ABSTRACT

PROBLEM BEING ADDRESSED

Research is not perceived as an integral part of family practice by most family physicians working in community practices.

OBJECTIVE OF THE PROGRAM

To assist community-based practitioners in answering research questions that emerge from their practices in order for them to gain a better understanding of research and its value.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

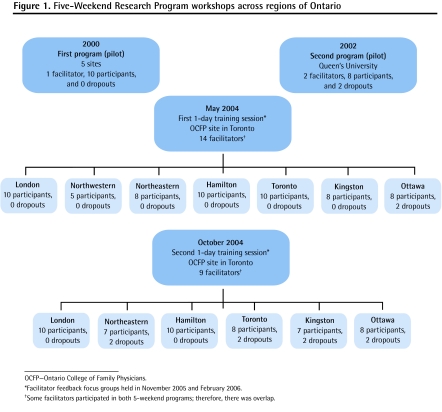

The Ontario College of Family Physicians developed a program consisting of 5 sets of weekend workshops, each 2 months apart. Two pilots of the 5-weekend program occurred between 2000 and 2003. After the pilots, thirteen 5-weekend programs were held in 2 waves by 20 facilitators, who were trained in one of two 1-day seminars.

CONCLUSION

This 5-weekend program, developed and tested in Ontario, stimulates community practitioners to learn how to answer research questions emerging from their practices. A 1-day seminar is adequate to train facilitators to successfully run these programs. Evaluations by both facilitators and program participants were very positive, with many participants stating that their clinical practices were improved as a result of the program. The program has been adapted for residency training, and it has already been used internationally.

RÉSUMÉ

PROBLÈME À L’ÉTUDE

Pour plusieurs médecins de famille exerçant en milieu communautaire, la recherche n’est pas perçue comme une partie intégrale de leur pratique.

OBJECTIF DU PROGRAMME

Aider les médecins exerçant en milieu communautaire à répondre aux questions de recherche qui se posent dans leur pratique pour qu’ils comprennent mieux la recherche et son intérêt.

DESCRIPTION DU PROGRAMME

Le Collège des médecins de famille de l’Ontario a développé un programme qui consiste en 5 fins de semaines d’ateliers à des intervalles de 2 mois. Deux essais pilotes de ces programmes de 5 fins de semaines ont eu lieu entre 2000 et 2003. À la suite de ces essais, 13 programmes de 5 fins de semaines ont été tenus en 2 vagues par 20 moniteurs qui avaient été formés dans l’un des 2 séminaires d’un jour.

CONCLUSION

Grâce à ce programme de 5 fins de semaines créé et testé en Ontario, les cliniciens communautaires savent mieux résoudre les questions de recherche qui surviennent dans leur pratique. Un séminaire d’une journée suffit pour bien former les moniteurs qui animent ces programmes. Les moniteurs et les participants ont évalué ces programmes de façon très positive, plusieurs participants déclarant que le programme avait amélioré leur pratique. Le programme a été adapté pour la formation des résidents, et il est déjà utilisé dans d’autres pays.

Traditionally, family physicians working in community-based practices have not viewed research as an important part of their clinical practices. Family medicine residents tend to have negative opinions about conducting small projects during their training.1 There is evidence that deans of medical schools in the United States perceive departments of primary care or family medicine as being strong in the realm of teaching and weak in the area of research.2 More than 95% of students graduating from Canadian medical schools stated they would never consider family medicine as a career if they were interested in research.3

Over the past 2 decades a number of strategies have been developed in several countries to address the perceived deficiency in family medicine research.4–9 These strategies have all been designed to build research capacity in academic departments of family medicine. In 2004, a report by the American Academy of Family Practice stated the following: “Participation in the generation of new knowledge will be integral to the activities of all family physicians and will be incorporated into family medicine training. Practice-based research will be integrated into the values, structures, and processes of family medicine practices.”10 In 2007, the WONCA Research Working Group adopted the concept that every family practice in the world should be involved in generating new knowledge.11

In order to stimulate interest in research and capacity building for its more than 6500 practising family physician members, the Ontario College of Family Physicians (OCFP) supported a project called the 5-Weekend Research Program. The 5-weekend program style emerged from business schools that used this method to promote on-the-job skills enhancement of business leaders. In the mid 1990s, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto in Ontario developed a 5-weekend leadership program. The 5-weekend program format was practical for busy clinicians, resulting in the development of a variety of new programs (eg, sports medicine, psychotherapy, and working with families).12

The format of 5-weekend programs (Table 1) allows working individuals to train while maintaining their regular professional responsibilities. Participants lost only a half-day of work 5 times over a period of 10 to 12 months. Each weekend program began at noon on a Friday and ended at noon on a Sunday. Most of the work was done during the 2 months between each weekend session. A key aspect of this program was being part of a group process—every member of the group participated in all projects developed by the group.

Table 1.

The format of a weekend session: Weekends were used to minimize intrusion on clinical practice time.

| SESSION | DAY | ACTIVITY |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Half-day Friday afternoon | Participants are given 15 minutes each to explain what they have achieved since their last weekend session 2 months ago in order to answer their research questions. The group then provides suggestions for 15 minutes. |

| 2 | All day Saturday | Participants receive the core instruction for the new module. This is presented during small group discussions. Individuals are encouraged to discuss their own research questions during the discussion. |

| 3 | Sunday morning (2–3 hours) | Participants are asked to develop plans for what they will do during the next 2 months. The plans need to include timelines, required resources, and any other needs. Participants are given 10 minutes each to present their plans and receive feedback from colleagues. |

The first pilot of the 5-weekend research program had 10 volunteer participants from 5 regions of Ontario who responded to an advertisement in the OCFP newsletter. Each regional medical school hosted 1 of the weekend sessions, resulting in a high cost for travel and accommodations for the facilitator and participants. A second pilot program was held at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont, which reduced costs substantially but was geographically limiting for participants. After the pilots, with a grant of $960 000 from the Primary Health Care Transition Fund to the OCFP in 2003, a total of thirteen 5-weekend programs were held across 7 regions of the province over a period of less than 2 years (Figure 1). The objective of the program was to stimulate community-based clinicians to better understand research methods and to see how this understanding could benefit their daily practices. This paper reports on how preparing facilitators with 1-day workshops for the program resulted in achieving the objective. We hypothesized that efficient facilitator training would make the program practical to use, both nationally and internationally.

Figure 1.

Five-Weekend Research Program workshops across regions of Ontario

Methods

In order to achieve the goal of stimulating interest in research among community clinicians across the province, we used a train-the-trainer method for facilitators. The grant was for running a 5-weekend program twice at each family medicine teaching site in southern Ontario and 2 sites in northern Ontario; the two 5-weekend programs at each site were held 10 to 12 months apart. Because the grant was available for less than 2 years, the 2 courses overlapped at each site. Although our objective was to provide the 1-day seminar for a minimum of 2 facilitators for each of the 7 sites, we held 2 facilitator training sessions for a total of 20 facilitators. During a period of less than 2 years, there were thirteen 5-weekend programs completed in total. (Only 1 program was completed in the northwestern region owing to sudden loss of the facilitator.) Each of the programs consisted of 5 to 10 participants who signed up to take the intensive research workshops to learn how to answer research questions arising from their clinical work. Group size was limited to a maximum of 10 because of the intensity of the program, the amount of 1-on-1 interaction, group discussions, and individual feedback built into the program.

Selection and preparation of facilitators

In 2004, the first step in the new program was to identify and train facilitators for each of the 7 sites and assist them with recruiting participants at their own sites. Over a period of several months, the departments of family medicine that received the grant to operate the program at the 7 sites identified 20 facilitators. Table 2 outlines the backgrounds of all the facilitators.

Table 2.

Description of the 20 facilitators

| FACILITATORS | UNIVERSITY |

|---|---|

| 1 academic family physician; 1 research manager; 2 community-based family physicians* | Queen’s University |

| 1 academic family physician; 1 community-based family physician* | University of Ottawa |

| 1 academic family physician; 1 community-based family physician; 1 research assistant | University of Toronto |

| 1 community-based family physician; 1 academic social worker; 3 research assistants | University of Western Ontario |

| 1 community-based family physician; 1 research assistant | Health Sciences North |

| 1 researcher | McMaster University |

| 1 community-based family physician*; 1 academic family physician; 1 research assistant | Northern Ontario School of Medicine |

Completed a previous 5-weekend program.

The facilitators were expected to have interest in research and experience in the academic setting; they were primarily identified through the research divisions of the departments of family medicine at their universities. Facilitators were responsible for recruiting participants for their local programs, establishing weekend dates, and organizing meeting sites, food, and methods of communication. They were provided with honoraria and limited secretarial support through the local family medicine departments. Facilitators were also expected to keep in contact with family physician participants during the 6- to 8-week gap between each weekend session. Facilitator training occurred at two 1-day seminars held at the OCFP office in Toronto. Facilitators were supported and trained by the 3 coauthors who were based at Queen’s University. The OCFP provided administrative support for the program.

The facilitator seminar began with an introductory dinner the evening before. We wished to establish an atmosphere of friendly and collegial support that would be continued at each site. Each facilitator was provided with a manual, which they were encouraged to customize for their own groups and universities. They were also provided with a CD-ROM containing all of the materials in the manual, so that they could easily customize the content. The introduction to the workshop reviewed the history of the 5-weekend research program, outlined the program’s objectives (Box 1), and explained feedback from previous programs. After each module’s content and rationale were presented (Table 3), the facilitators worked in small groups to discuss problems, barriers, and possible methods of implementation at their sites. The results of each small group were presented to the large group for suggestions and discussion; this process was repeated for each of the 5 modules. The final step for the day was a general open discussion about concerns or questions.

Table 3.

The modules for each weekend of the 5-weekend program

| WEEKEND | TOPICS |

|---|---|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

Evaluation by facilitators

Facilitators were asked to complete feedback forms after each of their 5 weekend sessions. This was not anonymous, but the facilitators also asked for the responses of participants to the program, and participant feedback was anonymous. Facilitators were also invited to attend a 1-day focus group to share their experiences, debrief, and provide suggestions for improvement. A focus group priority setting survey was sent out to the facilitators before the agenda was set for the focus groups (Table 4). The 2 focus group sessions were led by 2 or 3 of the authors with between 12 and 14 facilitators present at each session. The focus groups were structured to allow for reports on each individual program’s successes and failures as well as a general discussion on the overall organization and structure of the program. Not only did the focus groups allow us to capture information for purposes of evaluating the course delivery, but they also allowed us to learn about the facilitators’ strengths and weaknesses and how the program provided them with encouragement and confidence. The discussion reinforced the group dynamics, thereby fostering closer ties between the facilitators from the various participating medical schools and strengthening their networking abilities.

Table 4.

Facilitator focus group priority setting survey

| STATEMENTS | AGREE, % | NEITHER AGREE NOR DISAGREE, % | DISAGREE, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| The specific objectives for this course were achieved | 55.6 | 33.3 | 11.1 |

| The deliverables for this course were appropriate | 66.7 | 11.1 | 22.2 |

| The manual for this course was a good primer for teaching the course | 88.9 | 11.1 | 0 |

| There was sufficient administrative support for this project | 66.7 | 11.1 | 22.2 |

| The materials prepared for this course were appropriate | 88.9 | 11.1 | 0 |

| The manner in which the 5 weekends were structured worked well | 88.9 | 11.1 | 0 |

| When I needed support or direction I knew whom to contact | 44.4 | 22.2 | 33.3 |

| I was well prepared to offer this course | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0 |

| There was evidence that the course changed individuals’ attitudes toward research in family medicine | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Box 1. Objectives of the 5-weekend program.

On completion of the program the participants will ...

have a better appreciation of the benefits of research conducted in the context of family practice;

become more sophisticated as consumers of the research published in medical literature, and be able to better critique the literature and determine its relevance to their patients and the contexts in which they practice;

become more proficient in literature searching and be able to produce systematic reviews related to their research questions;

have basic knowledge of quantitative and qualitative research methods and how to use them appropriately;

design grant applications and estimate the costs involved; and

submit their grant applications in collaboration with researchers.

The written feedback from the focus groups invited qualitative comments and suggestions for improvement. Notes were taken at the facilitator focus groups, recording comments and suggestions. This information was collated and analyzed by the authors. All reports from focus group sessions were produced in draft form and reviewed and corrected by the participants; then a final report was circulated.

Role of participants

Most of the participants were community-based family physicians with little or no research experience. In total, there were a little more than 100 participants in the thirteen 5-week programs, with some sessions being overbooked and others having difficulty recruiting 10 participants. A number of participants came from other aspects of primary care—including midwifery, social work, and nursing—as enrolment was opened to all primary care practitioners. As the participants remained anonymous (for required confidentiality) to the central evaluators, detailed information was not available. We believe that about half the participants were female and that community-based family physicians comprised about 70% of the group. A few of the participants had been interested in research during their education or early in their careers but had not kept up with research once they established community practices.

Participants were expected to attend all sessions and present completed research proposals to their peers on the fifth weekend. During the 6- to 8-week periods between weekends, participants had to complete “gap work,” which would help develop their research understanding and skills, as well as help with the design and completion of their research proposals. Participants were also asked to complete feedback forms at the end of each weekend. They were asked to rate aspects of several dimensions of the program and were encouraged to make comments and suggestions about the program and their learning experiences. Participants’ evaluation forms were nearly identical to the facilitators’ evaluation forms, except that participant forms asked about their experience as learners rather than facilitators. Participants were also asked to provide feedback on the facilitators. The completed forms were collated by the authors.

Facilitator results

Some facilitators reported difficulty recruiting the suggested number of 10 participants for the first round of the 5-weekend program. Other facilitators were overwhelmed by the demand, with prospective participants very upset about having to wait for the second round of the program or not being able to participate. Recruiting for the second 5-week program was easier, as the first round of participants provided word-of-mouth advertising. The dropout rate varied greatly, (Figure 1). The most common reasons for dropping out were the time commitment or changes in family or practice situations.

The combination of providing secretarial support to facilitators, establishing the program in a university department, and making the facilitator responsible for all arrangements appeared to be effective. From the first 2 pilot sessions, we had determined that the dates of each of the weekend sessions of the 5-weekend program had to be established when the program was advertised or it became impossible to find suitable dates.

Feedback from facilitators was very positive in relation to the structure provided, the program organization, and facilitators’ workshop preparation for the program (Tables 5 and 6). There were some suggestions for improvement in the facilitator workshop as well as suggestions for changes to improve both the facilitator and participant manuals. The facilitators agreed that the 1-day seminars set the tone for the 5 weekend sessions and provided them with sufficient guidance to feel comfortable with the objectives and the most effective way to achieve them.

Table 5.

Survey results by facilitators and participants: Total responses measured on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing very high.

| QUESTIONS | FACILITATORS’ EVALUATIONS,* MEAN (SD) | PARTICIPANTS’ EVALUATIONS,* MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| What was the overall level of usefulness of information you presented/learned in this module? | 8.56 (1.16) | 8.77 (1.28) |

| How would you rate this module in terms of content? | 8.39 (1.35) | 8.63 (1.47) |

| How would you rate the module in terms of value to you? | 8.04 (1.64) | 8.74 (1.33) |

Surveys were completed after each module. A total of 55 facilitator surveys and 151 participant surveys were completed.

Table 6.

Feedback on the facilitator manual: Facilitator survey responses measured on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing very high; a total of 55 surveys were completed.

| STATEMENTS | FACILITATORS’ EVALUATIONS, MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|

| Appropriateness of information provided in facilitators’ manual | 7.26 (2.00) |

| Appropriateness of style in which material was presented in facilitator manual | 7.58 (2.00) |

There was considerable overlap, as many of the facilitators from the first set of sessions agreed to facilitate the second round. Both groups provided extensive feedback on the style with which they ran their sessions. Examples included 1 group using 4 to 5 facilitators and providing extensive contact and support between each session. Another group reduced the length of sessions to 1.5 days. Another group picked people who had already partially completed a project and provided them with the individual support that they needed. Several groups had research assistants with strong statistical backgrounds to help participants develop their methods.

Discussion from the facilitators focused on 2 issues. The first issue was the expected end product of the program. The manual stated that the expectation was a grant application that was specifically written for a chosen granting agency. On the whole, facilitators believed that this was an unrealistic goal for most of their participants, although at least 5 participants from 2 different sections did achieve this goal and 3 received funding. The facilitators believed that presentation of a concept paper by participants on the methods and strategy they would use to answer their question would be a more reasonable outcome. There was also concern over the fact that in Canada grants do not provide support for investigators, making grant applications for community clinicians unrealistic until such support could be found.

The second concern facilitators expressed was the order and sequence of the topics. Although there was little disagreement about the content of the topics covered in the program, the group was divided between those who thought that the order worked very well and those who thought that the program should be “front end loaded.” Some facilitators argued that all the topics should receive superficial coverage in the first 2 weekend sessions and then be revisited during the last 3 weekend sessions, when individuals were designing their projects in more detail. Facilitators maintained that individuals with little knowledge of research methods, ethical issues, or grant application strategies needed initial exposure to these topics in order to frame their research questions more appropriately. Participants could then seek more detailed input in the final weekend sessions to develop the strategy to answer their questions.

Participant results

The feedback received from participants was overwhelmingly affirmative. Analysis of comments and recommendations reflected the high appreciation the participants had for the facilitators, for the invited speakers, and for the program. Participants detailed their enjoyment of learning new skills, the frustrations of developing their proposals, and the excitement of new challenges. Particular importance was attached to the open, collegial atmosphere established by all the facilitators, which allowed participants to feel comfortable expressing their opinions about one another’s work. Participants reported enjoying the social networking and stimulating discussions with their peers (Table 5).

Participants did drop out of the program. The time commitment required on weekends as well as family and work demands meant that some of the participants had difficulty making the sessions or completing their gap work.

Discussion

Research capacity building in family practice is an important step to building the academic credibility of the discipline.13,14 Given the skills and a few resources, community practitioners could substantially contribute to family medicine research. The idea of educating a group of community-based clinicians in research methods, critical appraisal, and grant development is not recorded in the literature. We could find no other examples of seeking research questions from community practitioners and using the development of these questions as the basis for individuals to gain skills and knowledge in research methods.

Lessons learned

Individuals who raise questions from their clinical practices are motivated by their own curiosity. Participants viewed the creation of a “safe environment” in which to develop their questions by receiving input and support from a group of colleagues as a beneficial feature of the program. The connection with university departments and their resources provided a vehicle for building research capacity. Having a departmental connection resulted in nearly 50% of participants receiving university appointments. Of equal importance is the change in practitioners’ views on the value of critiquing the medical literature, making them more sophisticated consumers of medical literature. Most participants reported that their better understanding of research and the medical literature made them better clinicians for their patients. A number of participants claimed the program changed their entire orientation to clinical practice. This feedback suggested that one of the broader objectives of the program, which was to shift the culture of family practice toward a greater research orientation, was achieved.

The focus group feedback suggested that the structure of the program was appropriate but that there needed to be greater flexibility in how that structure was applied. The application was very dependent on local circumstances and the skills of the facilitators.

The success of the program was celebrated at the OCFP Annual Scientific Assembly, with a 5-Weekend Day. The 16 oral presentations and 8 displayed posters showed a combination of enthusiasm and tremendous diversity of interests among the participants.

The 1-day seminar for facilitator training was efficient, as it resulted in thirteen 5-weekend programs running successfully. The uniqueness developed in each centre was influenced by the resources available to the program, the actual questions being posed by the participants, and the creativity of the facilitators to accommodate the needs of participants. The facilitator seminar day has been presented in Spanish in Cali, Colombia, to 70 physicians from 18 South American countries. The positive reaction to the day supported the adaptability of the program to various cultural and language situations.

The program is being divided into 6 to 7 monthly or bimonthly 5-hour sessions for use in residency programs to help residents benefit from a stronger research orientation when they begin their practices. The emphasis in the residency version of the program will be on critical appraisal skills, and the end product will be a concept paper rather than a grant application. Residents need less emphasis on literature-searching skills, as they are well versed in this from medical school.

Limitations

The greatest limitation in describing this project was the confidentiality rules that prevented the evaluators from collecting any detailed information from participants or even directly contacting participants. The only other potential limitation is generalizability. While we believe that the process we described is adaptable to almost any research environment, it is likely that each academic, research, or clinical group deciding to conduct a 5-weekend program about research would need to adapt it to the realities and needs of the individuals involved. The program, however, is quite adaptable, so while the need to adapt it locally might be a limitation, its adaptability is a strength.

Conclusion

Thirteen 5-weekend programs have been successfully run following 1-day facilitator-training seminars. The 20 facilitators were from various backgrounds but were able to adapt to the needs of participants with eclectic research questions. Although each program had unique characteristics and had participants producing different products, all were assessed by participants as successful. A number of participants described considerable changes to the ways they perceived their practices. We believe that refinements resulting from this evaluation will provide a strategy for research capacity building, which can be adapted for use internationally, and will provide residents with improved education in research methods. If 5-weekend research programs occurred over a number of years, the culture of family medicine could shift to a greater research orientation.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The goal of the 5-Weekend Research Program was for community-based clinicians to better understand research and how it could benefit their daily practices.

Efficient facilitator training helped to achieve the objectives of the program.

Following these 5-weekend programs, many participants described considerable changes in the ways they perceived their practices.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Le but du programme de recherche de 5 fins de semaines était de permettre à des cliniciens exerçant dans la communauté de mieux comprendre ce qu’est la recherche et comment elle pourrait améliorer leur pratique quotidienne.

La formation de moniteurs efficaces a aidé à atteindre les objectifs du programme.

À la suite de ces programmes de 5 fins de semaines, plusieurs participants ont décrits d’importants changements dans leur façon de percevoir la pratique.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors

Dr Rosser, Dr Godwin, and Ms Seguin contributed to concept, design, and implementation of the program; data gathering; interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Morris BA, Kerbel D, Luu-Trong N. Family practice residents’ attitude towards their academic projects. Fam Med. 1994;26(9):579–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman RH, Wahi-Guruaj S, Alpert J, Bauchner H, Culpepper L, Heeren T, et al. The views of US medical school deans toward academic primary care. Acad Med. 2004;79(11):1095–102. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200411000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosser WW. The decline of family medicine as a career choice. CMAJ. 2002;166(11):1419–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeHaven MJ, Wilson GR, Murphree DD. Developing a research program in a community-based department of family medicine: one department’s experience. Fam Med. 1994;26(5):303–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto A, Nguyen TN, Nguyen TM, Hughes J. Building postgraduate capacity in medical and public health research in Vietnam: an in-service training model. Public Health. 2005;119(3):174–83. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JD, Longo DR. Building research capacity in family medicine: evaluation of the Grant Generating Project. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(7):593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Zee J, Kroneman M, Bolìbar B. Conditions for research in general practice. Can the Dutch and British experiences be applied to other countries, for example Spain? Eur J Gen Pract. 2003;9(2):41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer E, Weston K. A conceptual model for capacity building in Australian primary care research. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(12):1139–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaén CR, Borkan J, Newton W. The next step in building family medicine research capacity: finding the way from fellowship. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):373–4. doi: 10.1370/afm.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, Bucholtz JR, Dickinson JR, Evans KL, et al. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community leadership committee. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3–S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Organization of Family Doctors . WONCA bylaws. Singapore, Singapore: World Organization of Family Doctors; 2007. Available from: www.globalfamilydoctor.com/PDFs/2004%20Bylaws%20%20Regulations-RATIFIED%202007.pdf. Accessed 2010 Jan 21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot Y, Batty H, Rosser WW. Five Weekend National Family Medicine Fellowship Program for faculty development. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:2151–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Maeseneer JM, De Sutter A. Why research in family medicine? A superfluous question. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 2):S17–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbert CP. Future of research in family medicine: where to from here? Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 2):S60–4. doi: 10.1370/afm.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]