Abstract

Recently, we identified, for the first time, two-pore channels (TPCs, TPCN for gene name) as a novel family of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-gated, endolysosome-targeted calcium release channels. Significantly, three subtypes of TPCs have been characterized, TPC1-3, with each being targeted to discrete acidic calcium stores, namely lysosomes (TPC2) and endosomes (TPC1 and TPC3). That TPCs act as NAADP-gated calcium release channels is clear, given that NAADP binds to high- and low-affinity sites associated with TPC2 and thereby induces calcium release and homologous desensitization, as observed in the case of endogenous NAADP receptors. Moreover, NAADP-evoked calcium signals via TPC2 are ablated by short hairpin RNA knockdown of TPC2 and by depletion of acidic calcium stores with bafilomycin. Importantly, however, NAADP-evoked calcium signals were biphasic in nature, with an initial phase of calcium release from lysosomes via TPC2, being subsequently amplified by calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In marked contrast, calcium release via endosome-targeted TPC1 induced only spatially restricted calcium signals that were not amplified by CICR from the ER. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms that cells may utilize to “filter” calcium signals via junctional complexes to determine whether a given signal remains local or is converted into a propagating global signal. Essentially, endosomes and lysosomes represent vesicular calcium stores, quite unlike the ER network, and TPCs do not themselves support CICR or, therefore, propagating regenerative calcium waves. Thus “quantal” vesicular calcium release via TPCs must subsequently recruit inositol 1,4,5-trisphoshpate receptors and/or ryanodine receptors on the ER by CICR to evoke a propagating calcium wave. This may call for a revision of current views on the mechanisms of intracellular calcium signaling. The purpose of this review is, therefore, to provide an appropriate framework for future studies in this area.

Keywords: two-pore segment channel, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate, sarco (endo)plasmic reticulum, lysosome

Diverse Ca2+ Signaling Pathways in Animal Cells

not only are there preprogrammed paths for most cells, but the ever-changing environment also provides instructions so that the cells can adjust their growth patterns and activities and ultimately make life or death decisions. Cells are thus exposed to both intrinsic and extrinsic signals in the form of chemical and/or physical factors that are presented to them from either side of the plasma membrane. These signals are converted into intracellular messengers through the actions of receptors, ion channels, and/or effector enzymes. Among these messengers, calcium ions (Ca2+) are of fundamental importance to signal transduction in animal cells. Unlike many other cellular messengers, Ca2+ cannot be made by de novo synthesis, nor is it degraded into an inactive product. Cells control intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) by segregation. In the cytoplasm, [Ca2+]i is maintained at ∼50–100 nM at rest by the actions of Ca2+-ATPases, which are present on both the plasma membrane and the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum (S/ER), the largest (in most cell types) and classical intracellular Ca2+ store. The plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases (19) pump Ca2+ from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space, while the S/ER Ca2+-ATPases (SERCA) (104) transfer cytoplasmic Ca2+ from the cytoplasm into the S/ER lumen, with storage capacity enhanced by the luminal Ca2+ binding proteins, such as calreticulin and calsequestrin (39). In addition, the presence of a number of high-affinity, cytoplasmic Ca2+-binding proteins (e.g., calbindin, parvalbumin) (91) help buffer the free [Ca2+] at basal levels. Mitochondria also take up Ca2+ from the cytoplasm (87), which serves both as a Ca2+ extrusion mechanism and a way to regulate, for example, Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and thereby mitochondrial function (57). The above mechanisms not only help keep the cytoplasmic Ca2+ level at bay so that any increase from basal levels can be read as a signal of metabolic or environmental change, but also limit the free diffusion of Ca2+ so that the Ca2+ signals remain local, unless a given threshold for initiation of a propagating, global Ca2+ wave is breached (30).

For the most part, a rise in [Ca2+]i is brought about by the opening of Ca2+-permeable channels. There are many different types of such channels, which are expressed in a cell type-dependent manner, and each cell possesses multiple types of Ca2+-permeable channels. Some are expressed on the plasma membrane and are responsible for Ca2+ influx into cytoplasm from the extracellular space [e.g., voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (106) and store-operated channels (20, 63)]. Others are expressed on the membranes of intracellular organelles, such as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3Rs) (11) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (32), the archetypal intracellular Ca2+ release channels, which are primarily targeted to the S/ER membranes. Here they serve to release Ca2+ from S/ER Ca2+ stores, and, in each case, receptor function can be regulated by Ca2+ via the process of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) (70).

With advances in both time and spatial resolution, Ca2+ imaging studies have revealed diverse patterns of intracellular Ca2+ release events that reflect highly localized and discrete Ca2+ signals that either function as such or are subsequently converted into large, propagating waves that may, or may not, cross the entire cell. On the basis of size and kinetics, a number of distinct intracellular Ca2+ release events have been characterized and referred to as Ca2+ puffs, sparks, sparklets, and syntillas, to name but a few (10, 103). In general, these local Ca2+ release events have been presumed to emanate from RyR (92) and/or IP3R (97) clusters located on the S/ER, with conversion into global Ca2+ signals being dependent on the recruitment by CICR of distant clusters of common receptor populations. However, our recent studies have unveiled a new family of Ca2+ release channels that are localized, not on the S/ER, but on endosomes and lysosomes (21), which, because of the relatively low pH in their lumen, are often referred to as acidic organelles. It is significant, therefore, that lysosome-related organelles represent an additional, releasable Ca2+ store that may have been established before prokaryotes and eukaryotes diverged (73). That Ca2+ release channels may be specifically targeted to endolysosomes suggests, therefore, that Ca2+ may be released from these stores to produce local signals and that endolysosomes have the capacity to induce global signals, if they are able to couple to the S/ER via CICR.

The Two-pore Channels

Analysis across many vertebrate species identified three genes that encoded two-pore segment channels (TPCs or TPCNs for gene name). TPCs are so named because, in their predicted primary protein sequences (Fig. 1), there are clearly two putative pore-forming repeats (21, 41). Each of these repeats contains six transmembrane segments and an intervening pore-loop (i.e., there are 12 transmembrane segments and two pore-loops in total), an architecture common to many voltage-gated channels (106). Indeed, the transmembrane regions of TPCs are homologous to that of VGCCs and voltage-gated Na+ channels, TRP channels, and several other cation channels (106). However, unlike these related channels, we demonstrated that TPCs are not expressed on the plasma membrane. In fact, when stably overexpressed in human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK-293) cells it was evident that the main sites of their expression were localized to endolysosomes, with human TPC1 and chicken TPC3 closely associated with different subpopulations of endosomes and human TPC2 mainly localized to lysosomes (Fig. 2) (21).

Fig. 1.

Intracellular location, membrane topology, and sequence homology of two-pore channels (TPCs). A: diagram of acidic organelle depicting the function of vacuolar (V) H+-ATPase, putative Ca2+/H+ exchanger, and TPC2. TPC2 is enlarged to show predicted transmembrane organization of TPCs based on hydrophobicity analysis and membrane orientation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. P loop, pore loop; NAADP, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate. B: pairwise comparison of amino acid identities at different domains of TPCs. NH2-termini (N-ter), COOH-termini (C ter), and transmembrane (TM) repeats are indicated. Note: higher homology is found at TM segments 4–6, but, overall, the three TPCs are quite distant from each other.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation depicts the targeting, in human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK-293) cells, of human TPC1 and chicken TPC3 to different endosome populations, and of human TPC2 to lysosomes, and the functional role of these acidic organelles. SOC and ROC, store- and receptor-operated channel, respectively; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel; TGN, trans-Golgi network. [Adapted from Luzio et al. (62)].

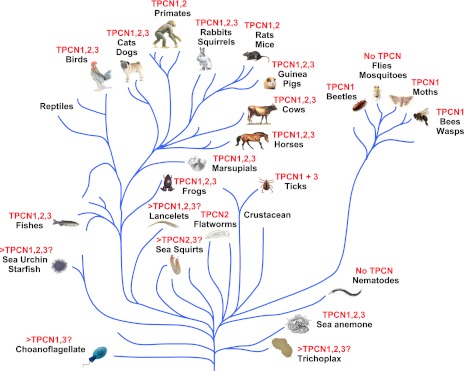

It is notable, however, that, across the animal phyla, the genes encoding TPC1 (TPCN1), TPC2 (TPCN2), and TPC3 (TPCN3) are not always expressed. Most significantly, the gene encoding TPC3 (TPCN3) is absent in mice, rats, and primates, while being present in most other mammals (21). The lack of TPCN3 in humans, chimps, mice, and rats is clearly evident upon inspection of the genomic sequences, which are complete for these species. However, the evolutionary path(s) that may have led to the deletion of the TPCN3 gene is unclear, although it is likely that this would have occurred independently in rodents and primates. Thus, while the entire gene is missing in mice and rats, a search of the incomplete genomic sequences of other rodents suggests the existence of the TPCN3 gene in squirrels and guinea pigs (Fig. 3). For humans and chimps, although sequences coding for the NH2-terminal third of TPC3 can be found in the completed genomes, there are stop codons in the sequences that render them pseudogenes. Despite this fact, the first one-half of the remaining human TPCN3 sequence appears to be frequently transcribed, as shown by its high abundance in the expressed sequence tag database. This may be an evolutionary artifact, or serve an as yet unidentified physiological role. Whatever the case, the loss of the later two-thirds of TPCN3 in the genomes of high primates must be a relatively recent event, as the full-length TPCN3 is present in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). However, based on the incomplete genome data available to date, the monkey TPCN3 gene is unlikely to encode a functional protein due to the lack of intron acceptor and donor sequences in many areas and the presence of multiple stop codons in the presumed coding regions, according to the alignment with other mammalian TPC3 proteins.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram depicts partial family trees from the animal kingdom and identifies key examples of species in which the genes encoding TPC1, TPC2, and TPC3 are absent or present. “>” denotes possible presence of additional TPCs.

The absence of TPC3 may point to functional redundancy, likely due to the development of other channels that may contribute equally well to its functional niche, thus rendering TPC3 redundant in a species-dependent manner. Alternatively, it may simply be that, to choose two closely related species, rabbits express TPC3 to regulate endosomal functions that are not required by rats. More detailed consideration of this matter may, therefore, not only provide for advances in our understanding of the role of TPCs, but on the regulated functions of endosomes and lysosomes. In this respect, it may be worth considering further why species (Fig. 3) such as honeybees and silkworms contain only TPC1 encoding genes (TPCN1), whereas C. elegans and D. melanogaster do not appear to contain any of the “available” sequences encoding TPCs (21). Furthermore, the complete genomic sequences of two sea squirt species, Ciona savignyi and Ciona intestinalis, contain only TPCN2 and TPCN3, but no TPCN1; interestingly, the intronless feature of the TPCN2 sequences suggests that, in this genus, the TPCN2 gene might have been acquired later in evolution through perhaps a retroviral mediated process. Conversely, sequences for TPCN1 and TPCN3, but not TPCN2, are found in choanoflagellates, so why no TPCN2? Whatever the case, these observations suggest that, although the genes encoding TPCs appear to be from an ancient gene family, the absence of one or more TPC subtypes (including a complete absence of TPCs) from a number of species appears to indicate that TPCs represent an important ion channel family that is not always essential for cell survival.

TPCs Mediate NAADP-Evoked Ca2+ Release From Endolysosome Stores

The sequence homology with Ca2+ channels and other cation channels suggests that, in all likelihood, TPCs represent Ca2+-permeable channels. Moreover, that they are specifically targeted to endolysosomes and not the S/ER or the plasma membrane is indicative of a role in Ca2+ release from these acidic organelles. Our initial findings, therefore, led to the consideration of, perhaps, the most detailed studies on Ca2+ release from acidic organelles in animal cells, namely those that have focused on the actions of a relatively new Ca2+ mobilizing second messenger, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) (52). NAADP is thought to be generated by a base-exchange reaction that replaces the nicotinamide moiety of β-NADP+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) with nicotinic acid in a manner that is catalyzed by ADP-ribosyl cyclases (e.g., CD38) (2, 51). Significantly, with respect to CICR, certain ADP-ribosyl cyclases are also capable of synthesizing, from β-NAD+, cADP ribose (53), a second messenger that may trigger S/ER Ca2+ release via RyRs or modulate the Ca2+ sensitivity of RyRs (33).

Since its discovery, it has been apparent that NAADP is the most potent of all Ca2+ mobilizing messengers, with a threshold for induction of intracellular signals in the low nanomolar range. Moreover, some of the earliest investigations into its mechanism of action suggested that NAADP does not mobilize Ca2+ from the same stores as those targeted by IP3 and cADPR, i.e., it releases Ca2+ from a store other than the S/ER (35, 54, 55). Thereafter, an observation that was to be pivotal to the direction of our subsequent studies on TPCs was that NAADP specifically released Ca2+ from reserve granules in sea urchin eggs, which are lysosome-like acidic organelles (26). That NAADP did indeed mobilize Ca2+ from acidic lysosome-related stores was then confirmed in a variety of mammalian cell types (16, 47, 69, 79, 98, 105, 108). This was demonstrated primarily by the fact that NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signals were blocked following depletion of acidic Ca2+ stores by preincubation with the vacuolar-H+-ATPase inhibitors bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A, and/or by preincubation with glycylphenylalanine 2-naphthylamide (GPN). It is thought that the vacuolar-H+-ATPase inhibitors deplete the endolysosomal Ca2+ content via disruption of the pH gradient across these acidic organelles that is required for Ca2+ uptake (24) via a putative Ca2+/H+ exchanger (Fig. 1) (73), akin to the mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ antiporter Letm1 (42). By contrast GPN, a substrate of the lysosome-specific exopeptidase cathepsin C, causes osmotic rupture of lysosomes due to accumulation of its amino acid products that are unable to exit the organelles (9). Whatever their precise mechanism of action, these drugs render the acidic Ca2+ stores incapable of supporting NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release. By contrast, the aforementioned studies on NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signaling have also shown that depletion of S/ER stores by preincubation with the SERCA pump inhibitor thapsigargin fails to block, at least entirely, Ca2+ signaling in response to NAADP. Moreover, removal of acidic stores with bafilomycin/concanamycin or GPN was found to be without effect on Ca2+ release from the S/ER via RyRs and/or IP3Rs. Thus, together, these agents are considered to be sufficient to distinguish between components of intracellular Ca2+ signaling that may rely on acidic and S/ER Ca2+ stores, respectively.

Consistent with their sequence homology to Ca2+ channels and targeting to acidic endolysosome Ca2+ stores, we provided the first evidence that TPCs constitute a family of NAADP receptors that mediate Ca2+ release from acidic organelles upon activation by NAADP (21). That this is the case received strong support from the finding that intracellular membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably overexpressing human TPC2 displayed increased specific [32P]NAADP binding compared with wild-type HEK-293 cells. Consistent with [32P]NAADP binding to endogenous receptors on membranes derived from mouse liver, the tissue in which TPC2 is most highly expressed and in which lysosomes are enriched, recombinant TPC2 exhibited a high-affinity site with a dissociation constant of ∼5 nM and a low-affinity site with a dissociation constant of ∼10 μM. Furthermore, intracellular dialysis of 10 nM NAADP (from a patch pipette in the whole cell configuration) evoked marked and global Ca2+ signals in HEK-293 cells that stably overexpressed TPC2, but proved ineffective when introduced into untransfected HEK-293 cells until 100-fold higher concentrations of NAADP were introduced. Moreover, NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signals were abolished following depletion of acidic stores with bafilomycin and by short hairpin RNA knockdown of TPC2 expression. In an effort to confirm these findings, we not only introduced defined concentrations of NAADP by intracellular dialysis, but thereafter in the same way we introduced caged NAADP (56) into the cells and released NAADP in a controlled manner by flash photolysis. Under both conditions, TPC2-overexpressing cells exhibited robust, global, and bafilomycin-sensitive Ca2+ signals in response to NAADP. Whatever the method of introduction used, it was notable that the NAADP-evoked Ca2+ transients in TPC2-overexpressing cells exhibited two phases: an initial burst of Ca2+ release that was followed by a secondary, larger, and robust Ca2+ transient (Fig. 4). Strikingly, wild-type HEK-293 cells exhibited only small and highly localized Ca2+ signals, which were observed less frequently even when a 100-fold higher concentration of NAADP was used. By careful intracellular dialysis of defined concentrations of NAADP, we were able to show that the threshold for induction by NAADP of a biphasic Ca2+ signal in TPC2-overexpressing cells was ∼10 nM, consistent with the Kd for NAADP at the high-affinity binding site. Moreover, increasing the concentration of NAADP presented to the cell led to a reduction in the delay, following initiation of intracellular dialysis, to onset of the Ca2+ transient, as one might expect for a ligand-gated process. Importantly, however, intracellular dialysis of 1 mM NAADP failed to elicit a Ca2+ transient, which is indicative of homologous self-inactivation of the Ca2+ release process by NAADP (1, 34, 54). Thus our findings provide further support for the view that a high-affinity binding site on the NAADP receptor/TPC2 may confer channel opening, while a low-affinity site may confer inactivation/desensitization. All things considered, it would appear that TPC2 represents at least the primary component of an NAADP-gated, lysosome-targeted Ca2+ release channel that is neither activated nor inhibited by Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

Record depicts the relative contribution to NAADP-evoked global Ca2+ waves of quantal Ca2+ release from lysosomal stores via TPC2 and that provided by subsequent amplification by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum (S/ER). ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

Do Members of the TRP Channel Family Act as NAADP Receptors?

Recently, members of the TRP channel family have been implicated in the regulation of acidic Ca2+ stores. First, mucolipin 1, or TRPML1, which is also a lysosome-bound Ca2+-permeable channel, was proposed to function as an NAADP receptor (107). However, it has been shown that, in normal rat kidney cells, overexpression of TRPML1 fails to increase NAADP binding (86). Other groups have also suggested that the primary function of TRPML1 is to act either as an Fe2+ or a H+ release channel (29, 93). Likewise, the related TRPML2 and TRPML3 are also lysosomal resident channels (101), although the expression of these channels is restricted to certain cell types, and there is no evidence to suggest that these channels are involved in NAADP signaling. It is also notable that TRPM2 has been shown to be expressed, not only on the plasma membrane to mediate Ca2+ influx, but also in the lysosomal compartment to cause Ca2+ release (50). This channel can be activated by NAADP and related nucleotides, but, in the case of NAADP, the concentration required to induce Ca2+ release (6) is much higher (1,000-fold) than that required to elicit Ca2+ signals from endogenous NAADP receptors or TPC2 (see above). Moreover, TRPM1 has a prevalent expression in intracellular vesicles, including the lysosome-related melanosomes of melanocytes (77), although it has not been proposed to function as an NAADP receptor. Nonetheless, despite the limited evidence with respect to their regulation by NAADP, it is quite possible that members of the TRP channel family also mediate Ca2+ release from acidic organelles.

Cross Talk Between Acidic Stores and the S/ER Network May Shape the Overall Ca2+ Signals Emanating From TPCs

To further investigate the nature of Ca2+ signaling via recombinant TPC2 when stably expressed in HEK-293 cells, we considered the possible contribution to observed responses of acidic stores and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), respectively, due to the fact that NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release from acidic stores may be amplified by inducing CICR via the S/ER in a variety of wild-type cells (23). Thus the impact upon the biphasic NAADP-evoked Ca2+ transient of depleting 1) acidic stores by inhibition of the vacuolar-H+-ATPases by bafilomycin, and 2) ER stores by inhibition of SERCA by thapsigargin was carefully assessed. Consistent with most recent studies on NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signals, the former intervention completely abolished all NAADP-evoked responses, whatever the method of application used. The latter, however, only eliminated the secondary phase (21), suggesting that both the acidic and the ER stores are involved in the overall response to NAADP, as one might expect. Moreover, our studies, like previous investigations on NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signaling via lysosome-related stores (13, 47), identified that Ca2+ release from acidic stores via TPC2 was essential for the initial, localized Ca2+ signals triggered by NAADP, and that these Ca2+ bursts were a prerequisite for the marked, secondary rise in [Ca2+]i that arose due to subsequent amplification by induction of CICR from ER stores (Fig. 4). This was confirmed by the observation that an IP3R blocker, heparin, completely inhibited the secondary [Ca2+]i increase without affecting the initial “pacemaker” phase, much like thapsigargin. Consistent with the finding that functional RyRs are not present in HEK-293 cells (3), coapplication of heparin and ryanodine had no further effect over and above that seen with heparin alone. Thus, in HEK-293 cells stably overexpressing TPC2, the Ca2+ signals generated in response to NAADP are composed of at least two components: an initial, spatially restricted burst of Ca2+ from lysosome-related stores that is subsequently amplified by CICR from the ER via IP3Rs.

At this point, it is worth considering, once more, TPC1. While we found TPC2 to be specifically targeted to lysosomes, TPC1 was, by contrast, specifically targeted to endosomes, with little or no association with lysosomes, the ER, the Golgi apparatus, or mitochondria (21). It should be noted, however, that such specific targeting of either TPC1 or TPC2 was not observed when transient overexpression was used (unpublished observation). In fact, the use of this latter technique led to erroneous targeting of TPCs to a wide variety of organelles and in a manner that could possibly cloud interpretation of “functional” outcomes, compared with observations made by way of stable overexpression. Using only stable overexpression in HEK-293 cells, our preliminary investigations on NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signaling via human TPC1 revealed not global, biphasic Ca2+ transients, but small and highly localized Ca2+ release events (at least to the level of resolution we achieved with our recording system; see supplementary information of Ref. 21). In fact, the Ca2+ signals evoked by NAADP via TPC1 were very similar in magnitude to the Ca2+ bursts triggered by NAADP via stably overexpressed TPC2 either 1) before initiation of a global Ca2+ wave, 2) following depletion of ER stores with thapsigargin, or 3) following block of IP3Rs with heparin. In short, our initial studies suggest that Ca2+ signals that arise from endosomal targeted TPC1 fail to couple to the ER via CICR. This observation is consistent with the fact that TPC1 and the endosomal vesicles to which it is targeted (under the conditions of our experiments) exhibit a far more restricted distribution in HEK-293 cells, and this may point to a role in the generation of local, rather than global, Ca2+ signals (21). This raises the possibility that TPC1 may function, at least in some cell types, to specifically regulate endosome function and in a manner that does not interfere with or compromise the regulation of primary cell function (e.g., muscle contraction).

Following discussions with others, a unilateral decision was made to assess our experimental observations (15). While confirmatory, subtle differences were evident with respect to both the distribution of TPCs and Ca2+ signaling. Colocalization studies suggested that transient overexpression of TPC1 in Xenopus Laevis oocytes and SKBR3 cells may result in a wider distribution of this channel than observed by us. Thus, in SKBR3 cells, TPC1 appeared to be targeted not to endosomes alone, but to lysosomes, endosomes, and the ER; by contrast, and consistent with our findings, TPC2 appeared to be specifically targeted to lysosomes. Furthermore, microinjection of a bolus volume of 10 nM NAADP (the threshold concentration for NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release via TPCs) was reported as being sufficient to induce a global Ca2+ transient in SKBR3 cells transiently overexpressing TPC1 (see also supplementary information of Ref. 15). Moreover, depletion of acidic Ca2+ stores with bafilomycin attenuated rather than blocked observed Ca2+ signals, as did blocking RyRs with ryanodine. Thus, under the conditions of these experiments, Ca2+ release via TPC1 appeared to couple to the ER (although this was not tested) by CICR via RyRs. It is possible, therefore, that the capacity for TPC1-ER coupling may have been enhanced by increased expression levels and/or more widespread distribution of TPC1. Alternatively, more efficient coupling to the ER in SKB3R cells may be conferred by the endogenous expression of RyRs, which are not expressed in HEK-293 cells.

That Ca2+ release via TPC2 may be induced by NAADP has also received support from another study, in which transient transfection of TPC2 in HEK-293 cells was utilized, after which TPC2 was reported as being associated with both lysosomes and the ER (110). Here too, intracellular dialysis of NAADP [although under different conditions than those used by us (21)] evoked an increase in [Ca2+]i that was only attenuated by depletion of acidic Ca2+ stores with bafilomycin. Furthermore and contrary to our findings, the observed Ca2+ signals remained unaffected following depletion of ER Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin. It would appear, therefore, that, under the conditions of these experiments, Ca2+ release via TPC2 was insufficient to elicit CICR from the ER and that ER-targeted TPC2 was silent.

Therefore, it is important to note that, in addition to providing support for the view that TPCs represent a family of NAADP receptors, these studies suggest that coupling efficiency between acidic Ca2+ stores and the S/ER may vary between cell types, and it is quite possible that alterations in coupling efficiency may occur in a regulated fashion. On the other hand, to what extent these differences arise from overexpression of TPC isoforms in different host cells, the expression methodology employed, or the method by which NAADP is introduced into the cell awaits clarification by way of future studies.

Junctional Coupling Between Acidic Stores and the ER: A Quantal Theory for Ca2+ Signaling Based on Vesicular Endolysosomal Stores

It is well known that Ca2+ is a coagonist of IP3Rs, being able to potentiate IP3R function upon binding to the cytoplasmic surface of IP3Rs in the presence of low IP3 levels, i.e., IP3Rs exhibit CICR (14, 40, 71). Moreover, Ca2+ release via IP3Rs may also be facilitated by an increase in [Ca2+] at the luminal surface of the S/ER membrane following Ca2+ uptake into the S/ER via SERCA (5). This bimodal regulation of CICR is also evident with respect to S/ER Ca2+ release via RyR activation (39). Of great significance in this respect is the fact that there are clear differences in the sensitivity to activation by Ca2+ and requirement for cofactors between IP3Rs and RyRs and between each subtype of IP3R (1, 2, and 3) (40, 71) and RyR (1, 2, and 3; for discussion, see Ref. 48). In addition, the concentration-response kinetics of CICR at the single-channel level may also vary quite markedly. Thereby cell-specific expression and/or targeting of different IP3Rs and RyRs, respectively, to discrete intracellular compartments provides for a high degree of versatility with respect to regulation; even more so if the proposal that NAADP may also activate RyR1 directly can be verified (27). The demonstration that TPCs may, possibly in a cell-specific manner, couple to IP3Rs and RyRs by releasing Ca2+ from acidic stores can only enhance the level of versatility available. In this respect, the vesicular nature of acidic stores may be an important determinant of outcome.

We would, therefore, like to take this opportunity to propose the hypothesis that endolysosomal Ca2+ release via TPCs may be “quantal” in nature and initiated in an all-or-none manner by NAADP. However, we wish to make it clear that we do not presume that each quantal event will be of similar size, as it is clear that these “quanta” may be defined, not simply by the conductance and Ca2+ selectivity of a given TPC at the single channel level (which would represent the elementary Ca2+ signal) and/or by the clustering of TPCs within the membrane of the acidic store to which they are targeted, but by the additional limitation provided by the defined and variable size (0.2–1 μm in diameter) of endosomal and lysosomal vesicles (Fig. 5). Not only do these discrete vesicular structures have variable sizes, but they also have “preferred” intracellular locations (61, 88) into which they may release quanta of Ca2+, i.e., they may couple to different Ca2+-dependent processes. This will likely occur in an all-or-none manner and will be limited by the capacity of a given vesicle to store Ca2+ multiplied by the number of vesicles “available” and, subsequently, the summation of each individual burst of Ca2+ release in space and time. That this may be the case is evident from the fact that, unlike IP3Rs and RyRs, TPCs/NAADP receptors are not sensitized/activated by Ca2+, i.e., the burst of Ca2+ release from vesicular acidic stores will not be inherently regenerative. Therefore, Ca2+ bursts from either endosomes, lysosomes, or both alone will always comprise scattered, local events.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram illustrates the possible relationship between a mobile lysosome and the junctional complex formed between “docked” lysosome clusters and the S/ER. Also depicted is the generation of local, monoquantal Ca2+ release (A) and the development of a propagating Ca2+ wave by quantal recruitment of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) or ryanodine receptor (RyR) clusters on the S/ER (B). SERCA, S/ER Ca2+-ATPase.

Clustering in time and space of quantal Ca2+ release from “activated” acidic stores may, however, be sufficient to breach a given threshold for CICR from the S/ER via IP3Rs and/or RyRs (Fig. 5). For this to occur, however, acidic stores and, therefore, TPCs will likely need to be situated very close to the S/ER to achieve efficient coupling. It is here that the spatial and temporal summation of coordinated Ca2+ release events from acidic organelles may be critical with respect to the conversion of NAADP-evoked quantal Ca2+ release into propagating, global Ca2+ waves via CICR from the S/ER and in a manner that may be determined by the threshold for activation by Ca2+ of IP3Rs and RyRs. This is evident from previous studies on pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, in which NAADP-dependent Ca2+ bursts from lysosome-related Ca2+ stores are amplified into global Ca2+ waves in an all-or-none manner by CICR from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via RyRs, i.e., induced Ca2+ bursts may either be “abortive” or may exhibit sufficient spatiotemporal summation to breach the threshold for CICR from the SR and thereby trigger a propagating, global Ca2+ wave (13). Such a requirement for spatiotemporal summation of the collective endolysosomal Ca2+ bursts may explain, at least in part, the delay observed between initiation of this event horizon and subsequent amplification via CICR from the S/ER. In keeping with the hypothesis, we suggest that the main reason for detecting the secondary global Ca2+ transient in TPC2-overexpressing cells may be that the increased frequency of TPC2-mediated Ca2+ release allows for greater spatiotemporal summation than that conferred by endogenously expressed TPC1/TPC2 in wild-type HEK-293 cells. Thus lysosome-ER coupling may occur by a mechanism of quantal recruitment of S/ER Ca2+ release channels that will only lead to a propagating wave once CICR is initiated via a population of IP3Rs and/or RyRs sufficiently large to allow for the recruitment of more distant receptor clusters.

Thereafter, as broached above, junctional coupling efficiency may come into play. To achieve efficient coupling, acidic stores may need to be situated very close to the S/ER. Extrapolating this argument to our observations in HEK-293 cells that stably overexpress TPC2, it is possible that lysosomes/lysosome clusters form relatively tight junctions with the ER, akin to those that have been proposed to exist between lysosomes and a subpopulation of RyRs on the SR in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle, which may be <100 nm across and which has been proposed to constitute a “trigger zone” for the initiation of propagating Ca2+ signals in response to NAADP (47). In this respect, it is also notable that, in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle, RyR3 may be preferentially targeted to this trigger zone and play a specialized role in converting local NAADP-evoked Ca2+ bursts into regenerative, global Ca2+ transients via the subsequent recruitment of other RyR subtypes located proximal to lysosome-SR junctions (48). It has been proposed that RyR3 may be preferentially targeted to the SR within these junctions because, compared with RyR1 and RyR2, RyR3 exhibits a relatively high EC50 for CICR, a marked Ca2+-dependent increase in gain (open probability, Po + mean open time) and a greater resistance to inactivation by high (mM) [Ca2+] (for detailed discussion see Ref. 48). Thus RyR3 may provide a necessary “margin of safety” with respect to the threshold for amplification of Ca2+ bursts into global Ca2+ waves, confer pronounced amplification of Ca2+ bursts once the threshold for CICR has been breached, and reduce the possibility of failure of the amplification process in the presence of the very high local [Ca2+] that may be attained within the lysosome-SR junctions. Also notable from this study is the finding that, in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, RyR3 is almost entirely restricted to the perinuclear region (where lysosomes form dense clusters) and would, therefore, be incapable of supporting a propagating, global Ca2+ wave. For this purpose, it has been proposed that RyR2 may be employed, because these channels are located proximal to lysosome-SR junctions and their distribution extends across the wider cell. Moreover, RyR2 has a lower EC50 with respect to CICR and would, therefore, provide for a propagating Ca2+ wave that is less prone to failure. Thus, as mentioned above, the subtype of RyR and/or IP3R targeted to lysosome-S/ER junctions may act as the final determinant of outcome and in a cell-specific manner, by providing for variations in the “margin of safety” with respect to the initiation of propagating global Ca2+ signals that may be determined both by the threshold for activation and gain conferred by the “coupled” receptor.

The above hypothesis may offer an explanation for the fact that, in TPC1-overexpressing cells, we observed only highly localized Ca2+ transients in response to 10 nM NAADP, i.e., why NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release via TPC1 failed to induce global Ca2+ waves by subsequent CICR from the ER. As mentioned above, under the conditions of our experiments, TPC1 was found to be associated with endosomes but not lysosomes, and endosome vesicles are much smaller in size than lysosomes and hence most likely hold smaller quanta of Ca2+. Moreover, TPC1 and the endosomal population to which it is targeted, when stably overexpressed, exhibit a more restricted spatial distribution in HEK-293 cells than does TPC2/lysosomes and in a manner that mirrors the Ca2+ signals observed in cells stably overexpressing TPC1. It is quite possible, therefore, that Ca2+ release from endosomes via TPC1 functions to provide local, rather than global, Ca2+ signals to regulate endosome-related processes alone. However, this does not preclude the regulation of wider cell functions in certain cell types. In this respect, it may be important to note that, in certain cell types, endolysosomal Ca2+ bursts via TPCs may preferentially couple to Ca2+-sensitive ion channels in the plasma membrane (18, 21, 23), rather than to S/ER Ca2+ release channels. In this instance, Ca2+ bursts may serve to modulate membrane potential and thereby voltage-gated Ca2+ influx into the cell within which they are generated. Once again, the precise outcome will be determined by the properties of the channel activated. For example, recruitment of Ca2+-activated cation channels may precipitate depolarization and action potential generation or even increase the refractory period of a cell. Conversely, recruitment of Ca2+-activated K+ channels may raise the threshold for initiation of an action potential, facilitate repolarization, and may shorten the refractory period.

Our considerations in terms of Ca2+ signaling in this “static” framework, however, have to be expanded to incorporate one further point that must necessarily be integrated into this conceptual argument. This is the fact that endolysosomal vesicles are mobile, which may perhaps allow them to act alone or in “docked” clusters and, possibly, with the movement between these two states (mobile and docked) occurring in a highly regulated fashion. Furthermore, we know that vesicle fusions do occur and as such may, therefore, give rise to acidic stores of greater size (61). Indeed, we have identified such structures in HEK-293 cells that stably overexpress TPC2 (Fig. 6; M. X. Zhu and A. M. Evans, unpublished observation). In short, cells may, via this process, provide for the generation of micro- and macro-Ca2+ bursts via TPCs, i.e., vesicle fusions may provide for a gain in quantal Ca2+ release that could, in its own right, determine functional outcomes.

Fig. 6.

Cell showing the colocalization between Alexa 488 labeled human TPC2 (green; excitation 488 nm, emission 520 nm) and Texas Red labeled LAMP2 (red; excitation 568 nm, emission 617 nm). Left: confocal Z-section taken through the cell with the distribution of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged hTPC2 (green). Middle: same as in left, but shows the distribution of LAMP2 labeling (red). Right: a merged image of other two panels with areas of colocalization shown in yellow. In addition to the regular lysosomes, both elements of labeling highlight a very large lysosome-related vesicular structure.

Whatever the scenario, coupling between TPCs and a variety of Ca2+-activated channels may play a key role in functional decision making. Thus the spatiotemporal integration of Ca2+ bursts may serve as a filter via which cellular signals may be sorted into either abortive local events or propagating global Ca2+ signals via lysosome-S/ER junctions (47, 48), analogous to the mitochondrial-S/ER junctions conferred by mitofusin 2-dependent interorganellar bridges (28).

What Might be the Functional Role of TPCs?

It is quite clear that global Ca2+ signals induced, or indeed modulated (64), as a consequence of NAADP-dependent endolysosomal Ca2+ release will regulate primary cell function, such as fertilization events in sea urchin and starfish eggs (25, 72), digestive enzyme and fluid secretion of pancreatic acinar cells (105), glucose-induced insulin secretion in β-cells (67), smooth muscle contraction in the vasculature (13, 47), cardiac contraction (64), T-lymphocyte activation (8), neurotransmitter release and neurite outgrowth (16, 17), and platelet activation (59). However, this has been discussed in detail elsewhere in connection with the physiological roles of NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signaling. What may be even more significant to future advances in the field of Ca2+ signaling, however, may be the role of Ca2+ release from acidic stores in the functional regulation of these stores themselves.

TPCs and lysosomal function.

Lysosomes are traditionally considered to function as sites of cellular degradation of macromolecules, which may be modulated by changes in luminal pH. It may be significant, therefore, that NAADP-induced Ca2+ release from the reserve granules of sea urchin eggs precipitates an increase (alkalinization) in their intraluminal pH (74). Thus Ca2+ release via TPC2 may critically regulate the intraluminal pH of lysosomes and thereby modulate the activity of pH-sensitive hydrolytic lysosomal enzymes, such as glucocerebrosidase, which exhibits a marked loss of function at pH > 5 (76, 100) and may lead thereby to consequent accumulation of macromolecules, such as glucocerebroside.

Lysosomes also play a significant role in the process of autophagy, which is involved in programmed cell death, but also serves to recycle organelles, such as mitochondria, through a process of degradation involving lysosomal hydrolases (37, 65). That TPC2 may contribute to this process is evident from the fact that bafilomycin, which discharges lysosomal Ca2+ stores, inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion in a manner that has been proposed to be an indirect result of the bafilomycin-induced luminal alkalinization of lysosomes, and possibly endosomes and amphisomes (49). Moreover, it is clear that luminal [Ca2+] and Ca2+-calmodulin are required for completion of the late endosome-lysosome fusion process and lysosome reformation associated with autophagy and, indeed, phagocytosis (84, 85).

TPCs and endosomal function.

Endosomes are critically involved in the sorting of endocytosed membrane-bound proteins, which may then be recycled to the plasma membrane via recycling endosomes or trafficked through the endolysosome system to lysosomes. This trafficking requires multiple membrane fusion events that are dependent on Ca2+ release for the effective formation of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor-attachment protein receptor complex (60). This process requires intracellular Ca2+ as, for example, buffering of cytoplasmic Ca2+ with EGTA inhibits endocytic protein transport from the ER to the Golgi apparatus (7), and increasing the cytoplasmic [Ca2+] increases fusion events observed in an in vitro assay (68). Thus transport of proteins between lysosomes, Golgi apparatus, and plasma membrane via endosomes may be dependent on the spatially restricted Ca2+ release that we have observed in HEK-293 cells that stably overexpress TPC1. Therefore, in the absence of a global Ca2+ transient, Ca2+ release via TPC1 may regulate endosomal protein trafficking.

TPCs and recycling endosome function.

Internalization and transport of various plasma membrane-bound proteins, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), occurs via the endocytic pathway. Once internalized, for example, GPCRs may be sorted via endosomes and either degraded by transportation to lysosomes or “regenerated” by ligand dissociation/receptor dephosphorylation and recycled to the plasma membrane via recycling endosomes. This process not only is considered to regulate the number of receptors present on the plasma membrane, but may also transport the active ligand-receptor complex and thus propagate their respective signaling cascades (88, 102). Endosomes may, therefore, deliver active ligand-receptor signaling complexes to specific locations within the cell (88). Thus Ca2+ signaling via TPCs on endosomal membranes may contribute to the regulation of GPCR signaling pathways by determining which of the divergent pathways the internalized receptor follows and/or by indirectly controlling the length of time the receptor spends intracellularly via the regulation of membrane fusion. For example, in the human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa), bafilomycin abolishes transport of receptors to lysosomes, but not recycling to the plasma membrane (4). Conversely, bafilomycin reduced the rate of receptor recycling in Chinese hamster ovary-derived cell lines (43, 83). Ca2+ release via TPCs may, therefore, determine, in part, the pathway followed by internalized receptors. That the effect of bafilomycin on these divergent pathways varied according to cell type suggests that outcomes could be determined by variations in the relative expression of each TPC subtype and as consequent changes in the pattern of Ca2+ signals generated in each cell type.

TPCs and the function of lysosome-related acidic organelles.

TPCs may also play an important role in the functioning of lysosome-related organelles, such as melanosomes, which are responsible for the delivery of melanin to keratinocytes (12). Melanosome-keratinocyte interaction triggers a transient rise in [Ca2+]i within the keratinocyte, which, in turn, evokes melanosome-dependent melanin transfer. Thus a particular TPC subtype(s) may be involved in some of the mechanisms that underpin pigmentation. Consistent with this proposal, two coding variants in the TPCN2 gene are associated with determining blonde vs. brown hair color in a European population (95).

What of the Role of TPC-dependent Ca2+ Signaling in Disease?

A number of diseases, such as lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs), are caused by the dysfunction of lysosomal enzymes, lysosome-associated proteins involved in lysosomal biogenesis, or enzyme activation/targeting (80). One of the more common LSDs is Gaucher disease (109), which is caused by reduced activity of lysosomal glucocerebrosidase. This leads to consequent accumulation of glucosylceramide and transformation of the cell into a Gaucher cell (109). Interestingly, the L-type VGCC blockers diltiazem and verapamil have been shown to partially restore glucocerebrosidase function in Gaucher disease patient-derived fibroblasts (75). This finding is particularly interesting, given that NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release is inhibited by VGCC blockers (36), as is NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release via TPCs (A. M. Evans, unpublished observation). These findings, together with the fact that NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release alters the intraluminal pH of acidic stores (74), suggest that TPC2 may be involved in regulating the optimal functional conditions for lysosomal enzymes, as proposed above, and may contribute to some of the mechanisms implicated in LSDs by compounding the aberrant operational environment of glucocerebrosidase.

Another common example of LSDs is Niemann-Pick disease, which is characterized by defects in the activity of sphingolipid-degrading enzymes that result in excessive lysosomal storage of sphingolipids (94). Niemann-Pick disease types A and B occur due to mutations in the gene of the enzyme acid sphingomyelinase (SMase), whereas Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (NPC1) is due to defective cholesterol transport from the lysosome, with a secondary defect in SMase activity, and this may result in the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol in perinuclear lysosomes (94). In addition to defective hydrolysis of sphingolipids, LSDs, such as NPC1, precipitate defective transport of sphingolipids through the endocytic compartments (66). As mentioned above, endocytic transport of molecules, such as sphingolipids, requires a number of endosomal/lysosomal membrane fusion events, which, in turn, are dependent on Ca2+ release from the acidic stores (82). Consistent with this, recent evidence suggests that, with NPC1, dysfunctional lysosomal Ca2+ homeostasis precedes excessive sphingosine storage (58), and this has been shown to reduce NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release in NPC1 mutant cells by ∼70%. Thus TPCs may contribute to Niemann-Pick disease, either by erroneous modulation of the luminal pH of lysosomes, leading to dysfunctional SMase activity, or by precipitating erroneous endosomal transport/membrane fusion.

A further implication of endolysosomal Ca2+ release via TPCs concerns an autosomal recessive nonsyndrommic deafness locus DFNB63. This locus has been linked with human chromosome location 11q13.2-13.3 (46), which also contains the gene encoding human TPC2 (TPCN2). However, sequencing of the coding regions for the 13 candidate genes, including TPCN2, from an affected individual identified no disease-causing mutations (44). Nevertheless, given that audio abnormalities have been identified in mouse models of LSDs (45, 78, 90) and represent a recognized symptom of a number of LSDs, including Pompe disease, Gaucher disease (22), and Hunter syndrome (81), a pathophysiological role for TPC2 in these diseases cannot be excluded. Moreover, it is widely accepted that disrupting the mechanotransduction apparatus of hair cells precipitates deafness in mouse models (38). This is intriguing, because an unexpected finding of ours has been that stable overexpression of TPC2 in HEK-293 cells confers marked and global mechanosensitive Ca2+ signals that can be induced by simply prodding the plasma membrane with a “closed” (fire polished) patch pipette (M. X. Zhu and A. M. Evans, unpublished observation); this may also be a confounding variable with respect to studies on TPCs in which microinjection techniques are used (A. Galione and J. Parrington, unpublished observation).

That TPC2 may confer mechanosensitive Ca2+ signals and be sensitive to block by VGCC antagonists also has resonance with respect to the myogenic response of arterial smooth muscle and related vascular pathophysiology. Consistent with this view, the L-type VGCC antagonist nimodipine is used therapeutically to treat subarachnoid hemorrhage, migraine, and cluster headache (31, 99). However, in this respect, nimodipine is by far the most effective among VGCC antagonists, and its site of action is open to question. Thus our preliminary finding (A. M. Evans, unpublished observation) that nimodipine blocks TPCs over the same concentration range at which it is considered to selectively block VGCCs may be relevant. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the myogenic response of cerebral arteries is mediated, in part, by calcium release from intracellular stores (96), and it has been shown that vasodilation induced by VGCC antagonists is, in part, due to inhibition of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (89).

It would appear, therefore, that TPCs may offer an as yet untapped therapeutic target for the treatment of a variety of diseases.

Summary

Identification of TPCs as a family of endolysosomal Ca2+ release channels provides important new insights into the mechanisms of intracellular communication. That these stores represent small vesicular structures adds to the versatility of the Ca2+ signaling apparatus by providing for a mechanism of quantal Ca2+ release that may be utilized to “filter” Ca2+ signals at junctional complexes between endolysosome stores and, for example, S/ER compartments. Thereby cells may determine whether a given signal remains local or is converted into a propagating global signal. Thus environmental stimuli may, by mobilizing endolysosomal stores, selectively regulate endolysosomal function alone or engage primary cell function, such as smooth muscle contraction. Therefore, future investigations on these novel Ca2+ release channels will undoubtedly provide unexpected insights into the regulation of a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes.

GRANTS

The authors thank US National Institutes of Health (to M. X. Zhu, A. M. Evans, and J. Ma), Wellcome Trust (to A. M. Evans, J. Parrington, and A. Galione), American Heart Association (to M. X. Zhu), and British Heart Foundation (to A. M. Evans) for support.

DISCLOSURES

I am not aware of financial conflict(s) with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript with any of the authors, or any of the authors’ academic institutions or employers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarhus R, Dickey DM, Graeff RM, Gee KR, Walseth TF, Lee HC. Activation and inactivation of Ca2+ release by NAADP+. J Biol Chem 271: 8513–8516, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarhus R, Graeff RM, Dickey DM, Walseth TF, Lee HC. ADP-ribosyl cyclase and CD38 catalyze the synthesis of a calcium-mobilizing metabolite from NADP. J Biol Chem 270: 30327–30333, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyama M, Yamada A, Wang J, Ohya S, Furuzono S, Goto T, Hotta S, Ito Y, Matsubara T, Shimokata K, Chen SR, Imaizumi Y, Nakayama S. Requirement of ryanodine receptors for pacemaker Ca2+ activity in ICC and HEK293 cells. J Cell Sci 117: 2813–2825, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baravalle G, Schober D, Huber M, Bayer N, Murphy RF, Fuchs R. Transferrin recycling and dextran transport to lysosomes is differentially affected by bafilomycin, nocodazole, and low temperature. Cell Tissue Res 320: 99–113, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastianutto C, Clementi E, Codazzi F, Podini P, De Giorgi F, Rizzuto R, Meldolesi J, Pozzan T. Overexpression of calreticulin increases the Ca2+ capacity of rapidly exchanging Ca2+ stores and reveals aspects of their lumenal microenvironment and function. J Cell Biol 130: 847–855, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck A, Kolisek M, Bagley LA, Fleig A, Penner R. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose regulate TRPM2 channels in T lymphocytes. FASEB J 20: 962–964, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckers CJ, Balch WE. Calcium and GTP: essential components in vesicular trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol 108: 1245–1256, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg I, Potter BV, Mayr GW, Guse AH. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP+) is an essential regulator of T-lymphocyte Ca(2+)-signaling. J Cell Biol 150: 581–588, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg TO, Stromhaug E, Lovdal T, Seglen O, Berg T. Use of glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide, a lysosome-disrupting cathepsin C substrate, to distinguish between lysosomes and prelysosomal endocytic vacuoles. Biochem J 300: 229–236, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berridge MJ. Calcium microdomains: organization and function. Cell Calcium 40: 405–412, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 933–940, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatnagar V, Anjaiah S, Puri N, Darshanam BN, Ramaiah A. pH of melanosomes of B 16 murine melanoma is acidic: its physiological importance in the regulation of melanin biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 307: 183–192, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boittin FX, Galione A, Evans AM. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate mediates Ca2+ signals and contraction in arterial smooth muscle via a two-pool mechanism. Circ Res 91: 1168–1175, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bootman MD, Lipp P. Ringing changes to the “bell-shaped curve”. Curr Biol 9: R876–R878, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brailoiu E, Churamani D, Cai X, Schrlau MG, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Hooper R, Boulware MJ, Dun NJ, Marchant JS, Patel S. Essential requirement for two-pore channel 1 in NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J Cell Biol 186: 201–209, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brailoiu E, Hoard JL, Filipeanu CM, Brailoiu GC, Dun SL, Patel S, Dun NJ. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate potentiates neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem 280: 5646–5650, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brailoiu E, Patel S, Dun NJ. Modulation of spontaneous transmitter release from the frog neuromuscular junction by interacting intracellular Ca(2+) stores: critical role for nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP). Biochem J 373: 313–318, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brailoiu GC, Brailoiu E, Parkesh R, Galione A, Churchill GC, Patel S, Dun NJ. NAADP-mediated channel ‘chatter’ in neurons of the rat medulla oblongata. Biochem J 419: 91–97, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brini M, Carafoli E. Calcium pumps in health and disease. Physiol Rev 89: 1341–1378, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahalan MD. STIMulating store-operated Ca(2+) entry. Nat Cell Biol 11: 669–677, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, Hao X, Tang J, Rietdorf K, Teboul L, Chuang KT, Lin P, Xiao R, Wang C, Zhu Y, Lin Y, Wyatt CN, Parrington J, Ma J, Evans AM, Galione A, Zhu MX. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature 459: 596–600, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell PE, Harris CM, Harris CM, Sirimanna T, Vellodi A. A model of neuronopathic Gaucher disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 26: 629–639, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancela JM, Churchill GC, Galione A. Coordination of agonist-induced Ca2+-signalling patterns by NAADP in pancreatic acinar cells. Nature 398: 74–76, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen KA, Myers JT, Swanson JA. pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J Cell Sci 115: 599–607, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Churchill GC, O'Neill JS, Masgrau R, Patel S, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Galione A. Sperm deliver a new second messenger: NAADP. Curr Biol 13: 125–128, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchill GC, Okada Y, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Patel S, Galione A. NAADP mobilizes Ca(2+) from reserve granules, lysosome-related organelles, in sea urchin eggs. Cell 111: 703–708, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dammermann W, Zhang B, Nebel M, Cordiglieri C, Odoardi F, Kirchberger T, Kawakami N, Dowden J, Schmid F, Dornmair K, Hohenegger M, Flugel A, Guse AH, Potter BV. NAADP-mediated Ca2+ signaling via type 1 ryanodine receptor in T cells revealed by a synthetic NAADP antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 10678–10683, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin-2 regulates mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum morphology and tethering: the role of Ras. Mitochondrion 9: 222–226, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong XP, Cheng X, Mills E, Delling M, Wang F, Kurz T, Xu H. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature 455: 992–996, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endo M. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Adv Exp Med Biol 592: 275–285, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher M, Grotta J. New uses for calcium channel blockers. Therapeutic implications. Drugs 46: 961–975, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischer S. Personal recollections on the discovery of the ryanodine receptors of muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 369: 195–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galione A, Lee HC, Busa WB. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in sea urchin egg homogenates: modulation by cyclic ADP-ribose. Science 253: 1143–1146, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genazzani AA, Empson RM, Galione A. Unique inactivation properties of NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem 271: 11599–11602, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Genazzani AA, Galione A. Nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate mobilizes Ca2+ from a thapsigargin-insensitive pool. Biochem J 315: 721–725, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genazzani AA, Mezna M, Dickey DM, Michelangeli F, Walseth TF, Galione A. Pharmacological properties of the Ca2+-release mechanism sensitive to NAADP in the sea urchin egg. Br J Pharmacol 121: 1489–1495, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gozuacik D, Kimchi A. Autophagy as a cell death and tumor suppressor mechanism. Oncogene 23: 2891–2906, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant L, Fuchs PA. Auditory transduction in the mouse. Pflügers Arch 454: 793–804, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gyorke S, Terentyev D. Modulation of ryanodine receptor by luminal calcium and accessory proteins in health and cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res 77: 245–255, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirose K, Kadowaki S, Iino M. Allosteric regulation by cytoplasmic Ca2+ and IP3 of the gating of IP3 receptors in permeabilized guinea-pig vascular smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 506: 407–414, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishibashi K, Suzuki M, Imai M. Molecular cloning of a novel form (two-repeat) protein related to voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 270: 370–376, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang D, Zhao L, Clapham DE. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies Letm1 as a mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ antiporter. Science 326: 144–147, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson LS, Dunn KW, Pytowski B, McGraw TE. Endosome acidification and receptor trafficking: bafilomycin A1 slows receptor externalization by a mechanism involving the receptor's internalization motif. Mol Biol Cell 4: 1251–1266, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalay E, Uzumcu A, Krieger E, Caylan R, Uyguner O, Ulubil-Emiroglu M, Erdol H, Kayserili H, Hafiz G, Baserer N, Heister AJ, Hennies HC, Nurnberg P, Basaran S, Brunner HG, Cremers CW, Karaguzel A, Wollnik B, Kremer H. MYO15A (DFNB3) mutations in Turkish hearing loss families and functional modeling of a novel motor domain mutation. Am J Med Genet A 143A: 2382–2389, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamphoven JH, de Ruiter MM, Winkel LP, Van den Hout HM, Bijman J, De Zeeuw CI, Hoeve HL, Van Zanten BA, Van der Ploeg AT, Reuser AJ. Hearing loss in infantile Pompe's disease and determination of underlying pathology in the knockout mouse. Neurobiol Dis 16: 14–20, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan SY, Riazuddin S, Tariq M, Anwar S, Shabbir MI, Riazuddin SA, Khan SN, Husnain T, Ahmed ZM, Friedman TB, Riazuddin S. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness locus DFNB63 at chromosome 11q13.2-q133. Hum Genet 120: 789–793, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kinnear NP, Boittin FX, Thomas JM, Galione A, Evans AM. Lysosome-sarcoplasmic reticulum junctions. A trigger zone for calcium signaling by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate and endothelin-1. J Biol Chem 279: 54319–54326, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinnear NP, Wyatt CN, Clark JH, Calcraft PJ, Fleischer S, Jeyakumar LH, Nixon GF, Evans AM. Lysosomes co-localize with ryanodine receptor subtype 3 to form a trigger zone for calcium signalling by NAADP in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Cell Calcium 44: 190–201, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klionsky DJ, Elazar Z, Seglen PO, Rubinsztein DC. Does bafilomycin A1 block the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes? Autophagy 4: 849–950, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lange I, Yamamoto S, Partida-Sanchez S, Mori Y, Fleig A, Penner R. TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci Signal 2: ra23, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee HC. Enzymatic functions and structures of CD38 and homologs. Chem Immunol 75: 39–59, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee HC. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-mediated calcium signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 33693–33696, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HC. Physiological functions of cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP as calcium messengers. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 317–345, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee HC, Aarhus R. A derivative of NADP mobilizes calcium stores insensitive to inositol trisphosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose. J Biol Chem 270: 2152–2157, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HC, Aarhus R. Functional visualization of the separate but interacting calcium stores sensitive to NAADP and cyclic ADP-ribose. J Cell Sci 113: 4413–4420, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee HC, Aarhus R, Gee KR, Kestner T. Caged nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Synthesis and use. J Biol Chem 272: 4172–4178, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu T, O'Rourke B. Regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ and its effects on energetics and redox balance in normal and failing heart. J Bioenerg Biomembr 41: 127–132, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lloyd-Evans E, Morgan AJ, He X, Smith DA, Elliot-Smith E, Sillence DJ, Churchill GC, Schuchman EH, Galione A, Platt FM. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium. Nat Med 14: 1247–1255, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lopez JJ, Redondo PC, Salido GM, Pariente JA, Rosado JA. Two distinct Ca2+ compartments show differential sensitivity to thrombin, ADP and vasopressin in human platelets. Cell Signal 18: 373–381, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luzio JP, Parkinson MD, Gray SR, Bright NA. The delivery of endocytosed cargo to lysosomes. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 1019–1021, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 622–632, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luzio JP, Rous BA, Bright NA, Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Piper RC. Lysosome-endosome fusion and lysosome biogenesis. J Cell Sci 113: 1515–1524, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma J, Pan Z. Retrograde activation of store-operated calcium channel. Cell Calcium 33: 375–384, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macgregor A, Yamasaki M, Rakovic S, Sanders L, Parkesh R, Churchill GC, Galione A, Terrar DA. NAADP controls cross-talk between distinct Ca2+ stores in the heart. J Biol Chem 282: 15302–15311, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marino G, Lopez-Otin C. Autophagy: molecular mechanisms, physiological functions and relevance in human pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci 61: 1439–1454, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marks DL, Pagano RE. Endocytosis and sorting of glycosphingolipids in sphingolipid storage disease. Trends Cell Biol 12: 605–613, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Masgrau R, Churchill GC, Morgan AJ, Ashcroft SJ, Galione A. NAADP: a new second messenger for glucose-induced Ca2+ responses in clonal pancreatic beta cells. Curr Biol 13: 247–251, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayorga LS, Beron W, Sarrouf MN, Colombo MI, Creutz C, Stahl PD. Calcium-dependent fusion among endosomes. J Biol Chem 269: 30927–30934, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Menteyne A, Burdakov A, Charpentier G, Petersen OH, Cancela JM. Generation of specific Ca(2+) signals from Ca(2+) stores and endocytosis by differential coupling to messengers. Curr Biol 16: 1931–1937, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Missiaen L, Van Acker K, Van Baelen K, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Vanoevelen J, Dode L, Rizzuto R, Callewaert G. Calcium release from the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum in HeLa cells stably expressing targeted aequorin to these compartments. Cell Calcium 36: 479–487, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyakawa T, Maeda A, Yamazawa T, Hirose K, Kurosaki T, Iino M. Encoding of Ca2+ signals by differential expression of IP3 receptor subtypes. EMBO J 18: 1303–1308, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moccia F, Lim D, Kyozuka K, Santella L. NAADP triggers the fertilization potential in starfish oocytes. Cell Calcium 36: 515–524, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moreno SN, Docampo R. The role of acidocalcisomes in parasitic protists. J Eukaryot Microbiol 56: 208–213, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morgan AJ, Galione A. NAADP induces pH changes in the lumen of acidic Ca2+ stores. Biochem J 402: 301–310, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mu TW, Fowler DM, Kelly JW. Partial restoration of mutant enzyme homeostasis in three distinct lysosomal storage disease cell lines by altering calcium homeostasis. PLoS Biol 6: e26, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mueller OT, Rosenberg A. β-Glucoside hydrolase activity of normal and glucosylceramidotic cultured human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 252: 825–829, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oancea E, Vriens J, Brauchi S, Jun J, Splawski I, Clapham DE. TRPM1 forms ion channels associated with melanin content in melanocytes. Sci Signal 2: ra21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ohlemiller KK, Hennig AK, Lett JM, Heidbreder AF, Sands MS. Inner ear pathology in the mucopolysaccharidosis VII mouse. Hear Res 169: 69–84, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pandey V, Chuang CC, Lewis AM, Aley PK, Brailoiu E, Dun NJ, Churchill GC, Patel S. Recruitment of NAADP-sensitive acidic Ca2+ stores by glutamate. Biochem J 422: 503–512, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parkinson-Lawrence E, Fuller M, Hopwood JJ, Meikle PJ, Brooks DA. Immunochemistry of lysosomal storage disorders. Clin Chem 52: 1660–1668, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peck JE. Hearing loss in Hunter's syndrome–mucopolysaccharidosis II. Ear Hear 5: 243–246, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Piper RC, Luzio JP. CUPpling calcium to lysosomal biogenesis. Trends Cell Biol 14: 471–473, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Presley JF, Mayor S, McGraw TE, Dunn KW, Maxfield FR. Bafilomycin A1 treatment retards transferrin receptor recycling more than bulk membrane recycling. J Biol Chem 272: 13929–13936, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pryor PR, Luzio JP. Delivery of endocytosed membrane proteins to the lysosome. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 615–624, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Bright NA, Gray SR, Luzio JP. The role of intraorganellar Ca(2+) in late endosome-lysosome heterotypic fusion and in the reformation of lysosomes from hybrid organelles. J Cell Biol 149: 1053–1062, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pryor PR, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Luzio JP. Mucolipin-1 is a lysosomal membrane protein required for intracellular lactosylceramide traffic. Traffic 7: 1388–1398, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rimessi A, Giorgi C, Pinton P, Rizzuto R. The versatility of mitochondrial calcium signals: from stimulation of cell metabolism to induction of cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777: 808–816, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sadowski L, Pilecka I, Miaczynska M. Signaling from endosomes: location makes a difference. Exp Cell Res 315: 1601–1609, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saida K, van Breemen C. Mechanism of Ca++ antagonist-induced vasodilation. Intracellular actions. Circ Res 52: 137–142, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schachern PA, Cureoglu S, Tsuprun V, Paparella MM, Whitley CB. Age-related functional and histopathological changes of the ear in the MPS I mouse. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 71: 197–203, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schwaller B. The continuing disappearance of “pure” Ca2+ buffers. Cell Mol Life Sci 66: 275–300, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Soeller C, Crossman D, Gilbert R, Cannell MB. Analysis of ryanodine receptor clusters in rat and human cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 14958–14963, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soyombo AA, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, Rbaibi Y, Bashllari E, Bisceglia J, Muallem S, Kiselyov K. TRP-ML1 regulates lysosomal pH and acidic lysosomal lipid hydrolytic activity. J Biol Chem 281: 7294–7301, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sturley SL, Patterson MC, Balch W, Liscum L. The pathophysiology and mechanisms of NP-C disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1685: 83–87, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Stacey SN, Helgason A, Rafnar T, Jakobsdottir M, Steinberg S, Gudjonsson SA, Palsson A, Thorleifsson G, Palsson S, Sigurgeirsson B, Thorisdottir K, Ragnarsson R, Benediktsdottir KR, Aben KK, Vermeulen SH, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Kiemeney LA, Olafsson JH, Gulcher J, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Two newly identified genetic determinants of pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet 40: 835–837, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tanaka Y, Hata S, Ishiro H, Ishii K, Nakayama K. Stretching releases Ca2+ from intracellular storage sites in canine cerebral arteries. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 19–24, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taylor CW, Taufiq Ur R, Pantazaka E. Targeting and clustering of IP3 receptors: key determinants of spatially organized Ca2+ signals. Chaos 19: 037102, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thai TL, Churchill GC, Arendshorst WJ. NAADP receptors mediate calcium signaling stimulated by endothelin-1 and norepinephrine in renal afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F510–F516, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tomassoni D, Lanari A, Silvestrelli G, Traini E, Amenta F. Nimodipine and its use in cerebrovascular disease: evidence from recent preclinical and controlled clinical studies. Clin Exp Hypertens 30: 744–766, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van Weely S, van den Berg M, Barranger JA, Sa Miranda MC, Tager JM, Aerts JM. Role of pH in determining the cell-type-specific residual activity of glucocerebrosidase in type 1 Gaucher disease. J Clin Invest 91: 1167–1175, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Venkatachalam K, Hofmann T, Montell C. Lysosomal localization of TRPML3 depends on TRPML2 and the mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1. J Biol Chem 281: 17517–17527, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.von Zastrow M, Sorkin A. Signaling on the endocytic pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 436–445, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weisleder N, Ma J. Altered Ca2+ sparks in aging skeletal and cardiac muscle. Ageing Res Rev 7: 177–188, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L, Missiaen L. Molecular physiology of the SERCA and SPCA pumps. Cell Calcium 32: 279–305, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yamasaki M, Masgrau R, Morgan AJ, Churchill GC, Patel S, Ashcroft SJ, Galione A. Organelle selection determines agonist-specific Ca2+ signals in pancreatic acinar and beta cells. J Biol Chem 279: 7234–7240, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yu FH, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Gutman GA, Catterall WA. Overview of molecular relationships in the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily. Pharmacol Rev 57: 387–395, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang F, Jin S, Yi F, Li PL. TRP-ML1 functions as a lysosomal NAADP-sensitive Ca(2+) release channel in coronary arterial myocytes. J Cell Mol Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang F, Zhang G, Zhang AY, Koeberl MJ, Wallander E, Li PL. Production of NAADP and its role in Ca2+ mobilization associated with lysosomes in coronary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H274–H282, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhao H, Grabowski GA. Gaucher disease: perspectives on a prototype lysosomal disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 694–707, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zong X, Schieder M, Cuny H, Fenske S, Gruner C, Rotzer K, Griesbeck O, Harz H, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C. The two-pore channel TPCN2 mediates NAADP-dependent Ca(2+)-release from lysosomal stores. Pflügers Arch 458: 891–899, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]