Abstract

The rate-determining step in the overall turnover of the bc1 complex is electron transfer from ubiquinol to the Rieske iron-sulfur protein (ISP) at the Qo-site. Structures of the ISP from Rhodobacter sphaeroides show that serine 154 and tyrosine 156 form H-bonds to S-1 of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and to the sulfur atom of the cysteine liganding Fe-1 of the cluster, respectively. These are responsible in part for the high potential (Em,7 ∼300 mV) and low pKa (7.6) of the ISP, which determine the overall reaction rate of the bc1 complex. We have made site-directed mutations at these residues, measured thermodynamic properties using protein film voltammetry to evaluate the Em and pKa values of ISPs, explored the local proton environment through two-dimensional electron spin echo envelope modulation, and characterized function in strains S154T, S154C, S154A, Y156F, and Y156W. Alterations in reaction rate were investigated under conditions in which concentration of one substrate (ubiquinol or ISPox) was saturating and the other was varied, allowing calculation of kinetic terms and relative affinities. These studies confirm that H-bonds to the cluster or its ligands are important determinants of the electrochemical characteristics of the ISP, likely through electron affinity of the interacting atom and the geometry of the H-bonding neighborhood. The calculated parameters were used in a detailed Marcus-Brønsted analysis of the dependence of rate on driving force and pH. The proton-first-then-electron model proposed accounts naturally for the effects of mutation on the overall reaction.

Keywords: Bioenergetics/Electron Transport, Cytochromes/Cytochrome b, Enzymes/Mechanisms, Mutagenesis Mechanisms, Electron Transfer, HYSCORE Spectroscopy, Marcus-Bronsted, bc1 complex, Proton-coupled Electron Transfer

Introduction

Enzymes of the cytochrome bc1 complex2 family (EC 1.10.2.2) are ubiquitous membrane proteins in mitochondria and bacteria (and, including the b6f complex, in chloroplasts) that play a central role in the electron transfer chains of respiration and photosynthesis. In Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the bc1 complex, together with the reaction center (RC) and cytochrome (cyt) c2, forms the photosynthetic chain. The complex catalyzes oxidation of substrate ubiquinol (QH2) by a water-soluble ferricytochrome c2 in the periplasmic space and generates a proton-motive force for ATP synthesis through a Q-cycle mechanism (1, 2). With the availability of structures from mitochondrial and bacterial systems (3–8), the mechanism could be further refined. Proteins of the bc1 complex family form homodimers inserted in the cellular or mitochondrial membrane, each monomer containing minimally the three subunits (cyt b with two b-type hemes (bH and bL), cyt c1 with heme c1, and Rieske-type iron-sulfur protein (ISP)) that form the catalytic core of the complex. The α-proteobacterial ancestors of mitochondria were likely derived from photosynthetic progenitors, accounting for the high degree of homology in sequence, structure, and mechanism. The bacterial structures are much simpler than the 8–11 subunit complexes in mitochondria. The isolated complex has four subunits in each monomer (cyt b, cyt c1, ISP, and subunit IV) (9, 10), but crystallographic structures of the bc1 complex from Rhodobacter species show only the three catalytic subunits (6, 7), leaving some uncertainty as to the role of subunit IV. The R. sphaeroides system provides a convenient model for mitochondrial systems because flash activation through the RC initiates turnover, and kinetics can then be measured spectrophotometrically. In addition, the catalytic core (ISP, cyt b, and cyt c1) is encoded on an operon expressed from a single promoter, which allows for easy genetic manipulation (11).

The bc1 complex contains two quinone-binding sites, Qo and Qi, which catalyze the redox chemistry of ubiquinone. At the Qo-site, the first electron transfer from the QH2 to the high potential chain (ISP, cytochrome c1, and c2) is the rate-limiting step in the overall reaction (12–16). It is driven by the work available from the redox difference between QH2 (Em,7 ∼90 mV) and the high potential chain (Em,7 ∼300 mV for ISP). The oxidized ISP acts as the acceptor on QH2 oxidation, in a proton-coupled electron transfer, and this step was shown to include the high activation barrier for QH2 oxidation. The dependence of the reaction rate on the Em and ΔpKa values of the redox partners is complex (14, 16–18) and is the main topic explored in this paper. After the first electron and proton transfer, the second electron is transferred from the intermediate semiquinone to a low potential chain composed of two b-type hemes (bL and bH), which reduce the quinone (Q) at the Qi-site by electrogenic electron transfer across the membrane. The second proton exits the Qo-site, probably via Glu-295 and a water chain to the P-phase (19). The redox reactions at the Qo- and Qi-sites release protons to the periplasmic space or take them up from the cytoplasm, respectively, so that, overall, two protons per QH2 oxidized are pumped across the membrane to generate a proton-motive force that drives ATP synthesis.

All Rieske-type iron-sulfur clusters consist of a [2Fe-2S] core with two histidines as ligands to one iron and two cysteines as ligands to the other (Fig. 1) (20–22), and both irons are in their FeIII state in the oxidized protein. The [2Fe-2S] cluster of the ISP has a net charge of 0 or −1 for the oxidized and reduced forms, respectively. From sequence difference, and the wide range of potentials in other [2Fe-2S] clusters, it is clear that the redox properties of the cluster are affected by protein environment (23–27). When sequences from bacterial species with different substrates are aligned, differences at particular positions can be correlated with the difference in the redox properties of the cluster and used to guide selection of sites for mutagenesis (15, 24–26, 28). The first crystallographic structure (29) showed that the cluster is surrounded by additional electron-withdrawing residues, among them Ser-154 and Tyr-156 (as numbered in the R. sphaeroides enzyme). Ser-154 forms an H-bond to the S-1 atom of the cluster, whereas Tyr-156 H-bonds to the Sγ of the side chain of Cys-129, a cysteine ligand (Fig. 1). These two residues thus contribute substantially to the electronegativity responsible for the high potential (Em ∼300 mV in mitochondria and α-proteobacteria (30)) and low pKa values (30–32). Strains mutated at these and several other residue positions were produced in the bc1 complex from R. sphaeroides (24, 28), Paracoccus denitrificans (25), and in yeast (26). From the variation in rate with driving force, each of these laboratories suggested that the first electron transfer must control the overall rate of QH2 oxidation. However, any kinetic scheme in which this is the limiting step would show this property. Consideration of the role of changes in pK introduced an additional constraint on the mechanism (15). In the work of Klingen and Ullmann (21), the pKa values of Rieske iron-sulfur clusters of bc-type and ferredoxin-type were calculated using density functional theory/electrostatic approaches based on the protein environment, and they suggested that the high Em and low pKa values in the former were largely determined by hydrogen bonding from these and other groups around the cluster.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic hydrogen-bonding network of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the surrounding amino acids residues. Ser-154 and Tyr-156 are two mutagenesis targets in this study, and the hydrogen atoms binding to the two Nϵ positions of the histidines are likely the two involved in deprotonation (pKox1 and pKox2) (14–17).

In this study, we describe construction of mutant strains in R. sphaeroides altered in these hydrogen-bonding residues, including S154C as a functional mutant that has not been previously reported. We evaluate electrochemical parameters and analyze the driving forces that determine the rate of the first electron transfer reaction in the bc1 complex. The redox midpoint potentials (Em values) of the mutant ISPs were measured in the intact complex using CD spectroscopy at pH 7.4 and, over a pH range from 4 to 14, using protein film voltammetry of the isolated subunit (33) to identify pK values. The proton environment was explored by ESEEM spectroscopy to identify H-bonds lost in two mutant strains. Dependence of the rate of QH2 oxidation on pre-steady state conditions at the Qo-site was determined in chromatophores, using kinetic spectrophotometry after flash excitation. Redox poising was used to control the degree of reduction of the quinone pool (12, 34) or variation of the pH in the physiological pH range (pH 5.5–10) to change the concentration of the imidazolate (substrate) form of oxidized ISP [ISPox] while keeping [QH2] constant (14). This manipulation of the driving force of the reaction provided results allowing analysis of the “proton-first-then-electron” (PT/ET) mechanism proposed in the context of a Marcus-Brønsted (16) model and a deeper understanding of the dependence of electron transfer on these characteristics.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Genetics Protocols

Plasmid vectors, growth conditions, and site-directed mutagenesis protocols were conventional and are describe in detail in the supplemental material.

Preparation of Chromatophores, Purification of the Mutant bc1 Complexes, and Isolation of Their ISPs

Chromatophores were prepared essentially as described previously (12, 14). They were also used as an enriched source of the bc1 complex protein, which was purified essentially as described by Guergova-Kuras et al. (10), by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column chromatography (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) of the complex with a His6 tag at the C terminus of the cyt b subunit. The final eluant from the column was concentrated and redissolved in 50 mm MOPS, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgSO4, 0.01% n-decyl-β-d-maltoside, 15 μg/ml phosphatidylcholine (pH 7.0). The purified mutant proteins were stored for future use at −80 °C after adding glycerol to a final concentration of 20% (w/v).

Two different preparations of the ISP were used, a proteolyzed iron-sulfur protein fragment, used in spectroscopic (35) and structural studies (8), and an intact subunit, used for protein film voltammetry because it adhered better to the graphite electrode (33). The subunit from the mutant bc1 complexes was extracted using a modification of the alkaline extraction protocol, because the stability at high pH of mutant ISP was lower than that of wild type. To separate subunits of the bc1 complex, the concentrated protein sample was diluted in a solution containing 2.5 mm TAPS and 0.01% dodecyl maltoside at pH 9.5. The diluted sample was filtered in a Centriplus® centrifugal concentrator with a cutoff of 100 kDa and, after dilution in ⅓ volume of 25 mm sodium phosphate buffer with 2 m NaCl, the ISP-containing filtrate was then concentrated in a Centriplus® concentrator with a cutoff of 30 kDa. All fractions were checked by gel electrophoresis on SDS-polyacrylamide for purity (data not shown).

CD Spectroscopy

CD spectroscopic data were obtained using a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter as described previously (32). The purified bc1 protein was diluted at 2 μm in the 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mm EDTA, 0.8 m sucrose, 0.01% dodecyl maltoside, and appropriate redox mediators (32). The poised potential in the measuring chamber was controlled by adding sodium hydrosulfite or potassium ferricyanide. The CD difference spectra obtained were fitted to a Gaussian curve with the peak at 500 nm and a width at the half-height of 30 nm. The relative concentration of reduced ISP was calculated by the difference in the fitted plot at 500 and 470 nm. The Em value of the ISP was estimated from plots of relative concentration as a function of the ambient potential (Eh) and fitted to a Nernst equation with z = 1 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Redox titrations of the bc1 complex to determine the Em values of ISP by CD. The redox states of the ISPs (■, wild type; and mutant strains: ●, S154T; ▴, S154C; ▾, S154A) were monitored from the difference in CD spectrum at 500 and 470 nm as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The plots were normalized for the total amplitude of the difference between fully oxidized state and fully reduced state. SHE, standard hydrogen electrode.

Protein Film Voltammetry

The redox midpoint potentials of the isolated mutant ISPs were estimated by protein film voltammetry (33). The protein samples were spread on the polished surface of a pyrolytic graphite electrode, which was then placed in an all-glass cell containing appropriate medium, saturated with nitrogen gas to maintain anaerobic conditions. The reversible cyclic voltammograms were recorded via a CV27 voltammeter (Bioanalytical Systems Inc., West Lafayette, IN) in buffers of various pH values in the range 4 to 14, and the peak positions obtained in both directions were averaged to obtain Em values. The position of each peak was determined with the help of the algorithm of the “peak fitting module” in OriginPro® 7.5 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA).

Pre-steady State Kinetic Experiments to Determine Reaction Parameters of the Mutant Strains

The activities of the bc1 complex of wild type and mutant strains were measured by flash-induced kinetics of cytochromes, RC, and electrochromic absorbance changes in chromatophores (14, 36). For most experiments, the reactions were triggered by a single ∼90% saturating actinic flash that activated the RC to generate the substrates of the bc1 complex, and the subsequent turnover of the Qo-site in the presence of 10 μm antimycin A was measured from initial rates of reduction of the cyt bH through the difference kinetics at ΔA561–569. Reactant concentrations were varied by changing the pH or redox poise in a closed anaerobic reaction cuvette, flushed with water-saturated argon gas. The chromatophores were diluted to give a RC concentration of ∼0.5 μm in a reaction medium (usually 100 mm KCl, 50 mm MOPS, buffered at pH 7.0) containing appropriate redox mediators (5 μm each of phenazine ethosulfate, N-ethylphenazonium ethosulfate, phenazine methosulfate, N-ethylphenazonium methosulfate, and diaminodurene, 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine), ionophores to collapse the proton gradient (2 μm each of nigericin and valinomycin), and 0.5 mm FeNa(EDTA)2 as redox buffer. In some experiments, 2 mm KCN was included as a control for initial experiments in which ascorbate and KCN were added under aerobic conditions to give an approximate Eh for the Q-pool at ∼140 mV. The KCN served to inhibit oxidation of cyt c2 through oxidase activities. However, the added KCN affected neither redox poise nor the measured kinetic under the anaerobic conditions of the redox poised experiments. The ambient redox potential was monitored, and potentials were adjusted by adding potassium ferricyanide or sodium hydrosulfite (dithionite).

The pH dependence of the pre-steady state kinetics was determined essentially as described above, but with the following modifications. Chromatophores were diluted in buffers at different pH (100 mm KCl with one of the following: 50 mm MES for pH 5.5–6.5; MOPS for pH 7; EPPS for pH 7.5–8.5; CHES for pH 9–10), and the ambient potential was adjusted to take account of the pH dependence of the Q/QH2 couple so as to keep the quinone pool poised at the same ratio. Values over a range between ∼30% reduced (equivalent to Eh ∼100 mV at pH 7.0) and ∼85% reduced (equivalent to Eh ∼70 mV at pH 7.0) were tested in preliminary experiments (see supplemental Fig. S1). For comparison between mutant strains, we used conditions under which the Q-pool was 83% reduced. Under these conditions, the rate of QH2 oxidation was near maximal, and heme bH was mostly oxidized (∼76%). This protocol allowed for control of QH2 concentration while varying [ISPox], which changed with pH. The kinetic activities in the pH range below 8.5 were measured via the absorbance change due to cyt bH (as above). In higher pH ranges (≥8.5), because the Em of heme bH and the Q-pool overlap more (37), the kinetics were determined through electrochromic changes of carotenoids at 503 nm and were monitored in the absence of ionophores and antimycin A (12, 36).

Stigmatellin Titrations

The titration curve for stigmatellin inhibition of the bc1 complex was determined by measuring cyt bH reduction with the suspension at Eh ∼100 mV as above, by following the change in amplitude with increasing concentrations of the inhibitor on flash activation in the presence of antimycin A.

Calculation of Apparent Km Values for QH2

Michaelis-Menten treatment of the dependence of the Qo-site reaction on [QH2] was based on the known Em value for the Q/QH2 couple, the total [Q + QH2], the Q/QH2 value calculated at each experimental Eh, and allowance for ∼1 QH2/2 RC generated in the flash. Values used in this analysis were an Em,7 for the Q/QH2 couple of 90 mV in R. sphaeroides (38), and a ratio between the quinone pool and the RC of ∼30 Q/RC determined through quinone extraction and kinetic approaches (12, 34). It was assumed that this ratio would be constant for all the mutant strains because there is no genetic interference in the expression of the RC and quinone synthesis in the strains used in this work. However, because all the bc1 complexes in this work were expressed trans-allelically, and cells were grown under tetracycline selection, the stoichiometries of redox components varied somewhat. To control for this, ratios of bc1 complex to RC were determined from the absorbance change of RC, and hemes bH, bL, and (c1 + c2) in kinetic experiments following excitation by 8 closely spaced flashes in the presence of 1 mm ascorbic acid (as reductant for the high potential chain), 2 mm KCN to inhibit cyt c2 oxidation through oxidase activities, and 10 μm antimycin to block reoxidation of the b-hemes. The concentrations of reduced QH2 and the bc1 complex in the membrane before flash activation were obtained assuming [RC]membrane of ∼2 mm (34) and by substituting values for reactants into the Nernst equation. We then used values for [QH2] at different ambient potentials in Hanes-Woolf plots to estimate Km and Vmax values. The Km values reported ignore possible competitive effects from changes in [Q] (39, 40) and are therefore reported as apparent values derived empirically and applied relatively.

EPR and ESEEM Spectroscopy

Protocols for X-band (∼9.5 GHz) EPR and ESEEM spectroscopy and sample preparation were essentially the same as those reported previously (41). All experiments were performed using the soluble ISP fragment purified after controlled proteolytic digestion of the bc1 complex, which released the extrinsic mobile domain from its membrane anchor by hydrolysis in the linker region.

RESULTS

Characteristics in the Growth of the Mutant Strains

Five mutant strains of R. sphaeroides, in which Ser-154 from the ISP was replaced by threonine, cysteine, alanine, glycine, or tyrosine (S154T, S154C, S154A, S154G, and S154Y, respectively), have been newly constructed, and previously prepared mutant strains on the Tyr-156 residue (Y156F, Y156H, Y156L, and Y156W) (15) were used for a detailed analysis of the role of these residues in fine-tuning the potential of the [2Fe-2S] cluster.

The nine R. sphaeroides strains containing the pR− series plasmids (see supplemental Table S1) were grown in anaerobic Sistrom's media with light. Only S154T, S154C, Y156F, and Y156W strains could grow well enough to produce a reasonable amount of chromatophore under photosynthetic conditions. Other mutant strains were cultured in anaerobic Sistrom's medium with 60 mm DMSO as an additional electron acceptor in photosynthetic circuit. Strains S154A, S154T, and S154C, and Y156F and Y156W produced a functional ISP. All other mutants (S154G, S154Y, Y156H, and Y156L) died or were found on analysis of DNA after harvesting to have reverted spontaneously, usually to wild type.

Despite many efforts, we failed to generate bc1 complex containing ISP with the mutations Y156H and Y156L as reported previously (42). We concluded that their functional “Y156H” strain (which showed wild type characteristics) was likely a mutant that had reverted to WT during growth from mutant stocks. In our hands, Y156L spontaneously converted to Y156F, and we think it likely that the data previously obtained for “Y156L” represented those of Y156F.

Em Values of ISP in the bc1 Complex of Mutant Strains and CD Spectroscopy

The characteristic UV-visible absorption spectra of ISP are due to a large number of overlapping S → Fe(III) charge-transfer bands (43), which are broad and have weak extinction coefficients for the ISP (≤ ∼20 m−1 cm−1, depending on the redox states of ISP (31, 44), unsuitable for measurement of the redox state. A direct method to measure the redox states of ISP under natural conditions is through circular dichroism, because the reduced [2Fe-2S] cluster produces a specific broad circular dichroic change in the visible light range (15, 32, 44). The differential spectrum of reduced minus oxidized ISP shows a negative change at 500 nm with a half-width of 30 nm (15).

In situ redox potential (Em) titrations of Ser-154 variants were therefore determined in the intact bc1 complex by CD at a physiological pH (pH 7.4), and Fig. 2 shows the titration curves of the redox state of ISPs from three Ser-154 mutant strains and WT bc1 complexes. The variations of amplitude of the CD spectra of (500 to 470 nm) were plotted against the ambient potential in the range of 100–400 mV at pH 7.4 and fitted to a Nernst equation with z = 1 at 20 °C.

The Em values of the mutant ISP were similar to those reported previously (15, 26). The WT ISP had Em of 303 mV, and S154T showed an ∼40 mV lower value than WT. The ISP of S154A showed ∼130 mV downshift of Em at pH 7.4. Interestingly, the Em of S154C, the strain that has not been reported as functional before, showed slightly higher (∼10 mV) redox mid-potential than WT (Table 1), which we discuss more extensively below.

TABLE 1.

Electrochemical parameters measured by CD or protein film voltammetry

| Strains | Em values from CD spectra/mV | Protein film voltammetry |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eacid/mV | Ebase/mV | pKox1 | pKox2 | pKred1,2 | ||

| Wild-type/BH6a | 303 ± 4b | 308 ± 3 | −134 ± 6 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 9.6 ± 0.1 | 12.4 ± 0.4 |

| 312 ± 5c | ||||||

| S154T | 260 ± 5b | 288 ± 3 | −151 ± 7 | 7.71 ± 0.14 | 9.32 ± 0.15 | 12.2 ± 0.1 |

| S154C | 313 ± 5b | 324 ± 4 | −97 ± 6 | 7.17 ± 0.11 | 9.77 ± 0.13 | 12.0 ± 0.1 |

| S154A | 167 ± 6b,d | 178 ± 4 | −239 ± 10 | 8.06 ± 0.15 | 9.89 ± 0.17 | 12.5 ± 0.1 |

| Y156F | 256 ± 4c,d | 252 ± 4 | −165 ± 6 | 7.76 ± 0.15 | 8.83 ± 0.21 | 11.8 ± 0.1 |

| Y156W | 198 ± 3c,d | 208 ± 3 | −228 ± 4 | 7.87 ± 0.09 | 9.25 ± 0.11 | 12.2 ± 0.1 |

a The wild type strain in this work is derived from R. sphaeroides BC17 (Δfbc), with the fbc operon on plasmid pRK415, modified so as to encode a histidine tag at the C terminus of the cyt b gene (BH6). The CD data were obtained using the isolated bc1 complex and the protein film voltammetry data using the isolated ISP subunit. The protein film voltammetric data of the wild-type was reported in Ref. 8, and preliminary values were reported in Ref. 33.

b The values were measured as in Fig. 2 at pH 7.4.

c The data represent the limiting value for Em at pH ≪ pK1, as described in Ref. 33.

d The data for R. sphaeroides are similar to those shown for an engineered bovine ISP fragment (50).

In the data previously obtained using CD, the Tyr-156 mutant ISPs were titrated in the pH range of 5–10, and Em values at the acidic end of the range and the pKa values of the oxidized form were calculated (15). However, titration in situ in the higher pH range (pH > 10) suffers because of loss of integrity of the bc1 complex. For this reason, the Ser-154 mutants were analyzed, and the Tyr-156 mutants were re-evaluated, using the protein film voltammetry technique (45), and results are compared with previous data on the Tyr-156 mutants in Table 1.

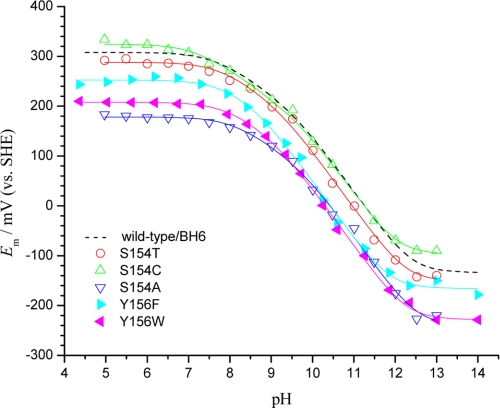

pH Titration of Isolated ISP Using Protein Film Voltammetry

The redox midpoint potential of ISP varies with ambient pH (30, 31, 46). Fourier transform infrared spectrometry studies have shown in the Rhodobacter capsulatus ISP that the pK values are associated with histidines (47). In the Rieske protein of Thermus thermophilus, with a similar structure in the cluster-binding domain (Fig. 1), 15N NMR studies of protein labeled specifically in histidine residues (48) have demonstrated that the pH dependence of chemical shifts correlates with the protonation state of the histidines equivalent to His-131 and His-152, characterized by the pKa values determined from redox titration. A more recent spectroscopic analysis (49) reached the same conclusion. Because these histidines are the ligands to the [2Fe-2S] cluster and are exposed to solution, the ISP can directly exchange electrons with an electrode, allowing application of voltammetric methods. In addition, at high pH, the isolated ISP is more stable than the whole complex. Link et al. (46) used cyclic voltammetry and CD (31) to measure the Em values of bovine ISP over a range of pH up to 11. Zu et al. (33, 45) and Leggate and Hirst (50) extended the approach by using protein film voltammetry, which allowed exploration of a higher pH range to cover the pKa values of both oxidized (ISPox) and reduced ISP (ISPred). They suggested Equation 1,

|

A similar equation referred to Eacid was used in Ref. 50. Data over the range from pH 4 to 14 were analyzed using this approach, with essentially identical fits with either equation. Fig. 3 shows plots for dependence of Em on pH for Ser-154 and Tyr-156 mutant strains, with the data fitted to Equation 1. The best fit solutions are summarized in Table 1. The Eacid experimental values were well fit by calculation from Ebase and the four pK values of the equation, to provide the values in Table 1. The Eacid values match the data from Guergova-Kuras et al. (15) and the CD titrations reported above, within experimental error, and are also similar to the values reported using protein film voltammetry on S163A, Y165F, and Y165W engineered in bovine ISP fragments expressed in E. coli (50).

FIGURE 3.

Measurement of thermodynamic parameters for redox characteristics of ISP using protein film voltammetry. The redox midpoint potentials (Em) of the S154T (○), S154C (▵), S154A (▿), Y156F (▶), and Y156W (◀) were calculated by averaging the peak potentials of the reversible cyclic voltammograms and titrated in the pH range of 4–14. The dashed line for the wild type is from Zu et al. (33); other curves were calculated using Equation 1 or the Eacid-based equivalent equation from Ref. 50, which gave the same fit. SHE, standard hydrogen electrode.

Taken together with structural data, a preliminary conclusion is that electron-withdrawing groups around the [2Fe-2S] cluster are essential for the potential of the cluster. The S154T and S154C showed only ±20 mV separation in the Eacid values from WT, whereas in other mutants the value was shifted down by more than 50 mV. In the case of S154A, the downshift was 135 mV in the more acidic range. The positive shift in Em of S154C under acidic conditions (pH < 7) in this experiment was similar to that seen in the CD titration. This mutant also showed a more negative shift in the first pKa value of the ISPox (pKox1) than for other single mutations reported at this site.

The second feature of these titrations is the correlation between pKox1 and Eacid. We therefore investigated the effects of these two parameters in the reaction of the intact bc1 complex, because the Em and the pKox1 values are the components contributing determinants for the rate of the first electron transfer reaction.

Pre-steady State Kinetic Measurements for the Mutant Strains and Titration of Rate as a Function of pH and Eh

The mobility of the extrinsic domain of ISP determines that it behaves as a tethered diffusible substrate in the reaction at the Qo-site (4, 16, 17). In formation of ES complex involved in the first turnover of the enzyme, two substrates, QH2 and the dissociated ISPox, are involved. Binding of both substrates at the Qo-site involves formation of an H-bond between them, the free energy of which results in a tighter binding of QH2 from the pool (giving a displacement of the apparent Em for QH2 oxidation from that of the quinone pool) and recruitment of the imidazolate form of ISPox (leading to an apparent shift of pKa in the kinetic experiment from that of ISPox seen in redox titrations). From these displacements, the relative binding constants for the two substrates can be estimated in the different strains (16, 17).

The shifts in apparent pKa for the mutant ISPs were measured over the pH range 5.5–10.0. (Fig. 4), with the substrate QH2 kept constant and close to saturating (see under “Experimental Procedures”). Under these conditions, when plotted as a function of pH, the rate of QH2 oxidation showed a bell-shaped curve, with a maximum in the range 7.5–9.0 (depending on strain). The amplitude at each pH reflected the fraction of the ISPox in the active form. The observed curves could be characterized using Equation 2, determined by the dissociation constants of two groups (51).

|

FIGURE 4.

Dependence on pH of Qo-site turnover. The activities of the mutant bc1 complex were titrated by measuring the cyt bH reduction rates (ΔA 561–569 nm) in the presence of antimycin A in the range of pH 5.5–8.5 (the filled symbols) and the electrogenic processes from electrochromic changes of carotenoids (ΔA 503 nm) at pH > 8.5 (the outlined symbols) after flash initiation of the reaction. The reaction conditions are described under the “Experimental Procedures.” The pH dependence from titration data were fitted to the equation suggested by Brandt and Okun (51), and the estimated parameters are given in Table 2. ■, wild type; ●, S154T; ▴, S154C; ▾, ▿, S154A; ▶, Y156F; ◀, ◁, Y156W.

Brandt and Okun (51) had suggested that the two groups might correspond to the two pK values of the oxidized ISP (pKA and pKB), but in our hands the lower value is substantially shifted from pKA, reflecting the displacement discussed above. When comparing the apparent pKA values from the kinetic experiments with the pKox1 values from protein film voltammetry (so as to estimate the binding constants (KISPox) in Table 2), the change in apparent pKA followed the variation of the pKox1, but the changes in KISPox were minor. The largest change in the S154A variant showed about a 3-fold decrease. The optimal reaction rate (Vopt) of each mutant correlated with its Eacid value, except in S154C, where the maximal rate was slower than WT (although the Eacid was higher), which is likely caused by the lowered pKox1 value. We used the Em and pKa values in a more detailed analysis of electron transfer through a Marcus-Brønsted analysis (16, 18), as discussed later.

TABLE 2.

Affinity of the imidazolate form of ISPox for the Qo-site occupied by QH2 or stigmatellin

ND means not determined.

| Strains | Kinetic titration at 83% reduced quinone poola |

Association of ISPox at Qo-siteb |

Stigmatellin inhibition, I50 or (Ka)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pKA | pKB | Vopt | ΔpKfree-bound | KISPox | KISPox | ||

| % | |||||||

| Wild-type/BH6 | 6.66 ± 0.10 | 9.14 ± 0.26 | 973 | 0.94 | 8.7 | 100 | 0.585 (68.0) |

| S154T | 6.83 ± 0.12 | 8.48 ± 0.14 | 826 | 0.87 | 7.4 | 85 | 2.39 (8.14) |

| S154C | 6.29 ± 0.05 | 8.46 ± 0.06 | 804 | 0.88 | 7.6 | 87 | 2.309 (2.63) |

| S154A | 7.52 ± 0.20 | 10.2 ± 0.28 | 199 | 0.49 | 3.1 | 35 | 2.57 (3.61) |

| Y156F | 6.77 ± 0.06 | 8.63 ± 0.08 | 634 | 0.99 | 9.8 | 110 | ND |

| Y156W | 6.97 ± 0.08 | 9.69 ± 0.12 | 243 | 0.92 | 8.3 | 95 | ND |

a Vopt is the optimal reaction rate achieved when the first protonable group is deprotonated (pKA) and the second group is protonated (pKB), according to Equation 2 (51).

b KISPox is the association constant for the deprotonated ISPox derived from the difference between the apparent pKA value, measured from the dependence of QH2 oxidation rate on pH, and pKox1 derived from the dependences of Em of ISP on pH, measured by protein film voltammetry (Table 1), given by KISPox = 10(pKISPox1− pKA) (16). Note that values for KISPox are dimensionless thermodynamic equilibrium constants, so they can be used relatively for comparison between mutant strains and with the thermodynamic values derived for QH2 binding. Since ISP is a tethered substrate, expression in terms of molar units presents difficulties, avoided here.

c I50, the normalized concentration of inhibitor added that blocked half of the functional bc1 complex (mol·stigmatellin/mol·bc1 complex), where values are with respect to total volume, was determined by titration. Concentrations with respect to the membrane phase would depend on the partition coefficient for stigmatellin. The relation of I50 to Ki (= 1/Ka) is complicated by the fraction of bound form, but this can be calculated from (I50 × (bc1 complex)) − 1/2(bc1 complex). This gives a Ki value of ∼15 nm for wild type, comparable with that in mitochondrial complexes. The values shown in parentheses are the reciprocals (in units 1/μm), adjusted for differences in [bc1 complex] so as to give an approximate value for Ka, to allow comparison of values with relative association constants for binding of ISPox and QH2. Values for [bc1 complex] for different strains were (in μm) as follows: WT, 0.173; S154T, 0.065; S154C, 0.21; S154A, 0.134.

Redox titrations of kinetic parameters for each mutant were carried out at a pH close to that of its maximal reaction rate (e.g. pH 7 for S154C; pH 7.51 for wild type, S154T, and Y156F; pH 8.25 for S154A and Y156W). Under these conditions, the concentration of ISPox is no longer limiting, and only the concentration of QH2, controlled by the ambient potential (Eh), determined enzyme activity. When the initial rate was determined as a function of Eh, the shift in midpoint of the titration then provided a measure of the change in affinity of the Qo-site for QH2. The displacements (ΔEmES-free) of enzyme activity are shown in Table 3, and the relative association constants for QH2 at the Qo-site (KQH2) were calculated from these values as suggested previously (16). The mutant strains showed ΔEmES-free values from wild type ≤20 mV, indicating ≤4-fold changes in the KQH2 values (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Affinity of the QH2 at the Qo-site

| Strains | Kinetic titration at optimal pHa |

Michaelis-Menten valuesb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmES | ΔEmES | KQH2 | KQH2 | Km (1/Km) | Vmax | |

| mV | mV | % | ||||

| Wild-type/BH6 | 99.1 ± 1.2 | 39.3 | 21.3 | 100 | 4.01 (0.25) | 1120 |

| S154T | 82.7 ± 2.5 | 22.9 | 5.93 | 27.9 | 7.76 (0.129) | 826 |

| S154C | 112.6 ± 2.3 | 22.6 | 5.81 | 27.3 | 6.52 (0.153) | 796 |

| S154A | 53.2 ± 1.9 | 37.1 | 18.0 | 84.7 | 5.23 (0.191) | 133 |

| Y156F | 84.6 ± 2.1 | 24.8 | 6.88 | 32.3 | 7.22 (0.139) | 695 |

| Y156W | 64.3 ± 2.2 | 48.2 | 42.8 | 201 | 2.41 (0.415) | 221 |

a KQH2 is the (relative) association constant for QH2 at the Qo-site derived from the difference between the potential at which the kinetics of cyt bH reduction in the presence of antimycin A was half-maximal (EmES) on titration of the Q-pool, and the conventional Em of the Q/QH2 pool, free in the membrane phase (Em,pH7free = 90 mV) (38) using the following equation (reviewed in Ref. 16): KQH2 = exp{(zF)/(RT) ΔEmES-free}. The EmE values in the table were measured at a pH close to the optimum for activity for each variant (e.g. pH 7 for S154C; pH 7.51 for wild-type, S154T, and Y156F; pH 8.25 for S154A and Y156W). Since the values here are derived from thermodynamic measurements, they are in principle dimensionless. Kinetic equilibrium constants have concentration units, but the relation to these thermodynamic values is complex (16). If KQH2 is taken to reflect the differential binding for Q and QH2, then an unknown value for KQ enters the calculation. If the binding of Q is ignored, values from dimensionless ratios must be normalized to [ES]; then, from the membrane concentration of [Etot] ≈0.5 mm, the values for KQH2 here would have to be multiplied by ∼2 × 103 for expression in units m−1, where concentrations are with respect to the membrane phase. Because the same ratios of binding constants enter into calculation of competitive effects, the values for Km cannot be used to “correct” these values (see Ref. 16 for discussion).

b Values for Km are in mm units. The reactive quinone pool was assumed to be 30 mol/mol of RC (12, 34, 38), and the ratio of QH2 per bc1 complex was calculated from the Nernst equation, using the observed ratio of RC:bc1, the Em of Q/QH2 couple at the optimal pH chosen, and the poised potential, Eh. It was assumed that the amplitude of heme bH reduction with the pool oxidized (at Eh,7 values >180 mV) reflected the QH2 generated in the RC, and this amount was added to that calculated from the redox poise. The reaction rate at each poised potential was plotted against the corresponding QH2 concentration to generate Michaelis-Menten plots, and values were re-plotted to generate a Hanes-Woolf (52) plot (([S])/(v)) = (([S])/(Vmax)) + ((Km)/(Vmax)) from which Km and Vmax values were derived; values for 1/Km are shown in parentheses for comparison with association constants. The Km values are given in mm units, but these depend on the membrane concentration of RC, bc1 complex, and QH2. The terms can be calculated as above from [RC]membrane of ∼2 mm, estimated from measured RC:lipid ratios, and the following values for the bc1 complex:RC ratios in the chromatophores used in these experiments as follows: wild-type (BH6), 0.56; S154T, 0.6; S154C, 0.63; S154A, 0.87; Y156F, 0.65; and Y156W, 0.54. Because the kinetic measurements were all made in situ, the values will also reflect a weak competition with Q, which cannot be simply estimated from the measured or calculated values (16). It is unlikely that this competition distorts the data significantly, but the Km values must regarded as relative rather than absolute, as discussed in the text.

Although the displacements provide a measure of relative binding, the values calculated include unknown terms that reflect the differential binding of QH2 to Q in the active site. The values shown assume that the binding of Q does not contribute to a significant energy term, so that ΔGQ ≈ 0, and KQ ≈1. The relation of these values to membrane concentrations are discussed in detail in Ref. 16. The titration curves could also be used to construct Michaelis-Menten (34) curves, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Hanes-Woolf (52) plots of the data were used to estimate apparent Km values (Table 3). Possible complications arising from competition with the quinone form (39) are discussed below.

Although the Km and KQH2 values cannot be directly compared, the Km values of S154T, S154C, and Y156F represent slightly decreased affinities of QH2 from wild type strain, consistent with the results from KQH2 estimations. The Y156W strain showed a slightly increased affinity of the substrate, QH2, which was also predicted in the KQH2 estimation. The Km value of the S154A strain was close to that of wild type, in contrast with the previous report from Schroter et al. (25) but in line with the relatively small effects on KQH2 for this strain. The estimated Vmax values of all the strains were similar to the Vopt values measured in pH titration, as discussed below. Table 2 includes the I50 values for stigmatellin inhibition expressed as (mol of stigmatellin)/(mol of bc1 complex) required for 50% inhibition and approximate values for Ka (= 1/Ki).

Pulsed X-band EPR to Determine Changes in the Proton Environment of the Cluster

Recently, we characterized the proton environment of the reduced [2Fe-2S] cluster in the water-soluble head domain of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein fragment by orientation-selected two-dimensional ESEEM (HYSCORE) at X-band (41). The two-dimensional spectra show multiple cross-peaks from protons, with considerable overlap. Samples in 1H2O and 2H2O were used to separate the signals from nonexchangeable and exchangeable protons, the latter likely involved in hydrogen bonds in the neighborhood of the cluster. By correlating the cross-peaks from two-dimensional spectra recorded at different parts of the EPR spectrum, lines from nine distinct proton signals were identified. Assignment of the proton signals was based on a point-dipole model for interaction with electrons of Fe(III) and Fe(II) ions, using the high resolution structure of iron-sulfur protein fragment from R. sphaeroides (8). Even two-dimensional spectra did not completely resolve all contributions from nearby protons. We concluded that the seven resolved signals from nonexchangeable protons with effective anisotropic coupling Tmax (largest component of anisotropic hyperfine tensor) in the interval from 16.8, 10.4, 9.6, 8.4, 7.6, 6.2, and 3.2 MHz, might represent at least 13 protons. The contributions from exchangeable protons were resolved by difference spectra (1H2O minus 2H2O) and assigned to two sets with distinct Tmax ∼8–10 and <5 MHz. In the point-dipole model, three protons would be expected to have a hyperfine tensor with Tmax ∼6–6.5 MHz as follows: those from the hydroxyl –OH of Ser-154 (HG1637), from the peptide –NH of Leu-132 (H1354), and from the peptide –NH of His-152 (H1613). All other exchangeable protons located around the cluster would have smaller Tmax values, varying between 1.65 and 4.7 MHz. Considering these results, one can suggest that the larger couplings resolved in our spectra are produced by exchangeable protons from Ser-154, Leu-132, and/or His-152, and the smaller couplings then represent the unresolved contribution of the remaining more weakly coupled exchangeable protons. However, the largest measured coupling exceeded any calculated value. This discrepancy could result from limitations of the point dipole approximation in dealing with the distribution of spin density over the sulfur atoms of the cluster and the cysteine ligands, or from differences between the structure in solution and the crystallographic structure.

Here, we investigate how mutations Y156F and S154A influence the 14N HYSCORE spectra from coordinated Nδ of histidine ligands, and the proton HYSCORE spectra, of the reduced cluster. The chemical effect of both these mutations is to replace a hydroxyl (−OH) group (for which the exchangeable proton acts as H-bond donor) by a nonexchangeable H-atom, a replacement known to change the EPR line shape (15).

The effects of the mutations on the spectra from the histidine ligands were minor, and they appear as differences in relative intensity of the cross-peaks but not in the cross-peak frequencies (data not shown). This indicates that the mutations do not influence the geometry of histidine coordination. However, weakly coupled interactions (for example through H-bonding) are not well resolved by 14N ESEEM at X-band, and more extensive studies using 15N and S-band might reveal changes in the nitrogen environment of the cluster (35).

The 1H HYSCORE difference spectra (WT minus mutant) of both S154A and Y156F show two pairs of cross-peaks a and b with positive intensity in each case (Figs. 5 and 6), which resulted from the redistribution and/or disappearance of cross-peaks. These changes could be due to changes in hyperfine coupling produced by the absence of a proton or to changes in electron spin density distribution or ligand geometry. Contour line shape analysis of the two pairs of cross-peaks in the S154A-WT difference spectrum shows that cross-peak a corresponds to a proton anisotropic hyperfine coupling of Tmax ∼11 MHz and cross-peak b to a coupling of ∼8 MHz. These couplings are close to the values for strongly coupled exchangeable protons, which include that suggested for the Ser-154 –OH (HG1637). One of the pairs of cross-peaks seen as disappearing in the difference spectrum could therefore reasonably be assigned to this hydroxyl proton, which is “lost” in the mutant. On the other hand, they are also consistent with the range of couplings for nonexchangeable protons. The mutation could influence the nonexchangeable proton on Cβ (HB2 1635) and/or the exchangeable proton of the peptide N of Ser-154 (H1633), with Tmax = 6.46 and 3.6 MHz, respectively, in the point-dipole approximation. One of these protons could be responsible for the second pair of cross-peaks.

FIGURE 5.

HYSCORE spectra of Y156F (A) and WT (B) are shown. 1H spectra are displayed in a three-dimensional stacked plot representation and as corresponding contour plots. Parameters of the measurements are listed in the figure. The HYSCORE difference spectrum (C) shows the redistribution and/or disappearance of cross-peaks in a contour plot. Peaks labeled a and b are discussed in the text.

FIGURE 6.

HYSCORE spectra of S154A (A) and WT (B) are shown. 1H spectra are displayed in a three-dimensional stacked plot representation and as corresponding contour plots. Parameters of the measurements are listed in the figure. The HYSCORE difference spectrum (C) shows the redistribution and/or disappearance of cross-peaks in a contour plot. Peaks labeled a and b are discussed in the text.

The Y156F mutant also perturbs the cross-peaks in a manner similar to the S154A. In this case, because the hydrogen-bonded proton was ∼4.5 Å from Fe(III), it would have a small HF coupling (T ∼1.5 MHz) and would not be expected to give a well separated peak in the difference spectrum. The effects observed could possibly result from the influence of the lost H-bond (between the hydroxyl proton of the Tyr-156 and the Sγ of Cys-129) on the conformation of the cysteine ligand, which would lead to changes of the hyperfine couplings with the β-protons of cysteine, a possibility supported by small changes in Cβ and Sγ distances from the iron in the structures (8). More detailed analysis and firmer assignment of the peaks in the differences spectra would require extensive orientation-selected HYSCORE of samples prepared in H2O and 2H2O. Labeling of the protein with 15N would also enhance the proton cross-peaks significantly because they are influenced by the cross-suppression from 14Nδ, which show deep ESEEM at natural abundance (53).

DISCUSSION

Relationship between Biophysical Properties and Structural Features of the Ser-154 and Tyr-156 Mutant Strains

Structures show that the ISP of the bc1 complex is composed of the membrane-spanning tail domain (N terminus), the cluster-containing head domain (C terminus), and the hinge region that connects them. The redox function of the Rieske-type ISP is determined by the [2Fe-2S] cluster, the characteristics of which reflect interaction with the protein and solvent environment, including the ligands, the hydrogen-bonding network (Fig. 1), and the disulfide bond between two exterior facing cysteines (Cys-134 and Cys-151). Structures of the bc1 complexes from many different species from chicken to photosynthetic bacteria have now been resolved (3–8) so we could study the homology of the structures of ISP from various species. The strong homology between sequences of the [2Fe-2S] binding domains suggests a minimal structural deviation among species (8, 29, 54). In this study, we have taken advantage of the facility for molecular engineering and for functional characterization in R. sphaeroides to explore detailed aspects of the structure-function interface. X-ray crystallographic structures (8) were used to facilitate interpretation of the biophysical measurements. The overall structures of the mutant ISPs were similar except at the mutated residues. The root mean square deviation between mutant and wild type backbone coordinates was less than 0.15 Å (0.141 Å for S154T; 0.128 Å for S154C; 0.134 Å for S154A; 0.105 Å for Y156F; and 0.124 Å for Y156W root mean square deviation of main chain atoms), which confirms that the electrochemical alteration in the mutant ISP comes from the single amino acid substitution and not from the changes in the polypeptide scaffold of the mutant ISP. The high resolution (between 1.1 and 1.5 Å for all structures) achieved in the crystallographic work makes possible an assignment of atomic positions from which precise values for bond length can be measured. The solution structures, as determined by two-dimensional ESEEM spectroscopy, are consistent with the crystallographic structures.

The lengths determined for H-bonds between the S-1 atom of the cluster and the residue at position 154 can account for the slightly higher Em (+16 mV in Eacid) of S154C. The distance between the sulfur atom of the substituted cysteine residue and the sulfur atom in the cluster is 3.07 Å, whereas the corresponding bond length in the WT is 3.17 Å (8). Although this distance excludes the possibility of a disulfide bridge between the two sulfur atoms, the shorter distance between the atoms would result in a stronger hydrogen bond reflected in the lower pKox1 value and the higher Em value under physiological conditions. However, these characteristics must be based on a more fundamental property that changes on substitution of a sulfur atom in the position of the oxygen. The electron affinity is defined as the energy difference between the neutral state and the corresponding singly charged negative ion (55), such that the attraction to extra electrons of sulfur (ΔE(S + e− → S−) = −2.077 eV) is more favorable than that of oxygen (ΔE(O + e− → O−) = −1.461 eV), consistent with values for the sulfhydryl and hydroxyl residues of −2.314 and −1.828 eV, respectively. The higher Em and the lower pKox1 values could then be ascribed to increased electron withdrawal by the more electron-friendly sulfur atom.

S154T showed the smallest changes in the Eacid (−20 mV) and pKox1 (+0.1 pH unit) values among the mutant strains. As indicated previously (8), the addition of a methyl group on C-β is associated with a structural change on interaction with a hydrophobic cleft near the Ile-162 and Tyr-156 residues. The packing of these residues is too tight to allow introduction of any substantial volume, so the integrity of the [2Fe-2S] cluster would be compromised on replacement of the serine by a more bulky side chain. For example, no reduction of cyt bH was observed over the 10-s time range on excitation of the S154Y mutant strain after multiple flash excitation (data not shown), suggesting a failure of integration of the cluster. In the S154T structure, the added methyl side chain of threonine was accommodated by displacing the side chains of both Ile-162 (through an ∼150° rotation about the Cβ–Cγ bond, Fig. 7A), and Tyr-156 (by a small displacement), causing distortion of the H-bond at the Oη of Tyr-156. It seems likely that the modified biophysical parameters could reflect these packing parameters rather than a change in the H-bond between the threonine and S-1, which had a similar distance (3.16 Å) to that in the wild type (3.17 Å).

FIGURE 7.

Structural changes on mutation. Superimposed images comparing the structures of some mutant ISPs (S154T, red; Y156W, magenta) with that of wild type (CPK color). A, added methyl group in Ser-154 position stretches into the hydrophobic cleft between Ile-162 and Tyr-156, replacing the position of the Cδ of Ile-162 and making the aromatic ring plane of Tyr-156 tilt by 10°. B, volume enclosed by the [2Fe-2S] cluster capturing loops (Cys-129 to Cys-134 and Cys-151 to Tyr-156) expanded on the substitution of tyrosine by tryptophan at the 156 position.

For the other three mutants (S154A, Y156F, and Y156W), each mutation results in loss of an electron-withdrawing oxygen atom in the hydrogen bonding network, and this leads to significant change in the Em and pKa values. The structural effects from these mutations reside in the substituted residues, so we could use them to compare the relative contributions from the hydrogen bonding from these positions. The mutation in S154A showed the most significant effect on the physicochemical parameters, and on the kinetic behavior of the complex. The Eacid of the S154A was displaced by −130 mV and the pKox1 shifted by 0.45 pH unit in the basic direction; the apparent pKa value, measured in the intact complex through kinetic parameters, showed an even more dramatic shift (0.84 pH unit). The displacements in the parameters of the two Tyr-156 mutant strains were less marked. Comparing Y156F with S154A, the values in the former showed smaller changes than the latter (−54 mV in Eacid and 0.17 pH unit in pKox1), although both mutants are deficient in single hydroxyl groups, which suggests that the electron-withdrawing ability on the cluster depends upon placement.

In previous studies of the Y156W ISP (8, 15), we reported that the indole ring of the tryptophan caused a large perturbation in the structure (Fig. 7B). The packing mismatch in the space occupied by the side chain results in displacement of the nearby polypeptide loops (Gly-127 through Ile-137 and Gly-146 through Gly-153) and movement of the [2Fe-2S] cluster by 0.4 Å (8). These modifications in the structure likely cause the substantial variation in the EPR spectra (15) and the larger changes in the thermodynamic parameters (−100 mV in Eacid and 0.28 pH unit change in pKox1).

An aromatic amino acid in the position of Tyr-156 seems to be essential to the integrity of the [2Fe-2S] cluster. Although we constructed the Y156H and Y156L mutant strains, we could not detect any cyt c re-reduction in the flash-induced kinetic measurements for either mutant and could observe no ISP subunit band on SDS-polyacrylamide gels after protein purification (data not shown). Although the size and shape of the histidine are similar to those of tyrosine, and leucine has a similar hydrophobic character, the only substituents expressed had a conjugated ring, which on this basis seems necessary for functional assembly of the ISP head domain.

Changes in Kinetic Behavior in Mutant Strains

The parameters determining the rate-limiting step are the driving force for the first electron transfer and the pKox1 of ISPox that establishes not only the pH dependence of electron transfer but also the fraction of the activation barrier contributed by the Brønsted term (16, 18). Before considering these major effects, we discuss additional effects that might modify rate constants controlling turnover.

Modification of the Substrate Binding Constants Mediated by Mutagenesis

Because the factors that affect the strength of hydrogen bonds are complex and not fully understood, interpretation of the effects of the mutagenic interference on the strength of the hydrogen bond involved in formation of the ES complex must be conjectural. Generally, the hydrogen bonding strength is controlled by the temperature, bonding distance and angle, polarity of atom, and environment. In this study, we could consider the pKa changes in ISPox, and environmental variation caused by the mutagenesis, as variables.

Shan and Herschlag (56) investigated the intramolecular hydrogen bond of substituted salicylic acids and showed a decrease of hydrogen bond strength with an increase in ΔpKa. The changes in aqueous media were relatively small (slope of log10KHB versus ΔpKA was 0.05 or 0.285 kJ/mol) compared with the hydrogen bond enthalpy of water molecules, 23.3 kJ/mol (57), but a more obvious effect was apparent in a nonaqueous environment (with DMSO as solvent) (slope of 0.73 or 4.16 kJ/mol of free energy change per unit change of ΔpKa). These values provide a range that might be appropriate to analysis of our data.

Structural aspects of the binding of ISP at the interface with cyt b in the presence of inhibitors with which it forms a complex have been analyzed in chicken (58), bovine (59), yeast (60), and R. sphaeroides complexes (7). Binding is mediated by several residues and involves hydrophobic, aromatic, and hydrogen bonding interactions. In R. sphaeroides, the latter include three H-bonds in the cluster neighborhood (ISP His-152 Nϵ to stigmatellin –C=O; cyt b Thr-288 Oγ to ISP Ser-135 N; and cyt b Tyr-302 OH to ISP Cys-151 O). When stigmatellin occupies the distal lobe of the Qo-site, the Nϵ of His-152 from the reduced ISP forms a tight hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen of the inhibitor that stabilizes the structure, and likely mimics the bond to Q in the EP complex, both interactions giving distinctive EPR (15, 61) and ESEEM (62) signals for the reduced cluster. Because H-bonds from Ser-154 and Tyr-156 contribute an important fraction of the electron-withdrawing force acting on the [2Fe-2S] cluster, this would be transferred to the histidine ligands (so contributing to the high pK and resulting in the pK change in mutants), so that mutagenesis would also be expected to modify the strength of the hydrogen bond between the histidine side chain and the occupant of the Qo-site (either Q, QH2, or stigmatellin). To explore this, we measured the affinities of substrates for formation of the ES complex from the thermodynamic displacements of binding of QH2 and ISPox in kinetic experiments and that for formation of the EI complex with stigmatellin, based on sensitivity of the Ser-154 mutants to this inhibitor. The latter showed a 10–25-fold decrease in affinity for all the Ser-154 mutant strains (see Table 2; also reported briefly in Ref. 8).

From Shan and Herschlag (56), and the pKox1 shifts in the mutant strains, a tighter binding of QH2 would be expected, because increases in pK value for all the variants except S154C would more closely match the pKa of QH2 (>11.3). However, contrary to these expectations, the apparent binding constants for ISPox (based on the ΔpK displacements of Table 2) indicate small decreases in affinity for all the mutant strains. Other factors would therefore have to be invoked to account for the changes observed. The calculated binding energy changes in the mutant strains were modest (∼0.5 kJ/mol decrease from the value from the wild type) for all except S154A, indicating at least that the ISP binding at the Qo-site is relatively independent of the pK change on ISP.

Because the protein environment of the Qo-site was not modified by the mutagenesis in ISP, any changes in apparent binding constant of QH2 (KQH2) (Table 3) would have to be attributed to the effects from the ΔpKa shifts in ISP. However, interpretation of KQH2 is complicated (16, 36). The value here is determined from the midpoint of the Q/QH2 couple involved in the ES complex, EmES, measured kinetically. The change, Δ EmES−free, from the Em of the Q/QH2 free in the pool reflects the formation of the complex. However, this process is not simple. In the state prior to flash activation, ISP would be reduced (ISPH) and form a ligand with the Q occupying the Qo-site in most centers (36). On oxidation of ISPH following a flash, and formation of the ES complex, ISP becomes oxidized and binds to QH2 at the Qo-site in the imidazolate form, ISPox. The change in state leading to the ES complex therefore represents, minimally, the differential binding of Q and QH2 with both ISPH and ISPox, and a complete treatment has to take into account affinities in both initial and final states. The E-ISPH-Q complex (an EP complex state (36, 61)) can be assayed from titrations of the gx EPR line of ISP. Ding et al. (63, 64) concluded that binding of Q and QH2 occurred with similar affinity in formation of this state. The H-bond formed between ISPH and Q at the Qo-pocket is similar to that involved in the binding of ISPH to stigmatellin, for which the affinity was modified by the mutation (Table 2), so we might anticipate that changes in affinity of ISPH for Q could occur. This could contribute indirect competitive effects that might modify the value measured for KQH2. On the other hand, although artificial quinones can compete at the site (39, 40, 65, 66), it is unlikely that the native Q competes strongly in formation of the ES complex. It cannot form a strong H-bond with ISPox, because the donor function of the –NϵH group has been removed on oxidation. A weak competition cannot be excluded, if only because diffusional interference in the tunnel leading to the Qo-site from the membrane would be unavoidable, but the exchange of Q for QH2 occurs much faster than the rate-determining step (36), and it does not contribute to the measured rate.

The dependence of rate on Eh in the range over which the Q pool becomes reduced can also be used to calculate the dependence on [QH2] (14, 16, 34); we used this to estimate apparent Km values for QH2 through a Michaelis-Menten approach and compared these with other binding constants (Table 3). As noted under “Experimental Procedures” and above, the values for Km reported here are empirical, because minor effects from a weak competition with the oxidized quinone might contribute thermodynamic terms to modify the value (16). The approximately equal affinity for Q and QH2 when ISP is reduced (63, 64) is clearly changed so as to favor QH2 when ISP is oxidized, but in view of the complications discussed above, this work does not provide a basis for independent estimation of affinities for either of these forms under the metastable conditions of ES complex formation. It seems unlikely, given the Eh range involved, that competition would have a marked differential effect in mutant strains and wild type, but in any case, changes in the apparent Km values derived here would be the values of interest. The mutants fall into two distinct groups as follows: the strains that show relatively fast reaction rates (S154T, S154C, and Y156F) have slightly lowered affinity of QH2, and the Y156W had increased affinity of QH2, as predicted from the ΔpKa, and S154A had a similar affinity to wild type, despite the increased pKa. The latter mutant group also showed relatively higher values for KQH2 when compared with those of the former group. However, the S154A variant showed somewhat anomalous features for association constants, with a lowered affinity of ISP to the Qo-interface, but an affinity of QH2 similar to wild type in formation of the ES complex. As a consequence, the differential QH2 binding compared with Q at the Qo-site (KQH2) was only slightly smaller than that of the wild type.

In summary, the changes in affinity for both substrates on formation of the ES complex associated with the changes in pKa were small. The dominant effects of change in pKa come from the effect on [ISPox], and hence formation of the ES complex at a particular pH, and from the contribution to the activation barrier discussed below.

Analysis of the bc1 Complex Reaction Rates Based on Marcus-Brønsted Model

A major interest of the results from our new mutants lies in their use in testing the PT/ET mechanism proposed previously (16–18). Analysis of the Qo-site reaction has to recognize several levels of complexity, illustrated by the energy landscape for the reaction, summarized in Fig. 8. The bifurcated nature of the reaction introduces the need to consider the interplay between the two electron transfer reactions involved (1, 12). The overall reaction of the bc1 complex is slightly exergonic (ΔG0′ = −2.9 kJ/mol at pH 7.0, where Em(ISP) = 310 mV, Em(bL) = −90 mV, and Em(Q/QH2) = 90 mV). The energy profile for the partial processes had showed that the main activation barrier lies in the first electron transfer process in which the QH2 is oxidized to semiquinone by ISPox (13, 14). The next level of complexity was introduced when the mobility of the ISP required recognition that the mobile domain acted as a tethered substrate, with implications for the formation of the ES complex (4, 58, 61). The measured activation barrier was independent of pH and of the redox poise of the quinone pool (i.e. independent of the substrate concentrations) (14), which excluded early proposals by Link (67) and Brandt and co-workers (51, 68), in which the deprotonation of the QH2 preceded formation of the ES complex, suggested to form via QH− as a necessary intermediate (69). The electron transfer reaction from the ES complex is endergonic, but by how much has been uncertain, because the stability of the intermediate SQ state was unknown. Constraints on the value have been discussed extensively elsewhere (14, 36, 70, 71). A minimal value for the occupancy ∼10−10 can be estimated from the activation barrier (71) but kinetic considerations demand a somewhat higher value, >10−8 (14). A maximal value is provided by analysis of the simultaneity of electron transfer to the two acceptor chains in the bifurcated reaction. Because the first electron goes to the high potential chain, generation of an SQ intermediate would be at the limiting rate, and the arrival of an electron at heme bH would be delayed by the time needed to populate the SQ state. From the kinetics seen in chromatophores, such considerations limit SQ occupancy to <0.025 (36, 73, 74), and from rapid mixing experiments with bovine bc1 complex an even lower value might be suggested (75). Recent measurements of SQ formed at the Qo-site under conditions in which it would be expected to accumulate (76, 77) have shown an occupancy ∼0.005, within the range previously considered (14), and suggest a value for Em(SQ/QH2) ∼460 mV. These measured constraints rule out reaction mechanisms favoring a stable ISPH.SQ complex at high occupancy as a participant in the normal forward reaction (67, 78). Moreover, the measured occupancy is much higher than the value we had previously favored, where we emphasized the need to minimize [SQ] so as to limit bypass reactions involving the SQ (14, 16). The change necessitates energy levels in Figs. 8 and 9 and supplemental Fig. S2 adjusted from those previously considered (16). In the present context, these determine the level of the SQ intermediate state and therefore the driving forces discussed, as shown in the energy landscape of Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Plausible energy profile of QH2 oxidation at the Qo-site. The different intermediate states of the Qo-site reaction are shown against a free energy scale normalized to the initial state. Dashed vertical arrows show ranges for energy parameters that would allow adequate rates of overall electron transfer with different assumptions (14, 16, 71). For the energy level for the intermediate product state after the first electron transfer, a more stable SQ is shown than in previous work to take into account constraints from Refs. 76, 77 on maximal occupancy of SQ in the Qo-site (71).

FIGURE 9.

Dependence of the reaction rates of mutant strains on the driving forces. Measured rates are compared with the theoretical curves generated using software package, Marcus_Bronsted.exe. The data points shown by square symbols are from measurements at pH 7.0 and fall close to the black curve, calculated using parameters for wild type (see supplemental Fig. S2). The data points shown by circles were from kinetic measurements at optimal pH, where the imidazolate form of ISPox was saturating. The values for log10k are therefore displaced from those at pH 7, and for most mutant strains are higher. At the optimal pH, the Em value was also displaced from the value at neutral pH (Fig. 3), so that the driving force for the overall reaction was changed, and the positions are therefore displaced from those of the square symbols with respect to the ΔG scale, to more endergonic values for most strains. The colored curves were calculated using the same values for constant parameters (values for λ, distances, redox properties, and pK values of the quinone system) as used for the black curve, but values for variables appropriate to each optimal condition and appropriate for each strain, using values for k (given by Vopt), and pKA were from the tables, and Em, pHopt was from Fig. 3. The black symbol represents wild type; the red, S154T; the green, S154C; the blue, S154A; the cyan, Y156F; the magenta, Y156W. Filled square symbols, reaction rates at pH 7; open circles, reaction rates at optimal pH.

The first electron transfer occurs from an ES complex, modeled with a hydrogen bond between the –OH group of the bound QH2 and the imidazolate ring of the deprotonated ISPox. The Marcus (79) dependence on driving force had established this as the rate-limiting step (17). Structures of the stigmatellin complex show an anhydrous interface between ISP and cyt b; assuming a similar interface, this would discourage H+ exchange between intermediate states and the bulk phase and ensure a coupled process. This bond therefore provides a pathway for transfer of both the electron and the proton. Consideration of plausible thermodynamic squares strongly suggested either a PT/ET model (14) or a concerted process (33, 72, 80). We strongly favored the PT/ET model because it accounted for the slow rate observed for the first electron transfer without ad hoc additions. The factors that come into play are the endergonic nature of the first electron transfer, the high activation barrier, the thermodynamic parameters explored here, and (from the stigmatellin-containing structures) the short distance, the pathway through the H-bond, and the anhydrous nature of the reaction interface. Consideration of these factors has to be convoluted with the parameters for the overall reaction, because the driving force for the second electron transfer also depends on the energy level of the intermediate product (Fig. 8). This complexity has been simulated in a computer program (Marcus_Bronsted.exe (16)) developed in-house, an updated version of which is included in the supplemental material. The PT/ET model handles each of these components naturally and, in our previous analysis, explained the reaction properties in the wild type with satisfactory economy. We will therefore use the same approach in the discussion below, in which we apply it to analysis of the mutant strains.

In modeling the reaction as a PT/ET process, it becomes necessary to partition the activation barrier into components associated with the PT equilibrium (given by a Brønsted term, ΔGproton = 2.303 RT(pKQH2 − pKISPox), which is unfavorable) and the activation energy for the electron transfer itself (16, 18). This latter step involves an operational driving force for the electron transfer step, given by the energy gap between the Brønsted barrier, and the SQ intermediate (Fig. 8). The second electron transfer, from semiquinone to heme bL, is likely much faster than the rate-limiting step, and it will be considered here only in so far as the two steps share common parameters. In the context of the first electron transfer, the parameter of importance to the present discussion is the Brønsted term, because the value for pKox1, which is modified in mutant strains, determines the contribution to the activation barrier, and this plays a direct role in determining rate constants. The same pKa enters into the stability of the ES complex, as discussed above, but these two terms play off against each other (their effects have opposite sign (16)) to an extent that depends on pH (see below). The value of Em for ISP is, of course, also an important parameter, because it determines the overall driving force for the first electron transfer. However, critical as this parameter is, any kinetic mechanism that recognizes the first electron transfer as the determining step would predict that changes in Em on mutation would be expressed in changes in overall rate constant, so this does not represent a feature unique to the mechanism proposed. The reaction in which ISPH is oxidized has a much higher rate constant, low activation barrier, and is relatively independent of pH (13, 14, 28), and it would not be rate determining under the experimental conditions used here.

Analysis of the experimental data in this work follows the approach outlined previously (15, 16) in which data were analyzed through simulation (see supplemental material for a brief outline). The program generates Marcus-type curves (log k versus −ΔG) for both electron transfer reactions while keeping track of interdependency of parameters for the first and second electron transfers. To test the contribution of the pKa shift in each mutant strain, Marcus-Brønsted curves for the first electron transfer reaction were generated from the program to fit the points from kinetic experiments from different mutant strains, values for kcat based on the reaction rates at neutral and at optimal pH (Vopt from Table 3), and thermodynamic parameters (data from Tables 1–3). The distance parameter (∼7 Å) was kept constant, and reorganization energy (λ ∼0.95 V) was chosen so as to optimize the fit but was the same for all curves. Theoretical curves are displayed in Fig. 9 and supplemental Fig. S2. The square symbols in Fig. 9, and the plots in supplemental Fig. S2 demonstrate the conventional dependence of rate on driving force expected if the first electron transfer is limiting. The colored circles and curves in Fig. 9, which use the experimental parameters measured at the optimal pH for each mutant strain, demonstrate the outcome expected from the PT/ET mechanism. The colored curves in Fig. 9 can be compared with the curve for wild type (black and see supplemental Fig. S2), which was based on parameters to fit the wild type at pH 7, and fits the data points measured at pH 7 (square symbols) quite well but not the points at optimal pH (filled circles). The improved fits of the colored curves to these points reflect the use of parameters for variables appropriate to each mutant measured under optimal conditions. The position of each point within the plot is determined by Vopt and Em,pH (driving force), and the position of the curve by pKA (Table 3, effectively the operational pK and dependent on pKox1), all set according to experimental values appropriate to each strain. The effect of change in pKA on the dependence of rate on substrate concentration (for [ISPox]) (16, 18), which at pH < pK plays off against the contribution to the activation barrier (the ΔpK term in the Marcus-Brønsted treatment), is compensated by choice of Vopt at optimal pH so that the effect is minimized, leaving the change of the rate due to the changed activation barrier as the dominant effect. The changes in rate are then accounted for both in magnitude and sign (see difference between Vopt compared with VpH7 for S154A and S154C; Fig. 9) by the effect of the change in pKA (pKox1) on the level of the Brønsted barrier (Fig. 8), and hence both the activation energy and the operational driving force for the electron transfer step, defined as above. The analysis demonstrates that the PT/ET model previously proposed explains the behavior of the mutant strains without any need for additional assumptions, simply by taking account of the thermodynamic characteristics of their ISPs.

Conclusions

The function of the Qo-site of the bc1 complex is largely determined by the rate-limiting first electron transfer reaction. The properties of this reaction are intimately linked to those of the ISP, which participates as substrate (active in its oxidized imidazolate form) and which (through Em) determines driving force and (through pKox1 values) modulates both the concentration of the active form and the activation barrier. In this study, we have explored these parameters through characterization of mutant strains, with respect both to thermodynamic parameters and functional characteristics. We have also provided new information on the hydrogen bonding network in the cluster environment that determines values for the thermodynamic parameters. We have related the values determined to the functional characteristics through a Marcus-Brønsted analysis and have shown that the behavior can be well explained by the simple PT/ET hypothesis proposed previously. This analysis provides a firm mechanistic basis for the roles of Em and pKox1 of ISPox in determining the reaction rates of the bc1 complex. Contributions from both are revealed in the analysis. A shift in pKox1 to the alkaline (especially in S154A, Y156F, and Y156W) lowers the concentration of active form in the neutral range, but it increases the probability of favorable hydrogen bond configuration for electron transfer. These terms offset each other at pH < pKA, so that the remaining contribution to rate from change in driving force becomes the dominant term. When pH > pKA, the contribution of change in pKox1 to change in activation barrier is revealed. The case of S154C is especially interesting because, consistent with this hypothesis, it showed the slower reaction rate due to the increased activation barrier consequent on the pK shift to the acid, despite the marginally higher Em,7 (and driving force) compared with wild type.

In general, the PT/ET mechanism previously proposed (16–18) continues to provide a plausible model to account for the rate of reaction in terms of parameters for partial processes that are well justified by experiment. By recognizing the importance of proton-coupled electron transfer in determining the reaction rate, and the role of proton configuration in determining the reaction sequence, we can account for the slow rate observed for electron transfer through a short distance and the modulation of rate in mutant strains. By adapting the classical Marcus activation barrier through addition of a Brønsted term, we have achieved a quantitative understanding of an otherwise paradoxical set of observations, using conventional values for driving force and reorganization energy. Because the same treatment accounts for the effects of pK shifts in slowing the rate in mutants with different properties, S154A, S154C, Y156F, and Y156W, all in the context of experimental data used in the fitting, the results provide support for a claim that we now understand quite well as the first electron transfer at the Qo-site and hence the limiting process for steady state electron transfer through the bc1 complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. William Mantulin and the Laboratory for Fluorescence Dynamics (University of Illinois, Urbana) for help with CD spectroscopy and Dr. Judy Hirst and colleagues (Medical Research Council, Cambridge, UK) for advice on setting up our protein film voltammetry apparatus. We also acknowledge the assistance of Andrew Park in site-directed mutagenesis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM 35438 (to A. R. C.), GM 62954 (to S. A. D.), and S10-RR15878 from NCRR (for instrumentation).