Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease with complex and strong genetic inheritance. Four genes have been established to either cause familial early onset AD (APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2) or to increase susceptibility for late onset AD (APOE). To date ∼80% of the late onset AD genetic variance remains elusive. Recently our genome-wide association screen identified four novel late onset AD candidate genes. Ataxin 1 (ATXN1) is one of these four AD candidate genes and has been indicated to be the disease gene for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, which is also a neurodegenerative disease. Mounting evidence suggests that the excessive accumulation of Aβ, the proteolytic product of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), is the primary AD pathological event. In this study, we ask whether ATXN1 may lead to AD pathogenesis by affecting Aβ and APP processing utilizing RNA interference in a human neuronal cell model and mouse primary cortical neurons. We show that knock-down of ATXN1 significantly increases the levels of both Aβ40 and Aβ42. This effect could be rescued with concurrent overexpression of ATXN1. Moreover, overexpression of ATXN1 decreased Aβ levels. Regarding the underlying molecular mechanism, we show that the effect of ATXN1 expression on Aβ levels is modulated via β-secretase cleavage of APP. Taken together, ATXN1 functions as a genetic risk modifier that contributes to AD pathogenesis through a loss-of-function mechanism by regulating β-secretase cleavage of APP and Aβ levels.

Keywords: Diseases/Alzheimer Disease, Diseases/Amyloid, Diseases/Genetic, Diseases/Neurodegeneration, DISEASES/Neurological, Neurochemistry, Neurobiology/Neuroscience

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that is clinically characterized by deterioration of memory and cognitive function, progressive impairment of daily living activities, and several neuropsychiatric symptoms (1). On the cellular and molecular levels, the pathophysiology of AD is characterized by two distinctive features: amyloid plaques comprised primarily of a small peptide named Aβ (2–4), and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated Tau. Although Aβ42 and Aβ40 are the two primary Aβ species, Aβ42 is more prevalent than Aβ40 in amyloid plaques. Considerable genetic, biochemical, and molecular biological evidence suggests that the excessive accumulation of Aβ is the primary pathological event leading to AD (2, 4, 5). Aβ is produced by a sequential proteolytic cleavage of a type I transmembrane protein, β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) (6). The initial cleavage of APP can occur through α- or β-secretase (or BACE1). α-Secretase cleavage produces sAPPα and the α-C-terminal fragment (C83); β-secretase cleavage produces sAPPβ and the β-C-terminal fragment (C99). Following trophic factor deprivation, sAPPβ can be further cleaved by an unidentified protease, to produce N-APP, which contains the N-terminal 286 amino acids of APP (7). C83 and C99 can be further cleaved by γ-secretase to produce P3 or Aβ.

AD is a genetically complex disease and only four genes have been established to either cause early onset autosomal dominant AD with complete penetrance (APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2) or to increase susceptibility for late onset AD with partial penetrance (APOE) (3). All four confirmed genes increase the absolute Aβ levels or the ratios of Aβ42 to Aβ40, which enhances the oligomerization of Aβ into neurotoxic assemblies (3, 5). To date ∼80% of the late onset AD genetic variance remains elusive (8). Our laboratory recently performed a genome-wide association screen (GWAS) and identified four novel late onset AD candidate genes that achieved genome-wide statistical significance (beyond APOE) (9). Among the four AD candidate genes, Ataxin 1 (ATXN1) has also been shown to cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). As a different neurodegenerative disease from AD, SCA1 is characterized by ataxia, progressive motor deterioration, and loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (10, 11).

It has been shown that ATXN1 leads to SCA1 through a primary gain-of-function mechanism through the expanded polyglutamine tract and functional domains (11). However, the cellular and molecular mechanism by which ATXN1 contributes to AD pathogenesis is still unknown. Thus, in our current study, we aim to characterize the biological roles of ATXN1 and address the molecular mechanism by which ATXN1 affects AD pathogenesis. Determining ATXN1-mediated pathological events in AD will help develop a better understanding of AD pathogenesis and identify novel AD therapeutic targets.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Mouse Primary Cortical Neuron Culture

The H4 human neuroglioma cell line stably overexpressing human APP751 (H4-APP751) has been reported previously (12, 13). The stable H4-APP-C99 cell line stably overexpressing APP-C99 has been described previously (13). APP-C99, the product of β-secretase, contains α- and γ-secretase (but not β-secretase) sites. The stable H4-APP-C99 cell line provides a valid system to assess whether any effects on APP processing are dependent on β-secretase. These cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 200 μg/ml of G418. Mouse primary cortical neurons were from Brainbits (E18) and were cultured in B27/Neurobasal medium supplemented with 1× GlutaMAX (Invitrogen).

Plasmids, Chemicals, and Antibodies

The ATXN1-cDNA that overexpresses ATXN1 (Origene Inc. number SC314762) was inserted into a pCMV-derived vector (Origene Inc. number PCMV6XL5). The APP C-terminal antibody (targeting the last 19 amino acids of APP751, APP750, or APP695; A8717; 1:1000) was purchased from Sigma. The sAPPβ antibody (targeting ISEVKM, the C terminus of human sAPPβ wild type, 2 μg/ml or 1:50) was from IBL. The 6E10, anti-APP antibody was purchased from Covance and utilized for detection of sAPPα (1:1000). The ATXN1 antibodies (76-3 and 76-8) were from the University of California, Davis/National Institutes of Health NeuroMab Facility (1:1000). β-Actin antibody (1:10,000) was purchased from Sigma. The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit) (1:10,000) were purchased from Pierce.

siRNAs

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were obtained from Dharmacon, Inc. Four different individual on-target siRNAs were synthesized to target different regions of ATXN1: A, GGGAATAGGTTTACACAAA; B, GGTCTAATGTAGGCAAGTA; C, CCAGCCAGCTCTTTGATTT; D, GAAGAACGGCTCTGTTAAA. A smart-pool on-target siRNA was also obtained from Dharmacon, Inc. in which the four siRNAs were combined in equal molar concentrations (represented by ATXN1-consruct E siRNA). The control siRNA was a scrambled siRNA from Dharmacon, Inc. The smart-pool accell siRNA targeting mouse ATXN1 and control accell siRNA were obtained from Dharmacon, Inc.

Transfection

Transfections of on-target siRNAs were performed using the 96-well nucleofection shuttle system from Lonza (previously Amaxa; SF solution; DS137 program) and have been reported previously (12, 14). Cells were mixed with siRNA or plasmid DNA, and resuspended in transfection solution according to the manufacturer's protocol. The transfected cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. The mouse primary cortical neurons were transfected with the accell ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNAs as recommended by the manufacturer's protocols and harvested 72 h after transfection.

Aβ Measurement

Aβ measurement was performed following the manufacturer's suggested protocols and as described previously (15). In brief, Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (pg/ml) were quantified using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay (Wako and Signet). Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were normalized to the protein concentrations from the cell lysates. Normalized Aβ40 and Aβ42 values from the treatments were represented as relative values by comparing to control treatment.

Cell Lysis and Protein Amount Quantification

Cells were lysed in the Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermoscientific) with 1× Halt protease inhibitor mixture (Thermoscientific). The lysates were collected and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min. Pellets were discarded and supernatants were transferred into a new Eppendorf tube (16). Total proteins were quantified by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

Western Blotting Analysis

Western blotting analysis was carried out by the method described previously (15, 16). Briefly, after centrifugation and protein concentration measurement, an equal amount of each protein sample was applied for electrophoresis followed by membrane transfer, antibody incubation, and signal development. The VersaDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad) was used to develop the blots and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) was used to quantify the proteins of interest by subtracting the background, following the protocols described previously (15, 16).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc.) and was described previously (15). RNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Themofisher Inc.). Equal quantities of RNA samples were subjected to cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript III first strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). We used a multiplex system to measure the relative amount of cDNA. Primers/probes that targeted our gene of interest were labeled with FAM490 (Applied Biosystems, Inc.; ATXN1, Hs00165656_ m1 or Mm00485928_m1; and APP, Hs01552283_m1 or Mm00431827_m1). The housekeeping gene, β-actin, was used as the endogenous control and was labeled with a VIC/MGB probe (Applied Biosystems, Inc.; human, 4326315E; mouse, 4352341E). 1:10 diluted cDNAs were mixed with 2× PCR Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and amplified using an iCycler Real-time PCR System following the manufacturer's directions (Bio-Rad). To determine differences in mRNA levels from the treatments, we utilized the ΔΔCt method (17).

Data Analysis

Aβ40 and Aβ42, as well as sAPPα and sAPPβ levels were normalized to the BCA values from the same cell lysates (14). β-Actin was used in the Western blotting analysis or quantitative PCR analysis to account for any differences in loading. The levels of proteins, e.g. ATXN1, C83, and full-length APP, were normalized to the corresponding values from the same lane. The normalized sAPPα and sAPPβ values were divided by normalized full-length APP levels from each sample. The values from the ATXN1 siRNA treatment were normalized to control siRNA treatment. The samples for each treatment were from at least three for each experimental group and were demonstrated as mean ± S.E. We used a two-tailed t test, as appropriate, to compare the differences between two groups. The Bonferroni correction analysis was used to correct for multiple comparisons within a single experiment. p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Down-regulation of ATXN1 Increases Aβ40 and Aβ42 Levels in H4-APP751 Cells

Our first aim was to study whether down-regulation of endogenous ATXN1 could alter Aβ levels. We first established the experimental conditions under which ATXN1 siRNA treatment could significantly decrease ATXN1 protein levels in stable H4-APP751 cells. H4-APP751 cells were transfected with different ATXN1 siRNAs (siATXN1) or control siRNA (siCtrl) using the Amaxa nucleofector (13, 14). Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection and cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis. The ATXN1 antibody (76-3) has been reported previously and was used to detect ATXN1 protein (18). β-Actin, a housekeeping gene, was used as a negative control. All the ATXN1 siRNA treatments significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels by quantitative analysis compared with control siRNA treatment (siATXN1-A, 79.5%; siATXN1-B, 85.0%; siATXN1-C, 74.5%; siATXN1-D, 78.3%; siATXN1-E, 81.1%) (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1, A and B).

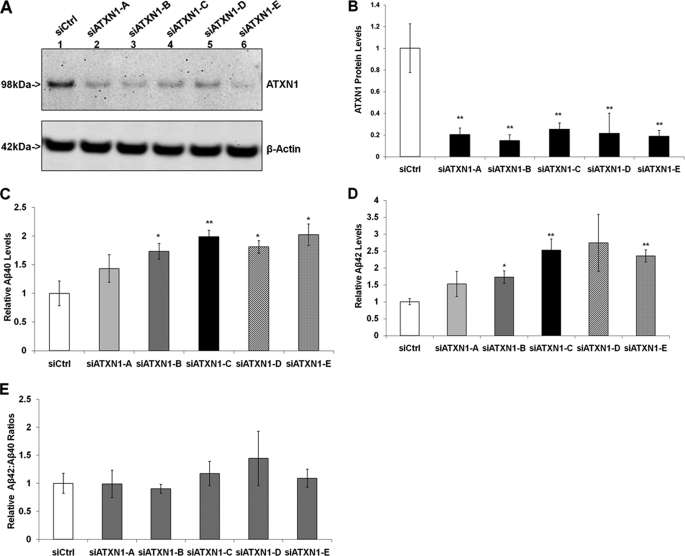

FIGURE 1.

Down-regulation of ATXN1 significantly increases Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in H4-APP751 cells. Stable H4-APP751 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) or different ATXN1 siRNA constructs (siATXN1) and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis to assess ATXN1 protein, and conditioned medium was applied to ELISA analysis to measure Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A and B, quantitative Western blotting analysis showed that all ATXN1 siRNA treatments significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels compared with control siRNA treatment. C, ATXN1 siRNA treatment increased Aβ40 levels compared with control siRNA treatment. D, ATXN1 siRNA treatment increased the Aβ42 levels compared with control siRNA treatment. E, ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not alter the ratios of Aβ42:Aβ40 compared with control siRNA treatment (p > 0.05). n = 4 for each experiment group; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus siCtrl.

We next measured Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in the conditioned medium 48 h after the transfection. Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were measured using ELISA and normalized to the cell lysate protein concentration from the same sample. All five different ATXN1 siRNA treatments increased Aβ40 levels compared with control siRNA treatment (43.3, 73.3, 99.0, 80.9, and 102.1% by siATXN1 constructs A, B, C, D, and E, respectively) (Fig. 1C). In addition, all five different ATXN1 siRNA treatments increased Aβ42 levels compared with control siRNA treatment (52.5, 72.9, 152.6, 174.0, and 135.4% by siATXN1 constructs A, B, C, D, and E, respectively) (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these findings showed that knock-down of ATXN1 significantly increased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels.

We also assessed whether ATXN1 siRNA treatment increased the ratio of Aβ42:Aβ40. It has been shown that most familial AD mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 increase the ratio of Aβ42:Aβ40, which drives the aggregation of Aβ into neurotoxic oligomeric assemblies (3, 5). The ratio of Aβ42:Aβ40 in cells treated with ATXN1 siRNAs had no significant difference compared with cells treated with control siRNA (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1E).

Validation of ATXN1 Knock-down Effects on Aβ40 and Aβ42 Levels

Next, we validated the down-regulation effect of ATXN1 on Aβ levels by overexpression of ATXN1. H4-APP751 cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) and/or ATXN1 siRNA (siATXN1), as well as the empty vector (pCMV) and/or ATXN1-cDNA and applied to Western blotting analysis and ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The combination of siATXN1/pCMV treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels compared with the siCtrl/pCMV treatment, as expected (Fig. 2A). The combination of siATXN1/ATXN1 treatment markedly increased ATXN1 protein levels, and decreased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, compared with the siCtrl/pCMV treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2, A and B). The siCtrl/ATXN1 treatment dramatically increased ATXN1 protein levels, and decreased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, compared with the siCtrl/pCMV treatment (Fig. 2, A and B). There was no significant difference in either Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels between the siATXN1/ATXN1 and siCtrl/ATXN1 (p > 0.05). This might be due to the effect of ATXN1, which is endogenously highly expressed (11) and becomes saturated during overexpression. Thus, the ATXN1 siRNA effect on both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels is not an off-target effect, and can be rescued by concurrently introducing the ATXN1 cDNA.

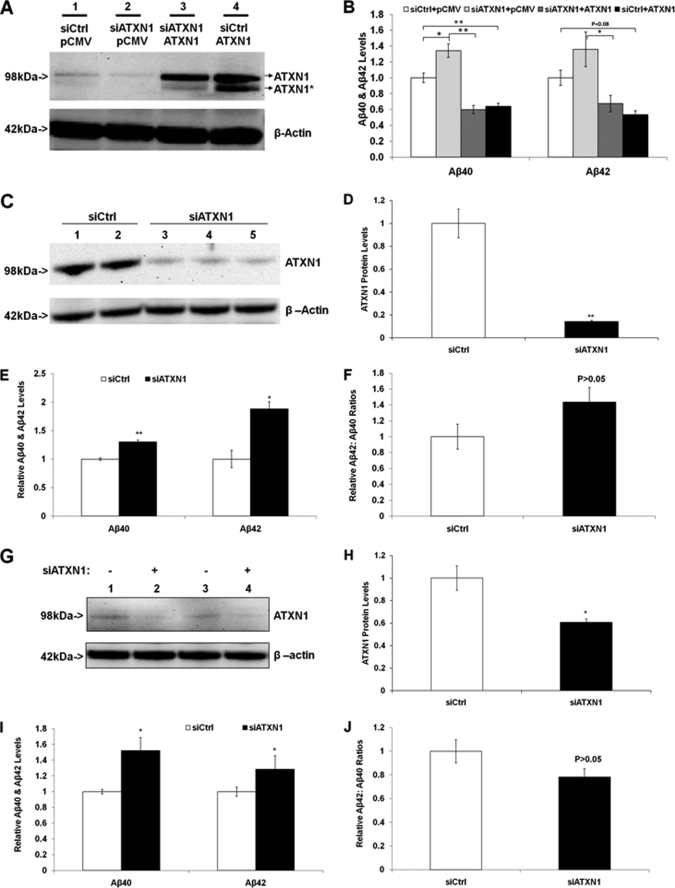

FIGURE 2.

Validation of ATXN1 loss-of-function effect on Aβ levels: it can be rescued by ATXN1 overexpression in H4-APP751 cells; and additionally ATXN1 siRNA elevated Aβ levels in naive H4 cells and mouse primary cortical neurons. A, H4-APP751 cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) and/or ATXN1 siRNA (siATXN1), as well as the empty vector (pCMV) and/or ATXN1-cDNA and applied to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, samples in A were applied to ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ATXN1 cDNA not only decreased Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (comparing siCtrl/pCMV and siCtrl/ATXN1), but also rescued the ATXN1 siRNA effect on Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (comparing siATXN1/pCMV and siATXN1/ATXN1). C–F, naive H4 cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) or ATXN1 siRNA (siATXN1) and applied to Western blotting analysis or ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels (C and D), as well as increased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (E), but did not significantly change the ratios of Aβ42:Aβ40 (F). G–J, mouse primary cortical neurons were transfected with control siRNA or ATXN1 siRNA and applied to Western blotting analysis or ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels (G and H), and increased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (I), but did not significantly change the ratios of Aβ42:Aβ40 (J) compared with control siRNA treatment. n = 3 for each experimental group; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control.

Next we asked whether the effects of ATXN1 knock-down on Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in H4-APP751 cells can also be observed in naive H4 cells. Naive H4 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA or the ATXN1 siRNA and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates were applied to Western blotting analysis. ATXN1 antibody (76-3) was utilized to reveal the ATXN1 protein. Quantitative Western blotting analysis showed that ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels by 85.7% (p < 0.01 versus control) (Fig. 2, C and D). Conditioned medium from the treatments was applied to ELISA analysis to measure Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, and then normalized to the corresponding cell lysate protein concentrations. Normalized Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels from ATXN1 siRNA treatments were compared with the values from control siRNA treatment. It was shown that ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly increased Aβ40 levels by 30.4% (p < 0.01) and the Aβ42 levels by 88.0% (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). Additionally our data showed that ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly alter the ratios of Aβ42:Aβ40 compared with control siRNA treatment (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2F).

We also validated the effect of ATXN1 knock-down on Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in mouse primary cortical neurons. The mouse cortical neurons were transfected with ATXN1 accell siRNA or control siRNA and harvested 72 h post-transfection. Cell lysates were applied to quantitative Western blotting analysis and ATXN1 antibody (76-8) was utilized to reveal the ATXN1 protein. ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 protein levels by 40.0% compared with control siRNA treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2, G and H). Conditioned medium was applied to ELISA analysis to measure Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels. Normalized Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels from ATXN1 siRNA treatment were compared with control. The ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly increased Aβ40 levels by 49.8% (p < 0.05) and the Aβ42 levels by 19.5% compared with control siRNA treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2I). Additionally there existed no differences on the ratios of Aβ42:Aβ40 between the samples from ATXN1 siRNA treatment and those from control siRNA treatment (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2J). Collectively, these data from naive H4 cells and mouse primary cortical neurons recapitulated those from H4-APP751 cells, supporting that the silencing of endogenous ATXN1 leads to increased Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels.

ATXN1 Loss of Function Elevates Aβ Levels by Modulating APP Processing

After we found that knock-down of ATXN1 increased Aβ levels, we studied whether knock-down of ATXN1 can affect APP protein levels and its proteolytic processing. First, stable H4-APP751 cells were transfected with different ATXN1 siRNAs and control siRNA. Conditioned medium and cell lysates were collected 48 h post-transfection and subjected to Western blotting analysis. Antibody APP8717 was used to detect full-length APP and its C-terminal fragments. β-Actin antibody was used as the loading control. The ATXN1 siRNAs (siATXN1-C, -D, and -E) did not change full-length APP levels (p > 0.05), whereas the ATXN1 siRNA (siATXN1-A and -B) modestly increased full-length APP levels by ∼30% (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3, A and B).

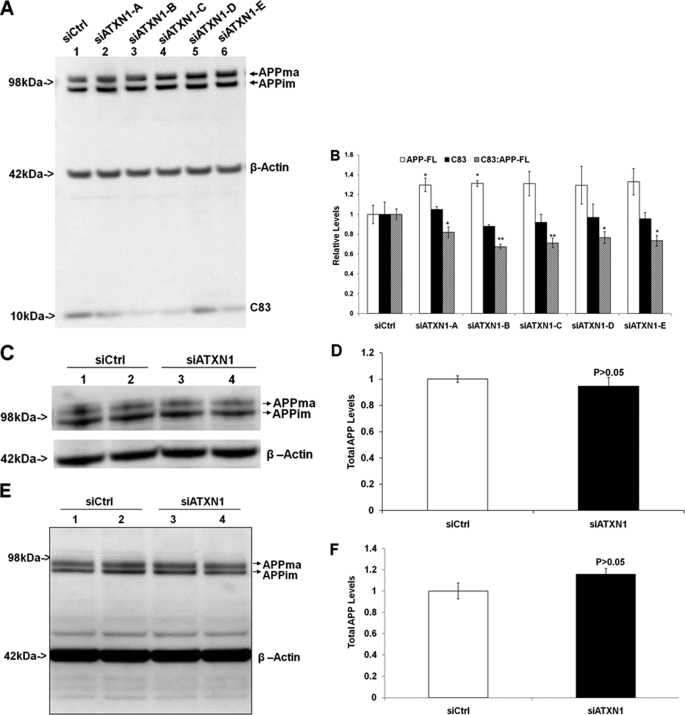

FIGURE 3.

Down-regulation of ATXN1 alters APP processing activity. A, H4-APP751 cells were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA (siCtrl) and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates were applied to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, graphic representation of data from A as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The ATXN1 siRNAs (siATXN1-C, -D, and -E) did not change full-length APP levels (p > 0.05), whereas the ATXN1 siRNA (siATXN1-A and -B) modestly increased full-length APP levels (p < 0.05). The ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not alter C83 levels alone, but decreased the ratio of C83:full-length APP compared with control siRNA treatment (n = 4). C, naive H4 cells treated with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA were applied to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, graphic representation of data from C as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly change full-length APP levels (n = 3). E, mouse primary cortical neurons were treated with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA and applied to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, graphic representation of data from E. ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly change full-length APP levels. n = 3 for each experimental group; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control.

We next examined whether ATXN1 down-regulation affected APP processing by assessing the ratios of its proteolytic cleavage fragment levels to full-length APP levels. ATXN1 siRNA treatments did not significantly alter the absolute C83 levels compared with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3, A and B). But ATXN1 siRNA treatments significantly decreased the ratio of C83:APP-FL compared with control siRNA treatment (18.0, 32.6, 28.9, 23.5, and 26.6% by ATXN1 constructs A, B, C, D and E, respectively) (Fig. 3, A and B). Thus, down-regulation of wild type ATXN1 modulates APP processing.

Then we assessed the effects of ATXN1 down-regulation in naive H4 cells and mouse primary cortical neurons. Naive H4 cells were transfected with human ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA. Mouse primary cortical neurons were transfected with mouse accell ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA. Cells were harvested and applied to Western blotting analysis. Antibody APP8717 was used to detect full-length APP. β-Actin antibody was used to detect β-actin, which was used a loading control. The ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly change full-length APP levels in naive H4 cells (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4, C and D) or in mouse primary cortical neurons (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3, E and F). Taken together, down-regulation of wild type ATXN1 increases Aβ levels via modulating APP processing, rather than APP levels.

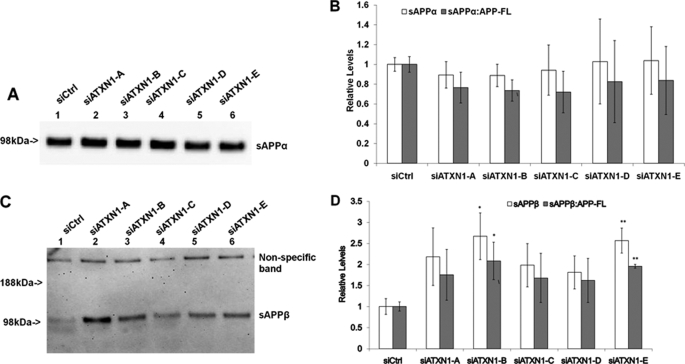

FIGURE 4.

Knock-down of ATXN1 potentiates β-secretase processing of APP. A, H4-APP751 cells were transfected with different ATXN1 siRNAs and control siRNA (siCtrl) and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Conditioned medium was applied to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, graphic representation of data from A. The sAPPα levels were divided by full-length APP levels from the same samples to represent the ratio of sAPPα:APP-FL. ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not change the sAPPα levels (p > 0.05 versus control). ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly alter the ratio of sAPPα to full-length APP (p > 0.05 versus control). C, H4-APP751 cells were transfected with different ATXN1 siRNAs and control siRNA and harvested 48 h post-transfection. The sAPPβ-specific antibody was used to detect sAPPβ in the conditioned medium. D, graphic representation of data from C. The sAPPβ levels were compared with full-length APP levels from the same samples. ATXN1 siRNA treatment elevated both the sAPPβ levels and the ratio of sAPPβ to full-length APP. n = 4 for each experimental group; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus corresponding controls.

ATXN1 Loss of Function Potentiates BACE1 Cleavage of APP

To further study APP proteolytic processing, we assessed secreted APP products, including sAPPα and sAPPβ, from the conditioned medium. 6E10 antibody was used to detect sAPPα protein. sAPPα levels were quantified and normalized to the cell lysate protein levels from the same samples. The ratio of sAPPα to full-length APP was calculated by dividing normalized sAPPα values by full-length APP values (normalized to β-actin) from the same samples. ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not change the absolute sAPPα levels compared with control siRNA treatment (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4, A and B). Each of the ATXN1 siRNA treatments decreased the ratio of sAPPα to full-length APP levels, but did not reach a statistically significance level (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4B).

The sAPPβ antibody was used to detect the sAPPβ protein from the cell medium. We quantified sAPPβ levels and normalized them to the cell lysate protein levels. We then compared the normalized sAPPβ levels to full-length APP levels (normalized to β-actin). Each of the ATXN1 siRNA treatments increased sAPPβ levels and the ratio of sAPPβ:APP-FL compared with control siRNA treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). Specifically, sAPPβ levels were increased 118.3, 167.0, 98.1, 81.1, and 157.0% by treatment of siATXN1 constructs A, B, C, D, and E, respectively. The ratios of sAPPβ:APP-FL were increased by 75.3, 108.2, 67.8, 62.0, and 95.6% by treatment of siATXN1 constructs A, B, C, D and E, respectively (Fig. 4, C and D).

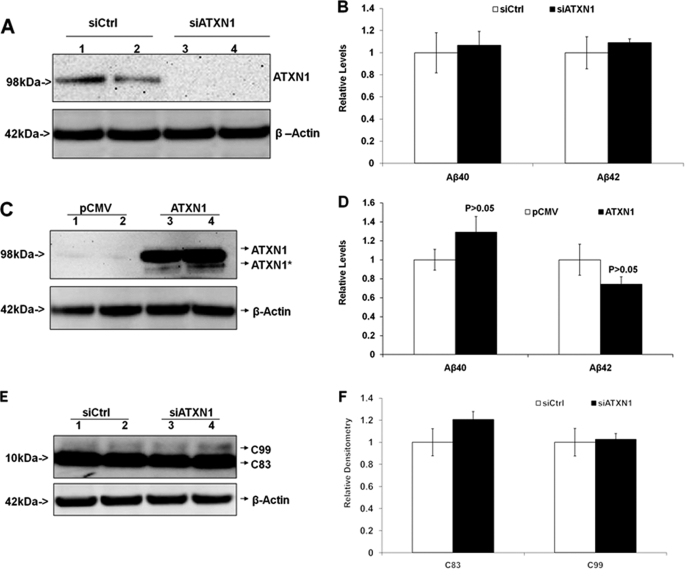

Validation of ATXN1 Knock-down Affecting Aβ Levels and APP Processing through β-Secretase

We have shown that knock-down of ATXN1 significantly potentiated β-secretase cleavage of APP, which increases both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels. Next, we utilized stable H4-APP-C99 cells to validate this finding. The stable H4-APP-C99 cell line has saturated β-secretase activity and provides a valid system to assess whether any effects on APP processing are dependent on β-secretase (12). First, H4-APP-C99 cells were transiently transfected with ATXN1 siRNA and control siRNA. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection and applied to Western blotting analysis and ELISA. ATXN1 siRNA treatment markedly decreased ATXN1 protein levels (Fig. 5A). ELISA revealed that there was no difference in Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels in the cells treated with ATXN1 siRNA compared with those treated with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5B). Next, H4-APP-C99 cells were transiently transfected with ATXN1-cDNA or the empty vector. ATXN1-cDNA treatment markedly increased ATXN1 protein levels, but did not change the levels of Aβ40 or Aβ42 compared with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5, C and D). Additionally, Western blotting analysis with anti-APP antibody APP8717 revealed no detectable difference in the protein levels of C83 and C99 in cells treated with ATXN1 siRNA compared with those treated with control siRNA (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5, E and F). Thus, knock-down of ATXN1 had no effect on APP processing or Aβ levels in H4-APP-C99 cells, which suggested that ATXN1 levels modulate APP processing and amyloid β-protein levels via a β-secretase-dependent/γ-secretase-independent mechanism.

FIGURE 5.

Modulation of ATXN1 levels does not alter APP processing or Aβ levels in H4-APP-C99 cells. A and B, H4-APP-C99 cells were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA (siCrtl) and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates and conditioned medium were applied to Western blotting analysis and ELISA, respectively, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ATXN1 siRNA treatment markedly decreased the ATXN1 protein level. B, there were no differences in Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels between the cells treated with ATXN1 siRNA and those treated with control siRNA. C and D, H4-APP-C99 cells were transfected with ATXN1-cDNA or pCMV empty vector and harvested 48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates and conditioned medium were applied to Western blotting analysis and ELISA. C, ATXN1-cDNA treatment markedly increased ATXN1 protein levels. D, ATXN1-cDNA did not change either Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels (p > 0.05; versus control). E and F, cell lysates from A (H4-APP-C99 cells treated with ATXN1 or control siRNAs) were applied to Western blotting analysis, and probed with APP8717 and β-actin antibodies. F, graphic representation of data from E. There existed no significant differences in the levels of APP-C83 or APP-C99. n = 3 for each experimental groups; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus corresponding controls.

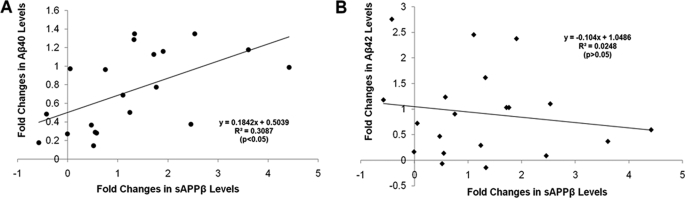

Alteration in sAPPβ Levels Correlates with Changes in Aβ40 Levels, but Not Aβ42 Levels

Collectively, our data showed that ATXN1 significantly altered the levels of Aβ and sAPPβ. Here we asked whether there was a correlation between the levels of Aβ40 or Aβ42, and sAPPβ, by consolidating the previous data in a regression study. Levels of sAPPβ were plotted with levels of Aβ40 or Aβ42 from the same samples, and represented as a -fold change by comparing the siATXN1-treated samples to the control. The x axis was represented by the -fold changes in sAPPβ levels, and the y axis was represented by the -fold change in Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels. This analysis revealed a significant correlation between sAPPβ and Aβ40 (p < 0.05; Fig. 6A), but not between sAPPβ and Aβ42 (p > 0.05; Fig. 6B). The result suggested that the changes in sAPPβ and Aβ40 may share common mechanisms mediated by modulation of ATXN1.

FIGURE 6.

Alteration in sAPPβ levels significantly correlates with changes in Aβ40 levels, but not Aβ42 levels. Levels of sAPPβ were plotted together with levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 from the same samples in previous experiments. The data were represented as a percentage change by comparing the siATXN1-treated samples to control. The x axis was represented by the percentage change in sAPPβ levels, and the y axis represented by the percentage change in Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels. The line represents the linear regression for this data. There was a significant correlation between the changes in sAPPβ levels and the changes in Aβ40 levels (p < 0.05), but not Aβ42 levels (p > 0.05).

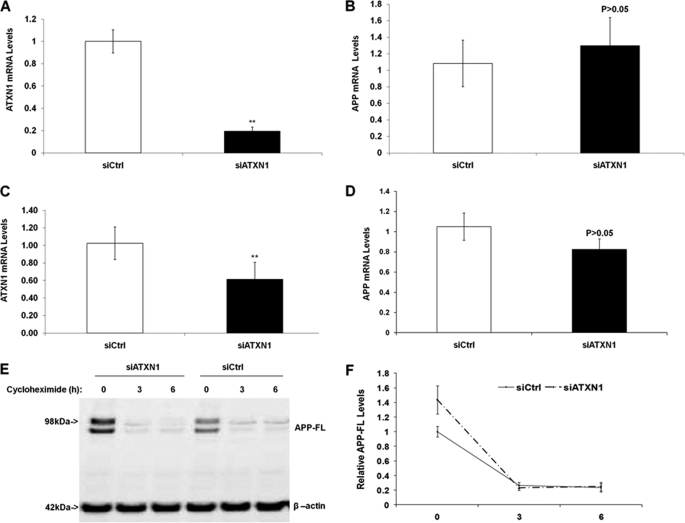

ATXN1 Knock-down Does Not Affect APP mRNA Levels or Protein Turnover Rate

It has been reported that both wild type and extended polyglutamine mutant ATXN1 proteins can function as transcriptional regulators (19, 20), therefore, we asked whether ATXN1 knock-down increased Aβ levels by affecting APP transcription. Naive H4 cells or mouse primary cortical neurons were transfected with control siRNA or ATXN1 siRNA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cell lysates were subjected to RNA extraction and quantitative PCR analysis utilizing the corresponding human or mouse ATXN1 probe to detect ATXN1 mRNA levels. β-Actin was utilized as the internal control. ATXN1 mRNA levels from ATXN1 siRNA treatment were compared with the levels from control siRNA treatment. Our data showed that ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 mRNA levels by 82.0% in naive H4 cells (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7A), but did not alter APP mRNA levels compared with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 7B). Additionally, in mouse primary cortical neurons, ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 mRNA levels by 51.6% (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7C), but did not significantly change APP mRNA levels compared with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 7D). Thus, these data suggested that the down-regulation of ATXN1 increases Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by a mechanism other than modulating APP transcription.

FIGURE 7.

Knock-down of ATXN1 does not alter APP mRNA levels or protein turnover rate. A, naive H4 cells were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection and applied to quantitative PCR analysis. ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 mRNA levels. B, APP mRNA levels in the same samples from A. ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly alter APP mRNA levels. C, mouse primary cortical neurons were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were harvested 72 h post-transfection and applied to quantitative PCR analysis. ATXN1 siRNA treatment significantly decreased ATXN1 mRNA levels. D, APP mRNA levels in the same samples from C. ATXN1 siRNA treatment did not significantly alter APP mRNA levels (p > 0.05). E, H4-APP751 cells were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA for 42 h, and then treated with 40 μg/ml of cycloheximide for a different time period (0, 3, or 6 h). Cells were harvested and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, graphic representation of data from E. There existed no significant differences in the protein levels of full-length APP at 3 and 6 h of cycloheximide treatment. n ≥ 3 for each experimental group; mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus corresponding controls.

Because we observed that knock-down of ATXN1 had a trend to increase APP protein levels in H4-APP751 cells, we asked whether it may be due to altering APP turnover rate. H4-APP751 cells were transfected with ATXN1 siRNA or control siRNA for 42 h, and then treated with 40 μg/ml of cycloheximide for a different time period (0, 3, or 6 h). Cells were harvested and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Our data showed that there existed no significant differences in the protein levels of full-length APP at 3 and 6 h of cycloheximide treatment (p > 0.05 versus controls at corresponding time point) (Fig. 7, E and F). Collectively, our data showed that ATXN1 knock-down does not affect APP mRNA levels or APP protein turnover rate.

DISCUSSION

Mounting evidence has shown that extended polyglutamine mutant ATXN1 is associated with the disease SCA1, however, little is known about its endogenous functions. Matilla and colleagues (21) have performed a study focused on assessing whether loss of function of ATXN1 affects the pathophysiology of SCA1. Interestingly, mice homozygous and heterozygous for ATXN1 (or Sca1 in the paper) null mutation were viable and fertile (consistent with our in vitro study that ATXN1 knock-down does not reveal cytotoxicity),3 and they did not display any signs of ataxia or loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Intriguingly, they found that ATXN1 was important in learning tasks mediated by the hippocampus and the cerebellum. First, these Sca1 null mice displayed neurobehavioral abnormalities and were severely impaired in the spatial version of the Morris water maze test, suggesting the presence of motor learning deficits. Second, paired-pulse facilitation was significantly decreased in Sca1 null mice of both homozygous and heterozygous genetic backgrounds, although they revealed normal long-term potentiation and post-tetanic potentiation analyses in the CA1 area of the hippocampus compared with control mice.

Although the underlying molecular mechanism behind the learning and memory loss seen with these SCA1 null mice is still unidentified, the role of ATXN1 in learning and memory is further supported by our most recent AD GWAS genetics study (9). We showed that ATXN1 may be a risk factor of late onset AD (9). Interestingly, our current in vitro functional study has found that ATXN1 loss of function potentiates APP processing and increases Aβ levels. Additionally, emerging evidence has suggested that alteration in Aβ levels may cause learning and neurobehavioral abnormalities (3, 22). Therefore, we hypothesize that the learning and memory loss in SCA1 null mice may be caused by elevated Aβ levels. A further examination on these SCA1 null mice will be required to test this hypothesis.

Although further study on SCA1 null mice is required to elucidate the underlying mechanism by which ATXN1 leads to learning and memory loss and possibly other AD pathophysiology, our recent GWAS study showed that ATXN1 is an important AD candidate gene (9). The mechanism by which the polymorphism in ATXN1 confers AD risk is still unknown. The polymorphism identified in our GWAS is located in an intron region. ATXN1 has been shown to undergo alternative splicing (10), and defects of alternative splicing can alter protein functions, and are emerging as major contributors to AD and other neurodegenerative diseases (23, 24). It is possible that the polymorphism in ATXN1 may affect the alternative splicing of ATXN1, which lead to a loss-of-function effect in the ATXN1 protein by an unknown mechanism. The loss of function of ATXN1 can potentiate β-secretase processing of APP and increases Aβ levels, ultimately leading to AD. This mechanism is different from its primary role in SCA1, which is primarily a gain of function caused by its extended polyglutamine tract (11). Additionally modulating ATXN1 levels by overexpression may be an effective AD therapeutic approach because ATXN1 cDNA overexpression leads to decreases in both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels. Due to the complex network that exists between ATXN1 and its interacting partners (11, 18, 26), the ATXN1-mediated pathogenesis in AD and SCA1 is complex and may be affected by multiple other risk components, e.g. genetic and environmental factors.

Emerging evidence indicates that neurodegenerative diseases may share common cellular and molecular pathophysiological features, e.g. intracellular aggregates and neurotoxicity. Importantly, these features are commonly caused by protein misfolding and ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system dysfunction, and are not only seen in AD and SCA1, but also in other neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington disease and Parkinson disease (27–29). Through either a gain of function (e.g. ATXN1 in SCA1, Huntingtin in Huntington disease, or other disorders characterized by expanded CAG repeats) or loss of function (e.g. ATXN1 or UBQLN1 in late onset of AD) (15), cells were challenged with unusual intracellular aggregates and encountered intracelluar toxicity. Cell death occurs if intracellular toxicity persists or worsens such that it exceeds the capacity of the intracellular protein quality control system (28–30).

Modulation of APP processing, e.g. maturation, trafficking, as well as shedding by its secretases, plays important roles in AD pathogenesis and could be used in AD therapeutic strategies (15, 31–33). There is as of yet no evidence suggesting that wild type ATXN1 may directly affect protein trafficking. But interestingly, it has been shown that overexpression of mutant ATXN1 with extended polyglutamine tracts in transgenic mice has been associated with altered membrane protein trafficking (34). We found that ATXN1 loss of function in vitro increases both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, but not the ratio of Aβ42:Aβ40, which is usually observed in mutations of familial AD γ-secretase components, e.g. PSEN1 and PSEN2 (14, 25, 35). This also suggests that ATXN1 knock-down increases Aβ levels by a mechanism other than through γ-secretase. Thus, these findings are in agreement with our conclusion that down-regulation of ATXN1 increases Aβ levels via potentiating β-secretase processing of APP. Although the underlying mechanism by which ATXN1 affects β-secretase cleavage of APP is unknown, the process may possibly be influenced by mediating BACE1 or APP trafficking in discreet subcellular locations, and thereby affecting their interaction and proteolytic activity (31).

We note that the possible pathogenesis of ATXN1 loss of function may not be only limited to increasing Aβ levels, but also related to possibly potentiating the levels of N-APP, the further cleavage product of sAPPβ. A recent paper by Nikolaev et al. (7) showed that N-APP, the 286-amino acid N-terminal fragment of APP, a proteolytic product of the β-secretase-derived secreted form of APP (sAPPβ), could bind the death receptor, DR6, and lead to neurodegeneration. Therefore, it is worth testing the hypothesis that ATXN1 loss of function increases sAPPβ levels, which may lead to an increase in the N-APP level that ultimately bind to the DR6 receptor and cause neuronal death. We have tried to detect the N-APP protein in our ATXN1 and control siRNA-treated samples, but failed to confirm the existence of N-APP, which was most probably due to low antibody specificity.

Collectively, our study shows that down-regulation of ATXN1 increases both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by potentiating β-secretase processing of APP. ATXN1 may function as a significant risk modifier of late onset AD by a mechanism of loss of function. Although identifying all the polymorphisms in ATXN1 that underlie AD pathogenesis is still required, targeting ATXN1 should be considered an important approach in developing AD therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The monoclonal antibodies targeting ATXN1 (76-3 and 76-8) were developed and obtained from the University of California, Davis/National Institutes of Health NeuroMab Facility, supported by National Institutes of Health Grant U24NS050606 and maintained by the Dept. of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, College of Biological Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616. We thank Dr. Jaehong Suh for technical assistance and Dr. Lars Bertram and Dr. Aleister J. Saunders for helpful discussion.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the NIMH, the Cure Alzheimers Fund, and the Massachusetts General Hospital Fund for Medical Discovery (FMD).

C. Zhang, A. Browne, D. Child, J. R. DiVito, J. A. Stevenson, and R. E. Tanzi, unpublished data.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- APP

- β-amyloid protein precursor

- Aβ

- amyloid β-protein

- ATXN1

- ataxin 1

- SCA1

- spinocerebellar ataxia type 1

- GWAS

- genome-wide association screen

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cummings J. L. (2004) N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 56–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002) Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertram L., Tanzi R. E. (2008) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 768–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandy S. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1121–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanzi R. E., Bertram L. (2005) Cell 120, 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C., Saunders A. J. (2007) Discov. Med. 7, 113–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolaev A., McLaughlin T., O'Leary D. D., Tessier-Lavigne M. (2009) Nature 457, 981–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Gatz M., Reynolds C. A., Fratiglioni L., Johansson B., Mortimer J. A., Berg S., Fiske A., Pedersen N. L. (2006) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 168–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram L., Lange C., Mullin K., Parkinson M., Hsiao M., Hogan M. F., Schjeide B. M., Hooli B., Divito J., Ionita I., Jiang H., Laird N., Moscarillo T., Ohlsen K. L., Elliott K., Wang X., Hu-Lince D., Ryder M., Murphy A., Wagner S. L., Blacker D., Becker K. D., Tanzi R. E. (2008) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 623–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banfi S., Servadio A., Chung M. Y., Kwiatkowski T. J., Jr., McCall A. E., Duvick L. A., Shen Y., Roth E. J., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (1994) Nat. Genet. 7, 513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7425–7429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Z., Dong Y., Maeda U., Xia W., Tanzi R. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4318–4325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Z., Romano D. M., Tanzi R. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15413–15421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C., Browne A., Kim D. Y., Tanzi R. E. (2010) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 7, 21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiltunen M., Lu A., Thomas A. V., Romano D. M., Kim M., Jones P. B., Xie Z., Kounnas M. Z., Wagner S. L., Berezovska O., Hyman B. T., Tesco G., Bertram L., Tanzi R. E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32240–33253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C., Khandelwal P. J., Chakraborty R., Cuellar T. L., Sarangi S., Patel S. A., Cosentino C. P., O'Connor M., Lee J. C., Tanzi R. E., Saunders A. J. (2007) Mol. Neurodegener. 2, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel N., Hoang D., Miller N., Ansaloni S., Huang Q., Rogers J. T., Lee J. C., Saunders A. J. (2008) Mol. Neurodegener. 3, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam Y. C., Bowman A. B., Jafar-Nejad P., Lim J., Richman R., Fryer J. D., Hyun E. D., Duvick L. A., Orr H. T., Botas J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2006) Cell 127, 1335–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goold R., Hubank M., Hunt A., Holton J., Menon R. P., Revesz T., Pandolfo M., Matilla-Dueñas A. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 2122–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolger T. A., Zhao X., Cohen T. J., Tsai C. C., Yao T. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29186–29192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matilla A., Roberson E. D., Banfi S., Morales J., Armstrong D. L., Burright E. N., Orr H. T., Sweatt J. D., Zoghbi H. Y., Matzuk M. M. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 5508–5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesné S., Koh M. T., Kotilinek L., Kayed R., Glabe C. G., Yang A., Gallagher M., Ashe K. H. (2006) Nature 440, 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Dov C., Hartmann B., Lundgren J., Valcárcel J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1229–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertram L., Hiltunen M., Parkinson M., Ingelsson M., Lange C., Ramasamy K., Mullin K., Menon R., Sampson A. J., Hsiao M. Y., Elliott K. J., Velicelebi G., Moscarillo T., Hyman B. T., Wagner S. L., Becker K. D., Blacker D., Tanzi R. E. (2005) N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 884–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Kang D. E., Xia W., Okochi M., Mori H., Selkoe D. J., Koo E. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12436–12442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuda H., Jafar-Nejad H., Patel A. J., Sun Y., Chen H. K., Rose M. F., Venken K. J., Botas J., Orr H. T., Bellen H. J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2005) Cell 122, 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings C. J., Mancini M. A., Antalffy B., DeFranco D. B., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinsztein D. C. (2006) Nature 443, 780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Vicente M., Cuervo A. M. (2007) Lancet Neurol. 6, 352–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C., Saunders A. J. (2009) Disc. Med. 8, 18–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majercak J., Ray W. J., Espeseth A., Simon A., Shi X. P., Wolffe C., Getty K., Marine S., Stec E., Ferrer M., Strulovici B., Bartz S., Gates A., Xu M., Huang Q., Ma L., Shughrue P., Burchard J., Colussi D., Pietrak B., Kahana J., Beher D., Rosahl T., Shearman M., Hazuda D., Sachs A. B., Koblan K. S., Seabrook G. R., Stone D. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17967–17972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gandy S., Zhang Y. W., Ikin A., Schmidt S. D., Bogush A., Levy E., Sheffield R., Nixon R. A., Liao F. F., Mathews P. M., Xu H., Ehrlich M. E. (2007) J. Neurochem. 102, 619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedrini S., Carter T. L., Prendergast G., Petanceska S., Ehrlich M. E., Gandy S. (2005) PLoS Med. 2, e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner P. J., Vierra-Green C. A., Clark H. B., Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (2001) Am. J. Pathol. 159, 905–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia W., Zhang J., Kholodenko D., Citron M., Podlisny M. B., Teplow D. B., Haass C., Seubert P., Koo E. H., Selkoe D. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7977–7982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]