Abstract

Background

In Italy, anthrax is endemic but occurs sporadically. During the summer of 2004, in the Pollino National Park, Basilicata, Southern Italy, an anthrax epidemic consisting of 41 outbreaks occurred; it claimed the lives of 124 animals belonging to different mammal species. This study is a retrospective molecular epidemiological investigation carried out on 53 isolates collected during the epidemic. A 25-loci Multiple Locus VNTR Analysis (MLVA) MLVA was initially performed to define genetic relationships, followed by an investigation of genetic diversity between epidemic strains through Single Nucleotide Repeat (SNR) analysis.

Results

53 Bacillus anthracis strains were isolated. The 25-loci MLVA analysis identified all of them as belonging to a single genotype, while the SNR analysis was able to detect the existence of five subgenotypes (SGTs), allowing a detailed epidemic investigation. SGT-1 was the most frequent (46/53); SGTs 2 (4/53), 3 (1/53) 4 (1/53) and 5 (1/53) were detected in the remaining seven isolates.

Conclusions

The analysis revealed the prevalent spread, during this epidemic, of a single anthrax clone. SGT-1 - widely distributed across the epidemic area and present throughout the period in question - may, thus, be the ancestral form. SGTs 2, 3 and 4 differed from SGT-1 at only one locus, suggesting that they could have evolved directly from the latter during the course of this epidemic. SGT-5 differed from the other SGTs at 2-3 loci. This isolate, thus, appears to be more distantly related to SGT-1 and may not be a direct descendant of the lineage responsible for the majority of cases in this epidemic. These data confirm the importance of molecular typing and subtyping methods for in-depth epidemiological analyses of anthrax epidemics.

Background

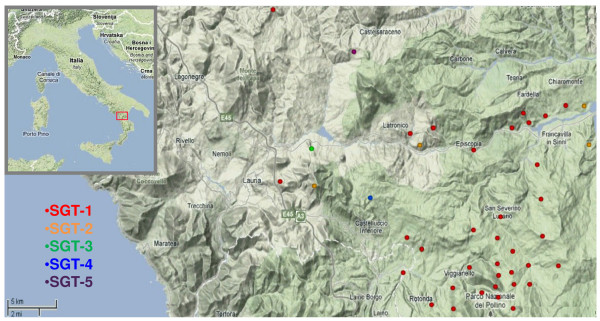

In the region of Basilicata, Southern Italy, anthrax outbreaks are typically isolated, self containing, and involve unvaccinated herbivores. Epidemics are rare, and often occur when a rainy spring is followed by a dry summer [1-5]. During the spring and summer of 2004, as a result of such weather conditions in the Pollino National Park, an anthrax epidemic occurred. The affected area included 13 towns and involved 41 farms over an area of about 900 Km2, with a livestock population numbering about 7,000 cattle and 33,000 between sheep and goats. In 40 days, 81 cattle, 15 sheep, nine goats, eleven horses and eight red deer died (Figure 1). The anthrax epidemic evolved in three different phases. The first, counting 26 outbreaks, was the most critical. The second and third phases, with eight and six outbreaks, respectively, were less severe.

Figure 1.

Map of the Pollino national Park 2004 anthrax epidemic. Geographical representation (GIS data) of the epidemic, with its 41 outbreaks. The five subgenotypes are marked in different color fonts. ©2009 Google - Map data ©2009 Tele Atlas.

An additional outbreak preceded the epidemic by about one month [6]. Several epidemiological factors may have contributed to this phenomenon. In this, as in other endemic areas, spores resulting from previous outbreaks may remain in the soil, thus facilitating the spread of anthrax among livestock through grazing [7,8]. In addition, anthrax infected carcasses are seldom removed. These carcasses are not isolated from the wild animals populating the Pollino National Park (deer, wild boars), resulting in a persistent source of infection in the environment [2]. Furthermore, the abundance, at this time of year, of both biting (e.g. tabanid) and non biting flies, which may act as mechanical vectors, could also have contributed to the persistence of anthrax [9-14].

Genetically, B. anthracis is a relatively homogeneous bacteria species. Not surprisingly, then, discriminating between strains isolated from epidemiologically linked outbreaks is not an easy task [15]. Different studies typed and differentiated B. anthracis isolates using Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP) analysis and Multiple Locus VNTR analysis (MLVA) [16-22]. In an epidemic, however, these methodologies are not likely to find genetic variation. The Single Nucleotide Repeats (SNR) analysis described by Stratilo et al. increases the likelihood of differentiating closely related isolates [23]. Unfortunately, due to the presence of poly-A sequences, such polymorphisms are difficult to detect both with electorphoretic fragment analysis and with direct sequencing.

In this study, a retrospective molecular epidemiological investigation was performed, comparing 25-loci MLVA and two SNR analyses. We applied the modified SNR technique described by Kenefic et al. (KEN-MTD) as well as Stratilo's original SNR method (STR-MTD), selecting the four loci with the highest diversity indices (D = 0.57-0.90; where D = 1-Σ [allele frequency]2) [23,24]. The SNR primer panels used have two loci in common (CL33, CL12) and two distinct loci (STR-MTD: CL1, CL37) (KEN-MTD: CL10, CL35). Two different genetic analyzers (DNA sequencers) were used to verify results. This was done to address the technical difficulty in correct allele assignment.

Results

MLVA 25

The 25-loci MLVA analysis classified all 53 B. anthracis isolates as belonging to a single genotype within cluster A1.a, as defined by Lista et al. (Table 1) [17].

Table 1.

Results of MLVA genotyping and SNR subgenotyping of B. anthracis isolates from the Pollino National Park 2004 epidemic

| MLVA 25 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | No. of Isolates | Allele Coding | |||||||

| A1.a | 53 | VrrA: 10; vrrB1: 16; vrrB2: 7; vrrC1: 57; vrrC2: 21; CG3: 1; bams1: 13; bams 3: 30; bams5: 7; bams13: 30; bams15: 45; bams21: 10; bams22: 16; bams23: 11; bams24: 11; bams25: 13; bams28: 14; bams30: 75; bams31: 64; bams34: 8; bams44: 8; bams51: 9; bams53: 8; pXO1: 7; pXO2: 7. | |||||||

| SNR ANALYSES | |||||||||

| STR-MTD | KEN-MTD | ||||||||

| Subgenotype | No. of Isolates | Loci | Loci | ||||||

| CL33 | CL12 | CL1 | CL37 |

CL33 HM1 |

CL12 HM2 |

CL10 HM6 |

CL35 HM13 |

||

| SGT-1 | 46 | 294 | 172 | 243 | 212 | 83 | 91 | 107 | 117 |

| SGT-2 | 4 | 293 | 172 | 243 | 212 | 82 | 91 | 107 | 117 |

| SGT-3 | 1 | 295 | 172 | 243 | 212 | 84 | 91 | 107 | 117 |

| SGT-4 | 1 | 294 | 173 | 243 | 212 | 83 | 92 | 107 | 117 |

| SGT-5 | 1 | 289 | 173 | 243 | 212 | 78 | 92 | 106 | 117 |

| TOTAL | 53 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Table Top - The 25-loci MLVA cluster group with its allele coding data as defined by Lista et al. [17]. Bottom - SNR alleles are displayed as fragment sizes (base pairs) obtained through capillary electrophoresis. Stratilo's locus nomenclature was used throughout [23]. For results obtained with the KEN-MTD, Kenefic's reference codes are also reported [24]. Alleles differing from those of the most common subgenotype, SGT-1, are underlined and highlighted in bold.

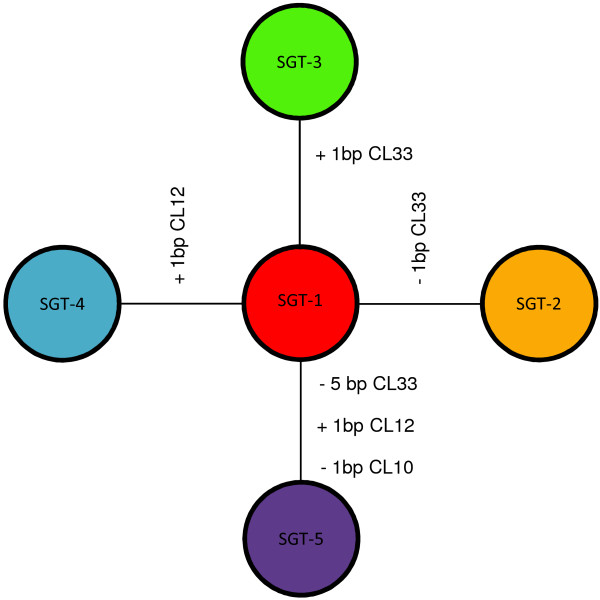

SNR analysis

SNR analysis identified five SGTs. Of 53 isolates, 46 were classified as SGT-1, compared to which four isolates, classified as SGT-2, had a single-base pair deletion corresponding to locus CL33; SGT-3 and SGT-4, each with a single isolate, exhibited insertions in loci CL33 and CL12, respectively, while SGT-5, again with a single isolate, differed from SGT-1 at three loci, with a five-base pair deletion at CL33, an insertion into the CL12 locus, and a deletion at CL10 (Table 1; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic relationships between epidemic strains sample. The mutational steps from the dominant subgenotype to the minor subgenotypes are shown along the branches, indicating the mutated loci and the number of base pairs deleted (-) or inserted (+).

Discussion

Due to homoplasy, the high mutation rate of SNR loci, estimated at 10-4 per generation in B. anthracis, does not allow a correct definition of phylogenetic relationships between different isolates [15]. SNR is, however, able to detect genetic diversity between closely related strains as would occur in an epidemic [6]. Our method of analysis involved the initial use of 25-loci MLVA to define genetic relationships, and a subsequent investigation of genetic diversity between epidemic strains through SNR analysis.

The 25-loci MLVA assigned all strains to a single genotype within the cluster A1.a, evidence of their autochthonous origin. This particular genotype is frequently found in Basilicata. The two SNR analyses, STR-MTD and KEN-MTD, yielded the same result, identifying five SGTs. The difference between these methods in terms of the amplicon sizes obtained for the common loci is a consequence of the use of different primer pairs. We found the KEN-MTD more useful, as it allows for a multiplexed reaction and permits faster and more reliable detection of fragment sizes, owing to smaller amplicons sizes. Moreover, the KEN-MTD revealed an additional difference between SGT-5 and SGT-1, an allele in the CL10 (Table 1). Polymorphisms were only discovered among the loci with the highest diversity indices (CL33, CL12, CL10) [23].

SGT-1, the most common, was distributed across the epidemic area and present throughout the period under study. SGT-1 was also detected in soil from a grave site, and in the feces of wild boar collected in the same area, suggesting it is the probable ancestral strain. SGTs 2-4 were rarer (6/53) and not present in all phases of the epidemic. These SGTs could represent intra epidemic mutational steps descended from SGT-1. SGT-5, with three loci exhibiting fragment length polymorphism as compared to SGT-1, was the first to be isolated in the affected area, but may have descended from a different, closely related previous outbreak (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characterization of the 41 Bacillus anthracis outbreaks of the Pollino National Park 2004 epidemic sample

| DATE OF OUTBREAK | STRAIN AND SUBGENOTYPE | FARM CODE | LONGITUDE | LATITUDE | ALTITUDE | ANIMAL DEATHS BY SPECIES | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOVINE | OVINE | HORSE | RED DEER | GOAT | |||||||

| 28/07/2004- | 069-SGT-5 | 025PZ072 | 40.17564 | 15.96357 | 1025 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 25/08/2004 | 070/072-SGT-1 | 097PZ111 | 39.95204 | 16.13405 | 1000 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 30/08/2004- I phase | 071-SGT-1 | 034PZ162 | 40.06903 | 16.17553 | 474 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||

| 30/08/2004- I phase | 073-SGT-2 097-SGT-1 |

097PZ065 | 40.00476 | 16.13205 | 800 | 9 | 9 | ||||

| 01/09/2004- I phase | 075-SGT-1 | 097PZ190 | 39.95204 | 16.13405 | 1000 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 02/09/2004- I phase | 074-SGT-1 | 078PZ043 | 40.04136 | 16.18231 | 773 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 03/09/2004- I phase | 078-SGT-1 | 097PZ009 | 39.95566 | 16.11553 | 800 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 05/09/2004- I phase | 077-SGT-1 | 023PZ008 | 40.03877 | 15.98671 | 950 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| 06/09/2004- I phase | 093-SGT-1 081-SGT-1 |

028PZ007 | 40.07953 | 16.16534 | 458 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 06/09/2004- I phase | 076-SGT-1 | 070PZ068 | 39.975 | 16.02374 | 330 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| 07/09/2004- I phase | 087-SGT-1 | 078PZ004 | 40.04 | 16.181 | 773 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| 07/09/2004- I phase | 083-SGT-1 | 078PZ012 | 40.041 | 16.182 | 773 | 7 | 1 | 8 | |||

| 07/09/2004- I phase | 084-SGT-1 | unknown | 40.003 | 16.131 | 800 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 08/09/2004- I phase | 092-SGT-1 | 097PZ107 | 39.96333 | 16.07981 | 620 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | No isolates | 022PZ014 | 40.02203 | 16.00367 | 720 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | No isolates | 022PZ024 | 40.02101 | 16.00301 | 720 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | No isolates | 022PZ041 | 40.01079 | 16.02706 | 700 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | 099-SGT-1 | 022PZ043 | 40.00578 | 16.02734 | 700 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | No isolates | 022PZ106 | 40.03498 | 15.99999 | 900 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 09/09/2004- I phase | 091-SGT-2 | 028PZ171 | 40.08685 | 16.23801 | 450 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 10/09/2004- I phase | 098-SGT-1 | 097PZ105 | 39.97987 | 16.16671 | 950 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 10/09/2004- I phase | 096-SGT-1 | 097PZ152 | 39.99478 | 16.04499 | 630 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 10/09/2004- I phase | 089-SGT-1 | unknown | 40.06463 | 16.14047 | 600 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 11/09/2004- I phase | 082/095/086-SGT-1 | 097PZ016 | 39.95466 | 16.11453 | 800 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 12/09/2004- I phase | 088/094-SGT-1 | 030PZ027 | 40.08343 | 16.07682 | 636 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 13/09/2004- I phase | 090-SGT-4 | 022PZ015 | 40.01337 | 15.99796 | 648 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 14/09/2004- I phase | 085-SGT-1 | 040PZ014 | 40.07418 | 15.99999 | 600 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||

| 15/09/2004- I phase | 079-SGT-1 | 042PZ119 | unknown | unknown | 1300 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 19/09/2004-II phase | 116-SGT-1 | 040PZ017 | 40.07418 | 15.99999 | 600 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 19/09/2004- II phase | 080-SGT-1 | unknown | 40.0242 | 16.30969 | 619 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 19/09/2004- II phase | 117-SGT-1 | 078PZ096 | 40.042 | 16.18589 | 790 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 20/09/2004- II phase | 113-SGT-1 | 022PZ010 | 40.0206 | 16.0796 | 723 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 21/09/2004- II phase | 106/107-SGT-1 | 031PZ028 | 40.11861 | 16.171 | 620 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 22/09/2004- II phase | 108-SGT-1 | 042PZ430 | 40.07374 | 16.00476 | 600 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 22/09/2004- II phase | No isolates | unknown | 40.06388 | 16.00388 | 942 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 24/09/2004- II phase | 112-SGT-3 | 030PZ003 | unknown | unknown | 608 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 27/09/2004-III phase | 118-SGT-1 | 050PZ064 | 40.18915 | 15.90076 | 988 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 27/09/2004- III phase | 100/101-SGT-1 | unknown | 40.04144 | 16.08247 | 910 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 28/09/2004- III phase | 102/103-SGT-1 | unknown | 40.03934 | 16.0807 | 924 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 28/09/2004- III phase | 114/115-SGT-2 | 031PZ027 | 40.11801 | 16.174 | 680 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 29/09/2004- III phase | 111-SGT-1 | 042PZ080 | 40.05419 | 15.86776 | 936 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 03/10/2004- III phase | 119-SGT-1 | unknown | unknown | unknown | n.a. | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 22/09/04 | 104/105-SGT-1 | Isolated from soil | unknown | unknown | n.a. | ||||||

| 21/10/04 | 120/121-SGT-1 | Isolated from feces (wild boar) | unknown | unknown | n.a. | ||||||

| TOTAL | 81 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 124 | |||||

The 53 B. anthracis strains are numbered (from 069 to 121) following the Anthrax Reference Institute of Italy coding system. For each outbreak, the date and phase of the epidemic is reported, as well as the number of animal deaths and their species. The subgenotype and GIS coordinates of the site of sample collection are indicated for each isolated strain.

Conclusions

The epidemic under study was characterized by a single anthrax clone. Although the epidemic spread over a large area, it involved extremely closely related isolates, 86.7% of which (SGT-1) were identical across the highly discriminating SNR markers. This epidemic was probably exacerbated by the absence of a careful monitoring of animals, making it possible for spores from a recent victim to spread in the environment. The mutational steps found in SGT-2, 3 and 4 may be associated with infective cycles subsequent to the first, while the presence of a more distantly related strain, SGT-5, testifies to the evolutionary history of this lineage in this region. This divergent mutational clone may have originated from different outbreaks in the past. The high throughput genotyping system used in this study proved to be a useful tool for the study of closely related B. anthracis strains, and is therefore potentially valuable not only for the study of epidemics, but also for other contexts requiring the characterization of closely related strains such as the study of biological contaminations through environmental isolates or the forensic investigation of bioterrorist events.

Methods

Bacillus anthracis isolates

In this study, we analyzed 53 B. anthracis strains associated with a single anthrax epidemic.

DNA preparation

Each B. anthracis strain was streaked onto 5% sheep blood agar plates and then incubated at + 37°C for 24 hours. After heat inactivation (98°C for 20 min.), microbial DNA was extracted using DNAeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen), following the protocol for Gram positive bacteria.

25-loci MLVA and SNR analyses

We utilized 5' fluorescent-labelled oligos, deprotected and desalted, specifically selected for the VNTRs and for the SNRs used.

The 25 specific primer pairs for the MLVA were selected as described by Lista et al. [17]. The eight specific primer pairs for SNR reactions were selected following Stratilo et al. and Kenefic et al. [23,24] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Primers used in this study for MLVA and SNR analyses

| LOCUS | PRIMER SEQUENCE (5' to 3') | CONCENTRATION μM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLVA 25 | |||

| CG3 | F:CY5.5-TGTCGTTTTACTTCTCTCTCCAATAC R:AGTCATTGTTCTGTATAAAGGGCAT |

0.30 | |

| bams44 | F: CY5.5-GCACTTGAATATTTGGCGGTAT R: GCGAATTAATTGCTCCTCAAAT |

0.30 | |

| bams3 | F: CY5.5-GCAGCAACAGAAAACTTCTCTCCAATAACA R:TCCTCCCTGAGAACTGCTATCACCTTTAAC |

0.30 | |

| Multiplex A | vrrB2 | F: D2-CACAGGCTATTCTTTATCAAACTCATC R: CCCAAGGTGAAGATTGTTGTTGA |

0.15 |

| bams5 | F: D2-GCAGGAAGAACAAAAGAAACTAGAAGAGCA R: ATTATTAGCAGGGGCCTCTCCTGCATTACC |

0.30 | |

| bams15 | F: D2-GTATTTCCCCCAGATACAGTAATCC R: GTGTACATGTTGATTCATGCTGTTT |

0.60 | |

| bams1 | F: CY5-GTTGAGCATGAGAGGTACCTTGTCCTTTTT R: AGTTCAAGCGCCAGAAGGTTATGAGTTATC |

0.15 | |

| vrrC1 | F: CY5-GAAGCAAGAAAGTGATGTAGTGGAC R: CATTTCCTCAAGTGCTACAGGTTC |

0.30 | |

| bams13 | F: CY5.5-AATTGAGAAATTGCTGTACCAAACT R: CTAGTGCATTTGACCCTAATCTTGT |

0.30 | |

| vrrB1 | F: CY5--ATAGGTGGTTTTCCGCAAGTT R: GATGAGTTTGATAAAGAATAGCCTGTG |

0.10 | |

| Multiplex B | bams28 | F: CY5-CTCTGTTGTAACAAAATTTCCGTCT R: TATTAAACCAGGCGTTACTTACAGC |

0.15 |

| vrrC2 | F: CY5-CCAGAAGAAGTGGAACCTGTAGCAC R: GTCTTTCCATTAATCGCGCTCTATC |

0.10 | |

| bams53 | F: D2-GAGGTGTGTTAGGTGGGCTTAC R: CATATTTTCACCTTAATTTTGGAAG |

0.60 | |

| bams31 | F: D2-GCTGTATTTATCGAGCTTCAAAATCT R: GGAGTACTGTTTGTTGAATGTTGTTT |

0.60 | |

| vrrA | F: CY5.5-CACAACTACCACCGATGGCACA R: GCGCGTTTCGTTTGATTCATAC |

0.06 | |

| bams25 | F: CY5.5-CCGAATACGTAAGAAATAAATCCAC R: TGAAAGATCTTGAAAAACAAGCATT |

0.15 | |

| Multiplex C | bams21 | F: CY5.5-TGTAGTGCCAGATTTGTCTTCTGTA R: CAAATTTTGAGATGGGAGTTTTACT |

0.30 |

| bams34 | F: D2-TGTGCTAAATCATCTTGCTTGG R: CAGCAAAATCAATCGAATCAAA |

0.30 | |

| bams24 | F: CY5-CTTCTACTTCCGTACTTGAAATTGG R: CGTCACGTACCATTTAATGTTGTTA |

0.30 | |

| bams51 | F: CY5-ATTTCCTGAAGCAGGTTGTGTT R: TGCATCTAACAATGCAGAACAA |

0.60 | |

| bams22 | F: CY5-ATCAAAAATTCTTGGCAGACTGA R: ACCGTTAATTCACGTTTAGCAGA |

0.15 | |

| Multiplex D | bams23 | F: D2-CGGTCTGTCTCTATTATTCAGTGGT R: CCTGTTGCTCCTAGTGATTTCTTAC |

0.30 |

| bams30 | F: CY5.5-AGCTAATCACCTACAACACCTGGTA R: CAGAAAATATTGGACCTACCTTCC |

0.30 | |

| pXO1 | F: CY5-CAATTTATTAACGATCAGATTAAGTTCA R: TCTAGAATTAGTTGCTTCATAATGGC |

0.15 | |

| pXO2 | F: CY5.5-TCATCCTCTTTTAAGTCTTGGGT R: GTGTGATGAACTCCGACGACA |

0.15 | |

| STR-MTD | |||

| Singleplex A | CL33 | F: 6FAM-TGGGGTATATTCCCATCGAA R:CCGCAGATACCAACCAACAT |

0.2 |

| Singleplex B | CL12 | F: 6FAM-AAGCCAGGTGCAAAAACAGT R: TCTCACTGTGCCTCGCTAAA |

0.2 |

| Singleplex C | CL1 | F: 6FAM-TTCTCGGAGATGATTTTCGG R:CTCCCATTTTACATCCCCCT |

0.2 |

| Singleplex D | CL37 | F: NED-CTCCGCAATTTTCAAACGAT R: CCGCCGGCATAAAGATAGTA |

0.2 |

| KEN-MTD | |||

|

CL33 HM1 |

F: PET GAAAACTTTGCAACCGACC R: GTCGAACGTGTTCTAGCTACAG |

0.2 | |

| Multiplex I |

CL10 HM6 |

F: 6FAM-TAAAAAGACAGAATTTTCAATTTTATCAACAAC R: GTGGAAACTAATGTGAGTTATATATGTTAGTTAAG |

0.2 |

|

CL12 HM2 |

F: VIC-GCTATTCTCACTGTGCCTCG R: GTTAAAACGAAGTAAAGAAAAGTGGG |

0.2 | |

|

CL35 HM13 |

F: NED-GGATTGCTTAAGGTATATAATGGATTT R: GTTGTGTTCCATATGTATCCCTCC |

0.1 | |

MLVA PCRs were performed in four multiplex reactions in a final volume of 15 μl. The reaction mixture contained: 1× PCR reaction buffer (Roche), 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche), dNTPs (0.2 mM each), and appropriate concentrations of each primer as reported in Table 3. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 96°C for 3 min; 36 cycles at 95°C for 20 s, at 60°C for 30 s, and at 72°C for 1 min; and finally, 72°C for 10 min.

The KEN-MTD PCR was performed in a multiplex reaction in a final volume of 25 μl containing 1× AmpliTaq Gold PCR buffer and 0.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems Inc.), 3,5 mM MgCl2, dNTPs (0.2 mM each), and appropriate concentrations of forward and reverse primers as reported in Table 3.

STR-MTD PCRs were performed in four singleplex reactions in a final volume of 25 μl containing 1× AmpliTaq Gold PCR buffer and 0.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems Inc.), 4 mM MgCl2, dNTPs (0.2 mM each), and appropriate concentrations of forward and reverse primers as reported in Table 3. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and finally, 72°C for 7 min.

Automated genotype analysis

MLVA PCR products were diluted 1:5. Five μl of solution were added to a mix containing 40 μl of Sample Loading Solution (Beckman Coulter) and 0.5 μl of MapMarker 1000 size marker (BioVentures Inc.). Amplicons were separated by electrophoresis on a CEQ 8000 automated DNA Analysis System (Beckman Coulter) and sized by CEQ Fragment Analysis System software.

Amplified SNR PCR products were diluted 1:80 and subjected to capillary electrophoresis on ABI Prism 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) with 0.25 μl of GeneScan 120 Liz and 500 Liz size standards for KEN-MTD and STR-MTD amplicons, respectively, and sized by GeneMapper 4.0 (Applied Biosystems Inc.). DNA extracted from each sample was tested by two different laboratories: the Anthrax Reference Institute of Italy, and the Army Medical and Veterinary Research Institute.

Authors' contributions

GG conceived the study, participated in its design, coordinated the molecular tests and drafted the manuscript. AC participated in performing the 25-loci MLVA and the SNR analyses and helped to draft the manuscript. AF designed the study and coordinated the collection of samples. SS performed the SNR analysis and helped draft the manuscript. VP participated in performing the 25-loci MLVA. RA helped design the study. FL coordinated the work of the two laboratories and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Giuliano Garofolo, Email: ggarofolo@libero.it.

Andrea Ciammaruconi, Email: andrea.ciammaruconi@gmail.com.

Antonio Fasanella, Email: a.fasanella@izsfg.it.

Silvia Scasciamacchia, Email: silviascasciamacchia@tiscali.it.

Rosanna Adone, Email: rosanna.adone@iss.it.

Valentina Pittiglio, Email: valentina.pittiglio@gmail.com.

Florigio Lista, Email: florigio.lista@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by the Italian Ministry of Health (DIAGNOVA funds, Ricerca Corrente 2006). We thank Angela Aceti, Giuseppe Stramaglia, Nicola Nigro and Rosa d'Errico for their excellent technical support.

References

- Fasanella A, Van Ert M, Altamura SA, Garofolo G, Buonavoglia C, Leori G, Huynh L, Zanecki S, Keim P. Molecular diversity of Bacillus anthracis in Italy. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3398–3401. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3398-3401.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones ME, de Vos V. Anthrax and wildlife. Rev Sci Tech. 2002;2:359–389. doi: 10.20506/rst.21.2.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones ME. 1996-97 Global Anthrax report. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:189–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AJ, Galvin JW, Rubira RJ, Condron RJ, Brandley T. Experiences with vaccination and epidemiological investigations on an anthrax outbreak in Australia in 1997. J of Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:294–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PC, Bell RH, Saigawa K, Munyenyembe FE, Mulenga CK. Anthrax in wildlife in Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Vet Rec. 1991;128:399–403. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.17.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasanella A, Palazzo L, Petrella A, Quaranta V, Romanelli B, Garofolo G. Anthrax in red deer (Cervus elaphus), Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(7):1118–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon DC, Rennie RP. ecology of anthrax spores: tough but not invincible. Can Vet J. 1999;36(5):The295–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon DC, Bader DE, Mitchell J, Woollen N. Natural dissemination of Bacillus anthracis spores in Northern Canada. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(3):1610–1615. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1610-1615.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzmain MB. Experimental insect transmission of anthrax. Public Health Reports. 1914;29:75–7716. [Google Scholar]

- Kraneveld FC, Djaenoedin R. Test on the dissemination of anthrax by Tabanus rubidus in horses and buffalo. Overgedrukt uit de Nederlands-Indische Bladen Voor Diergeneeskunde. 1940;52:339–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rao NS, Mohiyudeen S. Tabanus flies as transmitters of anthrax - a field experience. Indian Veterinary Journal. 1958;35:348–353. [Google Scholar]

- Davies JC. A major epidemic of anthrax in Zimbabwe. Part II. Cent Afr J Med. 1983;29(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrel MJ, Knudson GB. Mechanical transmission of Bacillus anthracis by stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) and mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti and Aedes taeniorhynchus) Infection and immunity. 1987;55:1859–1961. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1859-1861.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones M, Blackburn J. The ecology of Bacillus anthracis. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2009;30(6):356–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, van Ert MN, Pearson T, Vogler AJ, Huynh LY, Wagner DM. Anthrax molecular epidemiology and forensics: using the appropriate marker for different evolutionary scales. Infect Genet Evol. 2004;4:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Price LB, Klevytska AM, Smith KL, Schupp JM, Okinaka R, Jackson P, Hugh Jones ME. Multiple-Locus Variable-Number Tandem Repeat Analysis Reveals Genetic Relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriology. 2000;182:2928–2936. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2928-2936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lista F, Faggioni G, Valjevac S, Ciammaruconi A, Vaissaire J, le Doujet C, Gorge O, de Santis R, Carattoli A, Ciervo A, Fasanella A, Orsini F, D'Amelio R, Pourcel C, Cassone A, Vergnaud G. Genotyping of Bacillus anthracis strains based on automated capillary. BMC Microbiology. 2006;6:6–33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouet A, Smith KL, Keys C, Vaissaire J, Le Doujet C, Lévy M, Mock M, Keim P. Diversity Among French Bacillus anthracis Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4732–4734. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4732-4734.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierczynski R, Jakubczak A, Jagielski M. Extended multiple-locus variable tandem-repeat analysis of Bacillus anthracis isolated in Poland. Pol J Microbiol. 2009;58(1):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ert M, Easterday WR, Huynh LY, Okinaka RT, Hugh-Jones ME, Ravel J, Zanecki SR, Pearson T, Simonson TS, U'Ren JM, Kachur SM, Leadem-Dougherty RR, Rhoton SD, Zinser G, Farlow J, Coker PR, Smith KL, Wang B, Kenefic LJ, Fraser-Liggett CM, Wagner DM, Keim P. Global Genetic Population Structure of Bacillus anthracis. PlosOne. 2007;5:461–471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Busch JD, Ravel J, Read TD, Rhoton SD, U'Ren JM, Simonson TS, Kachur SM, Leadem RR, Cardon ML, Van Ert MN, Huynh LY, Fraser CM, Keim P. Phylogenetic discovery bias in Bacillus anthracis using single-nucleotide polymorphisms from whole-genome sequencing. Procl Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(37):13536–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403844101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Salzberg SL, Pop M, Shumway M, Umayam L, Jiang L, Holtzapple E, Busch JD, Smith KL, Schupp JM, Solomon D, Keim P, Fraser CM. Comparative genome sequencing for discovery of novel polymorphisms in. Bacillus anthracis. 2002;296(5575):2028–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1071837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratilo CW, Lewis CT, Bryden L, Mulvey MR, Bader D. Single-nucleotide repeat analysis for subtyping Bacillus anthracis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(3):777–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.777-782.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenefic LJ, Beaudry J, Trim C, Huynh L, Zanecki S, Matthews M, Schupp J, Van Ert M, Keim P. A high resolution four-locus multiplex single nucleotide repeat (SNR) genotyping system in Bacillus anthracis. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;73(3):269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]