Abstract

Overwhelming evidence supports the importance of the sympathetic nervous system in heart failure. In contrast, much less is known about the role of failing cholinergic neurotransmission in cardiac disease. By using a unique genetically modified mouse line with reduced expression of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) and consequently decreased release of acetylcholine, we investigated the consequences of altered cholinergic tone for cardiac function. M-mode echocardiography, hemodynamic experiments, analysis of isolated perfused hearts, and measurements of cardiomyocyte contraction indicated that VAChT mutant mice have decreased left ventricle function associated with altered calcium handling. Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR and Western blotting, and the results indicated that VAChT mutant mice have profound cardiac remodeling and reactivation of the fetal gene program. This phenotype was attributable to reduced cholinergic tone, since administration of the cholinesterase inhibitor pyridostigmine for 2 weeks reversed the cardiac phenotype in mutant mice. Our findings provide direct evidence that decreased cholinergic neurotransmission and underlying autonomic imbalance cause plastic alterations that contribute to heart dysfunction.

The role of sustained cholinergic tone in long-term cardiac function is poorly understood. Cardiac regulation by the parasympathetic nervous system is mediated primarily by acetylcholine (ACh) binding to the M2 muscarinic ACh receptor (M2-AChR) (12). In addition, cholinergic tone also controls sympathetic activity, as preganglionic neurotransmission is cholinergic in the two branches of the autonomic nervous system. Reduced parasympathetic function occurs during aging (11) and has been observed for patients with several disorders that ultimately affect cardiac function, such as heart failure (15), diabetes (29), and hypertension (13, 50). Moreover, excessive adrenergic activation in association with diminished parasympathetic activity is detrimental in cases of heart failure (35). Recent studies demonstrated that M2-AChR knockout (KO) mice exhibit impaired ventricular function and increased susceptibility to cardiac stress, suggesting a protective role of the parasympathetic nervous system in the heart (26). In support of this hypothesis, vagal stimulation has been shown to be of benefit in cases of heart failure (28). While most of these studies focus on possible protective actions of vagal activity and their relation to arrhythmogenesis, the mechanisms associated with the regulation of ventricular contractility by cholinergic neurotransmission are still unclear.

ACh-mediated signaling plays important roles in maintaining synaptic connections during development (5, 9, 32); hence, chronic disturbance of cholinergic tone, as observed in cases of dysautonomia, could contribute to altered myocardial function. Rich cholinergic innervations are found in the sinoatrial node (SAN), the atrial myocardium, the atrioventricular node, and the ventricular conducting system in many species (24). Although less abundant, parasympathetic fibers are also found throughout the ventricles, where stimulation of M2-AChR by ACh leads to L-type calcium channel inhibition and consequently reduced cardiomyocyte contractility (34).

Genetic disturbance of cholinergic neurotransmission in animal models is complicated, due to the requirement of ACh release to sustain motor function. Thus, the consequences of chronically reduced cholinergic neurotransmission for long-term cardiac function and molecular remodeling have not been studied in detail until now. Given the abundance of acetylcholine receptors, it is likely that genetic disturbance of individual receptors may not reveal all the consequences of decreased cholinergic tone. We have recently generated a mouse model of cholinergic dysfunction (VAChT knockdown, homozygous [VAChT KDHOM]) by targeting using homologous recombination for the vesicular ACh transporter (VAChT), a protein responsible for packaging ACh in secretory vesicles (41). VAChT KDHOM mice have an approximately 70% reduction in the levels of VAChT (41). Here, we used this unique mouse model to investigate whether long-term reduction of cholinergic neurotransmission affects cardiac physiology.

The present studies demonstrate that autonomic imbalance, due to chronic decrease of cholinergic neurotransmission in VAChT mutant mice, is associated with altered gene expression that underlies a heart dysfunction phenotype. Additionally, we show that enhancement of cholinergic activity is beneficial in improving cardiac alterations in VAChT mutant mice. Our findings provide novel insights on mechanisms and compensatory changes found in hearts subjected to prolonged alterations in autonomic regulation. These data support the notion that the cholinergic system is an important pharmacological target in heart failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal models and drug administration.

VAChT mutant mice (VAChT KDHOM) were described previously (41). VAChT mutant mice were generated by targeting the 5′ untranslated region of the VAChT gene by homologous recombination in a mixed 129S6/SvEvTac × C57BL/6J background and were backcrossed to C57BL/6Uni (from the University of Campinas) for 3 generations (N3), as further backcrossing into the C57BL/6 background caused infertility (data not shown). Heterozygous mice were intercrossed to generate the VAChT mutant and wild-type controls used in these experiments. Wild-type and mutant mice 1, 3, or 6 months old were used in this study for evaluation of cardiac function and myocyte Ca2+ transients. Pyridostigmine (PYR; Sigma) administration to mice was performed twice daily by intraperitoneal injection for two weeks (1 mg/kg body weight).

VAChT-null mice (VAChTdel/del), in which the VAChT open reading frame (ORF) was deleted by using Cre/loxP, were described previously (9). VAChTdel/del mice die shortly after birth due to respiratory failure; therefore, experiments were performed with embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5) embryos. VAChTwt/del mice were intercrossed to generate the VAChT-null mice.

Animals were housed in groups of three to five per cage in a temperature-controlled room with 12-h/12-h light/dark cycles in microisolator cages. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

Animals were maintained at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil, and at the University of Western Ontario in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals. Experiments were performed according to approved animal protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the UFMG and at the University of Western Ontario.

Hemodynamic measurements.

Invasive left ventricle (LV) hemodynamic measurements were made using a Millar Mikro-tip pressure transducer (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) as previously described (20, 33, 51). LV parameters, according to the blood pressure module in Chart analysis software (PowerLab; AD Instruments), were obtained at the baseline and following the administration of isoproterenol (ISO; 0.02 μg or 0.5 μg intraperitoneally [i.p.]) as previously described for anesthetized mice (17).

M-mode echocardiography.

Cardiac function under noninvasive conditions was assessed by two-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiography of halothane-anesthetized mice as previously described (2). Heart rates (HRs) recorded under this condition were 541.5 ± 21.4 beats per min (bpm) for the wild-type (WT) mice (8 mice), 520.2 ± 25.2 bpm for the VAChT KDHOM mice (5 mice), and 549.0 ± 23.4 bpm for the VAChT KDHOM mice with PYR (5 mice).

Electrocardiography.

A dorsally mounted radio frequency transmitter and wire leads (lead II configuration) were implanted subcutaneously under anesthesia. Chronic electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings from conscious mice were acquired with the Data Sciences International telemetry system (Transoma Medical, St. Paul, MN) as previously described (33). ECG recordings were initiated following a minimum of 7 days postimplantation. HR and HR variability (HRV) parameters were obtained and analyzed under basal (saline), atropine (1 mg/kg, i.p.), propranolol (1 mg/kg, i.p.), or atropine-plus-propranolol conditions by using the Dataquest A.R.T. software (Transoma Medical). The analysis for both HR and HRV was performed 15 min following administration of drugs.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and Ca2+ recordings.

Adult ventricular myocytes were freshly isolated and stored in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) until they were used (within 6 h) as previously described (21). Intracellular Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed with Fluo-4 AM (10 μM; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR)-loaded cardiomyocytes for 25 min, and these were subsequently washed with an extracellular solution that contained 1.8 mmol/liter Ca2+ to remove the excess dye. Cells were electrically stimulated at 1 Hz to produce steady-state conditions. The confocal line-scan imaging was performed with a Zeiss LSM 510META confocal microscope. The amplitude of the Ca2+ transient evoked by the application of a Ca2+- and Na+-free solution containing 10 mM caffeine was used as an indicator of the SR Ca2+ load (36). Cells were subjected to a series of preconditioning pulses (1 Hz) before caffeine was applied. Ca2+ spark frequencies in resting ventricular myocytes were recorded. Digital image processing was performed by using custom-devised routines created with the IDL programming language (Research Systems, Boulder, CO). The Ca2+ level was reported as F/F0 (or as ΔF/F0), where F0 is the resting Ca2+ fluorescence.

Langendorff preparation-perfused hearts.

Briefly, once removed from the animal, the heart was perfused with a Krebs-Ringer solution, which was delivered at 37°C with continuous gassing with 5% CO2 to yield a physiological pH of 7.4. Hearts were perfused with this solution for 50 min as previously described for mice and rats (6, 14).

Histological assessment of cardiac fibrosis.

In both WT and VAChT KDHOM groups, the fibrotic area in the LV and interventricular septum (IS) was evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining. Whole hearts were harvested, fixed in 10% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into sections 6 μm thick. Tissue sections were collected from atrial and ventricular regions, mounted on slides, and postfixed in Bouin's solution. After a series of xylene and alcohol washes were performed, slides were stained with Weigert's hematoxylin and Masson's trichrome staining solutions. Then, slides were subjected to increased concentrations of alcohol and xylene and mounted with Entellan.

Quantitative PCR.

For RNA purifications, tissues were grounded in a potter with a pestle with liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol. For quantitative PCR (qPCR), total RNA was treated with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After reverse transcription, the cDNA was subjected to qPCR on a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, CA) by using Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, CA). Briefly, amplification was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl containing 0.5 μM each primer, 10 μl of Power SYBR green master mix (2×), and 1 μl of cDNA. The PCRs were cycled 45 times after initial denaturation (95°C, 2 min) with the following parameters: 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. For each experiment, a nontemplate reaction was included as a negative control. In addition, the absence of DNA contaminants was assessed in reverse transcriptase-negative samples. Melting curve analysis of amplification products was performed by cooling the samples to 60°C and then increasing the temperature to 95°C at 0.1°C/s. The specificity of the PCRs was also confirmed by size verification of the amplicons in acrylamide gel. Relative quantification of gene expression was done with the 2−ΔΔCT method, using the β-actin gene expression to normalize the data. Sequences of primers used are available upon request.

Immunofluorescence.

Images were acquired with an Axiovert 200 M microscope coupled with the ApoTome system or a Leica SP5 confocal microscope to obtain optical sections of the tissue. Objectives used were 20× dry, 40× water immersion (1.2 numerical aperture [NA]), and 63× oil immersion (1.4 NA). Adult VAChT KDHOM and WT mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (70 and 10 mg/kg i.p., respectively) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 10 min, followed by an ice-cold solution of methanol containing 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 10 min. Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (10). Slices were incubated for 15 to 18 h with primary antibodies anti-VAChT (rabbit polyclonal, 1:250; Sigma Chemical Co., São Paulo, Brazil) and CHT1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:250; kindly provided by R. Jane Rylett, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada).

Immunofluorescence of adult ventricular cardiomyocytes was performed on cells fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and permeabilized with 0.5% saponin. Anti-α-actinin antibody (Sigma) was used at a dilution of 1:200. Secondary antibody-conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 543 (Molecular Probes) was used at a dilution of 1:1,000, and nuclear staining was performed using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in a dilution of 1:1,000. Cardiomyocyte cellular area in α-actinin-stained cells was measured.

Cardiomyocyte morphometry.

The mice were anesthetized with 10% ketamine-2% xylazine (4:3, 0.1 ml/100 g, i.p.), and heartbeat was stopped in diastole by using 10% KCl (intravenous [i.v.]). Hearts were placed in 4% Bouin's fixative for 24 h at room temperature. The tissues were dehydrated by sequential washes with 70, 80, 90, and 100% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Transversal sections (5 μm) were cut starting from base area of the heart at intervals of 40 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for cell morphometry. Tissue sections (2 from each animal) were examined with a light microscope (BX 41; Olympus) at ×400 magnification, photographed (Q Color 3; Olympus), and analyzed with ImageJ software. Only digitized images of cardiomyocytes cut longitudinally with nuclei and cellular limits visible were used for analysis (an average of 40 cardiomyocytes for each animal). The diameter of each myocyte was measured across the region corresponding to the nucleus.

Whole-heart morphometry.

Transversal heart sections (5 μm) were cut starting from base area of the heart at intervals of 40 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The area of cardiac mass was obtained by subtracting the left and right ventricle chamber areas from the total area of the heart and expressed as a percentage of the total area. Images with ×20 magnification were captured using a Q Color 3 camera (Olympus) to measure ventricular and total tissue areas.

Whole-cell patch clamp and action potential recordings.

An EPC-9.2 instrument (HEKA Electronics) was used to patch clamp single ventricular cardiomyocytes in whole-cell voltage and current clamp configurations, using specific protocols according to the ionic conductance evaluated (8, 36, 42). Measurements started 5 min after breaking into the cell in order to attain equilibrium between the pipette solution and the cell cytoplasm. For action potential (AP) recordings, the pipette solution consisted of 130 mmol/liter K-aspartate, 20 mmol/liter KCl, 10 mmol/liter HEPES, 2 mmol/liter MgCl2, 5 mmol/liter NaCl, and 5 mmol/liter EGTA (set to pH 7.2 with KOH). Modified Tyrode used as bath solution contained 140 mmol/liter NaCl, 5.4 mmol/liter KCl, 1 mmol/liter MgCl2, 1.8 mmol/liter CaCl2, 10 mmol/liter HEPES, and 10 mmol/liter glucose (set at pH 7.4). Current injections triggered action potentials at a constant rate (1 Hz).

For L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L) recordings, the pipette solution contained 120 mM CsCl, 20 mM tetraethylammonium chloride (TEACl), 5 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM EGTA (set to pH 7.2 with CsOH). The bath solution was modified Tyrode solution. ICa was elicited by depolarization steps from −40 to 50 mV for 300 ms from a holding potential of −80 mV at a frequency of 0.1 Hz and sample frequency of 10 kHz. To inactivate Na+ current (INa), we used a prepulse from −80 to −40 mV with a duration of 50 ms. β-Adrenergic stimulation of cells was produced by the addition of 100 nmol/liter isoproterenol to modified Tyrode solution for 3 min. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (23 to 26°C).

Western blotting.

Forty to 60 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE. Antibodies used were anti-SERCA2 and antiphospholamban (anti-PLN) (ABR), anti-phospho-PLN (Ser-16) (Upstate), anti-phospho-PLN (Thr-17) (Badrilla), anti-troponin I (TnI) and anti-phospho-TnI (Cell Signaling), and anti-α-tubulin (Sigma Chemical Co.). Immunodetection was carried out using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). Protein levels were expressed as ratios of optical densities. α-Tubulin was used as a control for any variations in protein loading.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM), and the numbers of cells or experiments (n) are shown. Significant differences between groups were determined with Student's t test or an analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Decreased cholinergic neurotransmission in VAChT KDHOM mice causes heart failure.

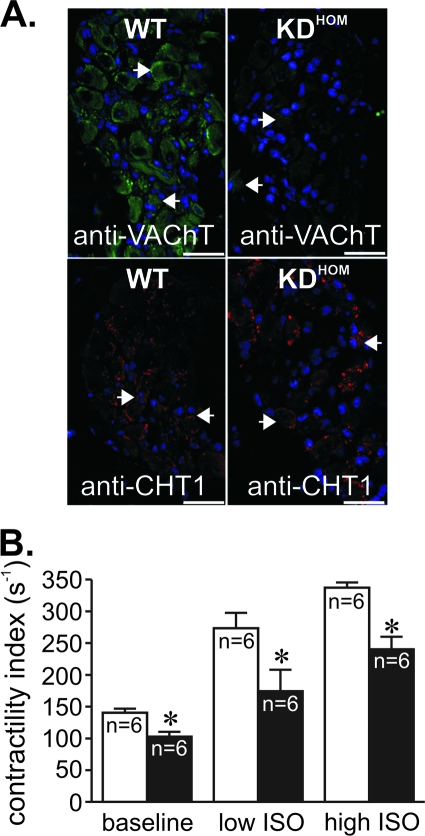

VAChT KDHOM mice have previously been shown to have reduced VAChT expression and altered ACh release (41; R. F. Lima, V. F. Prado, M. A. Prado, and C. Kushmerick, submitted for publication). In agreement with these previous observations, hearts from 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM mice had decreased VAChT immunoreactivity in intracardiac ganglia (Fig. 1A; arrowheads indicate some of the neuronal cell bodies) compared to the WT. In contrast, there was no decrease in immunoreactivity in VAChT KDHOM mouse nodal ganglia stained with an antibody against the high-affinity choline transporter (CHT1). These results confirm previous assessments of VAChT and CHT1 expression in VAChT KDHOM mice (10, 41). We have shown previously that a constitutively lack of cholinergic tone affects skeletal muscle function and ability to perform exercise in VAChT KDHOM mice (41). Moreover, the lack of VAChT in KO mice affects skeletal muscle development (9). In order to determine if the constitutive decrease in cholinergic tone could affect cardiomyocytes and, hence, heart physiology, we performed invasive hemodynamic assessments on anesthetized mice. These experiments revealed a reduced contractility index (maximum first derivative of the change in left ventricle pressure [dP/dt] divided by the LV pressure at the time of maximum dP/dt) in the hearts of 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM mice compared to that of WT controls (Fig. 1B). Peak left ventricle systolic pressure and the maximum rates of LV pressure rise and fall (peak +dP/dt and −dP/dt, respectively) were also significantly lower in VAChT mutants than in WT mice under baseline conditions (Table 1). Furthermore, an attenuated response to ISO by VAChT mutants was evident (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Although the absolute effect shows a decrease in the ISO-mediated response by VAChT mutants, the relative increases in contractility index were not significantly different between WT and VAChT mutants. In order to investigate the progression of cardiac dysfunction in VAChT mutants, we have also performed hemodynamic assessments of 1-month-old VAChT mutant mice. In contrast to 3-month-old mice according to the obtained data, younger mice did not show differences in the contractility index under either baseline (WT, 134 ± 22 s−1 [n = 4]; VAChT KDHOM, 135 ± 6 s−1 [n = 5]) or maximal ISO stimulation (WT, 251 ± 17 s−1 [n = 4]; VAChT KDHOM, 303 ± 24 s−1 [n = 5]) conditions. Therefore, all subsequent experiments were performed with 3-month-old mice.

FIG. 1.

VAChT mutant mice present heart failure. (A) VAChT and CHT1 immunoreactivity in neurons of adult WT and VAChT KDHOM mouse intracardiac ganglia. Note the reduction in immunofluorescence for VAChT. There was no decrease in immunoreactivity in nodal ganglia of VAChT KDHOM stained with an antibody against the high-affinity choline transporter (CHT1). Blue labeling corresponds to nuclei stained with DAPI that seem to predominantly label glial cells. Arrowheads indicate some of the neuronal cell bodies in the ganglia. Bar = 20 μm. (B) Left ventricle function (as assessed by contractility index) in VAChT KDHOM mice (black bars) and WT mice (white bars). VAChT mutant mouse hearts had decreased contractility indexes and lower absolute responses to ISO. n, number of mice; *, P value of <0.05 in comparison with the WT.

TABLE 1.

Hemodynamic parameters for WT and VAChT KDHOM mice under baseline and isoproterenol stimulation conditionsa

| Parameter | Baselineb |

Isoproterenolb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | VAChT KDHOM | WT | VAChT KDHOM | |

| HR (bpm) | 277 ± 26 | 240 ± 15 | 621 ± 22 | 509 ± 43* |

| LVSP (mm Hg) | 104.0 ± 2.4 | 86.2 ± 6.0* | 111.8 ± 10.9 | 90.7 ± 4.4 |

| LVEDP (mm Hg) | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 11.8 ± 2.4 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 7.5 ± 2.0* |

| +dP/dtmax (mm Hg/s) | 7,245 ± 388 | 4,640 ± 573* | 16,615 ± 866 | 10,798 ± 1,295* |

| −dP/dtmin (mm Hg/s) | 6,739 ± 478 | 4,591 ± 637* | 9,163 ± 436 | 6,448 ± 375* |

HR, heart rate; LVSP, left ventricle systolic pressure; LVEDP, left ventricle end diastolic pressure; +dP/dtmax, maximum first derivative of the change in left ventricle pressure; −dP/dtmin, minimum first derivative of the change in left ventricle pressure; *, P value of <0.05 in comparison to the wild-type value.

Values are means ± SEM (n = 6).

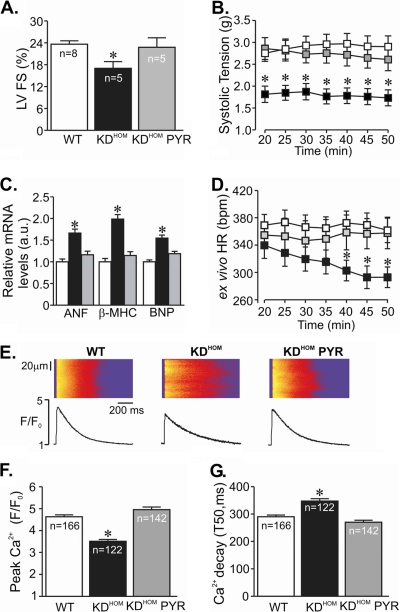

To ascertain the extension of cardiac dysfunction in 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM mice “in vivo,” we performed two-dimensional M-mode echocardiography. As shown in Fig. 2A, VAChT KDHOM mice displayed reduced left ventricle fractional shortening, consistent with the heart dysfunction illustrated in Fig. 1B. To further confirm that the decreased baseline fractional shortening was indeed the result of altered cholinergic function in vivo, we treated VAChT KDHOM mice for 2 weeks with a cholinesterase inhibitor, with the rationale that pharmacological restoration of ACh at synapses might rescue the phenotype and improve cardiac function in mutant mice. Administration of pyridostigmine for 2 weeks significantly increased fractional shortening of VAChT KDHOM mice toward control levels (Fig. 2A). To further assess directly the heart dysfunction in VAChT KDHOM mice without the complication of extensive regulation by the autonomic nervous system, we used the Langerdorff isolated heart preparation. In agreement with the results obtained with echocardiography studies, isolated hearts from VAChT KDHOM mice had significantly decreased systolic tension compared to WT hearts (Fig. 2B). Pyridostigmine treatment of animals for 2 weeks also reversed the decreased systolic tension in isolated VAChT KDHOM hearts measured in vitro. Similarly, a contractile dysfunction was observed in isolated adult ventricular cardiomyocytes from VAChT KDHOM mice, which demonstrated reduced fractional shortening compared to cardiomyocytes from WT mice (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Pyridostigmine treatment prevented cardiac dysfunction in VAChT KDHOM mice. (A) Echocardiography analysis of left ventricle fractional shortening (FS) in VAChT mutant mice (black bars) and WT mice (white bars). Note the significant improvement in left ventricle performance after pyridostigmine treatment (gray bars). n, number of mice. (B) Time course of systolic tension in isolated perfused hearts from WT (white squares; 15 hearts) and VAChT KDHOM (black squares; 16 hearts) mice. Pyridostigmine treatment improved systolic tension of hearts from mutant mice (gray squares; 4 hearts). (C) Gene expression of stress cardiac markers in cardiomyocytes from VAChT KDHOM mice and WT mice. The bar graph shows data from at least 5 independent experiments. a.u., arbitrary units. (D) The HR measured in ex vivo beating hearts from VAChT KDHOM mutants (black squares) was lower than that of WT hearts (white squares) after 40 min of perfusion. Pyridostigmine treatment for 2 weeks (gray squares) prevented the observed changes in HR. (E) (Top) Representative confocal images of electrically stimulated intracellular Ca2+ transient recordings in ventricular myocytes. (Bottom) Ca2+ transient line-scan profile. (F) Significant reduction in peak Ca2+ transient amplitude observed in freshly isolated adult VAChT KDHOM ventricular cardiomyocytes compared to the amplitude for WT mice. Pyridostigmine treatment significantly prevented intracellular Ca2+ dysfunction in VAChT KDHOM mice. n, number of ventricular cardiomyocytes analyzed. (G) Ca2+ transient kinetics of decay in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes and WT mice. Note that the observed changes in myocytes from VAChT KDHOM mice can be prevented by 2 weeks of pyridostigmine treatment. *, P value of <0.05 in comparison with WT and KDHOM PYR mice. T50, time from peak Ca2+ transient to 50% decay.

In agreement with the data showing heart dysfunction in VAChT KDHOM mice, transcripts encoding atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), markers of cardiac stress, were also upregulated in cardiomyocytes from VAChT mutants. These changes were reversed by pyridostigmine treatment, suggesting that they are triggered by reduced cholinergic neurotransmission (Fig. 2C).

One possible reason for the alteration in cardiac function in VAChT KDHOM mice might be related to an increase in blood pressure or HR. Contrary to this prediction, decreased cholinergic tone in VAChT KDHOM mice was associated with reduced arterial pressure (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material), with no significant alteration in basal HR using the tail-cuff system (715 ± 9 bpm for WT mice [n = 17] versus 698 ± 10 bpm for VAChT KDHOM mice [n = 16]). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in HR as determined by telemetry comparing WT and VAChT KDHOM mice (530 ± 45 bpm for WT mice [n = 3] versus 615 ± 26 bpm for KDHOM mice [n = 3]; P = 0.18). Additionally, HRs of VAChT KDHOM and WT mice under anesthesia were not significantly different (Table 1), and this contrasted with significantly reduced HRs recorded from ex vivo beating hearts from VAChT KDHOM mice compared to those from WT controls (Fig. 2D).

Importantly, heart dysfunction observed in VAChT mutant mice was not linked to cardiac fibrosis (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material) and hypertrophy. Instead, cardiac mass (Table 2), morphometric analyses of cross-sectional area (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material), and cellular area measurements (1,992.0 ± 78.5 μm2 cell area in WT mice [29 cells] versus 1,318.0 ± 60.4 μm2 in VAChT KDHOM mice [40 cells]; P < 0.05) indicated that both the heart and cardiomyocytes from VAChT mutant were significantly smaller than those of the WT mice at 3 months. However, it is possible that hypertrophy may develop or progress in mutant hearts as a result of depressed cholinergic drive with age. In fact, hearts from 6-month-old mutants presented more pronounced changes in cardiac structure characterized by concentric hypertrophy compared to age-matched controls (see Fig. S1E and F in the supplemental material). Taken together, these data suggest that VAChT mutants have progressive changes in cardiac mass. Herein, we focused our experiments on 3-month-old mice.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic parameters for WT and VAChT KDHOM micea

| Parameter | WT (n = 23)b | KDHOM (n = 26)b |

|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 24.26 ± 0.51 | 22.53 ± 0.36 |

| HW (mg) | 193.50 ± 4.82 | 177.30 ± 4.36 |

| HW/TL ratio (mg/mm) | 8.80 ± 0.25 | 7.96 ± 0.16 |

BW, body weight; HW, heart weight; HW/TL, heart weight/tibia length ratio.

Values are means ± SEM. The P values were <0.05 for all conditions in comparisons of the values for the wild-type and VAChT KDHOM mice.

Altered Ca2+ handling can influence cardiomyocyte physiology and changes in intracellular Ca2+ are a major feature in heart failure and myocyte pathology (3, 4). To determine if the heart dysfunction detected in VAChT KDHOM mice is related to changes in Ca2+ handling, we examined intracellular Ca2+ in freshly isolated Fluo-4 AM-loaded ventricular myocytes from 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM and WT mice. Figure 2E displays typical line-scan fluorescence images recorded from electrically stimulated ventricular myocytes. VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes developed significantly smaller and slower intracellular Ca2+ transients than WT cells. The amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was significantly reduced in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2F), and the kinetics of Ca2+ decay were significantly slower (Fig. 2G). These changes are closely related to the alteration in cholinergic tone in VAChT mutant mice, as Ca2+ handling is restored to normal levels in cells obtained from pyridostigmine-treated VAChT KDHOM mice. Hence, changes in intracellular calcium handling parallel alterations in cardiac function due to reduced cholinergic tone. Collectively, these results suggest a correlation between decreased cholinergic tone and heart dysfunction that can be recovered by cholinesterase inhibitor treatment.

Cardiomyocyte remodeling in VAChT KDHOM mice.

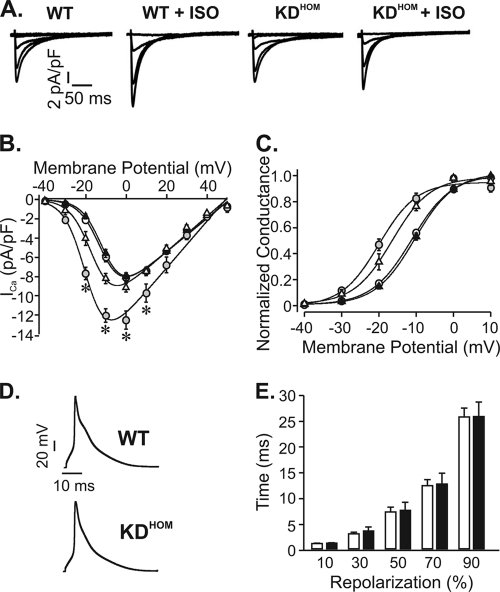

To investigate the cellular basis of the abnormal intracellular Ca2+ transient of failing VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes, electrical activity and expression levels of Ca2+ handling proteins were assessed by electrophysiology and Western blotting techniques, respectively. First, we investigated whether possible changes in ICa may play a role in the Ca2+ signaling dysfunction observed in VAChT KDHOM cardiac cells. Figure 3A shows sample ICa recordings. Virtually no difference between macroscopic ICa values recorded in VAChT KDHOM and WT cells was observed (at 0 mV, −8.10 ± 0.44 pA/pF in 12 WT cardiomyocytes versus −7.98 ± 0.39 pA/pF in 20 VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes) (Fig. 3B), suggesting that under basal conditions, Ca2+ currents of the two genotypes were identical. Activation of β1-adrenergic receptor increases ICa, and this is in part responsible for the adrenergic regulation of myocytes. Although we have not observed a significant change in ISO-mediated response in vivo, it is possible that at the cellular level, β-adrenergic responses are altered; therefore, we next evaluated ICa levels in myocytes exposed to ISO (100 nM). Figure 3A to C show that the ICa increase induced by ISO was much less prominent in VAChT KDHOM ventricular myocytes.

FIG. 3.

Electrical properties of VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes. (A) Sample ICa currents recorded from depolarizations from −40 mV to 0 mV. ISO (100 nmol/liter) significantly increased the magnitude of ICa in WT cells but not in VAChT KDHOM ventricular myocytes. (B) Average I-V relationships for ICa current density recorded from WT mice (open circles), WT mice with ISO (gray circles), VAChT KDHOM mice (black triangles), and VAChT KDHOM mice with ISO (open triangles). (C) Steady-state activation curves. (D) Sample action potential recordings from WT and VAChT KDHOM ventricular cardiomyocytes. (E) Action potential durations at 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90% repolarization. Fifteen cells from each experimental group were used. *, P value of <0.05 in comparison with WT mice.

Alterations in action potential profile may also contribute to dampening Ca2+ cycling in ventricular cells. To investigate this possible contribution, we recorded action potentials in ventricular myocytes from WT and VAChT KDHOM mice. No change between the action potential profiles of these cells was observed (Fig. 3D and E), indicating that electrical changes were not contributing to the Ca2+ signaling dysfunction observed in response to decreased cholinergic tone.

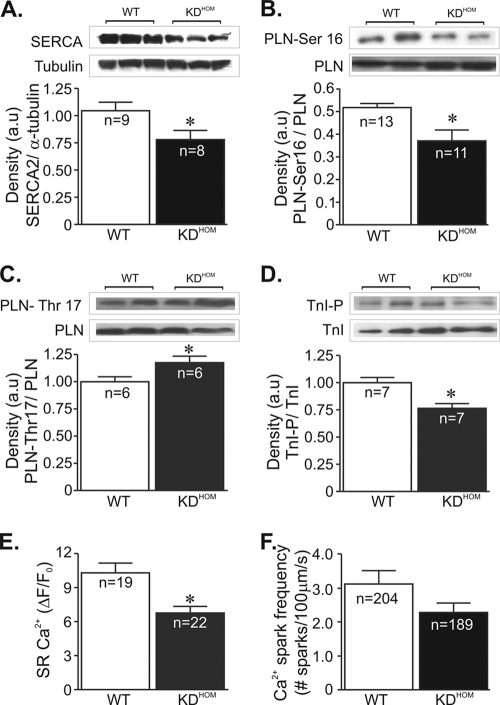

The slow decline of the Ca2+ transient in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes is consistent with the decreased expression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ pump (SERCA2); therefore, we examined SERCA2 levels in these hearts. A significant reduction in SERCA2 expression levels was observed in VAChT KDHOM hearts (Fig. 4A) compared to WT controls. In cardiac cells, PLN is the primary determinant of SERCA2 function. Therefore, we also investigated if there may be a change in PLN activity in VAChT KDHOM hearts by examining PLN expression/phosphorylation levels in these hearts. PLN expression was higher in VAChT KDHOM hearts (data not shown); however, as shown in Fig. 4B, phosphorylated-PLN levels at Ser-16, a key determinant of SERCA2 activity, were significantly reduced in these hearts. We have also assessed PLN phosphorylation levels at the CaMKII site (Thr-17). Phospho-Thr-17-PLN levels in VAChT KDHOM hearts were significantly increased compared to those in WT hearts (Fig. 4C). Another important aspect of cardiac cells is the sensitivity of the myofilaments to Ca2+. Since TnI phosphorylation desensitizes the myofilament to Ca2+, we next assessed TnI phosphorylation levels in cardiac samples. As shown in Fig. 4D, phospho-Ser-23/24-troponin I levels were significantly decreased in VAChT KDHOM hearts compared to WT hearts.

FIG. 4.

Ca2+ signaling components in VAChT KDHOM hearts. In panels A to D, the top image is a representative Western blot and the bottom shows an average densitometry graph (n, number of heart samples analyzed). (A) SERCA2 levels in VAChT KDHOM hearts were observed to be significantly reduced compared to levels in WT hearts. Phosphorylated-PLN levels at the protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent site (Ser-16) were lower in VAChT mutant hearts (B), while phospho-Thr-17-PLN levels were increased in these hearts (C). (D) Phospho-Ser-23/24-troponin I levels were decreased in VAChT mutant hearts relative to WT hearts. Tubulin expression levels were used as a loading control. (E) The SR Ca2+ content in ventricular cardiomyocytes from VAChT mutants was significantly reduced compared to that in WT cells. n, number of cells. (F) Ca2+ spark frequency showed a tendency to be lower in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes than in WT mice, but the difference was not statistically different. n, number of cells. *, P < 0.05.

Since the SERCA2/PLN ratio is altered in the VAChT KDHOM hearts, we next examined the possibility that this alteration may lead to a reduction of Ca2+ in the SR. Figure 4E shows a significant reduction in SR Ca2+ content in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, Ca2+ sparks were less frequent in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes than in WT mice (Fig. 4F), although the data just failed to reach statistical significance.

VAChT KDHOM mice show altered autonomic control of heart rate and G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) function.

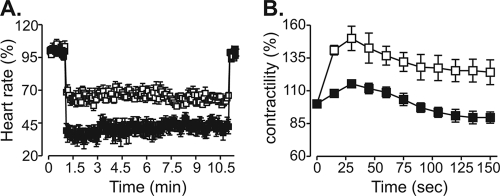

A chronic decrease in cholinergic tone in VAChT KDHOM mice appears to cause molecular cardiac remodeling with alterations in expression of genes related to cardiac stress, Ca2+ handling, and muscle contractility. Moreover, data from recordings of calcium currents suggested that β1-adrenergic receptor responses are altered in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes. To determine if decreased cholinergic tone, caused by reduced release of ACh in VAChT mutant mice, affected the responses to muscarinic and adrenergic activation, we treated Langendorff preparation-perfused hearts with ACh or ISO. As shown in Fig. 5A, hearts from VAChT KDHOM mice were much more sensitive to ACh (13 μmol/liter) than hearts from WT mice, and they showed enhanced bradycardia in response to this neurotransmitter. In contrast, the contractility response of ex vivo beating hearts from VAChT KDHOM mice to ISO (10 μmol/liter) was significantly attenuated (Fig. 5B), providing additional evidence of altered adrenergic response in mutant hearts.

FIG. 5.

VAChT KDHOM hearts present an altered GPCR response. (A) Percent decrease in beating frequency for WT (white squares; n = 4) and VAChT KDHOM (black squares; n = 4) hearts in response to 13 μmol/liter ACh. (B) Time course of mean percent force increase in WT (n = 5) and VAChT KDHOM (n = 5) perfused hearts in response to 10 μmol/liter ISO.

To examine the possibility of autonomic imbalance in 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM mice in vivo, we assessed the effects of muscarinic and adrenergic receptor blockades on HR and HR variability parameters. Administration of atropine did not significantly increase HRs in either WT (ΔHR, 56 ± 27 bpm) or VAChT KDHOM (ΔHR, 65 ± 28 bpm) mice, whereas propranolol administration significantly reduced the HR in VAChT KDHOM mice (ΔHR, −115 ± 27 bpm; P < 0.05) but not in WT mice (ΔHR, −78 ± 40 bpm). Interestingly, the coadministration of atropine and propranolol resulted in a significant reduction of HR in VAChT KDHOM mice (ΔHR, −87 ± 13 bpm; P < 0.05) but not in WT mice (ΔHR, −11 ± 4 bpm). These results would suggest that HR in VAChT KDHOM mice is under increased sympathetic control relative to HR in WT mice. To further investigate autonomic imbalance, we examined HRV parameters. Under baseline conditions, no significant differences in very low frequency (VLF) and low frequency (LF) power spectrum of HRV between WT and VAChT KDHOM mice were observed (data not shown). However, high-frequency (HF) power was significantly increased in VAChT KDHOM mice (HF, 3.66 ± 0.18 ms2; n = 3) compared to WT mice (HF, 1.98 ± 0.42 ms2; n = 3), which resulted in a significant difference between the LF/HF ratios of the genotypes (4.2 ± 0.6 for KDHOM mice [n = 3] versus 6.6 ± 0.5 for WT mice [n = 3]; P = 0.04). Atropine administration significantly reduced the LF/HF ratio in both WT (1.2 ± 0.5; n = 3) and VAChT KDHOM (1.6 ± 0.8; n = 3) mice, and these values were not different between genotypes. Interestingly, propranolol treatment did not significantly alter the LF/HF ratios relative to the baseline LF/HF ratios for either WT or VAChT KDHOM mice (data not shown). Lastly, the coadministration of atropine and propranolol significantly reduced the LF/HF ratios in both WT (2.1 ± 1.1; n = 3) and VAChT KDHOM (0.9 ± 0.5; n = 3) mice, and these values were not different between genotypes. Taken together, these experiments suggested the possibility that decreased cholinergic tone causes an imbalance of autonomic control of the heart, characterized by altered GPCR activation, with sympathetic tone in VAChT KDHOM mice being at a higher level than that in WT mice.

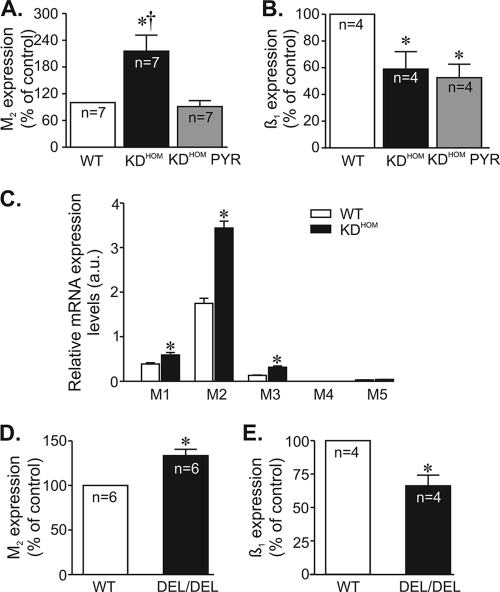

To determine the molecular basis of these changes in GPCR activation, we measured transcript expression levels of muscarinic and adrenergic receptors or associated proteins (such as GPCR kinases [GRKs]). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of RNA from heart tissue indicated that M2 muscarinic receptor levels were overexpressed (by 2-fold) in VAChT KDHOM hearts (Fig. 6A). In contrast, β1-adrenergic receptor transcripts were decreased by 41% in VAChT mutant hearts compared to the expression of WT controls (Fig. 6B). This reduction is consistent with attenuated magnitude of ISO-induced increment in ICa in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3B) and the reduced ISO response of VAChT mutants observed ex vivo (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, pharmacological restoration of ACh with pyridostigmine treatment for 2 weeks reversed the overexpression of M2 receptor message in VAChT KDHOM hearts, but it did not reverse the decrease in the levels of β1-adrenergic receptor message. Finally, we examined if we could detect transcripts for muscarinic receptors in isolated adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. We found an increase in M2 muscarinic receptors in cardiomyocytes similar to what we found in the whole heart, but we also found that M1 and M3 transcripts, which have been shown to have a role in inotropic responses (25, 45, 49), were also overexpressed in VAChT KDHOM mice (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Effect of VAChT deficiency on M2 muscarinic and β1-adrenergic receptor message levels. M2 muscarinic and β1-adrenergic receptor message levels were determined by qPCR. n, number of heart samples. (A) M2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in VAChT KDHOM hearts. (B) Significant reduction in β1-adrenergic receptor mRNA levels was observed in VAChT KDHOM hearts. Pyridostigmine treatment prevented the increase in M2 mRNA levels without affecting β1-adrenergic receptor mRNA expression levels in VAChT KDHOM hearts. (C) Determination of M1 to M5 mRNA expression levels by real-time quantitative PCR in ventricular cardiomyocytes from WT and VAChT KDHOM mice. Significant levels of M1 to M3 transcripts were detected in cardiomyocytes from WT mice. M1, M2, and M3 muscarinic receptor transcript levels were upregulated in VAChT KDHOM cardiomyocytes. The bar graph represents data from at least 6 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (D and E) Increased M2 and reduced β1-adrenergic receptor transcript messages are observed in hearts of VAChT knockout mice. *, P value of <0.05 in comparison with the WT; †, P value of <0.05 in comparison with KDHOM mice treated with PYR. n, number of heart samples analyzed.

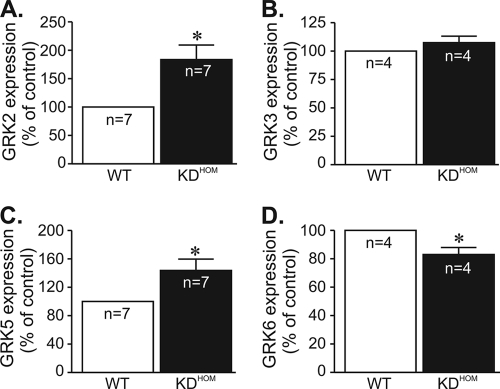

To further confirm if reduced ACh release could alter GPCR message levels, we measured M2 and β1 receptor messages in recently developed VAChT KO mice (VAChTdel/del [9]). Homozygous VAChT KO mice are unable to release acetylcholine in response to depolarization and died shortly after birth due to respiratory failure (9). We examined hearts from embryos (day 18.5) of VAChTdel/del mice and found that they recapitulate the molecular changes in GPCRs levels found in adult VAChT KDHOM mice, i.e., mRNA levels of M2 muscarinic receptors were significantly increased, while the mRNA levels of β1-adrenergic receptors were decreased in VAChTdel/del mice compared to the WT (Fig. 6D and E). Thus, in two distinct strains of mutant mice with altered expression of VAChT, we detected similar gene expression patterns of GPCRs. Alterations in GRK expression levels have the potential to affect GPCR-stimulated biological responses, and GRKs have been shown to be altered in heart failure (40). Therefore, we measured GRK message levels in hearts of VAChT KDHOM mice, with particular attention to GRKs that have been previously shown to phosphorylate β-adrenergic or M2 receptors and participate in receptor desensitization. The message of GRK2, the most-expressed GRK in cardiac tissue, was increased in VAChT KDHOM hearts compared to WT controls (by 84%). We also observed a significant increase in GRK5 message levels (by 44%), whereas GRK3 levels were not altered in VAChT KDHOM hearts. Moreover, GRK6 expression levels in VAChT KDHOM hearts were reduced by 17% compared to those in WT hearts. Figure 7 summarizes these data. Hence, the alteration in receptor responses may reflect a combination of receptor and GRK changes in hearts of VAChT mutants.

FIG. 7.

GRK message expression levels are altered in VAChT mutant hearts. Determination of GRK2 (A), GRK3 (B), GRK5 (C), and GRK6 (D) mRNA expression by real-time quantitative PCR. n, number of hearts analyzed. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we present evidence that chronic disturbance in cholinergic tone in mutant mice causes changes in cardiac gene expression associated with a molecular remodeling with altered intracellular calcium handling and decreased ventricular function. The dysautonomy due to decreased VAChT expression causes pronounced alterations in autonomic receptor function, with attenuated β1-receptor responses, whereas M2 responses seem exacerbated. Moreover, the cardiac phenotype of VAChT KDHOM mice could be reversed by treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor, pyridostigmine. These data suggest that cholinergic transmission might have unanticipated roles in maintaining ventricular cardiac contractility and that decreased cholinergic tone may contribute to cardiac dysfunction.

Clinical studies have shown that withdrawal of parasympathetic tone precedes sympathetic activation during the development of heart failure (1). For humans, spectral analysis suggests that aging, one of the major risk factors for heart failure, decreases parasympathetic drive (11). Animal studies further corroborated these data by showing autonomic imbalance in the early stage of experimental heart failure in dogs (22). Thus, dysautonomy plays important roles in pathological changes in the heart (37). However, given that genetic interference in the presynaptic cholinergic system is usually fatal, it has been difficult to chronically disturb the cholinergic autonomic nervous system to understand if acetylcholine plays any unanticipated roles in cardiac contractility.

VAChT presence in synaptic vesicles is fundamental for evoked release of ACh, as VAChT KO mice cannot release this neurotransmitter (9), and the VAChT KDHOM mice, which present reduced VAChT expression, show reduced ACh packing in synaptic vesicles (41). It is likely that both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are affected in VAChT KDHOM mice, since both depend on preganglionic cholinergic neurotransmission, albeit the parasympathetic nervous system should be hit twice due to its postganglionic cholinergic phenotype. We favor the possibility that dysautonomy caused by decreased cholinergic tone results in imbalance of autonomic control of the heart in mutant mice, based on the following evidence. First, it is known that at room temperature (25°C), the sympathetic drive predominates in mice and keeps their heart rate high (18). We found that heart rates were identical in the two genotypes despite a substantial decrease in β1-receptor expression and function in VAChT KDHOM mice, suggesting that in vivo, the sympathetic nervous system needed to be overactivated in VAChT KDHOM mice in order to maintain the basal HR at levels that were similar to those of the WT. Second, the changes in β1-receptor expression and GRKs observed for VAChT KDHOM mice are similar to those seen in models of adrenergic overactivation (19, 39). Third, the effect of sympathetic blockade on changes in HR responses were significantly enhanced in VAChT KDHOM mice, suggesting an important sympathetic component to maintenance of normal values of heart rate in the mutant mice. It is therefore conceivable that dysautonomy caused by reduced cholinergic function in VAChT mutants favors an increased sympathetic tone in these mice. The HR variability analysis conducted here supports this conclusion.

An intriguing observation is the reduced heart rate found in Langerdorff preparation-perfused hearts of mutant mice. This finding agrees with the results of autonomic blockage in vivo showing a reduced intrinsic heart rate in VAChT KDHOM mice. It is likely that these results reflect reduced sinoatrial node action potential firing in mutant mice. Future studies will be needed to determine the ionic and molecular bases of these changes.

Our findings contrast in part with the results obtained with another model of cholinergic dysfunction, the M2-AChR knockout mice (26). In spite of the similar in vivo HRs of the VAChT KDHOM and M2-AChR knockout mice compared to their respective controls, these two mouse strains presented distinct degrees of cardiac dysfunction and remodeling. Since most of the major cardiac changes observed in VAChT KDHOM mice can be attributed to the reduced cholinergic tone, it seems reasonable to have expected that the same array of changes would be observed in the M2-AChR knockout mice. One potential explanation for these phenotypic distinctions is the degree of activation of β-adrenergic and muscarinic signaling. Whereas β-adrenergic responses were significantly altered in VAChT mutants, this signaling pathway was preserved in M2-AChR knockout mice (26). Moreover, VAChT mice presented exacerbated M2 responses, in contrast to M2-AChR knockout mice, in which M2 responses were absent (26). There is another consideration: the existence of other types of muscarinic receptors in the heart, albeit with lower levels of expression, has been reported (44, 49). Indeed, we could also detect M1 and M3 muscarinic receptor messages in ventricular cardiomyocytes, and their expression was elevated in VAChT KDHOM mice. It is surprising that M2, M1, and M3 receptors are all upregulated in ventricular myocytes from VAChT mutants, even though parasympathetic fibers are not abundant in ventricles of rodents (30). Therefore, ACh may control ventricular cell function by mechanisms that are not characterized yet, and disturbance of VAChT expression can interfere with ventricular function. In fact, the possibility that cardiomyocytes express presynaptic cholinergic proteins has been raised recently (23).

It is well established that acetylcholine controls atrial function, with predominant roles in maintaining heart rate and action potential conduction. Unexpectedly, we found that altered cholinergic tone also provokes profound effects on ventricular cardiomyocytes. The array of cellular changes included Ca2+ signaling dysfunction and altered GPCR function. Interestingly, these changes occurred without altering ICa density or action potential properties. Overall, the cardiac remodeling observed for VAChT mutant mice resembles in many aspects the remodeling process observed for animal models of heart failure with sympathetic overdrive (7, 19, 39). Therefore, we suggest that the autonomic imbalance in the sympathetic direction in VAChT mutants, with decreased parasympathetic activity, can largely explain the development of ventricular dysfunction in these mice.

It is not clear at the moment if the overexpression of M2 muscarinic receptors contributes to the VAChT cardiac phenotype. We found that hearts from VAChT mutants were more sensitive to the bradycardic effects of ACh, suggesting the presence of increased functional M2 receptors in these hearts. It is well known that M2 receptors couple to the Gi/0 family of G proteins (27) to inhibit adenylyl cyclase; therefore, it is likely that M2 overexpression may also contribute to the impaired β1 response in VAChT mutant hearts. Consistent with this notion, improvement in ventricular function following pyridostigmine treatment of VAChT mice occurred in spite of reduced β1-receptor mRNA levels. It remains to be determined if attenuation of β1-adrenergic receptor mRNA in this model is a late event that may require more-prolonged pyridostigmine treatment. Levels of GRK2 are elevated in different models of heart failure characterized by enhanced chronic neurohumoral stimulation, in which they contribute to β1-adrenergic receptor attenuation (39). Consistent with this notion, we found increased GRK2 levels in the VAChT mutant model of cholinergic deficiency. Our results also demonstrated an upregulation of GRK5 in VAChT mutant hearts. Recently, Martini and collaborators (31) have characterized a new role for GRK5 as a nuclear histone deacetylase (HDAC) kinase with a key role in maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy. In this context, nuclear accumulation of GRK5 correlates with enhanced ventricular expression of the hypertrophy-associated fetal gene program (31). It is interesting that 3-month-old VAChT KDHOM mice had no sign of cardiac hypertrophy, although they showed increased levels of ANF and β-MHC transcripts. However, it is important to mention that ventricular expression of these markers is not always associated with cardiac hypertrophy (38, 48). In contrast, 6-month-old mice presented concentric hypertrophy, suggesting that cardiac dysfunction is progressive in VAChT mutant hearts as a result of chronic depressed cholinergic drive with age. It remains to be determined whether aged VAChT KDHOM mice will present further features of heart failure. Another critical aspect of cardiac dysfunction in heart failure is ventricular dyssynchrony. In fact, ventricular dyssynchrony has been shown to have deleterious effects on cardiac function resulting in contractile inefficiency and increased mortality (46). It remains to be determined whether VAChT KDHOM mice present ventricular dyssynchrony.

Taken together, our experiments indicate that dysautonomy causes profound changes in gene expression, suggesting that the balanced long-term responses of GPCRs are fundamental to maintain cardiac gene expression to maintain normal heart function. Our data also add to recent evidence suggesting that therapies aimed at enhancing parasympathetic activation may have positive effects on patients with heart failure (16, 43, 47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sanda Raulic and Jue Fan for mouse husbandry and genotyping at the University of Western Ontario, Richard Premont and Raul Gainetdinov (Duke University Medical Center) for advice on GRK PCR, and Brian Collier (McGill University) and R. Jane Rylett (University of Western Ontario) for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (grant NA 6656 to R.G., S.G., V.F.P., and M.A.M.P.), CIHR (grants MOP-82756 to R.G. and MOP-89919 to V.F.P. and M.A.M.P.), NIH-Fogarty grant R21 TW007800-02 (to M.A.M.P., V.F.P., and M.G.C.), PRONEX-FAPEMIG (to M.A.M.P., V.F.P., and S.G.), CNPq (to S.G., J.S.C., V.F.P., and M.A.M.P.), FAPEMIG, and Instituto do Milenio Toxins/MCT (to M.V.G., M.A.M.P., V.F.P., A.P.A., and S.G.). R.P. and C.A.S.M. received postdoctoral fellowships from the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Canada). R.G. is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amorim, D. S., H. J. Dargie, K. Heer, M. Brown, D. Jenner, E. G. Olsen, P. Richardson, and J. F. Goodwin. 1981. Is there autonomic impairment in congestive (dilated) cardiomyopathy? Lancet i:525-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartholomeu, J. B., A. S. Vanzelli, N. P. Rolim, J. C. Ferreira, L. R. Bechara, L. Y. Tanaka, K. T. Rosa, M. M. Alves, A. Medeiros, K. C. Mattos, M. A. Coelho, M. C. Irigoyen, E. M. Krieger, J. E. Krieger, C. E. Negrao, P. R. Ramires, S. Guatimosim, and P. C. Brum. 2008. Intracellular mechanisms of specific beta-adrenoceptor antagonists involved in improved cardiac function and survival in a genetic model of heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45:240-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers, D. M. 2006. Altered cardiac myocyte Ca regulation in heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 21:380-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers, D. M. 2002. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415:198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandon, E. P., W. Lin, K. A. D'Amour, D. P. Pizzo, B. Dominguez, Y. Sugiura, S. Thode, C. P. Ko, L. J. Thal, F. H. Gage, and K. F. Lee. 2003. Aberrant patterning of neuromuscular synapses in choline acetyltransferase-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 23:539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro, C. H., R. A. Santos, A. J. Ferreira, M. Bader, N. Alenina, and A. P. Almeida. 2005. Evidence for a functional interaction of the angiotensin-(1-7) receptor Mas with AT1 and AT2 receptors in the mouse heart. Hypertension 46:937-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakir, K., S. K. Daya, T. Aiba, R. S. Tunin, V. L. Dimaano, T. P. Abraham, K. M. Jaques-Robinson, E. W. Lai, K. Pacak, W. Z. Zhu, R. P. Xiao, G. F. Tomaselli, and D. A. Kass. 2009. Mechanisms of enhanced beta-adrenergic reserve from cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation 119:1231-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz, J. S., and H. Matsuda. 1994. Depressive effects of arenobufagin on the delayed rectifier K+ current of guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 266:317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Castro, B. M., X. De Jaeger, C. Martins-Silva, R. D. Lima, E. Amaral, C. Menezes, P. Lima, C. M. Neves, R. G. Pires, T. W. Gould, I. Welch, C. Kushmerick, C. Guatimosim, I. Izquierdo, M. Cammarota, R. J. Rylett, M. V. Gomez, M. G. Caron, R. W. Oppenheim, M. A. Prado, and V. F. Prado. 2009. The vesicular acetylcholine transporter is required for neuromuscular development and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:5238-5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Castro, B. M., G. S. Pereira, V. Magalhaes, J. I. Rossato, X. De Jaeger, C. Martins-Silva, B. Leles, P. Lima, M. V. Gomez, R. R. Gainetdinov, M. G. Caron, I. Izquierdo, M. Cammarota, V. F. Prado, and M. A. Prado. 2009. Reduced expression of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter causes learning deficits in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 8:23-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Meersman, R. E., and P. K. Stein. 2007. Vagal modulation and aging. Biol. Psychol. 74:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhein, S., C. J. van Koppen, and O. E. Brodde. 2001. Muscarinic receptors in the mammalian heart. Pharmacol. Res. 44:161-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duprez, D. A. 2008. Cardiac autonomic imbalance in pre-hypertension and in a family history of hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51:1902-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira, A. J., T. L. Oliveira, M. C. Castro, A. P. Almeida, C. H. Castro, M. V. Caliari, E. Gava, G. T. Kitten, and R. A. Santos. 2007. Isoproterenol-induced impairment of heart function and remodeling are attenuated by the nonpeptide angiotensin-(1-7) analogue AVE 0991. Life Sci. 81:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Floras, J. S. 1993. Clinical aspects of sympathetic activation and parasympathetic withdrawal in heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 22:72A-84A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeling, J., K. Wattier, C. LaCroix, and Y. F. Li. 2008. Neostigmine and pilocarpine attenuated tumour necrosis factor alpha expression and cardiac hypertrophy in the heart with pressure overload. Exp. Physiol. 93:75-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funakoshi, H., T. Kubota, N. Kawamura, Y. Machida, A. M. Feldman, H. Tsutsui, H. Shimokawa, and A. Takeshita. 2002. Disruption of inducible nitric oxide synthase improves beta-adrenergic inotropic responsiveness but not the survival of mice with cytokine-induced cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 90:959-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehrmann, J., P. E. Hammer, C. T. Maguire, H. Wakimoto, J. K. Triedman, and C. I. Berul. 2000. Phenotypic screening for heart rate variability in the mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 279:H733-H740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grassi, G., G. Seravalle, F. Quarti-Trevano, and R. Dell'oro. 2009. Sympathetic activation in congestive heart failure: evidence, consequences and therapeutic implications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 7:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gros, R., X. You, L. L. Baggio, M. G. Kabir, A. M. Sadi, I. N. Mungrue, T. G. Parker, Q. Huang, D. J. Drucker, and M. Husain. 2003. Cardiac function in mice lacking the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Endocrinology 144:2242-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guatimosim, S., E. A. Sobie, C. J. dos Santos, L. A. Martin, and W. J. Lederer. 2001. Molecular identification of a TTX-sensitive Ca(2+) current. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280:C1327-C1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishise, H., H. Asanoi, S. Ishizaka, S. Joho, T. Kameyama, K. Umeno, and H. Inoue. 1998. Time course of sympathovagal imbalance and left ventricular dysfunction in conscious dogs with heart failure. J. Appl. Physiol. 84:1234-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kakinuma, Y., T. Akiyama, and T. Sato. 2009. Cholinoceptive and cholinergic properties of cardiomyocytes involving an amplification mechanism for vagal efferent effects in sparsely innervated ventricular myocardium. FEBS J. 276:5111-5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent, K. M., S. E. Epstein, T. Cooper, and D. M. Jacobowitz. 1974. Cholinergic innervation of the canine and human ventricular conducting system. Anatomic and electrophysiologic correlations. Circulation 50:948-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korth, M., V. K. Sharma, and S. S. Sheu. 1988. Stimulation of muscarinic receptors raises free intracellular Ca2+ concentration in rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 62:1080-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaCroix, C., J. Freeling, A. Giles, J. Wess, and Y. F. Li. 2008. Deficiency of M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors increases susceptibility of ventricular function to chronic adrenergic stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 294:H810-H820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanzafame, A. A., A. Christopoulos, and F. Mitchelson. 2003. Cellular signaling mechanisms for muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Receptors Channels 9:241-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, M., C. Zheng, T. Sato, T. Kawada, M. Sugimachi, and K. Sunagawa. 2004. Vagal nerve stimulation markedly improves long-term survival after chronic heart failure in rats. Circulation 109:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd-Mostyn, R. H., and P. J. Watkins. 1975. Defective innervation of heart in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Br. Med. J. 3:15-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mabe, A. M., J. L. Hoard, M. M. Duffourc, and D. B. Hoover. 2006. Localization of cholinergic innervation and neurturin receptors in adult mouse heart and expression of the neurturin gene. Cell Tissue Res. 326:57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martini, J. S., P. Raake, L. E. Vinge, B. DeGeorge, Jr., J. K. Chuprun, D. M. Harris, E. Gao, A. D. Eckhart, J. A. Pitcher, and W. J. Koch. 2008. Uncovering G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 as a histone deacetylase kinase in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:12457-12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misgeld, T., R. W. Burgess, R. M. Lewis, J. M. Cunningham, J. W. Lichtman, and J. R. Sanes. 2002. Roles of neurotransmitter in synapse formation: development of neuromuscular junctions lacking choline acetyltransferase. Neuron 36:635-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mungrue, I. N., R. Gros, X. You, A. Pirani, A. Azad, T. Csont, R. Schulz, J. Butany, D. J. Stewart, and M. Husain. 2002. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of iNOS in mice results in peroxynitrite generation, heart block, and sudden death. J. Clin. Invest. 109:735-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata, K., C. Ye, M. Jain, D. S. Milstone, R. Liao, and R. M. Mortensen. 2000. Galpha(i2) but not Galpha(i3) is required for muscarinic inhibition of contractility and calcium currents in adult cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 87:903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okoshi, K., M. Nakayama, X. Yan, M. P. Okoshi, A. J. Schuldt, M. A. Marchionni, and B. H. Lorell. 2004. Neuregulins regulate cardiac parasympathetic activity: muscarinic modulation of beta-adrenergic activity in myocytes from mice with neuregulin-1 gene deletion. Circulation 110:713-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira, F. A., S. Guatimosim, C. H. Castro, D. T. Galan, S. Lauton-Santos, A. M. Ribeiro, A. P. Almeida, and J. S. Cruz. 2007. Abolition of reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in hearts from thiamine-deficient rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293:H394-H401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olshansky, B., H. N. Sabbah, P. J. Hauptman, and W. S. Colucci. 2008. Parasympathetic nervous system and heart failure: pathophysiology and potential implications for therapy. Circulation 118:863-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandya, K., H. S. Kim, and O. Smithies. 2006. Fibrosis, not cell size, delineates beta-myosin heavy chain reexpression during cardiac hypertrophy and normal aging in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16864-16869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penela, P., C. Murga, C. Ribas, A. S. Tutor, S. Peregrin, and F. Mayor, Jr. 2006. Mechanisms of regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 69:46-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrofski, J. A., and W. J. Koch. 2003. The beta-adrenergic receptor kinase in heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 35:1167-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prado, V. F., C. Martins-Silva, B. M. de Castro, R. F. Lima, D. M. Barros, E. Amaral, A. J. Ramsey, T. D. Sotnikova, M. R. Ramirez, H. G. Kim, J. I. Rossato, J. Koenen, H. Quan, V. R. Cota, M. F. Moraes, M. V. Gomez, C. Guatimosim, W. C. Wetsel, C. Kushmerick, G. S. Pereira, R. R. Gainetdinov, I. Izquierdo, M. G. Caron, and M. A. Prado. 2006. Mice deficient for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter are myasthenic and have deficits in object and social recognition. Neuron 51:601-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rota, M., T. Hosoda, A. De Angelis, M. L. Arcarese, G. Esposito, R. Rizzi, J. Tillmanns, D. Tugal, E. Musso, O. Rimoldi, C. Bearzi, K. Urbanek, P. Anversa, A. Leri, and J. Kajstura. 2007. The young mouse heart is composed of myocytes heterogeneous in age and function. Circ. Res. 101:387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serra, S. M., R. V. Costa, R. R. Teixeira De Castro, S. S. Xavier, and A. C. Nobrega. 2009. Cholinergic stimulation improves autonomic and hemodynamic profile during dynamic exercise in patients with heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 15:124-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma, V. K., H. M. Colecraft, L. E. Rubin, and S. S. Sheu. 1997. Does mammalian heart contain only the M2 muscarinic receptor subtype? Life Sci. 60:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma, V. K., H. M. Colecraft, D. X. Wang, A. I. Levey, E. V. Grigorenko, H. H. Yeh, and S. S. Sheu. 1996. Molecular and functional identification of m1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 79:86-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spragg, D. D., and D. A. Kass. 2006. Pathobiology of left ventricular dyssynchrony and resynchronization. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 49:26-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thayer, J. F., and R. D. Lane. 2007. The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biol. Psychol. 74:224-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vikstrom, K. L., T. Bohlmeyer, S. M. Factor, and L. A. Leinwand. 1998. Hypertrophy, pathology, and molecular markers of cardiac pathogenesis. Circ. Res. 82:773-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Z., H. Shi, and H. Wang. 2004. Functional M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in mammalian hearts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 142:395-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, J. S., F. H. Lu, Y. C. Yang, T. S. Lin, J. J. Chen, C. H. Wu, Y. H. Huang, and C. J. Chang. 2008. Epidemiological study on the effect of pre-hypertension and family history of hypertension on cardiac autonomic function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51:1896-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang, L. L., R. Gros, M. G. Kabir, A. Sadi, A. I. Gotlieb, M. Husain, and D. J. Stewart. 2004. Conditional cardiac overexpression of endothelin-1 induces inflammation and dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Circulation 109:255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.