Abstract

Highly pathogenic A/H5N1 avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) viruses have seriously affected the Nigerian poultry industry since early 2006. Previous studies have identified multiple introductions of the virus into Nigeria and several reassortment events between cocirculating lineages. To determine the spatial, evolutionary, and population dynamics of the multiple H5N1 lineages cocirculating in Nigeria, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of whole-genome sequences from 106 HPAI H5N1 viruses isolated between 2006 and 2008 and representing all 25 Nigerian states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) reporting outbreaks. We identified a major new subclade in Nigeria that is phylogenetically distinguishable from all previously identified sublineages, as well as two novel reassortment events. A detailed analysis of viral phylogeography identified two major source populations for the HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria, one in a major commercial poultry area (southwest region) and one in northern Nigeria, where contact between wild birds and backyard poultry is frequent. These findings suggested that migratory birds from Eastern Europe or Russia may serve an important role in the introduction of HPAI H5N1 viruses into Nigeria, although virus spread through the movement of poultry and poultry products cannot be excluded. Our study provides new insight into the genesis and evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in Nigeria and has important implications for targeting surveillance efforts to rapidly identify the spread of the virus into and within Nigeria.

Since its emergence in 1996 in Guangdong, China, highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of the H5N1 subtype (HPAI H5N1 virus) has disseminated widely across Asia, Europe, and Africa, infecting a range of domestic and wild avian species and sporadically spilling over into humans and other mammals (4, 35). Over time, the HPAI H5N1 virus has diversified into multiple phylogenetically distinct lineages, classified as clades 0 to 9 according to the unified nomenclature system (33). The H5N1 lineage currently circulating in central Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa is referred to as clade 2.2 (33) and has also been described as “EMA” or Qinghai-like in previous publications (4, 17, 27). This clade originated in April 2005 during a large outbreak of a phylogenetically distinct H5N1 virus among wild bird populations at Qinghai Lake in western China (4, 17) and rapidly spread west through central Asia and Europe, eventually reaching Africa in 2006 (27). Clade 2.2 has further diversified, forming the genetic third-order clade 2.2.1 (32) and three genetically distinct sublineages (I, II, and III) (2, 19, 28), all of which are found in Africa.

Since 2006 HPAI H5N1 viruses belonging to clade 2.2 have disseminated across multiple countries in western, eastern, and northern Africa: Egypt, Niger, Cameroon, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria (2). With a large poultry industry, estimated at 140 million birds (11), Nigeria has experienced several major outbreaks of HPAI H5N1 virus, posing a serious threat to food security and public health in Africa. The first case of HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria (sublineage I) occurred in January 2006 in the state of Kaduna, and the virus subsequently was detected in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Sudan (2). In February 2006 sublineage II was reported in Nigeria, and it disseminated widely across the country during 2006 and 2007, also appearing in Togo (2). Clade 2.2.1, which has been prevalent in Egypt, Israel, and the Gaza Strip from 2006 to 2008, was also detected in Nigeria in 2006 (10).

By the end of 2007, outbreaks of HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria appeared to have been successfully controlled by measures such as “stamping out with compensation,” restrictions on movement of poultry, and enhanced surveillance (13). However, in July 2008 new cases of HPAI H5N1 from a sublineage never previously detected in Africa (sublineage III) were registered in the Nigerian states of Kano and Katsina and in live bird markets in Gombe and Kebbi states (13, 21). Hence, Nigeria is the only African country where viruses belonging to clade 2.2.1 and to three different sublineages (I, II, and III) of clade 2.2 have all been detected. At least three different reassortment events between sublineages have been documented in Nigeria. Salzberg et al. identified the first reassortant strain (which we refer to as “R1”), in which four genome segments (hemagglutinin [HA], NP, NS, and PB1) belong to sublineage I and the other four segments (NA, MP, PA, and PB2) are derived from sublineage II (27). Subsequently, phylogenetic analysis showed that a 2007 reassortant strain (which we refer to as “R3”) contained the HA and NS segments from sublineage I and the other six segments from sublineage II (19, 22). Another reassortant virus (which we refer to as “R5”) contained only the NS gene segment from sublineage I, while the other seven segments were derived from sublineage II (22).

Although the genetic diversity of the Nigerian HPAI H5N1 virus population has been well characterized, including multiple introductions of the virus into Nigeria and several reassortment events, little is known about the evolutionary and population growth dynamics of the virus within Nigeria. Particularly understudied are the spatial movements of individual sublineages among Nigeria's vast poultry population. To explore the spatial, evolutionary, and population dynamics of the multiple H5N1 lineages cocirculating in Nigeria, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of whole-genome sequences from 106 HPAI H5N1 viruses isolated between 2006 and 2008 and representing all 25 Nigerian states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) reporting outbreaks. Using the exact date and location of collection for each viral isolate, we inferred from their phylogenetic relationships the directionality of viral gene flow among Nigerian states and identified critical regions that are likely to serve as key sources for the H5N1 virus in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

The 106 viruses analyzed in this study were selected from a panel of 300 H5N1 HPAI-positive samples, collected between January 2006 and November 2007 and in July 2008 from poultry in Nigeria, in order to achieve geographical and temporal representation of the H5N1 epidemic waves that occurred in Nigeria. The samples were provided by the National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Plateau State, Nigeria. Information regarding the viruses analyzed in the present study is recorded in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Viral RNA was extracted from the infective allantoic fluid of specific-pathogen-free (SPF) fowl eggs using the Nucleospin RNA II kit (Machery-Nagel, Duren, Germany) and was reverse transcribed with the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR amplification was performed by using specific primers (primer sequences are available on request). The complete coding sequences were generated using the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The products of the sequencing reactions were cleaned-up using the Performa DTR Ultra 96-well kit (Edge BioSystems, Gaithersburg, MD) and sequenced in a 16-capillary ABI Prism 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence data were assembled and edited with SeqScape software v2.5 (Applied Biosystems). Sequences from all eight gene segments were aligned and compared with representative sequences of HPAI H5N1 viruses from Africa, Europe, and the Middle East available in GenBank.

Phylogenetic analysis.

For each of the eight genome segments, maximum-likelihood (ML) trees (Fig. 1 and 2) were estimated using the best-fit general time-reversible (GTR) + I + Γ4 model of base substitution using PAUP* (34). Parameter values for the GTR substitution matrix, base composition, gamma distribution of among-site rate variation (with four rate categories, Γ4), and proportion on invariant site (I) were estimated directly from the data using MODELTEST (25). A bootstrap resampling process (1,000 replications) using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method was used to assess the robustness of individual nodes on the phylogeny, incorporating the ML substitution model. The ML tree topology was also compared to the topology obtained using Bayesian methods available in the MrBayes v.3.1.2 program (26), again using the model of base substitution estimated by MODELTEST. Phylogenetic trees were visualized with FigTree v.1.1.2 (A. Rambaut, 2008). Fixed amino acid changes along major branches of the phylogeny were identified using the parsimony algorithm available in the MacClade program (18).

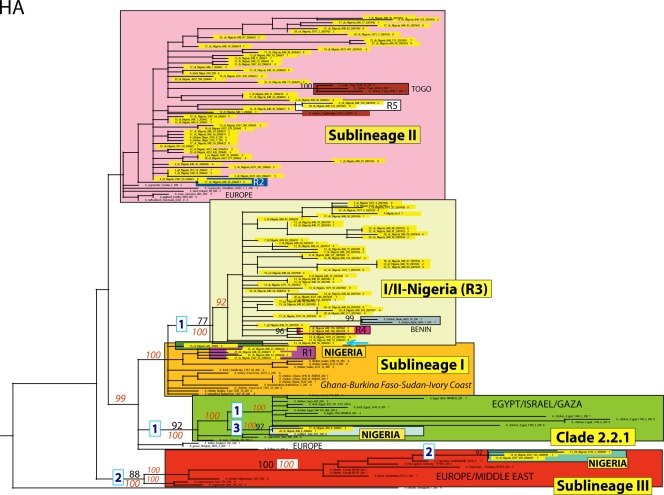

FIG. 1.

Maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree for the HA gene segment of HPAI H5N1 viruses from Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Sequences of Nigerian viruses analyzed in this study are highlighted in yellow. Sublineages and clades are colored as follows: clade 2.2.1 is in green, sublineage I is in orange, sublineage II is in pink, sublineage III is in red, and sublineage I/II-Nigeria is in yellow. The numbers at each branch point represent bootstrap values (black) and posterior probabilities (red). The numbers of substitutions that occur along the main branches appear in the blue boxes.

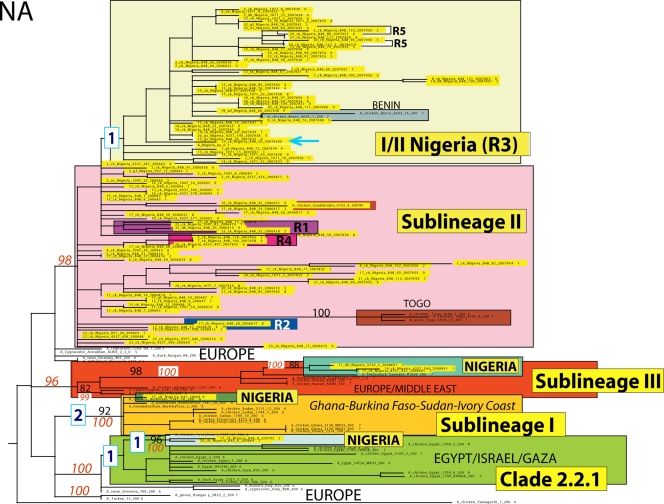

FIG. 2.

ML phylogenetic tree for the NA gene segment of HPAI H5N1 viruses from Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. The color scheme is the same as that used in Fig. 3.

Substitution rates and population dynamics.

Rates of nucleotide substitution per site and per year and the time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of the sampled data were estimated using the BEAST program version 1.4.8 (6), which incorporates the phylogenetic relationships of time-stamped viral isolates using a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach. Uncertainty in the data is reflected in the 95% highest probability density (HPD) values, and in each case chain lengths were run for a sufficient time to achieve coverage as assessed using the Tracer v1.4 program (A. Rambaut and A. J. Drummond, 2007). For each analysis the Bayesian skyline coalescent prior was used, as this is clearly the best descriptor of the complex population dynamics of influenza A virus (7). Two molecular clock models, namely, strict (constant) and uncorrelated log normal (UCLN) relaxed, were compared by analyzing values of the coefficient of variation (CV) in Tracer (A. Rambaut and A. J. Drummond, 2007), such that CV values of >0 are evidence of non-clock-like evolutionary behavior. In all cases we employed the GTR + Γ 4 model of nucleotide substitution, as more complex models resulted in overparameterization. Substitution rates and population dynamic analysis were performed for all 106 Nigerian viruses and for Nigerian viruses belonging to sublineage II and I/II-N.

Phylogeography of avian influenza virus in Nigeria.

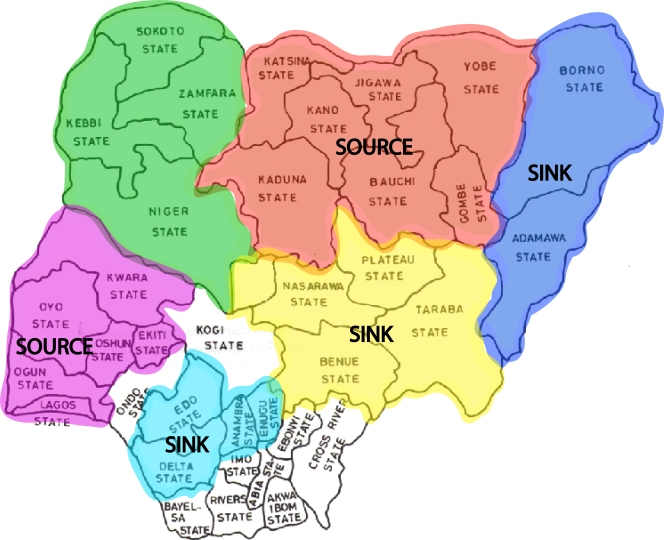

We undertook a variety of analyses of the spatial dynamics of HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria. Because of the relatively small numbers of sequences sampled from each Nigerian state, we grouped sequences into six geographical regions, representing adjacent clusters of states, which are color coded in Fig. 3. These regions are as follows: region 1 (green), Sokoto, Zamfara, and Kebbi Niger; region 2 (red), Katsina, Jigawa, Kano, Yobe, Kaduna, Bauchi, and Gombe; region 3 (blue), Borno and Adamawa; region 4 (yellow), Taraba, Plateau, Nassrawa, Beneu, and FCT; region 5 (blue), Edo, Delta, Anambra, and Enegu; and region 6 (purple), Kwara, Ekiti, Oshun, Lagos, Ogun, and Oyo.

FIG. 3.

Map showing Nigerian states. Regions identified in the migration analysis are highlighted with different colors.

To explore the overall extent of spatial structure in these sequence data, we employed a Bayesian MCMC approach, available in the Bayesian Tip-associated Significance testing (BaTS) program (23). This analysis was based on the trees that were produced by the BEAST analysis described above, with 10% removed as burn-in and employing 1,000 replications. From these trees we computed the significance of the parsimony score (PS) and association index (AI) statistics of the strength of geographical clustering by phylogeny (23). In addition, we computed the monophyletic clade (MC) statistic, which measures the strength of clustering within individual geographic regions. Importantly, this approach accounts for uncertainty in the underlying phylogeny by using a large number of plausible trees.

To explore the direction of migration events between the six regions within Nigeria in more detail, we employed a parsimony approach (20) computed on ML trees using PAUP*. In each analysis, isolates collected from the six geographical regions were assigned a specific character state. We computed the minimum number of character state changes needed to give rise to the observed distribution (with ambiguous changes excluded). To determine the number of changes expected under a null hypothesis of panmixis (completely unrestricted migration), the character states of all isolates were randomized 1,000 times on the ML tree, and for each randomization the number of changes in character state was calculated in exactly the same manner. This is equivalent to the parsimony score (PS) analysis described above, although it is based on a single phylogeny. By identifying the geographical distribution of positive PS values, it is possible to track the passage of viral gene flow.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study are available from GenBank under accession numbers CY047976 to CY048647, CY016276 to CY016283, CY017179 to CY017186, CY016284 to CY016291, CY016907 to CY016954, and EU148356 to EU148451 or from the GISAID public database under accession numbers EPI161701 to EPI161708.

RESULTS

Extensive genetic diversity of HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria from 2006 to 2008.

The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees inferred for all eight genome segments of 106 HPAI H5N1 viruses sampled between January 2006 and July 2008 in 25 Nigerian states and the FCT revealed all four sublineages previously identified in Nigeria: sublineages I, II, and III and clade 2.2.1 (2, 9, 10, 13, 22). Sublineages I and III and clade 2.2.1 were defined by high bootstrap (>70%) or posterior probability (>90%) values and long branches in all the phylogenetic trees (with the exception of the phylogenetic tree for the M gene), while sublineage II had poor bootstrap and posterior probability support (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 to S6 in the supplemental material). In addition, our phylogenetic analysis identified a major new sublineage in Nigeria, phylogenetically distinguishable from all previously identified sublineages of clade 2.2, which circulated widely in Nigeria during 2006 and 2007. This sublineage is here denoted sublineage I/II-Nigeria (“I/II-N”), due to its phylogenetic proximity to sublineage I on trees inferred for the HA and NS genome segments and to sublineage II for the remaining six segments. The vast majority (46/48) of isolates in this lineage were collected in Nigeria; the other two isolates were collected from Benin (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 to S6 in the supplemental material).

At a population level, the majority of Nigerian H5N1 viruses isolated between the years 2006 and 2008 belong to either sublineage II or I/II-N (47 and 46 of 106 isolates, respectively), whereas only one, two, and three isolates belong to sublineage I, clade 2.2.1, and sublineage III, respectively (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 to S6 in the supplemental material). A/chicken/Nigeria/641/2006(H5N1) is the only Nigerian isolate from sublineage I for which the entire genome sequence is available, with only the HA segment from two additional Nigerian isolates from sublineage I available on GenBank: A/chicken/Nigeria/VRD44/2006(H5N1) and A/chicken/Nigeria/VRD83/2006(H5N1), accession numbers EF631174 and EF631177 (12). Either surveillance in Nigeria is not sufficient to detect additional isolates belonging to this sublineage in circulation or sublineage I circulated in Nigeria for only a short time at a relatively low prevalence.

Only two isolates from clade 2.2.1 were detected among the 106 Nigerian samples, i.e., A/chicken/Nigeria/848-6/2006(H5N1) and A/chicken/Nigeria/848-8/2006(H5N1), which were collected between February and March 2006 in the states of Ogun and Lagos, respectively. The majority of isolates in clade 2.2.1 are from Egypt, the Gaza Strip, and Israel, collected from 2006 to 2008. However, the Nigerian isolates in this clade are phylogenetically distinguishable from the Egyptian isolates, and five key amino acid differences found across the viral genome distinguish A/chicken/Nigeria/848-6/2006(H5N1) and A/chicken/Nigeria/848-8/2006(H5N1) from the isolates from Egypt and the Middle East that also belong to clade 2.2.1 (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Multiple reassortment events among Nigerian HPAI N5N1 viruses.

Although each sublineage generally contains the same set of isolates on each tree, genomic reassortment occasionally results in isolates being positioned within different clades on the phylogenies inferred for different genome segments. In addition to the three reassortment events evident from phylogenetic incongruities that have been described previously (R1, R3, and R5) (Table 1) (19, 22, 27), our phylogenetic analysis reveals two additional reassortment events. Topological differences in the phylogenetic trees suggest that the NS and NP segments of the isolate A/chicken/Nigeria/848-26/2006(H5N1) (“R2”) (Table 1) were more related to sublineage I and revealed the highest nucleotide identity, 99.7% for the NS segment and 99.9% for the NP segment with A/chicken/Nigeria/641/2006 (sublineage I), while the other gene segments belonged to sublineage II. A/chicken/Nigeria/848-106/2007 and A/chicken/Nigeria/848-118/2007 (“R4”) viruses fell into sublineage I/II-N, with the exception of the NA segment, which was closely related to sublineage II (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Genome constellations of the reassortant H5N1 viruses collected in Nigeriaa

The different colors reflect segments whose sequences fall into different sublineages of clade 2.2.

In some cases, reassortment events involve entire clades, as in the case of the novel sublineage I/II-N. For the majority of segments (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, NA, and M), sublineage I/II-N is most related phylogenetically to sublineage II, although a long branch still separates these clades in all cases except the M segment (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 to S6 in the supplemental material). However, on the HA and NS trees (Fig. 1; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), sublineage I/II-N is phylogenetically more related to sublineage I, which is evidence that the entire sublineage I/II-N was generated by a major reassortment event between clades that are related to sublineages I and II although separated by long branch lengths (Fig. 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 to S6 in the supplemental material). It is also possible that sublineage I/II-N acquired the M segment directly from sublineage II, as these clades are merged on the M phylogeny. However, phylogenetic resolution is too low in this portion of the tree to discern.

Variable rates of viral evolution in Nigeria.

The rate of evolutionary change (recorded as nucleotide substitutions per site per year) was estimated for each segment for the entire population of Nigerian isolates and for each of the two main sublineages found in Nigeria, sublineages II and I/II-N (Table 2). For the HA, NA, NS, PB1, PB2, PA, and M gene segments, the lower 95% HPDs of CV values of the relaxed molecular clock were approximately 0, so a strict molecular clock model was used to estimate the evolutionary dynamics. However, the NP gene of the entire population of Nigerian isolates and the NP gene of sublineage I/II-N showed CV values of >0, so a relaxed (uncorrelated lognormal) molecular clock model, which allows for rate variation across lineages, was used for these two data sets. In each case, very similar results were obtained under both strict and relaxed molecular clock models. The mean substitution rates for all segments and subtypes were found to be within the range typically observed for avian influenza viruses (5), although differences were found across segments and sublineages. The lowest rate of evolution was observed for the HA segment from sublineage I/II-N (2.88 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year; 95% HPD, 1.54 × 10−3 to 4.29 × 10−3), while the highest rate was observed for the NA segment from sublineage II (6.56 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year; 95% HPD, 4.83 × 10−3 to 8.57 × 10−3) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Estimates of the nucleotide substitution rate calculated for all the Nigerian viruses, sublineage II, and sublineage I/II-N

| Gene | Substitutions/site/yr (×10−3) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigerian viruses |

Sublineage II |

Sublineage I/II-N |

||||

| Mean | 95% HPD | Mean | 95% HPD | Mean | 95% HPD | |

| HA | 5.07 | 4.25-5.94 | 5.42 | 3.98-6.89 | 2.88 | 1.54-4.29 |

| NA | 5.75 | 4.53-8.96 | 6.56 | 4.83-8.57 | 5.99 | 3.81-8.29 |

| PB2 | 5.09 | 4.26-5.91 | 5.40 | 4.07-6.73 | 4.34 | 3.20-6.15 |

| PB1 | 4.82 | 4.06-5.59 | 5.01 | 3.83-6.23 | 4.34 | 2.98-5.53 |

| PA | 5.03 | 4.22-5.83 | 3.28 | 1.85-4.72 | 3.26 | 1.95-4.76 |

| NP | 4.87 | 3.76-5.98 | 5.34 | 3.67-7.03 | 5.24 | 3.6-7.13 |

| NS | 5.34 | 4.07-6.74 | 6.23 | 4.09-8.53 | 4.94 | 2.58-7.44 |

| MP | 4.17 | 2.96-5.4 | - | - | - | - |

Evolutionary origins of the viral genetic diversity found in Nigeria.

To further explore the evolutionary origins of sublineage I/II-N in Nigeria, we estimated the time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of sublineage I/II-N (Table 3). The tMRCAs for the NA, PB2, PB1, NP, and NS gene segments of sublineage I/II-N isolates ranged from December 2005 to November 2006 (95% HPD) (Table 3), dates which approximately overlap with when sublineages I and II were circulating in Nigeria and consistent with a Nigerian origin for sublineage I/II-N. The tMRCAs of the HA gene segment ranged from August 2005 to August 2006 (95% HPD), which is antecedent to the period of detection of viruses belonging to the two parent sublineages. The tMRCAs estimated for all the Nigerian isolates ranged from September 2004 to November 2005 (95% HPD), which approximately coincides with the origin and spread of clade 2.2 at the Qinghai Lake outbreak and is consistent with multiple introductions of clade 2.2 into Nigeria. The estimates for the tMRCA of sublineage II in Nigeria ranged from August 2005 to January 2006 (95% HPD), approximately 1 to 6 months before sublineage II was first detected by surveillance in Nigeria in February 2006. The presence of viruses of the same sublineage in other areas of the world, such as Europe, at the same time indicates that this group was introduced into Nigeria at the beginning 2006 or the end of 2005 and might to have circulated undetected until February 2006. Finally, broader 95% HPD values were observed for the PA segment, particularly for sublineages II (September 2004 to March 2006) and I/II-N (November 2004 to July 2006), suggesting that this segment has insufficient phylogenetic signal for precise estimates of tMRCA values.

TABLE 3.

Estimates of tMRCA for all the Nigerian viruses, sublineage II, and sublineage I/II-N

| Gene | Mean tMRCA (95% HPD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigerian viruses | Sublineage II | Sublineage I/II-N | |

| HA | Mar. 2005 (Jan. 2004-Aug. 2005) | Nov. 2005 (Sept. 2005-Dec. 2005) | Mar. 2006 (Aug. 2005-Aug. 2006) |

| NA | June 2005 (Feb. 2005-Oct. 2005) | Nov. 2005 (Sept. 2005-Jan. 2006) | July 2006 (Mar. 2006-Nov. 2006) |

| PB2 | Mar. 2005 (Oct. 2004-Aug. 2005) | Oct. 2005 (Oct. 2005-Jan. 2006) | May 2006 (Jan. 2006-Aug. 2006) |

| PB1 | Feb. 2005 (Sept. 2004-July 2005) | Nov. 2005 (Sept. 2005-Jan. 2006) | May 2006 (Jan 2006-Sept. 2006) |

| PA | June 2005 (Feb. 2005-Nov. 2005) | July 2005 (Sept. 2004-Mar. 2006) | Sept. 2005 (Nov 2004-July 2006) |

| NP | June 2005 (Nov. 2004-Nov. 2005) | Dec. 2005 (Nov. 2005-Jan. 2006) | Sept. 2006 (Apr. 2006-Nov 2006) |

| NS | Oct. 2004 (Jan. 2004-June 2005) | Nov. 2005 (Aug. 2005-Jan. 2006) | Jun. 2006 (Dec. 2005-Oct. 2006) |

| MP | Mar. 2005 (July 2004-Oct. 2005) | ||

To further investigate the source of the sublineages detected in Nigeria, we used BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to identify the HA sequences of viruses isolated outside Nigeria that showed the highest similarity to the first isolate that was collected from each Nigerian clade. In each case, the first Nigerian isolate from each sublineage showed the highest identity with viruses collected from birds in Eastern Europe some months prior to detection in Nigeria. The HA genes of the first isolates of sublineages I (A/chicken/Nigeria/641/2006) and II (A/chicken/Nigeria/848-1/2006) showed the highest identity (99%) with viruses isolated from poultry in Romania and Russia in 2005. Nigerian viruses belonging to clade 2.2.1 possessed the highest similarity with viruses isolated from wild birds from Slovenia and Austria in 2006. Nigerian viruses isolated in 2008 from sublineage III showed the highest similarity with a virus collected from a mute swan in the Czech Republic, A/Cygnus olor/Czech Republic/10732/2007(H5N1).

The PB2 and PB1-F2 genes of sublineage I/II-N viruses possess three amino acid signatures (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material) typical of African H5N1 viruses. Furthermore, one of the earliest isolates of sublineage I/II-N, A/chicken/Nigeria/848-50/2006(H5N1) (collected in Kaduna state, 13 December 2006), is phylogenetically positioned as an outgroup on the HA, PB2, PB1, and PA trees, while on the NS tree it is more related to sublineage I, the apparent source of the HA and NS genes of sublineage I/II-N. Notably, this isolate does not possess the three amino acid signatures typical of sublineage I/II-N for the NS and PB1-F2 genes (see Fig. S1 and S5 in the supplemental material) but does contain such amino acid signatures for other genes, including HA and PB2, suggesting that this Nigerian isolate is an evolutionary intermediary between the parental sublineages (sublineages I and II) and sublineage I/II-N. This finding supports the hypothesis that sublineage I/II-N evolved locally in Nigeria.

Phylogeography of H5N1 within Nigeria.

Isolates collected from each of the 25 Nigerian states and the FCT recording outbreaks of H5N1 are interspersed throughout the phylogenetic trees inferred for each segment, which is indicative of widespread viral gene flow throughout Nigeria. The two dominant Nigerian clades, sublineages II and I/II-N, were detected in 22/25 and 18/25 states, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Despite the occurrence of viral traffic through Nigeria, our Bayesian MCMC analysis of geographical association revealed a clear clustering by geographic region (P = 0 for both the AI and PS statistics in all gene segments); hence, there is localized in situ evolution of avian influenza virus within Nigeria. Such localized clustering was especially strong in the southeastern region (yellow in Fig. 3), in which the MC statistic was significant for all gene segments (P < 0.005 in all cases; full results are available from the authors on request). No other region exhibited a significant MC value (i.e., P < 0.05).

An additional parsimony-based migration analysis (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) revealed that the direction of viral migration occurred predominantly from north-central (red region in Fig. 3) and southwestern (pink) regions to northeastern (blue), southeastern (yellow), and south-central (light blue) regions. Hence, the north-central and southwestern regions perhaps serve as the critical sources for the spread of the HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria, whereas the northeastern, southeastern, and south-central regions appear to act primarily as an ecological sink (Fig. 3). That the southeastern region was also strongly significant according the MC statistic (see above) suggests that it represents a particularly strong sink population.

DISCUSSION

Through phylogenetic analyses of 106 Nigerian HPAI H5N1 virus isolates collected from 2006 to 2008, we have elucidated the evolutionary dynamics of one of the largest and most diverse influenza virus populations in Africa. First, we have identified a major new reassortant sublineage, “I/II-N,” in Nigeria. Sublineage I/II-N appears to have evolved locally in Nigeria, although the origins of the HA and NS segments are more difficult to assess, as sublineage I is present in multiple countries. Our estimate of the tMRCA indicates that sublineage I/II-N likely originated in Nigeria between August 2005 and November 2006, approximately 1 to 15 months before being detected through surveillance. Hence, this virus may have been circulating undetected in Nigeria for several months, perhaps accounting for the long branch between parental sublineages (I and II) and I/II-N that is evident on each phylogenetic tree. We also identified two novel reassortment events involving sublineages I and II (R2 and R4). Notably, all of the Nigerian reassortant viruses possess an NS gene of sublineage I origin and PB2, PA, MP, and NA genes belonging to sublineage II, perhaps suggesting that these segments confer a selective advantage. Cocirculation of multiple genetically distinct sublineages has also been reported in others countries, such as China (31), Vietnam (24), Indonesia (16), and Thailand (29). To explain the observed patterns of genetic reassortment of H5N1 in China, Vijaykrishna et al. suggested that viruses undergo regular reassortment with endemic H5N1 viruses in domestic ducks and subsequently are transmitted to poultry (31). Given that the hypothetical ancestor of sublineage I/II-N was collected from the area of Nigeria with the highest concentration of domestic ducks, this mechanism is further supported by the data presented in this study.

Our phylogeographic analysis identified the north-central (Katsina, Jigawa, Yobe, Kano, Kaduna, Bauchi, and Gombe) and southwest (Lagos, Ogun, Oyo, Ekiti, and Kwara) regions as the two major sources for the HPAI H5N1 virus in Nigeria. These findings are consistent with the distribution of poultry farms in Nigeria. Indeed, southwestern Nigeria, particularly the states surrounding the city of Lagos, hold much of Nigeria's poultry industry (11). It is estimated that over 65% of Nigeria's commercial poultry is located in the five southern states of Lagos, Ogun, Oyo, Osun, and Ondo (11). In north-central Nigeria, Jigawa and Yobe states are home to the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, characterized by permanent and seasonal lakes and a numerous population of migratory and residential waterfowl. This area also sustains a large backyard poultry population and the highest concentration of domestic ducks, reared under free-range conditions, providing opportunities for contact between wild birds and backyard poultry (3). It has been suggested that migratory birds may play a role in the introduction of HPAI H5N1 virus into Nigeria (2, 3, 15, 27). In fact, the migration paths ending in the Hadejia-Nuguru wetlands intersect with areas in Eastern Europe where HPAI H5N1 virus has been circulating since autumn of 2005 (3).

Of note, the first isolate of each sublineage (I, II, and III) detected in Nigeria, as well as the likely ancestor of sublineage I/II-N, were collected from the northern part of Nigeria (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and our BLAST analysis suggests that early Nigerian isolates show the highest similarity with influenza viruses from birds in Eastern Europe. This is also consistent with previous findings concerning the novel introduction into northern Nigeria of sublineage III in 2008 (13), and these findings provide additional evidence that migratory birds from Eastern/Central Europe or Russia are implicated in the introduction of HPAI H5N1 viruses into Nigeria. This is consistent with the several reports concerning the introductions into European countries of distinct sublineages of clade 2.2 HPAI H5N1 viruses through wild birds, for example, in Germany, Denmark, Hungary, France, and Italy (1, 14, 27, 28, 30). However, it is still not possible to exclude the involvement of trade of poultry and poultry products as a source of infection.

Our study has important implications for predicting and preventing future introductions and spread of H5N1 virus in Nigeria and for targeted surveillance. Indeed, minimizing contacts between farmed poultry and wild birds in the northern regions of Jigawa and Yobe should reduce the risk of future outbreaks, as well as improving passive surveillance for HPAI virus in sick or dead wild birds in these areas. Similarly, our analysis suggests that after the primary introductions in Nigeria, likely through wild migratory birds, trade of poultry or poultry products was an important pathway for the spread of virus throughout the country. Increased monitoring of poultry trade from high-risk areas (north-central and southwest regions [see above]), identified as the main sources of viruses in this study, should be implemented to reduce the spread of H5N1 virus.

In addition to how the HPAI H5N1 virus entered Nigeria, another major unresolved question is the evolutionary basis for why certain sublineages thrive in Nigeria, particularly sublineages II and I/II-N, while sublineages I and III and clade 2.2.1 appear to have spread little, despite the success of these clades in other regions, particularly clade 2.2.1 in Egypt. It is possible that surveillance in Nigeria is insufficient to detect the presence of clades circulating at low levels or in certain geographic regions. Indeed, our tMRCA estimates indicate that viral clades in Nigeria may circulate for some months before being detected. The acquisition of the HA and NS segments from sublineage I by sublineage I/II-N also suggests that sublineage I may have circulated more extensively than was detected by surveillance. Direct associations among the H5N1 outbreaks in Egypt and the viruses circulating in Nigeria can be excluded, based on the findings presented here. It is also possible that stochastic effects may have a greater impact on the population structure of HPAI H5N1 virus than selective pressures. Interestingly, sublineage I also appears to have circulated in poultry populations for only short durations in other African countries, including Ivory Coast (10 months), Burkina Faso (2 months), Sudan (7 months), and Ghana (4 months) (2). A similar situations was reported in Thailand, where one reassortant H5N1 strain emerged and replaced the two parental lineages (PC168-like and PC170-like) of clade 1 (29) Similarly, in Vietnam clade 2 viruses replaced clade 1 viruses in 2005 (24), and in China genotype Z gradually became predominant from 2002 to mid-2005 and was gradually replaced by genotype V in southern China in late 2005 (8).

Additional influenza virus sequence data from other African countries are greatly needed to further understand the evolutionary dynamics of the multiple sublineages circulating in Nigeria and other parts of Africa. Sharing reliable genetic and epidemiological data in a timely manner can promote better HPAI virus control strategies and optimize targeted surveillance programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ministry of Agriculture of Nigeria for its continuous support for and assistance with the avian influenza control program in the country. We thank the staff of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (UN-FAO) headquarters in Rome, Italy, and Tesfai Tseggai and the UN-FAO/ECTAD unit, Abuja, Nigeria, for their assistance in facilitating exchange of information, data sharing, and sample submissions.

Part of this study was conducted in the framework of the EU projects EPIZONE (Network of Excellence for Epizootic Disease Diagnosis and Control) and FLUTRAIN (Training and Technology Transfer of Avian Influenza Diagnostics and Disease Management Skills).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 January 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bragstad, K., P. H. Jørgensen, K. Handberg, A. S. Hammer, S. Kabell, and A. Fomsgaard. 2007. First introduction of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza A viruses in wild and domestic birds in Denmark, Northern Europe. Virol. J. 11;4:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cattoli, G., I. Monne, A. Fusaro, T. M. Joannis, L. H. Lombin, M. M. Aly, A. S. Arafa, K. M. Sturm-Ramirez, E. Couacy-Hymann, J. A. Awuni, K. B. Batawui, K. A. Awoume, G. L. Aplogan, A. Sow, A. C. Ngangnou, I. M. El Nasri Hamza, D. Gamatie, G. Dauphin, J. M. Domenech, and I. Capua. 2009. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H5N1 in Africa: a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis and molecular characterization of isolates. PLoS One 4:e4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cecchi, G., A. Ilemobade, Y. Le Brun, L. Hogerwerf, and J. Slingenbergh. 2008. Agro-ecological features of the introduction and spread of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in northern Nigeria. Geospat. Health 3:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, H., G. J. D. Smith, S. Y. Zhang, K. Qn, J. Wang, K. S. Li, R. G. Webster, J. S. Peiris, and Y. Guan. 2005. Avian flu: H5N1 virus outbreak in migratory waterfowl. Nature 436:191-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, R., and E. C. Holmes. 2006. Avian influenza virus exhibits rapid evolutionary dynamics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23:2336-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond, A. J., and A. Rambaut. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond, A. J., A. Rambaut, B. Shapiro, and O. G. Pybus. 2005. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22:1185-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan, L., J. Bahl, G. J. Smith, J. Wang, D. Vijaykrishna, L. J. Zhang, J. X. Zhang, K. S. Li, X. H. Fan, C. L. Cheung, K. Huang, L. L. Poon, K. F. Shortridge, R. G. Webster, J. S. Peiris, H. Chen, and Y. Guan. 2008. The development and genetic diversity of H5N1 influenza virus in China, 1996-2006. Virology 380:243-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducatez, M. F., C. M. Olinger, A. A. Owoade, S. De Landtsheer, W. Ammerlaan, H. G. Niesters, A. D. Osterhaus, R. A. Fouchier, and C. P. Muller. 2006. Avian flu: multiple introductions of H5N1 in Nigeria. Nature 442:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducatez, M. F., C. M. Olinger, A. A. Owoade, Z. Tarnagda, M. C. Tahita, A. Sow, S. De Landtsheer, W. Ammerlaan, J. B. Ouedraogo, A. D. Osterhaus, R. A. Fouchier, and C. P. Muller. 2007. Molecular and antigenic evolution and geographical spread of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in western Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 88:2297-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FAO. 2008. Poultry sector country review—Nigeria. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 12.Fasina, F. O., A. C. Meseko, T. M. Joannis, A. I. Shittu, H. G. Ularamu, N. A. Egbuji, L. K. Sulaiman, and N. O. Onyekonwu. 2007. Control versus no control: options for avian influenza H5N1 in Nigeria. Zoonoses Public Health 54:173-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fusaro, A., T. Joannis, I. Monne, A. Salviato, B. Yakubu, C. Meseko, T. Oladokun, S. Fassina, I. Capua, and G. Cattoli. 2009. Introduction into Nigeria of a distinct genotype of avian influenza virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:445-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gall-Reculé, G. L., F. X. Briand, A. Schmitz, O. Guionie, P. Massin, and V. Jestin. 2008. Double introduction of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus into France in early 2006. Avian Pathol. 37:15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilpatrick, A. M., A. A. Chmura, D. W. Gibbons, R. C. Fleischer, P. P. Marra, and P. Daszak. 2006. Predicting the global spread of H5N1 avian influenza. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:19368-19373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam, T. T., C. C. Hon, O. G. Pybus, S. L. Kosakovsky Pond, R. T. Wong, C. W. Yip, F. Zeng, and F. C. Leung. 2008. Evolutionary and trasmission dynamics or reassortant H5N1 influenza virus in Indonesia. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, J., H. Xiao, F. Lei, K. Qin, X. W. Zhang, X. L. Zhang, D. Zhao, G. Wang, Y. Feng, J. Ma, W. Liu, J. Wang, and G. F. Gao. 2005. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in migratory birds. Science 309:1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddison, W. P., and D. R. Maddison. 1989. Interactive analysis of phylogeny and character evolution using the computer program MacClade. Folia Primatol. (Basel) 53:190-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monne, I., T. M. Joannis, A. Fusaro, P. De Benedictis, L. H. Lombin, H. Ularamu, A. Egbuji, P. Solomon, T. U. Obi, G. Cattoli, and I. Capua. 2008. Reassortant avian influenza virus (H5N1) in poultry, Nigeria, 2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:637-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano, T., L. Lu, P. Liu, and O. G. Pybus. 2004. Viral gene sequences reveal the variable history of hepatitis C virus infection among countries. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1098-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OIE-World Organization for Animal Health. 2008. Update on highly pathogenic avian influenza in animals (type H5 and H7). OIE-World Organization for Animal Health, Paris, France.

- 22.Owoade, A. A., N. A. Gerloff, M. F. Ducatez, J. O. Taiwo, J. R. Kremer, and C. P. Muller. 2008. Replacement of sublineages of avian influenza (H5N1) by reassortments, sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1731-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker, J., A. Rambaut, and O. G. Pybus. 2008. Correlating viral phenotypes with phylogeny: accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeiffer, J., M. Pantin-Jackwood, T. L. To, T. Nguyen, and D. L. Suarez. 2009. Phylogenetic and biological characterization of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses (Vietnam 2005) in chickens and ducks. Virus Res. 142:108-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posada, D., and K. A. Crandall. 1998. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14:817-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronquist, F., and J. P. Huelsenbeck. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salzberg, S. L., C. Kingsford, G. Cattoli, D. J. Spiro, D. A. Janies, M. M. Aly, I. H. Brown, E. Couacy-Hymann, G. M. De Mia, H. Dung do, A. Guercio, T. Joannis, A. S. Maken Ali, A. Osmani, I. Padalino, M. D. Saad, V. Savic, N. A. Sengamalay, S. Yingst, J. Zaborsky, O. Zorman-Rojs, E. Ghedin, and I. Capua. 2007. Genome analysis linking recent European and African influenza (H5N1) viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:713-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starick, E., M. Beer, B. Hoffmann, C. Staubach, O. Werner, A. Globig, G. Strebelow, C. Grund, M. Durban, F. J. Conraths, T. Mettenleiter, and T. Harder. 2008. Phylogenetic analyses of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus isolates from Germany in 2006 and 2007 suggest at least three separate introductions of H5N1 virus. Vet. Microbiol. 128:243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwannakarn, K., A. Amonsin, J. Sasipreeyajan, P. Kitikoon, R. Tantilertcharoen, S. Parchariyanon, A. Chaisingh, B. Nuansrichay, T. Songserm, A. Theamboonlers, and Y. Poovorawan. 2009. Molecular evolution of H5N1 in Thailand between 2004 and 2008. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9:896-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szeleczky, Z., A. Dán, K. Ursu, E. Ivanics, I. Kiss, K. Erdélyi, S. Belák, C. P. Muller, I. H. Brown, and A. Bálint. 2009. Four different sublineages of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 introduced in Hungary in 2006-2007. Vet. Microbiol. 139:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijaykrishna, D., J. Bahl, S. Riley, L. Duan, J. X. Zhang, H. Chen, J. S. Peiris, G. J. Smith, and Y. Guan. 2008. Evolutionary dynamics and emergence of panzootic H5N1 influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 Evolution Working Group. 2009. Continuing progress towards a unified nomenclature for the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses: divergence of clade 2.2 viruses. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 3:59-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 Evolution Working Group. 2008. Toward a unified nomenclature system for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilgenbusch, J. C., and D. Swofford. 2003. Inferring evolutionary trees with PAUP*. Current protocols in bioinformatics, chapter 6, unit 6.4. Wiley, Somerset, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Xu, X., K. Subbarao, NJ Cox, and Y. Guo. 1996. Genetic characterization of the pathogenic influenza A/Goose/Guangdong/1/96 (H5N1) virus: similarity of its hemagglutinin gene to those of H5N1 viruses from the 1997 outbreaks in Hong Kong. Virology 224:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.