Abstract

Reduced sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase (SERCA2a) expression has been shown to play a significant role in the cardiac dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. The mechanism of SERCA2a repression is, however, not known. This study was designed to examine the effect of resveratrol (RSV), a potent activator of SIRT1, on cardiac function and SERCA2a expression in chronic type 1 diabetes. Adult male mice were injected with streptozotocin (STZ) and fed with either a regular diet or a diet enriched with RSV. STZ administration produced progressive decline in cardiac function, associated with markedly reduced SERCA2a and SIRT1 protein levels and increased collagen deposition; RSV treatment to these mice had a tremendous beneficial effect both in terms of improving SERCA2a expression and on cardiac function. In cultured cardiomyocytes, RSV restored SERCA2 promoter activity, which was otherwise highly repressed in high-glucose media. Protective effects of RSV were found to be dependent on its ability to activate Silent information regulator (SIRT) 1. In cardiomyocytes, overexpression of SIRT1 was found sufficient to activate SERCA2 promoter in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with SIRT1 antagonist, splitomycin, blocked these beneficial effects of RSV. In addition, SIRT1 knockout (+/−) mice were also found to be more sensitive to STZ-induced decline in SERCA2a mRNA. The data demonstrate that, in chronic diabetes, 1) the enzymatic activity of cardiac SIRT1 is reduced, which contributes to reduced expression of SERCA2a and 2) through activation of SIRT1, RSV enhances expression of SERCA2a and improves cardiac function.

Keywords: cardiomyocytes, high glucose, sarcoplasmic calcium adenosine triphosphatase 2 promoter

diabetes mellitus is a systemic disorder affecting every organ system. Clinical and experimental data suggest that, in addition to peripheral vascular disease, diabetes also leads to cardiomyopathy where ventricular dysfunction develops even in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis and hypertension (20, 36, and 42). Diabetic cardiomyopathy occurs in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, characterized by early onset diastolic dysfunction and late-onset systolic dysfunction. It contributes to increased incidence of heart failure in the diabetic population (42, 52).

One of the major pathological changes in diabetic cardiomyopathy is abnormal intracellular calcium homeostasis, attributed to functional alterations in multiple proteins involved in the release and uptake of calcium across both the sarcolemma and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (reviewed in Ref. 10). Among these is the drastically reduced expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA2a), which occurs in both type 1 and 2 diabetes (9, 14, 39, 59). SERCA2a is a primary cardiac isoform of calcium pump transporting calcium from cytoplasm to SR during diastolic relaxation. The importance of reduced SERCA2a expression in diabetic cardiomyopathy is also documented in studies utilizing transgenic mice and transgenic rats, where overexpression of SERCA2a alone dramatically improves severe contractile dysfunction induced by streptozotocin (STZ) (53, 55). More recently, conditional increase in SERCA 2a expression has also been shown to reverse contractile dysfunction in preexisting diabetic cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice (49). These studies collectively suggest that reduced SERCA2a expression plays a pivotal role in contractile dysfunction of the diabetic heart. The mechanism for the reduced expression of SERCA2a is not known and may likely involve several metabolic and biochemical factors (10).

Resveratrol (RSV; 3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene), a natural phytoalexin found in red grape skins, red wine, and peanuts, has been reported to exert a variety of biological effects (reviewed in Ref. 8). Through its antioxidative properties, it has been shown to prevent or slow the progression of a wide variety of illnesses, including cardiovascular diseases, brain disorders, and cancer (24, 25, 46). In short-term type 1 diabetes, RSV lowers plasma glucose and triglyceride (TG) levels (48) and improves cardiac function after ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing the anti-oxidative capacity of the heart (51). In type 2 diabetes, it prolongs survival of mice by decreasing insulin resistance and increasing mitochondrial content (8, 27). All of these RSV effects appear to be related to its ability to induce Silent information regulator (Sir 2α also known as SIRT1) activity (23, 56).

SIRT1 is the founding member of a large family of class III histone deacetylase, which is a redox-sensitive enzyme, and needs cellular NAD as a cofactor for its deacetylation reactivity (26, 28, 47). It is considered to be an important modulator of genetic stability by virtue of its ability to extend life span in yeast, flies, and worms, whereas its deletion shortens life span (23, 43). SIRT1 regulates a wide variety of cellular processes such as apoptosis/cell survival, endocrine signaling, chromatin remodeling, and gene transcription. In mice, SIRT1 is highly expressed in the embryonic heart, and its knockout results in cardiac developmental defects (13, 32, 45). Its anti-apoptosis properties have been demonstrated in cardiomyocytes where SIRT1 overexpression protected cells against oxidative damage while SIRT1 inhibition promoted cell death (1, 2). In an earlier study, we observed decreased SIRT1 protein levels in end-stage failing hearts and showed that overexpression of SIRT1 protected cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-mediated cell damage (40). More recently, we have observed beneficial effects of SIRT1 in enhancing cardiac α-myosin heavy chain (MHC) gene expression in response to fructose feeding in mice (41).

In this study, we demonstrate that reduced enzymatic activity of SIRT1 contributes to SERCA2a repression in type 1 diabetes. Our results show that RSV, through activation of SIRT1, improves SERCA2a expression and cardiac function in diabetic mice. We also show that SIRT1(+/−) knockout mice are highly sensitive to diabetes-induced decline in SERCA2a mRNA. Additionally, we show that SIRT1 acts as a transcriptional activator of SERCA2 gene expression in high glucose conditions. These results demonstrate, for the first time, that RSV acting via SIRT1 could regulate SERCA 2a expression in diabetic mice and that this effect could be achieved by simple manipulation of the diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Society for Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 86–23, revised in 1996). The use of animals in our experiments was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois, Chicago, IL. STZ (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), which produces selective necrosis of pancreatic β-cells and results in an insulin deficiency state, was used to induce type 1 diabetes. Adult male CD1 mice (18 ± 4 g) were injected with a single dose (150 mg/kg ip) of a freshly prepared STZ solution in a citrate-saline buffer (pH 4.5). This dose was chosen since it has previously shown to result in high blood glucose levels with minimal cardiotoxicity (57). Control animals were injected with citrate buffer. Before STZ injection, all mice were weighed, and nonfasting blood glucose levels were measured from the tail vein using the ACCU-CHEK Compact Plus System (Indianapolis, IN). After 4 days of STZ administration, blood glucose levels were measured, and mice with blood glucose >250 mg/dl were considered to have diabetes. Nonfasting blood glucose was taken every 4 wk thereafter to ensure continued diabetic status. Serum TG insulin levels were measured in fasted mice by using kits from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA) and Alpo Diagnostics (Salem, NH), as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Diabetic animals were randomly divided into the following two main groups: 1) an STZ group that was fed with regular diet and 2) an RSV + STZ group that was fed with a special diet enriched with RSV at 0.067%. Because diabetic mice consume ∼5 g chow/day, the administered dose of RSV is estimated to be under 100 mg·kg−1·day−1. This is, however, an overestimation of the dose, since food wastage is not included in daily diet consumption. Non-STZ-injected animals fed with RSV-enriched diet also served as a control for RSV feeding. A total of seven to nine animals comprised each group. All animals had free access to water and food and received daily change of bedding. The SIRT1(+/−) knockout mice (CD1 strain) were kindly provided by Dr. M. McBurney, University of Ottawa, Canada. Because the fertility rate of SIRT(+/−) mice was very low, both sexes of these mice were used in the study.

Echocardiography.

Mice were anaesthetized with controlled inhalation of a mixture of 1.5% isoflurane and 0.5 l/min oxygen, which has been shown to have only a minimal cardiac depressive effect (44). To minimize any potential depressive effect on left ventricle function from the variable degree of anesthesia, heart rate was also monitored and kept at constant around 480 beats/min throughout the Echo study. Animals were placed on a thermally controlled foam pad to maintain body temperature between 35 and 38°C throughout the recordings. Transthoracic M-mode echocardiography was performed with a Siemens ACUSON Sequoia 256 imaging system (Siemens) using a 13-MHz broadband transducer and an echocardiography coupling gel to maximize contact between the transducer and the chest. M-mode recordings of the LV were obtained in the two-dimensional parasternal long-axis and short-axis imaging plane in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography, using as a guide the level of the papillary muscle. All images were recorded at the lowest allowable depth setting and sector width. Images were digitally recorded on a magneto-optical disk. Left ventricle end diastolic diameter (LVEDd) and end systolic diameter (LVESd) were measured off-line according to standard procedures, by an experienced echocardiographer blinded to the experimental protocol. Three consecutive cardiac cycles were measured and averaged to minimize the effects of noise and respiratory variation. Mean fractional shortening (FS in %) was calculated by a widely used formula: FS (%) = [(LVEDd - LVESd)/LVEDd] × 100.

Preparation of protein lysate.

For Western analysis, frozen heart tissue (50 mg) was homogenized in 1.5 ml lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2 μM leupeptin, 1 mM AEBSF, 1 mM aprotinin, and 400 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride] at 8,000 rpm. The homogenate was centrifuged at 0°C at 14,000 g, the supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Aliquots of tissue lysate were stored at −80°C.

Western analysis.

Proteins (30–100 μg) were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were blocked with 10% milk and hybridized overnight at 4°C with anti-SERCA2a (1:10,000; a gift from Dr. Periasamy, Ohio State University), anti-SIRT1 (1:1,000; Upstate), and anti-β-actin (1:1,000; Santa Cruz) antibodies. Membranes were washed with 1× PBS-Tween and hybridized with appropriate secondary antibody (1:2,000) in 5% milk. After washing, the signal was developed using chemiluminescence reagent (Santa Cruz) and detected by autoradiography.

SIRT1 activity assay.

SIRT1 deacetylase activity was determined using a SIRT1 Fluorimetric Activity Assay/Drug Discovery Kit (AK-555; BIOMOL International) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, mouse hearts of various groups or cardiomyocytes grown in different glucose media were lysed by RIPA buffer. Equal amounts of proteins (300 μg) were used for measuring SIRT1 deacetylase activity. For this, endogenous SIRT1 was immunoprecipitated and then incubated in deacetylase buffer with the 25 μM of acetylated p53 substrate and 0.1 mM NAD for 1 h at 37°C, and SIRT1 activity was measured per instructions.

Mason-trichrome staining for cardiac fibrosis.

For a subset of hearts, tissue samples were obtained from the apical region, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, mounted on glass slides, and stained with Masson's trichrome using the Accustain Trichrome Stain Kit (Sigma Chemicals) per instruction. Photomicrographs were obtained using Zeiss Axiophot microscopes. These were then counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) using standard protocols. Images were viewed on a Nikon microscope with an MTI 3CCD digital camera at ×100 magnification. Digitally acquired images were analyzed with Image Pro Plus V3.0 by an examiner blinded to whether or not the heart was normal, diabetic, or received RSV treatment. Myocardial collagen content was assessed with the use of a software filter set to capture the blue-stained collagen. The number of pixels included in this color range was divided by the total number of pixels in particular visual fields. Ten optical fields per slide were analyzed and then averaged.

Cell culture and transfection.

Primary cultures of cardiac myocytes were prepared from 2-day-old neonatal rat hearts as described previously (19). Myocytes were initially grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 5 mg/ml each of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitogen) for 48 h. Cells were then maintained in growth media containing normal glucose (5.5 mM) or high glucose (33 mM) for appropriate periods of time. For promoter/reporter gene analysis, cells were transfected with various plasmids using Tfx-20 reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). After 48 h of transfection, cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted and analyzed for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) mRNA and β-galactosidase (β-gal) mRNA by real-time PCR. The following plasmids were used for transfection analysis: SERCA 2/CAT reporter plasmid containing −1,800 bp of rabbit SERCA2 gene promoter. 5′-Deletion mutants in this plasmid were created by PCR and confirmed by sequencing. Expression plasmids encoding wild-type (WT) SIRT1 or H355A SIRT1 mutant were also used.

RNA analysis.

Cardiac total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Northern blot analysis was performed as described earlier with random-primed radiolabeled SERCA2a or β-actin cDNA probes (19). Real-Time PCR primers for mouse SERCA2a, CAT, β-gal, and β-actin were designed using Real-Time PCR Primer Design (//www.genscript.com/ssl-bin/app/primer), and the sequences are available upon request. Real-time PCR analysis was performed essentially as described previously (21). Briefly, 2.5 μg of DNase-digested total RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and random hexamers. For 20 μl PCR, 5 ng of cDNA template were mixed with primers to a final concentration of 200 nM and 10 μl of Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City). In a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), amplification was carried out by first incubating the reaction mix at 95° for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95° for 20 s and 60° for 30 s. For quality control purposes, at the end of each run, dissociation curves were generated by incubating the reactions at 95° for 15 s, 60° for 1 min, 95° for 15 s, and 60° for 15 s. All primer pairs used in the study were free of primer dimer artifact. Expression ratios were calculated by the ΔΔCT method, where CT is cycle threshold, using β-actin as reference gene.

Scanning densitometry and statistical analysis.

Autoradiograms were scanned using Scion Image for Windows analysis software, based on NIH image for Macintosh by Wayne Rasband (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). Signal intensity was adjusted for background density of the blot. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical difference among groups was determined using either Student's t-test for two groups or one-way ANOVA for more than two groups.

RESULTS

Survival and animal characteristics.

In our study, single injection of STZ (150 mg/kg ip) to adult male mice resulted in high blood glucose levels (>250 mg/dl) in 80% of animals. Blood glucose levels remained in the range of 85–135 mg/dl in vehicle-injected control animals and in animals before STZ injection (Table 1). Over time, STZ-injected hyperglycemic animals (STZ group) developed symptoms of severe diabetes characterized by polyurea, polydypsia, and poor body weight gain despite almost double food consumption compared with control animals. Figure 1B shows that 33% of these diabetic mice died before reaching the end of study (12 wk), whereas all animals in the control group survived. When RSV-enriched diet was fed to the STZ group of animals (STZ + RSV), we observed reduced mortality rate (of only 10%) in this group of animals. RSV treatment had no significant effect on blood glucose levels over the 12-wk period, although it did produce a transient drop of 17% that was noted during the initial 4-wk period compared with STZ-injected animals. The blood glucose levels in the STZ and RSV + STZ groups of animals remained threefold higher than those of control animals (Table 1). In a previous study, some of the beneficial effects of RSV have been ascribed to its insulin-like blood glucose-lowering effect of nearly 22% in short-term diabetes of 2 wk compared with STZ-injected rats (48). Our data suggest that the blood glucose-lowering ability of RSV is only short-term in type 1 diabetes. We also analyzed the fasting serum levels of insulin and TGs in different groups of animals. Data presented in Table 1 show that STZ caused reduction in serum insulin and increased serum TGs. These changes were intensified with diabetes progression. RSV treatment had no significant improvement in these parameters, although, compared with the nontreated STZ group, a drop in serum TG level was observed in the 1-mo group, but, because of high variability among individual animals, this difference was not found to be statistically significant. Likewise, these parameters were not affected in SIRT1(+/−) mice under basal conditions. STZ administration also produced comparable changes in serum insulin and TGs in SIRT1(+/−) and WT mice (Table 2).

Table 1.

Animal characteristics

|

Time 0 |

1 Month |

3 Months |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Control | STZ | RSV + STZ | Control | STZ | STZ + RSV | Control | STZ | RSV + STZ |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 110 ± 25 | 95 ± 20 | 105 ± 18 | 112 ± 10 | 402 ± 30* | 335 ± 25*† | 120 ± 15 | 400 ± 60* | 390 ± 40* |

| Serum insulin, ng/ml | 1.29 ± 0.14 | 0.32 ± 0.08* | 0.42 ± 0.15* | 1.32 ± 0.28 | 0.20 ± 0.09* | 0.19 ± 0.08* | |||

| Serum TG, mg/dl | 28 ± 3.8 | 60 ± 6.2* | 45 ± 14.8* | 32 ± 3.5 | 95 ± 14.9* | 85 ± 11.6* | |||

| Body wt, g | 18.6 ± 1.1 | 20.1 ± 2.0 | 19.5 ± 1.5 | 33.7 ± 3.9 | 23.1 ± 3.5* | 28.2 ± 3.5* | 46.4 ± 3.1 | 31.3 ± 1.1* | 32.6 ± 2.9* |

| Heart wt, mg | 143 ± 4.5 | 99 ± 3.3 | 118 ± 2.9 | 193 ± 5.0 | 190 ± 6.7 | 160 ± 3.2*† | |||

| HW/BW, 10−3 | 4.24 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.08 | 4.18 ± 0.12 | 4.2 ± 0.09 | 8.6 ± 0.18* | 5.0 ± 0.09† | |||

Values are means ± SD of at least 8 animals in each group. STZ, streptozotocin-injected animals; RSV + STZ, animals fed with resveratrol-enriched diet starting 4 days following STZ; TG, triglyceride. HW/BW, heart weight-to-body weight ratio.

Significant (P < 0.05) difference from control animals

and STZ-injected animals.

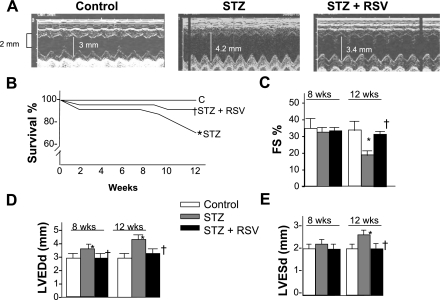

Fig. 1.

Survival and echocardiographic measurements. A: representative M-mode echocardiograms. B: diabetes progression was associated with reduced survival rate. C–E: resveratrol (RSV) treatment significantly improved survival rate. Echocardiographic measurements revealed a progressive decline in cardiac function following streptozotocin (STZ) injection with an early (8 wk) increase in left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDd), followed by a further increase in left ventricle (LV) diameters and reduced fractional shortening (FS) in the 3 mo group. Note reduced diameters and improvement of STZ-induced decline in FS following RSV treatment. LVESd, left ventricular end systolic diameter; STZ + RSV, RSV-treated diabetic group. Values are means ± SD of 8–10 animals in each group, for survival, n = 20. P < 0.05 compared with control group (*) and compared with STZ group (†).

Table 2.

Animal characteristics of SIRT1(+/−) mice

| WT |

SIRT1(+/−) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Control | STZ | Control | STZ |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 112 ± 10 | 402 ± 30* | 120 ± 15 | 400 ± 60* |

| Serum insulin, ng/ml | 1.32 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.1* | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 0.22 ± 0.04* |

| Serum TG, mg /dl | 29.5 ± 4.3 | 66 ± 6.8* | 32 ± 3.5 | 79 ± 8.9* |

| Body wt, g | 33.7 ± 3.9 | 23.1 ± 3.5* | 29.4 ± 3.1 | 20.3 ± 1.1* |

| Heart wt, mg | 144.9 ± 4.5 | 103.9 ± 5.3 | 131.7 ± 6.0 | 154.28 ± 8.7 |

| HW/BW, 10−3 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.18 | 4.48 ± 0.19 | 7.6 ± 0.18* |

Values are means ± SD of at least 6 animals in each group. SIRT1(+/−), Silent information regulator 1 knockout; WT, wild type; STZ, animals following 1 mo of streptozotocin injection.

Significant (P < 0.05) difference from non-STZ-injected control animals.

We observed poor body weight gain in all STZ-injected animals irrespective of RSV treatment, both in the 1 and 3 mo group of animals. After 1 mo of STZ, heart weight-to-body weight ratios were increased by 70% in SIRT1(+/−) mice, whereas they remained unchanged in WT animals or control animals (Tables 1 and 2). A twofold increase in heart weight-to-body weight ratios was noted in the 3 mo STZ group. RSV treatment to diabetic mice lowered this ratio significantly to 19% above nontreated controls (Table 1).

Left ventricle function evaluation by echocardiographgy.

To analyze if in vivo basal (nonchallenged) cardiac function improves with RSV treatment in long-term diabetes, we performed echocardiography in the three groups of animals at the start of the study and every month thereafter. There were no significant differences in baseline functional parameters initially and also after 1 mo of the study period (data not shown). After 2 mo, fractional shortening and systolic diameter remained comparable in the three groups; however, a small but significant increase (17%) in diastolic diameters was noted in the STZ group of animals compared with baseline values and respective control animals (Fig. 1, C–E). After 3 mo, we observed greater left ventricular diameters and reduced cardiac function in the STZ group of animals, consisting of significantly increased systolic (22%) and diastolic (28%) diameters and marked reduction in fractional shortening (46%) compared with those of control animals. RSV treatment for 3 mo (STZ + RSV group) resultd in tremendous improvement of all functional parameters to the extent that cardiac function became comparable to those obtained before induction of diabetes and those of their age-matched controls. These included significant reduction in systolic diameters (76%), diastolic diameters (87%), and improved fractional shortening (170%) compared with those of STZ animals. The results indicate that RSV is capable of blocking the diabetes-induced decline in cardiac function.

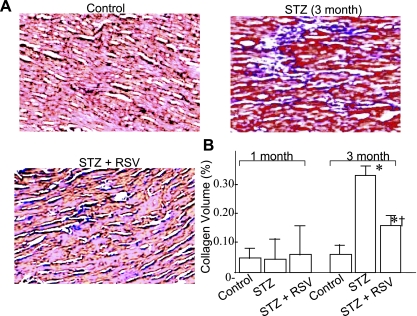

RSV treatment reduces fibrosis in the diabetic myocardium.

Myofibrosis occurs in diabetic cardiomyopathy (42). In an earlier study, RSV was shown to reduce basal and growth factor-stimulated cardiac fibroblast cell proliferation and their differentiation to myofibroblast phenotype as well as to inhibit extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation (37). To analyze if RSV modifies collagen deposition in vivo in the diabetic myocardium, we performed Trichrom Masson staining on the 5- to 10-μm sections of the paraffin-embedded apical region of four hearts from each group, followed by H & E staining. Analysis of these sections indicated no change in collagen deposition in the 1 mo STZ group, a sevenfold increase in the 3 mo STZ group, and only a twofold increase in the RSV-treated (RSV + STZ) group of animals (Fig. 2). RSV treatment thus showed evidence of inhibiting or modifying the development of myofibrosis in the diabetic hearts.

Fig. 2.

A: representative micrographs (×40) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections obtained from LV apex of control and 3 mo untreated (STZ) and RSV-treated (STZ + RSV) diabetic animals. Sections (5 μm) were stained with trichrome-masson and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). B: collagen volume fraction (CVF) analysis in different groups of animals after 1 and 3 mo experimental period. CVF was calculated by measuring the area of blue-stained collagen fibers in the interstitial space and expressed as %total area examined. A minimum of 10 different areas were examined in four different hearts of each group. P < 0.05 compared with *control group and †STZ group.

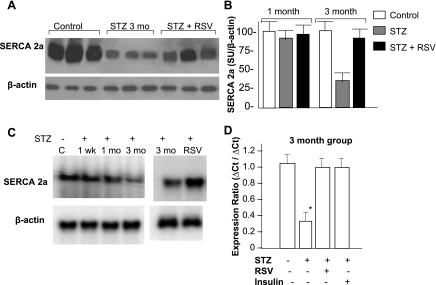

RSV treatment improves SERCA2a expression.

SERCA2a is involved in the uptake of calcium across SR and plays a critical role in maintaining calcium homeostasis and, subsequently, contractility of the myocardium. Its expression is known to be reduced in diabetic cardiomyopathy. To test how restoration of cardiac function by RSV relates to SERCA2a expression, we measured cardiac SERCA2a levels (protein and mRNA) in different groups of animals. At the protein level, we found no significant difference between those of the 1 mo STZ-injected animals and control animals, but nearly 70% reduction in SERCA2a expression in the 3 mo STZ-injected animals (Fig. 3, A and B). We next analyzed time-related changes in SERCA2a mRNA following STZ injection and found no change in 1 wk, ∼15% reduction in 1 mo, and 80% reduction in 3 mo compared with those of control animals (Fig. 3C). To evaluate the direct role of hyperglycemia in SERCA2a expression, we also measured SERCA2a mRNA levels in STZ-injected but nonhyperglycemic animals (which comprised only 20% of all STZ-injected animals) and found them to be comparable to those of control hearts (data not shown), suggesting that the reduced SERCA2a expression is a direct effect of hyperglycemia from insulin deficiency by STZ and not from its alleged cardiotoxicity. This was further document by daily administration of insulin (Lantus insulin, 2 IU/kg sc) for 3 mo to STZ-injected hyperglycemic animals, which totally prevented the decline in SERCA2a mRNA levels (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, RSV treatment for 3 mo also restored SERCA2a protein levels to ∼80% of control values and brought SERCA2a mRNA to control levels (Fig. 3, A–D). The observed improvement from RSV in SERCA2a expression was similar to that resulting from insulin treatment (Fig. 3D). Collectively, our data strongly demonstrate beneficial effects of RSV on SERCA2a expression.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase (SERCA) 2a expression. A: Western analysis; representative radiograms obtained from the cardiac tissue lysate of 3 mo control, diabetic (STZ), and RSV-treated diabetic (STZ + RSV) groups of animals. β-Actin was used as a loading control. B: semiquantitative analysis of SERCA2a levels after 1 and 3 mo of STZ injection. Band intensity measurements were done using Scion software. In each panel, the intensity of a given band was normalized to the intensity of the loading control (β-actin) of the respective band and expressed as means ± SD of 4–6 hearts analyzed in three separate experiments. C: Northern analysis of time course of changes in SERCA2a mRNA following 1 wk, 1 mo, and 3 mo of STZ injection and 3 mo following RSV treatment. Each lane represents pooled RNA of 3–5 hearts of each group. β-Actin was used as a loading control. D: real-time PCR analysis of total RNA from indicated group of animals. Expression ratios were calculated using the ΔΔCT method, where CT is cycle threshold, and β-actin as reference. Each bar represents mean values and SD of 5 hearts of each group. *P < 0.05 compared with the control group.

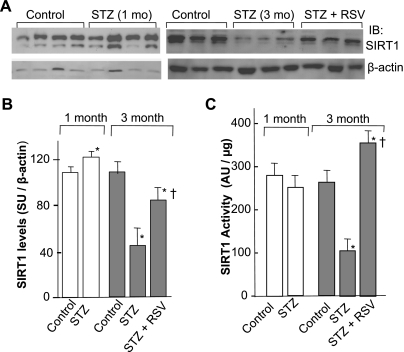

SIRT1 expression and activity in diabetic hearts.

RSV is a potent activator of SIRT1, and a recent report has shown that SIRT1 gain of function in transgenic mice increases energy efficiency and improves glucose metabolism (8). Because diabetic cardiomyopathy is a metabolic disorder, we asked whether SIRT1 expression and activity is affected in the progression of diabetes. For this, cardiac SIRT1 protein levels were measured after 1 and 3 mo of STZ administration. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Quantitative analysis of the normalized SIRT1 levels relative to those of control hearts showed a significant induction (30%) of SIRT1 protein levels following 1 mo of STZ administration; however, after 3 mo of STZ, the levels of SIRT1 were found to be reduced by 60% (Fig. 4, A and B). To assess how differential SIRT1 protein levels relate to its activity in diabetic hearts, we immunoprecipitated endogenous SIRT1 using equal amounts of cardiac proteins of different groups of hearts, and deacetylase activity was measured by utilizing acetylated p53 as a substrate. As shown in Fig. 4C, the cardiac SIRT1 activity was reduced by 20% in the 1 mo STZ group relative to respective controls. A drastic threefold reduction of SIRT1 activity was later observed in the 3 mo STZ group. We also observed that RSV treatment for 3 mo not only blocked any decline in SIRT1 activity but in fact stimulated it by 40% above those observed in control animals (Fig. 4C). These findings collectively demonstrate that cardiac SIRT1 expression and activity is sensitive to high blood glucose levels; the expression initially increases but later declines, whereas the activity is severely compromised only in prolonged diabetic hearts. The decline in SIRT1 activity is associated with reduced level of SERCA2a and cardiac dysfunction in 3 mo diabetic hearts.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of Silent information regulator (SIRT) 1 expression and activity. A: representative radiograms of SIRT1 expression by Western blot, using 50 μg of total cardiac proteins of different groups of animals as indicated. B: quantification of SIRT1 levels by densitometry. Band intensity measurements were done using Scion software. In each panel, the intensity of a given band was normalized to the intensity of the loading control of the respective band and expressed as means ± SD of 4–6 hearts analyzed in three separate experiments. C: SIRT1 activity measurements. Endogenous SIRT1 was immunoprecipitated using 100 μg of total protein from the indicated treatment group hearts and subjected to deacetylase assay. Values are means ± SD of 3 hearts of each group. *P < 0.05 compared with the control group and compared with the STZ group (†).

RSV treatment induces SERCA2a promoter activity in a SIRT1-dependent manner.

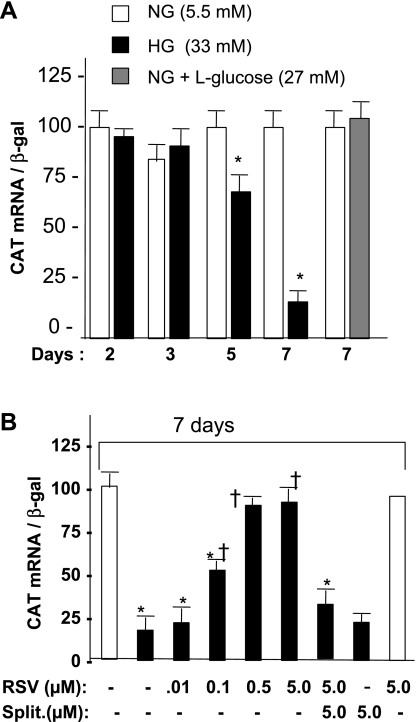

Knowing that RSV treatment regulates SERCA2a mRNA level, we next asked whether this effect could be mediated at the transcription level. For this purpose, a series of transient transfection experiments was carried out using primary cultures of cardiomyocytes grown in high-glucose (33 mM) media and compared with those grown in normal glucose (5.5 mM). Data in Fig. 5A demonstrate that cells incubated in high glucose media for 5 and 7 days showed 40 and 80% decline in SERCA2 promoter activity, respectively, compared with cells grown in normal glucose, whereas inclusion of l-glucose or of mannitol (data not shown) in the media had no effect on the promoter activity. Most notably, treatment of cells with RSV under high glucose conditions restored the SERCA2 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner with a peak effect observed at 0.5 and 5 μM concentrations. RSV (5 μM) had no effect on promoter activity when cells were grown in normal glucose media (Fig. 5B). The results suggest that RSV has the potential to enhance SERCA promoter activity in high glucose conditions.

Fig. 5.

Effect of high glucose and RSV treatment on SERCA2 promoter activity in cardiomyocytes. A: time-course response of SERCA2 promoter activity in high glucose. B: SERCA2 promoter activity in the presence of indicated doses of RSV and splitomicin (split). Primary cultures of cardiomyocytes obtained from neonatal rat heart were grown in media containing either normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG), incubated for the indicated time period, and transfected with 4.0 μg of SERCA 2 promoter/chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter construct containing 1.8 kb upstream sequences along with 1.0 μg β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression plasmid. After 48 h, total RNA was extracted, and promoter activity was measured by quantifying CAT mRNA by real-time PCR using β-gal as a reference. RSV treatment with or without splitomicin was given every 48 h in the indicated doses starting 48 h before transfection. Each bar represents the mean value of CAT mRNA normalized to β-gal mRNA ± SD, using a minimum of 5 experiments performed in duplicate. P < 0.05 compared with normal glucose control (*) and compared with high glucose control (†).

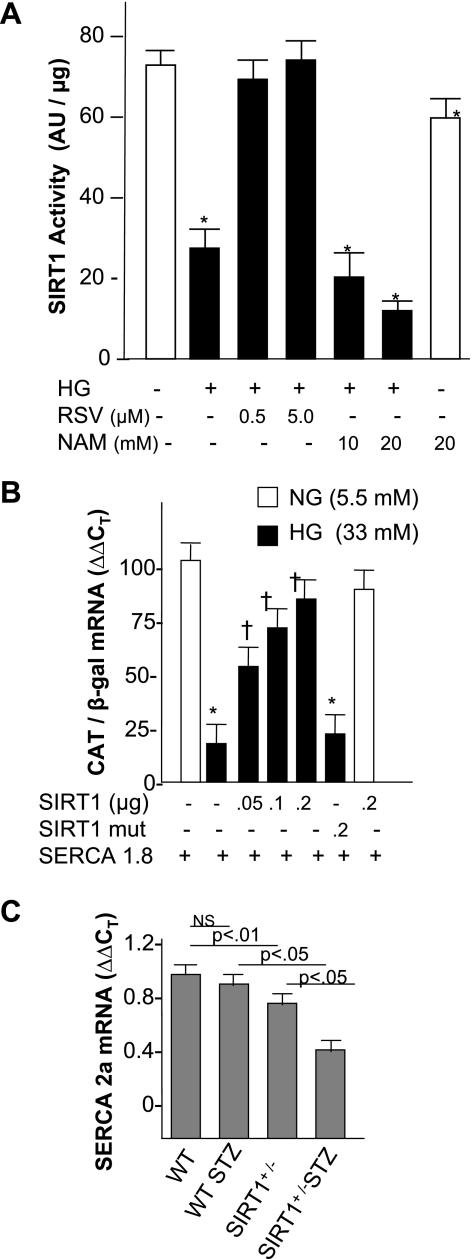

To analyze the participation of SIRT1 in this response, we measured SIRT1 deacetylase activity under various conditions. As shown in Fig. 6A, incubation of cardiomyocytes in high glucose resulted in ∼60% decline in the SIRT1 activity. Treatment of cells with RSV removed this repression, whereas treatment with a SIRT1 antagonist, nicotinamide, led to a further decline in SIRT1 activity in a dose-dependent manner. In normal glucose, nicotinamide produced significantly less repression in SIRT1 activity, suggesting that high glucose medium is inducing other factors that are also contributing to repressed SIRT1 activity. We also observed that RSV treatment failed to restore SERCA2 promoter activity when cells were pretreated with an inhibitor of SIRT1, splitomicin, whereas splitomycin per se had no effect on promoter activity (Fig. 5B). These results together suggest that SIRT1 activity is necessary for the RSV response. To test whether SIRT1 is sufficient to restore SERCA2 promoter activity, cells were grown in high glucose media for 7 days, SIRT1 expression plasmid was cotransfected with SERCA promoter/CAT reporter construct, and CAT mRNA was measured after 48 h. Overexpression of SIRT1 alone improved CAT expression in a dose-dependent manner, but the SIRT1 mutant showed no improvement. SIRT1 had no effect on the promoter activity in low glucose conditions (Fig. 6B). To obtain evidence of SIRT1 involvement in an in vivo model of diabetes, we measured basal levels of SERCA2a mRNA in SIRT1(+/−) knockout mice and also after 1 mo of STZ injection. We found nearly 20% reduction in the basal levels of SERCA2a mRNA in SIRT(+/−) mice compared with those of WT mice. STZ injection resulted in an almost 60% decline in the SERCA2a mRNA levels in SIRT1(+/−) mice than it did in WT mice (Fig. 6C). The data collectively suggest that SIRT1 is an in vivo regulator of SERCA2a expression both under nonstressed conditions and in hyperglycemic conditions.

Fig. 6.

Role of SIRT1 in high glucose response of SERCA2a expression. A: SIRT1 activity in cardiomyocytes in high glucose media. Cardiomyocytes were cultured under normal glucose (open bar) or high glucose media, alone or in presence of SIRT1 stimulant (RSV), or in the presence of the inhibitor nicotinamide (NAM). B: SERCA2 promoter activity in the presence of SIRT1 expression plasmid in high glucose. Following 7 days of incubation of cells in normal or high glucose media, cells were transfected with 4.0 μg of SERCA 2 promoter along with 1 μg of CMV β-gal cDNA and either wild-type (WT) or mutant SIRT1 expression plasmid in the indicated concentrations, and CAT mRNA was quantified after 48 h by real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean value ± SD of a minimum of 3–5 experiments performed in duplicate. P < 0.05 compared with normal glucose control (*) and compared with high glucose control (†). C: SERCA2a mRNA in WT and SIRT1 knockout (+/−) mice and following 1 mo of STZ injection to WT and SIRT1 (+/−) mice. Hearts were harvested processed for SERCA2a mRNA analysis by real-time PCR using β-actin as reference (n = 4 in each group).

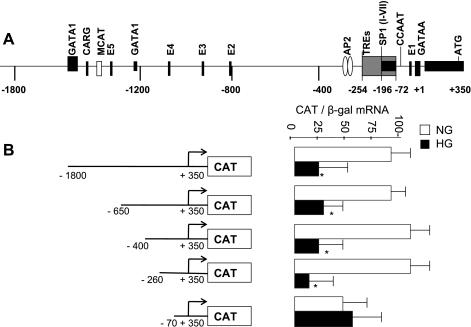

To map the minimum responsive region of SERCA2 promoter to high glucose, a series of deletion mutants was created in the 5′-region of SERCA2 promoter. We found sequences between 70 and 260 bp upstream of the transcription start site to be mediating the high glucose-induced repressive effect (Fig. 7). This region is earlier shown to contain several SP1 binding sites and thyroid hormone responsive elements (5, 58).

Fig. 7.

Deletion analysis of SERCA2 promoter. A: schematic representation of SERCA2 showing various regulatory elements within 1,800-bp upstream region of rabbit promoter as described by Baker et al. (5). B: functional analysis of SERCA2 promoter in cardiomyocytes grown in normal glucose or high glucose. After 7 days, cells were transfected with various deletion mutants of SERCA promoter (shown on left), and CAT mRNA was measured by QPCR as described in materials and methods. Each bar represents the mean value ± SD of CAT mRNA normalized to β-gal mRNA of a minimum of 3 experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05 compared with normal glucose control.

DISCUSSION

Cardiomyopathy is a prevalent cause of death in patients with diabetes. Efforts continue to understand the molecular basis of this process and to improve or protect the heart from this complication. Previous studies have shown that reduced expression of SERCA2a plays a significant role in ensuing contractile dysfunction of diabetic hearts. In this study, we provide the following lines of evidence to support a role of SIRT1 in the regulation of SERCA 2 gene expression in high-glucose conditions: 1) chronic diabetes results in reduced enzymatic activity of cardiac SIRT1, which correlates with reduced SERCA 2a mRNA levels and cardiac dysfunction; 2) in cardiomyocytes, when cultured in high glucose media, SERCA2 promoter activity is reduced, and overexpression of SIRT1 alone was found sufficient to prevent this decline; 3) RSV treatment to diabetic mice, which induces cardiac SIRT1 activity by twofold, prevents the STZ-induced decline in SERCA2a mRNA and improves cardiac function; 4) RSV treatment also improves SERCA2 promoter activity in cardiomyocytes cultured in high glucose media, and this response is blocked by an inhibitor of SIRT1, splitomycin; and 5) SIRT1(+/−) mice demonstrate lower basal levels of SERCA2a mRNA, which show rapid reduction following STZ administration. Based on these findings, we propose that RSV, by activating SIRT1, promotes SERCA2a gene expression and improves cardiac function in chronic diabetic animals.

The reduced contractility of diabetic hearts has been shown to correlate directly with the impaired SR function and SERCA2a activity. Several studies have shown that the activity and the expression levels of SERCA2a are reduced in diabetic cardiomyopathy (9, 14, 39, 59). We also observed significant reduction in SERCA2a mRNA and protein levels under prolonged diabetic conditions. More importantly, RSV treatment to diabetic animals for 3 mo resulted in restoration of SERCA2a expression and improved cardiac diameters, and that correlated with normalized left ventricular fractional shortening. Consistent with our results, a previous study showed that increased SERCA2a expression by an adenoviral vector-mediated gene delivery improves contractile function of hemodynamic-overloaded failing hearts (34). Beneficial effects of RSV treatment have also been reported in short-term type 1 diabetes (2 wk after STZ injection), which is related to its insulin-like activity (48) and its ability to induce anti-oxidant Mn superoxide dismutase (51), whereas, in type 2 diabetes, it is shown to improve insulin sensitivity and inhibit glucose-induced insulin secretion from rat pancreatic islets (27, 50). In our study with advanced type 1 diabetes (3 mo following STZ injection), we found that RSV had no effect on serum TGs or insulin levels or blood glucose levels, suggesting that beneficial effects of RSV on SERCA2 gene expression are independent of its insulin-related effects but rather found dependent on its ability to induce cardiac SIRT1 activity. In 1 mo STZ-treated hearts, we observed higher SIRT1 expression levels with no difference in its activity. We speculate that increased expression level of SIRT1 must represent an adaptive response of the heart to prevent a decline in SIRT1 activity. This argument is in line with our echocardiographic data that show compensated heart in 1 mo STZ animals in terms of preserved cardiac function and unaltered SERCA2a expression in spite of high blood-glucose levels. In addition, two recent studies have also shown that cardiac SIRT1 expression is increased during compensatory cardiac hypertrophy of spontaneously diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats and in spontaneously hypertensive rats (29, 54). Based on these reports and findings of current investigations, we propose that a drop in cardiac expression of SIRT1 and subsequent loss of its deacetylase activity in advanced diabetes is likely the result of failure of this compensatory response, which then results in reduced SERCA2a expression and cardiac dysfunction.

In this study, we have provided several lines of evidence that support a role of SIRT1 in SERCA2a gene expression: 1) in both in vitro and in vivo experiments, SIRT1 was found to be sensitive to high glucose levels; 2) in vivo, in spite of persistent hyperglycemia, reduced expression of SERCA2a was observed only when there was a drastic reduction in SIRT1 activity; 3) haploinsufficiency of SIRT1 in heterozygous mice resulted in a reduced basal level of SERCA2a mRNA and an earlier reduction in SERCA2a mRNA following STZ challenge; and 4) SIRT1 overexpression alone was found sufficient to restore SERCA2 promoter activity in cardiomyocytes cultured in high glucose media. Thus our study suggests that SIRT1 is cardioprotective and its reduced activity contributes to reduced expression of SERCA2a in diabetic cardiomyopathy. It should be noted, however, that functional benefits provided by SIRT1 may not be just limited to the activation of SERCA2 gene, since we have recently shown that SIRT1 also regulates the transcriptional activity of α-MHC gene promoter (41). Because the expression of both α-MHC and SERCA2a is reduced in hemodynamic overloaded hearts and in diabetic failing hearts, and we found reduced SIRT1 activity in both of these conditions (this study and Ref. 40), it is likely that SIRT1 may utilize a common mechanism for the transcription regulation of both genes.

Data presented in our study show that SIRT1 could directly activate SERCA2 promoter in cultured cardiomyocytes under high glucose conditions. Because glucose responsiveness was found limited to the proximal region (−284 to −7 bp) of SERCA2 promoter, we speculate that deacetylation of specific transcription factors interacting within this region may be involved. In this regard, several recent studies have shown that SIRT1 could modify the activity of a variety of transcription factors and cofactors and regulate expression of several genes in multiple cell systems. For example, in vascular smooth muscle cells, it represses angiotensin receptor gene involving SP1 binding sites (35); in skeletal muscle cells, it participates in glucocorticoid-mediated activation of the uncoupling protein-3 (3); and, in human chondrocytes, it upregulates collagen 2 (α1) promoter in a Sox9-dependent fashion (16). It has also been demonstrated to inhibit glucose-induced activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene promoter by interfering with c-jun DNA-binding activity (22). Other transcription factors that show sensitivity to SIRT1 include FOXOs, p53, PGC1a, as well as nuclear receptors such as estrogen receptors, androgen receptors, and liver X receptors (4, 17). Thus, by controlling gene transcription, SIRT1 is able to regulate widely diverse biological processes such as oxidative stress, cholesterol homeostasis, circadian rhythms, and metabolism. Data presented in the current study support an additional role of SIRT1 in controlling cardiac contractility by regulating SERCA2 promoter activity. Our functional analysis of rabbit SERCA2 promoter revealed a role of a −260 to −70 bp region in high glucose-induced repression of its promoter activity. Upon sequence analysis, we found the presence of multiple binding sites for SP1 and thyroid hormone receptors within the glucose-responsive region. Previous studies have shown that SP1 confers muscle-specific expression of SERCA2 (5) while thyroid hormone acts as a positive regulator of SERCA2a expression (58). Currently, we are in the process of delineating the transcription factors that are sensitive to high glucose and are targeted by SIRT1 in regulating SERCA2a expression.

In summary, our data presented here demonstrate that a natural substance (RSV) is capable of reversing the complications of diabetic cardiomyopathy by activiating SIRT1-dependent transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, thereby restoring SERCA2a expression and improving cardiac function. Our finding has a wider implication because impaired SR function and decreased SERCA2a levels are not just limited to diabetic cardiomyopathy but also play a role in end-stage heart failure due to ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy (30, 33, 34), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (15, 18), and aging hearts (31), and RSV treatment has been found to be beneficial under these conditions (7, 11, 12, 38). Our study may have profound implications in the treatment of heart failure from diabetes and other cardiac disorders and suggests that diets rich in RSV will prove beneficial in this disease.

GRANTS

This study was partially funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-77788, HL-83423, and HL-64140 and by the Christ Hospital Med-fund.

DISCLOSURES

None

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. R. A. Arcilla for the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank D. W. Sobczak for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcendor RR, Kirshenbaum LA, Imai S, Sadoshima J. Sir2α, a longevity factor and a class III histone deacetylase, is an essential endogenous inhibitor of apoptosis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 95: 971–980, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcendor RR, Gao S, Zhai P, Zablocki D, Holle E, Yu X, Tian B, Wagner T, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res 100: 1512–1521, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amat R, Solanes G, Giralt M, Villarroya F. SIRT1 is involved in glucocorticoid-mediated control of uncoupling protein-3 gene transcription. J Biol Chem 282: 34066–34076, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Schibler U. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell 134: 317–328, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DL, Dave V, Reed T, Periasamy M. Multiple Sp1 binding sites in the slow twitch muscle sacoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase gene promoter are required for expression on Sol8 muscle cells. J Biol Chem 271: 5921–5928, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banks AS, Kon N, Knight C, Matsumoto M, Gutiérrez-Juárez R, Rossetti L, Gu W, Accili D. SirT1 gain of function increases energy efficiency and prevents diabetes in mice. Cell Metab 8: 333–341, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barger JL, Kayo T, Vann JM, Arias EB, Wang J, Hacker TA, Wang Y, Raederstorff D, Morrow JD, Leeuwenburgh C, Allison DB, Saupe KW, Cartee GD, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS ONE 3: e2264, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 444: 337–342, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belke DD, Swanson EA, Dillmann WH. Decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum activity and contractility in diabetic db/db mouse heart. Diabetes 53: 3201–3208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 115: 3213–3223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burstein B, Maguy A, Clément R, Gosselin H, Poulin F, Ethier N, Tardif JC, Hébert TE, Calderone A, Nattel S. Effects of resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) treatment on cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323: 916–923, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan AY, Dolinsky VW, Soltys CL, Viollet B, Baksh S, Light PE, Dyck JR. Resveratrol inhibits cardiac hypertrophy via AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt. J Biol Chem 283: 24194–24201, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10794–10799, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi KM, Zhong Y, Hoit BD, Grupp IL, Hahn M, Dilly KW, Guatimosin S, Lederer WJ, Matlib MA. Defective intracellular Ca2+ signaling contributes to cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1398–H1408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Bastie D, Levitsky D, Rappaport L, Mercadier JJ, Marotte F, Wisnewsky C, Brovkovich V, Schwartz K, Lompre AM. Function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and expression of its Ca2(+)-ATPase gene in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res 66: 554–564, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dvir-Ginzberg M, Gagarina V, Lee EJ, Hall DJ. Regulation of cartilage-specific gene expression in human chondrocytes by SirT1 and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 283: 36300–36310, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feige JN, Auwerx J. Transcriptional targets of sirtuins in the coordination of mammalian physiology. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 303–309, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman AM, Weinberg EO, Ray PE, Lorell BH. Selective changes in cardiac gene expression during compensated hypertrophy and the transition to cardiac decompensation in rats with chronic aortic banding. Circ Res 73: 184–192, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freire G, Ocampo C, Ilbawi N, Griffin AJ, Gupta M. Overt expression of AP-1 reduces alpha myosin heavy chain expression and contributes to heart failure from chronic volume overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43: 465–478, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galderisi M, Anderson KM, Wilson PW, levy D. Echocardiography evidence for existence of distinict diabetic cardiomyopathy (The Framingham heart study ). Am J Cardiol 68: 85–89, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambetta K, Al-Ahdab MK, Ilbawi MN, Hassaniya N, Gupta M. Transcription repression and blocks in cell cycle progression in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2268–H2275, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Z, Ye J. Inhibition of transcriptional activity of c-JUN by SIRT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 376: 793–796, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 425: 191–196, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung L, Chen J, Huang SS, Lee R, Su M. Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes. Cardiovasc Res 47: 549–555, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ignatowicz E, Baer-Dubowska W. Resveratrol, a natural chemopreventive agent against degenerative diseases. Pol J Pharmacol 53: 557–569, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protien sir 2 is a NAD-dependent histone decetylase. Nature 403: 795–800, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, Geny B, Laakso M, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 127: 1109–1122, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landry J, Slama JT, Sternglanz R. Role of NAD(+) in the deacetylase activity of the SIR2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 278: 685–690, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Zhao L, Yi-Ming W, Yu YS, Xia CY, Duan JL, Su DF. Sirt1 hyperexpression in SHR heart related to left ventricular hypertrophy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 87: 56–62, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Limas CJ, Olivari MT, Goldenberg IF, Levine TB, Benditt DG, Simon A. Calcium uptake by cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 21: 601–605, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maciel LM, Polikar R, Rohrer D, Popovich BK, Dillmann WH. Age-induced decreases in the messenger RNA coding for the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2(+)-ATPase of the rat heart. Circ Res 67: 230–234, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBurnney MW, Yang XF, Jardine K, Bieman M, Th'ng J, Lemieux M. The mammalian SIR2α protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 23: 38–54, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer M, Schillinger W, Pieske B, Holubarsch C, Heilmann C, Posival H, Kuwajima G, Mikoshiba K, Just H, Hasenfuss G. Alterations of sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins in failing human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 92: 778–784, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto MI, del Monte F, Schmidt U, DiSalvo TS, Kang ZB, Matsui T, Guerrero JL, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A, Hajjar RJ. Adenoviral gene transfer of SERCA2a improves left-ventricular function in aortic-banded rats in transition to heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 793–798, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyazaki R, Ichiki T, Hashimoto T, Inanaga K, Imayama I, Sadoshima J, Sunagawa K. SIRT1, a longevity gene, downregulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1263–1269, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizushige K, Yao L, Noma T, Kiyomoto H, Yu Y, Hosomi N, Ohmori K, Matsuo H. Alteration in left ventricular diastolic filling and accumulation of myocardial collagen at insulin-resistant prediabetic stage of a type II diabetic rat model. Circulation 101: 899–907, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson ER, Naugle JE, Zhang X, Bomser JA, Meszaros JG. Inhibition of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation by resveratrol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1131–H1138, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, Peshkin L, Price NL, Labinskyy N, Swindell WR, Kamara D, Minor RK, Perez E, Jamieson HA, Zhang Y, Dunn SR, Sharma K, Pleshko N, Woollett LA, Csiszar A, Ikeno Y, Le Couteur D, Elliott PJ, Becker KG, Navas P, Ingram DK, Wolf NS, Ungvari Z, Sinclair DA, de Cabo R. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab 8: 157–168, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira L, Matthes J, Schuster I, Valdivia HH, Herzig S, Richard S, Gómez AM. Mechanisms of [Ca2+]i transient decrease in cardiomyopathy of db/db type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes 55: 608–615, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pillai JB, Gupta M, Rajamohan SB, Lang R, Raman J, Gupta MP. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-deficient mice are protected from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1545–H1553, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pillai JB, Chen M, Rajamohan SB, Samant S, Pillai VB, Gupta M, Gupta MP. Activation of SIRT1, a class III histone deacetylase, contributes to fructose feeding mediated induction of the α-myosin heavy chain expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1388–H1397, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regan TJ, Lyons MM, Ahmed SS, Levinson GE, Oldewurtel HA, Ahmad MR, Haider B. Evidence for cardiomyopathy in familial diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 60: 884–899, 1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogina B, Helfand SL. Longevity regulation by Drosophila Rpd3 deacetylase and caloric restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15998–6003, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rojas M, Meredith D, Kylander J, Barrick D, Corn D, Lockyer P, Patterson C, Willis MS. Echocardiography under isoflurane anesthesia affects heart rate and function in commonly utilized mouse strains. FASEB 22: 970.–44., 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakamoto J, Miura T, Shimamoto K, Horio Y. Predominant expression of sir 2 alpha. An NAD-dependent histone deacetylase, in the embryonic heart and brain. FEBS Lett 556: 281–286, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shigematsu S, Ishida S, Hara M, Takahashi N, Yoshimatsu H, Sakata T, Korthuis RJ. Resveratrol, a red wine constituent polyphenol, prevents superoxide-dependent inflammatory responses induced by ischemia/reperfusion, platelet-activating factor, or oxidants. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 810–817, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith JS, Brachmann CB, Celic I, Kenna MA, Muhammad S, Starai VJ, Avalos JL, Escalante-Semerena JC, Grubmeyer C, Wolberger C, Boeke JD. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6658–6663, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su H, Hung L, Chen J. Resveratrol, a red wine antioxidant, possesses an insulin like effect in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1339–E1346, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suarez J, Scott B, Dillmann WH. Conditional increase in SERCA2a protein is able to reverse contractile dysfunction and abnormal calcium flux in established diabetic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1439–R1445, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szkudelski T. Resveratrol inhibits insulin secretion from rat pancreatic islets. Eur J Pharmacol 552: 176–181, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Juhasz B, Ahan L, Otani H, Bagchi D, Das DK, Maulik N. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 720–729, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Mahjoub H, Tartière JM, Kesri-Tartière L, Godard S, Peltier M. Prognostic impact of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a prospective five-year study. Heart 94: 1450–1455, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trost SU, Belke DD, Bluhm WF, Meyer M, Swanson E, Dillmann WH. Overexpression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase improves myocardial contractility in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 51: 1166–1171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vahtola E, Louhelainen M, Merasto S, Martonen E, Penttinen S, Aahos I, Kytö V, Virtanen I, Mervaala E. Forkhead class O transcription factor 3a activation and Sirtuin1 overexpression in the hypertrophied myocardium of the diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat. J Hypertens 26: 334–344, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vetter R, Rehfeld U, Reissfelder C, Weiss W, Wagner KD, Gunther J, Hammes A, Tschope C, Dillmann W, Paul M. Transgenic overexpression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase improves reticular Ca2+ handling in normal and diabetic rat hearts. FASEB J 16: 1657–1659, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature 430: 686–689, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright R, Jr, Mendola J, Lacy PE. Effect of niacin/nicotinamide deficiency on the diabetogenic effect of streptozotocin. Cell Mol Life Sci 44: 38–40, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zarain-Herzberg A, Marques J, Sukovich D, Periasamy M. Thyroid hormone receptor modulates the expression of the rabbit cardiac sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase gene. J Biol Chem 269: 1460–1467, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhong Y, Ahmed S, Grupp IL, Matlib LA. Altered SR protein expression associated with contractile dysfunction in diabetic rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1137–H1147, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]