Abstract

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) generates reactive halogenating species that can modify DNA. The aim of this study was to investigate the formation of 8-halogenated 2′-deoxyguanosines (8- halo-dGs) during inflammatory events. 8-Bromo-2′-dG (8-BrdG) and 8-chloro-2′-dG (8-CldG) were generated by treatment of MPO with hydrogen peroxide at physiological concentrations of Cl− and Br−. The formation of 8-halo-dGs with other oxidative stress biomarkers in lipopolysaccharide-treated rats was assessed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and immunohistochemistry using a novel monoclonal antibody (mAb8B3) to 8-BrdG-conjugated keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The antibody recognized both 8-BrdG and 8-CldG. In the liver of lipopolysaccharide-treated rats, immunostaining for 8-halo-dGs, halogenated tyrosines, and MPO were increased at 8 h, whereas those of 8-oxo-2′-dG (8-OxodG) and 3-nitrotyrosine were increased at 24 h. Urinary excretion of both 8-CldG and 8-BrdG was also observed earlier than those of 8-OxodG and modified tyrosines (3-nitrotyrosine, 3-chlorotyrosine, and 3- bromotyrosine). Moreover, the levels of the 8-halo-dGs in urine from human diabetic patients were 8-fold higher than in healthy subjects (n = 10, healthy and diabetic, p < 0.0001), whereas there was a moderate difference in 8-OxodG between the two groups (p < 0.001). Interestingly, positive mAb8B3 antibody staining was observed in liver tissue from hepatocellular carcinoma patients but not in liver tissue from human cirrhosis patients. These data suggest that 8-halo-dGs may be potential biomarkers of early inflammation.

Keywords: Antibodies/Monoclonal, Diseases/Cancer, DNA/Damage, Metabolism/Nucleotide, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Halogenation, Inflammation, Myeloperoxidase

Introduction

Oxidative damage is implicated in the pathogenesis of many diseases including atherosclerosis and cancer (1–4). Involvement of myeloperoxidase (MPO),2 a heme protein secreted by activated leukocytes such as neutrophils and monocytic cells, is a potential cause of oxidative damage during inflammation. At sites of inflammation, activated leukocytes play a major role in host defense against microorganisms using oxidants such as HOCl and HOBr. However, excessive oxidant release can also induce damage; DNA bases (5–8) and proteins and lipids (9–12), for instance, are putative targets of oxidants.

At plasma halide concentrations (100 mm Cl−, 20–100 μm Br−) (13), MPO converts HOCl to HOBr using Br− as a halide exchange (14). HOBr is also generated by eosinophil peroxidase using H2O2 and Br−, such as by the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system. Because MPO catalyzes halogenation, oxidation, and nitration (15–17), MPO and its product may be important general markers for evaluating oxidative damage to the body during inflammation. Halogenation is a key reaction for the formation of an MPO activity marker because the presence of halogen in the marker molecule directly indicates a contribution of the halogenating species at the site of oxidative damage. Moreover, no other halogenating pathways have been reported except for MPO and eosinophil peroxidase-derived damage. Therefore, halogenated products have the potential to be specific markers of inflammation.

With respect to halogenation of nucleic acid, bromination of 2′-deoxycytidine (dC) and uracil has been reported in detail (18–20). At physiological conditions, 5-bromo-dC was generated by human eosinophiles, whereas 5-bromouracil was detected by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry in the inflammatory tissue of human subjects suffering from a variety of bacterial infections (19, 20). In human atherosclerotic tissue, 5-chlorouracil and 5-bromouracil were generated by MPO (3). An antibody against N4,5-dichloro-deoxycytidine (N4,5-diCldC) was developed and used for immunohistochemistry in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated mice. In that inflammation model, immunopositive N4,5-diCldC staining was observed in the liver (21). Chlorination of deoxyguanosine (dG) by exposure to HOCl was also reported (22). By contrast, there is little information on modification of dG by brominating species.

In the present study, we examined the patterns of brominated dG generation in vitro. We prepared the monoclonal antibody (mAb8B3) specific to 8-halogenated dGs (8-chloro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-CldG) and 8-bromo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-BrdG)). Using that antibody and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), our results demonstrated facile formation of 8-halo-dGs in the liver and urine of rats administered LPS. Furthermore, with respect to the order of modification of dG, halogenation occurred prior to oxidation and nitration, which may be useful for evaluation of the progress of inflammatory diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

2′-Deoxynucleosides, DNase I, nuclease P1, 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OxodG), 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, bovine serum albumin (BSA), LPS from Escherichia coli, and 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Methionine, taurine, 4-aminoantipyrine, NaOCl, metaphosphoric acid, and alkaline phosphatase were obtained from Wako Pure Chemicals Industries. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG was obtained from Cappel. Anti-MPO polyclonal antibody was obtained from DAKO. HOBr was prepared from an equimolar solution of NaOCl and KBr as described (20). 15N5-dG was obtained from Spectra. Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) was obtained from Pierce.

Reaction Conditions for dG Modification by Myeloperoxidase

As typical conditions, 1 mm dG, 20 nm MPO, 100 μm H2O2, 100 mm NaCl, and 100 μm NaBr were reacted for 60 min at 37 °C in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reaction was terminated by adding catalase to scavenge H2O2. Each component was varied as described in the text. The formation of brominated dG was quantified by LC-MS/MS, as described below.

Preparation of 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG and Their Internal Standards

Modified dGs and their stable isotopic internal standards were prepared as follows: (a) For 8-CldG, dG (2 mm) was supplemented with nicotine (20 μm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). The reaction was initiated by adding NaOCl (1 mm) to the reaction mixture at 37 °C for 1 h and terminated by adding methionine (10 mm). (b) For 8-BrdG, dG (2 mm) was supplemented with taurine (1 mm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by adding HOBr (1 mm) to the reaction mixture at 37 °C for 1 h and terminated by adding methionine (10 mm). (c) For 8-OxodG, dG (2 mm) was supplemented with ascorbate (1 mm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by adding H2O2 (1 mm) to the reaction mixture at 37 °C for 4 h. 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8- OxodG were isolated by reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Develosil C30, 20 × 250 mm) using 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid at a flow rate of 6.0 ml/min with monitoring at 280 nm. The internal standards were prepared using 15N5-dG as a parent molecule by the same methods as described above. The obtained compounds were characterized by LC-MS scanning the molecular ion peaks (8-CldG, m/z 302.1; 15N5-8-CldG, m/z 307.0; 8-BrdG, m/z 345.9; 15N5-8-BrdG, m/z 350.9; 8-OxodG, m/z 284.0; 15N5-8-OxodG, m/z 288.9).

Conditions of Detection of 8-Modified dGs by LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS analyses were performed on an API 2000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) through a TurboIonSpray source. Chromatography was carried out on a Develosil ODS-HG-3 column (2.0 × 50 mm) using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system.

8-Halo-dGs

The chromatographic separation was performed by a gradient elution as follows: 0–5 min, water containing 0.1% formic acid; 5–18 min, linear gradient to 26% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid; 18–18.1 min, linear gradient to 100% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid; 18.1–24 min, acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid; 24–24.1 min, linear gradient to water containing 0.1% formic acid; 24.1–34 min, water containing 0.1% formic acid; flow rate = 0.2 ml/min. The instrument response was optimized by infusion experiments of the standard compounds using a syringe pump at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. 8-Halo-dGs were detected using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry in the multiple reaction monitoring mode. Specific transitions used to detect products in the positive ionization mode were those between the molecular cation of the products and the characteristic daughter ion formed from the loss of the 2′-deoxyribose moiety.

8-OxodG

The chromatographic separation was performed by a gradient elution as follows: 0–5 min, water containing 0.1% formic acid; 5–30 min, linear gradient to 50% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid; 30–30.1 min, linear gradient to water containing 0.1% formic acid; 30.1–40 min, water containing 0.1% formic acid; flow rate = 0.2 ml/min. Optimization of the instrument response was performed as for 8-halo-dGs.

Preparation of the Monoclonal Antibody to 8-BrdG

To couple 8-BrdG to protein, the 5′-succinyl-8-BrdG derivative (suc-8-BrdG) was synthesized. Briefly, 8-BrdG (6.5 mg, 18.9 μmol) and succinic anhydride (3.8 mg, 37.8 μmol) were dissolved in pyridine (1 ml), and the mixture was kept at room temperature with stirring. After 2 days, the same amount of succinic anhydride was added, and the mixture was kept overnight at room temperature. The solution was then evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in methanol. Suc-8-BrdG was isolated by reverse phase HPLC (Develosil C30, 8 × 250 mm) using 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid at a flow rate of 2.0 ml/min with monitoring at 280 nm. The obtained suc-8-BrdG (2.0 mg, yield 23.4%) was identified by 1H NMR and LC-MS measurements (m/z 330, 332). The carboxyl group of the obtained suc-8-BrdG was conjugated to the amino group of KLH or BSA by the carbodiimide procedure as described previously (23). The conjugate of suc-8-BrdG and KLH (8-BrdG-KLH) (0.6 mg/ml) was emulsified with an equal volume of complete Freund's adjuvant. Six-week-old female Balb/c mice were immunized with 100 μl of this emulsion intraperitoneally. After 2 weeks, the mice were boosted with the 8-BrdG-KLH (0.2 mg/ml) emulsified with an equal volume of incomplete Freund's adjuvant. In the final boost, 100 μl of the conjugate (0.5 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected intravenously. Three days after the final boost, the mouse was killed, and the spleen was removed for fusion with P3/U1 myeloma cells. The fusion was carried out by polyethylene glycol, and the cells were cultured in hypoxanthine/aminopterin/thymidine selection medium. Five days after the fusion, the culture supernatants of hybridomas obtained were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using 8-BrdG-BSA and untreated BSA as the coating agents. The positive hybridomas against the 8-BrdG-BSA were cloned by the limiting dilution method. After repeated screening and cloning, four specific clones were obtained. Among them, a clone (termed mAb8B3) was used in the following experiments because of its specificity and high ability for cell growth.

ELISA

The indirect noncompetitive ELISA procedure has been described previously (24). Briefly, 100 μl of antigen in PBS was coated in wells and kept at 4 °C overnight. After washing and blocking with 4% Block Ace (Dainihon Seiyaku), 100 μl of the mAb8B3 (1/2500 dilution) in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TPBS) was added, and the wells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After washing, 100 μl of anti-mouse IgG goat peroxidase-labeled antibody (1/5000 in TPBS) was added, and the wells incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing, 100 μl of reaction buffer (1% (w/v) 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine with 0.04% H2O2 in 40 mm citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 5.0) was added. The color developing reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 n H3PO4. The binding of the antibody to the antigen was evaluated by measuring the optical density at 450 nm.

Competitive indirect ELISA was performed for estimating the cross-reactivity of the low molecular weight compounds with the antibody. The 8-BrdG-BSA conjugate (0.05 μg/well) was used as the coating antigen. For the competitive reaction, 50 μl of competitors in PBS were mixed with an equal volume of the antibody (1/2500 dilution) in PBS containing 4% BSA. The competitor solution was kept at 4 °C overnight, and 90 μl of the mixture was used as the primary antibody. The cross-reactivity of the antibody to the competitors was expressed as B/B0, where B is the amount of antibody bound in the presence and B0 in the absence of the competitor.

Animal Experiments

Female Wistar rats (7 weeks old) were given an intraperitoneal injection of LPS from E. coli (3 mg/kg body weight; Sigma) in PBS or PBS alone. The rats were sacrificed at 2, 6, 12, 24, or 72 h after LPS/PBS, and the livers were immediately frozen until analysis. Rat urine was collected every 24 h from the day before LPS treatment to 10 days after administration. MPO−/− mice were developed and maintained as described previously (25). The mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of LPS (1 mg/kg of body weight) as described above. All of the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Immunohistochemistry

Livers were collected, fixed with buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. In the case of livers from MPO−/− and control C57BL/6 mice, the specimens were fixed with Bouin's fluid. The 3-μm tissue sections were affixed to slides, the specimens were deparaffinized, and antigen retrieval was performed by microwave treatment in 0.01 m citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min. After cooling the slides at room temperature for 20 min, 1 n HCl was added for 30 min (for the primary antibody of modified DNA). The sections were blocked with normal rabbit serum (DAKO) in 1% BSA/PBS for 30 min and washed three times with PBS; normal swine serum (DAKO) was used for the anti-MPO antibody. The primary antibody (1/100 dilution) was reacted at 4 °C overnight. After three PBS washes, biotinylated second anti-mouse IgG antibody (DAKO, 1/100 dilution) was reacted at room temperature for 40 min. Color development was achieved using the ABC-AP (alkaline phosphatase) kit (Vectastain) with a Vector Red commercial kit as the chromogen according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The specimens were finally counterstained with hematoxylin. Anti-3-nitrotyrosine (3-NO2Tyr) antibody was prepared as described previously (26). Anti-thymine glycol (Tg) antibody and dihalotyrosine antibody (27) were obtained from Nikken Zeil Co. Human samples were obtained from surgical operations. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine.

Extraction of 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG from Liver Tissue

Liver tissue resected at surgery was immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and frozen at −80 °C until analysis. The thawed tissue (100 mg of wet weight) was homogenized at 4 °C in 1 ml of extraction buffer (10 mm methionine, 4 m urea, 0.2 m NaCl, 0.5% sodium N-lauroyl sarcosine, 10 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). In brief, the homogenate was mixed with 20 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) and kept at 55 °C for 8 h. RNase (Qiagen; 16 μl) was added and incubated for 2 min. After vortexing for 15 s, 1 ml of phenol was mixed and gently shaken for 30 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 rpm at 4 °C. DNA was collected with phenol and chloroform/isoamylalcohol mixture according to a conventional protocol. Prior to the enzymatic digestion of DNA, the buffer was supplemented with isotope-labeled internal standards (15N5-labeled dG, 15N5-8-CldG, 15N5-8-BrdG, and 15N5-8-OxodG). DNA was extracted as described (22, 28). Enzymatic digestion of DNA with DNase I, nuclease P1, and alkaline phosphatase was performed as reported previously (29). After digestion, the reaction mixtures were filtered through ultrafree MC membrane (nominal molecular weight limit, 5000; Millipore) by centrifugation (10,000 rpm) to remove enzymes. 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG of the filtrates were fractionated by reverse phase HPLC, and 10 μl of the samples was injected for LC-MS/MS as described above. The multiple reaction monitoring for each compound was: 15N5-8-CldG (m/z 307.0 → 190.9), 8-CldG (m/z 302.1 → 185.9), 15N5-8-BrdG (m/z 350.9 → 235.0), 8-BrdG (m/z 345.9 → 229.9), 15N5-8-OxodG (m/z 288.9 → 173.1), and 8-OxodG (m/z 284.0 → 168.1), respectively.

MPO Activity of Rat Liver Tissue

Tissues were homogenized in 0.5% hexadecyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide, 50 mm KH2PO4 (pH 6) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. After 5 min, supernatant was added to the mixture of 150 μl of aqueous 2 mm H2O2 and 130 μl of aqueous 25 mm 4-aminoantipyrine/1% phenol. The solution was then reacted for 5 min. The absorbance at 510 nm was measured (A5). Instead of 2 mm H2O2/H2O, water was used as a standard (A0). The MPO activity was assessed by subtracting A0 from A5 and normalized to the liver weight.

Measurement of Thiobarbituric Acid-reactive Substances (TBARS) in Rat Liver Tissue

The lipid peroxidation levels were evaluated by measurement of the TBARS as described previously (30). In brief, each liver was homogenized in aqueous 1.15% KCl with 1% butylated hydroxytoluene. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, a portion of supernatant was diluted 50× with 1.15% KCl to measure the protein concentration. The supernatant (200 μl) was added to 225 μl of 20% acetic acid and 225 μl of 0.8% thiobarbituric acid and further incubated at 100 °C for 1 h. After cooling with water, the supernatant was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, and the absorption was measured at 532 nm. TBARS data were normalized to the protein concentration.

GSH of Rat Liver Tissue

The liver was homogenized in 0.1 m phosphate buffer containing 5 mm EDTA and 1% butylated hydroxytoluene (pH 7.4). Homogenate was diluted 50× with buffer. A 100-μl volume of 25 mm metaphosphoric acid was added to the sample (400 μl) and was ultracentrifuged at 47,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. A 50-μl volume of supernatant was reacted with 50 μl of 1 mg/ml o-phthalaldehyde in 900 μl of buffer for 15 min. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation of 355 nm and an emission of 460 nm.

Creatinine Assay

Urinary creatinine was determined by the Creatinine Test (WAKO) according to the manufacturer's recommendation.

Analysis of Urinary 8-Modified dG and Modified Tyrosines Using LC-MS/MS

Human urine was collected as a spot sample after approval by the Nakatsugawa Municipal Hospital committee (31). The age range was 56.8 ± 10.6 in healthy patients and 56.9 ± 11.0 in diabetic patients. There were five males and five females in each group. For estimation of modified dGs, urine was supplemented with each internal standard (15N5-8-CldG, 15N5-8-BrdG, and 15N5-8-OxodG). After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatant was diluted 10× with water and then fractionated. Partial fractionations of 8-modified dG were performed by reverse phase HPLC as described above. The samples (10 μl) were analyzed using LC-MS/MS as described above. Quantification of urinary modified tyrosines, 3-bromotyrosine, 3-chlorotyrosine, and 3-NO2Tyr, was performed as described previously (31).

Statistics

Statistical significance of the intergroup differences of means for multiple groups were determined using the Student Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test after one-way analysis of variance to determine variations among the group means, followed by Bartlett's test to determine the homogeneity of variance.

RESULTS

Reaction Requirement for 8-BrdG Production by the MPO-H2O2-Cl−-Br− System

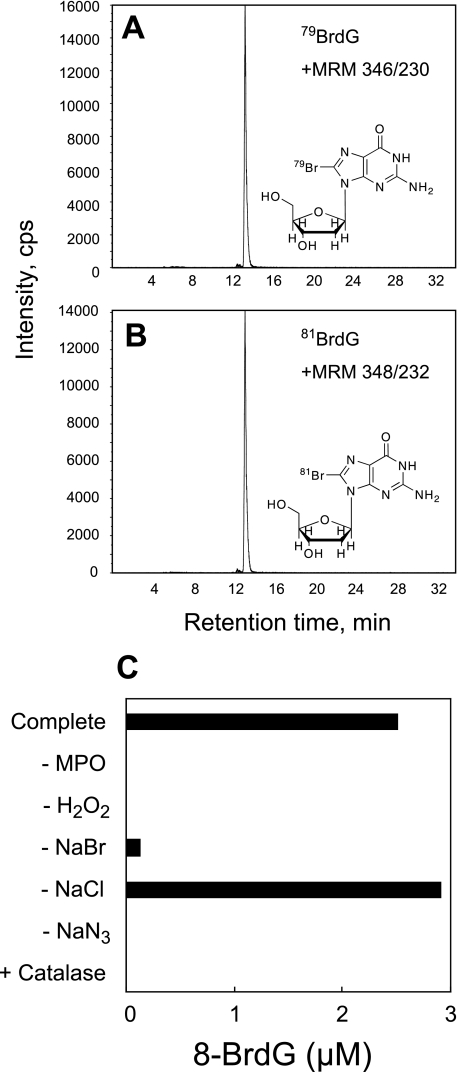

We characterized the bromination of dG by MPO using LC-MS/MS in vitro. During the incubation of dG with MPO and H2O2 in a phosphate buffer containing NaBr, a novel product was observed on the mass chromatogram, with a characteristic pattern of multiple reaction monitoring of [M + H+]346/230 and [M + H+]348/232, with similar intensities (Fig. 1, A and B). The formation of the collision-induced fragment ion (m/z 230 and 232) indicated the liberation of the deoxyribose moiety from the modified dG. The M + 2 isotopic pattern strongly suggested the incorporation of a bromonium atom into dG (79Br and 81Br). Furthermore, this mass spectra pattern was consistent with 8-BrdG, the predominant reaction product from dG and HOBr. Therefore, the product was identified as 8-BrdG.

FIGURE 1.

8-BrdG generation by the MPO-H2O2-Cl−-Br− system. dG (1 mm) was incubated with 20 nm MPO, 100 μm H2O2, 100 mm NaCl, and 100 μm NaBr in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 60 min at 37 °C. The reaction conditions were varied by adding or removing components as indicated. 8-BrdG was identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS. The scans of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for 79BrdG (346/230) and 81BrdG (348/232) generated from the MPO-H2O2-Cl−-Br− system were performed separately (A and B). Quantification of 8-BrdG was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures” (C). NaN3, 10 mm sodium azide; Catalase, 10 mg/ml catalase.

The formation of 8-BrdG required MPO and H2O2 and was blocked by adding catalase, a scavenger of H2O2 (Fig. 1C). The reaction could not be completely prevented even in the absence of NaBr, likely because the NaCl in the buffer was contaminated with Br− (6). The heme enzyme inhibitor, NaN3, inhibited the reaction. These results demonstrate that bromination of dG by MPO requires the active enzyme, Br−, and H2O2.

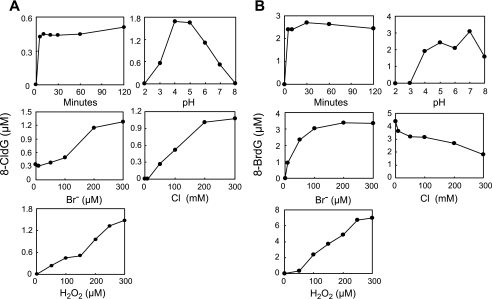

The effects of varying the reaction conditions on the generation of 8-BrdG and 8-CldG can be seen in Fig. 2. As a basal condition, dG (1 mm) was incubated with 20 nm MPO, 100 μm H2O2, 100 mm NaCl, and 100 μm NaBr in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Enzymatic bromination increased with H2O2 concentration up to 300 μm. At 100 μm of Br−, which is the physiological concentration of Br−, the yield of 8-BrdG reached a plateau. Both halogenations were completed within 30 min, and the optimal pH for 8-BrdG generation was ∼7. The production of 8-BrdG was decreased with increasing concentration of Cl−, suggesting a competitive reaction between Cl− and Br− with MPO.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of halogenation of dG by the MPO-H2O2-Cl−-Br− system. dG (1 mm) was incubated with 20 nm MPO, 100 μm H2O2, 100 mm NaCl, and 100 μm NaBr in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 60 min at 37 °C. The reaction conditions were varied by altering the concentration of hydrogen ions or the length of the reaction time. 8-CldG (A) and 8-BrdG (B) were quantified by LC-MS/MS.

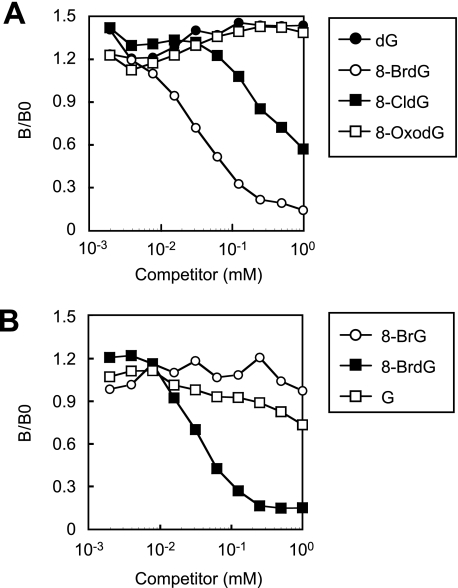

Preparation and Characterization of Monoclonal Antibody to 8-BrdG

We prepared a monoclonal antibody to 8-BrdG (mAb8B3) using 8-BrdG-conjugated KLH as an immunogen (Fig. 3). Synthetic 8-BrdG was chemically modified for succinylation, and the succinyl moiety was then coupled to a carrier protein, KLH, as described previously (24). Although the resulting antibody bound both 8-BrdG and 8-CldG, the reactivity against 8-BrdG was ∼10-fold higher than for 8-CldG. The antibody showed little cross-reactivity against 8-OxodG and 8-bromoguanosine and could therefore distinguish the 8-substituted moiety of dG and deoxyribose. Thus, the antibody was considered to be an antibody to 8-halo-dGs.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of the specificity of the monoclonal antibody against 8-halo-dGs. The cross-reactivity of the antibody (mAb8B3) with the 8-modified dG (A) or 8-substituted G (B) was estimated by competitive indirect ELISA. 8-BrG, 8-bromoguanine; G, guanosine.

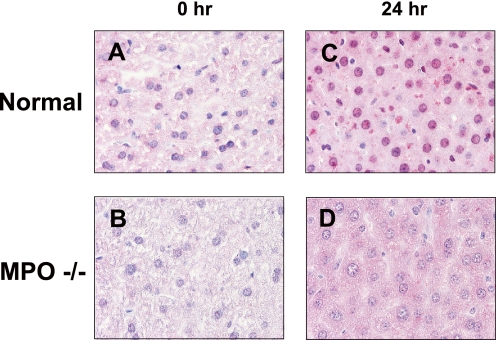

Chlorination is considered a consequence of MPO, whereas bromination is related to both MPO and eosinophil peroxidase. To confirm the availability of the antibody against MPO-derived halogenation in animals, we examined its immunoreactivity in the liver of LPS-treated wild type and MPO−/− mice. Following LPS treatment, 8-halo-dGs immunoreactivity was observed in the liver of wild type mice but not MPO−/− mice (Fig. 4), suggesting that the antibody can be used for estimation of MPO-derived modification. It is worthy to note that a weak signal in the cytoplasmic matrix was also observed.

FIGURE 4.

Immunohistochemical detection of 8-halo-dGs with mAb8B3 in the liver of wild type or MPO−/− mice treated with LPS. A, wild type normal mouse liver. B, control MPO−/− mouse liver. C, LPS 24 h wild type mouse liver. D, LPS 24 h MPO−/− mouse liver. All of the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Magnification was ×400.

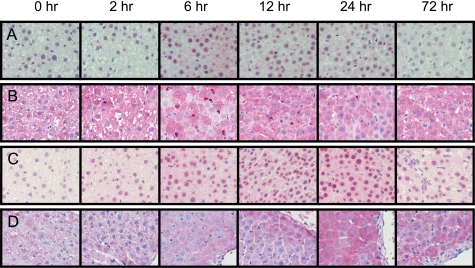

Immunohistochemical Detection of Oxidative Stress Markers in the Liver of LPS-treated Rats

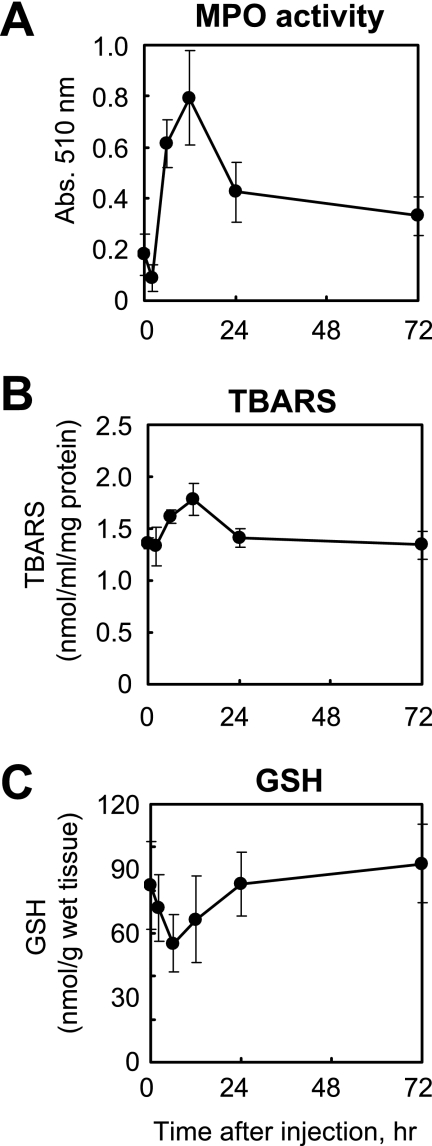

Immunostaining for oxidative stress markers, including the novel antibody to 8-halo-dGs, was examined in the livers of rats treated with LPS. The levels of MPO activity (i.e. a parameter of neutrophil infiltration) and TBARS (i.e. a parameter of lipid peroxidation) were significantly increased at 12 h after LPS treatment (Fig. 5, A and B). Moreover, a decrease of GSH (i.e. a parameter of reductant ability) was observed at 6 h after LPS treatment (Fig. 5C). Immunopositive staining was observed in the livers of LPS-treated rats for all of the antibodies used, although the staining patterns varied between the antibodies (Fig. 6). An increase in 8-halo-dGs and MPO immunoreactivity in the liver of LPS-treated animals was observed at 6 and 12 h, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B). By contrast, oxidized and nitrated products, 8-OxodG and 3-NO2Tyr, exhibited immunoreactivity at 12 and 24 h after LPS. Although the antibody to 3-NO2Tyr was solely stained in the cytosol, both halo-dGs and 8-OxodG were stained in both the nuclei and a certain amount of the cytosol. A summary of the various immunostainings can be seen in Table 1. N4,5-diCldC was previously detected by immunohistochemistry in LPS-treated mice (21). The time course of N4,5-diCldC immunostaining was consistent with that of 8-halo-dGs (Table 1). Tg is a well known oxidized dT, and the monoclonal antibody to Tg is commercially available. The time course of Tg immunostaining was similar to that of 8-OxodG (Table 1). These data further suggest that halogenation of dG is an early and transient event in tissue inflammation.

FIGURE 5.

Intraperitoneal LPS administration to rats affects activity of MPO, TBARS, and GSH in the liver. The activity levels of MPO (A), TBARS (B), and GSH (C) in the liver of rats after LPS treatment were measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

FIGURE 6.

Immunohistochemical detection of time-dependent generation of oxidative stress markers. 8-Halo-dGs (A), MPO (B), 8-OxodG (C), and 3-NO2Tyr (D) in the liver of rats treated with LPS were immunostained. All of the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Magnification was ×400.

TABLE 1.

Summary of LPS-induced immunoreactivity connected with halogenation, oxidation, and nitration

The levels of 8-halo-dGs, N4,5-diCldC, MPO, 3,5-dihalogenated Tyr (DihaloY), 8-OxodG, Tg, and 3-NO2Tyr were immunohistochemically detected. All of the antibodies (1 mg/ml) were diluted with PBS containing Tween 20 (1/100 dilution). The immunoreactivity intensity scale was: mostly negative (+/−), clearly positive (+), extremely positive (++), and negative (−). All of the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The time after injection is noted at the top of each column.

| Antibody | 0 h | 2 h | 6 h | 12 h | 24 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-Halo-dGs | − | − | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| N4,5-diCldC | − | − | +/− | +/− | − | − |

| MPO | − | − | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| DihaloY | − | +/− | +/− | ++ | + | +/− |

| 8-OxodG | − | +/− | + | ++ | ++ | +/− |

| Tg | +/− | +/− | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| 3-NO2Tyr | +/− | +/− | +/− | + | ++ | + |

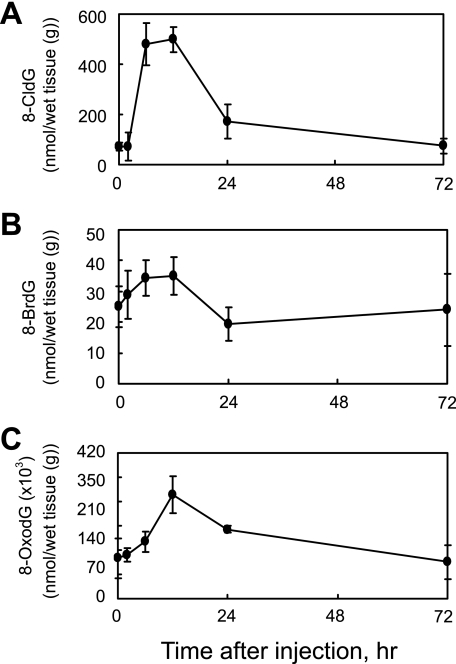

Quantification of LPS-induced Time-dependent Generation of 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG in Rat Liver Tissue by LC-MS/MS

To further investigate the time-dependent generation of modified dG in the liver of LPS-treated rats, we analyzed 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG using LC-MS/MS with stable isotopic method (Fig. 7). The LC-MS/MS method can simultaneously analyze 8-BrdG and 8-CldG and also provides accurate quantitation with chemical identification. The pattern of changes obtained by LC-MS/MS was similar to that obtained by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6). The generation of 8-halo-dGs, 8-CldG, and 8-BrdG began to increase between 2 and 6 h, peaked at 12 h, and then decreased to levels near that of control (0 h, PBS treatment only) at 24 h after LPS. By contrast, the level of 8-OxodG at 24 h remained higher than control levels, suggesting that 8-halo-dGs have different repair mechanisms than 8-OxodG.

FIGURE 7.

LPS-induced change of 8-modified dG in the rat liver. Quantification of 8-modified dG (A, 8-CldG; B, 8-BrdG; C, 8-OxodG) in the livers of LPS-treated rats was performed by LC-MS/MS using internal standards. Briefly, 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG were detected in the liver after DNA extraction, DNA digestion, and fractionated by HPLC supplemented with the internal standards 15N5-8-CldG, 15N5-8-BrdG, and 15N5-8-OxodG. The multiple reaction monitoring for each compound was: 15N5-8-CldG (m/z 307.0 → 190.9), 8-CldG (m/z 302.1 → 185.9), 15N5-8-BrdG (m/z 350.9 → 235.0), 8-BrdG (m/z 345.9 → 229.9), 15N5-8-OxodG (m/z 288.9 → 173.1), and 8-OxodG (m/z 284.0 → 168.1), respectively.

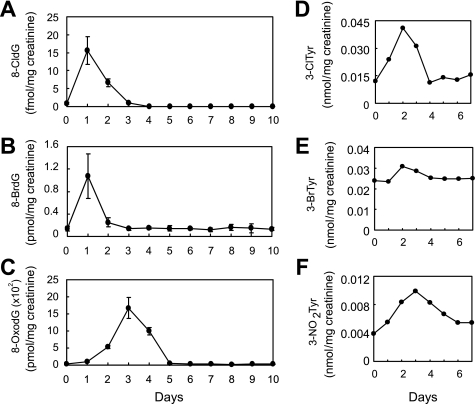

Urinary 8-Halo-dGs and 8-OxodG Analysis in LPS-treated Rats

It was reported that 8-OxodG generated in DNA was excreted by human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (hOGG1) as a repair pathway (32). The hOGG1 enzyme catalyzes expulsion of the 8-OxodG and cleavage of the DNA backbone. Similarly, 8-halo-dGs may also be excreted to urine by a repair enzyme. Urine from LPS-treated rat was collected every 24 h for 10 days. The samples containing 8-halo-dGs were partly purified by HPLC and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The LPS-induced change in 8-halo-dGs and 8-OxodG in the urine of rats can be seen in Fig. 8 (A–C). At 1 day after LPS treatment, elevated levels of 8-CldG and 8-BrdG were detected in urine, whereas 8-OxodG levels remained similar to controls. An increased excretion of 8-OxodG was observed at 3 days after LPS treatment. These data suggest that excretion of 8-halo-dGs into the urine in LPS-treated rats occurred earlier than for 8-OxodG.

FIGURE 8.

LPS-induced change of modified dGs and tyrosines in rat urines. A–C, urine of rats was diluted 5× by water. The fraction containing 8-modified dG for the samples was collected by HPLC. Quantification of 8-modified dG (A, 8-CldG; B, 8-BrdG; C, 8-OxodG) in fractions was performed by LC-MS/MS using internal standards as described in legend to Fig. 7. D–F, urine was supplemented with each internal standard before solid phase extraction. After the extraction, 3-chlorotyrosine (3-ClTyr), 3-bromotyrosine (3-BrTyr), and 3-NO2Tyr were derivatized with butanol and HCl. Quantification of 3-chlorotyrosine (D), 3-bromotyrosine (E), and 3-NO2Tyr (F) in the urine of rats treated with LPS was performed by LC-MS/MS using internal standards.

Comparison with Modified Tyrosine Markers in Urine

3-Chlorotyrosine, 3-bromotyrosine, and 3-NO2Tyr are used to evaluate oxidative modification, including MPO-derived protein modification in particular. Quantification of modified tyrosines in urine of LPS-treated rats over 1 week was performed by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 8, D–F). The levels of halogenated tyrosines were increased at 2 days, and the levels of 3-NO2Tyr peaked at 3 days after LPS treatment. Thus, these modified tyrosines were excreted more slowly than for 8-halo-dGs.

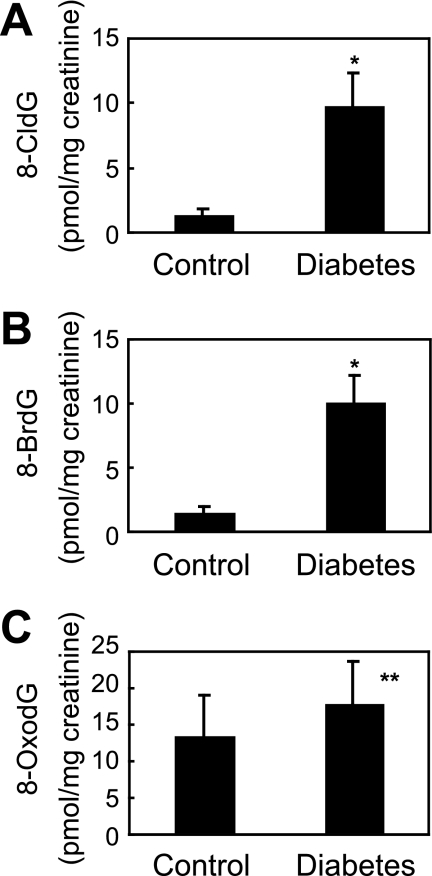

Urinary 8-Halo-dGs and 8-OxodG Analysis in Diabetic Patients

The basal level of 8-halo-dGs was analyzed in urine from healthy volunteers (n = 10). The urine concentration of 8-halo-dGs (8-CldG and 8-BrdG) was 1.25 ± 0.65 and 1.38 ± 0.63 pmol/mg of creatinine, respectively, whereas the concentration of 8-OxodG was 15.1 ± 5.71 pmol/mg of creatinine. Diabetes is thought to be associated with oxidative stress because numerous studies show a relationship between oxidative stress markers and diabetes (31, 33). In the present study, urinary 8-CldG and 8-BrdG levels from diabetic patients (n = 10, 9.68 ± 2.64 and 10.0 ± 2.15 pmol/mg of creatinine, respectively) were 8-fold higher than basal levels in healthy volunteers (p < 0.0001), whereas there was a small increase in 8-OxodG in diabetic patients (22.9 ± 6.02 pmol/mg of creatinine, p < 0.001) (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Quantification of 8-CldG, 8-BrdG, and 8-OxodG in control and diabetic human urine using LC-MS/MS. Human urine with protein removed was fractionated by HPLC and then dried. After resolving in 50 μl of diluted solution (water:acetnitrile = 1:1), 10 μl of samples was analyzed by LC-MS/MS. *, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.001.

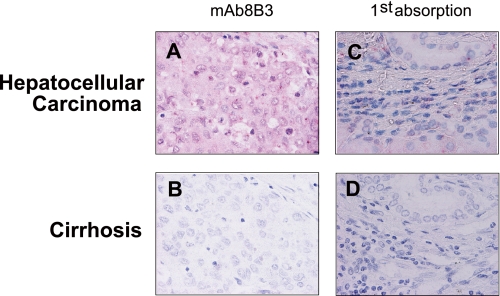

8-Halo-dGs Immunostaining at an Advanced Stage of Inflammation

As shown above, 8-halo-dGs seem to be an early marker of inflammation-derived oxidative tissue damage. We attempted to detect the 8-halo-dGs antigen in human hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis, which may be models of advanced stage of inflammatory diseases. Interestingly, although no positive staining was observed in human cirrhosis, the nuclei and cytoplasmic matrix of cells from hepatocellular carcinoma showed significant 8- halo-dG staining (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Immunohistochemical detection of 8-halo-dGs in human livers with cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. The sections of hepatocellular carcinoma (A) and cirrhosis (B) livers were immunostained with mAb8B3. Competitive experiments were performed by preincubation with respective antigens (C and D). All of the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Magnification was ×400.

DISCUSSION

MPO is a heme protein secreted by phagocytic white blood cells. Its physiological function is to utilize the H2O2 produced by membrane-associated NADPH oxidase to generate bactericidal and cytotoxic intermediates. The major physiological substrate of MPO is considered to be Cl−, resulting in generation of HOCl, the bactericidal agent. In addition to Cl−, MPO can utilize Br−, I−, SCN− (34), NO2− (15), and tyrosine (16, 17) to generate HOBr, HOI, HOSCN, 3-NO2Tyr, and dityrosine, respectively, as intermediates and products. Furthermore, MPO acts as a major catalyst for initiation of lipid peroxidation (35). Therefore, MPO catalyzes halogenation, nitration, and oxidation at sites of inflammation. However, a detailed mechanism for the formation of halogenated, nitrated, and oxidized products in vivo has not been fully established. DNA is considered an important target of modification because of the potential for inducing gene mutation, and various modifications of DNA bases by MPO-derived species have been described (18–22). However, although chlorination of dG has been reported (22), there are limited data on dG halogenation.

In the present study we estimated the modification of dG using the MPO-H2O2-Br− system, and formation of 8-BrdG was then confirmed by LC-MS/MS. A novel antibody to 8-BrdG (mAb8B3) was also prepared that recognized both 8-BrdG and 8-CldG. In general, LC-MS/MS enables quantification of targets with high selectivity and sensitivity, whereas immunohistochemistry is useful for evaluating the presence and localization of target antigens in vivo. Thus, we assessed the damage in LPS-treated rat using both LC-MS/MS and immunohistochemistry.

The antibody to 8-halo-dGs did not react with tissue derived from MPO−/− mice, suggesting that 8-halo-dGs were specifically generated by MPO (Fig. 4). MPO catalyzed both 8-BrdG and 8-CldG formation reactions under physiological conditions (Fig. 2). The immunoreactivity of the 8-halo-dGs antibody against pure 8-BrdG was much higher than against 8-CldG (Fig. 3). However, because the concentration of 8-CldG in a biological sample was ∼10-fold higher than that of 8-BrdG (Fig. 8), it was difficult to estimate the contributions of the different 8- halo-dGs to the specimen staining.

LPS-induced liver damage occurred in the rats at 6 and 12 h after LPS treatment (Fig. 6). A 300% increase in MPO activity and leukocyte infiltration was observed in LPS-treated animals compared with control animals. In support of these data, MPO-derived halogenated DNA bases, 8-halo-dGs and N4,5-diCldC, dihalogenated tyrosine, and MPO were also detected by immunohistochemistry in the liver of rats at 6 and 12 h after LPS exposure (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Positive immunostaining for the oxidized DNA bases (8-OxodG and Tg) and the nitrated protein marker 3-NO2Tyr were observed at 12 and 24 h after LPS treatment. Furthermore, halogenation of dG occurred earlier than oxidation of dG (Fig. 8). The LC-MS/MS results (Fig. 7) suggest that 8-halo-dGs immunoreactivity (Fig. 6) should be due to the expression of both 8-CldG and 8-BrdG. A compound that is rapidly and transiently formed during inflammation, like halo-dGs, should be suitable as an early oxidative stress biomarker for monitoring complicated inflammation processes.

Some positive staining of 8-halo-dGs in the cytoplasmic matrix as well as the nuclei was observed (Figs. 4, 6, and 10). It is possible that the staining was due to a nonspecific immunoreaction. Concerning the nitration of the nucleotide, the immunostaining of 8-nitroguanosine in the cytosol has been demonstrated (36, 37). In these reports, the 8-nitroguanosine was localized mainly in the cytosol of virus-infected mouse lungs (36) and cultured cells (37). The authors have suggested the nitroguanosine is stably formed in the nucleotide pool and RNA in the cytosol of the cells. This may apply to halogenation of DNA. Our antibody to 8-BrdG, which recognizes 8-CldG as well, hardly reacts with 8-bromoguanosine (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the antibody detects neither halogenated RNA nor halogenated guanosine. 8-Halo-dG moieties could be directly generated from free dG in the nucleotide pool. Weak immunoreactivity of 8-OxodG was found in cytoplasmic matrix (Fig. 4D). It has been reported that 8-OxodG was accumulated in the cytoplasm as well as the nuclei in glioblastoma in some cases (38). The nucleotide pool is considered to be an important target of 8-OxodG generation for oxidative stress (39).

Urine 8-OxodG is generally used as a marker of oxidative stress. 8-OxodG is produced by reactive oxygen species under oxidative stress and excreted into the urine following recognition by the repair enzyme, hOGG1. The dedicated repair pathway for 8-OxoG was reported to involve hOGG1, an enzyme that recognizes oxoG-C base pairs and catalyzes exclusion of the 8-OxoG and cleavage of the DNA backbone (32). The repaired 8-OxodG was shown to be excreted into urine, although there may be some further oxidation (40). hOGG1 has also been shown to recognize the distortion of N-glycosyl bonds (41). Furthermore, in organic chemistry, bromination of a base is usually employed to change an N-glycosyl bond from anti to syn, whereas the stability of an oligonucleoside containing 8-BrdG is lower than that of dG (42). In the present study, although urine 8-halo-dG levels increased rapidly following LPS, there was a slower rise in 8-OxodG (Fig. 8). Thus, the early increase in urine 8-halo-dGs in LPS-treated rats may also reflect the fact that 8-halo-dGs are easily catalyzed by DNA repair enzymes, such as hOGG1.

Interestingly, the levels of 8-halo-dGs were significantly elevated in the urine of diabetic patients (Fig. 9), a disease considered to be associated with oxidative stress and inflammation (33). It was previously shown that the 8-OxodG levels in the urine were affected by age, gender, and degree of disease (43). In the present study, urine 8-halo-dGs were not affected by gender in either healthy or diabetic patients (data not shown); however, as yet we have not assessed enough samples, and a more detailed study is required. There was significant staining of hepatocellular carcinoma cells with the anti-8-halo-dG antibody (Fig. 10). This may relate to active gene transcription or replication processes, which increase the chance of mutation by reactive species or incorporation of a pooled modified dG. Conversely, there was no anti-8-halo-dGs immunostaining in liver tissue from cirrhosis patients. The detection of MPO and HOCl-modified protein in the human liver, including those with cirrhosis, has been reported (44), although decreased production of reactive oxygen species by neutrophils in patients with liver cirrhosis was also demonstrated (45). This reduction in reactive oxygen species may cause a reduced halogenating ability in the cirrhotic liver, because MPO requires hydrogen peroxide as a substrate to catalyze the production of halogenating species. In addition, we have found that 8-BrdG was effectively generated by bromamines rather than HOBr itself in vitro.3 Thus, intracellular amines including nucleotides could act as halogenating species (as a carrier) in vivo.

In summary, we successively quantified the halogenated, oxidized, and nitrated products in the liver and urine of rats treated with LPS and suggest that halogenation might occur earlier than nitration and oxidation in this model. The levels of urinary 8-halo-dGs were relatively low compared with 8-OxodG but still detectable even in control subjects. Furthermore, the levels of urinary 8-halo-dGs in diabetic patients were higher than in control subjects. These data suggest that leukocyte-derived halogenated products such as 8-halo-dGs have potential as novel and early biomarkers of oxidative stress for assessment of inflammatory damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Akihiro Yoshida (Nakatsugawa Municipal Hospital) and Michitaka Naito (Sugiyama University Graduate School) for kindly supplying diabetic and control urine.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, by the COE Program in the 21st Century in Japan, and by research fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

T. Asahi and T. Osawa, unpublished results.

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- dG

- 2′-deoxyguanosine

- N4,5-diCldC

- N4,5-dichloro-deoxycytidine

- 8-CldG

- 8-chloro-2′-deoxyguanosine

- 8-BrdG

- 8-bromo-2′-deoxyguanosine

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- LC-MS/MS

- LC tandem mass spectrometry

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- 8-OxodG

- 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- KLH

- keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- suc-8-BrdG

- 5′-succinyl-8-BrdG

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Tg

- thymidine glycol

- 3-NO2Tyr

- 3-nitrotyrosine

- TBARS

- thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

- 8-halo

- 8-halogenated

- dC

- 2′-deoxycytidine

- hOGG1

- human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hazen S. L., Heinecke J. W. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2075–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohshima H., Bartsch H. (1994) Mutat. Res. 305, 253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeshita J., Byun J., Nhan T. Q., Pritchard D. K., Pennathur S., Schwartz S. M., Chait A., Heinecke J. W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3096–3104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitzman S. A., Gordon L. I. (1990) Blood 76, 655–663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson J. P., Byun J., Heinecke J. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33440–33448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson J. P., Byun J., Mueller D. M., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2052–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen Z., Mitra S. N., Wu W., Chen Y., Yang Y., Qin J., Hazen S. L. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2041–2051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman H., Halliwell B. (1996) Biochem. J. 313, 17–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert C. J., Thukkani A. K., Heuertz R. M., Slungaard A., Hazen S. L., Ford D. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8942–8950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domigan N. M., Charlton T. S., Duncan M. W., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16542–16548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazen S. L., Hsu F. F., Mueller D. M., Crowley J. R., Heinecke J. W. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1283–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda M., Suzuki T., Friesen M. D., Ravanat J. L., Cadet J., Pignatelli B., Nishino H., Ohshima H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40486–40496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thukkani A. K., Albert C. J., Wildsmith K. R., Messner M. C., Martinson B. D., Hsu F. F., Ford D. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36365–36372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaut J. P., Yeh G. C., Tran H. D., Byun J., Henderson J. P., Richter G. M., Brennan M. L., Lusis A. J., Belaaouaj A., Hotchkiss R. S., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11961–11966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eiserich J. P., Hristova M., Cross C. E., Jones A. D., Freeman B. A., Halliwell B., van der Vliet A. (1998) Nature 391, 393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinecke J. W. (2002) Toxicology 177, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinecke J. W., Li W., Daehnke H. L., 3rd, Goldstein J. A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4069–4077 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byun J., Henderson J. P., Heinecke J. W. (2003) Anal. Biochem. 317, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson J. P., Byun J., Takeshita J., Heinecke J. W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23522–23528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson J. P., Byun J., Williams M. V., McCormick M. L., Parks W. C., Ridnour L. A., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1631–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai Y., Morinaga H., Kondo H., Miyoshi N., Nakamura Y., Uchida K., Osawa T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51241–51249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badouard C., Masuda M., Nishino H., Cadet J., Favier A., Ravanat J. L. (2005) J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 827, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato Y., Mori Y., Makino Y., Morimitsu Y., Hiroi S., Ishikawa T., Osawa T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20406–20414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato Y., Makino Y., Osawa T. (1997) J. Lipid Res. 38, 1334–1346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aratani Y., Koyama H., Nyui S., Suzuki K., Kura F., Maeda N. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 1828–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beckmann J. S., Ye Y. Z., Anderson P. G., Chen J., Accavitti M. A., Tarpey M. M., White C. R. (1994) Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 375, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato Y., Kawai Y., Morinaga H., Kondo H., Dozaki N., Kitamoto N., Osawa T. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyokuni S., Tanaka T., Hattori Y., Nishiyama Y., Yoshida A., Uchida K., Hiai H., Ochi H., Osawa T. (1997) Lab. Invest. 76, 365–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang X., Powell J., Mooney L. A., Li C., Frenkel K. (2001) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31, 1341–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi Y., Nakae D., Akai H., Kishida H., Okajima E., Kitayama W., Denda A., Tsujiuchi T., Murakami A., Koshimizu K., Ohigashi H., Konishi Y. (1998) Carcinogenesis 19, 1809–1814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato Y., Dozaki N., Nakamura T., Kitamoto N., Yoshida A., Naito M., Kitamura M., Osawa T. (2009) J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 44, 67–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruner S. D., Norman D. P., Verdine G. L. (2000) Nature 403, 859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baynes J. W., Thorpe S. R. (1999) Diabetes 48, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furtmüller P. G., Burner U., Obinger C. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 17923–17930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang R., Brennan M. L., Shen Z., MacPherson J. C., Schmitt D., Molenda C. E., Hazen S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46116–46122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akaike T., Okamoto S., Sawa T., Yoshitake J., Tamura F., Ichimori K., Miyazaki K., Sasamoto K., Maeda H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 685–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshitake J., Akaike T., Akuta T., Tamura F., Ogura T., Esumi H., Maeda H. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 8709–8719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iida T., Furuta A., Kawashima M., Nishida J., Nakabeppu Y., Iwaki T. (2001) Neuro. Oncol. 3, 73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haghdoost S., Sjölander L., Czene S., Harms-Ringdahl M. (2006) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41, 620–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T., Ohshima H. (2002) FEBS Lett. 516, 67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatnagar S. K., Bullions L. C., Bessman M. J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9050–9054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fàbrega C., Macías M. J., Eritja R. (2001) Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 20, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura S., Yamauchi H., Hibino Y., Iwamoto M., Sera K., Ogino K. (2006) Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 98, 496–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown K. E., Brunt E. M., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Am. J. Pathol. 159, 2081–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Itoh K., Nakao A., Kishimoto W., Itoh T., Harada A., Nonami T., Nakano M., Takagi H. (1993) Gastroenterol. Jpn. 28, 541–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]