Abstract

Angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker (ARB) ameliorates progression of chronic kidney disease. Whether this protection is due solely to blockade of AT1, or whether diversion of angiotensin II from the AT1 to the available AT2 receptor, thus potentially enhancing AT2 receptor effects, is not known. We therefore investigated the role of AT2 receptor in ARB-induced treatment effects in chronic kidney disease. Adult rats underwent 5/6 nephrectomy. Glomerulosclerosis was assessed by renal biopsy 8 wk later, and rats were divided into four groups with equivalent glomerulosclerosis: no further treatment, ARB, AT2 receptor antagonist, or combination. By week 12 after nephrectomy, systolic blood pressure was decreased in all treatment groups, but proteinuria was decreased only with ARB. Glomerulosclerosis increased significantly in AT2 receptor antagonist vs. ARB. Kidney cortical collagen content was decreased in ARB, but increased in untreated 5/6 nephrectomy, AT2 receptor antagonist, and combined groups. Glomerular cell proliferation increased in both untreated 5/6 nephrectomy and AT2 receptor antagonist vs. ARB, and phospho-Erk2 was increased by AT2 receptor antagonist. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 mRNA and protein were increased at 12 wk by AT2 receptor antagonist in contrast to decrease with ARB. Podocyte injury is a key component of glomerulosclerosis. We therefore assessed effects of AT1 vs. AT2 blockade on podocytes and interaction with plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Cultured wild-type podocytes, but not plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 knockout, responded to angiotensin II with increased collagen, an effect that was completely blocked by ARB with lesser effect of AT2 receptor antagonist. We conclude that the benefical effects on glomerular injury achieved with ARB are contributed to not only by blockade of the AT1 receptor, but also by increasing angiotensin effects transduced through the AT2 receptor.

Keywords: podocyte, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

angiotensin ii (ANG II) acts at two major receptors, type 1 (AT1) and type 2 (AT2). Classic ANG II effects are mediated through AT1, including vasoconstriction, sodium reabsorption, sympathetic nerve stimulation, aldosterone secretion, and inhibition of renin synthesis (46). ANG II also induces cell growth, oxidative stress, inflammation, and matrix accumulation through upregulation of molecules such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (20). Human and experimental chronic kidney diseases (CKD) are characterized by progressive renal fibrosis. Inhibition of angiotensin actions, whether by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or AT1 receptor blocker (ARB), has been effective in ameliorating progression of CKD beyond effects on blood pressure (36). These beneficial effects have largely been linked to AT1 action blockade. However, beneficial effects of ARB could also be contributed to by increased levels of unbound ANG II after AT1 blockade being diverted to and activating the AT2 receptor. We sought to determine whether AT2 actions could play a role in these beneficial effects of ARB in a model of CKD widely studied and with relevance to human CKD, namely the renal ablation model (8). Pivotal studies from this model paved the way for understanding of the beneficial effects of ACEI in lowering glomerular hemodynamic stresses, and ameliorating or even reversing pathogenic events beyond hemodynamics, including direct effects to decrease matrix accumulation, and dampen mesangial, endothelial, and podocyte injuries (20, 21). Of note, these actions of the ARB and ACEI to ameliorate progressive kidney disease have been observed in human CKD even in patients classically regarded as having a low renin state, such as African-American patients with arterionephrosclerosis (51). These findings highlight the importance of local activation and interactions of components of the renin-angiotensin system, rather than systolic blood pressure (SBP) or peripheral renin levels, in mediating effects on sclerosis (51).

The role of the AT2 receptor in renal injury has been less defined than that of the AT1 receptor. The AT2 receptor counteracts the vasoconstrictor effect of the AT1 receptor (11, 26, 47), inhibits cellular proliferation, and promotes apoptosis (10, 14, 27, 35, 38). However, whether these actions are also active in vivo in CKD is controversial. AT2 receptor transgenic mice had less sclerosis than wild-type (WT) mice after 5/6 nephrectomy (Nx), a model of CKD. Furthermore, specific overexpression of a novel molecule that specifically mediates some AT2 receptor actions, namely the ANG II type 2 receptor-interacting protein 1(ATIP1), resulted in protection of mice against vascular injury (22). Correspondingly, sclerosis was worse in AT2−/− mice (5, 25), and interstitial fibrosis was also worsened with AT2 receptor antagonism (40). On the other hand, AT2 receptor blockade was renoprotective when given in the early phase of 5/6 Nx in rats (9). The balance of AT1 vs. AT2 activation also modulates NF-κβ and thus may modify net injury (17). In this study, we therefore investigated the role of the AT2 in the beneficial effects induced by ANG type 1 receptor blocker on remodeling of existing CKD in the widely studied renal ablation model, which importantly has relevance for progression of human CKD (3, 4, 7).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g; Charles River, Nashville, TN) were studied. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Rats were housed under normal conditions with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle at 21°C with 40% humidity and 12 air exchanges per hour, standard rat powdered diet (Purina Rodent meal 5001, 23.4% protein, 4.5% fat, 6% fiber, 0.4% sodium; Tusculum Feed Center, Nashville, TN), and water ad libitum. Rats underwent 5/6 Nx by right Nx and ligation of two or three branches of the left renal artery (36). This model is characterized by development of early sclerosis and proteinuria by week 4, which become established by week 8, with subsequent more rapid development of increasingly severe sclerosis, proteinuria, and hypertension (36). The removed right kidney was used as normal baseline tissue. Rats were allocated to treatment groups at 8 wk after 5/6 Nx to achieve equal average starting point of sclerosis assessed by open renal biopsy, and equal average levels of SBP and proteinuria before treatment were started. Rats were then treated as specified below for 4 more wk till death at week 12 after 5/6 Nx. The control 5/6 Nx group received no treatment (untreated control 5/6 Nx, n = 6). The ARB antagonist group (ARB, n = 6) received 80 mg/l drinking water losartan, a dose fourfold over minimum antihypertensive doses that we previously showed can induce regression of sclerosis from week 8 to week 12 in this model in some rats (36). The AT2R antagonist group (AT2RA, n = 6) received PD123319, 15 mg·kg−1·day−1 delivered sc by osmotic minipump (Alzet model 2ML4; Alza, Palo Alto, CA). PD123319 is a nonpeptide highly potent and selective AT2 receptor antagonist (gift of Pfizer) and is made in a trifluoroacetate salt formula (MW 776.4 vs. parent compound MW 508.6) which can be dissolved in normal saline. The dose chosen was based on previous studies in cardiovascular remodeling and kidney fibrosis, using 5–10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of parent compound, equivalent to 15 mg·kg−1·day−1 of the trifluoroacetate compound (9, 30). The combination group (combined, n = 6) received both losartan and PD123319 as above. Normal kidney tissue removed at time of 5/6 Nx was used as normal control for some tissue assessments.

SBP was measured using conscious tail-cuff plethysmography in prewarmed trained rats at ambient temperature of 29°C. Animals were placed in metabolic cages for collection of 24-h urine samples. Urine protein excretion was measured by Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Serum creatinine was measured at 12 wk by Vitros CREA slides (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY). Creatinine clearance was calculated from 24-h urine samples at 12 wk.

Glomerular injury.

The severity of sclerosis in each glomerulus was graded from 0 to 4+ as follows: 0 = no lesion, 1+ = sclerosis of <25%, 2+ = sclerosis of 25–50%, 3+ = sclerosis of 50–75%, 4+ = sclerosis of >75% of the glomerulus, respectively (36). A whole kidney average sclerosis index for each rat was obtained by averaging scores from all glomeruli on PAS-stained sections. All sections were examined without knowledge of the treatment protocol. Change of sclerosis from biopsy to autopsy was calculated for each animal as previously described (36).

Immunostaining and TUNEL.

Immunohistochemistry was performed with monoclonal mouse antibody to proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), followed by rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Dako), or rabbit anti-rat PAI-1 antibody (American Diagnostica, Greenwich, CT). Control slides treated with nonspecific antisera instead of primary antibody showed no staining. PCNA-positive nuclei per glomerulus were counted and averaged for all glomeruli. Apoptotic cells were detected by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL), which may also detect preapoptotic cells, following manufacturer's directions (ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Positive control slides were treated with DNase (1.0 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) before labeling reaction. Negative controls were incubated with TdT buffer without TdT.

TUNEL-positive nuclei per glomerulus were counted and averaged for all glomeruli on each section. Apoptosis in cortical tubules of kidney was semiquantitatively scored from 0 to 4: 0 = no positivity, 1+ = positivity of tubular nuclei <25%, 2+ = 25–50%, 3+ = 50–75%, 4+ = >75% in 10 nonoverlapping ×200 fields, and average score was calculated for each section. All sections were examined without knowledge of the treatment protocol.

In situ hybridization.

35S-labeled sense and antisense riboprobes for PAI-1 were prepared as previously described (41). Negative control in situ hybridization was done with sense probes and showed no signal. PAI-1 mRNA was assessed by image analysis using SCION Image Beta 4.03 (Scion, Frederick, MD). Briefly, at least eight nonoverlapping random ×200 dark fields in the cortex were assessed for positive signals calculated as percent area of field occupied by PAI-1 mRNA signal, and average was calculated for each section. All sections were examined without knowledge of the treatment protocol.

Gene expression studies.

Total RNA was isolated from kidney cortex using the RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed using the TaqMan reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR amplifications were performed on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Following inventoried TaqMan assays, IDs were used: Rn01435427_m1 for rat AT1a, Rn02132799_s1 for Rat AT1b, and Hs99999901_s1 for 18s ribosome. 18s rRNA was used as internal control. The relative levels of mRNA expression for these genes were obtained as previously described (32).

Western blot analysis.

Tissue protein extracts were analyzed with rabbit anti-rat PAI-1 antibody (American Diagnostica) and rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Erk1 and Erk2) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) as primary antibodies with appropriate secondary antibody and visualized using an ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham Biosciences). Membranes were reprobed with mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma) and mouse anti-MAP kinase 2 (Erk2; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) as loading controls and expression was semiquantitatively assessed by SCION Image Beta 4.03 (Scion) as a densitometric ratio relative to each loading control.

Collagen content.

Renal cortex was isolated and frozen, and collagen content was calculated from the concentration of hydroxyproline, measured as their phenylisothiocyanate derivatives by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (35). Briefly, tissue homogenates were hydrolyzed in vacuo in constant boiling HCl (110°C, 16 h) and were dried and taken up in 1 ml of redrying solution [ethanol/water/(C2H5)3N, 2:2:1], and 100 μl were redried under nitrogen. Twenty microliters of derivatization reagent [ethanol/water/(C2H5)3N/phenylisothio-cyanate, 7:1:1:1] were added, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 20 min. The sample was then lyophilized during centrifugation to remove the reagents. Samples were either frozen at this stage or diluted to 1 ml with buffer (5% acetonitrile in 5 mmol/l disodium phosphate, pH 7.4). A solution containing amino acid standards was dried and coupled in the same manner. The coupling efficiency was >99% under these conditions. Collagen content was expressed as percent of total protein.

Podocyte culture.

Podocyte injury is crucial for progression of glomerulosclerosis. We therefore studied the effects of AT1 vs. AT2 blockade on injury induced by ANG II in cultured podocytes. Our in vivo studies pointed to a key role of PAI-1 in glomerulosclerosis. We therefore also investigated the role of PAI-1 and interaction with AT1 vs. AT2 in podocyte injury. To achieve these goals, we cultured podocytes from WT and PAI-1−/− mouse kidneys as previously described (34). Podocyte identity was confirmed by WT-1 and synaptopodin staining (34). WT and PAI-1−/− podocytes were preincubated for 24 h with ARB (10−5 M) or AT2RA (10−5 M) or both or left untreated and then exposed to ANG II (10−7 M) for 48 h in the presence of ARB, AT2RA, or both, and compared with control cells without ANG II or additional treatment. Doses were based on a previous study in cultured cells (23, 31). Collagen α1/2(IV) accumulation in the supernatant was chosen as a marker of profibrotic injury to the podocyte and was assessed by ELISA. Activation of the Erk pathway was assessed in WT podocytes. WT podocytes were serum-starved (control) or serum-starved with additional treatment for 15 min with ANG II with added ARB, AT2RA, or combination in doses as above as indicated.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA or Mann-Whitney U-test. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

SBP and renal function.

Body weight was not different among the groups at any time (Table 1). SBP tail-cuff plethysmograph, 24-h proteinuria, and serum creatinine were by study design equivalent among groups before treatments began 8 wk after 5/6 Nx, a time point of established early sclerosis in this model. SBP at 12 wk was decreased only numerically in AT2RA alone and significantly in ARB and combined groups vs. the untreated 5/6 Nx group (untreated 5/6 Nx 206.6 ± 3.5, ARB 157.1 ± 12.8, AT2RA 180.3 ± 12.9 mmHg, combined 164.3 ± 4.8, untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB P < 0.05, untreated 5/6 Nx vs. combined P < 0.05; Table 1). Proteinuria at 12 wk was decreased vs. the untreated 5/6 Nx group in ARB and combined groups but not in AT2RA-treated rats. Proteinuria was decreased by ARB, and in contrast remained high in untreated 5/6 Nx rats and in AT2RA-treated rats (untreated 5/6 Nx 463.2 ± 39.1, ARB 199.3 ± 48.9, AT2RA 386.5 ± 34.8, combined 242.1 ± 79.5 mg/day, untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB P < 0.01, untreated 5/6 Nx vs. combined P < 0.05, ARB vs. AT2RA P < 0.05; Table 1). Serum creatinine and creatinine clearance after 4 wk of treatment were not significantly different between groups, mirroring our previous experience in this model and that of others (see Fig. 3; CCr untreated 5/6 Nx 0.8 ± 0.2, ARB 0.8 ± 0.3, AT2RA 0.6 ± 0.1, combined 0.6 ± 0.2 ml/min) (1). These relatively insensitive measures of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) did not reflect the improved proteinuria or the structural improvement with ARB, likely reflecting both the marked decrease in GFR resulting from the removal of a large portion of nephron mass before initiating treatment and the relatively short period of treatment.

Table 1.

Systemic and renal parameters

| Week | 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body wt, g | ||||

| CONT 5/6 Nx | 252.5 ± 6.2 | 312.8 ± 10.0 | 347.8 ± 19.0 | 385.0 ± 15.5 |

| ARB | 250.7 ± 10.7 | 301.5 ± 14.8 | 355.7 ± 20.1 | 353.8 ± 32.5 |

| AT2RA | 234.0 ± 13.9 | 278.7 ± 8.2 | 340.8 ± 8.4 | 364.7 ± 24.7 |

| Combined | 226.2 ± 13.5 | 283.2 ± 13.6 | 330.2 ± 3.7 | 368.3 ± 16.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | ||||

| CONT 5/6 Nx | 130.0 ± 6.4 | 186.6 ± 13.9 | 208.2 ± 8.8 | 206.6 ± 3.5 |

| ARB | 118.2 ± 4.6 | 186.5 ± 5.7 | 200.8 ± 6.7 | 157.1 ± 12.8* |

| AT2RA | 114.0 ± 3.5 | 183.6 ± 14.5 | 186.3 ± 11.5 | 176.4 ± 10.7 |

| Combined | 120.1 ± 5.6 | 181.5 ± 7.8 | 192.7 ± 10.0 | 163.5 ± 4.0* |

| Proteinuria, mg/day | ||||

| CONT 5/6 Nx | 8.7 ± 1.9 | 200.8 ± 37.4 | 280.3 ± 53.0 | 450.9 ± 26.8 |

| ARB | 7.0 ± 1.8 | 206.0 ± 27.1 | 293.3 ± 32.8 | 270.1 ± 55.6 |

| AT2RA | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 142.0 ± 29.1 | 283.0 ± 58.2 | 397.2 ± 30.4 |

| Combined | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 148.4 ± 27.1 | 256.8 ± 76.5 | 250.5 ± 65.5* |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | ||||

| CONT 5/6 Nx | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.13 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 1.43 ± 0.33 |

| ARB | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 2.28 ± 1.41 |

| AT2RA | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 1.14 ± 0.43 | 1.06 ± 0.07 | 1.82 ± 0.62 |

| Combined | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 2.00 ± 0.70 |

Values are means ± SE. ARB, angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker; CONT 5/6 Nx, control 5/6 nephrectomy.

P < 0.05 vs. CONT.

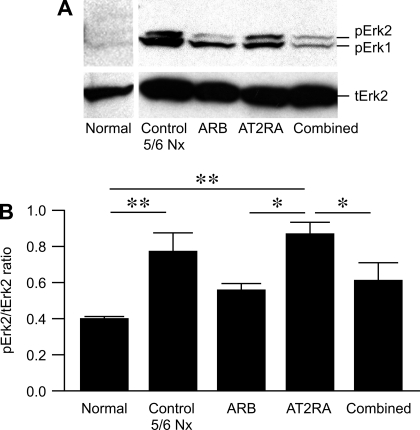

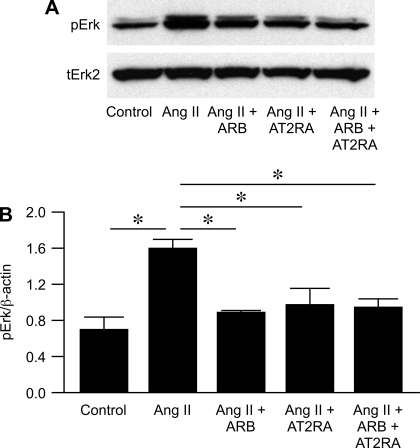

Fig. 3.

Representative Western blots of phospho-Erk 2 protein in the renal cortex of rats at 12 wk after 5/6 Nx (A). The expression of phospho-Erk 2 protein is presented as phospho-Erk 2/total Erk 2 ratio (B). **P < 0.01, normal vs. control untreated 5/6 Nx, normal vs. AT2RA. *P < 0.05, AT2RA vs. ARB, AT2RA vs. combined; n = 3 for normal; n = 5–6 for all other groups.

Kidney scarring.

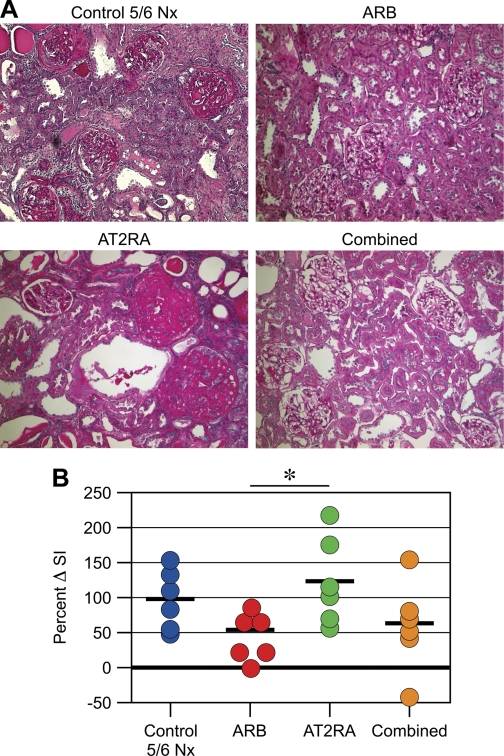

By study design, glomerulosclerosis was similar in 8-wk biopsies in all groups (sclerosis index at 8 wk untreated 5/6 Nx 0.92 ± 0.16, ARB 0.86 ± 0.17, AT2RA 0.79 ± 0.10, combined 0.78 ± 0.10). At 12 wk after 5/6 Nx, glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, dilatation, cast formation, and interstitial fibrosis were far more advanced compared with biopsy in untreated 5/6 Nx and also in rats treated only with AT2RA (Fig. 1A). Normal baseline kidneys removed at time of 5/6 Nx showed no glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, or tubular atrophy. Average sclerosis increase was significantly less in ARB-treated rats, with regression in some rats (percent change in sclerosis from biopsy to autopsy; untreated 5/6 Nx 93.4 ± 17.8, ARB 50.6 ± 18.3, AT2RA 121.8 ± 25.8, combined 57.3 ± 26.6%; ARB vs. AT2RA P < 0.05; Fig. 1B).

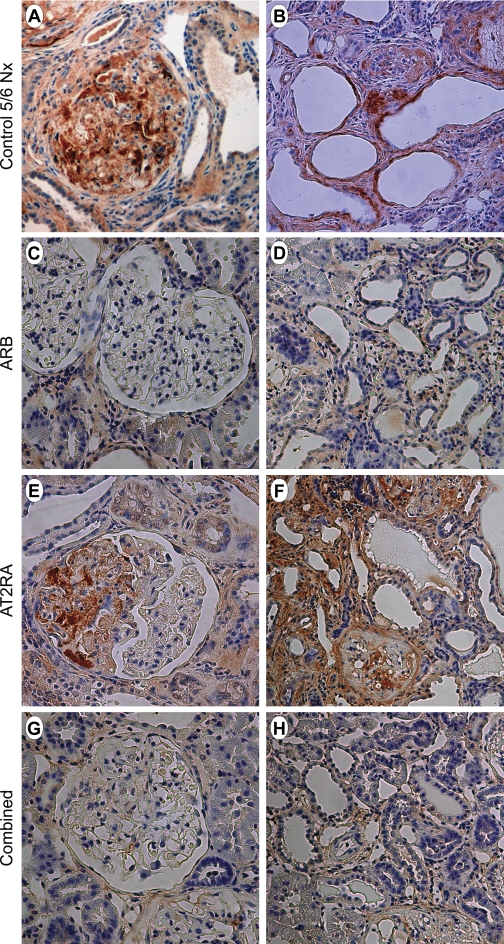

Fig. 1.

Effects of interventions on structural injury. Glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis were prominent in control untreated 5/6 nephrectomy (Nx) and AT2RA, and less in angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker (ARB) and combined at 12 wk after 5/6 Nx (A; ×100, periodic acid-Schiff). Sclerosis progressed in control untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA from biopsy to autopsy with on average doubling of severity (i.e., >100% increase). Average sclerosis increase was significantly decreased in ARB group, with regression in one rat, in contrast to no benefit of AT2RA alone (B). *P < 0.05, ARB vs. AT2RA.

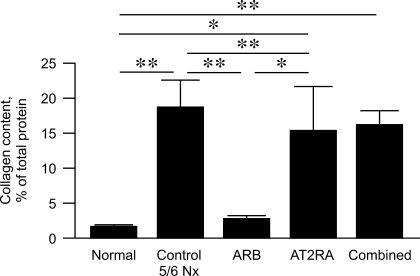

Kidney cortex collagen content, assessed by HPLC (37), was dramatically increased compared with normal kidney tissue removed at time of 5/6 Nx in untreated 5/6 Nx, AT2RA, and combined groups (Fig. 2), and nearly normalized in rats treated with ARB (normal kidney 1.7 ± 0.3, untreated 5/6 Nx 18.7 ± 3.8, ARB 2.5 ± 0.7, AT2RA 14.9 ± 6.6, combined 16.3 ± 2.0%, normal vs. untreated 5/6 Nx and combined P < 0.01, normal vs. AT2RA P < 0.05, ARB vs. AT2RA P < 0.05, ARB vs. combined and untreated 5/6 Nx P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Collagen content, assessed by HPLC of lysates from renal cortex. Compared with normal kidney, collagen content increased significantly in control untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA, with significant decrease in ARB but not combined group. **P < 0.01, normal vs. control untreated 5/6 Nx, normal vs. combined, control untreated 5/6 Nx vs. AT1RA, AT1RA vs. combined. *P < 0.05, normal vs. AT2RA, ARB vs. AT2RA; n = 4 for normal; n = 5–6 for all other groups.

We next studied whether AT1a vs. AT1b receptor expression shifted with interventions. Compared with untreated 5/6 Nx at 12 wk, expression of AT1a mRNA in kidney cortex increased 9.6 ± 5.1-fold in ARB-treated rats, 5.0 ± 2.7-fold in AT2RA-treated rats, and 6.8 ± 2.3-fold in combined group (P = 0.06 ARB vs. untreated 5/6 Nx). AT1b mRNA expression in kidney cortex also increased 3.7 ± 0.5-, 2.5 ± 0.4-, and 17.2 ± 11.0-fold, respectively, in ARB, AT2RA, and combined group, compared with untreated 5/6 Nx.

Cellular proliferation and apoptosis.

Immunostaining for PCNA was negative in the normal rat glomerulus in kidneys removed at time of 5/6 Nx (data not shown). Proliferation of glomerular cells was significantly increased in both untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA, and dampened in ARB and combined (untreated 5/6 Nx 3.5 ± 0.8, ARB 1.6 ± 0.1, AT2RA 3.8 ± 0.5, combined 2.1 ± 0.4/glomerulus; untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB P < 0.05, ARB or combined vs. AT2RA P < 0.01). Glomerular PCNA-positive cells included mesangial area and endothelial cells, and rare cells consistent with podocytes. Tubular cells were frequently positive for PCNA in untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA, with rare tubular positivity in ARB and combined groups. PCNA-positive interstitial cells were occasionally present in untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA groups, and were very rare in ARB and combined groups. Apoptosis as assessed by TUNEL-positive cells was present mostly in tubular epithelial cells, with few positive cells in glomeruli with no difference among groups (glomerulus: untreated 5/6 Nx 0.4 ± 0.2, ARB 0.3 ± 0.1, AT2RA 0.5 ± 0.1, combined 0.3 ± 0.2/glomerulus; cortex: untreated 5/6 Nx 2.1 ± 0.2, ARB 2.0 ± 0.1, AT2RA 2.2 ± 0.2, combined 2.2 ± 0.2). Thus, the balance of proliferation vs. apoptosis was shifted in untreated and AT2RA-treated glomeruli.

Erk 1/2 expression.

We next evaluated the activation of Erk1/2, a downstream signaling molecule for the angiotensin system. In normal kidney cortex, phosphorylated Erk was present at low levels. Phospho-Erk2 expression was upregulated by AT2RA vs. ARB or combined (normal kidney 0.39 ± 0.01, untreated 5/6 Nx 0.78 ± 0.10, ARB 0.56 ± 0.04, AT2RA 0.86 ± 0.07, combined 0.61 ± 0.10; normal vs. untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA P < 0.01, ARB vs. AT2RA P < 0.05, AT2RA vs. combined P < 0.05; Fig. 3).

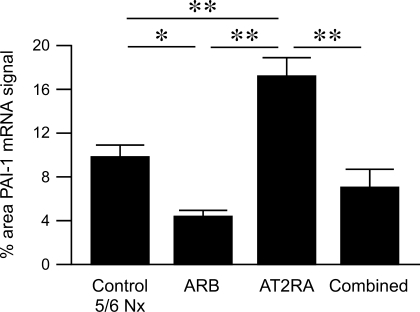

PAI-1 and plasmin expression.

In normal kidney, PAI-1 mRNA by in situ hybridization showed diffuse low-level tubular and no glomerular expression (data not shown). PAI-1 mRNA expression was augmented in untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA at 12 wk and was localized mainly in sclerotic glomeruli, mesangial areas, tubules, interstitial cells, and occasionally in glomerular endothelial cells, podocytes as identified by anatomical location, and small artery endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Image analysis showed that PAI-1 mRNA was significantly increased in untreated 5/6 Nx, and even further increased in AT2RA, compared with significant decrease in ARB and combined group (untreated 5/6 Nx 9.79 ± 1.00, ARB 4.36 ± 0.54, AT2RA 17.24 ± 1.62, combined 7.00 ± 1.69%; untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB P < 0.05, AT2RA vs. untreated 5/6 Nx, ARB or combined P < 0.01; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) mRNA in situ hybridization in kidney cortex was quantitatively analyzed by SCION Image Software and expressed as % area occupied by PAI-1 mRNA signal. PAI-1 mRNA expression was higher in control untreated 5/6 Nx, and further increased in AT2RA, compared with significant decrease in ARB and combined group. **P < 0.01, control untreated 5/6 Nx vs. AT2RA, ARB vs. AT2RA, AT2RA vs. combined. *P < 0.05, control untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB.

PAI-1 protein expression paralleled PAI-1 mRNA. PAI-1 immunostaining was mainly increased in areas of sclerosis and fibrosis with less staining in ARB and combined vs. untreated 5/6 Nx or AT2RA (Fig. 5). Western blotting verified that cortical PAI-1 protein expression was increased in untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA compared with ARB, with intermediate level in combined (untreated 5/6 Nx 0.70 ± 0.03, ARB 0.56 ± 0.04, AT2RA 0.73 ± 0.03, combined 0.64 ± 0.03; untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB P < 0.01, ARB vs. AT2RA P < 0.01; Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

PAI-1 immunostaining at 12 wk after 5/6 Nx (control 5/6 Nx: A, B; ARB: C, D; AT2RA: E, F; combined: G, H). PAI-1 protein paralleled that of PAI-1 mRNA in glomeruli and the tubulointerstitial area. PAI-1 immunostaining was especially increased in sclerotic glomeruli and was markedly increased in control untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA-treated rats (A, B, E, F), with less staining in ARB and combined rats (C, D, G, H). A, C, E, G: ×400. B, D, F, H: ×200, anti-PAI-1 staining.

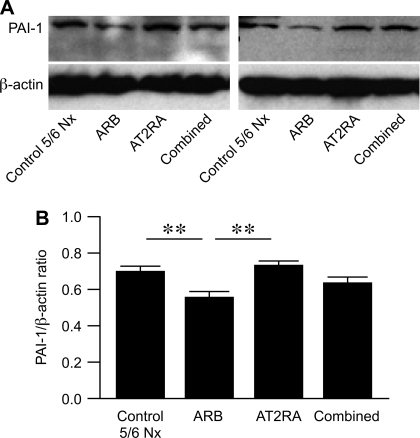

Fig. 6.

PAI-1 protein in kidney cortex was evaluated by Western blotting (representative blots), shown as PAI-1/β-actin ratio (B; mean for each group). PAI-1 protein was increased in control untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA compared with ARB group, with intermediate levels in combined. **P < 0.01, control untreated 5/6 Nx vs. ARB, ARB vs. AT2RA.

Plasmin activity of kidney cortex at 12 wk after 5/6 Nx showed a trend for decrease in AT2RA and combined groups even below the slightly decreased level seen in untreated 5/6 Nx, whereas ARB-treated rats had normalized plasmin levels (normal kidney 0.16 ± 0.05, untreated 5/6 Nx 0.12 ± 0.02, ARB 0.16 ± 0.08, AT2RA 0.08 ± 0.02, combined 0.06 ± 0.01) (28, 36).

Effects of AT1 vs. AT2 receptor blocker on podocytes.

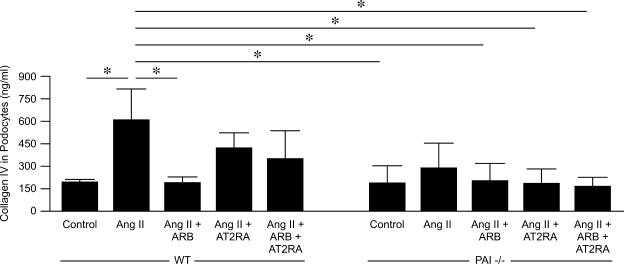

The podocyte is a key responder and modulator of development of glomerulosclerosis. We therefore examined podocyte-specific responses to ANG II, evaluating whether this response was influenced by AT1 or AT2 receptor blocker. We further assessed whether PAI-1 contributed to any differential response by studying WT and PAI-1−/− podocytes. We used mouse primary podocyte cultures as rat knockout for PAI-1 is not available. In WT, but not PAI-1−/− podocytes, ANG II significantly increased collagenα1/2(IV) in supernatant measured by ELISA compared with control (control 192.8 ± 19.1 vs. ANG II 557.3 ± 158.8 ng/ml, P < 0.05). ARB completely blocked this response in WT podocytes, with only numerical decrease with AT2RA or combination (ANG II + ARB 188.7 ± 36.7, ANG II + AT2RA 423.3 ± 98.5, ANG II + combination 346.7 ± 186.3 ng/ml, ANG II vs. ARB P < 0.05, ANG II vs. AT2RA or combination P = NS; Fig. 7). Although phosphorylation of Erk was increased by ANG II, ARB and AT2RA were equally effective in blunting this response in WT podocytes (p-Erk/β-actin ratio: control 0.70 ± 0.13, ANG II 1.60 ± 0.09, ANG II + ARB 0.89 ± 0.01, AT2RA 0.97 ± 0.18, combination 0.94 ± 0.09; Fig. 8). These studies support that the podocyte's profibrotic response to ANG II is largely AT1 mediated and is dependent on the presence of PAI-1.

Fig. 7.

Wild-type (WT) and PAI-1−/− podocytes collagen secretion in response to ANG II. ANG II induced collagen secretion, measured by ELISA, in WT but not in PAI-1−/− podocytes. This response to ANG II was completely prevented by ARB, with only numerical decrease by AT2RA and combined treatment. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 8.

Phosphorylation of Erk was increased by ANG II, with similar inhibition by either ARB or AT2RA or combination. Results are from 2 independent experiments, each in triplicate. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiological role of the AT2 receptor in CKD has not been defined. Renoprotection linked to the AT2 receptor has been variably reported even in the same model, 5/6 Nx (9, 25, 50). These results could, in part, reflect different time points of intervention and observation. Thus, the AT2 receptor was linked to injurious effects at 4 wk after 5/6 Nx (9). In contrast, later or earlier time points suggested beneficial effects of the AT2 receptor on sclerosis (19). Species differences in mice vs. rats could also underlie some of the conflicting reports. We chose to study the rat model of 5/6 Nx with ligation of renal artery branches, as results from this model previously showed relevance to insights and treatment of human CKD. Effects of AT2R may differ in other models with less hypertension and other pathogenic mechanisms. Next, we decided to study the role of the AT2 receptor in existing glomerulosclerosis, as this delayed timing of intervention is most relevant to human CKD where treatment is initiated after the disease is clinically evident. Our studies show that in the setting of such delayed intervention, not only is blockade of the AT2 receptor of no benefit, it prevents the beneficial effects of ARB on sclerosis and proteinuria when added to this treatment. Of note, these beneficial effects on renal damage are not paralleled by significant decrease in serum creatinine. We and others previously observed this apparent discordance in the 5/6 Nx model, which likely reflects the short duration of treatment, the relative insensitivity of serum creatinine as a measure of GFR in rodents and humans, and the loss of renal function following the initial surgical removal of 5/6 of renal mass that leaves fewer nephrons with the potential to measurably improve function even in the face of less sclerosis (1, 36, 42).

Next, we investigated the mechanisms whereby the AT2 receptor might modulate kidney fibrosis in this model. In vitro studies demonstrated that AT2 receptor-mediated signal induces not only downregulation of cellular proliferation but also upregulation of apoptosis by inhibition of cell signaling Erk1/2 and PI3K, and Akt activation through activation of tyrosine phosphatases (14, 27). However, whether the AT2 receptor has anti-proliferative effects in vivo is controversial (9, 10, 17). Glomerular PCNA positivity was reduced by AT2 receptor antagonism in a rat injury model of ANG II infusion (43). In contrast, our study showed that glomerular PCNA-positive cells remained remarkably high in AT2 receptor antagonism-treated rats, similar to untreated control remnant kidney rats. Moreover, phosphorylated Erk2 remained significantly upregulated in AT2 receptor antagonist-treated rats, similar to the 5/6 Nx-untreated rats. Our in vitro data show that podocytes injured by ANG II also have increased phosphorylated Erk2, but ARB and AT2RA and combination dampened this response. These data indicate that effects of AT2RA to decrease Erk2 activation in vivo are mediated by actions on cells other than podocytes. Erk-MAP kinase signaling induces cellular proliferation via transcriptional factors such as AP-1 (16), and inhibits apoptosis through Bcl-2 phosphorylation, and AT2 modifies these molecules in vitro (18, 27, 44). In vivo in the protein overload model of tubulointerstitial injury, increased apoptosis in proximal tubules was linked with upregulation of AT2 and altered Erk and Bcl-2 (49). In our model of glomerulosclerosis, we did not demonstrate changes in TUNEL staining with ARB or AT2RA; however, this assessment does not exclude possible effects on cell death. Our data indicate that the AT2 receptor might downregulate glomerular cellular proliferation in this setting by inactivation of Erk signaling.

ANG II is one key factor in the development of renal fibrosis (19, 20). Our data show that AT2 receptor antagonism only numerically decreased SBP, and thus we cannot rule out that blood pressure effects could contribute to our observations. However, in the combined group with ARB and AT2RA, blood pressure was even significantly decreased; yet, the added AT2R antagonism prevented the beneficial effects observed with ARB alone. Thus, these data point to additional effects of modulating the AT2 receptor beyond or in addition to any effect related to modest changes in blood pressure.

The rodent has two subtypes of the AT1 receptor, the major AT1A receptor, and the less abundant AT1B receptor. The latter has recently been suggested to contribute to increased inflammation and glomerular injury (13). ARB blocks both receptors. Our mRNA expression data suggest the possibility that AT2RA could not only block the potential beneficial effects of AT2 receptor, but also result in upregulated AT1B receptor, which might also contribute to worsened injury with AT2RA alone. Whether receptor protein and signal transduction of AT1B are affected by AT2 receptor modulation and possible interactions awaits further study.

ANG II has manifold profibrotic effects in addition to induction of hypertension: it induces extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation directly and indirectly by inducing TGF-β, and inhibitors of ECM turnover, such as PAI-1, induced by AT1 effects (15, 21, 41). Effects of AT2 on the ECM are less well-delineated. Our results show that PAI-1 mRNA expression was increased by AT2 receptor antagonism even beyond untreated 5/6 Nx levels, in contrast to the marked decrease in PAI-1 affected by ARB. Furthermore, addition of AT2RA to ARB resulted in higher PAI-l expression by in situ hybridization compared with ARB alone. Western blots confirmed high levels of PAI-1 in untreated 5/6 Nx and AT2RA-treated rats, and decreased PAI-1 with ARB, with numerically intermediate level with combined therapy. These results support that the AT2 receptor might suppress progression of glomerulosclerosis and renal scarring through downregulation of PAI-1 in the remnant kidney model, and conversely, that inhibition of AT2 action increases PAI-1, thus promoting fibrosis.

The Erk pathway could induce PAI-1 through transactivation of downstream transcriptional factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1, Elk-1, and AP-1 (12, 24, 48). We speculate that AT2 receptor antagonism augments PAI-1 expression through upregulation of Erk phosphorylation in the 5/6 Nx kidney. Our in vitro studies of podocytes showed that AT1 vs. AT2 effects on ANG II-induced collagen were not linked to altered Erk activation. Possible newly identified mediators of AT2 signaling, such as ATIP1, might be involved in fibrosis responses (22). However, PAI-1 expression might also be modulated by AT2-dependent mechanisms through, e.g., inhibition of bradykinin/NO/cGMP pathway (6). Future in vitro studies may elucidate in greater detail the relationship between the AT2 receptor and PAI-1.

We also showed that renal collagen was significantly decreased by ARB, with even greater benefit of ARB on cortical collagen content, a measure largely reflecting tubulointerstitial fibrosis, than on glomerulosclerosis. Furthermore, added AT2 receptor antagonism in particular dampened ARB benefits on collagen content, supporting key effects of AT1/AT2 balance on the tubulointerstitium in fibrotic states. Effects of the AT2 receptor on fibrosis have been controversial both in vitro and in vivo (2, 9, 29, 30, 33, 35, 39, 40, 45). AT2 receptor stimulation in vitro increased collagen synthesis in vascular smooth muscle and mesangial cells via a Gα1-mediated mechanism, while essentially opposite effects were observed in fibroblasts (39). In vivo studies of transgenic mice with upregulation of ATIP1 showed protection against neointimal response in the injured femoral artery (22). These results suggest that AT2 receptor-mediated signals might have heterogeneous effects on different cell types.

In summary, our results indicate that the beneficial effects of ARB on renal injury are complex and involve both blockade of deleterious AT1 actions and actions of the AT2 receptor.

GRANTS

These studies were supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-58942 and DK-44757 (to A. B. Fogo).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The AT2 receptor antagonist was a generous gift from Pfizer. This work has been presented in part in abstract form at the American Society of Nephrology Meeting (J Am Soc Nephrol 16:654A, 2005).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamczak M, Gross ML, Krtil J, Koch A, Tyralla K, Amann K, Ritz E. Reversal of glomerulosclerosis after high-dose enalapril treatment in subtotally nephrectomized rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2833–2842, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akishita M, Iwai M, Wu L, Zhang L, Ouchi Y, Dzau VJ, Horiuchi M. Inhibitory effect of angiotensin II type 2 receptor on coronary arterial remodeling after aortic banding in mice. Circulation 102: 1684–1689, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson S, Meyer TW, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Control of glomerular hypertension limits glomerular injury in rats with reduced renal mass. J Clin Invest 76: 612–619, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson S, Rennke H, Brenner BM. Therapeutic advantage of converting enzyme inhibitors in arresting progressive renal disease associated with systemic hypertension in the rat. J Clin Invest 77: 1993–2000, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benndorf RA, Krebs C, Hirsch-Hoffmann B, Schwedhelm E, Cieslar G, Schmidt-Haupt R, Steinmetz OM, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Thaiss F, Haddad M, Fehr S, Heilmann A, Helmchen U, Hein L, Ehmke H, Stahl RA, Boger RH, Wenzel UO. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor deficiency aggravates renal injury and reduces survival in chronic kidney disease in mice. Kidney Int 75: 1039–1049, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouchie JL, Hansen H, Feener EP. Natriuretic factors and nitric oxide suppress plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Role of cGMP in the regulation of the plasminogen system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 1771–1779, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens 1: 335–347, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Z, Bonnet F, Candido R, Nesteroff SP, Burns WC, Kawachi H, Shimizu F, Carey RM, De Gasparo M, Cooper ME. Angiotensin type 2 receptor antagonism confers renal protection in a rat model of progressive renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1773–1787, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Z, Kelly DJ, Cox A, Casley D, Forbes JM, Martinello P, Dean R, Gilbert RE, Cooper ME. Angiotensin type 2 receptor is expressed in the adult rat kidney and promotes cellular proliferation and apoptosis. Kidney Int 58: 2437–2451, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey RM. Update on the role of the AT2 receptor. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 67–71, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang H, Shyu KG, Lin S, Tsai SC, Wang BW, Liu YC, Sung YL, Lee CC. The plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene is induced by cell adhesion through the MEK/ERK pathway. J Biomed Sci 10: 738–745, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowley SD, Vasievich MP, Ruiz P, Gould SK, Parsons KK, Pazmino AK, Facemire C, Chen BJ, Kim HS, Tran TT, Pisetsky DS, Barisoni L, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Jeansson M, Foster MH, Coffman TM. Glomerular type 1 angiotensin receptors augment kidney injury and inflammation in murine autoimmune nephritis. J Clin Invest 119: 943–953, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui TX, Nakagami H, Nahmias C, Shiuchi T, Takeda-Matsubara Y, Li JM, Wu L, Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Angiotensin II subtype 2 receptor activation inhibits insulin-induced phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt and induces apoptosis in PC12W cells. Mol Endocrinol 16: 2113–2123, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eddy AA, Fogo AB. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in chronic kidney disease: evidence and mechanisms of action. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2999–3012, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson M, Leppa S. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and activator protein 1 are required for proliferation and cardiomyocyte differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 277: 15992–16001, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esteban V, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Suzuki Y, Mezzano S, Blanco J, Kretzler M, Sugaya T, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M. Angiotensin II, via AT1 and AT2 receptors and NF-κB pathway, regulates the inflammatory response in unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1514–1529, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer TA, Singh K, O'Hara DS, Kaye DM, Kelly RA. Role of AT1 and AT2 receptors in regulation of MAPKs and MKP-1 by ANG II in adult cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H906–H916, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogo AB. Progression and potential regression of glomerulosclerosis (Nephrology Forum). Kidney Int 59: 804–819, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fogo AB. Renal fibrosis and the renin-angiotensin system. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 31: 69–87, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogo AB. The role of angiotensin II and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in progressive glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 179–188, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita T, Mogi M, Min LJ, Iwanami J, Tsukuda K, Sakata A, Okayama H, Iwai M, Nahmias C, Higaki J, Horiuchi M. Attenuation of cuff-induced neointimal formation by overexpression of angiotensin II type 2 receptor-interacting protein 1. Hypertension 53: 688–693, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gloy J, Henger A, Fischer KG, Nitschke R, Bleich M, Mundel P, Schollmeyer P, Greger R, Pavenstadt H. Angiotensin II modulates cellular functions of podocytes. Kidney Int Suppl 67: S168–S170, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo B, Inoki K, Isono M, Mori H, Kanasaki K, Sugimoto T, Akiba S, Sato T, Yang B, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A, Haneda M, Koya D. MAPK/AP-1-dependent regulation of PAI-1 gene expression by TGF-β in rat mesangial cells. Kidney Int 68: 972–984, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto N, Maeshima Y, Satoh M, Odawara M, Sugiyama H, Kashihara N, Matsubara H, Yamasaki Y, Makino H. Overexpression of angiotensin type 2 receptor ameliorates glomerular injury in a mouse remnant kidney model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F516–F525, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiyoshi H, Yayama K, Takano M, Okamoto H. Stimulation of cyclic GMP production via AT2 and B2 receptors in the pressure-overloaded aorta after banding. Hypertension 43: 1258–1263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horiuchi M, Hayashida W, Kambe T, Yamada T, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin type 2 receptor dephosphorylates Bcl-2 by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem 272: 19022–19026, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Y, Haraguchi M, Lawrence DA, Border WA, Yu L, Noble NA. A mutant, noninhibitory plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 decreases matrix accumulation in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest 112: 379–388, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ichihara S, Senbonmatsu T, Price E, Jr, Ichiki T, Gaffney FA, Inagami T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor is essential for left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in chronic angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circulation 104: 346–351, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones ES, Black MJ, Widdop RE. Angiotensin AT2 receptor contributes to cardiovascular remodelling of aged rats during chronic AT1 receptor blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 1023–1030, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang YS, Park YG, Kim BK, Han SY, Jee YH, Han KH, Lee MH, Song HK, Cha DR, Kang SW, Han DS. Angiotensin II stimulates the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor through the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in cultured mouse podocytes. J Mol Endocrinol 36: 377–388, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanjanabuch T, Ma LJ, Chen J, Pozzi A, Guan Y, Mundel P, Fogo AB. PPAR-γ agonist protects podocytes from injury. Kidney Int 71: 1232–1239, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurisu S, Ozono R, Oshima T, Kambe M, Ishida T, Sugino H, Matsuura H, Chayama K, Teranishi Y, Iba O, Amano K, Matsubara H. Cardiac angiotensin II type 2 receptor activates the kinin/NO system and inhibits fibrosis. Hypertension 41: 99–107, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang XB, Ma LJ, Naito T, Wang Y, Madaio M, Zent R, Pozzi A, Fogo AB. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker restores podocyte potential to promote glomerular endothelial cell growth. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1886–1895, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, Nishimura H, Fogo AB, Kon V, Inagami T, Ichikawa I. Accelerated fibrosis and collagen deposition develop in the renal interstitium of angiotensin type 2 receptor null mutant mice during ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 53: 937–944, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma LJ, Nakamura S, Aldigier JC, Rossini M, Yang H, Liang X, Nakamura I, Marcantoni C, Fogo AB. Regression of glomerulosclerosis with high-dose angiotensin inhibition is linked to decreased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 966–976, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma LJ, Nakamura S, Whitsitt JS, Marcantoni C, Davidson JM, Fogo AB. Regression of sclerosis in aging by an angiotensin inhibition-induced decrease in PAI-1. Kidney Int 58: 2425–2436, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsubara H, Shibasaki Y, Okigaki M, Mori Y, Masaki H, Kosaki A, Tsutsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Fujiyama S, Nose A, Iba O, Tateishi E, Hasegawa T, Horiuchi M, Nahmias C, Iwasaka T. Effect of angiotensin II type 2 receptor on tyrosine kinase Pyk2 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase via SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase activity: evidence from vascular-targeted transgenic mice of AT2 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 282: 1085–1091, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mifune M, Sasamura H, Shimizu-Hirota R, Miyazaki H, Saruta T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors stimulate collagen synthesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 36: 845–850, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrissey JJ, Klahr S. Effect of AT2 receptor blockade on the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F39–F45, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura S, Nakamura I, Ma LJ, Vaughan DE, Fogo AB. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression is regulated by the angiotensin type 1 receptor in vivo. Kidney Int 58: 251–259, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piecha G, Koleganova N, Gross ML, Geldyyev A, Adamczak M, Ritz E. Regression of glomerulosclerosis in subtotally nephrectomized rats: effects of monotherapy with losartan, spironolactone, and their combination. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F137–F144, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizkalla B, Forbes JM, Cooper ME, Cao Z. Increased renal vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins by angiotensin II infusion is mediated by both AT1 and AT2 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3061–3071, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibasaki Y, Matsubara H, Nozawa Y, Mori Y, Masaki H, Kosaki A, Tsutsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Fujiyama S, Nose A, Iba O, Tateishi E, Hasegawa T, Horiuchi M, Nahmias C, Iwasaka T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation by increasing association of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase. Hypertension 38: 367–372, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu-Hirota R, Sasamura H, Mifune M, Nakaya H, Kuroda M, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Regulation of vascular proteoglycan synthesis by angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2609–2615, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siragy HM. AT1 and AT2 receptors in the kidney: role in disease and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 36: S4–S9, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siragy HM, Carey RM. The subtype 2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor mediates renal production of nitric oxide in conscious rats. J Clin Invest 100: 264–269, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda K, Ichiki T, Tokunou T, Iino N, Fujii S, Kitabatake A, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Critical role of Rho-kinase and MEK/ERK pathways for angiotensin II-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 gene expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 868–873, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tejera N, Gomez-Garre D, Lazaro A, Gallego-Delgado J, Alonso C, Blanco J, Ortiz A, Egido J. Persistent proteinuria upregulates angiotensin II type 2 receptor and induces apoptosis in proximal tubular cells. Am J Pathol 164: 1817–1826, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vazquez E, Coronel I, Bautista R, Romo E, Villalon CM, Avila-Casado MC, Soto V, Escalante B. Angiotensin II-dependent induction of AT2 receptor expression after renal ablation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F207–F213, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wright JT, Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA 288: 2421–2431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]