Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME2), a promising anticancer agent, modulates Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma (BEAC) cell growth and behavior through cellular pathway involving β-catenin in partnership with E-cadherin, which appears to play a critical role in the induction of antitumor responses in cancer cells. We found that 2-ME2 markedly reduced the BEAC cell proliferation via regulating apoptotic machinery such as Bcl-2 and Bax. It may nullify the aggressive behavior of the cells by reducing the migratory behavior. Expressions of β-catenin and E-cadherin and binding of these two proteins is activated in a 2-ME2-dependent fashion in Bic-1 cells. Moreover, over expressions of these two proteins may be due to the stabilization of these proteins by 2-ME2. We found that 2-ME2-induced anti-migratory effects are mediated through the β-catenin -E-cadherin signaling pathways. In view of these results, we determined whether 2-ME2 reduces BEAC tumor growth. Administration of 2-ME2 significantly decreased the growth of BEAC cells xenografted on the flank of nude mice. The evidence presented points out that the impact of 2-ME2 on β-catenin-orchestrated signal transduction plausibly plays a multi-faceted functional role to inhibit the proliferation and cell migration of 2-ME2 treated malignant cells and it could be a potential candidate in novel treatment strategies for Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: 2-ME2, β-catenin, E-cadherin, Barrett’s esophageal carcinoma

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus-associated esophageal adenocarcinoma (BEAC) involves the mucosa of distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) damaged by inflammatory stimuli (1). Within the last three decades, BEAC has become one of the fastest growing tumors in the Western world (2,3). It is understood that the evolution of BEAC is a progressive multi-step process, characterized by intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, high grade dysplasia, and invasive cancer (4). Unless detected at an early, surgically resectable stage, the treatment options for inoperable esophageal cancer are limited and the results are dismal due to significant treatment-related toxicities and poor long-term survival (5,6). There is a desperate need for new and improved therapies in BEAC.

2-Methoxyestradiol (2-ME2) is an endogenous byproduct of 17β-estradiol (E2) with antitumor effects against different tumor subtypes (7). Previous work from our laboratory and others have shown that the anti-malignancy properties of 2-ME2 are not only independent of estrogen receptors (8,9), but involve activation of diverse signal transduction circuits (10-12), inhibition of tubulin polymerization (13), and G2/M phase cell cycle arrest through the disruption of mitotic spindle apparatus (7,13-16). 2-ME2 is currently undergoing phase I and II testing under the commercial name Panzem (17). Early evidence indicates that 2-ME2 is an orally bio-available drug that causes selective inhibition of tumor cell growth and proliferation without any of the usual chemotherapy-induced toxicity. As a result, the clinical interest in 2-ME2 is growing. Yet, the mechanisms of action of 2-ME2 and the molecular circuits central to the tumor-specific growth inhibitory properties of 2-ME2 are poorly understood.

Cancers arise through several cellular events. Notable among many cancers causing pathways is the deregulation of β-catenin activity that has been shown to augment tumor proliferation and survival and propagate cancer metastases (18-21). Expectably, anticancer therapies that correct the aberrant β-catenin functions are emerging as novel chemotherapeutics against a subset of tumors. To that end, in an effort to better understand 2-ME2’s antitumor mechanisms and to establish a scientific rationale that could introduce 2-ME2 as an innovative chemotherapeutic agent against BEAC, we divided our research into three parts. First, we investigated the cellular status of β-catenin in BEAC-derived Bic-1 and OE33 cells, as there is insufficient reporting onβ-catenin signaling in BE-stimulated adenocarcinogenesis. β-catenin is a ubiquitous protein that possesses dual properties of being a positive and negative regulator of cell survival and fate(18-21). Second, the cellular functions of β-catenin are dependent on its intracellular location. These reports led us to subsequently examine if β-catenin and/or its membrane-bound partner-E-cadherin participate in 2-ME2-activated signaling module in BEAC cells and, finally we investigated whether manipulation of β-catenin and E-cadherin genes by experimental techniques would have any impact on 2-ME2-directed antitumor responses. Based on these results, we designed in vivo experiments of 2-ME2 in BEAC xenografts.

Our studies categorically establish the in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy of 2-ME2 against BEAC cells and tumors. We have established that the cytotoxic effects of 2-ME2 occur in parallel with increased expression of membranous β-catenin and enhanced β-catenin-E-cadherin association at the plasma membrane of 2-ME2 treated cells. We also describe that by selecting the β-catenin-E-cadherin membranous complex as a specific drug target 2-ME2 efficiently inhibits cell motility of BEAC cells. Collectively, these studies advance our current understanding of the signaling defects underlying BE-induced carcinogenesis and act as a precursor to future translational studies involving 2-ME2 in BE-associated cancers.

Materials and Methods

Animals, Cell lines and reagents

About 8 weeks old athymic male and female mice (nu/nu) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and used for xenograft experiments. The Barrett’s esophagus-associated esophageal adenocarcinoma (BEAC) cell line-Bic-1 was a kind gift from Dr. David G. Beer, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. All other epithelial cancer cell lines derived from breast carcinoma (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231), prostate (PC-3), and pancreatic cancer (Mia-Paca2) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium ((DMEM), Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and antibiotics (Sigma). Human OE33 cell line was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and cultured in the same media described above. 2-ME2 was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Mouse monoclonal antibody against β-catenin and E-cadherin were obtained from BD Biosciences. Mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 antibody was obtained from Oncogene Research Products (Boston, MA) and Polyclonal anti-Bax and secondary antibodies, such as goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Protein A/ Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit was purchased from KPL, Inc (Gaithersburg, MD) and MEM-PERR eukaryotic membrane protein extraction reagent kit was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). All other chemical were obtained either from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Fishers Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Cell Proliferation analysis by cell counting

Tumor cells (10,000 cells per well in 3ml medium) were plated onto 6-well tissue culture plates containing DMEM with 10% FBS. After reaching ~60-70% confluent growth, cells were treated with different dosages of 2-ME2 for 24h. After completion of the experiments, cells were stained with 0.2% trypan blue solution for 5 min and counted the viable cells (unstained) using automatic cell counter (Nexcelom). In each experiment set, cells were plated in quadruplicates.

Apoptosis Assay

Photometric enzyme immunoassay for quantitative in vitro determination of apoptotic cell death was determined as described previously (16).

Xenograft model

Bic-1 cells (2.5 × 106) were injected into the right hind leg of each mouse for the development of tumor. The mice were divided into two groups (four mice per group) with a control group and 2-ME2 treatment group. To remove any gender differences in 2-ME2 actions on BEAC xenografts, we included 2 female and 2 male mice per group. The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at VAMC, Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City VAMC Animal Research Committee approved all the animal experiments. To determine the inhibitory effect of 2-ME2 on tumor volume, nude mice bearing xenografts of Bic-1 cells were given 2-ME2 doses (75 mg/kg/day) by orogastric feeding or vehicle (control) after tumor growth of ~100mm3 was noted in the hind leg of animals. The doses of 2-ME2 have been previously reported in the literature by us (15,21) and others (22). 2-ME2 was dissolved in DMSO+peptamen (milk) in 1:2 ratio. We used DMSO+peptamen (1:2 ratio) as a vehicle control. Tumor growth was monitored for 16 days by measuring two perpendicular diameters twice weekly. Tumor volume was calculated according to the formula V= (a × b2)/2, where a and b are the largest and smallest diameters, respectively.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration assays were performed as described earlier (Banerjee 2008). Briefly, Bic-1 cells (2−104 cells/well) seeded on 8.0μm pore transwell filter insert (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). To the upper chamber, 5μM concentration of 2-ME2 was added to the medium according to the experimental design. Cell migration was allowed to proceed for 24 h. After 24 h incubation, the cells of the upper side of the membranes were removed by gently wiping with a cotton swab, and the cells that had migrated to the lower surface of the membranes were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa and counted.

Cell lysis, immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting

Cells were treated for the indicated times with 5 μM of 2-Methoxyestradiol, unless stated otherwise, and lysed in phosphorylation lysis buffer as previously described (22-24). Immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting using an ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) method were performed as previously described (22-24).

shRNA Insert Preparation and Transfection in Bic-1 Cells

E-cadherin and β-catenin specific shRNA and mismatched shRNA were designed, synthesized and cloned into pSilencer 1.0-U6 expression following the instruction provided by the manufacturer (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) and as previously described (23,24). E-cadherin and β-catenin-specific shRNA sequences are provided in Supl. Table 1. Expression vectors, with mismatched or specific shRNA inserts, were transformed into the competent cells, DH5α. Plasmids were purified by QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). The transfection procedure was the same as that described previously (23,24).

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by using the paired Student’s two-tailed t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

2-ME2 inhibits the proliferation of Barrett’s Adenocarcinoma cells and activates apoptosis

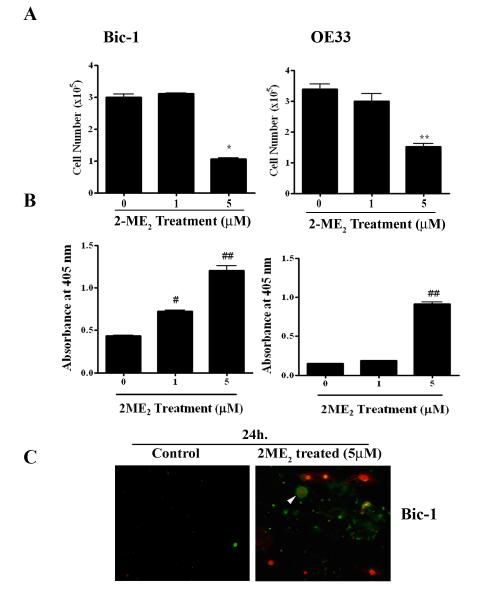

The objective of this study was to evaluate if 2-ME2 is able to exhibit an anti-proliferative effect on Bic-1 and OE33 cells. To test the hypothesis, Bic-1 cells were exposed to 1 and 5 μM doses of 2-ME2 for 24h. Cell numbers were counted electronically using Cellometer Auto T4 Cell Counter (Nexcelom) by trypan blue method. Compared with untreated controls, 2-ME2 significantly decreased Bic-1 cell numbers with 5 μM dose at 24 h (Fig. 1A). 2-ME2 also produces similar cytolytic effects at 5 μM dose on OE33 cells at 24 h (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of 2-Methoxyestradiol (2-ME2) on BEAC cells.

A. Bic-1 and OE33 cells were incubated with various concentrations of 2-ME2 for 24h or left untreated. Cell numbers were counted electronically using Cello meter Auto T4 Cell Counter. Data is displayed as mean ± SD in each case. P value was determined by Student’s t-test. *p<0.05 vs controls and **p<0.001 vs controls.

B. Bic-1 and OE33 cells were incubated with various concentrations of 2-ME2 for 24 h and apoptotic cell death was determined using cell-death detection ELISA kit. Data is displayed as mean ± SD in each case. P value was determined by Student’s t-test. #p<0.01 vs controls and ##p<0.001 vs controls.

C. Immunofluorescence images of Bic-1 cells treated with or without 5 μM of 2-ME2 for 24 h. Cells that have bound Annexin V-FITC show green staining in the plasma membrane, which signify early apoptosis. Cells that have lost membrane integrity will show red staining (PI) throughout the nucleus and a halo of green staining (FITC) on the cell surface (arrow head), while FITC Annexin V negative and PI positive (red) indicate late stage apoptosis and death. Viable cells are negative for FITC Annexin V binding and PI staining (control).

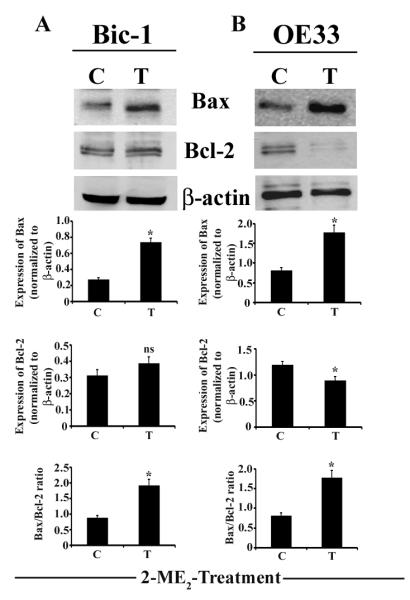

To study whether inhibition of cell growth by 2-ME2 is due to the apoptosis, we performed ELISA-based apoptosis assay. We found that 2-ME2 (5 μM) significantly enhanced the apoptotic cell death in both Bic-1 and OE33 cells (Fig. 1B). Next, we measured the expression of annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), considered to be an early and late apoptotic marker, respectively. As shown in Figure 1C, 2-ME2-treated Bic-1 cells show pronounced immunoflorescence staining with annexin V and PI, indicating that both early and late cell death programs are activated within 24 h of 2-ME2 treatment. Since induction of pro-apoptotic Bax and inhibition of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 has previously been shown to activate the cellular suicide programs (16,25), we, subsequently, sought to determine the levels of Bax and Bcl-2 protein expression in Bic-1 and OE33 cells following 2-ME2 (5 μM) treatment. We found that Bax and Bcl-2 proteins were differentially expressed in the total lysates of Bic-1 and OE33 cells and the ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 was significantly increased in treated groups (Fig. 2), which is the hallmark of apoptosis (26). These findings suggest that the common denominator in 2-ME2-triggerred programmed cell death is elevating of the Bax/Bcl-2 protein ratio.

Figure 2. 2-ME2 modulates Bax and Bcl-2 expression profiles in BEAC cells.

Equal amounts of total cell lysates (50μg/lane) were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Bax or Bcl-2. The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed with an antibody against β-actin as a control for loading. Quantification of each band was performed by densitometry analysis software. Significant difference between untreated (C) and 2-ME2 treated (T) samples is indicated by *p<0.01, ns, non significant.

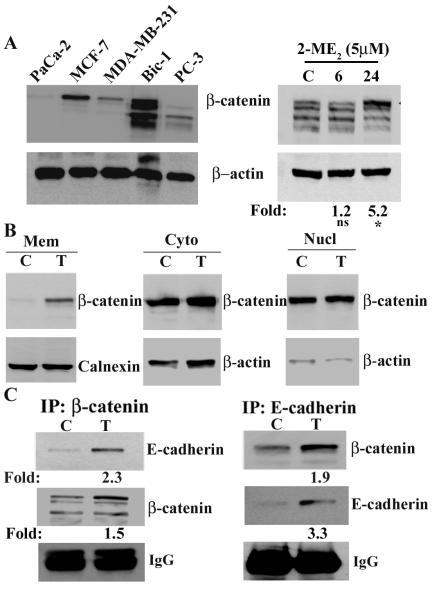

Expression pattern of β-catenin and its regulation by 2-ME2 in BEAC-derived Bic-1 and OE33 cells

Ample studies have shown the involvement of β-catenin overexpression in the development of various cancers by increased tumor proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis (18-21). Our goal was to evaluate whether β-catenin could be a target molecule of 2-ME2 to exert its catastrophic effect on Barrett’s adenocarcinoma cells. To do so, we first determined the level of β-catenin protein in Bic-1 cells jointly with a panel of other adeno-cancer cell lines, including breast carcinoma (MCF-7; MDA-MB-231), prostate (PC-3), and pancreatic (Mia-Paca2) cancer cells, by immuno-Western blot analysis using a mouse monoclonal against β-catenin. As shown in Figure 3A, the highest levels of β-catenin protein were observed in the lysates of MCF-7 breast cancer cells (lane 2) and Bic-1 cells (lane 4). Contrastingly, there was an insignificant β-catenin expression in the whole cell lysates of invasive carcinoma cells, including the Mia-Paca2 cells (lane 1), PC-3 cells (lane 5), and MDA-MB-231 cells (lane 3). In studies where β-catenin expression was evaluated in Bic-1 cell lysates, we consistently found β-catenin expressed as a multimeric protein complex, which is in agreement with previous work (27).

Figure 3. 2-ME2 induces total and membranous β-catenin expression in Bic-1 cells.

A. Total β-catenin expression was detected in different cancer cell line extracts by Western blotting using β-catenin specific monoclonal antibodies (left panel) and 2-ME2-induced alteration of total β-catenin protein levels in Bic-1 cell extracts (right panel). Bic-1 were incubated with 2-ME2 (5μM) for the indicated times. Equal amounts of total cell lysates (100μg/lane) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody against β-catenin. The blots were stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody as a control for loading. *p<0.05 vs controls, ns, non-significant.

B. Distribution of β-catenin protein in different cellular compartments of Bic-1 cells before and after exposure to 5μM of 2-ME2 for 24h. Cells were fractionated into membranous (Mem), cytosolic (Cyto) and nuclear (Nucl) fractions. Equal aliquots of all three cellular fractions were resolved by immunoblotted for β-catenin. Subsequently, the blot was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody as a control for loading of cytosolic and nuclear fractions and calnexin antibody as a control for loading of membrane fraction.

C. Increased interactions of β-catenin and E-cadherin were observed in Bic-1 cells following 2-ME2 stimulation. Cells were treated with 5μM 2-ME2 for 24 h or left untreated. Whole-cell lysates were harvested and used for IP/WB analysis with antibodies as indicated. Immunoprecipated β-catenin and E-cadherin have been normalized to IgG and their fold inductions are shown in the figure.

The differential accumulation of β-catenin within intracellular compartments has been linked to tumor formation (18-21,28), as well as a positive regulator of apoptosis and cellular differentiation (29,30). These reports led us to investigate whether 2-ME2 would alter the cellular levels of β-catenin in Bic-1 cell lysates to achieve its antitumor effects. We found that 5 μM 2-ME2 treatment markedly increased the total cellular protein levels of β-catenin by 5.2-fold at 24 h in Bic cells (Fig. 3A, right panel). This was an unexpected result as we speculated that inhibition of β-catenin by 2-ME2 would constitute the fundamental molecular mechanism underlying the anti-cancer actions of 2-ME2 on cells that express abundant β-catenin.

As a result of our unforeseen observations showing that 2-ME2 effectively induces rather than reduce the total intracellular β-catenin protein expression in Bic-1 cell lysates (Fig. 3A), we hypothesized that 2-ME2 treatments may change the β-catenin distribution intercellularly to mediate its antiproliferative actions. By function, the membrane-bound β-catenin acts in partner with E-cadherin to facilitate cytoskeletal attachment and thereby has antitumor properties, while nuclear-associated β-catenin binds with Tcf-3/4 and activates gene expression involved in tumor multiplication and spread (19,20,20,21,28). With that background in view and to test our objective, Bic-1 cells were stimulated for 24 h with 5 μM of 2-ME2; following that, the quantitative subfractionation of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane-associated β-catenin was studied using immuno-Western blotting. In untreated Bic-1 cells, high baseline levels of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin was observed but the membrane-bound β-catenin was undetectable (Fig. 3B). Upon stimulation of Bic-1 cells with 5 μM of 2ME2, β-catenin expression was significantly increased in the membrane-fraction, while the β-catenin levels in cytosolic and nuclear fractions were unchanged (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data indicate that 2-ME2 exclusively upregulates β-catenin expression in Bic-1 cells at the plasma membrane fractions, and that event could be responsible for the growth inhibitory properties of 2-ME2 on malignant cells.

Multiple studies have shown that the accumulated β-catenin in the nucleus needs to bind to its cognate receptor, Lef/Tcf transcription factors, to activate target genes (18-21,28). Therefore, the status of Lef/Tcf was determined in 2-ME2 exposed or unexposed Bic cells. Our results illustrate that Tcf-3/4 protein levels remain unaltered even after 24 h of 2-ME2 treatment (Supl. Fig.1).

β-catenin binds to E-cadherin in a 2-ME2-dependent fashion

Anti-cancer strategies that modulate the subcellular distribution of β-catenin-E-cadherin to promote cell-to-cell adhesion are increasingly being viewed as novel, especially in the setting of invasive cancers with deregulated β-catenin signaling (31-34). Within that context and to further expand on our findings that 2-ME2 induces preferential expression of membranous β-catenin in Bic-1 cells, we explored the hypothesis whether 2-ME2 treatments could promote β-catenin-E-cadherin binding in Bic-1 cells. To test this, we conducted the co-immunoprecipitation experiments on membrane extracts of Bic-1 cells that were incubated with either β-catenin or an E-cadherin antibody for 24 h. We found that β-catenin-E-cadherin binding enhances significantly in 2-ME2-exposed cells, while binding of these two proteins was undetected or minimally detected in membranous lysates of unstimulated Bic-1 cells (Fig. 3C).

2-ME2 attenuates the motility/migration of Bic-1 cell that is enhanced by small interfering RNA-induced silencing against E-cadherin and β-catenin

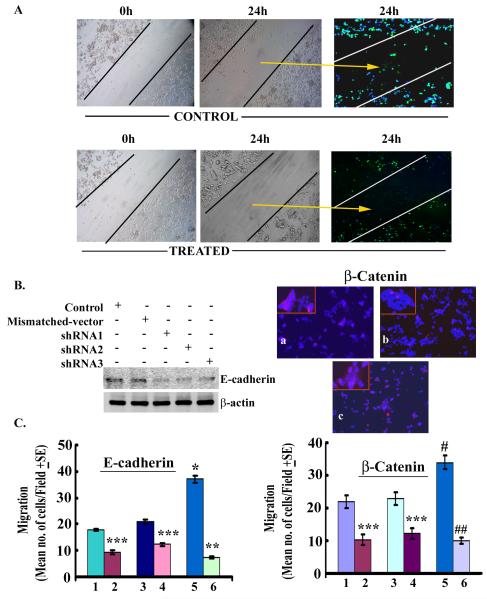

As noted earlier, the augmentation of β-catenin-E-cadherin binding and/or correction of E-cadherin deficiency in tumor cells lead to inhibition of tumor cell migration, a hallmark of invasive phenotype. Thus, in this study we determined if 2-ME2 modulates the migration of tumor cells. To test this, we designed cell culture experiments to optically observe the movement of Bic-1 cells across a cell-free zone created using a “scratch” technique. As shown in Figure. 4A, under serum free conditions Bic-1 cells demonstrate migratory properties at 24 h by voyaging into the cell-free zone created by the scratch. In contrast, the width of the scratch-induced cell-free zone remained relatively unperturbed in 2-ME2-treated Bic-1 cells, signifying 2-ME2-induced arrest on cell motility.

Figure 4. Contribution of E-cadherin and β-catenin to 2-ME2-mediated effects on Bic-1 cell motility.

A. Representative images of the scratch test show untreated Bic-1 cells grown in serum-free conditions (control) at 0 h or 24 h after scratch and 2-ME2 treated Bic-1 cells at similar time points. In the control test the distance between the borderlines becomes infiltrated with motile Bic-1 cells 24 h after scratch, while it is still preserved in 2-ME2 treated samples (middle panel). Immunofluorescence images (right panel) of GFP-tagged Bic-1 cells in 2-ME2-treated and untreated cultures.

B. Reduced expression of E-cadherin (left panel) and β-catenin (right panel) by gene-directed shRNAs. E-cadherin level was determined by Western blotting in mismatched shRNA transfected and E-cadherin shRNA-transfected Bic-1 cells. β-catenin protein expression in Bic-1 cells was analyzed by immunoflorescence technique using a monoclonal antibody against β-catenin (red). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). a. mismatched-shRNA transfected cells, b. β-catenin-shRNA transfected cells and c. β-catenin-shRNA transfected cells and 2-ME2 (5μM) treated cells.

C. Contribution of E-cadherin (left panel) and β-catenin (right panel) to 2-ME2-mediated effects on Bic-1 cell migration. E-cadherin or β-catenin-transfected Bic-1 cells were placed in the upper chamber of Boyden chamber in the presence or absence of 2-ME2 and cell migration towards serum was allowed to proceed for 24 h. Treatment series are: control (1), control+2-ME2 (2), scrambled control (3), scrambled control+2-ME2 (4), E-cadherin/β-catenin-shRNA (5) and E-cadherin/β-catenin-shRNA+2-ME2 (6). The results reflect the mean (± SD) number of migrated cells to the undersurface of the matrigel membrane from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs controls; **p<0.01 vs shRNA; ***p<0.001 vs control/scrambled control.

In the in vivo setting, increased tumor cell mobility combined with an enhanced capacity of the tumor cells to invade across the basement membrane, which is facilitated by proteosomal degradation of matrigel by cancer cells, underlies the development of tumor metastases. Hence, after demonstrating the impact of 2-ME2 on Bic-1 cell motility we choose to perform matrigel assays to investigate the transmigratory capacity of 2-ME2 treated and untreated Bic-1 cells across an intact matrigel membrane. In parallel, we determined the role of β-catenin and its binding partner, E-cadherin, on the migration of Bic-1 cells. First, we transiently transfected Bic-1 cells with pSilencer vectors containing small interfering RNA (shRNA) constructs against E-cadherin or scrambled DNA for 24h. Transfection efficiency was determined by immunoblotting. We found that all three synthetic shRNA oligonucleotides targeted against different sequences within the coding region of the human E-cadherin gene (designated shRNA E-cad#1-3), yielded marked reduction in E-cadherin protein expression as compared to scramble-shRNA or native Bic-1 cells (Fig. 4B). Based on the degree of E-cadherin inhibition measured by western blotting, we selected the most potent shRNA-E-cad#1 clones for subsequent biological studies. shRNA-transfected Bic-1 cells (15,000 per well) were seeded on upper chamber of a modified Boyden chamber containing regular DMEM in the presence or absence of 2-ME2 (5 μM) for 24 h. Subsequently, cell migrations were studied according to our previous method (35). Upon shRNA-mediated inhibition of E-cadherin expression, in the absence of 2-ME2, the migratory mode of shRNA-transfected-Bic-1 cells at 24 hours was augmented as compared to mismatch-vector transfected and naïve Bic-1 cells, respectively (Fig. 4B). These shRNA experiments indicate that down-regulation of E-cadherin boosts the trans-basement membrane excursion of Bic-1 cells. In contrast, the migration of 2-ME2 (5 μM) exposed cells was appreciably decreased at 24 h compared to 2-ME2 unexposed cells (Fig. 4B. Next, we designed to examine the impact of β-catenin silencing by shRNA on cell migration. We found silencing of β-catenin gene in Bic-1 cells promoted their cell migration as compared to the corresponding controls (Fig. 4C). However, this shRNA-induced migration can be significantly abolished by 2-ME2-exposure (Fig. 4C). Collectively, our studies categorically establish that 2-ME2 is a very potent anti-invasive chemotherapy drug in blocking the invasive behavior of Bic-1 cells.

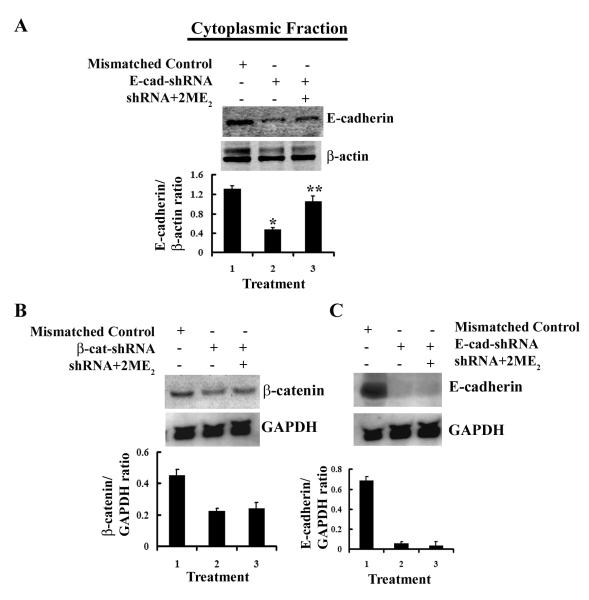

Repression of E-cadherin and β-catenin by shRNA is restored by 2-ME2 treatment

From previous studies results we reasoned whether 2-ME2 could restore the protein levels by overcoming the shRNA-directed repression of E-cadherin and β-catenin genes in Bic-1 cells. As shown in Figure 4B, β-catenin protein levels enhanced significantly in 2-ME2-exposed β-catenin-shRNA transfected Bic-1 cells at 24h. Similar results were obtained when E-cadshRNA-transfected cells were treated with 2-ME2 for 24h (Fig. 5A). Altogether, these results support the claim that the repressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin protein by shRNAs are restored by 2-ME2.

Figure 5. 2-ME2 restores E-cadherin protein in shRNA-transfected Bic-1 cells.

A. Transfected Bic-1 cells were treated with 5μM of 2-ME2 for 24 h or left untreated. Equal amounts of cell lysates (100μg/lane) were analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against E-cadherin. Quantification of each band was performed by densitometry analysis software. * p<0.005 vs mismatched controls. ** p<0.01vs shRNA alone transfected cells.

B. E-cadherin and β-catenin shRNA transfected Bic-1 cells were exposed to 5 μM of 2-ME2 for 24 h, and β-catenin (left panel) and E-cadherin (right panel) mRNA expressions were determined by northern blotting using nonradioactive DIG-labeled probe. GAPDH is used as loading control.

Effect of 2ME2 on β-catenin and E-cadherin mRNA

To investigate the mechanisms responsible for 2ME2-induced up-regulation of E-cadherin and β-catenin, we used the shRNA constructs designed for our earlier experiments to first knockdown β-catenin and/or E-cadherin genes in the Bic-1 cells. The shRNA transfected cells were then grown in either the presence or absence of 2-ME2 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. Total mRNA levels of β-catenin and E-cadherin were determined by Northern blot analysis. As depicted in Figure 5B, 2-ME2 is unable to rescue the shRNA-mediated inhibition of β-catenin and E-cadherin mRNA expression in these cells. Therefore, this study suggests that 2-ME2 mediated upregulation of these proteins expressions could be the result of stabilization these proteins. However, further studies are warranted.

2-ME2 inhibits the growth of BEAC xenografts

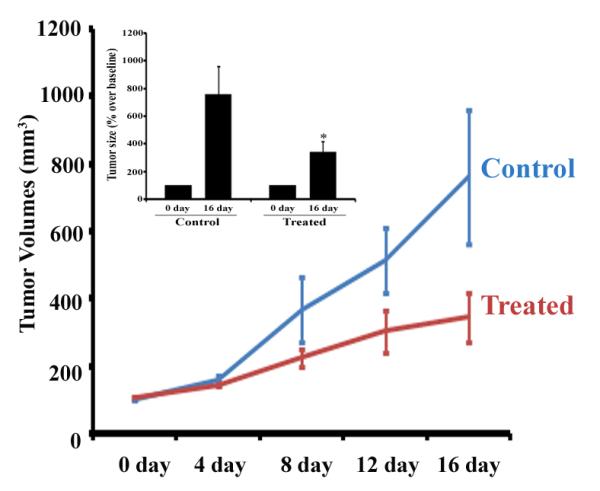

When Bic-1 cells are implanted into nude mice they are remarkably tumorigenic. To illustrate that point, measurable xenografts were noted within a week of Bic-1 inoculation into the hind leg of nude mice, whereas OE33 cells produced comparable xenografts at 3-4 weeks after implantation (Supl. Fig. 2). These studies suggest that both cell lines are capable of producing xenografts in immunocompromised mice, although at varying time points. Given the rapid tumor forming potential of Bic-1 cells, we subsequently sought to determine the in vivo effects of 2-ME2 on Bic-1-generated xenografts. To determine the inhibitory effect of 2-ME2 on tumor volume, four athymic nude (2 female and 2 male) mice in each group were treated with or without 2-ME2 (75 mg/kg/day) after bearing a minimum xenograft size of ~100mm3 (Day 0). Tumor growth was monitored for 16 days by measuring two perpendicular diameters twice weekly. Our data shows that 2-ME2 significantly inhibits the growth of Bic-1-induced tumors in nude mice (Fig. 6). However, like in humans, interanimal variability was noted in tumor responses (range of tumor reduction was 38-71%).

Figure 6. 2-ME2 inhibits the growth of BEAC xenografts.

For in vivo studies, nude mice bearing xenografts of Bic-1 cells were given 2-ME2 (75 mg/kg/day) by orogastric feeding or vehicle (control). Tumor growth was monitored for 16 days by measuring two perpendicular diameters twice weekly. Tumor volumes of the 2-ME2 treated (T) group versus the vehicle (C) group on the indicated days were measured and were plotted against time. Bar diagram representation of the tumor size at 0 day and 16 day after treatment has been shown in right panel (inset). Column, means of four mice in each group; bars, SD. *p<0.001.

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in Barrett’s esophagitis-associated adenocarcinoma (BEAC) have lagged behind other cancers due to the paucity of reliable in vitro and in vivo models. Although previous studies have established Bic-1 and OE33 cells as BEAC-derived cell lines, there is limited information characterizing the ongoing molecular events in these cells. Previous studies suggest that both Bic-1 and OE33 cells have mutated p53 gene (36,37). Despite that concordance in p53 status, there are molecular and behavioral differences between Bic-1 and OE33 cells. We found a striking difference in the level of villin expression in Bic-1 (high expression) and OE33 (low expression) cells (Supl. Fig.3). Villin is a Ca2+-dependent actin binding protein and a useful marker for intestinal-cell differentiation and for recognition of malignant tumors of colonic origin (38). Therefore, our observations make us speculate two possible scenarios to explain the differential expression of villin in BEAC cell lines. First, in the villin overexpressing Bic-1 cells, the microvilli architecture could be better preserved. Second, while taking into account the epithelial heterogeneity of BEAC, the presence of colonocyte-like cells in Bic-1 may be responsible for the preferential expression of villin in Bic-1 cells. Moreover, when Bic-1 cells are implanted into nude mice they become remarkably tumorigenic within a week. OE33 cells also produce measurable xenografts, however, at 3-4 weeks after implantation (Supl. Fig.2). Collectively, these studies suggest that these two cell lines are phenotypically and behaviorally distinct, and therefore, we selected these two cell lines for the present study.

The poor understanding of BEAC pathobiology is partly responsible due to the meager therapeutic targets available against BEAC. Research efforts geared to introduce targeted and novel treatments are therefore desperately needed to improve patient outcomes in BEAC (5,6). 2-ME2 is being increasingly recognized as a novel chemotherapy drug due to its propensity to activate a wide array of anti-cancer targets with a relative sparing of the normal tissues(17,39,40). We have carried out studies to determine the therapeutic efficacy of 2-ME2 against EAC and to identify surrogate biomarkers which would be useful in predicting its anti-cancer responses. Our studies clearly establish 2-ME2, at a concentration of 5 μM, attenuated the in vitro proliferation of BEAC-derived Bic-1 and OE33 cells through the induction of apoptosis. Differential regulations of Bax and Bcl-2 may promote apoptosis (Figs. 1 and 2).

The growth of Bic-1 xenografts was significantly slower in the 2-ME2 group than in animals treated with vehicle (control) (Fig. 6). This effect is, however, variable. Therefore, 2-ME2 may prove to be a therapeutic agent for patients with BEAC if its poor bioavailability in humans as well in animals is addressed. Design of new formulations of 2-ME2 to improve its bioavailability is ongoing in our laboratory.

Sequential loss of membranous β-catenin and E-cadherin expression along the metaplasia–dysplasia–cancer sequence has been previously reported in clinical specimens (41). It is now customary knowledge that the pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by inflamed cells of BE augment the nuclear translocation of β-catenin that eventually culminates in neoplastic transformation by transactivation of oncogenes Anderson, 2006 4931 /id;Tselepis, 2003 4883 /id}. Given the importance of β-catenin nuclear translocation as a hallmark of neoplastic transformation, we determined whether 2-ME2 can be a regulator of this translocation event. We therefore examined the expression profiles of β-catenin in BEAC cells before and after the exposure of 2-ME2. We found constitutive expression of nuclear and cytosolic, instead of membranous, β-catenin in unexposed Bic-1 cells, while membranous fraction of β-catenin accumulated remarkably in 2-ME2-exposed Bic-1 cells (Fig. 3). Membrane-bound β-catenin plays a vital role in cell adhesion machinery, which may be particularly relevant to the prevention of cancer progression via the induction of mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET)(42-44). Therefore, we anticipate that 2-ME2-induced accumulation of β-catenin in the membrane may diminish the aggressive behavior of the BEAC cells.

β-catenin mediated cell-cell adhesion is a coordinated process that is accomplished by molecular interactions with E-cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule that acts as a tumor suppressor inhibiting the invasive front and it is frequently down regulated in aggressive cancer cells (31-34,44,45). Our results demonstrate that 2-ME2 treatment promotes E-cadherin expression and its association with β-catenin in the plasma membrane fraction of Bic-1 cells (Fig. 5A and B). These studies strengthen our above hypothesis and suggest that 2-ME2 may be able to restore the cell adhesion property of the BEAC cells.

The next logical step was to perform studies that would demonstrate the biological relevance of membranous β-catenin-E-cadherin induction in 2-ME2 treated cells. The picture evolving from our transwell motility assays is that contrary to the motile and invasive phenotype of the 2-ME2-unexposed cells, the 2-ME2-treated cells exhibit a drastic inhibition of cellular migration in E-cadherin and β-catenin deficient Bic-1 cells. Loss of E-cadherin expression promotes cancer dissemination through local proteolysis and via enhanced motility and migration of cancer cells across the matrigel basement membrane (46-49). However, the observation made in our shRNA knocking-down experiments is that β-catenin silencing leads to increased cell motility in a BEAC model that is original and previously unreported. These findings underscore our argument that the assembly and function of the β-catenin and E-cadherin epithelial adhesion molecules are mutually supportive in Bic-1 cells. 2-ME2, by restoring the expression level of β-catenin and E-cadherin transmembrane adhesion molecules in both native and shRNA-transfected Bic-1 cells (Fig. 4), abrogates their motile and migratory behavior and acts as a potent anti-invasive drug.

Since we found that 2-ME2 enhances membrane β-catenin and E-cadherin levels in these cells even after silencing of the expressions of these two molecules, we sought to determine how does 2-ME2 nullifies the effect of shRNA mediated down regulation of β-catenin and E-cadherin expression? We provide evidence to suggest that the induction of membranous β-catenin protein and E-cadherin by 2-ME2 is accomplished by protein stabilization (Fig. 5). To the best of our knowledge, this study provides a firsthand report of post-transcriptional mechanisms involved in 2-ME2-mediated protein stability of β-catenin-E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion complex.

In conclusion, after reviewing the current body of evidence, our results are the first to describe the in vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of 2-ME2 on BEAC-derived cell lines and xenografts, respectively. Since there has not been an appreciable improvement in the overall survival of patients with BEAC over the last decade (5,6), there is an urgent need to investigate effective and less-toxic chemotherapeutic options. Our data provides solid scientific merit for the broader use of 2-ME2 in chemoprevention and treating patients with BEAC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by VA VISN 15 Grants (SK, KD and SM), a NIH COBRE awards 1P20 RR15563 (SK and SB), Merit review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (SK, SB and SKB), and NIH grants CA87680 (SKB).

Abbreviations

- BEAC

Barrett’s esophagus adenocarcinoma

- 2-ME2

2-Methoxyestradiol

- β-catenin

beta-catenin

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- CRC

colorectal cancer

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Hamilton SR, Smith RR, Cameron JL. Prevalence and characteristics of Barrett esophagus in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or esophagogastric junction. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:942–8. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossentino MJ, Wong RK. Barrett’s esophagus and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003;14:128–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casson AG, Williams L, Guernsey DL. Epidemiology and molecular biology of Barrett esophagus. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;17:284–91. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McManus DT, Olaru A, Meltzer SJ. Biomarkers of esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1561–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooney MM. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:230–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mooberry SL. Mechanism of action of 2-methoxyestradiol: new developments. Drug Resist Updat. 2003;6:355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoubine MN, Weston AP, Johnson DC, Campbell DR, Banerjee SK. 2-methoxyestradiol-induced growth suppression and lethality in estrogen-responsive MCF-7 cells may be mediated by down regulation of p34cdc2 and cyclin B1 expression. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:639–46. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee SN, Sengupta K, Banerjee S, Saxena N, Banerjee SK. 2-methoxyestradiol exhibits a biphasic effect on VEGF-A in tumor cells and upregulation is mediated through ER-α: A possible signaling pathway associated with the impact of 2-ME2 on proliferative cells. Neoplasia. 2003;5:417–26. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Konishi N. Roles of p38- and c-jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated pathways in 2-methoxyestradiol-induced p53 induction and apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1067–75. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davoodpour P, Landstrom M. 2-Methoxyestradiol-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells requires Smad7. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14773–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sattler M, Quinnan LR, Pride YB, et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol alters cell motility, migration, and adhesion. Blood. 2003 doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Amato RJ, Lin CM, Flynn E, Folkman J, Hamel E. 2-Methoxyestradiol, an endogenous mammalian metabolite, inhibits tubulin polymerization by interacting at the colchicine site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3964–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, Lavallee TM, et al. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:363–75. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Stable C. 2-Methoxyestradiol and paclitaxel have similar effects on the cell cycle and induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray G, Dhar G, Van Veldhuizen PJ, et al. Modulation of cell-cycle regulatory signaling network by 2-methoxyestradiol in prostate cancer cells is mediated through multiple signal transduction pathways. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3703–13. doi: 10.1021/bi051570k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James J, Murry DJ, Treston AM, et al. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of 2-methoxyestradiol alone or in combination with docetaxel in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:41–8. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson WJ, Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WN, Pignatelli M. E-cadherin-catenin cell-cell adhesion complex and human cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:992–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens J, Lustig B. The Wnt connection to tumorigenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:477–87. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041815jb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kambhampati S, Li Y, Verma A, et al. Activation of protein kinase C delta by all-transretinoic acid. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32544–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta K, Banerjee S, Dhar K, et al. WISP-2/CCN5 is involved as a novel signaling intermediate in phorbol ester-protein kinase Cα-mediated breast tumor cell proliferation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10698–709. doi: 10.1021/bi060888p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee S, Sengupta K, Dhar K, et al. Breast cancer cells secreted platelet-derived growth factor-induced motility of vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated through neuropilin-1. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:871–80. doi: 10.1002/mc.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins: regulators of chemoresistance in cancer. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82-83:155–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isenmann S, Wahl C, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Bahr M. Up-regulation of Bax protein in degenerating retinal ganglion cells precedes apoptotic cell death after optic nerve lesion in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1763–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhar G, Banerjee S, Dhar K, et al. Gain of oncogenic function of p53 mutants induces invasive phenotypes in human breast cancer cells by silencing CCN5/WISP-2. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4580–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peifer M, Polakis P. Wnt signaling in oncogenesis and embryogenesis--a look outside the nucleus. Science. 2000;287:1606–9. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olmeda D, Castel S, Vilaro S, Cano A. Beta-catenin regulation during the cell cycle: implications in G2/M and apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2844–60. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim K, Pang KM, Evans M, Hay ED. Overexpression of beta-catenin induces apoptosis independent of its transactivation function with LEF-1 or the involvement of major G1 cell cycle regulators. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3509–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce M, Wang C, Stump M, Kamb A. Overexpression of the beta-catenin binding domain of cadherin selectively kills colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:229–37. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadot E, Simcha I, Shtutman M, Ben Ze’ev A, Geiger B. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by cadherin derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15339–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottardi CJ, Wong E, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin suppresses cellular transformation by inhibiting beta-catenin signaling in an adhesion-independent manner. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1049–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orsulic S, Huber O, Aberle H, Arnold S, Kemler R. E-cadherin binding prevents beta-catenin nuclear localization and beta-catenin/LEF-1-mediated transactivation. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 8):1237–45. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell IG, Qiu W, Polyak K, Haviv I. Breast-cancer stromal cells with TP53 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1634–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc086024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahidhara RS, De Oliveira PE Queiroz, Kohout J, et al. Altered trafficking of Fas and subsequent resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis occurs by a wild-type p53 independent mechanism in esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Res. 2005;123:302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Zhao X-H, Wang Z-J. Flavones and flavonols exert cytotoxic effects on a human oesophageal adenocarcinoma cell line (OE33) by causing G2/M arrest and inducing apoptosis. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:2042–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valette A, Gas N, Jozan S, Roubinet F, Dupont MA, Bayard F. Influence of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate on proliferation and maturation of human breast carcinoma cells (MCF-7): relationship to cell cycle events. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1615–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahut WL, Lakhani NJ, Gulley JL, et al. Phase I clinical trial of oral 2-methoxyestradiol, an antiangiogenic and apoptotic agent, in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:22–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.1.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweeney C, Liu G, Yiannoutsos C, et al. A phase II multicenter, randomized, double-blind, safety trial assessing the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of oral 2-methoxyestradiol capsules in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6625–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koppert LB, Wijnhoven BP, van Dekken H, Tilanus HW, Dinjens WN. The molecular biology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:169–90. doi: 10.1002/jso.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagotto F, Gumbiner BM. Cell contact-dependent signaling. Dev Biol. 1996;180:445–54. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84:345–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larue L, Bellacosa A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:7443–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fagotto F, Funayama N, Gluck U, Gumbiner BM. Binding to cadherins antagonizes the signaling activity of beta-catenin during axis formation in Xenopus. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1105–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wijnhoven BP, Pignatelli M, Dinjens WN, Tilanus HW. Reduced p120ctn expression correlates with poor survival in patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:116–23. doi: 10.1002/jso.20344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Washington K, Chiappori A, Hamilton K, et al. Expression of beta-catenin, alpha-catenin, and E-cadherin in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:805–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey T, Biddlestone L, Shepherd N, Barr H, Warner P, Jankowski J. Altered cadherin and catenin complexes in the Barrett’s esophagus-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence: correlation with disease progression and dedifferentiation. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:135–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swami S, Kumble S, Triadafilopoulos G. E-cadherin expression in gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical and immunoblot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1808–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.