Abstract

Mutations of Ca2+-activated proteases (calpains) cause muscular dystrophies. Nevertheless, the specific role of calpains in Ca2+ signalling during the onset of dystrophies remains unclear. We investigated Ca2+ handling in skeletal cells from calpain 3-deficient mice. [Ca2+]i responses to caffeine, a ryanodine receptor (RyR) agonist, were decreased in −/− myotubes and absent in −/− myoblasts. The −/− myotubes displayed smaller amplitudes of the Ca2+ transients induced by cyclopiazonic acid in comparison to wild type cells. Inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels (LCC) suppressed the caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i responses in −/− myotubes. Hence, the absence of calpain 3 modifies the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release, by a decrease of the SR content, an impairment of RyR signalling, and an increase of LCC activity. We propose that calpain 3-dependent proteolysis plays a role in activating support proteins of intracellular Ca2+ signalling at a stage of cellular differentiation which is crucial for skeletal muscle regeneration.

1. Introduction

Calpains are intracellular nonlysosomal cysteine proteases whose functions are regulated by Ca2+ (see [1] for review). These proteins indeed display one Ca2+-binding domain on each of the large and small subunits [2]. The physiological roles of the calpains are not yet fully understood but as proteases, they may regulate important cellular functions. In particular, ubiquitous calpains have been implicated in a wide variety of processes including apoptosis, myogenic differentiation, cellular division and fusion [1]. Calpains have been shown to play regulatory roles in other cells, in which they can influence gene expression through the cleavage of specific transcription factors, affecting cell viability by controlling apoptosis, and modulating other cell processes through the cleavage of specific kinases and ion channels (reviewed by Carafoli and Molinari; [3]). It was demonstrated that the absence of the skeletal muscle specific calpain 3 (from the corresponding gene capn3) causes limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A (LGMD2A) [4], a disease that has been linked to a significant level of apoptotic fibres [5]. To better understand the function of calpain 3 and the pathophysiological mechanisms of LGMD2A, an adequate model was generated by gene targeting [6]. The pathological process due to calpain 3 deficiency is associated with alterations in membrane permeability [6] suggesting the possible existence of a perturbation in homeostasis, especially in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) during muscular dystrophy.

The identification from skeletal muscle of a 94 kDa protein that possesses thiol-dependent proteolytic activity specifically directed against the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RyR) has several implications for the pathogenesis of LGMD2A [7]. In particular, it makes it possible that the dysregulation of skeletal muscle functions is, at least in part, a consequence of the lack of RyR regulation by calpain 3.

Indeed, RyR, also referred to as Ca2+-release channel, is the key protein responsible for the extremely rapid movement of Ca2+ (millions of ions per second) from the internal stores named the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to the cytosol during the process of excitation-contraction coupling. The latter is described by a plasma membrane depolarisation coming from motor neurones and activating dihydropyridine receptors or L-type Ca2+ channels (LCCs) mechanically coupled to the skeletal RyR isoform 1. In turn, Ca2+ release from RyR causes the contractile filaments to slide along one another, thus triggering the twitch of the muscle cell. Then Ca2+ has to be removed from the cytosol by extrusion through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and by reuptake into the SR by the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pump. Hence Ca2+ cycling is a fine-tuned process that requires strong control of its homeostasis.

To test the hypothesis of RyR modulation by calpain 3, we investigated the effect of caffeine, a potent activator of RyR, and cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), an inhibitor of the SERCA pump, on [Ca2+]i, which controls the excitation-contraction coupling in muscle. We measured [Ca2+]i in primary cultures of normal and capn3-deficient mice skeletal muscle cells by single cell fast fluorescence microspectrofluorometry. In vivo, satellite cells are activated into myoblasts, proliferate and fuse to form myotubes to repair damaged muscle fibres. By comparing myoblasts and myotubes in culture, we aimed to investigate the different steps involved in the process of regeneration. Our pharmacological approach enabled us to decipher the mechanisms leading to an impairment of Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle when calpain 3 is absent, as it might be the case in LGMD2A patients.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Generation of capn3-Deficient Mice

The production of capn3 −/− mice was carried out according to the well established procedure published in 2000 by Richard and collaborators [6].

2.2. Primary Skeletal Muscle Cell Culture

Muscles were excised from the upper and lower legs of adult mice, and proliferating satellite cells were isolated from these muscles by pronase digestion as previously described [8]. Cells were seeded in gelatine-coated (0.5%) glass bottom culture dishes (HBSt or GWSt-3522 series; 22 mm diameter, 0.17 mm thickness; WillCo Wells BV- Amsterdam, Netherlands) at 2 × 103 cells per cm2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 20% foetal calf serum, and incubated at 37°C in 7.5% CO2. Cells were continuously grown in this medium, which was replaced at day 3 and then every 4 days. Proliferating satellite cells were kept in culture for up to 11 days.

2.3. Indirect Immunofluorescence

Indirect immunofluorescence was done as described by Martin et al. in 1997 [9] using appropriate dilutions of primary and secondary fluorescent antibodies. The samples were observed with a Leica TCS 4D confocal microscope.

2.4. Dye Loading and Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Dye loading and intracellular free calcium measurements ([Ca2+]i) were performed as described [10–12]. The culture dishes were rinsed and incubated with 2.5 μM fura-2-AM and 0.05% w/v Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes, Inc USA) in Locke Locke's buffer (in mM): NaCl 140; KCl 5; MgCl2 1.2; CaCl2 2.2; glucose 10; HEPES-Tris 10; pH 7.25) at 34°C for 45 min. Subsequently, loaded cells were rinsed with Locke's buffer, and fluorescence measurements were carried out in buffers kept at 35–37°C throughout the time course of the experiment. Calcium-free medium (EGTA-buffer) contained (mM): EGTA, 2; NaCl, 140; KCl, 5; glucose, 10; KCl, 5; MgCl2, 1; and HEPES 10; pH 7.4. In this EGTA buffer, free Ca2+ was adjusted to 100 nM (which corresponds to the resting [Ca2+]i as determined by preliminary fura-2 measurements). [Ca2+]i levels in single cells were measured using the FFP photometer system (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) based on an inverted microscope (Axiovert-100) equipped with epifluorescence. Band pass filters (340/10 nm and 380/10 nm) were alternately positioned with a filter wheel, and the cells were excited through an oil-immersion objective (Zeiss-plan Neofluar ×100, 1.3 n.a). With fluorescence values corrected for background and dark current, [Ca2+]i was calculated from the ratio between 340 and 380 nm recordings. For the in vitro calibration of [Ca2+]i measurements based on the procedure described by Grynkiewicz et al. [13], we used Ca2+-EGTA buffer containing (mM): NaCl 140; MgCl2 2; glucose 10; HEPES 10 at pH = 7.25 adjusted with Tris-HCl. Various standards were used for system calibration as described previously [13].

2.5. Drugs

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-France. Concentrated stock DMSO solutions of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and ryanodine (Alomone Labs, Israel) were stored at −20°C. Caffeine (Almone Labs, Isreal) was dissolved directly in the working buffer at appropriate concentrations. Test solutions were prepared daily using aliquots from frozen stocks to obtain the working concentrations.

2.6. Drug Application

The control and test solutions were applied using a multiple capillary perfusion system (200 μm inner diameter capillary tubing, flow rate 500 μl/min) placed close to the cell tested (<0.5 mm). Each capillary was fed by a reservoir 50 cm above the bath. Switching the opening from one capillary to the next made complete solution changes. After each application, the cells were washed with Locke's buffer. Preincubation with inhibitory substances was carried out in a 500 μL bath containing the inhibitors diluted in Locke's buffer.

2.7. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

The results are expressed as mean ± S.D or means ± S.E.M. The number of sample size (n) given is the number of cells tested with the same protocol (control, test drug, recovery) for each group. The figures (traces) show on-line measurements of the [Ca2+]i levels before and after the application of test substances, while bar diagrams and numerical data are given as mean ± S.E.M. and represent the peak amplitude of the [Ca2+]i increase. Depending on the data, the results were analysed using ANOVA or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test. Unless otherwise stated, differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

2.8. Western Blot

Muscle samples were homogenized in 200 mM sucrose, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 200 μM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 mM diisopropylfluorophosphate (DFP). Protein samples were denatured 30 min at room temperature and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 4%–15% acrylamide gradient gels and electro-transferred to Immobilon membranes for 3 hours at 0.8 A. The membrane was blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal rabbit antibody against RyR diluted 1/10 000 [14]. After washing in PBS-T, the membrane was incubated for 3 hours at room temperature with antirabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) coupled to horseradish peroxidase. Revelation was carried out with a chemiluminescent reagent (Western lightning Chemiluminescence reagent plus, Perkin Elmer). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.9. RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from muscles by the Trizol method (Invitrogen) after pulverization using a Fast Prep FP120 apparatus (Bio101). Residual DNA was removed from the samples using the Free DNA kit (Ambion). One μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers according to the protocol “Superscript II first strand synthesis system for RT-PCR” (Invitrogen). PCR was carried out on 1/20 of the reaction with 0.2 μM of each primer. Three primer pairs were designed for capn3 in order to cover the regions of alternative splicing [4] as follows:

-

p94sys3: forward 5′-TTCACCAAATCCAACCACCG-3′ and reverse 5′-ACTCCAAGAACCGTTCCACT-3′;

-

p94sys5: forward 5′-AGACAAAGATGAGAAGGCCC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCGATCCACAGAGATTGTA-3′;

-

p94sys6: forward 5′-GACAGAGCACACAGCAACAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GTTGGCTGTTGAGATGGAAG-3′.

PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.10. Caspase 3 Activity

To determine and quantify caspase 3 function, we used the PhiPhiLux-G2D2 substrate kit (OncoImmunin, Inc., MD, USA). Briefly, the substrate is coupled to a fluorophore and when cleaved specifically by caspase 3, the fluorescence can be detected, measured and analysed (excitation and emission peaks are 552 and 580 nm, resp.).

3. Results

3.1. Morphological and Molecular Characterisation of Living Myoblasts and Myotubes

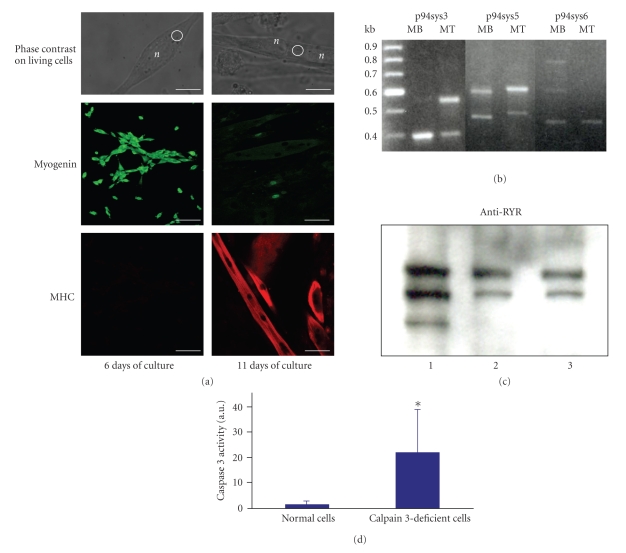

We first characterised the differentiated states of the skeletal muscle primary cultures used in this study by the expression of specific differentiation markers. At day 6 of culture, mononuclear cells from both wild type (Figure 1(a), left upper panel) and capn3-deficient (not shown) mice were uniformly positive for myogenin (Figure 1(a), left medium panel) and negative for MHC (Figure 1(a), left lower panel) confirming that they were differentiated myoblasts. After 11 days in culture, cells became multinucleated (Figure 1(a), right upper panel), and the myogenin staining was strongly reduced (Figure 1(a) right medium panel); in contrast, cells expressed prominent MHC staining (Figure 1(a) right lower panel). Therefore, at that time most myoblasts had fused into myotubes, showing a serum-induced further differentiation over culturing time, and thus for both conditions wild type and capn3-deficient (not shown) mice. As a result, in subsequent single-cell Ca2+ measurements myoblasts and myotubes were probed independently as they exhibit different differentiation states.

Figure 1.

Morphological and molecular features of skeletal muscle cells used throughout this study. (a) Phase contrast and fluorescence micrographs of murine skeletal muscle cells in primary culture. Typical morphology of the living cells (left upper panel: myoblasts; right upper panel: myotubes) used for calcium measurements observed by phase contrast microscopy. Circles indicate the region of drug application and monitoring of [Ca2+]i. Immunological staining of myogenin on myoblasts (left middle panel) and myotubes (right middle panel) was visualized by confocal microscopy using a FITC-labelled secondary antibody (green fluorescence). Myosine Heavy Chain (MHC) was similarly observed in myoblasts (left lower panel) and myotubes (right lower panel) using a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red fluorescence). Myoblasts and myotubes were obtained after 6 or 11 days in culture, respectively. (b) Detection of calpain 3-mRNA in wild type (+/+) myoblasts and myotubes by RT-PCR. Gel electrophoresis of the RT-PCR reactions obtained using the primer pairs p94sys3, p94sys5 and p94sys6 (see Section 2) on murine myoblast (MB) or myotube (MT) mRNA. (c) Detection of the ryanodine receptor in skeletal muscle from normal and capn3-deficient mice. Muscle from normal (Lane 3) and capn3-deficient mice (Lane 2) were extracted and left 30 min at room temperature to allow the cleavage of RyR and were then subjected to SDS-PAGE. Human muscle was used as control (Lane1). No difference in the cleavage pattern was observed, indicating that the partial cleavage of RyR also occurs in the absence of calpain 3 in this biochemical assay. (d) Measurement of caspase 3 activity in wild type and capn3-deficient myoblasts. The graph displays the levels of substrate cleavage expressed as means ± S.D. in arbitrary units. The results are based on 4 different experiments. The differences in the median values among the two groups are greater than would be expected by chance; there is a statistically significant difference (P = 0.029), as indicated by a Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test.

In a second set of experiments we analysed capn3 expression in myoblasts and myotubes from normal and capn3-deficient mice. RT-PCR was carried out with RNA extracted from the myoblast and myotube differentiation stages and with specific primers covering in particular the regions of capn3 alternative splicing [4]. Only weak expression was detected on capn3-deficient cells (data not shown; [6]) whereas it was present in normal cells at both stages. In addition, the differentiation process in this cell culture system was accompanied by a change in the expression pattern of calpain 3 RNA isoforms with alternative splicing forms mostly expressed in immature cells (see MB lanes in Figure 1(b) and Table 1 for semiquantification).

Table 1.

Quantification of the expression of calpain 3 transcripts in wild type myoblasts and myotubes. These data were obtained from the gel electrophoresis of the RT-PCR reactions using the primer pairs p94sys3, p94sys5 and p94sys6 on murine myoblast (MB) or myotube (MT) mRNA (see Figure 1(b)). The gel and the corresponding quantification are representative of 3 different experiments where similar results were observed. These results have to be taken qualitatively since the experiments were performed by classical RT-PCR and not by quantitative RT-PCR. Numbers are given in arbitrary units.

| Primer | p94sys3 | p94sys5 | p94sys6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type | MB | MT | MB | MT | MB | MT |

| Band 1 | 43596 | 165378 | 155681 | 205283 | 66937 | 46845 |

| Band 2 | 207433 | 89706 | 73219 | 69370 | 45719 | |

| Band 3 | 43022 | |||||

| Total | 251029 | 255084 | 228900 | 274653 | 155678 | 46845 |

During the excitation-contraction coupling phenomenon, RyR releases Ca2+ in response to depolarization of the plasma membrane. Previous publications reported the cleavage of RyR by a 94 kDa thiol protease into two fragments (375 kDa and 150 kDa fragments) [7, 15]. This cleavage results in an enhancement of Ca2+ efflux from SR vesicles. We examined this protein by western blot in normal and capn3-deficient whole skeletal muscle samples (Figure 1(c) and Table 2 for semiquantification). The cleaved fragments were obtained in both samples indicating that calpain 3 is not necessary for cleavage in whole muscle and that it most likely cannot be involved in the results dealing with the Ca2+ release from RyR in cultivated proliferating satellite cells.

Table 2.

Western blot quantification: cleavage of the ryanodine receptor in wild type and calpain 3-deficient skeletal muscles. The gel presented in Figure 1(c) was analysed in terms of band intensities (numbers are given in arbitrary units). The lower band is 58% of the higher band (fixed to 100%) in lane 2, and 51% in lane 3. The amount of the second band is related to small degradation condition (time and temperature), but is always identical in the two situations wild type and calpain 3-deficient skeletal muscles. The blot and the corresponding quantification are representative of at least 3 independent experiments showing no difference between the two types of mice.

| Sample | 1 = human skeletal muscle | 2 = capn3 −/− mouse skeletal muscle | 3 = wild type mouse skeletal muscle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band 1 | 90982 | 69472 | 52878 |

| Band 2 | 92773 | 32041 | 38331 |

| Band 3 | 49076 | ||

| Total | 232831 | 101513 | 91209 |

Deficiency in calpain 3 is known to be associated with apoptosis [5] as indicated by increases of caspase 3 activity [16]. Analysis of the cleavage of a fluorescent substrate specifically by caspase 3 was performed in cells at the myoblast stage. Figure 1(d) highlights the significant raise of caspase 3 activity in calpain 3-deficient cells in comparison to wild type cells. Caspase 3 being a marker for apoptosis, this result therefore suggests a probable increase of the apoptotic rate when calpain 3 is lacking in mouse myoblasts.

3.2. Caffeine-Induced [Ca2+]i Increase in Isolated Myoblasts and Myotubes

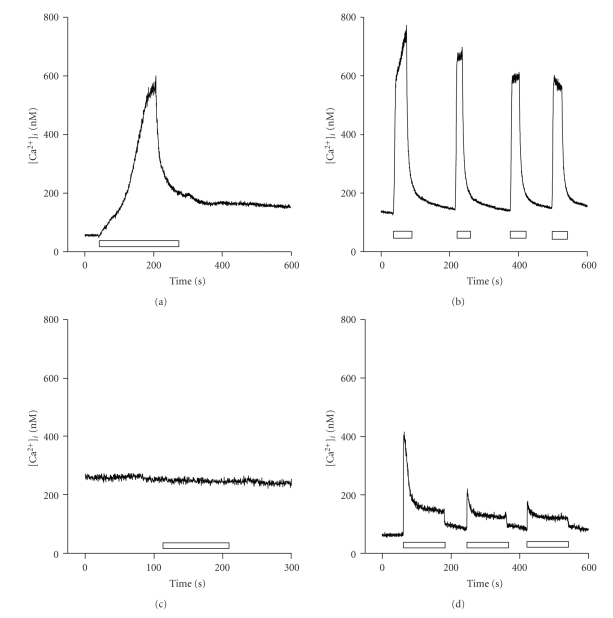

Caffeine, the best known agonist of ryanodine receptors [17], was used at 20 mM throughout the study to ensure the complete activation of the RyRs of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) [18, 19]. [Ca2+]i release by caffeine was tested on myoblasts and myotubes cultured from wild type (+/+) and capn3-deficient (−/−) mice (Figure 2). Resting [Ca2+]i levels in cell types of both +/+ and −/− mice did not change significantly (103 ± 4 nM; n = 187). After local caffeine application, +/+ myoblasts showed a single and slow increase in [Ca2+]i, that peaked after 3 minutes of caffeine application and decayed slowly, even before the caffeine was washed out (Figure 2(a)) presumably confirming the presence at this stage of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger at the plasma membrane level [20]. The number of cells responding to caffeine in these cell types is summarised in Figure 3(a). Thirty-two out of 36 +/+ myoblasts showed an increase in [Ca2+]i after the application of caffeine. No [Ca2+]i response to caffeine was observed for repeated applications (data not shown) even when the caffeine was quickly taken off. By contrast, +/+ myotubes exhibited a constant, repeated and reproducible increase in [Ca2+]i after brief (30s) and repeated applications of caffeine (Figure 2(b)). The mean peak amplitude of the [Ca2+]i response is plotted in Figure 3(b). In contrast, −/− myoblasts failed to exhibit the [Ca2+]i-induced response to caffeine in a huge majority of cells (Figure 2(c) and Figure 3(a); 66 cells out of 71). A very small response was observed in only 5 out of 71 cells (Figure 3(a)). In contrast to +/+ myotubes, a progressive desensitization of the [Ca2+]i response to repeated caffeine applications (3 min each) was observed in −/− myotubes (Figure 2(d)). In addition, the peak amplitude of the responses induced by 3 successive shots of 20 mM caffeine observed in −/− myotubes was significantly lower than in wild-type: a 60%, 75% and 90% decrease, respectively (n = 12; Figure 3(c) versus Figure 3(b)).

Figure 2.

Effect of caffeine on [Ca2+]i in isolated myoblasts and myotubes. Representative traces show the typical time course of the response to 20 mM caffeine observed in (a) wild type (+/+) myoblast; (b) wild type (+/+) myotube; (c) capn3-deficient (−/−) myoblast; (d) capn3-deficient (−/−) myotube. The duration of drug exposure is represented (open bars).

Figure 3.

Peak amplitude of [Ca2+]i response of myoblasts and myotubes to caffeine. Bar diagrams summarize the response of the cell types shown in Figure 2. (a) myoblasts (+/+ and −/−): single application of 20 mM caffeine; (b) myotubes (+/+); (c) myotubes (−/−): 3 successive applications of 20 mM caffeine. The number of cells pooled in a category and the total number of cells tested are given in brackets.

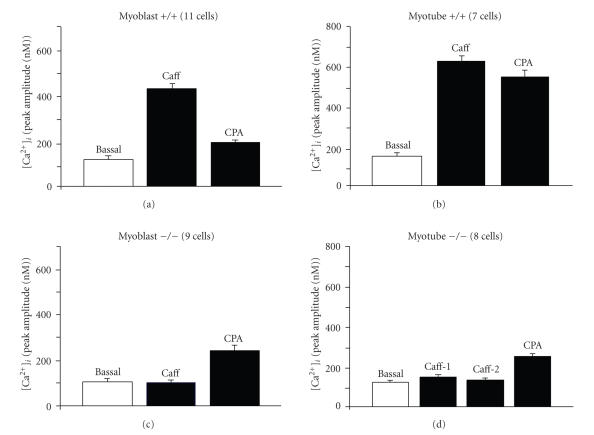

3.3. Effect of Caffeine and CPA on [Ca2+]i in Isolated Myoblasts and Myotubes from Wild Type (+/+) and capn3-Deficient (−/−) Mice

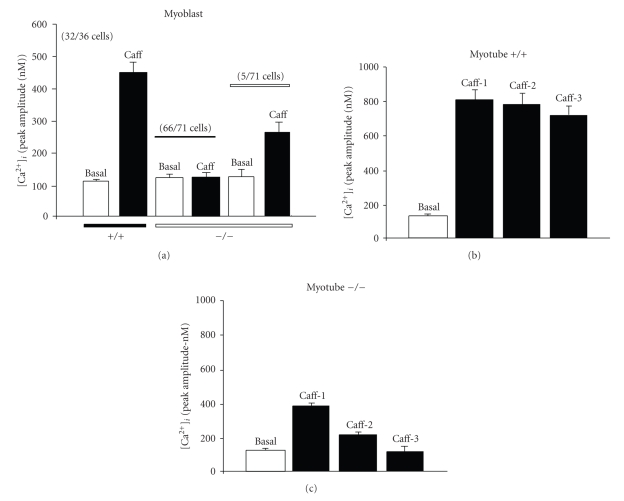

We then compared the effects of CPA to those obtained with caffeine. CPA is a potent inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase [21, 22] and induces Ca2+ mobilization from internal Ca2+ stores, preferentially depleting InsP3-sensitive stores [23]. In +/+ myoblasts CPA (10 μM) induced an increase of [Ca2+]i of much lower amplitude (Figure 4(a), right peak) than when induced by a prior exposure to caffeine (Figure 4(a); left peak). Tested on +/+ myotubes, both caffeine and CPA induced a similar [Ca2+]i increase, with a peak amplitude significantly higher (Figure 4(b)) than the one observed in myoblasts for both drugs (Figure 4(a)). The differences found between the responses to caffeine and CPA in +/+ myoblasts and +/+ myotubes was found to be significant (P < 0.05; Figures 5(a) and 5(b).

Figure 4.

Effect of caffeine and CPA on [Ca2+]i in isolated myoblasts and myotubes. Representative traces show the typical time course of the response to 20 mM caffeine and 10 μM CPA observed in (a) wild type (+/+) myoblast; (b) wild type (+/+) myotube; (c) calpain 3-deficient (−/−) myoblast; (d) calpain 3-deficient (−/−) myotube. The duration of exposure to caffeine (open bars) and CPA (gray-dashed bars) is represented.

Figure 5.

Peak amplitude of [Ca2+]i response of myoblasts and myotubes to caffeine and CPA. Bar diagrams summarize the response of the cell types shown in Figure 4. (a) myoblasts (+/+); (b) myotubes (+/+); (c) myoblasts (−/−): application of 20 mM caffeine followed by 10 μM CPA; (d) myotubes (−/−): 2 successive applications of 20 mM caffeine followed by 10 μM CPA. The number of cells tested is given in brackets.

Interestingly, in capn3-deficient cells (−/−), the [Ca2+]i responses to caffeine and CPA were quite different (Figures 4(c) and 4(d) for the parameters tested. First of all, as already illustrated in Figure 2(c), the Ca2+ response to caffeine in −/− myoblasts was totally absent (Figure 4(c) left trace), and of small amplitude in −/− myotubes (Figure 4(d) right trace). By comparison CPA induced a significant [Ca2+]i rise in −/− myoblasts (Figure 4(c) right peak), but a much smaller increase in −/− myotubes, even when CPA was applied before caffeine (Figure 4(d) left peak). The peak amplitude of the various [Ca2+]i responses was quantified and are summarised in Figure 5.

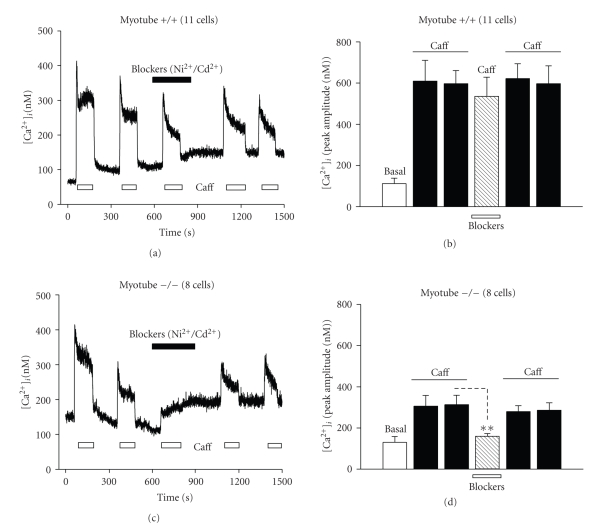

3.4. Influence of the External Ca2+ Concentration and of Ca2+ Channels at the Plasma Membrane on SR Ca2+ Release

The [Ca2+]i responses induced by caffeine were also tested in low Ca2+ EGTA-buffer to investigate the dependence upon external Ca2+ in myotubes obtained from wild type and capn3-deficient (−/−) mice. Indeed, the removal of extracellular Ca2+ did not significantly affect the [Ca2+]i responses induced by 20 mM caffeine on +/+ myotubes (results not shown). However, a major reduction in the [Ca2+]i response to caffeine was observed in −/− myotubes, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (results not shown).

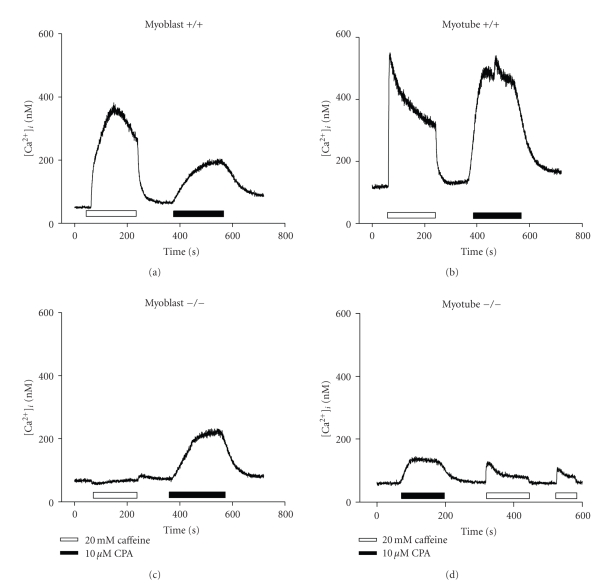

The next experimental design aimed to dissect the functional interaction between RyR and Ca2+ channels of the plasma membrane in myoblasts and myotubes of wild type and capn3-deficient (−/−) mice. In this respect, we focused our study on myotubes, because −/− myoblasts appeared insensitive to caffeine. We subjected myotubes to successive exposures to caffeine, in the absence or presence of nonspecific Ca2+ channel blockers (i.e., a mixture of 100 μM Cd2+ and 50 μM NiCl2). None of the Ca2+ channel blockers affected the [Ca2+]i response induced by caffeine in +/+ myotubes (Figures 6(a) and 6(b)). In sharp contrast, Ca2+ channel blockers significantly reduced the [Ca2+]i response induced by caffeine in −/− myotubes (Figures 6(c) and 6(d)). It is noteworthy that, at the end of the inhibition of Ca2+ entry (Figures 6(a) and 6(c)), the baseline increased further suggesting that there was a Ca2+ re-entry in both types of cells. However, the relative amplitudes of the 4th and 5th caffeine applications were still different between +/+ and −/− myotubes. Moreover, after starting the inhibition of Ca2+ entry (Figure 6(c)), the baseline decreased further suggesting that there was constitutive Ca2+ entry in −/− myotubes. In addition, in other set of experiments, the effects of various more specific blockers were examined, among them the most important Ca2+ channel sub-type blockers, such as nicardipine (L-type blocker), omega GVIA-N-type, omega MVIIC/MVIIA-a P/Q type, omega-Aga-IVA (a P/Q-type blocker), and SNX-482 (a R-type blocker). Interestingly, only nicardipine at 800 nM significantly blocked the Ca2+ response induced by caffeine in −/− myotubes (control: 568 ± 32 nM; nicardipine: 102 ± 25 nM; n = 4; P < 0.05) suggesting that the response could not be directly mediated by caffeine-sensitive channels.

Figure 6.

Effect of caffeine on [Ca2+]i in isolated myotubes in the presence of Ca2+ channel blockers (Ni2+/Cd2+). Representative traces show the typical time course of the response to 20 mM caffeine observed in (a) wild type (+/+) myotube; (c) calpain 3-deficient (−/−) myotube, each treated with Ni2+/Cd2+. The duration of exposure to caffeine (open bars), or 50 μM Ni2+/100 μM Cd2+ (closed bars) is represented. Bar diagrams (b) and (d) summarize the peak amplitude of the [Ca2+]i response of myotubes to caffeine and CPA. The responses from the wild type myotubes (+/+; b) and calpain 3-deficient myotubes (−/−; d), are shown. Fifty μM Ni2+/100 μM Cd2+ was added to the extracellular medium prior to the second application. The number of cells tested is given in brackets.

4. Discussion

Calpains are a family of Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases (for review articles, see [1–3]), the members of which are expressed ubiquitously (calpains 1 and 2) or in a tissue-specific way (calpain 3 is skeletal muscle specific and an isoform of calpain 3 was found in the lens). In addition to Ca2+ ions, the activation of ubiquitous calpains can be modulated by association with a 30 kD small sub-unit, or with membranes, by the autolysis of the N-terminus, or by calpastatin, a specific inhibitor. Their function in muscle has received increasing interest because of the finding that the activation and concentration of the ubiquitous calpains were found to be increased in the mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (mdx mice). Moreover, protein degradation was enhanced in mdx muscle [24], and it was argued that increased degradation resulted from the elevated Ca2+ levels existing within the dystrophic muscle. Possible substrates of calpains are the membrane-associated cytoskeletal proteins, the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase, and the ion channel proteins. Interestingly, the Ca2+ pump located in the plasma membrane is a preferred substrate of calpain in erythrocytes [25]. If impaired in dystrophin-deficient muscle, this calpain action would, in addition to provoking an excess of Ca2+ influx, disturb an important extrusion pathway. Calpains in normal tissue supposedly exert regulatory roles. It is therefore assumed that in the dystrophic process, a deficiency in one of the calpains would result in affecting a metabolic pathway rather than muscle proteolysis. Calpains cleave substrates at restricted locations [3] and are unlikely to be involved in mediating major house-keeping degradative functions. Thus, current evidence supports a role for pathologically-high calpain activity in muscular dystrophy through the disruption of specific regulatory mechanisms in muscle, rather than through an increase in nonspecific proteolysis.

In this study we have used mouse primary cultures of skeletal muscle from normal and capn3 −/− mice recently generated at Genethon by I. Richard's laboratory. Capn3-deficient mice are fully fertile and viable and show a mild muscular dystrophy that affects a specific group of muscles. Interestingly, affected muscles manifest a similar apoptosis-associated perturbation of the I{kappa}B{alpha}/NF-{kappa}B pathway as seen in LGMD2A patients [5] and capn3-deficient mice [6].

The availability of primary cultures of skeletal muscle cells from normal and capn3 −/− mice provides an opportunity to tackle in the near future the upstream and downstream events occurring during a pharmacologically-induced [Ca2+]i rise in myoblasts and myotubes from normal and capn3 −/− mice. Notably, it is possible that calpain 3 acts as a feedback regulator for calcium homeostasis in skeletal muscle cells by exerting an action on RyR. The latter, also known as the Ca2+ release channel of the SR, is a key protein involved in excitation-contraction coupling. Its activity is regulated by a 94 kDa thiol-protease of the junctional SR membranes which specifically cleaves one site on RyR. This cleavage results in enhanced Ca2+ efflux from SR vesicles [7, 15].

Importantly, in our hands calpain 3 seemed not to be necessary for cleavage in skeletal muscles in vitro. The cleavage of RyR in the absence of calpain 3 (muscle-specific) could be due to calpain 1 and/or 2, which are widely expressed in all cell types. The activity of these calpains could indeed be redundant in that case. To assess the activity of ryanodine-sensitive internal Ca2+ stores, we applied caffeine stimulations, caffeine being a well-known potent RyR activator [17].

The effectiveness of caffeine in normal myotubes in comparison to myoblasts indicates a maturation of proper RyR signalling in culture during the fusion process. Importantly, both myoblasts and myotubes from capn3 −/− mice displayed weaker amplitudes of the caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i transients than in normal cells, which could indicate a lower SR Ca2+ loading state in the KO skeletal cells, a decreased number of RyR at the SR membrane surface, or a decreased sensitivity of these receptors but independently of any cleavage by calpain 3.

While CPA, a compound that depletes internal Ca2+ stores [26], evoked increases of [Ca2+]i under all conditions tested, it appeared that those responses were weaker in capn3 −/− myotubes in comparison to wild-type myotubes, reinforcing the hypothesis that SR Ca2+ loading decreased in capn3 −/− myotubes or indicating that SR Ca2+-ATPases were less expressed or less sensitive to the blocker in KO myotubes. The difference in CPA responses between wild-type myoblasts and myotubes is most likely due to a change in the size of the SR that correlates with a change in the size of the cells during fusion in culture, myotubes having a larger area.

Caffeine is thought to directly activate RyR at the SR membrane, leading to the opening of this channel and the release of Ca2+ from the SR into the cytosol, independently of any Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane. The fact that low extracellular Ca2+ and blockers of LCCs abolished caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i increases in −/− myotubes suggests that RyR opening and SR Ca2+ release lead to a Ca2+ influx through LCCs solely in the KO myotubes. Since cytosolic Ca2+ is known to negatively regulate these channels (inactivation) and that the release from the SR is not sufficient to evoke a depolarization enabling the opening of LCCs [27], it is most likely that an additional channel at the plasma membrane induces a depolarization in response to the caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]i increases in −/− myotubes.

Finally, another possibility would be that the lack of calpain 3 leads to a decrease of RyR sensitivity to caffeine, probably involving a regulation of the post-translational maturation of the receptor, and thus independently of any functional cleavage of RyR. It is noteworthy that RyR contains many endogenous cysteines in the cytoplasmic domain of the protein. Hence the binding of caffeine to its site on the cytosolic face of RyR would require an activation of RyR by extracellular Ca2+ entry in order to induce the proper opening of the receptor.

Taken together, the results obtained in −/− myotubes indicate: (i) a decrease of the SR load, (ii) an alteration of RyR signalling, (iii) an increase of LCC activity (i.e., constitutive Ca2+ entry), but (iv) no increase of the basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration. As the major system of Ca2+ extrusion from the cytosol is the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, it is very tempting to speculate that the activity of the exchangers could be increased (higher protein expression and/or higher rate of ion flow) in KO myocytes to maintain the level of Ca2+ in the cells. However, this will be the subject for another specific investigation.

In conclusion, by using a knockout strategy, we could induce a skeletal muscle dystrophy in mice due to the absence of calpain 3 and thus draw a general picture of the cellular pathways involved in this disease. The LGMD2A dystrophy is characterised by (i) an increase of caspase 3 activity, (ii) a deregulation of the I{kappa}B{alpha}/NF-{kappa}B pathway leading to apoptosis [5, 16], (iii) an increase of membrane permeability, (iv) a decrease in the size of the SR and v) a dysfunction of RyR signalling. Indeed, our pharmacological study sheds more light on the mechanism of Ca2+ remodelling in the failing skeletal muscle, and we propose a major regulatory role for capn3 on SR Ca2+ release, probably mediated by an increased participation of LCC in Ca2+ entry to compensate for the alteration of SR functionality. Moreover, calpain-dependent proteolysis might be involved not only in the regulation of RyR channels themselves, but also in the activation by splitting of RyR auxiliary proteins forming the RyR1 multi-protein complex.

Of interest, recent work from our group showed that not calpain 3, but μ-calpain is important for the phenomenon of excitation-contraction (Ca2+-induced) uncoupling in normal and capn3 −/− skeletal muscle fibres [28], suggesting that the pattern of activities and functions of the different calpains is quite complex and that each calpain seems to play a very specific and defined role in the regulation of Ca2+ signalling.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Keith Langley, Montpellier, France and James Dutt, IEM AS CR, Prague, Czech Republic, for critical reading and language editing of the manuscript. The authors also would like to thank Mr. Will Veen (WillCo Wells B.V., Amsterdam, NL) for his generous gift of glass-bottom cover dishes for Ca2+ measurement experiments. This work was supported by grants to S. B. from the “Association Française contre les Myopathies”. The first author is supported by the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Invitation Fellowship Program (no. 2004 & FY2008; S-08216). G. Dayanithi is “Directeur de Recherche au CNRS-France”.

References

- 1.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83(3):731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croall DE, DeMartino GN. Calcium-activated neutral protease (calpain) system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiological Reviews. 1991;71(3):813–847. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carafoli E, Molinari M. Calpain: a protease in search of a function? Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;247(2):193–203. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, et al. Mutations in the proteolytic enzyme calpain 3 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Cell. 1995;81(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baghdiguian S, Martin M, Richard I, et al. Calpain 3 deficiency is associated with myonuclear apoptosis and profound perturbation of the IκB α/NF-κB pathway in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(5):503–511. doi: 10.1038/8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard I, Roudaut C, Marchand S, et al. Loss of calpain 3 proteolytic activity leads to muscular dystrophy and to apoptosis-associated IκBα/nuclear factor κB pathway perturbation in mice. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;151(7):1583–1590. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Weil S, Meyer H, Varsanyi M, Heilmeyer LMG. Endogenous, Ca2+-dependent cysteine-protease cleaves specifically the ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel in skeletal muscle. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1994;142(3):281–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00233435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alterio J, Courtois Y, Robelin J, Bechet D, Martelly I. Acidic and basic fibroblasts growth factor mRNAs are expressed by skeletal muscle satellite cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1990;166(3):1205–1212. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin SJ, Audrain MAP, Oksman F, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997;20(1):45–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert RC, Dayanithi G, Moos FC, Richard Ph. A rise in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of isolated rat supraoptic cells in response to oxytocin. Journal of Physiology. 1994;478(2):275–287. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayanithi G, Widmer H, Richard Ph. Vasopressin-induced intracellular Ca2+ increase in isolated rat supraoptic cells. Journal of Physiology. 1996;490(3):713–727. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamen F, Alonso G, Shibuya I, et al. Impaired somatodendritic responses to pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) of supraoptic neurones in PACAP type I-receptor deficient mice. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(9):871–881. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marty I, Robert M, Villaz M, et al. Biochemical evidence for a complex involving dihydropyridine receptor and ryanodine receptor in triad junctions of skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(6):2270–2274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shevchenko S, Feng W, Varsanyi M, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Identification, characterization and partial purification of a thiol-protease which cleaves specifically the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1998;161(1):33–43. doi: 10.1007/s002329900312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benayoun B, Baghdiguian S, Lajmanovich A, et al. NF-κB-dependent expression of the antiapoptotic factor c-FLIP is regulated by calpain 3, the protein involved in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. FASEB Journal. 2008;22(5):1521–1529. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8701com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang R, Zhang L, Bolstad J, et al. Residue Gln4863 within a predicted transmembrane sequence of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) is critical for ryanodine interaction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(51):51557–51565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fessenden JD, Chen L, Wang Y, et al. Ryanodine receptor point mutant E4032A reveals an allosteric interaction with ryanodine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(5):2865–2870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang T, Allen PD, Pessah IN, Lopez JR. Enhanced excitation-coupled calcium entry in myotubes is associated with expression of RyR1 malignant hyperthermia mutations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(52):37471–37478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naro F, De Arcangelis V, Coletti D, et al. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ induced by elevation of extracellular Ca2+ in skeletal myogenic cells. American Journal of Physiology. 2003;284(4):C969–C976. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00237.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khandoudi N, Percevault-Albadine J, Bril A. Consequences of the inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase on cardiac function and coronary flow in rabbit isolated perfused heart: role of calcium and nitric oxide. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1998;30(10):1967–1977. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okon EB, Golbabaie A, van Breemen C. In the presence of L-NAME SERCA blockade induces endothelium-dependent contraction of mouse aorta through activation of smooth muscle prostaglandin H2/thromboxane A2 receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;137(4):545–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jabr RI, Toland H, Gelband CH, Wang XX, Hume JR. Prominent role of intracellular Ca2+ release in hypoxic vasoconstriction of canine pulmonary artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;122(1):21–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner PR, Westwood T, Regen CM, Steinhardt RA. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988;335(6192):735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salamino F, Sparatore B, Melloni E, et al. The plasma membrane calcium pump is the preferred calpain substrate within the erythrocyte. Cell Calcium. 1994;15(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dayanithi G, Mechaly I, Viero C, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ regulation in rat motoneurons during development. Cell Calcium. 2006;39(3):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bers DM. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verburg E, Murphy RM, Richard I, Lamb GD. Involvement of calpains in Ca2+-induced disruption of excitation-contraction coupling in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296(5):C1115–C1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00008.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]