Abstract

Tribbles homolog 3 (TRIB3) was found to inhibit insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation and modulate gluconeogenesis in rodent liver. Currently, we examined a role for TRIB3 in skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Ten insulin-sensitive, ten insulin-resistant, and ten untreated type 2 diabetic (T2DM) patients were metabolically characterized by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic glucose clamps, and biopsies of vastus lateralis were obtained. Skeletal muscle samples were also collected from rodent models including streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, db/db mice, and Zucker fatty rats. Finally, L6 muscle cells were used to examine regulation of TRIB3 by glucose, and stable cell lines hyperexpressing TRIB3 were generated to identify mechanisms underlying TRIB3-induced insulin resistance. We found that 1) skeletal muscle TRIB3 protein levels are significantly elevated in T2DM patients; 2) muscle TRIB3 protein content is inversely correlated with glucose disposal rates and positively correlated with fasting glucose; 3) skeletal muscle TRIB3 protein levels are increased in STZ-diabetic rats, db/db mice, and Zucker fatty rats; 4) stable TRIB3 hyperexpression in muscle cells blocks insulin-stimulated glucose transport and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation and impairs phosphorylation of Akt, ERK, and insulin receptor substrate-1 in insulin signal transduction; and 5) TRIB3 mRNA and protein levels are increased by high glucose concentrations, as well as by glucose deprivation in muscle cells. These data identify TRIB3 induction as a novel molecular mechanism in human insulin resistance and diabetes. TRIB3 acts as a nutrient sensor and could mediate the component of insulin resistance attributable to hyperglycemia (i.e., glucose toxicity) in diabetes.

Keywords: glucose toxicity, type 2 diabetes, insulin signaling

the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is rapidly increasing in Westernized nations. Although it likely results from both genetic and environment factors, a key pathogenic characteristic of T2DM is insulin resistance, due to impaired stimulation of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of insulin resistance, we have performed cDNA microarray studies to systematically assess differential gene expression in skeletal muscle from insulin-sensitive (IS) vs. insulin-resistant (IR) humans (59, 60). These analyses identified Tribbles homolog 3 (TRIB3) as a gene with increased expression in patients with T2DM. Tribbles was first identified by Mata et al. (31) in 2000 as a regulator of germ-cell development in Drosophila (31). Tribbles inhibits mitosis and regulates DNA damage repair by promoting ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of specific cell cycle regulators early in development (17, 31, 46, 49). Mammals express a family of three genes, TRIB1, TRIB2, and TRIB3, that are homologous to Tribbles. These family members are characterized by a variant kinase domain in the center of molecule with a high homology to serine/threonine kinases (22). However, they appear to lack the key residues for catalytic activity (e.g., DLKLRK in TRIB3 vs. DLKPEN consensus) and contain a highly divergent primary structure in the consensus ATP-binding pocket, precluding ATP binding (21). This structure is consistent with the designation of Tribbles proteins as pseudokinases.

The function of Tribbles proteins in mammals is not fully understood. The Drosophila TRIB3 can promote cell death in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Human TRIB3 is induced by the interacting transactivators, activating transcription factor 4, and C/EBP homologous protein, which are overexpressed in certain tumors (5, 36, 62). With respect to metabolic functions, several studies (10, 28, 58) have demonstrated that TRIB3 directly inhibits insulin-mediated phosphorylation of Akt in liver. In adipose tissue, TRIB3 inhibits lipid synthesis by promoting the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the rate-limiting enzyme acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase through an interaction with the COP1 E3 ubiquitin ligase (43). However, two recent studies have called into question the regulatory role of TRIB3 in metabolism. Iynedjian (24) reported that glucagon, glucocorticoids, and insulin had no effect on the level of endogenous TRIB3 mRNA in primary hepatocytes even though these hormones induced key metabolic genes, including glucokinase and sterol-regulatory-element-binding factor 1, and enhanced phosphorylation of Ser473 and Thr308 of Akt. More strikingly, TRIB3 null mice (TRIB3−/−) were essentially identical to their wild-type littermates in overall appearance and body composition without any alteration in serum glucose, insulin, or lipid levels; glucose or insulin tolerance; or energy metabolism (37). The reason for these discrepancies remains unclear.

Insulin stimulates the glucose transport system via a signal transduction pathway that involves tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), docking and activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), production of PI-3,4,5-triphosphate, and phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase B (Akt, PKB/Akt). Indeed, insulin action defects in skeletal muscle of IR patients include both impaired signal transduction leading to decreased Akt phosphorylation (2) and defects intrinsic to the glucose transport apparatus (13). Insulin and other mitogens induce MAPK cascades that control the activity of ERKs. Interestingly, TRIBs are mitogen responsive and appear to inhibit MAPK signaling when overexpressed in HeLa cells (25), epithelial cells, and macrophages (52). However, the role of TRIB3 in skeletal muscle MAPK signaling is unknown. Thus we examined the effect of the TRIB3 level on ERK signaling in skeletal muscle. ER stress has been shown previously to induce TRIB3 gene expression (36) and impair insulin signaling by excessive serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (38, 39). Serine-threonine phosphorylation of IRS-1 is a major mechanism for negative modulation of insulin signal transduction. Therefore, we also investigated whether TRIB3 could diminish insulin-mediated phosphorylation of IRS-1 and stimulation of glucose transport.

Here, we report that TRIB3 was significantly upregulated in skeletal muscle of patients with T2DM, streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, db/db mice, and Zucker fatty rats. We also report on a human cohort in which protein expression of TRIB3 in skeletal muscle was found to be inversely correlated with insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rates and highly positively correlated with fasting glucose levels. Furthermore, stable overexpression of TRIB3 in L6 muscle cells blocked insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt, ERK1/2, and IRS-1 and diminished insulin's ability to stimulate glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation and glucose transport. Additionally, TRIB3 expression in wild-type L6 myocytes was sensitive to ambient glucose concentration and was increased by both high glucose and glucose deprivation vs. normal glucose concentration. Our results provide evidence for a glucose-induced mechanism of insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle that involves TRIB3's ability to impair the insulin responsive glucose transport system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Subjects

We studied 10 IS, 10 normoglycemic IR, and 10 untreated T2DM subjects. All subjects were equilibrated as outpatients for 3 days on an isocaloric diet comprised of 20% protein, 30% fat, and 50% carbohydrate calories. Weight had been stable (±3%) for at least 3 mo, and none of the study subjects engaged in regular exercise. Before the study, all patients with T2DM were being treated with diet or sulfonylurea and/or metformin but were withdrawn from therapy for at least 3 wk and followed on an outpatient basis. The subjects were then admitted as inpatients on a metabolic ward. Skeletal muscle was obtained by percutaneous biopsy from the vastus lateralis for analyses as previously described (60). On a separate day, insulin sensitivity was measured using 3-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps. Maximal rates of glucose disposal were normalized for kilogram of lean body mass assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans as described previously (60). All studies were performed in the postabsorptive state after an overnight fast. The clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. All volunteers had normal physical examinations and were verified by blood chemistry examination to have normal hepatic, renal, and thyroid functions. None of the subjects were taking medications that would affect metabolism or glucose homeostasis. All study volunteers provided written informed consent, and the studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Medical University of South Carolina and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, and metabolic characteristics of the human subjects included in this study

| Variable | Insulin-Sensitive Normoglycemic | Insulin-Resistant Normoglycemic | Type 2 Diabetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 28.6 ± 1.7 | 33.8 ± 2.6 | 46.2 ± 4.0† |

| Sex | 6 male, 4 female | 3 male, 7 female | 3 male, 7 female |

| Race | 8 Caucasian, 2 Black | 6 Caucasian, 3 Black, 1 Hispanic | 6 Caucasian, 4 Black |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.4 ± 1.3 | 30.7 ± 1.9* | 30.1 ± 1.1* |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 85.9 ± 2.5 | 89.5 ± 1.9 | 220.3 ± 20.2† |

| Insulin, μU/ml | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 10.8 ± 1.4* | 11.2 ± 1.6* |

| GDR/LBM, mg·kg−1·min−1 | 15.1 ± 0.3 | 10.8 ± 0.8* | 6.3 ± 0.7† |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 89 ± 11 | 112 ± 10 | 174 ± 39* |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 44 ± 3 | 36 ± 3 | 35 ± 2* |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 176 ± 11 | 168 ± 6 | 184 ± 14 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 116 ± 9 | 110 ± 6 | 114 ± 11 |

| VLDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 19 ± 2 | 22 ± 2 | 35 ± 8 |

| Systolic blood pressure supine, mmHg | 113 ± 3 | 113 ± 5 | 125 ± 5* |

| Diastolic blood pressure supine, mmHg | 65 ± 2 | 64 ± 4 | 76 ± 2† |

Data are means ± SE. GDR/LBM is glucose disposal rates normalized per lean body mass during hyperinsulinemic clamps and is a measure of insulin sensitivity. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Significantly different from insulin-sensitive subjects;

significantly different from insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant subjects.

Rodent Models of Insulin Resistance

All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. All animals were maintained under standard conditions: a 12-h light-dark cycle, 22°C, free access to water, and standard rodent diet.

STZ-treated rats.

Adult male (200–250 g) Wistar rats were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of streptozotocin (50 mg/kg body wt in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5) as previously described (19). Control animals received only the vehicle buffer. Animals were considered diabetic when fasting blood glucose was >250 mg/dl measured using a glucometer (Accu-check Advantage II glucometer; Roche).

C57BL/6 control and db/db mice.

Experiments were conducted using 15- to 16-wk old male C57BL/6 control and db/db mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME).

Zucker fatty rats with or without pioglitazone treatment.

Zucker fatty rats and lean male littermates (fa−/+ or fa+/+) were purchased form Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) at age of 8 wk. The rats were kept for an additional 3 wk over which time half of the Zucker fatty rats were treated with pioglitazone (10 mg·kg−1·day−1; Ref. 40). Biweekly food intakes and body weights were recorded.

Cell Culture

L6 muscle cells, derived from rat thigh muscle tissue, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured as previously described (60). L6 myoblasts stably expressing GLUT4 (a kind gift from Dr. A. Klip, University of Toronto, Hospital for Sick Children) with an exofacial myc epitope (L6-GLUT4myc) were maintained in culture as previously described (57). All L6 muscle myoblasts were maintained in medium consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 4.5 g/l l-glutamine, 1.5 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/l glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. To obtain differentiated L6 myotubes, postconfluent L6 myoblasts were maintained in DMEM medium containing 2% FBS for 6 days before experiments.

Recombinant Lentiviruses and Stable Lentiviral-Transduced Cell Lines

Wild-type TRIB3 was kindly provided by Dr. Kiss-Toth (University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK). Lentivirus vector construction and packaging were performed by ADV Bioscience (Birmingham, AL). Briefly, the stop codon in the TRIB3 cDNA was removed and c-Myc was added at the C terminal. The modified cDNA was ligated into lentivector (pHR-EF-IRES-Bla) at the BamHI and XhoI sites, followed by DNA sequencing confirmation. Blasticidin driven by the same promoter EF-1a through IRES was used to select for successful transfectants. Lentiviruses were packaged by transfecting 293T cells, with vsv-g as envelope protein. Titers of the packaged virus for further experiments were in the range of 2–5 × 106 IU/ml. To establish stably expressing cell lines, recombinant TRIB3 or myc lentiviral stocks were used to infect L6 or L6-GLUT4myc cells. Forty-eight hours posttransduction, cells were placed under blasticidin selection (20 μg/ml) for 20 days to obtain stably transfected clonal cell lines.

Glucose Transport Assays

These experiments were performed as described previously (33). To measure basal and maximally stimulated glucose transport rates, L6-GLUT4myc cells were incubated in the absence and presence of 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C to measure basal and maximally stimulated glucose transport rates. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined by lysing the cells with 0.05 N NaOH, followed by liquid scintillation counting. Total cellular protein was determined by the Bradford method.

GLUT4myc Translocation Assay

The movement of intracellular myc-tagged GLUT4 to the cell surface upon insulin stimulation was measured by an antibody-coupled colorimetric assay. L6-GLUT4myc cells were washed once with PBS and then fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 3 min at room temperature. Fixative was immediately neutralized by incubation with 1% glycine in PBS at 4°C for 10 min. Next, cells were blocked with 10% goat serum and 3% BSA in PBS at 4°C for at least 30 min. Primary monoclonal antibody (anti-c-myc, 9E10) was then added to the cultures at a dilution of 1:100 and maintained for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were extensively washed with PBS before introducing peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000). After 30 min at 4°C, the cells were extensively washed and 1 ml of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride reagent (0.4 mg/ml o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride and 0.4 mg/ml urea hydrogen peroxide in 0.05 M phosphate/citrate buffer) was added to each well for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of 0.25 ml of 3 N HCl. The supernatant was collected, and the optical absorbance, measured at 492 nm, reflected the amount of immunoreactive cell surface GLUT4myc. Intra-assay control wells remained untreated with either primary antibody or both primary and secondary antibodies. Measurements of surface GLUT4myc in control wells were subtracted from values obtained from all other experimental conditions.

RNA Preparation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Tissue samples were immediately frozen liquid nitrogen, pulverized, and then subjected to extraction of total RNA using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,). RNA concentration and integrity were assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies).

For quantitative RT-PCR, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and amplified by real time PCR on a MX3000 apparatus (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as previously described (60). Specific oligonucleotide primers were as follows: for human 18S, 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ (5′-primer) and 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′ (3′-primer); and for human TRIB3, 5′-GTTCCACACACATGCAGTTCCT-3′ (5′-primer), 5′-TCTCCTTTGCTCACTGCTGTACTC-3′ (3′-primer). TRIB3 mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA, and the results were expressed as arbitrary mRNA units. Amplification products were routinely checked by gel electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and then visualized under ultraviolet light following staining with 0.05% ethidium bromide to confirm the size and specificity of the DNA fragment.

Antibodies and Immunoblot Analyses

Antibodies used for Western blotting included anti-phosphoserine-Akt (Ser473; Ref. 61), anti-total Akt, anti-phosphothreonine 202 and phosphotyrosine 204 ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-total ERK1/2, and anti-phospho-AMPK-α Thr172 antibody (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-phosphotyrosine-IRS-1 (Tyr612; Invitrogen); anti-TRIB3 (rabbit pAb; Calbiochem); and anti-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish-peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL).

The levels of total and phosphorylated proteins were assessed in cell lysates by immunoblotting. Cells were treated with or without 100 nM insulin for the indicated time points and then washed twice with PBS. Cells or tissues were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Na deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM Na3VO4, 2 mg/ml pepstatin, 2 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (16,000 g for 15 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was collected. Aliquots of these lysates (30 μg protein) were heated for 10 min at 100°C, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and reacted with antibodies against TRIB3, phosphorylated IRS-1 (pIRS-1), phosphorylated Akt (pAkt), total Akt, phosphorylated ERK (pERK), total ERK, and phospho-AMPK. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence method according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce). Multiple exposures of each blot were used to obtain gray-scale images of each chemiluminescent band and were quantified with the Fluorchem FC imager system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Other Assays

In humans, plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method using a glucose analyzer (YSI 2300; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Serum insulin levels were measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). In our laboratory, the insulin assay has a mean intra-assay coefficient of variation of 5% and a mean inter-assay coefficient of variation of 6%. Standard plasma clinical chemistry assays included the lipid panel (triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and VLDL cholesterol; Vitos Autoanalyzer, Johnson and Johnson) and hemoglobin A1c (Bio-Rad Hemoglobin Analyzer).

In rodents, glucose and triglycerides were measured by Stanbio Sirrus automated analyzer (Boerne, TX) using the glucose oxidase reagent for glucose and glycerylphosphate oxidase method for triglycerides. Insulin was measured using radioimmunoassay RIA kit (Linco, Millipore, St. Charles, MO). Plasma free fatty acids were measured using a NEFA C kit (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). As described by the manufacturer, the NEFA intra-assay coefficient of variation is 0.8%.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between mean values were performed using Student's t-tests or ANOVA as appropriate. Correlations between TRIB3 protein level, fasting glucose, glucose disposal rate, diastolic blood pressure, and lipid measurements were examined using Spearman correlation coefficients. All calculations were performed using PRISM version 4 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and SAS statistical software (version 8.02, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The threshold for significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Tissue-Specific Expression Pattern of TRIB3

To assess tissue-specific expression of TRIB3, we performed real-time RT-PCR analysis in 17 human tissues. As shown in Fig. 1, TRIB3 was detectable in most tissues with the highest level of expression in liver. We also observed readily detectable expression in other insulin target tissues such as adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and cardiac muscle.

Fig. 1.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Tribbles homolog 3 (TRIB3) mRNA levels in human tissues collected from adipose (n = 5), appendix (n = 2), artery (n = 7), bladder (n = 4), colon (n = 10), esophagus (n = 8), gallbladder (n = 5), heart (n = 8), liver (n = 5), lung (n = 10), lymph node (n = 5), skeletal muscle (n = 9), small intestine (n = 8), spleen (n = 2), stomach (n = 8), and trachea (n = 5), respectively. Data are means ± SE.

TRIB3 Expression in Human Skeletal Muscle

To determine whether TRIB3 expression in skeletal muscle was altered in human insulin resistance, we studied subgroups of IS, normoglycemic IR, and untreated T2DM patients. Insulin sensitivity was quantified by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, and maximally stimulated glucose disposal rates (GDR) were normalized for lean body mass (LBM). As shown in Table 1, both insulin-resistant groups (IR and T2DM) exhibited significantly higher body mass index and fasting serum insulin and lower GDR than the IS group. The level of muscle TRIB3 mRNA appeared to be higher in skeletal muscle from IR and T2DM patients than that from IS patients, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2A). However, muscle TRIB3 protein levels were significantly increased (by ∼2-fold) in T2DM patients compared with IS individuals as shown in Fig. 2B. TRIB3 protein levels in the IR group were intermediate between IS and T2DM with no statistical significance compared with either IS or T2DM. We also measured the protein level of total ERK and actin in the same human skeletal muscle samples, with no change observed (data not shown). Therefore, total ERK was used as the gel-loading control for the immunoblots.

Fig. 2.

A: real-time RT-PCR analysis of TRIB3 mRNA levels in human skeletal muscle collected from insulin-sensitive (IS) and insulin-resistant (IR) subjects and from patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). B: TRIB3 protein levels in human skeletal muscle from IS (n = 10), IR (n = 10), and T2DM (n = 10) subjects. TRIB3 protein was detected by Western blotting and was quantified by densitometry. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

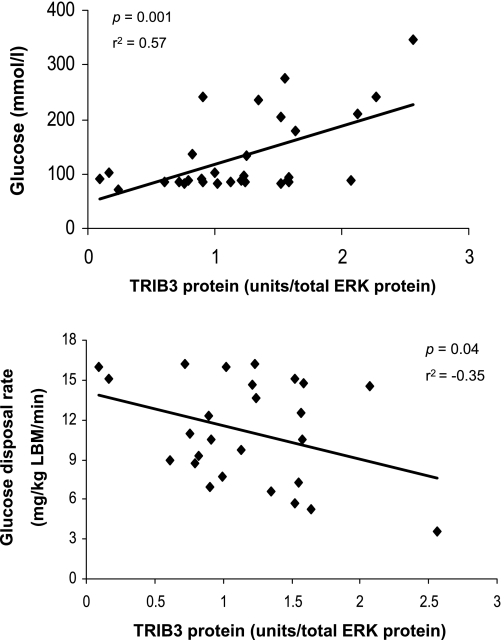

Since insulin sensitivity is a continuous variable, we correlated the values of muscle TRIB3 protein content in all subjects with GDR/LBM to further assess the relationship between TRIB3 and insulin resistance, and we observed a statistically significant inverse relationship (r2 = −0.35; P < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 3, there was a progressive increase in muscle TRIB3 as individuals became more insulin resistant (i.e., declining GDR/LBM values). Furthermore, muscle TRIB3 protein levels were also significantly correlated with fasting glucose (r = 0.57; P < 0.001), but we did not find any significant correlation between TRIB3 protein level and body mass index or waist circumference (data not shown). When stepwise multiple regression modeling was used to determine whether fasting glucose or GDR/LBM is more predictive of TRIB3 protein levels, GDR/LBM fell out of the model while fasting glucose remained a strong predictor (P = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between muscle TRIB3 protein expression and fasting plasma glucose (top) and glucose disposal rate normalized by lean body mass (GDR/LBM) as a measure of insulin sensitivity (bottom). TRIB3 protein level was determined by Western blotting. Data were based on studies of individuals over a broad range of insulin sensitivity, including subgroups of IS and IR and T2DM subjects. Correlation coefficient (r) and P values are shown for each graph.

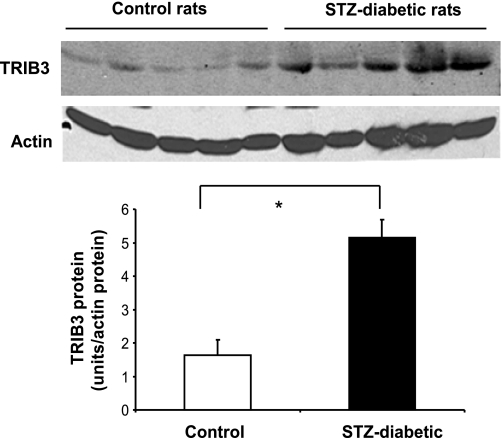

Muscle TRIB3 Expression in Rodent Models of Insulin Resistance

To determine whether muscle TRIB3 expression is altered in rodent models of insulin resistance and diabetes, we first quantified TRIB3 levels by Western blot in skeletal muscle collected from control and STZ-treated diabetic rats. Mean TRIB3 protein levels were significantly increased (by ∼3-fold) in STZ-induced diabetic rats compared with control animals (Fig. 4). Skeletal muscle TRIB3 levels were similarly measured in db/db mice. Compared with lean controls, db/db mice were more obese (29 ± 1 vs. 48 ± 2 g, respectively) and hyperglycemic (fasting glucose 6.2 ± 0.4 vs. 22.5 ± 1.9 mM, respectively), and muscle protein content of TRIB3 was augmented by approximately threefold, as shown in Fig. 5. Finally, 12-wk-old Zucker fatty rats were only slightly hyperglycemic, with marked elevations in fasting insulin, free fatty acids, and triglycerides, compared with lean controls. In addition, 3 wk of antecedent pioglitazone treatment in the Zucker fatty rats led to significant reductions in fasting glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, and triglycerides relative to untreated Zucker fatty rats, as shown in Fig. 6. TRIB3 protein levels in gastrocnemius muscle were significantly increased (by 55%) in insulin-resistant Zucker fatty rats compared with lean controls (P < 0.05). Pioglitazone treatment led to a 10% decrease in TRIB3 levels in Zucker fatty rats compared with untreated Zucker fatty rats, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. We also examined the level of TRIB3 in liver collected from these animals. We found that TRIB3 protein levels in the liver were significantly increased (by 63%) in insulin-resistant Zucker fatty rats compared with lean controls (P < 0.05). Pioglitazone treatment led to a 30% decrease in liver TRIB3 protein compared with the level of untreated Zucker fatty rats, which was not significantly different from the level in lean controls (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Levels of TRIB3 protein expression in skeletal muscle from control rats (n = 5) and streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetics rat (n = 5) as determined by Western blotting. Results were quantified by densitometry, and data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

A: mean body weight and fasting plasma glucose levels in lean control mice (n = 3) and 3 db/db mice (n = 3). B: TRIB3 protein levels in skeletal muscle from lean control mice (n = 3) and from db/db mice (n = 3) as determined by Western blotting. Results were quantified by densitometry, and data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

A: plasma glucose and serum triglyceride concentrations in lean control rats (white bar) and Zucker fatty rats with (gray bar) or without (hatched bar) pioglitazone treatment. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with lean controls; ‡P < 0.05, compared with Zucker fatty rats without pioglitazone treatment. n = 6/group. B: serum free fatty acid (FFA) and insulin concentrations in lean control (white bar) and Zucker fatty rats with (gray bar) or without (hatched bar) pioglitazone treatment. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, compared with lean controls, ‡P < 0.05, compared with Zucker fatty rats without pioglitazone treatment. n = 6/group. C: TRIB3 protein expression in skeletal muscle from lean rats (n = 6) and Zucker fatty rats without pioglitazone treatment (n = 6) and with pioglitazone treatment (n = 6) as determined by Western blotting. Results were quantified by densitometry, and data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Effects of TRIB3 on Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Transport Activity and GLUT4 Translocation

To examine the mechanisms underlying the association between increased muscle TRIB3 expression and reduced GDR in humans, we tested whether TRIB3 could modulate insulin-stimulated glucose transport activity. Control L6-GLUT4myc cells exhibited a 2.3-fold increase in glucose uptake after insulin treatment. In contrast, TRIB3 overexpression completely blocked insulin-stimulated glucose uptake with no effect on the basal transport rate (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

A: basal (open bar) and maximally insulin-stimulated (solid bar) glucose transport rates in L6-GLUT4myc cells stably transduced with either a lentiviral myc expression vector as a control or with a lentiviral TRIB3 expression vector. Data are means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. 2-DG, 2-deoxy-d-glucose. *P < 0.05. B: quantitative analyses of cell-surface GLUT4myc content with or without insulin treatment. Open bar represents cell surface glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) under basal conditions (without insulin treatment); solid bar represents insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation to cell surface. Data are means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < 0.05.

Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake is mediated by translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters from the intracellular compartment to the plasma membrane (7, 51). Surface GLUT4 was assayed by immunofluorescent detection of the myc epitope introduced on the first exofacial loop of the GLUT4 molecule (56). As shown in Fig. 7B, TRIB3 abolished the increase in cell-surface appearance of GLUT4 in response to insulin without effecting basal cell-surface GLUT4 in control cells. This is consistent with our findings that TRIB3 blocked insulin-stimulated, but not basal, glucose transport.

Role of TRIB3 in Insulin Signal Transduction

We next examined whether TRIB3 could impair insulin signaling by measuring insulin's ability to phosphorylate IRS-1, Akt, and ERK. L6 cells were stably transduced using a lentiviral expression vector for either TRIB3 or myc and then were stimulated with insulin. As shown in Fig. 8, A–C, insulin augmented phosphorylation of IRS-1, Akt, and ERK in control cells; however, these effects were dramatically diminished in TRIB3-overexpressing cells. Total immunoreactive IRS-1, Akt, and ERK were not altered under these experimental conditions. Overexpression of TRIB3 caused an increase in ERK phosphorylation under basal conditions (i.e., absence of insulin) compared with ERK phosphorylation in basal control cells, although this increase was not statistically significant. These effects were also observed in transient transfection experiments using plasmid vector cells transiently overexpressing TRIB3 for shorter time periods, e.g., 6 or 24 h (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

A: effects of TRIB3 hyperexpression on insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt in L6 muscle cells. L6 cells were stably transfected with a lentivirus construct for hyperexpression of myc as control or TRIB3 and were then treated with (+) or without (−) 10 nM insulin for 45 min. pAkt and total Akt were measured by Western blotting. B: effects of TRIB3 hyperexpression on insulin-induced phosphorylation of ERK in L6 muscle cells. C: effects of TRIB3 hyperexpression on insulin-induced phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) in L6 muscle cells. Representative blots are shown, and data are means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < 0.05.

Finally, to confirm that alterations in insulin action were not due to nonspecific effects of TRIB3 overexpression on cell viability and/or differentiation, L6 cells and L6-GLUT4myc cells stably infected with myc- or TRIB3-expressing vectors were analyzed by flow cytometry. Our results suggested that TRIB3 did not significantly alter the population of cells that were in the G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle or increase apoptosis in stable L6 or L6-GLUT4myc cells (data not shown).

Effects of Glucose on TRIB3 Expression in L6 Muscle Cells

Human muscle TRIB3 levels were increased in T2DM but not in nondiabetic IR subjects when compared with IS subjects, and because TRIB3 levels were positively correlated with fasting glucose levels, we hypothesized that TRIB3 could be induced by hyperglycemia and contribute to insulin resistance in diabetes. To explore this possibility, we first examined whether TRIB3 was a glucose-responsive gene. We exposed fully differentiated wild-type L6 myotubes to various media glucose concentrations (0–15 mM) for 16–18 h and measured TRIB3 expression at the level of both mRNA and protein. The results are summarized in Fig. 9, A and B. The lowest levels of expression were observed in the physiological glucose range (5 mM), whereas TRIB3 expression increased dramatically by 5.3-fold as the glucose concentrations were increased to 10–15 mM and also progressively increased with lower glucose concentrations (0–2.5 mM). These changes were observed for both TRIB3 mRNA and protein. To exclude the possibility that the increments in TRIB3 mRNA and protein expression were due to osmolarity differences in the medium, we demonstrated that l-glucose at similar concentrations did not produce any significant changes in TRIB3 expression (Fig. 9C). Furthermore, to confirm that our systems were responding appropriately to glucose in these cells, we analyzed the expression of AMPK, an important nutrient sensor that is activated by increases in the cellular AMP-to-ATP ratio and by ATP depletion under conditions of glucose deprivation (18, 66). In cultured L6 cells in the presence of various media glucose concentrations (0–15 mM), we found that the levels of activated phospho-AMPK were highest in cells exposed to 0 mM glucose, lower in cells cultured with 5 mM glucose, and undetectable at 15 mM glucose (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Changes in TRIB3 mRNA levels (A) and TRIB3 protein levels (B) in L6 myotubes in response to different d-glucose media concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 15 mM). mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR, while protein was analyzed by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry. Representative blot is shown, and data are means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. C: pAMPK protein levels in L6 myotubes in response to different d-glucose concentrations (0, 5, and 15 mM) and l-glucose (15 mM). Representative blot is shown, and data are means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of TRIB3 in insulin action and substrate metabolism in skeletal muscle. We showed for the first time that TRIB3 protein levels were elevated in skeletal muscle from T2DM patients compared with normoglycemic IS individuals. Furthermore, TRIB3 expression in human muscle was negatively correlated with insulin-stimulated GDR/LBM (i.e., insulin sensitivity), and this relationship was explained by a positive correlation with the level of fasting glucose, which was elevated in the insulin-resistant T2DM patients. These results were paralleled by our findings in rodents where muscle TRIB3 levels were substantially elevated in STZ-induced diabetic rats and hyperglycemic db/db mice and more modestly elevated in mildly hyperglycemic Zucker fatty rats.

Defects causing insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion in T2DM are partially reversible following a period (∼2–3 wk) of therapeutic normalization of glycemia (14). These studies indicate that insulin resistance in T2DM is comprised of both a reversible component that can be corrected by intensive glycemic control and a nonreversible component that may antedate the development of diabetes as exists in subjects with prediabetes and metabolic syndrome (12). These observations, coupled with findings that elevated glucose concentrations can recapitulate these defects in cultured cell systems and rodent models, have given rise to the concept of glucose-induced insulin resistance or “glucose toxicity” (3, 12, 29). Our data suggest that TRIB3 could contribute to the worsening of insulin resistance that accompanies hyperglycemia. These observations include 1) muscle TRIB3 levels were only significantly elevated in T2DM patients with overt hyperglycemia and not in nondiabetic individuals with insulin resistance; 2) muscle TRIB3 levels were correlated with both fasting glucose and GDR in the combined study cohort, and these relationships were driven by elevated muscle TRIB3 levels in the T2DM patients who were the most insulin resistant; 3) muscle TRIB3 was elevated in markedly hyperglycemic rodent models regardless of whether the animals were hypoinsulinemic (STZ-induced diabetes in rats), hyperinsulinemic (db/db mice), or modestly hyperglycemic (Zucker fatty rats), and pioglitazone treatment lowered both fasting glucose and TRIB3 proteins levels in both liver and muscle although the decrement did not achieve statistical significance; and 4) TRIB3 expression is glucose responsive. In L6 myotubes, both TRIB3 mRNA and protein levels were at their lowest in the presence of 5 mM glucose but were dramatically increased by 5.3-fold as the media glucose concentration was increased to 15 mM. Interestingly, TRIB3 levels were also markedly elevated by glucose deprivation (≤2.5 mM). This indicates that TRIB3 expression is involved in nutrient-sensing mechanisms that are operative under the pathophysiological conditions of both hyperglycemia and glucose deprivation. Thus based on the weight of the combined current data, we posit that TRIB3 contributes to the reversible component of insulin resistance in diabetes that is attributable to hyperglycemia or glucose toxicity.

We further determined whether TRIB3 affects insulin-stimulated glucose transport. Hyperexpression of TRIB3 in stably transduced L6-GLUT4myc muscle cells abrogated insulin's ability to stimulate glucose transport activity. We further demonstrated that this effect was due to impaired translocation of GLUT4 transporters in response to insulin. One possible explanation for the diminution in insulin-mediated GLUT4 translocation is that TRIB3 could impair insulin signal transduction. Indeed, TRIB3 hyperexpression reduced Akt, ERK, and IRS-1 phosphorylation in L6 muscle cells. Our findings regarding Akt phosphorylation agree well with previous studies in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (4), chondrocytes (6), and hepatocytes (10, 58). In addition, a high-fructose diet significantly increases TRIB3 and significantly decreases phospho-Akt (Ser473) in rat adipose tissue (4). A previous report by Koh et al. (27) also demonstrated that transient overexpression of TRIB3 in C2C12 muscle cells results in impaired insulin signaling via reduced Akt phosphorylation. Interestingly, our data further demonstrated that overexpression of TRIB3 downregulated insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of both ERK and IRS-1, indicating that the negative modulatory effects of TRIB3 on signal transduction may extend beyond the effects on Akt per se. Accordingly, TRIB3 has been shown to inhibit insulin-induced S6K1 activation and protein synthesis (32) and phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3; Ref. 20). Thus TRIB3 could function upstream and downstream of Akt and control a variety of factors that are involved in both insulin signal transduction and nutrient sensing (i.e., effects on IRS-1, S6K1, and GSK3).

The role of TRIBs in modulation of ERK activation has also been reported in several previous studies using systems other than muscle cells (53). In diabetic cardiomyopathy, advanced glycation end products cause collagen deposition through activation of ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK. After inhibiting TRIB3 with small-interfering RNA, phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK by advanced glycation end products was attenuated (54). TRIB3 proteins appear to act as activators and inhibitors of MAPK activity, depending on the ratio of TRIB3 to MAPKK in the cell. In mammalian cells, TRIB3 at a relatively low level can activate MAPK phosphorylation, especially ERK1/2 phosphorylation (25, 26). Interestingly, overexpression of TRIB3 decreased insulin-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in muscle cells but increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation under basal conditions in our experiments. This could be due to an impact on ER stress by TRIB3, since activation of endogenous ERK plays a critical role in controlling cell survival by resisting ER stress-induced cell death signaling (8, 11, 23). We also found that TRIB3 overexpression in muscle cells led to decreased insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of IRS-1. In line with this, TRIB3 has been shown to respond to nutrient starvation in prostate carcinoma cells and liver cells in a PI3K-dependent manner (32, 48). However, Andreozzi et al. (1) reported previously that there were no changes in insulin-mediated activation of IRS-1 and PI3K in human cells naturally carrying the TRIB3 R84Q gain of function mutation. This difference could be due to the use of a different cell line and the different analytic systems. Andreozzi et al. used primary cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells, while rat muscle L6 cells were studied in the current study. Most importantly, Andreozzi et al. investigated the impact of the TRIB3 R84 variant on the effect of endothelial insulin on nitric oxide production. We investigated insulin action on glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. However, the apparent discrepancy between our study and Andreozzi's is not surprising since TRIB3 has been shown to have diverse functional roles in several pathways depending on the cellular context (9).

In rat pancreatic β-cells, high glucose treatment results in higher TRIB3 expression, and overexpression of TRIB3 mimics glucotoxic effects on insulin secretion and cell growth (44). This is in agreement with our finding that TRIB3 is a glucose-responsive gene and can impair insulin action in muscle. Previous studies have demonstrated that chronic exposure to high glucose can impair glucose transporter translocation (15) and diminish Akt phosphorylation (35, 45). Our data support the idea that these effects could be mediated, at least in part, via increased expression of TRIB3. Our results are not concordant with those of Yacoub Wasef et al. (63), who reported that incubating L6 myotubes overnight in 25 mM glucose decreased TRIB3 mRNA expression compared with that observed at 5 mM glucose. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. However, in agreement with Yacoub Wasef's study, we observed dramatically increased mRNA and protein expression of in response to glucose depletion. The bimodal response of TRIB3 could be explained by different mechanisms operating to increase expression at low and high glucose concentrations. On the other hand, TRIB3 as a nutrient-sensing gene could be tightly related to O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification since proteins can exhibit increased O-GlcNAc modification with both glucose deprivation and high glucose conditions (55). O-GlcNAcylation is known to affect multiple metabolic pathways and has been implicated specifically as a contributor to insulin resistance and T2DM (30, 34).

In rats high dietary fructose consumption leads to insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome (47) and has been observed to increase TRIB3 mRNA levels in adipose tissue (4). Moreover, TRIB3 mRNA is positively correlated with insulin resistance calculated by the formula homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR; Ref. 4). Adult rats that have in utero exposure to ethanol are predisposed to the development of diabetes, which is also associated with elevated TRIB3 in skeletal muscle and liver (20, 64, 65). In humans, the TRIB3 gain-of-function Q84R polymorphism is associated with insulin resistance and diabetes (41, 50), early onset T2DM, and predisposition to carotid atherosclerosis (16, 42).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that TRIB3 protein expression is increased in skeletal muscle in T2DM and that TRIB3 can impair insulin signaling, stimulation of glucose transport, and GLUT4 translocation in muscle cells. Furthermore, ambient glucose levels, both high and low glucose, regulate TRIB3 expression in muscle cells in vitro, and TRIB3 is correlated with fasting glucose in human skeletal muscle. Thus we propose that TRIB3 upregulation due to hyperglycemia can explain, at least in part, the component of insulin resistance in diabetes that is attributable to the hyperglycemic state (i.e., glucose toxicity). These observations implicate TRIB3 as a nutrient sensor that can mediate cell stress responses under conditions of both high glucose and glucose deprivation. TRIB3 induction represents a new mechanism for human insulin resistance and a potential pathway for pharmacological amelioration of insulin resistance in diabetes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-038764, DK-083562, and DK-62071 and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-055782, American Heart Association Beginning Grant-in-Aid (to X. Wu), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-0510387), and the Merit Review Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (to W. T. Garvey and J. L. Messina). We also gratefully acknowledge the support of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1 RR025777), the UAB Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30-DK56336), and the UAB Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK079626).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Cristina Lara-Castro for the information of human biopsy; and Drs. John C. Chatham and Dan Shan for skeletal muscle samples from db/db mice and technical assistance. We are also grateful for the participation of our research volunteers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreozzi F, Formoso G, Prudente S, Hribal ML, Pandolfi A, Bellacchio E, Di Silvestre S, Trischitta V, Consoli A, Sesti G. TRIB3 R84 variant is associated with impaired insulin-mediated nitric oxide production in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1355–1360, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandyopadhyay GK, Yu JG, Ofrecio J, Olefsky JM. Increased p85/55/50 expression and decreased phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase activity in insulin-resistant human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 54: 2351–2359, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron AD, Zhu JS, Zhu JH, Weldon H, Maianu L, Garvey WT. Glucosamine induces insulin resistance in vivo by affecting GLUT 4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Implications for glucose toxicity. J Clin Invest 96: 2792–2801, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi XP, Tan HW, Xing SS, Wang ZH, Tang MX, Zhang Y, Zhang W. Overexpression of TRB3 gene in adipose tissue of rats with high fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Endocr J 55: 747–752, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowers AJ, Scully S, Boylan JF. SKIP3, a novel Drosophila tribbles ortholog, is overexpressed in human tumors and is regulated by hypoxia. Oncogene 22: 2823–2835, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cravero JD, Carlson CS, Im HJ, Yammani RR, Long D, Loeser RF. Increased expression of the Akt/PKB inhibitor TRB3 in osteoarthritic chondrocytes inhibits insulin-like growth factor 1-mediated cell survival and proteoglycan synthesis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 492–500, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cushman SW, Wardzala LJ. Potential mechanism of insulin action on glucose transport in the isolated rat adipose cell. Apparent translocation of intracellular transport systems to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 255: 4758–4762, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai R, Chen R, Li H. Cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell cycle progression and cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol 34: 1749–1757, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding J, Kato S, Du K. PI3K activates negative and positive signals to regulate TRB3 expression in hepatic cells. Exp Cell Res 314: 1566–1574, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du K, Herzig S, Kulkarni RN, Montminy M. TRB3: a tribbles homolog that inhibits Akt/PKB activation by insulin in liver. Science 300: 1574–1577, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao S, Zhong X, Ben J, Zhu X, Zheng Y, Zhuang Y, Bai H, Jiang L, Chen Y, Ji Y, Chen Q. Glucose regulated protein 78 prompts scavenger receptor A-mediated secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by Raw 264.7 cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2009Mar 26 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garvey WT, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin resistance and disease. In: Bailliere's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, edited by Ferrannini E. London: Bailliere Tindall, 1994, p. 785–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garvey WT, Maianu L, Zhu JH, Brechtel-Hook G, Wallace P, Baron AD. Evidence for defects in the trafficking and translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters in skeletal muscle as a cause of human insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 101: 2377–2386, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, Hamman RF, Kolterman OG. The effect of insulin treatment on insulin secretion and insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 34: 222–234, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Matthaei S, Marshall S. Glucose and insulin co-regulate the glucose transport system in primary cultured adipocytes. A new mechanism of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 262: 189–197, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong HP, Wang ZH, Jiang H, Fang NN, Li JS, Shang YY, Zhang Y, Zhong M, Zhang W. TRIB3 functional Q84R polymorphism is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome and carotid atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care 32: 1311–1313, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grosshans J, Wieschaus E. A genetic link between morphogenesis and cell division during formation of the ventral furrow in Drosophila. Cell 101: 523–531, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie DG, Carling D. The AMP-activated protein kinase–fuel gauge of the mammalian cell? Eur J Biochem 246: 259–273, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardin DS, Dominguez JH, Garvey WT. Muscle group-specific regulation of GLUT 4 glucose transporters in control, diabetic, and insulin-treated diabetic rats. Metabolism 42: 1310–1315, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He L, Simmen FA, Mehendale HM, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Chronic ethanol intake impairs insulin signaling in rats by disrupting Akt association with the cell membrane. Role of TRB3 in inhibition of Akt/protein kinase B activation. J Biol Chem 281: 11126–11134, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegedus Z, Czibula A, Kiss-Toth E. Tribbles: a family of kinase-like proteins with potent signalling regulatory function. Cell Signal 19: 238–250, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegedus Z, Czibula A, Kiss-Toth E. Tribbles: novel regulators of cell function; evolutionary aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1632–1641, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu P, Han Z, Couvillon AD, Exton JH. Critical role of endogenous Akt/IAPs and MEK1/ERK pathways in counteracting endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death. J Biol Chem 279: 49420–49429, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iynedjian PB. Lack of evidence for a role of TRB3/NIPK as an inhibitor of PKB-mediated insulin signalling in primary hepatocytes. Biochem J 386: 113–118, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiss-Toth E, Bagstaff SM, Sung HY, Jozsa V, Dempsey C, Caunt JC, Oxley KM, Wyllie DH, Polgar T, Harte M, O'Neill LA, Qwarnstrom EE, Dower SK. Human tribbles, a protein family controlling mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. J Biol Chem 279: 42703–42708, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiss-Toth E, Wyllie DH, Holland K, Marsden L, Jozsa V, Oxley KM, Polgar T, Qwarnstrom EE, Dower SK. Functional mapping of Toll/interleukin-1 signalling networks by expression cloning. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 1405–1406, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh HJ, Arnolds DE, Fujii N, Tran TT, Rogers MJ, Jessen N, Li Y, Liew CW, Ho RC, Hirshman MF, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR, Goodyear LJ. Skeletal muscle-selective knockout of LKB1 increases insulin sensitivity, improves glucose homeostasis, and decreases TRB3. Mol Cell Biol 26: 8217–8227, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima AF, Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Cintra DE, Frederico MJ, Pinho RA, Velloso LA, De Souza CT. Acute exercise reduces insulin resistance-induced TRB3 expression and amelioration of the hepatic production of glucose in the liver of diabetic mice. J Cell Physiol 221: 92–97 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall S. Role of insulin, adipocyte hormones, and nutrient-sensing pathways in regulating fuel metabolism and energy homeostasis: a nutritional perspective of diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Sci STKE 2006: re7, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall S, Bacote V, Traxinger RR. Complete inhibition of glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system by inhibitors of mRNA synthesis. Evidence for rapid turnover of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase. J Biol Chem 266: 10155–10161, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rorth P. Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell 101: 511–522, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto M, Han S, Kitamura T, Accili D. Dual role of transcription factor FoxO1 in controlling hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest 116: 2464–2472, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayor P, Maianu L, Garvey WT. Glucose and insulin chronically regulate insulin action via different mechanisms in BC3H1 myocytes. Effects on glucose transporter gene expression. Diabetes 41: 274–285, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClain DA, Crook ED. Hexosamines and insulin resistance. Diabetes 45: 1003–1009, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson BA, Robinson KA, Buse MG. Defective Akt activation is associated with glucose- but not glucosamine-induced insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E497–E506, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J 24: 1243–1255, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto H, Latres E, Liu R, Thabet K, Murphy A, Valenzeula D, Yancopoulos GD, Stitt TN, Glass DJ, Sleeman MW. Genetic deletion of Trb3, the mammalian Drosophila tribbles homolog, displays normal hepatic insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 56: 1350–1356, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Gorgun C, Glimcher LH, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science 306: 457–461, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 313: 1137–1140, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pickavance LC, Brand CL, Wassermann K, Wilding JP. The dual PPARalpha/gamma agonist, ragaglitazar, improves insulin sensitivity and metabolic profile equally with pioglitazone in diabetic and dietary obese ZDF rats. Br J Pharmacol 144: 308–316, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prudente S, Hribal ML, Flex E, Turchi F, Morini E, De Cosmo S, Bacci S, Tassi V, Cardellini M, Lauro R, Sesti G, Dallapiccola B, Trischitta V. The functional Q84R polymorphism of mammalian Tribbles homolog TRB3 is associated with insulin resistance and related cardiovascular risk in Caucasians from Italy. Diabetes 54: 2807–2811, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prudente S, Scarpelli D, Chandalia M, Zhang YY, Morini E, Del Guerra S, Perticone F, Li R, Powers C, Andreozzi F, Marchetti P, Dallapiccola B, Abate N, Doria A, Sesti G, Trischitta V. The TRIB3 Q84R polymorphism and risk of early-onset type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 190–196, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi L, Heredia JE, Altarejos JY, Screaton R, Goebel N, Niessen S, Macleod IX, Liew CW, Kulkarni RN, Bain J, Newgard C, Nelson M, Evans RM, Yates J, Montminy M. TRB3 links the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 to lipid metabolism. Science 312: 1763–1766, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian B, Wang H, Men X, Zhang W, Cai H, Xu S, Xu Y, Ye L, Wollheim CB, Lou J. TRIB3 is implicated in glucotoxicity- and oestrogen receptor-stress-induced beta-cell apoptosis. J Endocrinol 199: 407–416, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson KA, Ball LE, Buse MG. Reduction of O-GlcNAc protein modification does not prevent insulin resistance in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E884–E890, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rorth P, Szabo K, Texido G. The level of C/EBP protein is critical for cell migration during Drosophila oogenesis and is tightly controlled by regulated degradation. Mol Cell 6: 23–30, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutledge AC, Adeli K. Fructose and the metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms. Nutr Rev 65: S13–23, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwarzer R, Dames S, Tondera D, Klippel A, Kaufmann J. TRB3 is a PI 3-kinase dependent indicator for nutrient starvation. Cell Signal 18: 899–909, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seher TC, Leptin M. Tribbles, a cell-cycle brake that coordinates proliferation and morphogenesis during Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Biol 10: 623–629, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Z, Liu J, Guo Q, Ma X, Shen L, Xu S, Gao H, Yuan X, Zhang J. Association of TRB3 gene Q84R polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese population. Endocrine 35: 414–419, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simpson F, Whitehead JP, James DE. GLUT4–at the cross roads between membrane trafficking and signal transduction. Traffic 2: 2–11, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung HY, Francis SE, Crossman DC, Kiss-Toth E. Regulation of expression and signalling modulator function of mammalian tribbles is cell-type specific. Immunol Lett 104: 171–177, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sung HY, Guan H, Czibula A, King AR, Eder K, Heath E, Suvarna SK, Dower SK, Wilson AG, Francis SE, Crossman DC, Kiss-Toth E. Human tribbles-1 controls proliferation and chemotaxis of smooth muscle cells via MAPK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 282: 18379–18387, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang M, Zhong M, Shang Y, Lin H, Deng J, Jiang H, Lu H, Zhang Y, Zhang W. Differential regulation of collagen types I and III expression in cardiac fibroblasts by AGEs through TRB3/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2924–2932, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor RP, Parker GJ, Hazel MW, Soesanto Y, Fuller W, Yazzie MJ, McClain DA. Glucose deprivation stimulates O-GlcNAc modification of proteins through up-regulation of O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem 283: 6050–6057, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q, Khayat Z, Kishi K, Ebina Y, Klip A. GLUT4 translocation by insulin in intact muscle cells: detection by a fast and quantitative assay. FEBS Lett 427: 193–197, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Q, Somwar R, Bilan PJ, Liu Z, Jin J, Woodgett JR, Klip A. Protein kinase B/Akt participates in GLUT4 translocation by insulin in L6 myoblasts. Mol Cell Biol 19: 4008–4018, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YG, Shi M, Wang T, Shi T, Wei J, Wang N, Chen XM. Signal transduction mechanism of TRB3 in rats with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 15: 2329–2335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu XLJ, Franklin JL, Messina JL, Garvey WT W. TRB 3 modulates insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle; possible role in glucose-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 56, Suppl 1: A346, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu X, Wang J, Cui X, Maianu L, Rhees B, Rosinski J, So WV, Willi SM, Osier MV, Hill HS, Page GP, Allison DB, Martin M, Garvey WT. The effect of insulin on expression of genes and biochemical pathways in human skeletal muscle. Endocrine 31: 5–17, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu J, Kim HT, Ma Y, Zhao L, Zhai L, Kokorina N, Wang P, Messina JL. Trauma and hemorrhage-induced acute hepatic insulin resistance: dominant role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Endocrinology 149: 2369–2382, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu J, Lv S, Qin Y, Shu F, Xu Y, Chen J, Xu BE, Sun X, Wu J. TRB3 interacts with CtIP and is overexpressed in certain cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1770: 273–278, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yacoub Wasef SZ, Robinson KA, Berkaw MN, Buse MG. Glucose, dexamethasone, and the unfolded protein response regulate TRB3 mRNA expression in 3T3–L1 adipocytes and L6 myotubes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E1274–E1280, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao XH, Gregoire Nyomba BL. Abnormal glucose homeostasis in adult female rat offspring after intrauterine ethanol exposure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1926–R1933, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao XH, Nyomba BL. Hepatic insulin resistance induced by prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with reduced PTEN and TRB3 acetylation in adult rat offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1797–R1806, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zenimaru Y, Takahashi S, Takahashi M, Yamada K, Iwasaki T, Hattori H, Imagawa M, Ueno M, Suzuki J, Miyamori I. Glucose deprivation accelerates VLDL receptor-mediated TG-rich lipoprotein uptake by AMPK activation in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 368: 716–722, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]