Abstract

Elevated intraocular pressure arising from impaired aqueous humor drainage through the trabecular pathway is a major risk factor for glaucoma. To understand the molecular basis for Rho GTPase-mediated resistance to aqueous humor drainage, we investigated the possible interrelationship between actomyosin contractile properties and extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis in human trabecular meshwork (TM) cells expressing a constitutively active form of RhoA (RhoAV14). TM cells expressing RhoAV14 exhibited significant increases in fibronectin, tenascin C, laminin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) levels, and matrix assembly in association with increased actin stress fibers and myosin light-chain phosphorylation. RhoAV14-induced changes in ECM synthesis and actin cytoskeletal reorganization were mimicked by lysophosphatidic acid and TGF-β2, known to increase resistance to aqueous humor outflow and activate Rho/Rho kinase signaling. RhoAV14, lysophosphatidic acid, and TGF-β2 stimulated significant increases in Erk1/2 phosphorylation, paralleled by profound increases in fibronectin, serum response factor (SRF), and α-SMA expression. Treatment of RhoA-activated TM cells with inhibitors of Rho kinase or Erk, on the other hand, decreased fibronectin and α-SMA levels. Although suppression of SRF expression (both endogenous and RhoA, TGF-β2-stimulated) via the use of short hairpin RNA decreased α-SMA levels, fibronectin was unaffected. Conversely, fibronectin induced α-SMA expression in an SRF-dependent manner. Collectively, data on RhoA-induced changes in actomyosin contractile activity, ECM synthesis/assembly, and Erk activation, along with fibronectin-induced α-SMA expression in TM cells, reveal a potential molecular interplay between actomyosin cytoskeletal tension and ECM synthesis/assembly. This interaction could be significant for the homeostasis of aqueous humor drainage through the pressure-sensitive trabecular pathway.

Keywords: fibronectin, actomyosin, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, serum response factor

glaucoma is a second major cause of blindness in the United States. A major risk factor for primary open-angle glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure caused by increased resistance to aqueous humor outflow localized within the trabecular pathway (15, 56). Abnormal accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) and/or extracellular material, which increases resistance to drainage of aqueous humor through the trabecular pathway, is believed to be partly responsible for the elevated intraocular pressure and primary open-angle glaucoma (24, 28, 49). The cellular mechanisms that regulate the production and turnover of ECM within the outflow pathway and how ECM turnover is linked to regulation of aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork (TM) are far from clearly understood (13, 24, 27, 49). Therefore, it would seem both necessary and critical to understand the molecular basis of resistance to aqueous humor outflow. This knowledge may provide important insights into the etiology of glaucoma and support development of effective therapies.

There is now widely documented evidence in support of a link between cytoskeletal integrity within the cells of trabecular pathway consisting of the TM, the juxtacanalicular connective tissue (JCT), and the endothelial lining of Schlemm's canal (SC) and aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular pathway. Supportive evidence for this link comes from perfusion studies that used cytoskeletal modulating agents, such as actin depolymerizing agents, inhibitors of myosin light-chain kinase, myosin II, protein kinase C, Rho GTPase, and Rho kinase and from both in vitro and in vivo model systems (11, 19, 41, 51). These studies suggest that agents that increase actin depolymerization and decrease cell-ECM interactions and myosin II phosphorylation within cells of the trabecular pathway increase aqueous humor outflow presumably by causing cellular relaxation and by altering the geometry and stiffness of the outflow pathway tissues and fluid flow through the inner wall of SC (41, 51). Conversely, agents that activate Rho GTPase and myosin II activity, including lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), sphingosine-1-phosphate, TGF-β2, and endothelin-1, decrease aqueous humor outflow facility concomitant with increased contractile activity of the TM cells, indicating a potential importance of actomyosin organization and the contractile force generated by the actomyosin system in the regulation of aqueous humor drainage (16, 33, 39, 57, 63).

Organization of the cellular actomyosin-based cytoskeletal network is dynamically regulated under physiological conditions. Extracellular signals serve as inputs to drive changes in cell morphology, cell adhesion, contractile/mechanical properties, and gene expression via actin-myosin cross-bridging and mechanotransduction (17, 20, 21). Alterations in cytoskeletal isometric tension generated through actomyosin contraction in turn activates signaling pathways, which transduce intracellular events into outputs that determine how the cell interacts with its environment, as exemplified by cell-ECM adhesive interactions and ECM assembly and rigidity (4, 20, 42, 53, 65). TM cells exhibit smooth muscle-like physiology based on their electromechanical properties (58) and the expression profile of various smooth muscle-specific proteins, including α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and CPI-17 (11, 39, 51, 58). Regulation of mechanical and contractile properties of the pressure-sensitive TM cells is recognized to play a significant role in modulation of aqueous humor outflow and ocular pressure homeostasis (22, 29, 41, 58, 60). Although there is a substantial amount of phenomenological data in the literature regarding the possible role of the ECM and cytoskeletal integrity in modulation of aqueous humor outflow, the mechanistic understanding for these interactions has lagged behind (24, 41, 49, 51). Thus identifying the molecular basis by which the ECM, cytoskeletal integrity, cellular tension, and mechanostransduction modulate outflow facility through the TM is vitally important for understanding of homeostasis of intraocular pressure.

In our recent study (63), we reported increased resistance to aqueous humor outflow facility in organ-cultured eye anterior segments expressing a constitutively active RhoA GTPase. This effect of RhoA was found to be associated with altered gene expression, including genes encoding ECM components and various cytokines, and with increased contractile activity in TM cells (63). To understand the molecular basis for a potential interaction between the contractile force generated by actomyosin assembly and ECM synthesis and organization in TM cells (63), here we investigated the involvement of different MAPKs and transcription factors in Rho GTPase-mediated activation of ECM protein synthesis. This study reveals a critical role for Erk and serum response factor (SRF) in the regulation of expression of ECM and α-SMA, respectively, in Rho GTPase activated and ECM-treated TM cells. The data from this study also uncover the importance of potential molecular interactions between actomyosin-based contractile activity and ECM-based mechanotransduction in regulation of ECM synthesis and contractile activity within the aqueous humor drainage pathway and in homeostasis of aqueous humor outflow.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Human recombinant TGF-β2, mouse monoclonal anti-vinculin, anti-tubulin, anti-α-SMA antibodies, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-phalloidin, and fibronectin from bovine plasma were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit anti phospho-SAPK/JNK, anti phospho-p38 MAPK, anti phospho-p44/42 MAPK, Erk1/2, and phospho-specific anti-myosin light chain (Thr18/Ser19) polyclonal antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Rabbit anti-SRF (SC-335) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Cell-permeable C3 transferase-CT04 (Rho GTPase Inhibitor) was purchased from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO). Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (complete, Mini, EDTA-free) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets (Phosphostop) were from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). MEK inhibitor U-0126 was from Promega (Madison, WI). Rabbit anti-fibronectin, anti-tenascin C, and anti-laminin antibodies were generous gifts from Harold P. Erickson (Department of Cell Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC). Y-27632 and SB-220025 were from Welfide (Japan) and Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ), respectively.

TM cell cultures.

Human primary TM cells were cultured from the TM tissue isolated from the freshly obtained corneal rings given away after they had been used for the corneal transplantation at the Duke Ophthalmology clinical service. Initially, the extracted TM tissue was chopped into small pieces in serum, and then the tissue slices were placed under a glass coverslip in a six-well plastic culture plates and cultured in DMEM containing 20% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine. Expanded population of TM cells was subcultured after 4–5 days, resulting in the development of a homogenous TM population. All experiments were conducted using confluent cultures of between four and six passages, and cells were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2, in DMEM containing 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine. All experiments were done after serum starvation for at least 24 h unless mentioned.

Adenovirus-mediated gene transduction.

Replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vectors encoding either GFP alone or constitutively active RhoA (RhoAV14) and GFP were provided by Patrick Casey (Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University School of Medicine).

For short hairpin RNA (shRNA) experiments, replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing shRNA against SRF (Ad-shSRF) or the control adenovirus expressing shRNA against GFP (Ad-shGFP) were kindly provided by Joseph Miano (University of Rochester School of Medicine) and were described previously (8). The viral vectors were amplified as described earlier by our group (63). Human TM (HTM) cells grown either on gelatin-coated glass coverslips or in plastic Petri dishes were infected with adenoviral vectors for respective experiments at ∼50 multiplicity of infection. When cells showed adequate transfection (>80%, as assessed based on GFP fluorescence) usually after nearly 24–36 h, cells were serum starved for 24 h to be used in the experiments.

Rho inhibition assays.

Serum-starved HTM cells (24 h) were treated with 1.0 μg/ml of cell-permeable C3 transferase (Rho GTPase inhibitor) for 6 h. This time was enough to induce a robust change in cell morphology. For the rescue experiments, HTM cells treated initially with C3 transferase for 4 h were stimulated with LPA (5 μg/ml) or TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml) for 2 h.

Myosin light-chain phosphorylation assay.

The effects of RhoAV14 and TGF-β2 on phosphorylation status of myosin light chain (MLC) on confluent HTM cell cultures (serum starved for 48 h) were determined by urea-glycerol gel electrophoresis as described earlier by our group (63). After the treatments, the confluent cell cultures were extracted with cold 10% trichloroacetic acid, and cell precipitates collected after centrifugation at 13,000 rpm were washed and finally dissolved by sonicating in 8 M urea buffer. The protein was separated on urea-glycerol gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters. The filters were then subjected to immunoblot using anti-phospho-MLC2 antibody, and blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system.

Immunoblotting.

Total protein and membrane-rich fractions (40,000 rpm insoluble pellet) were isolated from serum-starved confluent cultures of HTM cells with or without treatments. Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (catalog number 500-0006) was used to estimate protein concentration. Samples containing equal amounts of protein were mixed with Laemmli buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE (either 10% or 5.5% acrylamide), followed by transfer of resolved proteins to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then blocked for 2 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk. Membranes were then probed with primary antibodies in conjunction with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Detection of immunoreactivity was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence. Densitometry of scanned films was performed using NIH Image software. Data were normalized to the loading controls (β-tubulin).

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy.

TM cells were grown on gelatin-coated glass coverslips until they attained confluency. After appropriate treatments, cells were washed in PBS twice and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After fixing, washing, permeabilizing, and blocking were completed, cells were incubated with the respective primary and Alexa fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h each at room temperature as described earlier by our group (40). Later, the coverslips were washed and mounted onto glass slides with Aqua Mount (Lerner Laboratories, Pittsburg, PA). The slides were observed under a Nikon confocal system (C1 Digital Eclipse), and z-stack images were collected and processed.

Fibronectin coating.

Fibronectin-coated plastic plates were prepared as described earlier by our group (63), by coating 100 mm × 20 mm Corning cell culture dishes overnight with 20 μg/ml of fibronectin in sterile PBS. For the controls, the plates were treated with PBS alone. Excess ECM was removed by rinsing the plates three times with PBS. HTM cells or HTM cells expressing shGFP or shSRF in serum-free medium were directly plated onto either the ECM-coated plates or PBS-treated plates and incubated for 8 h at 37°C. After 8 h, the cells were scraped and lysed, and the total protein was immunoblotted.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as per the user manual from HTM cells treated with shSRF or the control shRNA (shGFP). Five micrograms of total RNA were used for first-strand synthesis using Superscript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA was amplified in a total volume of 50 μl with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2 U Taq polymerase (Life Technologies), and 0.5 μM of sense and antisense primers for SRF. The control reaction was done with GAPDH primers separately. The primer sequences were as follows: human SRF forward, 5′ GCC ACT GGC TTT GAA GAG AC 3′; human SRF reverse, 5′ CCA GAT GAT GCT GTC AGG AA 3′; GAPDH forward, 5′ TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC 3′; and GAPDH reverse, 5′ GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG 3′.

Amplification was done using the primers mentioned above with the following PCR program: initial denaturizing step at 94°C for 4 min, which was then followed by 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 30 cycles and a final step at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis.

All data represent the average results of at least three independent experiments. Quantitative data were analyzed by the Student's t-test, and minimum values of P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

RhoAV14-induced changes in actin cytoskeletal organization and ECM synthesis/assembly in TM cells.

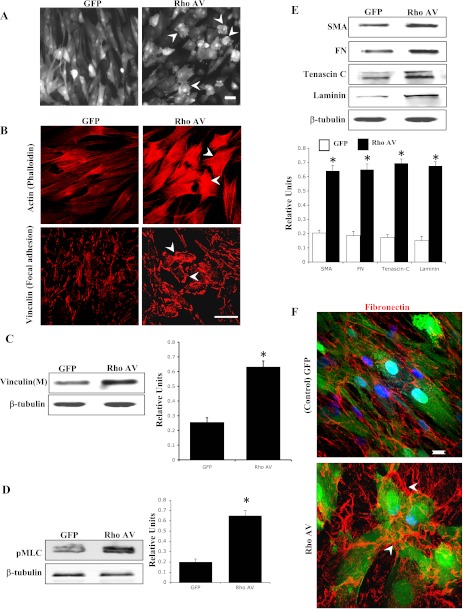

To understand the effects of Rho GTPase on the cytoskeletal architecture, ECM synthesis, and matrix assembly in TM cells, we expressed a constitutively active RhoA (RhoAV14/GFP) or GFP alone in HTM cells using recombinant adenoviral vectors. After 24 h of viral vector infection (>80% infection efficiency based on GFP expression), the TM cells were serum starved for 24 h and monitored for changes in cell morphology using a phase contrast microscope. The RhoAV14 expressing TM cells exhibited stiffened and contractile morphology with obvious cell retraction compared with GFP expressing control cells (Fig. 1A). This change in cell morphology was associated with a robust increase in actin stress fibers (phalloidin staining) and focal adhesion formation (vinculin staining) in RhoAV14-expressing TM cells (Fig. 1B). Additionally, immunoblot analysis of the membrane-rich fraction of the RhoAV14-expressing TM cells showed significantly increased levels of vinculin compared with that shown in GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 1C). Similarly, analysis of MLC phosphorylation in the RhoAV14-expressing HTM cells showed a marked increase compared with that shown in control cells (Fig. 1D). Moreover, quantitative immunoblot analysis of cell lysates derived from the RhoAV14-expressing TM cells showed significantly increased levels of fibronectin, laminin, tenascin C, and α-SMA proteins compared with that shown in control cells expressing GFP alone (Fig. 1E). The RhoAV14-expressing TM cells also revealed increased filamentous and bundled organization (fibrils) of the fibronectin compared with that shown in the untreated control cells (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

RhoAV14-induced changes in actin cytoskeletal organization and extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis/assembly in human trabecular meshwork (HTM) cells. Serum-starved HTM cells transduced with an adenoviral vector expressing RhoAV14/GFP exhibit contractile cell morphology (A), increased actin stress fibers and focal adhesions (B), increased vinculin membrane localization (C), increased myosin-light chain phosphorylation (pMLC; D), increased levels of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and increased levels of ECM proteins [fibronectin (FN), laminin, tenascin C] (E), and increased ECM assembly or fibril formation (F) compared with that shown in cells expressing GFP alone. Representative images were drawn from multiple independent analyses. Histograms show significant differences between treated and untreated cells at a minimum of P < 0.05 based on triplicate analyses. *Statistical significance (minimum P < 0.05) between the control and RhoAV14-expressing cells. Bars (50 μm in A and B, 10 μm in F) indicate image magnification. β-Tubulin levels were assessed to control for loading uniformity.

LPA and TGF-β2-induced changes in actin cytoskeletal organization and ECM synthesis/assembly in TM cells.

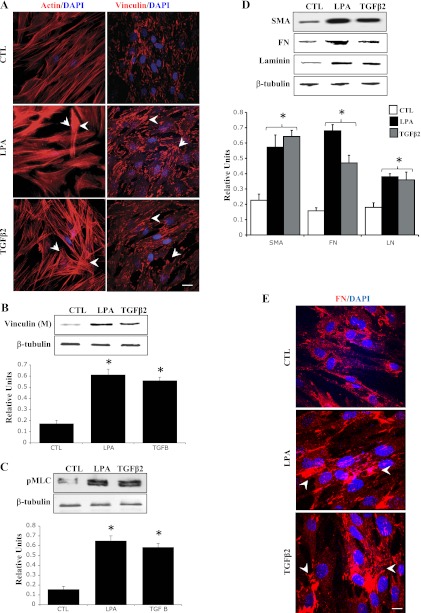

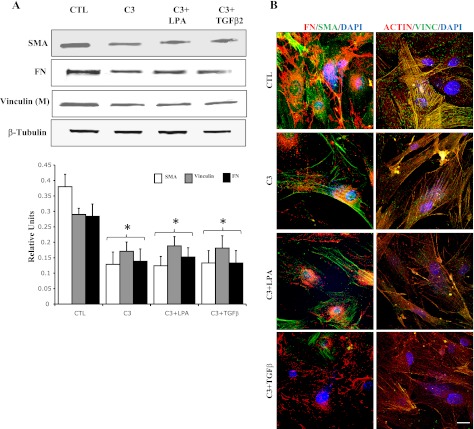

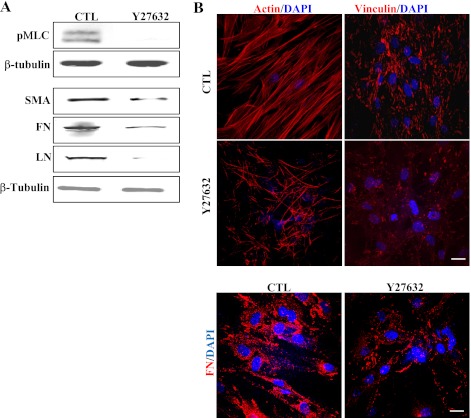

In addition to assessing direct effects of activated RhoA on TM cell actomyosin and ECM organization, we also evaluated the effects of TGF-β2 and LPA on these cellular events. The reason for choosing these two physiological agonists was that these agents have been shown to increase the resistance to aqueous humor outflow in perfusion models (16, 33), and they activate Rho/Rho kinase signaling in various cell types, including TM cells (37, 39). Serum-starved HTM cells treated with LPA (5 μg/ml) and TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 2 h exhibited increased actin stress fibers and focal adhesion formations (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, similar to RhoAV14, these changes were associated with increased MLC phosphorylation and increased levels of vinculin in the membrane-enriched fraction (Fig. 2, B and C). Moreover, both LPA- and TGF-β2-treated TM cells also revealed increased levels of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA compared with that shown in untreated control cells (Fig. 2D). Again, as in the case of RhoAV14-expressing cells, TGF-β2- and LPA-treated HTM cells exhibited increased and compact assembly of fibronectin compared with that shown in untreated control cells (Fig. 2E). Moreover, pretreatment of HTM cells with Rho GTPase inhibitor (C3 transferase; 1.0 μg/ml) for 6 h suppressed the TGF-β2- and LPA-induced increases in the levels of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA, (Fig. 3A) in association with decreased actin stress fibers and focal adhesions (Fig. 3B), indicating the significance of Rho GTPase activity in the regulation of ECM synthesis and assembly and expression of α-SMA (contractile activity-regulating protein) mediated by LPA and TGF-β2. In addition, treatment of HTM cells with an inhibitor of Rho kinase (10 μM Y-27632 for 2 h), a downstream kinase effecter of Rho GTPase (14), led to decreases in the levels of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA in association with decreased actin stress fibers, focal adhesions, and MLC phosphorylation compared with that shown in untreated control cells (Fig. 4, A and B), further supporting a definite role for Rho/Rho kinase pathway and actomyosin in ECM synthesis and assembly.

Fig. 2.

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)- and TGF-β2-induced changes in HTM cell actin cytoskeletal organization and ECM synthesis. Serum-starved HTM cells were treated with LPA (5 μg/ml) or TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml) for 2 h and examined for changes in F-actin distribution (phalloidin staining), focal adhesion formation (vinculin staining), pMLC, and levels of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA. Both LPA and TGF-β2 induced formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions (A). Both agonists also increased vinculin membrane localization (B), pMLC (C), and protein levels of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA (D) compared with that shown in untreated control (CTL) cells. Additionally, immunostaining of fibronectin and laminin was found to be much more intense in LPA- and TGF-β2-treated HTM cells compared with that shown in control cells (E). Histograms depict quantitative changes in indicated proteins based on triplicate analyses. *Significant differences (at a minimum of P < 0.05) between treated and untreated cells. Bars (10 μm) represent image magnification. β-Tubulin was immunoblotted for loading uniformity.

Fig. 3.

Effects of RhoA inhibition on LPA- and TGF-β2-induced changes in actin cytoskeletal organization and ECM and α-SMA expression in HTM cells. Serum-starved HTM cells were treated with cell-permeable C3 transferase (inhibitor of Rho GTPase, 1 μg/ml) for 6 h and evaluated for actin cytoskeleton reorganization, focal adhesions formation, changes in protein levels of fibronectin and α-SMA, and levels of membrane-associated vinculin. C3 transferase treatment reduced actin stress fibers (B), focal adhesions (B), and vinculin membrane localization (A). Levels of both fibronectin and α-SMA were reduced significantly (A). Additionally, effects of C3 transferase on actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesions, fibronectin, and α-SMA were not rescued by the addition of LPA or TGF-β2. Quantitative changes (histograms) were based on triplicate analyses. Bar (10 μm) indicates magnification. *Significant differences (at a minimum of P < 0.05) between treated and untreated cells. β-Tubulin was immunoblotted for loading uniformity.

Fig. 4.

Effects of Rho kinase inhibitor on actin cytoskeletal organization, pMLC, and ECM synthesis/organization in HTM cells. HTM cells treated with Rho kinase inhibitor (10 μM Y-27632 for 2 h) exhibited a marked decrease in actin stress fibers, focal adhesions, and fibronectin (A). Additionally, levels pMLC, α-SMA, fibronectin, and laminin were reduced dramatically in Y-27632-treated HTM cells compared with that shown in control cells (B). β-Tubulin was probed as a loading control. Bars (10 μm) indicate image magnification.

RhoA-, TGF-β2-, and LPA-induced Erk activation in TM cells.

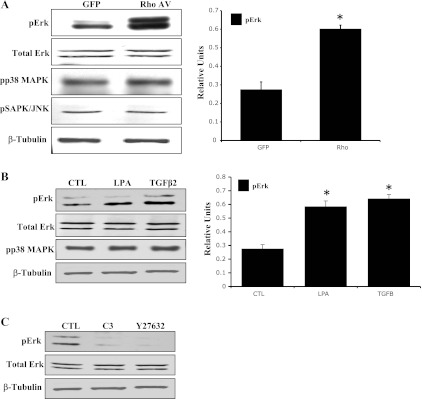

After noting the effects of RhoAV14, LPA, and TGF-β2 on ECM synthesis and assembly in association with an actomyosin assembly-mediated increase in contractile activity in TM cells, we looked further into the identity of downstream signaling events that may aid Rho GTPase-induced ECM synthesis. For this, we assessed the effects of RhoAV14, LPA, and TGF-β2 on the activation status of the MAPKs p38, JNK, and Erk1/2, in HTM cells. HTM cells transfected with RhoAV14 for 24 h and serum starved for 24 h or serum-starved HTM cells stimulated with TGF-β2 or LPA for 2 h exhibited significant increases in Erk1/2 phosphorylation (activation) compared with that shown in untreated control cells (Fig. 5, A and B). On the other hand, both p38 MAPK and JNK did not reveal any changes in phosphorylation status under similar conditions (data on JNK not shown). The protein levels of total Erk1/2 did not change in response to any of the above described treatments (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the levels of phospho-Erk1/2 were found to be markedly decreased in wild-type HTM cells treated with either Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632 for 2 h) or Rho GTPase inhibitor (C3 transferase for 4 h), indicating the importance of the Rho/Rho kinase pathway in regulation of Erk activation in TM cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

RhoA, LPA, and TGF-β2-induced Erk activation in HTM cells. Serum-starved HTM cells expressing RhoAV14 for 24 h or stimulated either with LPA (5 μg/ml for 2 h) or with TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml for 2 h) exhibited significant increases in the levels of phospho-Erk1/2 (pErk) compared with that shown in untreated controls. Total Erk1/2 protein levels were similar between the treated and untreated control cells. Additionally, inhibition of RhoA (C3 transferase, 1 μg/ml for 4 h) and Rho kinase (Y-27632, 10 μM for 2 h) led to a decrease in pErk protein levels in HTM cells. Levels of phospho-p38 (pp38) MAPK and JNK were unaltered by RhoA, LPA, and TGF-β2 in serum-starved TM cells. Histograms derived from triplicate analyses show that RhoAV14, LPA, and TGF-β2 induce quantitative changes in Erk activation. *Significant difference (at minimum of P < 0.05) between the treated and untreated cells. β-Tubulin levels were assessed for loading uniformity.

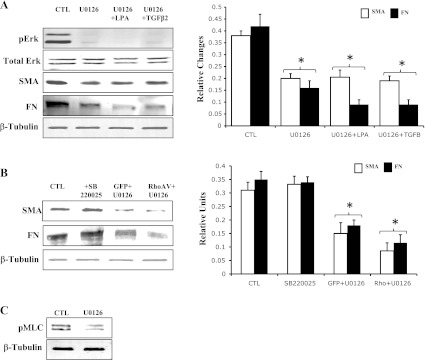

Effects of Erk inhibition on ECM synthesis and α-SMA in TM cells.

Wild-type HTM cells treated for 4 h with U-0126, a highly selective inhibitor of Erk1/2 (12), exhibited marked decreases in phospho-Erk1/2 levels (Fig. 6A). Importantly, treatment with U-0126 also resulted in significant reductions in levels of both fibronectin and α-SMA proteins in wild-type HTM cells compared with that shown in untreated controls (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the inhibition of fibronectin or α-SMA expression by Erk inhibitor was not rescued by LPA, TGF-β2, or RhoAV14 (Fig. 6, A and B). On the other hand, a selective inhibitor of p38 MAPK (SB-220025) showed no effects on the expression of fibronectin or α-SMA (Fig. 6B) in normal HTM cells. Interestingly, the U-0126-induced changes in fibronectin and α-SMA expression were also associated with decreases in MLC phosphorylation (Fig. 6C) and in actin stress fibers (not shown) in normal HTM cells. Collectively, these observations imply a critical role for Erk activation in fibronectin and α-SMA expression in TM cells under both normal and TGF-β2-, LPA-, and RhoA-stimulated conditions.

Fig. 6.

Effects of Erk inhibition on the expression of fibronectin and α-SMA in HTM cells. Serum-starved HTM cells treated with Erk inhibitor (U-0126; 25 μM for 4 h) revealed dramatic reduction in pErk (A). Protein levels of both fibronectin and α-SMA were found to be significantly decreased in U-0126-treated TM cells (A). Furthermore, stimulation of TM cells with TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml) or LPA (5 μg/ml) for 2 h (A) or transfection with RhoAV14 (B) failed to reverse the effects of Erk inhibitor on fibronectin and α-SMA expression. Furthermore, Erk inhibitor (U-0126) alone was found to decrease the levels of pMLC in HTM cells (C). *Significant changes (with minimum of P < 0.05) between treated and untreated cells based on triplicate analyses. β-Tubulin was probed as a loading control.

RhoA- and TGF-β2-regulated ECM and α-SMA expression via SRF expression.

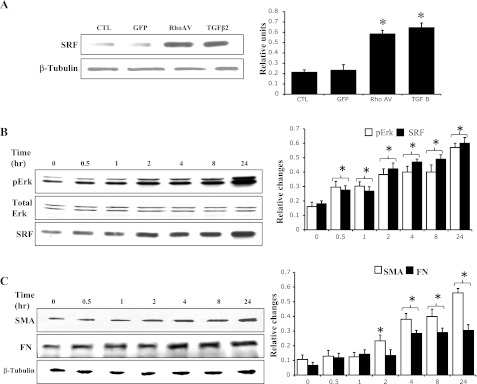

In addition to a direct role in regulation of cytoskeletal organization and function, Rho GTPase controls the activity of the myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTF-A and MRTF-B), which are transcriptional coactivators of the transcription factor SRF (35, 54). SRF has been recognized to serve as a master control element in the expression of various cytoskeletal proteins, including α-SMA (34). To obtain further insight into the regulation of fibronectin and α-SMA expression by Rho GTPase and TGF-β2, we determined the effects of both RhoAV14 and TGF-β2 on SRF expression in HTM cells. HTM cells expressing the constitutively active RhoAV14 exhibited a significant increase in SRF protein levels compared with GFP-expressing controls (Fig. 7A). Similarly, serum-starved wild-type HTM cells treated with TGF-β2 for 2 h revealed significant increases in SRF expression (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Effects of RhoA and TGF-β2 on serum response factor (SRF) expression in HTM cells. A: serum-starved HTM cells either expressing RhoAV14 or treated with TGF-β2 (4 μg/ml for 2 h) revealed significant increases in SRF levels. B: time-dependent response of TM cells to TGF-β2 (2 ng/ml) as assessed by Erk activation and SRF expression. C: time-dependent effect of TGF-β2 on fibronectin and α-SMA expression. Unlike Erk activation and SRF expression, protein levels of fibronectin and α-SMA were found to exhibit a lag time of 2 h before increasing significantly. Histogram results are mean of triplicate analyses. *Significant difference (at minimum of P < 0.05) between the treated and untreated cells. β-Tubulin was blotted as a loading control.

Additionally, to understand whether a sequential and kinetic relationship exists between the TGF-β2-induced expression of fibronectin, SRF, α-SMA, and Erk activation in HTM cells, serum-starved wild-type HTM cells were stimulated with TGF-β2 and monitored for time-dependent changes in the levels of fibronectin, SRF, α-SMA, and Erk activation. Interestingly, both SRF expression and Erk activation exhibited an early and parallel response that is evident at 30 min following stimulation and continuing over a 24-h period (Fig. 7B). On the other hand, the expression of fibronectin and α-SMA exhibited a lag time of 2–4 h, after which there was a significant induction of expression (Fig. 7C). However, unlike the expression profile of α-SMA whose expression continued to increase up to 24 h after an initial lag, fibronectin expression peaked between 4 and 8 h of TGF-β2 stimulation and plateaued thereafter (Fig. 7C). These data indicate that the expression of SRF and Erk activation precedes and may be a prerequisite for the induction of expression of α-SMA and fibronectin in TGF-β2-stimulated HTM cells.

SRF and regulation of α-SMA and fibronectin in HTM cells.

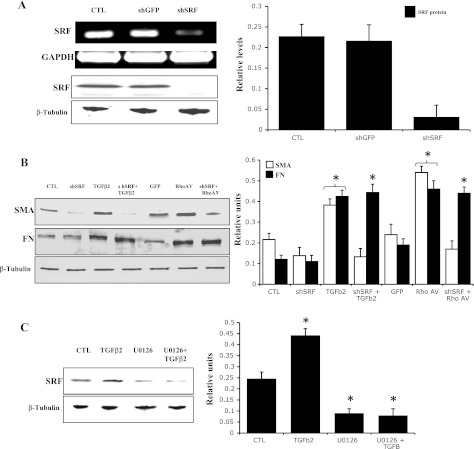

To further investigate the potential role of SRF in regulation of α-SMA and fibronectin expression, we utilized a knockdown approach based on adenovirus-mediated expression of shRNA against SRF (Ad-shSRF). Treatment of wild-type HTM cells with Ad-shSRF for 24 h significantly knocked down the expression of SRF mRNA (Fig. 8A, top) and protein (Fig. 8A, row 3) compared with control cells treated with shRNA against GFP (Ad-shGFP). As shown in Fig. 8B, knocking down of SRF in HTM cells led to significant decrease in the levels of α-SMA. Importantly, the shSRF-induced suppression of α-SMA expression was not rescued by either TGF-β2 or RhoAV14, indicating a critical role for SRF in the regulation of TGF-β2 and RhoAV14-induced expression of α-SMA in HTM cells (Fig. 8B). TGF-β2- and RhoAV14-induced expression of fibronectin in HTM cells, on the other hand, appears not to be dependent on SRF expression (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, inhibition of Erk activation in HTM cells decreased SRF protein levels, an effect that was not rescued by TGF-β2, indicating a requirement for Erk activity in the TGF-β2-induced expression of SRF (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Effects of SRF suppression on expression of α-SMA and fibronectin in HTM cells. To determine the role of SRF in regulation of expression of α-SMA and fibronectin in HTM cells, HTM cells were transfected with adenoviral vectors expressing SRF short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or GFP shRNA for 24 h and serum starved, prior to analyzing cell lysates for changes in levels of SRF, α-SMA, and fibronectin by immunoblot analysis. A: dramatic decrease (>90%) in both SRF expression (RT-PCR analysis-based quantitation of mRNA) and SRF protein levels (immunoblot analysis) in HTM cells treated with SRF-specific shRNA compared with a GFP-specific shRNA control. B: levels of α-SMA were found to be significantly reduced in the SRF shRNA-treated cells compared with that shown in cells treated with the GFP shRNA control. However, fibronectin protein levels were found to be similar between the SRF shRNA- and GFP shRNA-treated cells. Interestingly, although treating the SRF shRNA-expressing cells with either RhoAV14 or TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml for 2 h) failed to rescue the decreases in α-SMA protein levels, suppressed expression of SRF did not influence fibronectin protein levels induced by both RhoAV14 and TGF-β2 (B). These observations indicate that, although expression of SRF is obligatory for the regulation of α-SMA expression, fibronectin expression appears to be regulated independent of SRF. C: effects of Erk inhibition on SRF expression in TGF-β2-treated and untreated HTM cells. HTM cells treated with Erk kinase inhibitor (25 μM U-0126 for 4 h) exhibited significant reductions in SRF protein levels, and TGF-β2 (4 ng/ml for 2 h) failed to rescue the Erk inhibitor-induced decrease in SRF expression, indicating that Erk acts upstream of SRF and regulates SRF expression in HTM cells. Histogram results show significant differences (at minimum of P < 0.05) between the treated and untreated controls based on triplicate analyses. β-Tubulin was probed to confirm equal loading of protein between the treated and untreated specimens for the immunoblots.

Effects of fibronectin on α-SMA, SRF expression, and Erk activation in HTM cells.

To determine whether the ECM exerts a possible feedback effect on the expression of SRF, α-SMA, or Erk activation, control HTM cells or HTM cells expressing shGFP or shSRF suspended in serum-free medium were plated onto either fibronectin-coated or control (PBS-treated) plates. As reported by us in earlier studies (63), serum-starved HTM cells cultured on fibronectin-coated plates exhibited a spread-out morphology, whereas control cells cultured on PBS-treated plates showed rounded morphology (data not shown). Immunoblot analyses of fibronectin-stimulated HTM cells or HTM cells expressing shGFP revealed significant increases in levels of α-SMA, SRF, and phospho-Erk compared with control cells cultured on PBS-treated plates (Fig. 9). Contrarily, shSRF-expressing cells plated on fibronectin-coated plates showed little changes in levels of α-SMA, SRF, and phospho-Erk levels (Fig. 9). Furthermore, suppression of SRF expression in control TM cells reduced the basal levels of α-SMA and phospho-Erk (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Fibronectin-induced α-SMA, SRF expression, and Erk activation in HTM cells. To determine the effects of ECM on the expression of α-SMA, HTM cells or HTM cells expressing shRNA against GFP (shGFP) or shRNA against SRF (shSRF) in serum-free medium were plated onto either fibronectin-coated plates or PBS-treated plates; after 8 h, cell lysates were prepared and examined for changes in the levels of α-SMA, SRF, and pErk by immunoblot analyses. A: representative immunoblot for changes in α-SMA, pErk, and SRF. B: quantitative immunoblot analysis showing significant increases in the levels of α-SMA, which was paralleled by induction of Erk and SRF expression in fibronectin-stimulated HTM cells. shSRF-expressing cells either plated on PBS-treated or fibronectin-coated plates showed little changes in α-SMA, pErk, and SRF levels. Histograms show significant differences (at minimum of P < 0.05) between the fibronectin-treated and PBS-treated controls based on triplicate analyses. β-Tubulin was probed to confirm equal loading of protein between the treated and untreated specimens for the immunoblots.

DISCUSSION

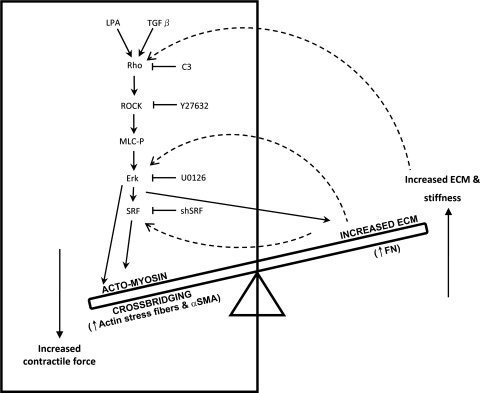

The primary goal of this study was to understand the mechanistic basis by which Rho GTPase controlled actomyosin contractile activity regulates ECM synthesis and assembly in the context of homeostasis of aqueous humor resistance in the trabecular pathway. The major findings of this study include 1) Rho GTPase-induced actomyosin assembly and contractile activity stimulates ECM synthesis and assembly and α-SMA expression in TM cells; 2) Erk activation appears to be critical for RhoA-, LPA- and TGF-β2-induced ECM and α-SMA expression; 3) although RhoA-, LPA-, and TGF-β2-induced SRF expression downstream to Erk appears to be critical for the regulation of α-SMA, Erk activation alone induced by RhoA, LPA, and TGF-β2 is sufficient for the regulation of fibronectin expression in TM cells; and 4) fibronectin via feedback activation induces α-SMA expression in association with increased SRF expression and Erk activation in TM cells. Collectively, these observations support existence of a potential bidirectional interplay and balance between Rho GTPase-regulated contractile force and ECM-derived mechanical tension in the pressure-sensitive TM cells and suggest that this interplay between contractile activity and ECM synthesis/assembly in the cells of aqueous humor outflow pathway, including TM, SC, and JCT, represents a crucial regulatory component in the homeostasis of aqueous humor outflow resistance, as depicted schematically in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Schematic illustration of a potential bidirectional molecular interplay between Rho GTPase-regulated contractile activity and ECM-derived mechanical force in trabecular meshwork cells. Rho/Rho kinase signaling and ECM appear to regulate ECM synthesis/assembly and contractile activity through feedforward and feedback mechanisms, respectively.

Aqueous humor drainage via a pressure-sensitive trabecular pathway is believed to be a major route of total outflow in a normal eye (15, 48). Among the various factors that influence the resistance to aqueous humor outflow, ECM accumulation is considered to play a predominant role (1, 24, 28, 49). Alterations in ECM content and organization have been found to be associated with increased resistance in the outflow pathway of human glaucomatous eyes (24, 28, 49, 62). Furthermore, perfusion of ECM-degrading matrix metalloproteinases has been shown to increase aqueous humor outflow facility through the trabecular pathway, indicating the importance of ECM turnover in the homeostasis of aqueous humor outflow resistance (5, 24). Similarly, the integrity of actin cytoskeletal organization and the contractile characteristics of trabecular outflow pathway have been shown to modulate aqueous humor outflow facility (41, 51, 58). Of particular note, agents that affect myosin II activity and actin polymerization have been reported to influence aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular pathway, implying an important role for TM, JCT, and SC tissue contractile and relaxation properties in the regulation of aqueous humor outflow resistance (11, 41, 51, 64). To this end, activators and inhibitors of the Rho/Rho kinase pathway, one of the predominant signaling pathways that regulate cellular contraction (47), have been shown to exert contrasting effects on aqueous humor outflow, with activators increasing and inhibitors decreasing outflow resistance (41). Importantly, in our recent study, expression of constitutively active RhoA in the trabecular outflow pathway was found to increase outflow resistance in a response associated with increased actomyosin assembly and with increased expression of various ECM-related genes and cytokines such as TGF-β, interleukin-1, and connective tissue growth factor in TM cells, indicating a potential interaction between Rho GTPase-induced actomyosin assembly and ECM synthesis (63). The mechanistic underpinnings of this association between the activity of Rho/Rho kinase pathway and ECM synthesis in outflow pathway cells, however, have not been unraveled, and, in this study, we attempted to explore the potential molecular interplay between actomyosin contractile activity and ECM turnover in TM cells.

HTM cells expressing a constitutively activated form of RhoA (RhoAV14), which exhibited a visually notable contractile morphology with increased actin stress fibers, vinculin membrane targeting, and MLC phosphorylation, demonstrated increased levels of fibronectin, fibronectin fibril formation, laminin, tenascin C, and α-SMA. Furthermore, the morphological changes and changes in expression of ECM proteins were suppressed by the Rho GTPase inhibitor (C3 transferase) and Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632), in association with decreased MLC phosphorylation, actin stress fibers, focal adhesions, and fibronectin fibrils. These observations suggest that TM cells sense RhoAV14-induced contractile activity and perhaps cytoskeletal tension and that this in turn induces ECM synthesis and assembly, which can in effect serve to increase mechanical force to counteract the actomyosin-derived contractile tension and cell retraction (7, 42). α-SMA has been thought to serve as a mechanotransducer, based on its ability to physically link mechanosensory elements and to enhance its own force-induced expression (55). Rho GTPase activation is known to induce α-SMA expression and assembly in other cell types as well (30, 55). As in the case of TM cells (63), the Rho/Rho kinase pathway has been shown to induce ECM synthesis in other mechanosensing cell types, including vascular endothelial cells and fibroblasts (2, 6, 43). In addition, mechanical stress, shear stress, and ECM stiffness have been recognized to influence Rho GTPase activity in different cell types, indicating an existence of a potential feedforward and feedback interplay between Rho-regulated myosin II contractile tension and ECM-derived mechanical force/rigidity (3, 4, 20, 23, 46, 52). The feedback response from ECM to Rho GTPase activation and contractile activity was supported partly by our previous data (63) on ECM-induced Rho GTPase activation and myosin II phosphorylation, along with data presented in this study on fibronectin-induced α-SMA expression in TM cells.

In addition to the direct effects of RhoAV14, stimulation of TM cells with physiological agonists such as LPA and TGF-β2, which are known to induce Rho GTPase activation and MLC phosphorylation in TM and other cell types (18, 33, 36–38), leads to an increase in levels of fibronectin, fibronectin fibrils, laminin, and α-SMA in a RhoA- and Rho kinase-dependent manner. Pretreatment of TM cells with Rho GTPase inhibitor (C3 transferase) suppressed the LPA- and TGF-β2-induced increases in expression of fibronectin, laminin, and α-SMA and caused decreases in actin stress fibers, focal adhesions, and MLC phosphorylation, further confirming the participation of Rho GTPase activity in LPA- and TGF-β2-induced changes in ECM and α-SMA. Interestingly, perfusion with both LPA and TGF-β2 has been reported to decrease aqueous humor outflow facility (16, 33) in enucleated eyes. In the case of TGF-β2, increased resistance to aqueous humor outflow is reported to be associated with increased levels of synthesis of ECM components (13, 27, 49). Our observations regarding the direct effect of RhoAV14 and those of Rho GTPase activating agonists on expression of fibronectin, fibronectin assembly, α-SMA expression, actin stress fibers, and myosin II activity in TM cells collectively uncovers the significance of Rho/Rho kinase signaling, cell contractile activity, and mechanotransduction in homeostasis of ECM synthesis, and α-SMA expression.

To obtain further insight into the downstream molecular basis for RhoA-induced ECM synthesis and α-SMA expression in TM cells, we explored the possible involvement of the MAPKs and transcriptional factors by examining the activation status of the Erk, JNK, and p38 kinases and expression levels of the transcriptional factor SRF. Rho GTPase, in addition to its well-recognized role in actin dynamics and cell adhesion, participates in numerous cellular processes, including gene expression and transcriptional regulation via signaling pathways involving the MAPKs and SRF and NF-κB (21). TM cells treated with RhoAV14, TGF-β2, or LPA exhibited increases in Erk1/2 activation and SRF expression. Moreover, inhibitors of both Rho GTPase (C3 transferase) and Rho kinase (Y-27632) suppressed Erk activation in TM cells, revealing the significance of Rho/Rho kinase-regulated actin dynamics and contractile activity in Erk activation. Although the Rho GTPases are also known to regulate p38 and JNK activation under different conditions, these kinases are preferential targets of the Rac and Cdc42 GTPases (21). Rho/Rho kinase-induced fibronectin and tenascin C synthesis has been documented to depend on the Erk activity in other cell types (3, 6).

To understand the significance of Erk activation and SRF expression for regulation of ECM synthesis and α-SMA expression in TM cells, Erk activity was targeted using a pharmacological inhibitor, whereas SRF expression was suppressed using shRNA. Treatment of wild-type HTM cells with Erk inhibitor led to decreases in the basal levels of fibronectin and α-SMA. Furthermore, the Erk inhibitor-induced decreases in basal levels of expression of fibronectin and α-SMA levels were not rescued by either RhoAV14, TGF-β2, or LPA, indicating a critical role for Erk activity in regulating fibronectin and α-SMA expression in HTM cells. Similar to the effects of the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632, the Erk inhibitor U-0126 also caused cell shape changes in HTM cells in association with decreased actin stress fibers (data not shown) and MLC phosphorylation. This is consistent with the documented effects of Erk inhibitor on MLC phosphorylation and actin cytoskeletal organization in other cell types (9, 25, 61). The similar but independent effects of inhibitors of Rho kinase and Erk on the expression of fibronectin and α-SMA in association with decreased actin stress fibers and cell shape changes points out the significance of myosin II-derived contractile force in the regulation of fibronectin and α-SMA expression. Our observations regarding the role of Erk activity in the regulation of expression of fibronectin and other ECM molecules in TM cells are consistent with published observations in which TGF-β2 and other cytokines have been shown to stimulate fibronectin expression in an Erk-dependent manner in different cell types (31, 44, 59). Very recently, ECM rigidity has been reported to increase fibronectin fibril formation, Erk activation, focal adhesion kinase activity, α-SMA, and actin stress fibers in TM cells, further reiterating the significance of mechanotransduction in the aqueous humor outflow pathway (45).

In addition to involvement of Erk activation in TM cell ECM synthesis and α-SMA expression, SRF expression was noted to be increased in RhoAV14- and TGF-β2-stimulated TM cells, indicating a potential role for SRF in this response. SRF, a transcription factor whose activity depends on the ratio of filamentous actin to monomeric G-actin and on Rho GTPase activity, regulates expression of various cytoskeletal proteins, including actin and immediate early genes in different cell types (26, 32, 34). When Rho GTPase is activated, the G-actin levels are reduced; under this condition, myocardin, the co-activator of SRF, translocates to the nucleus and activates the SRF (32). Reduction of SRF expression in TM cells via shRNA leads to significant decreases in the levels of α-SMA. Furthermore, both RhoAV14 and TGF-β2 failed to rescue the expression of α-SMA when SRF levels were reduced in TM cells, indicating a critical requirement for SRF in the expression of α-SMA. On the other hand, RhoAV14- and TGF-β2-induced expression of fibronectin was found to be unaffected by the decreased levels of SRF, indicating that SRF is not an obligatory factor in the regulation of fibronectin expression in TM cells. Activation of Erk and increased SRF expression appear to precede the expression of fibronectin and α-SMA based on the kinetics of these events in TM cells. Additionally, Erk seems to act upstream of SRF in regulating expression of α-SMA and fibronectin in TM cells, possibly through different downstream mechanisms. For example, Erk has been shown to phosphorylate myocardin, a coactivator of SRF (50), and Elk-1, a transcription factor involved in ECM synthesis and turnover (10).

In conclusion, the results of this study reveal that TM cells appear to sense the actomyosin-derived contractile force and induce ECM synthesis/assembly and, conversely, that ECM assembly/rigidity influences actomyosin contraction via Rho GTPase activation (63) and α-SMA expression to maintain a bidirectional balance between cell-induced contractile tension and ECM mechanical force. This molecular interplay between contractile activity and ECM synthesis could play a significant role in homeostasis of aqueous humor drainage by influencing the cell and tissue stiffness within the outflow pathway. Importantly, regulation of Rho/Rho kinase signaling activity appears to play a crucial role in cells of the aqueous humor outflow pathway by linking the actomyosin-regulated contractile activity with expression of ECM proteins and α-SMA, in addition to its well-recognized role in actin cytoskeletal organization, cell shape, and cell adhesive interactions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute R01 Grants EY-018590 and EY-12201 (to P. V. Rao) and National Eye Institute P30 Grant EY-005722.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Patrick Casey and Harold Erickson for providing the adenoviral vectors expressing RhoAV14 and GFP and ECM (fibronectin, tenascin C, and laminin) antibodies, respectively. We also thank Dr. Joseph Miano for providing the Ad-shSRF and Ad-shGFP and Dr. David Epstein for insightful discussion during these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acott TS, Kelley MJ. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res 86: 543–561, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhmetshina A, Dees C, Pileckyte M, Szucs G, Spriewald BM, Zwerina J, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Rho-associated kinases are crucial for myofibroblast differentiation and production of extracellular matrix in scleroderma fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2553–2564, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asparuhova MB, Gelman L, Chiquet M. Role of the actin cytoskeleton in tuning cellular responses to external mechanical stress. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bershadsky AD, Balaban NQ, Geiger B. Adhesion-dependent cell mechanosensitivity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19: 677–695, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley JM, Vranka J, Colvis CM, Conger DM, Alexander JP, Fisk AS, Samples JR, Acott TS. Effect of matrix metalloproteinases activity on outflow in perfused human organ culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 2649–2658, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapados R, Abe K, Ihida-Stansbury K, McKean D, Gates AT, Kern M, Merklinger S, Elliott J, Plant A, Shimokawa H, Jones PL. ROCK controls matrix synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells: coupling vasoconstriction to vascular remodeling. Circ Res 99: 837–844, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. Cell 88: 39–48, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow N, Bell RD, Deane R, Streb JW, Chen J, Brooks A, Van Nostrand W, Miano JM, Zlokovic BV. Serum response factor and myocardin mediate arterial hypercontractility and cerebral blood flow dysregulation in Alzheimer's phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 823–828, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Angelo G, Adam LP. Inhibition of ERK attenuates force development by lowering myosin light chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H602–H610, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis RJ. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Biol Chem 268: 14553–14556, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein DL, Rowlette LL, Roberts BC. Acto-myosin drug effects and aqueous outflow function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40: 74–81, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 18623–18632, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang IH, Clark AF. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 226–234, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukata Y, Amano M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-Rho-kinase pathway in smooth muscle contraction and cytoskeletal reorganization of non-muscle cells. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22: 32–39, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabelt BT, Kaufman PL. Changes in aqueous humor dynamics with age and glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 24: 612–637, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottanka J, Chan D, Eichhorn M, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Ethier CR. Effects of TGF-β2 in perfused human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 153–158, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn C, Schwartz MA. The role of cellular adaptation to mechanical forces in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 2101–2107, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirayama K, Hata Y, Noda Y, Miura M, Yamanaka I, Shimokawa H, Ishibashi T. The involvement of the rho-kinase pathway and its regulation in cytokine-induced collagen gel contraction by hyalocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 3896–3903, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honjo M, Tanihara H, Inatani M, Kido N, Sawamura T, Yue BY, Narumiya S, Honda Y. Effects of rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor Y-27632 on intraocular pressure and outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 137–144, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingber DE. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J 20: 811–827, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21: 247–269, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnstone MA. The aqueous outflow system as a mechanical pump: evidence from examination of tissue and aqueous movement in human and non-human primates. J Glaucoma 13: 421–438, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaunas R, Nguyen P, Usami S, Chien S. Cooperative effects of Rho and mechanical stretch on stress fiber organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15895–15900, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller KE, Aga M, Bradley JM, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Extracellular matrix turnover and outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res 88: 676–682, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klemke RL, Cai S, Giannini AL, Gallagher PJ, de Lanerolle P, Cheresh DA. Regulation of cell motility by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Cell Biol 137: 481–492, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwahara K, Barrientos T, Pipes GC, Li S, Olson EN. Muscle-specific signaling mechanism that links actin dynamics to serum response factor. Mol Cell Biol 25: 3173–3181, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutjen-Drecoll E. Morphological changes in glaucomatous eyes and the role of TGFβ2 for the pathogenesis of the disease. Exp Eye Res 81: 1–4, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutjen-Drecoll E, Futa R, Rohen JW. Ultrahistochemical studies on tangential sections of the trabecular meshwork in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 21: 563–573, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson M. What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? Exp Eye Res 82: 545–557, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack CP, Somlyo AV, Hautmann M, Somlyo AP, Owens GK. Smooth muscle differentiation marker gene expression is regulated by RhoA-mediated actin polymerization. J Biol Chem 276: 341–347, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maschler S, Grunert S, Danielopol A, Beug H, Wirl G. Enhanced tenascin-C expression and matrix deposition during Ras/TGF-β-induced progression of mammary tumor cells. Oncogene 23: 3622–3633, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medjkane S, Perez-Sanchez C, Gaggioli C, Sahai E, Treisman R. Myocardin-related transcription factors and SRF are required for cytoskeletal dynamics and experimental metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 11: 257–268, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mettu PS, Deng PF, Misra UK, Gawdi G, Epstein DL, Rao PV. Role of lysophospholipid growth factors in the modulation of aqueous humor outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 2263–2271, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miano JM, Long X, Fujiwara K. Serum response factor: master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C70–C81, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell 113: 329–342, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moolenaar WH, van Meeteren LA, Giepmans BN. The ins and outs of lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Bioessays 26: 870–881, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura Y, Hirano S, Suzuki K, Seki K, Sagara T, Nishida T. Signaling mechanism of TGF-β1-induced collagen contraction mediated by bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 3465–3472, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng F, Zhang B, Wu D, Ingram AJ, Gao B, Krepinsky JC. TGF-β-induced RhoA activation and fibronectin production in mesangial cells require caveolae. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F153–F164, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao PV, Deng P, Sasaki Y, Epstein DL. Regulation of myosin light chain phosphorylation in the trabecular meshwork: role in aqueous humour outflow facility. Exp Eye Res 80: 197–206, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rao PV, Deng PF, Kumar J, Epstein DL. Modulation of aqueous humor outflow facility by the Rho kinase-specific inhibitor Y-27632. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 1029–1037, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rao VP, Epstein DL. Rho GTPase/Rho kinase inhibition as a novel target for the treatment of glaucoma. BioDrugs 21: 167–177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarasa-Renedo A, Chiquet M. Mechanical signals regulating extracellular matrix gene expression in fibroblasts. Scand J Med Sci Sports 15: 223–230, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarasa-Renedo A, Tunc-Civelek V, Chiquet M. Role of RhoA/ROCK-dependent actin contractility in the induction of tenascin-C by cyclic tensile strain. Exp Cell Res 312: 1361–1370, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato M, Shegogue D, Hatamochi A, Yamazaki S, Trojanowska M. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits TGF-β-mediated stimulation of type I collagen mRNA stability via an ERK-dependent pathway in dermal fibroblasts. Matrix Biol 23: 353–361, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlunck G, Han H, Wecker T, Kampik D, Meyer-ter-Vehn T, Grehn F. Substrate rigidity modulates cell matrix interactions and protein expression in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 262–269, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shikata Y, Rios A, Kawkitinarong K, DePaola N, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Differential effects of shear stress and cyclic stretch on focal adhesion remodeling, site-specific FAK phosphorylation, and small GTPases in human lung endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 304: 40–49, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev 83: 1325–1358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamm ER. The trabecular meshwork outflow pathways: structural and functional aspects. Exp Eye Res 88: 648–655, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamm ER, Fuchshofer R. What increases outflow resistance in primary open-angle glaucoma? Surv Ophthalmol 52, Suppl 2: S101–S104, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taurin S, Sandbo N, Yau DM, Sethakorn N, Kach J, Dulin NO. Phosphorylation of myocardin by extracellular signal regulated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 284: 33789–33794, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian B, Gabelt BT, Geiger B, Kaufman PL. The role of the actomyosin system in regulating trabecular fluid outflow. Exp Eye Res 88: 713–717, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzima E. Role of small GTPases in endothelial cytoskeletal dynamics and the shear stress response. Circ Res 98: 176–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 265–275, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang DZ, Olson EN. Control of smooth muscle development by the myocardin family of transcriptional coactivators. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14: 558–566, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Zohar R, McCulloch CA. Multiple roles of α-smooth muscle actin in mechanotransduction. Exp Cell Res 312: 205–214, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet 363: 1711–1720, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiederholt M, Bielka S, Schweig F, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Lepple-Wienhues A. Regulation of outflow rate and resistance in the perfused anterior segment of the bovine eye. Exp Eye Res 61: 223–234, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiederholt M, Thieme H, Stumpff F. The regulation of trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle contractility. Prog Retin Eye Res 19: 271–295, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wisdom R, Huynh L, Hsia D, Kim S. RAS and TGF-β exert antagonistic effects on extracellular matrix gene expression and fibroblast transformation. Oncogene 24: 7043–7054, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.WuDunn D. Mechanobiology of trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res 88: 718–723, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao D, Zhang L. ERK MAP kinases regulate smooth muscle contraction in ovine uterine artery: effect of pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H292–H300, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yue BY. The extracellular matrix and its modulation in the trabecular meshwork. Surv Ophthalmol 40: 379–390, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang M, Maddala R, Rao PV. Novel molecular insights into RhoA GTPase-induced resistance to aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1057–C1070, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang M, Rao PV. Blebbistatin, a novel inhibitor of myosin II ATPase activity, increases aqueous humor outflow facility in perfused enucleated porcine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 4130–4138, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong C, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Brown J, Shaub A, Belkin AM, Burridge K. Rho-mediated contractility exposes a cryptic site in fibronectin and induces fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Biol 141: 539–551, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]