Abstract

Tumor protein D52 (also known as CRHSP-28) is highly expressed in multiple cancers and tumor-derived cell lines; however, it is normally abundant in secretory epithelia throughout the digestive system, where it has been implicated in Ca2+-dependent digestive enzyme secretion (41). Here we demonstrate, using site-specific mutations, that Ca2+-sensitive phosphorylation at serine 136 modulates the accumulation of D52 at the plasma membrane within 2 min of cell stimulation. When expressed in Chinese hamster ovary CHO-K1 cells, D52 colocalized with adaptor protein AP-3, Rab27A, vesicle-associated membrane protein VAMP7, and lysosomal-associated membrane protein LAMP1, all of which are present in lysosome-like secretory organelles. Overexpression of D52 resulted in a marked accumulation of LAMP1 on the plasma membrane that was further enhanced following elevation of cellular Ca2+. Strikingly, mutation of serine 136 to alanine abolished the Ca2+-stimulated accumulation of LAMP1 at the plasma membrane whereas phosphomimetic mutants constitutively induced LAMP1 plasma membrane accumulation independent of elevated Ca2+. Identical results were obtained for endogenous D52 in normal rat kidney and HeLA cells, where both LAMP1 and D52 rapidly accumulated on the plasma membrane in response to elevated cellular Ca2+. Finally, D52 induced the uptake of LAMP1 antibodies from the cell surface in accordance with both the level of D52 expression and phosphorylation at serine 136 demonstrating that D52 altered the plasma membrane recycling of LAMP1-associated secretory vesicles. These findings implicate both D52 expression and Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation at serine 136 in lysosomal membrane trafficking to and from the plasma membrane providing a novel Ca2+-sensitive pathway modulating the lysosome-like secretory pathway.

Keywords: Ca2+-stimulated secretion, Ca2+-stimulated phosphorylation, lysosomal secretion, membrane trafficking

we previously purified calcium-regulated heat-stable protein of 28 kDa (CRHSP-28) from rat pancreatic acinar cells as a major Ca2+-regulated phosphoprotein (18). At that time, the protein had been recently purified from gastric mucosa also on the basis of its acute Ca2+-sensitive phosphorylation and called CSPP28 (34). The amino acid sequences obtained in both studies matched the predicted open reading frame of an mRNA termed D52 that had been identified as being overexpressed in human breast carcinomas (8). Subsequently, orthologous D52 messages were reported because of their overexpression in lung carcinoma (termed N8) (10) and retroviral insertion in proliferating avian neuroretinal cells (termed R10) (36). Eventual cloning studies revealed that D52 is in fact a member of a small family of proteins known as the tumor protein D52 (TPD52) family (reviewed in Ref. 6). For clarity we have decided to utilize the now-conventional nomenclature and refer to the protein as D52 rather than CRHSP-28.

Although D52 mRNA expression is induced in multiple cancers, the protein is normally abundant in exocrine cells of the pancreas, lacrimal, and submandibular glands, as well as chief cells, Paneth cells, and mucus-secreting cells throughout the gastrointestinal tract (18). The TPD52 proteins are highly charged acidic molecules that contain a coiled-coil motif that mediates homomeric and heteromeric interactions among family members (9, 42). D52 is both a cytosolic and peripheral membrane protein but contains no obvious lipid association motifs (41). Under basal conditions, D52 localizes on the cytoplasmic side of trans-Golgi and early endosomal compartments in the apical cytoplasm of secretory epithelia (43). In isolated acinar cells and cultured colonic mucosal T84 cells, stimulation with Ca2+-mobilizing secretagogues induces a rapid and transient phosphorylation of D52 that coincides with its accumulation at the apical plasma membrane (23, 43). Consistent with its expression in secretory cells, apical localization, and acute Ca2+-sensitivity for phosphorylation, D52 was shown to regulate Ca2+-stimulated secretion when introduced into permeabilized pancreatic acinar cells that had been partially depleted of the endogenous protein (41). Similarly, depletion of the D52 ortholog by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in Drosophila S2 cultured cells significantly inhibited constitutive secretion (3). In Caenorhabditis elegans, RNAi depletion of the D52 ortholog inhibited fat deposition that occurs in intestinal epithelia (2).

A number of studies have identified putative binding proteins for TPD52 family members by use of yeast two-hybrid screening, in vitro binding assays, and coimmunoprecipitations. D52 interacts with MAL2, an integral membrane protein localized to lipid rafts in epithelial cells (46). MAL2 is essential for the normal transcytotic delivery of glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored proteins to the apical membrane of hepatoma HepG2 cells (16). In acinar cells, we demonstrated that D52 undergoes a Ca2+-dependent interaction with annexin VI, a Ca2+-regulated phospholipid binding protein reported to function in endosome formation and trafficking (42). Proux-Gillardeaux et al. (37) reported that the D52 ortholog D53 interacts with members of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex necessary for membrane fusion. D53 directly interacted with synaptobrevin 2 and syntaxin 1 in vitro and coimmunoprecipitated with synaptobrevin 2 in PC12 cell lysates, where the proteins partially colocalized to an endosomal compartment. Boutros et al. (5) demonstrated that an alternatively spliced form of D53 specifically interacts with 14-3-3 proteins, which are scaffolding molecules involved in numerous cellular processes. Finally, D53 was also shown to interact with the apoptosis signal regulated kinase and positively modulate its activity (12). Despite these mounting biochemical studies, the functional significance of TPD52 protein interactions has remained elusive. From a functional perspective, the ability of D52 to modulate secretion in permeabilized acinar cells is consistent with its biochemical interactions with MAL2, annexin VI, and SNARE proteins. On the other hand, D53 was also shown to be differentially expressed throughout the cell cycle and when ectopically expressed to induce a multinucleated phenotype (7). Moreover, D52 expression in 3T3 fibroblasts was shown to induce an oncogenic transformation as deduced by enhanced proliferation, loss of contact inhibition, and growth in soft agar. Furthermore, implantation of D52-transformed cells in nude mice produced metastatic tumors (26). Finally, transient overexpression of an EGFP-D52 fusion construct in the LNCaP prostate cancer cell line significantly enhanced cell migration, whereas downregulation of endogenous D52 expression strongly induced cell death (45). These later results are clearly in line with the highly documented overexpression of D52 in numerous cancers.

The present study examined the role of the Ca2+-sensitive phosphorylation of D52 in regulating membrane trafficking. In accordance with the effects of physiological secretagogues to induce D52 phosphorylation in vivo (17, 23, 24), when transfected into CHO-K1 cells, D52 undergoes a robust Ca2+-sensitive phosphorylation that coincides with its rapid accumulation along the plasma membrane. Consistent with a recent report (11), site-specific mutational analysis indicated that D52 phosphorylation occurs at serine 136. Null and phosphomimetic mutations of serine 136 demonstrated that the Ca2+-stimulated plasma membrane accumulation of D52 is dependent on its phosphorylation. D52 was found to strongly colocalize with markers of a lysosome-like secretory pathway. Because lysosomal secretion can be measured by the accumulation of lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP1) at the plasma membrane (21), a role for D52 in modulating lysosome-like secretory pathway was investigated. LAMP1 accumulation at the plasma membrane is highly regulated by both D52 expression levels and its phosphorylation at serine 136. These findings clearly establish a functional role for D52 phosphorylation in Ca2+-regulated plasma membrane trafficking and are consistent with its secretory effects in digestive epithelia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

Anti-D52 polyclonal antibodies were previously described (18). Anti-hemagglutinin (HA) mouse monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 2367) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-HA rat monoclonal (cat. no. 11867423001) was purchased from Roche Diagnostics, Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Anti-LAMP1 (cat. no. VAM-EN001) was purchased from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). Alexa 488-conjugated anti-LAMP1 (cat. no. 121608) was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Anti-Rab27A (cat. no. sc22990) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Golgin 97 (cat. no. A21270) and Alexa-conjugated rabbit, rat, goat, and mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) (cat. no. 610456) was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA). The anti-AP3 developed by Andrew A. Peden was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA. Anti-VAMP7 (cat. no. ab36195) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-mannose-6-phosphate receptor was a gift from H. T. McMahon. All antibodies were characterized before dual-immunofluorescence labeling studies by serial dilutions to determine optimal conditions and negative controls (usually secondary antibody alone) to ensure specificity (data not shown). Peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG and donkey anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences (Piscataway, NJ).

Other reagents.

Goat serum, Triton X-100, cold-water fish skin gelatin, benzamidine, ionomycin, cyclohexamide, Lys3-bombesin, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Alexa 488 conjugated wheat germ agglutinin, LysoTracker, lysine-fixable FITC-dextran [10,000 molecular weight (MW)], ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), TOPRO 3-iodide, fetal bovine serum, TrypLE Express, and HAM's F12 were purchased from Invitrogen. HAMS F12K and proline were purchased from Mediatech, Cellgro (Manassas, VA). Bovine serum albumin and a protease inhibitor cocktail containing AEBSF, aprotinin, EDTA, leupeptin, and E64 were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ). Ultralink protein A beads were purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Protein determination reagent was from Bio-Rad Life Science Research (Hercules, CA). TransIT-CHO-K1, TransIT-LT1, and Endotoxin removal kits were purchased from Mirus Biotechnology (Madison, WI). DNA Maxi and Mini-prep kits and PCR reagents were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Restriction enzymes and ligation kits were purchased from Fermentas (Glen Burnie, MD). The QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Glutathione-Sepharose beads were purchased from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). Formaldehyde was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA).

Cell culture.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1), HeLa, and normal rat kidney (NRK) cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). CHO-K1 and HeLa cells were grown in HAMS F-12 with 5 or 10% FBS, respectively. NRK cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. All media contained penicillin, streptomycin, and gentamicin. Stock cultures were maintained in a 37°C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and were passaged by using TrypLE Express. Media was changed the day after seeding and every 3–4 days thereafter. Experiments were conducted on confluent cell monolayers. All cell types were used between passages 4 and 27.

Subcloning and site-directed mutagenesis.

For eukaryotic expression studies, the coding region of human D52 was subcloned into the pHM6 vector (Roche Diagnostics, Roche Applied Science) containing an NH2-terminal HA-tag using HindIII and KpnI restriction sites. All point mutations of D52 were generated by substituting specific serine residues with glutamate or aspartate (phosphomimetic) or alanine (phospho-null) by using the Quick-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the pHM6D52 plasmid.

Cell transfection.

CHO-K1 and NRK cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected at 80% confluency by using the TransIT-CHO-K1 or TransIT-LT1 kit from Mirus Biotechnology, respectively, by adding 2 μg of DNA per well according to manufacturer's instructions. Cells were maintained in a 37°C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere for 18–24 h posttransfection before treatment.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

The buffer used for blocking and incubation steps contained: 1× PBS, 3% bovine serum albumin, 2% goat serum, 0.7% cold-water fish skin gelatin and 0.2% Triton X-100. CHO-K1 cells were grown on coverslips and transfected at 80% confluency in six-well plates for 18–24 h with pHM6, pHM6D52wt, pHM6D52S136/A, pHM6D52S136/D, or pHM6D52S136/E. Cells were treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin or 100 nM Lys3-bombesin for 5 min prior to fixation in 2% formaldehyde in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temperature (temp). Following fixation, cells were blocked for 30 min at room temp, and primary antibodies were added simultaneously for 1 h at room temp. Secondary antibodies were added simultaneously for 1 h at room temp after cells were washed with 1× PBS (3 × 5 min). For external cell surface labeling, anti-LAMP1 (1:100 in fresh media) was added for 30 min to cells at 4°C. Cells were then treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin or 100 nM Lys3-bombesin for 5 min prior to fixation in 2% formaldehyde in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temp and then permeabilized with TX-100 containing buffer and subsequently labeled for D52. For antibody uptake experiments, anti-LAMP1 directly conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:20 in fresh medium) was added to cells for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin prior to fixation in 2% formaldehyde in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with TX-100-containing buffer and subsequently labeled for D52. For dextran uptake experiments, 10,000-MW, FITC-conjugated, lysine-fixable dextran was added to cells (2.5 mg/ml) for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed and chased for 2 h at 37°C. At the end of the chase, cells were labeled as described earlier with the exception that the dextran signal was amplified by using an anti-FITC conjugated Alexa 488 antibody raised in goat. For the LysoTracker experiment, LysoTracker conjugated to Alexa 546 was added at 5 μM for 1 h at 37°C and then cells were labeled as previously described. Coverslips were mounted by using ProLong Gold Antifade reagent with DAPI to label nuclei. For dual-immunofluorescence measurements, fluorophores were individually excited at the appropriate wavelength to ensure no overlapping excitation between channels. Multiphoton images (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. S1) were captured using a Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 MP with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope and a Plan Apo ×60 oil objective with a numerical aperture of 1.4. Images were captured and processed via Bio-Rad and Image J or Photoshop software, respectively. Brightfield images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope, a PlanApo ×100 oil objective with a numerical aperture of 1.4, and a Hamamatsu Orca camera. Images were deconvolved by using Volocity software and were processed with Volocity, Image J, or Photoshop software.

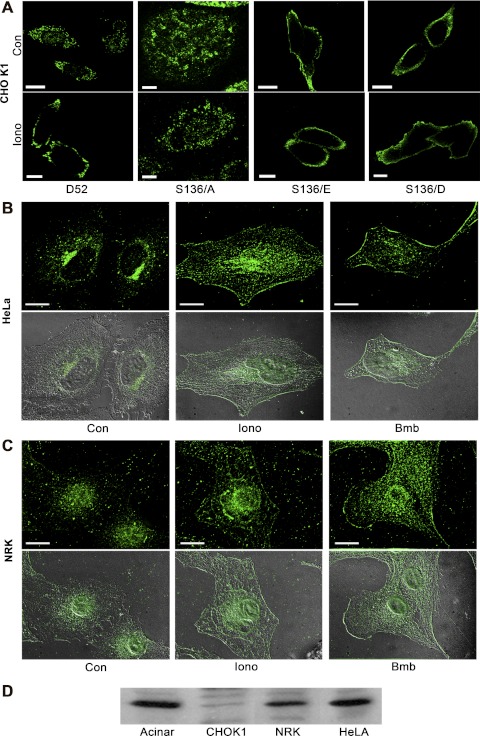

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation at serine 136 mediates D52 accumulation on the plasma membrane. A: a single confocal optical section of CHO-K1 cells transfected with Wt-D52 or the indicated S136 mutants that were treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin for 5 min prior to fixation in 2% formaldehyde. D52 immunoreactivity was detected in A by using anti-hemagglutinin (HA) tag (1:100) with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:500). Note the pronounced accumulation of Wt-D52 to the plasma membrane in response to elevated cellular Ca2+, which was abolished in the S136/A mutants. Likewise, note the pronounced accumulation of phosphomimetic mutants along the plasma membrane independent of elevated Ca2+. B and C: endogenous D52 (1:100) was analyzed in HeLa and normal rat kidney (NRK) cells treated as control or stimulated with 2 μM ionomycin or 100 nM of the bombesin analog Lys3-bombesin (Bmb) for 5 min and detected by use of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500). Images are a reconstructed z-series acquired by brightfield microscopy. Corresponding differential interference microscopy (DIC) images are shown below each immunofluorescence image. All images are representative of multiple determinations performed on at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 20 μm. D: immunoblot of D52 (1:1,000) in lysates (100 μg) from pancreatic acinar cells, CHO-K1, NRK, and HeLa cells. Note that acinar, NRK, and HeLa cells express significant levels of endogenous D52, whereas CHO-K1 cells exhibit much less immunoreactivity.

Quantification of immunofluorescence images.

Multiple (10–15) brightfield, z-series images from at least three separate tissue preparations were analyzed by using Image J software with the colocalization threshold plug-in. Threshold values for each image were automatically determined by the software and, therefore, were unbiased and provided conservative estimates. To analyze plasma membrane immunofluorescence (Figs. 5 and 6), 30-pixel-wide by 10-pixel-high selections at the plasma membrane in multiple (10–13) brightfield, single z-sections from at least three separate tissue preparations were analyzed by using the Image J software line density plot function. Raw numbers produced from Image J processing were analyzed with Excel software. Data reported are means and SE, and P values were calculated by an unpaired Student's t-test.

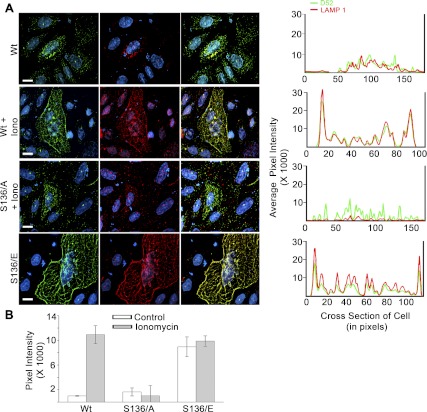

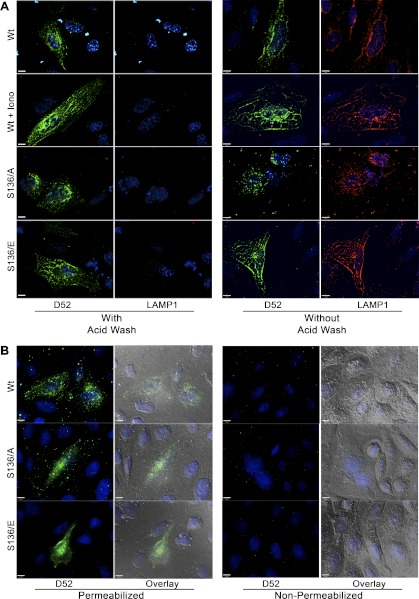

Fig. 5.

Lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) exocytosis is dependent on D52 expression levels and its Ca2+-regulated phosphorylation at serine 136. A, left: intracellular D52 and externalized LAMP1 were analyzed in CHO-K1 cells transfected with Wt-D52, S136/A, or S136/E. Cells were treated with 0.01% DMSO as control or with 2 μM ionomycin for 5 min and then incubated at 4°C with anti-LAMP1 (1:100) to label externalized antigen. Cells were then fixed in 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized, and further labeled with anti-D52 (1:100). D52 and LAMP1 immunoreactivities were detected postfixation, by use of Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:250), respectively. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Postcollection, D52 and LAMP1 images were applied green and red pseudo-colors, respectively. Each image is a reconstructed z-series obtained by brightfield microscopy. All images are representative of multiple determinations performed on at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 13 μm. A, right: line density analysis of D52 (green) and LAMP1 (red) staining across a single cell. B: quantification of LAMP1 localization at the plasma membrane designated as the first 20 pixels of signal acquired at the cell periphery from multiple line density plots. Data are means ± SE (n = 10 for each experimental condition) performed in at least 3 separate tissue preparations.

Immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting were conducted as previously described (23).

32P labeling.

CHO-K1 cells were incubated in phosphate-free HEPES buffer containing (in mM) 10 HEPES, 137 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.56 MgCl2, 1.28 CaCl2, 5.5 d-glucose, 2 l-glutamine, and an essential amino acid solution for 2 h at 37°C in the presence of 0.3 mCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate. At the end of 2 h, cells were washed with phosphate-free HEPES buffer and treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin for 2 min. Cells were scraped into 0.3 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris (pH 7.4), 150 NaCl, 5 EDTA, 25 NaF, 10 tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 1.0 benzamidine, 0.1 PMSF, 0.2% TX-100, and a protease inhibitor cocktail. Immunoprecipitations were conducted as previously described (23).

RESULTS

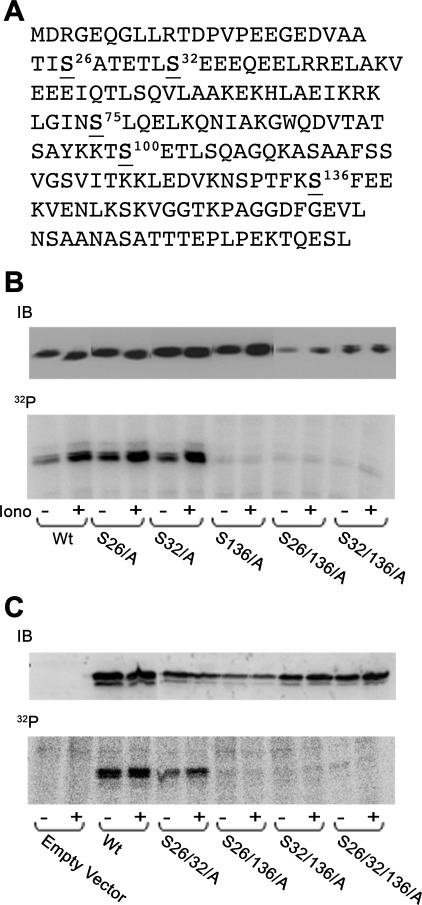

Ca2+-dependent D52 phosphorylation occurs at serine 136. We previously reported that, in isolated pancreatic acini (17) and cultured T84 cells (23), D52 phosphorylation is specifically regulated by elevated cellular Ca2+ and occurs exclusively on one or more of the 16 serine residues of the protein. Using mass spectrometry of purified D52 from gastric mucosa, Chew et al. (11) recently reported that D52 phosphorylation occurs at serine 136. To further analyze D52 phosphorylation, multiple serine/alanine mutants of D52 were expressed in 32P-labeled CHO-K1 cells and detected by immunoprecipitation. Results confirmed that serine 136 is a major D52 phosphorylation site (Fig. 1). Compared with wild-type (Wt) D52, serine 136/alanine (S136/A) mutation strongly reduced basal and completely abolished ionomycin-stimulated phosphorylation of the protein. Serine 136 is positioned in the minimal consensus sequence for phosphorylation by casein kinase II (CKII), which is unique among serine/threonine kinase enzymes because it requires the presence of acidic residues in the +3 downstream position (SXXE/D) (27). D52 contains four such sites (serine 26, 32, 75, and 136). Each was individually mutated to alanine alone or in various combinations demonstrating that serine 136 is clearly the single major phospho-acceptor site of the molecule (serine 75 mutations are not shown). In all S136/A-containing mutants, a faint basal level of phosphorylation remained that was not present in cells transfected with vector alone. The identity of this residue remains under investigation. Collectively, these data support that serine 136 is the major Ca2+-regulated D52 phosphorylation site in vivo.

Fig. 1.

D52 phosphorylation occurs on serine 136. A: human D52 amino acid sequence. Serines 26, 32, 75, and 136 are predicted casein kinase II (CKII) sites. Serine 100 is a predicted CaM kinase II site. B: Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells were transiently transfected with indicated constructs for 18–24 h and then metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate for 2 h. Cells were treated as control (Con) or with 2 μM ionomycin (Iono) for 5 min. D52 was immunoprecipitated from lysates and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Upper gels are immunoblots (IB; 20 μg/lane) of D52 demonstrating transfection levels for each construct. Note the lack of incorporation of phosphate in all mutants containing the S136/A mutation. Wt, wild-type.

D52 phosphorylation induces its accumulation on plasma membrane. D52 is an acidic and hydrophilic protein that partitions between membrane and cytosol following cell fractionation (42). In pancreatic acinar cells, D52 is present in a supranuclear compartment under basal conditions and redistributes within minutes of secretagogue stimulation to the apical plasma membrane (43). Similar localization of D52 to apical regions of polarized T84 cells following muscarinic receptor activation was also reported (23). Consistent with these studies, when expressed in nonpolarized CHO-K1 cells, Wt-D52 was present in a punctuate pattern throughout the cytoplasm and then rapidly accumulated at the cell periphery following Ca2+-elevation by 5-min treatment with ionomycin (Fig. 2A). This Ca2+-sensitive redistribution to the plasma membrane was most highly pronounced at lower levels of D52 expression. When more highly expressed, Ca2+-dependent plasma membrane accumulation of D52 was clearly evident; however, because significant signal remained throughout the cytoplasm, the contrast between basal and stimulated conditions was diminished. Images in Fig. 2A are single optical sections of cells. When viewed as reconstructed z-series images (see Fig. 2, B and C, and Figs. 3–6, 8–9, and S1–S2), the Ca2+-induced accumulation of D52 at the cell periphery resulted in an overall enhanced signal intensity potentially reflecting an accumulation of cytosolic forms of D52 on membranes. However, subcellular fractionation indicated equal amounts of D52 in soluble and particulate fractions and this distribution did not change following cell stimulation (data not shown).

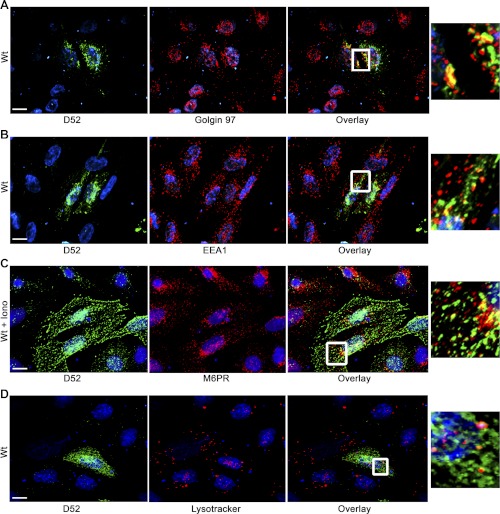

Fig. 3.

Partial colocalization of D52 with Golgi. D52 was analyzed in CHO-K1 cells transfected with Wt-D52. Following 2% formaldehyde fixation, D52 (1:100) immunoreactivity was detected by use of Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) (A and B). Golgin 97 (1:50) (A) and early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) (1:100) (B) immunoreactivities were detected by use of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:250). C: D52 immunoreactivity was detected with anti-HA tag (1:100) by using Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:250), and mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M-6-P) (1:100) immunoreactivity was detected with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500). Note that cells costained for M-6-P had been treated with ionomycin for 5 min prior to fixation. D: cells were labeled with LysoTracker (5 μM, 1 h at 37°C) prior to fixation and staining for D52. Nuclei were labeled with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) except in LysoTracker-labeled cells where TOPO-3 iodide was used. Postcollection, D52 and costained antigens were applied green and red pseudo-colors, respectively. Note the moderate colocalization of D52 with Golgin 97 but more modest colocalization with EEA1, M-6-P, and LysoTracker. Each image is a reconstructed z-series obtained by brightfield microscopy. All images are representative of multiple determinations performed on at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 13 μm.

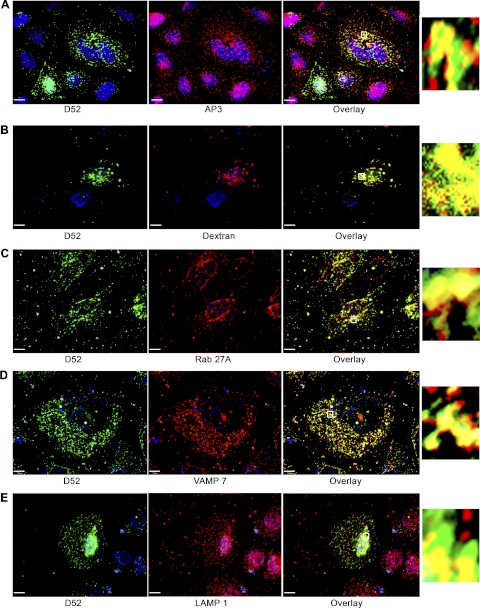

Fig. 4.

D52 is present on a lysosome-like secretory compartment. CHO-K1 cells transfected with Wt-D52 were fixed in 2% formaldehyde and labeled with antibodies for D52, AP-3, Rab27A, and vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 (VAMP7) (all at 1:100). Immunoreactivities were detected by using Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) for D52, and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:250) (A, B, D, and E) or Alexa 546-conjugated anti-goat (1:100) (C) for the costained antigen. For dextran labeling of lysosomes, cells were incubated with FITC-dextran (10,0000 MW) for 3 h at 37°C followed by a 2-h chase period prior to fixation and staining for D52. The FITC-dextran signal was amplified by use of anti-FITC goat-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:100). Note the extensive colocalization of D52 with each marker (see Table 1 for quantification). Insets are enlargements of regions denoted by the small boxed region in each overlay. Each image is a reconstructed z-series obtained by brightfield microscopy. All images are representative of multiple determinations performed on at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 13 μm.

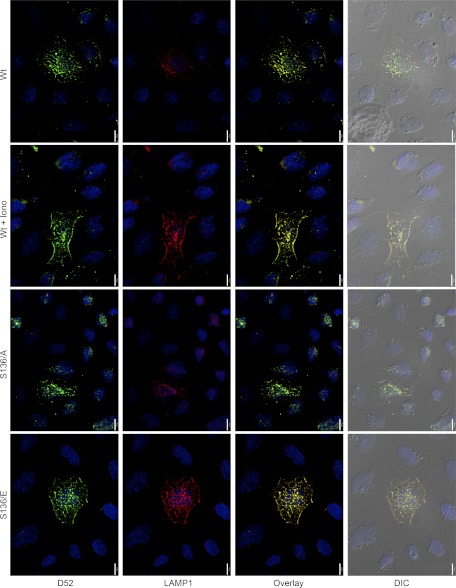

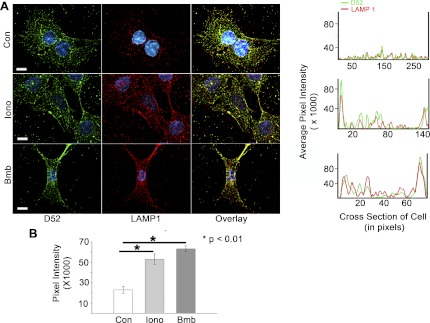

Fig. 6.

Endogenous D52 translocates to plasma membrane with LAMP1 during Ca2+-stimulated exocytosis. Intracellular D52 and externalized LAMP1 were analyzed in NRK cells treated with 0.01% DMSO as control, 2 μM ionomycin, or 100 nM Lys3-bombesin for 5 min. Cells were incubated at 4°C with anti-LAMP1 to label externalized LAMP1 as described in Fig. 5. Each image is a reconstructed z-series obtained by brightfield microscopy. All images are a single representative experiment performed in at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 13 μm. A, right: line density analysis of D52 (green) and LAMP1 (red) staining across a single cell. B: quantitative analysis of LAMP1 localization at the plasma membrane designated as the first 20 pixels of signal acquired at the cell periphery from multiple line density plots. Data are means ± SE (n = 10 for each experimental condition) performed in at least 3 separate tissue preparations.

Fig. 8.

Conformation of LAMP1 surface labeling and intracellular labeling of D52. A: CHO-K1 cells were transfected with Wt-D52, S136/A, or S136/E and treated as control or with 2 μM ionomycin for 5 min. Cells were immunolabeled for external LAMP1 as described in Figs. 5 and 6. Following LAMP1 labeling, coverslips were rinsed 3 times with ice-cold PBS followed by fixation or washed an additional 5 times in acid wash buffer containing (in mM) 100 glycine, 20 mg acetate, 50 KCl, pH 2.2, all at 4°C. After being washed with PBS, cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde, blocked, permeabilized, and immunolabeled for D52 (1:100) by using Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500). Note the complete loss of LAMP1 surface label with acid washing. B: cells were surfaced labeled for LAMP1 as described in Figs. 5 and 6. Following 2% formaldehyde fixation, cells were permeabilized or not with Triton X-100 during labeling with D52 antibodies. Note that cell permeabilization is essential to detect D52 immunoreactivity.

Fig. 9.

Overexpression of D52 and D52 phosphorylation at serine 136 stimulates LAMP1 trafficking and retrieval from the plasma membrane. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with Wt-D52 or D52 phospho-mutants for 18 h prior to a 2-h incubation at 37°C with Alexa 488-conjugated LAMP1 antibodies (1:20). Where indicated, 2 μM ionomycin was added for the last 5 min of incubation. Cells were then acid washed as described in Fig. 8, fixed in 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized, and labeled for D52 (1:100) with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500). Note that compared with adjacent cells expressing low levels of D52, transfected cells show a marked accumulation of LAMP1 that is concentrated in perinuclear regions. Treatment of cells expressing Wt-D52 with ionomycin or expression of S136/E mutants under basal conditions significantly increased LAMP1 and D52 labeling just underneath peripheral plasma membrane regions. Also note that cells expressing S136/A mutants accumulate significant LAMP1 label compared with surrounding nontransfected cells but fail to show the enhanced peripheral label in response to ionomycin. Each image is a reconstructed z-series obtained by brightfield microscopy. All images are a single representative experiment performed in at least 3 separate tissue preparations. Bars, 13 μm.

Because elevated Ca2+ acutely induced serine 136 phosphorylation, the significance of this modification in mediating the Ca2+-dependent accumulation of D52 at the plasma membrane was investigated. Analysis of S136/A mutants in CHO-K1 cells demonstrated the same pattern of localization as Wt-D52 under basal conditions; however, the S136/A mutants failed to accumulate at the cell periphery in response to elevated Ca2+ (Fig. 2A). Moreover, expression of serine 136/glutamate (S136/E) or serine 136/aspartate (S136/D) phosphomimetic mutants induced a constitutive accumulation of D52 to peripheral regions of cells under basal conditions that was independent of elevated Ca2+. Attempts to image D52 localization in real time by using EGFP-D52 constructs were unsuccessful, because transfected cells rapidly accumulate the tagged protein in large vacuoles (data not shown, also see Ref. 11).

Ca2+-dependent plasma membrane recruitment of endogenous D52. In contrast to CHO-K1 cells, which express relatively low levels of endogenous D52, the protein is expressed in HeLa and NRK cells at levels comparable to those seen in pancreatic acinar cells (Fig. 2D). Immunofluorescence analysis of D52 was conducted in HeLa and NRK cells stimulated with either ionomycin or an analog of the peptide bombesin, which increases intracellular Ca2+ via activation of the G protein-coupled gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (13). Essentially identical results to those seen in transfected CHO-K1 cells were obtained (Fig. 2, B and C, for HeLa and NRK cells, respectively). When viewed in reconstructed z-series images, D52 was abundant within perinuclear regions under basal conditions and then rapidly accumulated along the plasma membrane following 5 min of stimulation. Consistent with its phosphorylation, D52 accumulation at plasma membrane was detected as early as 2 min of stimulation; however, earlier times were not analyzed. Taken together, these data strongly support that the Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of D52 at serine 136 directs its rapid accumulation at peripheral plasma membrane regions.

D52 exhibits minimal colocalization with Golgi, early- and late-endosomal markers. In acinar cells, D52 partially colocalizes with the trans-Golgi marker TGN-38 and strongly with EEA1 (43). D52 immunoreactivity in CHO-K1 cells similarly showed some overlap with Golgin 97 in perinuclear regions of cells where both proteins were highly expressed but little or no colocalization was noted outside of that zone where D52 remained abundant (Fig. 3A). In contrast to its significant colocalization with EEA1 in acinar cells (43), D52 showed only minimal overlap with this marker in transfected CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 3B). Similarly, D52 showed little or no overlap with mannose-6-phosphate receptors (Fig. 3C), a marker of late endosomes, and LysoTracker (Fig. 3D), which labels acidic compartments including mature lysosomes.

D52 is present within a lysosome-like secretory compartment. Borner et al. (4), using a proteomic screen in combination with a siRNA knockdown strategy in HeLa cells to identify proteins associated with clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs), reported that D52 and the ortholog D53L1 are highly expressed on CCVs purportedly derived from the adaptor protein-3 (AP-3) complex. Consistent with these findings, significant colocalization of AP-3 with D52 was detected throughout the cytoplasm of cells and was most concentrated in perinuclear regions (Fig. 4A). When quantified by measuring the colocalization of voxels obtained from multiple reconstructed z-series images, AP-3 showed a 56.9% colocalization with D52 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Colocalization of markers of the lysosme-like secretory pathway with D52

| % Colocalization with D52 wt | |

|---|---|

| AP3 | 56.9 ± 13.2 |

| Dextran | 36.0 ± 3.5 |

| Rab27A | 61.7 ± 10.5 |

| VAMP 7 | 72.5 ± 6.5 |

| LAMP 1 | 39.7 ± 3.6 |

Values are means ± SE. The % colocalization of voxels for each marker with D52 was quantified from multiple (n ≥ 10) reconstructed z-series images obtained from 3 separate tissue preparations. wt, Wild-type.

Because the AP-3 complex was previously shown to regulate the trafficking of lysosomal membrane proteins (25, 35) and is reported to be essential for the formation of lysosome-like secretory organelles (15), the potential that D52 was present within a lysosome-like secretory pathway was further investigated. To first identify lysosomal compartments, cells were prelabeled with lysine-fixable 10,000 MW FITC-dextran for 3 h, then washed and chased for an additional 2 h (21) prior to fixation and labeling for D52. The endocytosed FITC-dextran showed a 36% colocalization of voxels with D52 that was most abundant in perinuclear regions of cells (Fig. 4B and Table 1). Plasma membrane trafficking of lysosome-like secretory vesicles was shown to be mediated by Rab27A (47, 32), whereas the SNARE-dependent fusion of these vesicles with the plasma membrane is reported to be dependent on vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 (VAMP7) (39). Accordingly, Rab27A and VAMP7 showed 61.7 and 72.5% colocalization with D52, respectively (Fig. 4, C and D, and Table 1). Finally, the lysosome-associated membrane protein LAMP1 exhibited a more modest but significant 39.7% colocalization with D52 (Fig. 4E and Table 1). Collectively, these results strongly support that the membrane-associated fraction of D52 is present within a lysosome-like secretory pathway.

D52 expression and Ca2+-stimulated phosphorylation directs LAMP1 accumulation at peripheral plasma membrane regions. Previous evidence that D52 modulates Ca2+-dependent secretion in pancreatic acinar cells (41) together with the apparent localization of D52 to a lysosome-like secretory pathway suggested that D52 may play a role in modulating lysosome secretion. CHO-K1, HeLA, and NRK cells are known to undergo Ca2+-stimulated lysosomal exocytosis in response to elevated Ca2+ (21). Thus a potential role for D52 in acutely modulating LAMP1 accumulation at the plasma membrane was investigated (Fig. 5). LAMP1 is a type 1 membrane protein with a highly glycosylated luminal domain that becomes exposed on the extracellular surface following exocytosis. Surface labeling of intact cells with antibodies directed against a luminal epitope of LAMP1 may be used to measure the exocytosis of LAMP1-containing vesicles at the plasma membrane (20, 21).

CHO-K1 cells overexpressing Wt-D52 and D52 phospho-mutants were incubated at 4°C with LAMP1 antibodies prior to fixation, permeabilization, and labeling for D52. When analyzed in reconstructed z-series images, high levels of LAMP1 surface labeling were detected under basal conditions in all cells overexpressing Wt-D52 or D52 phospho-mutants (Fig. 5A). Conversely, markedly less externalized LAMP1 was detected on adjacent cells containing low levels of D52, in agreement with previous studies showing that CHO-K1 cells normally exhibit minimal surface labeling of LAMP1 (20). Thus the enhanced expression of D52 or D52 phospho-mutants promotes LAMP1 accumulation at the cell surface. Cells overexpressing D52 were often multinucleated and enlarged with an expanded plasma membrane. This was particularly noted following expression of D52 phosphomimetic mutants.

Stimulation of cells with ionomycin enhanced LAMP1 surface labeling in all cells independent of D52 expression as previously described (21); however, in cells overexpressing Wt-D52, LAMP1 surface labeling was greatly elevated and particularly evident along peripheral membrane regions, clearly indicating an increase in plasma membrane accumulation of LAMP1 in response to elevated Ca2+. Similar to the effects of S136/A mutations to inhibit Ca2+-dependent accumulation of D52 at the plasma membrane (see Fig. 2), overexpression of S136/A failed to promote the extensive accumulation of LAMP1 along peripheral membrane regions following ionomycin treatment. Despite this, basal levels of external LAMP1 labeling over the cell surface in S136/A expressing cells did remain elevated compared with surrounding nontransfected cells. Strikingly, overexpression of D52 phosphomimetic mutants resulted in a marked enhancement of LAMP1 surface labeling especially at peripheral membrane regions that was independent of elevated Ca2+.

It is important to note that it was not possible to directly quantify changes in LAMP1 surface labeling by fluorescence activated cell sorting in D52 expressing cells since transfection efficiency was typically <20%. Moreover, we were unable to establish cloned cell lines with D52 or D52 mutants because transfected cells undergo high rates of apoptosis within 72 h. As an alternative, line density plots along cross sections of individual cells from multiple independent experiments were employed to quantify changes in LAMP1 staining at peripheral plasma membrane regions (Fig. 5A, right). When quantified as the relative pixel intensity within the first 20 pixels of the cell cross-sectional area, a >10-fold increase in peripheral LAMP1 staining was detected following Ca2+-elevation (Fig. 5B). Conversely, Ca2+-stimulated LAMP1 peripheral staining in cells expressing the S136/A mutants was abolished to basal levels. However, phosphomimetic mutation of D52 resulted in a constitutive enhancement of LAMP1 along peripheral regions that was not further augmented by ionomycin. In accordance with their pronounced colocalization, line density plots for D52 and externalized LAMP1 were nearly superimposable across individual cells.

Analysis of endogenous D52 and externalized LAMP1 in NRK cells provided results consistent with those seen following D52 overexpression in CHO-K1 cells although considerably greater excitation of the LAMP1 fluorophore was required for detection (Fig. 6). Under basal conditions, modest labeling of LAMP1 was present over the cell surface. Stimulation with either ionomycin or Lys3-bombesin resulted in a pronounced accumulation of externalized LAMP1 and intracellular D52 along peripheral membrane regions. Indeed, line density analysis of peripheral membrane regions of cells from multiple independent experiments showed an approximate threefold increase over basal levels of externalized LAMP1 following cell stimulation (Fig. 6B). Similar results for endogenous D52 and LAMP1 were also obtained in HeLa cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). As seen following D52-overexpression in CHO-K1 cells, overexpression of Wt- or D52 phospho-mutants in NRK cells strongly induced LAMP1 labeling at peripheral membrane regions in a Ca2+ and phosphorylation-regulated manner (Supplemental Fig. S2). Attempts to knock down D52 expression using siRNA were not fruitful as significant reduction in D52 expression resulted in cell death. In agreement with these findings, it was recently reported that knockdown of endogenous D52 in a prostate cancer cell line resulted in high rates of apoptosis (45).

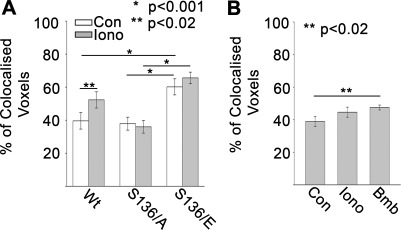

Extensive colocalization of intracellular D52 and externalized LAMP1. D52 and externalized LAMP1 demonstrated extensive colocalization when viewed at sequential depths of focus throughout the entire z-plane of cells (Supplemental Fig. S3). Quantification of surface-labeled LAMP1 containing voxels that overlapped with D52 in multiple reconstructed z-series images following overexpression in CHO-K1 cells revealed an ∼40% colocalization under basal conditions that was significantly increased to >50% with ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 7A). This ionomycin-mediated increase in externalized LAMP1 and D52 colocalization was not detected in S136/A-expressing cells, whereas cells expressing S136/E mutants showed a >70% colocalization of the proteins that was independent of ionomycin treatment. In accordance with these results, surface labeled LAMP1 in NRK cells showed an ∼40% colocalization with endogenous D52 under basal conditions that was modestly but significantly increased following Lys3-bombesin stimulation (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Colocalization of externalized LAMP1 and intracellular D52. The percent colocalized voxels of surfaced labeled LAMP1 with intracellular D52 was analyzed in multiple reconstructed z-series images in CHO-K1 cells transfected with D52 or D52 phospho-mutants (A) or NRK cells expressing endogenous D52 (B) (n ≥ 10 for each determination).

To ensure that these experiments measured surface labeling of LAMP1 and intracellular labeling of D52, CHO-K1 cells expressing Wt-D52 or D52 phosphomutants were acid washed following the 4°C incubation with LAMP1 antibodies and prior to fixation, permeabilization, and labeling for D52. Consistent with results in Fig. 5 extensive LAMP1 surface labeling was seen in D52-expressing cells that was further augmented with ionomycin treatment or expression of phosphomimetic mutants. Conversely acid washing prior to fixation resulted in a complete loss of LAMP1 immunoreactivity demonstrating that the LAMP1 antigens are in fact present on the cell surface (Fig. 8A). Likewise, to confirm that D52 immunoreactivity was not present on external regions of cells, D52 labeling was conducted in fixed cells before and after permeabilization (Fig. 8B). Results clearly demonstrated that access to the cytoplasm by plasma membrane permeabilization is essential to detect the D52 signal.

D52 overexpression enhances LAMP1 cycling to and from the plasma membrane. The ability of D52 expression and phosphorylation to regulate LAMP1 accumulation at the cell surface indicated an increase in LAMP1 trafficking to the plasma membrane and/or inhibition of LAMP1 retrieval back into the cytoplasm by endocytosis. To address this, D52-transfected CHO-K1 cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-LAMP1 antibodies and then stimulated or not with ionomycin for 5 min prior to acid washing to remove any external label, fixation, permeabilization, and labeling for D52 (Fig. 9). Identical to results for LAMP1 surface labeling, cells overexpressing Wt-D52 or phosphomutants massively internalized the LAMP1 antibodies compared with surrounding cells which incorporated little or no label. CHO-K1 cells are known to express <1–2% total cellular LAMP1 at the cell surface and therefore normally internalize only minimal amounts of LAMP1 antibodies under these conditions (20). Treatment of cells overexpressing Wt-D52 with ionomycin for 5 min prior to acid washing and fixation further intensified LAMP1 labeling immediately below peripheral plasma membrane regions, indicating an enhanced rate of endocytosis immediately prior to fixation. Likewise, expression of S136/E resulted in enhanced LAMP1 internalization just underneath the plasma membrane independent of cell stimulation, whereas the S136/A mutants, although demonstrating enhanced labeling in perinuclear regions compared with nontransfected cells, did not show this pronounced peripheral labeling in response to ionomycin treatment. Taken together, these data strongly support that D52 expression induces the trafficking of LAMP1 to and from the cell surface and further suggest that the Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of D52 at serine 136 significantly augments that process.

DISCUSSION

In proteomic screens, D52 was shown to be associated with AP-3-derived clathrin coated vesicles in HeLa (4) and PC12 cells (40). The significance of the AP-3 complex in mammalian systems was originally characterized on the basis of its role in directing the formation of lysosome-related organelles including melanosomes, platelet-dense granules, and lytic granules but has since emerged as an important component of the lysosomal-endosomal system in most cell types (reviewed in Ref. 15). The AP-3 complex plays a direct role in LAMP1 trafficking to lysosomes (25, 35). Unlike lysosomal cargo proteins, which interact with mannose-6-phosphate receptors and are delivered to lysosomes from the trans-Golgi via an AP-1-dependent pathway, LAMP1 trafficking to lysosomes occurs through a divergent pathway involving delivery from a trans-Golgi (20, 22) or post-Golgi endosomal tubular compartment (35, 22).

Normally only a small fraction of total cellular LAMP1 is present on the plasma membrane (20). However, cell stimulation leading to an elevation in cellular Ca2+ acutely induces the accumulation of LAMP1 at the plasma membrane via a lysosome-like secretory pathway (21, 29, 38). Plasma membrane-associated LAMP1 also increases significantly either when it is overexpressed by cellular transfection or following mutation of tyrosine or glycine residues in the cytoplasmic tail (20). Likewise, a loss of AP-3 β3A subunit in the mocha mouse (15) or knockdown of AP-3 expression (25) results in LAMP1 accumulation at the cell surface. Thus conditions in which functional AP-3 levels are diminished, either by overexpressing binding proteins or loss of AP-3 subunit expression, result in the accumulation of LAMP1 at the cell surface. It is therefore conceivable that D52 may inhibit AP-3 function on a trans-Golgi or post-Golgi compartment and thereby promote LAMP1 trafficking to the plasma membrane by a default pathway. However, we have not been successful in detecting a direct interaction between D52 and AP-3 subunits in solution by coimmunoprecipitation or GST-D52 pull-down assays. Moreover, of all the markers tested, D52 was most highly colocalized with both Rab27A and VAMP7 (see Fig. 4 and Table 1). Rab27A has been shown to regulate the trafficking and exocytosis of lysosome-related secretory granules in immune cells and melanocytes (47, 32) and also functions in insulin secretion from beta cells (30). Similarly, VAMP7 is present on lysosome-like secretory organelles and is the major v-SNARE regulating the final steps of lysosomal secretion from NRK cells, CHO-K1 cells (39), sympathetic neurons (1), and natural killer cells (28). Like LAMP1, VAMP7 has been shown to interact with AP-3 via a cytoplasmic longin domain that directs its trafficking to late endosomes (29). Taken together with the established secretory effects of D52 in acinar cells (41) as well as the pronounced colocalization of endogenous D52 and LAMP1 in NRK and HeLa cells, these results argue that the enhanced trafficking of LAMP1 to the plasma membrane following D52 overexpression and/or phosphorylation occurs within a lysosome-like secretory pathway rather than a default pathway.

Expression of the D52 S136/A mutant enhanced LAMP1 trafficking to the cell surface under basal conditions but failed to further promote LAMP1 surface labeling in response to elevated cellular Ca2+. Furthermore, phosphomimetic mutation of D52 constitutively augmented LAMP-1 surface labeling independent of cell stimulation (see Figs. 5 and 9). These data demonstrate that although D52 is active under basal conditions, Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation at serine 136 further activates lysosomal membrane trafficking and exocytosis. Indeed, the ability to monitor the effects of serine 136 phosphorylation on D52 and/or LAMP1 trafficking was directly dependent on D52 expression levels. When expressed at high levels, Wt-D52 and S136/A mutants clearly augmented LAMP1 plasma membrane trafficking under basal conditions. This was also seen when D52 was overexpressed in NRK cells, which normally contain high levels of endogenous protein (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Evidence that endogenous D52 in NRK, HeLa (see Fig. 2), polarized colonic mucosal T84 (23), or primary cultures of pancreatic acinar cells (43) undergoes a rapid and Ca2+-dependent accumulation at the apical plasma membrane that temporally coincides with its Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation at serine 136 strongly supports that phosphorylation is central to the functional significance of the protein.

The ability of D52 overexpression to enhance both surface labeling of LAMP1 as well as LAMP1's retrieval back to perinuclear regions, presumably lysosomes, supports that D52 not only augmented LAMP1 trafficking to the cell surface but may also modulate LAMP1 endocytosis. We were unable to directly image D52 translocation to the cell surface. Thus it is uncertain whether D52, which is highly soluble, is recruited from cytoplasmic pools to sites of LAMP1 exocytosis or translocates on LAMP1-positive secretory vesicles. Colocalization of D52 with AP-3 as well as its purification from AP-3 derived clathrin coated vesicles (4) may suggest that, rather than directly modulating exocytosis, D52 participates in lysosome-like vesicle formation from a post-Golgi compartment and acts in a similar way to mediate endocytic retrieval from the plasma membrane. Interestingly, D52 has been shown to directly interact with annexin VI (42, 44), which has been implicated in CCV formation and post-Golgi trafficking. On the other hand, the D52 ortholog D53 has been shown to directly interact with SNARE proteins that participate in the final stages of membrane fusion. Thus it is uncertain whether D52 modulates vesicle formation and/or exocytosis in regulating lysosomal membrane trafficking.

The lack of colocalization of D52 and with LysoTracker was somewhat surprising given the abundant colocalization with LAMP1. LysoTracker fluorescence is sensitive to acidic cellular compartments. The signal intensity achieved with LysoTracker was greatly diminished compared with LAMP1, potentially suggesting that LysoTracker identified a subset of mature lysosomes with extremely low pH but is not as sensitive to the lysosome-like secretory pathway. Interestingly, total cellular LAMP1 and D52 showed an ∼49% and endocytosed FITC-dextran a 36% colocalization with D52 (see Table 1). This less-than-complete colocalization, particularly compared with VAMP7 and Rab27A, may suggest that D52, VAMP7, and Rab27A represent a hybrid population of lysosome-like secretory organelles that are destined for the cell surface and that are distinct from more conventional lysosomes.

Identification of serine 136 as the major Ca2+-regulated phosphorylation site in D52 revealed that it falls within the minimal consensus sequence for phosphorylation by CKII (SXXE/D) (27). Previous reports that D52 is a substrate for CaM kinase II, although derived in vitro, were clearly supported by the Ca2+-dependence of its phosphorylation in cells (34, 23). We reported that D52 is more highly phosphorylated by CKII than CaM kinase II in vitro; however, comparison of phosphopeptide maps of recombinant D52 phosphorylated in vitro and endogenous D52 phosphorylated in intact T84 cells suggested that CaM kinase II and not CKII was the endogenous kinase (23). Despite these findings, D52 phosphorylation in cells was found to be resistant to inhibition by classical CaM kinase II inhibitors and calmodulin antagonists (23). Within D52, serine 100 lies in the minimal consensus sequence (K/RXXS) for phosphorylation by CaM kinase II (14). Surprisingly, mutation of serine 100 to alanine had no effect on basal or Ca2+-stimulated phosphorylation (data not shown). Chew et al. (11) recently reported that D52 phosphorylation occurs at S136 and provide additional evidence that it is likely to be mediated by a unique delta6 isoform of CaM kinase II, suggesting that this enzyme may play an important role in regulating D52 secretory function in exocrine epithelia.

The ability of D52 to modulate a lysosome-like secretory pathway in cultured cells is in agreement with our previous results that introduction of recombinant D52 into permeabilized pancreatic acinar cells following depletion of the endogenous protein acutely augments Ca2+-stimulated digestive enzyme secretion (41). Curiously, in acinar cells, D52 does not colocalize by immunofluorescence microscopy or copurify with mature zymogen secretory granules (43) but rather moves to the plasma membrane either from a cytosolic pool or on a parallel vesicular pathway upon secretagogue stimulation. Findings that D52 localizes to a lysosome-like secretory pathway and promotes lysosomal membrane protein exocytosis may indicate that D52 modulates a similar pathway in acinar cells. Such a pathway could be of major significance as the abnormal trafficking of digestive proteases and lysosomal hydrolases is thought to initiate the early stages of acute pancreatitis and occurs within unique compartment that is peripheral to mature zymogen granules in the apical cytoplasm (33). Clearly further investigation into the potential of a lysosome-like secretory pathway in acinar cells is warranted.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK07088 and USDA HATCH grant to G. E. Groblewski.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We extend thanks to W. Bement and T. Martin for helpful suggestions on this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arantes RM, Andrews NW. A role for synaptotagmin VII-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes in neurite outgrowth from primary sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 26: 4630– 4637, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashrafi K, Chang FY, Watts JL, Faser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Ruvkun G. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature 421: 268–272, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bard F, Casano L, Mallabiabarrena A, Wallace E, Saito K, Kitayama H, Guizzunti G, Hu Y, Wendler F, DasGupta R, Perrimon N, Malhotra V. Functional genomics reveals genes involved in protein secretion and Golgi organization. Nature 439: 604–607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borner GHH, Harbour M, Hester S, Lilley KS, Robinson MS. Comparative proteomics of clathrin-coated vesicles. J Cell Biol 175: 571–578, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutros R, Bailey AM, Wilson SHD, Byrne JA. Alternative splicing as a mechanism for regulating 14-3-3 binding: interactions between hD53 (TPD52L1) and 14-3-3 proteins. J Mol Biol 332: 675–687, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutros R, Fanayan S, Schehata M, Byrne JA. The tumor protein D52 family: many pieces, many puzzles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 325: 1115–1121, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutros R, Byrne JA. D53 (TPD52L1) is a cell cycle-regulated protein maximally expressed at the G2-M transition in breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res 310: 152–165, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne JA, Tomasetto C, Garnier JM, Rouyer N, Mattei MG, Bellocq JP, Rio MC, Basset P. A screening method to identify genes commonly overexpressed in carcinomas and the identification of a novel complementary DNA sequence. Cancer Res 55: 2896–2903, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne JA, Nourse CR, Basset P, Gunning P. Identification of homo- and heteromeric interactions between members of the breast carcinoma-associated D52 protein family using the yeast two-hybrid system. Oncogene 16: 873–881, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SL, Maroulakou IG, Green JE, Romano-Spica V, Modi W, Lautenberger J, Bhat NK. Isolation and characterization of a novel gene expressed in multiple cancers. Oncogene 12: 741–751, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew CS, Chen X, Zhang H, Berg EA, Zhang H. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of tumor protein D52 on serine 136 may be mediated by CAMK2δ6. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G1159–G1172, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho S, Ko H, Kim J, Lee J, Park J, Jang M, Park SG, Lee DH, Ryu S, Park B. Positive regulation of apoptosis signal-regulation kinase 1 by hD53L1. J Biol Chem 279: 16060–10656, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffer A, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Bombesin receptor from Swiss 3T3 cells. Affinity chromatography and reconstitution into phospholipid vesicles. FEBS Lett 275: 159–164, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colbran RJ, Schworer CM, Hashimoto Y, Fong YL, Rich DP, Smith MK, Soderling TR. Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J 258: 313–325, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell'Angelica EC, Shotelersuk V, Aguilar RC, Gahl WA, Bonifacino JS. Altered trafficking of lysosomal proteins in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome due to mutations in the beta 3A subunit of the AP-3 adaptor. Mol Cell 3: 11–21, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Marco MC, Martín-Belmonte F, Kremer L, Albar JP, Correas I, Vaerman JP, Marazuela M, Byrne JA, Alonso MA. MAL2, a novel raft protein of the MAL family, is an essential component of the machinery for transcytosis in hepatoma HepG2 cells. J Cell Biol 159: 37–44, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groblewski GE, Wishart MJ, Yoshita M, Williams JA. Purification and identification of a 28-kDa calcium-regulated heat-stable protein. A novel secretagogue-regulated phosphoprotein in exocrine pancreas. J Biol Chem 271: 31502–31507, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groblewski GE, Yoshida M, Yao H, Williams JA, Ernst SA. Immunolocalization of CRHSP-28 in exocrine digestive glands and gastrointestinal tissues of the rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G219–G226, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groblewski GE, Yoshida M, Bragado JM, Leykam J, Williams JA. Purification and characterization of a novel calcineurin substrate in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 273: 22738–22744, 1998b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harter C, Mellman I. Transport of lysosomal membrane protein lgp120 (lgp-A) to lysosomes does not require appearance on the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 117: 311–325, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaiswal JK, Andrews NW, Simon SM. Membrane proximal lysosomes are the major vesicles responsible for calcium-dependent exocytosis in nonsecretory cells. J Cell Biol 159: 625–635, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janvier K, Bonifacino JS. Role of the endocytic machinery in the sorting of lysosome-associated membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell 16: 4231–4242, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaspar KM, Thomas DDH, Taft WB, Takeshita E, Weng N, Groblewski GE. CaM kinase II regulation of CRHSP-28 phosphorylation in cultured mucosal T84 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G1300–G1309, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaspar KM, Thomas DDH, Weng N, Groblewski GE. Dietary and hormonal stimulation of rat exocrine pancreatic function regulates CRHSP-28 phosphorylation in vivo. J Nutr 133: 3073–3075, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Borgne R, Alconada A, Bauer U, Hoflack B. The mammalian AP-3 adaptor-like complex mediates the intracellular transport of lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 273: 29451–29461 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis JD, Payton LA, Whitford JG, Byrne JA, Smith DI, Yang L, Bright RK. Induction of tumorigenesis and metastasis by the murine orthologue of tumor protein D52. Mol Cancer Res 2: 133–144, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J 369: 1–15, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcet-Palacios M, Odemuyiwa SO, Coughlin JJ, Garofoli D, Ewen C, Davidson CE, Ghaffari M, Kane KP, Lacy P, Logan MR, Befus AD, Bleackley RC, Moqbel R. Vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 (VAMP-7) is essential for target cell killing in a natural killer cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 366: 617–623, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Arca S, Rudge R, Vacca M, Raposo G, Camonis J, Proux-Gillardeaux V, Daviet L, Formstecher E, Hamburger A, Filippini F, D'Esposito M, Galli T. A dual mechanism controlling the localization and function of exocytic v-SNAREs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9011–9016, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrins MJ, Stuenkel EL. Kinetics of Rab27a-dependent actions on vesicle docking and priming in pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol 586: 5367–5381, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez I, Chakrabarti S, Hellevik T, Morehead J, Fowler K, Andrews NW. Synaptotagmin VII regulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 148: 1141–1149, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MénaschÉ G, Ménager MM, Lefebvre JM, Deutsch E, Athman R, Lambert N, Mahlaoui N, Court M, Garin J, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G. A newly identified isoform of Slp2a associates with Rab27a in cytotoxic T cells and participates to cytotoxic granule secretion. Blood 112: 5052–5062, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otani T, Chepilko SM, Grendell JH, Gorelick FS. Codistribution of TAP and the granule membrane protein GRAMP-92 in rat caerulein-induced pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G999–G1009, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parente JA, Jr., Goldenring JR, Petropoulos AC, Hellman U, Chew CS. Purification, cloning, and expression of a novel, endogenous, calcium-sensitive, 28-kDa phosphoprotein. J Biol Chem 271: 20096–20101, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peden AA, Oorschot V, Hesser BA, Austin CD, Scheller RH, Klumperman J. Localization of the AP-3 adaptor complex defines a novel endosomal exit site for lysosomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 164: 1065–1076, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proux V, Provot S, Felder-Schmittbuhl MP, Laugier D, Calothy G, Marx M. Characterization of a leucine zipper-containing protein identified by retroviral insertion in avian neuroretina cells. J Biol Chem 271: 30790–30797, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proux-Gillardeaux V, Galli T, Callebaut I, Mikhailik A, Calothy G, Marx M. D53 is a novel endosomal SNARE-binding protein that enhances interaction of syntaxin 1 with the synaptobrevin 2 complex in vitro. Biochem J 370: 213–221, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez A, Webster P, Ortego J, Andrews NW. Lysosomes behave as Ca2+-regulated exocytic vesicles in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 137: 93–104, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao SK, Huynh C, Proux-Gillardeaux V, Galli T, Andrews NW. Identification of SNAREs involved in synaptotagmin VII-regulated lysosomal exocytosis. J Biol Chem 279: 20471–20479, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salazar G, Craige B, Wainer BH, Guo J, DeCamilli P, Faundez V. Phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase type II alpha is a component of adaptor protein-3-derived vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3692–3704, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas DDH, Taft WB, Kaspar KM, Groblewski GE. CRHSP-28 regulates Ca2+-stimulated secretion in permeabilized acinar cells. J Biol Chem 276: 28866–28872, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas DDH, Kaspar KM, Taft WB, Weng N, Rodenkirch LA, Groblewski GE. Identification of Annexin VI as a Ca2+-sensitive CRHSP-28-binding protein in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem 277: 35496–35502, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas DDH, Weng N, Groblewski GE. Secretagogue-induced translocation of CRHSP-28 within an early apical endosomal compartment in acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G253–G263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiacci E, Orvietani PL, Bigerna B, Pucciarini A, Corthals GL, Pettirossi V, Martelli MP, Liso A, Benedetti R, Pacini R, Bolli N, Pileri S, Pulford K, Gambacorta M, Carbone A, Pasquarello C, Scherl A, Robertson H, Sciurpi MT, Alunni-Bistocchi G, Binaglia L, Byrne JA, Falini B. Tumor protein D52 (TPD52): a novel B-cell/plasma-cell molecule with unique expression pattern and Ca2+-dependent association with annexin VI. Blood 105: 2812–2820, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ummanni R, Teller S, Junker H, Zimmermann U, Venz S, Scharf C, Giebel J, Walther R. Altered expression of tumor protein D52 regulates apoptosis and migration of prostate cancer cells. FEBS J 275: 5703–5713, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson SHD, Bailey AM, Nourse CR, Mattei MG, Byrne JA. Identification of MAL2, a novel member of the mal proteolipid family, though interactions with TPD52-like proteins in the yeast two-hybrid system. Genomics 76: 81–88, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson SM, Yip R, Swing DA, O'Sullivan TN, Zhang Y, Novak EK, Swank RT, Russell LB, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. A mutation in Rab27a causes the vesicle transport defects observed in ashen mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 7933–7938, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.