Abstract

In recent years, concern has been raised about girls’ involvement in sexual activity at progressively younger ages. Little is known about the prevalence of emerging intimate behaviors, the psychosocial factors associated with these behaviors, or the moderating effects of race on these associations in early adolescence. In the current prospective study, we examine the prevalence and predictors of sexually intimate behaviors at age 12 years in an urban community sample of 1,116 racially diverse girls. Cluster analysis revealed three groups at age 12: none, mild (e.g. holding hands) and moderate (e.g. laying together). Minority group girls reported higher rates of both mild and moderate sexually intimate behaviors compared with European American girls. After controlling for the significant effects of age 11 intimate behaviors, lifetime alcohol use, poor parent-child communication, deviant peer behavior, onset of menarche, and interactions between race and impulsivity, social self-worth and depression uniquely increased the odds of engaging in moderately intimate behaviors at age 12 years. Parenting characteristics increased the likelihood of moderate, relative to mild, behaviors. For European American girls only, high levels of impulsivity and low social self-worth were associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in moderate intimate behaviors, whereas high levels of depressive symptoms reduced the odds. The results suggest that early prevention efforts need to incorporate awareness of different social norms relating to sexual behavior.

Keywords: Risk factors, Girls, Sexual behavior, Problem behaviors, Peers, Parenting

Introduction

During the past few decades, rates of sexual activity among progressively younger adolescents have increased (e.g. Albert, Brown & Flanigan, 2003; Terry & Manlove, 2000), and this trend has been more evident among girls than boys (Manlove & Terry, 2000). Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth revealed that 6% of females reported initiation of heterosexual intercourse prior to age 14 years (Abma, Martinez, Mosher & Dawson, 2004). Whereas a transition to first sexual intercourse by mid-to late-adolescence is considered normative and is not necessarily associated with negative consequences, early initiation of sexual intercourse (i.e. typically defined as age 14 and younger) is associated with lower rates of contraception use, and increased rates of unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (e.g. Albert et al., 2003; Crockett, Bingham, Chopak & Vicary, 1996; Kaestle, Halpern, Miller & Ford, 2005; Kirby, 1997; Manlove, Franzetta, McKinney, Papillo & Terry-Humen, 2004; Niccolai et al., 2004). These findings, coupled with a recent increase in teenage pregnancy rates in the US (Hamilton, Martin & Ventura, 2007) and the limited success of many programs aimed at reducing rates of teenage pregnancy (Frost & Forrest, 1995), represent major public health concerns.

Success in preventing or reducing the adverse outcomes for adolescents depends to a large extent on identifying the behaviors that precede early sexual intercourse. Prevention strategies that have focused on ‘adolescent-specific’ social and demographic correlates of pregnancy status, such as frequency of intercourse, number of sexual partners, and inconsistent use of contraception have lacked efficacy (Frost & Forrest, 1995). Greater success may be achieved by shifting the focus to the nature and covariates of sexually intimate behaviors at an earlier stage of development, prior to the onset of sexual intercourse. There remains however, a dearth of information on the nature and development of non-coital sexual behavior in the early years of adolescence (i.e. 11–13 years). One of the goals of the current prospective study therefore, is to gain a better understanding of the characteristics of young adolescents’ non-coital, heterosexual intimate behavior, prior to initiation of sexual intercourse.

Although responsibility for teen pregnancy and STIs clearly rests on both girls’ and boys’ behavior, early sexual activity and its outcomes elicit more social stigma and disapproval for girls than for boys (Benda & DiBlasio, 1994; Davies et al., 2004) and have more negative emotional and interpersonal consequences for girls (Dickson, Paul, Herbison & Silva, 1998; Graber, Brooks-Gunn & Galen, 1998). For example, using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Cuffee, Hallfors and Waller (2007) reported that 15–21 year-old females perceived fewer positive benefits from sex, and more guilt and shame compared with males. These findings suggest that girls may be especially vulnerable to negative social and emotional factors associated with early heterosexual behavior. As a result, the current study focuses on the emergence of intimate behaviors among young girls.

There are data to support the widely held belief that normative heterosexual behavior among older adolescents develops in an orderly, progressive sequence. Specifically, studies have identified stages of non-coital sexual interactions, such that one type (e.g. spending time alone with a boy, kissing, or fondling above the waist) generally precedes engagement in the next (e.g. fondling below the waist and sexual intercourse) (e.g. Brooks-Gunn & Paikoff, 1999; Hansen, Wolkenstein & Hahn, 1992; Jacobsen, 1997; Robinson, Ziss, Ganza, Katz & Robinson, 1991; Schwartz, 1999; Thornton, 1990)1. In few research studies however, has the effect of race on the progression from non-coital to coital behavior been examined, despite the well-replicated finding that African American youth tend to initiate sexual intercourse earlier than European American youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Santelli et al., 2004; Upchurch, Levy-Storms, Sucoff & Aneshensel, 1998), and that African American adolescents tend to be more accepting of sexual intercourse at younger ages (e.g. Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1994). A notable exception is a study described by Smith and Udry (1985). These investigators conducted separate, cross-sectional analyses of the non-coital behaviors of 1,368 high school students (aged 12–15 years) by racial group. Their data suggested that, in contrast to their European American counterparts, African American adolescents showed ‘no apparent predictable progression in pre-coital sexual activity’ (p.1201), and also reported engaging in few pre-coital petting behaviors prior to sexual intercourse. These findings indicate that efforts to understand the psychosocial factors associated with emergence of intimate behavior should also examine whether the nature of these relationships varies by racial group.

In addition to the above studies on progression and race differences in the sexual behavior of older adolescents, there is extensive research on the individual (e.g. behavioral or emotional problems, substance use), social (peer relationships, parenting quality) and biological (e.g. pubertal timing) influences on early initiation of sexual intercourse. These broad domains of identified explanatory factors are the basis from which we begin to examine multivariate characteristics associated with young girls’ sexually intimate behaviors in the present study.

Early Sexual Behavior as Part of a “Problem Behavior Syndrome”

Problem behavior theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977) provides an overarching framework for understanding socially defined maladaptive, or concerning behavior, which is how risky sexual activity in adolescents has often been conceptualized. The theory states that perceived environment factors (e.g. low parental controls or support, positive peer models for sexual risk-taking, and high peer: parent relative influence) increase the likelihood of problem behaviors occurring. Furthermore, involvement in one behavior (e.g. deviant or delinquent behavior) increases the likelihood of involvement in other problem behaviors (e.g. substance use) due to similarities in the personal and social functions of problem behaviors. In addition to defining behaviors as ‘problematic’ because they elicit general social disapproval, the theory also proposes a developmental definition of problem behaviors, as a departure from age-graded norms.

Evidence from both clinic-referred and community samples of adolescent girls, has shown that both conduct disorder (CD) and aggressive behavior are associated with sexual risk-taking, such as early onset sexual intercourse and involvement with multiple partners (Brendgen, Wanner & Vitaro, 2007; Kovacs, Krol & Voti, 1994). Other support for problem behaviors clustering together as part of an underlying syndrome comes from studies showing that poor impulse control, and low levels of behavioral self-regulation are linked with risky sexual activity (Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Feldman & Brown, 1993; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Kahn, Kaplowitz, Goodman & Emans, 2002; Raffaelli & Crockett, 2003), and that early adolescent sexual activity is associated with alcohol and drug use (Fortenberry, 1995; Hops, Andrews, Duncan, Duncan & Tildesley, 2000; Mott, Fondell, Hu, Kowaleski-Jones & Menaghan, 1996; Stueve & O’Donnell, 2005). Findings also suggest that these relationships may be moderated by racial group, such that the risky sexual behavior of European American adolescents is more closely associated with behavior problems and substance use than it is for African American adolescents (Doljanac & Zimmerman, 1998). In the present study we test whether there is evidence for a ‘problem behavior syndrome’ that includes pre-coital sexually intimate behaviors in younger adolescents, and whether the association between sexually intimate behaviors and behavior problems varies by race.

Parental and Peer Influences

Parenting practices may be directly or indirectly related to adolescent sexual behaviors (Christopher & Roosa, 1991). For example, empirical studies indicate that infrequent or restrictive parent-adolescent discussions about sex are related to higher rates of adolescent sexual activity (Dilorio, Kelley & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999). Indirect parental influences (i.e. not directly related to issues of adolescent sexuality) include family process and contextual variables. Within this body of research, results suggest that low maternal warmth, parental support and both low parental control and high levels of intrusive parental control (Jaccard, Dittus & Gordon, 1996; Miller et al., 1997; Raffaelli & Crockett, 2003; Upchurch, Aneshensel, Sucoff & Levy-Storms, 1999) predicted girls’ earlier age at first intercourse. However, as evident in a review by Miller, Benson and Galbraith (2001), results pertaining to parental control and parent-adolescent communication are mixed and many studies report no relationship between these parental factors and the initiation of sexual intercourse (e.g. Stanton et al., 2002). These mixed findings may reflect variations in the ages of adolescent samples, and as Lam and colleagues (2008) suggest, one might expect parenting influences to be especially salient for the behavior of younger, as opposed to older, adolescents. In terms of other familial contextual influences, studies have shown that low household income (e.g. Lauritzen, 1994; Rose et al., 2005) and living in a single parent household (Fergusson, Horwood & Lynskey, 1994; Upchurch et al., 1998) are both predictive of earlier onset sexual activity among adolescents.

Peer factors have been consistently shown to be linked with sexual activity (e.g. Kinsman, Romer, Furstenberg & Schwarz, 1998). Results from prospective studies have indicated that perceptions of peer sexual involvement predict sexual activity in subsequent years (Miller et al., 1997; Stanton et al., 2002), and some research suggests that this is especially so among African American adolescents (Romer et al., 1994). There is also evidence that general peer deviance is important. For example, in a study of adolescent boys, Capaldi (1991) reported that onset of sexual intercourse was predicted by prior affiliation with deviant peers three years earlier. Based on data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Raffaelli & Crockett (2003) also reported that pressure by peers to engage in misconduct or delinquent activities assessed when respondents were 12–13 years, predicted adolescents’ sexual risk-taking 4 years later. Consistent with problem behavior theory, yielding to negative peer pressure to engage in risky sexual behavior is likely to result in increased peer acceptance within the social group. Indeed, many adolescents associate having sexual relations with high social status and popularity among peers (Prinstein, Meade & Cohen, 2003). Different social norms about the timing of sexual transitions may also partly explain differences in timing of on set of sexual intercourse among African American and European American adolescents (e.g. Coates, 1999; East, 1998).

More information is needed about the role of individuals’ perceived social self-worth in the progression to sexually active behavior, given that assertiveness and refusal skills training have been identified as critical components in adolescent abstinence programs (Kirby, 2000) and successful interventions (Jemmott, Jemmott & Fong, 1998). Nevertheless, there are some limited data to suggest that adolescents who believed they were able to resist peer pressure were less likely to have had sex (Dilorio et al., 2001).

Depressed mood and sexual activity

In cross-sectional studies, the frequency of sexual activity has been shown to be higher among females who are depressed compared to those who are not (e.g. Abrahamse, Morrison & Waite, 1988; Smith, 1997), and it has been postulated that depressed girls may engage in sexual behavior to seek intimacy or to fend off social isolation (Kovacs et al., 1994). Empirical support for this notion, however, is lacking (Smith, 2001), and it is widely believed that early sexual activity predates depression. Yet findings from the few prospective studies that have been conducted are equivocal on this hypothesis. For example, some research shows that psychological distress (DiClemente et al., 2001), low self-esteem (Spencer, Zimet, Aalsma & Orr, 2002) and depressive symptoms (Whitbeck, Conger, Simons & Kao, 1993) predict early sexual behaviors, whereas Tubman, Windle and Windle (1996) reported no relationship between depressed mood and early onset sexual intercourse. In another study examining reciprocal effects, Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford and Halpern (2005) reported that mid-adolescent girls who experimented with sex were more likely to be depressed a year later, whereas depression did not precede ‘experimental behavior’ (defined as a combination of substance use, sexual behavior and drinking). Examination of these relationships is clearly warranted during the early adolescent period; a time when both depression and sexual interest begin to increase.

Impact of Pubertal Development on Sexual Behavior

Results from longitudinal studies have shown that early pubertal maturation among girls has been linked to earlier initiation of sexual activity (Cauffman & Steinberg, 1996; Smolak, Levine & Gralen, 1993), likely reflecting an interaction between biological and psychosocial factors. For example, physical maturity may elicit greater freedom from parents and a tendency to affiliate with older males, which may increase the likelihood of engaging in sexual activity (Gowen, Feldman & Diaz, 2004). Hormonal changes (e.g. rises in DHEA, testosterone and estradiol) also heighten sexual arousal and attraction to others (McClintock & Herdt, 1996), leading early maturing girls to seek out romantic and sexual partners. Early pubertal development has also been linked with higher levels of depressed mood and problem behavior in girls (Flannery, Rowe & Gulley, 1993; Ge, Conger & Elder, 2001; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley & Brooks-Gunn, 1997). Although African American girls tend to reach menarche at an earlier age than European American girls do (Chumlea et al., 2003; Obeidallah, Brennan, Brooks-Gunn, Kindlon & Earls, 2000; Wu, Mendola & Buck, 2002), it remains to be seen whether race moderates an association between early age at menarche and non-coital intimate behaviors among girls who have not yet engaged in sexual intercourse. One of the goals of the current study is to address this gap.

In summary, results from the existing literature point to several domains of predictors for early initiation of sexual behavior among adolescents, but far less attention has been paid to understanding the nature and predictors of emerging non-coital behaviors among girls, especially in early adolescence. Just as sexual behavior is known to be multiply determined, it is likely that non-coital intimate behaviors are also, and research is needed to examine the relative import of individual (e.g. behavioral or emotional problems, substance use), social (peer relationships, parenting quality) and psychobiological (e.g. pubertal timing) influences.

The Present Study

The first goal of the current prospective study is to examine the prevalence and multiple-domain predictors of sexually intimate, non-coital behavior among young female adolescents. Our approach of focusing on the prediction of non-normative intimate behavior in a population sample is consistent with a problem behavior framework. We considered early intimate behaviors to be multiply determined and therefore expected that individual, social and psychobiological influences would be uniquely predictive after controlling for prior intimate behavior, household poverty and single parent status. Data were drawn from an urban sample of girls aged 11 at Time 1, who were followed up one year later at Time 2. The second goal of the study is to examine the moderating effects of race on these prospective relationships.

We first hypothesize that higher levels of individual problems (i.e. conduct problems, impulsivity, alcohol use and depressive symptoms) at age 11 will be associated with a higher likelihood of girls initiating sexually intimate behaviors at age 12. We also hypothesize that negative environment factors (i.e. low parental warmth, poor parent-child communication, and peer models for deviant behavior) will predict the onset of sexually intimate behavior. In contrast, we expect that high levels of social self-worth will reduce the likelihood of subsequent reports of sexually intimate behavior. Finally, we expect that onset of menarche by age 11 will be associated with girls’ increased sexually intimate behaviors at age 12.

Based on work describing racial differences in sexual activity norms, we expect that individual problems, social and psychobiological factors will be important predictors of moderate intimate behavior among young girls for whom emerging non-coital behavior is less normative. Thus, we hypothesize that after controlling for low SES and prior intimate behaviors, race will moderate the impact of individual and environmental problems and early age at menarche on the likelihood of sexually intimate behaviors. Specifically, we expect a weaker influence of these multiple domains for African American compared with European American girls.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study consist of girls from the ongoing, longitudinal Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS), in which the development of conduct disorder, depression and substance use is examined. The PGS sample comprises 2,451 girls who were recruited at ages 5 to 8 years following the enumeration of 103,238 city households in 1999/2000. All the homes in neighborhoods in which more than 25% of the families were living in poverty, and 50% of the homes in the remaining neighborhoods, were enumerated. This process identified 3,241 5-to 8-year old girls, representing 83.7% of the girls identified by the 2000 US Census. Of 2,876 girls who were truly eligible by virtue of their age and who could also be located subsequently, 2,451 (85.2%) agreed to participate in the annual assessment waves of the longitudinal study (see Hipwell et al., 2002 for further details).

The current analyses were based on the two middle cohorts of girls(n=1,241), using data from the age 11 (mean =11.58 years, SD = .35) assessment, when measures of sexually intimate behavior were first introduced, with follow-up one year later at age 12 (mean = 12.60 years, SD = .36). Retention of the sample was high 92.2% (n=1,144) of the sample was interviewed at ages 11 and 12. Data on sexually intimate behaviors were not available for 10 girls because their parents requested that questions pertaining to sex should not be asked. In addition, 18 girls were excluded from the current analyses because they or their caregiver reported that they had been the victims of sexual abuse. Therefore, the analyses reported here are based on a sample of 1,116 girls; none of whom reported that they had had sexual intercourse by age 12.

Approximately half of the girls (54.8%) were African American, 39% were European American, and 6.2% were described by their caregiver as multi-racial or belonging to an ‘other’ race group. Most of the multi-racial girls (88.1%) were African American and another race. Thus, although the vast majority of the non-European American girls were African American, a small portion represented other minority races. We therefore refer to these girls as being of a minority race. All families spoke English in the home. At Time 1, more than one third of the households (37.0%) were supported by some form of public assistance (e.g., food stamps, Medicaid, or monies from public aid), 14.8% of parents had received less than 12 years of education and 41.6% of the households were headed by a single parent. More families in the minority (51.6%) than European American (15.4%) groups received public assistance (χ2 [1]= 145.77, p<.001), and a greater proportion of minority families were headed by a single parent (55.9% vs. 19.2% European American families) (χ2 [1]=144.51, p<.001).

Procedure

Approval for all study procedures was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent from the caregiver and verbal assent from the child were obtained prior to data collection. The limits of confidentiality were explained as part of the consenting procedure. Face-to-face interviews were then conducted separately and privately with the parent and with the girl in the home by interviewers using a laptop computer. Interviewers received extensive training on building a rapport with participants and obtaining high quality data on sensitive topics such as sexual involvement, substance use, and delinquent behavior. All the participants were financially reimbursed for their help with the study.

Measures

Demographic Data were collected via parent report and included information on race, household structure, and household receipt of public assistance. In the current analyses, the following binary variables were created: 0 (minority race) vs. 1 (European American race); 0 (single-parent) vs. 1 (dual-parent household); and 0 (household poverty) vs. 1 (non-poverty).

Sexually Intimate Behaviors

Girls were asked about sexually intimate behaviors in the past year using 10 items adapted from the 13-item Adolescent Sexual Activity Index (ASAI, Hansen, Paskett & Carter, 1999). The ASAI has been validated on a large community sample of male and female adolescents (aged 12–19), and has demonstrated high internal consistency, and construct validity (Hansen et al., 1999). Items ranging from spending time alone with a boy, to engaging in sexual intercourse, were scored as either 0 (no) or 1 (yes). The adapted measure used in the current study utilized a ‘past year’ timeframe instead of the ‘past 30 days’ of the original measure to enable low frequency behaviors to be captured. Because girls reporting that they had had sexual intercourse were excluded from the current analyses, data from 3 ASAI items (the number of times the girl had had sexual intercourse in the past 30 days, the number of different people she had had sex with in the past 30 days, and in the past year) were not used in generating clusters or continuous scores. An additional item assessing girls’ participation in oral sex was administered at age 12. As a result of these modifications, the index generated from transformed scores described by Hansen et al. (1999) could not be used in the current analyses.

Symptoms of Conduct Disorder and Impulsivity were assessed using the Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4, Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994). The CSI-4 is a DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) based checklist that includes 15 symptoms of Conduct Disorder (CD) and 3 symptoms of Impulsivity, which are scored on 4-point scales ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). To generate symptom levels that corresponded to the frequency threshold for DSM-IV symptoms of CD, endorsement at the level of often or very often was required for ‘bullying’, ‘fighting’, ‘lying’ and ‘staying out at night’, and endorsement at the level of sometimes, often, or very often was required for the remaining items. All symptoms of impulsivity were generated from counts of often and very often. In the current study, a ‘best-estimate’ approach to CD symptoms was taken by counting a symptom that was endorsed by the girl, her parent, or both. Child impulsivity symptoms were based on parent report. The CD and impulsivity subscales of the CSI-4 have shown good concurrent validity, sensitivity and specificity to clinicians’ diagnoses (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994). Cronbach’s alphas for the CD and impulsivity symptom counts in the current study were .71 and .80 respectively.

Alcohol Use was assessed using the Nicotine, Alcohol and Drug Use scale adapted from questions on quantity and frequency of substance use developed for the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (Pandina, Labouvie & White, 1984). In the first PGS assessment wave (girls aged 6 and 7 years), girls were asked if they had ever used beer, wine, or liquor. If the girl responded affirmatively, she was then asked about the frequency of use in the past year (ranging from none to every day or several times daily). In every subsequent assessment, girls were asked about past year use using the same response format. Because the distribution of this variable showed a strong positive skew at age 11, it was reduced to a binary score indicating whether the girl had ever used alcohol: 0 (never) and 1 (one or more times).

Depressive symptoms

Child report on the CSI-4 (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994) was used to assess 12 symptoms of depression. Seven items were scored on 4-point scales ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (very often), and 5 items referring to changes in appetite, sleep, activity, concentration, and a drop in school-grades were scored as 0 (no) or 1 (yes). For generating symptom counts, the number of often and very often responses of the first seven items were summed and combined with the yes responses of the remainder. The depression subscale has shown high sensitivity and moderate specificity to diagnosed depressive disorder, and good concurrent validity (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994). The scale also showed good internal consistency in the current sample (α =.78).

Low Parental Warmth was assessed using a 6-item subscale of the Parent-Child Rating Scale (PCRS, Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber & Van Kammen, 1998) completed by the caregiver. The PCRS evaluated the frequency of positive and negative feelings by parents towards their daughters. The low warmth subscale included items such as, “How often have you felt you needed a vacation from her”, or “felt she needed too much attention”. Each item was scored on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 3 (often) and summed to produce a total score. Higher total scores denoted lower levels of warmth. Cronbach’s alpha was .76 for this scale.

Poor Parent-child Communication was assessed using 4 parent-rated items from the Supervision Involvement Scale (Loeber et al., 1998). These items assessed the parent’s perception of the amount of parent-daughter discussions by rating how recently and how frequently the parent had talked with his/her daughter about her plans for the coming day, and about what she had actually done. The items were rated on 4-point scales to assess both recency (1 = yesterday/today to 4 = more than one month ago) and frequency (1 = almost every day to 4 = less than once a month). The items were summed, with higher total scores denoting poorer levels of parent-child communication. The internal consistency of this scale in the current sample was good (α = .80).

Deviant Peer Behaviors were assessed using girls’ report on the Peer Delinquency Scale (PDS, Loeber et al., 1998). This measure assesses the number of deviant behaviors engaged in by one or more peers. The 12 items assessed a range of deviant behaviors, including interpersonal aggression, stealing, destruction of property, and substance use. The measure did not assess peer sexual activity. Items (e.g. “Has/have your friend(s) ever hit other kids or gotten into a physical fight with them”, “taken something from school that belonged to a teacher or to other students”)were scored as 0 (no) or 1 (yes) for girls reporting having a single friend, and ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (all of them) for girls with multiple close friends. For the current analyses, the response format for girls reporting more than one close friend was collapsed to a binary response indicating whether none or one or more peers engaged in each behavior. The endorsed items were then counted to create a total score ranging from 0–12. The total score demonstrated good reliability (α = .77).

Social Self-worth was assessed using the Perception of Peers and Self Inventory (POPS, Rudolph, Hammen & Burge, 1995). The POPS measures the child’s conceptions of relationships by assessing their generalized perceptions of their peers, their self-competence and their social self-worth. The 8 items of the social self-worth subscale (e.g., “I have always been the kind of kid who makes friends easily”) were used in the current analyses. The child responded to each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much) such that high scores reflected high social self-worth. A total score that was generated by summing the 15 items, had adequate internal consistency (α = .69).

Onset of Menarche was assessed using a single item scored as 0 (no) or 1 (yes) on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards & Boxer, 1988) administered at age 11 years. Although menarche occurs late in the pubertal process, it is the most frequently reported measure of pubertal timing (e.g. Graber, Petersen & Brooks-Gunn, 1996).

Data Analysis Plan

In the current analyses, independent variables (i.e. demographic characteristics, conduct problems, impulsivity, alcohol use, depressive symptoms, low parental warmth, poor parent-child communication, deviant peer behaviors, social self-worth, and onset of menarche) were assessed at age 11. Sexually intimate behaviors were assessed at 11 and 12 years. Our goal was to examine predictors of age 12 sexually intimate behavior, after controlling for the variance explained by intimate behaviors reported in the prior year.

All the analyses were conducted using a weight variable to correct for the over-sampling of families living in low-income neighborhoods, enabling the results to be representative of girls living in the City of Pittsburgh. This weight variable was generated by comparing the proportions of neighborhoods represented in the study, to the proportions of neighborhoods in the City in which girls in the same age range were living (using data from the 2000 US Census). This comparison indicated that the low income neighborhoods were over-represented in the PGS by a ratio of 1.82:1. To adjust back to the City population therefore, a weighting of .67 was applied to data from girls in low income neighborhoods, and 1.23 to data from girls in the remaining neighborhoods (see Hipwell et al., 2002 for more details).

Cluster analysis was run using Latent Gold 4.0 (Vermunt & Magidson, 2005) to identify empirically defined groupings of the ASAI items at age 12. One to four class solutions were examined and a three-class solution provided the best model fit (BIC = 4446.53), with classes representing: no intimate behaviors (47.9%), mild (45.9%) and moderate behaviors (6.2%). The mean indicator values for girls in the mild group ranged from 0 to .69 for the items: spending time alone with a boy, holding hands, and kissing. Almost all of the girls in this group also reported hugging a boy (indicator value = .91). No other ASAI items were endorsed. In contrast, the full range of ASAI behaviors were endorsed by girls in the moderate group, with mean indicator values ranging from .04 to .99. Because cluster analysis of the age 11 items revealed a two-rather than a three-cluster solution, and the item assessing oral sex was not administered, age 11 intimate behaviors were assessed via the continuous ASAI summary score, which was then controlled in subsequent analyses.

Differences in the continuously scored independent variables (i.e. conduct problems, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, parental warmth, parent-child communication, deviant peer behavior, and social self-worth) according to racial group were tested using univariate analysis of variance. Effect sizes (η) were calculated to evaluate the magnitude of any differences, with η < 0.3 being interpreted as a small effect (Cohen, 1988). Racial group differences on the dichotomous independent variables (alcohol use, onset of menarche) were tested using Chi-square analyses.

A stepwise multinomial logistic regression was conducted to examine whether age 11 independent variables increased the probability of 12-year-old girls’ reporting moderate intimate behaviors relative to none or mild behavior over and above pre-existing age 11 intimate behaviors. Analyses were conducted using STATA software version 9. All continuous variables were centered to minimize the possibility of multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991). Because the analyses were weighted, variable centering was based on the weighted means. The moderate group was set as the reference group. The predictor variables were entered into the regression analysis in two blocks: the main effects of the independent variables were entered in Step 1; and two-way interactions between the main effects and race were entered into the model in Step 2. Statistically significant two-way interactions were then probed in a reduced model once the non-significant interactions were removed.

Results

The prevalence of sexually intimate behavior types reported by girls at ages 11 and 12 is summarized in Table 1. The majority of girls at age 11 (N=790, 70.8%) reported engaging in no sexually intimate behaviors, and of these girls, 472 (59.7%) also reported none at age 12, whereas 293 (37.1%) were classified in the mild, and 25 (3.2%) in the moderate groups in the following year. Approximately half of the 12-year-old girls (N=535, 47.9%), reported no sexually intimate behaviors. For girls reporting at least one intimate behavior, ‘hugging a boy’ was most commonly reported at both 11 and 12 years, and was as likely to be reported by girls in the mild and moderate groups at age 12. Chi-square analysis revealed that ‘spending time alone’, ‘holding hands’, and ‘kissing’ were significantly more likely to be endorsed by girls in the moderate than the mild groups providing further support for the validity of the groupings.

Table 1.

Prevalence of behavior types for all girls at age 11 and 12 years (N=1,116) and by ‘Mild’ and ‘Moderate’ intimate behavior groups at age 12.

| Age 11 | Age 12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All girls (N=1,116) | All girls (N=1,116) | Mild (N=512) | Moderate(N=69) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | χ2 (df)b | |

| Spent time alone | 93 (8.3) | 163 (14.6) | 123 (24.0) | 40 (58.0) | 34.72(1)*** |

| Held hands | 133 (11.9) | 273 (24.5) | 215 (42.1) | 58 (84.1) | 43.01(1)*** |

| Hugged | 260 (23.3) | 519 (46.5) | 455 (88.9) | 64 (92.8) | ns |

| Kissed | 44 (3.94) | 111 (9.9) | 66 (12.9) | 45 (65.2) | 107.73(1)*** |

| Cuddled | 16 (1.4) | 60 (5.4) | 0 | 60 (87.0) | |

| Laid together | 2 (.2) | 16 (1.4) | 0 | 16 (23.2) | |

| His hands under clothing | 5 (.4) | 7 (.6) | 0 | 7 (10.3) | |

| Your hands under clothing | 2 (.2) | 6 (.5) | 0 | 6 (8.8) | |

| Organs exposed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Oral sex a | - | 2 (.2) | 0 | 2 (3.0) | |

Note:

Question was not asked of 11 year old girls.

Comparing Mild and Moderate groups,

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05

At age 11, there were no differences in the extent of sexually intimate behaviors according to race. At age 12, minority group girls were more likely to report engaging in intimate behavior than European American girls (χ2[2] = 12.22, p<.01). Thus, proportionally more minority group girls reported moderate behaviors compared with European American girls (8% vs. 3.5% respectively), and fewer reported engaging in no intimate behavior (45.1% vs. 52.5% respectively).

Descriptive statistics of the independent variables for the entire sample and by race are presented in Table 2. Among the continuous variables, conduct problems, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, parent-child communication, and deviant peer behavior all differed by racial group with higher levels of these problems reported by minority group girls and their parents, although the effect sizes were small (Cohen, 1988). Minority group girls were also more likely to have reached menarche by age 11, but were less likely to report lifetime alcohol use than European American girls. No differences by race were found on measures assessing low parental warmth or social self-worth.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of independent variables assessed at age 11 for the full sample (N=1,116) and by European American and minority race

| European American | Minority race | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | t or χ2 (df=1) | η |

| Intimate behaviors | 0.50 (.94) | 0–7 | .46 (.96) | .52 (.92) | ns | ||||

| Conduct problems | .46 (.99) | 0–8 | .31 (.80) | .56 (1.09) | ** | .12 | |||

| Impulsivity | .28 (.70) | 0–3 | .20 (.60) | .33 (.75) | * | .09 | |||

| Alcohol use | 118 (10.7) | 67 (15.7) | 50 (7.4) | *** | |||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.69 (1.84) | 0–12 | 1.38 (1.74) | 1.89 (1.89) | *** | .13 | |||

| Low parental warmth | 8.86 (2.24) | 6–18 | 8.88 (2.30) | 8.85 (2.19) | ns | ||||

| Poor parent-child communication | 4.81 (1.48) | 4–13 | 4.48 (1.14) | 5.01 (1.62) | *** | .18 | |||

| Deviant peers | 2.33 (2.21) | 0–11 | 1.53 (1.68) | 2.84 (2.35) | *** | .29 | |||

| Social self-worth | 12.35 (3.18) | 8–32 | 12.31 (3.05) | 12.37 (3.26) | ns | ||||

| Onset of menarche | 360 (32.5) | 87 (20.4) | 272 (40.2) | *** | |||||

Note: η= effect size

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05.

Predicting Sexually Intimate Behavior at Age 12

The results of the multinomial regression analysis for the models containing main effects, and significant interactions between main effects and race are shown in Table 3. In these adjusted models, neither household poverty nor single parent household increased the odds of girls engaging in moderate sexually intimate behavior at age 12.

Table 3.

Results of multinomiallogistic regression of age 11 predictors on age 12 sexually intimate behavior

| Moderate vs. None | Moderate vs. Mild | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Ba | Bb | Adj. ORb | 95% CIb | Ba | Bb | Adj. ORb | 95% CIb |

| Intercept | −1.99 | −2.29** | −3.34*** | −3.29*** | ||||

| Household poverty | .08 | .09 | 1.01 | .61–2.01 | −.05 | .07 | 1.07 | .59–1.93 |

| Single parent | .48 | .46 | 1.58 | .86–2.91 | .16 | .10 | 1.11 | .62–2.00 |

| Minority race | .44 | .84 | 2.31 | .92–5.77 | .56 | .94* | 2.55 | 1.01–6.5 |

| Age 11 intimate behavior | 1.29*** | 1.30*** | 3.66 | 2.71–4.93 | .44*** | .45*** | 1.57 | 1.25–1.97 |

| Conduct problems | .18 | .21 | 1.24 | .92–1.67 | .03 | .02 | 1.02 | .77–1.33 |

| Impulsivity | −.16 | .40 | 1.49 | .75–2.97 | .17 | 1.19*** | 3.29 | 1.65–6.56 |

| Alcohol use | 1.03** | 1.05* | 2.76 | 1.20–6.49 | .26 | .23 | .79 | .36–1.75 |

| Depressive symptoms | −.01 | .01 | 1.01 | .86–1.18 | −.02 | −.56* | .57 | .35–.94 |

| Low parental warmth | −.11 | −.09 | .92 | .79–1.06 | .19* | .15* | 1.21 | 1.05– .39 |

| Poor P-C communication | .21* | .16 | 1.18 | .99–1.39 | .19* | .16* | 1.17 | 1.01–1.37 |

| Deviant peers | .22*** | .22*** | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | .09 | .09 | 1.09 | .97–1.23 |

| Social self-worth | −.13** | −.35** | .71 | .54–.92 | −.05 | −.04 | .96 | .88–1.06 |

| Onset of menarche | 1.15*** | 1.06*** | 2.90 | 1.60–5.23 | .52 | .48 | 1.61 | .91–2.85 |

| Impulsivity x race | −.88* | .42 | .18–.98 | −.15*** | .24 | .10–.55 | ||

| Depression x race | - | - | - | .63* | 1.87 | 1.11–3.14 | ||

| Social self-worth x race | .28* | 1.33 | 1.02–1.76 | - | - | - | ||

Note: Adj. OR= Adjusted Odds Ratio, 95% CI= 95% Confidence Interval.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05.

Beta coefficients for model containing main effects only.

Beta coefficients, odds, ratios and confidence intervals for model including interactions between main effects and race.

In the main effects models, the odds of inclusion in the moderate group relative to both the ‘none’ and the ‘mild’ groups increased significantly for every increase in age 11 intimate behavior, and every decrease in parent-child communication. Thus, as age 11 intimate behavior increased, the odds of being in the moderate group at age 12 increased by 3.6 (95% CI=2.70–4.89) relative to the ‘none’ group, and by 1.6 (95% CI = 1.24–1.93) relative to the ‘mild’ group. As parent-child communication decreased, the odds increased 1.4-fold(95% CI=1.02–1.42) and 1.2-fold(95% CI=1.04–1.41) for inclusion in the moderate intimate behavior group at age 12, relative to the ‘none’ and ‘mild’ groups respectively. Lifetime use of alcohol (OR = 2.8, 95% CI= 1.20–6.49), higher levels of deviant peer behavior (OR = 1.25, 95% CI= 1.10–1.42), onset of menarche by age 11 (OR = 3.15, 95% CI= 1.75–5.64), and lower levels of social self-worth (OR = .88, 95% CI= .80–.97) each increased the odds of girls being in the moderate relative to the ‘none’ group. No differences however, were revealed between the moderate and ‘none’ groups in terms of race, conduct problems, impulsivity, depressive symptoms or parental warmth. In addition to the significant effects of intimate behavior and parent-child communication at age 11, the likelihood of inclusion in the moderate relative to the mild group was increased as a function of low parental warmth (OR = 1.21, 95% CI= 1.05–1.39). None of the remaining variables showed unique prediction to moderate (relative to mild) intimate behavior. The overall model fit for the main effects model was good (Δ-2 Log Likelihood = 284.80[26], p < .001, compared with the intercept-only model) and a moderate amount of variance was explained (Cox and Snell Pseudo R2 = .23).

In the 2nd step of the analysis, the moderating effects of race on the relationships between age 11 individual, social and psychobiological predictors and later intimate behaviors were tested. Two significant interactions were revealed in comparisons between girls in the moderate group relative to girls reporting no intimate behavior: impulsivity x race and social self-worth x race, which were then included in a reduced model with the main effects. With the interactions in the model, the main effects of lifetime alcohol use, deviant peer behavior, social self-worth and onset of menarche after controlling for age 11 intimate behavior remained. The effect of parent-child communication in this model became negligible. In the moderate-relative-to-mild behaviors model, the uniquely predictive effects of parenting quality were not accounted for by the addition of the significant interactions between race and depressive symptoms. Overall fit for the models including main and interaction effects was good (Δ-2 Log Likelihood =301.31 [30], p < .001, for moderate vs. no intimate behavior, and Δ-2 Log Likelihood =301.99 [30], p < .001, for moderate versus mild intimate behavior).

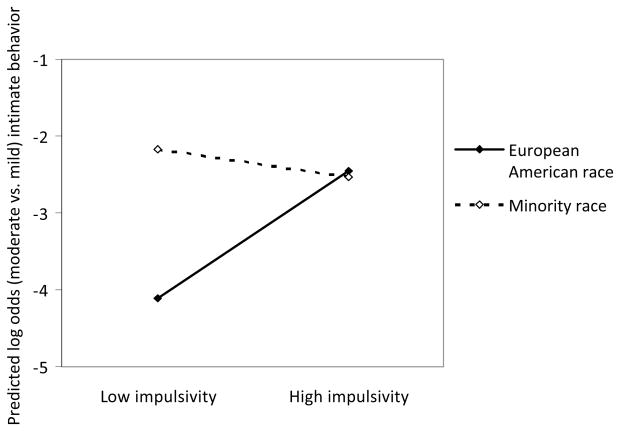

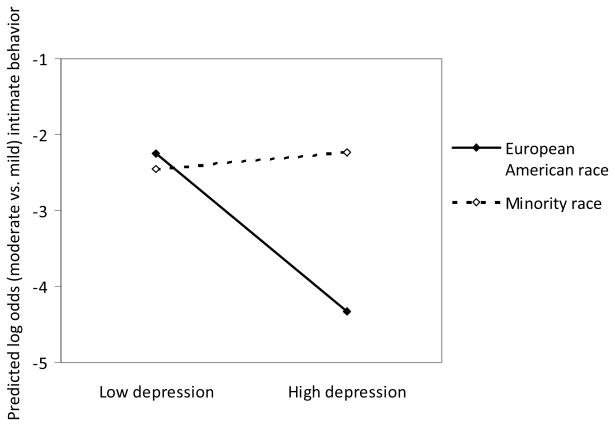

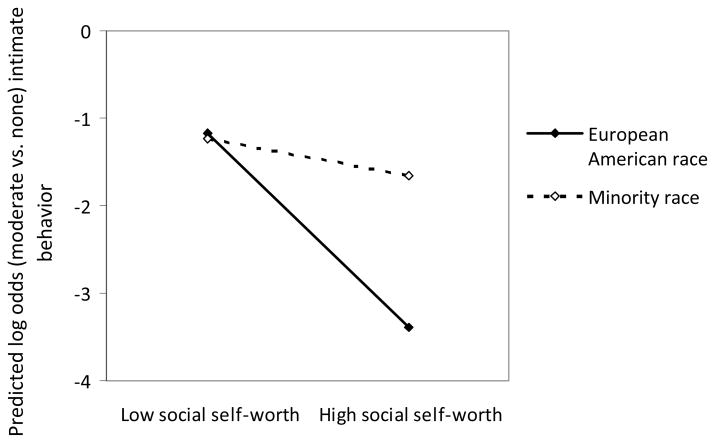

The moderating effects of race on impulsivity and social self-worth were then probed, and plots were generated using the unstandardized regression coefficients of the independent variable, the moderator and the interaction (Aiken & West, 1991). The predicted log odds of engaging in moderate vs. none and moderate vs. mild intimate behaviors are shown in Figures 1–3. The interaction between race and impulsivity was similar across the group comparisons so only the relationship predicting moderate vs. mild is shown. Level of impulsivity did not affect the likelihood of engaging in moderate intimate behaviors among minority group girls, whereas for European American girls, higher levels of impulsivity were associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in moderate intimate behavior at age 12(Figure 1). As shown in Figure 2, European American and minority group girls were at similar risk for moderate intimate behavior relative to none at low levels of social self-worth. However, high social self-worth was differentially associated with a reduced risk for European American girls but not for minority group girls, although a trend in the same direction was observed. Finally, the results depicted in Figure 3 indicate that for European American girls, high levels of depressive symptoms were associated with a lower likelihood of engaging in moderate, relative to mild, sexually intimate behavior compared with girls reporting fewer depressive symptoms. Among minority group girls however, there is little relationship between the likelihood of moderate intimate behavior and self-reported depression.

Figure 1.

Interaction between race and impulsivity : ‘moderate’ versus ‘mild’ groups

Figure 3.

Interaction between race and depressive symptoms : ‘moderate’ versus ‘mild’ groups

Figure 2.

Interaction between race and social self-worth : ‘moderate’ versus ‘none’ groups

Discussion

The results of the current study contribute to the existing literature on the nature and predictors of heterosexual activity by extending the developmental window to the preadolescent period, and expanding the assessment of sexual activity to pre-coital sexually intimate behaviors in a representative, urban sample of young adolescent girls. Cluster analysis of girls’ reports of intimate behavior at age 12 revealed three groups; none, mild and moderate, with a sizeable minority of girls (6.2%) engaging in a range of sexually intimate behaviors. Minority group girls were over-represented among girls in the moderate group, and were under-represented among those reporting that they had not yet engaged in these types of behavior. These early differences in levels of pre-sexual intimate behavior are consistent with prior reports showing more advanced sexual development among African American adolescent girls (e.g. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Santelli et al., 2004). Follow-up data however, are needed to test whether these empirically-derived groupings will have predictive utility for onset of sexual intercourse for the sample as a whole, and for racially defined subgroups. If the development of sexual behavior is indeed ordered and progressive within racial groups, then identifying girls who engage in moderate pre-sexual behaviors at an early age will be critical for effective timing of culturally sensitive interventions to educate and prepare young girls for healthy sexual development.

In our prospective analyses, we identified unique effects in individual, social and psychobiological domains that have not typically been examined together. Our study hypotheses, that early intimate behaviors would be multiply determined, that behavior problems, parenting and peer factors and early onset menarche would be uniquely predictive of intimate behaviors, and that such influences would be more important among European American than minority group girls, were largely supported. Thus, after controlling for the significant effects of prior intimate behavior at age 11, the multinomial regression models revealed that alcohol use, poor parent-child communication, deviant peer behavior, low social self-worth and onset of menarche by age 11 each increased the likelihood of girls engaging in moderate behaviors relative to none at age 12. Among these predictors, alcohol use, deviant peers, and menarche onset appeared to be the most salient. In contrast, increased risk of moderate relative to mild intimate behavior was predicted specifically by parenting characteristics (i.e. poor parent-child communication and low parental warmth). Girls in these two groups were otherwise similar in terms of problem behaviors, peer factors, and pubertal maturation after accounting for the significant predictive effects of age 11 intimate behavior. In each of the models however, the strength of prediction from age 11 intimate behavior to age 12 moderate behavior, suggests that the search for precursors to, and predictors of, sexually risky behavior may need to begin before age 12. In this respect, it remains unclear whether early intimate behavior is part of a syndrome of problem behavior.

Consistent with the results of other studies examining early onset adolescent sexual activity (e.g. Capaldi, 1991; Raffaelli & Crockett, 2003; Stueve & O’Donnell, 2005), alcohol use and deviant peer behaviors increased the odds of girls’ engaging in moderate intimate behavior relative to none, but were not predictive relative to the mild group with other individual, social and psychobiological predictors also included in the model. These results lend further support to the notion that girls in the moderate group were not more behavior disordered than girls in the mild intimate behavior group. Alternatively, it is possible that our measures were not sensitive enough to differentiate risk between these two groups. For example, an effect of peer deviancy may have been detected if questions about perceived peer sexual activity had been included among the items. In comparing the moderate vs. ‘none’ groups, it also remains unclear whether the differing peer processes reflect effects of selection, influence, or a combination of both. Thus, the prospective association does not eliminate the possibility that like-minded ‘deviant’ girls have already befriended each other by age 11, or that girls inclined to moderate intimate behavior (relative to girls reporting none) perceive deviant behaviors in their peers that simply mirror their own. Nevertheless, the fact that the girls were interviewed at a young age prior to first sexual intercourse, lends some support for the notion of peer influence. No moderating effect of race was found for the relationship between peer deviance and intimate behavior, indicating that this association was similar across both racial groups. It will be important to determine whether this continues to be the case with girls’ increasing age, given that the minority group girls reported higher rates of peer deviancy and so may experience more opportunities or peer pressure to engage in sexual risk-taking in due course, and that social expectancies about the timing of sexual transitions are known to differ among African American compared with European American adolescents (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1994; Coates, 1999; East, 1998).

The results also showed that girls who had experienced menarche by age 11 were almost three times as likely as girls reporting no intimate behavior to report moderate levels at age 12 after accounting for prior intimate behavior and a range of important individual and social factors. Although used as a proxy for pubertal stage, menarche occurs late in the pubertal process and it is possible that the timing or rate of psychobiological changes occurring earlier in the process played a more important role in the emergence of intimate behaviors. For example, girls who experience rapid increases in sex hormones in the early stages of maturation may begin to be attracted to others (McClintock & Herdt, 1996) and seek sexual intimacy. Furthermore in our sample, 32% of girls had already reached menarche by age 11, so a great deal of maturational heterogeneity was potentially masked by our measure, which also did not tap an ‘early maturation’ group of girls who may be at heightened risk for problem behavior (e.g. Flannery et al., 1993; Graber et al., 1997). An alternative measure of physical growth and development reflecting an earlier stage in the pubertal process may be warranted in future research examining predictors of non-coital behavior in the early years of adolescence.

The importance of parenting characteristics in differentiating risk for moderate behaviors at age 12 is consistent with prior reports that poor parent-child communication influences early initiation of sexual activity among adolescents. Support for the robustness of the finding in the current study comes from the fact that our measure of parent-child communication was not specific to dyadic discussions of sexual matters, which might directly influence the girl’s behavior. Although such specificity reportedly increases the prediction of timing of sexual debut (Miller et al., 2001), in many studies ‘indirect’ parental effects were reported (Christopher & Roosa, 1991), similar to the ones shown here. It is conceivable that our measure of poor parent-child communication, reflecting parent-child discussions that are neither recent nor frequent, is also a marker of poor parental supervision, which may be more directly responsible for young girls’ involvement in sexually intimate behavior. Future work could examine the relative influence of different aspects of parenting on girls’ emerging sexuality, which may prove useful in tailoring early prevention and intervention programs.

Consistent with our expectations, there was evidence that race moderated problem behavior in predicting engagement in intimate behaviors. Our analyses showed that the likelihood that minority group girls would engage in sexually intimate behavior was unrelated to symptoms of impulsivity, whereas European American girls were more likely to report moderate intimate behavior in the context of high levels of impulsivity. The consistent absence of an association between intimate behavior and impulsivity, depression and social self-worth among minority group girls lends some support to the notion that non-coital behavior is more socially normative than it is for European American girls. If this is the case, then minority group girls may also be less likely to experience negative emotional and interpersonal sequelae in the longer term (Dickson, Paul, Herbison & Silva, 1998; Graber, Brooks-Gunn & Galen, 1998). These possibilities have important clinical implications for girls’ healthy development and clearly need further investigation.

Depressive symptomatology and social self-worth may be critical qualities in the ability to resist peer pressure to engage in sexually intimate behavior. The results of the current study showed that low social self-worth did, in fact, increase the likelihood of girls reporting moderate intimate behaviors compared with girls reporting none. This finding is concordant with a few prospective studies that have examined low self-esteem as a predictor of early sexual intercourse(e.g. Brendgen et al., 2007). In the current study however, social self-worth also interacted with racial group to predict engagement in moderate (relative to no) intimate behavior in girls in early adolescence. Consistent with our hypothesis, minority group girls’ behavior was shown to be relatively unaffected by their reported social self-worth. In contrast, high social self-worth appeared to have a protective effect for European American girls by reducing the likelihood of these girls’ engaging in moderate types of behavior. In a similar vein, Longmore, and colleagues (2004), reported that self-esteem was a stronger predictor of sexual onset for European American, than for African American, mid-adolescent girls (although depressive symptoms exerted a greater effect when also considered in their model). Given that social comparisons and desire for peer approval become more salient during the adolescent period, low social self-worth may heighten vulnerability for early sexual debut and/or sexual risk-taking for European American girls in particular.

The finding that higher levels of depressive symptoms reduced the likelihood of European American girls engaging in moderate, relative to mild, intimate behaviors was consistent with the buffering effect of low impulsivity among this group of girls. As previously, this interaction provided evidence for a weaker relationship between psychosocial influences and intimate behavior among minority group, compared with European American, girls. However it also suggested that greater distress was not linked with a greater departure from intimate behavior norms. An analysis of specific symptoms of depression and the contexts in which girls typically engage in moderate vs. mild intimate behaviors is needed to fully understand this result.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be kept in mind in interpreting the findings and conceptualizing future research. Although we examined a range of factors that have been identified as predictors of adolescent sexual behavior (Kirby, 1997), we did not assess social cognitions such as girls’ intentions or motivations to engage in intimate behaviors, perceptions of peer approval of sexual behavior, or other subjective processes such as the meaning ascribed to experiences, or idealized and romanticized beliefs about heterosexual relationships. Based on evidence from the older adolescent literature (e.g. Buhi & Goodson, 2007; Stanton et al., 1993), it is possible that these additional variables could have improved model fit in the current study. They may also have aided our understanding of the effects of race on the relationship between social self-worth and emerging intimate behavior by, for example, providing much needed information about differential social norms and perceived pressure from peer group interactions.

It is possible that some girls under-reported their experience of intimate behaviors because they believed there could be negative repercussions from positively endorsing such behaviors, or because they felt uncomfortable discussing the topic in a face-to-face interview. This may be a particular problem when interviewing younger, compared with older, adolescents. Other investigators, however, have found that girls aged 12 years and older tend to be highly reliable reporters of sexual experiences (Hearn, O’Sullivan & Dudley, 2003) and that inconsistencies in reports have little effect on overall results (e.g. Upchurch, Lillard, Aneshensel & Li, 2002). Nevertheless, continued follow-up of the current sample will allow us to examine the extent of any inconsistent reporting over time.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to knowledge about the nature of non-coital sexually intimate behaviors in young girls, and provides important insights into the possible effects of individual and environmental characteristics on emerging sexually intimate behaviors. The initial results of our ongoing study suggest that health and sexual education programs delivered in late childhood should facilitate parent-child discussion and involvement in girls’ lives, and help girls develop the necessary skills to resist peer pressure, especially among those affiliated with deviant peers. Importantly, our results point to the possibility that perceptions of and factors leading to early sexual behavior vary as a function of race and therefore prevention efforts that incorporate awareness of different social norms relating to sexual behavior, will be most effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the following grants funded through the National Institute of Mental Health: Dr. Hipwell’s effort was supported by K01 MH07179; Dr. Keenan’s contribution was supported by R01 MH66167, and Dr. Battista’s and Loeber’s contributions were supported by grant R01 MH056630. Special thanks go to the families of the Pittsburgh Girls Study for their participation in this research, to Stephanie Stepp for her statistical advice, and to our dedicated research team.

Footnotes

Recent research indicates that oral sex does not follow this pattern of progression, and a sizeable group of teenagers (16%–35%) report having had oral sex before they have sexual intercourse (Child Trends, 2005; National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 2005). This trend may be partly due to a perception by adolescents that oral sex carries fewer health, social and emotional risks than intercourse does (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007; Remez, 2000).

References

- Abma J, Martinez G, Mosher W, Dawson B. Vital Health Statistics. 24. Vol. 23. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use and childbearing 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamse A, Morrison P, Waite L. Teenagers willing to consider single motherhood: Who is at greatest risk? Family Planning Perspectives. 1988;20:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sex and America’s Teenagers. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Albert B, Brown S, Flanigan C, editors. 14 and younger: the sexual behavior of young adolescents. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Benda B, DiBlasio F. An integration of theory: Adolescent sexual contacts. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Brady S, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ reported consequences of having oral sex vs. vaginal sex. Pediatrics. 2007;119:229–236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Wanner B, Vitaro F. Peer and teacher effects on the early onset of sexual intercourse. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2070–2075. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff R. Sexuality and developmental transition during adolescence. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs J, Hurrelmann J, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 190–219. [Google Scholar]

- Buhi E, Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. Fourth grade predictors of initiation of sexual intercourse by 9th grade for boys. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Seattle. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Steinberg L. Interactive effects of menearcheal status and dating on dieting and disordered eating among adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:631–635. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2003. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2004;53(No SS2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. Child Trends Databank: Oral Sex. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2005. http://www.childtrendsdatabank.org/indicators/95OralSex.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher F, Roosa M. Factors affecting sexual decisions in premarital relationships of adolescents, young adults. In: McKinney K, Sprecher S, editors. Sexuality in close relationships. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chumlea W, Schubert Roche A, Kulin H, Lee P, Himes J, Sun S. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003;111:110–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates D. The cultured and culturing aspects of romantic experience in adolescence. In: Furman W, Brown B, Feiring C, editors. The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. pp. 291–329. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett L, Bingham R, Chopak J, Vicary J. Timing of first sexual intercourse: The role of social control, social learning, and problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1996;25:89–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01537382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffee J, Hallfors D, Waller M. Racial and gender differences in adolescent sexual attitudes and longitudinal associations with coital debut. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Dix E, Rhodes S, Harrington K, Frison S, Willis L. Attitudes of youth African American fathers toward early childbearing. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:418–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Dudley W, Kelly M, Soet J, Mbwara J, Potter J. Social cognitive correlates of sexual experience and condom use among 13-through 15-year-old adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:208–216. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente R, Wingood G, Crosby R, Sionean C, Brown L, Rothbaum B, Zimand E, Cobb B, Harrington K, Davies S. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108:85–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson N, Paul C, Herbison P, Silva P. First sexual intercourse: age, coercion, and later regrets reported by a birth cohort. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:29–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doljanac R, Zimmerman M. Psychosocial factors and high-risk sexual behavior: Race differences among urban adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21:451–465. doi: 10.1023/a:1018784326191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:890–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East P. Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Brown N. Family influences on adolescent male sexuality: The mediational role of self-restraint. Social Development. 1993;2:15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Horwood L, Lynskey M. Parental separation, adolescent psychopathology, and problem behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery D, Rowe D, Gulley B. Impact of pubertal status, timing and age on adolescent sexual experience and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry J. Adolescent substance use and sexually transmitted diseases risk: A review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;16:304–308. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00062-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French D, Dishion T. Predictors of early initiation of sexual intercourse among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Frost J, Forrest J. Understanding the Impact of Effective Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Programs. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27:188–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventories Manual. Stonybrook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger R, Elder G. Pubertal transition, stressful life events and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gowen L, Feldman S, Diaz R. A comparison of the sexual behaviors and attitudes of adolescent girls with older versus similar-aged boyfriends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Graber J, Brooks-Gunn J, Galen B. Betwixt and between: Sexuality in the context of adolescent transitions. In: Jessor R, editor. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 270–316. [Google Scholar]

- Graber J, Lewinsohn P, Seeley J, Brooks-Gunn J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1768–1776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Petersen AC, Brooks-Gunn J. Pubertal processes: methods, measures, and models. In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Waller M, Bauer D, Ford C, Halpern C. Which comes first in adolescence – sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B, Martin J, Ventura S. National Vital Statistics Reports. 7. Vol. 56. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Births: Preliminary Data for 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Paskett ED, Carter LJ. The Adolescent Sexual Activity Index (ASAI): A standardized strategy for measuring interpersonal heterosexual behaviors among youth. Health Education Research. 1999;14:485–490. doi: 10.1093/her/14.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen W, Wolkenstein B, Hahn G. Young adult sexual behaviors: Issues in programming and evaluation. Health Education Research. 1992;7:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup W. Peer interaction: what causes what? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:387–394. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Gotlib I, Schraedley P, Litt I. Ethnic differences in the association between pubertal status and symptoms of depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn K, O’Sullivan L, Dudley C. Assessing reliability of early adolescent girls’ reports of romantic and sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:513–521. doi: 10.1023/a:1026033426547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, Kroneman L. Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2002;12:99–118. doi: 10.1002/cbm.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Andrews J, Duncan S, Duncan R, Tildesley E. Adolescent drug use development. In: Sameroff A, Lewis M, Miller S, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. 2. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 589–605. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus P, Gordon V. Maternal correlates of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen R. Noncoital sexual interactions. Stages of progression in sexual interactions among young adolescents. International Journal of Behavior Development. 1997;21:537–553. [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott J, Jemmott L, Fong G. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle C, Halpern C, Miller W, Ford C. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161:774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J, Kaplowitz R, Goodman E, Emans J. The association between impulsiveness and sexual risk behaviors in adolescent and young adult women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman S, Romer D, Furstenberg F, Schwarz D. Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics. 1998;105:1185–1192. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. No easy answers: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. School-based interventions to prevent unprotected sex and HIV among adolescents. In: Petersen J, DiClemente R, editors. Handbook of HIV Preventions. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use and pregnancy. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26:473–485. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Krol R, Voti L. Early onset psychopathology and the risk for teenage pregnancy among clinically referred girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:106–113. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A, Russell S, Tan T, Leong S. Maternal predictors of noncoital sexual behavior: Examining a nationally representative sample of Asian and White American adolescents who have never had sex. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen J. Explaining race and gender differences in adolescent sexual behavior. Social Forces. 1994;72:859–883. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg L, Jones R, Santelli J. Noncoital sexual activities among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington D, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen W. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore M, Manning W, Giordano P, Rudolph J. Self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and adolescents’ sexual onset. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67:279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Franzetta K, McKinney K, Papillo A, Terry-Humen E. No time to waste: Programs to reduce teen pregnancy among middle-school age youth. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Terry E. Trends in sex activity and contraceptive use among teens (Research brief No. 2000–03) Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock M, Herdt G. Rethinking puberty: the development of sexual attraction. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1996;5:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Norton M, Curtis T, Hill J, Schvaneveldt P, Young M. The timing of sexual intercourse among adolescents: Family, peer, and other antecedents. Youth & Society. 1997;29:54–83. [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Benson B, Galbraith K. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001;21:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mott F, Fondell M, Hu P, Kowaleski-Jones L, Menaghan E. The determinants of first sex by age 14 in a high-risk adolescent population. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Teens and Oral Sex. 2005 doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(97)80032-2. Retrieved August 19, 2008, from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/SS/SS17_OralSex.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Niccolai L, Ethier K, Kershaw T, Lewis J, Meade C, Ickovics C. New sex partner acquisition and sexually transmitted disease risk among adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeidallah D, Brennan R, Brooks-Gunn J, Kindlon D, Earls F. Socioeconomic status, race and girls’ pubertal maturation: Results from the Project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Pandina RJ, Labouvie EW, White HR. Potential contributions of the life span developmental approach to the study of adolescent alcohol and drug use: the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project, a working model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1984;14:253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett LJ, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein M, Meade C, Cohen J. Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends’ sexual behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:243–249. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Crockett L. Sexual risk taking in adolescence: The role of self-regulation and attraction to risk. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:1036–1046. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez L. Oral sex among adolescents: Is it sex or is it abstinence? Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]