Abstract

Adenosine can show anti-inflammatory as well as pro-inflammatory activities. The contribution of the specific adenosine receptor subtypes in various cells, tissues and organs is complex. In this study, we examined the effect of the adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 and the A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 on acute inflammation induced experimentally by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) on rat ileum/jejunum preparations. Pre-incubation of the ileum/jejunum segments with TNBS for 30 min resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of acetylcholine (ACh)-induced contractions. Pharmacological activation of the A2AR with CGS 21680 (0.1–10 µM) pre-incubated simultaneously with TNBS (10 mM) prevented concentration-dependently the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contractions. Stimulation of A2BR with the selective agonist BAY 60-6583 (10 µM) did neither result in an increase nor in a further decrease of ACh-induced contractions compared to the TNBS-induced inhibition. The simultaneous pre-incubation of the ileum/jejunum segments with TNBS (10 mM) and the selective A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 (100 µM) inhibited the contraction-decreasing effect of TNBS. The effects of the A2AR agonist and the A2BR antagonist were in the same range as the effect induced by 1 µM methotrexate. The combination of the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 and the A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 at subthreshold concentrations of both agents found a significant amelioration of the TNBS-diminished contractility. Our results demonstrate that the activation of A2A receptors or the blockade of the A2B receptors can prevent the inflammation-induced disturbance of the ACh-induced contraction in TNBS pre-treated small intestinal preparations. The combination of both may be useful for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases.

Keywords: Adenosine receptors, A2AR agonist, A2BR antagonist, Inflammation, TNBS, Small intestine, Rat

Introduction

The purine nucleoside adenosine, which is involved in a variety of physiological functions, regulates a wide variety of immune and inflammatory responses and acts also as a modulator of gut function. Although it is present at low concentrations in the extracellular space, stressful conditions, such as inflammation and hypoxia, can markedly increase its extracellular level up to the micromolar range [13, 24, 27, 28, 44, 48]. Adenosine binds to four different types of G protein-coupled cell surface receptors referred to as A1R, A2AR, A2BR and A3R, each of which has a unique pharmacological profile, tissue distribution and signalling pathway [18]. There is growing evidence that adenosine plays an important role in the regulation of inflammation [6, 39]. All known adenosine receptors contribute to the modulation of inflammation, as demonstrated by many in vitro and in vivo pharmacologic studies [14, 33]. Depending on the tissue or cell type, adenosine may produce either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects [21]. Recent evidence suggests a prominent role of A2AR and A2BR in the pathophysiology of inflammation [39, 43].

Activation of A2AR produced various responses that can be characterised as anti-inflammatory effects [3]. A key molecular mechanism is a suppression of the nuclear factor-κB pathway activated by cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β as well as pathogen-derived Toll-like receptor agonists such as lipopolysaccharide [15, 29, 38, 40]. For example, the A2AR agonist ATL-146e has been demonstrated to suppress the inflammation in the intestinal mucosa. The leucocytes' infiltration and the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, interferon-γ and IL-4 were reduced [37]. Moreover, activation of A2AR on human monocytes and mice macrophages inhibits the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and TNF-α [15, 29].

A2BR is located on immune cells, and it is the predominate adenosine receptor expressed in the colonic epithelia cells [21]. A2BR is up-regulated in models of intestinal inflammatory diseases. The role of this receptor subtype has been largely unexplored because of the lack of specific A2BR agonists. As demonstrated indirectly by antagonists, the A2BR might be an important target to modulate inflammatory responses in the colon [20]. Furthermore, A2BR antagonists were potent in reducing inflammatory pain and inflammatory hyperalgesia [6] as well as in attenuating pulmonary inflammation [36, 45]. Contrary to this line of evidence, a recent report pointed out that A2BR knockout mice showed a phenotype with increased inflammatory responses [50]. BAY 60-6583 was the first specific non-adenosine-like A2BR agonist. The EC50 values of BAY 60-6583 are 3–10 nM for human A2BR and >10 μM for A1 and A2A receptors [9] and had no agonistic effect in the adenosine A3-Gα16 assay up to a concentration of 10 μM [26].

Two different agents were normally used to induce inflammatory processes in the small or large intestine, dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS). Disturbed intestinal activity induced in vitro by TNBS is characterised by an unspecific damage and the presence of inflammation, which is manifested by crypt and muscle destruction, mucosal damage and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the mucosal tissue [31, 47]. Additionally, TNBS increased the gene expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α but not of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. These effects are accompanied by lowering the phasic and tonic activity and suppression of acetylcholine (ACh)-induced contraction [32]. Contrary to TNBS, the DSS-induced colitis is independent of lymphocytes [8].

Therefore, in the current study, we investigate for the first time whether the combination of the selective A2A agonist CGS 21680 together with the selective A2B antagonist PSB-1115 can affect inflammation-induced disturbed intestinal contractile response in the TNBS in vitro model. To pursue this goal, we first assayed the effects of the selective ligands CGS 21680, BAY 60-6583, and PSB-1115 alone on the ACh-induced contractions in TNBS-damaged rat ileum/jejunum preparations and compared the effects with methotrexate, a standard medication of inflammatory bowel diseases. Additionally, we evaluated for the first time the combination of CGS 21680 and PSB-1115 both in ineffective concentrations.

Materials and methods

Materials

PSB-1115 (1-propyl-8-p-sulfophenulxanthine) was synthesised at the PharmaCenter Bonn, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry I, University Bonn, Germany, according to previously described procedures [19, 35, 49] and purified by preparative high-performance liquid chromatography to obtain a purity of >98%. The non-purinergic A2BR agonist BAY 60-6583 2-[6-amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]pyridin-2-ylsulfanyl]acetamide was a gift from Bayer HealthCare AG, Wuppertal, Germany. All other substances were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany.

ACh (1 M) was prepared as fresh 1:10 dilution in water from a 10 M aqueous stock solution. ACh was applied directly into the organ bath. Therefore, the final concentration was 1 mM. The adenosine receptor ligands were made up in stock solutions in dimethylsulfoxide, and methotrexate was dissolved in water. The final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration was 0.1%, which was without effect in any experiments. All stock solutions were stored as frozen aliquots at −20°C. Dilutions of these stock solutions and appropriate solvent controls were made. TNBS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany, in a 1 M stock solution in water, and stored at −20°C after aliquotation. Dilutions were freshly prepared before experiments.

The modified Krebs solution contained (mM): NaCl (130.5), KCl (4.86), MgCl2 (1.2), NaH2PO4 (1.97), Na2HPO4 (4.63), CaCl2 (2.4) and glucose (11.4). The pH value was adjusted to 7.3.

Animals

All procedures used throughout this study were conducted according to the German Guidelines for animal Care and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Animal Care Committee.

Adult male Wistar-rats (8–10 weeks old, 150–220 g body weight) were obtained from the Biomedical Centre, Medical Faculty University Leipzig, and were maintained at room temperature in a light (12 h light/12 h dark)-controlled environment with free access to food and water ad libitum. The rats were anaesthetized with ether and killed by decapitation. The abdomen was immediately opened, a small intestinal segment (ileum and distal part of the jejunum) of about 15 cm was rapidly removed and placed in a dish containing aerated modified Krebs solution at 37°C.

Induction of inflammation

Inflammation was induced as described previously [31]. In brief, an ileum/jejunum segment approximately 2.5 cm long was prepared and cleaned. A thread closed one end, and in the other end, a canula was installed through which TNBS (10 mM) or the control solution was applied. After application, the canula was removed, and the segment was closed by a thread. The preparation was suspended for 30 min in a 10 ml incubation chamber containing aerated modified Krebs solution. After incubation, the threads were removed, and the preparation was rinsed with modified Krebs solution. Sections of 1.5 cm in length were prepared for the experiments.

Drug application

ACh was applied directly into the organ bath. The A2AR and A2BR ligands, methotrexate or the control were instilled intraluminal 3 min before instillation of TNBS and were then incubated together with TNBS for 30 min. In some preliminary experiment, the A2AR agonist or the A2BR antagonist was applied directly into the organ bath 3 min before ACh application to test the direct effect or the ACh contraction.

Isometric tension recording

A thread was attached to each end of a segment, and then it was suspended in 20 ml organ bath containing oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) modified Krebs solution maintained at 37°C. One end of the preparation was anchored to a stationary hook on the bottom of the organ bath. The other end was connected to an isometric transducer (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg) for continuous recording of the isometric tension. The preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 40 min under a tension of 10 mN interrupted by a wash out before starting the experiment. ACh (1 mM) was applied at the beginning of each experiment to test the sensitivity of the preparation used. The concentration of 1 mM was used according to concentration-response curves recorded on intact ileo-jejunal segments in the range from 10 µM to 2.5 mM with an ED50 value of 750 µM [46]. The concentration of 1 mM induced reproducible contractions with amplitudes suitable to examine inhibitory effects of TNBS.

Statistics

A relative comparison of the ACh contraction between preparations instilled with solvent (control = 100%) and with TNBS or TNBS in combination with the receptor ligands was used to determine functional differences. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM of n experiments. Multiple comparisons with a control value were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by unpaired Student's t test. A probability level of 0.05 or less was considered to represent a statistically significant difference. The concentration-response curve was constructed using nonlinear regression. The IC50 was calculated with SigmaPlot.

Results

Effects of the A2AR agonist and the A2AR antagonist on the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contraction

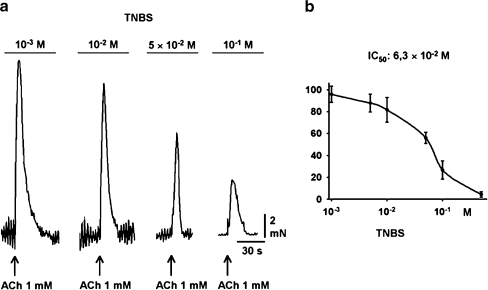

The ileo-jejunal segments were pre-incubated with TNBS for 30 min. During this time, an equilibrium inhibition of the ACh-induced contractions developed. TNBS (1 mM–1 M) resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of ACh-induced contractions (Fig. 1a) with an IC50 value of 63 mM calculated from the concentration-response curve (Fig. 1b). TNBS in a concentration of 100 mM reduced the ACh contraction to 35.2 ± 2.9% (n = 9). The moderate disturbance induced by 10 mM was used for further experiments.

Fig. 1.

Effects of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS; 1–100 mM) on the ACh-induced contraction in rat ileum/jejunum segments. a Representative original registrations. ACh was used in a concentration of 1 mM. b Concentration-response curve of the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh-induced contraction (1 mM). Each point represents n = 21 experiments

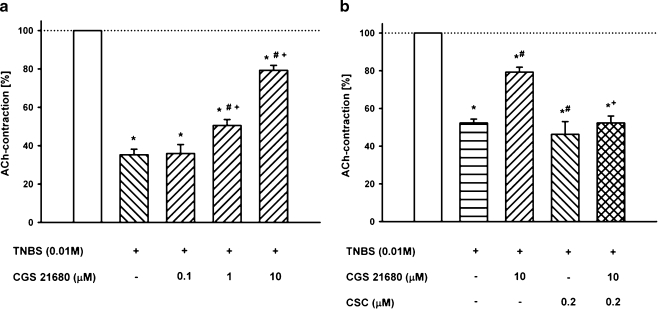

In a first series of experiments, the standard A2AR agonist CGS 21680 applied directly into the organ bath was tested on the ACh-induced contraction. CGS 21680 (10 µM) increased the ACh-induced contractions by 20 ± 7% compared to the control (P < 0.05, n = 5). The increase was prevented by the A2AR antagonist 1,3,7-trimethyl-8[3-chlorostyryl]xanthine (CSC, 0.2 µM; data not shown). Thereafter, CGS 21680 (0.1–10 µM) was pre-incubated simultaneously with TNBS (10 mM). It restored concentration-dependently the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contractions. Whereas CGS 21680 in a concentration of 0.1 µM was without significant effect compared to the TNBS-control, concentrations of 1 and 10 µM significantly affected the ACh-induced contraction respectively by 50.5 ± 3.14% and 79.3 ± 2.6% (n = 9, Fig. 2a). The A2AR antagonist CSC (0.2 µM) was without effect on the TNBS-reduced contractions (52.3 ± 2.6% vs. 46.3 ± 6.8%), but it antagonised the protective effect of CGS 21680 (10 µM; 79.3 ± 2.6% vs. 52.3 ± 3.7%; Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Effects of the A2AR ligands on the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced decrease of the ACh (1 mM) contractions. a Concentration-dependent effect of the selective A2AR agonist CGS 21680 on the TNBS-induced attenuation of the ACh (1 mM)-induced contractions. b Effects of TNBS, the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 (10 µM) and the A2AR antagonist CSC (0.2 µM) as well as the simultaneous pre-incubation on the ACh-induced contraction (1 mM) in rat ileum/jejunum segments. Means ± SEM of n = 9 experiments. Asterisk: p < 0.05 vs. control (open column); Number sign: p < 0.05 vs. previous column; Plus sign: p < 0.05 vs. CGS 21680

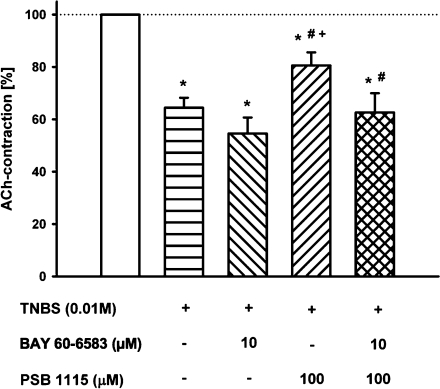

Effects of the A2BR agonist and A2BR antagonist on the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contraction

BAY 60-6583 (10 µM) applied directly into the organ bath reduced the ACh-induced contractions by 22.7 ± 6.4% n = 11, data not shown). In the same concentration (10 µM), BAY 60-6583 did not affect the TNBS-induced inhibition of ACh-induced contraction (54.6 ± 6.1% vs. 64.5 ± 3.8%, n = 12; Fig. 3). The simultaneous pre-incubation of the ileum/jejunum segments with TNBS (10 mM) and the selective A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 (100 µM), which was without effect on intact preparation, inhibited the contraction-decreasing effect of TNBS (80.6 ± 5.0%, n = 12). The combined pre-incubation of both the agonist BAY 60-6583 (10 µM) and the antagonist PSB-1115 (100 µM) together with TNBS (10 mM) did not significantly affect the TNBS-depended inhibition of ACh-induced contraction compared with TNBS alone (64.5 ± 3.8% vs. 62.5 ± 7.3%; n = 12; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of the A2BR agonist BAY 60-6583 and the A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 as well as the simultaneous pre-incubation with TNBS on the ACh (1 mM)-induced contractions. Means ± SEM of n = 12 experiments. Asterisk: p < 0.05 vs. control (open column); Number sign: p < 0.05 vs. previous column

The effect of PSB-1115 was concentration-dependent in the range of 1 to 100 µM. The inhibition of the ACh-induced contraction by TNBS (10 mM) in the presence of 1 µM PSB-1115 was not significantly changed (98.0 ± 6.6%), whereas the simultaneous pre-incubation of the ileum/jejunum segments with TNBS (10 mM) and PSB-1115 (10 and 100 µM) reduced the TNBS-induced decrease of the ACh-induced contractions significantly by 77.0 ± 10.7% and 29.5 ± 6.7%, respectively.

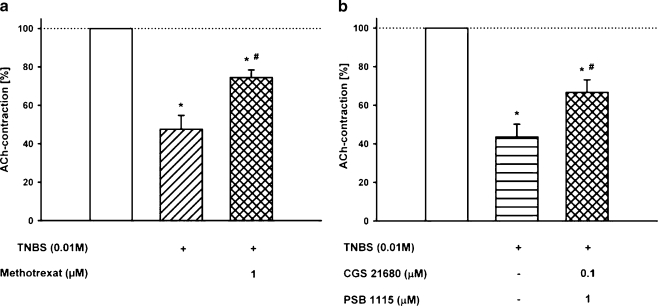

Effects of methotrexate on the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contraction

Methotrexate pre-incubated simultaneously with TNBS significantly counteracted the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contractions (Fig. 4a). The decrease of the ACh-induced contraction by TNBS (10 mM) was 52.4 ± 7.2%; after pre-incubation together with 1 µM methotrexate, the decrease was reduced to 25.5 ± 3.9% (n = 12). As can be seen from Fig. 4, the TNBS-preventing effect of methotrexate is comparable to the effect of the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 (10 µM, Fig. 2) or A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 (100 µM, Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Effect of the A2AR agonist and the A2BR antagonist as well as methotrexate on the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced decrease of the ACh (1 mM) contractions. a Effect of TNBS (10 mM) and the combined pre-incubation of TNBS and methotrexate (10 µM) on the ACh (1 mM) contraction. Means ± SEM of n = 12 experiments. Asterisk: p < 0.05 vs. control (open column); Number sign: p < 0.05 vs. previous column. b Effect of the combined pre-incubation of the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 and the A2BR antagonist PSB-1115 both in a concentration which was without effect alone and simultaneously with TNBS (10 mM) on the ACh (1 mM) contraction

Effect of the combination of CGS 21680 and PSB-1115 on the TNBS-induced inhibition of the ACh contraction

Based on the findings that the A2AR agonist and the A2BR antagonist counteracted the TNBS-induced disturbance of contractile responses, the effect of the combination of CGS 21680 and PSB-1115, both in a concentration without significant effect in the experiments before, was tested. Thus, the ileum/jejunum segments were pre-incubated with the combination of 0.1 µM CGS 21680 and 1 µM PSB-1115 together with TNBS (10 mM). Under this condition, the pre-incubation resulted in considerable inhibition of the TNBS-induced decrease of the ACh-induced contractions (66.6 ± 6.6% vs. 43.6 ± 3.8%; n = 11; Fig. 4b). The effect of the combination was in the same range as the action of each ligand applied separately in a high concentration or as induced by methotrexate.

Discussion

In this study, using an in vitro TNBS model, we demonstrate that the A2AR agonist and the A2BR antagonist or the combination of both effectively counteracted the development of TNBS-induced disturbance of the ACh contraction. The ligands exerted protective effects when treatment began simultaneously with the application of TNBS. Additionally, we have shown for the first time that a significant amelioration of the contractility disturbance by the combination of the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 and the A2B antagonist PSB-1115 was found at subthreshold concentrations of both agents. The protective effect was in range as the effect induced by 1 µM methotrexate, a concentration normally used in in vitro experiments [11].

These observations provide support to the view that activation of A2AR and the blockade of the A2BR could attenuate the inflammatory response and argue against an anti-inflammatory effect resulting from activation of A2BR as discussed by Yang et al. [50]. Therefore, our results confirm on ileo-jejunal segments results of in vivo experiments in which the blockade of adenosine A2B receptors ameliorates DSS-induced disturbance in mice colon [22]. We could exclude an involvement of A3 receptors. Meanwhile the receptor is expressed; neither the A3R agonist IB-MECA (10 µM) nor the A3R antagonist MRS 1220 (0.1 mM) showed an influence on the TNBS-induced damage in additional experiments.

Recent evidence indicates that adenosine can have a beneficial role as immunomodulator in tissues subjected to injurious stimuli, including inflammation mainly by activation of A2AR [14].

Several lines of evidence from experimental data, published recently, confirm this assumption for gastrointestinal inflammation. (1) Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction showed an increase in A2AR expression in gastric tissues isolated from TNBS-inflamed animals [2]. (2) Inhibition of adenosine deaminase attenuated inflammation in rat experimental colitis [3]. (3) Inosine, a naturally occurring purine formed by the enzymatic breakdown of adenosine, has been shown to exert powerful anti-inflammatory effects both in vivo and in vitro, reduces inflammation and improved survival in a murine model of colitis [30]. (4) Drugs used in the management of inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases, such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine and related compounds, exert their anti-inflammatory actions through a variety of mechanisms, which include their ability to promote the accumulation of adenosine in the inflamed tissue [7, 34].

In our study, CGS 21680 was used as selective A2AR agonist. This compound effectively reduces inflammatory TNF-α production in vivo [12, 16], whereas in A2AR knockout animals, CGS 21680 was no longer able to inhibit cytokine production [12]. Contrary to the TNBS model, CGS 21680 failed to ameliorate the DSS-induced acute colitis in mice [42]. One explanation of the differential effect of CGS 21680 could be the difference in the pathophysiology of the two models. The DSS-induced colitis is independent of lymphocytes [8], and the anti-inflammatory action of A2AR is targeted to these cell components [37].

Recently, it has been shown indirectly by blockade of A2BR that this receptor subtype plays a pro-inflammatory role in DSS-colitis [23]. Using the selective A2BR agonist BAY 60-6583, our results confirm this assumption. BAY 60-6583 was characterised in CHO cells expressing human adenosine receptors. The EC50 values were 3 nM for A2BR and >10,000 nM for A1R and A2AR [25]. Soluble 5′-nucleotidase or A2BR agonist treatment mimicked cardioprotection by ischemic preconditioning because it was associated with significant attenuation of myocardial infarct sizes after ischaemia [9].

Mice fed the highly specific inhibitor of the A2BR ATL-801 (N-[5-1(cyclopropyl-2,6-dioxo-3-propyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)-pyridin-2-yl]-N-ethyl-nicotinamide) along with DSS showed a significantly lower extent and severity of colitis than mice treated with DSS alone [22]. Likewise ATL-801, in our model PSB-1115 attenuates TNBS-induced changes in ileo-jejunal segments. PSB-1115 is a peripherally acting A2BR antagonist, which probably cannot penetrate the blood–brain barrier due to its polar sulfonate group [5]. Sulfonates such as PSB-1115 will also not penetrate cell membranes and, therefore, the observed effects have to be due to an extracellular mechanism and are believed to be mediated by a blockade of A2BR. The selectivity of PSB-1115 for the A2BR is confirmed by the determined Ki value of 53 nM for the A2BR in comparison to 24,000 nM for the A2AR [17] and by binding studies showing only low to negligible binding to 30 different receptors [1]. The anti-inflammatory effect obtained with a selective A2BR antagonist is in agreement with results from previous in vitro studies, which indicate a pro-inflammatory function of A2BR and anti-inflammatory actions of A2BR antagonists [4, 6].

It should be noted that the subthreshold combination of the A2AR agonist and the A2BR antagonist showed a comparable effect with methotrexate. This combination investigated for the first time may be important for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective properties of A2AR agonists have not yet been adequately tested in clinical trials because the A2AR has a widespread tissue and cell-type distribution, and therefore, activating this receptor might lead to unwanted side effects. The A2AR activation mediates inhibition of platelet aggregation, hypotension and a variety of effects within the central nervous system [10, 39, 41]. In this respect, considering the low concentration of the A2AR agonist and the inability of the A2BR antagonist to penetrate the cell membrane as well as the blood–brain barrier, the concept of the agonist/antagonist combination could overcome these therapy limiting side effects.

In conclusion, our results point out the concept that the selective activation of A2AR and the blockade of the A2BR would be potentially beneficial in the treatment of acute inflammatory processes in the gut.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Thomas Krahn, Bayer HealthCare AG, Wuppertal, Germany, for the supply of BAY 60-6583.

Conflict of interest The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Abo-Salem OM, Hayallah AM, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Filipek B, Zimmer A, Muller CE. Antinociceptive effects of novel A2B adenosine receptor antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(1):358–366. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.056036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonioli L, Fornai M, Colucci R, Ghisu N, Blandizzi C, Tacca M. A2a receptors mediate inhibitory effects of adenosine on colonic motility in the presence of experimental colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(2):117–122. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000198535.13822.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonioli L, Fornai M, Colucci R, Ghisu N, Settimo F, Natale G, et al. Inhibition of adenosine deaminase attenuates inflammation in experimental colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(2):435–442. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auchampach JA, Jin X, Wan TC, Caughey GH, Linden J. Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptor and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52(5):846–860. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgold J, Nikodijevic O, Jacobson KA. Penetration of adenosine antagonists into mouse brain as determined by ex vivo binding. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43(4):889–894. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90257-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilkei-Gorzo A, Abo-Salem OM, Hayallah AM, Michel K, Muller CE, Zimmer A. Adenosine receptor subtype-selective antagonists in inflammation and hyperalgesia. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;377(1):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronstein BN, Montesinos MC, Weissmann G. Salicylates and sulfasalazine, but not glucocorticoids, inhibit leukocyte accumulation by an adenosine-dependent mechanism that is independent of inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and p105 of NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(11):6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieleman LA, Ridwan BU, Tennyson GS, Beagley KW, Bucy RP, Elson CO. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis occurs in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(6):1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckle T, Krahn T, Grenz A, Kohler D, Mittelbronn M, Ledent C, et al. Cardioprotection by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and A2B adenosine receptors. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fozard JR, Ellis KM, Villela Dantas MF, Tigani B, Mazzoni L. Effects of CGS 21680, a selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist, on allergic airways inflammation in the rat 1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;438(3):183–188. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gocke AR, Cravens PD, Ben LH, Hussain RZ, Northrop SC, Racke MK, et al. T-bet regulates the fate of Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes in autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;178(3):1341–1348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez G, Sitkovsky MV. Differential requirement for A2a and A3 adenosine receptors for the protective effect of inosine in vivo. Blood. 2003;102(13):4472–4478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guieu R, Dussol B, Devaux C, Sampol J, Brunet P, Rochat H, et al. Interactions between cyclosporine A and adenosine in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 1998;53(1):200–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasko G, Kuhel DG, Chen JF, Schwarzschild MA, Deitch EA, Mabley JG, et al. Adenosine inhibits IL-12 and TNF-[alpha] production via adenosine A2a receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms. Faseb J. 2000;14(13):2065–2074. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0508com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasko G, Szabo C, Nemeth ZH, Kvetan V, Pastores SM, Vizi ES. Adenosine receptor agonists differentially regulate IL-10, TNF-alpha, and nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages and in endotoxemic mice. J Immunol. 1996;157(10):4634–4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayallah AM, Sandoval-Ramirez J, Reith U, Schobert U, Preiss B, Schumacher B, et al. 1, 8-disubstituted xanthine derivatives: synthesis of potent A(2B)-selective adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2002;45(7):1500–1510. doi: 10.1021/jm011049y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(3):247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirfel A, Schwabenländer F, Müller CE. Crystal structure of 1-propyl-8-(4-sulfophenyl)-7H-imidazo[4, 5-d]pyrimidin-2, 6(1H, 3H)-dione dihydrate, C14H14N4O5S x 2 H2O. Z Kristallographie - New Cryst Struct. 1997;3:447–448. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolachala V, Asamoah V, Wang L, Obertone TS, Ziegler TR, Merlin D, et al. TNF-alpha upregulates adenosine 2b (A2b) receptor expression and signaling in intestinal epithelial cells: a basis for A2bR overexpression in colitis 2281. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(22):2647–2657. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5328-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolachala VL, Bajaj R, Chalasani M, Sitaraman SV. Purinergic receptors in gastrointestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(2):G401–G410. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00454.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolachala V, Ruble B, Vijay-Kumar M, Wang L, Mwangi S, Figler H, Figler R, Srinivasan S, Gewirtz A, Linden J, Merlin D, Sitaraman S. Blockade of adenosine A2B receptors ameliorates murine colitis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155(1):127–137. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolachala VL, Vijay-Kumar M, Dalmasso G, Yang D, Linden J, Wang L, Gewirtz A, Ravid K, Merlin D, Sitaraman SV. A2B adenosine receptor gene deletion attenuates murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):861–870. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong T, Westerman KA, Faigle M, Eltzschig HK, Colgan SP. HIF-dependent induction of adenosine A2B receptor in hypoxia. Faseb J. 2006;20(13):2242–2250. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6419com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krahn T, Albrecht B, Rosentreter U, Cohen MV, Solenkova N, Downey JM. Adenosine A2B receptor agonist mimics posconditioning: characterization of a selective adenosine A2B receptor agonist in a rabbit infarct model. Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2:105. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuno A, Critz SD, Cui L, Solodushko V, Yang XM, Krahn T, Albrecht B, et al. Protein kinase C protects preconditioned rabbit hearts by increasing sensitivity of adenosine A2b-dependent signaling during early reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43(3):262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuno M, Seki N, Tsujimoto S, Nakanishi I, Kinoshita T, Nakamura K, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of non-nucleoside adenosine deaminase inhibitor FR234938. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;534(1–3):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuno R, Yoshida Y, Nitta A, Nabeshima T, Wang J, Sonobe Y, et al. The role of TNF-alpha and its receptors in the production of NGF and GDNF by astrocytes. Brain Res. 2006;1116(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Link AA, Kino T, Worth JA, McGuire JL, Crane ML, Chrousos GP, et al. Ligand-activation of the adenosine A2a receptors inhibits IL-12 production by human monocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164(1):436–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mabley JG, Pacher P, Liaudet L, Soriano FG, Hasko G, Marton A, et al. Inosine reduces inflammation and improves survival in a murine model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284(1):G138–G144. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00060.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael S, Kelber O, Hauschildt S, Spanel-Borowski K, Nieber K. Inhibition of inflammation-induced alterations in rat small intestine by the herbal preparations STW 5 and STW 6. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michael S, Kelber O, Vinson B, Nieber K. Herbal preparations STW 5 and STW 6 inhibit ileal inflammation-mediated motility disorders. Gut Supplement V. 2006;55:A1–A352. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montesinos M, Cronstein BN. Role of P1 receptors in inflammation. In: Abbrachio MP, Billiams M, editors. Handbook of experimental pharmacology, purinergic and pyrimidinergic cignalling II cardiovascular, respiratory, immune, metabolic and gastrointestial tract function, Volume 151/II. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montesinos MC, Desai A, Cronstein BN. Suppression of inflammation by low-dose methotrexate is mediated by adenosine A2A receptor but not A3 receptor activation in thioglycollate-induced peritonitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(2):R53. doi: 10.1186/ar1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller CE, Shi D, Manning M, Jr, Daly JW. Synthesis of paraxanthine analogs (1, 7-disubstituted xanthines) and other xanthines unsubstituted at the 3-position: structure-activity relationships at adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1993;36(22):3341–3349. doi: 10.1021/jm00074a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mustafa SJ, Nadeem A, Fan M, Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Zeng D. Effect of a specific and selective A(2B) adenosine receptor antagonist on adenosine agonist AMP and allergen-induced airway responsiveness and cellular influx in a mouse model of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320(3):1246–1251. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odashima M, Bamias G, Rivera-Nieves J, Linden J, Nast CC, Moskaluk CA, et al. Activation of A2A adenosine receptor attenuates intestinal inflammation in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):26–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odashima M, Otaka M, Jin M, Komatsu K, Wada I, Horikawa Y, et al. Attenuation of gastric mucosal inflammation induced by aspirin through activation of A2A adenosine receptor in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(4):568–573. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer TM, Trevethick MA. Suppression of inflammatory and immune responses by the A(2A) adenosine receptor: an introduction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S27–S34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sands WA, Martin AF, Strong EW, Palmer TM. Specific inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent inflammatory responses by cell type-specific mechanisms upon A2A adenosine receptor gene transfer. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(5):1147–1159. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarzschild MA, Agnati L, Fuxe K, Chen JF, Morelli M. Targeting adenosine A2A receptors in Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(11):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selmeczy Z, Csoka B, Pacher P, Vizi ES, Hasko G. The adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 fails to ameliorate the course of dextran sulphate-induced colitis in mice. Inflamm Res. 2007;56(5):204–209. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6150-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitkovsky M, Lukashev D. Regulation of immune cells by local-tissue oxygen tension: HIF1 alpha and adenosine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(9):712–721. doi: 10.1038/nri1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan GW. Adenosine A2A receptor agonists as anti-inflammatory agents 1. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4(11):1313–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun CX, Zhong H, Mohsenin A, Morschl E, Chunn JL, Molina JG, et al. Role of A2B adenosine receptor signalling in adenosine-dependent pulmonary inflammation and injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2173–2182. doi: 10.1172/JCI27303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warstat C (2004) Funktion von Adenosinrezeptoren am Ileum der Ratte und ihre Rolle bei Entzündungsprozessen. Dissertation, Universität Leipzig

- 47.Warstat C, Nieber K (2004) Influence of adenosine A1- and A2A-receptor ligands on experimentally induced inflammation in the rat ileum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 367(Suppl.1):R33

- 48.Wood JD. Enteric neuroimmunophysiology and pathophysiology. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):635–657. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan L, Muller CE. Preparation, properties, reactions, and adenosine receptor affinities of sulfophenylxanthine nitrophenyl esters: toward the development of sulfonic acid prodrugs with peroral bioavailability. J Med Chem. 2004;47(4):1031–1043. doi: 10.1021/jm0310030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang D, Zhang Y, Nguyen HG, Koupenova M, Chauhan AK, Makitalo M, et al. The A2B adenosine receptor protects against inflammation and excessive vascular adhesion. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1913–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI27933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]