Abstract

Background

Underserved populations are underrepresented in public health initiatives such as tobacco control and in cancer clinical trials. Community involvement is crucial to interventions aimed at reducing health disparities, and local health departments increasingly are called upon to provide both leadership and funding. The Tacoma Pierce County Health Department (TPCHD), in conjunction with 13 key community-based organizations and healthcare systems, formed the Cross Cultural Collaborative of Pierce County (CCC) that successfully employs needs-assessment and evaluation techniques to identify community health initiatives.

Methods

Community leaders from six underserved populations of the CCC were trained in needs-assessments techniques. Assessments measured effectiveness of the collaborative process and community health initiatives by using key informant (n = 18) and group interviews (n = 3).

Results

The CCC, facilitated by its partnership with the TPCHD, built capacity and competence across community groups to successfully obtain two funded public health initiatives for six priority populations. Members expressed overall satisfaction with the training, organizational structure, and leadership. The CCC’s diversity, cultural competency, and sharing of resources were viewed both as a strength and a decision-making challenge.

Conclusion

Public health department leadership, collaboration, and evidence-based assessment and evaluation were key to demonstrating effectiveness of the interventions, ensuring the CCC’s sustainability.

Keywords: capacity building, collaborative, community assessments, evaluation

Community involvement is crucial to improve societal health and address health disparities. In the complex American health system, collaborations among community health organizations can result in better health outcomes1,2 by enhancing the capacity of people and organizations to create effective programs.1–4

Local health departments are increasingly called upon by the federal government to spearhead collaboration and provide funding for public health community collaboratives.5–8

Cross Cultural Collaborative of Pierce County

In 1998, the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department (TPCHD) of Washington State invited 13 key community-based partner organizations (CPOs) and healthcare systems to meet and discuss issues related to tobacco health disparities. These CPOs, identified from previous projects, represented six priority populations affected by health disparities—tobacco disparities in particular—based on national and state surveillance data (local data were not available): African Americans, Asians/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics/Latinos, lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender groups, low-income residents, and Native Americans. For about a year, and without funding, these 13 CPOs and TPCHD met to discuss how to eliminate tobacco disparities, while also discussing other health disparity issues important to the communities. In 1999, the group began planning a tobacco disparities conference; this period of conference planning marked the official formation of the Cross Cultural Collaborative of Pierce County (CCC). The CCC has since doubled, to include 26 CPOs.

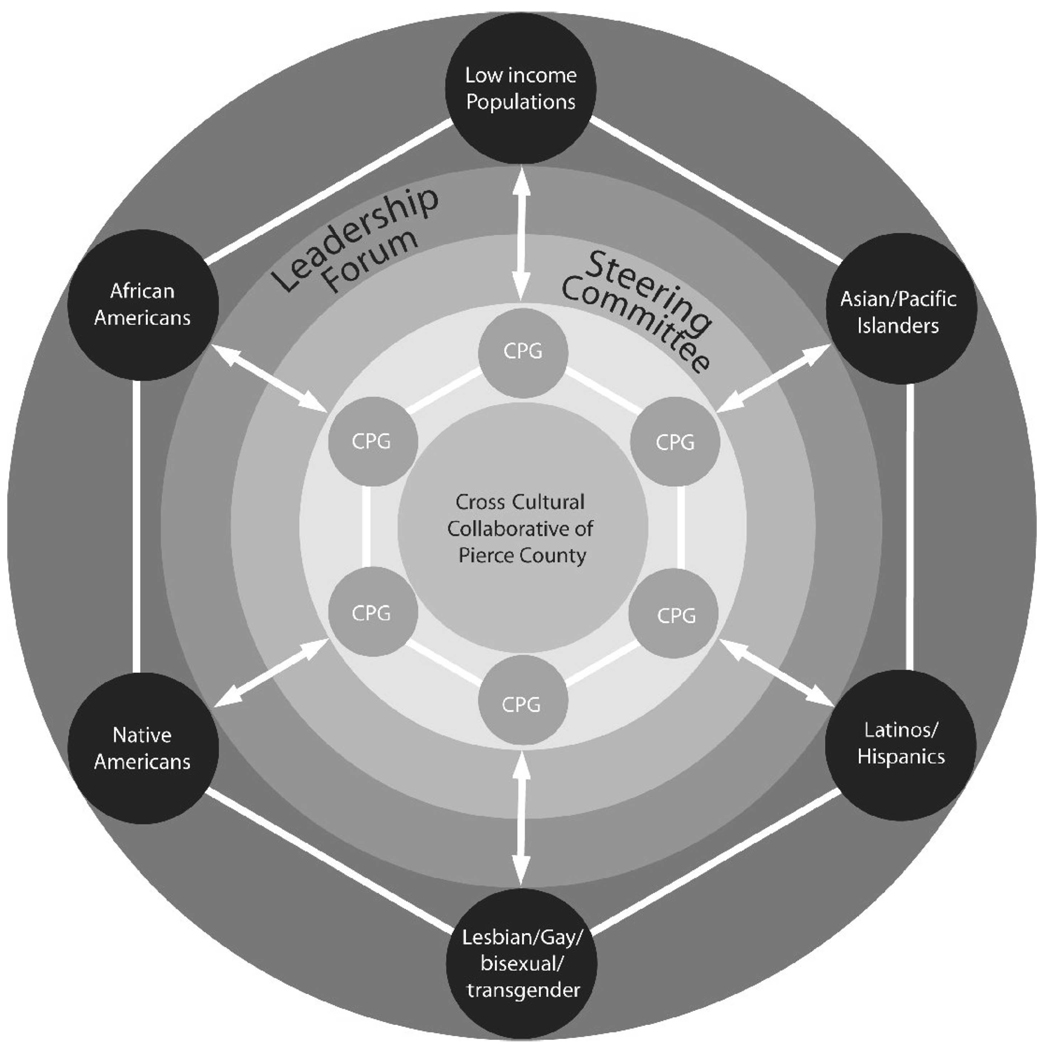

The CCC’s structure and governance includes three dimensions (Figure 1):

Six community planning groups (CPGs), one for each of the priority populations. The groups are responsible for determining the scope of work and allocation of resources in a noncompetitive environment. A TPCHD staff community liaison is assigned to each CPG.

The Cross Cultural Steering Committee brings together members of all six CPGs. The committee shares information and resources for both CCC projects and individual CPO activities and discusses ways to advocate for key health concerns.

The Leadership Forum is comprised of executive staff from each CPO. This group discusses and recommends future directions and funding possibilities, advocates for the CCC, and strategizes about needed services.

FIGURE 1.

The Cross Cultural Collaborative of Pierce County

This article describes an innovative approach to capacity building founded on ongoing needs assessment and self-evaluation, which harnessed the expertise of a local health department and its communities working collaboratively to address community health disparities. The focus on assessment capacity building has successfully led to two funded public health initiatives for this collaborative team.

Methods

The CCC’s first success was the 2002 award of a 1-year $100 000 grant from the American Legacy Foundation to conduct assessment activities and collect local disparities data related to tobacco use. In 2002, TPCHD staff and a consultant from one of the priority populations began training CCC members to collect, analyze, and use quantitative and qualitative assessment data of tobacco disparities. At the same time, TPCHD conducted assessments to measure changes in capacity as part of a process evaluation of the CCC. The tobacco disparities assessment activities continued from 2002 to 2004. The CCC self-evaluation assessment activities continued from 2002 to 2007. Both types of assessments helped build capacity and competency within the CCC to successfully move beyond tobacco and begin addressing other health disparities in their six priority populations.

Assessment activities to build collaborative capacity

The TPCHD strengthened community capacity through skills training seminars and workshops that equipped the CCC to conduct tobacco assessment activities within their respective communities. The trainings created opportunities to increase cultural competency of the trainers and partners and, in turn, produced tobacco control programs and services that were respectful, relevant, and responsive to the cultural needs of the communities.

More than 30 hours of assessment training and consultation were provided to collaborative partners between June 2002 and January 2004. Assessment and training activities included interviewing techniques, conducting group interviews and key informant interviews, transcribing and analyzing data, and writing and disseminating findings.

Measurement of collaborative capacity

The TPCHD staff and a community-based consultant conducted individual interviews with key informants and group interviews of each of the CPOs to measure changes in the CCC’s capacity to work effectively as a collaborative partnership. To ensure representation of diverse voices, a snowball technique was used. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to recommend others to participate, particularly those with opinions disparate from those of the participants.

Key informant interviews

The key informant interviews conducted in 2003 and 2007 were designed to identify strengths and weaknesses of the collaborative. The questions focused on the three dimensions of the CCC structure: the Steering Committee, the Leadership Forum, and the Community Planning Groups. The topics included, but were not limited to (1) what worked well, and what did not work, (2) suggested changes to the Collaborative, and (3) the decision-making process. Participants were informed that the interview was voluntary and the information gathered would be anonymous.

Group interviews

Group interviews were conducted during Steering Committee meetings and leadership retreats in 2004 and 2006. At least one representative from each of the six priority populations was present at each meeting. At the group interviews, the CCC’s previous year’s work was reviewed to identify strengths and weaknesses; to exchange information about current needs, perspectives, and health priorities within the populations; and to suggest future directions.

Data analysis plan

Key informant interviews were analyzed for main and common themes using Nudist software (QSR International (Americas) Inc, Cambridge, MA) by TPCHD staff and consultant.9 The community-based consultant coded and analyzed the group interview transcripts for key themes using content analysis methods.10

Results

Measurement of Collaborative capacity

Eighteen structured key informant interviews were conducted in 2003 and 12 in 2007. Seven individuals participated at both time points. The interviews lasted from 30 to 45 minutes. Results from the 2003 interviews revealed that the partners valued skill building and training opportunities, as well as the opportunity to collaborate and network with other members of the CCC. Partners also stated that they gained knowledge and awareness of different cultures and groups represented at the meetings. More importantly, they appreciated and valued the grass roots nature of the collaborative and the commitment to improve the health of underserved communities. However, members expressed the need for a clearly defined purpose of the CCC.

The 2007 results showed that the CCC had responded by developing a mission statement: “To collaboratively promote community health and systematic change in formal and informal health care systems to be accessible, available, and culturally appropriate for all.”11(p1) In addition, members continued to value the training opportunities and honor the collaboration among the six priority populations. Moreover, they expressed overall satisfaction with the organizational structure and leadership of the CCC and indicated that they would like to deepen the relationship with the health department.

Three group interviews were conducted: one in 2004 and two in 2006. The numbers of participants in the groups were 10, 16, and 38. The group interviews lasted from 30 minutes to 2.5 hours. Several recurrent themes for both time points were noted. Participants indicated satisfaction with the plan for expansion of the mission and goals of the CCC beyond tobacco control. A continued focus on diversity, cultural competency, and sharing of resources among communities was highlighted. The differences among the six communities were viewed as a strength of the CCC, although acknowledged as a challenge to decision making. The most difficult challenges to sustaining the CCC were effective communication, consistent participation, and financial and administrative support.

Funded initiatives

The assessment activities conducted by both CCC members in their own communities and TPCHD staff and consultants to evaluate the CCC have led to increased capacity among the CCC to conduct assessment activities and have made the CCC a more competitive grant applicant. To date, the CCC has successfully competed for two multiyear funded initiatives. In 2004, the CCC received a second grant from The American Legacy Foundation, for $400 000, which enabled it to identify community-specific approaches to tobacco control and to increase the quantity and quality of culturally appropriate and language-specific tobacco cessation services in all six priority populations.

In 2006, the CCC was awarded a $450 000 grant from the Education Network to Advance Cancer Clinical Trials, funded by the Lance Armstrong Foundation. Its purpose is to empower the CCC to further engage the community and raise awareness within the six priority populations about the importance of cancer treatment and care. In preparation the grant, CCC demonstrated an ability to conduct the qualitative assessments of community partners and healthcare providers regarding knowledge of and barriers to participation in cancer clinical trials.

Discussion

To effectively address the many issues affecting a community’s health, including social, cultural, and environmental factors, public health professionals must be able to mobilize community organizations. The success of the CCC in organizing underserved groups to work collaboratively on the issues of tobacco control and to raise the awareness of how underserved populations may become involved in cancer clinical trials was facilitated by its partnership with the TPCHD. The TPCHD encouraged collaboration rather than competition among local CPOs to maximize efficiency and effectiveness of community organizations with demonstrable ability to influence how the health department conducts business with the community.

Assessment activities played a critical role in building capacity of the CCC, evaluating its effectiveness, and ensuring its sustainability by obtaining additional funding. The TPCHD helped educate CCC partners about the value of assessment skills and techniques, and CCC partners helped educate TPCHD staff to develop culturally appropriate assessment tools. The CCC has leveraged a now-proven track record into further sustainable initiatives, fulfilling its mission to “collaboratively promote community health and systematic change in formal and informal health care systems.”11(p1)

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the NIH Roadmap Clinical and Translational Science Award grant (CTSA: KL2 RR024154-03); and the Research Center of Excellence in Minority Health Disparities at UPITT/NIH-NCMHD GRANT (5P60MD000207-07) from the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

We thank Anne George, Peter Straub, and Tatiana Maxenkova, and members of the CCC whose help made this manuscript a reality.

Biographies

Mary A. Garza, PhD, MPH, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, and Deputy Director, Center for Minority Health, both at the Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh. She received her PhD from Johns Hopkins University, School of Public Health, where she also completed a postdoctoral fellowship in Cancer Epidemiology. She is trained in the social and behavioral sciences with a strong interest in cancer health disparities research.

Diane J. Abatemarco, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Public Health and Codirector of the Institute for Evaluation Science and Community Health, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh. Her primary areas of expertise include evaluation research methods, survey research methods, and behavioral epidemiology. Dr Abatemarco’s research focus is on child maltreatment prevention, community health through empowerment, and international public health infrastructure partnerships.

Cindan Gizzi, MPH, is Community Assessment Manager at the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, Tacoma, Washington. She received an MPH in epidemiology from UCLA. She is responsible for the health department’s epidemiology, vital records, and planning functions and also for guiding and implementing the evaluation of multiple programs. She also worked as an epidemiologist at the Sonoma County Department of Health Services in California, Southern California Injury Research Center, and she was a health-promotion coordinator for a northern California HMO.

Lynn M. Abegglen, MSW, is Educator and Consultant, PeaceWorks, Washington. She earned an MSW and Bachelor of Arts degrees at San Diego State University. Her previous research projects includes Coprincipal Investigator for “Childhood Incest Experiences and Abuse in Adult Intimate Relationships,” selected for the Eighth Annual Presentation of Outstanding Master’s Essays; School of Social Work, San Diego State University, 1984. Current work includes promoting and training about culturally competent service-provision, diversity, and health equity issues.

Christina Johnson-Conley, PhD, is a PhD candidate at the University of Washington’s School of Nursing. Her research interest involves using community-based participatory action research methods to reduce cultural health disparities. Christina’s experience includes consultation, support, and training to staff, volunteers, students, agencies, and organizations regarding data collection, analysis and interpretation, as well as program evaluation. She is a consultant with the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department in the Cross-Cultural Collaborative and the Environmental Health Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):179–205. III–IV. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker E, Margolis LH, Eng E, Henriquez-Roldan C. Assessing the capacity of health departments to engage in community-based participatory public health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):472–476. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD. Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(6):683–698. doi: 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahner SJ, Corrado SM. Local health department partnerships with faith-based organizations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(3):258–265. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begley CE, Fourney A, Elreda D, Teleki A. Evaluating outcomes of HIV prevention programs: lessons learned from Houston, Texas. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(5):432–443. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.432.24079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yancey AK, Lewis LB, Sloane DC, et al. Leading by example: a local health department-community collaboration to incorporate physical activity into organizational practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(2):116–123. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards T, Richards L. The NUDIST Qualitative Data Analysis System. Qual Sociol. 1991;14(4):307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles M, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed May 2, 2008];Tacoma Pierce County Cross Cultural Collaborative of Pierce County. http://www.tpchd.org/page.php?id=300. Published November 8, 2006.