Abstract

The P2X7 receptor exhibits significant allelic polymorphism in humans, with both loss and gain of function variants potentially impacting on a variety of infectious and inflammatory disorders. At least five loss-of-function polymorphisms (G150R, R307Q, T357S, E496A, and I568N) and two gain-of-function polymorphisms (H155Y and Q460R) have been identified and characterized to date. In this study, we used RT-PCR cloning to isolate and characterize P2X7 cDNA clones from human PBMCs and THP-1 cells. A previously unreported variant with substitutions of V80M and A166G was identified. When expressed in HEK293 cells, this variant exhibited heightened sensitivity to the P2X7 agonist (BzATP) relative to the most frequent allele, as shown by pore formation measured by fluorescent dye uptake into cells. Mutational analyses showed that A166G alteration was critical for the gain-of-function change, while V80M was not. Full-length variants with multiple previously identified nonsynonymous SNPs (H155Y, H270R, A348T, and E496A) were also identified. Distinct functional phenotypes of the P2X7 variants or mutants constructed with multiple polymorphisms were observed. Gain-of-function variations (A166G or H155Y) could not rescue the loss-of-function E496A polymorphism. Synergistic effects of the gain-of-function variations were also observed. We also identified the A348T alteration as a weak gain-of-function variant. Thus, these results identify the new gain-of-function variant A166G and demonstrate that multiple-gene polymorphisms contribute to functional phenotypes of the human P2X7 receptor. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that the C-terminal of the cysteine-rich domain 1 of P2X7 is critical for regulation of P2X7-mediated pore formation.

Keywords: P2X7 receptor, Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), Gain-of-function, Loss-of-function, Dye uptake, Pore formation, Adenosine triphosphate, Site-directed mutagenesis

Introduction

The purinergic P2X7 receptor, previously known as P2Z, is the seventh member of the P2X receptor family of ligand-gated ion channels activated by extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [1]. All of the P2X receptors contain two membrane-spanning domains, intracellular amino and carboxy termini, and an extracellular domain of approximately 280 amino acids containing the ligand-binding site and ten conserved cysteine residues that likely form intrachain disulfide bonds to give secondary structure to the receptor [2–5]. P2X7 receptors differ from other P2X receptor subtypes (P2X1–6) by an extended cytoplasmic carboxy-terminal tail (240 aa) which may be responsible for the unique ability of P2X7 to form large pores in the membrane after prolonged agonist stimulation [1]. The P2X7 receptor exhibits several unusual properties. Following brief activation by agonist, P2X7 forms a channel with strong selectivity for the divalent cations Ca2+ and Ba2+ over monovalent cations [6]. Continued stimulation by agonist results in the formation of a non-selective pore that allows permeation of inorganic and organic cationic molecules up to 900 Da, such as ethidium bromide, propidium iodide (PI), and quinolinium fluorescent dyes YO-PRO-1 [4, 7]. Recent studies suggest that the large pore may reflect coupling to a pannexin hemichannel [8]. This non-selective pore formation eventually leads to cell death.

P2X7 receptors are predominantly expressed on cells from the hematopoietic lineages, such as erythrocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, monocytes, and macrophages [9–18]. It has been reported recently that P2X7 receptors are expressed in central and spinal cord neurons [19–22]. Brain glial cells (microglia, astrocytes, and Muller cells), bone cells (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes), and epithelial and endothelial cells are also rich in P2X7 receptors [23–29]. Expression of P2X7 receptors has also been demonstrated in the enteric nervous system of the small intestine, kidney, urinary tract, uterus, and liver [30–33].

The localization of P2X7 on pro-inflammatory cells and its ability to modulate the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-1β has suggested a role for it in inflammatory diseases. P2X7 is rapidly up-regulated and activated after initial inflammatory stimuli [34–36]. It has been reported that the P2X7 receptor has a pivotal role in neuro-inflammatory and neuro-degenerative processes in neuro-degenerative diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s disease [37, 38]. The P2X7 receptor has been associated with polygenic inflammatory diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis [39–41]. Chronic inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity are completely abolished in P2X7 knockout mice [42]. P2X7-deficient mice also show reduced severity of arthritis in an anti-collagen antibody arthritis model [43]. More recently, Sharp et al. reported that P2X7 deficiency suppressed development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [44]. Therefore, P2X7 receptors are promising targets in treatment of inflammatory diseases and pain regulation [45–49].

P2X7 receptors are distinct from other P2X receptors in their ligand-binding properties. Their activation requires approximately 100-fold higher concentration of ATP than do other P2X receptors [4]. The ATP analog 2′,3′-O-(4-benzoyl-benzoyl) ATP (BzATP) is more potent and produces higher maximal responses [50]. P2X7 receptor activity is blocked by divalent cations and certain antagonists such as oxidized ATP, KN-62, and AZ11645373 that are relatively selective for the receptor [47, 51]. However, the pharmacological profile of these agonists and antagonists shows striking species differences among human, rat, mouse, and guinea pig orthologs [4, 50, 52].

The human P2X7 gene localizes to a 55-kb region of chromosome 12q34 which has 13 exons and encodes a 595-amino-acid protein [53]. The gene is highly polymorphic and more than 686 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been found recently (search SNP for P2RX7 [gene name], limits 12, Homo sapiens, from NCBI SNP database, http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/sites/entrez, access date October 30, 2008). However, the majority of these have not been validated at the population genetic level and their functional effects are unclear. Five loss-of-function nonsynonymous allelic SNPs in P2X7 have been described to date, of which three are located in the carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail (T357S, E496A, and I568N) and two are in the extracellular loop [54–58]. Cabrini et al. have characterized the first gain-of-function polymorphism identified (H155Y) [59]. Another putative gain-of-function polymorphism described recently, the Q460R substitution, appears to enhance pore activity of the P2X7 receptor [58]. Increasing evidence from genetic association studies have demonstrated that the polymorphisms of the P2X7 gene are implicated in various diseases such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, tuberculosis, bipolar affective disorders, and diabetes [60–67]. It has also been reported that the polymorphisms are related to clinical outcome in allogeneic stem cell transplantation and to fracture risk and the efficacy of hormone replacement therapy [28, 68].

In this study, we have isolated full-length P2X7 cDNA clones from multiple human donors and identified several distinct phenotypes of the receptor. A new variant with V80M and A166G substitutions, which confers a gain-of-function phenotype, is reported. Site-directed mutagenesis analyses showed that an A166G change in the first cysteine-rich domain of the P2X7 extracellular loop is critical for the function of P2X7 receptor. Other previously reported SNPs of the P2X7 receptor such as H155Y, H270R, A348T, and E496A have also been identified and shown to exhibit distinct functional phenotypes. These results demonstrate that multiple-gene polymorphisms contribute to the complex biology of the human P2X7 receptor.

Experimental procedures

Collection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from normal human peripheral blood buffy coats which were purchased from the Central Blood Bank of Pittsburgh, PA. Briefly, 10 ml of plasma-removed blood was diluted with 25 ml of DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+. The diluted blood was overlayed on 15 ml of Percoll and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 30 min, room temperature with the brake off. The buffy layer was carefully collected and washed two times with DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ at 1000 RPM at 4°C for 10 min. Finally, the cell pellet was suspended in IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine (100 mM), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). Aliquots of the PBMCs were frozen in liquid nitrogen until ready for use.

Cloning of cDNA encoding the human P2X7 receptor Total RNA was extracted and purified from human PBMCs and THP-1 cells using RNeasy Mini Kit and RNase-Free DNase Set, as recommended by the manufacturer (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA with oligo-dT16-18 primer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from 1 µg of the purified total RNA at 42°C for 60 min. A pair of the sequence-specific primers with Xho I sites were designed based on the published human P2X7 cDNA sequence to amplify the entire coding sequence of the human P2X7 subunit by PCR [53]. The primers were as follows: forward primer, 5AAATTTTCTCGAGGCTGTCACCATGCCGGCCTGCT-3′, reverse primer, 5′-GGTGCTCGAGTTCAGTAAGGACTCTTGAAGCCACT-3′. AmpliTaq® DNA polymerase was used for amplification as described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cycling reaction was modified to one cycle at 95°C for 2 min and 35 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 61.5°C for 1 min, 72°C for 3 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were separated in a 1% agarose gel containing 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) and purified with Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI). The purified PCR products were then cloned into the pGEM®-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The screened clones were identified by Xho I or other appropriate restriction enzymes. The resulting clones were finally sequenced and analyzed using DNAStar software.

Constructions of N-terminal duo-flag-tagged P2X7 cDNA constructs To monitor the levels of expression of different P2X7 variants, P2X7 constructs fused with double-flag epitopes at their N-terminals were generated by semi-nested PCR and cloned into p2CI vector derived from PCR2.1 by insertion of a cytomegalovirus promoter, PCR-amplified IRES-neomycin-resistant sequences from the pFB-Neo-LacZ vector, and poly(A) signal sequences from pcDNA3.1 [69]. Primers with sequences of the flag epitope were designed based on the corresponding sequences from the pCMV-Tag 1 vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The Expand High-Fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used for all the PCR reactions. The final PCR amplicons were cloned into the p2CI vector using the appropriate restriction enzymes and the Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

An overlapping PCR strategy and/or fragment swapping with appropriate restriction enzymes were used for mutageneses to create the P2X7 variants [70]. For overlapping PCR, the two hybrid primers were designed to contain the nucleotide substitution for site-directed mutagenesis of the P2X7 variants. The amplicons with the site-directed mutagenesis were subcloned into the corresponding regions of the P2X7 expression constructs using the appropriate restriction enzymes and Rapid DNA Ligation Kit. Detailed plasmid maps and sequences of primers are available upon request. All of the vectors and mutants were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection HEK293 cells (American Type Culture Collection number, CRL-1573) were grown at 37°C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). HEK293 cells were plated in six-well plates and transfected with flag-tagged P2X7 expression constructs using Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent, as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 2.5 μg of DNA, 2.5 μl of Plus™ reagent, and 6.25 μl of Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent in 500 μl of Opti-MEM® I Reduced Serum Medium were used per well. The cells were selected with 1,000 µg/ml G418 for 3–5 weeks to make stably transfected cell lines and maintained in 500 µg/ml G418.

Flow cytometry To monitor the expression of the flag-tagged P2X7 fusion proteins in the transfected HEK293 cells, permeable staining of intact transfected cells with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) was performed using standard FACS procedures. In brief, the transfected cells were harvested with trypsin–EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), collected by centrifugation, washed three times with FACS wash buffer (5% FBS and 0.5 mg/L sodium azide in PBS), and re-suspended and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at 4°C. The fixed cells were washed three times with permeabilization buffer (5% FBS, 5 g/L saponin, and 0.5 mg/L sodium azide in PBS) and incubated in the same buffer on ice at least for 15 min. The cells were re-suspended with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody and incubated on ice and protected from light for 30 min. The cells were then washed three times with buffer and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS before analysis with BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). A total of 2 × 104 cells/sample were acquired and analyzed by using FlowJo software (Version 7.2.4) Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Total expression of the P2X7 receptor was based on detection of FITC positive cells.

Dye uptake Pore formation was examined in stable HEK293 cell lines after transfection with the P2X7 cDNA variant constructs. Flow cytometry was used to determine the uptake of propidium iodide dye (PI, MW 668, absorption maximum, 535 nm and emission maximum, 617 nm) by these cells. Briefly, HEK293 cells expressing P2X7 receptor were dislodged using trypsin–EDTA and washed with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). Samples of stably transfected cells were subjected to for permeable staining and FACS analysis of expression levels of each P2X7 construct. About 2.5 × 105 cells in the media with specified concentrations of BzATP (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 30 min. Then the cells treated with BzATP were washed with PBS and re-suspended with PBS containing 5 µM PI before analysis with BD LSR II flow cytometer. A total of 1 × 104 cells/sample were acquired and analyzed using FlowJo software (Version 7.2.4). The percentage of dye-positive cells was calculated as a measure of pore formation in the HEK293 cells transfected with the various P2X7 constructs.

Western blotting Cell lysates from the stably transfected HEK293 cells were prepared with NP-40 lysis buffer (Boston BioProducts, Worcester, MA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Lysates (100 μg/sample) were loaded on 11% SDS-PAGE gels and separated under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane by iBlot gel transfer system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and probed with appropriate primary (rabbit polyclonal anti-P2X7 or mouse anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibodies) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies by using the SNAP i.d. system (Millipore, Billerica, MA), as recommended by the manufacturers. The membrane was incubated with Western Blotting Luminol Reagents (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and imaged with Kodak Image Station 4000MM (Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY).

Results

Cloning of the human P2X7 cDNA variant

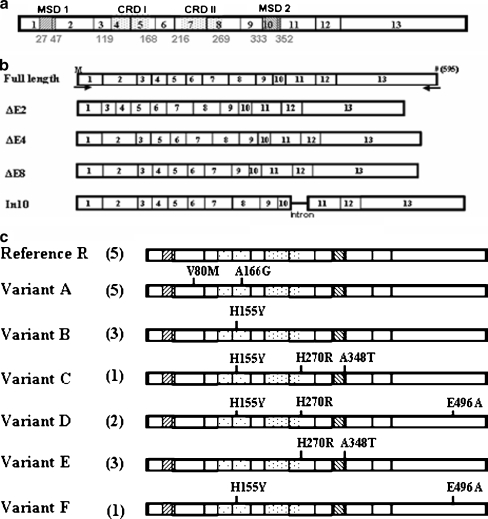

The human P2X7 gene contains 13 exons that encode a 595-amino-acid protein consisting of two membrane-spanning domains, intracellular amino and carboxyl termini, and a large extracellular loop (Fig. 1a) [53]. An RT-PCR cloning strategy was used to identify human P2X7 cDNA variants from human PBMCs and THP-1 cells, as described in detail in the “Experimental procedures” section. A pair of primers was designed to amplify the human P2X7 gene including the full-length open reading frame (ORF). Many shorter transcripts were identified during the cloning of the human P2X7 cDNAs that result from alternative splicing events, as summarized in Fig. 1b. It is unlikely that these transcript variants are artifacts resulting from the PCR cloning technique since more than two identical clones for each transcript were identified. In addition, the deleted sequences corresponded to exons and were located precisely at intron/exon boundaries.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the cloned P2X7 cDNA variants. a Schematic representation of the human P2X7 receptor. The P2X7 gene has 13 exons and encodes a 595-amino-acid protein with two predicted membrane-spanning domains (MSD), one extracellular domain including two cysteine-rich domains (CRD), and two intracellular domains. The corresponding exon regions are indicated as boxes with the corresponding numbers. Introns between exons are not shown. b Summary of the mis-spliced transcripts by alterative splicing found in this study. The exons removed by splicing are not shown and the remaining intron is indicated by a horizontal line. The positions of PCR primers used for RT-PCR cloning are indicated by arrowheads placed below the full length P2X7 transcript. Start and stop codons are indicated by the letter M and the number sign, respectively. c Summary of the full-length P2X7 cDNA variants found in this study. Amino acid changes are indicated in the full-length P2X7 cDNA variants based on a reference sequence of the receptor (GenBank accession number Y09561). The numbers of clones obtained for each of the variants are shown in parentheses

Splice variants lacking Exon 4 (DE4) or Exon 8 (DE8) or including the intron between Exons 10 and 11 (In10) were identified (Fig. 1b) and have been described before [71]. Transcripts lacking Exon 2 (DE2) were also identified (Fig. 1a). Some of the transcripts lacked Exon 4 in addition to other exons (data not shown). In all of these spliced transcripts, frame shifts occurred and new start and/or stop codons were created.

Twenty clones of the full-length P2X7 cDNAs were obtained from THP-1 cells and human PBMCs from six different donors, which demonstrated different pore activities induced by ATP (data not shown). Seven single-nucleotide variations of the human P2X7 were identified and classified into seven full-length cDNA variants based on a reference sequence of the receptor (GenBank accession number Y09561) [72], as summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1c. Five full-length P2X7 cDNAs were identical to the Reference variant. The seven single-base variations were revealed in at least three independently isolated full-length P2X7 cDNA clones, suggesting that these were not caused by errors during RT-PCR amplification. One of these alterations resulted in a synonymous amino acid substitution and six were nonsynonymous. Two nonsynonymous changes, V80M and A166G, have not been previously reported and were identified in five full-length P2X7 cDNA clones. This novel variant with dual substitutions we term Variant A. We also isolated full-length cDNA corresponding to previously reported gain-of-function SNP (H155Y) and loss-of-function SNP (E496A) [54, 59]. Additional cDNAs encoding nonsynonymous SNPs (H270R and A348T) were also obtained (Fig. 1c). These have been previously reported, but their effect on P2X7 function is unclear [56].

Table 1.

Single-nucleotide mutations (or SNPs) of the human P2X7 in the study

| SNM or SNPsa | AA changes | Clones | cDNA Variants | Derivation | refSNP ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 264 G → Ab | V80M | 5 | A | PBMC | This study | |

| 489 C → T | H155Y | 7 | B, C, D, F | PBMC, THP-1 | rs208294 | Cabrini, G., et al. [59] |

| 523 C → G | A166G | 5 | A | PBMC | This study | |

| 835A → G | H270R | 6 | C, D, E | PBMC, THP-1 | rs7958311 | Shemon, A. N., et al. [56] |

| 1068G → A | A348T | 4 | C, E | PBMC | rs1718119 | Shemon, A. N., et al. [56] |

| 1513 A → C | E496A | 3 | D, F | PBMC, THP-1 | rs3751143 | Gu,B. J., et al. [54] |

| 1772 G → A | - | 4 | C, E | PBMC | rs1621388 | Denlinger, L.C., et al. [58] |

aSNM and SNP represent single-nucleotide mutation and single-nucleotide polymorphism, respectively

bThe position numbers of the nucleotide mutations were based on a Reference sequence of the P2X7 receptor (GenBank accession number Y09561)

Expression and pore formation of the full-length P2X7 variants

In order to evaluate the phenotypes of the human P2X7 variants, all of the P2X7 cDNA clones were subcloned into the expression vector and tagged with double-flag epitopes at the N-terminals. Each of the P2X7 cDNA expression constructs was used individually to transfect HEK293 cells and to generate stable P2X7-expressing HEK293 cells in the presence of G418. The expression and function of the receptor variants were measured as described in detail in the “Experimental procedures” section. Attachment of a double-flag tag at the N-terminals facilitated monitoring of P2X7 expression quantitatively by flow cytometry using anti-flag antibodies. Flag-tagged P2X7 receptors were expressed at wild-type levels in HEK293 cells as measured by Western blotting (data not shown) and retained the ability to mediate pore formation as shown below.

The expression levels of various P2X7 variant proteins in the stable HEK293 cell lines were analyzed quantitatively by flow cytometry after labeling with a FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2a and b). All of the full-length P2X7 variant constructs were expressed in the stably transfected HEK293 cells. Figure 2b summarizes the expression levels of the respective P2X7 variant proteins in the HEK293 cells. In comparison with the Reference, the expression levels of the newly discovered Variant A were slightly decreased, albeit this is not statistically significant (p = 0.2896 or 0.2062 by student’s unpaired t test for positive cells or MFI analyses, respectively). The expression levels of Variants B, C, and E were slight increased with respect to Reference (although p > 0.1 by student’s unpaired t test for each variant versus Reference). However, Variants D and F showed significantly reduced expression in the stable HEK293 cell lines compared to Reference (p < 0.05 by student’s unpaired t test for each variant versus Reference). Both Variants D and F have the unique substitution E496A, a known loss-of-function SNP, compared to other variants (Fig. 1c and Table 1). Similar results were also confirmed by Western blotting analyses (Fig. 2c). It can be concluded that all of the full-length P2X7 constructs are expressed at similar levels in transfected 293T cell lines, except for Variants D and F with significantly reduced expression.

Fig. 2.

Expression of the full length P2X7 variants in stably transfected HEK293 cells. a Representative FACS data indicating respective expression levels of the full-length P2X7 variants dual flag-tagged at N-termini in stably transfected HEK293 cells, as detected by permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody. b Comparison of receptor protein expression in the stably transfected HEK293 cells with full-length P2X7 variants as measured by FACS analysis following permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody. The MFI value (mean fluorescence intensity) shown on the right refers to the value for all cells following live-cell gating based on forward scatter, while the percentage of positive cells were derived based on gating relative to the mock transfected cells, as shown in part A. The data shown are representative of more than six independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t tests (unpaired) compared to Reference (R) yielded significant levels of <0.05 (*) or <0.001 (***) as shown (c) Western blotting analysis of lysates from cells stably expressing the full-length P2X7 variants. Reducing SDS-PAGE was used to separate 100 µg protein/sample of protein prior to Western blotting

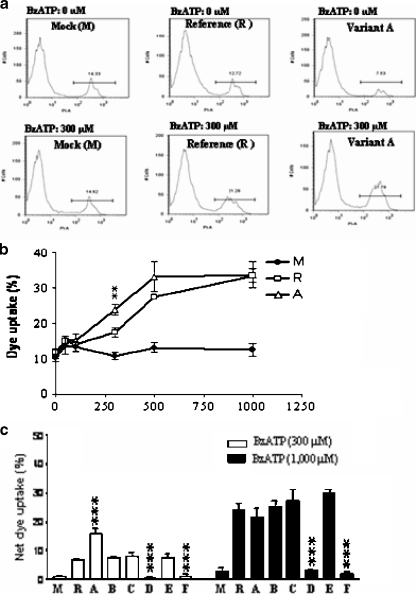

We next evaluated the ability of the variants to mediate pore formation in HEK293 transfectants in response to BzATP by measuring dye uptake (Fig. 3). Variant A showed higher activity than the Reference at several concentrations of BzATP, as seen in Fig. 3b. Variant A was more sensitive to lower doses of BzATP (300 µM and 500 µM) than the Reference. However, at the highest concentration of the BzATP (1,000 µM), no differences were observed. All seven P2X7 variants were next analyzed for responsiveness to BzATP (Fig. 3c). Clear distinctions in responsiveness to BzATP were observed in the different P2X7 variants (p = 0.0001 by analysis of variance for data derived from inductions of both 300 µM BzATP and 1,000 µM BzATP). Variant B and two other variants with multiple substitutions (C and E) were very similar in response to the Reference (Figs. 1c and 3c, and Table 1). However, Variants D and F showed little dye uptake in response to even the highest concentration of BzATP (1,000 µM). Taken together, these results clearly indicate that Variant A with two single-base alterations, 264 G → A (V80M) and 523 C → G (A166G), had increased sensitivity for pore formation induced by an agonist (BzATP) of the P2X7 receptor. Other P2X7 variants with substitutions at multiple positions also showed distinct pore forming properties.

Fig. 3.

PI dye uptake by HEK293 cells stably transfected with full-length P2X7 variants. a Representative FACS data indicating respective PI uptake by HEK293 cells stably transfected with each of the full length P2X7 variants induced by 300 µM BzATP. The cell population was gated for PI positivity. b Titration of BzATP inducing dye uptake by HEK293 cells stably transfected with Reference and Variant A. The percentage of PI uptake by the population was analyzed. The data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments. c PI dye uptake by the HEK293 cells stably transfected with each of the full-length P2X7 variants induced by 300 µM or 1,000 µM BzATP. Net dye uptake indicates the percentage dye uptake induced by BzATP with control (no BzATP treatment) subtracted. The data shown are representative of more than six independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t tests (unpaired) compared to Reference (R) yielded significance levels of <0.01(**) or <0.001 (***) as shown in b and c

Characterization of P2X7 mutants with single nonsynonymous base substitutions

In this study, only one full-length P2X7 cDNA variant (Variant B) with a known gain-of-function SNP (H155Y) was obtained compared to Reference (Fig. 1c) [59]. However, no significant increases of expression and pore formation of this variant were observed (Figs. 2b and 3c). In order to characterize other single-base substitutions individually in terms of expression and function of P2X7, five P2X7 mutants with one single-base mutation were constructed based on the cDNA backbone of Reference (Fig. 4a), as described in detail in the “Experimental procedures” section. Using similar techniques as described above, the expression levels of the single-base-substituted P2X7 mutants were also measured by flow cytometry analysis. As summarized in Fig. 4b, four of the mutated constructs were expressed in the stably transfected HEK293 cell lines at levels similar to the Reference construct. In contrast, the E496A mutant showed lower levels of expression than the Reference construct. This substitution was present in Variants D and F, which as noted previously are expressed at reduced levels (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 4.

Expression and pore activity of the P2X7 constructs with single amino acid substitutions. a Schematic representation of the series of point mutation constructs created based on the sequence of the Reference (GenBank accession number Y09561). b Comparison of protein expression in stably transfected HEK293 cells for the point-mutated constructs as measured by FACS analysis following permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody. The MFI value (mean fluorescence intensity) shown on the right refers to the value for all cells following live-cell gating based on forward scatter, while the percentage of positive cells were derived based on gating relative to the mock transfected cells, as shown in Fig. 2a. c PI uptake by the HEK293 cells stably transfected with each of the point-mutated constructs induced by 300 µM or 1,000 µM BzATP. Net dye uptake indicates the percentage dye uptake induced by BzATP with control (no BzATP treatment) subtracted. The data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments and two-tailed Student’s t tests (unpaired) compared to Reference (R) yielded significance levels of <0.05(*) or <0.001 (***) as shown in b and c

Transfectants expressing these point mutants were tested for their ability to form pores. As shown in Fig. 4c, a single-base mutation at position 523 nt (A166G) of Reference cDNA caused a nearly threefold increase in PI dye uptake induced by 300 µM BzATP compared to the Reference, but displayed little difference in response to 1,000 µM BzATP. In contrast, nearly complete loss of the dye uptake was found in the mutant with a single-base mutation at position 1513 nt (E496A), consistent with a previous study [54]. Lack of dye uptake was also seen with Variants D and F that contain this E496A base mutation, as summarized in Fig. 3c. No significant alterations in dye uptake were observed for the V80M and H270R mutants compared to the Reference (Fig. 4c). The A348T mutation induced a slight increase in response at the lower concentration of BzATP. In summary, these data clearly demonstrate that the A166G substitution confers a significant gain of function in the human P2X7 receptor, which is critical for the increased pore formation phenotype of Variant A (Figs. 1c and 3).

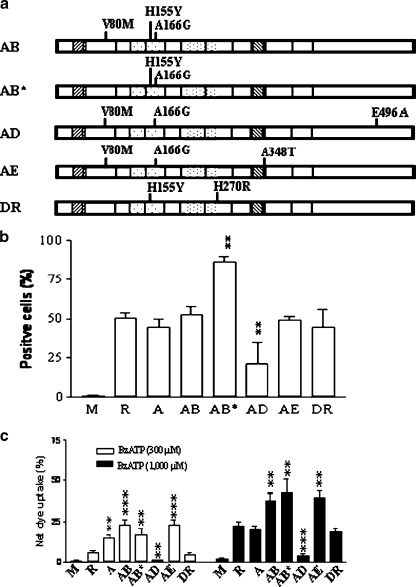

Combinatorial effect of multiple nucleotide substitutions in human P2X7 receptor

In order to further explore combinatorial effects of multiple nucleotide substitutions on human P2X7 function, selected multiple nucleotide mutants among the P2X7 cDNA variants found in this study were constructed (Fig. 5a). The constructs were then assayed for their expression levels (Fig. 5b) and pore formation function (Fig. 5c) in stably transfected HEK293 cells. Construct AB containing the new-found variations (V80M and A166G) and a known gain-of-function SNP (H155Y) showed a synergistic effect on pore formation induced by both 300 µM and 1,000 µM BzATP, with similar expression levels compared to Reference and Variant A. Construct AB* containing the H155Y and A166G variations showed the highest levels of expression and the highest levels of pore formation induced under both 300 µM and 1,000 µM BzATP compared to Reference and Variant A (Fig. 4b and c, also refer to Figs. 2 and 3). A synergistic effect was also observed in the construct AE with the V80M, A166G, and A348T variations relative to the individual substitutions (Table 1). In contrast, construct AD with V80M, A166G and E496A substitutions showed low expression and low pore formation consistent with the dominant negative effect of the E496A substitution (Fig. 4b and c). Construct DR with H155Y and H270R variations demonstrated slight reduction in pore formation at similar expression levels compared to Reference.

Fig. 5.

Combinatorial effects of the P2X7 constructs with multiple base-point mutations. a Schematic representation of the series of constructs created with multiple base-point mutations based on the sequence of the Reference (GenBank accession number Y09561). b Comparison of protein expression in stably transfected HEK293 cells for each of the constructs with multiple base-point mutations as measured by FACS analysis following permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody. c PI dye uptake by the HEK293 cells stably transfected with each of the constructs with multiple base point mutations induced by 300 µM or 1,000 µM BzATP. Net dye uptake indicates the percentage dye uptake induced by BzATP with control (no BzATP treatment) subtracted. The data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments and two-tailed Student’s t tests (unpaired) compared to Reference (R) yielded significance levels of <0.01(**) or <0.001 (***) as shown in b and c

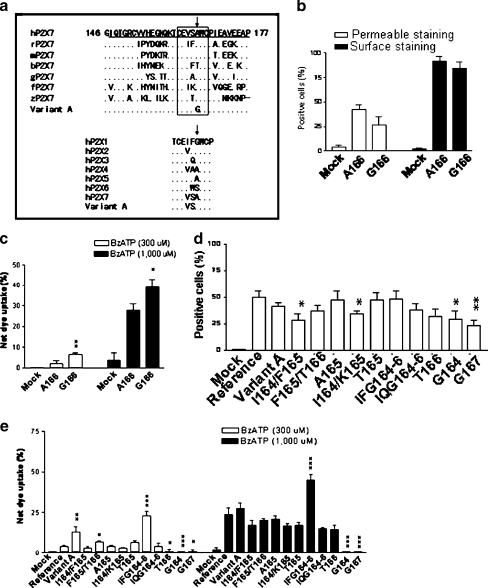

C-terminus of the cysteine-rich domain 1 (CRD 1) of P2X7 critical for regulation of pore formation

Position 166aa is located in the C-terminal portion (around exon 5) of the cysteine-rich domain 1 (CRD1) of human P2X7. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations have been reported previously in this region [58, 59] in addition to the A166G reported in this study. The region is located between the last two cysteine residues of CRD1. The residues among different species of P2X7 and those among all of human P2X receptors are relatively conserved in length (Fig. 6a). We next analyzed this region in finer detail by mutating residues within the C-terminal CRD1. Both the human P2X7 Reference and a mouse P2X7 clone derived from C57BL6 were analyzed. As summarized in Fig. 6b and c, mouse P2X7 with an A166G substitution exhibited significantly higher PI uptake than wild type after 300 µM and 1,000 µM BzATP exposure. Furthermore, additional substitutions at aa positions 164 to 167 were tested as summarized in Fig. 6d and e. Decreased expression was observed following substitution at positions 164 and 167 (I164/F165, I164/K165, G164, and G167). However, significant changes in PI uptake were only observed in constructs with mutations in position 166 like constructs F165/T166, IFG164-6, and T166 compared to the Reference (Fig. 6e). The loss of function resulting from the constructs with G164 and G167 mutations demonstrated that the gain-of-function G166 mutation is position specific. Gain of function was also seen following certain substitutions. Construct IFG164-6 had significantly increased PI uptake induced by 300 µM and 1,000 µM BzATP while construct IQG164-6 had little effect on PI uptake compared to that of Reference (Fig. 6e). Thus, these results support a critical role for the C-terminus of CRD1 in regulating the expression and function of P2X7.

Fig. 6.

Mutagenesis analyses of the C-terminus of P2X7 cysteine-rich domain I (CRD I). a Sequence alignments of the C-terminus of the cysteine-rich domain I (CRD I) of P2X7 and human P2X receptors. The corresponding region of exon 5 of human P2X7 is underlined. The positions of the new gain-of-function mutation (A166G) is marked with arrows. GenBank accession numbers: human P2X7 (hP2X7, Reference), Y09561, rat P2X7 (rP2X7), X95882, mouse P2X7 (mP2X7), AJ009823, cattle P2X7 (bP2X7), XM_591410, domestic guinea pig P2X7 (gP2X7), EU275201, red jungle fowl P2X7 (fP2X7), XM_001235162, zebrafish P2X7 (zP2X7), AY292647, Human P2X1 (hP2X1), AAC24494, hP2X2, Q9UBL9, hP2X3, P56373, hP2X4, Q99571, hP2X5, Q93086, and hP2X6, NP_005437. b Expression in stably transfected HEK293 cells of mouse P2X7 construct with an A166G mutation as measured by FACS analysis following permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody or surface staining with anti-mouse P2X7 monoclonal antibody and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody. c PI uptake by HEK293 cells stably transfected with mouse P2X7 construct with an A166G mutation induced by 300 µM or 1,000 µM BzATP. d Comparison of the protein expression in stably transfected HEK293 cells for each of the human P2X7 constructs with mutations at the C-terminal end of CRD I as measured by FACS analysis following permeable staining with FITC-conjugated anti-flag M2 monoclonal antibody. e PI uptake by HEK293 cells stably transfected with each of the human P2X7 constructs with mutations at the C-terminus of CRD I induced by 300 µM or 1,000 µM BzATP. Net dye uptake indicates the percentage dye uptake induced by BzATP with control (no BzATP treatment) subtracted. The data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments and two-tailed Student’s t tests (unpaired) compared to Reference (R) yielded significance levels of <0.05(*), <0.01(**), or <0.001 (***) as shown in b–e

Discussion

In the current study, we have used RT-PCR, cloning and a point mutation strategy to identify and isolate human P2X7 cDNA variants from human PBMCs and THP-1 cells. There are two main findings in the study. First, we have identified a novel gain-of-function single-base substitution (A166G) of the human P2X7 gene. Second, we show that the CRD1 domain, where this substitution is localized, is important for the function of human and mouse P2X7.

We identified a novel gain-of-function variant with two nonsynonymous base substitutions, V80M and A166G, in a full-length P2X7 cDNA clone (Variant A). A total of five clones of Variant A were isolated from human PBMC samples, obtained from healthy individual donors making it unlikely that the variant is an artifact resulting from misincorporation errors during RT-PCR. Thus, these mutations might represent new allelic polymorphisms, although this has not been confirmed at the genomic level. Point mutational analyses further demonstrated that the A166G substitution is critical for the gain-of-function of the P2X7 variant (Fig. 3c and d).

Other full-length P2X7 cDNA variants with one or multiple well-known SNPs were also identified in our study. Results from the different phenotypes of P2X7 demonstrated that multiple SNPs affect the function of P2X7. One gain-of-function substitution H155Y, reported by Cabrini et al. [59], was also found in four cDNA variants (Variants B, C, D, and F). Our results showed that this SNP could increase pore formation induced by BzATP, especially when combined with the mutation A166 G (see Variant B in Fig. 3c and Constructs AB and AB* in Fig. 5c). However, pore formation was also affected by other SNPs. For example, loss of function was found in some of the variants (Variant D and F). The previously reported dominant negative effect of E496A is also confirmed in our study [54, 59]. Synergistic effects of multiple substitutions were also observed in the multiple substitution variants between Variant A and B (AB and AB*) and between Variant A and E (AE) (Fig. 5a and c). These indicated that phenotype polymorphisms are dependent on multiple SNPs of P2X7. Moreover, significant synergism was observed in the chimeric variant (AE). These results indicated that A348T is a weak gain-of-function SNP, consistent with those reported by Denlinger et al. [58].

There is increasing evidence that the interactions between the extracellular, intracellular, and membrane-spanning domains influence and regulate P2X7 receptor function. This is especially true for some portions of the extracellular region and the C-terminal intracellular domain. More than ten nonsynonymous SNPs have been identified in the extracellular loop, consisting of 280aa, and the C-terminal intracellular domain. In the extracellular loop of human P2X7, one loss-of-function (G150R) and two gain-of-function (H155Y and A166G) variations are located in the first cysteine-rich domain and only one loss-of-function SNP (R307Q) is at the C-terminus between the second cysteine-rich domain and second membrane-spanning domain (this study and references [57–59]). The large extracellular loop is believed to be responsible for ligand-binding and is quite conserved among the P2X receptors, although the fine structure of the ligand-binding pocket is still uncertain. Conserved positively charged amino acid residues are important for nucleotide binding (K64, K66, R294, R307, and K311) [5, 57, 73–75]. Aromatic amino acids are associated with recognition of adenine nucleotides in many ATP-binding proteins and are proposed to bind the adenine ring [5, 75]. In addition, certain histidine residues within the protein can regulate P2X function [2, 5]. It has been reported that glycine residues enhance flexibility in the extracellular loop, raising the possibility that they are involved in conformational changes in P2X receptors upon agonist binding [2, 76–78]. Swapping fragments and point mutations in the extracellular loop between rat and mouse P2X7 receptors also demonstrated that amino acid residues in the ectodomain of the P2X7 receptor are involved in the differential sensitivity to agonists between species [79]. Our results point to the C-terminal of the first cysteine-rich domain (CRD1) as critical for regulation of P2X7 expression and pore formation.

The unique long C-terminal intracellular domain of P2X7 is crucial for P2X7-induced pore formation, transduction, and signaling [1, 72, 80]. Three loss-of function SNPs (T357S, E496A, and I568N) and one gain-of-function SNP (Q460R) are located in the long intracellular domain [54–56, 58]. These loss-of-function polymorphisms lead not only to reduced P2X7 pore function but also to impaired ATP-induced mycobacterial killing by macrophages [56, 60, 61, 81, 82]. Recent studies have found that the E496A polymorphism does not affect the electrophysiological phenotype of the P2X7 channel in transfected oocytes and HEK293 cells [83]. The E496A functional pore defect significantly impairs the surface expression, but this can be overcome partially when the density of these receptors on the cell surface is massively increased following differentiation of monocytes to macrophages [54]. Our results show that E496A substitution reduces the expression of the P2X7 variants with this mutation in the stably transfected HEK293 cells (Figs. 2b, 4b, and 5b), also observed in transient transfection experiments (data not shown).

Of note, the SNP (A348T) located in the second membrane-spanning domain also affected the pore formation function of P2X7 in our study. The second membrane-spanning domain of the P2X receptor lines the central ion-conduction pore and the gate is positioned deep in the membrane-spanning domain segment, corresponding to the region flanking the SNP [84, 85]. Mutations in the region also alter the permeability of P2X receptor channels for divalent ions [86]. The second membrane-spanning domain is also involved in protein folding and assembly of P2X subunits [87, 88].

In our study, we also identified many P2X7 cDNA variants resulting from alternative splicing (Fig. 1b). Alternative splicing of P2X7 has been reported by others [71, 89–91] and has also been reported for other P2X channel family members [92–96]. Although the role of alternative splicing of the P2X receptor is still unclear, studies have demonstrated that some mis-spliced variants are synthesized as truncated proteins that can interact with full-length receptors to regulate their function [71, 90, 91]. Unlike the other P2X receptors (P2X1–6), P2X7 is usually considered to form fully functional homotrimers, although evidence for functional P2X4/P2X7 heteromeric receptors has also been reported [97]. Interaction of truncated P2X7 proteins with full-length P2X7 through hetero-oligomerization may represent a general paradigm for regulation of protein function by a variant protein encoded by the same gene. The mechanism of the alternative splicing in regulation of P2X7 function remains to be elucidated further, but could potentially be important for regulating receptor function.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants A157168 and CA73743.

Abbreviations

- PI

Propidium iodide

- BzATP

2′,3′-O-(4-benzoyl-benzoyl) ATP

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- MFI

Mean of fluorescence intensity

Footnotes

Footnotes

The sequence of the new gain-of-function P2X7 variant (Variant A) has been submitted to NCBI GenBank database (GeneBank accession number, GQ180122).

References

- 1.Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. The cytolytic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7) Science. 1996;272:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts JA, Vial C, Digby HR, Agboh KC, Wen H, Atterbury-Thomas A, Evans RJ. Molecular properties of P2X receptors. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:486–500. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan TM, Cox JA, Voigt MM. Molecular structure of P2X receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:821–829. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vial C, Roberts JA, Evans RJ. Molecular properties of ATP-gated P2X receptor ion channels. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bretschneider F, Klapperstuck M, Lohn M, Markwardt F. Nonselective cationic currents elicited by extracellular ATP in human B-lymphocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1995;429:691–698. doi: 10.1007/BF00373990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunosewoyo H, Coster MJ, Kassiou M. Molecular probes for P2X7 receptor studies. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1505–1523. doi: 10.2174/092986707780831023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sluyter R, Shemon AN, Barden JA, Wiley JS. Extracellular ATP increases cation fluxes in human erythrocytes by activation of the P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44749–44755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sluyter R, Shemon AN, Hughes WE, Stevenson RO, Georgiou JG, Eslick GD, Taylor RM, Wiley JS. Canine erythrocytes express the P2X7 receptor: greatly increased function compared with human erythrocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R2090–R2098. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00166.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu BJ, Zhang WY, Bendall LJ, Chessell IP, Buell GN, Wiley JS. Expression of P2X(7) purinoceptors on human lymphocytes and monocytes: evidence for nonfunctional P2X(7) receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1189–C1197. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.4.C1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sluyter R, Barden JA, Wiley JS. Detection of P2X purinergic receptors on human B lymphocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:231–236. doi: 10.1007/s004410100372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adinolfi E, Melchiorri L, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Morelli A, Tieghi A, Cuneo A, Castoldi G, Virgilio F, Baricordi OR. P2X7 receptor expression in evolutive and indolent forms of chronic B lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:706–708. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.2.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suh BC, Kim JS, Namgung U, Ha H, Kim KT. P2X7 nucleotide receptor mediation of membrane pore formation and superoxide generation in human promyelocytes and neutrophils. J Immunol. 2001;166:6754–6763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulanova E, Budagian V, Orinska Z, Hein M, Petersen F, Thon L, Adam D, Bulfone-Paus S. Extracellular ATP induces cytokine expression and apoptosis through P2X7 receptor in murine mast cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3880–3890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idzko M, Panther E, Bremer HC, Sorichter S, Luttmann W, Virchow CJ, Jr, Virgilio F, Herouy Y, Norgauer J, Ferrari D. Stimulation of P2 purinergic receptors induces the release of eosinophil cationic protein and interleukin-8 from human eosinophils. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1244–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudipaty L, Humphreys BD, Buell G, Dubyak GR. Regulation of P2X(7) nucleotide receptor function in human monocytes by extracellular ions and receptor density. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C943–C953. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang XJ, Zheng GG, Ma XT, Lin YM, Song YH, Wu KF. Effects of various inducers on the expression of P2X7 receptor in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Shengli xuebao. 2005;57:193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miras-Portugal MT, Diaz-Hernandez M, Giraldez L, Hervas C, Gomez-Villafuertes R, Sen RP, Gualix J, Pintor J. P2X7 receptors in rat brain: presence in synaptic terminals and granule cells. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:1597–1605. doi: 10.1023/A:1025690913206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon D, Hervas C, Miras-Portugal MT. P2Y1 and P2X7 receptors induce calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation in cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J NeuroSci. 2006;23:2999–3013. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marin-Garcia P, Sanchez-Nogueiro J, Gomez-Villafuertes R, Leon D, Miras-Portugal MT. Synaptic terminals from mice midbrain exhibit functional P2X7 receptor. Neuroscience. 2008;151:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang XF, Han P, Faltynek CR, Jarvis MF, Shieh CC. Functional expression of P2X7 receptors in non-neuronal cells of rat dorsal root ganglia. Brain Res. 2005;1052:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bianco F, Ceruti S, Colombo A, Fumagalli M, Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Matteoli M, Virgilio F, Abbracchio MP, Verderio C. A role for P2X7 in microglial proliferation. J Neurochem. 2006;99:745–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bianco F, Fumagalli M, Pravettoni E, D'Ambrosi N, Volonte C, Matteoli M, Abbracchio MP, Verderio C. Pathophysiological roles of extracellular nucleotides in glial cells: differential expression of purinergic receptors in resting and activated microglia. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiyama T, Kawamura H, Yamanishi S, Kobayashi M, Katsumura K, Puro DG. Regulation of P2X7-induced pore formation and cell death in pericyte-containing retinal microvessels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C568–C576. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Liu D, Ke HZ, Duncan RL, Turner CH. The P2X7 nucleotide receptor mediates skeletal mechanotransduction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42952–42959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penolazzi L, Bianchini E, Lambertini E, Baraldi PG, Romagnoli R, Piva R, Gambari R. N-arylpiperazine modified analogues of the P2X7 receptor KN-62 antagonist are potent inducers of apoptosis of human primary osteoclasts. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:1013–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlendorff SD, Tofteng CL, Jensen JE, Petersen S, Civitelli R, Fenger M, Abrahamsen B, Hermann AP, Eiken P, Jorgensen NR. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the P2X7 gene are associated to fracture risk and to effect of estrogen treatment. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:555–567. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3280951625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Luo X, Zeng W, Muallem S. Cell-specific behavior of P2X7 receptors in mouse parotid acinar and duct cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47554–47561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu HZ, Gao N, Lin Z, Gao C, Liu S, Ren J, Xia Y, Wood JD. P2X(7) receptors in the enteric nervous system of guinea-pig small intestine. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:299–310. doi: 10.1002/cne.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hillman KA, Burnstock G, Unwin RJ. The P2X7 ATP receptor in the kidney: a matter of life or death? Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;101:e24–e30. doi: 10.1159/000086036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koshi R, Coutinho-Silva R, Cascabulho CM, Henrique-Pons A, Knight GE, Loesch A, Burnstock G. Presence of the P2X(7) purinergic receptor on immune cells that invade the rat endometrium during oestrus. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;66:127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emmett DS, Feranchak A, Kilic G, Puljak L, Miller B, Dolovcak S, McWilliams R, Doctor RB, Fitz JG. Characterization of ionotrophic purinergic receptors in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;47:698–705. doi: 10.1002/hep.22035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verhoef PA, Estacion M, Schilling W, Dubyak GR. P2X7 receptor-dependent blebbing and the activation of Rho-effector kinases, caspases, and IL-1 beta release. J Immunol. 2003;170:5728–5738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franke H, Gunther A, Grosche J, Schmidt R, Rossner S, Reinhardt R, Faber-Zuschratter H, Schneider D, Illes P. P2X7 receptor expression after ischemia in the cerebral cortex of rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:686–699. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.7.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wirkner K, Kofalvi A, Fischer W, Gunther A, Franke H, Groger-Arndt H, Norenberg W, Madarasz E, Vizi ES, Schneider D, Sperlagh B, Illes P. Supersensitivity of P2X receptors in cerebrocortical cell cultures after in vitro ischemia. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1421–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feuvre R, Brough D, Rothwell N. Extracellular ATP and P2X7 receptors in neurodegeneration. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;447:261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01848-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rampe D, Wang L, Ringheim GE. P2X7 receptor modulation of beta-amyloid- and LPS-induced cytokine secretion from human macrophages and microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al Shukaili A, Al Kaabi J, Hassan B. A comparative study of interleukin-1beta production and p2x7 expression after ATP stimulation by peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from rheumatoid arthritis patients and normal healthy controls. Inflammation. 2008;31:84–90. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nath SK, Quintero-Del-Rio AI, Kilpatrick J, Feo L, Ballesteros M, Harley JB. Linkage at 12q24 with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is established and confirmed in Hispanic and European American families. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:73–82. doi: 10.1086/380913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott JI, McVey JH, Higgins CF. The P2X7 receptor is a candidate product of murine and human lupus susceptibility loci: a hypothesis and comparison of murine allelic products. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R468–R475. doi: 10.1186/ar1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chessell IP, Hatcher JP, Bountra C, Michel AD, Hughes JP, Green P, Egerton J, Murfin M, Richardson J, Peck WL, Grahames CB, Casula MA, Yiangou Y, Birch R, Anand P, Buell GN. Disruption of the P2X7 purinoceptor gene abolishes chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;114:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Labasi JM, Petrushova N, Donovan C, McCurdy S, Lira P, Payette MM, Brissette W, Wicks JR, Audoly L, Gabel CA. Absence of the P2X7 receptor alters leukocyte function and attenuates an inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2002;168:6436–6445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharp AJ, Polak PE, Simonini V, Lin SX, Richardson JC, Bongarzone ER, Feinstein DL. P2x7 deficiency suppresses development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alcaraz L, Baxter A, Bent J, Bowers K, Braddock M, Cladingboel D, Donald D, Fagura M, Furber M, Laurent C, Lawson M, Mortimore M, McCormick M, Roberts N, Robertson M. Novel P2X7 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:4043–4046. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furber M, Alcaraz L, Bent JE, Beyerbach A, Bowers K, Braddock M, Caffrey MV, Cladingboel D, Collington J, Donald DK, Fagura M, Ince F, Kinchin EC, Laurent C, Lawson M, Luker TJ, Mortimore MM, Pimm AD, Riley RJ, Roberts N, Robertson M, Theaker J, Thorne PV, Weaver R, Webborn P, Willis P. Discovery of potent and selective adamantane-based small-molecule P2X(7) receptor antagonists/interleukin-1beta inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5882–5885. doi: 10.1021/jm700949w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stokes L, Jiang LH, Alcaraz L, Bent J, Bowers K, Fagura M, Furber M, Mortimore M, Lawson M, Theaker J, Laurent C, Braddock M, Surprenant A. Characterization of a selective and potent antagonist of human P2X(7) receptors, AZ11645373. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:880–887. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baxter A, Bent J, Bowers K, Braddock M, Brough S, Fagura M, Lawson M, McInally T, Mortimore M, Robertson M, Weaver R, Webborn P. Hit-to-lead studies: the discovery of potent adamantane amide P2X7 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:4047–4050. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothwell N. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury: mechanisms, modification, and therapeutic potential. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:152–157. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baraldi PG, Virgilio F, Romagnoli R. Agonists and antagonists acting at P2X7 receptor. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:1707–1717. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baraldi PG, Romagnoli R, Tabrizi MA, Falzoni S, Virgilio F. Synthesis of conformationally constrained analogues of KN62, a potent antagonist of the P2X7-receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:681–684. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fonfria E, Clay WC, Levy DS, Goodwin JA, Roman S, Smith GD, Condreay JP, Michel AD. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of the guinea pig P2X7 receptor orthologue. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:544–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buell GN, Talabot F, Gos A, Lorenz J, Lai E, Morris MA, Antonarakis SE. Gene structure and chromosomal localization of the human P2X7 receptor. Recept Channels. 1998;5:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gu BJ, Zhang W, Worthington RA, Sluyter R, Dao-Ung P, Petrou S, Barden JA, Wiley JS. A Glu-496 to Ala polymorphism leads to loss of function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11135–11142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiley JS, Dao-Ung LP, Li C, Shemon AN, Gu BJ, Smart ML, Fuller SJ, Barden JA, Petrou S, Sluyter R. An Ile-568 to Asn polymorphism prevents normal trafficking and function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17108–17113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shemon AN, Sluyter R, Fernando SL, Clarke AL, Dao-Ung LP, Skarratt KK, Saunders BM, Tan KS, Gu BJ, Fuller SJ, Britton WJ, Petrou S, Wiley JS. A Thr357 to Ser polymorphism in homozygous and compound heterozygous subjects causes absent or reduced P2X7 function and impairs ATP-induced mycobacterial killing by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2079–2086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu BJ, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK, Shemon AN, Dao-Ung LP, Fuller SJ, Barden JA, Clarke AL, Petrou S, Wiley JS. An Arg307 to Gln polymorphism within the ATP-binding site causes loss of function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31287–31295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Denlinger LC, Coursin DB, Schell K, Angelini G, Green DN, Guadarrama AG, Halsey J, Prabhu U, Hogan KJ, Bertics PJ. Human P2X7 pore function predicts allele linkage disequilibrium. Clin Chem. 2006;52:995–1004. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.065425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cabrini G, Falzoni S, Forchap SL, Pellegatti P, Balboni A, Agostini P, Cuneo A, Castoldi G, Baricordi OR, Virgilio F. A His-155 to Tyr polymorphism confers gain-of-function to the human P2X7 receptor of human leukemic lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2005;175:82–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK, Goldberg H, Marks GB, Wiley JS, Britton WJ. A polymorphism in the P2X7 gene increases susceptibility to extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:360–366. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-970OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saunders BM, Fernando SL, Sluyter R, Britton WJ, Wiley JS. A loss-of-function polymorphism in the human P2X7 receptor abolishes ATP-mediated killing of mycobacteria. J Immunol. 2003;171:5442–5446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiley JS, Dao-Ung LP, Gu BJ, Sluyter R, Shemon AN, Li C, Taper J, Gallo J, Manoharan A. A loss-of-function polymorphic mutation in the cytolytic P2X7 receptor gene and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a molecular study. Lancet. 2002;359:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thunberg U, Tobin G, Johnson A, Soderberg O, Padyukov L, Hultdin M, Klareskog L, Enblad G, Sundstrom C, Roos G, Rosenquist R. Polymorphism in the P2X7 receptor gene and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2002;360:1935–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dao-Ung LP, Fuller SJ, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK, Thunberg U, Tobin G, Byth K, Ban M, Rosenquist R, Stewart GJ, Wiley JS. Association of the 1513C polymorphism in the P2X7 gene with familial forms of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:815–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barden N, Harvey M, Gagne B, Shink E, Tremblay M, Raymond C, Labbe M, Villeneuve A, Rochette D, Bordeleau L, Stadler H, Holsboer F, Muller-Myhsok B. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes in the chromosome 12Q24.31 region points to P2RX7 as a susceptibility gene to bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141:374–382. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hejjas K, Szekely A, Domotor E, Halmai Z, Balogh G, Schilling B, Sarosi A, Faludi G, Sasvari-Szekely M, Nemoda Z. Association between depression and the Gln460Arg polymorphism of P2RX7 Gene: A dimensional approach. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B(2):295–299. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elliott JI, Higgins CF. Major histocompatibility complex class I shedding and programmed cell death stimulated through the proinflammatory P2X7 receptor: a candidate susceptibility gene for NOD diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:2012–2017. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee KH, Park SS, Kim I, Kim JH, Ra EK, Yoon SS, Hong YC, Park S, Kim BK. P2X7 receptor polymorphism and clinical outcomes in HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2007;92:651–657. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang B, Sun C, Jin S, Cascio M, Montelaro RC. Mapping of equine lentivirus receptor 1 residues critical for equine infectious anemia virus envelope binding. J Virol. 2008;82:1204–1213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01393-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun C, Zhang B, Jin J, Montelaro RC. Binding of equine infectious anemia virus to the equine lentivirus receptor-1 is mediated by complex discontinuous sequences in the viral envelope gp90 protein. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2011–2019. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheewatrakoolpong B, Gilchrest H, Anthes JC, Greenfeder S. Identification and characterization of splice variants of the human P2X7 ATP channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rassendren F, Buell GN, Virginio C, Collo G, North RA, Surprenant A. The permeabilizing ATP receptor, P2X7. Cloning and expression of a human cDNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5482–5486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiang LH, Rassendren F, Surprenant A, North RA. Identification of amino acid residues contributing to the ATP-binding site of a purinergic P2X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34190–34196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ennion S, Hagan S, Evans RJ. The role of positively charged amino acids in ATP recognition by human P2X1 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Worthington RA, Smart ML, Gu BJ, Williams DA, Petrou S, Wiley JS, Barden JA. Point mutations confer loss of ATP-induced human P2X(7) receptor function. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:43–46. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakazawa K, Ohno Y. Neighboring glycine residues are essential for P2X2 receptor/channel function. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;370:R5–R6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Digby HR, Roberts JA, Sutcliffe MJ, Evans RJ. Contribution of conserved glycine residues to ATP action at human P2X1 receptors: mutagenesis indicates that the glycine at position 250 is important for channel function. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1746–1754. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roberts JA, Digby HR, Kara M, El Ajouz S, Sutcliffe MJ, Evans RJ. Cysteine substitution mutagenesis and the effects of methanethiosulfonate reagents at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors support a core common mode of ATP action at P2X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20126–20136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800294200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Young MT, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Amino acid residues in the P2X7 receptor that mediate differential sensitivity to ATP and BzATP. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:92–100. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu Y, Fisette PL, Denlinger LC, Guadarrama AG, Sommer JA, Proctor RA, Bertics PJ. Purinergic receptor modulation of lipopolysaccharide signaling and inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27170–27175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Britton WJ, Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R, Wiley JS. The genetic control of susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;281:79–89. doi: 10.1002/9780470062128.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK, Wiley JS, Britton WJ. Gene dosage determines the negative effects of polymorphic alleles of the P2X7 receptor on adenosine triphosphate-mediated killing of mycobacteria by human macrophages. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:149–155. doi: 10.1086/430622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boldt W, Klapperstuck M, Buttner C, Sadtler S, Schmalzing G, Markwardt F. Glu496Ala polymorphism of human P2X7 receptor does not affect its electrophysiological phenotype. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C749–C756. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00042.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li M, Chang TH, Silberberg SD, Swartz KJ. Gating the pore of P2X receptor channels. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:883–887. doi: 10.1038/nn.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rassendren F, Buell G, Newbolt A, North RA, Surprenant A. Identification of amino acid residues contributing to the pore of a P2X receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:3446–3454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Migita K, Haines WR, Voigt MM, Egan TM. Polar residues of the second transmembrane domain influence cation permeability of the ATP-gated P2X(2) receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30934–30941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Denlinger LC, Sommer JA, Parker K, Gudipaty L, Fisette PL, Watters JW, Proctor RA, Dubyak GR, Bertics PJ. Mutation of a dibasic amino acid motif within the C terminus of the P2X7 nucleotide receptor results in trafficking defects and impaired function. J Immunol. 2003;171:1304–1311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duckwitz W, Hausmann R, Aschrafi A, Schmalzing G. P2X5 subunit assembly requires scaffolding by the second transmembrane domain and a conserved aspartate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39561–39572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Georgiou JG, Skarratt KK, Fuller SJ, Martin CJ, Christopherson RI, Wiley JS, Sluyter R. Human epidermal and monocyte-derived Langerhans cells express functional P2X receptors. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feng YH, Li X, Zeng R, Gorodeski GI. Endogenously expressed truncated P2X7 receptor lacking the C-terminus is preferentially upregulated in epithelial cancer cells and fails to mediate ligand-induced pore formation and apoptosis. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2006;25:1271–1276. doi: 10.1080/15257770600890921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Feng YH, Li X, Wang L, Zhou L, Gorodeski GI. A truncated P2X7 receptor variant (P2X7-j) endogenously expressed in cervical cancer cells antagonizes the full-length P2X7 receptor through hetero-oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17228–17237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602999200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hardy LA, Harvey IJ, Chambers P, Gillespie JI. A putative alternatively spliced variant of the P2X(1) purinoreceptor in human bladder. Exp Physiol. 2000;85:461–463. doi: 10.1017/S0958067000003572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lynch KJ, Touma E, Niforatos W, Kage KL, Burgard EC, Biesen T, Kowaluk EA, Jarvis MF. Molecular and functional characterization of human P2X(2) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1171–1181. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brandle U, Spielmanns P, Osteroth R, Sim J, Surprenant A, Buell G, Ruppersberg JP, Plinkert PK, Zenner HP, Glowatzki E. Desensitization of the P2X(2) receptor controlled by alternative splicing. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:294–298. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dhulipala PD, Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. The human P2X4 receptor gene is alternatively spliced. Gene. 1998;207:259–266. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Townsend-Nicholson A, King BF, Wildman SS, Burnstock G. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and possible cooperativity between the murine P2X4 and P2X4a receptors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;64:246–254. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo C, Masin M, Qureshi OS, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Evidence for functional P2X4/P2X7 heteromeric receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1447–1456. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]