Abstract

Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae have been used extensively to study the structure and dynamics of the endocytic pathway. Here, we show that while the general structure of the endocytic pathway is maintained in starved cells, its dynamics rapidly slow down. In addition, analysis of apm3 and lvsB mutants reveals that the functional organization of the endocytic pathway is profoundly modified upon starvation. Indeed, in these mutant cells, some of the defects observed in rich medium persist in starved cells, notably an abnormally slow transfer of endocytosed material between endocytic compartments. Other parameters, such as endocytosis of the fluid phase or the rate of fusion of postlysosomes to the cell surface, vary dramatically upon starvation. Studying the endocytic pathway in starved cells can provide a different perspective, allowing the primary (invariant) defects resulting from specific mutations to be distinguished from their secondary (conditional) consequences.

Dictyostelium discoideum is a widely used model organism for studying the organization and function of the endocytic pathway. In Dictyostelium, the organization of the endocytic pathway is similar to that in higher eukaryotes. The pathway in Dictyostelium can be divided into four steps (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material): uptake at the plasma membrane of particles and medium, transfer through early acidic endocytic compartments (lysosomes), passage into less acidic postlysosomes (PLs), and finally, exocytosis of undigested materials (17, 20). Thus, Dictyostelium recapitulates many of the functions of the endocytic pathway in mammalian cells, including some features observed in most cell types (lysosome biogenesis) and some observed only in specialized cells (phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, and lysosome secretion).

Dictyostelium amoebae live in the soil, where they feed by ingesting and digesting other microorganisms. In addition, axenic laboratory strains can macropinocytose medium to ensure their growth. Accordingly, both in natural situations and in laboratory settings, the endocytic pathway plays a key role in the acquisition of nutrients by Dictyostelium cells. In agreement with this notion, several observations suggest that the physiology of the endocytic pathway is sensitive to nutrient availability. In particular, starvation induces secretion of lysosomal enzymes by an unknown mechanism (11). The morphology of the endocytic pathway is also sensitive to nutritional cues, as shown for example by the observation that formation of multilamellar endosomes is enhanced in cells fed with bacteria (18).

Here, we analyzed the effect of starvation on the organization as well as the dynamics of the endocytic pathway. We found that, while the overall organization was not extensively modified in starved cells, the dynamics of endocytic compartments were altered. Moreover, analysis of two specific knockout mutants, the apm3 (6) and lvsB (8) strains, revealed that their phenotype was profoundly altered upon starvation, providing further insight about the role of Apm3 and LvsB in the endocytic pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

Dictyostelium discoideum cells were grown at 21°C in HL5 medium (14.3 g/liter peptone [Oxoid, Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom], 7.15 g/liter yeast extract [Brunschwig BD Difco, Basel, Switzerland], 18 g/liter maltose [Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland], 3.6 mM Na2HPO4, and 3.6 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.7]) and subcultured twice a week. Cells were not allowed to reach a density of more than 106 cells/ml. All strains used in this study were derived from the subclone DH1-10 (9) of Dictyostelium discoideum DH1 (2). lvsB (8) and apm3 (19) mutant cells were described previously.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against the p80 endosomal marker (H161), p25 (H72), and plasma membrane protein H36 (H36) were described previously (6, 19, 22). A rabbit antiserum against the Rhesus 50 protein was also described previously (1). 221-35-2 is a mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing vacuolar H+-ATPase (21) and was a kind gift from G. Gerisch (Max-Planck Institute, Martinsried, Germany). For colabeling experiments, the H161 antibody was coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

All experiments described here were performed using cells attached to glass coverslips. Cells (5 × 105) were collected and allowed to attach on an ethanol-sterilized glass coverslip (22 by 22 mm) in 2 ml HL5 medium for 60 min. They were then rinsed twice and incubated for the indicated time in 3 ml of HL5, phosphate buffer (PB; 2 mM Na2HPO4, 14.7 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.0), or starvation medium (StM; PB supplemented with 0.5% HL5, 100 mM sorbitol, and 100 μM CaCl2). They were then fixed for immunofluorescence or used in kinetic experiments as described below. Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (19).

To measure the sizes of lysosomes and PLs, random confocal images of cells stained for both H+-ATPase and p80 were taken. On each image, the diameters of all discernible lysosomes and PLs were measured using the line scan tool in the Metamorph 6.0 software program (Universal Imaging Corporation, Downingtown, PA). Twenty cells were analyzed for each cell type and at each time point in each experiment. The quantification of the number of p80 patches at the cell surface was carried out as already described (4). At least 300 cells were analyzed for each cell type in each experiment.

Transfer of latex beads between endocytic compartments.

To determine the kinetics of lysosome maturation, cells attached to glass coverslips were preincubated for 90 min in either HL5 or StM. They were then incubated in the same medium with fluorescent 1-μm-diameter latex beads (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) for 15 min (approximately one bead internalized for every 10 cells), washed twice with the same medium, and incubated further for various periods of time before fixation. Fixed cells were processed for immunofluorescence as described above to detect both the H+-ATPase and the p80 protein. Beads present in lysosomes and PLs were counted, and the proportion present in PLs was calculated. Thirty internalized beads were analyzed for each cell type and at each time point in each experiment.

Endocytosis of fluid phase.

Cells attached on coverslips and incubated for various times in the indicated medium were then incubated for 20 min in the same medium containing 20 μg/ml Alexa 647-labeled dextran (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cells were then detached and washed twice with StM containing 0.1% sodium azide, and internalized fluorescence was measured with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Secretion of lysosomal enzymes.

Cells (0.5 × 106) attached to glass coverslips were incubated in 400 μl of the indicated medium for 4 h. The supernatant was then collected, and cells were detached from the coverslips and collected by centrifugation. Medium containing 0.1% Triton X-100 was added to all samples to allow measurement of intracellular lysosomal enzyme activity.

To determine the enzymatic activity in each sample, 50 μl of the sample was added to 50 μl of a substrate mixture (10 mM substrate in 5 mM NaOAc, pH 5.2) and incubated for 40 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 1 M Na2CO3, and the optical density at 405 nm was determined with a microplate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. Enzyme substrates (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in dimethyl formamide (DMF) at a concentration of 250 mM and stored at −20°C. p-Nitrophenyl N-acetyl β-d-glucosamide was used as substrate for N-acetylglucosaminidase.

RESULTS

Starvation does not affect the structure of the endocytic pathway.

Specific antibodies recognizing proteins of the endocytic pathway can be used to label endocytic compartments (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material): p80 is present mostly in lysosomes and postlysosomes (PLs) (22); p25 is present at the cell surface and in recycling endosomes (6); and the Rhesus protein is restricted to the contractile vacuole (1), H36 to the cell surface (19), and H+-ATPase to lysosomes and the contractile vacuole (21).

Using these markers, we assessed the organization of the endocytic compartments in cells grown in rich HL5 medium or incubated for up to 4 h under starvation conditions. As a first step, we tested the effects of different procedures inducing cell starvation. Although it is notably hypotonic, phosphate buffer (PB; 17 mM) is often used to induce starvation. When cells starved in PB were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence, we observed that the organization of the endocytic pathway was profoundly perturbed compared to the level for cells grown in HL5 medium (Fig. 1). Endocytic compartments were poorly labeled, and individual compartments were difficult to distinguish.

Fig. 1.

Starvation in isotonic medium does not cause major alterations in Dictyostelium endocytic compartments. Dictyostelium wild-type cells grown in HL5 were starved in PB (hypotonic) or in StM (isotonic) medium for 2 h and then processed for immunofluorescence to detect p80 and H+-ATPase. Cells incubated in HL5 or starved in StM exhibited distinctive lysosomes (p80 positive and H+-ATPase positive; arrowheads) and postlysosomes (p80 positive and H+-ATPase negative; arrows). In contrast, cellular architecture was grossly altered when cells were starved in PB. The compartments positive for H+-ATPase but negative for p80 represent contractile vacuoles (pinheads). Scale bar, 5 μm.

In order to assess if the alterations seen in PB were due to starvation or to a hypotonic shock, we tested an alternative isotonic starvation medium (StM) supplemented with 100 mM sorbitol. Since it is also our experience that a complete depletion of nutrients, as well as the use of a calcium-depleted medium, can be deleterious for cell survival (data not shown), the alternative starvation medium was also supplemented with trace amounts of nutrients (0.5% of the concentration in HL5) and 100 μM calcium chloride. Dictyostelium cells incubated in PB or in StM exhibited hallmarks of starved cells, notably lysosomal enzyme secretion (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and induction of multicellular development (data not shown). In cells starved in StM, however, the organization of the endocytic pathway was extremely similar to that seen in cells grown in HL5 (Fig. 1). In particular, after double labeling for p80 and H+-ATPase, one could clearly distinguish lysosomes (p80 positive and H+-ATPase positive) (Fig. 1, arrowheads), PLs (p80 positive and H+-ATPase negative) (Fig. 1, arrows), and the contractile vacuole (p80 negative and H+-ATPase positive) (Fig. 1, pinheads). Recycling endosomes, revealed with an anti-p25 antibody, were also unaffected in cells starved in StM (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In addition, the Rhesus protein was still restricted to the contractile vacuole and H36 to the cell surface (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that most of the alterations seen in cells starved in PB were due to its hypotonicity and that starvation itself did not induce profound alterations of the endocytic pathway. For the rest of this study, only StM was used to induce starvation.

The dynamics of the endocytic pathway are altered in starved cells.

To determine whether starvation affects intracellular transport along the Dictyostelium endocytic pathway, we measured three distinct kinetic parameters: uptake of fluid phase; transfer of internalized material from lysosomes to PLs; and fusion of PLs with the cell surface, visualized by the transient formation of an exocytic patch.

To measure fluid phase uptake, we incubated cells in medium containing fluorescent dextran and quantified by flow cytometry the fluorescence internalized by the cells. After 60 min or more of starvation, endocytosis of the fluid phase was decreased to 20% of that measured in rich medium (Fig. 2A).

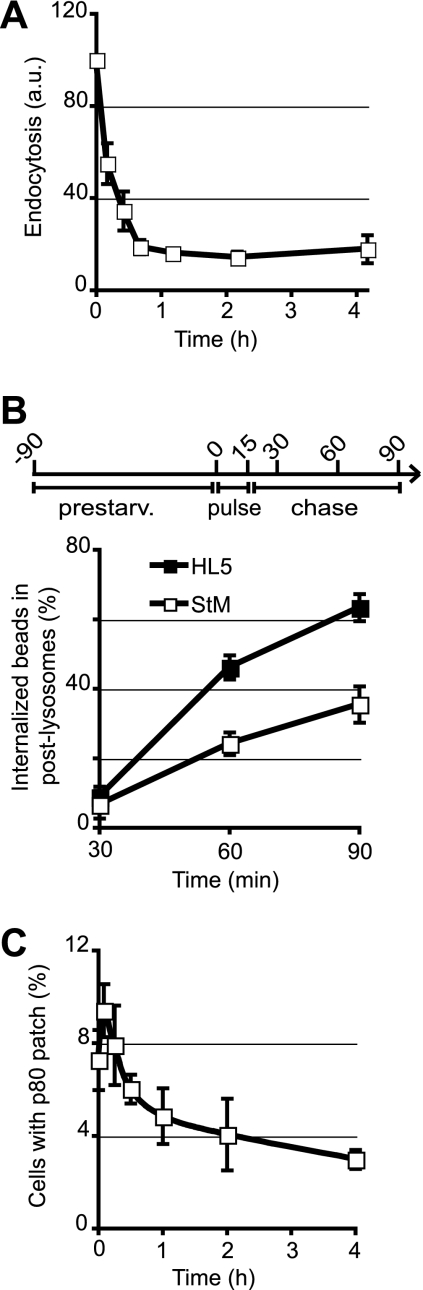

Fig. 2.

Transport along the endocytic pathway is slower in starved cells. (A) Slower endocytosis of the fluid phase in starved cells. Cells were preincubated for the indicated time in StM and then allowed to internalize fluorescent dextran in StM for 20 min. Internalized fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (FACS). Endocytosis at time zero corresponds to endocytosis in HL5. a.u., arbitrary units. (B) Lysosome maturation is slowed down in starved cells. As depicted in the experimental design scheme, cells were prestarved in StM for 90 min; allowed to internalize 1-μm-diameter latex beads for 15 min; washed to remove noninternalized beads; and incubated for additional periods of 15, 45, and 75 min in StM (for total incubation times of 30, 60, and 90 min). Cells were then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence to detect p80 and H+-ATPase. The percentage of internalized beads found in PLs was determined. Thirty internalized beads were analyzed for each time point in each experiment. Beads were mostly found in lysosomes at 30 min and then gradually transferred to PLs. This transfer was slower in starved cells. (C) The percentage of cells exhibiting a surface p80-rich exocytic patch was determined before or after starvation in StM. Fewer p80-rich patches were found at the surfaces of starved cells, indicating a decrease in the fusion of PLs with the cell surface when cells were deprived of nutrients. The means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of results from four independent experiments are indicated. At least 300 cells were analyzed for each time point in each experiment. All curves show the means ± SEM of results from three independent experiments.

To visualize the transfer of endocytosed material in the endocytic pathway, we fed latex beads to the cells for 15 min, chased them for a variable time, and determined after immunofluorescence staining the fraction of beads having reached PLs. In rich HL5 medium, after 30 min (15 min of phagocytosis plus 15 min of chase), latex beads were virtually all found in lysosomes (Fig. 2B). They were then gradually transferred to PLs (Fig. 2B), as reported previously (13). In starved cells (90 min of preincubation in StM), the same general organization was conserved: latex beads were first observed in lysosomes and then in PLs, confirming that the overall organization of the endocytic pathway was unaffected by starvation. However, the lysosome-to-PL transfer was markedly slower than that observed in cells grown in rich medium (Fig. 2B).

Fusion of a PL with the cell surface results in the transient formation of a p80-rich domain at the cell surface (3), called an exocytic patch. Surface p80 patches can be counted to evaluate the fusion rate. In starved cells, we observed a small and transient increase in the number of exocytic patches, peaking after 5 min, followed by a slower but more pronounced decrease (Fig. 2C).

Together, these results indicate that the overall organization of the endocytic pathway is maintained in starved Dictyostelium cells. However, compared to those observed for cells growing in rich medium, the rates for all kinetic parameters tested (internalization, transfer of material between endocytic compartments, and PL exocytosis) were markedly lower in starved cells.

The large sizes of endocytic compartments allow these compartments to be counted in DH1 Dictyostelium cells. Upon starvation, the number and size of lysosomes did not vary significantly (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), but the number of PLs decreased significantly with time, while their sizes increased slightly (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material; also Table 1). The efficacy of fusion of individual PLs can be evaluated by comparing the number of exocytic patches to the number of PLs (5). The decrease in the number of exocytic events (Fig. 2C) was paralleled by a decrease in the number of secretory PLs (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), such that the rate of fusion of individual PLs with the cell surface did not vary significantly (Table 1). These results suggest that the decrease in exocytic events simply reflected the decrease in the number of fusion-competent PLs, presumably caused by the slower dynamics of the endocytic pathway.

Table 1.

Secretion of postlysosomes by wild-type, apm3, and lvsB cells

| Medium | Parameter | Value for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | apm3 mutant | lvsB mutant | ||

| HL5 | No. of PLsa | 2.54 ± 0.03 | 2.26 ± 0.04 | 1.35 ± 0.13 |

| % p80 patchesb | 6.52 ± 0.53 | 3.71 ± 0.43 | 4.19 ± 0.11 | |

| Fusion efficacyc | 2.57 | 1.64 | 3.10 | |

| StM | No. of PLs | 1.16 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.07 |

| % p80 patches | 3.27 ± 0.25 | 3.36 ± 0.42 | 2.56 ± 0.36 | |

| Fusion efficacy | 2.83 | 3.46 | 7.76 | |

Average number of PLs per cell ± SEM (n = 3).

Percentage of cells presenting a p80 patch.

The fusion efficacy (a.u.) was calculated by dividing the frequency of p80 patches by the number of PLs.

apm3 and lvsB mutant cells respond differently to starvation.

The ability to modulate the dynamics of the endocytic pathway may prove useful for the analysis of mutants exhibiting multiple defects in the endocytic pathway, such as the apm3 and lvsB mutants. Apm3 is the μ subunit of the AP-3 clathrin-associated adaptor complex (10), and LvsB is the Dictyostelium ortholog of the human LYST protein (23). In humans, alterations in genes encoding AP-3 or LYST are responsible for rare lysosomal diseases (Hermansky-Pudlak and Chediak-Higashi, respectively). AP-3 and LYST are involved in the biogenesis of lysosomes and lysosome-related organelles, but their exact mode of action remains to be established (12, 15). In Dictyostelium, apm3 and lvsB mutant cells exhibit a variety of phenotypic alterations compared to wild-type cells (4–6, 8, 14, 16): reduced endocytosis of the fluid phase (apm3), abnormal secretion of lysosomal enzymes (lvsB), enlarged lysosomes (lvsB), slower biogenesis of secretory PLs (apm3 and lvsB), abnormal composition of lysosomes and PLs (apm3), and a decrease in the rate of fusion of individual PLs to the cell surface (apm3). It is likely that only a few of these phenotypes are directly caused by the genetic alteration and that several are merely secondary consequences of this primary defect. However, it is not possible a priori to distinguish the primary from the secondary defects and thus to deduce from the mutant phenotype the primary role of the altered gene product. In order to gain further insight into the functions of these two gene products, we analyzed the structure and function of the endocytic pathway in starved apm3 and lvsB mutant cells.

When assessed by immunofluorescence, the general organization of apm3 and lvsB mutant cells was not found to be markedly affected upon starvation (data not shown), besides changes in the sizes of some compartments (see below). However, when the dynamics of the endocytic pathway were assessed, significant differences were observed.

When grown in rich medium, apm3 mutant cells exhibit reduced endocytosis of the fluid phase compared to wild-type cells (Table 2). However, upon starvation, the rate of fluid phase endocytosis decreased less in apm3 cells than in wild-type cells, and consequently, endocytosis was as efficient in starved apm3 and wild-type cells (Table 2). In rich medium, the biogenesis of PLs was also relatively slow in apm3 mutant cells, but it did not change upon starvation (Fig. 3A). The number of exocytic patches was also unchanged in apm3 mutant cells upon starvation (Table 1). However, the absolute number of PLs in apm3 mutant cells decreased upon starvation, as in wild-type cells (Table 1). Consequently, the rate of fusion of individual PLs with the cell surface was even higher in starved apm3 cells than in starved wild-type cells (Table 1).

Table 2.

Endocytosis of fluid phase by wild-type, apm3, and lvsB cells

| Medium | Valuea for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | apm3 mutant | lvsB mutant | |

| HL5 | 100 | 47.45 ± 11.23 | 100.11 ± 3.79 |

| StM | 15.73 ± 2.26 | 14.68 ± 4.30 | 26.06 ± 4.53 |

Values are expressed as percentages relative to endocytosis induced in HL5 by wild-type cells. Averages ± SEM of results from four independent experiments are indicated.

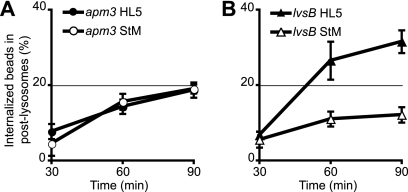

Fig. 3.

Lysosome maturation in apm3 and lvsB mutant cells is affected differentially by starvation. Lysosome maturation in apm3 and lvsB mutant cells was assessed as described in the legend to Fig. 2 for panel B. (A) The biogenesis of PLs is slower in apm3 cells than in wild-type cells, but it is unchanged upon starvation. (B) Lysosome maturation in lvsB cells is sensitive to starvation and slower than that observed in wild-type cells. Note that the scale is different from that used in Fig. 2B.

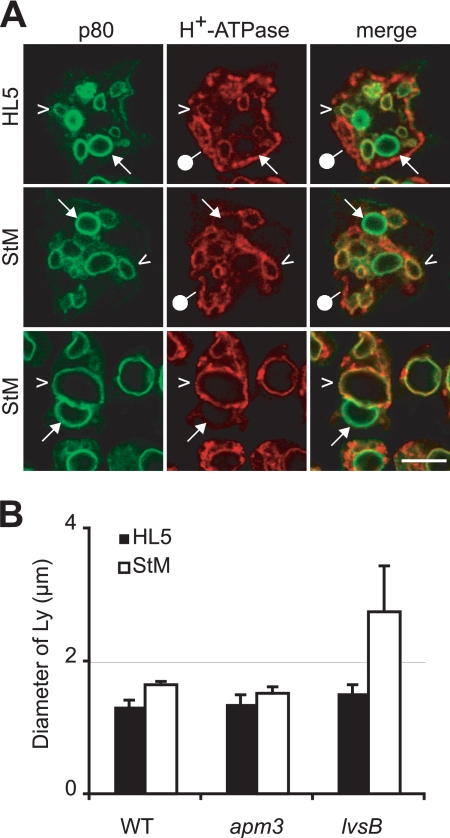

In rich medium, endocytosis of the fluid phase in lvsB mutant cells was identical to that in wild-type cells. However, upon starvation, endocytosis decreased less in lvsB than in wild-type cells, such that the rate of endocytosis in starved lvsB cells was roughly twice that in starved wild-type cells (Table 2). lvsB mutant cells grown in rich medium exhibited a slower transfer of endocytosed material from lysosomes to PLs, and this defect dramatically increased in starved cells (Fig. 3B). The increase in uptake, associated with a strong decrease in the transfer of material to PLs, was presumably responsible for the large increase in the sizes of lysosomal compartments under these conditions (Fig. 4). In some cells (15 to 60%, depending on individual experiments), this even resulted in the formation of one or two giant lysosomes filling up most of the cell volume (Fig. 4A). In lvsB cells, the number of exocytic events decreased less than in wild-type cells upon starvation (Table 1), and the fusion efficiency of individual PLs was even higher in starved lvsB than in wild-type cells (Table 1). Rather logically, the decreased rate of biogenesis of PLs, combined with a faster fusion with the cell surface, resulted in a very low number of PLs in starved lvsB cells (Table 1). The phenotypes of wild-type as well as apm3 and lvsB mutant cells are schematically summarized in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

Incubation in starvation medium affects the sizes of lysosomes in lvsB mutant cells. Wild-type, apm3, and lvsB cells were incubated in HL5 or StM for 4 h and processed for immunofluorescence to detect p80 and H+-ATPase. (A) Pictures of lvsB cells grown in rich medium (HL5) or starved in StM are shown. In lvsB cells, the sizes of lysosomes (p80 positive and H+-ATPase-positive; arrowheads) increased significantly upon starvation. In a fraction of starved cells, a single giant lysosome filled most of the cell (lower panel). Postlysosomes (p80 positive and H+-ATPase negative; arrows) and contractile vacuole (p80 negative and H+-ATPase positive; pinheads) are also indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) The sizes of lysosomes in cells grown in rich medium (HL5) or starved in StM were measured. The diameters of lysosomes were identical in wild-type (WT) and apm3 mutant cells, whereas starved lvsB cells exhibited bigger lysosomes.

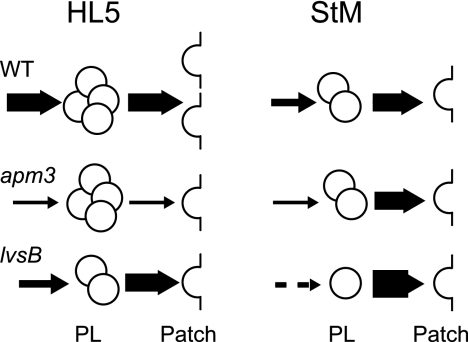

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of wild-type, apm3, and lvsB cell phenotypes in HL5 and starvation medium (StM). For each condition, the numbers of PLs and exocytic patches represented are roughly proportional to those actually measured. The thickness of each arrow is proportional to the efficiency of PL biogenesis or exocytosis. The values for many parameters (e.g., number of exocytic patches and efficiency of fusion of PLs with the cell surface) vary depending on the conditions. The only defect seen in both starved and unstarved lvsB or apm3 mutant cells in comparison to wild-type cells is the slower biogenesis of postlysosomes, suggesting that it is at this stage of intracellular transport that both proteins are primarily involved.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the effect of starvation on the structure and function of the endocytic pathway in Dictyostelium cells. Our study was limited to the first 4 h of starvation, i.e., before the appearance of major changes in cellular morphology and the induction of cell aggregation. Since most of the changes that we observed were detectable after 1 h of starvation, we expect that they largely reflect alterations in the regulation of the endocytic pathway rather than massive changes in the expression levels of individual proteins. In agreement with this view, our data suggest that the general organization of the endocytic pathway is maintained in starved Dictyostelium cells but that the values for several kinetic parameters are significantly altered. Uptake of the fluid phase, transfer from lysosomes to PLs, and exocytosis of PLs significantly slow down upon starvation. This study was conducted using the DH1 Dictyostelium strain, in which endosomal compartments and surface exocytic patches can easily be visualized and counted. Such detailed analysis could not be performed with AX2 cells, where endosomal compartments are much smaller. However, we observed a decrease of fluid phase uptake in starved AX2 cells similar to that seen in starved DH1 cells (data not shown), suggesting that the general slowdown of the endocytic pathway upon starvation occurs in a variety parental Dictyostelium strains.

We also analyzed the apm3 and lvsB strains, two mutants that were previously shown to affect the kinetics of the endocytic pathway in cells growing in rich medium (4, 5). Interestingly, these mutations caused different phenotypes in starved cells. Some phenotypes were seen under both conditions, and others were variable, depending on the conditions considered. The most persistent defect, seen in both apm3 and in lvsB mutant cells, was that biogenesis of PLs was slower than that observed in wild-type cells under all conditions. In contrast, fluid phase endocytosis, rates of fusion of PLs to the cell surface, and sizes and numbers of lysosomal and postlysosomal compartments varied considerably, depending on the conditions used. For example, in rich medium, fusion of individual PLs with the cell surface was less efficient in apm3 cells than in wild-type cells, but this defect disappeared in starved cells. One possible interpretation of such variations is that both AP-3 and LvsB are primarily involved in PL biogenesis but that they play different roles in this process (5). Other phenotypes observed in mutant cells presumably represent secondary consequences of these primary defects and vary when the dynamic configuration of the endocytic pathway is modified upon starvation.

The fact that some features of the endocytic pathway are influenced by the metabolic status of the cells may account for some differences between studies led by different groups. For example, we did not observe significantly bigger lysosomes in lvsB mutant cells than in wild-type cells, while bigger lysosomes were clearly seen by other investigators (14). Remarkably, in our cells and under our experimental conditions, the sizes of lysosomes increased tremendously in lvsB mutant cells upon starvation. The use of different parental strains (DH1-10 versus NC4A2) and of media with different compositions may thus explain these apparently conflicting results. Indeed, different parental strains do show different sensitivities to nutrients (7).

In summary, the ability to modify the dynamics of the endocytic pathway by starving cells provides a new tool for analyzing in more detail the role of specific gene products in the endocytic pathway. By distinguishing primary phenotypes caused by a mutation (seen under all conditions) from secondary alterations of the endocytic pathway (seen only under certain conditions), this may allow a better understanding of the organization and function of the endocytic pathway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The P.C. laboratory is supported by the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research (grant 31003A-120056), the Doerenkamp-Zbinden Foundation, and the E. Naef Foundation (FENRIV). S.J.C. received a fellowship from the Fondation Ernst et Lucie Schmidheiny.

We thank Thierry Soldati and Oliver Hartley for reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/cgi/content/full/9/3/387/DC1.

Published ahead of print on 22 January 2010.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Benghezal M., Gotthardt D., Cornillon S., Cosson P. 2001. Localization of the Rh50-like protein to the contractile vacuole in Dictyostelium. Immunogenetics 52:284–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caterina M. J., Milne J. L., Devreotes P. N. 1994. Mutation of the third intracellular loop of the cAMP receptor, cAR1, of Dictyostelium yields mutants impaired in multiple signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 269:1523–1532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charette S. J., Cosson P. 2006. Exocytosis of late endosomes does not directly contribute membrane to the formation of phagocytic cups or pseudopods in Dictyostelium. FEBS Lett. 580:4923–4928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Charette S. J., Cosson P. 2007. A LYST/beige homolog is involved in biogenesis of Dictyostelium secretory lysosomes. J. Cell Sci. 120:2338–2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charette S. J., Cosson P. 2008. Altered composition and secretion of lysosome-derived compartments in Dictyostelium AP-3 mutant cells. Traffic 9:588–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charette S. J., Mercanti V., Letourneur F., Bennett N., Cosson P. 2006. A role for adaptor protein-3 complex in the organization of the endocytic pathway in Dictyostelium. Traffic 7:1528–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cherix N., Froquet R., Charette S. J., Blanc C., Letourneur F., Cosson P. 2006. A Phg2-Adrm1 pathway participates in the nutrient-controlled developmental response in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:4982–4987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cornillon S., Dubois A., Bruckert F., Lefkir Y., Marchetti A., Benghezal M., De Lozanne A., Letourneur F., Cosson P. 2002. Two members of the beige/CHS (BEACH) family are involved at different stages in the organization of the endocytic pathway in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 115:737–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cornillon S., Pech E., Benghezal M., Ravanel K., Gaynor E., Letourneur F., Bruckert F., Cosson P. 2000. Phg1p is a nine-transmembrane protein superfamily member involved in dictyostelium adhesion and phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34287–34292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Chassey B., Dubois A., Lefkir Y., Letourneur F. 2001. Identification of clathrin-adaptor medium chains in Dictyostelium discoideum: differential expression during development. Gene 262:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dimond R. L., Burns R. A., Jordan K. B. 1981. Secretion of Lysosomal enzymes in the cellular slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 256:6565–6572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Pietro S. M., Dell'Angelica E. C. 2005. The cell biology of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: recent advances. Traffic 6:525–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gotthardt D., Warnatz H. J., Henschel O., Bruckert F., Schleicher M., Soldati T. 2002. High-resolution dissection of phagosome maturation reveals distinct membrane trafficking phases. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3508–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris E., Wang N., Wu Wl W. L., Weatherford A., De Lozanne A., Cardelli J. 2002. Dictyostelium LvsB mutants model the lysosomal defects associated with Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:656–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaplan J., De Domenico I., Ward D. M. 2008. Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kypri E., Schmauch C., Maniak M., De Lozanne A. 2007. The BEACH protein LvsB is localized on lysosomes and postlysosomes and limits their fusion with early endosomes. Traffic 8:774–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maniak M. 2003. Fusion and fission events in the endocytic pathway of Dictyostelium. Traffic 4:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marchetti A., Mercanti V., Cornillon S., Alibaud L., Charette S. J., Cosson P. 2004. Formation of multivesicular endosomes in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 117:6053–6059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mercanti V., Charette S. J., Bennett N., Ryckewaert J. J., Letourneur F., Cosson P. 2006. Selective membrane exclusion in phagocytic and macropinocytic cups. J. Cell Sci. 119:4079–4087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neuhaus E. M., Almers W., Soldati T. 2002. Morphology and dynamics of the endocytic pathway in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:1390–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neuhaus E. M., Horstmann H., Almers W., Maniak M., Soldati T. 1998. Ethane-freezing/methanol-fixation of cell monolayers: a procedure for improved preservation of structure and antigenicity for light and electron microscopies. J. Struct. Biol. 121:326–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ravanel K., de Chassey B., Cornillon S., Benghezal M., Zulianello L., Gebbie L., Letourneur F., Cosson P. 2001. Membrane sorting in the endocytic and phagocytic pathway of Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 80:754–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang N., Wu W. I., De Lozanne A. 2002. BEACH family of proteins: phylogenetic and functional analysis of six Dictyostelium BEACH proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. 86:561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.