Abstract

Prion diseases are fatal, untreatable neurodegenerative diseases caused by the accumulation of the misfolded, infectious isoform of the prion protein (PrP), termed PrPSc. In an effort to identify novel inhibitors of prion formation, we utilized a high-throughput enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to evaluate PrPSc reduction in prion-infected neuroblastoma cell lines (ScN2a). We screened a library of ∼10,000 diverse small molecules in 96-well format and identified 121 compounds that reduced PrPSc levels at a concentration of 5 μM. Four chemical scaffolds were identified as potential candidates for chemical optimization based on the presence of preliminary structure-activity relationships (SAR) derived from the primary screening data. A follow-up analysis of a group of commercially available 2-aminothiazoles showed this class as generally active in ScN2a cells. Our results establish 2-aminothiazoles as promising candidates for efficacy studies of animals and validate our drug discovery platform as a viable strategy for the identification of novel lead compounds with antiprion properties.

Prion diseases belong to a class of neurodegenerative, protein-conformation disorders whose unifying pathological mechanism is the misprocessing and aggregation of normally benign soluble proteins. These “proteinopathies,” which include Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases, as well as the frontotemporal dementias—including Pick's disease—and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are uniformly fatal after a period of neurodegeneration, characterized clinically by dementia and motor dysfunction (20). Prion diseases, which include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans, scrapie in sheep, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, are characterized by the formation of “spongiform” vacuolation of the brain (13). Disease onset is caused by the accumulation of a β-sheet-rich, infectious isoform of the prion protein, termed PrPSc (1, 16, 19, 20), which is formed from the α-helix-rich cellular prion protein, termed PrPC. This conversion can occur spontaneously or be induced by the presence of a number of different autosomally dominant mutations of the PrP gene (8, 21). Alternatively, prion disease can result from exogenous exposure to PrPSc (20). The infectious nature of prions results from the ability of PrPSc to induce its own production by stimulating the alternative folding of PrPC (18). Although PrPSc formation has been demonstrated to be the primary pathogenic event in prion disease, the precise mechanism that features in its formation and the ensuing neurodegeneration remains largely unknown.

Despite the lack of a detailed understanding of the cellular mechanism of prion propagation, numerous studies have been directed toward development of therapeutics targeting prions. Screenings utilizing prion-infected cell lines have identified a number of compounds that reduce the level of PrPSc in culture. These include pentosan polysulfate (PPS), dextran sulfate (DS), HPA-23, Congo red, suramin, dendritic polyamines, and quinacrine, among others; for a comprehensive review, see reference 22. However, none of these have been shown to be effective against a broad range of prion strains in animal models when administered after clinical signs manifest, and none have been shown to modify the disease course in human clinical studies (22).

The current array of antiprion compounds has been discovered mostly by ad hoc, low-throughput screening of small sets of known bioactive compounds. Most antiprion compounds that are active in prion-infected cell lines have failed in vivo, which highlights the need for a sustained, high-throughput drug discovery effort. Such studies need to rapidly screen large libraries of new chemical entities in vitro, analyze the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the primary hits in vivo, and optimize the chemical properties of lead compounds. In two semi-high-throughput screenings for antiprion compounds, an analysis of ∼2,000-member compound libraries of known drugs and natural products identified sets of 17 and 8 active compounds (10). None of these have been reported to be effective in vivo.

In the present study, we assessed the antiprion activity of ∼10,000 compounds encompassing a diverse set of chemical entities and identified a set of 121 compounds that induce the clearance of PrPSc. Subsequent analysis of a number of compounds with the 2-aminothiazole scaffold informed the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of this lead class.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Unless otherwise noted, all materials were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without purification. All solvents were obtained commercially in the highest purity (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.) and used without further purification. Guanidine thiocyanate, diethanolamine, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. Minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle's salts, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+, trypsin-EDTA, cell dissociation buffer, and GlutaMax were purchased from Invitrogen-Gibco. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from HyClone, and proteinase K (PK) was from Invitrogen. 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) was purchased from KPL. Benzonase nuclease was obtained from Novagen. Anti-PrP Fab antibody D18 and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-PrP Fab antibody D13 were prepared in-house.

Chemical library.

The 10,135 compounds employed in the high-throughput screening (HTS) represent a subset of a ChemDiv diversity set curated by the Small Molecule Discovery Center at the University of California, San Francisco.

Cellular toxicity and antiprion activity assays.

N2a cells were infected with the Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) prion strain and subcloned as described previously to produce ScN2a cells (3). ScN2a cells were maintained in filter-sterilized (0.2 μm) MEM supplemented with FBS and GlutaMax. On day 1, medium was aspirated from a confluent 100-mm plate of ScN2a cells, and cells were detached by the addition of cell dissociation buffer (1 ml). MEM was added (approximately 10 ml), and the cell concentration was determined using packed cell volume tubes (TPP). The ScN2a cell concentration was adjusted to 4 × 105 cells ml−1 with MEM. A 96-well, tissue culture-treated, clear-bottom, black plate (Greiner Bio-One) wetted with MEM (90 μl) was incubated at 37°C prior to use. To this plate, 100 μl of the ScN2a cell suspension was transferred, and the cells were allowed to settle for 2 h prior to the addition of the test compound. Compound libraries were prepared in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at the required concentrations in a 96-well format and then diluted 1/10 (high-throughput single-concentration screening) or 1/20 (dose-response titration) with sterile PBS prior to use. Compounds (10 μl) were transferred to the 96-well cell culture plate, and the plates were incubated at 37°C. Final DMSO concentrations did not exceed 0.25% (vol/vol). Media were aspirated on day 5, and the cells were washed once with PBS (200 liters). Calcein-AM (100 ml; 2.5 g ml−1 solution in PBS) was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 25 min. Fluorescent emission intensity was quantified using a fluorescence plate reader, with excitation and emission spectra of 492 nm and 525 nm, respectively.

The calcein-AM solution was aspirated, 15 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% Nonidet P-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) containing benzonase nuclease (7.5 U ml−1) was added to each well, and the plates were shaken for 1 h at 37°C. PK (5 μl; 1.25 mg ml−1 solution in lysis buffer) was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Proteolysis was stopped by the addition of PMSF (5 μl; 20 mM solution in ethanol), with a 10-min incubation at room temperature. PK-digested PrPSc was denatured with 6 M guanidine isothiocyanate (10 μl) for 1 h at 37°C by using a shaker before being diluted with 215 μl of 1% BSA/PBS. Denatured lysates (250 μl) were precipitated with phosphotungstate (PTA) and used to coat ELISA plates. The plates were probed with D18 primary antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody as previously described (14). Plates were washed seven times with TBST, and 100 μl of ABTS was added to each well. After being developed for 15 to 20 min, plates were read using a SpectraMax Plus and/or an M5 microplate reader running SoftMaxPro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Untreated ScN2a cells and plates with no cells were used as controls. Dose-response curves over a concentration range were determined in triplicate from three independent experiments. Compound toxicity, as determined from the cell viability component of the assay, was expressed as the LD50, the compound concentration at which 50% of the cells were viable. Bioactivity against PrPSc accumulation was expressed as the EC50, the compound concentration at which 50% of PrPSc had been removed from the culture upon exposure to the compound. Dose-response curves and EC50s were computed using SigmaPlot (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Fluorescence intensity was determined using a Tecan Genios fluorescence microplate reader running XFluor4 software and/or a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader runnning SoftMaxPro software. Absorbance was determined using a SpectraMax Plus and/or an M5 microplate reader running SoftMaxPro software. ELISA plates were washed and aspirated using a Bio-Tek Elx405 plate washer. Plate-to-plate transfers and liquid dispensing were done using a Labctye S4 liquid handler and/or a Beckman Coulter Biomek NX fitted with a fixed 96-well head.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

High-throughput screening.

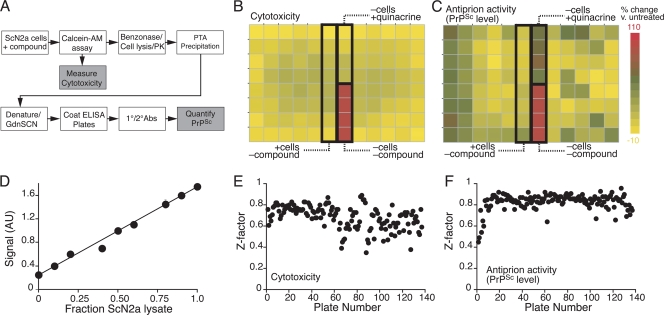

N2a cells were infected with the RML strain of rodent-passaged scrapie prions, as previously described (3). These infected (ScN2a) cells harbor and stably propagate protease-resistant PrPSc as assessed by Western immunoblotting following proteinase K (PK) digestion. In the high-throughput screening (HTS), 40,000 cells were cultured in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate, as described in Materials and Methods. The culture was exposed to compounds at a concentration of 5 μM for 6 days. On day 6, when the culture reached confluence (∼200,000 cells per well), the inherent toxicity of each compound was assessed using calcein-AM, a fluorescent dye that is retained by healthy cells with intact membranes (12). Changes in PrPSc levels were measured by ELISA following PK digestion and a cycle of denaturation and renaturation, as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). Wells lacking cells were included as positive controls for the cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 1B). For antiprion activity, each plate included quinacrine-treated cells as a positive control and untreated cells as a negative control (Fig. 1C). Both cytotoxicity and antiprion activity were quantitatively measured as fractions relative to the respective positive controls.

FIG. 1.

High-throughput assay for the identification of antiprion compounds. (A) Assay strategy. Test compounds were added to ScN2a cells in 96-well microtiter plates. For each compound, cytotoxicity was measured by a calcein-AM assay, and the effect on PrPSc levels was detected by ELISA following PK digestion and PTA precipitation. (B and C) Plate layout and sample data for cytotoxity (B) and antiprion activity (C) experiments. Images were prepared using JColorGrid (9). As controls, each plate included empty wells, wells containing cells with no compound added, and wells containing cells with quinacrine added. All ELISA measurements were normalized to the positive control. (D) Assay linearity. ScN2a cells were mixed with uninfected N2a cells at various ratios, and PrPSc was measured using the HTS protocol. (E and F) Assay variability. Z′ measurements were plotted for each experimental plate for cytotoxicity (E) and PrPSc level (F) measurements.

In order to assess the linearity of the assay, ScN2a cells were mixed with uninfected N2a cells at various ratios after dissociation from culture plates. The mixed dissociated cultures were lysed, and levels of PK-resistant PrPSc were measured using the HTS protocol described above. The results indicate that the PrPSc measurements had a linear range of at least one order of magnitude and the measured signal had not reached saturation in the fully infected samples (Fig. 1D). For both the cytotoxicity and antiprion activity measurements, the intraplate percent coefficient of variance (%CV) was less than 10%, and the Z′ was typically in the range of 0.7 to 0.8 (Fig. 1E and F).

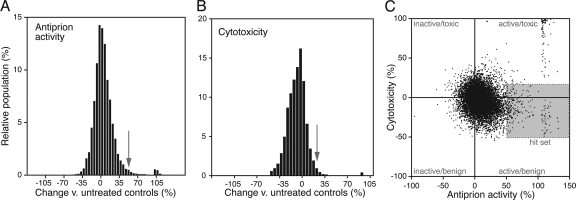

In the primary screening, we evaluated 10,135 unique compounds, encompassing mostly new chemical entities with diverse backbone chemistries and including some known bioactive compounds and FDA-approved drugs (see the supplemental material). The effect of each compound on the PrPSc load and viability of ScN2a cells was measured as described above (Fig. 2). We defined the primary hit set as compounds that induced a >50% decrease in the PrPSc load without reducing the viability of the cells by more than 30%. Of those screened, 156 compounds met these criteria. This set was subsequently retested to exclude experimental false positives, and 121 compounds fulfilled the hit criteria upon retest.

FIG. 2.

Signal distribution of PrPSc level (A) and cyotoxicity (B) measurements. The hit set (C) was defined as compounds that induced a >50% decrease in the PrPSc load (arrow in panel A) without reducing the viability of the cells by more than 30% (arrow in panel B).

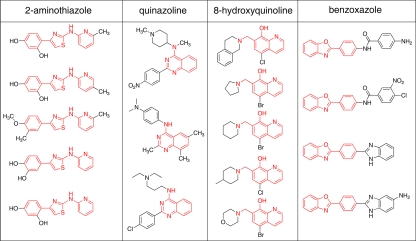

The confirmed hits were grouped into structurally related classes. Four structural classes were defined by three or more individual primary hits: 2-aminothiazoles, quinazolines, hydroxyquinolines, and benzoxazoles (Fig. 3). Quinoline compounds had been shown previously to be active in ScN2a cells (11, 15), and the benzoxazoles bear resemblance to dianilinophthalimides that have been shown have antiprion activity in vitro (5, 24). Here, we chose to concentrate on the 2-aminothiazole scaffold based on its “lead likeness,” its synthetic tractability, and the presence of initial SAR trends that informed further optimization studies (see below).

FIG. 3.

Structural classes with three or more primary hits. The common chemical scaffold is shown in red.

Aminothiazoles in general exhibit a diverse pharmacology and generally favorable in vivo properties, including good bioavailability. Numerous kinase inhibitors based on the aminothiazole scaffold have been described, including preclinical-stage inhibitors of VEGFR-2 kinase (2) and, most notably, the clinically used Src family kinase inhibitor Dasatinib (4). The aminothiazole ring system also figures prominently in recently described adenosine-receptor antagonists (17, 23). In a recent report (7), a small subset of diphenylthiazole analogs was shown to bind human PrPC in vitro and to inhibit PrPSc formation at micromolar concentrations in a murine cell line of nonneuronal origin. Although these compounds contain a thiazole ring, their overall structure and SAR profile clearly suggest a mechanism of action distinct from that of the 2-aminothiazoles described here.

At least three potential mechanisms of action exist for active antiprion compounds. They may (i) alter the expression of the PrPC substrate, (ii) directly disaggregate PrPSc, or (iii) inhibit the formation of new PrPSc. Aminothiazoles failed to alter the expression of PrPC in uninfected N2a cells, eliminating the first mechanism of action mentioned above. If aminothiazoles acted to disaggregate PrPSc, we would expect the removal of protease-resistant PrPSc upon the addition of aminothiazoles in both ScN2a cells and ScN2a extracts. Aminothiazoles failed to render PrPSc susceptible to PK digestion when added directly to ScN2a extracts (data not shown). Thus, it is seems likely that aminothiazoles inhibit PrPSc formation. Whether this occurs by direct interaction with PrP or through the inhibition of a required auxiliary factor remains to be determined.

SAR studies.

We conducted a survey of commercially available aminothiazoles structurally similar to the aminothiazole HTS hits (Table 1). To establish the antiprion activity and general cytotoxicity of the commercial aminothiazoles, we used dose-response curves to calculate EC50 (50% effective concentration) and LD50 (50% lethal dose) values. Within this data set, some SAR trends could be discerned. With respect to A-ring substitution, the presence of a heteroatom at the C-3 and/or C-4 positions appeared to be important for bioactivity. The N-acetyl-substituted analog 3 retained an antiprion effect, indicating that the presence of phenolic (or catechol) functionality is not required for activity. However, the poor activity of more-lipophilic analogs, such as 6 and 7, suggests the possible importance of a hydrogen bond donor at the 4 position of the A ring. With respect to C-ring substitution, we found that methyl-substituted pyridine seemed to confer a more potent effect than the unsubstituted congener (compare analogs 1 and 4). Arylsulfonamide 5 afforded reasonable activity, while analogs bearing a benzoic acid C-ring type (analogs 8 and 9) showed no antiprion effect at the highest concentration tested, possibly due to poor membrane permeability for these carboxylate-substituted analogs.

TABLE 1.

Antiprion activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (LD50) of commercially available aminothiazoles

In any drug discovery program, a significant attrition rate is expected when translating novel therapeutics from cell-based systems to animal models. Most cell models represent an oversimplified representation of the in vivo pathology, and cell-based screenings do not select for many critical properties of an effective drug. In the case of scrapie-infected mouse neuroblastoma cells, perhaps the most important requirement that is not evaluated is the ability of a compound to effectively cross the blood-brain barrier. The lack of effective delivery to the central nervous system may account for the failure of a number of putative drugs that have proven efficacious in cell culture. More worrisome is the possibility that the translational gap is an issue of pharmacodynamics. In other words, the antiprion properties of a “hit” compound may be uniquely evident in the cell-based model because its target is present in cultured cells but is absent in vivo. For example, a given antiprion compound may be targeting molecular species that are irrelevant to the progression of disease in vivo, have a cell-specific mechanism of action, or be effective against only specific prion strains. The in vivo efficacy of aminothiazoles needs to be investigated and optimized by systematic SAR studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG02132, AG10770, and AG021601) and by gifts from the Hillblom Foundation, the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, the Lincy Foundation, the Fight for Mike Homer Program, and Robert Galvin.

We thank Puay Phuan, Fred Cohen, Janice Williams, Brian Wolf, and James Wells.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basler, K., B. Oesch, M. Scott, D. Westaway, M. Wälchli, D. F. Groth, M. P. McKinley, S. B. Prusiner, and C. Weissmann. 1986. Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell 46:417-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borzilleri, R. M., R. S. Bhide, J. C. Barrish, C. J. D'Arienzo, G. M. Derbin, J. Fargnoli, J. T. Hunt, R. Jeyaseelan, Sr., A. Kamath, D. W. Kukral, P. Marathe, S. Mortillo, L. Qian, J. S. Tokarski, B. S. Wautlet, X. Zheng, and L. J. Lombardo. 2006. Discovery and evaluation of N-cyclopropyl-2,4-difluoro-5-((2-(pyridin-2-ylamino)thiazol-5-ylmethyl)amino)benzamide (BMS-605541), a selective and orally efficacious inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. J. Med. Chem. 49:3766-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler, D. A., M. R. D. Scott, J. M. Bockman, D. R. Borchelt, A. Taraboulos, K. K. Hsiao, D. T. Kingsbury, and S. B. Prusiner. 1988. Scrapie-infected murine neuroblastoma cells produce protease-resistant prion proteins. J. Virol. 62:1558-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das, J., P. Chen, D. Norris, R. Padmanabha, J. Lin, R. V. Moquin, Z. Shen, L. S. Cook, A. M. Doweyko, S. Pitt, S. Pang, D. R. Shen, Q. Fang, H. F. de Fex, K. W. McIntyre, D. J. Shuster, K. M. Gillooly, K. Behnia, G. L. Schieven, J. Wityak, and J. C. Barrish. 2006. 2-Aminothiazole as a novel kinase inhibitor template. Structure-activity relationship studies toward the discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methylphenyl)-2-[[6-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl)]-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinyl]amino)]-1,3-thiazole-5-carboxamide (Dasatinib, BMS-354825) as a potent pan-Src kinase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 49:6819-6832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng, B. Y., B. H. Toyama, H. Wille, D. W. Colby, S. R. Collins, B. C. H. May, S. B. Prusiner, J. Weissman, and B. K. Shoichet. 2008. Small-molecule aggregates inhibit amyloid polymerization. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4:197-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaemmaghami, S., P. W. Phuan, B. Perkins, J. Ullman, B. C. May, F. E. Cohen, and S. B. Prusiner. 2007. Cell division modulates prion accumulation in cultured cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17971-17976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heal, W., M. J. Thompson, R. Mutter, H. Cope, J. C. Louth, and B. Chen. 2007. Library synthesis and screening: 2,4-diphenylthiazoles and 2,4-diphenyloxazoles as potential novel prion disease therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 50:1347-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiao, K., H. F. Baker, T. J. Crow, M. Poulter, F. Owen, J. D. Terwilliger, D. Westaway, J. Ott, and S. B. Prusiner. 1989. Linkage of a prion protein missense variant to Gerstmann-Sträussler syndrome. Nature 338:342-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joachimiak, M. P., J. L. Weisman, and B. C. H. May. 2006. JColorGrid: software for the visualization of biological measurements. BMC Bioinformatics 7:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kocisko, D. A., G. S. Baron, R. Rubenstein, J. Chen, S. Kuizon, and B. Caughey. 2003. New inhibitors of scrapie-associated prion protein formation in a library of 2,000 drugs and natural products. J. Virol. 77:10288-10294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korth, C., B. C. H. May, F. E. Cohen, and S. B. Prusiner. 2001. Acridine and phenothiazine derivatives as pharmacotherapeutics for prion disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9836-9841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenfels, R., W. E. Biddison, H. Schulz, A. B. Vogt, and R. Martin. 1994. CARE-LASS (calcein-release-assay), an improved fluorescence-based test system to measure cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J. Immunol. Methods 172:227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masters, C. L., and E. P. Richardson, Jr. 1978. Subacute spongiform encephalopathy Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease—the nature and progression of spongiform change. Brain 101:333-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May, B. C. H., J. A. Zorn, J. Witkop, J. Sherrill, A. C. Wallace, G. Legname, S. B. Prusiner, and F. E. Cohen. 2007. Structure-activity relationship study of prion inhibition by 2-aminopyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile-based compounds: parallel synthesis, bioactivity and in vitro pharmacokinetics. J. Med. Chem. 50:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami-Kubo, I., K. Doh-Ura, K. Ishikawa, S. Kawatake, K. Sasaki, J. Kira, S. Ohta, and T. Iwaki. 2004. Quinoline derivatives are therapeutic candidates for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J. Virol. 78:1281-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan, K.-M., M. Baldwin, J. Nguyen, M. Gasset, A. Serban, D. Groth, I. Mehlhorn, Z. Huang, R. J. Fletterick, F. E. Cohen, and S. B. Prusiner. 1993. Conversion of α-helices into β-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:10962-10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Press, N. J., R. J. Taylor, J. D. Fullerton, P. Tranter, C. McCarthy, T. H. Keller, L. Brown, R. Cheung, J. Christie, S. Haberthuer, J. D. Hatto, M. Keenan, M. K. Mercer, N. E. Press, H. Sahri, A. R. Tuffnell, M. Tweed, and J. R. Fozard. 2005. A new orally bioavailable dual adenosine A2B/A3 receptor antagonist with therapeutic potential. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15:3081-3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prusiner, S. B. 1991. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 252:1515-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prusiner, S. B. 1987. Prions causing degenerative neurological diseases. Annu. Rev. Med. 38:381-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prusiner, S. B. 2001. Shattuck lecture: neurodegenerative diseases and prions. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1516-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prusiner, S. B., and M. R. Scott. 1997. Genetics of prions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31:139-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevitt, C. R., and J. Collinge. 2006. A systematic review of prion therapeutics in experimental models. Brain 129:2241-2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Muijlwijk-Koezen, J. E., H. Timmerman, R. C. Vollinga, J. Frijtag von Drabbe Kunzel, M. de Groote, S. Visser, and A. P. IJzerman. 2001. Thiazole and thiadiazole analogues as a novel class of adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 44:749-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, H., M. L. Duennwald, B. E. Roberts, L. M. Rozeboom, Y. L. Zhang, A. D. Steele, R. Krishnan, L. J. Su, D. Griffin, S. Mukhopadhyay, E. J. Hennessy, P. Weigele, B. J. Blanchard, J. King, A. A. Deniz, S. L. Buchwald, V. M. Ingram, S. Lindquist, and J. Shorter. 2008. Direct and selective elimination of specific prions and amyloids by 4,5-dianilinophthalimide and analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7159-7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.