, any recommendation on alcohol use should be made for the individual after carefully evaluating both adverse and beneficial effects of the drinking behavior in a broad context. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the role of alcohol intake and alcohol metabolism in energy balance, and identify behavioral, physiological, and genetic factors that may modify the alcohol effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants DK081141, DK66401, CA-47988, HL-080467, HL-43851, and HL-65727 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. These grants provided funding for study conduct and data collection. Lu Wang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We are indebted to the 39,876 participants in the Women’s Health Study for their dedicated and conscientious collaboration, and to the entire staff of the Women’s Health Study for their assistance in designing and conducting the trial.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None

References

- 1.Aronne LJ. Classification of obesity and assessment of obesity-related health risks. Obes Res. 2002;10 (Suppl 2):105S–115S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: executive summary. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:899–917. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. Jama. 2002;288:1723–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of Applied Studies SAaMHSA, US Department of Health and Human Services. . Office of Applied Studies SAaMHSA, US Department of Health and Human Services., ed. NHSDA series H-22. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suter PM. Is alcohol consumption a risk factor for weight gain and obesity? Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2005;42:197–227. doi: 10.1080/10408360590913542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahti-Koski M, Pietinen P, Heliovaara M, Vartiainen E. Associations of body mass index and obesity with physical activity, food choices, alcohol intake, and smoking in the 1982–1997 FINRISK Studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:809–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher M, Gordon T. The relation of drinking and smoking habits to diet: the Lipid Research Clinics Prevalence Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;41:623–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kromhout D, Saris WH, Horst CH. Energy intake, energy expenditure, and smoking in relation to body fatness: the Zutphen Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:668–74. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH. Alcohol and adiposity: effects of quantity and type of drink and time relation with meals. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1436–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruf T, Nagel G, Altenburg HP, Miller AB, Thorand B. Food and nutrient intake, anthropometric measurements and smoking according to alcohol consumption in the EPIC Heidelberg study. Ann Nutr Metab. 2005;49:16–25. doi: 10.1159/000084173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, et al. Alcohol intake in relation to diet and obesity in women and men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:49–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruchow HW, Sobocinski KA, Barboriak JJ, Scheller JG. Alcohol consumption, nutrient intake and relative body weight among US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:289–95. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson DF, Forman MR, Binkin NJ, Gentry EM, Remington PL, Trowbridge FL. Alcohol and body weight in United States adults. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:1324–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.10.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson M, Fulton M, Elton RA, Brown S, Wood DA, Oliver MF. Alcohol consumption and nutrient intake in middle-aged Scottish men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:139–45. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BR, Barrett-Connor E, Criqui MH, Holdbrook MJ. A community study of calorie and nutrient intake in drinkers and nondrinkers of alcohol. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;35:135–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rissanen AM, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Reunanen A, Aromaa A. Determinants of weight gain and overweight in adult Finns. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45:419–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG. Alcohol, body weight, and weight gain in middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1312–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, French SA, Hannan PJ, Murray DM. Predictors of weight gain in the Pound of Prevention study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:395–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Serdula MK, Williamson DF, Mokdad AH, Byers T. A prospective study of alcohol intake and change in body weight among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:912–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wannamethee SG, Field AE, Colditz GA, Rimm EB. Alcohol intake and 8-year weight gain in women: a prospective study. Obes Res. 2004;12:1386–96. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buring JE, Hennekens CH. The Women’s Health Study: summary of the study design. Journal of Mycardial Ischemia. 1992;4:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook NR, Lee IM, Gaziano JM, et al. Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005;294:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005;294:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Beta-carotene supplementation and incidence of cancer and cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:2102–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovannucci E, Colditz G, Stampfer MJ, et al. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:810–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, et al. The influence of age, relative weight, smoking, and alcohol intake on the reproducibility of a dietary questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1987;16:392–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1:466–73. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyholm M, Gullberg B, Merlo J, Lundqvist-Persson C, Rastam L, Lindblad U. The validity of obesity based on self-reported weight and height: Implications for population studies. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:197–208. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolton-Smith C, Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Morrison C. Accuracy of the estimated prevalence of obesity from self reported height and weight in an adult Scottish population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:143–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillum RF, Sempos CT. Ethnic variation in validity of classification of overweight and obesity using self-reported weight and height in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr J. 2005;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon T, Kannel WB. Drinking and its relation to smoking, BP, blood lipids, and uric acid. The Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1366–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, London SJ, Segal MR, Speizer FE. Patterns of weight change and their relation to diet in a cohort of healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:1100–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM. Weight gain and its predictors in Chinese adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1079–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.French SA, Jeffery RW, Forster JL, McGovern PG, Kelder SH, Baxter JE. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: the Healthy Worker Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yung L, Gordis E, Holt J. Dietary choices and likelihood of abstinence among alcoholic patients in an outpatient clinic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1983;12:355–62. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(83)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, Terpin M, Baraona E, Lieber CS. High blood alcohol levels in women. The role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:95–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lands WE, Zakhari S. The case of the missing calories. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:47–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suter PM, Schutz Y, Jequier E. The effect of ethanol on fat storage in healthy subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:983–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204093261503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klesges RC, Mealer CZ, Klesges LM. Effects of alcohol intake on resting energy expenditure in young women social drinkers. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:805–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lieber CS. Perspectives: do alcohol calories count? Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:976–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crouse JR, Grundy SM. Effects of alcohol on plasma lipoproteins and cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism in man. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:486–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clevidence BA, Taylor PR, Campbell WS, Judd JT. Lean and heavy women may not use energy from alcohol with equal efficiency. J Nutr. 1995;125:2536–40. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.10.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]