Summary

Background

Polyphosphate is secreted by activated platelets and we recently showed that it accelerates blood clotting, chiefly by triggering the contact pathway and promoting factor V activation.

Results

We now report that polyphosphate significantly shortened the clotting time of plasmas from hemophilia A and B patients and that its procoagulant effect was additive to that of recombinant factor VIIa. Polyphosphate also significantly shortened the clotting time of normal plasmas containing a variety of anticoagulant drugs, including unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin (a low MW heparin), argatroban (a direct thrombin inhibitor) and rivaroxaban (a direct factor Xa inhibitor). Thromboelastography revealed that polyphosphate normalized the clotting dynamics of whole blood containing these anticoagulants, as indicated by changes in clot time, clot formation time, alpha angle and maximum clot firmness. Experiments in which pre-formed factor Va was added to plasma support the notion that polyphosphate antagonizes the anticoagulant effect of these drugs via accelerating factor V activation. Polyphosphate also shortened the clotting times of plasmas from warfarin patients.

Conclusion

These results suggest that polyphosphate may have utility in reversing anticoagulation and in treating bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia.

Keywords: argatroban, warfarin, enoxaparin, hemophilia, heparin, rivaroxaban, factor V

Introduction

Uncontrolled hemorrhage can be a life-threatening problem for individuals with clotting factor deficiencies such as hemophilia and may also be a serious complication for patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy. Even when patients are on stable anticoagulant therapy, emergent circumstances may necessitate immediate reversal of anticoagulant status. Rapid normalization of abnormal coagulation generally requires either replacing missing clotting factors or administering specific antidotes [1,2]. For patients receiving warfarin, anticoagulation can be rapidly reversed via transfusing normal coagulation factors or more slowly with vitamin K therapy, while heparin can be rapidly reversed with protamine [2]. On the other hand, most newly approved anticoagulant drugs – and some under development – lack specific antidotes. Recombinant human factor VIIa (rFVIIa) is approved for managing hemorrhage in hemophilia patients with inhibitors [3,4]. More recently, in vitro studies as well as experiences with off-label use in patients suggest that rFVIIa may have general utility in reversing anticoagulant therapy [5–11], although rFVIIa administration may sometimes be associated with adverse thromboembolic events [12,13]. Currently, the primary factors limiting use of rFVIIa as a universal procoagulant are high cost and potential liability associated with off-label use.

Polyphosphate (polyP) is a linear polymer of inorganic phosphate that is present in dense granules of human platelets [14,15]. PolyP is released from activated platelets and is cleared from plasma by degradation by plasma phosphatases [14,16]. We recently reported that polyP is a potent hemostatic regulator, accelerating blood coagulation by activating the contact pathway and by promoting factor (F) V activation, which in turn abrogates the anticoagulant function of tissue factor pathway inhibitor [16]. These combined effects of polyP shift the timing of thrombin generation without changing the total amount of thrombin generated. Most recently, we reported that polyP modulates fibrin clot structure, resulting in thicker fibrin fibers that are more resistant to fibrinolysis [17].

Because polyP causes an earlier burst of thrombin generation during plasma clotting, we hypothesized that polyP would also exhibit procoagulant effects under circumstances in which coagulation was impaired, including clotting factor deficiencies or anticoagulant therapy. We now report that polyP shortened the time to clot formation in normal plasma to which various anticoagulants were added in vitro. It also normalized clot dynamics in whole blood containing these anticoagulant drugs, as measured by thromboelastography. Furthermore, polyP shortened the clotting time of plasmas from warfarin patients and individuals with hemophilia A or B. PolyP was as effective as adding the missing clotting factors or rFVIIa in normalizing the clotting times of hemophilia plasmas.

Materials and methods

Reagents and plasma samples

Enoxaparin (Lovenox) was from Aventis (Bridgewater, NJ, USA), argatroban was from GlaxoSmithKline (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) and rivaroxaban was a gift from Bayer HealthCare (Berkeley, CA, USA). PolyP (mean polymer size, 75 phosphate units; sold as “sodium phosphate glass”) and unfractionated heparin were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PolyP concentrations are expressed herein in terms of phosphate monomer. FIX and FVa were from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN, USA), recombinant FVIII (Kogenate-FS®) was a kind gift of Bayer HealthCare (Berkeley, CA, USA), and rFVIIa was from American Diagnostica (Stamford, CT, USA). Hemoliance Recombiplastin® was from Instrumentation Laboratory (Lexington, MA, USA) and Innovin® from Dade Behring (Newark, DE, USA).

Pooled normal plasma and plasmas congenitally deficient in FVIII (<1% activity) or FIX (<1% activity) were from George King Biomedical (Overland Park, KS, USA). FV-immunodepleted plasma was from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT, USA). Plasmas from patients stably anticoagulated with warfarin were from the Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, IL, USA). Plasmas were stored at −70°C, thawed at 37°C for 5 min, and then held at room temperature for no more than 30 min prior to clotting tests. Fresh whole blood for thromboelastography was collected from healthy, adult, non-smoking volunteers not receiving any medication. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the Carle Foundation Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from volunteer blood donors.

Plasma clotting tests

Anticoagulant drugs were added to pooled normal plasma at amounts selected to span therapeutic and supratherapeutic concentrations: up to 1 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin, 100 μg mL−1 enoxaparin, 3 μg mL−1 argatroban, or 1 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban. (For comparison, therapeutic ranges for unfractionated heparin and enoxaparin are generally 0.3–0.7 U mL−1 and 0.6–1.0 U mL−1 (equivalent to 6–10 μg mL−1) by anti FXa activity respectively [18]. Steady-state plasma concentrations for argatroban were reported to be 0.5–0.7 μg mL−1 [19]. Mean peak plasma concentrations for rivaroxaban administered to orthopedic patients were reported to be 0.2 μg mL−1 [20].)

In some experiments, clotting times of FV-deficient or pooled normal plasma spiked with FVa were evaluated with or without added anticoagulant drugs (0.4 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin, 30 μg mL−1 enoxaparin,1 μg mL−1 argatroban, or 0.7 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban). In others, clotting times of FVIII-deficient plasma were evaluated with or without adding up to 0.5 μg mL−1 FVIII or 20 nM FVIIa. Clotting times of FIX-deficient plasmas were evaluated with or without adding up to 4 μg mL−1 FIX or 20 nM FVIIa.

Plasma clotting times were quantified in 96-well polystyrene microplates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) by adding 80 μL plasma followed by 160 μL diluted thromboplastin (Recombiplastin diluted 200-fold for normal plasmas ± anticoagulant, or 8000-fold for hemophilia plasmas ± anticoagulant) in a buffer containing 100 μM sonicated liposomes (20% phosphatidylserine, 80% phosphatidylcholine), 12.5 mM CaCl2, 25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 150 mM NaCl. Low concentrations of tissue factor were employed to obtain significantly prolonged clotting times in the presence of anticoagulant drugs or with factor-deficient plasmas. When present, 100 μM polyP was added directly to the diluted thromboplastin. Clotting was monitored by turbidity change (A405) for 1 h at room temperature using a Spectramax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Clotting times were calculated using SigmaPlot 7.101 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) by fitting a line to the steepest segment of the absorbance curve and determining its intersection with the initial baseline A405 (representing the lag phase prior to clot formation). Assays were repeated 5 times.

Whole blood thromboelastography

Thromboelastography was performed using the ROTEM® 4-channel system (Pentapharm, Munich, Germany) and the supplied software. Fresh, non-anticoagulated whole blood was collected via atraumatic venipuncture (discarding the initial 3 mL), then immediately transferred to the supplied disposable plastic cups (280 μL per cup) and thoroughly mixed with either 20 μL TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) or 20 μL TBS plus the indicated additives (polyP and/or anticoagulant drugs). Each sample was divided into 4 cups containing: TBS only (control), polyP, anticoagulant drug, or polyP plus anticoagulant drug. Clotting was initiated by adding 20 μL diluted Innovin (in TBS) within 2 min of blood collection. Final concentrations were 87.5% whole blood, 1:17,000 dilution of Innovin, 0 or 100 μM polyP, and either no added anticoagulant drug or one of the following: 0.1 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin, 2.7 μg mL−1 enoxaparin,1 μg mL−1 argatroban, or 0.2 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban. Measurements were continued for 2 h and thromboelastography parameters were recorded using ROTEM software. Effects of each anticoagulant were tested by adding the drug to whole blood from 5 different individuals.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 2.03 (SPSS, Inc.). To account for inter-individual variation, thromboelastography parameters were compared using paired, two-tailed t-tests with significance of p < 0.05. Pairwise comparisons for each blood donor were made between results with versus without additive. In addition, pairwise comparisons were performed between blood containing anticoagulant versus blood containing anticoagulant plus polyP.

Results

PolyP reverses the anticoagulant effect of four drugs in plasma clotting assays

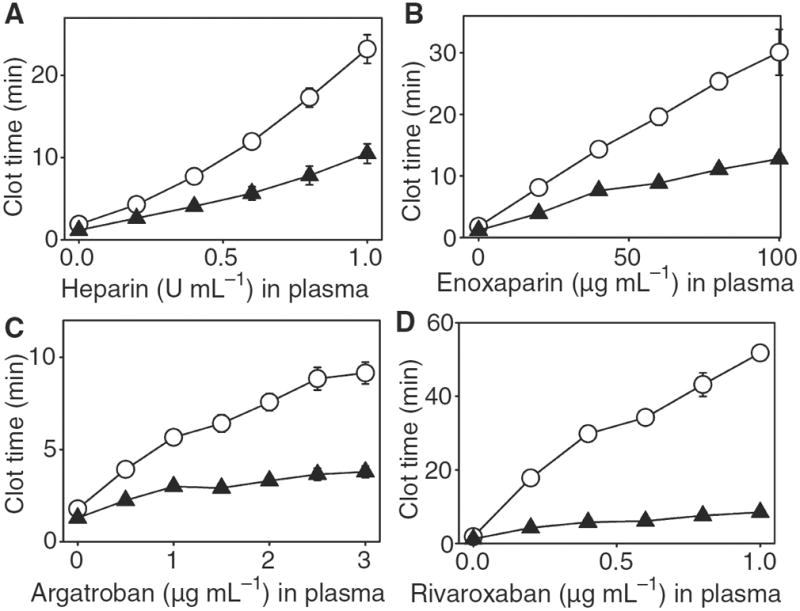

We examined the ability of polyP of the size secreted by human platelets (~75 phosphate units long) to reverse the anticoagulant effect of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin (a low MW heparin that acts as an indirect FXa inhibitor), argatroban (a direct thrombin inhibitor), or rivaroxaban (a direct FXa inhibitor). Drugs were added to pooled normal plasma at concentrations spanning therapeutic and supratherapeutic levels. Clotting was initiated by dilute thromboplastin, and we compared the clotting times with no added polyP to those obtained with 100 μM polyP. Each drug prolonged the clotting time in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PolyP antagonizes the anticoagulant effect of heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban and rivaroxaban. (A) Unfractionated heparin, (B) enoxaparin, (C) argatroban or (D) rivaroxaban were added at the indicated concentrations to pooled normal plasma, after which clotting was initiated by dilute thromboplastin. Clotting reactions contained either 100 μM polyP(▲) or no polyP (○). Data are mean ± standard error (n = 5).

PolyP antagonized the anticoagulant effect of both unfractionated and low MW heparin, shortening the clotting time by approximately 50% at all heparin concentrations evaluated (Fig. 1A&B). This is an approximately 50% reversal of the effective heparin dose.

PolyP shortened the clotting time at all argatroban concentrations tested (Fig. 1C). In the presence of polyP, concentrations of argatroban above 1 μg mL−1 failed to further prolong the clotting time. Consequently, the effects of supratherapeutic plasma levels of argatroban (1–3 μg mL−1) were blunted by polyP, resulting in a milder prolongation of clotting time equivalent to that obtained with argatroban at 0.5 μg mL−1.

Of the four anticoagulant drugs tested, polyP was most effective at reversing the anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban (Fig. 1D), causing an approximately 80% reduction in clotting time at all rivaroxaban concentrations tested.

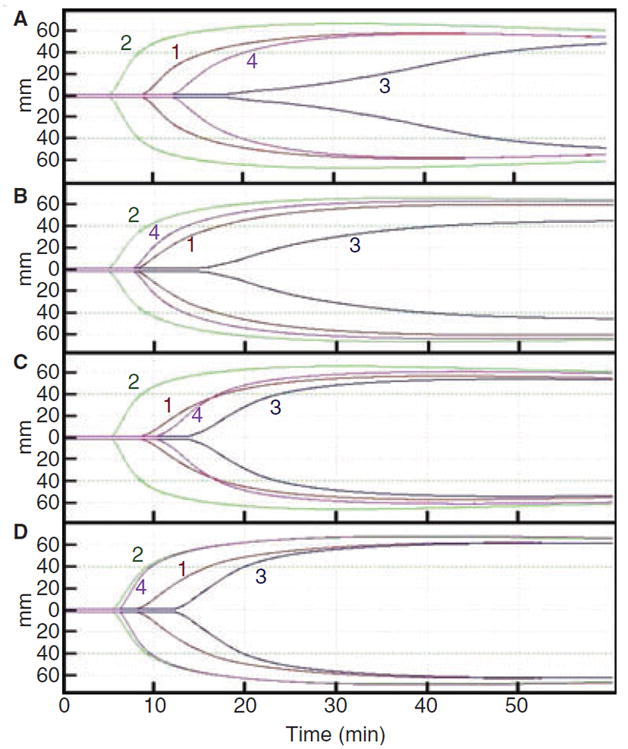

PolyP reverses the anticoagulant effect of four drugs in whole blood thromboelastography

PolyP also reversed the anticoagulant effects of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban, and rivaroxaban in whole blood. As can be seen in Fig. 2A and Table 1, thromboelastography showed that adding 0.1 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin to blood prolonged both the clot time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT), and it also decreased the α angle and maximum clot firmness (MCF). PolyP shortened, but did not completely normalize CT, whereas polyP completely normalized parameters related to the kinetics of increase in clot firmness (CFT and α angle) and final clot firmness (MCF).

Fig. 2.

Whole blood thromboelastography tracings showing that polyP reverses the anticoagulant effect of heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban and rivaroxaban. (A) Unfractionated heparin, (B) enoxaparin, (C) argatroban or (D) rivaroxaban were added to fresh whole blood. Each blood sample was divided into four aliquots receiving the following additions: (1) no additive (red curve); (2) 100 μM polyP (green curve); (3) anticoagulant (blue curve); or (4) anticoagulant plus 100 μM polyP (pink curve). Clotting was initiated with dilute thromboplastin.

Table 1.

Thromboelastography parameters

| Parameter | No additive | +polyP | +Anticoagulant | +Anticoagulant and polyP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated heparin | ||||

| CT (s) | 8.0 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.3)* | 18.8 (1.0)* | 11.5 (1.0)*‡ |

| CFT (s) | 4.4 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.1)* | 14.9 (1.7)* | 4.5 (0.8)‡ |

| α angle (°) | 47.2 (4.3) | 69.6 (1.6)* | 18.2 (1.7)* | 46.8 (4.6)‡ |

| MCF (mm) | 52.8 (1.6) | 63.0 (1.8)* | 42.4 (2.1)* | 52.4 (2.7)‡ |

| Enoxaparin | ||||

| CT (s) | 6.9 (1.8) | 4.8 (0.6)* | 12.9 (2.2)* | 8.0 (0.7)‡ |

| CFT (s) | 3.5 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.1)* | 7.6 (1.4)* | 2.7 (1.0)‡ |

| α angle (°) | 53.0 (5.1) | 71.0 (1.2)* | 31.4 (5.5)* | 60.4 (7.8)‡ |

| MCF (mm) | 57.4 (4.9) | 64.8 (2.3)* | 47.0 (3.2)* | 59.8 (2.6)‡ |

| Argatroban | ||||

| CT (s) | 8.1 (0.9) | 5.1 (0.6)* | 14.0 (1.3)* | 10.4 (0.9)*‡ |

| CFT (s) | 4.4 (1.7) | 1.8 (0.5)* | 6.2 (2.4)* | 3.1 (0.5)‡ |

| α angle (°) | 48.0 (11.7) | 69.0 (6.2)* | 38.8 (9.4)* | 56.4 (3.9)‡ |

| MCF (mm) | 55.0 (7.3) | 62.2 (4.8)* | 49.4 (6.8)* | 59.4 (5.3)*‡ |

| Rivaroxaban | ||||

| CT (s) | 7.9 (1.8) | 5.4 (0.5)* | 11.7 (1.1)* | 6.7 (0.8)‡ |

| CFT (s) | 3.9 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.2)* | 4.3 (1.3) | 1.9 (0.5)*‡ |

| α angle (°) | 49.6 (5.2) | 70.0 (2.4)* | 47.6 (8.5) | 67.4 (5.0)*‡ |

| MCF (mm) | 55.4 (7.0) | 64.0 (4.5)* | 54.8 (8.6) | 63.6 (4.8)*‡ |

Significantly different from value for blood with no additive.

Significantly different from value for blood containing anticoagulant without polyP.

Adding 2.7 μg mL−1 enoxaparin prolonged both CT and CFT, and it decreased α angle and MCF (Fig. 2B and Table 1). PolyP essentially normalized all four parameters.

As with the heparins, adding 1 μg mL−1 argatroban prolonged both CT and CFT, and decreased the α angle and MCF (Fig. 2C and Table 1). Adding polyP normalized CFT, α angle and MFT, but CT was still somewhat prolonged.

Adding 0.2 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban prolonged the CT but did not significantly alter CFT, α angle or MCF (Fig. 2D and Table 1). Adding polyP plus rivaroxaban normalized the prolonged CT value. PolyP actually shifted the other thromboelastography parameters beyond those seen with native blood: it decreased the CFT in the presence of rivaroxaban to a value significantly smaller than that of native blood, and it significantly increased the α angle and MCF relative to native blood. Thus, the thromboelastography curves for blood containing polyP plus rivaroxaban were essentially identical to those for blood containing only polyP, indicating complete reversal of rivaroxaban-dependent anticoagulation.

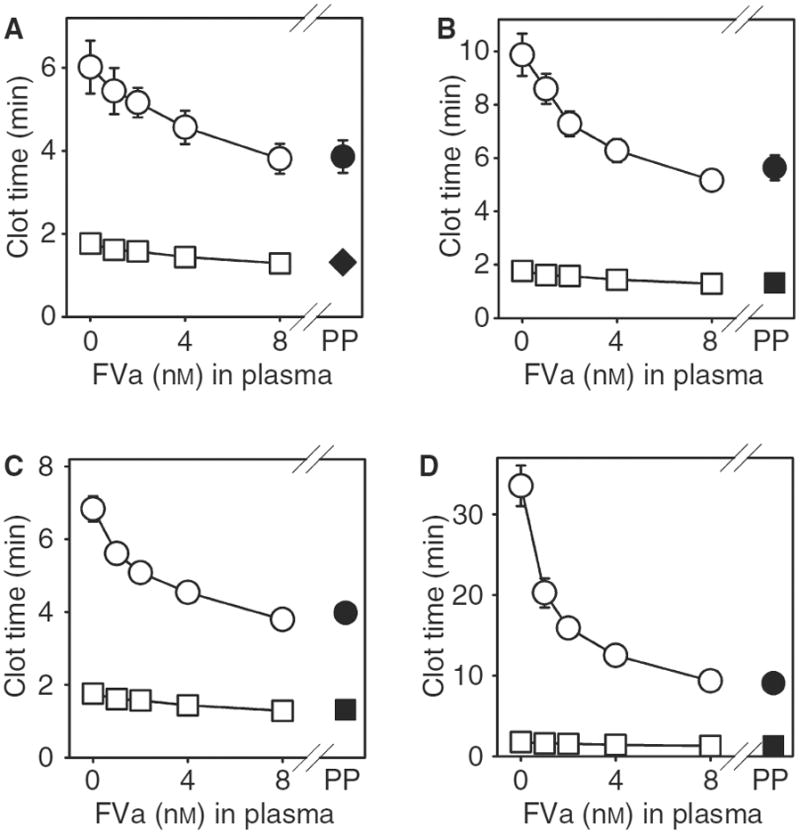

Role of FVa

Our previous work showed that polyP hastens thrombin generation primarily by accelerating FV activation [16]. We therefore hypothesized that polyP antagonizes the anticoagulant effects of the drugs tested above by accelerating FV activation. To test this, we examined the ability of FVa added to normal plasma to antagonize the anticoagulant effects of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban, or rivaroxaban. FVa antagonized the effects of all four drugs, with maximum reductions in clotting times equivalent to those observed with 100 μM polyP in the absence of added FVa (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pre-formed FVa is equivalent to polyP in antagonizing the anticoagulant effect of heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban, and rivaroxaban. Clotting was initiated with dilute thromboplastin using pooled normal plasma containing either the indicated anticoagulant drug (circles) or no drug (squares): (A) 0.4 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin; (B) 30 μg mL−1 enoxaparin; (C) 1 μg mL−1 argatroban; or (D) 0.7 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban. The plasmas also contained the concentrations of added FVa indicated on the x axes (open symbols). For comparison, clotting times are presented for plasma containing 100 μM polyP but no added FVa (closed symbols, indicated as “PP”). Data are mean ± standard error (n = 5).

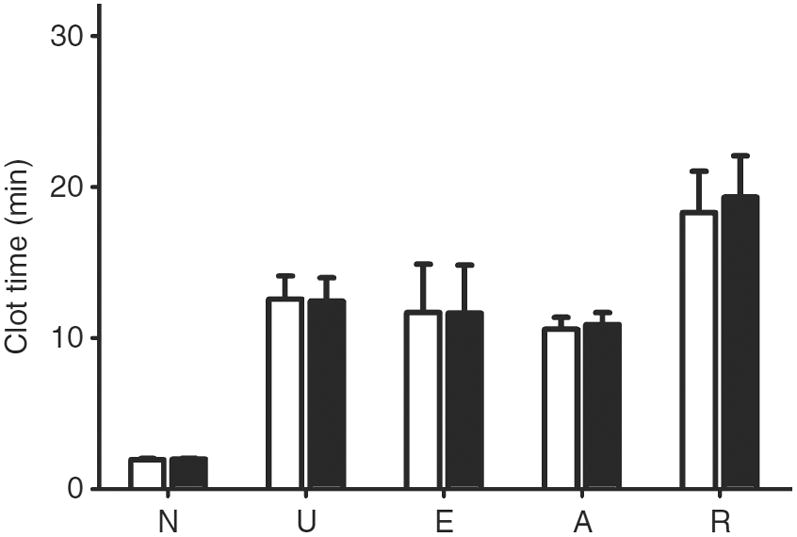

In another test of this hypothesis, we added polyP to FV-deficient plasma that had been spiked with 1 nM FVa. This concentration of FVa will only partially abrogate the anticoagulant function of the tested drugs (see Fig. 3). Furthermore, since this plasma contains no FV, polyP will be unable to promote any further FVa generation; we therefore hypothesized that polyP should be without effect on clotting times. Indeed, we found that adding 100 μM polyP to such plasma mixtures failed to antagonize the anticoagulant effects of any of the four drugs tested (Fig. 4). These results argue that the polyP antagonizes the anticoagulant function of these four drugs solely by its ability to promote FV activation.

Fig. 4.

In the absence of FV, polyP no longer antagonizes the anticoagulant effect of heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban or rivaroxaban. Anticoagulants were added to FV-deficient plasma containing 1 nM Factor Va, after which clotting was initiated by dilute thromboplastin. Anticoagulants were: (U) 0.4 U mL−1 unfractionated heparin; (E) 30 μg mL−1 enoxaparin; (A) 2 μg mL−1 argatroban; (R) 0.7 μg mL−1 rivaroxaban; or (N) no additive. Wells without added polyP (open bars) were compared to those containing 100 μM polyP (filled bars). Data are mean ± standard error (n = 5).

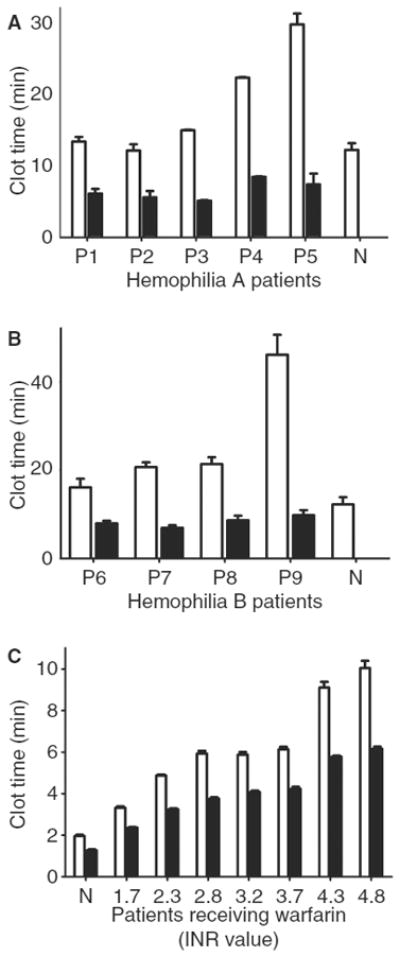

PolyP shortens the clotting times of hemophilia plasmas and plasmas from warfarin patients

We evaluated the ability of polyP to reverse the prolonged clotting times of hemophilia A and B plasmas (in clotting assays using dilute thromboplastin). PolyP decreased the clotting time of plasmas from five patients with severe hemophilia A and four patients with severe hemophilia B (Fig. 5A,B). In the presence of polyP, plasmas from these patients clotted more rapidly than did normal plasma without polyP.

Fig. 5.

PolyP shortens the clotting time of hemophilia plasmas and plasmas from warfarin patients. Clotting tests were performed with plasmas from (A) 5 different patients with hemophilia A; (B) 4 different patients with hemophilia B; or (C) 7 different patients receiving warfarin therapy (with the indicated INR values). “N” indicates data from pooled normal plasma. Clotting reactions without added polyP (open bars) were compared to those containing 100 μM polyP (filled bars). Data are mean ± standard error (n = 5).

We also evaluated the ability of polyP to reverse the prolonged clotting times of plasma from warfarin patients. Adding polyP shortened, but did not completely normalize, the clotting time for all patient samples, irrespective on the patients’ INR (Fig. 5C).

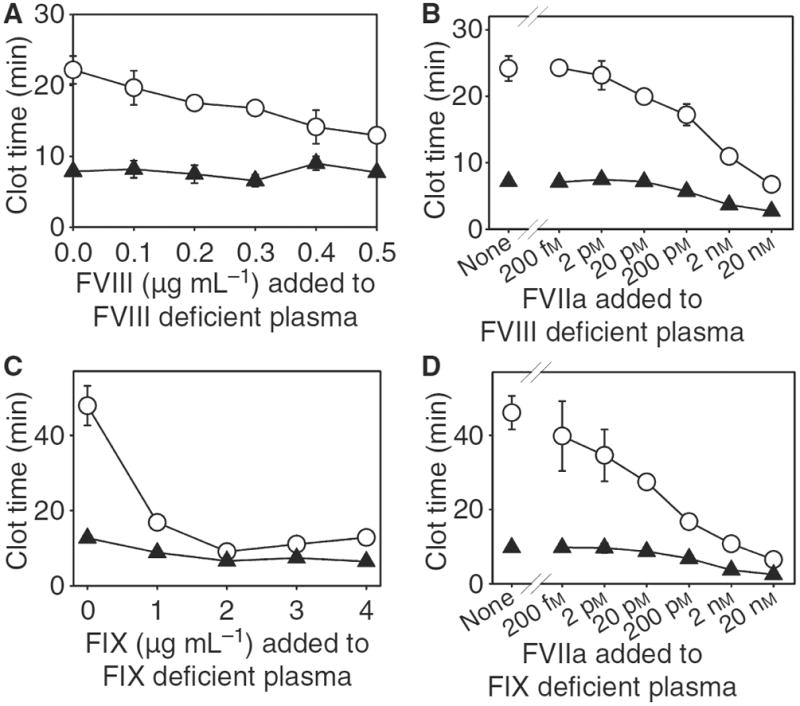

We further evaluated the potential effectiveness of polyP as a procoagulant agent for hemophilia by comparing the ability of polyP to shorten the clotting times of hemophilia A or B plasmas to which the missing clotting factor was replenished, or to which rFVIIa was added. Adding 100 μM polyP shortened the plasma clotting times in both FVIII deficiency and FIX deficiency to a greater degree than did replacement of the missing clotting factor (Fig. 6A,C). PolyP also shortened the plasma clotting time to an extent similar to that observed when rFVIIa was added to the plasmas (Fig. 6B,D). Thus in this clotting assay, the effectiveness of 100 μM polyP was comparable to that of 6 nM rFVIIa in FIX-deficient plasma or 15 nM rFVIIa in FVIII-deficient plasma. We also examined the combination of adding polyP along with FIX, FVIII or rFVIIa and we found that effects of 100 μM polyP were additive to those of rFVIIa (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Ability of polyP to shortening the clotting time of plasma from hemophilia patients compared with the effect of supplementing the plasmas with the missing clotting factor or rFVIIa. (A) FVIII or (B) rFVIIa was added to plasma from a hemophilia A patient. (C) FIX or (D) rFVIIa was added to plasma from a hemophilia B patient. Clotting was initiated by dilute thromboplastin. Clotting reactions without added polyP (○) were compared to those containing 100 μM polyP (▲). Data are mean ± standard error (n = 5). FVIII:1 IU/ml = 0.25 μg/mL. FIX: 1 IU/ml = 5.13 μg/mL. For comparison, the mean clotting time for pooled normal plasma was 12.2 min.

Discussion

We have now demonstrated that polyP of the size secreted by human platelets partially or completely reversed the anticoagulant effects of four drugs (unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, argatroban, and rivaroxaban). PolyP did this in spite of the differing modes of action of these drugs, and was particularly effective at reversing anticoagulation due to the direct FXa inhibitor, rivaroxaban.

Thromboelastography confirmed that polyP shortened the time to initial clot formation (CT) in whole blood. The anticoagulant effects of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, or argatroban were not entirely reversed by polyP, whereas adding polyP to blood containing rivaroxaban resulted in a procoagulant effect similar to that observed in the absence of the anticoagulant drug. Since the majority of thrombin is generated after initial clot formation, thromboelastography provided additional information regarding the dynamics of clot formation as it occurred after initial clot detection in plasma clotting assays. Despite the lack of normalization of CT by polyP in blood anticoagulated with heparin, enoxaparin, and argatroban, polyP completely reversed the effects of these anticoagulants on the parameters associated with the dynamics of clot formation that indicate propagation and rigidity (CFT, α angle, and MCF).

Interestingly, when these anticoagulant drugs were added to plasma in which all the FV was already in the active state (FVa), polyP failed to reverse the anticoagulant effects of any of the drugs. Furthermore, simply adding FVa to normal plasma antagonized the anticoagulant effect of these drugs to a level similar to that observed with polyP. Taken together, these results argue that polyP abrogates anticoagulant drug activity by enhancing FVa generation [16]. The ability of polyP to antagonize argatroban was of particular interest, since a direct thrombin inhibitor should act only downstream of the prothrombinase complex. On the other hand, an important function of thrombin is the feedback activation of FV to FVa, a process that should be slowed by argatroban (thus delaying clotting). But we previously showed that polyP accelerates the rate of FV activation by both FXa and thrombin [16]. We therefore propose that polyP works to reverse argatroban’s anticoagulant function by accelerating FV activation.

We also found that polyP shortened the clotting of hemophilic plasmas or plasmas from patients receiving warfarin, although it only partially normalized the clotting times of the latter group. PolyP may have incompletely reversed the effects of vitamin K antagonists because enhanced FVa generation was unable to fully augment the assembly of the prothrombinase complex when undercarboxylated coagulation factors were present. In contrast, tissue factor-triggered coagulation was completely normalized by polyP when either FVIII or FIX were deficient, and in fact polyP was as effective at normalizing the clotting time of hemophilic plasmas as was replacing the missing clotting factor or adding rFVIIa, both of which are accepted in vivo therapies for managing hemorrhage in hemophilia patients. It is of particular interest that the procoagulant effect of polyP was additive to that of rFVIIa. Because polyP acts at a later level in coagulation than does FVIIa, the two treatments may be complementary. As the costs associated with treating bleeding episodes in hemophilia with rFVIIa are so large, even a minor reduction in rFVIIa dose could profoundly reduce the cost of managing these patients.

Recently, rFVIIa has been proposed as a “universal procoagulant” with the potential to reverse the anticoagulant activity of a variety of drugs [1,3,21]. In studies in vitro or ex vivo, rFVIIa partially or completely reversed the anticoagulant effects of unfractionated heparin [9] enoxaparin [9], fondaparinux [9,10], warfarin [22], argatroban [9], or bivalirudin [9]. In vivo data regarding reversal of anticoagulation with rFVIIa is limited, although rFVIIa antagonized the anticoagulant effects of fondaparinux [11,23] and idraparinux [24] in normal healthy volunteers. In anecdotal reports and case series, rFVIIa normalized in vitro clotting and improved or prevented bleeding in patients receiving unfractionated heparin [25], low molecular weight heparin [5,25], vitamin-K antagonists [7,8,25–29] or lepirudin [6]. Despite frequent anecdotal reports of using rFVIIa to reverse anticoagulant-induced hemorrhage, the drug is not currently approved for this indication. Controlled studies evaluating its safety and effectiveness in comparison to other therapies are lacking, and appropriate dose protocols have yet to be clearly determined [3]. Furthermore, thromboembolic adverse events following administration of rFVIIa have been described [12], the majority of which are associated with off-label use. Lastly, rFVIIa is expensive.

PolyP added to plasma has a half-life of approximately 1.5 hours, apparently being degraded by plasma phosphatases [16]. Few data are available for polyP metabolism and clearance in vivo, although 99mTc-labeled polyP was reported to distribute to bone [30]. Therapeutic use of polyP for its effects on coagulation may possibly necessitate continuous or multiple infusions, but polyP is inexpensive and may therefore represent a significant cost savings over other available therapies.

The present studies demonstrate that polyP partially or completely reversed the effects of a variety of anticoagulant drugs in vitro, and shortened the clotting time of plasmas deficient in FVIII or FIX. These findings suggest that polyP might be useful for treatment of bleeding episodes in patients with compromised hemostatic systems, although in vivo tests would clearly be needed to establish this.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bayer for providing Kogenate and Rivaroxaban, and Diagnostica Stago-US for generously loaning the ROTEM system. This work was supported by grants R01 HL47014 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the NIH, and 06-2328 from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The authors are coinventors on patent applications on the use of polyphosphate to modulate blood clotting.

References

- 1.Kessler CM. Current and future challenges of antithrombotic agents and anticoagulants: Strategies for reversal of hemorrhagic complications. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:44–50. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulman S, Bijsterveld NR. Anticoagulants and their reversal. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoots WK. Challenges in the therapeutic use of a “so-called” universal hemostatic agent: recombinant factor VIIa. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006;2006:426–31. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathew P. Current opinion on inhibitor treatment options. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:S8–13. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firozvi K, Deveras RA, Kessler CM. Reversal of low-molecular-weight heparin-induced bleeding in patients with pre-existing hypercoagulable states with human recombinant activated factor VII concentrate. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:582–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh JJ, Akers WS, Lewis D, Ramaiah C, Flynn JD. Recombinant factor VIIa for refractory bleeding after cardiac surgery secondary to anticoagulation with the direct thrombin inhibitor lepirudin. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:569–77. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brody DL, Aiyagari V, Shackleford AM, Diringer MN. Use of recombinant factor VIIa in patients with warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2:263–7. doi: 10.1385/NCC:2:3:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J, Hanigan WC, Tarantino M, Wang J. The use of recombinant activated factor VII to reverse warfarin-induced anticoagulation in patients with hemorrhages in the central nervous system: preliminary findings. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:737–40. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.4.0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young G, Yonekawa KE, Nakagawa PA, Blain RC, Lovejoy AE, Nugent DJ. Recombinant activated factor VII effectively reverses the anticoagulant effects of heparin, enoxaparin, fondaparinux, argatroban, and bivalirudin ex vivo as measured using thromboelastography. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18:547–53. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328201c9a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerotziafas GT, Depasse F, Chakroun T, Samama MM, Elalamy I. Recombinant factor VIIa partially reverses the inhibitory effect of fondaparinux on thrombin generation after tissue factor activation in platelet rich plasma and whole blood. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:531–7. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lisman T, Bijsterveld NR, Adelmeijer J, Meijers JC, Levi M, Nieuwenhuis HK, De Groot PG. Recombinant factor VIIa reverses the in vitro and ex vivo anticoagulant and profibrinolytic effects of fondaparinux. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:2368–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell KA, Wood JJ, Wise RP, Lozier JN, Braun MM. Thromboembolic adverse events after use of recombinant human coagulation factor VIIa. JAMA. 2006;295:293–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aledort LM. Comparative thrombotic event incidence after infusion of recombinant factor VIIa versus factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1700–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz FA, Lea CR, Oldfield E, Docampo R. Human platelet dense granules contain polyphosphate and are similar to acidocalcisomes of bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44250–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornberg A, Rao NN, Ault-Riche D. Inorganic polyphosphate: a molecule of many functions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:89–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SA, Mutch NJ, Baskar D, Rohloff P, Docampo R, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate modulates blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:903–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507195103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate enhances fibrin clot structure. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145755. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsh J, Raschke R. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:188S–203S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.188S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swan SK, Hursting MJ. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of argatroban: effects of age, gender, and hepatic or renal dysfunction. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:318–29. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.4.318.34881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueck W, Eriksson BI, Bauer KA, Borris L, Dahl OE, Fisher WD, Gent M, Haas S, Huisman MV, Käkkar AK, Kalebo P, Kwong LM, Misselwitz F, Turpie AG. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor--in patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:203–16. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi M, Bijsterveld NR, Keller TT. Recombinant factor VIIa as an antidote for anticoagulant treatment. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:65–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka KA, Szlam F, Dickneite G, Levy JH. Effects of prothrombin complex concentrate and recombinant activated factor VII on vitamin K antagonist induced anticoagulation. Thromb Res. 2008;122:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bijsterveld NR, Moons AH, Boekholdt SM, van Aken BE, Fennema H, Peters RJ, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Ability of recombinant factor VIIa to reverse the anticoagulant effect of the pentasaccharide fondaparinux in healthy volunteers. Circulation. 2002;106:2550–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038501.87442.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bijsterveld NR, Vink R, van Aken BE, Fennema H, Peters RJ, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Recombinant factor VIIa reverses the anticoagulant effect of the long-acting pentasaccharide idraparinux in healthy volunteers. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:653–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2003.04811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingerslev J, Vanek T, Culic S. Use of recombinant factor VIIa for emergency reversal of anticoagulation. J Postgrad Med. 2007;53:17–22. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.30322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deveras RA, Kessler CM. Reversal of warfarin-induced excessive anticoagulation with recombinant human factor VIIa concentrate. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:884–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorensen B, Johansen P, Nielsen GL, Sorensen JC, Ingerslev J. Reversal of the International Normalized Ratio with recombinant activated factor VII in central nervous system bleeding during warfarin thromboprophylaxis: clinical and biochemical aspects. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003;14:469–77. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200307000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dager WE, King JH, Regalia RC, Williamson D, Gosselin RC, White RH, Tharratt RS, Albertson TE. Reversal of elevated international normalized ratios and bleeding with low-dose recombinant activated factor VII in patients receiving warfarin. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1091–8. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.8.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roitberg B, Emechebe-Kennedy O, min-Hanjani S, Mucksavage J, Tesoro E. Human recombinant factor VII for emergency reversal of coagulopathy in neurosurgical patients: a retrospective comparative study. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:832–6. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000180816.80626.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnamurthy GT, Thomas PB, Tubis M, Endow JS, Pritchard JH, Blahd WH. Comparison of 99mTc-polyphosphate and 18F. I. Kinetics. J Nucl Med. 1974;15:832–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]