Abstract

Yeast Suv3p is a member of the DEXH/D box family of RNA helicases and is a critical component of the mitochondrial degradosome, which also includes a 3′ → 5′ exonuclease, Dss1p. Defects in the degradosome result in accumulation of aberrant transcripts, unprocessed transcripts, and excised group I introns. In addition, defects in SUV3 result in decreased splicing of the aI5β and bI3 group I introns. Whereas a role for Suv3p in RNA degradation is well established, the function of Suv3p in splicing of group I introns has remained elusive. It has been particularly challenging to determine if Suv3p effects group I intron splicing through RNA degradation as part of the degradosome, or has a direct role in splicing as a chaperone, because nearly all perturbations of SUV3 or DSS1 result in loss of the mitochondrial genome. Here we utilized the suv3-1 allele, which is defective in RNA metabolism and yet maintains a stable mitochondrial genome, to investigate the role of Suv3p in splicing of the aI5β group I intron. We provide genetic evidence that Mrs1p is a limiting cofactor for aI5β splicing, and this evidence also suggests that Suv3p activity is required to recycle the excised aI5β ribonucleoprotein. We also show that Suv3p acts indirectly as a component of the degradosome to promote aI5β splicing. We present a model whereby defects in Suv3p result in accumulation of stable, excised group I intron ribonucleoproteins, which result in sequestration of Mrs1p, and a concomitant reduction in splicing of aI5β.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Ribozyme, RNA Helicase, RNA Turnover, Yeast, Group I Intron, MRS1, SUV3, aI5

Introduction

Mitochondrial gene expression is largely controlled by post-transcriptional mechanisms because of the relatively simple nature of mitochondrial transcription (1–5). One critical control point is RNA degradation, which is involved in the extensive processing required of mitochondrial transcripts (6, 7). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, intergenic regions are removed from polycistronic transcripts and in the case of two mRNAs, encoding the cytochrome oxidase I subunit (COX1)2 and apocytochrome b subunit (COB), group I and group II catalytic introns are also removed. Splicing of these introns requires trans-acting factors to facilitate the RNA-catalyzed intron excision and ligation of flanking exons (8).

Rapid turnover of excised group I introns is essential for mitochondrial gene expression because these RNAs act as endonucleases that cleave their parent, processed RNAs at the site of exon ligation (e.g. exon reopening reactions), which decreases expression (9). Degradation of excised group I introns is carried out by a two-protein complex called the mitochondrial degradosome or mtEXO (10, 11). The mitochondrial degradosome includes Dss1p, a 3′ → 5′ single-stranded exonuclease, and Suv3p, a DEXH/D protein, one of the largest family of proteins that are involved in RNA metabolism (11–13). Indeed, some members show ATP-dependent unwinding of RNA helices. Suv3p is a member of the SKI2 subfamily, individuals of which are thought to couple ATP binding and hydrolysis cycles with translocation along an RNA single strand and disruption of any base-paired residues it encounters during its trek (14, 15).

Genetic analyses in yeast have yielded insights into the range of mitochondrial degradosome functions. In this regard, disruption of either gene results in a variety of 3′- and 5′-end RNA processing defects as well as increased RNA stability, including excised group I introns (16, 17). Thus the degradosome appears to play a significant role in RNA turnover and processing. Indeed, the purified degradosome functions in a stepwise fashion in the presence of a partially duplexed RNA: first, the duplex is made single stranded in an NTP- and Suv3p-dependent step followed by degradation (11).

These studies have also revealed an additional function for the SUV3 gene. In this regard, a strain containing a mis-sense mutation in SUV3 (suv3-1) showed defects in 3′ processing of mitochondrial mRNAs and increased stability of excised group I introns (9, 18, 19). In addition, inefficient splicing of aI5β and bI3, which are group I introns of COX1 and COB, respectively, was also observed. Whereas the increased stability of excised group I introns is consistent with the Suv3p protein acting as part of the degradosome, it is not clear how Suv3p may be involved in group I intron splicing.

The aI5β intron has many unique characteristics. Whereas most mitochondrial introns require one or two protein cofactors, processing of the aI5β intron requires at least five different proteins, including Mrs1p, Pet54p, Mss116p, Mss18p, and Suv3p (19–24). The reason for this unusual number of required cofactors is not clear but may lie in the fact that two large insertions disrupt its catalytic core and place its natural 3′ splice site 1,171 bases away from the core (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the aI5β intron does not contain peripheral structures known to stabilize the conserved catalytic core conformation (25, 26). Using a reconstituted in vitro system, we have shown that one of the proteins, Mrs1p, binds to the intron and facilitates the first step in splicing, while the efficiency of the exon ligation step is poor (27). Two other proteins, Pet54p and the DEXH/D protein Mss116p, can separately increase the efficiency of exon ligation in the presence of Mrs1p, although the efficiency only approaches ∼30% in vitro (27, 28).

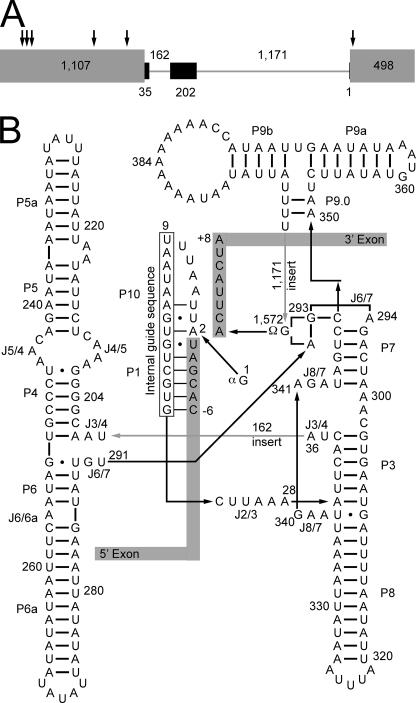

FIGURE 1.

Conserved structure of the aI5β group I intron is interrupted by two large inserts. A, COX1 pre-mRNA. All UTRs and introns, except aI5β, have been excluded for clarity. Gray rectangles represent COX1 exons, arrows show the exon junctions for the spliced out introns, black rectangles represent the conserved group I intron structure of aI5β, and inserts that disrupt the conserved structure are represented by gray lines. Length in bases for the exons, intron, and inserts are shown within, below, and above, respectively. B, predicted secondary structure. Boxed regions represent the exons, and the intronic paired regions (P) and junctions between paired regions (J) are indicated. Arrows point in the 5′ to 3′ direction to indicate linear connectivities of the nucleic acid strand. Numbering starts with the exogenous guanosine (1G), which is added during the 5′ excision reaction, and ends with the last base of the intron (1,572G), which is always a guanosine in the case of group I introns. The catalytic core consists of a paired region (P7) and a junction between two paired regions (J6/7). P7 and J6/7 are identical in sequence to the catalytic core of the Azoarcus pre-tRNA-ILE group I intron, which has been crystallized (50). Gray numbered arrows indicate the position and length of inserts that disrupt the conserved structure.

The number of cofactors required for processing of the aI5β intron is unprecedented for catalytic introns and splicing may involve an elaborate assembly/disassembly cycle reminiscent of other complex processes involving RNA, such as the biogenesis of ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs) like the ribosome or the dynamic process of spliceosome-mediated nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. As such, the aI5β system may represent an ideal experimentally tractable system to uncover general principals that operate in more complex systems. Here we have evaluated the relative importance of each aI5β splicing cofactor in vivo and, for the first time, investigated the role of Suv3p in processing of aI5β. Our results are consistent with Suv3p acting within the context of the mitochondrial degradosome to release limiting and tight binding aI5β cofactors from excised introns for additional rounds of splicing.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

All Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains (supplemental Table S1) were derived from the BY4741 strain (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0; Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). In some cases the ADE2 ORF was replaced with the URA3 cassette to serve as a positive marker for the presence of the mitochondrial genome; cells containing functional mitochondria will possess a red color when plated on YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose). The URA3 cassette was amplified by PCR from the pRS406 vector (87517, ATCC®, Manassas, VA), using primers 07A03 and 07A04 (supplemental Table S2) and was used to replace the ADE2 ORF by standard gene replacement protocols (29) and the established “High Efficiency Transformation Protocol” (30).

To generate the mrs1Δ, pet54Δ, mss18Δ, and mss116Δ deletion strains, the dominant kanr marker was amplified from 60 ng of pFA6a-kanMX6 plasmid DNA (31) using 5′-tailed primers with complementary sequence to 40-bp upstream of the start codon and 40-bp downstream of the termination codon (see supplemental Table S2). Transformants were selected on YPD medium supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml geneticin (final concentration, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then streaked to YPG medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 3% glycerol). Stains were selected that could not grow on YPG, but could grow when transformed with a plasmid containing the corresponding gene (rescue plasmid). PCR amplification, using primers upstream and downstream of the insertion sequences (supplemental Table S3), confirmed the insertion of the kanMX6 cassette at the correct genomic location.

Rescue plasmids were generated by the standard yeast in vivo cloning technique (32). In brief, the wild-type gene was amplified from BY4741 genomic DNA with primers (supplemental Table S3) that contain 5′-tails that are complementary to the CEN6 pRS415 yeast shuttle vector (87520, ATCC®). PCR product and linearized vector were transformed into yeast deletion strains, and the rescue plasmid was generated via homologous recombination. Plasmids were harvested and sequenced from transformants that could grow on both SCD/-Leu and SCG/-Leu medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.16% yeast synthetic drop-out medium without leucine (Sigma), 2% dextrose or 3% glycerol, pH 5.6). Sequence-confirmed plasmids were transformed into respective deletion strains, and the resulting strains were utilized for analysis.

Construction of the suv3-1 allele in our background strain (BY4741) is described in Fig. 4A, and primers are detailed in supplemental Table S4.

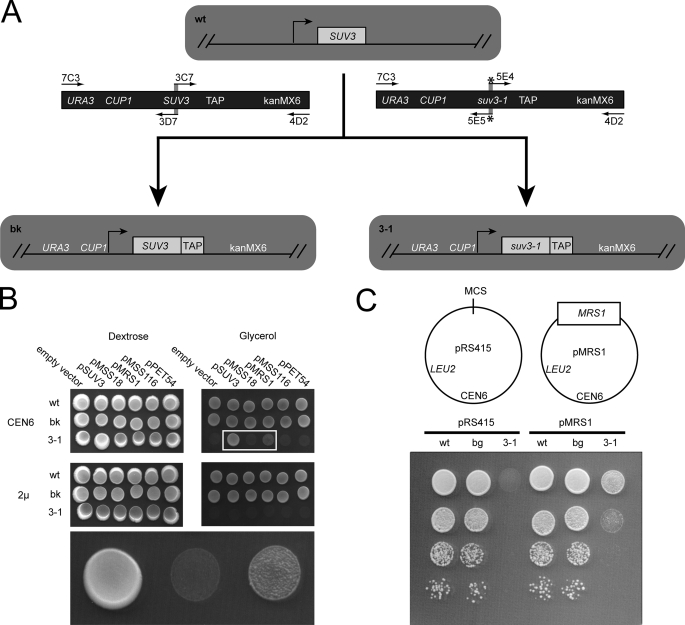

FIGURE 4.

Genetic interaction between SUV3 and MRS1. A, scheme to make chromosomal alterations of the BY4741 wild-type yeast strain (wt), to generate the CUP1-driven SUV3 TAP-tagged background strain (bg) and an identical strain with the exception of the suv3-1 point mutation (3-1). Overlapping PCR was used to generate the URA3::CUP1::SUV3::TAP::kanMX6 product or the identical molecule with the exception of the suv3-1 point mutation. Primers are shown as arrows, and the * indicates inclusion of the suv3-1 point mutation within the primer. Templates include a plasmid with a URA3::CUP1::SUV3 cassette and a yeast strain with the SUV3-TAP-tagged allele from Open Biosystems. B, growth assay to determine if there is a genetic interaction between the suv3-1 allele and the known aI5β splicing cofactors, which are expressed from low copy (CEN6) or high-copy (2μ) vectors. 5 μl of saturated cell cultures were spotted to dextrose (SCD/-Leu) or glycerol (SCG/-Leu) plates lacking leucine and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. The bottom row is an enlargement of the boxed section in the top row. C, dilution series growth assay on SCG/-Leu at 30 °C for 5 days to determine the relative strength of suppression of the suv3-1 glycerol growth defect by MRS1. Cells were also spotted to SCG/-Leu and SCD/-Leu control plates, which were incubated at 18, 24, 30, or 37 °C (data not shown).

For growth analysis, yeast strains were grown in liquid SCAD/-Leu, diluted to an A600 of 1, serially diluted (1/10, 1/100, 1/1000), and 5 μl of each dilution was spotted onto SCAD/-Leu and SCAG/-Leu plates.

Mitochondrial RNA Isolation

Cells were grown in SCAD/-Leu medium (600 ml) at 30 °C to an A600 of 1.2. Cells were harvested at 2,663 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, washed with RNase-free water, and then washed with SB3 buffer (50 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 3 mm dithiothreitol, 1 m sorbitol). Pellets were resuspended in 15 ml of SB3, to which 120 units of zymolyase (5 units/μl; Zymo Research Corp, Orange, CA) was added. Digestion proceeded for 3 h at 37 °C. The cells were further lysed using sonication, and the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation of the lysate. Mitochondria were pelleted by centrifugation at 17,555 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and lysed in 4 ml of TRIzol® (Invitrogen) via three cycles of vortexing for 2 min and incubation at room temperature for 3 min, followed by the addition of chloroform and centrifugation. The aqueous phase was precipitated with RNA precipitation solution (1.2 m NaCl, 0.8 m sodium citrate dibasic sesquihydrate, Sigma-Aldrich) and isopropanol. Pellets were washed twice with 75% ethanol and re-suspended in the RNA Storage Solution (Ambion, Austin, TX). In preparation for Northern blot or RT-PCR analysis, mitochondrial RNA was further purified using the RNeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The recommended protocol for DNase digestion was followed using 5 units of rDNase I (2 units/μl, RNase-free; USB, Cleveland, OH) with the provided reaction buffer. The RNA was then precipitated, resuspended in RNase-free water, and stored at −70 °C.

Western Blot

Cells were grown in SCAD/-Ura medium (100 ml) at 30 °C to an A600 of 6.5, collected by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and washed in 10 ml of SB3. Cell walls were digested by resuspending cells in 2 ml of SB3, addition of 4 mg of zymolyase, followed by 60 min of incubation at 37 °C with 300 rpm shaking. Spheroblasts were lysed by adding 10 μl of protease inhibitor followed by sonication using three 20-s pulses with 1 min of incubation on ice between pulses. Cell debris was pelleted as above, and supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C to pellet mitochondria, which were washed once with 2 ml of SB3. Wet cell pellets were resuspended to 0.8 mg/μl in YDB (20 mm HEPES-Na, pH 7.9, 200 mm NaCl, 0.125 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.005% Triton X-100), and 1 μl of protease inhibitor was added. Mitochondria were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles. Lysate was added to SDS loading buffer at a final BME concentration of 5% and proteins separated on a 3% × 12% SDS-PAGE stacking gel by standard electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a membrane and probed with primary antibody (rabbit anti-Myc) followed by secondary antibody (goat, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit). All antibodies were purchased from Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc., Newberg, OR and used as recommended by the manufacturer.

RNase Protection Assay

Radiolabeled RNA probes were made by in vitro transcription reactions from PCR-generated templates. Each primer contains a 27-base 5′ extension that incorporates the T7 promoter into the reverse primer or a non-encoded sequence in the forward primer to act as a positive control for probe digestion (supplemental Table S6). PCR was performed with pre-optimized Diamond Mix polymerase (Bioline, Taunton, MA) in the presence of an additional 0.5 mm MgCl2 and 1 μm primer set (see supplemental Table S6). Each reaction was denatured at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s/45 °C for 15 s/72 °C for 1 min. Radioactive label was included in the in vitro transcription reactions (3 μg of DNA template, 1× NEB transcription buffer, 0.1 m dithiothreitol, 10 mm r(G/T/C)TP, 1 mm UTP, 3000 Ci/mmol [32P]UTP, 0.5 μl RNase OUT, 5 μl of T7 RNA polymerase), and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. DNA template was digested with DNase I for 20 min at 37 °C and extracted with PCI and centrifuged through an illustraTM SephadexTM G-50 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Radiolabeled probes were gel purified and incubated with RNA sample overnight at 42 °C in Hybridization III buffer (Ambion). Unhybridized RNA was digested with 40 μg/ml RNase A and 0.0075 units/μl RNase T1 (Fig. 2B) or only 0.0075 units/μl RNase T1 for optimal analysis of aI5β containing pre-mRNA (Fig. 3B) in Digestion III buffer (Ambion) at 37 °C for 30 min. Reaction was stopped by addition of RNase Inactivation Solution (Ambion) and 350 μg of tRNA, followed by ethanol precipitation. Products were separated on a 10% acrylamide, 7 m urea, 5% glycerol gel. Blots were visualized with a phosphorimager and quantified with ImageQuant 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics). Products were normalized to tRNA.

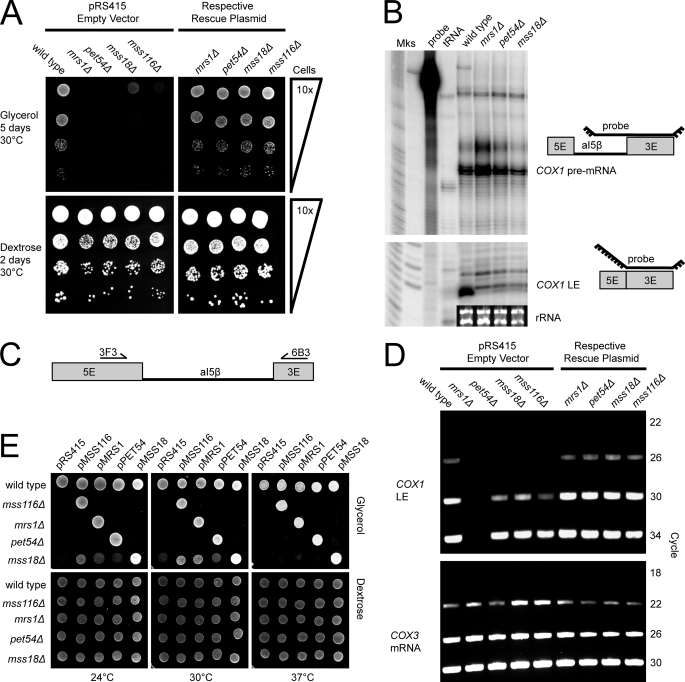

FIGURE 2.

MRS1 is essential for aI5β splicing, while PET54, MSS18, and MSS116 are splicing enhancers. A, growth assay for mitochondrial deficiency. Deletion strains and wild type (ade2Δ) were grown on SCAG/-Leu (top) or SCAD/-Leu (bottom) as a loading control. The top right panel is a control in which each strain is rescued by a plasmid borne copy of the deleted gene. B, RNase protection assay for splicing deficiency. COX1 pre-mRNA harboring the aI5β intron (top), COX1-ligated exons (LE, bottom), Mks (markers), probe (no RNase control), tRNA (no mitochondrial RNA control), and inset is the rRNA-loading control. C, primers used for RT-PCR. Unspliced aI5β is too large to be amplified and thus only LE are detected. D, RT-PCR assay for splicing deficiency. The top panel shows COX1 LE at various cycles. The bottom panel shows amplification of intronless COX3 mRNA as a loading control. E, growth assay for functional redundancy. The top panel shows growth on glycerol, and the bottom panel is a loading control on dextrose.

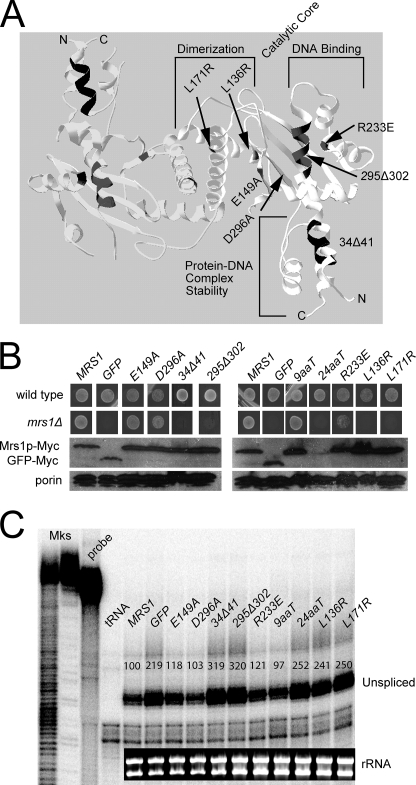

FIGURE 3.

Structural requirements of the Mrs1p protein for facilitating splicing of the aI5β intron. A, structure of the S. pombe mitochondrial four-way resolvase enzyme Ydc2p. The coordinates were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (Accession Number: 1KCF) and visualized with the Swiss-Pdb viewer (36). One monomer of the dimer has domains labeled. Mutations introduced into the homologous Mrs1p protein are marked; the numbering system is that of Mrs1p. C-terminal truncations of 9 and 24 amino acids (9aaT, 24aaT) are mutations of Mrs1p that are not homologous to the Ydc2p protein depicted in the crystal structure. B, growth phenotypes of Myc-tagged mutant proteins expressed in the mrs1Δ and wild type (BY4741) backgrounds. Strains were grown on SCG/-Ura for 5 days at 30 °C. Western blots of total mitochondrial protein using anti-Myc or anti-porin as a loading control. C, RNase protection assay for aI5β-containing COX1 pre-mRNA. Quantification is presented above each band as a percentage of unspliced in the MRS1 lane). The probe is same as Fig. 2B, but digestion was optimized for pre-mRNA detection (see “Experimental Procedures”). Mks (markers), probe (no RNase control), tRNA (no mitochondrial RNA control), and the inset is the rRNA-loading control.

RT-PCR of Mitochondrial RNA

Gene-specific primers used to generate each cDNA and amplify the products of splicing are described in supplemental Table S5. To analyze aI5β splicing from the COX1 pre-mRNA, COX1 cDNA was made using primer 6B3, and the 160 bp COX1 LE (ligated exon) product (Fig. 2D) was amplified with primer pair 3F3/6B3, which anneal to exons immediately upstream and downstream of aI5β. For aI5β multiplex RT-PCR, COX1 was reverse transcribed with primer 4A4, a 314 bp LE product was amplified with primer pair 6A10/4A3, and a 341 bp intron/3′exon border product was amplified with primer pair 6F10/4A3 (Fig. 5A). For bI3 multiplex RT-PCR, COB was reverse transcribed with primer 3A8, a 147 LE product was amplified with primer pair 3B8/3C8, which anneal to exons immediately upstream and downstream of bI3, and a 172-bp intron/3′exon border product was amplified with primer pair 3D8/3C8 (Fig. 5A). COX3 mRNA was reverse transcribed with primer 3H7, and a 335-bp product was amplified with primer pair 3I7/3J7 (Fig. 2D and Fig. 5A).

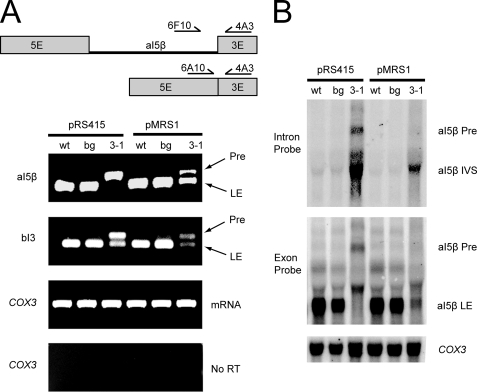

FIGURE 5.

Molecular splicing defects associated with CUP1::suv3-1::TAP can be partially rescued by overexpression of MRS1. A, analysis of aI5β and bI3 splicing by multiplex RT-PCR. The wt, bg, and 3-1 strains are the wild type, background, and suv3-1 strains described in Fig. 4. COX1 RNA was reverse-transcribed, and the cDNA amplified with the three primers shown in the scheme at the top (exons and intron are to scale). Pre, aI5β-containing COX1 pre-mRNA; LE, ligated exon. Note that the PCR conditions do not result in efficient amplification of intron-containing cDNA with 5′ and 3′ exon primers (see “Experimental Procedures”). A similar strategy, with appropriate primers, was used to analyze bI3 splicing. B, analysis of aI5β splicing by Northern blot. Total mitochondrial RNA was probed with 32P-labeled DNA oligonucleotide probes that hybridized to the aI5β intron (Intron Probe) or the exon adjacent to the 3′-end of the intron (Exon Probe) or the COX3 mRNA. IVS, free aI5β intron. The intronless COX3 mRNA was probed as a loading control.

SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and the recommended protocol were used to synthesize cDNAs from 50 ng/μl of mitochondrial RNA, except the RNA was incubated with primers and dNTPs at 70 °C for 5 min. Five units of RNase H (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) were used to digest the RNA complementary to the cDNA. Each cDNA was then diluted 1:5 and 2 μl was used as a template for PCR. Pre-optimized Diamond Mix (Bioline) was used to amplify each splicing product in the presence of an additional 5 mm MgCl2 and 0.4 μm primer sets (final concentrations in a 50 μl reaction volume). Each reaction was denatured at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 26 to 34 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s/50 °C for 15 s/72 °C for 1 min. Reaction products were separated on a 2.5% agarose/1× TAE gel, detected using ethidium bromide staining and visualized with GeneSnap software (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Northern Blots

DNA oligonucleotides (300 ng) were radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP (7,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) using T4 polynucleotide kinase and the provided manufacturer's buffer (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 90 min. The reactions were extracted with PCI and centrifuged through an illustraTM SephadexTM G-50 column. Gene-specific primers used for Northern analysis are described in supplemental Table S6. Mitochondrial RNA (20 μg) was analyzed on 1.4% agarose, 6% formaldehyde gel in 1× MOPS buffer (40 mm MOPS, 10 mm sodium acetate, 2.55 mm EDTA-free acid, pH 7.0). RNA was mixed with an equal volume of 2× loading dye (50% formamide, 0.5% formaldehyde, 1× MOPS buffer, 0.8 mg/ml ethidium bromide, 0.0025% bromphenol blue dye, and 0.0025% xylene cyanol FF dye) and incubated at 65 °C for 10 min prior to loading. Samples were transferred to Nitran SuperCharge membrane (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, UT) using 20x SSC buffer (3 m sodium chloride, 0.3 m sodium citrate) for ∼20 h. The blots were then irradiated twice at 254 nm in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the autocrosslink setting (25–50-s increments). Blots were washed with 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 65 °C for 1 h, and then incubated with prehybridization solution (10× Denhardt's Solution (0.2% Ficoll, 0.2% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 40,000 MW, 0.2% bovine serum albumin), 6× SSC buffer, and 0.1% SDS) at 42 °C for 1 h. Blots were probed using 5′-32P-labeled DNA oligonucleotides in prehybridization solution at 42 °C for 24 h and subsequently washed twice in 6× SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature for 15 min and once in 6× SSC/0.1% SDS at 40–45 °C for 15 min. The blots were visualized with a phosphorimager and quantified with ImageQuant 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics). The blots were stripped by boiling in 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS and re-probed in prehybridization solution with the appropriate 5′-32P-labeled DNA oligonucleotides.

RESULTS

The MRS1 Gene Product Is Absolutely Required for aI5β Splicing in Vivo

The aI5β splicing cofactors were identified in different S. cerevisiae strains and characterized under varied growth conditions. Because wild-type cells preferentially utilize fermentation when grown in medium containing glucose, mitochondrial dysfunction is detected via growth defects in the presence of a non-fermentable carbon source such as glycerol. To better understand the relative contributions of each cofactor, we obtained the BY4741 reference strain from Open Biosystems, and used this parent to construct isogenic deletion strains (Δ). We then characterized the effects of deleting the MRS1, PET54, MSS18, and MSS116 genes when grown on a glycerol carbon source (Fig. 2A) Deletion of SUV3 results in irreversible loss of the mitochondrial genome (33) and was not characterized in the initial analysis (but see below). Each deletion strain presented a growth defect on glycerol that could also be rescued by expression of the deleted gene from a low-copy plasmid (Fig. 2A).

To assess the efficiency of aI5β splicing, mitochondria were isolated from mid-log cultures, and purified RNA was analyzed by RNase protection and RT-PCR. Using a probe that hybridized to the 3′ intron/exon junction, the RNase protection assay showed that aI5β had undergone efficient splicing in the wild-type strain, but there was little evidence of aI5β splicing in the mrs1Δ, pet54Δ, and mss18Δ strains (Fig. 2B). Notably, mrs1Δ showed enhanced accumulation of aI5β-containing COX1 pre-mRNA, which is consistent with the Mrs1p protein having a role in the first step of splicing (27). Protein cofactors having a role after the first step of splicing, such as Pet54p, are likely to have loss of ligated exon product, with no increase in the amount of pre-mRNA because the partially spliced product is likely to be unstable (28). MSS116 is required for the splicing of all yeast mitochondrial introns, and thus the COX1 transcript, which contains 7 introns, is likely to be very unstable in mss116Δ (22). The mss116Δ strain was therefore not included in the RNase protection assay, because it is not sensitive enough for analysis of aI5β splicing from COX1 transcripts3(34).

A sensitive RT-PCR method was also used to assess the relative splicing efficiency of aI5β in each deletion strain. In this assay, primers in each exon were used to amplify the ligated exon product from cDNA under conditions that do not favor amplification of cDNA from unspliced material (Fig. 2C). We also monitored the amount of PCR product as a function of cycle number to judge when the reaction reached saturation. As shown in Fig. 2D, a PCR product corresponding to ligated exons could be detected as early as cycle 26 for the wild type, but not in any deletion strain. The amount of product saturated near cycle 30 in the wild-type strain. Ligated exon product could be detected in the pet54Δ, mss18Δ, and mss116Δ strains at cycle 30 but no product was observed for the mrs1Δ strain up to cycle 34 (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these molecular phenotypes suggest that although splicing is very inefficient in each of the deletion strains, MRS1 is absolutely required for aI5β splicing.

Interestingly, the deletion of MRS1 could not be complemented by overexpression of any other aI5β cofactors, suggesting that none act redundantly with MRS1 (Fig. 2E). These observations are consistent with the interpretation that Mrs1p fulfills a unique and essential function in promoting splicing of aI5β in vivo.

Evidence That the Ancestral DNA Binding Site of Mrs1p Is Involved in Its Splicing Function

Mrs1p has previously been observed to share 29% sequence identify with yeast Cce1p, which is the S. cerevisiae mitochondrial Holliday junction-cleaving enzyme that functions in resolving recombination intermediates (35). A crystal structure of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homolog, Ydc2p, has been solved and shows that the enzyme is a dimer and biochemical and modeling studies suggest that the S. pombe and S. cerevisiae proteins recognize an extended 4-way junction (35, 36). Recombinant Mrs1p has likewise been shown to be a dimer in solution (37).

To determine which features of Mrs1p contribute to its splicing function, a series of mutations were constructed, guided by the Ydc2p crystal structure and a published alignment of Mrs1p, Cce1p, and Ydc2p (35, 36). Mutations were cloned in a yeast expression plasmid in-frame with the Myc tag at the C-terminal end and transformed into the MRS1 deletion strain. In addition to aI5β processing, Mrs1p also functions in splicing of the bI3 group I intron, but otherwise is dispensable for respiratory function (23, 38, 39). As such, growth defects on non-fermentable carbon are directly due to impaired splicing (see below).

Single amino acid substitutions were introduced at conserved residues in the putative dimer interface (L171R, L136R), putative acidic catalytic residues (E149A, D296A), and a conserved basic residue in the putative DNA binding surface (R223E). In addition, deletions were made in a conserved α-helix in the putative DNA binding surface (295Δ302) and in the N-terminal domain (34Δ41), whereas truncations of 9 (9aaT) and 24 (24aaT) amino acids were constructed at the C terminus (Fig. 3A).

Growth phenotypes on glycerol are shown in Fig. 3B, and a Western blot shows that most of the mutants are expressed at wild-type levels. The N and C terminus of the Mrs1p protein may interact to form a domain composed of 3 α-helices, which has been implicated in stabilizing the protein-DNA complex in Cce1p and Ydc2p (40, 41). Disruption of the C-terminal domain by a 24-amino acid truncation results in loss of aI5β splicing, while disruption of the N terminus (34Δ41) resulted in an unstable protein. From the expressed mutants, it is clear that proteins containing a mutation predicted to disrupt dimer formation do not support growth. In addition, both a point mutation and deletion of a helix in the putative DNA binding surface result in growth defects. In contrast, mutation of acidic catalytic residues had no effect on growth. Defective aI5β splicing correlated well with mutants that show a growth defect on glycerol medium (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data suggest that the integrity of a dimer interface and the ancestral DNA binding surface are important for Mrs1p splicing function, whereas its remnant active site does not contribute to splicing.

A Genetic Interaction between SUV3 and MRS1

Deletion of the SUV3 gene results in loss of the mitochondrial genome (33), and thus its role in aI5β and bI3 splicing have been difficult to ascertain. The suv3-1 allele, however, does not result in mitochondrial genome loss and has been characterized as having a defect in aI5β and bI3 splicing (19). Sequencing showed that suv3-1 contains a single mis-sense mutation near motif Ia (V272L) that contributes to binding of the unwound tail of a duplex in a related SKI2-like helicase, Hel308p (14, 33). We recreated the suv3-1 mutation in the BY4741 strain by replacing the entire SUV3 ORF with an in vitro synthesized suv3-1 ORF that is flanked by selection markers and sequences for homologous recombination upstream and downstream of the endogenous SUV3 ORF (“Experimental Procedures” and Fig. 4A). The upstream URA3 cassette puts suv3-1 under control of the CUP1 promoter, and the downstream kanMX6 cassette creates a suv3-1 C-terminal TAP tag fusion, and thus we termed this strain CUP1::suv3-1::TAP. An identical strain was created, with the exception of the suv3-1 point mutation, and named CUP1::SUV3::TAP.

To determine if a genetic interaction exists between SUV3 and aI5β splicing cofactors, we assayed for growth of CUP1::suv3-1::TAP on glycerol medium when overexpressing MSS18, MRS1, MSS116, or PET54. Each gene was cloned with its associated promoter and UTRs into a low-copy (CEN6) or high-copy (2μ) expression vector. SUV3 was also cloned to provide a positive control for rescue of suv3-1 phenotypes. Consistent with a mitochondrial defect, CUP1::suv3-1::TAP was unable to utilize glycerol when harboring an empty vector, while the CUP1::SUV3::TAP strain grew similar to the wild-type strain (Fig. 4B). SUV3 was able to rescue the glycerol growth defect, but only when expressed from the CEN6 plasmid. MRS1 was the only aI5β splicing cofactor that was able to suppress the glycerol growth defect, and similar to SUV3, the effect could only be seen by expression from the CEN6 plasmid. We speculate that excessive expression from the 2μ vector may overwhelm the mitochondrial protein-import machinery, which may be generally detrimental to mitochondrial function. To confirm the ability of MRS1 to suppress the glycerol growth defect of CUP1::suv3-1::TAP, we performed a dilution series growth assay at 30 °C (Fig. 4C), and at 18, 24, or 37 °C (data not shown), and observed a partial suppression in each case. Importantly, only Mrs1p-dependent introns showed splicing defects in the original suv3-1 mutant (19). Thus the original genetic interaction between suv3-1 and the aI5β and bI3 introns is now expanded to include a genetic interaction between SUV3 and MRS1.

Splicing in the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP strain was assessed using a multiplex RT-PCR approach (Fig. 5A). The results showed that both aI5β and bI3 splicing efficiency was significantly reduced in CUP1::suv3-1::TAP, but there is no effect in CUP1::SUV3::TAP (Fig. 5A). We also investigated the splicing defect by Northern analysis on mitochondrial RNA using exonic and intronic probes (Fig. 5B). A probe to the aI5β 3′ exon showed that ligated exons predominate in control strains, whereas only the unspliced precursor was apparent in CUP1::suv3-1::TAP, confirming that this mutation has an aI5β splicing defect (Fig. 5B). A probe to the aI5β intron showed little precursor or free intron in the control strains, whereas there was a dramatic increase of both species in CUP1::suv3-1::TAP (Fig. 5B). Northern blots using a probe against the 3′ exon of bI3 showed a similar decrease in mature COB mRNA in CUP1::suv3-1::TAP relative to the control strains (data not shown). Taken together, these data provide evidence that the splicing phenotypes of CUP1::suv3-1::TAP are very similar to the original suv3-1 strain (19).

As judged by RT-PCR, the splicing of aI5β in the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP strain was significantly improved in the presence of MRS1 overexpression (Fig. 5A), and this result was confirmed by Northern analysis (Fig. 5B). In this regard, the ligated exon product from aI5β splicing was clearly evident when MRS1 was overexpressed, whereas the amount of aI5β containing precursor mRNA was decreased (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that rescue of the respiratory competence of CUP1::suv3-1::TAP by MRS1 overexpression is associated with an increased splicing efficiency of aI5β.

Overexpression of a 5′ → 3′ Exoribonuclease Rescues Splicing Defects in the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP Strain

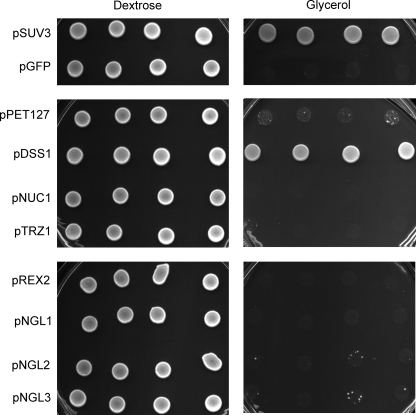

It was shown previously that overexpression of either the degradosome exoribonuclease DSS1, or the mitochondrial 5′ → 3′ exoribonuclease PET127, suppressed the respiratory negative phenotype of SUV3 gene disruptions in a mitochondrial intronless background (42, 43). To test whether these gene products or other ribonucleases (both putative and confirmed) could rescue intron splicing defects in our suv3-1 strain, a suppressor screen was carried out. In this screen an expression plasmid bearing the gene of interest was introduced into CUP1::suv3-1::TAP and tested for respiratory competence by growth on glycerol-containing medium. The data in Fig. 6 clearly showed that overexpression of DSS1 or SUV3 rescued growth. In addition, there was partial rescue by overexpression of PET127. No other gene showed suppression of the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP phenotype.

FIGURE 6.

Glycerol growth defect in the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP strain is rescued by overexpression of mitochondrial ribonucleases. A, CUP1::suv3-1::TAP strain was transformed with low copy vectors (pRS415) expressing GFP as a vector control or mitochondrial ribonucleases (PET127, DSS1, TRZ1, and REX2) or genes with homology to ribonucleases (NGL1 thru -3) that show mitochondrial defects when disrupted (51). Four individual transformants per vector were spotted to SCD/-Leu (left) or SCG/-Leu plates (right) and grown at 30 °C for 2 or 10 days respectively. Note that some NGL2 and 3 spots show spontaneous revertants, and these may represent suppression via mutations in the mitochondrial RNA polymerase gene as observed previously (46).

To furthered explore the ability of PET127 overexpression to compensate for a defect in SUV3, we constructed a yeast strain in which the SUV3 gene is disrupted by kanMX6, and the PET127 gene is simultaneously overexpressed from a CUP1 promoter (42, 44). In the resulting strain, a significant amount of COX1-ligated exon exists (data not shown), which contrasts the absence of aI5β splicing in our suv3-1 strain (Fig, 5A). The CUP1::suv3-1::TAP growth phenotype was also suppressed by introducing a plasmid-borne copy of hSUV3, the human homolog of SUV3 (data not shown) (45). Collectively, these data suggest that Suv3p acts indirectly on splicing of aI5β.

DISCUSSION

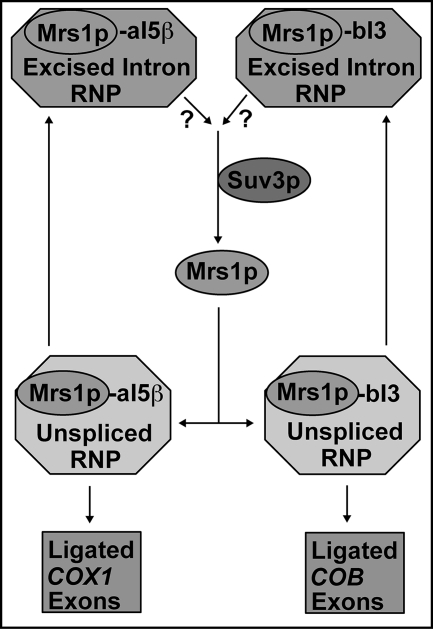

Disruption of the degradosome has a number of consequences with perhaps the most striking feature being the accumulation of aberrant and unprocessed mitochondrial RNAs, as well as excised group I introns. It has been argued that the mitochondrial degradosome does not play a direct role in RNA processing, but rather is responsible for RNA surveillance (46). In this regard, the Suv3p/Dss1p heterodimer functions to degrade aberrantly processed mRNAs that could otherwise disrupt the expression of mature messages via competition for translation apparatus. Likewise, improperly processed rRNA species could compete for ribosomal proteins resulting in defects in mitochondrial ribosome assembly. In addition, it has been shown that the degradosome is required to “clear” the mitochondrion of excised group I introns that have been shown to catalyze an “exon-reopening” reaction on their processed, parent RNAs, thus rendering them non-functional (9, 19). Here, we provide evidence for an additional function of the degradosome: releasing intron-bound splicing cofactors to replenish pools available for splicing of new transcripts.

The splicing phenotype of the suv3-1 strain is intron specific, and only processing of the aI5β and bI3 introns are affected (19). At the time, it was unclear whether Suv3p played a direct or indirect role in splicing. With regard to the former, Suv3p is a member of the DEXH/D-box family of ATPases, members of which have been found to unwind RNA duplexes. Indeed, evidence suggests that two proteins of the DEAD-box subfamily, Cyt-19p and Mss116p, are involved in fungal mitochondrial splicing as ATP-dependent RNA chaperones that resolves misfolded intermediates (22, 47). However, we have demonstrated that overexpression of ribonuclease PET127 or DSS1 suppressed the splicing defects in CUP1::suv3-1::TAP, and overexpression of PET127 supported splicing in a SUV3 deletion strain. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that Suv3p is playing an indirect role in splicing.

Interestingly, the aI5β and bI3 introns belong to different structural subclasses and do not share significant sequence homology, making this shared requirement for wild-type Suv3p unclear (48). However, like SUV3, disruption of the MRS1 gene results in splicing defects for both introns (23, 39). Here we show a strong genetic interaction between MRS1 and SUV3 in that overexpression of MRS1 partially suppressed splicing defects in the suv3-1 strain. Recent work has shown that two Mrs1p dimers specifically bind both aI5β- and bI3-containing pre-mRNAs and, in collaboration with other intron-specific cofactors, facilitate splicing in vitro (27, 49). Because the two introns belong to different structural subclasses and do not share significant sequence homology, it seems likely that, like most group I intron splicing cofactors studied thus far, Mrs1p functions to facilitate splicing of both introns by binding the conserved intron core and stabilizing the catalytically active structure. In support of this view, the Mrs1p structural requirements for splicing of both introns are the same: both require the ancestral DNA binding site of Mrs1p (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Overall, our observations are consistent with a model in which Mrs1p is efficiently removed from spliced introns via RNA degradation, catalyzed by the Suv3p-containing degradosome, effectively recycling this cofactor for additional rounds of splicing (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Proposed working model for recycling of the Mrs1p splicing cofactor by Suv3p. The excised aI5β and bI3 intron RNA is complexed with the Mrs1p protein and potentially other splicing factors (top). The Suv3p protein, acting through its degradosome function, liberates Mrs1p by degradation of the RNA (middle). Mrs1p participates in the next round of aI5β and bI3 splicing (bottom). Question marks reflect a gap in our knowledge of the degree to which Suv3p recycles Mrs1p from aI5β versus bI3.

Both the aI5β and bI3 introns require additional cofactors for splicing and presumably these too are recycled by the mitochondrial degradosome function. However, because overexpression of Mrs1p is sufficient to partially rescue splicing in the CUP1::suv3-1::TAP background, this suggests that in both cases, splicing efficiency in vivo is limited by the availability of Mrs1p. The central importance of Mrs1p in splicing aI5β and bI3 is supported by the inability to detect any spliced product using a sensitive RT-PCR approach in the mrs1Δ strain under conditions where strains deleted for other cofactors yield product (Fig. 2D and data not shown). Furthermore, in vitro splicing of the bI3 intron absolutely requires Mrs1p along with an intron-encoded maturase (37).

Whereas it is clear that Mrs1p is essential for facilitating splicing of the aI5β and bI3 introns, it is not immediately clear why an “active” recycling process using Suv3p is necessary for this cofactor. The binding constants measured in Mg2+-containing splicing buffer are similar (∼6 nm for aI5β at 37 °C and ∼1 nm for bI3 at 36 °C) and two Mrs1p dimers bind each RNA (27, 37, 49). The affinity is modest, but as shown for the bI3 intron, other splicing cofactors can increase affinity of Mrs1p for its RNA targets (49). Thus, upon completion of splicing, Mrs1p may remain bound to the excised RNA for a significantly long time, limiting its availability. In addition, the cofactor bound intron presumably retains activity and can catalyze an “exon-reopening” reaction on their processed, parent RNAs (9). Thus, the Suv3p-containing degradosome plays two essential, anti-toxicity roles in aI5β and bI3 intron biology: it replenishes splicing cofactor pools and removes the potentially dangerous catalytically active intron RNAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Longtine (Washington University at St. Louis, School of Medicine) for the pFA6a-kanMX6 plasmid. We thank Dr. Philip S. Perlman (Howard Hughes Medical Institute) for advice and providing yeast strains used in earlier, exploratory experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants F32GM078969 and T32HD007104 (to E. M. T.) and GM-62853 (to M. G. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S6.

A. L. Bifano, E. M. Turk, and M. G. Caprara, manuscript submitted.

- COX1

- cytochrome oxidase I subunit

- RNP

- ribonucleoprotein

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- UTR

- untranslated region

- COB

- apocytochrome b subunit

- ORF

- open reading frame.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shadel G. S., Clayton D. A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 16083–16086 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cliften P. F., Jang S. H., Jaehning J. A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7013–7023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsunaga M., Jaehning J. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44239–44242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shadel G. S. (2004) Trends Genet 20, 513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amiott E. A., Jaehning J. A. (2006) Mol. Cell 22, 329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann B., Nickel J., Speer F., Schafer B. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 377, 1024–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer B. (2005) Gene 354, 80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambowitz A. M., Zimmerly S., Perlman P. S. (1999) in The RNA World II (Gesteland R. F., Cech T. R. ed), pp 451—485, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margossian S. P., Li H., Zassenhaus H. P., Butow R. A. (1996) Cell 84, 199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margossian S. P., Butow R. A. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci 21, 392–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dziembowski A., Piwowarski J., Hoser R., Minczuk M., Dmochowska A., Siep M., van der Spek H., Grivell L., Stepien P. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1603–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Cruz J., Kressler D., Linder P. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci 24, 192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyle A. M. (2008) Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37, 317–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Büttner K., Nehring S., Hopfner K. P. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 647–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caprara M. G. (2010) Ski2-like DExH Proteins: Biology and Mechanism, Royal Society of Chemistry, Biomolecular Sciences, in press [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golik P., Szczepanek T., Bartnik E., Stepien P. P., Lazowska J. (1995) Curr. Genet 28, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dziembowski A., Malewicz M., Minczuk M., Golik P., Dmochowska A., Stepien P. P. (1998) Mol. Gen. Genet 260, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu H., Conrad-Webb H., Liao X. S., Perlman P. S., Butow R. A. (1989) Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 1507–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad-Webb H., Perlman P. S., Zhu H., Butow R. A. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 1369–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seraphin B., Simon M., Boulet A., Faye G. (1989) Nature 337, 84–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seraphin B., Simon M., Faye G. (1988) EMBO J. 7, 1455–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H. R., Rowe C. E., Mohr S., Jiang Y., Lambowitz A. M., Perlman P. S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bousquet I., Dujardin G., Poyton R. O., Slonimski P. P. (1990) Curr. Genet 18, 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valencik M. L., Kloeckener-Gruissem B., Poyton R. O., McEwen J. E. (1989) EMBO J. 8, 3899–3904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodson S. A. (2005) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golden B. L., Kim H., Chase E. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bifano A. L., Caprara M. G. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383, 667–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaspar B. J., Bifano A. L., Caprara M. G. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2958–2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., Hieter P., Boeke J. D. (1998) Yeast 14, 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gietz R. D., Woods R. A. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 350, 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Yeast 14, 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua S. B., Qiu M., Chan E., Zhu L., Luo Y. (1997) Plasmid 38, 91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stepien P. P., Margossian S. P., Landsman D., Butow R. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6813–6817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohr S., Matsuura M., Perlman P. S., Lambowitz A. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3569–3574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wardleworth B. N., Kvaratskhelia M., White M. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23725–23728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ceschini S., Keeley A., McAlister M. S., Oram M., Phelan J., Pearl L. H., Tsaneva I. R., Barrett T. E. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6601–6611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bassi G. S., de Oliveira D. M., White M. F., Weeks K. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 128–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreike J., Schulze M., Ahne F., Lang B. F. (1987) EMBO J. 6, 2123–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreike J., Schulze M., Pillar T., Korte A., Rodel G. (1986) Curr. Genet 11, 185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahn J. S., Whitby M. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29121–29129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sigala B., Tsaneva I. R. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 2837–2847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wegierski T., Dmochowska A., Jablonowska A., Dziembowski A., Bartnik E., Stepień P. P. (1998) Acta Biochim. Pol. 45, 935–940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dmochowska A., Golik P., Stepien P. P. (1995) Curr. Genet 28, 108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labbé S., Thiele D. J. (1999) Methods Enzymol. 306, 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dmochowska A., Kalita K., Krawczyk M., Golik P., Mroczek K., Lazowska J., Stepień P. P., Bartnik E. (1999) Acta Biochim. Pol. 46, 155–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogowska A. T., Puchta O., Czarnecka A. M., Kaniak A., Stepien P. P., Golik P. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1184–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohr S., Stryker J. M., Lambowitz A. M. (2002) Cell 109, 769–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michel F., Westhof E. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 216, 585–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bassi G. S., Weeks K. M. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 9980–9988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams P. L., Stahley M. R., Kosek A. B., Wang J., Strobel S. A. (2004) Nature 430, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinders J., Zahedi R. P., Pfanner N., Meisinger C., Sickmann A. (2006) J. Proteome Res. 5, 1543–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.