Abstract

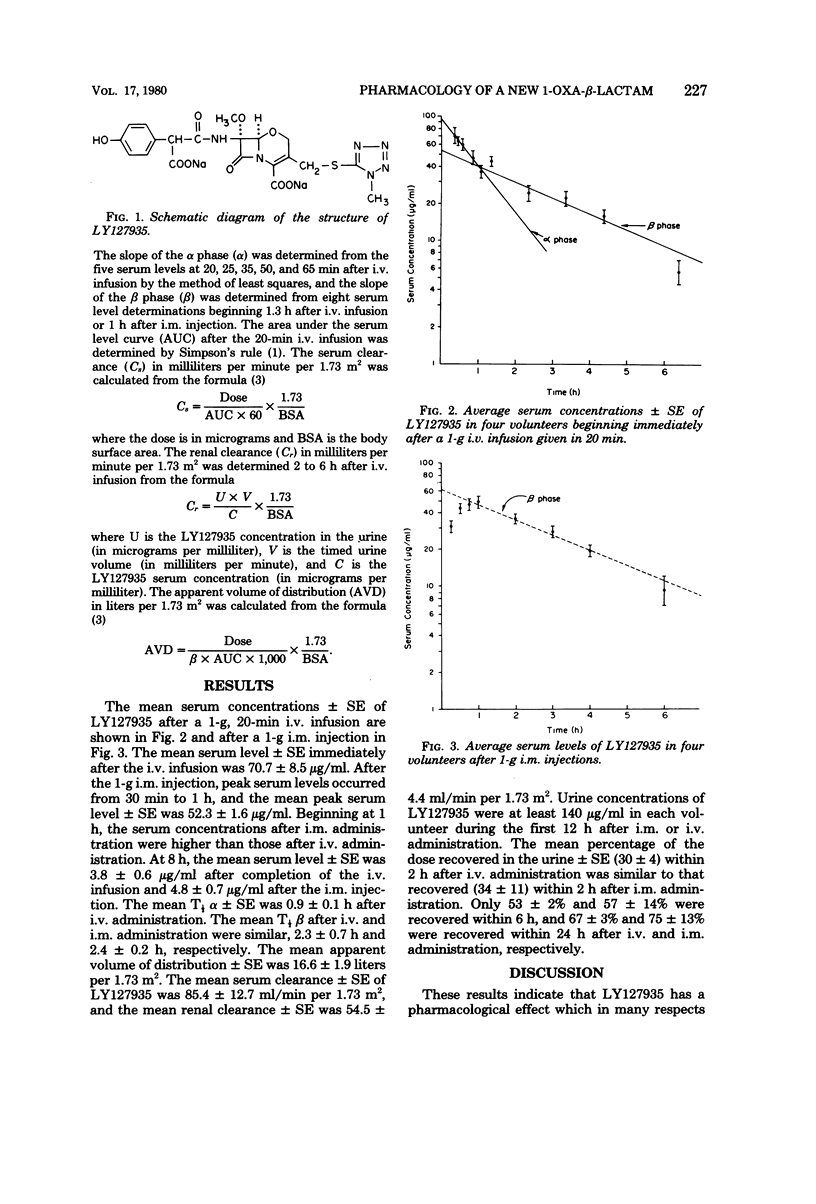

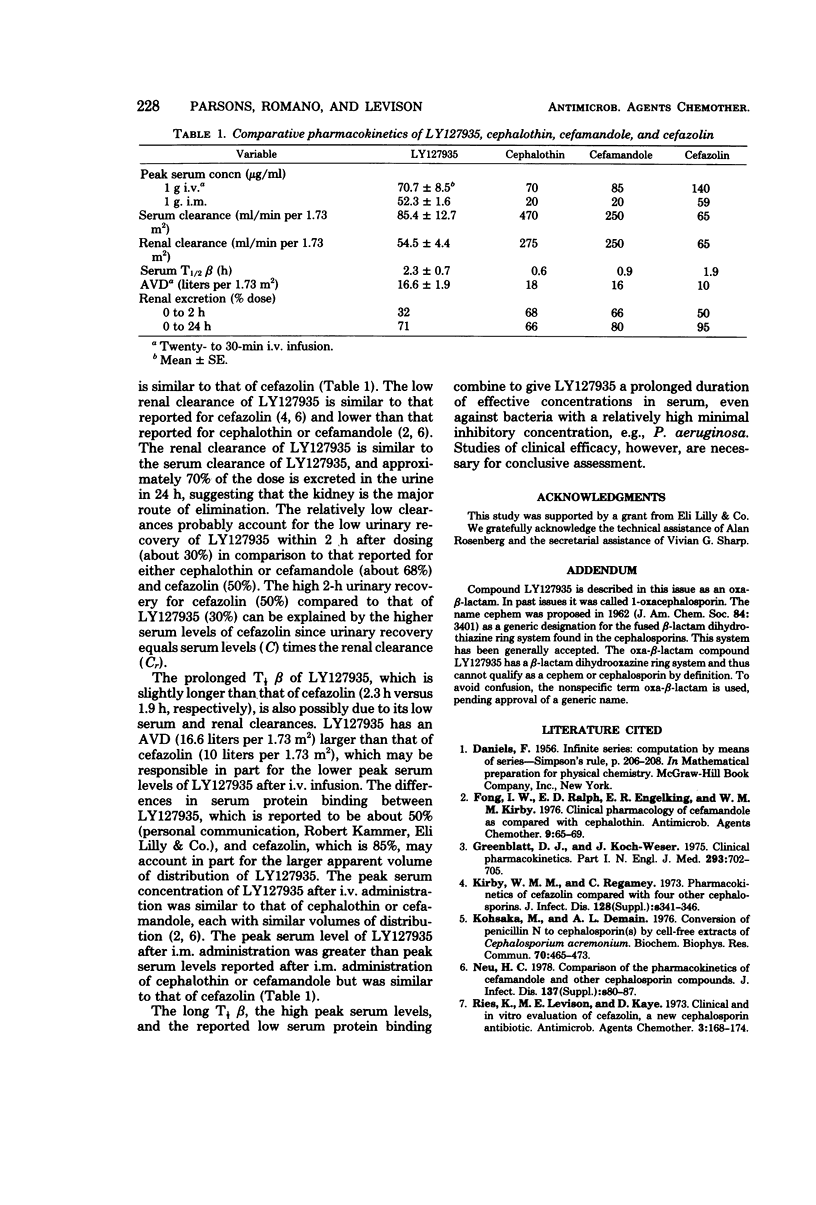

The pharmacokinetics of 1-oxa-β-lactam (LY127935), a new semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotic, was studied in four healthy adult volunteers (mean age of 27 years, mean body surface area ± standard error [SE] of 1.87 ± 0.08 m2, and mean creatinine clearance ± SE of 116 ± 12 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Immediately after completion of a 1-g, 20-min intravenous (i.v.) infusion, the mean serum level ± SE was 70.7 ± 8.5 μg/ml. After a 1-g intramuscular (i.m.) injection, peak serum levels occurred from 30 min to 1 h, and the mean peak serum level ± SE was 52.3 ± 1.6 μg/ml. Beginning at 1 h, the serum concentrations after i.m. administration were higher than those after i.v. administration. At 8 h, the mean serum level ± SE was 3.8 ± 0.6 μg/ml after completion of the i.v. infusion and 4.8 ± 0.7 μg/ml after the i.m. injection. The mean serum half-lives for the β phase i.v. and i.m. administration were similar (2.3 ± 0.7 h and 2.4 ± 0.2 h, respectively). The mean apparent volume of distribution ± SE was 16.6 ± 1.9 liters per 1.73 m2. The mean serum clearance ± SE of LY127935 was 85.4 ± 12.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and the mean renal clearance ± SE was 54.5 ± 4.4 ml/min per 1.73 m.2 Urine concentrations of LY127935 were at least 140 μg/ml in each volunteer during the first 12 h after i.m. or i.v. administration. The mean percentages of the dose recovered in the urine ± SE within 2 h after i.v. or i.m. administration were similar (30 ± 4 and 34 ± 11, respectively). Only 67 ± 3% and 75 ± 13% were recovered in the urine within 24 h after i.v. and i.m. administration, respectively.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Fong I. W., Ralph E. D., Engelking E. R., Kirby W. M. Clinical pharmacology of cefamandole as compared with cephalothin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976 Jan;9(1):65–69. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby W. M., Regamey C. Pharmacokinetics of cefazolin compared with four other cephalosporins. J Infect Dis. 1973 Oct;128(Suppl):S341–S346. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.supplement_2.s341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka M., Demain A. L. Conversion of penicillin N to cephalosporin(s) by cell-free extracts of Cephalosporium acremonium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 May 17;70(2):465–473. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)91069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of cefamandole and other cephalosporin compounds. J Infect Dis. 1978 May;137 (Suppl):S80–S87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.supplement.s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries K., Levison M. E., Kaye D. Clinical and in vitro evaluation of cefazolin, a new cephalosporin antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973 Feb;3(2):168–174. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]