Abstract

Using daily diary methods, mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (n = 86) were contrasted with a nationally representative comparison group of mothers of similarly-aged unaffected children (n = 171) with respect to the diurnal rhythm of cortisol. Mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD were found to have significantly lower levels of cortisol throughout the day. Within the ASD sample, the son or daughter’s history of behavior problems interacted with daily behavior problems to predict the morning rise of the mother’s cortisol. A history of elevated behavior problems moderated the effect of behavior problems the day before on maternal cortisol level. Implications for interventions for both the mother and the individual with ASD are suggested.

Keywords: stress, cortisol, parenting, behavior problems, adolescents, adults

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) often report higher levels of stress and poorer psychological well-being than parents of children with other types of developmental disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Blacher & McIntyre, 2006; Eisenhower, Baker, & Blacher, 2005). Past research has examined various child-related factors that might explain this elevated level of psychological distress among parents of children with ASD, with findings consistently indicating that child behavior problems are significant sources of stress (Hastings et al., 2005; Herring et al., 2006; Lounds, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Shattuck, 2007). It is not known, however, whether this level of stress disturbs the physiology and health of these parents, highlighting a need for research on the biological markers of stress in families of individuals with ASD. The present study sought to address this gap by examining the associations between behavior problems in adolescents or adults with ASD and maternal salivary cortisol, a hormone secreted from the adrenal gland, in a sample of mothers and their adolescent or adult children with ASD.

Biological Markers of Stress

Cortisol is a hormonal marker of stress which has received considerable attention in studies of psychological and physical health. During exposure to an acute stressful event, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated and releases cortisol from the adrenal cortex into the bloodstream. Cortisol, in turn, acts on a variety of adaptive responses including protein synthesis and glucose regulation, immune function, and mental activity (Flinn, 2006). In the short term, these changes enable the body to respond to the immediate challenge (i.e., extending the “fight or flight” response induced by adrenaline); however, chronic stress and persistent activation of the HPA axis can have detrimental impacts on health and well-being, such as a suppression of bone growth and certain immune responses, as well as poorer cognitive performance (McEwen, 1998; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

A major methodological breakthrough for psychological research was achieved when it was shown that salivary cortisol level reliably reflected circulating hormone levels (Kirschbaum & Hellhammer, 1994), which enabled assessment of adrenal activity across the day in a noninvasive manner. The present study measured cortisol levels in mothers of individuals with ASD via saliva samples collected at four times during the day over a four-day period. Cortisol typically follows a clear daily rhythm, with peak values seen shortly after waking up in the morning and declines occurring throughout the day until bedtime. By collecting daily measures of subjective stress and daily salivary specimens, we were able to extend prior research on the impact of familial stress to mothers whose son or daughter has ASD, a group for which cortisol regulation had not previously been investigated. By focusing on mothers of adolescents and adults with ASDs (as opposed to mothers of young children on the autism spectrum), we were able to investigate the effects of chronic as well as daily parenting stress.

Psychological Stress and Cortisol Response

In past research on individuals experiencing chronic stress, it was initially expected that heightened cortisol levels would be the pattern associated with sustained demand and challenge. However, in a review by Gunnar and Vazquez (2001), it was observed that chronic stress is in fact associated with reduced cortisol levels in multiple populations. For instance, in comparison to parents of healthy children, parents of children with cancer showed flatter diurnal slopes due to a reduction in cortisol at one hour after awakening (Miller, Cohen, & Ritchey, 2002). Blunted cortisol responses have likewise been seen among combat soldiers, Holocaust survivors, and individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (Heim, Ehlert, & Hellhammer, 2000; Yehuda, Boisoneau, Lowy, & Giller, 1995; Yehuda, Kahana, et al., 1995). There also appears to be an association between the severity of stress and the impact on the HPA-axis. For example, in a study of employees with clinical burnout, more severe burnout symptoms were associated with lower cortisol awakening response (Sonnenschein et al., 2007). Taken together, these findings highlight the fact that the hormonal response to chronic stress is quite different than the immediate elevation of cortisol seen after acute challenges.

To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined cortisol levels in families of children with ASD, although past research has investigated the cortisol rhythms of parents of children with other types of disabilities. Seltzer, Almeida, Greenberg, Savla, Stawski, Hong, and Taylor (2009) compared parents of adolescents and adults with developmental disorders and mental health problems with parents of similarly-aged children who did not have disabilities or chronic health conditions. Disabilities in children in the Seltzer et al. (2009) study included attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (15.9%), bipolar disorder (12.2%), schizophrenia (9.8%), depression (7.3%), Down syndrome (6.1%), and others. The findings indicated that parents of a son or daughter with a disability had a normative daily rise of salivary cortisol but a significantly less pronounced daily decline of cortisol when compared to parents of children without disabilities, a pattern that was most pronounced on days when the parents spent more time with their children (Seltzer et al., 2009). These findings provide some indication of a dysregulated pattern of cortisol activity. However, the heterogeneous range of disabilities in the children may have obscured diagnostic-specific patterns.

Present Study

The present study extended these findings not only by focusing on mothers of individuals with ASD, but also by investigating the role of child-related stress, specifically behavior problems, in predicting cortisol levels within the ASD group. We examined daily behavior problems in predicting daily maternal cortisol response as well as how the child’s behavior problem history conditioned the mother’s response to the behavior problems manifested by her child on a given day. Past longitudinal studies (e.g., Lounds et al., 2007) have shown that behavior problems manifested by a child with ASD have a long-term effect on maternal well-being. Thus, it may be valuable to determine how a mother’s response to acute behavior problems interacts with her son or daughter’s history of behavior problems in producing the maternal cortisol response.

The present study had four aims. First, in order to profile the diurnal pattern of cortisol activity characteristic of mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD, we investigated whether these mothers differed from a comparison group of mothers of similarly-aged children without disabilities on measures of salivary cortisol collected at four points across the day: awakening, 30 minutes after awakening, before lunch, and before bedtime. Second, within the ASD group, in order to elucidate how chronic stress may affect cortisol levels, we examined the impact of history of child behavior problems by comparing the cortisol levels of mothers of adolescent and adult children with a history of clinically-significant levels of behavior problems to mothers whose son or daughter had a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems.

Third, in order to investigate how acute stress may simultaneously affect cortisol levels, we examined the impact of daily behavior problems on the diurnal rhythm of cortisol among mothers of a son or daughter with ASD, using multilevel modeling. Finally, also using multilevel models, we estimated the interaction of daily behavior problems with behavior problem history in predicting maternal cortisol levels, in order to explore whether chronic stress moderates daily stress.

Consistent with prior studies of parents with stressful caregiving experiences (Miller et al., 2002), we hypothesized that mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD would have significantly lower levels of daily cortisol secretion throughout the day than mothers of unaffected, similarly-aged children. We also expected that mothers of children with ASD who had a history of clinically-significant levels of behavior problems would have lower cortisol levels than mothers of children with a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems, reflective of the effects of chronic stress.

Based on past research findings indicating a strong association between child behavior problems and parental psychological stress (Hastings et al., 2005; Herring et al., 2006; Lounds et al., 2007) and studies showing that day-to-day experiences can affect subsequent daily variations in cortisol secretion (Adam, Hawkley, Kudielka, & Cacioppo, 2006; Eller, Netterstrom, & Hansen, 2006), we hypothesized that when adolescents and adults with ASD had multiple behavior problems on a given day, their mothers would show a more pronounced cortisol response to awakening the next day than mothers whose son or daughter with ASD had fewer behavior problems the day before. Finally, we explored whether the behavior problem history of the adolescent or adult with ASD would moderate the effects of daily behavior problems on maternal cortisol. Specifically, we explored whether the impact of frequent daily behavior problems would be less pronounced for mothers whose adolescent or adult child had a history of elevated levels of behavior problems than for mothers whose child had a history of low levels of behavior problems. Mothers who are exposed chronically to high levels of behavior problems may be less reactive to daily behavior problems than mothers from whom this degree of stress is unusual.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from two longitudinal studies. The target group of mothers was obtained from an ongoing longitudinal study of adolescents and adults with ASD (the AAA study; Lounds et al., 2007; Seltzer et al., 2003; Shattuck et al., 2007). The comparison group of mothers was obtained from a nationally representative study of individuals in the National Survey of Midlife in the United States (the MIDUS Study; Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004; Gruenewald, Mroczek, Ryff, & Singer, 2008, described below).

AAA Study

Mothers in the AAA study were recruited via service agencies, schools, diagnostic clinics, and media announcements. At entry into the study, families met three criteria: (a) the family included a child 10 years of age or older; (b) the child had received a diagnosis of ASD from a medical, psychological, or educational professional, as reported by parents; and (c) scores on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter, & Le Couteur, 1994; Rutter, Le Couteur, & Lord, 2003), administered by research staff, were consistent with the parental report of an ASD. Nearly all (94.6%) of the sample members met the ADI-R lifetime criteria for a diagnosis of Autistic Disorder. Case-by-case review of the other sample members (5.4%) determined that their ADI-R profile was consistent with their autism spectrum diagnosis (i.e., meeting the cutoffs for reciprocal social interaction and repetitive behaviors for Asperger’s Disorder, and meeting the cutoff for reciprocal social interaction and the cutoff for either impaired communication or repetitive behaviors for PDD-NOS).

Initially, 406 mothers of individuals with ASD participated in the AAA study, which began in 1998. Between 1998 and 2005, data were collected from mothers at four points in time, about once every 18 months, spanning about a 4.5 year period for each mother. During 2006–2007, the AAA Daily Diary Study was conducted (described more fully below), providing daily data over an 8-day period. The Daily Diary protocol, which was modeled after the Daily Diary Study of MIDUS (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002), consisted of short telephone interviews conducted with the mother at the end of each of eight consecutive days, with cortisol measured four times a day on Days 2 through 5.

An additional criterion for participation in the AAA Daily Diary Study was that the son or daughter with ASD lived at home with the mother. When the AAA study began in 1998, the full sample was comprised of 264 individuals with ASD who lived with their families and 142 who lived away from home. An increasing proportion of individuals moved away from the family home at each subsequent point of data collection, such that by the time of the AAA Daily Diary Study, only 136 individuals with ASD remained co-resident with their parents.

Of the 136 mothers who were potential participants in the AAA Daily Dairy Study, 6 could not be reached and 34 declined participation in this component of the AAA study, resulting in 96 mothers who participated in the AAA Daily Diary Study. Of these, 3 mothers declined to participate in the cortisol collection, and 7 mothers did not provide complete data on daily medication use, which was needed for the present analysis. Thus, AAA participants in the present set of analyses consisted of a sub-sample of 86 mothers. The adolescents and adults with ASD in this subsample ranged in age from 18 to 53 years of age (M = 24.7 years, SD = 7.24). The majority of the sample members were male (79.1%).

Just over half (57%) of the sample members had an intellectual disability (ID). ID status was determined using a variety of sources. Standardized IQ was obtained by administering the Wide Range Intelligence Test (WRIT; Glutting, Adams, & Sheslow, 2000) and adaptive behavior was assessed by the Vineland Screener (Sparrow, Carter, & Cicchetti, 1993). Individuals with standard scores of 70 or below on both measures were classified as having ID, consistent with diagnostic guidelines (Luckasson et al., 2002). For cases where the individual with ASD scored above 70 on either measure, or for whom either of the measures was missing, a review of records by three psychologists, combined with a clinical consensus procedure, was used to determine ID status.

MIDUS Comparison Group

A comparison sample of 171 mothers of co-residing sons and daughters without disabilities was drawn from the National Study of Daily Experience (NSDE), one of the projects comprising the National Survey of Midlife in the United States (MIDUS). MIDUS is a nationally-representative study of English-speaking, non-institutionalized adults who were aged 25 to 74 in 1994 (MIDUS I; Brim et al., 2004; Gruenewald, Mroczek, Ryff, & Singer, 2008). Data used in the present analysis were collected from 2003 to 2005 as part of a second wave of data collection (MIDUS II). There were 1265 individuals in the MIDUS II sample who participated in the NSDE (David Almeida, PI), referred to here as the MIDUS II Daily Diary Study.

For our comparison sample, we excluded 558 of the 1265 cases in which the respondent was male (as the AAA study consisted exclusively of mothers) and 66 cases where the respondent was female but had a child with a developmental disability or mental health condition. Additionally, 421 female respondents were excluded because they did not have any children living in their home, resulting in a potential comparison group of 230 mothers of co-residing, similarly-aged children without disabilities. Of the 230 mothers, 59 were excluded from the analysis because they did not provide complete information about medication use. The remaining 171 sample members constituted the comparison group for this analysis.

AAA versus the comparison group

The two groups of mothers were similar in terms of educational attainment, household income, marital status, and number of children (see Table 1). However, the mothers in the AAA sample were more likely to take medications during the study period, χ2 = 4.68 df = 1, p < .05, and therefore this variable was controlled in the between-group analysis (described below). In addition, the mothers in the AAA sample were significantly older than those in the comparison sample, t = 2.82, df = 255, p < .01; therefore, maternal age was controlled in the between-group analyses.

Table 1.

Comparison of Background Characteristics of Mothers in the AAA and Comparison samples.

| AAA vs. Comparison | N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educationa | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

2.95 3.12 |

.95 .77 |

| Household incomeb | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

10.6 10.4 |

3.7 3.1 |

| Marital status (0 = not married/1 = married) | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

.743 .791 |

.44 .41 |

| Mother’s age** | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

50.1 53.9 |

10.9 8.5 |

| Number of children | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

2.63 2.74 |

1.38 1.28 |

| % sons among co-residing children % sons among target children |

0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

49.4% 79.1% |

|

| Taking any prescription medication during cortisol collection (0 = No/1 = Yes)* | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 86 |

.50 .64 |

.501 .438 |

p < .05,

p < .01

education levels: 1 = less than high school, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some college, 4 = college graduate

income levels: (1) $0 to $4,999, (2) $5,000 to $9,999, (3) $10,000 to $14,999, (4) $15,000 to $19,999, (5) $20,000 to $24,999, (6) $25,000 to $29,999,(7) $30,000 to $34,999, (8) $35,000 to $39,999, (9) $40,000 to $44,999, (10) $45,000 to $49,999, (11) $50,000 to $59,999, (12) $60,000 to $69,999, (13) $70,000 or higher

As noted earlier, consistent with ASD prevalence data (APA, 2000), the majority of the children in the AAA sample were sons (79%). Because the MIDUS study was not originally designed as an investigation focusing particularly on parenting, mothers in the MIDUS sample did not designate a target child, precluding controlling for child gender in the current analyses. However, for descriptive purposes, we calculated the proportion of coresiding children of the comparison group who were sons versus daughters, which we expected to be equal. As expected, in the comparison sample, the proportion of co-residing sons was 49.7%.

Among both the AAA and the comparison groups, there were no significant differences in mothers’ socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., maternal education, income, marital status, age) between sample members included in the analysis and those excluded.

Procedure

For the AAA study, mothers participated in four in-home interviews, each spaced 18 months apart, that typically lasted two to three hours, and they completed standardized self-administered measures. The present analysis used measures of behavior problems (described below) obtained in the Time 1, Time 2, Time 3, and Time 4 interviews.

For both the MIDUS and the AAA studies, the Daily Diary protocol involved telephone interviews with mothers each evening for a period of 8 days. The daily telephone interview, which lasted approximately 15–25 minutes, included questions about daily experiences in the previous 24 hours. Data about medications taken each day were also used in the present analysis for control purposes. Daily Diary interviews for both groups were conducted by the Survey Research Center at The Pennsylvania State University. This ensured that the procedures for interviewing mothers in the AAA and MIDUS studies were identical. Several additional questions were included in the telephone interviews for the AAA sample, including the daily measures of behavior problems. The Daily Diary protocol is described in detail in Almeida et al. (2002) and its use with our sample of mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD is described in Smith, Hong, Seltzer, Greenberg, Almeida, and Bishop (2009).

For the cortisol analyses, mothers provided four saliva samples each day on Days 2 through 5 of the 8-day Diary Study period to be assayed for cortisol: one upon awakening, a second 30 minutes after awakening, a third before lunch, and a final sample at bedtime. Respondents received a Home Saliva Collection Kit one week prior to their initial phone call. Saliva was obtained using Sarstedt salivette collection devices. Sixteen numbered and color-coded salivettes were included in the collection kit, each containing a small absorbent cotton pad, about 3/4 of an inch long, as well a detailed instruction sheet. In addition to written instructions, study staff reviewed the collection procedures and answered any questions. Mothers were instructed to collect their first saliva sample before eating, drinking or brushing their teeth. They were also asked not to consume any caffeinated products (coffee, tea, soda, chocolate, etc.) before taking their subsequent samples throughout the day.

Data on the exact time respondents provided each saliva sample were obtained from the nightly telephone interviews and on a paper-pencil log sent with the collection kit. In addition, approximately 25% of the MIDUS respondents received a “smart box” in which to store their salivettes. These boxes contained a computer chip that recorded the time respondents opened and closed the box. The correlations between self-reported times and the times obtained from the “smart box” were high: .93 for the wake-up collection time, .95 for the collection 30 minutes after awakening, .83 for the lunchtime collection, and .75 for the evening occasion.

Measures

Cortisol

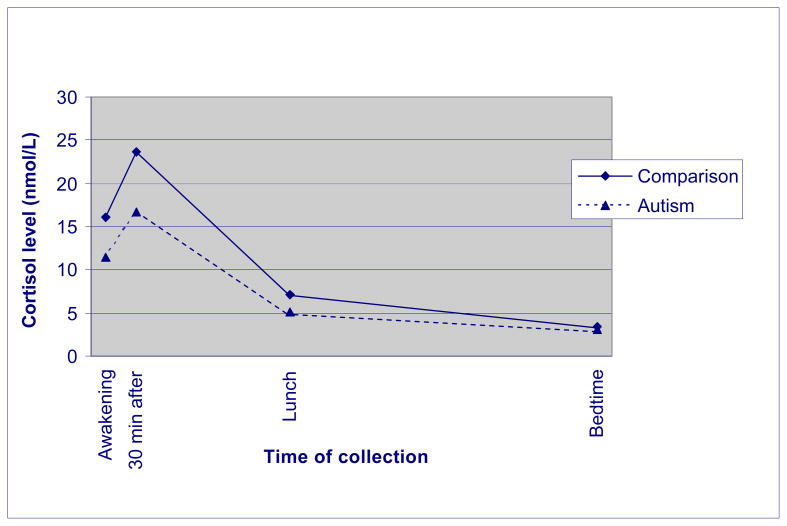

Two types of cortisol measures were used as dependent variables. First, we measured the level of cortisol at each of the four collection points. Second, we computed the awakening response. The awakening response, or “morning rise,” is defined as the increment between the cortisol value obtained upon awakening and the value 30 minutes later. Cortisol data was log transformed because typically, raw cortisol levels have positively skewed distributions. Therefore, we used the natural log of cortisol to adjust the skewness in the multilevel models (described below). However, raw cortisol levels were used in Figures 1–2 to facilitate interpretability of data. To minimize the influence of extreme outliers, salivary cortisol values higher than 60 nmol/l were recoded as 61, before the log transformation, following the statistical approach recommended by Winsor (Dixson & Yuen, 1974; Wainer, 1976). Only a small percentage of sample members were extreme outliers (n = 4, 4.7% of cases for the AAA sample and n = 19, 11.1% of cases for the MIDUS comparison group). An outlier was identified if at least one collection, out of a maximum of 16, had a cortisol value higher than 60.

Figure 1.

Average cortisol levels of AAA and comparison groups

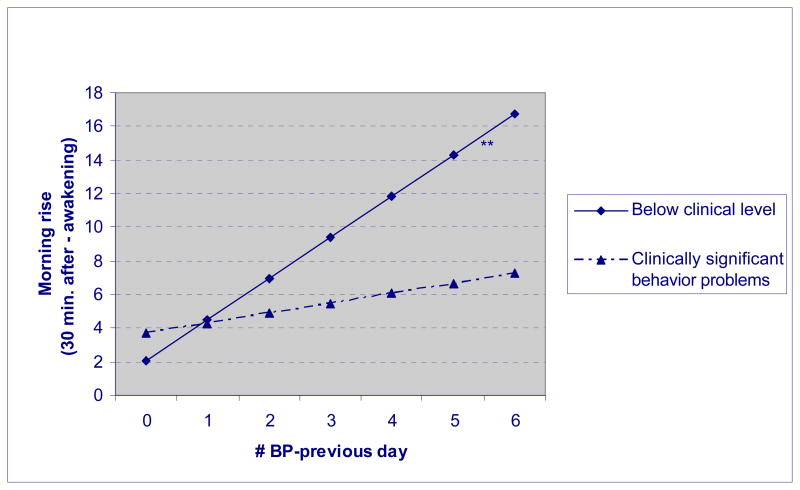

Figure 2.

Morning rise of cortisol by daily behavior problems and history of behavior problems.

Behavior Problems

For the within-group AAA analyses, two measures of behavior problems were used. One reflected the manifestation of behavior problems on each day during the AAA Diary Study (referred to as daily behavior problems), while the other was based on the behavior problems manifested during the Time 1 through Time 4 points of data collection in the AAA study (referred to as the history of behavior problems). Both measures of behavior problems were based on the Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996). The SIB-R scales assess eight types of behavior problems: behaviors that are hurtful to self, unusual or repetitive, withdrawn or inattentive, socially offensive, uncooperative, hurtful to others, destructive to property, and disruptive. The SIB-R is a measure of behavior problems developed for the broad population with developmental disabilities. Some of the types of behavior problems are inherent to autism (e.g., unusual or repetitive behaviors), while others are more common across developmental disabilities of a variety of etiologies (e.g., uncooperative behavior).

For the history of behavior problems measure, at Time 1 to Time 4, mothers were asked to indicate if their son or daughter with ASD had manifested each of the eight behavior problems during the previous 6 months and, if so, to rate the frequency of each behavior problem (ranging from 1 = less than once a month to 5 = one or more times an hour) and its severity (1 = not serious to 5 = extremely serious). Using standardized algorithms (Bruininks et al., 1996), frequency and severity scores were translated into a summary score at each time point. The reliability and validity of the SIB-R has previously been shown to be excellent (Bruininks et al., 1996). Higher scores on the SIB-R reflect more severe behavior problems.

For the history of behavior problems measure, the mean value of the four SIB-R measures obtained at the Time 1 to Time 4 points of data collection was calculated and used in the multilevel models. There was a high level of stability of SIB-R scores from Time 1 to Time 4; intercorrelations of the four scores across this time period averaged .67. Further, for descriptive purposes and to graph the interaction findings, the sample was divided into two groups those above and below a score of 110, which is the cut-off point between clinical and non-clinical behavior problems (Bruininks et al., 1996). The sample was evenly divided between those above clinical levels of behavior problems (n = 44, 51.2%) and those below clinical levels (n = 42, 48.8%).

The daily behavior problems measure reflected a count of the number of behavior problems mothers reported their son or daughter with ASD had on a given day, which was a modification of the standard approach to administering the SIB-R. During the Daily Diary interview, mothers indicated if their child manifested each type of behavior problem that day (each coded 1 if yes and 0 if no), and the total number of “yes” responses was computed for each day. Due to a clerical error, the “disruptive behavior” item was omitted from the Diary Study, and thus the total number of daily behavior problems ranged from 0 to 7. Although the SIB-R was scored differently for the history and daily measure, the correlation between the two measures was .63.

Control Variables

For the between-group analyses, control variables included maternal age and whether the mother took prescription medications during the Diary Study (0 = no, 1 = yes), which are the two variables on which the AAA and comparison groups differed significantly. We also included saliva collection time at each of the four collection points, as a method of controlling the chronobiology of cortisol (Keenan, Licinio, & Veldhuis, 2001).

For the within-group analyses, control variables included characteristics of the mother and the son or daughter with ASD. Characteristics of the mother included age, education, marital status, the number of children in the family, medication status, and awakening saliva collection time (Keenan et al., 2001). Maternal education was measured using an ordinal scale (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some college, 4 = college graduate). Marital status was a dichotomous variable (1 = married, 0 = not married). The number of children in the family included all children, living in the home or elsewhere, and medication status indicated whether the mother took any prescription medications. We also controlled whether or not the son or daughter with ASD also had intellectual disability (1 = yes, 0 = no) and child gender (1 = male, 0 = female).

Data Analysis Plan

First, for the between-group analyses, mothers who had a son or daughter with ASD were compared to mothers of similarly-aged children without disabilities with respect to cortisol levels at each collection point. We used repeated measures MANOVA and multilevel models using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) software (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to examine the extent to which mothers who had a son or daughter with ASD differed from the comparison group in daily cortisol levels at each of the four time points (awakening, 30 minutes after awakening, before lunch, and before bedtime). In the multilevel models, covariates included maternal age, whether the mother was taking prescription medications during the Diary Study, and the time that cortisol was collected at each time point.

Next, the AAA sample was divided into two groups (i.e., mothers of those with a clinically significant history of behavior problems and mothers of those with a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems, divided at the SIB-R score of 110) and their cortisol levels were compared.

Finally, for the AAA group, we examined how behavior problems manifested by the son or daughter with ASD the previous day were related to maternal cortisol activity, using multilevel models predicting the cortisol awakening response. We focused on the awakening response parameter (from awakening to 30 minutes after awakening) because we expected that the morning rise would be more sensitive to behavior problems manifested by the son or daughter on the prior day than would cortisol collected later in the day. By asking whether behavior problems have a lagged (i.e., next day) effect, rather than examining a simultaneous (i.e., same day) effect, we will be able to more confidently interpret the direction of effects as extending from behavior problems to cortisol response.

For these analyses, both the history and the daily measures of behavior problems were used to assess between- and within-person associations. History of behavior problems (a person-level predictor) was used to assess whether mothers whose son or daughter had higher levels of behavior problems differed in cortisol activity compared to mothers whose child had lower levels of behavior problems. The daily measure of problem behavior (a day-level predictor) was used to reveal within-person associations. We first estimated the main effects of the history and daily behavior problem measures (Models 1 and 2, respectively). Next, we estimated a model testing the interaction effect between the history and daily measures (Model 3). In these models, the covariates included maternal education, age, marital status, number of children in the family, whether the mother was taking prescription medication during the Diary Study, awakening collection time, whether the child had an intellectual disability, and the gender of the son or daughter with ASD. Note that in the within-group multilevel models, the history of behavior problems variable was a continuous measure, but the dichotomized measure was used to graph the interaction in Figure 2.

Findings

Between Group Analysis of Cortisol Activity

We first sought to determine whether the diurnal rhythm of cortisol in mothers of individuals with ASD differed from the comparison group. To do so, we conducted a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) with four measures of cortisol levels (using log transformed scores, averaged across the four days) as the dependent variables, and group (the AAA group versus the MIDUS comparison group) as the factor. Follow-up univariate ANOVAS were used as post-hoc assessments of between-group differences at each time point.

The overall multivariate test was significant [F (4, 249) = 11.197, p < .001], suggesting that the two groups differed significantly in cortisol levels. Follow up t-tests revealed that mothers of individuals with ASD had significantly lower levels at first three time points (p < .001), but the two groups did not differ at bedtime (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Note that, to aid in interpretability, Figure 1 is based on raw scores.

Table 2.

Cortisol Levels (Log) at Each Collection Time

| Cortisol Variables | AAA vs Comparison | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awakening*** | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

170 86 |

2.69 2.39 |

.44 .39 |

| 30 minutes after awakening*** | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

171 85 |

3.03 2.71 |

.54 .42 |

| Before lunch*** | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

170 86 |

1.96 1.67 |

.42 .45 |

| At bedtime*** | 0 Comparison 1 AAA |

170 85 |

1.18 1.06 |

.53 .57 |

p <.001

Next, we used multilevel models to analyze log transformed cortisol levels at these four time points in the AAA and MIDUS samples, controlling for maternal age, whether the mother was taking prescription medications during the Diary Study, and for the collection time of each of the four saliva samples, all of which are factors that can affect cortisol levels. As shown in Table 3, the significant coefficient for group (AAA vs. comparison) indicated that even with these factors controlled, mothers of individuals with ASD had significantly lower cortisol at all four time points than mothers in the comparison group, providing support for our first hypothesis.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models of Predicting Cortisol Level (Log) at Each Collection Time

| Awakening | 30 min. after awakening | Before lunch | At bedtime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||||

| Intercept | 2.742 (0.040)*** | 3.093 (0.046)*** | 1.958 (0.044)*** | 1.187 (0.053)*** |

| Person-level predictors | ||||

| Group (AAA = 1) | −0.276 (0.056)*** | −0.310 (0.063)*** | −0.338 (0.057)*** | −0.181 (0.077)* |

| Mother’s age | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.007 (0.003)* | 0.010 (0.003)** |

| Taking medication (yes = 1) | −0.091 (0.053)+ | −0.067 (0.060) | −0.051 (0.093) | −0.006 (0.068) |

| Day-level predictor | ||||

| Collection time | −0.056 (0.024)* | −0.115 (0.020)*** | −0.028 (0.019) | 0.145 (0.030)*** |

| Random Effects (Variance Component) | ||||

| Between-Person: Intercept | 0.139 (d.f. = 221) X2 = 921.8*** |

0.188 (d.f. = 221) X2 = 1126.7*** |

0.128 (d.f. = 222) X2 = 847.9*** |

0.235 (d.f. = 224) X2 = 994.8*** |

| Between-Person: Collection time | 0.025 (d.f. = 224) X2 = 282.1** |

0.011 (d.f. = 224) X2 = 268.7* |

0.012 (d.f. = 225) X2 = 275.8* |

0.026 (d.f. = 227) X2 = 253.2 |

| Within-Person | 0.161 | 0.146 | 0.151 | 0.246 |

p < .10

p <.05

p < .01

p < .001

History of Behavior Problems

Next, within the AAA group, we examined whether mothers’ cortisol level differed by their son or daughter’s history of behavior problems as measured by four assessments of behavior problems across the 4.5 years between Time 1 and Time 4. The average history of behavior problems score for the current sample was 112.9 (SD = 9.1), ranging from 99 to 136.

Mothers whose son or daughter with ASD had clinically-significant levels of behavior problems (scores greater than 110; n = 44) were compared to mothers of individuals with below-clinical levels of behavior problems (scores less than or equal to 110; n = 42). For this comparison, we used analysis of covariance, run separately for each point of cortisol collection; covariates included maternal education, age, marital status, number of children, whether the mother was taking medications during the diary study, and wake-up collection time. We also controlled for whether the son or daughter with ASD also had intellectual disability and child gender. Although mothers whose son or daughter had a history of clinically-significant behavior problems had lower cortisol levels, the differences were not significant at any time point, and thus our second hypothesis was not supported.

Daily Behavior Problems

Table 4 presents descriptive data on daily behavior problems manifested during the 8-day Diary Study. As shown in Table 4, repetitive behaviors were the most frequently reported behavior problem (on 52% of days). Fully 80% of mothers reported repetitive behavior on at least one day of the study period. Withdrawn behavior occurred on 28% of days, with 58% of mothers reporting withdrawn behavior on at least one day of the 8-day study period. Mothers reported uncooperative behavior and socially offensive behavior on 25% of days. Additionally, 62% of mothers reported uncooperative behavior and 46% of mothers reported socially offensive behavior on at least one day of the 8-day study period.

Table 4.

Proportion of Days with Behavior Problems.

| Mean | SD | Behavior Problem on at Least One Day | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repetitive Behavior | .52 | .39 | 80% of children |

| Withdrawn Behavior | .28 | .34 | 58% of children |

| Uncooperative Behavior | .25 | .30 | 62% of children |

| Socially Offensive Behavior | .25 | .33 | 46% of children |

| Hurtful to Property | .07 | .19 | 20% of children |

| Hurtful to Others | .07 | .19 | 18% of children |

| Self-Injurious Behavior | .06 | .14 | 24% of children |

| Any Problem Behavior | .65 | .35 | 94% of children |

Destructive behaviors were less frequent: mothers reported behaviors that were hurtful to property and hurtful to others on 7% of days. However, 20% and 18% of mothers reported at least one day during the 8-day study period in which their son or daughter exhibited behavior that was hurtful to property or hurtful to others, respectively. Self-injurious behaviors were reported on 6% of days, with 24% of mothers reporting that their son or daughter displayed self-injurious behavior at some point during the 8-day study.

We also calculated the number of days mothers experienced at least one behavior problem manifested by their son or daughter with ASD. As shown in the bottom row of Table 4, on average, mothers reported that their son or daughter exhibited at least one behavior problem on 65% of days. Only 6% of mothers did not report any behavior problems during the Daily Diary Study. Not shown in Table 4 is the finding that 35% of mothers reported at least one behavior problem on all 8 days.

Behavior Problems and the Diurnal Rhythm of Cortisol

Table 5 presents multilevel models in which the effects of both history and daily behavior problems on the cortisol awakening response were evaluated. Specifically, the effects of behavior problems from Time 1 through Time 4, the effects of the number of daily behavior problems the day before cortisol collection, and the interaction between the history and daily measure of behavior problems were used to predict the morning rise of cortisol (i.e., the cortisol awakening response).

Table 5.

Multilevel Models of Daily Behavior Problems and History of Behavior Problems Predicting the Morning Rise of Cortisol.a

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effect | 4.779 (2.413)+ | 4.396 (2.395)+ | 4.400 (2.394)+ |

| Intercept | |||

| Person-level predictors | |||

| Education | 0.656 (1.187) | 0.610 (1.187) | 0.613 (1.187) |

| Age | 0.037 (0.066) | 0.044 (0.067) | 0.045 (0.067) |

| Marital status (married = 1) | 0.308 (2.046) | 0.432 (2.042) | 0.428 (2.044) |

| Number of children | 0.437 (0.710) | 0.416 (0.710) | 0.417 (0.711) |

| Taking medication (yes = 1) | −0.006 (1.452) | −0.054 (1.455) | −0.053 (1.455) |

| Child has ID (yes = 1) | 1.279 (1.517) | 1.426 (1.516) | 1.413 (1.515) |

| Child’s gender (son = 1) | −0.663 (1.770) | −0.283 (1.769) | −0.281 (1.769) |

| History of BP | −0.020 (0.085) | −0.022 (0.085) | −0.022 (0.085) |

| Day-level predictors | |||

| Awakening collection time | −1.257 (0.450)** | −1.417 (0.481)** | −1.368 (0.452)** |

| Daily BP-previous day | -- | 0.617 (0.647) | 1.521 (0.715)* |

| Cross-level Interaction Effects | |||

| Daily BP x History of BP | -- | -- | −0.201 (0.067)** |

| Random Effect (Variance Component) | |||

| Between-Person Intercept (Level 2) | 31.87 (d.f. = 75) X2 = 204.6*** |

30.98 (d.f. = 74) X2 = 192.4*** |

31.58 (d.f. = 74) X2 = 198.7*** |

| Within-Person (Level 1) | 62.54 | 64.13 | 62.11 |

p < .10

p <.05

p < .01

p < .001

Morning rise of cortisol is the difference between raw cortisol levels at 30 minutes after awakening and at awakening.

As shown in Table 5, in Model 1, the history of behavior problems did not predict the morning rise of cortisol (consistent with the MANOVA results described earlier). Model 2 portrays the effects of the daily measure of behavior problems (i.e., the number of behavior problems the day before), which also was not a significant predictor of the morning rise, thus not supportive of our third hypothesis.

However, the interaction between the history and daily behavior problem measures was a significant predictor of the morning cortisol rise (see Model 3). This interaction effect is graphed in Figure 2. (Raw scores are graphed to aid in interpretability.) The significant interaction effect indicates that, as hypothesized, mothers whose son or daughter had a history of clinically-significant levels of behavior problems had a less pronounced morning rise of cortisol the morning after a day when the child had more behavior problems, as compared with mothers whose son or daughter had a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems. In contrast, on days when the son or daughter with ASD manifested fewer behavior problems, there was much less of a difference in the mother’s awakening response based on her son or daughter’s history of behavior problems. Thus, a history of clinically-significant levels of behavior problems reduces the mother’s response associated with the “bad prior day” effect (yielding an attenuated reaction after rousing). In contrast, mothers of adolescents or adults who had a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems showed a heightened response to the prior day’s events, which is a more typical cortisol rise at awakening following stress.

Discussion

As a group, mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD evidenced a profile of HPA hypoactivity as compared with normative patterns manifested by mothers whose similarly-aged children do not have disabilities. This cortisol profile may initially seem counterintuitive given the endocrine response to acute stressors, but it is similar to findings on other groups experiencing chronic stress, including parents of children with cancer, combat soldiers, Holocaust survivors, and individuals suffering from PTSD (Heim et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2002; Yehuda, Boisoneau et al., 1995; Yehuda, Kahana, et al., 1995). Past research on mothers of individuals with ASD has documented their high level of psychological stress (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Seltzer, Krauss, Orsmond, & Vestal, 2000). The present study extends those findings by demonstrating that these mothers also present with the physiological profile characteristic of individuals experiencing chronic stress. The possible adaptive benefits of this down-regulation of hormone activity have been debated, but it may have some undesirable consequences, such as contributing to fatigue and attentional problems. Indeed, a previous study of the present sample suggested elevated levels of daily fatigue in these mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (Smith et al., 2009).

Furthermore, the present study provides evidence to link the subjective experience of stress and cortisol levels over time. The longitudinal and daily designs were particularly helpful in sorting out the temporal order and direction of effects. The history of behavior problems in adolescents and adults with ASD was assessed four times over a 4.5 year period, with a several-year gap between the last measure and the Daily Diary Study when cortisol was assessed. In addition, the measure of daily behavior problems was obtained the day before the cortisol awakening response was measured.

Importantly, the findings showed the benefits of considering the influence of both types of stress on cortisol level. Neither the history nor the daily measure of behavior problems predicted cortisol level independently. Rather, it was the interaction between the two indicators of stress that significantly predicted a mother’s daily cortisol level. The global pattern of behavior problems experienced by mothers over a multi-year period established the context in which daily behavior problems had their effects. Specifically, for mothers whose son or daughter had a history of below-clinical levels of behavior problems, a day when their child manifested multiple behavior problems was experienced as aberrant, and the mother reacted on the following morning with a larger and more abrupt rise in cortisol. In contrast, mothers whose son or daughter historically had clinically-significant levels of behavior problems experienced a “bad day” yesterday (i.e., a day when their child had multiple behavior problems) as consistent with the past, and they showed a blunted cortisol response. Thus, it is when a mother’s individual history of stress is taken into account that her response to daily stress can best be interpreted.

The descriptive data provided by the present study reveal an alarmingly high level of behavior problems manifested by adolescents and adults with ASD. During the eight-day diary study, virtually all (94%) mothers experienced at least one episode of child behavior problems, and one-third (35%) of the mothers experienced behavior problems on all eight days. Of particular concern, 24% of the mothers indicated that their adolescent or adult child displayed some type of self-injurious behavior on at least one day of the diary study. In addition to daily exposure, the average behavior problems score for this sample was in the clinically significant range over the 4.5 year study period, indicating both a high history of behavior problems measured globally and a high level of current behavior problems measured daily. Together this high exposure, which likely extended over the child’s entire life, helps explain lower cortisol levels in the mother. This is the “biological signature” that has been associated with the feeling of job burnout in high stress occupations as well as the arousal, depression, and anxiety found in individuals with PTSD after traumatic events (Fries et al., 2005; Sonnenschein et al., 2007). In this regard, it would be important in future studies to more specifically and acutely examine the mother’s immediate response to her son or daughter’s problematic behavior, because people who have PTSD often are highly sensitized to arousing stimuli associated with the trauma experience in spite of manifesting an attenuated daily cortisol rhythm. It is this combination of arousal, along with the intrusive thoughts, numbing, emotional distancing, fatigue, and attentional problems, that contributes to their psychological distress and abnormal physiological states associated with chronic stress (Fries, Hess, Hellhammer, & Hellhammer, 2005).

An alternative explanation for the between-group differences that we found when contrasting mothers of individuals with ASD and the mothers in the comparison group is that there may be a pre-existing tendency for lower cortisol levels in mothers who have a child with ASD. In other words, the hypoactivation of HPA may be the result of a pre-existing status rather than reflective of the reactive effects of the parenting a child with autism. Recent studies have reported that children with ASD also manifest lower cortisol levels (Brosnan, Turner-Cobb, Munro-Naan, & Jessop, 2009; Corbett, Schupp, Levine, & Mendoza, 2009). Autism is believed to be a complex genetic disorder, which would suggest that some close relatives may share milder versions of characteristics with those who have the full disorder, including potentially a tendency toward hypoactivation of cortisol. Future research should examine cortisol levels in mothers of children whose developmental disabilities are known not to be inherited (i.e., in sporadic genetic conditions) in order to better separate the influence of difficult parenting from biological propensity to downregulate the HPA axis. Similar issues have been raised with respect to the risk factors for developing PTSD on the basis of twin studies that suggested that a smaller hippocampal volume might contribute to vulnerability (Gilbertson et al., 2007).

There are several other important questions that emerge from this research that should be pursued in future studies. It would be valuable to assess cortisol patterns in mothers of young children with ASD who have had a shorter period of stress exposure than the mothers in the present sample. It has been suggested that hypocortisolism follows prolonged hyperactivity of the HPA axis (Fries et al., 2005). Thus, it is possible that the cortisol profile in mothers of young children with ASD might be one of hyperactivation, reflecting reaction to pressures of the newly-challenging parenting situation. Examination of the pattern of cortisol in young mothers is particularly important because studies in the general population suggest a decline in HPA resiliency associated with age (Seeman & Robbins, 2006).

It will also be important to examine prospectively if cortisol dysregulation is associated with an increased vulnerability to hormone-related health problems in mothers of individuals with ASD, as might be expected based on past research on other groups experiencing chronic stress (Heim et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2002). Alternatively, it is possible that hypoactivation is a protective response that reduces the individual’s risk of health problems, as was suggested by Fries et al. (2005). The longitudinal design of the present study, which is ongoing, will make these determinations possible in the future, with data on maternal health problems collected prospectively. Finally, it would be valuable to examine those factors that might increase vulnerability to and/or that buffer parents against these types of familial and life stressors and to consider the types of interventions, including psychoeducation interventions and cognitive behavior therapies, which could ameliorate the cortisol dysregulation. As mothers of individuals with ASD have increased risks of psychiatric comorbidity (Piven & Palmer, 1999), this is a particularly important set of investigations to carry out.

The present research had a number of methodological limitations and thus the results warrant cautious interpretation and replication in future studies. The mothers in the AAA study were primarily Caucasian, all volunteered to participate, and all those who were included in the present analysis co-resided with their adolescent or adult child with ASD. Thus, the extent to which they were representative of the diverse population of families with a member with ASD is unknown. In addition, it is possible that the higher proportion of sons in the autism sample than the comparison sample contributed to the between-group differences. We explored this possibility by restricting the samples to son-only families to determine if any of the results changed. This approach did not result in any change in the findings. Juxtaposed against these limitations are the unique strengths of this research, including the longitudinal study period extending over an average of seven years, a nationally representative normative comparison group, and a previously validated protocol for daily cortisol collection (Almeida, McGonagle, & King, under review).

In conclusion, the present study indicated that mothers experience both acute and chronic stress associated with the behavior problems of their adolescent or adult children and that the degree of their cortisol dysregulation is linked with their child’s behavioral profile. Interventions that reduce behavior problems would enhance the health and quality of life of both mothers and the individuals with ASD, and thus should be a high priority for service provision. Although behavior problems are implicated in this study, they are linked in complex ways to autism symptoms and cognitive functioning, and thus are just one aspect of a much broader challenge.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging to support longitudinal research on families of adolescents and adults with autism (R01 AG08768, M. Seltzer, PI) and to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS (Midlife in the US) investigation (P01 AG020166, C. Ryff, PI, and R01AG019239, D. Almeida, PI). The original MIDUS study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. Support was also obtained from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for P30 HD03352 to the Waisman Center at the UW-Madison.

References

- Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Krauss MW, Osmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;109:237–254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Hawkley LC, Kudielka BM, Cacioppo JT. Day-to-day dynamics of experience-cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:17058–17063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, McGonagle KA, King HA. Stressor exposure and salivary cortisol as a marker of affective functioning. (under review) [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, McIntyre LL. Syndrome specificity and behavior disorders in young adults with intellectual disability: Cultural differences in family impact. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:184–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. The MIDUS National Survey: An overview. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan M, Turner-Cobb J, Munro-Naan Z, Jessop D. Absence of a normal Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) in adolescent males with Asperger Syndrome (AS) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock RW, Weatherman RF, Hill BK. Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle W, Baum A. Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:414–420. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221236.37158.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Schupp CW, Levine S, Mendoza S. Comparing cortisol, stress, and stress sensitivity in children with autism. Autism Research. 2009;2:39–49. doi: 10.1002/aur.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixson WJ, Yuen KK. Trimming and winsorization: A review. Statistical Papers. 1974;15:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhower AS, Baker BL, Blacher J. Preschool children with intellectual disability: Syndrome specificity, behavior problems, and maternal well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:657–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller NH, Netterstrom B, Hansen AM. Psychosocial factors at home and at work and levels of salivary cortisol. Biological Psychology. 2006;73:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englert RC, Dauser D, Gilchrist A, Samociuk HA, Singh RJ, Kesner JS, Cuthbert CD, Zarfos K, Gregorio DI, Stevens RG. Marital status and variability in cortisol excretion in postmenopausal women. Biological Psychology. 2008;77:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinn MW. Evolution and ontogeny of stress response to social challenges in the human child. Developmental Review. 2006;26:138–174. [Google Scholar]

- Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson MW, Williston SK, Paulus LA, Lasko NB, Gurvits TV, Shenton ME, et al. Configural cue performance in identical twins discordant for posttraumatic stress disorder: Theoretical implications for the role of hippocampal function. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald TL, Mroczek DK, Ryff CD, Singer BH. Diverse pathways to positive and negative affect in adulthood and later life: An integrative approach using recursive partitioning. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:330–343. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MT, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of the expected daytime rhythm: Potential indices of risk in human development. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:515–538. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, Ward NJ, degli Espinosa F, Brown T, Remington B. Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:635–644. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring S, Gray K, Taffe J, Tonge B, Sweeney D, Einfeld S. Behavior and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: Associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:874–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan DM, Licinio J, Veldhuis JD. A feedback-controlled ensemble model of the stress-responsive hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2001;98:4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051624198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychoneuroendocrine research: Recent developments and applications. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994;19:313–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61:154–162. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: Impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:83–98. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounds JJ, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Shattuck P. Transition and change in adolescents and young adults with autism: Longitudinal effects on maternal well-being. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:401–417. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[401:TACIAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Barefoot JC, Blumenthal JA, Siegler IC, Williams RB. Stress in employed women: Impact of marital status and children at home on neurohormone output and home strain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:352–359. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: A glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychology. 2002;21:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Palmer P. Psychiatric disorder and the broad autism phenotype: Evidence from a family study of multiple-incidence autism families. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:557–563. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Method. 2. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised WPS Edition. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. ADI-R. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Robbins RJ. Aging and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to challenge in humans. Endocrine Reviews. 2006;15:223–261. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquire. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Almeida DM, Greenberg JS, Savla J, Stawski RS, Hong J, Taylor JL. Psychological and biological markers of daily lives of midlife parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:1–15. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Orsmond GI, Vestal C. Families of adolescents and adults with autism: Uncharted territory. In: Glidden LM, editor. International Review of Research on Mental Retardation. Vol. 23. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Shattuck PT, Orsmond G, Swe A, Lord C. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:565–581. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005995.02453.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Orsmond GI, Bolt D, Kring S, et al. Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;13:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LE, Hong J, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Almeida DM, Bishop S. Daily experiences among mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD. Submitted to Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0844-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein M, Mommersteeg PMC, Houtveen JH, Sorbi MJ, Schaufeli WG, van Dooren LJP. Exhaustion and endocrine functioning in clinical burnout: An in-depth study using the experience sampling method. Biological Psychology. 2007;75:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer H. Robust statistics: A survey and some prescriptions. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1976;1:285–312. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Boisoneau D, Lowy MT, Giller EL. Dose-response changes in plasma cortisol and lymphocyte glucocorticoid receptors following dexamethasone administration in combat veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:583–593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950190065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Brynes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Giller EL. Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:982–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]