Abstract

Objectives

To compare the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) with the Medicare Advantage (MA) plans with regard to health outcomes.

Data Sources

The Medicare Health Outcome Survey, the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees, and the Ambulatory Care Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (Fiscal Years 2002 and 2003).

Study Design

A retrospective study.

Extraction Methods

Men 65+ receiving care in MA (N=198,421) or in VHA (N=360,316). We compared the risk-adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health at 2-years follow-up. We computed hazard ratio (HR) for 2-year mortality.

Principal Findings

Veterans had a higher adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better PCS compared with MA participants (VHA 69.2 versus MA 63.6 percent, p<.001). VHA patients had a higher adjusted probability than MA patients of being alive with the same or better MCS (76.1 versus 69.6 percent, p<.001). The HRs for mortality in the MA were higher than in the VHA (HR, 1.26 [95 percent CI 1.23–1.29]).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the VHA has better patient outcomes than the private managed care plans in Medicare. The VHA's performance offers encouragement that the public sector can both finance and provide exemplary health care.

Keywords: Health outcomes, system comparison, quality of care

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States and provides health care to an aging veteran population (Ohldin et al. 2002). In 1995, VHA launched a major health care transformation by adopting managed care principles (Flynn, McGlynn, and Young 1997). It included the use of information technology, measurement and reporting of performance, and integration of services and realigned payment policies (Kizer, Demakis, and Feussner 2000). By 2000, the VHA performance as measured by processes of care was better than that in the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) program and in commercial managed care plans (Jha et al. 2003; Asch et al. 2004;). However, whether this improvement has extended beyond processes of care and into patient outcomes has not yet been fully examined.

The few studies that have compared patient outcomes in the VHA with other health care systems used data collected in the early stages of the VHA transformation. The evidence on health outcomes for the VHA is mixed. For example, using data from 1993 to 1996, Rosenthal, Kaboli, and Barnett (2003) found that the VHA had higher mortality rates after coronary artery bypass grafting when compared with private sector hospitals serving the same health care market. Landrum et al. (2004) found that elderly male veterans hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction in a VHA facility between October 1, 1996, and September 30, 1999, had higher mortality when compared with FFS Medicare patients. Studies that used data collected in the late 1990s found differences in risk-adjusted mortality that favored the VHA when compared with Medicare programs and private sector hospitals (Petersen et al. 2000; Selim et al. 2006; Vaughan-Sarrazin, Wakefield, and Rosenthal 2007;). These contrasting findings leave unresolved questions regarding how outcomes in the VHA compare to that in other systems. The answer is likely to depend on which systems of care are studied, whether one compares overall outcomes for patients or outcomes regarding particular health conditions, as well as the specific metrics that are used.

In a prior study that used data collected between 1998 and 2000, we compared the VHA and the Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (Selim et al. 2007). This comparison was relevant because MA is a Medicare program that provides comprehensive health services to 4.6 million patients (12 percent of the Medicare population) through contracted private managed care organizations (MCOs) throughout the United States (Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services, HHS 2005). The MCOs are heterogeneous and we refer to them collectively as MA. We found that the adjusted probabilities of being alive with the same or better physical health at 2-years follow-up were comparable between the VHA and the MA (63.6 and 64.4 percent, respectively). The adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better mental health at 2-years follow-up in the VHA was significantly higher than in the MA; however, the magnitude of the difference was small (71.8 versus 70.1 percent, respectively). This cross-system comparison study was made at an early stage of the VHA transformation and was based on a limited number of patients. Given the continuing improvements in the VHA in the management of patients with chronic conditions (Asch et al. 2004; Kerr et al. 2004;), it is possible that the results would be different with the use of contemporary health outcome databases (Higashi et al. 2005). A study with a larger number of patients might also reveal differences in outcomes for certain vulnerable subpopulations that may be more susceptible to variations in quality of care, such as older patients, patients with multiple medical problems, or racial/ethnic minorities.

In the present study, we sought to verify and extend the cross-system comparisons between the VHA and MA using more contemporary health outcome data and a larger number of patients. We gave special consideration to particular subpopulations that may be at the highest risk of poor health outcomes and in which the VHA has placed a special emphasis on improving care (Asch et al. 2006).

METHODS

Study Population

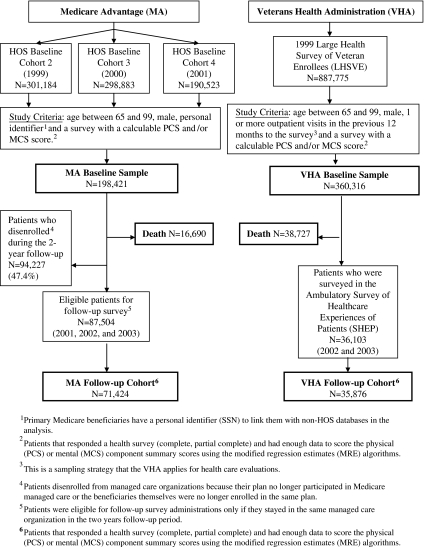

The study population from each health care system was restricted to a comparable subset (Figure 1). The MA population was from three cohorts of the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (HOS): cohorts 2 (1999–2001), 3 (2000–2002), and 4 (2001–2003). The Medicare HOS randomly selected a cohort of 1,000 beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled for at least 6 months from each of the Medicare MCOs (HEDIS® 2003). With the exception of a few specific contract types, all Medicare MCOs participated. The response rates were 66.5, 71, and 68.4 percent at baseline and 84, 77.1, and 78.4 percent at follow-up for cohorts 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The MA population was limited to those beneficiaries aged 65–99 who had person-level identifiers needed to link the HOS data to other databases. Given the disproportionate male representation in the VHA cohort (97.9 percent VHA male patients versus 51.6 percent MA male patients), both MA and VHA analyses were limited to male patients.

Figure 1.

Medicare Advantage and Veterans Health Administration Populations

The MA population began with a baseline sample of 198,421 male seniors who had filled out the HOS survey and who had enough data to calculate physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health scores using a previously validated modified regression estimation (MRE) algorithm for missing data (Centers of Medicaid and Medicare Services 2007a). Among the 198,421 Medicare beneficiaries, 16,690 (8.4 percent) died during a 2-year follow-up period. Only Medicare beneficiaries who remained in Medicare managed care (N=87,504) were surveyed at 2 years. Among the 87,504 patients who were surveyed at follow-up, 71,424 had enough SF-36® data to calculate the PCS and MCS scores using the MRE algorithm.

The VHA population was derived from the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees (LHSVE), a cross-sectional health survey administration (Perlin et al. 2000). The 1999 LHSVE randomly selected a total of 1.5 million veterans from the enrollment file of 3,613,877 individuals. The enrollment file consisted of all veterans registered with the VHA for medical care. The baseline survey administration took place between July 1999 and January 2000. The response rate was 63.1 percent. For the purpose of this study, the analyses were limited to male veterans aged 65–99 who had 1 or more outpatient visits in the previous 12 months and had enough data to calculate PCS and MCS scores using the MRE algorithm (Kazis et al. 2004b). Thus, the VHA baseline sample consisted of 360,316 elderly male veterans. Among the 360,316 veterans, 38,727 (10.6 percent) died during a 2-year follow-up period. The VHA follow-up sample was derived from the Ambulatory Care Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP), which is a patient-centered initiative by the Office of Quality and Performance to assess satisfaction, functional status, and health behavior information from veterans who obtain care in the VHA (Wright et al. 2006). The SHEP had a response rate of 70.3 percent. Among the 360,316 patients from our baseline cohort, we found that 36,103 veterans were included in SHEP during the fiscal years 2002 and 2003. Only three patients did not respond to the survey. Of the 36,100 veterans, 35,876 had enough data to calculate PCS or MCS scores using the MRE algorithm (Centers of Medicaid and Medicare Services 2007b).

Tables SA1 and SA2 show the comparisons of baseline patient characteristics between the beneficiaries who stayed (enrollees) and those who did not stay (disenrollees) in MA at 2 years and veterans who were surveyed in SHEP and those who were not surveyed. Although the patient characteristics differences were statistically significant, the magnitude of the differences was very small, thus indicating that MA enrollees and disenrollees were similar as were veterans who were surveyed and not surveyed in SHEP.

Survey Methods

The Medicare HOS used the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36®) Health Survey at baseline and at follow-up to measure health status (Gandek et al. 2004). For the VHA, the Veterans RAND 36-Item Health Survey (VR-36) was used for baseline health status, and the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) was used for follow-up (Kazis et al. 2004a). They differ from the SF-36® in the use of five-point response choices for the role limitations due to physical problems and the role limitations due to emotional problems. There are validated conversion formulas that allow for comparisons of VR-36 and VR-12 scores to those from the SF-36® (Kazis et al. 2004b). We summarized the health surveys into physical (PCS) and mental component (MCS) scales by applying a linear t-score transformation with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 based on the 1990 U.S. population norms (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller 1994, 1995). We accounted for the differences in follow-up sampling strategies between the VHA and the MA by applying sampling weights to the PCS and MCS scores.

Outcome Measures

Based on the concept that patient health lies on a continuum from well-being to death, we used three outcomes: (1) the probability of being alive with the same or better (than would be expected by chance) PCS at 2 years, (2) the probability of being alive with the same or better (than would be expected by chance) MCS at 2 years, and (3) 2-year mortality. A 2-year follow-up was selected because studies have shown significant changes in health status for this duration (Lorig et al. 2001). The composite outcome measures of being alive with “the same or better” PCS (or MCS) at follow-up were selected because they reflect the health care goal of maintaining or improving the physical and mental health status of elderly patients (Cohen et al. 2002). The cut-off points for the operational definition of change were “two standard errors of the measurement” (SEM) for a single score or 1.414 standard errors of change. We have applied this cut-off methodology for the outcome metrics because changes of this magnitude have been shown to be clinically relevant (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller 1994) and have been validated in previous studies (Ware et al. 1996). Mortality, our other outcome, is a measure that is particularly relevant to elderly patients and might reflect potentially poor quality of care (Reason 2000). We used the Death Master File from the Social Security Administration to ascertain vital status (Schall et al. 2001).

Case Mix Variables for Risk-Adjustment

Based on prior work (Selim et al. 2007), we used three domains of risk: sociodemographics, comorbidities, and baseline health status. Since the risk for health outcomes differs by demographic subgroup, we selected the following sociodemographic variables: age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income (Williams 1996). Because substantial variations in health status among patients with different diagnoses exist, we selected a group of conditions that are commonly encountered in clinic visits and are known to be major indicators of health status (Bayliss et al. 2004). These are self-reported diagnoses of coronary artery disease (CAD)/myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, and cancer (other than skin cancer). We included baseline PCS and MCS scores in the risk-adjustment models for being alive because they are important predictors of survival (Dorr et al. 2006). The baseline health scores were not included in the change in PCS (or MCS) models because their coefficients are influenced by the baseline score measurement error and intertemporal correlation. All the case mix variables in our analyses correspond to characteristics of individual patients obtained in their baseline surveys.

Statistical Analysis

In order to examine the differences in patient characteristics between MA and VHA, we compared them in terms of sociodemographics, comorbid conditions, and PCS and MCS scores. Because social circumstances are known to affect medical outcomes, a social disadvantage index was generated and included minority, unmarried, <12 years of education, and income less than U.S.$20,000 (Anand et al. 2006). To compare the differences in the two study groups at baseline, we used chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

To compare change in health status between the MA and VHA, we applied a previously validated methodology (Selim et al. 2007). We first calculated the change in PCS (or MCS) points per unit of time for each health care system. We took the difference between the PCS (or MCS) baseline and follow-up scores and divided it by the median difference, in years, between the baseline and follow-up surveys (in the MA and the VHA these numbers were 2.09 and 3.29 years, respectively). The reason for using the median time was that late surveys tend to be different (in the HOS they tend to be sicker respondents) and follow-up protocols vary. This gave us the change in points per year, which we multiplied by 2 to get the change in points per 2 years. If the change in points has mean μD and standard deviation σD and the percentage the same or better has mean μP and standard deviation σP, then the conversion formula to change an average point difference D into a percentage change P is

The terms were rearranged to a more familiar linear equation form, P=aD+b, where P is the probability of PCS (or MCS) the same or better; D is the mean change in PCS (or MCS) points per 2 years for each health care system, which was adjusted using least-squares means to control for sociodemographics and comorbidities; and a is the slope; and b is the intercept. We computed the “slope” and the “intercept” values using harmonic regressions because neither x (change in PCS [or MCS] points per 2 years) nor y (probability of PCS [or MCS] the same or better) is thought of as the dependent variable (Shalabh 2001). It is the harmonic mixture of regressing y on x and x on y. We applied the harmonic regressions to the HOS cohort because we needed to look to some unit of aggregation above the individual respondent in order to do the conversion and the HOS provides a large dataset naturally organized into managed care plans. For example, if PCS goes down by 1 point per year on the average, the converted probability of PCS the same or better is 5.03 (−2)+80.61=70.55 percent. We then combined the probability of PCS (or MCS) the same or better and the probability of being alive (or 1-probability of death) using the following formulas (Diehr et al. 2003):

We computed the probability of being alive separately from the probability of having the same or better PCS (or MCS) at 2 years for two reasons. First, the population on which the vital status can be assessed with reasonable case mix controls consists of all persons who completed the baseline survey. This is a different sample from those who were followed up with survey administrations. Second, the vital status came from a source that was independent from the survey administrations, and therefore did not share any correlated error with baseline assessments. Thus, we used the full baseline sample of 360,316 VHA and 198,421 MA patients for the calculation of the probability of being alive, which was adjusted for sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income), comorbidities, and baseline health status (PCS and MCS scores). For the calculation of the probability of having the same or better PCS (or MCS) at 2 years, we used the follow-up sample of 35,876 VHA and 71,424 MA patients. We compared the adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better PCS (or MCS) at 2 years between the VHA and MA using tests of significance based on the standard error of the difference:

|

We also conducted additional analysis applying propensity score matching to examine patients who look alike in all observed characteristics.

We used Cox regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of dying with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) for the MA compared with the VHA patients. We calculated the adjusted 2-year mortality rates for each health care system as its observed mortality rate divided by its expected mortality rate, multiplied by the mean of the observed mortality rate for all study patients across both systems.

We also examined subpopulations defined by specific patient characteristics since there might be especially large differences between the VHA and the MA, including age (75 and older), ethnicity/race (whites, African Americans, and Hispanics), and selected chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, CAD/myocardial infarction, and CHF). The stratification variables were not included within the subgroup analyses as risk adjustors. The test of significance was adjusted for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction. We divided 0.05 by the 20 group comparisons of the probability of being alive with the same or better PCS (or MCS) at 2-years follow-up between the MA and VHA, resulting in a significant level of 0.0025 as the cut-off.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of patients in MA and VHA. Mean age was 74.0 (SD±6) for the MA patients, while it was 73.7 (SD±5) for the VHA patients. The VHA patients, in comparison with MA plan patients, were significantly more likely to be nonwhites (17.8 versus 11.0 percent), were less likely to be married (68.9 versus 77.4 percent), were more likely to have <12 years of education (38.9 versus 30.7 percent), and were more likely to earn an income of less than U.S.$20,000 (65.6 versus 41.9 percent). Overall, the VHA had a higher level of social disadvantage than MA.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Medicare Advantage (MA) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Patients

| Medicare Advantage (N=198,421) | Veterans Health Administration (N=360,316) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 74.0 (± 6) | 73.7 (± 5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Whites | 89.0% | 82.2% |

| African Americans | 6.4% | 8.7% |

| Hispanics | 1.8% | 4.8% |

| Other | 2.8% | 4.3% |

| Marital status (married) | 77.4% | 68.9% |

| Education (<12 years) | 30.7% | 38.9% |

| Income (<U.S.$20,000) | 41.9% | 65.6% |

| Social disadvantage index* | ||

| 0 | 38.1% | 17.5% |

| 1 | 29.6% | 33.5% |

| 2 | 22.0% | 31.2% |

| 3 | 8.7% | 14.6% |

| 4 | 1.6% | 3.3% |

Note. All comparisons between MA and VHA were significant at <.0001

The social disadvantage index includes minority, unmarried, <12 years of education, and income less than U.S.$20,000. A higher score indicates greater disadvantage.

Table 2 shows the clinical features of patients in MA and VHA at baseline. The VHA patients had a significantly higher disease burden than the MA patients. The VHA patients were more likely to have four or more chronic medical conditions when compared with MA patients (23.5 versus 9.5 percent, respectively). VHA patients, in comparison with MA plan patients, were significantly more likely to have hypertension (65.7 versus 52.2 percent), coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction (28.3 versus 15.7 percent), diabetes (28.2 versus 19.8 percent), COPD/asthma (25.8 versus 13.5 percent), cancer (19.7 versus 15.1 percent), and stroke (15.3 versus 9.3 percent). VHA patients, in comparison with MA plan patients, had significantly worse physical health (PCS scores, 35.7 versus 43.3) and mental health (MCS scores, 45.2 versus 51.9) at baseline.

Table 2.

Clinical Features of Medicare Advantage (MA) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Patients

| Medicare Advantage (N=198,421) | Veterans Health Administration (N=360,316) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of comorbidities (range 0–8) | ||

| 0 | 25.9% | 12.6% |

| 1 | 32.4% | 25.1% |

| 2 | 21.2% | 23.0% |

| 3 | 11.2% | 15.8% |

| 4 or more | 9.5% | 23.5% |

| Diabetes | 19.8% | 28.2% |

| Hypertension | 52.2% | 65.7% |

| Angina | 20.7% | 34.5% |

| Coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction | 15.7% | 28.3% |

| Congestive heart failure | 8.7% | 24.9% |

| Stroke | 9.3% | 15.3% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma | 13.5% | 25.8% |

| Cancer | 15.1% | 19.7% |

| Baseline physical health-PCS, points (SD)* | 43.3 (± 11) | 35.7 (± 10) |

| Baseline mental health | ||

| MCS, points (SD)* | 51.9 (± 10) | 45.2 (± 13) |

Note. All comparisons between MA and VHA were significant at <.0001.

A lower number is indicative of poor health status for MCS and PCS.

Table 3 shows that the adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better PCS at 2-years follow-up was significantly higher in the VHA when compared with the MA (69.2 versus 63.6 percent, respectively). The adjusted probability of being alive with the same or better MCS at 2-years follow-up in the VHA was also significantly higher than in the MA (76.1 versus 69.6 percent, respectively). The propensity score matching analysis showed comparable results (the probability of being alive with the same or better PCS was 69.3 versus 63.5 percent and the probability of being alive with the same or better MCS was 75.9 versus 69.6 percent for the VHA and MA, respectively). The adjusted 2-year mortality rates were 11.8 and 9.9 percent for the MA, and VHA, respectively, with a significantly higher HR for mortality in the MA compared with the VHA (HR, 1.26 [95 percent CI 1.23–1.29]).

Table 3.

Change in Health Status in the Medicare Advantage (MA) and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

| Health Care System | MA | VHA |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline sample | 198,421 | 360,316 |

| Follow-up cohort | 71,424 | 35,876 |

| Adjusted probability of being alive at 2 years* | 88.1% | 90.1% |

| Adjusted probability of the same or better PCS at 2 years† | 72.9% | 76.8% |

| Adjusted probability of the same or better MCS at 2 years† | 79.0% | 84.4% |

| Adjusted probability of being alive* with the same or better PCS† at 2 years‡ | 63.6% | 69.2% |

| Adjusted probability of being alive* with the same or better MCS† at 2 years‡ | 69.6% | 76.1% |

| Propensity score matching | ||

| Probability of being alive with the same or better PCS at 2 years | 63.5% | 69.3% |

| Probability of being alive with the same or better MCS at 2 years | 69.6% | 75.9% |

| Mortality | ||

| 2-years adjusted mortality rates* | 11.8% | 9.9% |

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | 1.26 (1.23–1.29) | 1 |

The adjustment variables for survival/mortality included sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma, and cancer [other than skin cancer]), and baseline health status (PCS and MCS scores).

The adjustment variables for PCS (or MCS) the same or better included sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income) and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma, and cancer [other than skin cancer]).

All comparisons between MA and VHA were significant at p-value <.001.

We found that across the board, subgroups of vulnerable male patients had better outcomes in the VHA compared with those in MA (Table 4). The adjusted probabilities of being alive with the same or better PCS (or MCS) at 2 years in the VHA were also significantly higher than those in the MA across the very old patients (75 and older) as well as the race/ethnicity groups, including whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. Similar findings are also seen across patients with selected chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, CAD/myocardial infarction, and CHF. The magnitude of the differences in the percentage of patients who were either “alive with the same or better PCS” or “alive with the same or better MCS” at 2-years follow-up ranged from 3 to 10 percent higher in the VHA when compared with the MA. The HRs for mortality in the MA were significantly higher than those in the VHA across all subgroups.

Table 4.

Change in Health Status in the Medicare Advantage (MA) and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) by Subpopulations

| Subpopulations | Health Care System | Baseline Sample | Follow-up Cohort | Adjusted Probability of Being Alive* with the Same or Better PCS† at 2 Years‡ (%) | Adjusted Probability of Being Alive* with the Same or Better MCS† at 2 Years‡ (%) | Adjusted Mortality Rates* (%) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 75 and older | MA | 77,405 | 34,216 | 68.0 | 73.7 | 18.2 | 1.48 (1.43–1.52) |

| VHA | 159,159 | 14,647 | 72.4 | 79.1 | 13.1 | 1 | |

| Whites | MA | 176,621 | 78,147 | 64.1 | 69.6 | 11.9 | 1.26 (1.23–1.30) |

| VHA | 294,108 | 30,622 | 69.1 | 76.2 | 10.0 | 1 | |

| African Americans | MA | 12,688 | 4,981 | 66.2 | 68.4 | 11.9 | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) |

| VHA | 31,276 | 2,248 | 70.8 | 73.9 | 10.3 | 1 | |

| Hispanics | MA | 3,557 | 1,519 | 65.6 | 69.8 | 9.7 | 1.36 (1.16–1.60) |

| VHA | 17,012 | 1,508 | 71.9 | 77.0 | 7.3 | 1 | |

| Hypertension | MA | 101,897 | 44,505 | 64.5 | 69.4 | 12.2 | 1.24 (1.20–1.28) |

| VHA | 231,265 | 23,728 | 68.8 | 76.1 | 10.2 | 1 | |

| Diabetes | MA | 38,754 | 16,229 | 62.2 | 66.6 | 14.9 | 1.24 (1.19–1.29) |

| VHA | 98,228 | 10,148 | 67.4 | 73.9 | 12.4 | 1 | |

| Coronary artery disease | MA | 30,336 | 12,564 | 62.1 | 66.0 | 16.7 | 1.25 (1.19–1.30) |

| VHA | 96,927 | 9,903 | 66.6 | 73.9 | 13.8 | 1 | |

| Congestive heart failure | MA | 16,765 | 6,322 | 58.4 | 60.4 | 23.3 | 1.28 (1.23–1.34) |

| VHA | 84,415 | 7,732 | 62.8 | 70.8 | 19.0 | 1 |

The adjustment variables for survival/mortality included sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma, and cancer [other than skin cancer]), and baseline health status (PCS and MCS scores).

The adjustment variables for PCS (or MCS) the same or better included sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income) and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma, and cancer [other than skin cancer]).

The stratification variables were not included within the subgroup analyses as risk adjustors.

All comparisons between MA and VHA were significant at p<.0025 based on Bonferroni correction.

DISCUSSION

After adjusting for the higher prevalence of chronic disease and worse self-reported baseline health status in the VHA, we found significant differences in 2-year health outcomes that favor the VHA when compared with the MA. This was true for the average elderly male patient cared for in the VHA as well as for vulnerable subpopulations. This study, based on data collected on males between 1999 and 2003, extends our previous work using data collected between 1998 and 2000 (Selim et al. 2007).

One might argue that the “execution” of the VHA transformation may have contributed to the better health outcomes found in our study. Although each organizational transformation is unique, VHA's experiences offer a number of lessons for future transformations. The transformation framework included the creation of a vision for the future, the adoption of a new organization structure, careful planning and monitoring of performance to achieve system-wide coordination and accountability and the modification in rules and regulations for access to care (Young 2006). The VHA transitioned from a tertiary/specialty and inpatient-based care system delivering care in a traditional professional model into a system focused on ambulatory care. It developed integrated health care networks that have a collective goal of delivering services to a defined population in a coordinated and collaborative manner that maximizes the health care value of the service (Kizer, Demakis, and Feussner 2000). The VHA enhanced equity of access among ethnic minority veterans and mental health care services and implemented a sophisticated electronic health record system that improved quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care (Wooten 2002; Chaudhry et al. 2006; Kressin et al. 2007;).

The magnitude of the VHA's improved performance in the subgroup analysis is not better than in the full VHA sample, indicating that process improvements in the VHA are broad and not limited to an area in which special programs exist. Research studies in documenting and evaluating the transformation have found similarly broad effects when examining the progress and diverse impacts of the overall reorganization and several of its specific elements, including the creation of a seamless continuum of care, making superior quality consistent and demonstrating good value (Feussner, Kizer, and Demakis 2000; Berlowitz et al. 2001; Jha et al. 2003;). Therefore, the creation of a clear vision of the future and a coherent transformation plan having concrete and concise goals and performance measures are essential to a successful health care system based on managed care principles.

There are a number of limitations in this study that might affect our results. First, the MA respondents started with higher scores than the VHA respondents. The reasoning might be that the scores have more to drop in MA because they are higher to start with and would suggest a model where all groups are progressing toward death at a fixed time. We have found that after correcting for regression to the mean effects, those individuals with lower scores start to decline at the same rate or faster than those with higher scores.

Second, the health survey instruments may be insensitive to further decline, which would bias against documenting worsening health status in patients who are already severely ill (“floor effect”). Against this is the finding of other investigators that over half of the patients with low health status were able to report that their health status subsequently declined further (Bindman, Keane, and Lurie 1990).

Third, the two surveys were conducted using different sampling strategies. The MA sample was based on sampling at the plan level, with follow-up survey data subject to continued plan participation in Medicare and the survey respondent's continuous enrollment in the plan. The baseline VHA sample was a population-based survey of all VHA patients and the follow-up sample were those in SHEP. Figure SA1 indicates that MA baseline cohort and those who were surveyed at follow-up were similar as were VHA baseline cohort and those who were surveyed in SHEP. The time between assessments was also different in the two systems. Therefore, the estimates of changes in health status at 2 years are a linear interpolation of changes.

Fourth, this study examines only male patients. There may be differences in outcomes between men and women within the VHA and MA, and for women, comparisons of outcomes between the VHA and MA may differ from that seen in men. Further research is needed to assess the effect of systems of care on outcomes for women.

Fifth, controlling for sociodemographics and comorbid illnesses explained only a fraction of the variance in the change in PCS and MCS. The pseudo R2 was 0.0021 for PCS the same or better and 0.0039 for MCS the same or better. The same has been true in other studies (Bayliss et al. 2004). The mortality model had a c-statistic (discriminative power) of 0.747, which was equal or superior to values obtained in risk-adjusted mortality models for inpatient populations (Best and Cowper 1994; Schneeweiss et al. 2003;). Our risk-adjustment methodology did not control for unobservable variables such as quality of care that could be correlated with the health care systems.

Sixth, our outcome measures combine respondents with good health status at baseline who do not decline over the time-frame with respondents in poor health status at baseline who improve. We broke down the composite outcomes into better and same. The categories of change in PCS were classified as (1) “the same” (or unchanged) between −5.66 points and +5.66 points, (2) “better” as >+5.66 points, and (3) “worse” as <−5.66 points. The categories of change in MCS were classified as (1) “the same” (or unchanged) between −6.72 points and +6.72 points, (2) “better” as >+6.72 points, and (3) “worse” as <−6.72 points. The cross-system comparison analysis yielded similar results (Table SA3).

Seventh, MA plans are independent and heterogeneous. In particular, there are those that probably look more like the VHA in terms of integration, use of health information technology, performance monitoring, and financial incentives and others that are probably closer to the unmanaged, FFS population. Further studies are needed to evaluate how differences in the organizational characteristics of variations in MA are associated with variation in and the impact on their performance.

Eighth, our work was limited to the comparison of patient outcomes in different settings of managed care. Some evidence suggests elderly patients with chronic conditions enrolled in Medicare managed care experienced greater declines in physical health than similar persons in Medicare FFS (Shaughnessy, Schlenker, and Hittle 1994; Ware et al. 1996;). More recent studies of the elderly have found no differences between Medicare managed care and FFS with respect to functional declines and to mortality (Retchin et al. 1992; Riley 2000; Porell and Miltiades 2001;). Further research is needed to better understand how these different systems of care affect outcomes.

In summary, our findings indicate that the VHA has better outcomes for men than MA. The VHA's performance offers encouragement that the public sector can both finance and provide exemplary health care. The VHA's experience provides some general, potentially transferable, and useful policy directions that might benefit other health care systems in the public as well as the private sectors.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We thank Dr. Samuel C. Haffer from the Medicare HOS Program Office of Research, Development, & Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for his thorough review of this manuscript.

Disclosures: The research in this article was supported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) under contract numbers 500-00-0055 with NCQA, Office of Quality and Performance (OQP) of the Department of Veterans Affairs, The Center for Health Quality, Outcomes and Economic Research (CHQOER), Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University School of Public Health.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the National Committee for Quality Assurance, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or Boston University.

The SF-36® Health Survey is a registered trademark of the Medical Outcomes Trust.

Supplemental material

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Table SA1: Comparisons of Baseline Patient Characteristics between the Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollees and Disenrollees* in 2 Years.

Table SA2: Comparisons of Baseline Patient Characteristics between Veterans Who Were Surveyed in the Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) and Those Who Were Not Surveyed.

Figure SA1: Baseline PCS and MCS scores for Medicare Advantage (MA) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Populations.

Table SA3: Change in Health Status in the Medicare Advantage (MA) and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Anand SS, Razak F, Davis AD, Jacobs R, Vuskan V, Teo K, Yusuf S. Social Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Disease: Development of an Index and Analysis of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity Effects. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:1239–45. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, Hayward RA, Shekelle P, Rubenstein L, Keesey J, Adams J, Kerr EA. Comparison of Quality of Care for Patients in the Veterans Health Administration and Patients in a National Sample. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch SM. Who Is at Greatest Risk for Receiving Poor-Quality Health Care? New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1147–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss EA, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Jr., Steiner JF. Predicting Declines in Physical Function in Persons with Multiple Chronic Medical Conditions: What We Can Learn from the Medical Problem List. Health Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz DR, Young GJ, Brandeis GH, Kader B, Anderson JJ. Health Care Reorganization and Quality of Care: Unintended Effects on Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Medical Care. 2001;39:138–46. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200102000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best WR, Cowper DC. The Ratio of Observed-to-Expected Mortality as a Quality of Care Indicator in Non-Surgical VA Patients. Medical Care. 1994;32:390–400. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindman AB, Keane D, Lurie N. Measuring Health Changes among Severely Ill Patients. The Floor Phenomenon. Medical Care. 1990;28:1142–52. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services, HHS. Medicare Program; Establishment of the Medicare Advantage Program; Interpretation. Final Rule; Interpretation. Federal Register. 2005;70:13401–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers of Medicaid and Medicare Services. Imputing the Physical and Mental Summary Scores (PCS and MCS) for the MOS SF-36 and the Veterans SF-36 Health Survey in the Presence of Missing Data. 2007a. [accessed on July 30, 2007]. Available at http://www.hosonline.org/surveys/hos/download/HOS_Veterans_36_Imputation.pdf.

- Centers of Medicaid and Medicare Services. Imputing Physical and Mental Summary Scores (PCS and MCS) for the Veterans SF-12 Health Survey in the Context of Missing Data. 2007b. [accessed on July 30, 2007]. Available at http://www.hosonline.org/surveys/hos/download/HOS_Veterans_12_Imputation.pdf.

- Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Systematic Review: Impact of Health Information Technology on Quality, Efficiency, and Costs of Medical Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;14:742–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger N, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C, Pennypacker L, Smith DM, Ainslie N, Hornick T, Brodkin K, Lavori P. A Controlled Trial of Inpatient and Outpatient Geriatric Evaluation and Management. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:905–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P, Patrick DL, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Accounting for Deaths in Longitudinal Studies Using the SF-36: The Performance of the Physical Component Scale of the Short Form 36-Item Health Survey and the PCTD. Medical Care. 2003;41:1065–73. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000083748.86769.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr DA, Jones SS, Burns L, Donnelly SM, Brunker CP, Wilcox A, Clayton PD. Use of Health-Related, Quality-of-Life Metrics to Predict Mortality and Hospitalizations in Community-Dwelling Seniors. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2006;54:667–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feussner JR, Kizer KW, Demakis JG. The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative: From Evidence to Action. Medical Care. 2000;38:I1–6. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn K, McGlynn G, Young G. Transferring Managed Care Principles to VA. Hospital Health Service Administration. 1997;42:323–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandek B, Sinclair SJ, Kosinski M, Ware JE., Jr Psychometric Evaluation of the SF-36 Health Survey in Medicare Managed Care. Health Care Finance Review. 2004;25:5–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the Transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the Quality of Care. New England Journal Medicine. 2003;348:2218–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Lee A, Ren XS, Clark JA, Rogers WH, Spiro A, III, Selim A, Liozer M, Payne SM, Manzell D, Fincke BG. Patient-Reported Measures of Health: The Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2004a;27:70–83. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE. Improving the Response Choices on the Veterans SF-36 Health Survey Role Functioning Scales: Results from the Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2004b;27:263–80. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, Selby JV, Piette JD, Curb JB, Curb WH, Herman WH, Marrero DG, Narayan KM, Safford MM, Thompson T, Mangione CM. Diabetes Care Quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and Commercial Managed Care: The TRIAD Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;14:272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer KW, Demakis JG, Feussner JR. Reinventing VA Health Care: Systematizing Quality Improvement and Quality Innovation. Medical Care. 2000;38(6, suppl 1):I7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, Glickman ME, Peterson ED, Whittle J, Orner MB, Petersen LA. Functional Status Outcomes among White and African-American Cardiac Patients in an Equal Access System. American Heart Journal. 2007;153:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDIS®. Specifications for the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Vol. 6. National Committee for Quality Assurance: Washington, D.C.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi T, Shekelle PG, Adams JL, Kamberg CJ, Roth CP, Solomon DH, Reuben DB, Chiang J, MacLean CH, Chang JT, Young RT, Saliba DM, Wenger NS. Quality of Care Is Associated with Survival in Vulnerable Older Patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143:274–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Zummo R, Chin D, McNeil BJ. Care Following Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Veterans Administration Medical Centers: A Comparison with Medicare. Health Services Research. 2004;39:1773–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Jr., Bandura A, Gonzalez VM, Laurent DD, Holman HR. Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: 2-Year Health Status and Health Care Utilization Outcomes. Medical Care. 2001;39:1217–23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohldin A, Taylor R, Stein A, Garthwaite T. Enhancing VHA's Mission to Improve Veteran Health: Synopsis of VHA's Malcolm Baldrige Award Application. Quality Management in Health Care. 2002;10:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin J, Kazis LE, Skinner KM, Ren XS, Lee A, Rogers WR, Spiro A, III, Selim A, Miller DR. 2000. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores, Veterans SF-36[R], 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees. Executive Report. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Quality and Performance. Washington, DC. May 2000.

- Petersen LA, Normand SL, Daley J, McNeil BJ. Outcome of Myocardial Infarction in Veterans Health Administration Patients as Compared with Medicare Patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:1934–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porell FW, Miltiades HB. Disability Outcomes of Older Medicare HMO Enrollees and Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2001;49:615–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reason J. Human Error: Models and Management. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:768–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retchin SM, Clement DG, Rossiter LF, Brown B, Brown R, Nelson L. How the Elderly Fare in HMOs: Outcomes from the Medicare Competition Demonstrations. Health Services Research. 1992;27:651–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G. Two-Year Changes in Health and Functional Status among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries in HMOs and Fee-for-Service. Health Services Research. 2000;35:44–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal GE, Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ. Differences in Length of Stay in Veterans Health Administration and Other United States Hospitals: Is The Gap Closing? Medical Care. 2003;41:882–94. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall LC, Buchanich JM, Marsh GM, Bittner GM. Utilizing Multiple Vital Status Tracing Services Optimizes Mortality Follow-Up in Large Cohort Studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2001;11:292–6. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Improved Comorbidity Adjustment for Predicting Mortality in Medicare Populations. Health Services Research. 2003;38:1103–20. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim AJ, Kazis LE, Rogers W, Qian S, Rothendler JA, Lee A, Ren XS, Haffer SC, Mardon R, Miller D, Spiro A, III, Selim BJ, Fincke BG. Risk-Adjusted Mortality as an Indicator of Outcomes: Comparison of the Medicare Advantage Program with the Veterans' Health Administration. Medical Care. 2006;44:359–65. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000204119.27597.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim AJ. Change in Health Status and Mortality as Indicators of Outcomes: Comparison between the Medicare Advantage Program and the Veterans Health Administration. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:1179–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalabh Consistent Estimation through Weighted Harmonic Mean of Inconsistent Estimators in Replicated Measurement Error Models. Economic Reviews. 2001;4:507–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy PW, Schlenker RE, Hittle DF. Home Health Care Outcomes under Capitated and Fee-for-Service Payment. Health Care Finance Review. 1994;16:187–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Wakefield B, Rosenthal GE. Mortality of Department of Veterans Affairs Patients Admitted to Private Sector Hospitals for 5 Common Medical Conditions. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2007;22:186–97. doi: 10.1177/1062860607300656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Users's Manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE., Jr. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Tarlor AR. Differences in 4-Year Health Outcomes for Elderly and Poor, Chronically Ill Patients Treated in HMO and Fee-for-Service Systems. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:1039–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Race/ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status; Measurement and Methodological Issues. International Journal of Health Services. 1996;26:483–505. doi: 10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooten AF. Access to Mental Health Services at Veterans Affairs Community-Based Outpatient Clinics. Military Medical. 2002;167:424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SM, Craig T, Campbell S, Schaeter J, Humble C. Patient Satisfaction of Female and Male Users of Veterans Health Administration Services. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(suppl 3):S26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. Transforming Government: The Revitalization of the Veterans Health Administration. 2006. [accessed on November 7, 2008]. Available at http://www.businessofgovernment.org/pdfs/Young_Report.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.