Abstract

Fibronectin (FN) without an RGD sequence (FN-RGE), and thus lacking the principal binding site for α5β1 integrin, is deposited into the extracellular matrix of mouse embryos. Spontaneous conversion of 263NGR and/or 501NGR to iso-DGR possibly explains this enigma, i.e. ligation of iso-DGR by αvβ3 integrin may allow cells to assemble FN. Partial modification of 263NGR to DGR or iso-DGR was detected in purified plasma FN by mass spectrometry. To test functions of the conversion, one or both NGR sequences were mutated to QGR in recombinant N-terminal 70-kDa construct of FN (70K), full-length FN, or FN-RGE. The mutations did not affect the binding of soluble 70K to already adherent fibroblasts or the ability of soluble 70K to compete with non-mutant FN or FN-RGE for binding to FN assembly sites. Non-mutant FN and FN-N263Q/N501Q with both NGRs mutated to QGRs were assembled equally well by adherent fibroblasts. FN-RGE and FN-RGE-N263Q/N501Q were also assembled equally well. Although substrate-bound 70K mediated cell adhesion in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+ by a mechanism that was inhibited by cyclic RGD peptide, the peptide did not inhibit 70K binding to cell surface. Mutations of the NGR sequences had no effect on Mn2+-enhanced cell adhesion to adsorbed 70K but caused a decrease in cell adhesion to reduced and alkylated 70K. These results demonstrate that iso-DGR sequences spontaneously converted from NGR are cryptic and do not mediate the interaction of the 70K region of FN with the cell surface during FN assembly.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Extracellular Matrix, Fibronectin, Integrin, Protein Assembly, N-terminal 70K Fragment, NGR, iso-DGR

Introduction

Fibronectin (FN)3 is a 450-kDa dimer of ∼225-kDa subunits that are composed of 12 type 1 (FN1), 2 type 2 (FN2), and 15–17 type 3 (FN3) modules (1). Insoluble FN is a component of the extracellular matrix that modulates diverse processes including cell adhesion, migration, wound healing, and embryogenesis (2–4). During formation of platelet thrombi and the extracellular matrix, FN is deposited as fibrils in a process known as FN assembly (2–5).

Assembly of FN fibrils is a cell surface-mediated process (2–4). The best characterized FN-cell surface interaction is between the RGD sequence in 10FN3 of FN and integrin α5β1 (2, 6). This interaction is thought to transmit the force from the actin cytoskeleton that is necessary to unfold FN (7–10), such as to open the interaction between domains 4FN1-5FN1 and 3FN3 that masks the migration stimulation sites in the N terminus of FN (11). In vivo knock-in experiments in which the RGD sequence was replaced with an RGE sequence and in vitro experiments in which the RGD sequence was deleted, however, suggested that other regions of FN also play significant roles in the assembly process (12–15).

The N-terminal 70K region is indispensable for FN assembly (14, 16). Studies showing that this segment of FN as a proteolytic fragment or recombinant protein (70K) binds to FN-null fibroblasts (16) and that 70K, but not the integrin-binding RGD sequence in 10FN3, is exposed in plasma FN (17, 18) and supports a direct interaction between FN and the cell surface. Further, 70K serves as a dominant negative inhibitor of assembly of full-length FN by blocking FN binding to the surface of adherent fibroblasts or platelets (19, 20).

Cellular components responsible for the interactions between 70K and fibroblasts during FN assembly are not known. 70K does not contain a classic integrin-binding sequence. It does, however, contain two NGR sequences flanked by glycines in homologous loops of 5FN1 and 7FN1. In cyclic peptides and recombinant 5FN1 module, this sequence can undergo deamidation and isomerization of the asparagine to isoaspartic acid (21). The GNGRG sequences are conserved in murine, bovine, rat, amphibian, and fish FNs (22). iso-DGR-containing peptides interact with αvβ3 (21, 23). Accordingly, it was hypothesized that this interaction allows for the FN assembly observed in mouse embryos in which the RGD sequence in 10FN3 is replaced by an RGE sequence (12). Further, it was hypothesized that interaction of iso-DGR with αvβ3 is essential for the binding of 70K to the cell surface during FN assembly (12).

Here, we explore the presence of the iso-DGR sequence in FN purified from human plasma and the importance of this sequence in FN assembly. We found evidence for DGR or iso-DGR in 5FN1 in plasma FN by mass spectrometry. Studies of recombinant 70K with mutations preventing conversion of NGR sequences to iso-DGR demonstrated that the mutations caused a decrease in cell adhesion to reduced and alkylated 70K but had no impact on the binding of soluble 70K to assembly sites on adherent FN-null fibroblasts or Mn2+-dependent adhesion of fibroblasts to native 70K. Recombinant FN with mutations of both NGR sequences in 5FN1 and 7FN1 plus mutation of RGD motif in 10FN3 was able to be assembled by adherent FN-null fibroblasts, and this assembly could be inhibited by 70K with the NGR mutations. Thus, we conclude that iso-DGR sequences spontaneously converted from NGR interact with αvβ3 when FN is denatured but do not mediate the interaction between native FN and the cell surface and are not required for FN assembly, even in the absence of an intact RGD sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Vitronectin (VN), Plasma FN, and FN Proteolytic Fragments

VN was isolated from human plasma as described previously (24). Human FN was purified from an FN-rich side fraction of plasma by precipitation of contaminating fibrinogen by brief (3-min) heating at 56 °C followed by chromatography on DEAE-cellulose (25). The proteolytic 70K N-terminal fragment of plasma FN was purified after limited digestion by cathepsin D, and the 40-kDa gelatin-binding fragment (40K) was purified from a limited tryptic digest of the 70K fragment (18).

Recombinant Proteins

Recombinant FNs with N263Q/N501Q mutations and/or mutation of RGD to RGE at 10FN3, 1FN3-C, and 70K (N-9FN1) with N263Q, N501Q, or N263Q/N501Q mutations (Fig. 1) were produced using a baculovirus expression system with either High 5 cells or SF9 cells as described before (26, 27). Recombinant whole-length FN constructs contained extra domain A (AFN3) and the V89 version of the variable region but not extra domain B (BFN3). 1FN3-C had the V89 version of the variable region but did not contain AFN3 or BFN3. In experiments of binding and assembly, medium containing protein were used immediately after harvesting ∼65 h after infection. The medium was clarified by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 20 min. Western blotting was used to assess concentrations and intactness of the recombinant protein in the conditioned medium in comparison with purified plasma FN or proteolytic 70K.

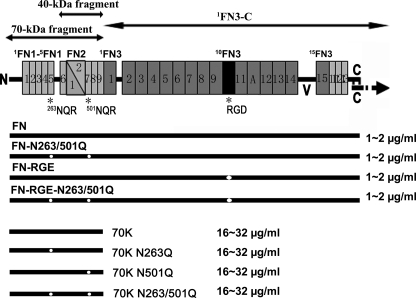

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of FN, proteolytic or recombinant FN fragments, and recombinant FN and 70K with different combinations of NGR or RGD mutations. Each subunit of FN dimer consists of 12 type 1 (thin rectangles), two type 2 (triangles), and 15 type 3 (thick rectangles) modules. The subunits are joined near the C termini by a pair of disulfide bridges. Sites of mutations are shown by white dots. Also included are the ranges of protein concentrations produced in multiple preparations as estimated by using purified plasma FN or proteolytic 70K as a standard in Western blotting.

Recombinant FN, 1FN3-C, 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q constructs were purified using a C-terminal His tag as described previously (27). To optimize solubility, proteins were dialyzed against MOPS buffer (10 mm MOPS, 300 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 1 m NaBr and stored in portions in −80 °C until used.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis of FN and FN Fragments

Mass spectrometric analysis was performed on a ThermoElectron Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) containing a linear ion trap and electrospray ionization source. The instrument was coupled with an Eksigent nano-liquid chromatography system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). A 0.3 × 50-mm PLRP-S 5-μ 300 Å C4 column from Michrom Bioresources (Auburn, CA) was used for the nano-liquid chromatography with a gradient of 0–80% acetonitrile. MS and MS/MS data were collected on tryptic fragments of reduced and alkylated 70K or 40K. Thus, proteins were reduced with 10 mm dithiothreitol for 1 h at 56 °C, cooled to 22 °C, alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark at 22 °C, and subjected to trypsinization (sequence grade modified trypsin (Promega, part number V511A, Madison, WI) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.3, with a protein:trypsin mass ratio of 20:1) for 16–20 h at 37 °C before application of 300–500 ng of protein to the NanoLC-LTQ system.

Analysis of MS and MS/MS data was performed using Xcalibur 2.0.5 and Bioworks 3.3 software (Thermo Scientific). Sequences were compared against a filtered (ΔCn ≥ 0.080; XCorr (±1, 2, 3) = 1.5, 2.00, 2.50; and number of different peptides ≥ 1) National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) human data base in BioWorks. Carboxyamidomethylation (mass shift of +57.0215) of peptides was accounted for in searches. Expected masses were calculated using the GPMAW 5.02 software (Lighthouse Data, Odense, Denmark).

Labeling of Recombinant Proteins with Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)

Proteins (70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q) were labeled FITC (F-1906, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with a slight modification. FITC was dissolved in 0.5 m carbonate buffer, pH 9.5, to a final concentration of 1.0 mg/ml. Recombinant proteins were dialyzed into 0.05 m carbonate buffer with 1 m NaBr, pH 9.5, and mixed with FITC for 1 h at room temperature. PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) were used for separation of FITC and FITC-labeled proteins.

Reduction and Alkylation of Proteins for Adhesion Assay

Proteins (FN, 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, 70K-N263Q/N501Q, FITC-70K, FITC-70K-N263Q, FITC-70K-N501Q, or FITC-70K-N263Q/N501Q) were reduced with 10 mm dithiothreitol in the presence of 3 m guanidine for 1 h at 56 °C, cooled to 22 °C, and then alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark at 22 °C. Proteins were diluted to 10 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before coating plates for adhesion assays.

Cells

FN-null fibroblastic cells from FN-null mouse embryonic stem cells were derived and handled as described previously (28, 29). β1-null GD25 and β1-expressing GD25-β1A cells were handled as described (28, 30).

Cell Adhesion Assay

Triplicate wells of polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning Costar CLS3590 or CLS3596, Lowell, MA) were incubated overnight at 4 °C in PBS as control or PBS containing 10 μg/ml FN, VN, laminin-111 (LN) (Invitrogen), 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, 70K-N263Q/N501Q, FITC-70K, FITC-70K-N263Q, FITC-70K-N501Q, FITC-70K-N263Q/N501Q, or the same proteins reduced and alkylated as above. Alternatively, triplicate wells were coated with various concentrations of VN or reduced and alkylated FITC-70K or FITC-70K-N263Q/N501Q. The plates were rinsed three times with PBS followed by a 1-h incubation at 37 °C in 1% BSA in PBS. The wells were rinsed once with PBS and incubated with 100 μl of a suspension of FN-null cells (140,000 cells/ml), GD25 cells (200,000 cells/ml), or GD25-β1A cells (200,000 cells/ml) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 0.2% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C with or without 1 mm MnCl2 and with or without linear peptide RGDS (linRGD) (Sigma), linear peptide RGES (linRGE) (Sigma), or cyclic peptide RGDfv (cycRGD) (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Wells were then rinsed three times with PBS. Attached cells were fixed with 96% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed once with water, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature. Plates were rinsed with water until the rinse was colorless, Triton (0.2% Triton for .5% Triton for Fig. 6A) was added to solubilize cell-associated dye, and the plates were read for absorbance at 595 nm using a TECAN GENios Pro plate reader (Tecan, Research Triangle Park, NC).

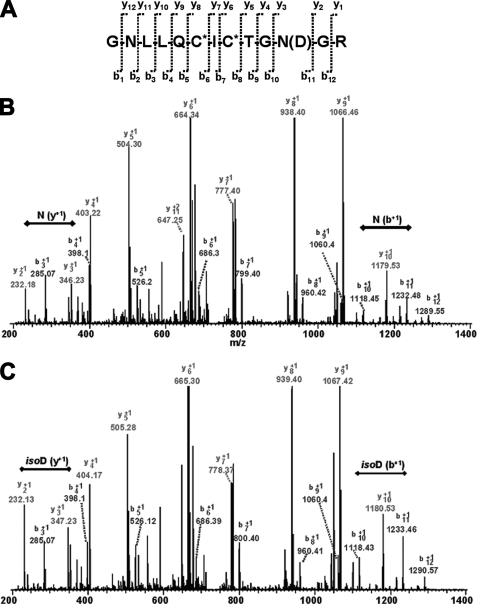

FIGURE 6.

Effects of RGD peptides in cell adhesion to 70K and in 70K binding to cell surface. A, cell adhesion assays of FN-null cells to VN, LN, 70K, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q were done with a high binding plate (CLS3590) as described under “Materials and Methods” with or without 1 mm Mn2+ and cycRGD peptide, linRGD peptide, or linRGE peptide during cell attachment. Adhesion is expressed as a fraction of the absorbance at 595 nm of wells coated with VN and without Mn2+ (1.0 corresponds to an absorbance at 595 nm of about 0.21 for FN-null cells). Error bars represent the S.E. (n = 2). B, FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C were incubated with 70K or 70K-N263Q/N501Q in conditioned medium, or a non-infected conditioned medium control, in the absence or presence of 100 μm cycRGD peptide for 1 h. Cells were fixed and stained for 70K with 4D1.7 followed by FITC-anti-mouse IgG as described in the legend for Fig. 3. The result is representative of two sets of experiments. Bar = 20 μm.

Binding of 70K to Fibroblasts and FN Assembly

Experiments with FN-null fibroblasts were done on glass coverslips as described before (27). 1FN3-C was diluted to 4 μg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4, prior to coating overnight at 4 °C of the coverslips. Alternatively, LN was diluted to 15 μg/ml in PBS prior to coating. FN-null cells were allowed to adhere for 1 h in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing once with DMEM containing 0.2% BSA. Recombinant non-mutant FN, FN-N263Q/N501Q, FN-RGE, FN-RGE-N263Q/N501Q, 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q in 400 μl of conditioned medium collected ∼65 h after infection or a non-infected conditioned medium control was mixed with 100 μl of DMEM containing 1% BSA. The FN-null cells were incubated with the mix for 3 h at 37 °C. For cells adherent to LN, cells were allowed to adhere for 2 h in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA and incubated with recombinant proteins in the presence of 1 μm lysophosphatidic acid for 3 h at 37 °C. The coverslips were washed three times with PBS, and cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and blocked by 5% BSA containing 0.3% Triton for 30 min followed by mouse 4D1.7 recognizing 1FN1-3FN1 of FN (31) for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. After washing four times with PBS, FITC-anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) was added for 1 h at room temperature. The coverslips were washed four times with PBS and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were viewed and photographed as described before (27).

In competition assays, 400 μl of recombinant non-mutant FN or FN-RGE in conditioned medium, collected ∼65 h after infection, was mixed with 100 μl of DMEM plus 1% BSA and added to culture medium of FN-null fibroblasts with or without 500 nm or 1 μm purified recombinant 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q in the presence of 50 or 100 mm NaBr and incubated for 1 h before sample processing. Those samples were stained by IST-9 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), which recognizes the extra domain A (AFN3) of the recombinant FNs. Alternatively, 400 μl of recombinant 70K or 70K-N263Q/N501Q in conditioned medium, collected ∼65 h after infection, or a non-infected conditioned medium control, was mixed with 100 μl of DMEM plus 1% BSA and added to culture medium of FN-null fibroblasts with or without 100 μm cycRGD and incubated for 1 h before sample processing. Those samples were stained by mouse 4D1.7 followed by FITC-anti-mouse IgG as described previously.

RESULTS

Search for iso-DGR Sequences in Human Plasma FN

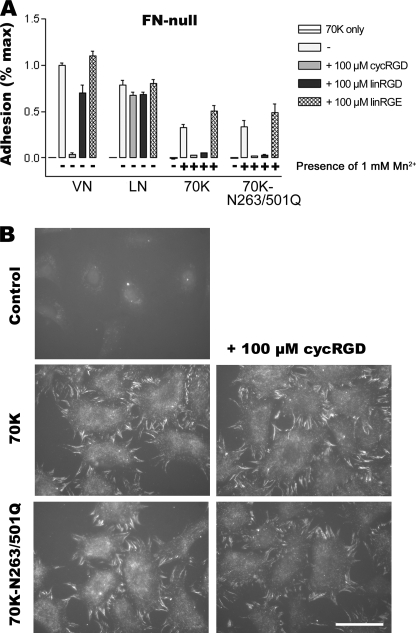

The N-terminal 70K fragment of FN contains NGR sequences in type 1 modules 5FN1 and 7FN1. These sequences are in β-bends linking the D and E strands of the CDE β-sheets of the modules (32) and flanked by glycines. Because NGR sequences flanked by glycines in cyclic peptides (12, 33) or bacterially expressed and heated 5FN1 modules (12) undergo spontaneous deamidation and isomerization to iso-DGR sequences that bind to αvβ3 integrins (12, 33, 34), we searched for evidence of conversion of the sequences in tryptic fragments of purified plasma FN that included 5FN1 and 7FN1. 253GNLLQCICTGNGR265 from 5FN1 was identified by nano-liquid chromatography LTQ-MS/MS in a complete tryptic digest of reduced and alkylated 70K N terminus from plasma FN (Table 1 and Fig. 2), both in its unmodified form and with a 1-Da mass increase, compatible with conversion of an asparagine to isoaspartic acid or aspartic acid (Table 1). MS/MS sequencing demonstrated that the 1-Da shift occurs at residue 263 (Fig. 2). Finding a mixture of peptides with modified and unmodified Asn263 is in accordance with estimates of iso-D content of a 27K fragment of FN (that includes 5FN1) using an assay based on protein isoaspartyl carboxyl methyltransferase (21).

TABLE 1.

NGR and iso-DGR/DGR sequences detected by LTQ-MS/MS analysis of tryptic fragments of reduced and alkylated proteolytic N-terminal FN fragments

p, plasma; r, recombinant. *, alkylation of cysteine; ND, peptide not detected. Asn263 and Asn501 are underlined.

| Attribute of peptide | Tryptic peptide |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

253GNLLQC*IC*TGNGR |

494C*TC*VGNGRGEWTC*IAYSQLR |

|||

| Unmodified | Modified | Unmodified | Modified | |

| Expected mass | 1462.69 | 1463.67 | 2388.69 | 2389.68 |

| Found in p70K | 1462.08a | 1463.10a | 2388.06 | ND |

| Found in p40K | ND | ND | 2388.06 | ND |

| Found in r70K | 1462.64 | ND | 2388.90 | ND |

a MS/MS shown in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 2.

LTQ-MS/MS fragmentation sequencing (A) demonstrating both unmodified 263NGR (B) and modified 263iso-DGR or 263DGR (C) from proteolytic 70-kDa N terminus isolated from plasma FN. The b+1 and y+1 are labeled on B and C. The double-headed line indicates the b+1 or y+1 ion gap corresponding to residue 263.

We identified the tryptic peptide containing Asn501 in 7FN1 in the proteolytic 70K fragment but could not find the same peptide with the 1-Da shift in mass (Table 1). When the 40K proteolytic plasma FN fragment was used to limit the ions present for MS analysis, again only the peptide containing Asn501 was detected (Table 1). Multiple analyses of recombinant 70K revealed 5FN1 and 7FN1 peptides only in the unmodified forms (Table 1).

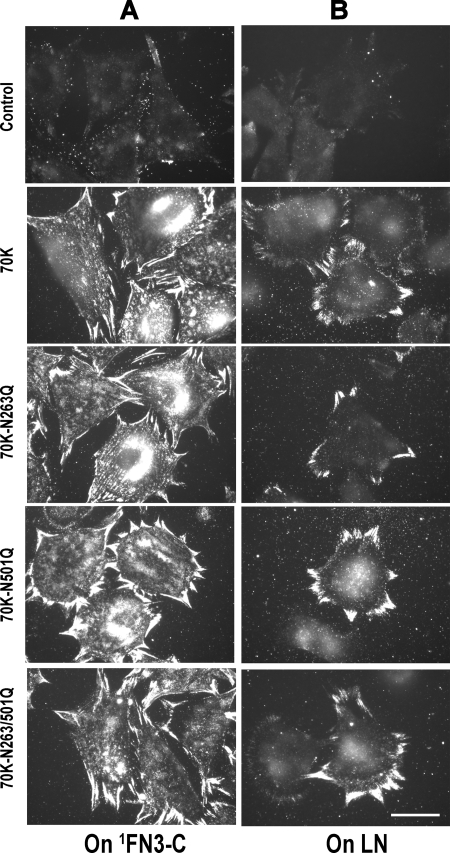

NGR Sequences Do Not Mediate the Binding of 70K to FN-null Fibroblasts

To determine whether NGR sequences mediate the interaction between the N-terminal 70K region of FN and assembly sites on adherent FN-null fibroblasts, we changed NGR to QGR, as is found at the homologous position of 8FN1, and compared recombinant 70K with 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q in which one, the other, or both of the NGR sequences cannot be converted to iso-DGR. We first studied the binding of 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q to adherent FN-null fibroblasts. Wild type 70K and 70K mutants (70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or N263Q/N501Q) bound equally well to FN-null fibroblasts adherent to surface-adsorbed substrate 1FN3-C (27) or LN (28) that support cell adhesion and assembly of FN (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that NGR sequences are not required for the binding of 70K to FN-null fibroblasts.

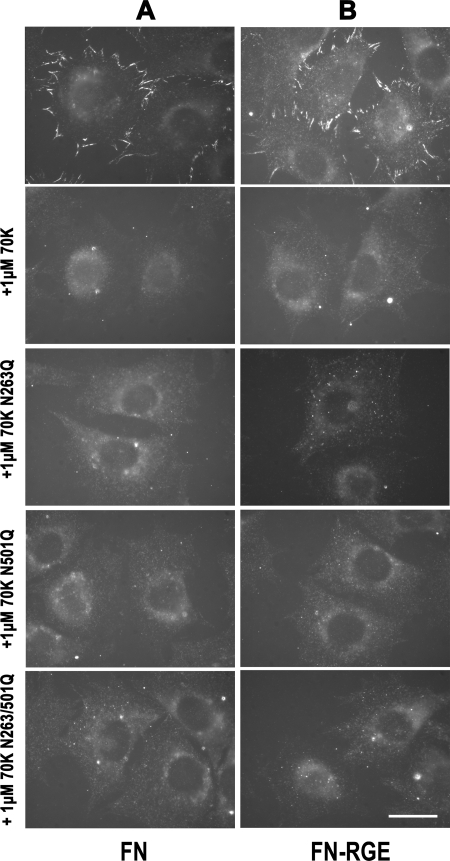

FIGURE 3.

NGR sequences do not affect 70K binding to adherent FN-null fibroblasts. FN-null fibroblasts were allowed to adhere to coverslips coated with 1FN3-C (4 μg/ml) (A) or LN (15 μg/ml) (B) for 1 (A) or 2 (B) h and then incubated with 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q for 3 h. Cells were fixed and stained for 70K with 4D1.7 followed by FITC anti-mouse IgG. Bound protein was detected by fluorescence microscopy. The four proteins were added at a similar level (∼20 μg/ml) as determined by Western blotting. The result is representative of three sets of experiments. Bar = 20 μm.

70K with or without Mutations in NGR Sequences Competes Equally Well for Cell Surface Binding of FN

70K competes with FN for binding to the cell surface (19). When we examined the ability of 70K with NGR mutations to compete with FN for binding to the cell surface, as with non-mutant recombinant 70K, 70K containing the N263Q, N501Q, or N263Q/N501Q mutation competed for FN binding to FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C when added at concentrations of 500 nm (result not shown) or 1 μm (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

NGR sequences do not affect the ability of 70K to compete with FN or FN-RGE for binding to FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C. FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C were incubated with non-mutant FN (A) or FN-RGE (B) in the absence or presence of 1 μm of the following forms of recombinant 70K: wild type 70K, 70K-N263Q, 70K-N501Q, or 70K-N263Q/N501Q. All incubations were for 1 h and done in the presence of 100 mm NaBr, which was present in the 70K preparations to enhance solubility. Cells were fixed and stained with IST9 to AFN3, which was present in the recombinant FN or FN-RGE, but not in the substrate 1FN3-C, and observed under the fluorescence microscope. The result is representative of two sets of experiments. Bar = 20 μm.

NGR Sequences Are Not Required for FN Assembly by FN-null Fibroblasts

To determine whether NGR sequences are required for FN assembly, we created recombinant FN containing the N263Q/N501Q double mutation in FN with an intact RGD sequence (FN-N263Q/N501Q) using a baculovirus system for production of secreted proteins. Non-mutant or mutant FN was present at similar concentrations in conditioned medium of infected cells and used without purification to minimize manipulations of the FNs that might alter the proteins. FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C or LN assembled both wild type FN and FN-N263Q/N501Q (Fig. 5, A and B). These results indicate that, as with the binding of 70K to assembly sites, NGR sequences are not required for assembly of FN.

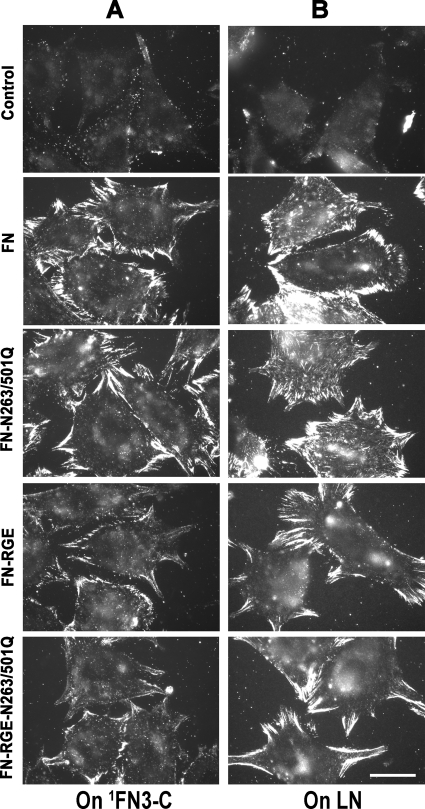

FIGURE 5.

NGR sequences do not affect FN binding to adherent FN-null fibroblasts. FN-null fibroblasts adherent to 1FN3-C (A) or LN (B), as described in the legend for Fig. 4, were incubated for 3 h with recombinant non-mutant FN, FN-RGE, FN-N263Q/N501Q, or FN-N263Q/N501Q-RGE. Cells were fixed and stained for full-length FN with 4D1.7, detected by fluorescence microscopy. The four proteins were present in a similar level (∼1 μg/ml) as determined by Western blotting. The result is representative of three sets of experiments. Bar = 20 μm.

NGR Sequences Are Not Required for Assembly of FN-RGE by FN-null Fibroblasts

A mouse in which the integrin-binding RGD sequence of FN in 10FN3 was replaced with an RGE sequence is able to assemble FN in a manner that was hypothesized to depend on the interaction of αvβ3 with iso-DGR sequences in the 70K region of FN (12). To test the role of the NGR sequences in assembly of FN containing an RGE sequence, we compared the ability of FN-null fibroblasts to assemble FN-RGE and FN-RGE-N263Q/N501Q. Consistent with published results (12, 13, 15), FN-RGE was assembled into fibrillar arrays (Fig. 5, A and B). These arrays were not as intense as immunoarrays formed with wild type FN and were shorter and located more at the periphery of the cells. FN-RGE-N263Q/N501Q was similarly assembled into fibrils by FN-null fibroblasts (Fig. 5, A and B). We also looked at the inhibition of FN-RGE binding by the 70K NGR mutants. 70K and 70K harboring N263Q, N501Q, or N263Q/N501Q mutations all competed for the binding of FN-RGE (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that NGR sequences are not involved in assembly of FN-RGE.

NGR Sequences Do Not Mediate Cell Adhesion to 70K in the Presence of 1 mm MnCl2

Fibroblasts pretreated with cycloheximide attach to tissue culture plates coated with baculovirally expressed 70K after a 5-h incubation at 37 °C (35). Further evidence for an interaction between integrins and 70K came from studies showing that adhesion of endothelial-like cells to VN is inhibited by heated recombinant 5FN1 (21) and that biotinylated αvβ3 integrin binds to surface-adsorbed 70K when Mn2+ is present (12). We carried out 1-h assays of cell adhesion of FN-null cells to recombinant 70K coated at a concentration of 10 μg/ml on high binding plates. As compared with adherence to VN or LN, cells adhered minimally to recombinant 70K in the absence of Mn2+ (Fig. 6A). There was a significant increase in cell adhesion to surface-adsorbed 70K in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+, but no differences were observed between native 70K and the double mutant (70K-N263Q/N501Q) (Fig. 6A). The same patterns of adhesion to adsorbed wild type or mutated 70K were observed with tissue culture plates (results not shown). Both cycRGD and linRGD blocked cell adhesion in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+ (Fig. 6A), suggesting that FN-null cells adhere to 70K through activated αvβ3 integrins (36). Next we examined whether 70K binding to cell surfaces of already adherent cells was blocked by the same concentration of cycRGD peptide, which blocked cell adhesion to adsorbed 70K, and found that 70K binding to the cell surface was not affected by 100 μm cycRGD peptide (Fig. 6B).

Mutations of the NGR Sequences Cause Decrease in Cell Adhesion to Reduced and Alkylated 70K

Because a prior study demonstrated that the RGD sequence in thrombospondin-1 becomes available from integrin-dependent cell adhesion upon reduction (37), we studied the baculovirally expressed 70K after reduction of cysteines and alkylation of resulting free sulfhydryls. We used FN-null cells, β1-null GD25 cells for which αvβ3 is the major integrin (30), and GD25-β1A cells in which β1 integrins had been restored with concomitant loss of β3 integrins (38, 39). Such treatment increased adhesion in the absence of Mn2+, most markedly for GD25 cells (Fig. 7A). In other experiments, we found that FITC labeling of native 70K resulted in a protein that mediated some adhesion of GD25 cells (Fig. 7A). The combination of FITC labeling and reduction and alkylation resulted in the most adhesive form of 70K, with the greatest adhesion by GD25 cells (Fig. 7A). All 70K constructs were studied without and with FITC labeling and without and with reduction and alkylation (Fig. 7A). As with non-mutant 70K, β1-null GD25 cells, GD25-β1A cells, and FN-null fibroblasts adhered best to protein that had been reduced and alkylated and labeled with FITC (Fig. 7A). For all cell types, adhesion to reduced and alkylated double mutant (70K-N263Q/N501Q) was decreased as compared with adhesion to single mutant (70K-N263Q or 70K-N501Q) or non-mutant 70K. These differences were significant for adhesion of the three cell types to proteins that had been FITC-labeled and reduced and alkylated and for GD25 cell adhesion to reduced and alkylated proteins that had not been labeled with FITC (Fig. 7A). The same patterns of adhesion to adsorbed native or modified 70K were observed with tissue culture plates (results not shown).

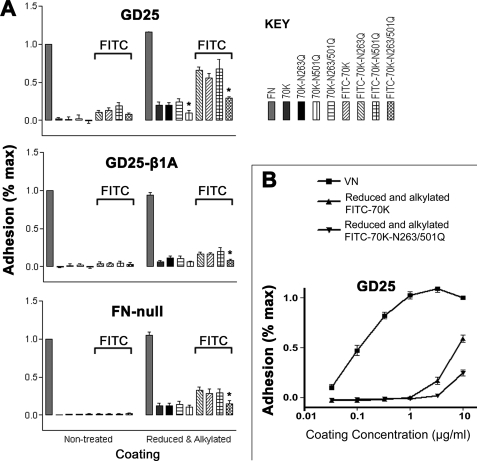

FIGURE 7.

Adhesion of FN-null, GD25, or GD25-β1A cells to FN, VN, and different 70K constructs. A, adhesion to different 70K constructs. Cell adhesion assays of FN-null, GD25, or GD25-β1A cells were done with a high binding plate (CLS3590) as described under “Materials and Methods.” Adhesion is expressed as a fraction of the absorbance at 595 nm of wells coated with non-modified FN (1.0 corresponds to an absorbance at 595 nm of about 0.10 for GD25 cells, 0.10 for GD25-β1A cells, and 0.30 for FN-null cells). Error bars represent the S.E. of three separate experiments in which each condition was tested in triplicate. Parallel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays demonstrated that similar amounts of 70K had adsorbed to all wells. *, p < 0.05 as compared with non-mutant 70K. B, adhesion of GD25 cells to VN, reduced and alkylated FITC-70K, or reduced and alkylated FITC-70K-N263Q/N501Q. Cell adhesion assays of GD25 cells were done with proteins coated in serial dilutions of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 μg/ml. Adhesion is expressed as a fraction of the absorbance at 595 nm for VN at 10 μg/ml (corresponding to about 0.13). Error bars represent the S.E. (n = 3).

When reduced and alkylated FITC-70K or VN was adsorbed from solutions at various concentrations, reduced and alkylated FITC-70K at a given coating concentration was about 50-fold less effective than VN in mediating adhesion of GD25 cells (Fig. 7B). Although there are several other explanations for this difference, e.g. more adsorption of VN than of 70K at a given coating concentration or adsorption of a larger fraction of VN in a conformation that is active in adhesion, these results raise the possibility that only a minor fraction, ∼2%, of reduced and alkylated FITC-70K is capable of mediating cell adhesion. Therefore, if iso-DGR is responsible for adhesion of αvβ3-expressing GD25 cells to reduced and alkylated FITC-70K, conversion of 263NGR or 501NGR to iso-DGR may be of the order of ∼1% and below the limits of detection by our mass spectrometric protocol.

DISCUSSION

For FN assembly, FN must contain the N-terminal 70K region (14, 19). The importance of 70K in FN assembly is most often considered in relation to its role in mediating FN-FN interactions (40–43). However, for FN-FN interaction sites to become available, compact soluble FN needs to bind to a receptor on the surface of cells and unfold. This process must be highly regulated to prevent aberrant FN assembly in places where it would be deleterious, such as on circulating blood cells. Two hypotheses have been proposed to explain the initial interaction between FN and the cell surface; either 70K interacts with a cell surface receptor (16) or the RGD sequence in 10FN3 interacts with integrins (4, 44). In either case, the initial interaction leads to unfolding of FN followed by FN-FN interactions and the formation of fibrils. Regardless of which event initiates FN assembly, the fact that 70K alone binds to FN-null fibroblasts or platelets adherent to ligands supportive of assembly, including LN, suggests that there are receptors for 70K on the surfaces of fibroblasts or platelets (16, 20).

FN assembly in the anterior segments of mouse embryos homozygous for the FN-RGE knock-in, which have a severely shortened posterior trunk, led to a hypothesis about the initial interaction of FN with cells that combines elements of the hypotheses described above. The discoveries that asparagines within GNGRG sequences undergo spontaneous deamidation and isomerization (21) and iso-DGR-containing peptides interact directly with αvβ3 (12) suggested that αvβ3 may interact with 70K. Molecular dynamic modeling of cyclic NGR peptide derivatives interacting with αvβ3 suggested that RGD-containing and iso-DGR-containing, but not DGR- or NGR-containing peptides, fit well into the ligand-binding site of αvβ3 (33). In vitro studies showed that 800 μm NGR cyclic peptide blocked assembly of FN-RGE, but not wild type FN, with a 14-h incubation (12). Thus, when integrin binding in 10FN3 is prevented, integrins may bind to 70K so that FN assembly proceeds.

Consistent with the hypothesis, we obtained direct evidence of partial spontaneous conversion of 263NGR to DGR or iso-DGR in FN by mass spectrometry of 70K purified from plasma FN. We found no evidence for the modification of Asn501 in plasma FN by mass spectrometry nor evidence of modifications of either Asn263 or Asn501 in recombinant 70K. However, mass spectrometry as performed here was not quantitative and had unknown detection limits for the modified peptides.

Cell adhesion studies in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+ showed that when activated by Mn2+, cells adhered equally well to 70K and 70K-N263Q/N501Q, and such cell adhesion was blocked by cycRGD peptide that inhibits αvβ3. However, the cycRGD peptide did not inhibit 70K binding to cell surfaces of already adherent cells at the same concentration it blocked cell adhesion to adherent 70K. The need for Mn2+ and inhibition by the cycRGD peptide indicate that recognition of adhesive sites in substrate-bound folded 70K is by activated αvβ3. Such recognition, however, does not require intact NGR sequences. Further, the lack of need for Mn2+ or inhibition by cycRGD peptide indicates that the binding of soluble 70K to adherent fibroblasts does not require αvβ3.

Adhesion to FITC-labeled reduced and alkylated 70K constructs did not require Mn2+. Differences between wild type and mutant 70K indicated that the iso-DGR sequences are major determinants of adhesion to such denatured 70K. The enhancements due to reduction, alkylation, and FITC labeling suggest that the iso-DGR sequences are largely cryptic in native 70K. Further, because the decrease in cell adhesion caused by Asn-to-Gln mutations was most marked for GD25 cells expressing αvβ3 and not α5β1, the results support the proposal that αvβ3 binds iso-DGR (12, 21). Based on the coating response curves (Fig. 7B), the double mutant was 200-fold less effective than VN and 4-fold less effective than 70K with intact NGR sequences (Fig. 7B). Nevertheless, the results are compatible with the conclusion that minor modification of NGR to iso-DGR in FN results in a protein with the potential to interact with αvβ3 integrin and thus are consistent with recent published results (12, 21, 34).

The difference in detection of modified residue Asn263 between 70K from plasma FN and recombinant 70K is presumably due to the histories of the proteins. 70K was generated from plasma FN that had been stored at −80 °C for more than 3 years after undergoing a 5-day purification protocol mostly at 22 or 4 °C but with heating to 56 °C for 3 min (25). Generation and purification of 70K took an additional 5 days at 22 or 4 °C, and then this protein was also stored at −80 °C. Recombinant 70K, in contrast, was purified by affinity chromatography of conditioned medium over 3 days at 22 or 4 °C and stored frozen only for months. According to this logic, FN deposited in the extracellular matrix would have the potential to generate binding sites for αvβ3 over time, especially if there was concomitant isomerization of disulfides to release the iso-DGRs from their non-adhesive cryptic conformations. Long lived FN in the extracellular matrix, therefore, may have a significant content of active iso-DGR sequences.

In accordance with previous studies (12), we found that FN-RGE was assembled by FN-null cells, albeit less efficiently than FN. The decrement in assembly and altered distribution support the model that FN binds by its N-terminal 70K region to the periphery of the cell, becomes tethered to α5β1 integrins, and is extended to form fibrils via movements of integrins (45). Although we saw a decrease in FN-RGE assembly as compared with FN assembly, there was no further decrease when NGR sequences in 5FN1 and 7FN1 of FN-RGE were replaced with QGR sequences. Likewise, assembly of FN or FN-RGE was blocked by either 70K or 70K NGR mutants.

Despite the elaboration of an FN matrix, FN-RGE homozygous mouse embryos die at embryonic day 10 with multiple abnormalities including shortened posterior trunk without somites and severe vascular effects similar to α5 integrin-deficient mice (12). We can think of at least two possibilities for the defects. One is that the FN-RGE matrix develops normally in mutant embryos but does not support interaction between integrin α5β1 and FN, preventing adhesive and migration events critical for angiogenesis. Another possibility is based on the finding that FN-RGE arrays are shorter and less intense than wild type FN arrays and located more at the periphery of cells (Fig. 5). The FN-RGE matrix may be similarly different in vivo and therefore lack ultrastructural features and temporal sequence of deposition that are supportive of deposition of other critical matrix components, such as fibrillin (46, 47), collagen (48, 49), thromspondin-1 (48), or fibulin (50).

The failure to demonstrate participation of sequence motifs specific for 5FN1 and 7FN1 in the binding of the 70K construct or FN-RGE to assembly sites is compatible with the observation that individual deletion of 2FN1, 3FN1, 4FN1, or 5FN1 from 70K constructs causes decreased binding of the constructs to assembly sites of fibroblasts (51). This observation suggests that multiple FN1 modules serve the same function or, alternatively, participate as a unit in the binding of FN to cells. One possibility, suggested by the effect of the Mn2+, is that β1 and β3 integrins become activated and bind aspartate residues in multiple type I modules. Deletion of 2FN1, 3FN1, 4FN1, or 5FN1 from the 70K construct also causes decreased 70K binding to Staphylococcus aureus (51). A series of studies by Potts, Campbell, Höök, and their colleagues (32, 52–55) has demonstrated that high affinity binding of peptides from FN-binding proteins of S. aureus and other bacteria is accomplished by the so-called β-zipper mechanism in which the otherwise unstructured peptides form a fourth strand of the major CDE β-sheets of contiguous FN1 modules. Although β-strand addition to β-sheets has been observed with a number of proteins, the β-zipper is unique in that the same extended bacterial sequence interacts with the E strands of multiple consecutive FN1 modules (32, 54). One such FN-binding peptide from Streptococcus pyogenes binds to FN in a way that blocks FN assembly and exposes the RGD-containing 10FN3 module of FN (18, 56). Another hypothesis, therefore, is that certain cell surface proteins of adherent fibroblasts bind to the N-terminal region of FN in a similar way to the binding of FN-binding bacterial proteins and thus initiate assembly.

Acknowledgments

Mass spectrometric experiments were performed at the University of Wisconsin – Madison Human Proteomics Program facility, which is supported by the Wisconsin Partnership Fund for a Healthy Future. We thank Dr. Ying Ge for help with mass spectrometry and thank Laura K. Eder for help with some cell adhesion assays.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL021644 (to D. F. M.) and National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32-HL007899 (to L. M. M. and B. R. H.).

- FN

- fibronectin

- 70K

- N-terminal 70-kDa FN fragment or construct

- 40K

- 40-kDa gelatin-binding fragment

- LN

- laminin

- VN

- vitronectin

- LTQ

- linear trap quadrupole

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

- tandem mass spectrometry

- lin

- linear peptide

- cyc

- cyclic peptide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pankov R., Yamada K. M. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 3861–3863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leiss M., Beckmann K., Girós A., Costell M., Fässler R. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 502–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakonakis I., Campbell I. D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao Y., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2005) Matrix Biol 24, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho J., Mosher D. F. (2006) J. Thromb. Haemost 4, 1461–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hynes R. O. (1992) Cell 69, 11–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pankov R., Cukierman E., Katz B. Z., Matsumoto K., Lin D. C., Lin S., Hahn C., Yamada K. M. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 1075–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohashi T., Kiehart D. P., Erickson H. P. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 1221–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamir E., Katz M., Posen Y., Erez N., Yamada K. M., Katz B. Z., Lin S., Lin D. C., Bershadsky A., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiger B., Bershadsky A., Pankov R., Yamada K. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 793–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vakonakis I., Staunton D., Ellis I. R., Sarkies P., Flanagan A., Schor A. M., Schor S. L., Campbell I. D. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15668–15675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi S., Leiss M., Moser M., Ohashi T., Kitao T., Heckmann D., Pfeifer A., Kessler H., Takagi J., Erickson H. P., Fässler R. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 178, 167–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sechler J. L., Cumiskey A. M., Gazzola D. M., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 1491–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarzbauer J. E. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 113, 1463–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sottile J., Hocking D. C., Langenbach K. J. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 4287–4299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomasini-Johansson B. R., Annis D. S., Mosher D. F. (2006) Matrix Biol. 25, 282–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ugarova T. P., Zamarron C., Veklich Y., Bowditch R. D., Ginsberg M. H., Weisel J. W., Plow E. F. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 4457–4466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ensenberger M. G., Annis D. S., Mosher D. F. (2004) Biophys. Chem. 112, 201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeown-Longo P. J., Mosher D. F. (1985) J. Cell Biol. 100, 364–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho J., Mosher D. F. (2006) J. Thromb. Haemost 4, 943–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curnis F., Longhi R., Crippa L., Cattaneo A., Dondossola E., Bachi A., Corti A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36466–36476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Matteo P., Curnis F., Longhi R., Colombo G., Sacchi A., Crippa L., Protti M. P., Ponzoni M., Toma S., Corti A. (2006) Mol. Immunol. 43, 1509–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curnis F., Sacchi A., Gasparri A., Longhi R., Bachi A., Doglioni C., Bordignon C., Traversari C., Rizzardi G. P., Corti A. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 7073–7082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bittorf S. V., Williams E. C., Mosher D. F. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 24838–24846 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosher D. F., Johnson R. B. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 6595–6601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosher D. F., Huwiler K. G., Misenheimer T. M., Annis D. S. (2002) Methods Cell Biol. 69, 69–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J., Bae E., Zhang Q., Annis D. S., Erickson H. P., Mosher D. F. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bae E., Sakai T., Mosher D. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35749–35759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saoncella S., Echtermeyer F., Denhez F., Nowlen J. K., Mosher D. F., Robinson S. D., Hynes R. O., Goetinck P. F. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2805–2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wennerberg K., Lohikangas L., Gullberg D., Pfaff M., Johansson S., Fässler R. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 132, 227–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho J., Mosher D. F. (2006) Blood 107, 3555–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bingham R. J., Rudiño-Piñera E., Meenan N. A., Schwarz-Linek U., Turkenburg J. P., Höök M., Garman E. F., Potts J. R. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12254–12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitaleri A., Mari S., Curnis F., Traversari C., Longhi R., Bordignon C., Corti A., Rizzardi G. P., Musco G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19757–19768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corti A., Curnis F., Arap W., Pasqualini R. (2008) Blood 112, 2628–2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hocking D. C., Sottile J., McKeown-Longo P. J. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 241–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaff M., Tangemann K., Müller B., Gurrath M., Müller G., Kessler H., Timpl R., Engel J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20233–20238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun X., Mosher D. F. (1991) J. Clin. Invest. 87, 171–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Retta S. F., Cassarà G., D'Amato M., Alessandro R., Pellegrino M., Degani S., De Leo G., Silengo L., Tarone G. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3126–3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gimond C., van Der Flier A., van Delft S., Brakebusch C., Kuikman I., Collard J. G., Fässler R., Sonnenberg A. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 1325–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguirre K. M., McCormick R. J., Schwarzbauer J. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27863–27868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bultmann H., Santas A. J., Peters D. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2601–2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hocking D. C., Sottile J., McKeown-Longo P. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19183–19187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwarzbauer J. E., Sechler J. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 622–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wierzbicka-Patynowski I., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 3269–3276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz B. Z., Zamir E., Bershadsky A., Kam Z., Yamada K. M., Geiger B. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 1047–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabatier L., Chen D., Fagotto-Kaufmann C., Hubmacher D., McKee M. D., Annis D. S., Mosher D. F., Reinhardt D. P. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 846–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kinsey R., Williamson M. R., Chaudhry S., Mellody K. T., McGovern A., Takahashi S., Shuttleworth C. A., Kielty C. M. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 2696–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sottile J., Hocking D. C. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3546–3559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Velling T., Risteli J., Wennerberg K., Mosher D. F., Johansson S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37377–37381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Godyna S., Mann D. M., Argraves W. S. (1995) Matrix Biol. 14, 467–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sottile J., Schwarzbauer J., Selegue J., Mosher D. F. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 12840–12843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J. H., Singvall J., Schwarz-Linek U., Johnson B. J., Potts J. R., Höök M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41706–41714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwarz-Linek U., Werner J. M., Pickford A. R., Gurusiddappa S., Kim J. H., Pilka E. S., Briggs J. A., Gough T. S., Höök M., Campbell I. D., Potts J. R. (2003) Nature 423, 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meenan N. A., Visai L., Valtulina V., Schwarz-Linek U., Norris N. C., Gurusiddappa S., Höök M., Speziale P., Potts J. R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25893–25902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raibaud S., Schwarz-Linek U., Kim J. H., Jenkins H. T., Baines E. R., Gurusiddappa S., Höök M., Potts J. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18803–18809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomasini-Johansson B. R., Kaufman N. R., Ensenberger M. G., Ozeri V., Hanski E., Mosher D. F. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23430–23439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]