Abstract

Purpose: To describe caregivers’ constructions of their caregiving role in providing care to elders they knew were dying from life-limiting illnesses. Design and Methods: Study involved in-depth interviews with 27 family caregivers. Data were analyzed using constant comparative analysis. Results: Four categories were identified: centering life on the elder, maintaining a sense of normalcy, minimizing suffering, and gift giving. Generative caregiving was the term adopted to describe the end-of-life (EOL) caregiving role. Generative caregiving is situated in the present with a goal to enhance the elder’s present quality of life, but also draws from the past and projects into the future with a goal to create a legacy that honors the elder and the elder–caregiver relationship. Implications: Results contribute to our knowledge about EOL caregiving by providing an explanatory framework and setting the caregiving experience in the context of life-span development.

Keywords: Informal caregiving, Death and dying, End-of-life care

Every year, more than 1.7 million elders (65+ years of age) die in the United States (Heron et al., 2009). Of these, many thousands die as a result of life-limiting illnesses such as cancer, heart failure, renal failure, and chronic obstructive lung disease (Heron et al., 2009) and most of those receive intensive end-of-life (EOL) care from informal caregivers (mostly family members) prior to death (Wolff, Dy, Frick, & Kasper, 2007). Although some caregivers learn about the EOL caring role as a result of interactions with hospice staff, many do not. Data show, for example, that even though 82% of hospice patients are elders, hospice is involved in less than half of all deaths in the United States (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [NHPCO], 2008). In addition, although dying trajectories for many life-limiting illnesses including cancer can extend over months and even years (Lunney, Lynn, & Hogan, 2002), the median length of hospice service is only about 20 days (NHPCO, 2008). Therefore, although some caregivers receive instructions from hospice personnel about the role as it unfolds, many construct the EOL caregiving role with little or no preparation and sparse input from health care providers until very late in the dying trajectory. This article presents an analysis of qualitative data collected in a study of factors that influence decisions about everyday activities made by family members providing care to elders with life-limiting illnesses. This analysis focuses on describing the EOL caregiving role as constructed by caregivers and reported in the data.

Caregiving for chronically ill elders has been the focus of intense study for the past three decades. Based on this literature, we know quite a bit about caregivers, the difficulties they encounter, the positive and negative outcomes of caregiving for caregivers, and interventions for improving outcomes for caregivers. In addition, research has described the tasks caregivers perform. Schumacher, Beck, and Marren (2006) identified four categories of tasks: (a) physical maintenance and instrumental activities of daily living; (b) tasks requiring nursing or problem-solving skills such as symptom management; (c) tasks requiring communication or organizational skills such as arranging for services and communicating with health care providers; and (d) the “invisible aspects of care,” which include a host of anticipatory and supervisory activities supportive to elders. Therefore, evidence indicates multiple aspects to the role and the skills required vary in complexity. Research also indicates caregivers perform different tasks in hospitals (Collier & Schirm, 1992; Li, Stewart, Imle, Archbold, & Felver, 2000) compared to nursing homes (Bowers, 1987; Maas, Buckwalter, & Kelley, 1991) or homes (Bowers, 1987; Messecar, Archbold, Stewart, & Kirschling, 2002). Tasks performed can also be influenced by the caregiver’s (and elder’s) gender and the relationship between elder and caregiver (Beeson, Horton-Deutsch, Farran, & Neundorfer, 2000; Ducharme et al., 2006). Thus, the way caregivers construct their role is context dependent.

We also know how caregivers think about what they do or the purpose they ascribe to their activities. Bowers (1987) described five categories of family caregiving: Anticipatory caregiving, done in anticipation of potential problems and future need; preventive caregiving, done to prevent illness, injury, or health problems; supervisory caregiving, done to assure others are appropriately providing care; instrumental caregiving, done to provide physical, emotional, social, and/or financial support; and protective caregiving, done to protect elder from threats to self-image and assaults to personal dignity. Therefore, we know caregivers ascribe different purposes to the tasks they perform.

These studies of caregiving for the chronically ill and elders with dementia provide a basis for understanding the role constructed by EOL caregivers, but there are also fundamental differences that may influence how the role is constructed, for example: (a) the goal of EOL caregiving is palliative rather than curative, (b) the caregiving is characterized by an acute sense of finality, and (c) the caring interactions have the potential to evoke intense emotions that may not occur in other caregiving situations. In acknowledgement of fundamental differences, there is an evolving body of literature focusing specifically on EOL caregivers, including research on caregiving for elders with specific life-limiting conditions (e.g., Doorenbos et al., 2007; Exley, Field, Jones, & Stokes, 2005; Morrison & Lyketsos, 2005; Schumacher et al., 2008). Like other literature on caregiving, most studies of EOL caregiving focus on the difficulties and needs of caregivers (Marco, Buderer, & Thum, 2005; Redinbaugh, Baum, Tarbell, & Arnold, 2003; Wolff et al., 2007), the positive and negative outcomes for caregivers (Fletcher et al., 2009; Gaugler et al., 2004; Grbich, Parker, & Maddocks, 2001; Kim, Schulz, & Carver, 2007; Milberg & Strang, 2004; Perreault, Fothergill-Bourbonnaism, & Fiset, 2004; Schumacher, Stewart, & Archbold, 2007), and interventions for improving care and improving outcomes for caregivers (Kozachik et al., 2001; Kwak, Salmon, Acquaviva, Brant, & Egan, 2007; Walsh & Schmidt, 2003). In addition, a few studies have focused on the skills required to perform EOL caregiving activities (Schumacher, Beidler, Beeber, & Gambino, 2006). Overall, however, very few studies have described how caregivers who are caring for elders they know are dying construct their role—what they do as well as how they do it and the purpose they ascribe to their activities.

Given gaps in the literature, this analysis was undertaken to describe caregivers’ perspectives of the EOL caregiving role in providing care to elders dying from life-limiting illnesses. Symbolic interactionism and the social constructionist view were the theoretical underpinnings. Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical perspective that asserts actions arise from the dynamic relationship between actions and meanings and that meanings are embedded in social interactions with others (Charmaz, 2006). The social constructionist view asserts that people actively construct social realities and views of themselves based on interactions with others, their interpretations and perceptions of reality, and reflections on their interactions and experiences (O’Connor, 2007).

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Arizona approved the study protocol, which involved an exploratory methodology using intensive, semistructured interviews with EOL caregivers as the data sources. Caregivers were recruited via presentations and flyers distributed at hospice bereavement groups, flyers distributed in the offices of three geriatricians, and advertisements placed in local newspapers. Caregivers volunteered by expressing their interest in participating to the presenter, expressing their interest to the geriatrician and giving permission for release of their names, or calling the telephone number provided.

Sample

Caregivers were adults who had provided in-home physical care and emotional support for at least 3 months at home to a family member who was 65 years or older, were aware that the elder was “terminal” while the caregiving was occurring, and were at least 3 months but no more than 12 months past the elder’s death.

Procedure

Caregivers were screened by the primary author to identify the time and circumstances of the elder’s death, their relationship to the elder, and their willingness to participate. Eight individuals were excluded during the screening because the caregiver described a “sudden death,” that is, the elder had not been chronically ill and/or the caregiver was “surprised” that the elder had died. Most interviews, which lasted from 45 min to 2 hr, were conducted in the caregivers’ homes.

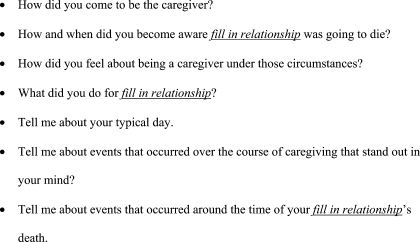

Prior to the interview, caregivers were informed of their rights as human subjects and asked to sign the approved consent form. After collecting descriptive information, the tape-recorded interview took place using semistructured open-ended questions. Interviews were very informal with the goal to elicit caregivers’ stories about their experience and their everyday care activities, decisions, and dilemmas. Every interview began with a “grand tour” question: “Tell me about your experiences in providing care to your fill in relationship.” Usually this question elicited a great deal of information, but depending on the answer, prompts (Figure 1) were used to elicit specific information. Questions about the circumstances surrounding specific decisions and dilemmas were also asked along with a question eliciting a story about the death, itself. Interviews ended with a question about what the caregiver would tell other caregivers about the role and a question about what the caregiver would tell the health professionals involved in the care about their experience.

Figure 1.

Examples of prompts used.

Tape recordings were transcribed verbatim creating electronic transcripts. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by the interviewer, and the tape recordings were destroyed after analysis.

Data Analysis

Constant comparative analysis (Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was used to generate themes and categories from the data. Statements about the caregiving role were identified and extracted from the stories. Extracted statements made by different caregivers were compared to each other for similarities and differences. Similar statements were grouped together to form themes. Themes were clustered under broader categories, which were then labeled and defined. Initially, data from spouses and “children” were analyzed separately, but few important differences were seen. Therefore, all data were grouped together. All categories were well saturated, meaning they were represented by comments made by both spouses and children, and each category was substantiated by data from at least three spouses and three children.

Trustworthiness of the study was addressed through use of standard qualitative research techniques (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Sandelowski, 1986). Initially, the authors independently coded two interviews and discussed the results. After that, the primary author did most of the coding, but the authors continued to collaborate in the development of the coding categories and definitions. Coding and themes were validated via consensus between the authors. Field notes and memoing were used to assist in data analysis and interpretation, minimize researcher bias in interpretation of the data, and maintain consistency as coding evolved. An audit trail was created noting coding decisions over the course of the study. The two investigators agreed on the descriptive themes and data interpretation through discussion and the process of exchanging iterative drafts of manuscripts and written reports. Authenticity of the analysis was judged by peer debriefing.

Results

Description of the Sample

The sample consisted of 27 caregivers (Table 1) who described caring for 30 elders. (Three daughters had provided care to two dying parents at the same time.) Caregivers provided care to elders from 5 months to 18 years with most providing care for around 3 years and most indicated that they knew the elder was going to die from the onset of the caregiving. Most elders (N = 17) had multiple comorbidities; three died from falls and one died from an ischemic bowel prior to succumbing to their life-limiting illnesses. One elder fractured her hip in the midst of the EOL caregiving. Twenty-two elders had hospice services. The length of hospice services ranged from 1 day to 18 months, but most had services for less than 2 months.

Table 1.

Description of the Sample

| Relationships (n) | |

| Spouses | |

| Husbands | 2 |

| Wives | 11 |

| “Children” | |

| Daughters | 7 |

| Daughters-in-law | 2 |

| Stepdaughter | 1 |

| Nieces | 2 |

| Sons | 2 |

| Ages in years | |

| Caregivers | Average = 63; Range = 39–86 |

| Elders | Average = 83; Range = 65–101 |

| Race/Ethnicity (n) | |

| Caucasian | 25 |

| Mexican American | 2 |

| Length of relationship in years | |

| Spouses | Average = 43; Range = 3–63 |

| Children | Average = 50; Range = 15–60 |

| Life-limiting illnesses (n) | |

| Cancer | 10 |

| Heart failure | 6 |

| COPD | 3 |

| Kidney failure | 2 |

| Failure to thrive | 7 |

| ALS | 1 |

| Lewy’s body dementia | 1 |

| Place of death (n) | |

| Home | 13 |

| Hospital | 4 |

| Emergency department | 3 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 2 |

| Assisted living facility | 3 |

| In-patient hospice | 5 |

Constructions of the EOL Caregiving Role

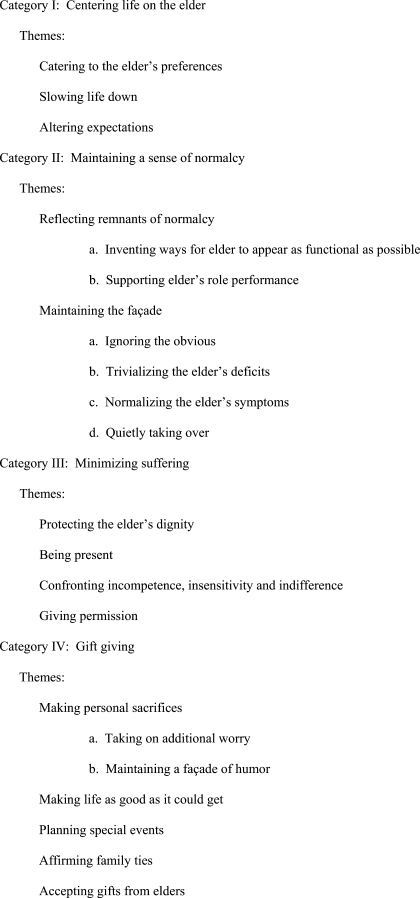

Data analysis revealed four predominant categories associated with caregivers’ constructions of the EOL caregiving role: centering life on the elder, maintaining a sense of normalcy, minimizing suffering, and gift giving (Figure 2). Each category contained several themes, which are represented in italicized text.

Figure 2.

Categories and themes.

Centering Life on the Elder

This category involved fixing the focus of life on the needs of the elder, almost to the exclusion of all other foci. Catering to the elder’s preferences was a major theme. Catering to the elder’s preferences affected the way instrumental activities were approached, for example, “He wanted so many different drinks and he’d just take little sips off each one. He wanted V-8 and he wanted Gatorade and he wanted watermelon with ice … . We did everything he wanted.” It affected how health and medical needs were met, for example, “The nurse tried to get her to take a pain pill and she made a face for the water. Then she made a face when she tried to have her take the Ensure. I said, ‘Get her a beer. She’ll drink the beer. What’s it gonna do, kill her?’ So we popped the beer and put a straw in it and she sucked that baby down with the pill.” It also affected the way caregivers advocated for the elder in relationship to health professionals (Table 2, Example 1) and decisions caregivers made about the where and how the death would occur (Table 2, Example 2).

Table 2.

Category I: Centering Life on the Elder

| Example 1 | She’s, “I’m going home. I’m going home. I’m going home. Where’s my son?” Then they came out to me and said. “You’ve got power of attorney you can put her in [the hospital].” I said, “The reason I have power of attorney is to give her what she wants. She doesn’t want to go in. I’m not gonna tell my own mother that I hold power of attorney and she’s going in if she doesn’t want to go in, regardless of the consequences. She has advance directives. She wants to lead these days in her life the way she wants to, and that’s it.” It was a tough battle actually. They were in and out of there for 45 minutes and they asked me to go in there and try and convince her. I said, “I’ll go in and ask her, but I’m not [forcing her], and you can’t either.” |

| Example 2 | No matter what, he was not going to a nursing home. He was not going to a hospice facility. I knew my dad. He’s old fashioned and his Italian culture—they want to die at home. I knew that my dad wanted to die at home. I don’t remember if we ever talked about it, but I knew in my mind that it was what he wanted. It was the right thing. |

Slowing life down so the elder could participate was a second theme. The following example shows how, for example, instrumental activities were “slowed down.” “I would have to start getting her to bed about 1:15 a.m. ‘cause it just plain took 45 minutes to do the wind up—go to the bathroom, go to bed, even though it’s only 40 feet away. At 1:00 I’d say ‘It’s time to start getting ready to retire.’ [It’s] a ten minute job, but it took practically an hour every night.”

Altering expectations about how much needed to done and how often was a third theme. For example, “We had to walk her in the shower stall and boy we didn’t do that every night like we used to in the old days. Our theory was how the heck dirty can she get just sitting here all day or all week long? (laughs)” Caregivers also acted to alter the expectations of others in the social network about the elder’s behavior. For example, “I would tell people he’s not quite the same person that you remember. He needs a lot of naps. He goes to bed very early. He sleeps in a little bit and he takes a long nap. Do not push.”

Maintaining a Sense of Normalcy

This category involved creating images the elder wanted to project and supporting the elder to project that image. Reflecting remnants of normalcy was a major theme. This theme involved building caregiving activities upon what was left of normal activities, routines, and roles. Caregivers made sure, to the degree possible, everyday activities were done as they had always been. For example, “Until I put him in the hospital bed, I used to wheel him into the kitchen for a meal so he’d eat at the table. A lot of time I had to feed him, but I’d bring him in the kitchen and he’d sit at the table.”

The hospital bed posed a major dilemma for reflecting remnants of normalcy. Most elders strongly resisted moving to a hospital bed and caregivers supported their resistance until the last possible moment. “The hospital bed was a huge psychological step … . And he hated it because we did sleep together in a big queen size bed and he hated that I wasn’t there next to him. Even though I was sleeping on the floor next to him he hated that he couldn’t touch me.”

Caregivers reflected remnants of normalcy by inventing ways for the elder to appear as functional as possible. For example, “There was a time he went to the grocery store with me. I told him, ‘Let me get a wheel chair.’ ‘No, no. I’ll be all right.’ I’m thinking, ‘Oh my god.’ So we get in there and I’m like ‘Hold on to the carriage’.” Caregivers also reflected remnants of normalcy by supporting the elder’s role performance, making sure elders performed their usual family roles (Table 3, Example 1). They were also very careful to not “blow the elder’s cover.” For example, “He could fake it for a long time. He was a salesman, had an excellent personality. People liked him. He liked people. (sighs) People didn’t know for a while.” Caregivers even protected the elder’s cover with family members. For example, “The doctors wanted him on oxygen 24 hours a day. He would not put that thing in his nose when the kids and grandkids were here.”

Table 3.

Category II: Maintaining a Sense of Normalcy

| Example 1 | My car had broken down and he said, “Hon, I think you’re going to have to think about getting another car. Because now it’s just fix it, fix it, fix it.” So I said, “So what are we going to do?” He says, “Well, you go and pick one out and then bring it home and I’ll check it out for you.” So then my daughter came and stayed with him. I found the car and he had to drive it around the property. And I’ve said to the girls, “As sick as he was he was lucky not to hit something.” |

| Example 2 | We’d go out to a fancy restaurant and they [friends] would drag his wheel chair and his oxygen. We’d drink wine and laugh and carry on and tell stories. They knew he was not going to make it. We all knew that. I mean you couldn’t miss it. |

| Example 3 | Toward the end, the last six months, he had very, very vivid dreams. He’d wake up really upset by something he had to do. When he woke up he’d realize that he couldn’t do it. I finally realized it was reoccurring and got to the point when I would see he was beginning to wake up and I’d say, “Did you have some interesting dream last night?” Then he would go, “Oh, that probably was a dream.” It seemed to cut the agitation. |

Maintaining the façade, which involved projecting a positive image while minimizing or hiding negative aspects of EOL, was a second major theme. One-way caregivers maintained the façade was by ignoring the obvious. For example, “He did have some [breathing and memory problems] that he covered and that I ignored.” Caregivers also colluded with others to ignore the obvious as is demonstrated in Table 3, Example 2. When ignoring the obvious was no longer possible, caregivers switched to other strategies such as trivializing the elder’s deficits, sometimes by making jokes. For example, “At the end when he put on pants and he put two legs in one leg hole, I’d look at him and say, ‘Oh, you want to hop to the pool today?’ We’d laugh. I never made a big deal about anything.” Sometimes caregivers maintained the façade by normalizing the elder’s symptoms (Table 3, Example 3).

Quietly taking over was another way caregivers maintained the façade. Caregivers described quietly taking over many aspects of elders’ lives. For example, “I drove. I never really said ‘I don’t want you driving anymore.’ We’d go out to the garage and I’d get in the driver’s seat.” They also assured the quality of the care by quietly taking over. For example, “They had somebody come in to bathe him. He fell in the shower. I said to the girl, she was so young, ‘I know you mean well but I think I’m going to take over. I don’t need any help’.”

Quietly taking over could extend to manipulating the elder. For example, [He taught wine tasting classes and] “he went in a wheel chair and he was frustrated by the fact that he couldn’t do what he needed to do to teach it. I said to my husband, ‘let’s just quit, I mean we’ve done this long enough’.” It could also extend to manipulating the situation. In the following example, the elder was still working as a psychologist. “I noticed that he wasn’t fast with the information. I would say things like, ‘Maybe you need to retire dadada.’ I didn’t really push it. I just tried to make sure that [no appointments] came through.”

Minimizing Suffering

The most obvious way caregivers minimized suffering was through symptom management. Caregivers told many stories about how they attended to pain and manipulated medications to reduce undesirable side effects, sometimes against the advice of health care professionals. However, symptom management was a small part of the many ways caregivers minimized suffering.

An overriding theme was protecting the elder’s dignity and preventing suffering from humiliation. A spouse told the following story. “He wet the bed. I didn’t want him to know about it. He had said ‘Please don’t let me lose my self-respect, that’s all I’m asking you.’ I took him into the bathroom and I sat him down. And I said, ‘Dad, I’ll just go and straighten your bed’.”

Without exception, every caregiver provided examples of minimizing the elder’s suffering by being present. For example, “I didn’t want him to feel that he was being abandoned. That was what he was afraid of.” Being present greatly affected the quality of the caregiver’s life, as one caregiver explained, “It was five years that I had not been out of the city.” If the caregiver couldn’t be present, he or she was accessible (Table 4, Example 1). Almost all caregivers described minimizing suffering by being present at the elder’s death. For example, “My mother was just in bed. I just sat and held her hand and talked to her. Once I knew she wasn’t hearing me, I stayed there around the clock. I slept with my hand into her bed, holding her.”

Table 4.

Minimizing Suffering

| Example 1 | I bought one of those automatic dialers. Her favorite color was blue like her dress. I put a nice [blue] piece of yarn on it and I used to hang it around her. When it first started out I said, “Just push the button.” Well, she couldn’t remember which button so I took a little nail polish and covered the button for her to push and it would call my cell phone. So I kept all of my jobs within ten minutes of here. Then I’d come home. |

| Example 2 | When I went back about 5 pm and they moved him up into that ward that they redid for the children. He was in the Lion King room. He was not feeling too well. I went in to see him and said, “What did you have to eat today, for breakfast, lunch and dinner?” He said, “I didn’t have any.” I said, “You didn’t eat?” He said, “No, they didn’t bring it.” I said to the nurse, “Um, excuse me. He never got any meals today.” She looked at me and said, “I don’t run the kitchen.” |

Confronting the incompetence, insensitivity, and indifference of health care providers was another theme. Unfortunately, the need to confront health care providers was frequent and many caregivers told poignant stories about negative interactions with care providers (Table 4, Example 2). Some stories related to incompetence, but more commonly, they were about insensitivity and indifference and seemed rooted in ageist biases against providing more than minimal care to dying older people. Caregivers were fiercely protective of the elder in these situations because the incidents were viewed as imposing unnecessary suffering as well as assaulting the elder’s dignity.

A very striking theme related to giving permission, which occurred around the time of the elder’s death. All but two caregivers spontaneously told giving “permission stories” in describing their role. For example, “I would tell him ‘You’ve been everything to me. You don’t need to do this anymore. Its okay, you can go’.”

Gift Giving

The exchange of gifts between elders and caregivers was the final category identified. Caregivers indicated gift giving occurred daily and gifts honored the elder and the relationship. For example, “I considered it [the caregiving] a long goodbye. I knew I was saying goodbye. I still do.” One theme in gift giving was making personal sacrifices. Caregivers made personal sacrifices by taking on additional worry in risking the elder’s physical well-being to enhance the elder’s emotional well-being as is illustrated in this story. “The nurse wanted him to go on oxygen. He refused. He couldn’t bend over. He would get violently dizzy if he bent over. He used to always clean the pond. He would scoop out whatever is in there. I thought, ‘Oh god! He’s gonna fall in’.” Caregivers also made personal sacrifices by maintaining a façade of humor despite how they felt. For example, “I was running a circus. I would do things to amuse him and tell him stories and try to keep the cheerleading going. Then when he was asleep I’d sit and play computer games with the tears running down my cheeks.” Some personal sacrifices were made to reduce suffering. For example, “I think the worst part in the beginning, he had the esophagus cancer, he would try to eat. And at that point he was living on Ensure. I wouldn’t cook big meals because I didn’t want him to smell that. So I just had light meals.”

A second theme in gift giving was making life “as good as it could get.” For example, “He liked birds and the house had a beautiful back yard and a view and he fed the birds all the time. We had a big picture window and where his favorite chair was I put all these bird feeders. We had tons of birds, tons of beautiful birds, hummingbirds and everything. Every day I had to go out there and fill them up and hose it down.” Creating an atmosphere of “fun” was mentioned by many caregivers (Table 5, Example 1). Even caregiving activities were made to be fun (Table 5, Example 2).

Table 5.

Gift Giving

| Example 1 | I would get into mom’s place. I would get there, because you had to be in the moment, for yourself, for her. Whimsy, you could be whimsical … I would bring coloring books and we would listen to music. We would get up and dance. A hula hoop, we played with a hula hoop. We would throw horseshoes. We could be kids together. It was like playing with mom when I was a kid. |

| Example 2 | My two daughters, you know trying to change his bed linens. One would be up on bed, and they would be bouncing back and forth to turn him. And he’d even lay there and he’d say, “Hon, look at these two nuts. They’ll never change. Look at these two.” He had a wonderful sense of humor right to the end. |

Planning special events was a third theme. For example, one elderly husband had an anniversary party in the hospital just before his wife died. “We talked about the fact that we had a good life for 82 years. We were married 55 years last September. I brought cupcakes and a bow. We thought 55 years was quite an achievement.” Wives and children planned birthday parties and other events or trips designed to allow the elder to say goodbye. These events were especially important because they allowed for picture taking and for the collection of mementos, tangible reminders for the future.

A fourth theme was arranging life to allow for the affirmation of family ties. For example, this story was also told by a daughter caring for two dying parents. “Here she is in a wheel chair and daddy’s conscious but not really aware of what’s going on. She’s holding his hand. She couldn’t even move this side of her body. She’s holding his hand and she writes, ‘I want to kiss his face.’ So my husband, my sister’s husband, and my brother lift her up out of the wheel chair over this guy and she gets to kiss him. It was very touching and huge.”

The final theme was accepting gifts from elders. Some gifts from elders were in the form of personal affirmations. For example, “The following day I went in there and we talked off and on. She always called me her doll. Whenever we talked on the phone she’d always say ‘Goodbye doll.’ The last thing she said to me was ‘You look just like a doll.’ She never spoke to me again. But it was a beautiful thing to have (crying).” Other gifts from elders involved passing on the tradition or confirming a sense of continuity. For example, “That’s the most positive thing in the last year. She always told stories. You got to the point where you just roll your eyes and go, ‘Oh yeah, here she goes again.’ … But you know, that’s what makes a family, having those threads of continuity. I’m glad my own children got to know her. They didn’t get to know my grandparents.”

Discussion

We developed the term “generative caregiving” to describe the EOL caregiving role derived from the data based on our belief that generativity, a concept from the lifespan development literature, is central. In the lifespan development literature, generativity is defined as involving both nurturing others and contributing to society and the next generation through creative acts (Huta & Zuroff, 2007). Generativity occurs at a time in human development when there is an intensified temporal awareness of personal mortality. Both of these fit the EOL caregiving role described by these caregivers.

Generative caregiving is situated in the present with a goal to enhance the elder’s present quality of life, but also draws from the past and projects into the future with a goal to create a legacy that honors the elder and the elder–caregiver relationship. In the present, it is about drawing from the past and giving to the elder affirmations about his or her value and worth and transmitting to and receiving from the elder affirmations about the value of the elder–caregiver relationship. For the future, it is about the caregiver constructing daily living in ways that make it possible for the elder and caregiver to cocreate memories that extend the relationship beyond the death for the caregiver. In the words of a caregiver, it is about creating a future where, even after the death:

They are always at the table (crying) … . They’re always there with us like silent partners. We don’t pretend they didn’t exist. They’ve not left our family. We tell the stories; we are the remembering people. We tell the stories and we laugh and we get the pictures out. You never stop telling the stories; otherwise they are really dead.

Generative caregiving has both existential and transcendent qualities. At one level, generative caregiving is very terrestrial, reaching down into the depths of the present, everyday life. As in other forms of caregiving, it involves orchestrating the elder’s day-to-day life. For example, these EOL caregivers assumed responsibilities for myriad activities of daily living such as meal preparation, bathing or showering, and toileting. They assumed major responsibilities for tasks designed to ameliorate the elders’ health problems including symptom management, medication management, and managing emergencies. Caregivers also attended to the elder’s psychosocial needs by arranging elders’ social relationships, offering entertainment, and providing opportunities for spiritual expression. They also monitored the interactions between the elder and health professionals and advocated for better care. Some of these activities were extremely difficult, complex, and taxing and tended to become more so the closer the elder was to death. They were rooted in the realities of providing care for an adult whose self-care capacities were disappearing—sights and smells coupled with feelings of exhaustion, frustration, and inadequacy.

At another level, however, generative caregiving is transcendent, having an almost sacred quality. Although rooted in everyday life, the performance of everyday tasks reaches out beyond the presentness of the situation in ways that transcend the everyday reality and construct a new reality for the future. Although fixed in the present with a goal to enhance the elder’s quality of life, generative caregiving also honors the past and projects into the future with a goal to create a legacy. It is about creating a future bond with the elder that provides continuity and sweet memories “almost like he was there, too.”

Generative caregiving involves nurturing through creative acts that can transform the ordinary into something sacred or extraordinary. These caregivers displayed creativity through a range of activities that altered reality (e.g., slowing down time, altering expectations, planning special events) or transformed the elder (e.g., enhancing the elder’s self-image, maintaining a façade, managing symptoms, protecting the elder’s dignity). Caregivers were also creative in managing a wide spectrum of emotions, from those oriented toward minimizing suffering to those dealing with the joys of exchanging gifts.

Generative caregiving also involves a temporal awareness of EOL that can inspire unique motivations if not behaviors (Lawton, 2002) among EOL caregivers that may not exist in caregiving for those with long-term or chronic illnesses. Temporal awareness may, in fact, be the key element that distinguishes generative caregiving from other kinds of caregiving. All four categories reflected strong awareness of the temporalities of caregiving and the caregivers’ stories demonstrated temporal awareness with statements such as “I knew this would probably be the last … ” or “there would be no ‘do overs’.” Thus, caregiving activities were done with an immediacy of purpose—to reduce pain or to be grateful for a fleeting moment, and also to create moments of shared joy. Time and tasks were slowed down, expectations were altered and considerable energy went into creating positive memories for the future. Appreciation for the past, while focusing on the present and dwelling in the moment were strategies purposely used by the caregiver to enhance the well-being of both caregiver and elder. The intensified awareness of mortality and EOL likely brought clarity of purpose to caregiving and a boldness in carrying out caregiver tasks to minimize suffering or relishing in gift giving.

Generative caregiving is distinct from other types of caregiving based on the shift in focus from “me and my problems” to a focus on “you” (the elder) and on “us” (the elder–caregiver relationship). Confrontation with one’s mortality through personal illness or through the intimate care of a terminally ill family member can initiate this self-transcendence (Reed, 2008). Generative caregiving involved enhancing quality of life; creating memories; and affirming the elder, the relationship and the future. As one caregiver stated, “I talked to the kids about it. And I said ‘Oh, we’re going to do a lot of crying but we got to live on our memories’.”

The creativity and temporal awareness that characterized caregiving in this study provide an explanatory framework for understanding some of the unique behaviors of EOL caregivers, particularly when the activities appear to be contrary to the elder’s “best interests.” Bowers (1987) explained that for caregiving in general, health professionals give highest priority to instrumental caregiving, whereas family caregivers tend to give priority to activities that protect elders from threats to self-image and assaults to personal dignity sometimes to the detriment of the elder’s physical well-being. The findings here support this idea: the EOL caregivers gave highest priority to activities that affirmed the elder and the elder caregiver relationship now and for the future such as taking a trip or having a party. Lower priority was given to more tangible problems, such as moving in a hospital bed, better pain control, or having oxygen.

Findings in this study are also supported by several studies of EOL caregiving. For example, Milberg and Strang (2004) used Antonovsky’s theory of Sense of Coherence (1987) as a guide for understanding the positive outcomes of EOL caregiving reported in the literature (e.g., Grbich et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2007). The investigators affirmed the existence of two major concepts from Antonovsky’s theory, comprehensibility (making meaning through a congruent inner reality) and manageability (personal connections), in qualitative interviews with EOL caregivers. To some degree, generative caregiving is all about creating meaning by performing everyday activities in ways that create a legacy for the future. Affirming and maintaining personal connections with the dying person and affirming family bonds were also essential aspects of generative caregiving.

Kwak et al. (2007) offered EOL caregivers an intervention focused on the “transformative aspects of caregiving.” Outcomes were caregivers’ comfort with care, sense of closure, and sense of gain. Results showed increases in all three areas. Of particular relevance to this study is that many of the transformative aspects of caregiving taught to caregivers in the intervention are similar to roles caregivers in this study constructed spontaneously. For example, the intervention included accepting the gift of wisdom and knowledge from the care recipient, telling “our” story as a way of affirming the meaning of the care recipient’s life, being present, and respect for the care recipient’s preferences.

The results of this study also point to areas of needed research regarding EOL caregiving. First, research is needed to better understand the points at which caregivers switch from an interpretation of the situation as “chronic” to “terminal.” All these caregivers showed generative caregiving, but not all the time and the amount was variable among caregivers. Even within caregiving situations, caregivers sometimes appeared to be providing chronic care (evidenced by stories focused on the caregiver and caregiving problems) and at other times EOL care (evidenced by stories focused on the elder and the “us”). These data suggest that temporal awareness may be key to understanding these shifts because stories phrased in the context of “the last time,” for example, were more likely to contain generative caregiving themes. Further research, however, is needed to refine these ideas.

Second, research is needed on the relationships of communication to discrepancies in temporal awareness between health professionals and caregivers. Health professionals tend to view EOL as having a very limited time frame, yet these caregivers had a starkly different interpretation that gave a sense of urgency and finality to their actions even years before the death. Some of the conflicts between caregivers and health professionals were rooted in this difference in interpretation. Research is needed to test strategies for reducing differences in interpretation as a way to improve communication between caregivers and health care providers.

Finally, research is needed on the relationships among caregiving, generativity, and well-being. The relationship between generativity and well-being in adulthood is a widely accepted theoretical idea of Erikson (1982) and has considerable empirical support from studies of adults in general (see Huta & Zuroff, 2007 for a review; Kotre, 1995). Generativity is not discussed in the literature on caregiving, although there are discussions of the positive aspects of caregiving that reflect generative behaviors (e.g., Kuuppelomaki, Sasaki, Yamada, Asakawa, & Shimanouchi, 2004; Roff et al., 2004). Caregivers in this study who expressed the most generative caregiving also expressed the most well-being after the death. One explanation for the relationship between generativity and well-being in EOL caregivers is that generativity provides a sense of symbolic immortality, a term that originated with the work of Lifton (1979), who explained that everyone in the face of death has a basic need for a sense of immortality. Findings indicated that caregivers and elders both benefited from the creativity and legacy activities—symbols of immortality—reported in this study. Research into the potential relationship between generative caregiving and caregiver well-being seems warranted. Continued attention to EOL caregiving in our research, theories, and practice will honor those who go before us. They are, as Kellor (2008) eloquently described in an editorial, like “a tall tree shading us from mortality.”

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NR008563).

References

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health—how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beeson R, Horton-Deutsch S, Farran C, Neundorfer M. Loneliness and depression in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21:7799–7806. doi: 10.1080/016128400750044279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ. Intergenerational caregiving: Adult caregivers and their aging parents. Grounded-theory method was used to generate a new theory. Advances in Nursing Science. 1987;9:20–31. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Collier JAH, Schirm V. Family focused nursing care of the hospitalized elderly. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1992;29:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(92)90060-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos AZ, Given B, Given CW, Wyatt G, Gift A, Rahbar M, et al. The influence of end-of-life cancer care on caregivers. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;20:270–281. doi: 10.1002/nur.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme F, Levesque L, Lachance L, Zarit S, Vezina J, Gangbe M, et al. Older husbands as caregivers of their wives: A descriptive study of the context and relational aspects of care. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43:567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. The lifecycle completed. New York: W.W. Norton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Exley C, Field D, Jones L, Stokes T. Palliative care in the community for cancer and end-stage cardiorespiratory disease: The views of patients, lay-carers and health care professionals. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;19:76–83. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm973oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BAS, Schumacher KL, Dodd M, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Lee K, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in family caregivers of patients undergoing radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:125–139. doi: 10.1002/nur.20312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, Given CW, Tolbert V, Kataria R, et al. Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: A multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psycho-oncology. 2004;14:771–785. doi: 10.1002/pon.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Adline; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grbich C, Parker C, Maddocks I. The emotions and coping strategies of caregivers of family members with terminal cancer. Journal of Palliative Care. 2001;17:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M, Hoyer DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2009;57(14):1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huta V, Zuroff DC. Examining mediators of the link between generativity and well-being. Journal of Adult Development. 2007;14:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kellor G. We don’t need old-timer dithering in White House. Arizona Daily Star. 2008, July 30:A9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Schulz R, Carver CS. Benefit finding in the cancer caregiving experience. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:283–291. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180417cf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotre J. Generative outcome. Journal of Aging Studies. 1995;9:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kozachik SL, Given CW, Given BA, Pierce SJ, Azzouz F, Rawl SM, et al. Improving depressive symptoms among caregivers of patients with cancer: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28:1149–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuuppelomaki M, Sasaki A, Yamada K, Asakawa N, Shimanouchi S. Family carers for older relatives; sources of satisfaction and related factors in Finland. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J, Salmon JR, Acquaviva KD, Brant K, Egan KA. Benefits of training family caregivers on the experiences of closure during end-of-life care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;33:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton J. Colonising the future: Temporal perceptions and health-relevant behaviours across the adult lifecourse. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2002;24:714–733. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Stewartk BJ, Imle MA, Archbold PG, Felver L. Families and hospitalized elders: A typology of family care actions. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:3–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200002)23:1<3::aid-nur2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton RJ. The broken connection: On death and the continuity of life. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older Medicare decedents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1108–1112. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas ML, Buckwalter KC, Kelley LS. Family members’ perceptions of care of institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Applied Nursing Research. 1991;4:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(05)80070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco CA, Buderer N, Thum D. End-of-life care: Perspectives of family members of deceased patients. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2005;22:26–31. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messecar DC, Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Kirschling J. Home environmental modification strategies used by caregivers of elders. Research in Nursing & Health. 2002;25:357–370. doi: 10.1002/nur.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberg A, Strang P. Exploring comprehensibility and manageability in palliative home care: An interview study of dying cancer patients’ informal carers. Psycho-oncology. 2004;12:605–618. doi: 10.1002/pon.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AS, Lyketsos C. End-of-life decisions with Alzheimer’s disease. Advanced Studies in Nursing. 2005;3:355–367. [Google Scholar]

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. October, 2008. Retrieved June 1,2009, from http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/NHPCO_facts-and-figures_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DL. Self-identifying as a caregiver: Exploring the positioning process. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault A, Fothergill-Bourbonnaism F, Fiset V. The experience of family members caring for a dying loved one. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2004;10:133–143. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.3.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redinbaugh EM, Baum A, Tarbell S, Arnold R. End-of-life caregiving: What helps family caregivers cope? Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6:901–909. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed PG. Theory of self-transcendence. In: Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Middle range theory for nursing. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Roff LL, Burgio LD, Gitlin L, Nichols L, Chaplin W, Hardin JM. Positive aspects of Alzheimer’s caregiving: The role of race. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B:185–190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problems of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher K, Beck CA, Marren JM. Family caregivers: Caring for older adults, working with their families. American Journal of Nursing. 2006;106(8):40–42. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200608000-00020. 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Beidler SM, Beeber AS, Gambino P. A transactional model of cancer family caregiving skill. Advances in Nursing Science. 2006;29:271–286. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG. Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nursing Research. 2007;56(6):425–433. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299852.75300.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, Caparro M, Mutale F, Agrawal S. Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2008;35:49–56. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SM, Schmidt LA. Telephone support for caregivers of patients with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26:448–453. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, Kasper JD. End-of-life care: Findings from a national survey of informal caregivers. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:40–46. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]