Abstract

The predominantly nuclear heterogenous ribonucleoprotein A18 (hnRNP A18) translocates to the cytosol in response to cellular stress and increases translation by specifically binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of several mRNA transcripts and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4G. Here, we identified a 51-nucleotide motif that is present 11.49 times more often in the 3′-UTR of hnRNP A18 mRNA targets than in the UniGene data base. This motif was identified by computational analysis of primary sequences and secondary structures of hnRNP A18 mRNA targets against the unaligned sequences. Band shift analyses indicate that the motif is sufficient to confer binding to hnRNP A18. A search of the entire UniGene data base indicates that the hnRNP A18 motif is also present in the 3′-UTR of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related (ATR) mRNA. Validation of the predicted hnRNP A18 motif is provided by amplification of endogenous ATR transcript on polysomal fractions immunoprecipitated with hnRNP A18. Moreover, overexpression of hnRNP A18 results in increased ATR protein levels and increased phosphorylation of Chk1, a preferred ATR substrate, in response to UV radiation. In addition, our data indicate that inhibition of casein kinase II or GSK3β significantly reduced hnRNP A18 cytosolic translocation in response to UV radiation. To our knowledge, this constitutes the first demonstration of a post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism for ATR activity. hnRNP A18 could thus become a new target to trigger ATR activity as back-up stress response mechanisms to functionally compensate for absent or defective responders.

Keywords: Diseases/Cancer/Carcinogenesis, DNA/Damage, Protein/Binding/RNA, RNA/Ribonuclear Protein RNP, RNA/Translation, ATR

Introduction

ATR2 belongs to a family of protein serine-threonine kinases whose catalytic domains share evolutionary relationship with mammalian and yeast phosphoinositide 3-kinases (1). The ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein kinase as well as the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) and hSMG-1 also belong to this family (2). Although ATR and DNA-PKcs share substantial sequence homology and substrates specificity with ATM, they cannot compensate for the lack of a functional ATM, at least not redundantly. ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs are responsible for initiating the signaling cascades in response to DNA double-strand breaks (2), whereas hSMG-1 regulates nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (2). DNA-PKcs activity is apparently restricted to phosphorylation of DNA repair proteins, whereas ATM and ATR phosphorylate a larger repertoire of substrates from cell cycle regulators to DNA repair proteins (3). ATR is primarily activated by UV radiation, replication stress, and single-strand DNA gaps but can also respond to double-strand breaks albeit, at much slower kinetics than ATM (3). The recruitment of ATR to stalled replication fork and single-strand DNA breaks has recently been described and involves the coordinate interaction of several proteins including the replication protein A (RPA), the ATR-interacting protein, and the topoisomerase 2-binding protein TopBP1 (4). The delay in ATR activation in response to ionizing radiation is apparently linked to its recruitment to the double-strand break. This delay is in part responsible for the lack of redundancy in the cellular response to DNA damage in cell lines deficient for ATM. Supporting this concept, a recent report indicates that ectopic activation of ATR is sufficient to activate a G1 cell cycle checkpoint in ataxia telangiectasia fibroblasts even in the absence of DNA damage (5). Identification of mechanisms that could activate ATR in a timely fashion could thus be beneficial for cells lacking primary responders such as ATM.

hnRNP A18 was the first RNA-binding protein (RBP) reported to be inducible by UV radiation (6). hnRNP A18 was originally cloned by hybridization subtraction on the basis of rapid induction in UV radiated Chinese hamster ovary cells. Since then, the human hnRNP A18 was cloned and characterized (7). The hnRNPs are abundant RBPs predominantly found in the nucleus and involved in several cellular activities ranging from transcription and mRNA processing in the nucleus to cytoplasmic mRNA translation and turnover (8). This family of proteins counts more than 20 different members that have been highly conserved (9). The hnRNP A18 is different from most hnRNPs in that it contains only one RNA-binding domain and has several arginine and glycine residues (RGG boxes) in its auxiliary domain. In contrast to most hnRNPs that are constitutively expressed, hnRNP A18 mRNA and protein levels can be induced by cellular stress such as UV (7) and hypoxia (10). hnRNP A18 is not only induced by UV and hypoxia but is also translocated from the nucleus to the cytosol in response to the cellular stresses. In the cytosol, hnRNP A18 binds to 3′-UTR of RNA transcripts and increases translation (11). The increased translation is mediated by hnRNP A18 interaction with eukaryotic initiation factor 4G, a component of the general translational machinery (12). The overall effect of hnRNP A18 activation is cytoprotection against the cellular insults (11). Here, using computational analyses, we identified a 51-nucleotide RNA motif that is present 11.49 times more often in the 3′-UTR of hnRNP A18 mRNA targets than in the UniGene data base. This motif is also present in the 3′-UTR of ATR mRNA. Validation of this predicted motif as a bona fide hnRNP A18 recognition motif is provided by amplification of endogenous ATR transcripts from polysomal fractions immunoprecipitated with hnRNP A18 antibodies. Moreover, overexpression of hnRNP A18 leads to increased ATR protein levels and increased phosphorylation of Chk1, an ATR preferred substrate (13) in response to UV radiation. These data described for the first time a post-transcriptional mechanism to regulate ATR activity in response to cellular stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Treatments

The human colorectal carcinoma RKO cells were grown and maintained as described before (11). The RKO cells were either stably (11) or transiently transfected with GFP-hnRNP A18 (11) and hnRNP A18 phospho mimetic mutant with Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). The cells transfected with the wild type hnRNP A18 were pretreated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (100 μm for 4 h) prior to UV exposure (14 Jm−2) or exposed to 200 μm CoCl2 for 6 h (Biomol International, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Where indicated the cells were either treated with the casein kinase 2 (CK2) inhibitor III TBCA (Calbiochem, EMD, Gibbstown, NJ) 100 nm or the GSK3β inhibitor VIII (Calbiochem) 100 nm for 1 h prior to UV exposure and 4 h following radiation. UV treatment was performed as described previously (6) except that the source of UVC was a Philips 30 W germicidal lamp emitting at 253.7 nm, and the intensity of the UV lamp was determined with a UVX Radiometer (UVP Inc., Upland, CA). The hnRNP A18 phospho mimetic mutant was produced by site-directed mutagenesis (Mutagenex Inc., Piscataway, NJ) where Ser144, Ser148, Ser152, and Ser155 were replaced with glutamic acid.

Confocal Microscopy

The slides were imaged with an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 Confocal, using the 40×/1.3 oil objective. Random fields were chosen using 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole and then scanned with the 488-nm laser for GFP signal. The base line was set with the control (untreated) GFP-hnRNP A18 transfected in RKO cells. All of the cells were imaged under the same conditions. Using ImageJ software, regions of interest were defined on the nuclei and cytoplasm of 100 cells expressing GFP-hnRNP A18. The relative cytoplasmic expression was calculated by dividing cytoplasmic expression (total − nuclear) by total expression times 100.

Computational Analysis

The hnRNP A18 binding motif was identified from the 3′-UTR of the experimental data collected in Ref. 11. The computation was performed using the National Institutes of Health Biowulf computer farm. Totally 2923 motifs were first identified from the experimental data. The 2923 motifs were modeled by the Stochastic context-free grammar (SCFG) algorithm and the SCFG enhanced with maximum likelihood. Both models were searched against the experimental data set (3′-UTR). From the result, the best 100 motifs from the above search were selected based on the frequency of hits. The top 100 motifs were further searched against the entire UniGene 3′-UTR data set. The ratio of the motif hits/kb in the experimental data set over the entire UniGene data set was calculated for each of the 100 motifs. The final motif was chosen, which is high in the ratio and also highly frequent in the experimental data set.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the relative (percentage) ratios of GFP-hnRNP A18 expressed in the cytoplasm over total GFP-hnRNP A18. The calculations were performed by one-way analysis of variance and t test. A probability value of <0.05 is considered significant.

RNA Band Shifts

RNA band shifts were performed as described (12) with the exception that incubation of the reactions was performed at 37 °C. Briefly, increasing amounts of recombinant GST-hnRNP A18 were incubated with radiolabeled hnRNP A18 RNA binding motif 1, ATR 3′-UTR (nucleotide 150–199), R1 or R2 probe, and tRNA (50 μg/ml) as nonspecific competitor. The RNA probes were synthesized by in vitro transcribing the indicated DNA sequences downstream of a T7 promoter (12), and the resulting RNAs were gel-purified. The reactions were run on a 10% native polyacrylamide gel in the cold room.

Polysome Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of the polysomal fractions was performed under conditions that preserve the association of RNA-binding proteins with target mRNAs essentially as described before (14).

Western Blots

Western blots were performed as described previously (12). ATR and Chk1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and phosphorylated Ser317 Chk1 antibody was from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). All of the antibodies were rabbit polyclonal and were used at 1:1000 dilutions.

RESULTS

hnRNP A18 Translocation to the Cytosol in Response to Cellular Stress Is Phosphorylation-dependent

We have previously shown that the predominantly nuclear hnRNP A18 is translocated to the cytosol in response to UV radiation (11). Here the translocation was quantitated by confocal microscopy. The data shown in Fig. 1 indicate that as observed before (11), the levels of hnRNP A18 markedly increase in the cytosol of UV radiated cells. The cytoplasmic accumulation of hnRNP A18 does not result from a nuclear import blockage of newly synthesized protein because treating the cells with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide prior to UV exposure did not prevent translocation (data not shown). Cytoplasmic translocation was also observed with the hypoxia mimetic agent CoCl2 (data not shown).

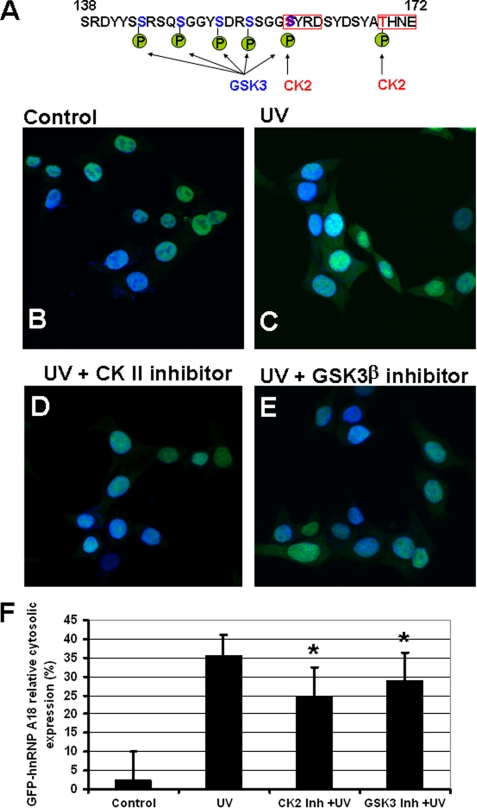

FIGURE 1.

A, predicted phosphorylation sites on hnRNP A18 carboxyl-terminal end. Residues 138–172 are depicted. CK2 sites are in red boxes, and the predicted GSK3 sites are highlighted in blue. B–E, confocal microscopy of RKO cells transfected with GFP-hnRNP A18. The cells were left untreated (B, control), exposed to UV radiation (C, 14 Jm−2, 4 h), or treated with either CK2 inhibitor (D) or GSK3 inhibitor (E) for 1 h prior to UV exposure. F, relative expression of GFP-hnRNP A18 expressed as a ratio (%) of cytoplasmic over total GFP-hnRNP A18. t test was used to calculate statistical significance between UV and CK2 inhibitor + UV; UV and GSK3β inhibitor + UV; CK2 inhibitor + UV and GSK3β inhibitor + UV. All of the calculations yield p < 0.001 (*).

Post-translational modifications of RBPs have been shown to regulate their cellular localization as well as RNA binding activity (15, 16). The hnRNP A18 contains several consensus phosphorylation sites, but GSK3β sites are the ones that increase its RNA binding activity (12). GSK3 has a unique substrate specificity that is best described by a glycogen synthase phosphorylation pattern (17). The substrate has first to be phosphorylated by another kinase at a serine or threonine residue located four residues carboxyl-terminal to the GSK3 site. This priming phosphate allows GSK3 to phosphorylate its first target residue, which is then used as a priming phosphate to phosphorylate the next target residue four residues upstream and so on. As shown in Fig. 1A, the glycogen synthase pattern is repeated in the hnRNP A18 sequence, where a CK2 site is located four residues carboxyl-terminal to the GSK3β site. To determine whether hnRNP A18 phosphorylation by GSK3β or CK II could affect its cellular localization, we pretreated RKO cells transfected with GFP-hnRNP A18 with CK2 and GSK3β inhibitors prior to UV exposure. The data shown in Fig. 1 (B–F) indicate that pretreating the RKO cells with either 100 nm CK2 inhibitor or GSK3β inhibitor for 1 h is sufficient to significantly reduced hnRNP A18 translocation to the cytosol. Differences between the three groups (UV, CK2 inhibitor prior to UV, and GSK3β inhibitor prior to UV) was also significant when analyzed by the one-way analysis of variance method (p < 0.001). Although both inhibitors affect hnRNP A18 translocation, the effect of CK2 inhibitor is more pronounced (Fig. 1F and p < 0.001). This would suggest that although GSK3β likely contributes to translocation it may not be sufficient by itself. In fact, mutation of the four GSK3β sites (Ser144, Ser148, Ser152, and Ser155) with glutamic acid resulted in spontaneous cytoplasmic translocation that, although noticeable, was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Identification of an hnRNP A18 RNA Motif

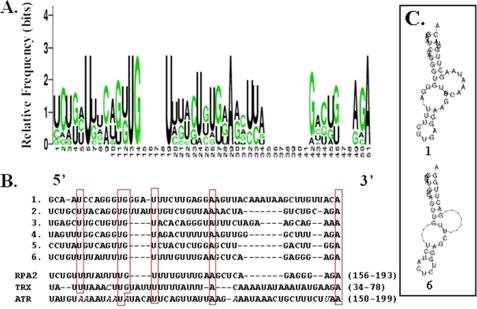

In an effort to identify hnRNP A18 mRNA targets, we previously developed an immunotube-based strategy having low nonspecific RNA binding capacity that preserved endogenous RNA tertiary structure during the binding reaction performed in solution (11). Using this technique, we identified more than 46 potential hnRNP A18 mRNA targets (11). Validation of the technique used has been provided for two selected transcripts, RPA and thiredoxin (TRX) (11). Because no apparent sequence homology could be identified between the different transcripts selected, we performed a computational analysis of the sequences available to determine whether a common RNA motif could be found among the potential hnRNP A18 mRNA targets (experimental data set). Common binding motifs were searched based on both primary sequences and secondary structures from the aligned sequences of the experimental data set. The program MFOLD was used to cross-validate the selected secondary structures. The computation was performed using the National Institutes of Health Biowulf computer farm. A total of 2923 motifs was first identified from the experimental data set. The 2923 motifs were modeled by the SCFG algorithm and the SCFG enhanced with maximum likelihood. Both models were searched against the experimental data set (3′-UTR). From this search, the best 100 motifs were selected based on the frequency of hits. These 100 motifs were further searched against the entire UniGene 3′-UTR data set. The ratio of the motif hits/kb in the experimental data set over the entire UniGene data set was calculated for each of the 100 motifs. The final motif was chosen based on a high ratio (motif hits/kb) and a high frequency in the experimental data set. This motif, comprising 51 nucleotides, was found 11.49 times more often in the 3′-UTRs of the data set than in the 3′-UTRs of the entire UniGene data base. The motif logo (graphic representation of the relative frequency of nucleotides at each position), as well as examples of the sequence alignment of six possible versions of the putative hnRNP A18 motif is shown in Fig. 2. Of the 51 nucleotides comprising the motif, six nucleotides located at positions 5, 13, 14, 19, 29, and 51 are invariant. The predicted secondary structure of this putative motif is complex and could comprise two large bulges, a long and a short stem as well as a short loop (Fig. 2C). A different version of the predicted motif as well as the motif found in RPA2 and TRX (two transcripts found in the data set) (11) are shown in Fig. 2B. The motif found in RPA2 is identical to the sixth version of the predicted motif. The data shown in Table 1 indicate that the signature motif is found in the 3′-UTR of 12 of the previously identified hnRNP A18-targeted transcripts and in several transcripts of the UniGene data base. As indicated, a number of transcripts contain more than one motif.

FIGURE 2.

A, probability matrix representing the relative frequency of each residue found at each position in the 3′-UTRs of the experimental data set. B, sequence alignment of six possible versions of the putative motif and motif found in RPA2, TRX, and ATR. Invariant nucleotides are in red boxes, and unmatched nucleotides are in italics. The position of the motif relative to the 3′-UTR start site is indicated in parentheses. C, predicted secondary structure of versions 1 and 6 of the putative hnRNP A18 motif.

TABLE 1.

hnRNP A18 motif location and score

Shown are the relative positions and scores (in parentheses) of the hnRNP A18 motif in the data set and in 12 examples from the UniGene data base. The position of the motif is relative to the 3′-UTR start site. RPA2, thioredoxin, and ATR have been validated.

| Motif position and score | Accession number | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Data set | ||

| 156 (18.01), 211 (0.61) | NM_002946 | RPA2 |

| 34 (0.9) | NM_003329 | Thioredoxin |

| 637 (33.73) | HsS3219161 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase |

| 271 (32.4) | HsS1726680 | eEF1A1 |

| 279 (6.67) | HsS3218967 | Nucleophosmin |

| 445 (0.32) | HsS1726315 | ATPase H+ |

| 45 (4.07) | HsS4001804 | Tubulin α |

| 230 (5.52) | HsS2139327 | HSPC023 |

| 204 (16.44) | HsS1730031 | RPL10 |

| 360 (2.06) | HsS1824519 | RPL13A |

| 54 (19.39), 398 (13.62), 1284 (2.90) | HsS1727678 | RPL15 |

| 92 (8.69) | HsS1727691 | RPL29 |

| UniGene data base | ||

| 150 (4.15) | HsS1726320 | ATR |

| 270 (6) | HsS1729523 | Polo-like kinase |

| 346 (11.85) | HsS5979230 | PIK3R4 |

| 549 (16.39) | HsS1732385 | Fragile X FXR2 |

| 1003 (16) | HsS1726736 | Fanconi anemia |

| 320 (29.85) | NM_138764 | Bax |

| 1126 (7.72) | HsS1726446 | CDK2 |

| 892 (15.1) | HsS2140172 | PAIP2 |

| 1786 (4.86) | HsS2293866 | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| 41 (3.29) | HsS3618391 | Cyclin B1 |

| 574 (0.5) | HsS3219213 | S100A14 |

| 130 (27.87) | HsS1727530 | 26 S proteasome |

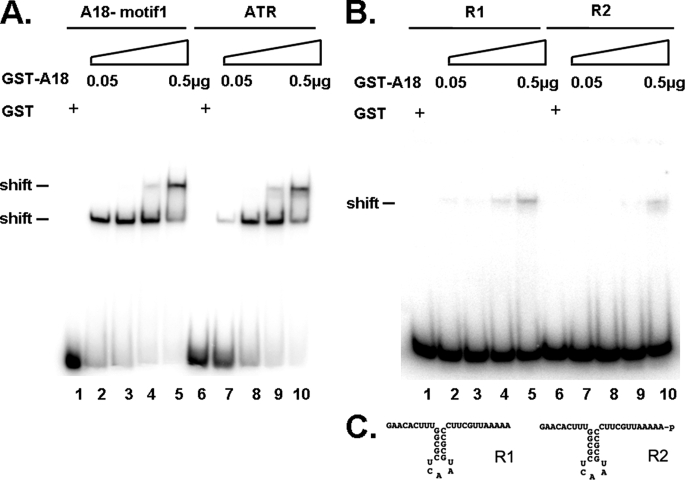

Validation of the predicted motif was performed by RNA band shifts of the predicted consensus sequence as well as the sequence from ATR 3′-UTRs (Fig. 3). The data in Fig. 3A indicate that hnRNP A18 binds similarly to both sequences with binding being observed with as little as 50 ng of recombinant protein (lanes 2 and 7). Increasing the amount of the recombinant protein gives rise to another RNA-protein complex of slower mobility. This may indicate that more than one molecule of protein can bind to the RNA or that, at a given ratio, the conformation of the protein and/or the RNA may be affected. The data shown in Fig. 3B indicate that the binding is specific because only marginal binding is observed at the highest concentration of recombinant protein with two unrelated probes. The sequences and predicted structures of the unrelated probes are indicated in Fig. 3C. In addition, specificity is also demonstrated by the inability of the recombinant GST protein to bind to the transcripts (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 6) and by the incapacity of hnRNP A18 to bind to 5′-UTR and open reading frame sequences (11). Detailed binding specificities have been provided previously for two of the data set targets, RPA2 and TRX (11), and here for the newly identified target ATR (see below).

FIGURE 3.

A, RNA band shift performed with increasing amounts of GST-hnRNP A18 (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 μg) and the hnRNP A18 motif version 1 (lanes 1–5) and the hnRNP A18 motif in ATR 3′-UTR (nucleotides 150–199, lanes 6–10). Recombinant GST (0.5 μg) was used as a negative control, and tRNA (50 μg/ml) was used as a nonspecific competitor. B, same as A with the exception that the R1 and R2 probes were used. C, sequence and predicted structures of the R1 and R2 RNA probes.

Functional Significance of an hnRNP A18 Signature Motif in the ATR 3′-UTR

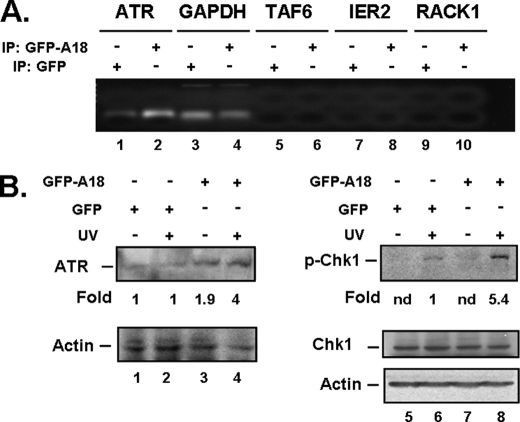

A search of the UniGene data base indicates that this putative hnRNP A18 motif is also found in the 3′-UTR of the ATR protein kinase (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Validation of this transcript as a bona fide hnRNP A18 target was performed by immunoprecipitation of hnRNP A18 bound to polysomes followed by RT-PCR. We used RKO cells stably transfected with GFP-hnRNP A18 to maximize the detection of the immune complex. The cells were exposed to UV radiation to translocate hnRNP A18 to the cytosol (Fig. 1), and the proteins were extracted 4 h later. Polysomes were then extracted under conditions that preserve the association of RNA-binding proteins with target mRNAs essentially as described before (14). After digesting the immunoprecipitated complex with proteinase K to release the hnRNP A18-bound mRNAs, the resulting products were amplified by RT-PCR. The data shown in Fig. 4A indicate that endogenous ATR can be amplified from the material immunoprecipitated with anti GFP-hnRNP A18 (lane 2) but not when nonspecific antibodies (lane 1) were used. To verify that equal amounts of input material were used in the RT-PCR, we also amplified glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA from both immunoprecipitated samples. Three times as much material was used to amplify glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the immunoprecipitates than to amplify ATR. Because ATR can only be amplified from polysomal fractions immunoprecipitated with GFP-hnRNP A18, we conclude that ATR mRNA is a bona fide target of hnRNP A18 in intact cells. The specificity of the binding was further demonstrated by amplifying TAF6, IER2, and RACK1, three nontargeted transcripts (lanes 6, 8, and 10). None of the nontargeted transcripts were amplified in the mRNA immunoprecipitated with the GFP-hnRNP A18-bound antibodies. Moreover, we also previously demonstrated that two other nontargeted transcripts, vascular endothelial growth factor and GADD45, could not be amplified from the hnRNP A18 immunoprecipitated polysomes (12).

FIGURE 4.

A, immunoprecipitation of polysomes was performed with the indicated antibody. IP was followed by RT-PCR (19 cycles) to detect endogenous ATR, TAF6, IER2, and RACK1 transcripts. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified from the same fractions to confirm that equal amounts of mRNA were present in each immunoprecipitated sample. Three times as much material was used to amplify glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as the other transcripts. B, Western blot analysis. RKO cells were stably transfected with either GFP or GFP-hnRNP A18 and exposed (+) or not (−) to UV radiation (14 Jm−2). The positions of Chk1, phosphorylated Chk1 (p-Chk1, Ser317), ATR, and actin are indicated. Fold induction were measured by densitometry and normalized to actin.

Our earlier studies have shown that hnRNP A18 binding to the 3′-UTR of targeted transcripts resulted in their increased translation (11). To verify the functional significance of hnRNP A18 binding to ATR transcripts on polysomes (Fig. 4A), we measured the levels of ATR protein in the presence of hnRNP A18 overexpression. The data shown in Fig. 4B indicate that indeed overexpression of hnRNP A18 resulted in increased ATR protein levels (lanes 3 and 4). To verify whether the overexpression of hnRNP A18 affected ATR activity, we also measured the phosphorylation level of Chk1, an ATR preferred substrate, in response to UV radiation (13). The data shown in Fig. 4B indicate that Chk1 phosphorylation levels increases in response to UV radiation (lane 2) as previously reported but increased markedly further when hnRNP A18 is overexpressed (lane 4). These data thus indicate that although hnRNP A18 overexpression can increase ATR protein levels, DNA damage is still required to activate its kinase activity.

DISCUSSION

Deregulation of protein translation is associated with a growing number of human diseases ranging from neurodegenerative diseases to tumorigenesis (18). Targeting components of the translational processes is therefore emerging as a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of these diseases. The identification of a specifically hnRNP A18-targeted RNA motif provides a new tool to regulate transcripts harboring this motif and offers the possibility of developing new mechanism based therapies. The identified hnRNP A18 signature motif is relatively large (51 nucleotides) compared with previously identified RNA-binding protein signature motifs (19). The predicted secondary structure indicates the proximity of two large bulges in addition to a long and a short stem as well as a short loop (Fig. 2C). This structure is markedly different from previously identified signature motifs and probably provides a basis for specificity. Along these lines it is interesting to note that the hnRNP A18 motif was not found in the Chk1 3′-UTR but that this transcript is recognized by TIAR, another RBP (20). The motif recognized by TIAR is predominantly cytosine-rich and presents a very different secondary structure composed of a short stem, a small bulge, and large and small loops. The increased levels of Chk1 phosphorylation observed in the presence of hnRNP A18 overexpression (Fig. 4B) is thus most likely mediated through increased ATR levels and activity. The complexity of the hnRNP A18 motif offers the possibility for several recognition and binding sites for the hnRNP A18 RNA-binding domain as well as the RGG boxes. In fact we have shown that both the RNA-binding domain as well as the RGG boxes are required to confer maximal RNA binding activity (12).

As has been reported for other RBPs (19–22), we also did not find that all previously identified hnRNP A18 targets contained the signature motif (Table 1 and Ref. 11). Several reasons including slight sequence variations within the probability matrix and the possibility that the RBPs recognize other less abundant motif within the data set have been proposed as possible explanation for this finding. Nonetheless, the identified hnRNP A18 motif is useful for the identification of bona fide target such as ATR. There is currently very little information regarding ATR regulation. Most of the information is at the post-translational levels and involved protein-protein interactions (23). Nonetheless, early reports have indicated the presence of alternatively spliced ATR and DNA-PKcs mRNA variants (24, 25) as well as extensive structural diversity within the 5′- and 3′-UTR of the ATM transcript (26). Post-transcriptional regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase family member transcripts had thus to be expected. One of the main challenges in studying ATR regulation is its requirement for the viability of replicating cells. Although deletion analyses are complicated by this requirement, ectopic activation has provided valuable information. For example, ectopic activation of ATR is sufficient to activate a G1 cell cycle checkpoint in ataxia telangiectasia fibroblasts even in the absence of DNA damage (5). Identification of a mechanism that could activate ATR in a timely fashion could thus be beneficial for cells lacking primary DNA damage responders such as ATM. The hnRNP A18 could provide such a mechanism, assuming that its interaction with ATR transcripts could be regulated.

Modulation of protein-RNA binding interactions are influenced by the “induced fit” behavior where each component of the complex can affect the conformation of the other independently or concomitantly (27). Although hnRNPA 18 binding to unstructured RNA cannot be ruled out it seems unlikely because hnRNP A18 binds to at least three different targets (RPA, TRX, and ATR) with different sequences but similar motif and does not bind to simple stem loop structures (Fig. 4B) (11) (12). Alternatively, regulation of the interaction can be mediated through post-translational modification. As mentioned earlier we have previously shown that phosphorylation of hnRNP A18 by GSK3β increased its RNA binding activity (12). Given the unique substrate specificity of GSK3β and its requirement for an initial priming kinase (17), we investigated whether GSK3β or CK2 could be involved in hnRNP A18 translocation. Our data (Fig. 1, B–F) indicate that inhibition of CK2 or GSK3β significantly reduced hnRNP A18 translocation in response to UV radiation. Although CK2 seems to be the predominant kinase involved in hnRNP A18 translocation, it does not affect its RNA binding activity (12). It thus appears that the GSK3β sites are involved in RNA binding activity, and the CK2 sites are used for translocation in response to UV radiation. Nonetheless, given the particular nature of the GSK3β substrate specificity, both kinases most likely contribute to hnRNP A18 translocation in response to UV radiation.

Cytosolic translocation of hnRNP A18 is not unique to UV radiation but also occurs in response to hypoxia (data not shown). GSK3β, CK2, and ATR are all induced by hypoxia (17), (28, 29). It thus seems likely that under hypoxic conditions, which occur in virtually all solid tumors (30), hnRNP A18 could be phosphorylated by GS3Kβ and CK2, translocates to the cytosol, and activates ATR. The role of ATR in hypoxic cells is to protect the stalled replication fork. It is interesting to note that several hnRNP A18 potential targets are responsive to oxidative stress (11). This observation is in good agreement with the recently described RNA regulon model where a group of mRNA transcripts is coordinately regulated at the post-transcriptional level by a given RBP (31). The overall effect of hnRNP A18 is increased survival in response to cellular stress (11). Our general assumption is that hnRNP A18 can increase survival by regulating the translation of transcripts involved in the cellular response to DNA damage (11). Alternatively, hnRNP A18 could mediate its cytoprotective effect through other mechanisms. For example hnRNP A18 could increase cell survival in response to stress by inhibiting apoptosis or indirectly increasing repair. A direct involvement in the repair pathways seems unlikely because repair components have been isolated and characterized and do not include hnRNP A18 (32). hnRNP A18 could influence apoptosis through stabilization of transcripts such as TRX (12). TRX promotes the degradation of the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 and inhibits apoptosis (33). A balance between the up-regulation of repair proteins such as RPA and ATR and inhibition of apoptosis is thus likely to account for the hnRNP A18-mediated increase in survival (11).

In summary, we have identified an hnRNP A18 signature RNA motif that is present in the ATR 3′-UTR mRNA. Binding of hnRNP A18 to ATR transcript increases ATR protein levels and activity in response to cellular stress. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a post-transcriptional mechanism to regulate ATR activity. hnRNP A18 could thus become a new target to trigger back-up stress response mechanisms such as ATR to functionally compensate for absent or defective responders.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Stuart Martin for technical assistance with confocal microscopy.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 GM57827 and RO1 1CA116491-01 (to F. C.). This work was also supported by funds from the graduate program in biochemistry of the University of Maryland, Baltimore (to R. Y.).

- ATR

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- hnRNP

- heterogenous ribonucleoprotein

- UTR

- untranslated region

- DNA-PKcs

- DNA-dependent protein kinase

- RPA

- replication protein A

- RBP

- RNA-binding protein

- CK

- casein kinase

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- SCFG

- Stochastic context-free grammar

- TRX

- thioredoxin

- RT

- reverse transcription.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shiloh Y. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham R. T. (2004) DNA Repair 3, 919–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuadrado M., Martinez-Pastor B., Fernandez-Capetillo O. (2006) Cell Division 1, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mordes D. A., Glick G. G., Zhao R., Cortez D. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1478–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toledo L. I., Murga M., Gutierrez-Martinez P., Soria R., Fernandez-Capetillo O. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 297–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fornace A. J., Jr., Alamo I., Jr., Hollander M. C. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U..S.A. 85, 8800–8804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheikh M. S., Carrier F., Papathanasiou M. A., Hollander M. C., Zhan Q., Yu K., Fornace A. J., Jr. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26720–26726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krecic A. M., Swanson M. S. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyfuss G., Matunis M. J., Piñol-Roma S., Burd C. G. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 289–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellmann S., Bührer C., Moderegger E., Zelmer A., Kirschner R., Koehne P., Fujita J., Seeger K. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 1785–1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C., Carrier F. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47277–47284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R., Weber D. J., Carrier F. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1224–1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q., Guntuku S., Cui X. S., Matsuoka S., Cortez D., Tamai K., Luo G., Carattini-Rivera S., DeMayo F., Bradley A., Donehower L. A., Elledge S. J. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1448–1459 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenenbaum S. A., Lager P. J., Carson C. C., Keene J. D. (2002) Methods 26, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Houven van Oordt W., Diaz-Meco M. T., Lozano J., Krainer A. R., Moscat J., Cáceres J. F. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149, 307–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habelhah H., Shah K., Huang L., Ostareck-Lederer A., Burlingame A. L., Shokat K. M., Hentze M. W., Ronai Z. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim L., Kimmel A. R. (2000) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheper G. C., van der Knaap M. S., Proud C. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 711–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López de Silanes I., Zhan M., Lal A., Yang X., Gorospe M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U..S.A. 101, 2987–2992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H. S., Kuwano Y., Zhan M., Pullmann R., Jr., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Li H., Kedersha N., Anderson P., Wilce M. C., Gorospe M., Wilce J. A. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6806–6817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López de Silanes I., Galbán S., Martindale J. L., Yang X., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Indig F. E., Falco G., Zhan M., Gorospe M. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9520–9531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazan-Mamczarz K., Kuwano Y., Zhan M., White E. J., Martindale J. L., Lal A., Gorospe M. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 204–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cimprich K. A., Cortez D. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 616–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannino J. L., Kim W., Wernick M., Nguyen S. V., Braquet R., Adamson A. W., Den Z., Batzer M. A., Collins C. C., Brown K. D. (2001) Gene 272, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connelly M. A., Zhang H., Kieleczawa J., Anderson C. W. (1996) Gene 175, 271–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savitsky K., Platzer M., Uziel T., Gilad S., Sartiel A., Rosenthal A., Elroy-Stein O., Shiloh Y., Rotman G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1678–1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williamson J. R. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 834–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluemsampant S., Safronova O. S., Nakahama K., Morita I. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 122, 333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond E. M., Dorie M. J., Giaccia A. J. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 6556–6562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammond E. M., Giaccia A. J. (2004) DNA Repair 3, 1117–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keene J. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 533–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelley M. R., Fishel M. L. (2008) Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 8, 417–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y., Min W. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, 1259–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]