Abstract

Candida glabrata, a fungal strain resistant to many commonly administered antifungal agents, has become an emerging threat to human health. In previous work, we validated that the essential enzyme, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), is a drug target in C. glabrata. Using a crystal structure of DHFR from C. glabrata bound to an initial lead compound, we designed a class of biphenyl antifolates that potently and selectively inhibit both the enzyme and the growth of the fungal culture. In this work, we explore the structure-activity relationships of this class of antifolates with four new high resolution crystal structures of enzyme:inhibitor complexes and the synthesis of four new inhibitors. The designed inhibitors are intended to probe key hydrophobic pockets visible in the crystal structure. The crystal structures and an evaluation of the new compounds reveal that methyl groups at the meta and para positions of the distal phenyl ring achieve the greatest number of interactions with the pathogenic enzyme and the greatest degree of selectivity over the human enzyme. Additionally, antifungal activity can be tuned with substitution patterns at the propargyl and para-phenyl positions.

Keywords: Candida glabrata, crystallography, structure-based drug design, antifolate, DHFR

Introduction

The incidence of invasive mycoses responsible for hospital-acquired bloodstream infections has dramatically increased over the past few decades, primarily because of an expanding population of patients with compromised immune systems (1). Unfortunately, the mortality rate for these fungal infections has also increased from 38 % between 1983 and 1986 to 49 % between 1997 and 2001 (2–4). The ability to effectively diagnose and treat fungal infections has been made more difficult with the emergence of a significant number of drug-resistant strains that are insensitive to the commonly administered antifungal therapeutics such as amphotericin B, fluconazole and itraconazole.

Candida species are the most common opportunistic fungal pathogens in humans, with Candida albicans being the most prevalent pathogen in systemic infections (1, 5). Over the past two decades, there has been a proportional decrease in infections caused by C. albicans and an increase in non-albicans infections. Other species of Candida, primarily C. glabrata, now cause a significant (20–24 %) number of Candida infections (6). Significantly, infections caused by C. glabrata were associated with the highest mortality rates. C. glabrata is less sensitive to amphotericin B and has developed resistance to fluconazole and itraconazole via induction of efflux pumps (7). Cross-resistance between fluconazole and the extended spectrum triazoles has also been observed (1), narrowing the therapeutic window for treating C. glabrata infections.

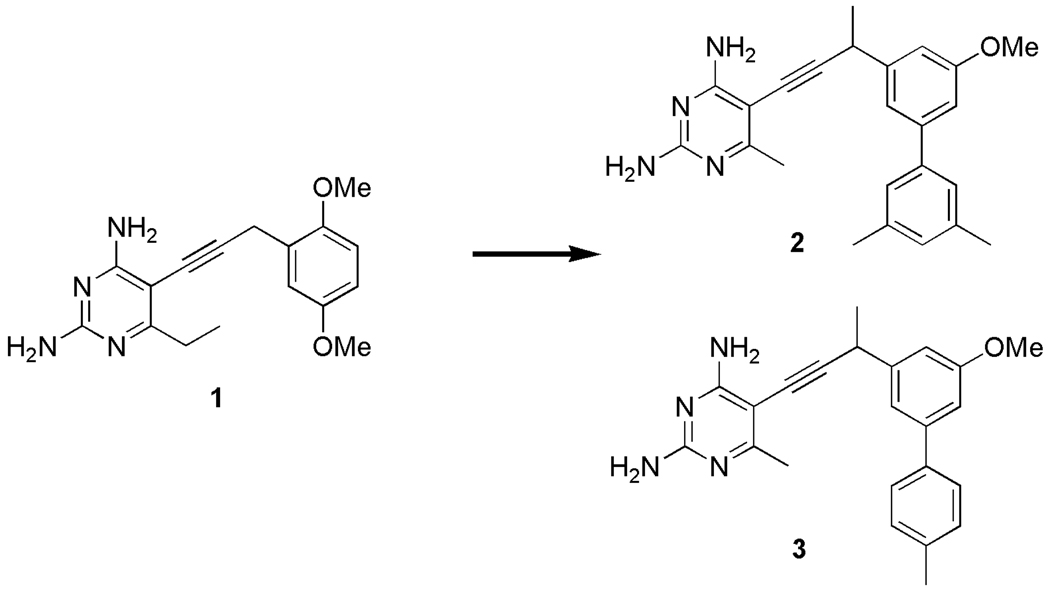

In previous work (8), we validated that the essential enzyme, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), a critical component of the folate biosynthetic pathway, is a target for inhibiting the growth of C. glabrata. Previously, we screened a number of antifolate derivatives that we developed in the laboratory and found that compound 1 (Scheme 1) inhibited the C. glabrata DHFR (CgDHFR) enzyme both potently (IC50 = 8.2 nM) and selectively (156-fold over the human DHFR enzyme). We then determined a high resolution crystal structure of CgDHFR bound to its cofactor, NADPH and compound 1. Using the structural information, we designed and synthesized second generation inhibitors (compounds 2 and 3 in Scheme 1). These biphenyl compounds inhibited CgDHFR with subnanomolar concentrations and increased selectivity to 1300–2300-fold. Furthermore, the compounds inhibited the growth of C. glabrata at levels that are commensurate with clinically used agents.

Scheme 1.

In this work, we present a thorough evaluation of these antifolates as inhibitors of the CgDHFR and human DHFR enzymes as well as the growth of both fungal and human cell lines. Additionally, we present four new high resolution crystal structures with biphenyl derivatives and use the structural information to analyze the basis of the potency and selectivity of the biphenyl compounds. It is apparent from an analysis of these structures that CgDHFR possesses two hydrophobic pockets: one near the propargylic site and a second that houses the distal phenyl ring. Four new inhibitors were designed, synthesized and evaluated to further probe these two critical pockets in the enzyme active site.

Methods and Materials

Protein preparation and crystallization

CgDHFR was expressed and purified as described previously (8); the pure protein was concentrated to 13 mg/mL in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 20 % glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA and 2 mM DTT. Human DHFR was also purified as described previously (8).

CgDHFR was incubated with 1.5 mM NADPH and 1 mM compound (2, 3, 4, or 6) for two hours. Suitable crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method and by mixing equal volumes of protein:ligand with 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.5), 35–40 % PEG 4000 and 0.3 – 0.4 M MgCl2.

Enzyme inhibition assays

Enzyme activity assays were performed by monitoring the rate of enzyme-dependent NADPH consumption at an absorbance of 340 nm over 5 minutes. Reactions were performed in the presence of 50 mM KCl, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. Saturating concentrations of cofactor (100 µM NADPH) and substrate (1 mM DHF) were used with a limiting concentration of enzyme. The IC50 values were determined as an average of 3 measurements.

Antifungal assays

C. glabrata was stored as a suspension in 50 % glycerol at −78 °C. For susceptibility testing, a streak of stock culture was made on SDA agar and grown at 30 °C for 48 h. One pure colony of the test organism was recovered from the plate, suspended in appropriate media and grown in a 5 mL shake flask culture. A sample of the shake flask culture was diluted to 1 × 105 cells/mL in media and added to 96-well test plates (100 µL per well) containing test compounds dispensed in DMSO (1 µL). Amphotericin and ketoconazole were used as controls. After an incubation period determined from the strain specific doubling time, Alamar Blue (10 µL) was added and incubation was continued; each well was scored for dye reduction (9). The MIC value was taken as the lowest concentration of test compound that inhibits growth such that less than 1 % reduction of the blue resazurin (λmax 570 nm) component of the Alamar Blue to the pink resorufin (λmax 600 nm) was observed.

Human cell toxicity assays

Adherent cell lines were maintained in Eagle’s Minimal Essential Media with 2 mM glutamine and Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution adjusted to contain 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10 % fetal calf serum. Fetal calf serum used in these assays was lot matched throughout. All cultures were maintained under a humidified 5 % CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C, had media refreshed twice weekly and were subcultured by trypsinization and resuspension at a ratio of 1:5 each week. Toxicity assays were conducted between passages 10 – 20. Target compound toxicity was measured by incubating the test compound with the cells for four hours, washing the cells and finally treating the cells with Alamar Blue. After 12 – 24 hours the fluorescence of the reduced dye was measured. Fluorescence intensity as a function of test compound concentration was fit to the Fermi equation to estimate IC50 values.

Structure determination

All diffraction data were measured at beamline X29 at NSLS using an ADSC CCD detector. Data were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL2000 (10). Difference Fourier techniques using the model of CgDHFR from the structure of the complex with NADPH:1 to provide initial phase estimates were used to determine the structures of the four complexes. Electron density maps were inspected and models were built using Coot (11). The model was refined using Refmac5 (12) in the CCP4 suite. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 2. Structures are deposited with the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3EEL (CgDHFR:NADPH:2), 3EEK (CgDHFR:NADPH:3), 3EEJ (CgDHFR:NADPH:4) and 3EEM (CgDHFR:NADPH:6).

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for CgDHFR crystal structures

| Dataset | CgDHFR:(4) | CgDHFR: (6) | CgDHFR: (2) | CgDHFR: (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| PDB Accession Code | 3EEJ | 3EEM | 3EEL | 3EEK |

| Beamline | NSLS-X29 | NSLS-X29 | NSLS-X29 | NSLS-X29 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 37.5-2.11 | 42.8 - 2.11 | 42.8 - 1.95 | 43.8 - 2.03 |

| Space group | P41 | P41 | P41 | P41 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a=b=42.83, c=231.0 |

a=b=42.82, c=231.5 |

a=b=42.87, c=231.5 |

a=b=42.75, c=230.5 |

| Unique reflections | 22,685 | 21,588 | 27,413 | 22,714 |

| Redundancy | 4.4 (4.3) | 4.4 (4.1) | 4.0 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.6) |

| Completeness shella) |

(last 99 % (98 %) | 95 % (93 %) | 96% (63 %) | 91% (53%) |

| Rsymb (%) | 5.5 (10.8) | 5.0 (25.7) | 8.7 (28.4) | 6.7 (29.1) |

| Average I/ σ(I) | 36.0 (13.8) | 7.5 (21.8) | 17.6 (2.0) | 10.9 (2.0) |

| Refinement | ||||

| R-factorc (last shell) | 0.16 (0.17) | 0.17 (0.18) | 0.17 (0.2) | 0.17 (0.24) |

| Rfree (last shell) | 0.23 (0.22) | 0.23 (0.26) | 0.24 (0.26) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| Number of atoms (protein/ligands/solvent) |

3,692/150/190 | 3,692/154/205 | 3688/154/262 | 3,692/152/137 |

| Rmsd bonds/angles | 0.02, 2.2 | 0.023, 2.4 | 0.019, 2.2 | 0.023, 2.3 |

| Ramachandran plot ( % most favored, additional allowed, disallowed) |

97.1, 2.2, 0.7 | 95.7, 3.6, 0.7 | 96.2, 2.7, 1.1 | 96.0, 3.4, 0.7 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 16.9 | 25.5 | 19.8 | 21.9 |

The highest resolution shells are 2.16-2.11 Å, 2.16 - 2.11 Å, 2.00-1.95 Å and 2.09-2.03 Å for the four datasets, respectively

Rsym = (|Ihkl-<I>)/(Ihkl) where Ihkl is the intensity of an individual reflection and <I> is the mean intensity of that reflection

R-factor = (|Fo-Fc|)/(Fo), where Fo and Fc are observed and calculated structure factors

Synthesis

General

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker instruments at 500 and 125 MHz, 400 and 100 MHz or 300 and 75 MHz respectively. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm and are referenced to residual CHCl3 solvent; 7.26 ppm and 77.0 ppm for 1H and 13C respectively. Melting points were recorded on Mel-Temp 3.0 apparatus and are uncorrected. High-resolution mass spectrometry was provided by the Notre Dame Mass Spectrometry Laboratory. IR data was obtained a Shimadzu 8400-s FTIR spectrometer. TLC analyses were performed on Whatman Partisil K6F Silica Gel 60 plates. All glassware was oven dried and allowed to cool under an argon atmosphere. Anhydrous dichlormethane, ether and tetrahydrofuran were used directly from Baker cycletainers. Anhydrous dioxane was purchased from Aldrich. Anhydrous dimethylformamide was purchased from Acros and degassed by purging with argon. Anhydrous triethylamine was purchased from Aldrich and degassed by purging with argon. All reagents were used directly from commercial sources unless otherwise stated. Boronic acids were purchased from Aldrich or Alfa Aesar. The Ohira-Bestmann reagent was synthesized according to literature procedures (13). Aldehyde 15 and 2,4-diamino-5-iodo-6-methylpyrimidine were previously described by our group (14). All compounds were prepared as racemic mixtures.

1-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)propanone (12)

To a mixture of Mg turnings (0.312 g, 13 mmol) in 13 mL of THF under argon was added a solution of bromoethane (0.9 mL, 12 mmol) in THF (8 mL) via an addition funnel, dropwise. After stirring at ambient temperature for 30 min the Grignard reagent was added via cannula to a 0 °C solution of 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde 11 (1.96 g, 10 mmol) in THF (12 mL) dropwise. Following 10 minutes the reaction was quenched by the addition of water and saturated NH4Cl (10 mL each). The mixture was diluted with ether (20 mL) and the organic phase separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 20 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with brine (40 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to give the crude alcohol as a thick oil that was used immediately in the next step: TLC Rf = 0.08 (15% EtOAc/hexanes).

To a −78 °C solution of oxalyl chloride (1.40 g, 11 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added a solution of DMSO (1.56 mL, 22 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (8 mL) from an addition funnel, dropwise. The solution was stirred a further 10 min then a solution of the crude alcohol in CH2Cl2 (8 mL) was added through the same addition funnel over a period of ~10 min. Following 50 min, triethylamine (7 mL, 50 mmol) was added through the addition funnel and the mixture warmed to ambient temperature and stirred for 2 h. Water and saturated NaHCO3 (20 mL each) were added to quench the reaction and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 20 mL) and the combined extracts were dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated. The crude oil was purified by flash chromatography (40 g SiO2, 15% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide ketone 12 as a white solid (1.81 g, 81%): TLC Rf = 0.15 (10% EtOAc/hexanes); mp 50 – 52 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.13 (s, 2H), 3.83 (s, 6H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 2.88 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.12 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 199.2, 152.8, 142.1, 132.0, 105.2, 60.6, 56.0, 31.3, 8.1; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3001, 2831, 1674, 1411, 1126, 1007; HRMS (FAB, MH+) m/z 225.1107 (calculated for C12H17O4, 225.1127).

2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)butanal (13a)

To a 0 °C suspension of methoxymethyl triphenylphosphonium chloride (1.29 g, 3.77 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added NaOtBu (0.33 g, 3.46 mmol) in one portion. The red/orange suspension was stirred for a further 30 min at 0 °C then ketone 12 (0.602 g, 2.68 mmol) was added as a solution in THF (3 mL). Following 1 h, the reaction was quenched with water (15 mL) and diluted with ether (10 mL) and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with additional ether (2 × 10 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was filtered through a column of silica (SiO2 23 g, 5 – 15% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the crude enol ether (.596 g) that was immediately hydrolyzed in the subsequent step: TLC Rf = 0.42 (15% EtOAc/hexanes).

To a solution of crude enol ether in THF (10 mL) was added concentrated HCl (0.8 mL). The solution was heated to reflux and monitored by TLC until the starting material had been consumed (~1 h). The reaction was cooled, diluted with water (10 mL) and the THF removed at the rotovap. The aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 15 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with brine (2 × 15 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (12 g SiO2, 10% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide product aldehyde as a clear oil (0.527 g, 94%): TLC Rf = 0.17 (10% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.65 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.33 (m, 1H), 2.09 (m, 1H), 1.74 (m, 1H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.6 153.7, 137.4, 131.8, 105.7, 61.1, 60.8, 56.2, 22.8, 11.8; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 2964, 1722, 1589, 1130, 1009; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 238.1225 (calculated for C13H19O4, 238.1205).

3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pentyne (13)

To a 0 °C solution of previously synthesized aldehyde (0.477 g, 2.0 mmol) in MeOH (9 mL) was added the Ohira-Bestmann reagent (0.556 g, 3.0 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (1 mL) followed by powdered, anhydrous K2CO3 (0.58 g, 4.0 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the starting material had been consumed by TLC (1.5 h). The reaction was diluted with water (20 mL) and the methanol removed at the rotovap. The aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 20 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with brine (20 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 5 – 15% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford alkyne 13 as a colorless oil (0.342 g, 73%): TLC Rf = 0.46 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.56 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.48 (m, 1H), 2.27 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.76 (m, 2H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.0, 137.0, 136.7, 104.3, 85.6, 71.1, 60.6, 55.9, 39.3, 31.2, 11.6; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3286, 2964, 1591, 1238, 1128, 1008; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 234.1280 (calculated for C14H18O3, 234.1256).

2,4-diamino-5-[3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pent-1-ynyl]-6-methylpyrimidine (14)

To an oven dried 8 mL screw cap vial was added 2,4-diamino-5-iodo-6-methylpyrimidine (0.111 g, 0.444 mmol), CuI (0.009 g, 0.047 mmol, ~10%), and Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (22 mg, 0.031 mmol, ~7% Pd). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous DMF (0.75 mL) was added followed by alkyne 13 (0.156 g, 0.666 mmol) as a solution in DMF (0.5 mL). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous triethylamine was added (1.25 mL) and the mixture was degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. The vial was sealed under argon and heated at 50 °C for 3 h. After cooling and stirring overnight, the orange solution was diluted with EtOAc (20 mL) and washed twice with a water/sat NaHCO3 solution (1:2, 20 mL) and brine (20 mL). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 9 g, 2% MeOH/CHCl3) to afford coupled pyrimidine 14 as a tan solid (0.149 g, 94%): an analytical sample was generated by triturating under ether/DCM; TLC Rf = 0.36 (10% MeOH/CHCl3); mp dec. >175 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.62 (s, 2H), 5.18 (bs, 2H), 4.95 (bs, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.78 (dd, J = 8.0, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.86 (m, 2H), 1.07 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.4, 164.2, 160.4, 153.2, 137.8, 136.8, 104.4, 100.7 91.5, 76.6, 60.8, 56.1, 40.8, 31.8, 22.9, 12.1; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 357.1913 (calculated for C19H25N4O3, 357.1927).

2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2-methylpropanal (16)

A solution of aldehyde 15 (1.03 g, 4.59 mmol), cyclohexylamine (0.57 mL, 4.99 mmol) and dry benzene (15 mL) was heated at reflux under a Dean-Stark trap for 6 h then cooled and allowed to stir overnight. The following day the solution was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered and evaporated to provide the crude cyclohexylimine that showed now evidence of aldehyde by 1H NMR. This material was used in the next step without further purification.

A solution of LDA was prepared by adding n-butyllithium (2.5 M in hexanes, 0.34 mL, 0.85 mmol) dropwise to a solution of diisopropylamine (0.12 mL, 0.85 mmol) in dry THF (1 mL) at −8 °C (ice-salt bath). This solution stirred for a further 20 minutes then was cooled to −78 °C. To the cooled LDA solution was added a solution of crude cyclohexylimine (0.226 g, ~0.74 mmol) in THF (1 mL). The yellow solution was stirred 20 min at −78 °C then warmed to 0 °C (15 min) and back to −78 °C. Following an additional 15 min, methyliodide (0.07 mL, 1.12 mmol) was added and the reaction stirred for 2 h. The reaction was quenched by the addition of aq. HCl (1 N, 2 mL) and the mixture was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stir 1 h. The mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate (15 mL) and the aqueous phase was separated. The organic phase was washed sequentially with saturated sodium bicarbonate, water and brine (10 mL each) and dried over sodium sulfate. The solution was concentrated to provide the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (8 g SiO2, 5 – 10% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide aldehyde 16 as a clear oil (0.092 g, 52%): TLC Rf = 0.33 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.43 (s, 1H), 6.43 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.7, 153.4, 137.3, 136.6, 104.0, 60.7, 56.2, 50.4, 22.4; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 2970, 2704, 1728, 1587, 1126, 1007; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 238.1203 (calculated for C13H18O4, 238.1205).

3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-3-methylbutyne (17)

To a 0 °C solution of aldehyde 16 (0.160 g, 0.67mmol) in MeOH (3 mL) was added the Ohira-Bestmann reagent (0.201 g, 1.04 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (0.5 mL) followed by powdered, anhydrous K2CO3 (0.187 g, 1.38 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the starting material had been consumed by TLC (0.5 h). The reaction was diluted with water (8 mL) and the methanol removed at the rotovap. The aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 10 mL) and the combined extracts were washed with brine (10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 10 g, 5% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford alkyne 17 as a colorless oil (0.131 g, 83%): TLC Rf = 0.47 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.77 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 1H), 1.58 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.7, 141.9, 136.5, 102.9, 90.8, 69.8, 60.7, 56.0, 35.9, 31.5; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3284, 2974, 2835, 1589, 1413, 1124, 1009; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 234.1270 (calculated for C14H18O3, 234.1256).

2,4-diamino-5-[3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-3-methylbut-1-ynyl]-6-methylpyrimidine (18)

To an oven dried 8 mL screw cap vial was added 2,4-diamino-5-iodo-6-methylpyrimidine (0.093 g, 0.372 mmol), CuI (10 mg, 0.052 mmol, ~14%), and Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (21 mg, 0.030 mmol, ~8% Pd). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous DMF (0.5 mL) was added followed by alkyne 17 (0.131 g, 0.56 mmol) as a solution in DMF (0.5 mL). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous triethylamine was added (1 mL) and the mixture was degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. The vial was sealed under argon and heated at 50 °C for 3 h. After cooling, the orange solution was diluted with EtOAc (25 mL) and washed twice with a water/sat NaHCO3 solution (1:2, 20 mL) and brine (20 mL). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 8 g, 2% MeOH/CHCl3) to afford coupled pyrimidine 18 as a pale solid (0.130 g, 98%): An analytical sample was prepared by triturating under ether/DCM; TLC Rf = 0.49 (10% MeOH/CHCl3); mp 175 – 177 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.82 (s, 2H), 5.13 (bs, 2H), 4.89 (bs, 2H), 3.87 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.3, 164.1, 160.5, 153.0, 142.6, 136.7, 105.8, 102.9, 91.4, 75.2, 60.8, 56.2, 37.3, 32.0, 22.8; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 356.1865 (calculated for C19H24N4O3, 356.1848).

1-(3-methoxy-5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)phenyl)ethanone (20)

To a 15 mL screw cap pressure vessel was added ketone 19 (0.320 g, 1.40 mmol), 4-tert-butylphenylboronic acid (0.498 g, 2.80 mmol), cesium carbonate (1.37 g, 4.20 mmol), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (0.049 g, 0.07 mmol, 5% Pd) and anhydrous dioxane (3.5 mL). The mixture was stirred and then degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. Once the mixture warmed to r.t. the vessel was sealed under argon and placed in an 80 °C oil bath for 18 h. The dark colored mixture was cooled, diluted with ether (8 mL) and filtered through a pad of silica gel (~15 g) rinsing with ether. The filtrate was concentrated and the residue purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 2 – 5% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford biphenyl ketone 20 as a viscous oil (0.369 g, 94%). This material contained an unidentified impurity that could not be removed even after repeated chromatography. The impurity did not effect the subsequent reaction: TLC Rf = 0.44 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (m, 1H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.46 (m, 1H), 7.34 (m, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 2.65 (s, 3H), 1.38 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.0, 160.1, 151.0, 142.9, 138.8, 137.2, 126.8, 125.8, 120.4, 118.1, 110.9, 55.5, 34.6, 31.3, 26.8; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 2962, 1682, 1591, 1360, 1211, 1043, 910; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 282.1603 (calculated for C19H22O2, 282.1620).

1-(3-methoxy-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)phenyl)ethanone (21)

To a 15 mL screw cap pressure vessel was added ketone 19 (0.371 g, 1.62 mmol), 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid (0.493 g, 3.24 mmol), cesium carbonate (1.58 g, 4.85 mmol), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (0.056 g, 0.08 mmol, 5% Pd) and anhydrous dioxane (3.5 mL). The mixture was stirred and then degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. Once the mixture warmed to r.t. the vessel was sealed under argon and placed in an 80 °C oil bath for 2 h. The dark colored mixture was cooled, diluted with ether (8 mL) and filtered through a pad of silica gel (~15 g) rinsing with ether. The filtrate was concentrated and the residue purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 15% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford biphenyl ketone 21 as a viscous oil (0.405 g, 97%). This material contained an unidentified impurity that could not be removed even after repeated chromatography. The impurity did not effect the subsequent reaction: TLC Rf = 0.22 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.71 (m, 1H), 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.42 (dd, J = 2.5, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (dd, J = 2.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (m, 2H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.63 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.0, 160.1, 159.6, 142.6, 138.8, 132.5, 128.2, 119.6, 117.7, 114.3, 110.6, 55.5, 55.3, 26.8; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3001, 2935, 1682, 1516, 1249, 1032, 734; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 256.1083 (calculated for C16H16O3, 256.1099).

2-(3-methoxy-5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)phenyl)propanal (22a)

To a 0 °C suspension of methoxymethyltriphenylphosphonium chloride (0.784 g, 2.29 mmol) in dry THF (8 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added NaOtBu (0.285 g, 2.97 mmol) in one portion. The red/orange suspension was stirred for a further 0.5 h at 0 °C then a solution of biphenyl ketone 20 (0.369 g, 1.31 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was added dropwise. Following 62 h (stirred over a weekend), the reaction was quenched with water (15 mL) and diluted with ether (30 mL). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase extracted with additional ether (2 × 10 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was filtered through a column of silica (SiO2 23 g, 1% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the enol ether that was immediately hydrolyzed in the subsequent step: TLC Rf = 0.68 (15% EtOAc/hexanes).

To a solution of enol ether in THF (12 mL) was added concentrated HCl (0.4 mL). The solution was warmed in an oil bath to between 55 and 65 °C and monitored by TLC. Once the starting material had been consumed (~1 h) the reaction was cooled and diluted with water and ether (30 mL each). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase extracted with additional ether (2 × 15 mL). The combined extracts were washed sequentially with saturated NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 5% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the intermediate aldehyde as a colorless oil (0.290 g, 75% from 20): TLC Rf = 0.42 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.75 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.10 (dd, J = 2.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (m, 1H), 6.76 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.69 (dq, J = 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 1.51 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.40 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.7, 160.4, 150.7, 143.3, 139.5, 137.8, 126.8, 125.7, 119.5, 112.6, 111.6, 55.3, 53.1, 34.5, 31.3, 14.5; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 2964, 2716, 1723, 1593, 1456, 1339, 1215, 1032, 831; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 296.1801 (calculated for C20H24O2, 296.1776).

3-(3-methoxy-5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)phenyl)butyne (22)

To a 0 °C solution of previously synthesized aldehyde (0.290 g, 0.98 mmol) in MeOH (3.5 mL) was added the Ohira-Bestmann reagent (0.284 g, 1.48 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (1 mL) followed by powdered, anhydrous K2CO3 (0.270 g, 1.96 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the starting material had been consumed by TLC (~1.5 h). The reaction was diluted with water (40 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 25 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (40 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 5% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford alkyne 22 as a colorless oil (0.223 g, 78%): TLC Rf = 0.47 (5% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59 (m, 2H), 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.25 (m, 1H), 7.05 (m, 1H), 6.99 (m, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.85 (dq, J = 7.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.60 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.41 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.1, 150.4, 144.5, 142.8, 138.2, 126.9, 125.6, 118.3, 111.3, 111.0, 86.9, 70.3, 55.3, 34.5, 31.8, 31.3, 24.2; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3292, 2962, 1595, 1458, 1337, 1213, 831; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 292.1823 (calculated for C21H24O, 292.1827).

2-(3-methoxy-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)phenyl)propanal

To a 0 °C suspension of methoxymethyltriphenylphosphonium chloride (0.940 g, 2.74 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added NaOtBu (0.334 g, 3.47 mmol) in one portion. The red/orange suspension was stirred for a further 0.5 h at 0 °C then a solution of biphenyl ketone 21 (0.398 g, 1.55 mmol) in THF (4 mL) was added dropwise. Following 62 h (stirred over a weekend), the reaction was quenched with water (15 mL) and diluted with ether (30 mL). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase extracted with additional ether (2 × 10 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was filtered through a column of silica (SiO2 24 g, 10% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the crude enol ether that was immediately hydrolyzed in the subsequent step: TLC Rf = 0.49 (15% EtOAc/hexanes).

To a solution of the crude enol ether in THF (16 mL) was added concentrated HCl (0.5 mL). The solution was warmed in an oil bath to between 55 and 65 °C and monitored by TLC. Once the starting material had been consumed (~1.5 h) the reaction was cooled and diluted with water and ether (30 mL each). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase extracted with additional ether (2 × 15 mL). The combined extracts were washed sequentially with saturated NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 15% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the intermediate aldehyde as a colorless oil (0.326 g, 78% from 21): TLC Rf = 0.21 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.72 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.02 (m, 1H), 7.0 - 6.95 (m, 3H), 6.69 (m, 1H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.66 (dq, J = 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 1.48 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.7, 160.4, 159.3, 142.9, 139.4, 133.0, 128.1, 119.1, 114.1, 112.1, 111.3, 55.2, 55.1, 53.0, 14.4; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 2974, 2718, 1724, 1516, 1250, 1034, 829; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 270.1270 (calculated for C17H18O3, 270.1256).

3-(3-methoxy-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)phenyl)butyne (23)

To a 0 °C solution of previously synthesized aldehyde (0.321 g, 1.19 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was added the Ohira-Bestmann reagent (0.344 g, 1.79 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (1 mL) followed by powdered, anhydrous K2CO3 (0.329 g, 2.38 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the starting material had been consumed by TLC (~1.5 h). The reaction was diluted with water (40 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with ether (3 × 25 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (40 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 5% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford alkyne 23 as a colorless oil (0.187 g, 59%): TLC Rf = 0.45 (15% EtOAc/hexanes); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.22 (m, 1H), 7.04 - 6.99 (m, 3H), 6.97 (m, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.84 (dq, J = 7.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.60 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.1, 159.2, 144.5, 142.4, 133.5, 128.2, 117.9, 114.1, 110.8, 110.7, 86.9, 70.3, 55.2 (2C’s), 31.7, 24.2; IR (neat, KBr, cm−1) 3288, 2974, 2835, 1608, 1516, 1250, 1034, 829; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 266.1310 (calculated for C18H18O2, 266.1307).

2,4-diamino-5-[3-(3-methoxy-5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)phenyl)but-1-ynyl]-6-methylpyrimidine (24)

To an oven dried 15 mL pressure vessel was added 2,4-diamino-5-iodo-6-methylpyrimidine (0.128 g, 0.512 mmol), CuI (10 mg, 0.053 mmol, ~10%), and Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (26 mg, 0.037 mmol, ~7% Pd). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous DMF (1.0 mL) was added followed by alkyne 22 (0.223 g, 0.762 mmol) as a solution in DMF (0.5 mL). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous triethylamine was added (1.5 mL) and the mixture was degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. The vial was sealed under argon and heated at 50 °C for 3 h. After cooling, the orange solution was diluted with EtOAc (30 mL) and washed twice with a water/sat NaHCO3 solution (1:2, 20 mL) and brine (20 mL). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 23 g, 2% MeOH/CHCl3) to afford coupled pyrimidine 24 as a pale solid (0.120 g, 57%): An analytical sample was generated by crystallizing from hexanes/ether. TLC Rf = 0.22 (EtOAc); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 2.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (m, 1H), 5.13 (bs, 2H), 4.83 (bs, 2H), 4.07 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 2.40 (s, 3H), 1.62 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.36 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.4, 164.2, 160.5, 160.2, 150.6, 145.2, 142.9, 138.1, 126.8, 125.7, 118.2, 111.2, 110.9, 101.7, 91.3, 75.7, 55.3, 34.5, 33.1, 31.3, 24.7, 22.8; HRMS (FAB, M+) m/z 414.2424 (calculated for C26H30N4O, 414.2420).

2,4-diamino-5-[3-(3-methoxy-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)phenyl)but-1-ynyl]-6-methylpyrimidine (25)

To an oven dried 15 mL pressure vessel was added 2,4-diamino-5-iodo-6-methylpyrimidine (0.117 g, 0.468 mmol), CuI (9 mg, 0.047 mmol, ~10%), and Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (23 mg, 0.033 mmol, ~7% Pd). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous DMF (1.0 mL) was added followed by alkyne 23 (0.187 g, 0.702 mmol) as a solution in DMF (0.5 mL). Degassed (argon purge) anhydrous triethylamine was added (1.5 mL) and the mixture was degassed once using the freeze/pump/thaw method. The vial was sealed under argon and heated at 50 °C for 3 h. After cooling, the orange solution was diluted with EtOAc (30 mL) and washed twice with a water/sat NaHCO3 solution (1:2, 20 mL) and brine (20 mL). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford the crude product that was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 20 g, 2% MeOH/CHCl3) to afford coupled pyrimidine 25 as a pale solid (0.118 g, 65%): An analytical sample was generated by triturating under ether/DCM; TLC Rf = 0.19 (EtOAc); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.20 (m, 1H), 6.99 - 6.95 (m, 3H), 6.94 (m, 1H), 5.16 (bs, 2H), 4.90 (bs, 2H), 4.06 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.62 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.5, 164.1, 160.4, 160.2, 159.3, 145.3, 142.6, 133.5, 128.2, 117.9, 114.2, 110.9, 110.7, 101.8, 91.4, 75.6, 55.3 (2, -OCH3), 33.2, 24.7, 22.8; HRMS (FAB, MH+) m/z 389.1970 (calculated for C23H24N4O2, 389.1978).

Results and Discussion

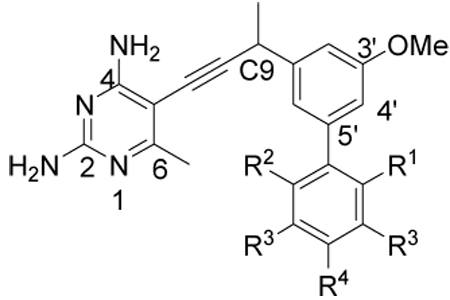

A “methyl scan” around the distal biphenyl ring

Our prior work (8) had shown that the inclusion of a second substituted aromatic ring, relative to compound 1, led to a substantial increase in enzyme inhibition as well as antifungal activity. However, the very limited information available from just two compounds did not allow us to make any generalizations about the structure-activity relationships in regards to this second aromatic moiety. Fortunately, we had three additional related inhibitors (compounds 4–6) (15) that collectively completed a scan of methyl substitutions around the distal phenyl ring. The clear pattern that emerged (Table 1) showed that the presence and placement of methyl substitutions on the distal phenyl ring was critical to achieving the subnanomolar potencies observed with inhibitors 2 and 3. For example, the unsubstituted biphenyl derivative 4 exhibited no increase in potency relative to the simple monophenyl, compound 1 (IC50 = 8.2 nM (8)). The alternate placement of methyl groups at the ortho-and ortho’-positions (compounds 5 and 6) likewise failed to improve activity. In summary, the strict requirements correlating an increase in potency with substitution at the meta- and para-positions suggest that the increase is specific and not simply a generic hydrophobic effect. Gaining a detailed understanding of the structural basis of the potency could prove valuable in the design of future generations of inhibitors.

Table 1.

Enzyme inhibition and antifungal activity of biphenyl antifolates

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounda | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | IC50 (nM) (Cgb) |

IC50 (nM) (hb) |

Selectivityc | MIC (µg/mL) (Cg) |

IC50 (µM) (human MCF- 10) |

| 2 | H | H | CH3 | H | 0.55 | 750 | 1400 | 3 | 47 |

| 3 | H | H | H | CH3 | 0.61 | 1400 | 2300 | 1.5 | 54 |

| 4 | H | H | H | H | 7.3 | 1700 | 230 | 11.1 | 90 |

| 5 | CH3 | H | H | H | 7.3 | 1400 | 190 | 23 | 91 |

| 6 | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 5.5 | 1300 | 240 | 24 | 88 |

| 24 | H | H | H | tBu | 10 | 210 | 21 | 207 | 50 |

| 25 | H | H | H | OMe | 6.4 | 180 | 28 | 3.1 | 102 |

All compounds were evaluated as racemic mixtures

Cg: Candida glabrata; h: human

Selectivity is reported as IC50 (h)/IC50 (Cg)

Four crystal structures of CgDHFR bound to biphenyl antifolates

In order to elucidate the structural basis of the potency of the biphenyl ligands, we determined four crystal structures of CgDHFR bound to NADPH and four different biphenyl ligands: compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6. All four compounds have a 6-methyl substituted 2,4-diaminopyrimidine ring, a methyl-substitution at the propargylic position and a 3’-methoxy on the proximal phenyl ring (key atom positions are labeled in a representative compound in Table 1). All of the crystals belong to the tetragonal space group, P41 and have unit cell dimensions similar to the first crystal structure determined with compound 1. The structures were determined using difference Fourier methods and refined to Rfree values ranging from 0.23–0.24 and overall R-factors ranging from 0.16–0.17. The data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 2.

The structures of the four CgDHFR complexes contain two molecules in the asymmetric unit and each molecule includes 225 amino acid residues. The histidine affinity tags form a critical crystal packing interface and display ordered electron density. Similar to the structure of CgDHFR bound to compound 1, the N-terminal methionine and serine residues have poor electron density and were not modeled. Superposition of the two molecules in the asymmetric units of the four structures results in an rms deviation of 0.1 Å, providing evidence that the two molecules in the asymmetric unit are almost identical.

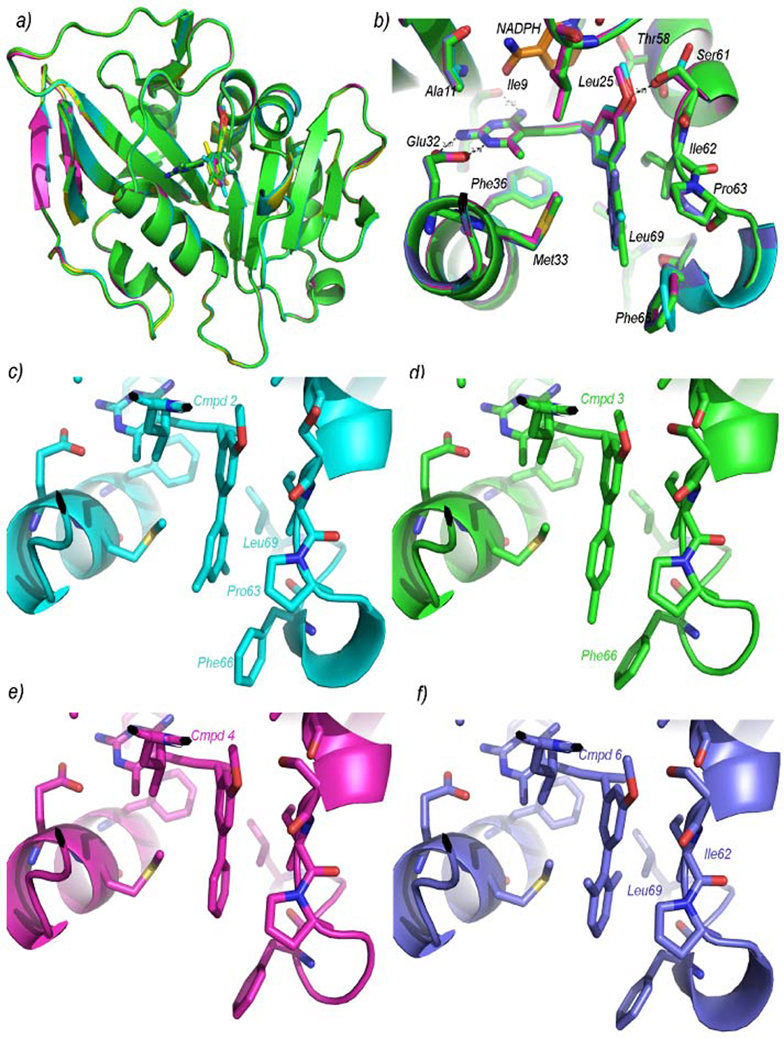

The four complexes possess the same overall fold of CgDHFR with a central β-sheet that includes ten β-strands and six α-helices packed against the core (Fig. 1a). A superposition of the four structures shows several conserved features (Fig. 1b). The 2,4-diaminopyrimidine ring forms hydrogen bonds between Glu 32 and the protonated N1 and 2-amino group, a hydrogen bond between the backbone carbonyl of Ile 9 and the 4-amino group and van der Waals interactions with Phe 36, Val 10 and Ala 11. The 6-methyl group is in van der Waals contact with residues Met 33 and Leu 25. The propargyl linker forms van der Waals interactions with the nicotinamide ring of NADPH and limited interactions with Phe 36. The propargyl methyl group has van der Waals interactions with the side chains of Thr 58, Ile 62 and Ile 121 in each of the four complexes. The proximal phenyl ring forms van der Waals interactions with Ile 62 and Met 33. The 3-methoxy group on this phenyl ring forms an additional hydrogen bond with Ser 61 in the complexes with compounds 4 and 3 (2.6 and 2.5 Å, respectively) but in complexes with compounds 2 and 6, Ser 61 may be too close (2.2–2.3 Å) to form a hydrogen bond. The Fo-Fc difference map shows two conformations for Ser 61: in one, the hydroxyl group points toward the ligand and in the other, it points away from the ligand and forms a hydrogen bond with a water molecule. In general, the distal phenyl ring fits nicely in a binding cleft comprised of Ile 62, Pro 63, Phe 66, Leu 69 and Met 33. The torsion angle between the two phenyl rings is predicted to adopt a low energy value of approximately 90 °. Interestingly, in all four structures, this angle ranges from 29.6 ° (unsubstituted compound 4) to 37.3 ° in the ortho-substituted compound 6.

Figure 1.

Four crystal structures of CgDHFR bound to compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6. a) an overview of the enzyme: superposition of all four structures b) superposition at the active site with NADPH (orange) and compound 2 (cyan), compound 3 (green), compound 4 (magenta) and compound 6 (purple), c) a closer view of the distal phenyl ring in the complex with compound 2, d) the distal phenyl ring in the complex with compound 3, e) the distal phenyl ring in the complex with compound 4 and f) the distal phenyl ring in complex with compound 6. For panels c–f, the coloring scheme is the same as in b and only residues with predicted interactions are labeled.

There are also several critical differences between the structures that may explain the differences in affinity between the compounds. Obviously, the majority of the differences are in the vicinity of the distal phenyl ring (Fig. 1c–f). The methyl substitutions on the high affinity compounds, 2 and 3, have additional positive interactions relative to the unsubstituted compound 4 and in contrast to the negative interactions of the methyl groups on compound 6. One of the meta-methyl groups on 2 forms van der Waals interactions with Phe 66 and Leu 69, the other with Pro 63 (Fig. 1c). The phenyl ring of Phe 66 rotates approximately 45 °, relative to the structures with compounds 2, 4 and 6, placing each carbon atom in an optimal location for increased hydrophobic interactions with the meta-methyl groups. The para-methyl group on compound 3 forms van der Waals interactions with Phe 66 (Fig. 1d). In contrast, the lower affinity unsubstituted compound 4 has few interactions (Fig. 1e). Also, the structure with the lower affinity ortho-ortho’-methyl compound 6, shows that one methyl group may be in weak van der Waals contact with Ile 62, but it may also have a repulsive interaction with Leu 69 (Fig. 1f). The second ortho-methyl group does not appear to interact with the enzyme.

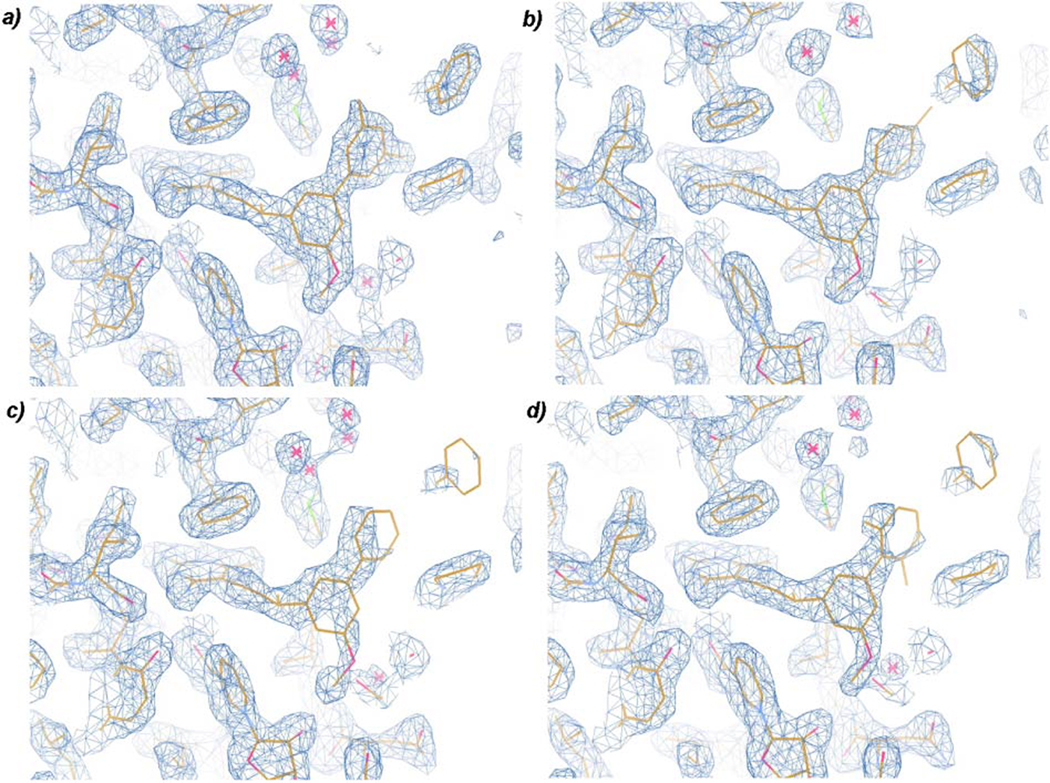

In addition to these different interactions at the distal phenyl ring, there are differences in the B-factors of the rings. Electron density for the high affinity ligands was well-defined even at early stages of refinement but was poorly defined for the weaker compounds until later stages of refinement (Fig. 2). The average B-factors of the pyrimidine rings of the four compounds are comparable but the B-factors of the distal phenyl rings are significantly higher for the lower affinity compounds (Table 3), indicating that the distal phenyl rings of compounds 4 and 6 binds more flexibly and may adopt multiple conformations in the active site.

Figure 2.

Electron density (2Fo-Fc, contoured at 1.3 sigma) for CgDHFR:inhibitor complexes. a) compound 2, b) compound 3, c) compound 4, d) compound 6.

Table 3.

Comparison of the interaction of compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6 with CgDHFR

| CgDHFR:2 | CgDHFR:3 | CgDHFR:4 | CgDHFR:6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) | 0.55 | 0.6 | 7.3 | 5.5 |

| Interactions of the methyl substituents |

Pro 63, Phe 66, Leu 69 |

Phe 66 | None | Ile 62 Negative: Leu 69 |

| B-factor (Å2) of distal phenyl ring |

17.8 | 28.9 | 31.9 | 38.9 |

| B-factor (Å2) of pyrimidine ring |

12.4 | 14.1 | 9.0 | 17.7 |

| Difference of B-factors (Å2) |

15.4 | 14.8 | 22.9 | 21.2 |

Selectivity over the human enzyme

The IC50 values of compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6 against human DHFR are very similar: 0.75 µM, 1.4 µM, 1.7 µM and 1.3 µM, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, the high degree of selectivity of compounds 2 and 3 (Table 1) over the human enzyme results primarily from enhanced potency against CgDHFR. However, other differences between the fungal and mammalian enzymes may also play a role. For instance, Met 33 in CgDHFR is a Phe in hDHFR and as such, is not predicted to form the same interactions with the distal phenyl ring. Also, residues 59–64 in hDHFR are 1.2 Å closer to the active site than in CgDHFR (residues 61–66), possibly restricting the space for the distal phenyl ring. Finally, the para-methyl group of compound 3, which interacts favorably with Phe 66 in CgDHFR, is not predicted to have favorable interactions with Asn 64 in hDHFR.

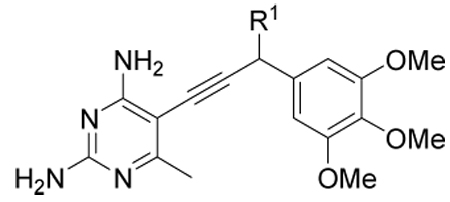

Probing the propargyl position

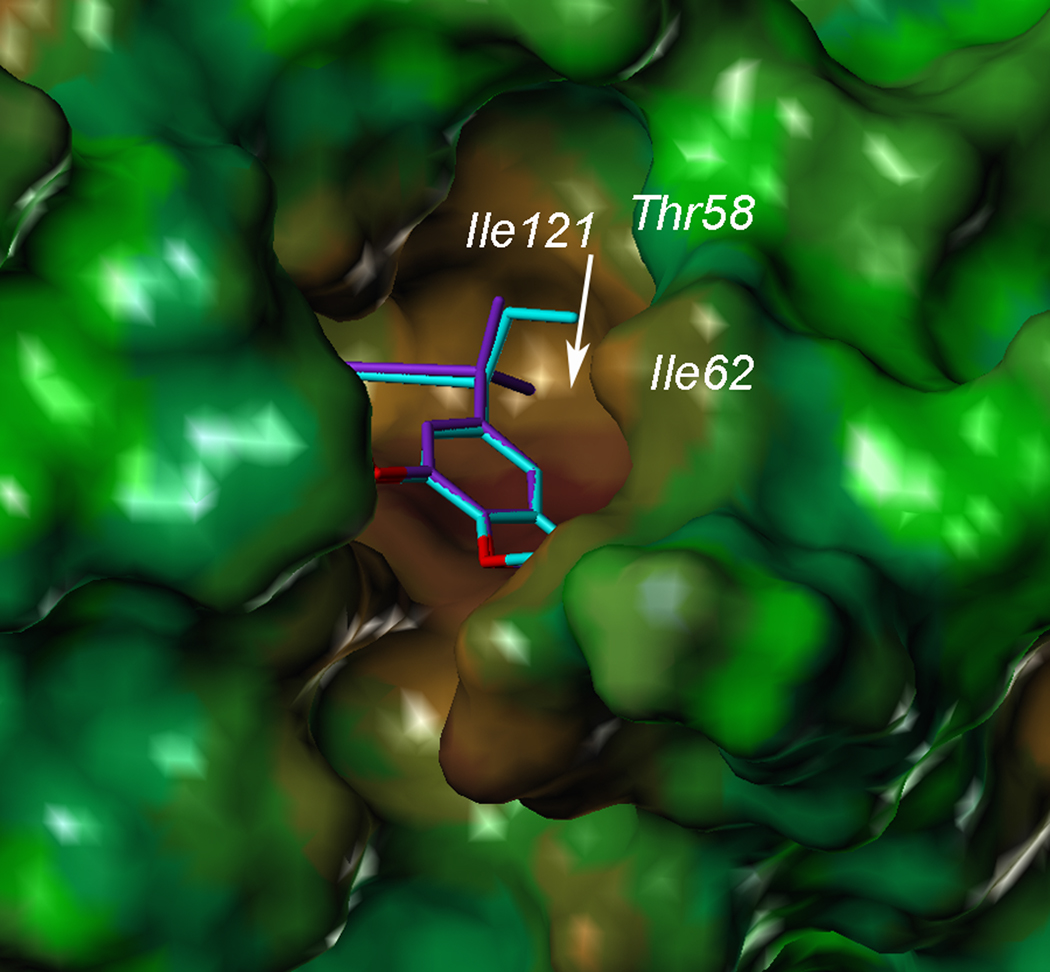

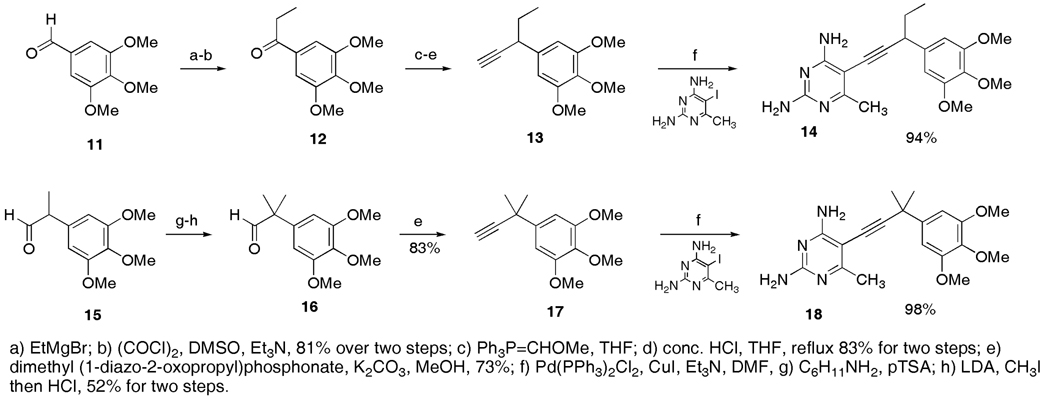

One feature that arose from analysis of the crystal structures of CgDHFR is that there is a hydrophobic pocket lined with residues Ile 121, Thr 58 and Ile 62 adjacent to the propargyl position (C9) of the antifolates (Fig. 3). Despite the fact that the protein was incubated with the racemic compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6, the single R-enantiomer appeared to be bound in the active site in the crystal structures. All compounds previously examined maintained a simple methyl group at the propargyl position. In order to begin to probe which functionality most complements this pocket, we examined the structure-activity relationships of several antifolates with the simpler trimethoxyphenyl scaffold. Four previously disclosed compounds (7–10) with hydrogen, methyl, hydroxyl and methoxy substitutions at the propargyl position, respectively(8, 14) were evaluated for their enzyme and fungal growth inhibition. In addition, we designed two novel derivatives, ethyl (14) and gem-dimethyl (18) homologs (Scheme 2) based on evaluation of the crystal structures. While the C9 methyl group makes favorable interactions, an extension at this position, C9-ethyl, could potentially contact Ile 121 and Ile 62 (Fig. 3). Although only the R-configuration at C9 appeared in the bound structures, it seemed that replacement of the S-hydrogen with a methyl group could potentially generate additional favorable contacts with Ile 121 and Thr 58 as well as NADPH. The resulting gem-dimethyl analog (18) was also attractive as this substitution results in a loss of stereogenicity at C9 and thus simplifies the synthesis.

Figure 3.

Surface of CgDHFR with docked models of compounds 14 (cyan) and 18 (purple), illustrating the pocket near the propargylic linker.

Scheme 2.

Trimethoxy benzaldehyde 11 was converted to the corresponding ethyl ketone 12. The ketone was homologated to the terminal alkyne 13 by sequential Wittig homologation followed by Ohira-Bestmann reaction on the intermediate aldehyde. Final conversion to a propargyl ethyl analog 14 was accomplished in good yield through a final Sonogashira coupling. The gem-dimethyl analog 18 was prepared from the key acetylene 17, which was in turn synthesized from the previously reported aryl acetaldehyde 15 by alkylation of the derived metalloenamine followed by Ohira-Bestmann homologation.

For this series of compounds, the level of enzyme inhibition did not vary substantially, however, the antifungal activity proved to be very sensitive to the same substitutions (Table 4). For example, oxygenated analogs 9 and 10 appeared to be good inhibitors of the enzyme but showed no antimicrobial activity. This lack of activity may relate to poor cell penetration because of the increased polarity of the molecules. Both the dimethyl (18) and ethyl (14) analogs showed diminished antifungal activity despite good enzyme inhibition. This result was surprising since both compounds would not be expected to have substantially different physicochemical properties from compound 8.

Table 4.

Enzyme inhibition and antifungal activity of propargyl-substituted antifolates

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | IC50 (nM) (Cg) |

IC50 (nM) (h) |

Selectivity | MIC (µg/mL) (Cg) |

IC50 (µM) (human) |

| 7 | H | 17 | 400 | 24 | 20 | 250 |

| 8 | Me | 25 | 1380 | 55 | 21 | 125 |

| 9 | OH | 39 | 5710 | 146 | Inact | Inact |

| 10 | OMe | 30 | 1220 | 41 | Inact | 490 |

| 14 |

gem- diMe |

11 | 290 | 26 | 89 | 185 |

| 18 | Et | 27 | 200 | 7 | 178 | 175 |

Probing the para-phenyl position

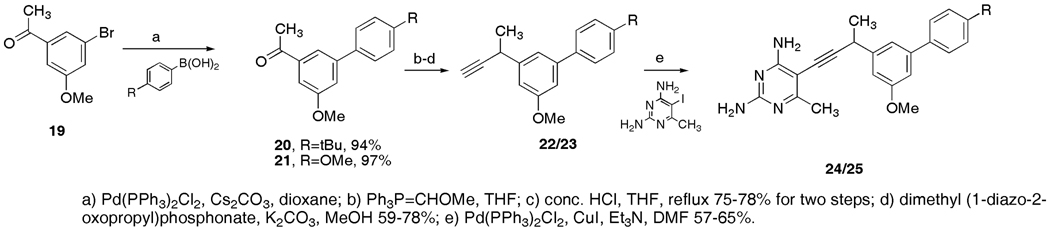

The structure of CgDHFR bound to compound 3 suggested that greater steric bulk at the para-position of the distal phenyl ring could be accommodated and lead to increased interactions with Phe 66. We therefore prepared two new inhibitors with p-tBu (24) and p-OMe (25) substitutions to examine this pocket in greater detail (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Cross-coupling of the previously described aryl bromide 19 with either p-t-butyl or p-methoxy phenyl boronic acid gave the aryl acetophenones 20 and 21 in very good yield. Homologation to the alkyne and a final palladium-mediated coupling produced the new inhibitors 24 and 25.

Interestingly, while both compounds 24 and 25 showed diminished enzyme inhibition relative to compound 3 (p-Me), they exhibited divergent trends with respect to antifungal activity. On evaluation, compound 24 showed lower levels of antifungal activity than compound 3. In contrast, compounds 25 and 3 show equivalent antifungal activity. Furthermore, both 25 and 3 exhibit approximately 33-fold greater potency against C. glabrata compared to the human cell line. These results suggest that the para-position may be used to tune the activity against various cell lines.

Conclusions and Future Directions

A number of the propargyl-based antifolates are excellent inhibitors of the C. glabrata DHFR enzyme, exhibit good selectivity over the human form of the enzyme and inhibit the growth of the fungal strain. Specifically, substituted biphenyl compounds are particularly potent inhibitors. In order to determine the structural basis of the potency and selectivity of these compounds, four high resolution crystal structures were determined with compounds that collectively complete a methyl scan around the distal phenyl ring. These structures show that methyl groups at the para and meta positions yield the greatest number of interactions with CgDHFR as well as the greatest degree of selectivity. Two new inhibitors with t-butyl and methoxy groups at the para position were designed to further probe these favorable interactions. Synthesis and evaluation of these two inhibitors show that the inhibition of fungal growth is sensitive to substitution patterns at this position.

Substitutions at the propargylic position (C9) also interacted with a hydrophobic pocket. The methyl substitution on the biphenyl compounds assumed the R-configuration in the crystal structures and did not appear to fully use the space available in this pocket. Therefore, compounds with ethyl and gem-dimethyl were designed, synthesized and evaluated. While these compounds exhibited enzyme inhibition similar to the methyl-substituted compound of the same scaffold, their antifungal activity decreased 4.5–9 -fold, providing evidence that antifungal activity is sensitive to substitutions at this position as well.

In future experiments, we intend to explore the relationships between the propargyl and para-phenyl positions and antifungal activity. While increasing polarity may explain the lack of antifungal activity for some compounds, the effect of substitution patterns on antifungal activity is unexplained for other compounds, such as 14 and 18. Additional compounds with varying substitutions at these positions will be designed, synthesized and evaluated for enzyme inhibition and antifungal activity as well as monitored for cell permeability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Kathleen Frey in determining the enzyme inhibition values for human DHFR and funding from NIGMS GM067542.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information, including tabular HPLC purity data, HPLC traces and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compounds 13–24, 16–18 and 20–25 is available through the online edition.

References

- 1.Pfaller M, Diekema D. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4419–4431. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4419-4431.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin G, Mannino D, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfaller M, Diekema D. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, VandeBerg J, Hu J, Messer S, et al. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1172–1177. doi: 10.1086/378745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller M, Messer S, Hollis R, Jones R, Doern G, Brandt M, et al. Trends in species distribution and susceptibility to fluconazole among blood stream isolates of Candida species in the United States. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;33:217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trick W, Fridkin S, Edwards J, Hajjeh R, Gaynes R. Secular trend of hospital-acquired candidemia among intensive care unit patients in the United States during 1989–1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:627–630. doi: 10.1086/342300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett JE, Izumikawa K, Marr K. Mechanism of increased fluconazole resistance in Candida glabrata during prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1773–1777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1773-1777.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Bolstad D, Smith A, Priestley N, Wright D, Anderson A. Structure-guided development of efficacious antifungal agents targeting Candida glabrata dihydrofolate reductase. Chem Biol. 2008;15:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey K, Szekely A, Johnson E, Warnock D. Comparison of a new commercial colorimetric microdilution method with a standard method for in-vitro susceptibility testing of Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:439–444. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW, Sweet RM, editors. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pietruszka J, Witt a. Synthesis of the Bestmann-Ohira reagent. Synthesis. 2006:4266–4268. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelphrey P, Popov V, Joska T, Beierlein J, Bolstad E, Fillingham Y, et al. Highly efficient ligands for DHFR from Cryptosporidium hominis and Toxoplasma gondii inspired by structural analysis. J Med Chem. 2007;50:940–950. doi: 10.1021/jm061027h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolstad D, Bolstad E, Frey K, Wright D, Anderson A. A structure-based approach to the development of potent and selective inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase from Cryptosporidium. J Med Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1021/jm8009124. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.