Abstract

Systemic delivery of oligonucleotides (ODN) to the central nervous system is needed for development of therapeutic and diagnostic modalities for treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Macromolecules injected in blood are poorly transported across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and rapidly cleared from circulation. In this work we propose a novel system for ODN delivery to the brain based on nanoscale network of cross-linked poly(ethylene glycol) and polyethylenimine (“nanogel”). The methods of synthesis of nanogel and its modification with specific targeting molecules are described. Nanogels can bind and encapsulate spontaneously negatively charged ODN, resulting in formation of stable aqueous dispersion of polyelectrolyte complex with particle sizes less than 100 nm. Using polarized monolayers of bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells as an in vitro model this study demonstrates that ODN incorporated in nanogel formulations can be effectively transported across the BBB. The transport efficacy is further increased when the surface of the nanogel is modified with transferrin or insulin. Importantly the ODN is transported across the brain microvessel cells through the transcellular pathway; after transport, ODN remains mostly incorporated in the nanogel and ODN displays little degradation compared to the free ODN. Using mouse model for biodistribution studies in vivo, this work demonstrated that as a result of incorporation into nanogel 1 h after intravenous injection the accumulation of a phosphorothioate ODN in the brain increases by over 15 fold while in liver and spleen decreases by 2-fold compared to the free ODN. Overall, this study suggests that nanogel is a promising system for delivery of ODN to the brain.

INTRODUCTION

Oligonucleotides (ODN) have attracted significant interest as potential diagnostic and therapeutic agents for diseases that currently have no cure. This includes cancer, neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease), and lethal viral infections (1–7). However, the use of ODN in the body is hindered by the lack of stability of ODN against enzymatic degradation as well as rapid clearance of ODN through renal excretion. Furthermore, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) severely restricts the entry of ODN to the brain from the periphery, which represents a major obstacle for the use of ODN for diagnostics and therapy of disorders of central nervous system (CNS). The need to improve the pharmacological performance of ODN resulted in development of drug delivery systems for ODN (8–12). In particular, studies involving nanoparticles demonstrated promise in enhancing delivery of ODN to the brain (13). Several major features of nanoparticles make them especially useful for this application. First, they represent an injectable drug delivery system with particle size ca. 100 nm or less. Such particles can easily enter brain capillaries and reach the surface of the brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) forming the BBB. Second, the surface of the nanoparticles, for example, those prepared from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) or poly(butylcyanoacry-late), can be modified by poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or PEG-containing surfactants. This can prolong the circulation of the nanoparticles in the blood and enhance exposure of the BBB to the modified nanoparticles. Third, the nanoparticles can be further modified with specific targeting molecules that enhance binding of the nanoparticles with the surface receptors of the BMVEC and promote transport of the nanoparticles across the BBB. In particular, Pardridge and collaborators proposed to use for this purpose insulin and transferrin receptors (14–16). Importantly, the small size of nanoparticles may allow for their receptor-mediated transcytosis in BBB without violating the integrity of the tight junctions of BMVEC, which are impermeable to macromolecules. Various therapeutic agents including ODN, proteins, and peptides can be encapsulated in the nanoparticles. Following the delivery of the nanoparticles to the disease site in the body, the polymer matrix can slowly degrade resulting in sustained release of the encapsulated therapeutic agents. Thus, the nanoparticles have a dual capacity as drug carriers and sustained drug release systems.

However, the currently used nanoparticles have substantial shortcomings including relatively low drug loading capacities and rather complicated preparation and drug formulation procedures. These procedures require exposure to organic solvents and energy input (e.g. sonication), which often result in inactivation of therapeutic macromolecules. One alternative approach, proposed by our group, is to use, as drug carriers, flexible hydrophilic polymer gels of nanoscale size, termed nanogels (NanoGel) (17–20). Nanogels can be synthesized in the absence of the drug, equilibrated (swollen) in water, and then loaded with the drug. Drug loading occurs spontaneously and results in decrease of the solvent volume, which is followed by the gel collapse and formation of dense nanoscale particles. We have previously described cationic nanogels consisting of covalently cross-linked PEG and polyethylenimine (PEI) chains, nano-PEG-cross-PEI (18, 20). Such nanogels can bind and encapsulate spontaneously, through ionic interactions, any type of negatively charged ODN, including antisense ODN, ribozymes, siRNAs, etc. Although the charge neutralization results in condensation of polycation and ODN chains, the loaded nanogels remain stable in aqueous dispersion due to the effect of nonionic PEG chains. A key advantage of nanogels is that they allow for high “payloads” of macromolecules, up to 50 wt %, which usually cannot be achieved with conventional nanoparticles. Nanogels are transported in the cells and can release functionally active antisense ODN, which was shown to produce specific effects on gene expression in the cells (18). Furthermore, nanogels can carry ODN across cellular barriers, such as monolayers of human intestine epithelial cells and protect ODN from degradation within these cells (18). Previous studies also demonstrated that as a result of modification of nanogels with targeting moieties, such as insulin or transferrin, the modified nanogels undergo receptor-mediated transport in the cells (18, 20).

The objective of the present work is to evaluate whether the nano-PEG-cross-PEI nanogels can be useful for delivery of ODN to the brain. We describe the synthesis and characterization of nano-PEG-cross-PEI nanogels, modified with insulin and transferrin. We use polarized monolayers of bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells (BBMEC) as an in vitro model of the BBB in the transport studies as well as a mouse model for initial studies of the in vivo biodistribution of nanogels and encapsulated ODN. The results suggest successful delivery of nanogel-encapsulated ODN from the apical to basolateral side of the BBMEC monolayers. Furthermore, the data suggest that nanogel protects ODN from enzymatic degradation in the cells. Finally, the in vivo biodistribution study suggests that following intravenous (iv) administration of nanogel-formulated ODN in mice, substantial amounts of nanogel and ODN accumulate in the brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

PEG (MW 8000), 3H-succinimidyl propionate, 96 mCi/mmol, and 3H-mannitol, 50 mCi/mmol, were purchased from Moravek Radiochemicals (Brea, CA) and DuPont Corp. (Boston, MA), respectively. All other reagents and resins for chromatography were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St-Louis, MO). The commercial branched PEI (MW 25 000) was fractionated by gel permeation chromatography on the Sepharose CL-2B column (2.5 × 75 cm) in 0.2 M sodium chloride, 0.025% aqueous ammonia, at elution rate 1 mL min−1 with refractive index detection. Polymer fractions containing amines were identified by blue color development following treatment of dried aliquots with a 2% solution of ninhydrin in ethanol. The high molecular mass (>ca. 50 000) and low molecular mass (<ca. 5000) fractions were discarded and the main fraction, ca. 50 wt % of the initial sample, was collected and used for the nanogel synthesis. The carbonyldiimidazole-activated PEG was synthesized from commercial PEG (8000), which was first dried in vacuo at 50 °C overnight and then dissolved in 50 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile and reacted with excess of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole under argon atmosphere for 4 h at 40 °C. The product was quantitatively precipitated from anhydrous ether (1 L), collected by centrifugation at 2000g, and dried in vacuo. Antisense ODN, 5′GTCAAGCCAATTTGAATAGC, targeting the MDR1 gene with the 3′-amino (C3) linker (Glen Research, CA) was synthesized using phosphorothioate chemistry on a 1 micromolar scale (UNMC Oligonucleotide Core Facility, Omaha, NE). ODN was used without any additional purification except for ODN precipitation from 0.3 M sodium chloride solution in 2-propanol.

Synthesis of Nano-PEG-cross-PEI

Nanogel was synthesized using the emulsification-solvent evaporation method with modifications (18). The solution of carbonyldiimidazole-activated PEG (3 g) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added dropwise to the solution of PEI (1 g) in water (180 mL) upon sonication in a Bransonic ultrasonic bath with ice-cold water. Following complete mixing, the resulting emulsion was sonicated for 20 or 30 min at 40 MHz. After that dichloromethane was quickly removed from the resulting milky solution in vacuo using a Buchi rotary evaporator with water bath set at 30 °C until the solution became clear. After that the solution was stirred for a 24 h period at 25 °C, filtered to separate large debris, and then neutralized by hydrochloric acid. The polymeric product was dialyzed through a SpectraPore membrane with the cutoff 25 000 Da against 0.025% aqueous ammonia for 2 days, concentrated in vacuo, and redissolved in 60 mL of 20% ethanol. Nanogel particles were fractionated by gel permeation chromatography on the Sepharose CL-2B column (2.5 × 75 cm) in 20% ethanol at an elution rate 1 mL min−1. PEG-containing fractions were determined by the colorimetric method (21), and the fractions containing amines (PEI) were analyzed using the qualitative ninhydrin reaction. Nanogel fractions, containing both PEG and PEI, were collected and lyophilized. About 65–70% of polymeric material was recovered in the form of nanogel.

Nanogel Characterization

For analysis of PEG/PEI ratio in nanogel preparations, 5% solutions of dried nano-PEG-cross-PEI samples in D2O were prepared and filtered. 1H NMR spectra (with integration) were measured in the range 0–6 ppm at ambient temperature using the Varian 300 MHz spectrometer. Elemental analysis (MH-W Laboratories, Phoenix, AZ) was used to measure total nitrogen content in nanogel preparations. The amount of ionizable groups in nanogel was determined by potentiometric titration of 1% suspension in 0.15 M solution of sodium chloride with hydrochloric acid. Before analysis, nanogel samples were dialyzed in 2% aqueous ammonia for 24 h and then lyophilized.

Biotin-Conjugated Nanogel

Nanogel (0.2 g) suspension in 2 mL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9, was treated with 1% solution of biotin p-nitrophenyl ester (0.6 mL) in dimethylformamide (DMF) overnight at 25 °C. Biotinylated nanogel was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration on the Sephadex G-25 column (1 × 20 cm) in 20% ethanol at elution rate 0.5 mL min−1, and fractions containing the product were lyophilized. Content of the covalently attached biotin was determined using 2-anilinonaphthalene-6-sulfonic acid (ANS)-avidin titration assay (22).

Rhodamine-Labeled Nanogel

Nanogel (0.2 g) suspension in 2 mL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9, was treated with 1% solution of rhodamine isothiocyanate (RITC) (0.2 mL) in DMF overnight at 25 °C. The red fraction of RITC-labeled nanogel was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration on the Sephadex G-25 column (1 × 20 cm) in 20% ethanol at elution rate 0.5 mL min−1, and fractions containing the product were lyophilized. Fluorescent spectral characteristics of the RITC-labeled nano-PEG-cross-PEI (λex 549 nm and λem 577 nm) were measured in the phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using a Shimadzu RF5000 spectrofluorimeter.

Fluorescein-Labeled ODN

Solution of 3′-amino-ODN (10 nmol) in 0.2 mL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.0, was treated with 0.8 mL of 1% solution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) in DMF overnight at 25 °C. The green fraction of FITC-labeled OND was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration on the Sephadex G-25 column (1 × 20 cm) in 20% ethanol at elution rate 0.5 mL min−1, and fractions containing the product were lyophilized. Fluorescent spectral characteristics of the FITC-labeled ODN (λex 489 nm and λem 513 nm) were measured in the phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using a Shimadzu RF5000 spectrofluorimeter.

Tritium-Labeled ODN

ODN bearing a 3′-primary amino group were labeled according to ref 23. The procedure for introduction of tritium label consists of the following steps. First, ODN (10 nmol) was precipitated in the form of cetyltrimethylammonium (CTA) salt, which is soluble in organic solvents, dried in vacuo, and redissolved in DMF. This solution was mixed with 3H-succinimidyl propionate (40 µCi, specific activity 96 Ci/ mmol), dissolved in toluene-ethyl acetate, and left to stand overnight at 25 °C. After the volatile organic solvents were removed in the flow of nitrogen, 0.04 mL of 50 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate solution was added to convert labeled ODN from CTAB-salt into sodium salt. Finally, tritium-labeled ODN was precipitated twice from sodium acetate solution in ethanol, washed by 70% ethanol, and dried in vacuo. Radioactivity of the precipitate and solutions was analyzed using Beckman LS6000 IC Liquid Scintillation counter. ODN concentration was determined using UV measurements. Efficiency of the labeling procedure was about 75%, and the specific activity of ODN was 3.3 Ci/mmol.

Preparation of Tritium-Labeled Nanogel

Nanogel (0.2 g) suspension in 2 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile containing 2% (v/v) of triethylamine was treated with a solution of 3H-succinimidyl propionate (150 µCi) in toluene–ethyl acetate mixture overnight at 25 °C. Organic solvents were removed in the flow of nitrogen, and tritium-labeled nanogel was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration on the Sephadex G-25 column (1 × 20 cm) in 20% ethanol at elution rate 0.5 mL min−1. Radioactivity of the fractions was analyzed using Beckman LS6000 IC Liquid Scintillation counter. Fractions containing nanogel were collected and lyophilized. Specific activity of the tritium-labeled nanogel measured in 0.01% aqueous solution was equal to 20 µCi/ mg. Efficiency of the labeling procedure was about 80%.

Preparation of Nanogel–ODN Complexes

Nanogel dispersion (1% w/v) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was sonicated for 10–15 min at 25 °C and then filtered through the 0.45 µm filter. Total nitrogen (N) concentration was 66 mM. ODN solution (0.05 mM) in PBS (concentration of phosphate (P) groups 0.95 mM) was used as a stock solution for preparation of the complexes. For example, to prepare complexes containing 5 µM of ODN at N/P ratio 8, 0.2 mL of ODN solution was added dropwise upon stirring to the suspension of biotinylated nanogel (0.023 mL) in 1.78 mL of assay buffer (10 mM HEPES, 122 mM sodium chloride, 25 mM sodium bicarbonate, 10 mM glucose, 3 mM potassium chloride, 1.4 mM calcium chloride, 1.2 mM magnesium sulfate, 0.4 mM dibasic potassium phosphate). The resulting slightly opalescent solution was stirred for 1 h at 25 °C and then filtered through the sterile 0.22 µm filter. This solution could be stored at 4 °C at least for a week without any sign of precipitation. To prepare vectorized carriers, the equal volumes (0.1 mL) of white egg avidin (0.1 mM) and biotinylated bovine insulin (0.1 mM) or biotinylated bovine transferrin (0.1 mM) solutions in PBS were mixed in 1.8 mL of assay buffer upon stirring. After 30 min, this solution was supplemented with 2 mL of the preformed nanogel-ODN dispersion. The final solutions (4 mL) were incubated for at least 2 h at 25 °C, filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter, and used in further studies. Freshly prepared insulin and transferrin modified nanogel-ODN complexes were stored without freezing at 4 °C and used next day in the cell transport experiments.

Particle Sizing and ξ-Potential Measurements

The electrophoretic mobility (EPM) measurements of the nanogel-ODN complexes were performed in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at various N/P ratios, 25 °C with electrical field strength of 15–18 V cm−1 by using ‘ZetaPlus’ Zeta Potential Analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) with 15 mV solid-state laser operated at a laser wavelength of 635 nm. The ξ-potential of the particles was calculated from the EPM values using manufacturer’s software. Effective hydrodynamic diameter of free and the ODN-loaded nanogel particles was measured by photon correlation spectroscopy using the same instrument equipped with the Multi-Angle Option at the angle of 90° and ambient temperature. The instrument was tested by standard suspension of polystyrol latex particles. All solutions were prepared in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and filtered through 0.45 µm filter.

To study particle size in the presence of bovine serum albumin (BSA), ODN-nanogel complexes were prepared in 2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated 30 min at room temperature, mixed with 0.2 mL of 4% BSA solution, and incubated another 30 or 90 min. Samples were filtered through 0.45 µm filter before measurements.

Cell Culture

BBMEC were isolated according to the method (24). BBMEC monolayers for transport studies were grown on the fibronectin- and collagen-coated Transwell polycarbonate membrane inserts (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in MEM:F12 culture medium supplemented with 10% horse serum, heparin sulfate (100 µg/mL), amphotericin B (2.5 µg/mL), and gentamicin (50 µg mL−1) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. The isolated cells formed confluent monolayers following 14 days of incubation. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values were recorded as indexes of cell viability and monolayer integrity. Under basal conditions, mean resistance was 135 ± 13 Ω/cm2.

Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity of free and ODN-loaded nanogel was assessed by the measurement of IC50 value in a standard 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (25). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were seeded with 5000 cells/well and allowed to reattach overnight. Dilutions of the nanogel-ODN dispersion (100 µL) in assay buffer were incubated with the cells for 2 h at 37 °C. Samples were washed three times with 100 µL of Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) and replaced with fresh culture medium (200 µL) daily. After incubation period of 72 h, 25 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. Medium and indicator dye were then removed and the cells lysed with 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate in 50% aqueous dimethylformamide (100 µL) overnight at 37 °C. Absorption was measured at 550 nm in Microkinetics reader BT2000, and obtained values were expressed as a percentage of the values obtained for control cells to which no carriers were added. All measurements were repeated eight times.

Transport Experiments

Transport studies were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, polycarbonate membrane inserts with confluent BBMEC mono-layers were placed in thermostated Side-By-Side diffusion chambers (Crown BioScientific, Inc.) maintained at 37 °C. Cell monolayers were preincubated for 30 min with the assay buffer added into both donor and receiver chambers. Following the preincubation period, fresh assay buffer was added to the receiver chamber and the buffer in the donor chamber was replaced with nanogel–ODN dispersions containing a paracellular marker for cell monolayers, 3H-labeled mannitol. All experiments were conducted in triplicates. At different time points, solutions in the receiver container were removed and analyzed. Phosphorothioate ODN and nanogel–ODN complexes were quantified by the anion exchange HPLC using Nucleopac PA-100 guard column (0.4 × 5 cm), and gradient elution with buffer A (90% 25 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 10% acetonitrile) and buffer B (90% 2M ammonium chloride in 25 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 10% acetonitrile), at 2 mL min−1 and 65 °C with UV detection at 270 nm (27). To assess extent of dissociation of the nanogel-ODN complex following the transport across BBMEC monolayer, the samples in receiver chamber were concentrated using Ultrafree-15 Centrifugal Filter Device (5K NMWL, Millipore, Bedford, MA), and then analyzed by the gel permeation HPLC on SigmaChrom GFC-1300 column (0.7 × 30 cm) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, at 0.5 mL min−1 and 25 °C with UV detection at 270 nm.

Apparent permeability (Papp) of the cells with respect to ODN and nanogel–ODN complexes was calculated as follows:

where V × dC/dt is the steady-state rate of appearance of ODN at the basolateral side of the monolayers, Co is the initial ODN concentration at the apical side, and A is the surface area of the membrane.

Confocal Microscopy

Cellular accumulation localization of FITC-labeled ODN, RITC-labeled nanogel, and their complexes was examined using laser confocal fluorescent microscopy. In these studies, BBMEC were grown on chamber slides (Fisher Scientific) and incubated with 0.5 mL of 5 µM ODN or ODN-loaded nanogel for 2 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and scanned with a confocal fluorescence microscopic system ACAS-570 (Meridian Instruments, Okimos, MI) with argon ion laser (excitation wavelength, 488 nm) and corresponding filter set. Digital images were obtained using the CCD camera (Photometrics) and Adobe Photoshop software.

Biodistribution in Mice

All experiments were performed with female FVB wild type mice between 12 and 14 weeks of age (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, DE) using procedure analogous to that previously described (28). In the initial studies, the nanogel–ODN complex was injected daily in the tail vein to assess tolerated doses. The concentration of the complexes in injected solutions (200 µL) increased daily from 0.5 to 2.5% (w/v) with 0.5% increment. In following experiments, 100 µL of nanogel-ODN (50 µM) complex were injected in the tail vein of FVB mice. In this study we used radioactively labeled compounds, 3H-nanogel or 3HODN. There were four animals in each treatment group. Animals were sacrificed 1 h after injection, and their organs (brain, liver, spleen, and lung) were taken and washed with PBS. Blood and organs were weighted, soaked in 4% BSA solution (2 mL g−1 of organ), and homogenized. Samples (200 µL) of organ homogenates or 100 µL of blood plasma were added into 4 mL of scintillator solution, and the amount of 3H-nanogel or 3HODN was measured using Beckman LS6000 IC liquid scintillation counter. Concentrations of labeled compound in the plasma and brain were expressed as cpm/100 µL of plasma or cpm/200 µL. These concentrations were used to calculate brain/plasma ratios.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Characterization of Nanogel

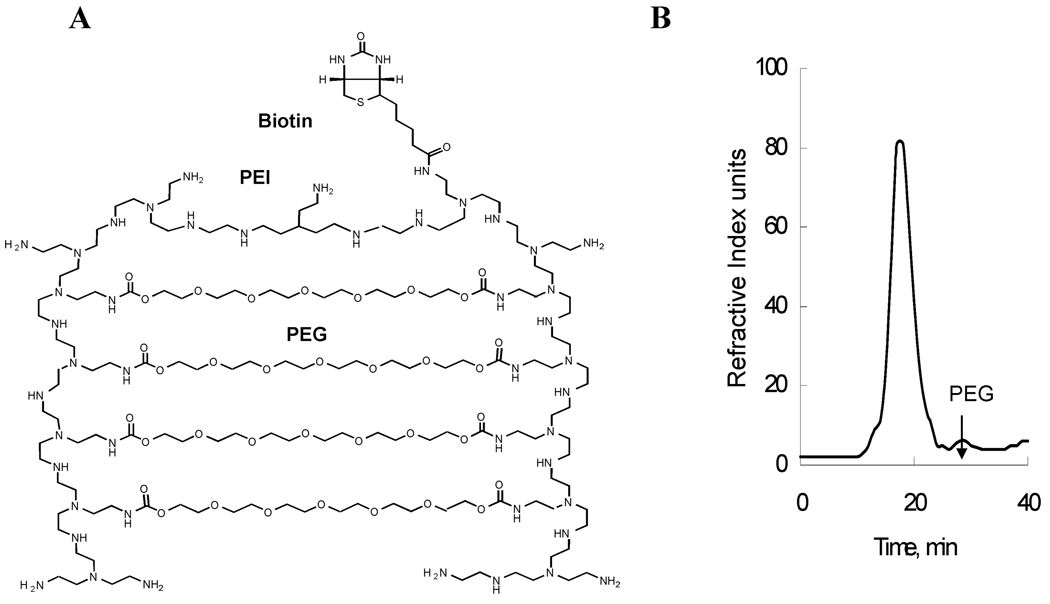

Figure 1A presents a schematic structure of nano-PEG-cross-PEI nanogel synthesized in this work. It was prepared by cross-linking the branched PEI (25 000) with an amino reactive PEG linker (8000), using a modified procedure (18). According to this procedure, the solution of the activated PEG in dichloromethane was emulsified in the aqueous solution of PEI by sonication. After completion of the cross-linking reaction, the organic solvent was removed, and nanogel was allowed to maturate in aqueous medium. The maturating stage is important to allow for the completion of the cross-linking reaction, which at high stages of conversion can be decelerated due to the chain entanglements in the forming polymer networks. Nanogel particles of the desired size range were purified using combination of high-speed centrifugation and gel-permeation chromatography. One important modification in the procedure was that we used higher PEG:PEI ratio, 9:1, compared to that reported in our previous studies, 6:1 (18). The primary reason for this modification was to increase the stability of nanogel formulations in aqueous dispersion due to increase of the amount of the hydrophilic PEG chains.

Figure 1.

Shematic representing biotinylated nanogel network (A), and the chromatographic profile of GP-HPLC with refractive index (RI) detection of a biotinylated nanogel sample (B). See Material and Methods for chromatography conditions.

We also varied the time of sonication of the dichloromethane–water emulsion during the synthesis of the nanogel and found that this strongly affected the properties of the product, in particular, the particle size. Two major batches of nanogel were obtained following crude fractionation by gel-permeation chromatography: the first one having the particle size 240 nm (sonication time 20 min, “batch 1”) and the second one having the particle size 150 nm (sonication time 30 min, “batch 2”). Interestingly, longer sonication time, e.g. 60 min, resulted in formation of macroscopic gel fragments that could not be used in these studies.

The properties of the nanogel batches are listed in Table 1. Generally, 55–70% of the total weight of reacting polymers was recovered in the form of nanogel particles. The absence of the unreacted polymers was verified by gel permeation chromatography with refractive index detection as exemplified in Figure 1B. Contamination of the free PEG (t = 29 min) was less than 5% (the main nanogel peak eluted at t = 17 min). From the NMR data, the proton assignments of nanogel were found to be δ 3.6 ppm (PEG CH2O) and δ 2.5–3.1 ppm (PEI CH2NH). The HPEG/HPEI ratios were equal to 2.7 (batch 1) and 2.6 (batch 2), which corresponded to the PEG:PEI molar ratios 8.7 (batch 1) and 8.6 (batch 2). The elemental analysis showed that the total nitrogen content was practically the same for both batches, 6.6–6.9 µmol/mg. The potentiometric titration with hydrochloric acid suggested that approximately 2/3 of the amino groups in nanogel was protonated at pH 4.5, whereas only 1/3 of the amino groups was protonated at pH 7.5. This is typical of branched PEI samples (29). We estimated that no more than ca. 3% of amino groups in PEI can be involved in the formation of the cross-links with PEG. Most of the experiments described below (unless stated otherwise) were performed with batch 1.

Table 1.

Properties of Nanogel Carriers

| batch | PEG/PEI molar ratio | total nitrogen content, µmol/mg | chargeable amino groups, µmol/mg | nanogel effective diameter, nm, and ζ-potential, mV (in brackets) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unloaded | N/P = 4 | N/P = 8 | N/P = 8a(+BSA) | ||||

| batch 1 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 237 ± 3 (+5) | 76 ± 1 (−0.2) | 94 ± 2 (+2.3) | 54 ± 1 |

| batch 2 | 8.6 | 6.9 | 4.2 | 148 ± 3 (+4.6) | 58 ± 1 (0) | 64 ± 2 (+1.9) | 50 ± 2 |

Particle size measured 30 min after addition of 4% BSA solution in phosphate-buffered saline.

Biotin–Modified Nanogel

Biotin moiety was introduced in the nanogel (batch 1) by modification of amino groups (1.5% of total) with biotin p-nitrophenyl ester. After completion of the reaction, biotin-modified nanogel particles were purified from low-molecular weight products by gel permeation chromatography. The amount of biotin linked to the nanogel was determined by adding the biotin-nanogel to the complex of avidin with a fluorescent probe, ANS. Since biotin has much higher affinity to avidin than ANS, it displaces latter in the complex resulting in the decrease of the probe fluorescence (22). The biotin content was found to be equal to 16.5 µg/mg, which is ca. 67% of the theoretical modification degree (24.5 µg/mg) at used reagent combination. The result shows that substantial part of the biotin moieties linked to the nanogel is available for reacting with avidin.

Fluorescent and Radioactive Labeling of the Nanogel

The rhodamine label was introduced into nanogel particles to follow their transport and localization in BBMEC monolayers. For this purpose, the primary amino groups of nanogel were modified with RITC (1% of total amino group). RITC-labeled nanogel was purified by gel permeation chromatography in the dark resulting in a pink-colored dispersion. Spectral characteristics of the labeled carrier were as follows: λexcitation = 549 nm, λemission = 577 nm (PBS, pH 7.4). Additionally, a tritium-labeled nanogel was obtained for in vivo biodistribution experiments. The primary amino groups of the nanogel were modified using the 3H-succinimidylpropionate in the presence of 2% triethylamine in anhydrous acetonitrile. 3H-Nanogel with specific activity 20 µCi/mg was separated by gel permeation chromatography on Sephadex G-25. Eighty percent of the radioactive label was found to incorporate into macromolecular fraction.

Complexes of Nanogel and ODN

Mixing of ODN and nanogel solutions in PBS, pH 7.4, resulted in immediate formation of the polyelectrolyte complexes, due to the electrostatic binding of the oppositely charged ODN and PEI chains. This was accompanied by the collapse of the gel and decrease in the particle size. To prepare uniform complexes, ODN solution was typically added to the same volume of stirred nanogel suspension. Although the binding of ODN to nanogel was accompanied by neutralization of electrostatic charges, the overall changes in the ζ-potential of nanogel particles were small. The unloaded nanogel equilibrated in aqueous solution was characterized by low positive ζ-potential values, presumably, because of penetration of the small counterions within the nanogel volume (30). Nevertheless, the charge decrease of the nanogel upon binding of ODN was detected. Composition of the polycation-DNA complexes is usually described in terms of N/P ratio, i.e., the ratio of nitrogen (nanogel) to phosphate (ODN) concentrations in the final nanogel and ODN mixture. At N/P = 8 the particles of the complex exhibited small positive charge, while at N/P = 4 these complexes were electroneutral. Table 1 presents the characteristics of unloaded and ODN-loaded nano-PEG-cross-PEI nanogels (batches 1 and 2) measured at two N/P ratios, 4 and 8. Binding of ODN to nanogels resulted in 2.6– to 3.1-times size decrease (N/P = 4), which corresponds to ca. 17 to 30 times decrease in the gel volume. Interestingly, the ODN-loaded nanogel formed more uniform particles (polydispersity index 0.05) compared unloaded nanogel, which had much broader particle size distribution (polydispersity index 0.30). Binding of ODN with the RITC-labeled nanogel resulted in almost 10-fold enhancement of the fluorescence (N/P = 4), presumably due to complexation of the charged amino groups of PEI, which, in the absence of ODN, quench the fluorescence.

Introduction of BSA into the dispersion of nanogel–ODN complex resulted in an additional 20–40% reduction of the detectable particle size. Although no aggregation was observed following the treatment, stability of the complex might be compromised by extended incubation with the protein. Two hours later both samples of nanogel formed particles with very close mean diameter of 34–39 nm, which showed no more changes. These data could be reasonably explained by the phenomenon of opsonization earlier observed for cationic microcarriers in vivo (31)

Modification of ODN-Loaded Nanogel with Insulin and Transferrin

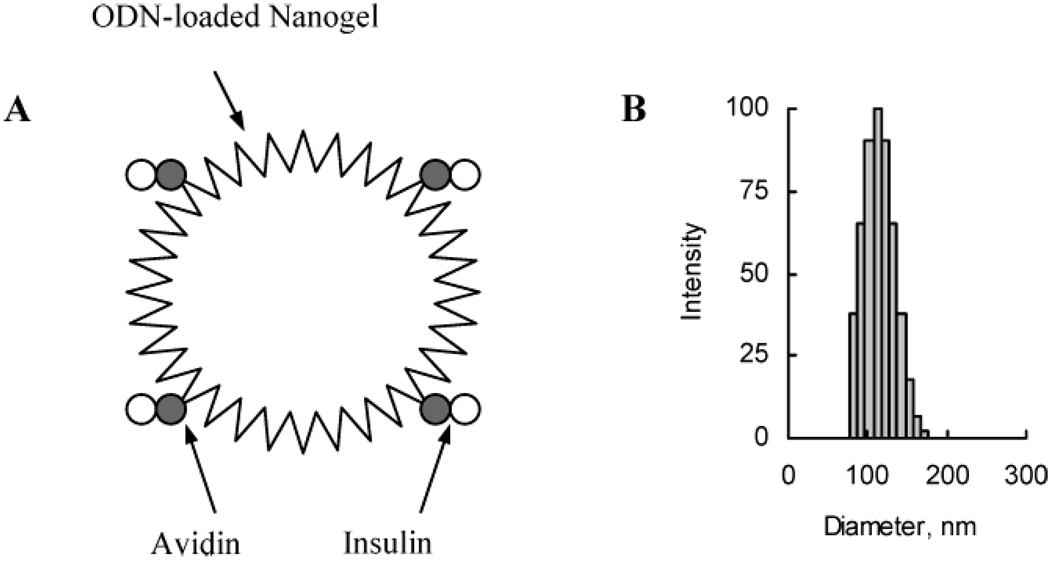

Biotin-modified nanogel was used for further conjugation with transferrin and insulin. First, the biotin-modified nanogel was loaded with ODN at the desired N/P ratio as described above. Second, the ODN-loaded biotin–nanogel complex was reacted with the preformed complex of avidin and biotinylated transferrin or insulin. The schematic showing putative structure of such complex as well as the size distribution diagram of this complex are presented in Figure 2. Importantly, no aggregation of nanogel was observed following the modification procedure, and the particle size increased by only 15% to 20%, e.g., from 94 to 110 nm (N/P = 8). No signs of precipitation have been observed in the formulations for at least 1 day at 4 °C. However, at longer storage periods we observed visible signs of aggregation in these dispersions, most likely induced by interactions of vacant avidin binding sites and excessive biotin residues on vector protein molecules.

Figure 2.

The putative structure (A), and particle size distribution (B) of bovine insulin-vectorized nanogel–ODN complex.

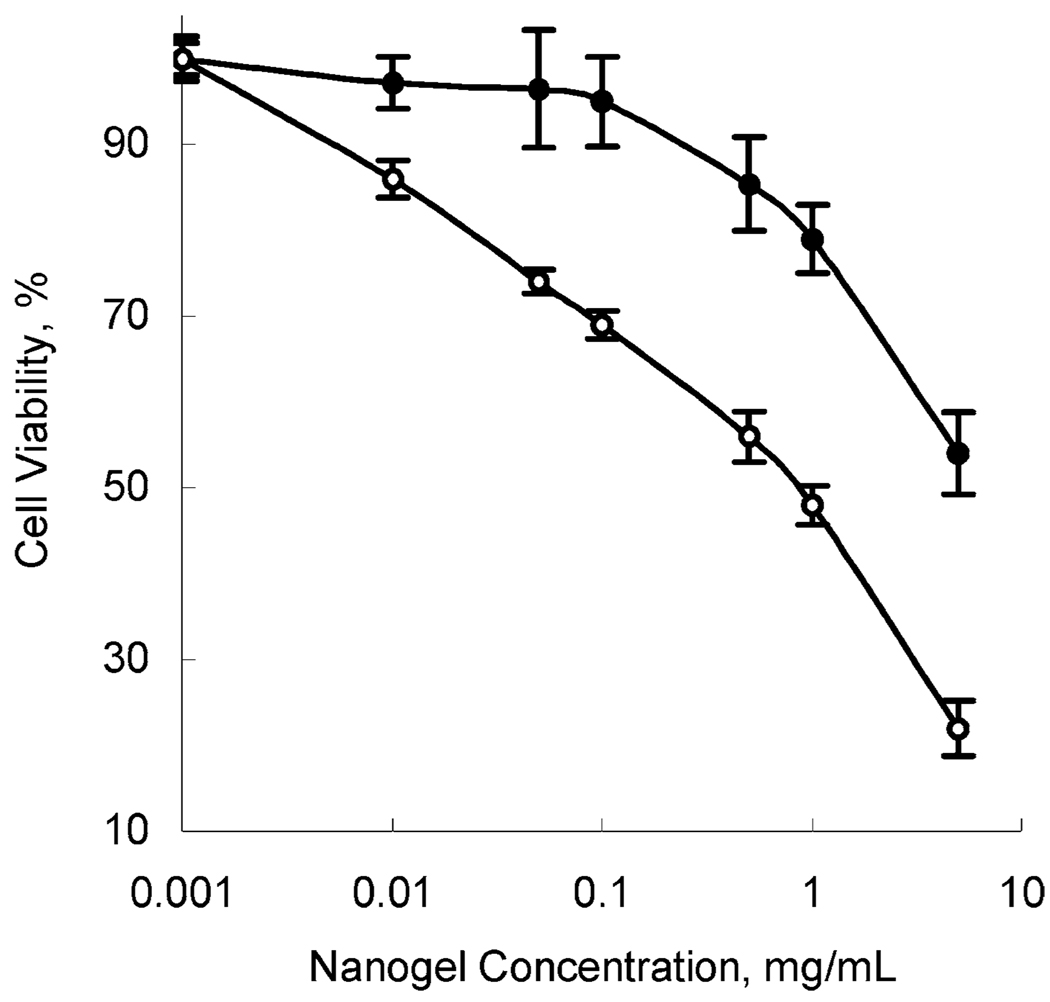

Toxicity of Nanogel

Cytotoxicity of nanogel was examined in BBMEC monolayers using MTT assay. Cells were exposed over the period of 2 h to various concentrations of unloaded and ODN-loaded (N/P = 8) nanogel and the cell viability was tested (Figure 3). Nanogel carriers showed little cytotoxicity with respect to the BBMEC. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity was noticeably decreased when the positive charge of nanogel was neutralized by negatively charged ODN. The IC50 values were ca. 0.9 mg mL−1 and 6 mg mL−1 for the free and loaded nanogel, respectively. Nanogel concentrations of about 0.1–0.2 mg mL−1 (0.01–0.02%) were relatively nontoxic in both cases, and this concentration range was used in further studies. Preliminary data obtained in animal experiments also revealed no acute toxic effects of nanogel-ODN complexes administered iv in FVB wild-type mice at cumulative dose of up to 15 mg nanogel–ODN per mice.

Figure 3.

Cell viability based on MTT assay following the incubation of nanogel–ODN complex (black circles), or unloaded nanogel (open circles) with BBMEC monolayers for 2 h at 37 °C. IC50 values are equal to 0.9 mg/mL for nanogel alone, and 6 mg/mL for nanogel–ODN complex.

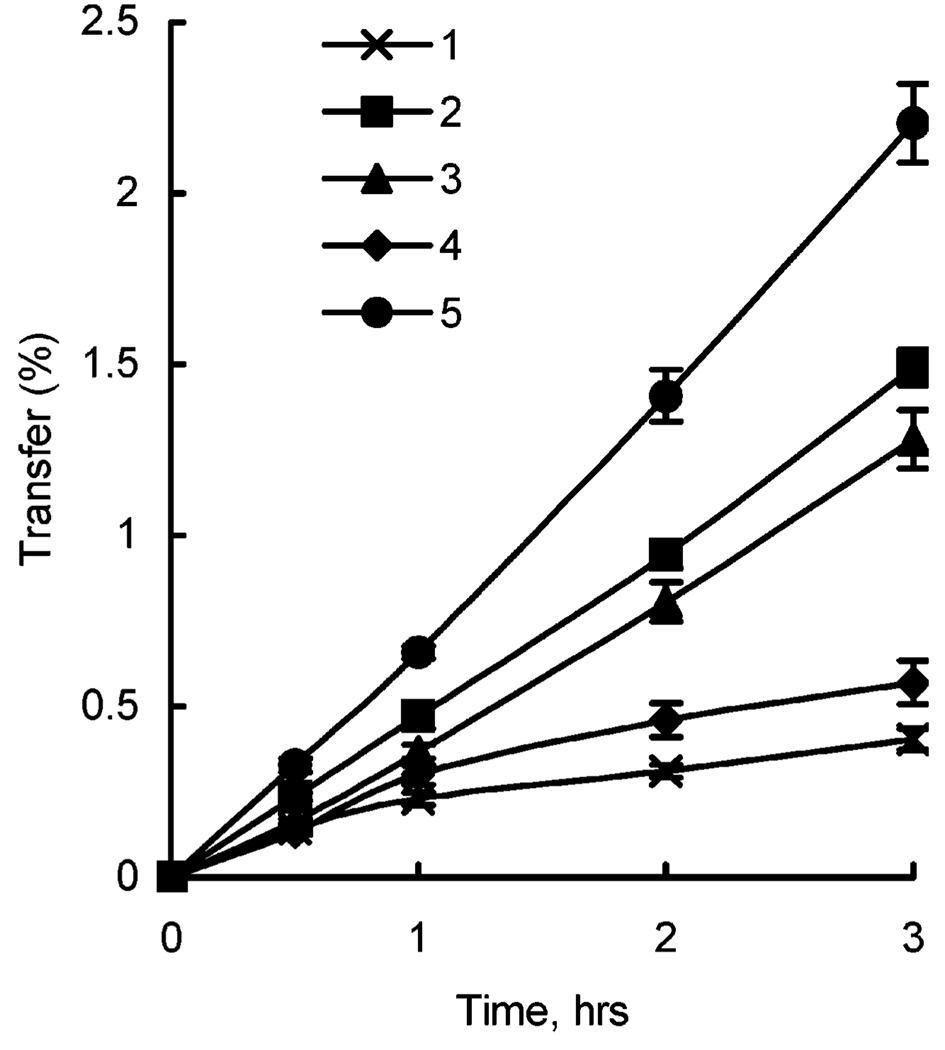

Transport across BBMEC Monolayers

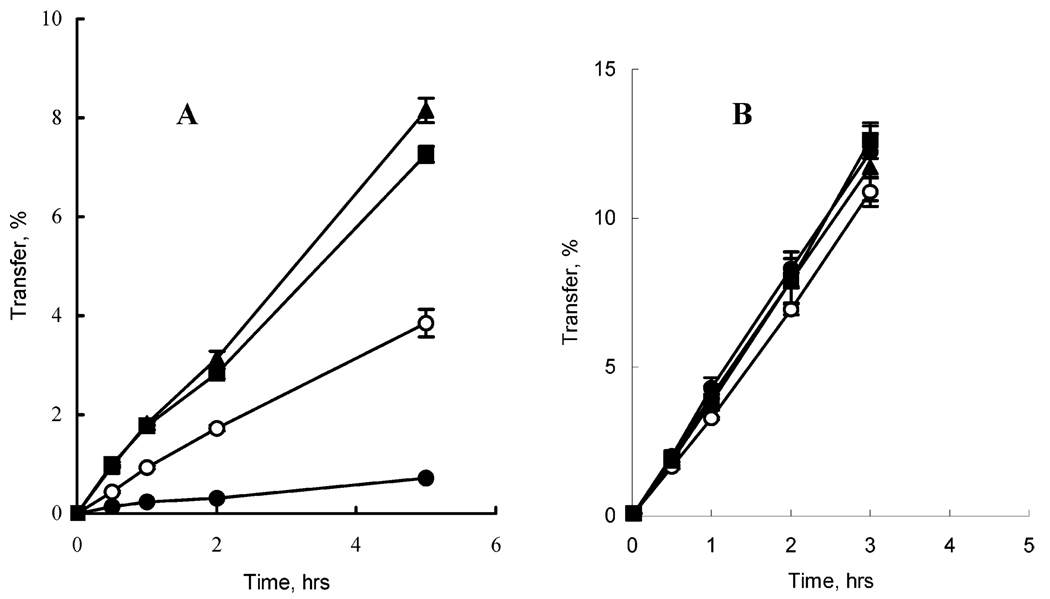

To evaluate potential effects of nanogel on the delivery of ODN to the brain, we examined ODN permeability using BBMEC monolayers as an in vitro model of BBB. Polarized BBMEC monolayers were grown on membrane filter inserts, which were placed in standard Side-By-Side diffusion chambers. Initial studies characterized the transport of RITC-labeled nanogel from apical (lumenal) to basolateral (ablumenal) side of the monolayers as a function of the composition of the complexes (N/P ratio) as presented in Figure 4. This figure also presents the data on the transport of FITC-labeled ODN for comparison. These data suggest that there is little if any difference in the permeability of unloaded nanogel batches 1 and 2. At the same time the rate of transport of loaded nanogels drastically depended on the composition of the complex. Specifically, the complex prepared at N/P = 8 that displays positive charge (see Table 1) was transported more efficiently than the complex at N/P = 4 having slight negative charge.

Figure 4.

Transport of FITC-labeled ODN and RITC-labeled nanogel particles across BBMEC monolayers: 1, free ODN; 2, unloaded nanogel (batch 1); 3, unloaded nanogel (batch 2); 4, complex of ODN and nanogel (batch 1), N/P = 4; 5, complex of ODN and nanogel (batch 1), N/P = 8. Transport of ODN and nanogel was determined by measuring fluorescence of the corresponding probe (1, FITC; 2–5, RITC) in the receiver chamber. Concentrations of the compounds in the donor chambers were as follows: nanogel, 0.03%, ODN, 2.5–5 µM.

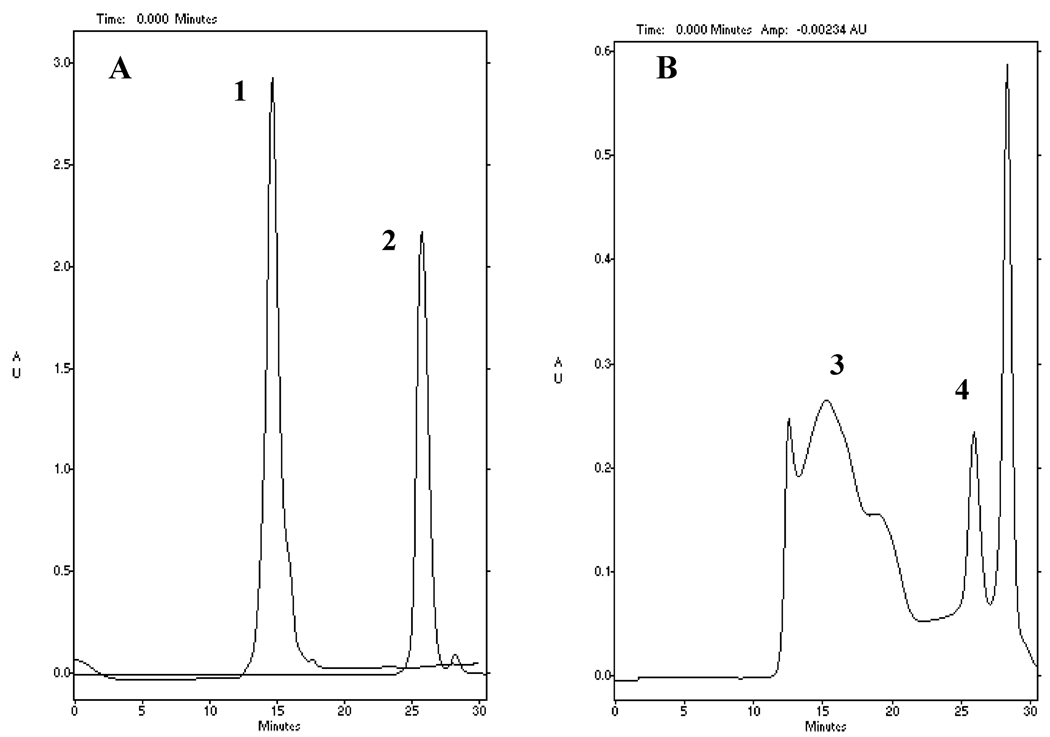

Further study examined whether the ODN transported with nanogel in BBMEC monolayers remains bound to the nanogel or becomes released from it in the receiver chamber. For this purpose the samples from the receiver chamber were analyzed by gel permeation chromatography with UV absorbance at 270 nm. The chromatography profiles are shown in Figure 5. From analysis of the chromatography data it appears that at least ca. 2/3 of ODN detected in the receiver chamber at 2 h time point of the transport study was incorporated in the complex with nanogel (compare peak 3 in Figure 5B with peak 1 in Figure 5A). About 10% appeared to be the free undegraded ODN released from the complex (compare peak 4 in Figure 5B with peak 2 in Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Gel permeation chromatography of ODN and nanogel–ODN complexes. (A) Nanogel–ODN complex (N/P = 8) added in the donor chamber (peak 1) or free ODN added in the donor chamber (peak 2). (B) Nanogel–ODN complex in receiver chamber following transport across the BBMEC monolayers (2 h, 37 °C). The chromatography peaks were assigned as follows: nanogel–ODN complex (peak 3), released ODN (peak 4), last peak relates to UV-absorbing low-molecular weight compounds.

To directly assay the ODN transported through the BBMEC monolayer we used an anion exchange HPLC analysis described previously (27). This technique uses highly positively charged chromatography matrix Nucleopac PA-100. When ODN-loaded nanogel particles were applied on the column containing this matrix, the encapsulated ODN was effectively released from the nanogel and eluted with its normal retention time (t = 4.5 min, data not shown). As a result the total ODN in the receiver chamber (both free and nanogel bound) could be easily quantified at the concentrations as low as 5–10 nM. This HPLC technique was used to examine the relative permeability of the free and nanogel–bound ODN in BBMEC monolayers.

In all transport experiment the ODN concentration in the donor chamber was 5 µM. The concentrations of nanogels used in the permeability studies were 0.01–0.02%. A paracellular marker, 3H-mannitol, was also added in the donor chamber to assess possible changes in the integrity of the BBMEC monolayers in the presence of either ODN or its complexes with nanogel. Figure 6 presents the ODN and mannitol permeability data. The ODN permeability coefficients calculated on the base of the transport data are presented in Table 2. Formulation of ODN with nanogel resulted in permeability increases compared to the free ODN. Specifically, at N/P = 4 the permeability increase was only 2-fold (data not shown in Figure 6). At N/P = 8 the increase was almost 6-fold. Therefore, the N/P = 8 was used in experiments to further enhance ODN transport by adding peptide ligands to nanogel formulations. Modification of nanogel with either insulin or transferrin through the avidin-biotin bridges resulted in ca. 11- to 12-fold permeability increases compared to the free ODN. With all ODN formulations used, there were no changes in the permeability of mannitol, which remained the same as its permeability in the absence of the ODN formulations (2.4 × 10−6, cm s−1). Therefore, neither free ODN, nor its nanogel formulations, affected the tight junctions in the BBMEC monolayers.

Figure 6.

(A) Transport of free ODN and ODN formulated with nanogel across BBMEC monolayers. (B) Transport of paracellular marker, 3H-mannitol, in the presence of the ODN and its formulations with nanogel. The symbols correspond to free ODN (black circles); nanogel–ODN complex (open circles); transferrin-vectorized nanogel–ODN complex ODN (squares); insulin-vectorized nanogel–ODN complex (triangles). All nanogel–ODN complexes are prepared at N/P = 8. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3).

Table 2.

Permeability Coefficients of ODN and Its Nanogel Formulations in BBMEC Monolayers

| ODN formulations | N/P ratio | Papp × 106, cm s−1e |

|---|---|---|

| free ODNa | – | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| nanogel-ODNb | 4 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| 8 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | |

| insulin-nanogel-ODNc | 8 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| transferrin-nanogel-ODNd | 8 | 0.86 ± 0.02 |

ODN concentration was 5 µM in all experiments.

Biotinylated nanogel was used at 0.02 wt %, except for N/P = 4, used at 0.01 wt %.

Avidin-bovine insulin, 1.25 µM.

Avidin-bovine transferrin, 2.5 µM

Data are means ± SEM (n = 3).

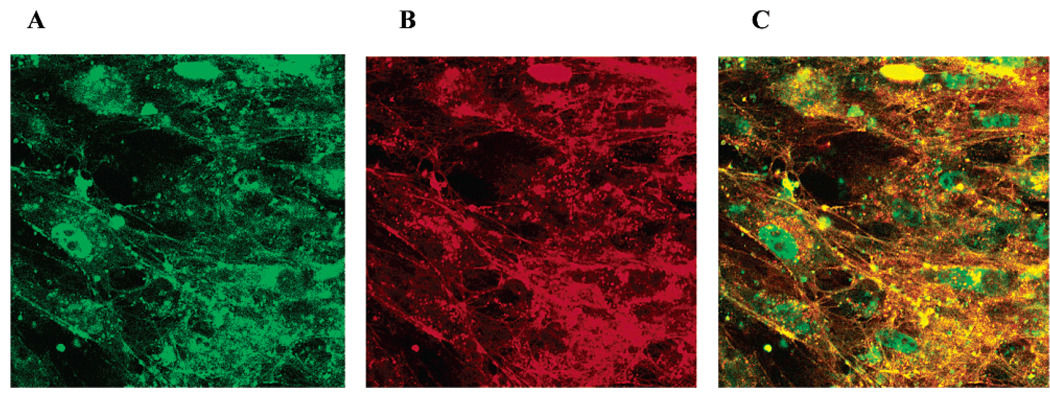

Fluorescence Microscopy Studies

Localization of ODN and nanogel following their uptake in BBMEC monolayers for 2 h was examined by laser confocal fluorescent microscopy. These experiments used FITC-labeled ODN and RITC-labeled nanogel to visualize both components within the cell. Typical micrographs are presented in Figure 7. All three images are recorded from the same sample. Panel A shows the localization of FITC-ODN. Panel B shows the localization of RITC-nanogel. Panel C is the superposition of images A and B displaying localization of both ODN and nanogel. Fluorescein label (ODN) was mainly spread throughout the cells with significant portion displayed in what appears to be cytoplasmic compartments (panel A). Similar cytoplasmic localization was displayed in the case of the rhodamine label (nanogel) (panel B). In the superposed images the areas of colocalization of ODN and nanogel are evident by yellow and orange colors (panel C). However, this panel also clearly shows that in selected cells a portion of fluorescein label is displayed in the nucleus, while practically no rhodamine fluorescence was found in the nucleus.

Figure 7.

Confocal fluorescent microscopy of BBMEC monolayers after the incubation (2 h) with FITC-labeled ODN loaded into RITC-labeled nanogel. The images were recorded using λex 460–500 nm, λba 510–560 nm filter for FITC-ODN (A), and λex 540–575 nm, λba 605–655 nm-filter for RITC-nanogel (B). Panel C is the superposition of images A and B. Magnification ×100.

We have previously speculated that ODN-loaded nanogel can be transported into the cells via endocytosis with some portion crossing the cytoplasmic membrane (20). Specifically, despite of the presence of PEO chains, the PEI chains of nanogel are positively charged at endosomal pH, which can destabilize endosomal membrane either by the mechanism similar to that called “proton sponge” (32), or by forming cationic patches as a result of interaction of PEI with phospholipid bilayer (33). Since ODN chains are relatively short (19 phosphates) and their cooperativity of binding to nanogel is relatively small, some portion of ODN can obviously release in the cytoplasm and then transport into the nucleus through the pores in the nuclear membrane. In contrast, the nanogel particles cannot penetrate through the pores since the size exclusion of these pores is about 20 nm, which is much smaller that even the loaded nanogel particles. (Release of a portion of ODN from nanogel could only result in swelling and increase of the size of the latter). An important result of these studies is that even though a portion of ODN appears to be released in BMVEC a significant portion of it remains bound to the nanogel, a result consistent with the permeability experiments described above.

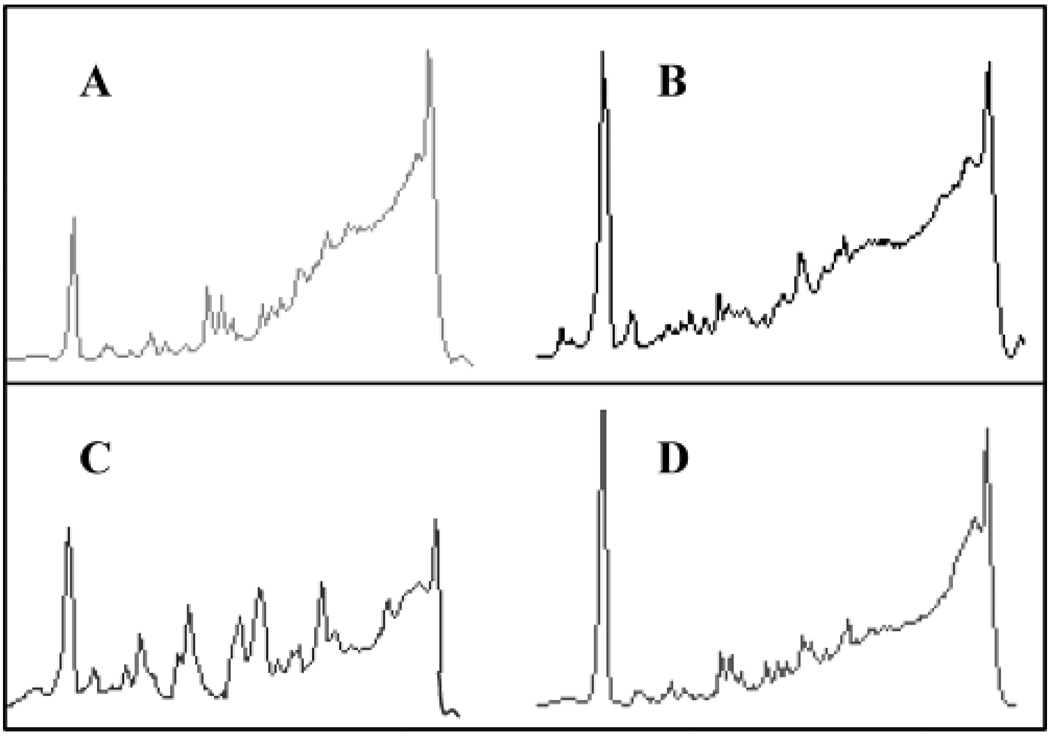

Stability of Nanogel in Serum

To examine the protection of ODN against nuclease degradation the free ODN or nanogel-ODN complexes were incubated in freshly prepared mouse serum. As is seen in Figure 8 after 1 h incubation in serum substantial amount of free ODN was degraded (compare panels A and C). In contrast ODN incorporated in nanogel displayed little if any degradation (panels B and D).

Figure 8.

Nuclease resistance of free ODN and ODN incorporated in nanogel in mouse blood serum. The experiment was conducted as follows: Free ODN (5 µM) was added to freshly prepared mouse serum and immediately analyzed by ion-pair reverse phase HPLC (A) or incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and then analyzed by HPLC (C). Similarly, ODN incorporated in nanogel (5 µM, N/P = 8) was added to serum and analyzed immediately (B) or after 1 h incubation (D). In all cases prior to HPLC analysis the samples (200 µL) were mixed with 40 µL of 50 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate solution, proteins were removed by phenol extraction of proteins, and ODN was precipitated by ethanol. The ion-pair reverse phase HPLC was performed on the Spherisorb C18 column (0.4 × 15 cm), elution rate 1 mL/min using 0.2% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, 50 mM potassium hydrogen phosphate, and 0.1 M sodium chloride in the gradient of acetonitrile 0 to 40%.

In Vivo Biodistribution Studies

Finally, in vivo biodistribution of radioactively labeled ODN and nanogel was characterized in mice. The initial studies were conducted using complexes of ODN with 3H-labeled nanogel injected iv. The injected dose contained 120 µg of nanogel. Following 1 h after injection, only 2.8% of injected dose (3.4 µg) of nanogel was detected in 1 g of blood. Significant portion of the injected dose was distributed in the organs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biodistribution of Free ODN and the Nanogel–ODN Compositions

| radioactivity distribution in tissues, % of injected dose/ga | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| injected composition | plasma | brain | lung | liver | spleen |

| nanogel-3H-ODN | 3.00 ± 0.16 | 5.34 ± 0.33 | 2.26 ± 0.22 | 4.34 ± 0.28 | 3.82 ± 0.20 |

| 3H-nanogel-ODN | 2.81 ± 0.27 | 2.67 ± 0.13 | 1.80 ± 0.09 | 3.80 ± 0.70 | 3.12 ± 0.16 |

| 3H-ODN | 2.02 ± 0.26 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 2.50 ± 0.30 | 7.14 ± 0.55 | 10.12 ± 0.90 |

Injected compositions (0.1 mL) contained 50 µM ODN and 0.12% nanogel in PBS (N/P = 8).

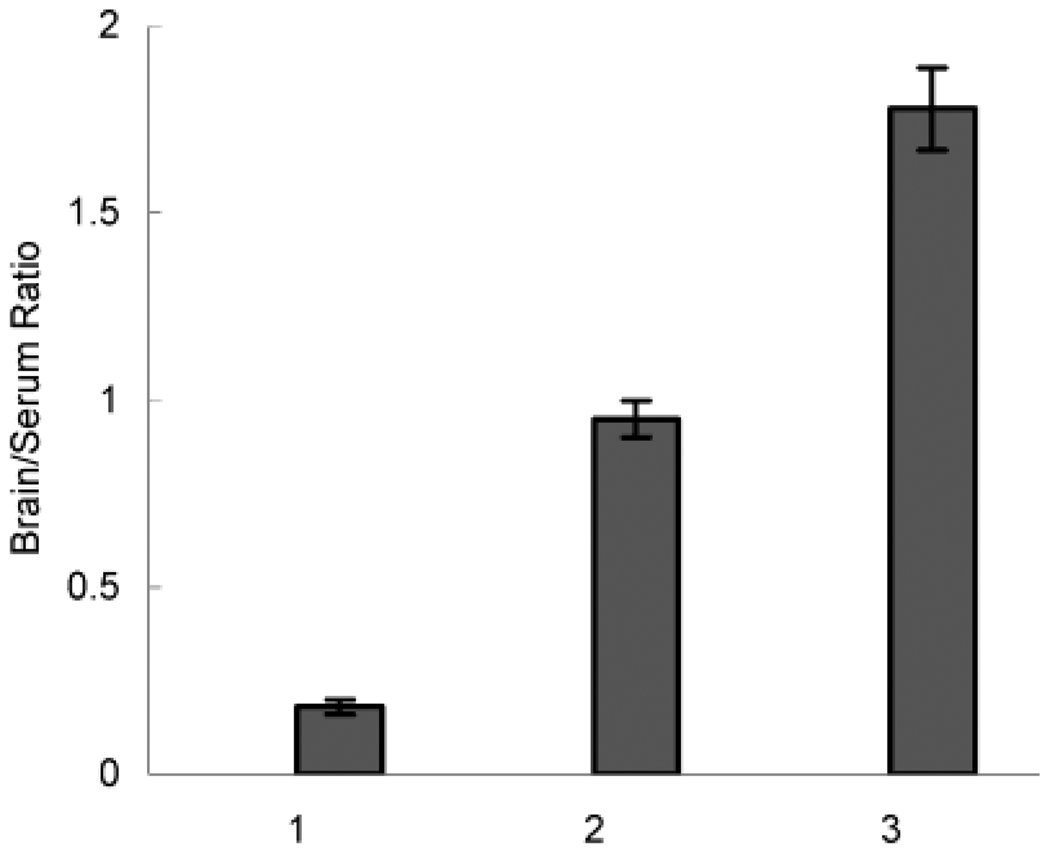

We further used 3H-labeled ODN to assess its biodistribution after iv injection in a free form or as nanogel–ODN formulation. Previous studies reported that the highest levels of ODN are found in liver and spleen, with significantly smaller quantity of ODN accumulating in the brain (~0.3%) (34–36). As is seen in Table 3, our data for the free ODN were consistent with these observations. However, for nanogel-ODN complexes the amount of the radioactivity in the brain was greatly increased compared to the free ODN. At the same time the accumulation of the radioactivity in the liver and spleen was significantly decreased while plasma and lungs displayed relatively less changes. It was shown that the tritium label introduced into phosphorothioate ODN using the same technique is metabolically stable in blood in vivo for at least 2 h after injection (23). Therefore, the results of our experiments strongly suggest that formulation of ODN with nanogel leads to increased brain and decreased liver and spleen accumulations compared to the free phosphorothioate ODN. This effect in the brain is further illustrated in Figure 9 presenting brain/plasma ratios for free ODN and nanogel–ODN formulations 1 h after iv injection. This ratio for the nanogel–ODN formulation increased by as much as 1 order of magnitude compared to the free ODN. It also appears from this study that nanogel formulation at N/P = 8 was more efficacious in brain delivery of ODN than the formulation at N/P = 4.

Figure 9.

Brain/plasma ratios for the free (1) 3H-ODN and its complexes with nanogel prepared at (2) N/P = 4 and (3) N/P = 8 following iv administration in mice. Animals were sacrificed 1 h after the injection, and the tritium radioactivity in the tissue samples was analyzed. The data represent average values ± SEM (n = 4).

On the basis of these studies, it appears that nanogel carriers can protect ODN from rapid clearance by peripheral tissues and increase ODN transport to the brain. It was demonstrated that iv-injected phosphorothioate ODNs strongly bind to albumin and other plasma proteins (37). Encapsulation of ODN in nanogels may have protective effect reducing the nonspecific interactions. It could also decrease the renal clearance of ODN because the molecular mass of nanogel–ODN complexes exceeds the renal clearance threshold (38). However, to fully address this issue, further studies of the in vivo properties of nanogel carriers need to be done.

CONCLUSIONS

A novel ODN delivery system based on positively charged nanosized hydrogel particles, nano-PEG-cross-PEI, has been developed. The ODN-loaded nanogel remains stable in dispersion due to the solubilizing effect of nonionic hydrophilic PEG chains resulting in a formation of nanosized particles. Nanogel structure enables easy attachment of vector groups for targeted delivery. In particular, nanogel carriers vectorized with insulin and transferrin molecules were shown to efficiently deliver antisense ODN across BBB as demonstrated using a cell model, BBMEC. Following transport across the brain microvessel endothelial cells a significant portion of ODN remained associated with nanogel. Nanogel carriers have low toxicity, especially in the loaded form, and show no adverse toxic effect being injected intravenously in mice. Further studies in vivo should reveal the potential for the use of the vectorized nanogel carriers for systemic delivery of antisense ODN into the brain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The studies were supported in parts by grants from National Science Foundation (BES 9986393) and National Institutes of Health (NS 366229) awarded to A.V.K‥ NanoGel is a trademark of Supratek Pharma Inc. (Montreal, Canada), who supported part of the work on synthesis of the nanogel material. A.V.K. is a cofounder and consultant for this company. The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Shu Li in performing of the transport studies on BBMEC mono-layers.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Boado RJ, Tsukamoto H, Pardridge WM. Drug delivery of antisense molecules to the brain for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral AIDS. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87:1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/js9800836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman S, Eckstein F, Grifman M, Soreq H. Antisense technologies have a future fighting neurodegenerative diseases. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1999;9:333–340. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1999.9.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field AK. Oligonucleotides as inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 1999;1:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho SP, Hartig PR. Antisense oligonucleotides for target validation in the CNS. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 1999;1:336–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy MM, Auger AP, Mong JA, Sickel MJ, Davis AM. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides as a tool in developmental neuroendocrinology. Methods. 2000;22:239–248. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Prasad G, Buolamwini JK, Zhang R. Antisense anticancer oligonucleotide therapeutics. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2001;1:177–196. doi: 10.2174/1568009013334133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias N, Stein CA. Potential roles of antisense oligonucleotides in cancer therapy. The example of Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotides. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2002;54:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broaddus WC, Prabhu SS, Wu-Pong S, Gillies GT, Fillmore H. Strategies for the design and delivery of antisense oligonucleotides in central nervous system. Methods Enzymol. 2000;314:121–135. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)14099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuo H, Okamura T, Chen J, Takanaga H, Ohtani H, Kaneda Y, Naito M, Tsuruo T, Sawada Y. Efficient introduction of macromolecules and oligonucleotides into brain capillary endothelial cells using HVJ-liposomes. J. Drug Target. 2000;8:207–216. doi: 10.3109/10611860008997899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merdan T, Kopecek J, Kissel T. Prospects for cationic polymers in gene and oligonucleotide therapy against cancer. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:715–758. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigger I, Dubernet C, Couvreur P. Nanoparticles in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Adv Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002;54:631–651. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardridge WM. Drug and gene targeting to the brain with molecular Trojan horses. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2002;1:131–139. doi: 10.1038/nrd725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreuter J. Nanoparticulate systems for brain delivery of drugs. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;47:65–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardridge WM, Eisenberg J, Yang J. Human blood-brain barrier insulin receptor. J Neurochem. 1985;44:1771–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pardridge WM, Eisenberg J, Yang J. Human blood-brain barrier transferrin receptor. Metabolism. 1987;36:892–895. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Jeong Lee H, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Receptor-mediated delivery of an antisense gene to human brain cancer cells. J Gene Med. 2002;4:183–194. doi: 10.1002/jgm.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabanov AV, Vinogradov SV. Supratek Pharma, Inc.,US. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinogradov SV, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Poly(ethylene glycol)-polyethyleneimine NanoGel particles: novel drug delivery systems for antisense oligonucleotides. Coll. Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 1999;16:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemieux P, Vinogradov SV, Gebhart CL, Guerin N, Paradis G, Nguyen HK, Ochietti B, Suzdaltseva YG, Bartakova EV, Bronich TK, St-Pierre Y, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV. Block and graft copolymers and NanoGel copolymer networks for DNA delivery into cell. J. Drug Target. 2000;8:91–105. doi: 10.3109/10611860008996855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Nanosized cationic hydrogels for drug delivery: preparation, properties and interactions with cells. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nag A, Mitra G, Ghosh PC. A colorimetric assay for estimation of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(ethylene glycol)ated protein using ammonium ferrothiocyanate. Anal. Biochem. 1996;237:224–231. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mock DM, Lankford G, Horowitz P. A study of the interaction of avidin with 2-anilinonaphthalene-6- sulfonic acid as a probe of the biotin binding site. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;956:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledoan T, Auger R, Benjahad A, Tenu JP. High specific radioactivity labeling of oligonucleotides with 3H-succinimidyl propionate. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1999;18:277–289. doi: 10.1080/15257779908043074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DW, Audus KL, Borchardt RT. Application of cultured bovine brain endothelial cells of the brain microvasculature in the study of the blood-brain barrier. J. Tissue Cult. Methods. 1992;14:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrari M, Fornasiero MC, Isetta AM. MTT colorimetric assay for testing macrophage cytotoxic activity in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 1990;131:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90187-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batrakova EV, Li S, Miller DW, Kabanov AV. Pluronic P85 increases permeability of a broad spectrum of drugs in polarized BBMEC and Caco-2 cell monolayers. Pharm. Res. 1999;16:1366–1372. doi: 10.1023/a:1018990706838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourque AJ, Cohen AS. Quantitative analysis of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides in biological fluids using fast anion-exchange chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1993;617:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batrakova EV, Miller DW, Li S, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV, Elmquist WF. Pluronic P85 enhances the delivery of digoxin to the brain: in vitro and in vivo studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;296:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Self-assembly of polyamine-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers with phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Bioconjugate Chem. 1998;9:805–812. doi: 10.1021/bc980048q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronich T, Vinogradov S, Kabanov AV. Interaction of nanosized copolymer networks with oppositely charged amphiphilic molecules. Nano Lett. 2001;1:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogris M, Brunner S, Schuller S, Kircheis R, Wagner E. PEGylated DNA/transferrin-PEI complexes: reduced interaction with blood components, extended circulation in blood and potential for systemic gene delivery. Gene Ther. 1999;6:595–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, Behr JP. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 1995;92:7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helander IM, Latva-Kala K, Lounatmaa K. Permeabilizing action of polyethyleneimine on Salmonella typhimurium involves disruption of the outer membrane and interactions with lipopolysaccharide. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 2):385–390. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banks WA, Farr SA, Butt W, Kumar VB, Franko MW, Morley JE. Delivery across the bloodbrain barrier of antisense directed against amyloid beta: reversal of learning and memory deficits in mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:1113–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geary RS, Yu RZ, Levin AA. Pharmacokinetics of phosphorothioate antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2001;2:562–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu D, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Pharmacokinetics and blood-brain barrier transport of [3H]- biotinylated phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotide conjugated to a vector-mediated drug delivery system. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan SK, Tewary HK, Iversen PL. Characterization of binding sites, extent of binding, and drug interactions of oligonucleotides with albumin. Characterization of binding sites, extent of binding, and drug interactions of oligonucleotides with albumin. Antisense Res. Dev. 1995;5:131–139. doi: 10.1089/ard.1995.5.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawai K, Miyao T, Takakura Y, Hashida M. Renal disposition characteristics of oligonucleotides modified at terminal linkages in the perfused rat kidney. Antisense Res. Dev. 1995;5:279–287. doi: 10.1089/ard.1995.5.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]