Abstract

Work from our laboratory and others has demonstrated that activation of the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) inhibits transformed growth of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines in vitro and in vivo. We have demonstrated that activation of PPARγ promotes epithelial differentiation of NSCLC by increasing expression of E-cadherin, as well as inhibiting expression of COX-2 and nuclear factor-κB. The Snail family of transcription factors, which includes Snail (Snail1), Slug (Snail2), and ZEB1, is an important regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, as well as cell survival. The goal of this study was to determine whether the biological responses to rosiglitazone, a member of the thiazolidinedione family of PPARγ activators, are mediated through the regulation of Snail family members. Our results indicate that, in two independent NSCLC cell lines, rosiglitazone specifically decreased expression of Snail, with no significant effect on either Slug or ZEB1. Suppression of Snail using short hairpin RNA silencing mimicked the effects of PPARγ activation, in inhibiting anchorage-independent growth, promoting acinar formation in three-dimensional culture, and inhibiting invasiveness. This was associated with the increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased expression of COX-2 and matrix metaloproteinases. Conversely, overexpression of Snail blocked the biological responses to rosiglitazone, increasing anchorage-independent growth, invasiveness, and promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The suppression of Snail expression by rosiglitazone seemed to be independent of GSK-3 signaling but was rather mediated through suppression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity. These findings suggest that selective regulation of Snail may be critical in mediating the antitumorigenic effects of PPARγ activators.

Introduction

A considerable amount of current literature suggests that loss of epithelial features and gain of mesenchymal properties play a critical role in the progression and metastasis of epithelial tumors [1]. These events are similar to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that has been well characterized in embryonic development. EMT involves complex cellular changes including loss of polarity and disruption of cell-cell contacts, synthesis of extracellular matrix molecules, as well as proteolytic enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) involved in matrix degradation that contribute to cell motility and invasiveness [2]. Loss of E-cadherin has been shown to be associated with increased tumor invasiveness, metastasis, and poor prognosis [3–5]. Transcriptional repression has emerged as a mechanism of silencing E-cadherin during tumor progression. This suppression is mediated by members of the Snail, ZEB, and basic-helix-loop-helix families of transcription factors. Snail1 (Snail) and Snail2 (Slug) belong to the Snail superfamily of zinc finger transcriptional repressors that participate in the developmental EMT [6]. Snail is required for mesoderm and neural crest formation during embryonic development and has been implicated in the EMT associated with tumor progression. Slug also represses E-cadherin and induces a complete EMT. However, Slug binds with lower affinity than Snail to the E-cadherin promoter [7].

Expression of Snail and/or Slug has been reported in breast, ovarian, colon, skin, and squamous cell carcinomas and is associated with poor prognosis [6,8]. Although the function of Snail and Slug can be interchangeable in different species [9], a distinct role for each factor is supported from analysis of knockout mice. Whereas Snail null mice present early embryonic lethality [10], Slug null mice are viable, undergoing a normal program of development [11]. The specific contribution of Snail and Slug to tumor progression is still poorly defined. Snail is activated at the invasive front of tumors induced in mouse skin [12] and has been associated with breast and hepatocarcinoma invasion [13,14]. Snail induces a full EMT when overexpressed in epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney cells leading to acquisition of a motile/invasive phenotype [12,15]. Recently, these transcription repressors have also been found to be expressed in lung adenocarcinomas. Knockdown of Snail, through RNA interference, increases the sensitivity of non- small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells to chemotherapeutic agents [16]. Prostaglandin E2 has been shown to induce ZEB-1 and Snail in NSCLC [17]. Slug expression is a predictor of outcome in lung adenocarcinoma patients [18]. Overexpression of ZEB-1 has been implicated in mediating EMT in NSCLC cells [19].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. In addition to its known role in adipocyte differentiation, PPARγ has been implicated in regulating carcinogenesis [20]. PPARγ activators of the thiazolidinedione class (TZDs), such as rosiglitazone and troglitazone, slow growth of colon and thyroid tumors [21,22]. In NSCLC, activation of PPARγ can inhibit growth of NSCLC cells in vitro and in xenograft models [23–25]. We have shown that mice with targeted overexpression of PPARγ in the distal epithelia of the lung are protected against developing lung tumors in a chemical carcinogenesis model [26].

Mechanistically, several studies have demonstrated that PPARγ activation can inhibit nuclear factor-κB and COX-2 expression in NSCLC [26,27]. PPARγ has been shown to increase E-cadherin expression, suggesting that it may target transcriptional repressors; however, the effects of PPARγ on Snail family members have not been well studied. Here, we report that PPARγ-mediated inhibition of Snail expression represents a critical pathway in mediating the antitumorigenic effects of TZDs on NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies against Snail, Slug, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), phospho (p)-ERKs, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); antibody against E-cadherin was from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ); and COX-2 antibody was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). β-Actin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Rosiglitazone was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). PD98059 and GSK-3β inhibitors were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Culture and Stable Transfections

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, H2009 and H2122, were obtained from the University of Colorado Health Science Center Tissue Culture Core. The Snail complementary DNA (cDNA) was used to stably transfect NSCLC by retroviral-mediated gene transfer as previously described [28]. Pools of stable transfectants were screened for the expression of Snail by immunoblot analysis. Snail and control short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids obtained from Open Biosystems (Rockford, IL) were used to transfect NSCLC using ExGen500 transfection reagent (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD).

Migration/Invasion, Soft Agar Colony Formation, and Three-dimensional Culture

Migration and invasion were determined as previously described [23]. Colony formation in soft agar was performed as described previously [28]. Colonies formed in 3- to 4-week period were stained with nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (1 mg/ml), visualized under a microscope and counted. For three-dimensional cultures, cells were grown in Matrigel using a modification of the procedure of Debnath et al. [29], as previously described [23]. Briefly, cells were plated at 5000 per well in 10% Matrigel in full media and were fed with 4% every other day for a term of 8 to 10 days of culture.

Confocal Microscopy and Image Analysis

Cells grown in two-dimensional or three-dimensional cultures were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes if needed. All samples were blocked with 1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated with E-cadherin antibody (1:100; BD Biosciences) for three-dimensional cultures or anti-Snail antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for two-dimensional cultures, overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 hour of incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 568 rabbit antigoat immunoglobulin G, 1:250; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were mounted and viewed with TE2000-S IF microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) or a 510 Meta/FCS laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Confocal images were processed using LSM Image Examiner.

SYBR Green Real-time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized using iSCRIPT cDNA synthesis kit from BioRad (BioRad, Hercules, CA). For real-time PCR, relative gene expression was determined by SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) on a Bio-Rad iCycler (BioRad). Primer pairs and PCR conditions are as follows: SnailF, 5′-CGCGCTCTTTCCTCGTCAG-3′; SnailR 5′-TCCCAGATGAGCATTGGCAG-3′; SlugF, 5′-GCCTCCAAAAAGCCAAACTA-3′; SlugR, 5′-CACAGTGATGGGGCTGATG-3′; ZEB1F, 5′-AGGAGTGAAAGAGAAGGGAATGC-3′; ZEB1R, 5′-GGTCCTCTTCAGGTGCCTCAG3′; β-ActinF, 5′-AGGGTGTGATGGTGGGTATGG-3′; β-ActinR, 5′-AATGCCGTGTTCAATGGGG-3′, 55 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 30 seconds; MMP-9F, 5′-CCACTTCCCCTTCATCTTC-3′; MMP-9R, 5′-CGTCCTGGGTGTAGAGTC-3′; 55 cycles at 95°C for 20 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds; MMP-2F, 5′-TCTTGACCAGAATACCATCG-3′; MMP-2R, 5′-CACATCGCTCCAGACTTG-3′; 55 cycles at 95°C for 20 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. The relative gene expression, normalized to β-actin and based on three separate experiments, was calculated.

Matrix Metalloproteinase—Zymography

Semiconfluent cultures of cells (∼80% confluent) were placed in serum-free medium, treated with or without rosiglitazone, and cultured for an additional 36 hours. Conditioned medium was concentrated (Microcon YM-10 centrifugal filter; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and separated on 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% (wt./vol.) gelatin under nonreducing conditions. Zymography for MMP-9 and MMP-2 was performed according to Bernhard and Muschel [30].

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by analyzing the data using one-way analysis of variance (GraphPad InStat 3 Software). P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PPARγ Selectively Inhibits Expression of Snail in NSCLC

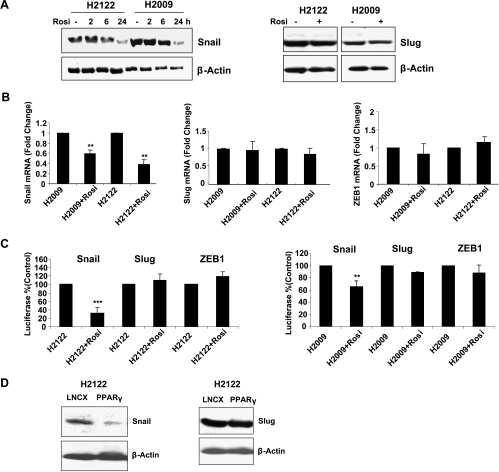

To begin to define the molecular mechanisms whereby PPARγ can control EMT in NSCLC, we examined the effects of the PPARγ activator rosiglitazone on transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin: Snail, Slug, and ZEB1 in two lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, H2009 and H2122. Stimulation with rosiglitazone (10 µM) decreased the expression of Snail in a time-dependent manner. Expression was significantly decreased at 6 hours; by 24 hours, the expression was inhibited in both cell lines by approximately 75% (Figure 1A, left panel). No significant changes were observed in expression of Slug (Figure 1A, right panel). Levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) for Snail, Slug, and ZEB1 were assessed by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Rosiglitazone significantly decreased Snail mRNA levels in both cell lines; no significant effect was observed on expression of either ZEB1 or Slug (Figure 1B). These findings were further confirmed by reporter assays, wherein cells were transiently transfected with Snail, Slug, and ZEB1 promoter constructs driving a luciferase reporter. Rosiglitazone inhibited Snail promoter activity in both cell lines (Figure 1C) but had no effect on either Slug or ZEB promoter activity. To confirm if the effects on Snail expression were PPARγ specific, we also examined Snail expression in H2122 cells overexpressing PPARγ. Expression was markedly decreased in these cells compared with controls transfected with empty vector (Figure 1D). No change in Slug expression was observed (Figure 1D). Finally, a pharmacological inhibitor of PPARγ, T0070907 (T007) [31], was able to reverse the decrease in Snail mRNA induced by rosiglitazone (Figure W1).

Figure 1.

Rosiglitazone selectively decreases expression of Snail in NSCLC. (A) Left panel: H2122 or H2009 cells treated with rosiglitazone or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for the indicated times were immunoblotted for Snail expression. Levels of β-actin were used as a loading control. Right panel: Nuclear extracts from cells treated for 24 hours with rosiglitazone were immunoblotted for Slug. (B) RNA was isolated from cells stimulated for 24 hours with rosiglitazone or vehicle (0.1% DMSO), and the expression of Snail (left panel), Slug (middle panel), or ZEB1 (right panel) was determined by real-time PCR. (C) Cells were transiently transfected with constructs encoding either the Snail promoter, the Slug promoter, or the ZEB1 promoter, ligated to a luciferase reporter, along with a plasmid encoding β-gal under the control of CMV promoter to normalize for transfection efficiency. Cells were stimulated with rosiglitazone for 24 hours, and luciferase activity normalized to β-gal activity was determined. Results are presented as percent of control for each promoter. **P < .01 versus controls, ***P < .001 versus controls. All data represent the means of three independent experiments. (D) H2122 cells overexpressing PPARγ (H2122-PPARγ) or empty vector (H2122-LNCX) were grown under standard conditions. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and immunoblotted for Snail (left panel) or Slug (right panel) expression. Levels of β-actin were used as a loading control. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Snail Silencing Mimics Effects of PPARγ Activation on Downstream Effectors

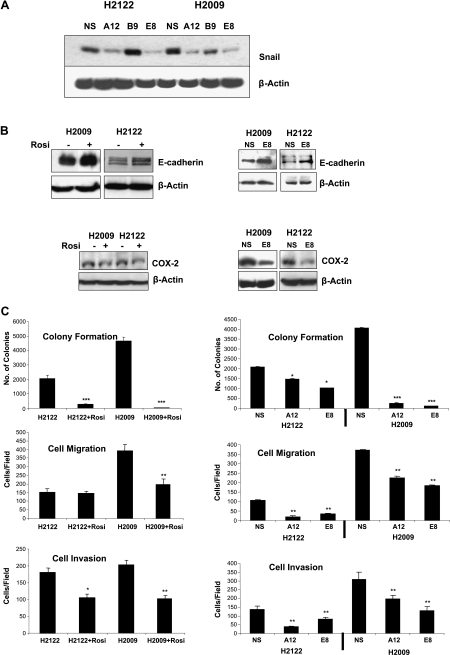

To assess the role that decreased expression of Snail plays in mediating the effects of PPARγ, we silenced Snail in both adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cells were transfected with lentiviral vectors encoding shRNA against Snail or with nonsilencing control shRNA (NS). Pools of cells transfected with two independent Snail shRNA constructs (A12 and E8) showed decreased expression of Snail protein compared with NS controls in both cell lines (Figure 2A). A third shRNA construct (B9) did not significantly decrease Snail expression in either cell line. In addition, Snail promoter activity was also decreased in the silenced cells compared with NS controls (data not shown). We have previously reported that overexpression of PPARγ increases E-cadherin levels in NSCLC [23]. Here, we examined the effects of rosiglitazone on E-cadherin expression. As shown in Figure 2B (top panels, left)), rosiglitazone increased E-cadherin expression in both H2122 and H2009. Silencing of Snail expression also resulted in increased E-cadherin expression (Figure 2B, top panels, right). In both H2122 and H2009, rosiglitazone decreased COX-2 expression, and this was also observed in the cells silenced for Snail expression (Figure 2B, bottom panels).

Figure 2.

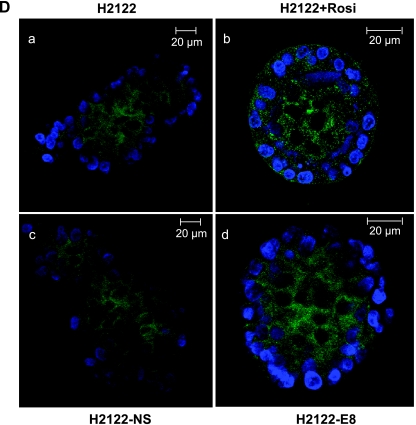

Silencing Snail expression recapitulates the responses to Rosiglitazone. (A) The indicated cell lines were stably transfected with three distinct shRNA constructs against Snail, as well as a nonsilencing control construct (NS), and immunoblotted for Snail. Two of the constructs (A12 and E8) effectively decreased the expression of Snail and were used in further experiments. (B) Left panels: NSCLCs were stimulated for 24 hours with 10 µM rosiglitazone and immunoblotted for E-cadherin (top) or COX-2 (bottom). Right panel: Cells silenced for the expression of Snail (E8), or nonsilencing control cells (NS) were immunoblotted for E-cadherin expression (top) or COX-2 (bottom). (C) Left panel, top: NSCLCs were plated in soft agar (0.3%), with or without rosiglitazone (10 µM), and the resulting colonies were counted after 3 to 4 weeks. Right panel, top: Pooled cells silenced for Snail, or nonsilencing control cells were plated in soft agar and the resulting colonies were counted. ***P < .001 versus controls or nonsilencing controls, *P < .05 versus nonsilencing controls. Migration of NSCLC was assayed in Transwell chambers. Parental cells, with or without rosiglitazone (10 µM) treatment, or cells silenced for the expression of Snail (A12 and E8), or nonsilencing control cells (NS) (middle panels), were placed 0.1% FBS with 5% FBS in the bottom chamber. After 24 hours, migrating cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2 phenylindole. **P < .01 versus controls or nonsilencing controls. Invasion was measured using Transwell chambers coated with Matrigel (bottom panels). Cells were plated as previously mentioned and counted at 72 hours. *P < .05 versus controls, **P < .01 versus controls or nonsilencing controls. (D) Untransfected H2122 cells and H2122-NS and H2122-E8 cells were grown in three-dimensional Matrigel culture as described in Materials and Methods for 8 to 10 days. H2122 cells were treated with rosiglitazone (10 µM). Cells were fixed and stained for E-cadherin expression (green) or 4′,6-diamidino-2 phenylindole (blue). Representative acinar structures are shown. H2122 cells treated with rosiglitazone (b) formed regular acinar structures compared with controls (a). Similarly, Snail-silenced cells (d) were characterized by a highly differentiated morphology compared with nonsilencing control cells (c).

Silencing Snail Mimics Biological Responses to Rosiglitazone

Consistent with the work of other investigators [25], exposure to rosiglitazone inhibited soft agar colony formation, a measure of transformed growth in both NSCLC cell lines (Figure 2C, left panel, top). Importantly, silencing Snail using two independent shRNA constructs (A12 and E8), also resulted in a marked decrease in colony formation (Figure 2C, right panel, top). Rosiglitazone decreased invasion of H2122 cells and inhibited both migration and invasion of H2009 cells (Figure 2C). Silencing Snail expression similarly decreased migration (Figure 2C, right panel, middle) and invasion (Figure 2C, right panel, bottom) in both cell lines compared with NS cells. Finally, we examined the growth of NSCLC in three-dimensional Matrigel cultures. Our previous studies demonstrated that H2122 cells form loose disorganized aggregates in three-dimensional culture (Figure 2D, panel a) and that overexpression of PPARγ promotes formation of regular acinar-like structures [23]. Treatment of NSCLC with rosiglitazone also led to the formation of organized structures (Figure 2D, panel b). Cells silenced for Snail expression also formed ordered structures that were indistinguishable from those observed with rosiglitazone (Figure 2D, panel d), whereas NS controls formed structures analogous to wild-type cells (Figure 2D, panel c).

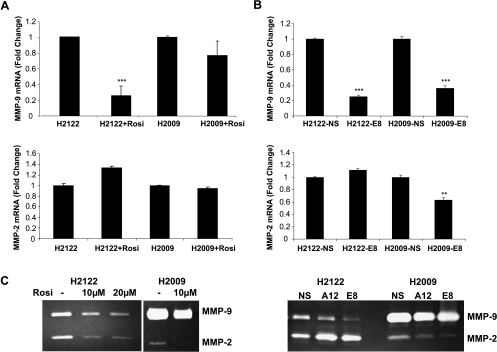

Because MMPs are important in promoting invasion through the extracellular matrix and are involved in tumor invasion and progression [32], we determined whether the decreased migratory and invasive properties of cells in response to PPARγ activation or silencing of Snail were associated with changes in the activity or expression of MMPs. As shown in Figure 3A (top panel), rosiglitazone markedly decreased the mRNA expression of MMP-9 in H2122 cells and modestly decreased the expression in H2009 cells. No significant effects were seen on MMP-2 expression (Figure 3A, bottom panel). By zymography, exposure to rosiglitazone was associated with a marked decrease in the activity of both MMP-9 and MMP-2 in both cell lines (Figure 3C, left panel), indicating that PPARγ activation of MMPs involves additional posttranscriptional mechanisms. Silencing of Snail had similar effects in both cell lines. Levels of MMP-9 were decreased in both cell lines (Figure 3B, top panel), with minimal effects on MMP-2 mRNA (Figure 3B, bottom panel) compared with NS controls. Zymography indicated that silencing Snail selectively decreased MMP-9 in H2122 cells while modestly decreasing both MMP-9 and MMP-2 in H2009 cells (Figure 3C, right panel).

Figure 3.

PPARγ or Snail silencing inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases. (A) NSCLCs were treated with rosiglitazone (10 µM) or vehicle (control) for 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated, and the expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 mRNA normalized to β-actin was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. ***P < .001 versus controls. (B) Total RNA was extracted from Snail-silenced cells (E8) as well as nonsilencing control cells (NS). mRNA expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 was analyzed as described previously. ***P < .001 versus nonsilencing controls, **P < .01 versus nonsilencing controls. (C) Medium collected from NSCLC treated with or without rosiglitazone (left panel) or Snail-silenced cells (E8) and nonsilencing control cells (NS) (right panel) was assessed for MMP-9 and MMP-2 activity as described in Materials and Methods.

Snail Overexpression Blocks Biological Responses to Rosiglitazone

To complement the studies silencing expression Snail in NSCLC, we stably overexpressed the protein in the two NSCLC cell lines. Multiple clones of stably transfected cells were selected by immunoblot analysis. As shown in Figure 4A, cells transfectants showed an increase in Snail protein expression compared with empty vector controls, and expression was largely localized to the nucleus (Figure 4B). As expected, Snail-overexpressing cells had lower levels of E-cadherin protein (Figure 4C) and decreased E-cadherin promoter activity (data not shown). Rosiglitazone reduced Snail expression in the empty vector controls but had no effect on Snail expression in the overexpressing cell lines.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of Snail inhibits the effects of rosiglitazone. (A) Snail-overexpressing clones (S9 for H2122 and S1 for H2009) and empty vector controls (L4 and L2) were treated with or without rosiglitazone (10 µM) for 24 hours, and Snail expression was determined by immunoblot analysis. (B) Transfected cells were immunostained with anti-Snail antibody. (C) Lysates from the indicted cell lines were immunoblotted for E-cadherin. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

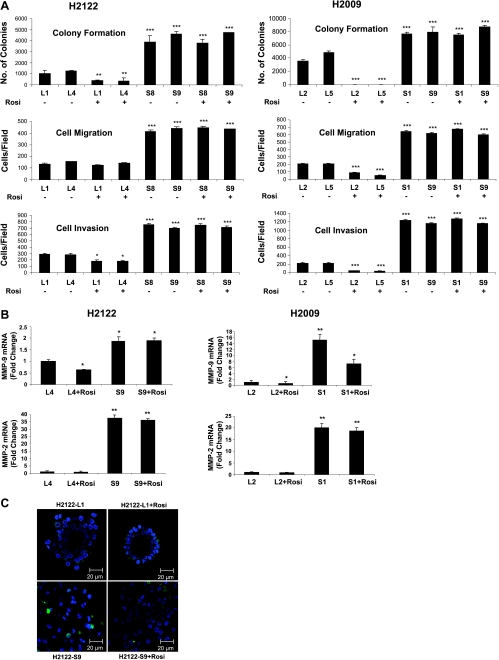

In two independent clones of H2122 cells, Snail-overexpressing cells showed a marked increase in colony formation in soft agar compared with empty vector control (Figure 5A, top). In H2009, there was a more modest but still statistically significant increase (Figure 5A, top right). Importantly, whereas rosiglitazone decreased colony formation in empty vector cells, it had no effect on the colony number in Snail overexpressing cells. In both cell lines, overexpression of Snail increased both migration and invasiveness (Figure 5A, middle and lower panels). Whereas rosiglitazone decreased migration and invasiveness in H2009 cells, and selectively inhibited invasion of H2122 cells, similar to what is observed in parental untransfected cells, it had no effect in either cell line overexpressing Snail. Overexpression of Snail also increased expression of both MMP-9 and MMP-2, and rosiglitazone did not alter expression (Figure 5B). Finally, we examined the growth of Snailoverexpressing cells in three-dimensional Matrigel cultures using H2122 cells. Cells transfected with empty vector (L1) formed irregular clusters of cells similar to those seen in untransfected cells (Figure 5C, upper left), and rosiglitazone promoted formation of regular acinar structure (Figure 5C, upper right). In contrast, overexpression of Snail promoted more scattered structures and seemed to decrease cell aggregation (Figure 5C, lower left). Rosiglitazone, in the setting of Snail overexpression, failed to alter the structures and did not result in formation of regular acini (Figure 5C, lower right).

Figure 5.

Snail overexpression blocks the biological responses to Rosiglitazone. (A) Colony formation in soft agar (top panels), cell migration (middle panels), or invasion (bottom panels) was determined for the indicated cell lines transfected with empty vector (L1 and L4 for H2122 and L2 and L5 for H2009) or individual clones overexpressing Snail (S8 and S9 for H2122 and S1 and S9 for H2009) treated with rosiglitazone (10 µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). **P < .01 versus empty vector controls, ***P < .001 versus empty vector controls; *P < .05 versus empty vector controls. (B) MMP-9 and MMP-2 mRNA was quantified in the indicated cells by quantitative RT-PCR. *P < .05 versus empty vector controls, **P < .01 versus empty vector controls. (C) The indicated cells were grown for 7 days in three-dimensional Matrigel culture in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone (10 µM). After 7 days in culture, structures were fixed and stained for E-cadherin (green). Representative acinar structures are shown.

Effects of Rosiglitazone on Snail Are Mediated through Suppression of ERK Activity

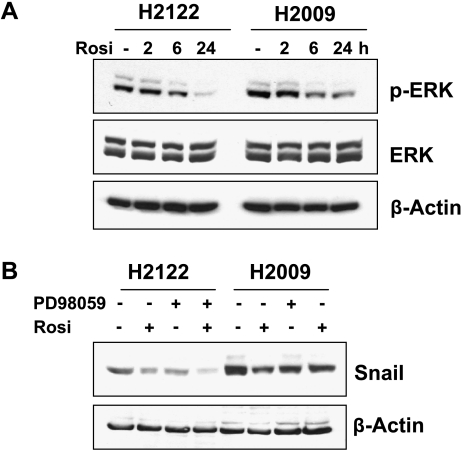

Whereas PPARγ activation can impact numerous signaling pathways, a recent study demonstrated that troglitazone, another TZD mediates induction of E-cadherin through the inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK signaling in pancreatic cancer cells [33]. We therefore examined the effects of rosiglitazone on ERK activation in H2122 and H2009 cells. Rosiglitazone decreased phospho-ERK expression in a time-dependent fashion, with maximal decreases observed after 24 hours (Figure 6A). There was no significant change in total ERK expression. To determine whether this decrease in ERK mediated the decrease in Snail expression, cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059, in the absence or presence of rosiglitazone. After 24 hours of treatment, PD98059 and rosiglitazone both decreased the expression of Snail in the two lung cancer cell lines to the same extent (Figure 6B); combinations of rosiglitazone and PD98059 did not result in greater inhibition than either agent alone. Several studies have reported regulation of Snail expression by GSK-3β, which is regulated through Wnt signaling [34,35]. However, this pathway does not seem to play a major role in the regulation of Snail by rosiglitazone because levels of phospho-GSK-3β were not altered in response to rosiglitazone (Figure W2A), and a GSK-3β inhibitor had no effect on the ability of rosiglitazone to suppress Snail expression (Figure W2B).

Figure 6.

PPARγ effects on Snail expression are mediated by suppressing ERK phosphorylation. (A) NSCLC were grown in the presence of absence of rosiglitazone (10 µM) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for ERK and phospho-ERK. β-Actin was used as loading control. (B) Cells were treated with PD98059 (20 µM) or rosiglitazone (10 µM), either alone or in combination, along with appropriate controls (0.1% DMSO). Nuclear extracts were immunoblotted for Snail. Levels of β-actin were used as a loading control. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

NSCLC, the most common cancer in the United States, is associated with a poor prognosis, indicating that novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed. TZDs exhibit in vitro and in vivo antitumor effects against many types of cancers, including lung cancer [36,37]. Analysis of human lung tumors has reported that decreased expression of PPARγ is correlated with a poor prognosis [38], and expression of PPARγ as detected by immunohistochemistry was more frequently detected in well-differentiated adenocarcinomas compared with poorly differentiated ones. Recently, a retrospective study demonstrated a 33% reduction in lung cancer risk in patients with diabetes using the TZD rosiglitazone [39]. This decreased risk seemed to be specific for lung cancer because no protective effect was observed for prostate or colon cancer. Genetic variants in the PPARγ gene, which are associated with a decreased risk for lung cancer, have been identified [40]. These studies strongly suggest the potential for TZDs as chemopreventive or chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of lung cancer.

Previous work form our laboratory has demonstrated that activation of PPARγ in NSCLC inhibits transformed growth, promotes differentiation, and inhibits invasiveness [23,26,28].However, the molecular targets of PPARγ mediating these responses are not well defined. In this study, we hypothesized that inhibitory effects of PPARγ on transformed growth might be mediated by the down-regulation of Snail family members. Activation of PPARγ by rosiglitazone in two NSCLC cell lines decreased expression of Snail but did not significantly alter expression of either Slug or ZEB1. Regulation of Snail expression seems to be a critical event in mediating the effects of PPARγ on these cancer cells. Cells with silenced expression of Snail recapitulated many of the biological responses seen with rosiglitazone stimulation: inhibition of anchorage-independent growth, inhibition of invasiveness, and promotion of organized, more differentiated structures in three-dimensional culture. Conversely, overexpression of Snail was sufficient to block the action of rosiglitazone on all of these responses.

Snail suppression increased levels of E-cadherin and decreased levels of MMPs in NSCLC. Inhibition of MMP expression is likely to account, at least in part, for the decreased invasiveness of these cells. Whereas E-cadherin increases would be associated with a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, the two NSCLC examined normally express epithelial markers, and it is unlikely that the relatively modest changes in E-cadherin expression in response to either rosiglitazone or Snail silencing are sufficient to account for the structural changes observed in three-dimensional culture. Alterations in other genes associated with EMT are likely. Experiments using expression profiling of these cells will better define these changes. The effects of rosiglitazone on COX-2 expression also seem to be mediated through Snail because cells silenced for Snail have lower levels of COX-2. Inhibition of COX-2 has been shown to inhibit anchorage-independent growth in NSCLC [41]. Snail has not been shown to directly regulate the COX-2 promoter, but earlier works from our laboratory and others' have demonstrated COX-2 suppression through either nuclear factor-κB [26] or AP-1 regulation [42].

Suppression of Snail is mediated through the inhibition of transcriptional control, as evidenced by lower levels of mRNA and decreased Snail promoter activity after rosiglitazone stimulation. Although the direct effectors of PPARγ mediating this effect are not clearly defined, our data support a role for the MEK-1/2/ERK family of MAPKs in mediating Snail suppression. Rosiglitazone decreased ERK activity in both cell lines, and a specific MEK inhibitor mimicked the effects of rosiglitazone on Snail expression. The slow time course of ERK inhibition suggests that the effects of rosiglitazone are mediated through altered gene transcription, consistent with the role of PPARγ as a ligand-activated transcription factor. A potential mechanism would be the increased expression of a protein phosphatase that would counteract the effects of MEK phosphorylation of ERK. Global expression profiling of NSCLC overexpressing PPARγ indicates increased expression of multiple protein phosphatases. Although we have examined the expression of DUSP4 and 6, as well as MAPK phosphatase-1 in response to rosiglitazone, to date we have not identified a candidate phosphatase that would mediate the ERK inhibition. Similar regulation of Snail expression has recently been reported in breast cancer, where inhibition of the ERK pathway blocks the induction of Snail by TrkB [43].

Our observations are consistent with other studies analyzing the effects of Snail silencing in various other types of cancer. Snail silencing in mouse skin carcinoma cell lines induces a more differentiated, less invasive phenotype with a significant reduction in their tumorigenic capacity [8]. Snail knockdown also dramatically affects tumor growth and lymph node metastasis of human breast carcinoma cells [8]. It has been reported that Slug cooperates with Snail in tumor growth potential of mouse skin carcinoma cells and in the generation of lung and liver metastasis [8]. A recent study has also implicated ZEB1 as being critical for suppression of the tumor suppressor Semaphorin 3F [19]. Thus, distinct members of the Snail family may participate through both overlapping and nonoverlapping pathways to affect cancer cell growth and metastasis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that suppression of Snail is both necessary and sufficient for many of the responses to rosiglitazone in these cell lines. Both of these cell lines are adenocarcinoma cells harboring oncogenic K-Ras mutations. They are also “epithelial-like” and represent K-Ras-dependent cell lines [44]. It will be important to determine whether Snail plays a comparable role in the responses of other classes of NSCLC to PPARγ activators. This information will be critical in developing novel therapeutic agents targeting Snail as well as in the selection of patients for clinical trials with PPARγ activators.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA103618, CA108610, and CA58187) as well as a University of Colorado Cancer Center Seed Grant to Dr. Weiser-Evans.

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 and W2 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birchmeier W, Behrens J. Cadherin expression in carcinomas: role in the formation of cell junctions and the prevention of invasiveness. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1198:11–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fei Q, Zhang H, Chen X, Wang JC, Zhang R, Xu W, Zhang Z, Zou W, Zhang K, Qi Q, et al. Defected expression of E-cadherin in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;37:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frixen UH, Behrens J, Sachs M, Eberle G, Voss B, Warda A, Lochner D, Birchmeier W. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:173–185. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolos V, Peinado H, Perez-Moreno MA, Fraga MF, Esteller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:499–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olmeda D, Jorda M, Peinado H, Fabra A, Cano A. Snail silencing effectively suppresses tumour growth and invasiveness. Oncogene. 2007;26:1862–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005;132:3151–3161. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver EA, Jiang R, Lan Y, Oram KF, Gridley T. The mouse snail gene encodes a key regulator of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8184–8188. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8184-8188.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang R, Lan Y, Norton CR, Sundberg JP, Gridley T. The Slug gene is not essential for mesoderm or neural crest development in mice. Dev Biol. 1998;198:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco MJ, Moreno-Bueno G, Sarrio D, Locascio A, Cano A, Palacios J, Nieto MA. Correlation of Snail expression with histological grade and lymph node status in breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:3241–3246. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugimachi K, Tanaka S, Kameyama T, Taguchi K, Aishima S, Shimada M, Sugimachi K, Tsuneyoshi M. Transcriptional repressor snail and progression of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2657–2664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohkubo T, Ozawa M. The transcription factor Snail downregulates the tight junction components independently of E-cadherin downregulation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1675–1685. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuo W, Wang Y, Zhuo X, Zhang Y, Ao X, Chen Z. Knockdown of Snail, a novel zinc finger transcription factor, via RNA interference increases A549 cell sensitivity to cisplatin via JNK/mitochondrial pathway. Lung Cancer. 2008;62:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohadwala M, Yang SC, Luo J, Sharma S, Batra RK, Huang M, Lin Y, Goodglick L, Krysan K, Fishbein MC, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of E-cadherin: prostaglandin E2 induces transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and Snail in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5338–5345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih JY, Tsai MF, Chang TH, Chang YL, Yuan A, Yu CJ, Lin SB, Liou GY, Lee ML, Chen JJ, et al. Transcription repressor slug promotes carcinoma invasion and predicts outcome of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8070–8078. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarhaut J, Gemmill RM, Potiron VA, Ait-Si-Ali S, Imbert J, Drabkin HA, Roche J. ZEB-1, a repressor of the semaphorin 3F tumor suppressor gene in lung cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11:157–166. doi: 10.1593/neo.81074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARγ. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarraf P, Mueller E, Jones D, King FJ, DeAngelo DJ, Partridge JB, Holden SA, Chen LB, Singer S, Fletcher C, et al. Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPARγ. Nat Med. 1998;4:1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato Y, Ying H, Zhao L, Furuya F, Araki O, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. PPARγ insufficiency promotes follicular thyroid carcinogenesis via activation of the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:2736–2747. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bren-Mattison Y, Van Putten V, Chan D, Winn R, Geraci MW, Nemenoff RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR(γ)) inhibits tumorigenesis by reversing the undifferentiated phenotype of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer cells (NSCLC) Oncogene. 2005;24:1412–1422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazra S, Xiong S, Wang J, Rippe RA, Krishna V, Chatterjee K, Tsukamoto H. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ induces a phenotypic switch from activated to quiescent hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11392–11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keshamouni VG, Reddy RC, Arenberg DA, Joel B, Thannickal VJ, Kalemkerian GP, Standiford TJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation inhibits tumor progression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:100–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bren-Mattison Y, Meyer AM, Van Putten V, Li H, Kuhn K, Stearman R, Weiser-Evans M, Winn RA, Heasley LE, Nemenoff RA. Antitumorigenic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in non-small-cell lung cancer cells are mediated by suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 via inhibition of nuclear factor-κB. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:709–717. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keshamouni VG, Arenberg DA, Reddy RC, Newstead MJ, Anthwal S, Standiford TJ. PPAR-γ activation inhibits angiogenesis by blocking ELR+CXC chemokine production in non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:294–301. doi: 10.1593/neo.04601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wick M, Hurteau G, Dessev C, Chan D, Geraci MW, Winn RA, Heasley LE, Nemenoff RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ is a target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs mediating cyclooxygenase-independent inhibition of lung cancer cell growth. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1207–1214. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernhard EJ, Muschel RJ. Ras, metastasis, and matrix metalloproteinase 9. Methods Enzymol. 2001;333:96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)33048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee G, Elwood F, McNally J, Weiszmann J, Lindstrom M, Amaral K, Nakamura M, Miao S, Cao P, Learned RM, et al. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19649–19657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumei S, Motomura W, Yoshizaki T, Takakusaki K, Okumura T. Troglitazone increases expression of E-cadherin and claudin 4 in human pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yook JI, Li XY, Ota I, Hu C, Kim HS, Kim NH, Cha SY, Ryu JK, Choi YJ, Kim J, et al. A Wnt-Axin2-GSK3β cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, Hung MC. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roman J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and lung cancer biology: implications for therapy. J Investig Med. 2008;56:528–533. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e3181659932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemenoff RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in lung cancer: defining specific versus “off-target” effectors. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:989–992. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318158cf0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki H, Tanahashi M, Yukiue H, Moiriyama S, Kobayashi Y, Nakashima Y, Kaji M, Kiriyama M, Fukai I, Yamakawa Y, et al. Decreased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ gene expression was correlated with poor prognosis in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;36:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Govindarajan R, Ratnasinghe L, Simmons DL, Siegel ER, Midathada MV, Kim L, Kim PJ, Owens RJ, Lang NP. Thiazolidinediones and the risk of lung, prostate, and colon cancer in patients with diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1476–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen D, Jin G, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu H, Liu Y, Fan W, Ma H, Miao R, Hu Z, et al. Genetic variants in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ gene are associated with risk of lung cancer in a Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:342–350. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heasley LE, Thaler S, Nicks M, Price B, Skorecki K, Nemenoff RA. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by oncogenic Ras in human non-small cell lung cancer. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14501–14504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subbaramaiah K, Lin DT, Hart JC, Dannenberg AJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands suppress the transcriptional activation of cyclooxygenase-2. Evidence for involvement of activator protein-1 and CREB-binding protein/p300. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12440–12448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smit MA, Geiger TR, Song JY, Gitelman I, Peeper DS. A Twist-Snail axis critical for TrkB-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like transformation, anoikis resistance, and metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3722–3737. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01164-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, Settleman J. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.